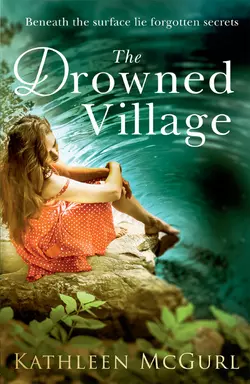

The Drowned Village

Kathleen McGurl

‘Drew me straight in and kept me hooked.’ Linda Finlay‘Really touching, a gently gripping mystery.’ Kerry BarrettBeneath the surface lie forgotten secrets…A village destroyedIt’s the summer of 1935 and eleven-year-old Stella Walker is preparing to leave her home forever. Forced to evacuate to make way for a new reservoir, the village of Brackendale Green will soon be lost. But before the water has even reached them, a dreadful event threatens to tear Stella’s family apart.An uncovered secretPresent day, and a fierce summer has dried up the lake and revealed the remnants of the deserted village. Now an old woman, Stella begs her granddaughter Laura to make the journey she can’t. She’s sure the village still holds answers for her but, with only days until the floodwaters start to rise again, Laura is in a race against time to solve the mysteries of Stella’s almost forgotten past.Haunting and evocative, The Drowned Village reaches across the decades in an unforgettable tale of love, loss and family.

KATHLEEN McGURL lives near the sea in Bournemouth, UK, with her husband and elderly tabby cat. She has two sons who are now grown up and have left home. She began her writing career creating short stories, and sold dozens to women’s magazines in the UK and Australia. Then she got side-tracked onto family history research – which led eventually to writing novels with genealogy themes. She has always been fascinated by the past, and the ways in which it can influence the present, and enjoys exploring these links in her novels.

When not writing or working at her full-time job in IT, she likes to go out running. She also adores mountains and is never happier than when striding across the Lake District fells, following a route from a Wainwright guidebook.

You can find out more at her website: http://kathleenmcgurl.com/ (http://kathleenmcgurl.com/), or follow her on Twitter: @KathMcGurl (https://twitter.com/KathMcGurl).

Also by Kathleen McGurl

The Emerald Comb

The Pearl Locket

The Daughters of Red Hill Hall

The Girl from Ballymor

Copyright (#ulink_7c83f4b4-f58a-5d83-b9a1-20d7cfabef2e)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Kathleen McGurl 2018

Kathleen McGurl asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008236984

For my husband Ignatius.

May there be many more Lake District

walking holidays ahead of us.

Contents

Cover (#u08802a44-40ff-5ac7-9660-3785f93bef29)

About the Author (#u01f134bd-582a-5d3c-b115-e16893352461)

Also by Kathleen McGurl (#ulink_a91161bd-49de-5e31-9938-b1b2ff4959e0)

Title Page (#ub1e9fe27-3667-5b2f-ae6c-1bf60c192925)

Copyright (#ulink_02a0f296-0cf1-55f5-af8e-59416ea390f4)

Dedication (#udfb31026-8e94-593a-b0d8-5dc2a5422596)

Prologue (#ulink_012e96dc-3a25-5806-bfde-82ddd5d213e6)

Chapter 1: LAURA, PRESENT DAY (#ulink_e8e0425c-96c3-5b8c-bad9-a22b9c3d6af0)

Chapter 2: JED, APRIL 1935 (#ulink_ceded73f-0dcd-5129-946e-bc1d3c23c337)

Chapter 3: LAURA (#ulink_80c90c66-2b9c-583b-9f8d-3700f107238b)

Chapter 4: JED (#ulink_1ecd6837-4ecd-526e-b693-515fa92e2440)

Chapter 5: LAURA (#ulink_85c47f28-2e4d-5c56-b4d3-ea2e4197becf)

Chapter 6: JED (#ulink_0af32bb5-dcd7-531e-a154-a0bdd0ba6902)

Chapter 7: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8: JED (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: JED (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: JED (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: STELLA, JULY 1935 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: STELLA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: STELLA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: STELLA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: STELLA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: JED, JULY 1935 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: STELLA, JANUARY 1936 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: STELLA, 1956 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: LAURA (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_2424c398-263b-57f4-8fba-d75111481d21)

It was the same dream. All these years, always the same dream. It was cold, snowing, and she was wearing only a thin cardigan over a cotton frock. On her feet were flimsy plimsolls. The sky was white, all colour had been sucked out of the countryside, everything was monochrome. There was mud underfoot, squelching, pulling at her shoes, threatening to claim them and never give them back. On either side of her were the walls of the houses – only half height now, reaching to her waist or shoulder at most. All the roofs were gone, doors and window shutters hung off their hinges, everywhere was rubble, the sad remains of a once happy life.

