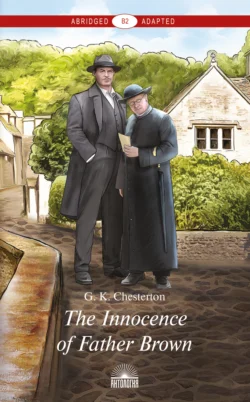

The Innocence of Father Brown / Неведение отца Брауна

Гилберт Кит Честертон

Тип: бесплатная электронная книга

Жанр: Литература 20 века

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 0.90 ₽

Статус: Нет в наличии

Издательство: Антология

Дата публикации: 12.03.2025

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Внешне неказистый и рассеянный, отец Браун ведёт привычную жизнь, пока не случается что-нибудь страшное. За его неприметной внешностью скрывается пытливый ум сыщика, способного разгадать непостижимые тайны. Откуда взялся труп незнакомца в саду знаменитого детектива? Кто мог убить известного поэта в запертой комнате? Кому удалось украсть сереебряные приборы на глазах у двенадцати свидетелей? На все вопросы отец Браун найдёт ответ. И ещё: он заботится не только о раскрытии дела, но и о спасении заблудших душ преступников. Даже к самым отпетым негодяям он пытается найти подход, стараясь смягчить их сердца и вызвать раскаяние.