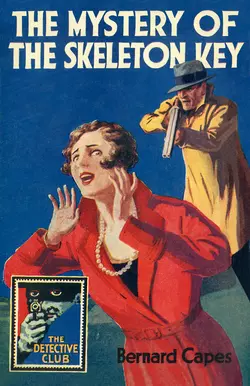

The Mystery of the Skeleton Key

Bernard Capes

Hugh Lamb

G. Chesterton K.

The fourth in a new series of classic detective stories from the vaults of HarperCollins involves a tragic accident during a shooting party. As the story switches between Paris and Hampshire, the possibility of it not being an accident seems to grow more likely.“The Detective Story Club”, launched by Collins in 1929, was a clearing house for the best and most ingenious crime stories of the age, chosen by a select committee of experts. Now, almost 90 years later, these books are the classics of the Golden Age, republished at last with the same popular cover designs that appealed to their original readers.The Mystery of the Skeleton Key, first published in 1919, has the distinction of being the first detective novel commissioned and published by Collins, though it was Bernard Capes’ only book in the genre, as he died shortly before it was published. This is how the Detective Club announced their edition ten years later:“Mr Arnold Bennett, in a recent article, criticised the ad hoc characterisation and human interest in the detective novels of to-day. “The Mystery of the Skeleton Key” contains, in addition to a clever crime problem and plenty of thrills, a sensible love story, humour, excellent characterisation and strong human interest. The scenes are laid in Paris and Hampshire. The story deals with a crime committed in the grounds of a country house and the subsequent efforts of a clever young detective the track down the perpetrator. The Selection Committee of “The Detective Story Club” have no hesitation in recommending this splendid thriller as one which will satisfy the most exacting reader of detective fiction.”This new edition comes with a brand new introduction by Capes expert and anthologist, Hugh Lamb.

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain as The Skeleton Key

by Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1919

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd 1929

Introduction © Hugh Lamb 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2015

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137144

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780008137151

Version: 2015-08-14

Contents

Cover (#u6e509ba1-663e-50d5-9dda-06772c3954ca)

Title Page (#u4a1641d9-cdb6-56dd-9cd7-d5592af9b9c6)

Copyright (#uc47cabe9-0d05-5f03-be8d-26efa0d29fde)

Introduction (#ue8006487-6c9d-59d0-89fc-f4d46d9284b1)

Epigraph (#ufecaa107-f77b-5dcb-8bb0-52899c72eaaf)

Introduction (#ud69afc31-47d1-5867-9ed2-3270d922ea52)

Chapter I: MY FIRST MEETING WITH THE BARON (#udbbe764b-6399-5d79-971d-0f804c7c09ca)

Chapter II: MY SECOND MEETING WITH THE BARON (#u2cb4432c-600a-5351-bbe0-97dee9711341)

Chapter III: WILDSHOTT (#u355527c9-7b8f-588e-b313-656b74136358)

Chapter IV: I AM INTERESTED IN THE BARON (#ub4b3f744-7e8a-5af9-ad8e-8510e86ddd6d)

Chapter V: THE BARON CONTINUES TO INTEREST ME (#uc6375e25-8ad6-5551-981b-889c41c2b5a7)

Chapter VI: ‘THAT THUNDERS IN THE INDEX’ (#u17fd39e2-3216-5a90-9809-0cf9ae267f72)

Chapter VII: THE BARON VISITS THE SCENE OF THE CRIME (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII: AN ENTR’ACTE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX: THE INQUEST (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X: AFTERWARDS (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI: THE BARON DRIVES (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII: THE BARON WALKS (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII: ACCUMULATING EVIDENCE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV: THE EXPLOSION (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV: THE FACE ON THE WALL (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI: THE BARON FINDS A CHAMPION (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII: AND AUDREY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII: THE BARON RETURNS (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX: THE DARK HORSE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XX: THE BARON LAYS HIS CARDS ON THE TABLE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI: A LAST WORD (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#uffe436dc-5e8c-516f-8652-b9be5e243ac8)

All authors, especially fiction writers, have to tread at some time on the edge of the dark slope that leads to obscurity. Some are unlucky enough to miss their step while still alive; many more slide down after their death. Such an unfortunate was Bernard Capes, who published 40 books (in 20 years) but passed into the shadows within three years of dying. He deserved better.

Bernard Edward Joseph Capes was born in London on 30 August 1854, a nephew of John Moore Capes, a prominent figure in the Oxford Movement. He was educated at Beaumont College and raised as a Catholic, though he later gave that up and followed no religion. His elder sister, Harriet Capes (1849–1936) was to become a noted translator and writer of children’s books.

Capes had a string of unsuccessful jobs. A promised Army commission failed to materialise; he spent an unhappy time in a tea-broker’s office; he studied art at the Slade School but, despite a lifelong enjoyment of painting and illustrating, it did not result in a career.

Things picked up for him in 1888 when he went to work for the publishers Eglington and Co., where he succeeded Clement Scott as editor of the magazine The Theatre.

At this point in his career, he made his first attempts at novel writing, publishing two under the pseudonym ‘Bevis Cane’: The Haunted Tower (1888) and The Missing Man (1889), the latter published by Eglington. They did not do well enough for him to use the ‘Bevis Cane’ name again.

Eglington and Co. went out of business in 1892 and Capes was up against it. Among his various ventures was a failed attempt at, of all things, breeding rabbits.

At last, aged 43, Capes found his true vocation. In 1897 he entered a competition for new authors organised by the Chicago Record. Capes came second with his novel The Mill of Silence, published in Chicago the same year.

He entered the competition again in 1898 when the Chicago Record repeated it. Capes hit the jackpot. His entry, The Lake of Wine—a long, macabre historical thriller about a fabulous ruby bearing the name of the book’s title—won the competition. It was published that year and Capes was a full-time writer from then on.

And write he did. Out flooded short stories, articles, newspaper editorials, reviews and novels, including two more in 1898.

Bernard Capes married Rosalie Amos and they moved to Winchester, where he spent the rest of his life. They had three children. His son Renalt became a writer late in life, and his grandson Ian Burns carries on the Capes writing tradition as the author of the children’s book Scratcher.

With nearly 40 books already to his name from a variety publishers, Capes’ historical adventure, Where England Sets Her Feet, was published by William Collins Sons & Co. in April 1918, with a second book, The Skeleton Key, already under contract. The significance of this new ‘criminal romance’ to the 100-year-old publishing house was yet to be realised. Modestly publicised as ‘a story dealing with crime committed in the grounds of a country house, and the subsequent efforts of a clever young detective to discover its perpetrator’, it coincided with a burgeoning post-war fashion for detective fiction. Within a few months of its publication in the spring of 1919, a flood of unsolicited crime-story manuscripts poured into the Scottish publishers’ Pall Mall office, and Collins acted quickly to capitalise on this new-found demand for detective stories.

Sadly, Capes himself never knew of The Skeleton Key’s success, for he was struck down by the influenza epidemic that swept Europe at the end of World War I. A short illness was followed by heart failure and he died in Winchester on 1 November 1918. He was 64 and had enjoyed only 20 years of writing.

His widow organised a plaque for him in Winchester Cathedral, among the likes of Izaak Walton and Jane Austen. It can still be seen, next to the entrance to the crypt.

Capes wrote historical adventures and romances, mystery novels, crime stories and many fine short stories, a lot of them dark and sinister tales (he was quite fond of werewolves). As a great fan of Wagner, he wrote a novel, The Romance of Lohengrin, published in 1905. At his memorial service in the cathedral in 1919, the organist played Wagner in his honour.

Published shortly after Capes’ death, complete with a hastily commissioned introduction by G. K. Chesterton that added to its notoriety, The Skeleton Key had already been reissued six times when, ten years later, Sir Godfrey Collins launched the company’s first dedicated crime imprint, The Detective Story Club—‘for detective connoisseurs’—a mixture of genre classics and cheap reprints. It was only natural that Capes’ book should be one of the launch titles for the new list, and so in July 1929 it appeared in its eighth edition alongside five other titles, priced only sixpence, with a dramatic jacket painting and an extended title intended to increase further the book’s popularity: The Mystery of the Skeleton Key.

By 1930, the ‘Golden Age’ of crime fiction was well underway, and Bernard Capes’ novel began to disappear as more and more inventive detective stories appeared on the market. In his 1972 book, Bloody Murder, Julian Symons called The Skeleton Key ‘a neglected tour de force’, but it’s only now, more than 40 years later, that Capes’ landmark novel has found its way back into print.