And then came the water. Icy cold, nibbling first at her toes, then sloshing around her ankles, and up to her knees. She was wading through it, struggling onwards, reaching out in front of her with both hands, stretching, leaning, grasping – but always it was just out of reach. No matter how hard she tried, she could not quite touch it, and always the water was rising higher and higher, the cold of it turning her feet and hands to stone.

Ahead, in the distance, was her father’s face. Torn with anguish, saying – no, shouting – something at her. She couldn’t hear his words; they were drowned by the sounds of rushing water, rising tides, a burst dam, a wall of water engulfing everything around her. She knew she had to reach it – that was what he wanted. If only she could get hold of it; but still, it was tantalisingly beyond her reach.

Now the water was up to her chest, her neck, and she was trying to swim but something was pulling her under, into the icy depths, and still she couldn’t reach the thing she had come here for. Her chest was tight, burning with the effort to breathe as the cold engulfed her and panic rose within her.

As always, just as the water washed over her head, filling her lungs and blurring her vision, she awoke, sweating, her heart racing, and her fingers – old and gnarled now, not the smooth youthful hands of her dream – still stretching out to try to touch the battered old tea caddy . . .

Chapter 1 (#ulink_ae4a236f-35af-5ddc-bb82-2c2d24bb7310)

LAURA, PRESENT DAY (#ulink_ae4a236f-35af-5ddc-bb82-2c2d24bb7310)

The TV was turned up so loud that Laura could hear it clearly even from the kitchen, where she was preparing the evening meal of shepherd’s pie. She popped the dish into the oven and went through to the living room.

‘Laura, love, you must watch this! Wait a moment, while I wind it back a bit.’ Stella picked up the remote control and began stabbing randomly at buttons.

‘Let me, Gran,’ Laura said, gently taking the remote from her. ‘What do you want me to see? Should I go back to the beginning of the news?’ Thank goodness you could pause and rewind live TV, she thought. Her grandmother’s hearing was not so good any more, and despite having the sound turned up so loud, she still often needed to watch snippets again, or turn on the subtitles.

‘No, just this bit,’ Stella said, peering intently at the screen. ‘There. Play it from now.’

An image of mountains and moorlands, purple heather and dry brown bracken appeared on the TV, then the camera panned round to show a dried-up lake, where a reporter was picking his way across a bed of cracked mud. Here and there were low stone walls, an iron gate, tree stumps.

The reporter stopped beside the remains of a building.

‘Usually, if I was standing here, the water level would be over my head. But the extended drought this summer means that Bereswater Reservoir has almost completely dried up, exposing the ruins of the village of Brackendale Green, once home to a couple of hundred people before the dam was built.’

‘There! Brackendale Green!’ Stella’s eyes were shining.

‘What about it, Gran?’

‘It’s – it’s where I was born! Where I grew up! Until I was eleven or so, when they built the dam and then Pa was . . . Pa went . . . and we all had to move out.’

‘Wow, Gran, I never knew.’ Laura watched with renewed interest now. She knew her grandmother came from the Lake District originally but realised in shame that she had never asked exactly where. Stella had never talked much about her early life, although she was always happy to recount stories from her days as a young actress in London, before she’d married and had her son, Laura’s father.

‘That’s the main street he’s walking down,’ Stella said, her eyes still fixed on the flickering screen. ‘The pub – oh now what was it called? Oh yes, the Lost Sheep! Silly name for a pub in the fells. Sheep were always lost, but they’d find their way back, most of them. Those dear old Herdwicks, they knew their way home. What was I saying? Oh yes – the pub was there. Right about where he’s standing now. Pa did like a pint of ale in there of an evening.’

