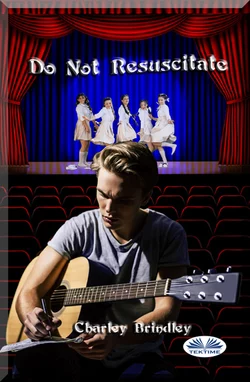

Do Not Resuscitate

Charley Brindley

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 313.53 ₽

Издательство: TEKTIME S.R.L.S. UNIPERSONALE

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A dying man tells his great granddaughter that he has signed a Do Not Resuscitate document, giving instructions for medical personal to let him die if he’s determined to be brain dead.