The story introduces the detective Baron Le Sage, who unravels a rather complicated murder. Le Sage is in the line of Robert Barr’s detective Eugene Valmont (who had appeared in 1906), and Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (who was yet to be created), with a touch of Dr Fell, and is one of Capes’ most interesting creations. As one character remarks, ‘Chess is the Baron’s business.’ He might have appeared again if Capes had survived longer. It’s good to see him, and Bernard Capes, back at work again.

HUGH LAMB

February 2015

EPIGRAPH (#uffe436dc-5e8c-516f-8652-b9be5e243ac8)

MRS BERNARD CAPES wishes to express her gratitude to Mr Chesterton for his appreciative introduction to her husband’s last work, and to Mr A. K. Cook for his invaluable assistance in preparing it for the press.

Winchester

INTRODUCTION (#uffe436dc-5e8c-516f-8652-b9be5e243ac8)

To introduce the last book by the late Bernard Capes is a sad sort of honour in more ways than one; for not only was his death untimely and unexpected, but he had a mind of that fertile type which must always leave behind it, with the finished life, a sense of unfinished labour. From the first his prose had a strong element of poetry, which an appreciative reader could feel even more, perhaps, when it refined a frankly modern and even melodramatic theme, like that of this mystery story, than when it gave dignity, as in Our Lady of Darkness, to more tragic or more historic things. It may seem a paradox to say that he was insufficiently appreciated because he did popular things well. But it is true to say that he always gave a touch of distinction to a detective story or a tale of adventure; and so gave it where it was not valued, because it was not expected. In a sense, in this department of his work at least, he carried on the tradition of the artistic conscience of Stevenson; the technical liberality of writing a penny-dreadful so as to make it worth a pound. In his short stories, as in his historical studies, he did indeed permit himself to be poetic in a more direct and serious fashion; but in his touch upon such tales as this the same truth may be traced. It is a good general rule that a poet can be known not only in his poems, but in the very titles of his poems. In the case of many works of Bernard Capes, The Lake of Wine, for instance, the title is itself a poem. And that case would alone illustrate what I mean about a certain transforming individual magic, with which he touched the mere melodrama of mere modernity. Numberless novels of crime have been concerned with a lost or stolen jewel; and The Lake of Wine was merely the name of a ruby. Yet even the name is original, exactly in the detail that is hardly ever original. Hundreds of such precious stones have been scattered through sensational fiction; and hundreds of them have been called ‘The Sun of the Sultan’ or ‘The Eye of Vishnu’ or ‘The Star of Bengal’. But even in such a trifle as the choice of the title, an indescribable and individual fancy is felt; a sub-conscious dream of some sea like a sunset, red as blood and intoxicant as wine. This is but a small example; but the same element clings, as if unconsciously, to the course of the same story. Many another eighteenth century hero has ridden on a long road to a lonely house; but Bernard Capes, by something fine and personal in the treatment, does succeed in suggesting that at least along that particular road, to that particular house, no man had ever ridden before. We might put this truth flippantly, and therefore falsely, by saying he put superior work into inferior works. I should not admit the distinction; for I deny that there is necessarily anything inferior in sensationalism, when it can really awaken sensations. But the truer way of stating it would perhaps be this; that to a type of work which generally is, for him or anybody else, a work of invention, he always added at least one touch of imagination

The detective or mystery tale, in which this last book is an experiment, involves in itself a problem for the artist, as odd as any of the problems which it puts to the policeman. A detective story might well be in a special sense a spiritual tragedy; since it is a story in which even the moral sympathies may be in doubt. A police romance is almost the only romance in which the hero may turn out to be the villain, or the villain to be the hero. We know that Mr Osbaldistone’s business has not been betrayed by his son Frank, though possibly by his nephew Rashleigh. We are quite sure that Colonel Newcome’s company has not been conspired against by his son Clive, though possibly by his nephew Barnes. But there is a stage in a story like The Moonstone, when we are meant to suspect Franklin Blake the hero, as he is suspected by Rachel Verinder the heroine; there is a stage in Mr Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case when the figure of Mr Marlowe is as sinister as the figure of Mr Manderson. The obvious result of this technical trick is to make it impossible, or at least unfair, to comment, not only on the plot, but even on the characters; since each of the characters should be an unknown quantity. The Italians say that translation is treason; and here at least is a case where criticism is treason. I have too great a love or lust for the roman policier to spoil sport in so unsportsmanlike a fashion; but I cannot forbear to comment on the ingenious inspiration by which in this story, one of the characters contrives to remain really an unknown quantity, by a trick of verbal evasion, which he himself defends, half convincingly, as a scruple of verbal veracity. That is the quality of Bernard Capes’ romances that remains in my own memory; a quality, as it were, too subtle for its own subject. Men may well go back to find the poems thus embedded in his prose.

G. K. CHESTERTON

CHAPTER I (#uffe436dc-5e8c-516f-8652-b9be5e243ac8)

MY FIRST MEETING WITH THE BARON (#uffe436dc-5e8c-516f-8652-b9be5e243ac8)

(From the late Mr Bickerdike’s ‘Apologia’, found in manuscript)

SOME few years ago, in the month of September, I happened to be kicking my heels in Paris, awaiting the arrival there of my friend Hugo Kennett. We had both been due from the south, I from Vaucluse and Kennett from the Riviera, and the arrangement had been that we should meet together for a week in the capital before returning home. Enfants perdus! Kennett was never anything but unpunctual, and he failed to turn up to time, or anywhere near it, at the rendezvous. I was a trifle hipped, as I had come to the end of my circular notes, and had rather looked to him to help me through with a passing difficulty; but there was nothing for it but to wait philosophically on, and to get, pending his appearance, what enjoyment I could out of life. It was not very much. The Parisian may be a saving man, but Paris is no city to save in. It is surprising how dull an empty purse can make it. It had come to this after two days, either that I must shift my quarters from the Ritz into cheaper lodgings, or abandon my engagement altogether and go back alone.

One afternoon, aimless and thirsty, I turned into the Café l’Univers in the Place du Palais Royal, and sat down at one of the little tables under the awning where was a vacant chair. This is a busy spot, upon which many streets converge, and one may rest there idly and study an infinite variety of human types. There was a man seated not far from me, against the glass side of the verandah whose occupation caught my attention. He was making very rapidly in a minute-book pencil notes of all the conspicuous ladies’ hats that passed him. It was extraordinary to observe the speed and fidelity with which he secured his transcripts. A few, apparently random, sweeps of the pencil in his thin nervous fingers, and there, in the flitting of a figure, was some unconscious head ravished of its most individual idea. It reminded me of the ‘wig-snatching’ of the eighteenth century; yet I could not but admire the dexterity of the thief, as, sitting behind him, I followed his skilful movements.

‘A clever dog that, sir,’ said a throaty voice beside me.

It came from a near neighbour, whom I had not much observed until now—a large-faced, clean-shaved gentleman of a very full body and a comfortable complacent expression. He was dressed in a baggy light-grey suit, wore a loose Panama hat on his head, and smelt, pleasantly and cleanly, of snuff. On the table before him stood a tumbler of grenadine and soda stuffed with lumps of ice, and with a couple of straws sticking from it.

‘Most,’ I answered. ‘What would you take him to be?’

‘Eh?’ said the stranger. ‘Without prejudice, now, a milliner’s pander—will that do?’

I thought it an admissible term, and said so, adding, ‘or a fashion-plate artist?’

‘Surely,’ replied the stranger. ‘A distinction without a difference, is it not?’

No more was said for the moment, while I sat covertly studying the speaker. He reminded me a little of the portraits of Thiers, only without the spectacles. A placid, well-nourished benevolence had been his prominent feature, were it not somehow for the qualification of the eyes. Those were as perpetually alert, busy, observant, as the rest was seemingly supine. They appeared to ‘peck’ for interests among the moving throng, as a hen pecks for scattered grain.

‘Wonderful hands,’ he said suddenly, coming back to the artist. ‘Do you notice anything characteristic about them now?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘What?’

He did not answer, but applied for a refreshing moment or two to his grenadine.

‘Ah!’ he said, leaning back again, with a relishing motion of his lips. ‘A comfortable seat and a cool glass, and we have here the best café-chantant in the world.’

‘Well, it suits me,’ I agreed—‘to pass the time.’