‘In the 1930s, the population of Brackendale Green was approximately one hundred and fifty residents, men, women and children,’ the reporter went on. ‘This number was briefly swelled when the dam-building began, but in later stages the workers were housed in prefab buildings nearer the site of the dam. The village itself was demolished just before the valley flooded, but as you can see, the lower parts of the walls are still clearly visible. Here, there’s a stone bridge that crossed the stream that ran through the valley. Over there, an iron gate lies in the dried mud, presumably once the entrance to a field. In here –’ he passed through the remains of a doorway – ‘some of the floorboards survive beneath the mud. The fireplace is intact, and there’s even a small stove set within it.’

The camera panned round the room, showing the items he’d spoken about.

‘Funny, seeing it again after all these years,’ Stella said, her voice cracking a little. ‘When you think of all that happened there . . .’

Laura glanced at her in concern. ‘What happened there?’

‘Oh, I mean all the people who lived and worked there, were born there and grew up. That’s all I mean, love. Nothing more.’ Stella watched as the news programme cut back to the studio and the presenter began talking about the state of the economy. ‘Switch it off now, love, will you?’

‘Sure.’ Laura silenced the TV. ‘Gran, you’ve never mentioned this before. I’d love to know more about it. What was the village called? Bracken-something?’

‘Brackendale Green. Oh, it was all so long ago.’ Stella’s eyes misted over and she stared at the blank TV screen, deep in thought.

‘Fascinating, though. Will you tell me more about it?’ Laura glanced at her watch. ‘There’s about twenty minutes till dinner’s ready. I’ll go and set the table for us now, but then I’d love you to tell me more about your childhood. Will you?’

There was a strange look on Stella’s face. Laura supposed it must be a bit of a shock, seeing the ruins of the place where you’d been born, exposed to the elements after more than eighty years underwater. But there was more to it than that. Stella looked as though she was hiding something, fighting with herself over whether to confide in Laura or not.

Well, maybe she’d talk, over dinner or afterwards. Laura went back out to the kitchen to set the table. It was a Friday, and they’d begun a tradition of opening a bottle of wine together. Stella only ever drank a glass a night, so one bottle would do them both Friday and Saturday nights. Laura chose a Pinot Noir and uncorked it. Another Friday night in with her ninety-year-old grandmother. Most women of her age would be out partying, if they weren’t married with small children yet. And up to a couple of months before, Laura would have been out clubbing on a weekend night too – with Stuart and Martine. She’d thought she had a perfect set-up – renting a flat with her long-term boyfriend Stuart, with her best mate Martine subletting the spare room. Lots of fun and giggles, and if sometimes Stuart had complained at her for being late back from work after a client had needed extra care, or if Martine had bitched at her for not always wanting to go clubbing every weekend, on the whole it had been good. At least, it had been good until she’d come home unwell one day, and found Stuart in bed with Martine. Laura grimaced as she remembered that day. Her life had fallen apart, and if it wasn’t for Gran, and having to hold herself together for her clients, she was certain she’d have had a full breakdown.

Stella made a much better flatmate. At ninety, she needed a lot of care, but that was Laura’s job anyway, and so she’d taken over most of her grandmother’s needs. The agency sent other carers to cover on the days when Laura’s own agency needed her elsewhere. So far it had worked out well. And Laura felt she’d done a good job keeping cheerful – on the outside at least.

The oven beeped, and Laura removed the pie from the oven and set it to rest for a few minutes on the table. She poured two glasses of wine.

‘Gran? Dinner’s ready.’ She went back through to the sitting room where Stella was still staring at the blank television. She placed the walking frame in front of her and steadied it while Stella pushed herself to her feet and took hold of the frame.

‘Ooh, my old knees,’ she said with a smile. ‘You’d never think I used to be able to jitterbug, when you look at me now.’

‘Gran, you’re doing brilliantly. Hope I’m as fit as you when I’m your age.’ Laura helped the old lady to sit down at the kitchen table, and began serving the meal.

