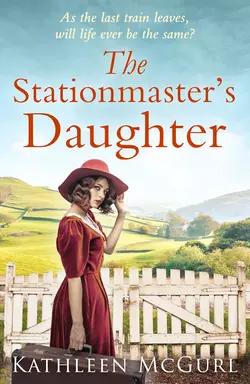

The Stationmaster’s Daughter

Kathleen McGurl

‘Absolutely broke my heart… I didn’t emerge for breath until I’d tearfully finished the last page. Wonderful. ’ Being Anne, 5 stars Dorset, 1935. Stationmaster Ted has never cared much for romance. Occupied with ensuring England’s most beautiful railway runs on time, love has always felt like a comparatively trivial matter. Yet when he meets Annie Galbraith on the 8. 42 train to Lynford, he can’t help but instantly fall for her. But when the railway is forced to close and a terrible accident occurs within the station grounds, Ted finds his job and any hope of a relationship with Annie hanging in the balance… Present day. Recovering from heartbreak after a disastrous marriage, Tilly decides to escape from the bustling capital and move to Dorset to stay with her dad, Ken. When Ken convinces Tilly to help with the restoration of the old railway, she discovers a diary hidden in the old ticket office. Tilly is soon swept up in Ted’s story, and the fateful accident that changed his life forever. But an encounter with an enigmatic stranger takes Tilly by surprise, and she can’t help but feel a connection with Ted’s story in the past… Don’t miss this haunting and evocative timeslip novel. Readers LOVE The Stationmaster’s Daughter: ‘A MUST READ in my book!!’ NetGalley reviewer, 5 stars ‘Utterly perfect… A timeslip tale that leaves you wanting more… I loved it. ’ Goodreads reviewer, 5 stars ‘I may have shed a tear or two!… A definite emotional rollercoaster of a read that will make you both cry and smile. ’ Debbie’s Book Reviews, 5 stars ‘Oh my goodness… The pages turned increasingly quickly as my desperation to find out what happened steadily grew and grew. ’ Ginger Book Geek, 5 stars ‘Very special… I loved every minute of it. ’ Jessica Belmont, 5 stars ‘Brilliant… Very highly recommended!!’ Donnasbookblog, 5 stars ‘Touched my heart! A real page turner… The perfect read for cosying up. I can’t recommend this gorgeous book enough. ’ Dash Fan Book reviews, 5 stars

About the Author (#ubf53bdc3-0d32-59c7-9ce4-632cec436ddc)

KATHLEEN MCGURL lives near the sea in Bournemouth, UK, with her husband. She has two sons who are now grown-up and have left home. She began her writing career creating short stories, and sold dozens to women’s magazines in the UK and Australia. Then she got side-tracked onto family history research – which led eventually to writing novels with genealogy themes. She has always been fascinated by the past, and the ways in which the past can influence the present, and enjoys exploring these links in her novels.

After a thirty-one-year career in the IT industry she is now a full-time author, and very much enjoying the change of lifestyle.

When not writing she likes to go out running. She also adores mountains and is never happier than when striding across the Lake District fells, following a route from a Wainwright guidebook.

You can find out more at her website: http://kathleenmcgurl.com/ (http://kathleenmcgurl.com/), or follow her on Twitter: @KathMcGurl (http://www.twitter.com/KathMcGurl).

Readers Love Kathleen McGurl (#ubf53bdc3-0d32-59c7-9ce4-632cec436ddc)

‘I adore McGurl’s time-slip novels’

‘Beautifully written, a real page turner, obviously well researched I found it a fabulous read’

‘A real eye-opener, her best yet, & I have read all Kath McGurl’s books. Loved it!’

‘A clever page turner of a book that will whisk you away’

‘Easily the best book I’ve read so far this year’

‘Absolutely compelling, and a wonderful read’

‘An absorbing, dual-timeline story that packs an emotional punch’

Also by Kathleen McGurl (#ubf53bdc3-0d32-59c7-9ce4-632cec436ddc)

The Emerald Comb

The Pearl Locket

The Daughters of Red Hill Hall

The Girl from Ballymor

The Drowned Village

The Forgotten Secret

The Stationmaster’s Daughter

KATHLEEN MCGURL

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Kathleen McGurl 2019

Kathleen McGurl asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008331115

E-book Edition © 2019 ISBN: 9780008243906

Version: 2019-07-01

Table of Contents

Cover (#ud76da31f-e123-5ad5-a2dc-851367182f12)

About the Author

Readers Love Kathleen McGurl

Also by Kathleen McGurl

Title Page (#u267299d7-3185-5fef-9866-8de6597ae53b)

Copyright (#u05851160-179b-51d7-9a02-8456a7f71a92)

Dedication (#u811f206e-148c-58e8-832e-71203465a8f7)

Prologue

Chapter 1: Tilly – present day

Chapter 2: Ted – 1935

Chapter 3: Tilly

Chapter 4: Ted

Chapter 5: Tilly

Chapter 6: Ted

Chapter 7: Tilly

Chapter 8: Ted

Chapter 9: Tilly

Chapter 10: Ted

Chapter 11: Tilly

Chapter 12: Ted

Chapter 13: Tilly

Chapter 14: Ted

Chapter 15: Tilly

Chapter 16: Ted

Chapter 17: Tilly

Chapter 18: Ted

Chapter 19: Tilly

Chapter 20: Ted

Chapter 21: Tilly

Chapter 22: Ted

Chapter 23: Tilly

Chapter 24: Ted

Chapter 25: Tilly

Chapter 26: Ted

Chapter 27: Tilly

Chapter 28: Annie

Chapter 29: Tilly

Chapter 30: Annie

Chapter 31: Tilly

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

For my brother Nigel

who provided much of the inspiration for this novel

Prologue (#ulink_fefd522b-ad9f-5c60-b6f6-1f26dd519fce)

For a moment he was frozen, unable to move, unable to react to what had just happened. Time stood still, and he stood with it, not seeing, not hearing, doing nothing.

And then as his senses returned he registered screams of horror, followed by the sight of that broken and twisted body lying at the foot of the stairs. How had it happened? Annie was screaming, lung-bursting screams of pain and terror. His instinct was to rush to her, gather her up and hold her, but would that make things worse? There was no going back now. No returning to how things used to be, before … before today, before all the horrible, life-changing events of the day. It was all over now.

The screams continued, and he knew that the next minutes would alter his life forever. He knew too that even without the broken body, the screams, the fall, his life had already changed irrevocably. The door to a future he had only dared dream of had been slammed shut in his face.

He allowed himself a moment’s grief for what had been and for what might have yet been, and then he shook himself into action, hurrying down the stairs to deal with it all. Not to put it right – that wasn’t possible – but to do his best. For Annie.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_83e33de2-890d-5935-8294-c67763fb6dec)

Tilly – present day (#ulink_83e33de2-890d-5935-8294-c67763fb6dec)

It was her dad’s voice that Tilly Thomson could hear, outside the room she’d been sleeping in. Her dad. What was he doing here? She rolled over and buried her face in her Disney Princess pillow. She didn’t want to see him. No, that wasn’t true, she did want to see him – she wanted nothing more than to be scooped up in his strong arms, and for him to take all the pain away. But she didn’t want him to see her like this. Broken, sick, deep in a pit of despair. No parent should see their child in this sort of state. Even if that child was 39.

There was a tap at the door, and then Jo entered. Jo was Tilly’s best friend, the person who’d saved her life and given her a place to stay. She’d moved her two little daughters into one room to make space for Tilly, after she was discharged from hospital.

‘Tils? Your dad’s here.’ Jo stepped into the room, her face taut with worry. ‘I know you said you didn’t want to worry him, but listen, mate, he’s your dad. So I phoned him. Don’t be cross at me. Let him help.’

Before Tilly could summon the energy to answer, Jo stepped aside and Tilly’s dad, Ken, entered the room. He looked stressed, much older than when she’d last seen him. That would be her fault, she supposed.

‘Hey, Dad,’ she managed to croak.

‘Oh, pet. What’s up? Jo said you were in a bad way?’ He looked about for a place to sit down, and pulled out a small stool upholstered in pink to perch on.

‘I’ll, um, leave you two to talk,’ Jo said. ‘Did you want a cup of tea, Ken?’

‘Thanks, Jo. I’d love one.’

Jo closed the door quietly behind her. Tilly took a deep, shuddering breath, and closed her eyes. The pain on her father’s face was too much to bear.

‘What’s up?’ he said again, his voice hoarse. He was fighting back tears, she realised.