‘Ah!’ he said, ‘your friend is unpunctual?’

I yawned inexcusably.

‘He always is. What would you think of an appointment, sir, three days overdue?’

‘I should think of it with philosophy, having the Ritz cuisine and cellar to fall back upon.’

I turned to him interestedly, my hands behind my head.

‘You have?’

‘No, but you,’ said he.

I was a bit puzzled and amused; but curious, too.

‘You are not staying at the Ritz?’ I asked. He shook his head good-humouredly. ‘Then how do you know I am?’

‘There is not much mystery in that,’ said he. ‘You happened to be standing on the steps when I happened to be passing. The rest you have admitted.’

‘And among all these’—I waved my hand comprehensively—‘you could remember me from that one glimpse?’

He laughed, but again ignored my question.

‘How did you know,’ I persisted, ‘that my friend was a man?’

‘You yourself,’ said he, ‘supplied the gender.’

‘But not in the first instance.’

‘No, not in the first instance,’ he agreed, and said no more.

‘You don’t like the Ritz?’ I asked after an interval, just to talk and be talked to. I was horribly bored, that is the truth, by my own society; and here was at least a compatriot to share some of its burden with me.

‘I never said so,’ he answered. ‘But I confess it is too sumptuous for me. I lodge at the Hôtel Montesquieu, if you would know.’

‘Where is that, may I ask?’

‘It is in the Rue Montesquieu, but a step from here.’

‘I should like, if you don’t mind, to hear something of it. I am at the Ritz, true, but in a furiously economical mood.’

‘Certainly,’ he answered, with perfect good-humour. ‘It would not suit all people; it does not even figure in the guides; but for those of an unexacting disposition—well it might serve—to pass the time. You can have your good bedroom there and your adequate petit déjeuner—nothing more. For meals, there is a Duval’s across the road, or, more particularly, the Restaurant au Boeuf à la mode in the Rue de Valois close by, where such delicacies may be tasted as sole à la Russe, or noisettes d’agneau à la Réjane. Try it.’

I was half thinking I would, and wondering how I could express my sense of obligation to my new acquaintance, when a sudden crash and scream in the road brought us both to our feet. The hat-sketcher, having finished with his task and gone, had stepped thoughtlessly off the kerb right under the shafts of a passing cab.

For a tranquil body, my companion showed the most curious excitement over the accident. Uttering broken exclamations of reproof and concern, he hurried down, as fast as his bulk would permit him, to the scene of the mishap, about which a crowd was already swarming. I could see little of what followed; but, the press after a time dispersing, I made shift to inquire of an onlooker as to the nature of the victim’s hurt, and was told that the man had been taken off to the St Antoine Hospital in the very cab which had run him down, my friend of the Panama hat accompanying him. And so there for the moment our acquaintance ended.

But we met again at the Montesquieu—whither I had actually transferred my quarters in the interval—a day or two later. He came down into the hall just as I had entered it from the street, and greeted me and pressed my arm paternally.

‘But this will not do at all,’ he said. ‘This will not do at all,’ and summoned the hôtelier from his little dark room off the passage.

‘I am sorry, Monsieur,’ he said, when the bowing goodman appeared, ‘to find such scant respect paid to my recommendation. If this is the treatment accorded to my patronage, I must convey it elsewhere.’

The proprietor was quite amazed, shocked, confounded. What had he done to merit this severe castigation from M. Le Sage? If M. le Baron would but condescend to particularise his offence, the resources of his establishment were at M. le Baron’s command to remedy it.

‘That is easily specified,’ was M. le Baron’s answer. ‘I sing the modest praises of your hotel to my friend, Mr Bickerdike; on the strength of these my friend decides to give you a trial. What is the result? You put him into number 19, where the aspect is gloomy, where the paper peels off the wall; where to my certain suspicion there are bugs.’

I laughed, not quite liking this appropriation, but the landlord was profuse in his apologies. Not for a moment had he guessed that I was a friend of M. le Baron Le Sage; I had not informed him of the fact; it was a mere question of expediency: Number 19 happened to be the only room vacant at the moment; but since—in short, I was transferred straightway to a very good appartement in the front, where were ample space and comfort, and a powder-closet to poke my head into if I wished, and invoke the ghosts of the dead lords of Montesquieu, whose HÔtel this had once been.

Now I should have been grateful for M. le Baron’s friendly offices, and I hope I was, but with a dash of reservation. I did not know what to make of him, in fact, and the uncertainty kept me on my guard. Nor was I the more reassured upon his commiserating me presently on the fact of my friend, Mr Kennett, not having yet turned up. So he had found out my friend’s name? That might be possible through an inquiry at the Ritz, where Kennett was expected. But why was he interested in inquiring at all? Then, as to my own name; he might have ascertained that, of course, of my present landlord—a pardonable curiosity, only somehow coloured by his unauthorised examination of my room. What had he wanted in there in. the first instance? On the other hand, he was evidently held, for whatever reason, in high respect by the proprietor; and if the reason itself was to seek for me, I had certainly no grounds for suspecting its adequate claims. He appeared to be a man of education and some distinction, not to speak of his title, which, however, might be territorial and of small account. And, assuredly, he did not seem French, unless by deliberate adoption. His speech, appearance, habit of mind, were all as English as the shoes he wore on his feet.

I asked him, on that day of his service to me, how it had gone with the poor hat-sketcher whom, I had understood, he had accompanied to the hospital. He seemed to regard my question as if for a moment it puzzled him, and then he answered:

‘O, the artist! O, yes, to be sure. I accompanied him, did I? Yes, yes. An old house this, Mr Bickerdike—a fragment of old Paris. If there is nothing more I can do for you, I think I will be going.’

So it always was on the few further occasions which brought us together. He could not, or would not, answer a direct question directly; he seemed to love secrecy and evasion for their own sake, and for the opportunity they gave him for springing some valueless surprises on the unsuspecting. Well, he should not have his little vanity for me. There is nothing so tiresome as that habit of meaningless reserve, of hoarding information which there can be no possible objection to disseminating; but some people seem to have it. I responded by asking no more questions of M. le Baron, and I only hope my incuriosity disappointed him. The next day, or the day after, Kennett turned up, and I left the Montesquieu for my original quarters.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_59f079da-1e98-5877-8335-e3f63082287f)

MY SECOND MEETING WITH THE BARON (#ulink_59f079da-1e98-5877-8335-e3f63082287f)

(From Mr Bickerdike’s Manuscript)

IT might have been somewhere near the anniversary of my first meeting with the Baron when I came upon him again—in London this time. I had been lunching at Simpson’s in the Strand, and, my meal finished, had gone up into the smoking-room for a coffee and liqueur. This is a famous corner of a famous caravansary, being dedicate, like no other smoking-room I know, to the service of the most ancient and most royal game of chess, many of whose leading professors forgather therein, as it were, in an informal club, for the mixed purposes of sociability and play. There one may watch astounding mental conflicts which leave one’s brain in a whirl; or, if one prefers it, may oneself join issue in a duel, whether for glory or profit; or, better still, like Gargantua, having a friend for adversary, for the mere serious diversion of the game, and for its capacity for giving a rare meditative flavour to one’s tobacco. The room, too, for such a haunt of gravity, is a cheerful room, with its large window overlooking the Strand, and one may spend a postprandial hour there very agreeably, and eke very gainfully if one takes an idler’s interest in other people’s problems. That I may confess I do, wherefore Simpson’s is, or was, a fairly frequent resort of mine.

Now, on this occasion I had hardly entered the room when my eyes fell on the figure of M. le Baron sitting profoundly absorbed over a game with one in whom I recognised a leading master in the craft. I knew my friend at once, as how could I fail to, for he sat before me in every detail the stranger of the Café l‘Univers—bland, roomy, self-possessed, and unchanged as to his garb. I would not venture to break into his preoccupation, but passed him by and took a convenient seat in the window.

‘Stothard has found his match,’ remarked a casual acquaintance who lounged near me, nodding his head towards the pair.

‘Who is it?’ I asked. ‘Do you know?

‘I know his name,’ was the answer, ‘Le Sage, an out-of-pocket French Baron; but that’s all.’

‘O! out of pocket, is he?’

‘I’ve no right to say it, perhaps, but I only surmise—he’ll play you for a half-crown at any time, if you’re rash enough to venture. He plays a wonderful game.’

‘Is he new to the place?’

‘O, no! I’ve seen him here frequently, though at long intervals.’