‘I’ve had a thought, Laura, dear.’ Stella put down her cutlery before she’d taken so much as a mouthful, and fixed her granddaughter with a firm stare.

‘Oh-oh. What is it, Gran?’

‘It’s time you had a holiday. You haven’t had one this summer, and after all that nastiness, you need to get away.’

‘I need to look after you!’ But that ‘nastiness’, as Gran put it, had almost swamped her, she had to admit it.

‘The agency can send someone else. I managed perfectly well before you moved in. Don’t get me wrong, Laura, I love having you here, but you need to live your own life as well. You’ve barely been out since you moved here.’

She was right, but there was no one Laura wanted to go out with. All her friends had been Stuart and Martine’s friends as well, and seeing any of them would mean hearing about how loved-up they were, how they were made for each other and how great it was they were able to be together at last, as if she, Laura, had been purposefully keeping them apart! When she’d lost Stuart she’d lost the whole of her old life. And she had not done much about building herself a new life yet. It was too soon, she kept telling herself, although she knew that sooner or later she’d need to get back out there making friends again. Perhaps in time even meet a new man. Someone who wouldn’t discard her like a used tissue as soon as he’d had enough. But right now she couldn’t even contemplate that happening.

‘Respite care, they call it – to give you a break. From me.’

‘Aw, Gran, I don’t need a break from you. You’re easy to look after.’ Laura reached across the table to take her grandmother’s hand.

‘Oh, I’m not really. Well, I may be easier than some of your clients, as I’ve still got all my marbles, but I’m under no illusions about how difficult your job is. You do it all day, then come home to more of it in the evening with me. So, as I said, I think it is time you had a holiday. And I have an idea of where you might like to go.’

‘Really?’ Laura raised her eyebrows in amusement. Stella wasn’t usually this bossy. But it was a thought – a holiday might do her good. Stella was right that she hadn’t been away anywhere since the previous summer, when she and Stuart had spent a long weekend in Barcelona, before travelling along the coast to the beach resort of Lloret de Mar where they’d met up with Martine. For all she knew, Stuart and Martine’s affair had started there. Perhaps a holiday on her own would help her forget them and move on.

‘The Lake District,’ Stella said triumphantly. ‘I know how much you love the mountains. You could do a bit of walking. And . . .’

‘And?’ Get her head together and her life sorted out?

‘Maybe you’d like to visit Brackendale Green,’ Stella said, looking at Laura out of the corner of her eye as if she was unsure what the reaction would be.

‘The drowned village where you were born, that was on the news earlier?’

‘That’s the one. I mean, I know you’re into family history and all that. So I thought, perhaps now’s the chance to see the place. And maybe it’d help you . . . you know . . . move on. Since all the nastiness it’s as though you’re just treading water, living here with me, not going out at all. At your age there ought to be more in your life. A holiday might help you – what’s that modern computer phrase you young people use? Reboot. Reboot your life. What do you think?’

‘I think, eat your dinner before it goes cold, and let me consider it,’ Laura said, smiling. Dear old Gran – always had her best interests at heart. But she was probably right in that it was time for a reboot.

Stella glared at her, then broke into a broad smile. ‘Yes, you think about it, love. But don’t take too long or it’ll rain and the village will be underwater again.’

Laura considered Stella’s proposal as she ate. Gran was right – she did love the mountains. And it would be fascinating to see the remains of the village where Gran had been born. If she could get some time off next week, perhaps, and arrange alternative care for Gran, she could pack up a rucksack, dig out her old tent and sleeping bag from pre-Stuart days, and drive up there. If she camped then the whole trip would be pretty cheap. There was a campsite in Patterdale where she’d stayed a few times years ago. Or maybe there’d be another one closer to Bereswater and Brackendale Green. She could look online. As long as there was a pub that did food nearby, she didn’t mind where she stayed. She could do some hiking, think about her future and try to put the mess with Stuart and Martine fully behind her. Just a few months ago she’d thought it was only a matter of time before Stuart proposed. She’d assumed they’d marry and Martine would be her bridesmaid and hen-night organiser. Huh. How blind she’d been!