‘Just … all got a bit much for me, I suppose,’ she whispered. She couldn’t tell him the whole truth. Not now. Not yet.

‘You should have talked to me! I’d do anything for you, you know that, pet? Jo said you were … having a breakdown of some sort. God, when I heard …’

Tilly didn’t want to think about how he’d have felt. A pang of guilt coursed through her, adding to the pain, pushing her deeper into that dark pit of misery. ‘Sorry, Dad. I … didn’t want you to be worried.’

‘Of course I worry. Just want my girl to be happy again.’

She forced a weak smile to her face and reached for his hand. Her lovely dad, just trying to do what was best for her. But he wouldn’t be able to fix everything. ‘I know you do. Thanks.’

‘Look, pet, we have a bit of a plan. I think you should come home with me. Down to Dorset. I’ll sort out the spare room for you, and then you can rest and relax as much as you need. Jo’s been so good, but you can’t stay here forever. She’s got her own family to look after.’

Tilly tried to imagine life with her dad in his bungalow by the sea. He’d lived on his own since her mum died nearly three years ago. He spent all his spare time helping with the restoration of an old railway. He’d probably try to get her involved in it too, but right now, she couldn’t imagine doing anything other than lying in bed, under a thick duvet to insulate her from the rest of the world.

‘It’ll be good for you, pet. Sea air. The views from the cliff top. Getting away from London and all … everything that’s happened.’

‘He’s right, Tils.’ Jo had come back in with a couple of mugs of tea. She handed one to Ken, put the other on a bedside cabinet then perched on the end of the bed and took Tilly’s hand. ‘Listen, mate, you know you can stay here as long as you want. I’m not chucking you out. But have a think about it. New surroundings, living by the coast in Coombe Regis, a slower pace of life a long way from Ian and the rest of it. Might help get your head straight.’

‘I’m not sure it’ll ever feel straight again,’ Tilly said, but regretted it when she saw Ken wince. He didn’t know all of it. Unless Jo had told him.

‘It will, in time. Believe me.’ Ken put his tea down on a plastic toy crate and slid to his knees beside the bed. ‘Come here, pet. Let your old dad give you a cuddle. Can’t promise to make it all better in one go, but the Lord knows I’ll give it my best shot.’

And then he scooped her up into a sitting position, wrapped his arms around her and held her tight. Tilly held on to him, letting his strength seep into her, resting her head against his shoulder and finally giving in to the urge to cry – huge, ugly sobs that shook her body and wracked her soul, but which somehow he seemed to absorb, so that when she finally calmed herself and pushed him gently away, she felt just a tiny bit better, just a touch more able to face the world. Perhaps he and Jo were right. Perhaps a stay on the Dorset coast with Ken would help. It certainly couldn’t make her feel any worse.

*

Ken slept on Jo’s sofa for the next two nights, until Tilly felt ready to face the journey. She felt scared to leave the cocoon of Jo’s house, that comforting little pink bedroom in which she felt like a child being cosseted as she recovered from a bout of chicken pox. But 5-year-old Amber deserved to have her bedroom back.

At last it was time to leave. After dropping her kids off at school and nursery, Jo had made a trip to the house Tilly had once shared with Ian, and filled a suitcase with clothes. ‘I picked up mostly jeans, T-shirts, fleeces,’ she said. ‘I guessed you wouldn’t want your smart work clothes. If you need anything more I’ll go and fetch it, and bring it when I come to visit.’ She hugged Tilly. ‘Which won’t be too many weeks away, I promise.’

Tilly’s eyes filled with tears. Jo had been such a good friend to her through all this. There was no way Tilly could have faced returning to her old marital home to pack, even when Ian wasn’t there. And although Ken had offered, Jo had insisted he stay with Tilly rather than risk a confrontation with his son-in-law, which would almost certainly end badly. ‘Thanks, Jo. I can always buy anything else if I feel I need it.’ Though right now all she felt she’d need was a few pairs of warm pyjamas and maybe a dressing gown.

With effort, she dragged herself into the shower, washed her hair, and dressed in some of the clothes Jo had fetched. When she came downstairs, she found her father and Jo sitting in the kitchen, talking seriously. About her, no doubt. They cared, she reminded herself, even if she no longer cared about herself.

‘There you are. You look better for having that shower,’ Jo said, with a smile. ‘Cup of tea before you go?’

Tilly shrugged. Recently she’d found it impossible to make even the simplest decision. Ken put out a hand to her and squeezed her arm. ‘Thanks, Jo, but I think we’ll get going. It’s a longish drive, and I want to get home before the evening rush hour. Ready, pet?’

She nodded, numbly, and allowed him to shepherd her out to the car. Jo gave her a hug. ‘Look after yourself, Tils. Listen to your dad. Do whatever he suggests, promise me. I’ll be down to see you in a couple of weeks, I promise. Love you, mate.’

‘Thanks, Jo,’ Tilly managed to say. The words seemed inadequate, but the effort required to find more was too much. She climbed into the car, put on her seat belt and leaned back against the headrest. Outside, Ken was hugging and thanking Jo, and loading his bag and Tilly’s suitcase into the boot. And then he was in the driver’s seat beside her, starting the engine, and they were on their way, leaving Jo standing on her driveway, dabbing at her eyes with a tissue. Even Ken’s eyes looked suspiciously moist. Far too much crying was going on, Tilly thought, and all of it her fault. But right now, she didn’t feel she could do anything about it.

*

The journey passed uneventfully. Ken found a classical music station on the radio, and Tilly let the music wash over her as she stared out of the window at the passing countryside. It was February, the fields were brown and bare and the sky was a dismal grey. The scenery and weather were a perfect match for her frame of mind. Soon it would be spring, there’d be new growth in the fields and hedgerows, birds would sing and lambs would be born, and everyone would look forward to the warmth of summer. Would she? Was there anything to look forward to? She’d lost her job, her husband, her chances of having a family. But now she was here, with her dad, and somehow she had to find a way forward.

She knew she shouldn’t dwell on these thoughts. All it did was make her more miserable. She fumbled in her jeans pocket for a crumpled tissue, but it wasn’t enough to soak up her never-ending tears. Ken glanced over, then rummaged in his pockets and pulled out a cotton handkerchief. ‘Here, pet. It’s clean, and it’ll be easier on your skin than those tissues.’

She took it gratefully. The cotton was soft from having been washed hundreds of times. It had been folded in four and ironed, just the way her mum always used to iron handkerchiefs. An image of her dad standing over the ironing board, carefully ironing and folding hankies flitted through her mind, and despite her misery she found herself smiling faintly.

‘That’s better, pet. Breaking my heart to see you so upset. When we get home I’ll make up the spare bed for you. Then I’ll make us shepherd’s pie for tea. You always loved your mum’s shepherd’s pie. I’ve learned to cook since she … went.’ He bit his lip. ‘I’ve had to.’

Tilly reached out to pat his shoulder. Dad had never cooked so much as beans on toast the whole time she was growing up. Mum had done everything. When she died, Tilly had wondered how he’d cope on his own, but she’d been so caught up in her own problems at that time that she’d never asked. To her shame, she realised this was her first visit to Dorset since the funeral. And this wasn’t so much a visit – more like a rescue.

‘Thanks, Dad. Looking forward to it.’ Looking forward. Well, it was a start.

The roads became narrower and more twisty as they drove deep into Dorset. Not far from Coombe Regis Ken slowed down as they passed through a village. ‘That’s Lynford station house,’ he said. ‘The first station the restoration society bought. We’ve laid some track here and we’re open at weekends and school holidays, running trains up and down.’ Tilly glanced across at the building he was indicating, and saw a sign: Lynford station: Home of the Michelhampton and Coombe Regis Railway.

‘Is that where you spend your time?’ she asked.

He nodded. ‘Well, there and Lower Berecombe, which is the next station on the line. Actually, I’m usually at Lower Berecombe. We’ve not owned it as long, and there’s more to do there. Anyway, I’ll give you a tour of both as soon as you feel up to it.’

She forced herself to smile at him, then stared out of the window in silence for the remainder of the journey. Thankfully they were soon in the outskirts of Coombe Regis. She’d been here before – her parents had bought their cliff-top bungalow after they retired, and she and Ian had visited a few times.

Ken drove down a steep street that she remembered, that led straight down to the tiny harbour in the heart of the little town. There, they turned right, past some shops and a small beach, and then through a residential area, heading uphill once more to the cliffs on the west side of town. This part was familiar from her previous visits, and soon they turned into her dad’s driveway and she saw the stunning view across the cliff top to the sea. Even with the low grey cloud and sporadic rain, it was beautiful.