‘Well, I think I’ll go and watch them.’

Their table was against the wall, opposite the window. One or two devotees were already established behind the players, mutely following the moves. I took up a position near Le Sage, but out of his range of vision. He had never, to my knowledge, so much as raised his face since I entered the room; intent on his game, he appeared oblivious to all about him. Yet the moment I came to a stand, his voice, and only his voice, accosted me—

‘Mr Bickerdike? How do you do, sir?’

I confess I was startled. After all, there was something disconcerting about this surprise trick of his. It was just a practised pose, of course; still, one could not help feeling, and resenting in it, that impression of the preternatural it was no doubt his desire to convey. I responded, with some commonplace acknowledgment, to the back of his head, and no more was spoken for the moment. Almost immediately the game came to an end. M. le Baron sat back in his chair with a ‘My mate, I think?’—a claim in which his opponent acquiesced. Half the pieces were still on the board, but that made no difference. Your supreme chess expert will foresee, at a certain point in the contest, all the possible moves to come or to be countered, and will accept without dispute the inevitable issue. The great man Stothard was beaten, and acknowledged it.

M. le Baron rose from his seat, and turned on me with a beaming face.

‘Happy to renew your acquaintance, Mr Bickerdike,’ he said. ‘You are a student of the game?’

‘Not much better, I think,’ I answered. ‘I am still in my novitiate.’

‘You would not care—?’

‘O, no, I thank you! I’m not gull enough to invite my own plucking.’

It was a verbal stumble rather than a designed impertinence on my part, and I winced over my own rudeness the moment it was uttered, the more so for the composure with which it was received.

‘No, that would be foolish, indeed,’ said M. le Baron.

I floundered in a silly attempt to right myself.

‘I mean—I only meant I’m just a rotten muff at the game, while you—’ I stuck, at a loss.

‘While I,’ he said with a smile, ‘have just, like David, brought down the giant Stothard with a lucky shot.’

He touched my arm in token of the larger tolerance; and, in some confusion, I made a movement as of invitation, towards the table in the window.

‘I am obliged,’ he said, ‘but I have this moment recalled an appointment.’ ‘So,’ I thought, ‘in inventing a pretext for declining, he administers a gentle rebuke to my cubbishness.’ ‘You found your friend, I hope,’ he asked, ‘when you left the Montesquieu on ‘that occasion?’

‘Kennett? Yes,’ I answered; and added, moved to some expiatory frankness; ‘it is odd, by the by, M. le Baron, that our second meeting should associate itself with the same friend. I am going down tomorrow, as it happens, on a visit to his people.’

‘No,’ he said: ‘really? That is odd, indeed.’

He shook hands with me, and left the room. Standing at the window a moment after, I saw him going City-wards along the Strand, looking, with his short thick legs and tailed morning coat, for all the world like a fat jaunty turtle on its way to Birch’s.

Now I fancied I had seen the last of the man; but I was curiously mistaken. When I arrived at Waterloo Station the next day, there, rather to my stupefaction, he stood as if awaiting me, and at the barrier—my barrier—leading to the platform for my train, the two o’clock Bournemouth express. We passed through almost together.

‘Hullo!’ I said. ‘Going south?’

He nodded genially. ‘I thought, with your permission, we might be travelling companions.’

‘With pleasure, of course. But I go no further than the first stop—Winton.’

‘Nor I.’

‘O, indeed? A delectable old city. You are putting up there?’

‘No, O no! My destination, like yours, is Wildshott.’

‘Wildshott! You know the Kennetts then?’

‘I know Sir Calvin. His son, your friend, I have never met. It is odd, as you said, that our visits should coincide.’

‘But you must have known yesterday—if you did not know in Paris. Why in the name of goodness did you not—’ I began; and came to a rather petulant stop. This secrecy was simply intolerable. One was pulled up by it at every turn.

‘Did I not?’ he said blandly. ‘No, now I come to think of it— O, Louis, is that an empty compartment? Put the rugs in, then, and the papers.’

He addressed a little vivid-eyed French valet, who stood awaiting his coming at an opened door of a carriage. Le Sage climbed in with a breathing effort, and I followed sulkily. Who on earth, or what on earth, was the man? Nothing more nor less than what he appeared to be, he might have protested. After all, not himself, but common gossip, had charged him with necessitousness. He might be as rich as Croesus, for all I knew or he was likely to say. Neediness was not wont to valet it, though insolvency very well might. But he was a friend of Sir Calvin, a most exclusive old Bashaw; and, again, he was said to play chess for half-crowns. O! it was no good worrying: I should find out all about him at Wildshott. With a grunt of resignation I sank into the cushions, and resolutely put the problem from me.

But the fellow was an engaging comrade for a journey—I will admit so much. He was observant, amusing, he had a fund of good tales at his command, and his voice, without unpleasant stress; was softly penetrative. Adapted to anecdote, moreover, his habit of secrecy, of non-committal, made for a sort of ghostly humour which was as titillating as it was elusive; and the faint aroma of snuff, which was never absent from him, seemed somehow the appropriate atmosphere for such airy quibbles. It surrounded him like an aura—not disagreeably; was associated with him at all times—as one associates certain perfumes with certain women—a particular snuff, Macuba I think it is called, a very delicate brand. So he is always recalled to me, himself and his rappee inseparable.

CHAPTER III (#ulink_2a806f0f-aaa4-581d-84ac-17820b2e62d4)

WILDSHOTT (#ulink_2a806f0f-aaa4-581d-84ac-17820b2e62d4)

Wildshott, the Hampshire seat of the Kennetts, stands off the Winton-Sarum road, at a distance of some six miles from the former, and some three and a half from the sporting town of Longbridge, on the way to the latter. The house is lonely situated in wild but beautiful country, lying as it does in the trough of the great downs whose summits hereabouts command some of the most spacious views in the County. A mile north-east, footing a gentle incline, shelters the village of Leighway; less than a mile away, in a hollow of the main road, stands a wayside tavern called the Bit and Halter; and, with these two exceptions, no nearer neighbour has Wildshott than the tiny Red Deer inn, which perches on a high lift of the downs a mile and a half distant, rising north.

The stately, wrought-iron gates of Wildshott open from the main road. Thence a drive of considerable extent reaches to the house, which is a rectangular red-brick Jacobean structure, with stone string-courses and a fine porch, having a great shell over it. There are good stables contiguous, and the grounds about are ample and well timbered—almost too well timbered, it might be thought by some people, since the closeness of the foliage gives an effect of gloom and solemnity to a building which, amid freer surroundings, should have nothing but grace and frankness to recommend it. But settled as it is in the wash of the hills, with their moisture draining down upon it, growth and greenness have become a tradition of its life, and as such not to be irreverently handled by succeeding generations of Kennetts.

All down the west boundary of the upper estate—which, to its northernmost limit, breaks upon that bare hill on whose summit, at closer range now, the little Red Deer inn sits solitary—runs a wide fringe of beech-wood, which is continued to the high road, and thence, on the further side, dispersed among the miscellaneous plantations which are there situated. The highway itself roughly bisects the property—the best of whose grass and arable lands are contained in the southern division—and can be reached from the house, if one likes, through the long beech-thicket by way of a narrow path, which, entering near the stables, runs as far as the containing hedge, in which, at some fifty yards from the main entrance, is a private wicket, leading down by a couple of steps to the road. This path is known, through some superstitious association, as the Bishop’s Walk, and is little used at any time, the fact that it offers a short cut from the house to the lower estate being regarded, perhaps, as inadequate compensation for its solitariness, its dankness, and the glooms of the packed foliage through which it penetrates. Opposite the wicket, across the road, an ordinary bar-gate gives upon a corresponding track, driven through the thick of a dense coppice, which, at a depth of some two hundred feet, ends in the open fields. It is useful to bear in mind these local features, in view of the event which came presently to give them a tragic notoriety.