‘Well?’ Stella put her knife and fork neatly together on her plate. She hadn’t eaten everything but these days her appetite was tiny, and Laura had learned not to try to persuade her to eat more. That worked with some of her clients but Gran would just dig her heels in.

‘What?’

‘Have you decided? Will you take a holiday?’

Laura smiled. ‘You know, I think I might. Since you seem so eager to get rid of me! I do quite fancy a trip to the Lake District, and I’ve still got my old tent somewhere.’

‘Good! I’m really pleased. It’ll do you good. You need it and you deserve it. The dinner was delicious, by the way. I’d help you wash up, if I could, but thankfully I can’t.’ Stella grinned impishly, and Laura chuckled at the joke she made after every evening meal.

‘No problem, Gran, I’ll do it this time,’ she said, parroting the usual response.

As she washed up, a thought came to her. Where was that old tent, and her sleeping bag? She’d brought a car full of stuff to Gran’s when she’d left the flat she’d shared with Stuart, but were the tent and sleeping bag amongst it all? Not that she could remember. With a sinking feeling she remembered that she’d stored it in an eaves cupboard at the flat – the one in Martine’s bedroom – and she had not checked that cupboard when she moved out. It had all been a bit of a rush.

Not for the first time, she relived that hideous day in her mind as she worked. She’d gone home early because she could feel herself coming down with a cold. In her job, it was not a good idea to battle on through bugs and germs, as it was too easy to pass them on to her frailer clients. She’d called the office, who had been able to get someone else to do her last two care visits of the day, and had gratefully driven back to the flat, picking up some Beecham’s cold cures on the way. She’d let herself in, expecting the flat to be empty, but then had heard sounds coming from the bedroom she shared with Stuart. He ought to have been at work. Thinking perhaps someone had broken in, she’d grabbed a golfing umbrella from the hat stand as the nearest thing she had to a weapon, steeled herself, then burst in through the bedroom door, shouting and brandishing the umbrella. The first thing she’d seen was Stuart’s bare bum thrusting up and down; the second thing was Martine’s shocked face, peering over his shoulder.

Stuart looked around. ‘Fuck, Lols, you gave me a fright! What’s with the screaming and all?’

‘Laura, oh my God!’ Martine shuffled out from underneath Stuart, grabbed the nearest item to cover herself – Laura’s fleecy dressing gown – and pushed past Laura, out of the room.

Laura was speechless. How long she had stood there, staring at Stuart, she didn’t know. It could have been two seconds or twenty minutes. Her mind was in turmoil. Stuart? And Martine? Martine, who she’d considered her best friend. Stuart was scrabbling around for his clothes, which were strewn across the floor. As he stood up to pull on his underpants Laura finally found her voice. ‘How long?’

‘You what?’

‘How long – has this been going on?’

‘What?’

‘You and Martine, of course! What do you think I’m talking about? How long have you been . . . shagging her?’ She spat the word out.

‘Shit, I dunno, Lols, not long, it’s just . . .’

‘Ten months.’ Martine was standing behind her, now dressed in her own clothes. ‘Sorry, Laura. You had to find out sooner or later but I guess this wasn’t the best way. Stu, I said you should have told her.’

‘Couldn’t find the right time, hon. Well, she knows now. Sorry, Lols.’ Stuart reached out a hand, and Laura instinctively stepped forward to take it, then realised he was reaching for Martine. ‘She’s just, well, more my type, I guess. Come on, Lols, we had some good times but it hasn’t been working for a while. You know that. Martine and I kind of drifted together, as you and I have drifted apart.’

Drifted apart? Had they? Well, they hadn’t had as many evenings together as a couple lately, what with Laura’s recent shift patterns which had meant she’d been working till ten p.m. five nights a week. The other two nights if they went out Martine had always come with them. And – ten months? Ten! Laura could not seem to form any sentences to respond. It was all too much to take in at once. She’d been living a lie for nearly a year!

‘Lols? I guess maybe you and Martine should swap rooms. I mean, now it’s all out in the open . . .’ Stuart said, with a shrug.