‘Here at last, then, Tillikins!’ Ken jumped out and began unloading the luggage from the boot.

‘Great,’ she replied, turning away. His use of her old childhood nickname had made her eyes prickle with tears.

She got out of the car and followed Ken inside. It was exactly as she remembered it – exactly as it had been when her mother was alive. A small table stood by the front door, with an overgrown spider plant on it, its offspring dangling down to floor level. Her mother’s deep-red winter coat still hung from a hook in the hallway, and as she passed, Tilly reached out to caress it.

‘I should send that down to the charity shop, I suppose,’ said Ken, noticing her action.

‘Not if you’re not ready to,’ she replied, and the way her dad turned quickly away told her he wasn’t.

‘Go on into the sitting room,’ he said. ‘Give me ten minutes to sort out a bedroom for you.’

She did as he said and sat on a sofa that was angled to make the most of the view of the cliff top and sea. There was something calming about resting your eyes on a distant horizon, she thought. It would help, being here.

A few minutes later Ken came back. ‘So, you’re in this room,’ he said, leading her along the corridor and into the guest bedroom, the same one she’d stayed in before with Ian, but her father had decorated it since she’d last been here. It had a double bed with crisp white bed linen, pale-blue painted walls that on a good day would match the sky outside, a dark oak chest of drawers and a chair upholstered in vibrant blues and greens. The floor was a pale laminate, with a fluffy cream rug beside the bed. The whole effect was restful and calming. Ken had put her suitcase on a low table and laid a blue-and-white striped towel on the end of the bed.

Tilly felt tears come to her eyes again. ‘Thanks, Dad. This is really nice.’

‘I tried to think of what your mother would have done, and did the same,’ he said.

‘She’d be proud of you.’

‘Thanks, pet.’ A gruffness in Ken’s voice betrayed his usual discomfort with emotional scenes, so Tilly said no more, but set to work pulling clothes she had out of the suitcase, putting her wash bag on the chest of drawers and tucking her pyjamas under the pillow.

‘Right then, a cup of tea, and then dinner in about an hour?’

‘Got anything stronger? I feel the need … well, it’s been a long day.’

Ken nodded. ‘There’s some wine, but are you sure, after—’

‘I’m fine. I won’t overdo it.’

A few minutes later, with a glass of buttery Chardonnay in her hand, Tilly was standing by the picture window in the bungalow’s sitting room, gazing at the view. The rain was beginning to clear, and dusk was falling. To the west, over the sea, there was a strip of clear sky, turning ever deeper red and purple as the last of the light faded. There was a path along the cliff behind her father’s garden.

‘Did Jo pack your walking boots or a pair of trainers? It’d be good for you, to get out there and walk along the cliffs. Helps put things in perspective. Well, it helped me, after … you know.’ Ken had come to stand beside her, watching the sunset.

‘Yes, maybe I will. Some day.’ Tilly topped up her wine. Right now, the only thing she wanted was to drink enough to blot out the world and then crawl under a duvet.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_6a352d02-6c8f-55a8-83e4-817f9ca39cfd)

Ted – 1935 (#ulink_6a352d02-6c8f-55a8-83e4-817f9ca39cfd)

Ted Morgan, the stationmaster at Lynford station, had reached the not-insignificant age of 40 years without believing in love at first sight. Indeed, he wasn’t sure he believed in love at all; that is to say, not the romantic variety. You loved your parents, your siblings, and children (if you had any), of course. And you could be infatuated by a member of the opposite sex. But romantic love was a notion he’d had no experience of, and therefore was disinclined to believe in.

Until, that is, he’d first laid eyes on Annie Galbraith, and love – he could not call it anything else – hit him between the eyes with all the force of a Manning Wardle 2-6-2 tank engine.

Annie was slim, shorter than him by a foot, blonde of hair and blue of eye, her face shaped like a perfect heart. She held her head high as if to make herself taller, giving the impression of someone who was superior, as she was to him, in every way. She arrived each morning on the 08.42 from Michelhampton, strode purposefully through Ted’s little branch-line station with a neat black handbag hooked over her arm. In the evenings she returned three minutes before the 17.21 was due to depart. She sat in first class – where else for such a goddess? – in a seat on the left-hand side, one which afforded the best views across the Dorset countryside, on the forty-minute journey to Michelhampton. She had been travelling on these trains every weekday for the past four months, and in all that time he had only ever said three words to her. The same three words, over and over. In his head they were, ‘I love you’, but they came out of his mouth as ‘Thank you, ma’am,’ when he inspected her ticket each day. The weekly ticket that, he knew, she bought from the ticket office at Michelhampton, from the lucky, lucky clerk there, who had the pleasure of the longer and more involved interaction associated with purchasing a ticket.

Still, gazing at the ticket, holding it when it was still warm from her own fair hands (that were sometimes encased in soft leather gloves, though not now that the season had progressed towards spring), was a thrill in itself. And then, when he’d completed his check, he could raise his eyes to hers, smile, and say those three words, and she’d nod and take the ticket from him, then turn and hurry onto the platform where the train was waiting. Once, she almost smiled back at him. Twice, she’d said thank you. And on another occasion, when she was a minute or so late, he’d held the train and ushered her onto it as she scurried through the station, her heels clip-clopping on the station’s tiled floor. He’d waved her away as she reached for her ticket, and she’d smiled for sure that time before wiping the back of her hand across her brow as she boarded the train as if to say phew! Thank goodness she’d made it, and all thanks to Ted!

He’d discovered her name a month or so after she’d begun commuting regularly. He knew the names of most regulars; certainly those who lived in Lynford or Berecombe, and many of those who lived in Coombe Regis. Michelhampton was larger, further off, and not a place he’d regularly visited himself, so he wasn’t as well acquainted with passengers who came from there. In the summer season, most of his passengers were holidaymakers and day-trippers, changing onto the branch line from the main line at Michelhampton.

He wasn’t proud of the way he discovered her name. It was a quiet Monday morning, and she was the only passenger alighting from the 8.42. He’d watched her from the door of the station as she walked up the lane towards the village. Then, on a whim, his next duties not being for thirty minutes when a goods train was due, he locked up the station and followed her, at a respectable distance, telling himself he needed to buy some bread and a chop for his dinner, and now was a good time to visit the village shops. She was a little way ahead of him, and he turned a corner only just in time to see the hem of her dress disappearing into the National Provincial Bank. Did she work there? Ted had to know. He removed his stationmaster’s peaked cap and followed her inside. Perhaps he could pretend he had some banking business to do, ask about opening a savings account or the like. He usually did his own banking at the Midland Bank, a little further up the High Street.

‘Hey, Annie! How was your weekend?’ Ted heard a girl cashier call out, as the object of his attention disappeared through a door marked Private. A supervisor came up behind the girl. ‘Now then, Muriel, attend to this gentleman. You can catch up on Miss Galbraith’s gossip during your lunch break.’

Ted suppressed a smile. So his angel’s name was Annie Galbraith. He stepped up to the counter and spoke to the cashier for a few moments about the interest rates available on savings accounts. He was furnished with a leaflet, and left, promising to think about it and return at a later date. He had no further glimpses of Annie, but it was enough. He knew her name. This evening when he checked her ticket, he could say to her, ‘Good evening, Miss Galbraith.’ If he could pluck up the courage to do so, that is.

Eventually, he did, but not until about a week later, when an unseasonably warm day had filled him with vigour, emboldening him just a little. He’d felt himself blush to the roots of his hair as he’d greeted her from the morning train, with a cheery, ‘Good morning, Miss Galbraith.’ She’d stared at him for a second, then recovered her manners and nodded an acknowledgement with a smile, before hurrying through the station as usual.

That smile. He treasured it. Every tiny, brief second it had been upon him.

*

Ted had been stationmaster at Lynford for fifteen years. He’d worked on the railway for eleven years before that – starting as a porter up the line at Rayne’s Cross when he left school aged 14, before being promoted to stationmaster aged 25, the youngest and proudest stationmaster in the whole of Southern Railway at that time. Then, he’d moved to Lynford, where a single building functioned as both station and stationmaster’s house. There was a ticket office where his Stationmaster Certificate hung proudly behind the counter, a ladies’ waiting room, ladies’ and gents’ water closets, a small sitting room, kitchen and scullery downstairs. Off the sitting room a narrow staircase rose, twisting back on itself to reach a tiny landing, which led to two small bedrooms. Ted slept in a single bed in the larger of the two, and used the other one for storage, though he cleared it out whenever his sister and her children came to visit. It was a small home, but adequate for his needs.