At Winton a wagonette met the two gentlemen, and they were landed at Wildshott soon after four o’clock. Bickerdike was interested to discover that they were the only guests. He was not surprised for himself, since he and Hugo Kennett were on terms of unceremonial intimacy. He did wonder a little what qualities he and the Baron could be thought to possess in common that they should have been chosen together for so exclusive an invitation. But no doubt it was pure accident; and in any case there was his friend to explain. He was a bit down in the mouth, was Hugo—for any reason, or no reason, or the devil of a reason; never mind what—and old Viv was always a tower of strength to him in his moods—hence old Viv’s citation to come and ‘buck’ his friend, and incidentally to enjoy a few days’ shooting, which accounted for one half of the coincidence. Old Viv accepted his part philosophically; it was not the first time he had been called upon to play it with this up and down young officer, whose temporal senior he was by some six years, and whose elder, in all questions of sapience and self-sufficiency, he might have been by fifty. He did not ask what was the matter, but he said ‘all right’, as if all right were all reassurance, and gave a little nod to settle the matter. He had a well-looking, rather judicial face, clean shaven, a prim mouth, a somewhat naked head for a man of thirty, and he wore eyeglasses on a neatly turned nose, with a considerable prominence of the organ of eventuality above it. The complacent bachelor was writ plain in his every line. And then he inquired regarding the Baron.

‘O! I know very little about him,’ was young Kennett’s answer. ‘I believe the governor picked him up in Paris originally, but how or where I can’t say. He’s a marvel at chess; and you remember that’s the old man’s obsession. They’re at it eternally while he’s down here.’

‘This isn’t his first visit then?’

‘No, I believe not; but it’s the first time I’ve seen him. I’m quoting Audrey for the chess. Why, what’s the matter? Is anything wrong with him?’

‘There you go, you rabbit! Who said anything was wrong with him? I’ve met him before, that’s all.’

‘Have you? Where?’

‘Why, in Paris. You remember the Montesquieu, and my French Baron?’

‘I remember there was a Baron. I don’t think you ever told me his name.’

‘Well, it was Le Sage, and this is the man.’

‘Is it? That’s rather queer.’

‘What is?’

‘The coincidence of your meeting again like this.’

‘O, as to that, coincidence, you know, is only queer till you have traced back its clues and found it inevitable.’

‘Well, that’s true. You can trace it in his case to the governor’s being down with the gout again, and confined to the house, and wanting something and somebody to distract him.’

‘There you are, you see. He thought of chess, and thought of this Le Sage, and wrote up to him on the chance. Your father probably knows more about his movements than we do. So we’re both accounted for. No, what is queer to me is the man’s confounded habit of secrecy. Why didn’t he say, when I met him in Paris, that the friend I was waiting for was known to him? Why didn’t he admit yesterday, admit until we actually met on the platform today, that we were bound for the same place? I hate a stupidly reticent man.’

Kennett laughed, and then frowned, and turned away to chalk his cue. The two men were in the billiard-room, playing a hundred up before dinner.

‘Well,’ he said, stooping to a losing hazard, ‘I hope a fellow may be a good fellow, and yet not tell all that’s in him.’

‘Of course he may,’ answered Bickerdike. ‘Le Sage, I’m sure, is a very good fellow, a very decent old boy, and rare company when he chooses—I can answer for that. But there’s a difference between telling all that’s in one and not telling anything.’

‘Well, perhaps he thinks,’ said the other impatiently, ‘that if he once opened the sluice he’d drain the dammed river. Do let him alone and attend to the game.’

Bickerdike responded, unruffled. He had found his friend in a curiously touchy state—irritable, and nervous, and moody. He had known him to be so before, though never, perhaps, so conspicuously. Hugo was temperamentally high-strung, and always subject to alternations of excitement and despondence; but he had not yet exhibited so unbalanced a temper as he seemed inclined to display on this occasion. He was wild, reckless, dejected, but seldom normal, appearing possessed by a spirit which in turns exalted or depressed him. What was wrong with the boy? His friend, covertly pondering the handsome young figure, found sufficient solution in the commonplace. He was in one of his nervous phases, that was all. They would afflict men subject to them at any odd time, and without apparent provocation. It was one of the mysteries of our organic being—a question of misfit somewhere between spirit and matter. No one looking at the young soldier would have thought him anything but a typical example of his kind—constitutionally flawless, mentally insensitive. He belonged to a crack regiment, and was popular in it; was tall, shapely-built, attractive, with a rather girlish complexion and umber-gold hair—a ladies’ man, a pattern military man, everything nice. And yet that demon of nerve worked in him to his perfection’s undoing. Perhaps it was the prick of conscience, like a shifting grit in one’s shoe, now here, now there, now gone—for the boy had quite fine impulses for a spoilt boy, a spoilt child of Fortune—and spoilt, like Byron by his mother, in the ruinous way. His father, the General, alternately indulgent and tyrannical, was the worst of parents for him; he had lost his mother long ago; his one sister, flippant, independent—undervalued, it may be, and conscious of it—offered no adequate substitute for that departed influence. And so the good in Hugo was to his own credit, and stood perhaps for more than it might have in another man.

His father, Sir Calvin—he had got his K.C.B., by the way, after Tel-el-Kebir in ’82, in reward for some signal feat of arms, and at the expense of his trigger-finger—was as proud as sin of his comely lad, and blind to all faults in him which did not turn upon opposition to himself. He designed great connexions for the young man, and humoured his own selfishness in the prospect. He was a martinet of fifty-five, with a fine surface polish and a heart of teak beneath it, a patrician of the Claudian breed, irascible, much subject to gout for his past misdeeds, and an ardent devotee of the game of chess, at which he could hold his own with some of the professed masters. It was that devotion which had brought him fortuitously acquainted with the French Baron—a sort of technical friendship, it might be called—and which had procured the latter an occasional invitation of late to Wildshott. Le Sage came for chess, but he proved very welcome for himself. There was a sort of soothing tolerance about him, the well-informed urbanity of a polished man of the world, which was as good as a lenitive to the splenetic invalid. But nobody, unless it were Sir Calvin himself, appeared to know anything concerning him; whether he were rich or indigent; what, if dependent on his wits, he did for a living; what was the meaning or value of his title in an Englishman, if English he were; whether, in short, he were a shady Baron of the chevalier d’ industrie order, or a reputable Baron, with only some eccentricities to mark him out from the common. One of these, not necessarily questionable, was his sly incommunicativeness; another was his fondness for half-crowns. He invariably, whether with Sir Calvin or others, made that stake, no more and no less, a condition of his playing at all, and for the most part he carried it off. Vivian Bickerdike soon learned all that there was to be told about him, and he was puzzled and interested—‘intrigued’, as they would say in the horrible modern phrase. But being a young man of caution, in addition to great native curiosity, he kept his wits active, and his suspicions, if he had any, close.

The game proceeded—badly enough on the part of Hugo, who was generally a skilful player. He fouled or missed so many shots that his form presently became a scandal. ‘Phew!’ whistled his opponent, after a peculiarly villainous attempt; ‘what’s gone wrong with you?’

The young man laughed vexedly; then, in a sudden transition to violence, threw his cue from him so that it clattered on the floor.

‘I can’t play for nuts,’ he said. ‘You must get somebody else.’

‘Hugh,’ said his friend, after a moment or two of silence, ‘there’s something weighing on your mind.’

‘Is there?’ cried the other jeeringly. ‘I wonder.’

‘What is it? You needn’t tell me.’

‘O! thank you for that. I tell you what, Viv: I dreamed last night I was sitting on a barrel of gunpowder and smoking a cigarette, and the sparks dropped all about. Didn’t I? That’s what I feel, anyhow. Nerves, all nerves, my boy. O! shut up that long mug, and talk of something else. I told you I was off colour when I wrote.’

‘I know you did, and I came down.’

‘Good man. You’ll be in at the kill. There’s going to be a most infernal explosion—pyrotechnics galore. Or isn’t there? Never mind.’

He appeared to Bickerdike to be in an extraordinary state, verging on the hysterical. But no more was said, and in a few moments they parted to dress for dinner.

M. le Baron, coming up to his room about the same time and for the same purpose, was witness of a little stage comedy, which, being for all his bulk a light treader, he surprised. The actors were his valet Louis and an under-housemaid, the latter of whom was at the moment depositing a can of hot water in the washing basin. He saw the lithe, susceptible little Gascon steal from his task of laying ready his master’s dress clothes, saw him stalk his quarry like a cat, pounce, enfold the jimp waist, heard the startled squeal that followed, a smack like a hundred kisses, a spitting sacré chein! from the discomfited assailant, as he staggered back with a face of fury and a hand held to his ear, and, seeing, stood to await the upshot, a questioning smile upon his lips. Both parties realised his presence at the same instant, and checked the issue of hot words which was beginning to join between them. The girl, giving a defiant toss to her chin, hurried past Le Sage and out of the room; M. Louis Cabanis returned to his business with the expression of a robbed wild-cat.