That did it. ‘Swap rooms? You think you just move me into the spare room now you’re bored of me, and Martine into our room? It’s as easy as that? You bastard, Stuart. You are a complete and utter GIT! And you –’ Laura turned to Martine – ‘how even could you? I thought you were my friend. My best friend. Well, fuck you.’ She picked up the nearest object to hand – a ring-binder folder of Stuart’s containing details of his work projects – and flung it across the room at them both. Satisfyingly, it popped open in mid-air, showering papers everywhere.

‘Laura, for fuck’s sake, that stuff’s important!’ Stuart began gathering up the loose papers.

‘More important than me, clearly.’ Laura crossed the room, trampling across the papers, and flung open the wardrobe. She grabbed a holdall and began throwing her clothes into it.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Leaving you two lovebirds – what does it look like? You can refund me the rent I’ve paid for this month. I’ll collect the rest of my stuff tomorrow when you’re out.’ She tried to close the bag but the zip got caught in a woolly jumper she’d rammed in the top.

‘Where will you go?’ asked Martine. She at least had the grace to look mortified, unlike Stuart who seemed merely annoyed that he’d been found out.

‘Why the fuck should you even care?’ Laura swept an assortment of toiletries, make-up and jewellery from the top of the chest of drawers into a carrier bag. She leaned over the bed to grab her half-read book from the top of the bedside cabinet and Stuart cringed as though he thought she was about to hit him. ‘I’m going. You can move your stuff in tomorrow when I’ve cleared it out properly.’ And with that, she’d stormed out of the flat, banging the door so hard that their downstairs neighbour stuck his head out to see what was going on.

In her car, she’d sat breathing deeply for a few minutes. She’d left the cold and flu remedies she’d bought in the flat, and was feeling worse. Not surprising, really, she told herself. It’s not every day you lose your boyfriend, your best mate and your home all while trying to battle the onset of a cold. Where would she go? And then the tears had come.

Now, finishing drying up the dinner things and with unbidden tears trailing down her cheeks at the painful memories, she recalled it was at that moment, her lowest, most despairing point, that a text had arrived, from her gran. Dear Laura, the text read, Stella being of the generation that felt all written communication should be properly spelt and punctuated, if you get the chance could you pick up a pint of milk for me and drop it round? Clumsy old thing that I am, I dropped the carton all over the floor, and now there’s none for my bedtime Ovaltine. Thank you, with love from Gran.

And that was when she’d worked out her plan. She would ask if she could stay with Stella until she could work something else out. What that something else would be she had no idea. In return she could help with Gran’s care, reducing her costs. She’d bought more cold remedies and the milk, and turned up on her grandmother’s doorstep, her eyes red and her nose streaming. Stella had been horrified by what had happened but delighted by the idea of having Laura to live with her, telling her she could stay for as long as she wanted.

Laura put away the last of the dishes, splashed water on her face and dried her eyes, then picked up her wine glass and went through to the sitting room where Stella was quietly knitting squares for a blanket. The cat, Jasper, was curled up beside her, battling with himself. He knew he was not allowed to play with the knitting wool but oh, how he wanted to! His eyes watched the yarn dancing across Stella’s lap, and every now and then he would twitch as though he was about to go for it.

‘Do you realise I’ve been living here with you for two months now?’ Laura said, as she gave Jasper a stroke and sat down.

‘Nearly three months, dear. You arrived on June the sixth – I remember because it was the D-Day anniversary – and now it is August the twenty-eighth. Are you fed up with your old gran yet?’

‘Not at all – I love being here!’ Laura wasn’t lying. It had all worked out better than she could have hoped. Gran had offered a sympathetic ear, some gently given advice, a comfortable room to sleep in, and was great company when Laura wasn’t working. No matter that her parents lived in Australia – when you had a gran like Stella! And although Laura had not yet done much about rebuilding her life, she knew that her sojourn with Gran had at least given her time to get over Stuart. Was she over him? She hoped so, but did still find herself crying herself to sleep sometimes, even though she knew he wasn’t worth it.