Behind the station was a goods yard – a siding ran off the main line and stopped inside a large shed. Here, the daily goods trains were shunted and the goods unloaded from wagons directly into trucks, to be delivered locally. Coal came once a week, and the other days brought various different commodities – groceries, goods for the various Lynford shops, occasional livestock bought at markets by local farmers. A larger station would have employed a dedicated goods yard manager, but here, it was Ted’s job to organise the goods yard, marshalling the trucks and carts as they turned up to deliver or collect goods, operating the hoist that was used to lift crates off wagons and onto trucks. He was aided in these activities by Fred Wilson, a skinny, sallow, surly lad of 18, who was officially employed as a porter, but in reality took on any job that needed doing, albeit usually with poor grace. ‘I’m supposed to be a porter,’ he’d grumble, when Ted called on him to help unload a goods wagon. ‘If I gets me uniform mussed up on the wagons, Ma will have me guts for garters. And that’ll be all down to you, Mr Morgan.’

‘Take your jacket off then, lad,’ Ted would reply, every time he heard this grumble. ‘And put on a set of overalls.’

‘They’re as mucky inside as the wagons are on the outside.’ And Ted would roll his eyes at the boy and get started himself on the task at hand. Fred would soon join in, still muttering but eventually getting the job done.

Every day the post came by rail, too, and Ted brought them into the ticket office, where the Lynford postman collected them for onward delivery. A bundle of morning newspapers arrived on the 07.42, and was left in the ticket office until the newsagent’s paperboy collected them on his bicycle with its enormous wicker basket balanced on the back.

There was always something that needed doing, from early morning till mid-evening, in and around the station and goods yard, and of course all of it had to fit around the arrival and departures of the dozen trains a day between Michelhampton and Coombe Regis. Some services were quiet, almost empty, in the winter months, but summer brought an influx of holidaymakers and day-trippers. Most went through to Coombe Regis, but some would stop off at Lynford for a few hours, or maybe overnight, and visit the village’s fourteenth-century church and ancient witch’s dunking stool that overhung a stream, or spend a day walking over the hills between Lynford and Coombe Regis, which rewarded the more energetic visitors with the best views of anywhere, in all of southern England. At least, Ted thought so. He’d lived all his life in this area and could not imagine a more beautiful place. Why would anyone want to leave? He had no interest in going anywhere. Michelhampton was the furthest he’d been, other than a couple of railway training sessions held in Dorchester. That was a big enough city for his taste. Why anyone would want to go somewhere like London he couldn’t understand.

No, Ted was content with his life here in Lynford. Contented and happy for it to continue as it always had – up until the moment he’d fallen in love with Annie Galbraith. Suddenly, making sure the trains ran on time and the railway functioned smoothly seemed no longer enough, and he found himself fantasising about another life, one with Annie by his side, a clutch of children at their feet, a home away from the railway with roses around the door …

Chapter 3 (#ulink_519cbb35-3417-50b1-b702-2c81ff369f8a)

Tilly (#ulink_519cbb35-3417-50b1-b702-2c81ff369f8a)

Tilly awoke, wondering for a moment where she was. A bright, blue room, with white bed linen. Not her bed with Ian, not Amber’s pink princess bedroom. Not the hospital bed she’d spent a few days in either.

It came back to her slowly. Her father’s bungalow. Of course. He’d driven her down to Dorset, made her shepherd’s pie, and she’d then polished off a bottle of wine. Or was it two? She’d cried a lot, as well. And her dad had loaned her his soft, neatly ironed handkerchiefs and let her cry as much as she needed to.

Her eyes felt sore and her mouth was parched. She needed cold water on her face, a thick coating of moisturiser and about a gallon of tea. As if he had heard her silent cry for help, at that moment Ken tapped on the bedroom door and entered, carrying a large mug.

‘Thought you might be in need of this, pet,’ he said, placing it on a coaster on the bedside table.

‘Cheers, Dad. Did I embarrass myself last night?’

‘Not at all. You cried a lot. I hate to see you like that. But I know what I was like, after your mother …’

He turned away, uncomfortable with the intimate talk. ‘Want me to open your curtains? Or are you going to go back to sleep? You can do whatever you want, you know. No need to get up for ages. I thought – when you do get up – we could go to Lower Berecombe. To the station. I’ll show you what I’ve been spending all my time doing.’ He shuffled towards the door.

‘I’ll be up soon,’ Tilly called after him, as he gently closed the door. Her instinct was just to drink the tea then crawl back under the covers and stay there for the day. But she knew that wouldn’t help.

‘Promise me,’ Jo had said, as she waved Tilly off the day before, ‘that’ll you let your dad help you. Don’t shut him out. Do whatever he suggests, go out with him, look at all his railway stuff. I think it’ll help. You said it helped him, after your mum died. Gave him something to do, something to be interested in.’

She’d nodded at Jo, promising she would, and that meant she’d have to make the effort today to get up and dressed and go out with her dad.

*

It was late morning before Tilly was finally up, showered, dressed, with a fried egg on toast and several cups of coffee inside her, at last feeling ready to face the day. She’d spent a few minutes looking round Ken’s house, seeing everywhere the evidence that he’d not been able to move on at all since her mother’s death. As well as that coat by the front door, her phone still lay on a bedside table, constantly charging although it would never be used again. The smallest of the four bedrooms was still kitted out as her mum’s crafting room – the sewing machine set up and threaded ready for use, scraps of cloth for a patchwork quilt strewn over the bed, a pile of craft magazines with Post-it notes marking interesting pages on the floor.

If he hadn’t managed to move on yet, what hope was there for her?

‘Ready, pet?’ Ken said, from where he was standing by the front door, cap in hand, ready to take her out to his beloved station.

‘Yeah, sure,’ she replied, trying for his sake to summon at least the appearance of enthusiasm.

*

It was just a tumbledown cottage, was Tilly’s first thought, as Ken parked outside Lower Berecombe station house. She climbed out of the car and stood for a moment, looking around. Not much to show for the restoration work, she thought. You could just about see that there’d once been a railway through here – behind the station house was the remains of the trackbed, and a straight, flat footpath led off in one direction, signposted ‘The Old Station Inn – 5 miles’. A couple of sheds stood to the side of the main building. One, looking just big enough for a man to stand up in, looked as though it had once housed signalling equipment.

‘So, this is it,’ Ken said, sounding excited to be showing her around his pride and joy at last. ‘Obviously Lynford’s in better shape but this place is coming along nicely too. Come on in.’

Tilly followed him into the building. Inside the old station was a mess. There was no other way to describe it. Debris everywhere, broken stepladders, ancient pots of paint, mouldering boxes containing who knew what. Ken led her through to a small room that had a hideous orange floral carpet and an old brown velour sofa on which a tabby cat lay curled up, sleeping.

‘Sit down. I’ll put a pot of water on to boil. We can have a cuppa.’ On a rickety-looking table in the corner was a Primus stove, a five-litre container of water, a box of teabags and a couple of chipped mugs. He set to work while Tilly sat down. The cat sniffed at her and then stood, stretched and calmly walked across and onto her lap, where it settled down once again, purring happily. She stroked it, discovering a feeling of calm as she rhythmically smoothed its fur.

‘Ah, you’ve made friends with our resident moggy,’ Ken said, looking over his shoulder at her. ‘We’ve no idea where she came from. She just hangs out here, and any railway volunteer that’s here feeds her.’

He handed her a mug of tea and sat beside her on the old sofa, chattering away about the railway restoration while Tilly drank her tea, stroked the cat and tried to keep herself composed. Ken seemed totally at home there. He’d been an area manager for a railway company before he retired. ‘Glorified stationmaster, essentially,’ he’d always said, with a laugh. Railways must be in his blood, Tilly had realised, for as soon as he’d retired and moved to Dorset he’d involved himself in this railway restoration project.

‘So, bring your tea with you, and I’ll give you a quick tour,’ he said, clearly longing to show off what he’d been up to.

She pushed the cat off her lap and stood up. ‘Is this where you spend all your time, then?’

‘Mostly, yes. This was one of the stations on the line. The Society – the Michelhampton and Coombe Regis Railway Society, that is – bought it a few months ago. It had stood empty for years, after being used as a holiday home back in the Sixties and Seventies. As you can see there’s an awful lot of work to do here. Come on, I’ll show you.’