Le Sage said nothing until he was being presently helped on with his coat, and then suddenly challenging the valet, eye to eye, he nodded, and congratulated him:

‘That is better, my friend. It is not logical, you know, for the injurer to nurse the grievance.’

The Gascon looked at his master gravely.

‘Will you tell me who is the injurer, Monsieur?’

‘Surely,’ answered Le Sage, ‘it cannot be she, in these first few hours of your acquaintance?’

‘But if she had appeared to encourage me, Monsieur?’

The Baron laughed.

‘The only appearance to be trusted in a pretty woman, Louis, is her prettiness.’

‘Monsieur, is her ravishing loveliness.’

‘Well, well, Louis, as you will. Only bear it no grudge.’

He turned away from a parting keen scrutiny of the dark, handsome face, and left the room, softly carolling. The little episode had amused rather than surprised him. Certainly it had seemed to point, in respect of time, to a quite record enslavement on the Gascon’s part; but then the provocation to that passionate impressionable nature! For the girl had been really amazingly pretty, with that cast of feature, that Hebe-like beauty of hair and eye and complexion about whose fascination no two properly constituted minds could disagree. She was a domestic servant—and she was a young morning goddess, fresh from the unsullied dawn of Nature, a Psyche, a butterfly, a Cressid like enough. ‘If I were younger,’ thought Le Sage, ‘even I!’ and he carolled as he went down to dinner.

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_1735d5d9-0e4c-5192-8aa3-d9a275d2e986)

I AM INTERESTED IN THE BARON (#ulink_1735d5d9-0e4c-5192-8aa3-d9a275d2e986)

(From the Bickerdike MS.)

I SEEMED conscious somehow, at dinner on the night of our arrival, of a feeling of electricity in the domestic atmosphere. Having no clue, such as the later course of events came to supply, to its origin, I diagnosed it, simply and vulgarly, as the vibrations from a family jar, of the sort to which even the most dignified and well-regulated households cannot always rise superior. Sir Calvin himself, exacting and domineering, could never at the best of times be considered a tactful autocrat: a prey to his hereditary foe, he appeared often to go out of his way to be thought detestable. When such was the case, his habit of harping on grievances could become an exquisite torture, his propensity for persisting in the unwelcome the more he saw it resented a pure malignancy. On this occasion, observing an obvious inclination in his son, my friend, to silence and self-obliteration, he took pleasure in drawing him out, with something of the savagery, I could not but think, of a fisherman who wrenches an obstinate hermit crab from its borrowed shell for bait. I saw how poor Hugh was rasped and goaded, but could do no more than take upon myself, where I could, the burden of response. Believing at the time that this aggravated fencing between the two was a part, or consequence, of some trouble, the serious nature of which might or might not have been implied in my friend’s recent outburst, I made and could make but an inefficient second; yet, even had I known, as I came to know, that my surmise was wrong, and that the father’s persistence was due to nothing but a perverse devil of teasing, it is not clear to me how else I could have helped the situation. I could not have hauled my host by the ears, as I should have liked to do, over his own dining-room table.

But the sense of atmospheric friction was not confined to these two. In some extraordinary way it communicated itself to the servants, the very butler, our young hostess. I had not seen Audrey at tea, and now greeted her for the first time. She came in late, to find us, by the Bashaw’s directions, already seated, and to suffer a sharp reprimand for her unpunctuality which brought a flush to her young rebellious cheek. Nor did I better things, so far as she was concerned, by an ostentatious display of attentions; she seemed to resent my sympathy even more than the harshness which had provoked it. It is the way of cats and women to tear the hand that would release them from the trap.

The dinner, in short, began very uncomfortably, with an irascible host, a moody son, and an offended daughter, the butler taking his cue from his master, and the servants from the butler. They waited nervously, and got in one another’s way, only the more flurriedly for their whispered harrying by the exacerbated Cleghorn. I was surprised, I confess, by the change in that usually immaculate dignitary. The very type and pattern of his kind, correct, imperturbable, pontifical, I had never before known Cleghorn to manifest the least sign of human emotion, unless it were when Mr Yockney, the curate from Leighway, had mixed water with his Château Margaux 1907. Now, preposterous as it appeared, I could have believed the great man had been crying. His globous eyes, his mottled cheeks, bore suspicious evidences of the fact; his very side-whiskers looked limp. Surely the domestic storm, if such, which had rocked the house of Kennett must have been demoralising to a hitherto unknown degree.

It was the Baron who redeemed the situation, winning harmony out of discord. He had, to do him justice, the reconciliatory faculty, chiefly, I think, because he could always find, as one should, a bright interest in differences of opinion instead of a subject for contention. I never knew him, then or thereafter, to be ruffled by opposition or contradiction. He accepted them placidly, as constituting possible rectifications of his own argumentative frontiers.

His opportunity came with a growl of Sir Calvin’s over the lateness of the evening papers. The General had been particularly curious to hear the result of a local trial, known as the Antonferry Bank robbery case, which was just reaching its conclusion, and it chafed him to be kept waiting. Le Sage asked for information, and the supplying it smoothed the troubled waters. There is a relish for most people in being the first to announce news, whether good, bad, or indifferent.

The case, as stated, was remarkable for nothing but the skill with which it had been unravelled. A Bank in Antonferry—a considerable market town lying some eight or nine miles north of Wildshott—had been robbed, and the question was by whom. That question had been answered in the upshot by an astute Scotland Yard detective, who, in spite of the obloquy thrown upon his kind by Mr Sherlock Holmes, had shown considerable sagacity in tracing the crime to its source in the Bank’s own manager—a startling dénouement. The accused, on the strength of this expert’s evidence, had been committed to stand his trial at Winton Quarter Sessions, and it was the issue of that event which was interesting Sir Calvin. He had had some dealings with the Bank in question, and had even been brought into some personal contact with the delinquent official.

‘It seems,’ he ended, ‘that there can be no doubt about the verdict. That Ridgway is a clever dog.’

‘The detective?’ queried Le Sage; and the General nodded.

‘The sort I should be sorry, if a thief, to have laid on my trail.’

‘But supposing you left none?’ questioned the Baron, with a smile.

‘Ah!’ said Sir Calvin, having nothing better to reply.

‘I have often thought,’ said Le Sage, ‘that if crime realised its own opportunities, there would be no use for detectives at all.’

‘Eh? Why not?’ asked his host.

‘Because there would be nothing to find out,’ answered the Baron.

‘How d’ye mean? Nothing to find out?’

‘Nothing whatever. My idea, now, of a successful crime is not a crime which baffles its investigators, but a crime which does not appear as a crime at all.’

‘Instance, M. le Baron,’ I ventured to put in.

‘Why,’ said Le Sage good-humouredly, ‘a dozen may well present themselves to a man of average inventive intelligence. Direct murder, for example—how crude! when a hundred means offer themselves for procuring plausible ends to life. Tetanus germs and an iron tack; ptomaine, that toxicologic mystery, so easy to introduce; the edge of a cliff and a windy day; a frayed picture cord; a loosened nut or two; a scrap of soap left on the boards by an opened window—given adroitness, timeliness, a little nerve, would not any of these do?’

Audrey drew back in her chair, with a flushed little laugh.

‘What a diabolical list!’ she said, and made a face as if she had taken medicine.

‘Yes,’ said I. ‘But after all, Baron, this is no more than generalising.’

‘You want a concrete instance?’ he answered, beaming on me. ‘What do you say then to a swimmer being awarded the Humane Society’s certificate for attempting to save the life of a man whom he had really drowned? It needs only a little imagination to fill in the details.’

‘That is good,’ I admitted. ‘We put one to your credit.’

‘Again,’ said the Baron, ‘I offer the case of a senseless young spendthrift. He gambles, he drinks, his life is a bad life from the insurance company’s point of view. When hard pressed, he is lavish with his IOUs; when flush of money he redeems them; he pays up, he throws the slips into the fire with hardly a glance at them. One who holds a good deal of his paper observes this, and acts accordingly. He preserves the original securities, and on redemption, offers forgeries in their place, which he is careful to see destroyed. On the death of the young man he puts in his claim on his estate on the strength of the indisputable original documents. Thus he is paid twice over, without a possibility of any suspicion arising.’

‘But one of the forged IOUs,’ said Audrey, ‘had been carried up the chimney without catching alight, and had been blown through the open window of the young man’s family lawyer, who had kept it as a surprise.’