‘But you do need a holiday,’ prompted Stella, with a questioning glance at Laura.

Laura smiled. ‘Yes, I am owed loads of leave, and it would be lovely to see where you lived. I’ll call round to the flat tomorrow and try to retrieve my tent and sleeping bag that I left there, and I’ll talk to Ewan in the office about booking the time off, and getting someone to cover your care. Ewan’s a mate of mine. He’ll sort it out for me, even though it’s short notice. Thanks for the suggestion, Gran!’ And while she was away she’d have a good long think about her future and make sure she was fully over Stuart, she decided.

She held up her wine glass and Stella clinked it with her knitting needles. The old lady’s expression held something that Laura couldn’t quite read. She seemed pleased Laura had decided to go to Brackendale Green but at the same time, it was as though she was fighting an internal battle. She was definitely hiding something.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_c3313aee-1b23-5ba4-9c01-e3fe867d53fc)

JED, APRIL 1935 (#ulink_c3313aee-1b23-5ba4-9c01-e3fe867d53fc)

Jed held tightly to his daughter Stella’s hand as they walked up the steep track that led up on to the fells behind the village. Three dozen mourners followed behind them. The coffin containing his beloved Edie had been taken by road, in the hearse, to Glydesdale in the next valley where she would be buried, but Jed had chosen to walk the old way, the traditional route over the hills, to reach the church.

‘All right, lass?’ he asked Stella, and received a mute nod in reply. The poor mite, of course she was missing her ma. No child of ten years old ought to be left motherless. No child of two, either, Jed thought, thinking of little Jessie whom he’d left behind in Brackendale Green being cared for by a neighbour. But Edie had died, of cancer, leaving Jed and the two girls alone.

It broke his heart that they could not bury her in St Isidore’s Church in Brackendale Green, where generations of his family had been buried. But the dam-building had begun, there were compulsory purchase orders on every house in Brackendale, and the village’s days were numbered. In another year or maybe even less everyone would have to move out. Where he, Stella and Jessie would go or what he would do for a living Jed had no idea. He could not think that far ahead. The last year had been taken up with caring for Edie, and now she was gone he would need to figure out how he could manage to look after the girls and still work. And then there was his father, Isaac, who was increasingly frail and also dependent on Jed for support.

Well, all those worries would have to wait until Edie was safe underground in Glydesdale churchyard. He took a deep breath. At least the weather was fine for her burial. It was the kind of day Edie had always loved – springtime, with blue skies, clear air, bright green foliage on the trees and bushes, and down in the valleys, an abundance of fluffy black Herdwick lambs on their spindly legs. A time of rebirth and hope for the future. But not this year. This year it was a time of death and fear of what was to come.

‘Is it much further?’ Stella asked. She was usually a good little walker, but the past few weeks had been hard on her. Jed had relied on her to prepare food and look after her sister, while he sat at Edie’s side.

‘Not so far now,’ he replied with a reassuring smile. They walked on in silence, but a moment later when Stella stumbled on a rough section of the track, he scooped her up onto his broad shoulders. ‘I’ll carry you for a bit, lass, to give you a rest.’

‘Thanks, Pa,’ she said, as she tucked her feet under his arms and held his upraised hands for balance. He gritted his teeth with the effort of walking uphill with her weight on his shoulders. He’d not carried her like this since she was smaller, and it was tough going, but she was his daughter so she could not be a burden. He could do this.

‘Stella, get down, you’re a big enough girl to walk it yourself without making your father carry you.’ It was Maggie, Jed’s neighbour, who’d caught up alongside them.

‘Ah, she’s all right up there, Maggie. The poor lass is exhausted so I don’t mind carrying her a while.’ Maggie had been a good friend throughout Edie’s illness. She’d helped nurse her, she’d brought in pots of mutton stew for their dinner, and once, she’d cared for Jessie while Stella was at school, to allow Jed to stay with Edie.

‘She looks so heavy, such a burden for you. Well, we’re almost at the top – then perhaps she can walk by herself. You can’t be carried all the way to your own mother’s funeral, now can you?’