She followed him out through a set of double doors that led into what had once been a garden. He stopped a couple of feet away from the door. ‘You’re now standing on what was once the “down” platform. It was only ever a low platform – about a foot above the height of the trackbed. See the step down?’ He walked forward and down a muddy step, and Tilly followed. ‘Now we’re on the trackbed. Look that way’ – he gestured to his left – ‘and you can see the footpath that runs along the trackbed from here to Rayne’s Cross and the reservoir. It goes over the old viaduct which has amazing views, so it’s quite a popular walk. And Rayne’s Cross station is now a pub, the Old Station Inn. Lynford is in that direction.’ He pointed to the right where a fence ran across the trackbed and there was no footpath.

Tilly turned and looked back at the station house. There were missing roof tiles, the brickwork looked in need of re-pointing, the paintwork was horribly peeling, and the remains of the platforms and trackbed were muddy and overgrown. It looked the way she felt, she thought, feeling a weird kind of empathy with the building.

‘Why don’t the trains run all the way from Lynford to here?’ she asked.

Ken pulled a face. ‘We’d love to do that, but we’ve had to buy back the trackbed from local farmers, bit by bit. Unfortunately, we’ve been having trouble buying that last piece of the trackbed. Owner won’t sell up.’ He pointed once again to the fence.

‘Why not?’

Ken shrugged. ‘Who knows? She’s got some sort of long-standing grudge against us but no one really knows what it is. Anyway. Come on, come and see my workshed.’ He walked along the old trackbed to just past the station house. Tucked in behind was a large metal shed – it looked like a shipping container. The doors at one end stood open, and inside was what Tilly instantly recognised as paradise for her father. There was a workbench strewn with tools along one side, a couple of rusty railway signals lay on the floor on the other side, and the far end held a large container filled with more rusty metal pieces. Ken picked one up and turned it over, lovingly.

‘This is a track spike. These are used to hold the rail to the wooden sleepers. We’ve acquired thousands of them over the years, and they all need cleaning up before we can use them on a new section of track. And those signals there, those are my next job. Clean them up, get them in working order, repaint them. If we ever manage to buy that bit of land, we’ll be wanting to extend the line to here as soon as possible, and then beyond to Rayne’s Cross. The owner of the pub there can’t wait for us to link up.’

Tilly was only half listening. Her mind was in no state to take in the details of railway restoration. She was gazing instead at the countryside, the gentle rolling hills, copses and hedgerows. ‘Dad? Mind if I go for a walk?’

‘Er, sure. Shall I come with you?’

She shook her head. ‘No thanks. I kind of want to be by myself for a bit.’

‘OK.’ He looked around at the rusty equipment and greasy tools. ‘I suppose this kind of thing isn’t really your cup of tea. Go on then. You could walk the old trackbed towards Rayne’s Cross, then there’s a footpath off to the left through some fields and along a lane that loops back round to here. Takes about an hour. You’ll be all right on your own?’

She heard the unspoken words – you won’t do anything silly, will you? – and nodded. ‘I’ll be fine. See you back here in a bit, then.’

She headed off along the old railway track, half-heartedly trying to imagine what it might have looked like eighty years ago when steam trains ran a regular service on the line. The path was straight and level, its surface a mixture of grass and gravel. It was flanked by overgrown bushes, some overhanging the trackbed. If ever her father and his restoration society managed to extend the track in this direction, they’d have a job to do to keep the foliage under control.

After a while she came across a gap in the hedge on the left, and a stile set into a short piece of fence. Deciding this must be the place her dad had suggested she leave the trackbed, she climbed over, and headed off across the fields, clad in their winter brown and dull green. Here and there a few sheep grazed on the short grass; in the next field two horses in heavy winter rugs stood dejectedly nose to tail under a tree. Tilly’s mind wandered as she walked. She found herself reliving the events that had brought her here to Dorset. It wasn’t healthy to do this, she knew – she should look forward rather than back. But her future was too uncertain to dwell on. It was too depressing to think of it. And so she found herself thinking about Ian, the way he’d left her, her redundancy, and her miscarriages. The way it had all come to a head one day and she’d felt there was no way forward. Her dad didn’t know about all of it, yet. One day maybe she’d tell him the details, perhaps when she felt strong enough to talk about it.

She crossed a couple of fields, following a lightly trodden path. Ken had said it came out on a lane and looped round back to the station. She stopped and looked around, and realised she had no idea where she was, or what direction the station lay. Where was this lane? The weather was deteriorating – grey skies were becoming darker and the threat of rain hung heavy in the air. She’d been walking for over an hour. She pulled out her phone to call Ken for directions but there was no signal.

A little further on there was a farmhouse. That must have an entrance onto a road, she thought. Maybe from there she’d be able to figure out the way back. She headed towards it and realised she was approaching it from the back, through the farmyard. There were a couple of near-derelict barns and a rusty old tractor sat forlornly to one side, its tyres flat and weeds growing up around it. Not a working farm anymore, then. She headed round to the front of the house, to the gravel track that led to a lane, but then she wasn’t sure which direction to walk once she hit the lane.

The farmhouse looked scruffy and uncared for, its front door painted with peeling dark-red paint, but there was a light on inside so it was clear someone lived there. Tilly sighed with relief and knocked on the door to ask for directions.

The door was opened by a stooped woman who looked to be in her eighties. She was wearing an old-fashioned pink nylon housecoat, of a type Tilly had last seen on her own grandmother thirty years before.

‘Er, hello, I am sorry to bother you, but could you tell me the way back to Lower Berecombe?’ Tilly asked. ‘I seem to be a bit l-lost.’ To her horror she found her eyes welling up with tears as she spoke.

‘Of course, dear, it’s not far, but – you look upset? Won’t you come in for a moment until you feel better? A cup of tea, that’s what you need. And I have a pack of chocolate biscuits somewhere.’

‘Oh, but I m-mustn’t disturb you,’ Tilly said, fumbling in her pocket for a tissue.

‘Nonsense. Disturb me from what, daytime television?’ The old woman scoffed and rolled her eyes. ‘Come on in, dear. I’m not turning away a crying stranger.’ She stood back with the door wide open, and Tilly followed her inside. Perhaps a cup of tea was what she needed. Some time away from her thoughts, with someone who knew nothing about her or her troubles.

The old woman had gone into the kitchen – a clean but tatty room that looked as though it had last been refitted in the Seventies. She filled a kettle, switched it on and dropped a couple of teabags into an old brown teapot. ‘Sit down, do,’ she said, gesturing to the group of mismatched chairs arranged around a battered Formica-covered kitchen table. She took a box of tissues from a work surface and put them in front of Tilly.

Somehow this quiet gesture was too much. As if she hadn’t cried enough over recent weeks, Tilly found herself with tears coursing down her face once more. She pulled out a couple of tissues and tried to compose herself while her host finished making tea and laying biscuits on a plate.

A few moments later the old woman put a cup of tea in front of her and sat down. ‘I’m Ena Pullen,’ she said, pushing the biscuits nearer to Tilly.

‘Tilly Thomson,’ Tilly replied, taking a biscuit. ‘Thank you so much for inviting me in.’

‘You look like you are having a tough day,’ Ena said. ‘I’m not going to ask you what’s wrong, but I hope when you leave here you feel a little better than when you arrived. If you do, I’ll have done my job.’ She smiled, and it was all Tilly could do not to begin crying again. Tea and sympathy always set her off.

Ena chatted about inconsequential things – whether her favourite contestant would win the latest TV reality singing competition, the likelihood of the summer being warm or not, the different types of birds who visited her bird-feeder over the winter months. Tilly listened and nodded but said little in return, allowing the trivial topics to fill her mind, pushing everything else out.

When her tea was drunk, Tilly reluctantly got to her feet and shook Ena’s hand. ‘Thank you so much. I feel a lot better now, but I’d better get going. Dad will be wondering where I am. Could you just point me in the direction of the old station at Lower Berecombe?’

‘The station?’ Ena’s expression darkened. ‘Don’t say you are anything to do with that old railway?’

‘Well, no, but my dad is … he’s part of the society trying to restore it.’

‘Is he now …’ Ena pressed her lips together and led Tilly out of the kitchen. ‘Well, Tilly, as you said, it’s time for you to go. Turn left along the lane, keep walking for about ten minutes and you’ll reach the village, then go right by the church until you see the station.’ Her tone was noticeably colder.

‘Is everything OK?’ Tilly asked hesitantly as she stepped through the front door.