There was a shout of laughter, in which the Baron joined.

‘Bravo, Audrey!’ cried her brother. ‘What about your average inventive intelligence, Baron?’

‘I said, specifically, a man’s,’ pleaded Le Sage. ‘Women, fortunately for us, are not eligible for the detective force.’

Audrey laughed at the compliment, but I think she liked the Baron for his pleasant good-nature. About that, for my part, I kept an open mind. Had he really invented these cases on the spur of the moment, or could it be possible that they touched on some experience of his own? One could not say, of course; but one could bear the point in mind.

The dinner went cheerfully enough after this jeu d’esprit of Audrey’s. That had even roused Hugh from his glooms, and to quite exaggerated effect. He became suddenly talkative where he had been taciturn, and almost boisterously communicative where he had been reserved. But I noticed that he drank a good deal, and detected curiously, as I thought, a hint of desperation under his feverish gaiety.

In all this, it may be said, I was appropriating to myself, without authority, a sort of watching brief on behalf of a purely chimerical client. I had no real justification for suspecting the Baron, either on his own account, or in association with my friend’s apparent state; it was presumptive that Sir Calvin knew at least as much about the man as I did; still, I thought, so long as I preserved my attitude of what I may call sympathetic vigilance à la sourdine, nothing could be lost, and something even might be gained. The common atmosphere, perhaps, affected me with the others, and inclined me to an unusually observant mood; a mood, it may be, prone to attach an over-importance to trifles. Thus, I could find food for it in an incident so ordinary as the following. There was a certain picture on the wall, a genre painting, to which Le Sage, sitting opposite it, referred in some connexion. Sir Calvin, replying, remarked that so-and-so had declared one of the figures to be out of proportion—too short or too tall, I forget which—and, in order to measure the discrepancy, interposed, after the manner of the connoisseur, a finger between his eye and the subject. There was nothing out of the common in the action, save only that the finger he raised was the second finger of his right hand, the first having been shot away in some long-past engagement; but it appeared, quite obviously to me, to arrest in a curious way the attention of the visitor. He forgot what he was saying at the moment, his speech tailed off, he sat gazing, as if suddenly fascinated, not at the picture but at the finger. The next instant he had caught up and continued what he was observing; but the minute incident left me wondering. It had signified, I was sure, no sudden realization of the disfigurement, since that must have been long known to him, but of some association with it accidentally suggested. That, in that single moment, was my very definite impression—I could hardly have explained why at the time; but there it was. And I may say now, in my own justification, that my instinct, or my intuition, was not at fault.

Once or twice later I seemed to catch Le Sage manoeuvring to procure a repetition of the action, but without full success; and soon afterwards the two men fell upon the ever-absorbing subject of chess, and lapsed into vigorous discussion over the relative merits of certain openings, such as the Scotch, the Giuoco Piano, the Ruy Lopez attack, Philidor’s defence, and the various gambits; to wit, the Queen’s, the Allgaier, the Evans, the Muzio, the Sicilian, and God knows what else. They did not favour the drawing-room for long after dinner, but went off to the library to put their theories into practice, leaving Hugh and me alone with the lady. I cannot admit that I found the subsequent evening exhilarating. Hugh appeared already to be suffering a relapse from his artificial high spirits, and again disturbed me by the capricious oddity of his behaviour. He and his sister bickered, after their wont, a good deal, and once or twice the girl was brought by him near the verge of angry tears, I thought. I never could quite make out Audrey. She seemed to me a young woman of good impulses, but one who was for ever on the defensive against imagined criticism, and inclined therefore, in a spirit of pure perversity, to turn her worst side outermost. Yet she was a really pretty girl, a tall stalk of maiden-hood, nineteen, and athletically modern in the taking sense, and had no reason but to value herself and her attractions at the plain truth they represented. The trouble was that she was underestimated, and I think proudly conscious of the fact. With a father like Sir Calvin, it was, and must be, Hugo first and the rest nowhere. He bullied everyone, but there was no under-suggestion of jealous proprietorship in his bullying of Audrey as there was in his adoring bullying of his son. He did not care whether she felt it or not; with the other it was like a lover’s temper, wooing by chastisement. Nor was Hugo, perhaps, a very sympathetic brother. He could enjoy teasing, like his father, and feel a mischievous pleasure in seeing ‘the galled jade wince’. Audrey, I believe, would have worshipped him had he let her—I had observed how gratified she looked at dinner over his commendation of her jest—but he held her aloof between condescension and contempt, and the two had never been real companions. The long-motherless girl was lonely, I think, and it was rather pathetic; still, she did not always go the right way about it to avoid unfavourable criticism.

We were out for a day in the stubble on the morrow, and I made it an excuse for going to bed betimes. The trial of the Bank-Manager, I may mention by the way, had ended in a verdict of guilty, and a sentence of three years penal servitude. I found, and took the paper in to Sir Calvin before going upstairs. The servants never dared to disturb him at his game.

CHAPTER V (#ulink_23af98b7-fe2b-559a-b433-f4ead3df4707)

THE BARON CONTINUES TO INTEREST ME (#ulink_23af98b7-fe2b-559a-b433-f4ead3df4707)

(From the Bickerdike MS.)

WE were three guns—Hugo, myself, and a young local landowner, Sir Francis Orsden of Audley, whom I had met before and liked. He was a good fellow, though considered effeminate by a sporting squirearchy; but that I could never see. Our shooting lay over the lower estate, from which the harvest had lately been carried, and we went out by the main gates, meeting the head gamekeeper, Hanson, with the dogs and a couple of boy beaters, in the road. Our plan was to work the stubble as far as possible in a south-westerly direction, making for Asholt Copse and Hanson’s cottage, where Audrey and the Baron were to meet us, driving over in a pony trap with the lunch.

I perceived early enough that my chance of a day’s sport wholly untrammelled by scruples of anxiety was destined to be a remote one. Hugh, it had been plain to me from the first, had not mastered with the new day his mood of the night before. His nervous irritability seemed to me even to have increased, and the truth was he was a trying companion. I had already made him some tentative bid for his confidence, but without result; I would not be the one again to proffer my sympathy uninvited. After all, he had asked for it, and was the one to broach the subject, if he wanted it broached. Probably—I knew him—the matter was no great matter—some disappointment or monetary difficulty which his fancy exaggerated. He hated trouble of any sort, and was quite capable of summoning a friend from a sick-bed to salve some petty grievance for him. So I left it to him to explain, if and when he should think proper.

It was a grey quiet day, chill, but without wind; the sort of day on which the echo of a shot might sound pretty deceptively from a distance—a point to be remembered. I was stationed on the left, Orsden on the extreme right, and Hugh divided us. His shooting was wild to a degree; he appeared to fire into the thick of the coveys without aim or judgment, and hardly a bird fell to his gun. Hanson, who kept close behind his young master, turned to me once or twice, when the lie of the ground brought us adjacent, and shook his head in a surprised, mournful way. Once Hugh and I came together at a gap in a hedge. I had negotiated it without difficulty, and my friend was following, when something caught my eye. I snatched at his gun barrel, directing it between us, and on the instant the charge exploded.

‘Good God, man!’ I exclaimed. ‘You?’

Like the veriest Cockney greenhorn, he had been pulling his piece after him by the muzzle, and the almost certain consequence had followed. I stood staring at him palely, and for the moment his face was distorted.

‘Hugh!’ I said stiffly, ‘you didn’t mean it?’

He broke into a mirthless laugh.

‘Mean it, you mug! Of course I didn’t mean it. Why should I?’

‘I don’t know. Mug for saving your life, anyhow!’

‘I’ll remember it, Vivian. I wish I owed you something better worth the paying.’

‘That’s infernal nonsense, of course. Now, look here; what’s it all about?’

‘All what?’

‘You know.’

‘I’ll tell you by-and-by, Viv—on my honour, I will.’

‘Will you? Hadn’t you better go back in the meantime and leave your gun with Hanson?’

‘No; don’t be a fool, or make me seem one. I’ll go more careful after this; I promise you on my sacred word I will. There, get on.’

I was not satisfied; but Hanson coming up at the moment to see what the shot had meant, I could have no more to say, and prepared silently to resume my place.

‘It’s all right, George,’ said his master, ‘only a snap at a rabbit.’