Ena’s previously friendly expression was harsh. ‘That railway was the death of my father, and that society’s trying to rebuild it. It’s all wrong. I want it stopped.’ With that she shook her head and closed the door behind Tilly.

*

Tilly found her way back to the station, where Ken had changed into grimy blue overalls and was busy removing rust from one of the old railway signals. He looked up as she approached.

‘I was about to send out a search party. Where did you get to?’ His tone was joking but she could sense his worry behind it. She told him about her meeting with Ena Pullen and he made a face.

‘Oh, her. She’s the one who won’t sell us that length of trackbed. The death of her father? Rubbish. She’s just a miserable old so-and-so who doesn’t like change.’

Tilly frowned. She didn’t agree with her dad’s opinion of the old woman. Ena had seemed kind and caring, right up until the moment when Tilly had mentioned the railway. She wondered idly what could possibly have happened to have elicited such a change.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_23670a34-26da-5ff2-880f-53e4eb52711c)

Ted (#ulink_23670a34-26da-5ff2-880f-53e4eb52711c)

It had become an annual event for the last few years: during the school’s October half-term break Ted’s sister Norah would arrive with her three children to stay for a few days. They lived in London and loved coming to the country. Norah’s husband couldn’t spare the time off work, so she’d bring the children by train, herself.

It meant Ted had to clear out the second bedroom so that Norah and her 5-year-old daughter Margot could sleep there, but he didn’t mind. It was always a delight to have company. The two boys, Peter aged 12, and Tom aged 10, would sleep downstairs in the parlour. It was a squash in the small house, especially when they all sat around Ted’s tiny table at mealtimes, but somehow it worked. Norah would take over cooking duties while she was there, and Ted relished the break from having to do it himself. Plus, she was a fabulous cook, and he always ate well when she was there – her pies, pastries, roasts and desserts were delicious.

Norah arrived on the 14.25 from Michelhampton, one sunny but chilly afternoon. As she alighted from the train amid a cloud of steam, Ted doffed his cap to her but otherwise stuck to his duties. It was most important to ensure the other passengers disembarked safely and that the train left on time, having taken on more water from the water tower. He knew that his sister understood that his duties came first, and indeed, he saw that she had herded the children together and sat them on a bench on the platform, with their luggage beside them, while they waited for him to be free.

At last the train was ready to leave; Ted checked all doors were closed, blew his whistle and waved his flag. He stood watching it until the last carriage was beyond the end of the platform, and then turned to Norah with a smile.

‘So good to see you! I trust the journey was pleasant?’

‘Ted!’ Norah placed her hands on his shoulders and kissed him on both cheeks. ‘Yes, it was. We were six minutes delayed reaching Michelhampton from London, but the Coombe Regis train was held for us.’

‘Bill must have made good time then, on the way here,’ Ted replied. ‘Come along then, scallywags. Let’s see if Uncle Ted has some biscuits hidden in the cupboard for you.’ He picked up Norah’s suitcase and holdall and led the way inside, followed by the three whooping children.

A few minutes later the children were sitting around the little kitchen table, each with a glass of orange squash and with a plate of biscuits in the middle. They were arguing at full volume about whether custard creams were nicer than Bourbons, or whether Garibaldi were the best biscuits of all. Ted was pleased he’d made the effort to buy a selection from the village shop. It wasn’t something he normally treated himself to, but having always assumed he’d have no children of his own, it was fun to spoil his nephews and niece. He took the cases upstairs and came down again to find Norah had put the kettle on for a cup of tea. He smiled to see her making herself at home. Really, she was the easiest guest in the world, even if she was accompanied by three boisterous children.

‘So, Ted, any news?’ Norah asked, as she took his brown pottery teapot down from its shelf and spooned tea into it.

It crossed his mind to tell her about Annie, about how he felt every time he saw her, about his crazy dreams that one day Annie would feel the same way about him. Ted had always confided in his big sister. But somehow, this felt too private. Norah would get the wrong idea, and would assume he was walking out with Annie, when he’d never even had a conversation with her. ‘Nothing new, no. We had a good summer season, plenty of day-trippers. The line’s quiet again now, though. Had a train through yesterday with not a single passenger on it, right through.’

‘Does that worry you?’

Ted shook his head. ‘Not really, no. The line makes money in the summer. It provides a good service for this area.’

‘But if it’s not making money all year round, I’d be worried the railway company might be thinking of … I don’t know … cutting back, or something? There’s a station near one of my friends, up in Yorkshire, that is unmanned now. You have to tell the guard if you want to get off there, and wave a flag if you’re at the station and want the train to stop to pick you up. Do tell me to stop fretting, but I’m worried for your job, Ted.’ She passed him a cup of tea and they went into the parlour to sit down.

‘Bless you, Norah, for worrying about me. But this line is a goods line too, and there’s plenty of trade still coming by rail. Lots of work for me here, managing the goods yard.’ He reached over and patted her knee. ‘My job’s safe enough, don’t you fret. Now then, what are your plans for the week?’

She smiled. ‘Margot wants to feed the ducks in Lynford’s pond, and see the witch-stool, so that’s all easy enough. The boys want you to show them how to operate the signals. They said you promised as much, last year. And I want to walk along the cliffs at Coombe Regis and have an ice cream sitting on the harbour wall.’

‘Might be too cold for that last one, at this time of year,’ Ted laughed.

‘I don’t care. If I’m at the seaside, I want an ice cream, any time of year. I suspect the children would be happy to have one too.’

‘Did someone say ice cream?’ yelled Peter, from the kitchen. ‘Yes please! When, where?’

*

It was Wednesday morning, halfway through Norah’s visit. She’d taken Margot off into the village, for some ‘girl time’ as she’d put it, to feed the ducks and look for squirrels in the park, and do all the things Ted supposed little girls liked to do. Peter and Tom were left in Ted’s charge, on strict instructions to behave, not fight each other, and do exactly as their uncle told them, or they’d miss out on the planned trip the next day to Coombe Regis.

‘Show us how to operate the signals, Uncle Ted? You promised us last year you would.’ Peter was jumping up and down with excitement, as soon as his mother and sister had left.

‘All right, then. We’ve got some time before the next train is due to come through. Now then, you see how there are two tracks running through this station?’

‘The up line and the down line?’ Tom said, looking at Ted for confirmation.

‘That’s right. But actually for most of this line, there’s only one track. This station is one of the passing places along the line. So if a train coming up from Coombe Regis is late, we have to hold the down train from Michelhampton here, because they can’t pass further along. So the signal must be set at stop until the up train has arrived and we know it’s safe.’

‘What if you’ve forgotten whether the up train’s been through or not? I mean, what if you were in the lav or something, when it came through?’ asked Tom.

‘Don’t be stupid. Why would he forget?’ said his brother, but Ted held up a hand.

‘It’s not a stupid question. You’re right, it’s essential that there’s only one train on the track from here to Coombe Regis at any one time, and also only one from here to Rayne’s Cross, the other passing place. And the train drivers need to be certain that the way ahead is clear. So we use tokens.’

‘Tokens?’ Peter looked confused.

‘There is an engraved token for each of the three sections of the line. The train driver cannot progress onto the line until he has the token for it in his possession. So the driver of the train that’s now coming up from Coombe Regis will hand me the token for that section of the line, and I’ll hand it on to the next down train. He can’t leave until he has the token.’

‘Clever!’ Peter’s eyes were shining. ‘Can I hand the token to the driver?’

‘I don’t see why not.’ Ted smiled. Such a little thing, but so exciting. He remembered being 12 himself, longing for the day when he could leave school and come to work on the railway himself. It was all he’d ever wanted to do. ‘We don’t always need the token system, strictly speaking, as often there’s only one train running up and down the line. Though we’ll generally use it anyway. In the summer when it’s busy we run more trains, and they need to be able to pass safely, so the token system is essential then.’

He led them along the side of the track to where the little signal box stood, and ushered them up the few steps inside it. There were four signal levers – one each for each track and each direction. And two points levers, to switch the points where the two tracks became one, just beyond the station in both directions. He showed them all these, and demonstrated how the levers worked – the way to grip them to release the lock and pull down hard until they slotted in place. ‘It’s important they click into position, so they can’t accidentally slip out.’

‘Cor, what would happen if one did slip out of position?’ Tom asked.

‘Could cause a crash, couldn’t it, Uncle Ted?’ said Peter, always wanting to be the one who knew the most.

‘It could. But it’s part of my job to make sure that all signals and points are in the correct positions before I leave the signal box. So look, we’ve got the 11.42 up train coming through soon. The points are set right, but we need to set the up signal to stop. Can you do that, Peter?’

The boy’s eyes shone as he leapt forward to the signal lever and got ready to pull it. Tom’s lower lip quivered, and Ted ruffled the younger boy’s hair. ‘Don’t fret. You’ll get to set the signal to go, when the train’s ready to leave.’ It did the trick, and Tom grinned happily.

Peter managed the signal with no problem. ‘Now then, we need to go back to the platform and get ready to swap the tokens over.’

‘Uncle Ted, can I stay here with the signals, ready to change it to clear?’ Tom was standing to attention, his hand on the signal lever.

‘If you like, but don’t touch anything else. I’ll give you a wave when it’s time to change the signal. All right?’

‘Yes, sir!’ Tom saluted.

Now it was Peter’s turn to pout. ‘I didn’t get to change a signal all by myself, Uncle Ted. I only did it when you were with me. And as I’m the oldest I should have been given more responsibility, not him.’

Ted sighed. He never did quite understand the children’s fine-tuned sense of justice. It was so hard to ensure they were both happy. ‘Well, you can have another turn this afternoon. We’ll keep things fair.’ He led Peter back down to the platform to await the train. It was right on time, and Peter proudly handed over the token to Bill Perkins, the train driver.

‘Good lad. We’ll make a stationmaster of you yet, won’t we, Ted?’ said Bill, grinning.

There was only one person alighting from the train, and no one to pick up, so in no time at all Ted was waving his flag to allow the train to move. But the signal was still at stop. He waved again, and saw little Tom’s answering wave from the steps of the signal box. But still the signal didn’t change.

‘Why doesn’t he change the signal, the silly boy?’ muttered Peter. ‘Shall I go and see?’

‘Give him a chance,’ said Ted, watching the signal box carefully.

‘What’s the hold up?’ Bill leaned out of the cab to ask.

‘My younger nephew’s in charge of changing the signal.’

‘Ha ha! Maybe the poor little nipper can’t manage the heavy lever. You’d best go check on him, Ted, or the train’ll be late and we can’t have that!’

He had a point. Ted hurried up the platform and into the signal box where, sure enough, Tom was pulling on the lever with all his might, leaning all his weight into it and grunting with the effort. ‘I can’t make it change, Uncle Ted! It’s too heavy!’

‘Squeeze the handle, like I showed you, lad. That releases it.’

‘Nnghh!’ Tom did as he was told and the lever released easily, sending him flying backwards across the shed. With a whistle the train shunted forwards. ‘I did it!’

‘You did indeed, young Tom. Well done.’

Ted was sweating. That was the last time he’d let a child handle the signal levers alone. The train had been two minutes late leaving! He’d have to log that, in his notebooks that contained details of every train that passed through – but he wouldn’t log the reason why.

*

Norah and Margot were back at five o’clock. Margot had a bag of sweets in her hand from the village grocery shop, and Norah had a sherbet dip for each of the boys. ‘I hope you’ve been good for your uncle,’ she said, and Peter and Tom both nodded solemnly.

‘Well, off you go inside and play quietly now till teatime,’ Norah told the children, who ran off to the station garden. ‘You’re so good with the children, Teddy. You’d make an excellent father. I’ll put the kettle on for a cuppa.’

‘Thanks, Norah. There’s a train coming through shortly so I’m busy for a bit.’ It was the 17.21. Annie’s train. She’d be here soon, passing through the station, and he wanted to be ready for her, with his hair smoothed down, cap on straight, uniform brushed.

‘I’ll bring the tea through to you,’ Norah called, as she made her way to the little kitchen.

Ted busied himself around the station, emptying a litter bin, straightening chairs in the waiting room, stacking the pile of used magazines. The signal was already at stop, so there was nothing more to do. He went out to the platform and looked along the line – no sign of the train yet, but he didn’t expect to see it. Back in the ticket office he paced up and down until Norah brought through his cup of tea.

‘Here you are, then,’ she said, as she handed it to him.

It was at that moment that the station door opened and in came Annie, wearing her deep-green coat that had a pinched in waistline and a matching neat hat. She nodded to him, pulled out her ticket to show him as usual, and then walked through to the platform. It was a fine day so she sat on a bench on the platform rather than use the ladies’ waiting room that he’d just tidied up for her. His eyes followed her as always, and it was only when she’d taken a seat that he came back to himself, and realised he was holding his tea at an angle, spilling some over his boots.

‘Who is she?’ Norah asked, quietly.

‘Er, her name’s Annie Galbraith, I believe. She works in the National Provincial Bank in Lynford.’

‘You like her, don’t you?’

He turned to stare at his sister. ‘I … I barely know her.’

Norah smiled. ‘You don’t have to be well acquainted to know how you feel about her.’ She took a step closer to Ted and punched his arm, playfully. ‘If I didn’t know better, I’d think my little brother is in love, at last!’

‘I … no … what do you … I mean … well. She’s very beautiful.’ Ted spluttered as he glanced out to the platform where Annie still sat waiting patiently. She looked up, caught his eye and smiled. He was blushing furiously, he knew it, but it was time for him to be on the platform too. The train was due in one minute. ‘Ahem. We’ll talk about this later, Norah.’ He put down his cup of tea on the ticket-office counter, straightened his jacket and strode out to the platform just as the train pulled in. He dared not look at Annie as she climbed aboard the first-class carriage, and was for once thankful when all were aboard, he’d set the signal to clear, handed over the token and waved his flag.

Norah joined him on the platform as the train puffed away. She laid a hand on his arm. ‘I’m sorry if I embarrassed you. It’s just, when that woman walked in – and yes, she is very beautiful – I could see you were smitten. You’re my little brother, Ted. You can’t hide anything from me! Now then, I noticed she didn’t say anything to you. If that was due to my presence, I am sorry.’

Ted shook his head. ‘No, we don’t as a rule hold any conversations when she passes through.’ As a rule? Who was he kidding? He could count on one hand the number of words she’d ever spoken to him.

‘Well, I think you should rectify that,’ said Norah, with a smile and raised eyebrows. ‘Next time you see her, pay her some little compliment. I think she likes you, judging by that lovely smile she gave you. And smile back at her, for goodness’ sake! You stared at her today as though she had two heads!’

Had he really? And would it work, if he overcame his shyness and actually spoke to Annie? He only knew her name and where she worked by following her that day. He couldn’t very well do that again. Norah was right. It was time he struck up a conversation with Annie. He had nothing to lose. In a few days, when Norah and the children had left, he would try it.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_f37389d3-c58f-51d0-ae79-ff7691e092fe)

Tilly (#ulink_f37389d3-c58f-51d0-ae79-ff7691e092fe)

The day after their visit to Lower Berecombe, Ken drove Tilly out to Lynford station. It was a cold but fine day, the smattering of frost that had covered everything overnight was beginning to melt. It was the kind of day, Tilly thought, as they drove along the country lanes between fields dotted with sheep, when in years gone by she’d have felt glad to be alive, joyful just to be a part of such a beautiful world. Maybe one day she’d feel like that again, but it seemed a long way off yet.

‘So if you look over there,’ Ken was saying, dragging her morbid thoughts back to the present, ‘there’s a little glimpse of the viaduct. It’s miles away but just there, see it?’

She looked where he was pointing and yes, way off in the distance she could see the arches of the viaduct spanning the valley. They were high up here, the road winding around the side of a hill before it dipped down to Lynford village. ‘Yes, I see it.’

‘I love that view,’ he said. ‘After your mum died, I used to come here, park just up that lane there, and walk up the hill from where there’s an even better view. Something about gazing into the distance helped put everything into perspective. It made me realise life went on, despite all that had happened to me. I always felt more – well, grounded I suppose – after going up there. Ah, pet. I’m probably talking rubbish, aren’t I? Maybe one day I should take you up there, for a walk. If you’d like to. It might help.’

‘Yes. I think I’d like to,’ Tilly said quietly. She’d never heard her father talk in this way before. He’d never opened up about his feelings after her mum died, or how he’d coped. She should do what she could to help him, but how could she do that when she couldn’t even help herself?

‘So, we’re nearly there,’ Ken said, as he drove down the hill, and through the little village. ‘Worth having a stroll around here too, when you get the chance. Some quaint old buildings. That café there’ – he pointed at an imposing building on a corner – ‘used to be a bank. And down there’s a path to the river Lyn, and there’s a little park and an old witch’s ducking stool that supposedly dates back to the sixteenth century. I reckon it’s a Victorian copy, myself. Anyway, it’s worth a look, and the café does a fantastic range of cakes. I miss the cakes your mum used to make.’