Had he meant to kill himself? If he had, what trouble so much more tragic than any I had conceived must lie at the root of the matter! But I would not dare to believe it; it had been merely another manifestation of the reckless mood to which his spoilt temper could only too easily succumb. Nevertheless, I felt agitated and disturbed, and still, in spite of his promise, apprehensive of some ugly business.

He shot better after this episode, however, and thereby brought some reassurance to my mind. Hanson, that astute gamekeeper, led us well and profitably, and the morning reached its grateful end in that worthy’s little parlour in the cottage in the copse, with its cases of stuffed birds and vermin, and its table delectably laid with such appetising provender as ham, tongue, and a noble pigeon pie, with bottled beer, syphons, and old whisky to supply the welcome moisture. Audrey presided, and the Baron, who had somehow won her liking, and whom she had brought with her in the governess cart, made a cheerful addition to the company. He was brightly interested in our morning’s sport, as he seemed to be generally in anything and everything; but even here one could never make out from his manner whether his questions arose from knowledge or ignorance in essential matters. They were not, I suppose—in conformity with his principle of inwardness—intended to betray; but the whole thing was to my mind ridiculous, like rattling the coppers in one’s pocket to affect affluence. One might have gathered, for all proof to the contrary, that his acquaintance with modern sporting weapons was expert; yet he never directly admitted that he had used them, or was to be drawn into any relation of his personal experiences in their connexion. The subject of poachers was one on which, I remember, he exhibited a particular curiosity, asking many questions as to their methods, habits, and the measures taken to counter their dangerous activities. It was Orsden who mostly answered him, in that high eager voice of his, with just the suspicion of a stammer in it, which I could never hear without somehow being tickled. Hugh took no trouble to appear interested in the matter. He was again, I noticed with uneasiness, preoccupied with his own moody reflections, and was drinking far too much whisky and soda.

The Baron asked as if for information; yet it struck me that his inquiries often suggested the knowledge they purported to seek, as thus:

‘Might it not be possible, now, that among the quiet, respectable men of the village, who attend to their business, drink in moderation, go punctually to church, and are well thought of by the local policeman, the real expert poacher is mostly to be found—the man who makes a study and a business of his craft, and whose depredations, conducted on scientific and meteorological lines, should cause far more steady havoc among the preserves than that wrought by the organised gangs, or by the unprofessional loafer—“moocher”, I think you call him?’

Or thus: ‘This country now, with its mixture of downlands and low woods, and the variety of opportunities they afford, should be, one might imagine, peculiarly suited to the operations of these gentry?’

Or thus: ‘I wonder if your shrewd poacher makes much use of a gun, unless perhaps on a foggy morning, when the sound of the report would be muffled? He should be a trapper, I think, par excellence’—and other proffered hypotheses, seeming to show an even more intimate acquaintance with the minutiae of the subject, such as the springes, nets, ferrets, and tricks of snaring common to the trade—a list which set Orsden cackling after a time.

‘On my word, Baron,’ said he, ‘if it wasn’t for your innocent way of p-putting things, I could almost suspect you of being a poacher yourself.’

Le Sage laughed.

‘Of other men’s games, in books, perhaps,’ he said.

‘Well,’ said Orsden, ‘you’re right so far, that one of the closest and cunningest poachers I ever heard of was a Leighway hedge-carpenter called Cleaver, and he was as quiet, sober, civil-spoken a chap as one could meet; pious, too, and reasonable, though a bit of a village politician, with views of his own on labour. Yet it came out that for years he’d been making quite a handsome income out of Audley and its neighbours—a sort of D-Deacon Brodie, you know. Not one of their preserves, though; you’re at fault there, Baron. Your local man knows better than to put his head into the noose. His dealings are with the casual outsiders, so far as pheasants are concerned. When he takes a gun, it’s mostly to the birds; and of course he shoots them sitting.’

‘Brute!’ said Audrey.

‘Well, I don’t know,’ said the young Baronet. ‘He’s a tradesman, isn’t he, not a sportsman, and tradesmen don’t give law.’

‘How did he escape so long?’ asked the girl.

‘Why, you see,’ answered Orsden, ‘you can’t arrest a man on suspicion of game-stealing with nothing about him to prove it. He must be caught in the act; and if one-third of his business lies in poaching, quite two-thirds lie in the art of avoiding suspicion. Fellows like Cleaver are cleverer hypocrites than they are trappers—J-Joseph Surfaces in corduroys.’

‘Do you find,’ said Le Sage, ‘men of his kind much prone to violence?’

‘Not usually,’ replied Orsden, ‘but they may be on occasion, if suddenly discovered at work with a gun in their hands. It’s exposure or murder then, you see; ruin or safety, with no known reason for anyone suspecting them. I expect many poor innocent d-devils were hanged in the old days for the sins of such vermin.’

‘Yes,’ said Le Sage, ‘a shot-gun can be a great riddler.’

One or two of us cackled dutifully over the jeu de mot. Could we have guessed what tragic application it would receive before the day was out, we might have appreciated it better, perhaps.

I shall not soon forget that afternoon. It began with Audrey and the Baron driving off together for a jaunt in the little cart. They were very merry, and our young Baronet would have liked, I think, to join them. I had noticed Le Sage looking excessively sly during lunch over what he thought, no doubt, was an exclusive discovery of his regarding these two. But he was wrong. They were good friends, and that was all; and, as to the young lady’s heart, I had just as much reason as Orsden—which was none whatever—for claiming a particular share in its interest. Any thought of preference would have been rank presumption in either of us, and the wish, I am sure, was founded upon no such supposition. It was merely that with Hugh in his present mood, the prospect of spending further hours in his company was not an exhilarating one.

He was flushed, and lethargic, and very difficult to move to further efforts when the meal was over; but we got him out at last and went to work. It did not last long with him. It must have been somewhere short of three o’clock that he shouldered his gun and came plodding to me across the stubble.

‘Look here, Viv,’ he said, ‘I’m going home. Make my apologies to Orsden, and keep it up with him; but I’m no good, and I’ve had enough of it.’

He turned instantly with the word, giving a short laugh over the meaning expressed obviously enough, I dare say, in my eyes, and began to stride away.

‘No,’ he called, ‘I’m not going to shoot myself, and I’m not going to let you make an ass of me. So long!’

I had to let him go. Any further obstruction from me, and I knew that his temper would have gone to pieces. I gave his message to Orsden, and we two continued the shoot without him. But it was a joyless business, and we were not very long in making an end of it. We parted in the road—Orsden for the Bit and Halter and the turning to Leighway, and I for the gates of Wildshott. It was near five o’clock, and a grey still evening. As I passed the stables, a white-faced groom came hurrying to stop me with a piece of staggering news. One of the maids, he said, had been found murdered, shot dead, that afternoon in the Bishop’s Walk.

CHAPTER VI (#ulink_616955bf-71dd-5de7-93dc-2e82386d536f)

‘THAT THUNDERS IN THE INDEX’ (#ulink_616955bf-71dd-5de7-93dc-2e82386d536f)

LE SAGE, in the course of a pleasant little drive with Audrey, asked innumerable questions and answered none. This idiosyncrasy of his greatly amused the young lady, who was by disposition frankly outspoken, and whose habit it never was to consider in conversation whether she committed herself or anyone else. Truth with her was at least a state of nature—though it might sometimes have worn with greater credit to itself a little more trimming—and states of nature are relatively pardonable in the young. A child who sees no indecorum in nakedness can hardly be expected to clothe Truth.

‘This Sir Francis,’ asked the Baron, ‘he is an old friend of yours?’

‘O, yes!’ said Audrey; ‘quite an old friend.’

‘And favourite?’

‘Well, he seems one of us, you see. Don’t you like him yourself?’

‘I suppose he and your brother are on intimate terms?’

‘We are all on intimate terms; Hugh and Frank no more than Frank and I.’

‘And no less, perhaps; or perhaps not quite so much?’

‘O, yes they are! What makes you think so? ’

‘Not quite so intimate, I will put it, as your brother and Mr Bickerdike?’

‘I’m sure I don’t know. Hugh is great friends with them both.’

‘Tell me, now—which would you rather he were most intimate with?’

‘How can it matter to me?’

‘You have a preference, I expect.’

‘I certainly have; but that doesn’t affect the question. It was Hugh you were speaking of, not me.’

‘Shall I give your preference? It is for Mr Bickerdike.’

‘Well guessed, Baron. Am I to take it as a compliment to my good taste?’

‘He is a superior man.’