‘She was such a good baker,’ Tilly agreed.

Ken turned into a small car park beside the red brick station building. ‘So. Lynford station. Here we are! There are no steam trains running today – we only do school holidays and weekends from Easter to October. But the station’s open to visitors, and we have a little tea shop, selling cakes.’

Tilly climbed out of the car, and let her father show her proudly around. ‘They’d just begun opening to the public when we first moved here, and I got involved. I couldn’t help but join the society. Your mum laughed when I told her. “You’ve just retired from the railways,” she said, “and now you want to work for them again!” Ah, but this is different, I told her. This is fun. Old-fashioned station, steam trains, tinkering with bits of equipment. None of your automated systems we ended up with.’ Tilly smiled at the story. She could so easily imagine her mum teasing him about his railway obsession.

‘So, in here.’ He led her inside. ‘This is the old station. A ticket office that we’ve restored, ladies’ waiting room, and through there – that’s now the tearooms but would have been the stationmaster’s private rooms. He’d have lived here. There are two bedrooms upstairs.’

The station was nicely done up, with a collection of old tables and chairs in the tearooms and a modern kitchen behind. ‘Want to see upstairs?’ Ken asked. ‘It’s just used for storage now, but back when the railway was operational it’s where the stationmaster and his family would have slept.’

Tilly followed him dutifully upstairs. There was a worn-out carpet on the stairs, and peeling gloss paint on the walls. Someone had stuck photos of the restoration work up with Blu-tack. At the top was a tiny landing with two doors leading off. One was filled with boxes, stacked higgledy-piggledy across the floor. The other contained a single bed with a stained mattress, and more boxes, mostly containing papers and magazines. An electric fan heater stood on top of an old wooden crate.

‘Sometimes if a volunteer wants to work here late in the evening they might kip here, in a sleeping bag,’ Ken explained, as Tilly looked around. ‘Not often, though. There’s rumours of a ghost.’

‘A ghost?’

Ken chuckled. ‘Ah, it’s all rubbish. Just an old building creaking a bit at night. Someone died here once, but I don’t know any details. They say the ghost of that person haunts the building. Alan’ll tell you more about it, if you’re interested. He should be around here somewhere. I’ve never spent the night.’

Tilly shuddered. Nothing would entice her to sleep here, ghost or no ghost. Ena’s words – that railway was the death of my father – ran through her mind. Could this be what she was referring to?

She laid a hand on the nearest crate. ‘What’s in all the boxes?’

‘That’s our archive.’ Ken pulled a face. ‘There’s probably loads of great stuff in there. But who knows? It’s all in such a mess, and no one with any time to sort it out.’ He looked thoughtful for a moment, then turned to Tilly with a querying expression. ‘Don’t suppose you’d like to take it on, pet? Go through it, pull out the interesting bits, throw out the rubbish? You’re good at that kind of thing. We’ve got a website too, that needs someone to keep it up to date. Could be something to … get your teeth into. Help take your mind off … everything.’

Tilly glanced again into the bedrooms and the daunting piles of boxes and papers. ‘I don’t know. Not sure I could.’ Not sure? The way she felt now she was absolutely certain she wouldn’t be able to summon up the energy to root through loads of dusty boxes.

‘All I’m saying, love, is if you want to, there’s a project for you. This railway, it was the saving of me. Working on it after Margaret was gone was the only thing I was getting up for, each day. I just wonder if it could help you, too. You never know.’

*

Back downstairs, Ken led Tilly through the tearooms and into the ticket office. There were a number of tools strewn about and a barrier blocking off the ticket counter. A table had been set up on the opposite side of the room as a makeshift counter.

‘We had all this up and running, but it seems there’s some problem behind the ticket counter,’ Ken explained. ‘An old pipe in there must have corroded and is leaking. Took us ages to see where the water was coming from. Now we’re going to have to strip back all that original panelling, get at the problem, replace the pipe, dry it all out and replace the panelling.’ He shook his head, but he was grinning. ‘One problem after another, in these old buildings.’

Tilly smiled too, despite herself. His enthusiasm was catching, and it was good to see him happy. ‘You love it, don’t you, Dad?’

‘I do indeed, pet. You know me. Never happier than when I’ve got a bit of DIY or an engineering challenge in front of me. Ah. There’s Alan. Come on. I’ll introduce you.’

Tilly followed him out onto the station platform, where an old-fashioned luggage trolley, loaded with a couple of battered old leather suitcases, was artfully arranged beside a vintage bench and a restored Fry’s chocolate machine. A man who looked to be a few years older than her father approached. He was wearing blue overalls just like the ones Ken had worn yesterday. He had a shock of grey hair and kindly eyes. Tilly warmed to him instantly, despite not really feeling up to meeting new people.

‘Ken, lad, this your daughter then? Very pleased to meet you. Going to keep your old man under control, are you?’

Ken chuckled. ‘Yes, Al. This is my Tilly. She’ll be stopping with me for a bit.’

Tilly shook Alan’s hand, and then the two men began chatting about the latest work done on the railway. It was good that her dad had a proper friend here – someone with similar interests to himself, someone he could have a laugh and a joke with, and presumably the occasional pint with, in the local pub. Friends were important when life had thrown you a curve ball.

She tuned out of Ken and Alan’s conversation and gazed around at the restored station. It was built of red brick, with grey slates, in a chalet style. Upstairs she could see a window of one of those little bedrooms, while the downstairs was much bigger, incorporating the ticket office, waiting room, and stationmaster’s quarters that she’d seen. The outside of the building was immaculate; the society had done a fantastic job restoring it. On the platform, period advertising signs and a departure board had been lovingly restored and displayed. As at Lower Berecombe, the platform was only about a foot above the trackbed. But here the platform was neatly edged with grey bricks and there were rails laid, extending in both directions, with sidings branching off just past the station.

‘What do you think?’ Ken asked.

‘Looks great. Do you get many visitors?’

Alan nodded. ‘Oh aye. On the gala days we get thousands. And during the school holidays we do very well, too. Have you shown her the engines? And the museum?’

‘There’s a museum?’ Museums were Tilly’s thing. She could spend hours peering at old photos and artefacts, reading up on the history of a place. Maybe there was something she could get interested in here, after all.

‘Well, sort of,’ Ken said, with an expression Tilly couldn’t quite read. He was plotting something, she thought. ‘It’s over here. I’ll catch up with you later, Al.’

‘Cheers, mate,’ Alan said, as he loped off around the back of the station.

Ken led Tilly along to the end of the platform then around the side of the station building to where an old railway carriage stood on a siding. A set of wooden steps led up to the door at one end. Inside, the seats had been removed and a motley collection of felt-covered boards displayed curling photographs with faded handwritten captions pinned beside them. A handful of old books about steam railways in Dorset lay on a plastic garden chair.

‘It’s not much. You saw our archive, Tillikins. The society is desperate for someone to go through it all and put together some decent displays showing the history of the railway. We’re planning on painting this coach and fitting it out as a proper museum. We’ve no problem doing the practical work, but those boxes of paperwork just scare everyone off. That’s why I hoped …’

‘That I’d take up the challenge?’ Tilly shook her head. The thought of spending the next few weeks rummaging through those boxes, piecing together an enticing tale of the railway would have appealed to her once, but now … no. It was too big a job, too daunting. ‘Not sure, Dad. I feel at the moment like I couldn’t concentrate on something like that. Maybe later on, I could give it a go.’ When she felt she could last more than twenty minutes without crying, perhaps.

Ken hugged her. ‘That’s fine by me, pet. In your own time. Come on. I need to show you the engine shed. We’ve got a replica of one of the original engines in there. Coombe Wanderer, she’s called. Built by Manning Wardle, the same company that built the originals, believe it or not. She’s a beauty. We’ll have her in action at the next gala day.’

*

Tilly spent much of the day with Ken at the old station, mostly just sitting in the sunshine on a restored wrought-iron bench painted in Southern Railway green, on the platform. Ken handed her a cup of tea from the station café and a couple of editions of the Michelhampton and Coombe Regis Railway Society’s magazine to flick through, but she struggled to concentrate. She’d read a few sentences then find her mind wandering off over the events of the last few weeks. And then her eyes would fill with tears again, and she’d have to raise them from the magazine and focus on her father and Alan, who were tinkering with a railway signal on the opposite track.

Ken drove her home in the mid-afternoon and began work on preparing the dinner for that night.