‘Pa, I’ll walk now,’ Stella said wearily, and Jed hoisted her down again. The child hung back behind him with some of the other mourners, as Maggie fell into step alongside him. Stella didn’t much like Maggie, he knew.

‘That’s better,’ Maggie said. ‘Now we can talk as adults. Jed, you’ll need help managing the girls, won’t you? I mean, I’ll do what I can for you, but long term, you’ll need someone living in. You’ll need to take another wife.’

‘For the Lord’s sake, Maggie, I’ve not yet buried my first wife!’ Jed could not help blurting out the words. ‘Give me a chance, woman.’

Maggie had the grace to hang her head. ‘I’m sorry. You know me, Jed. Sometimes I speak my mind before I think it through properly.’ She reached out to touch his arm. ‘I want only the best for you, never forget that.’

Jed softened his expression. ‘Aye, Maggie, I know that.’

They walked on. Maggie paused to flick a stone out of her shoe, and Stella then ran up to take her place beside Jed once more, slipping her little hand into his roughened one.

‘I was thinking, Pa, that Ma would have liked this walk, and with all the village coming too. Perhaps we should have carried her over this way to the church.’

‘It’d have been a struggle, lass. But you know, a hundred years ago that’s what the people of Brackendale did with their dead. Before St Isidore’s graveyard was consecrated, coffins were carried over here all the way to Glydesdale for burial. That’s why it’s called the Old Corpse Road. See that flat stone, there?’

Stella looked where he was pointing, at a large flat-topped stone just off the path.

‘It’s a lych-stone. The men would have placed the coffin there for a rest. There are a few of them on this route, and then the final one in the lych-gate of the Glydesdale church.’

Stella shuddered. ‘Are there ghosts up here, then? If so many dead bodies were carried along this path?’

Jed smiled sadly at her. ‘Who knows, lass? Perhaps there are. Well, we need to walk a bit faster if we’re to get to Glydesdale in time to meet your ma’s coffin there. Can you manage it?’

She nodded solemnly, and quickened her pace. Jed matched it, and the crowd behind did too. So many from the village were coming to the funeral. Everyone except Janie Earnshaw, Maggie’s mother, who’d offered to stay behind and take care of little Jessie as she had to stay to look after her sister Susie anyway. A funeral was no place for someone like poor Susie.

The sun was climbing higher and the day was warming up from its frosty start. Jed checked his pocket watch – the one that his father, Isaac, had passed on to him. They would be on time, as long as they didn’t slow up at all. In any case, the vicar would surely not start the service without them. Jed was still glad he had chosen to walk rather than ride in the hearse with Edie, or in a motorcar following it. The fresh air and exercise after the days stuck indoors at Edie’s sickbed were doing him good, helping him to realise that life would still go on and it was up to him, for the sake of the girls, to make the best of it. Though how he would manage it he didn’t know. He’d lost his wife and soon he would lose his home, his workshop, his business as a mechanic, and indeed his whole community, the village where he was born and had lived all his life. Times were tough. But he’d promised Edie, as she lay dying, that he would give the girls a good life. They’d want for nothing, if it was within his power to provide it.

Stella tugged on his hand. ‘Look!’ She was pointing high above them, where a skylark was singing its heart out. ‘It’s Ma. She’s telling us she’s all right, and that it doesn’t hurt any more, and that she wants us to be happy.’

Jed looked up, and blinked against the bright sunlight. ‘Yes, lass, perhaps it is your ma. We’ll do our best to be happy, eh, after today at any rate.’ His voice broke a little as he spoke. He hadn’t yet told Stella that they would have to move out of their home in a year. She knew about the dam, of course – she’d seen the land where it was to be sited being prepared, the new road being built for the workmen to use. And it had been impossible to prevent her from hearing the talk in the village. It had been almost the only topic of conversation for months, ever since that first meeting when officials from the water board had called the villagers together in the Lost Sheep and told them their valley was to be flooded to build a reservoir. The water would be piped all the way to Manchester. So Stella knew, but whether she had worked out that they would not have long left in the village Jed didn’t know. And now was not the time to talk about it.

They were descending now, into the Glydesdale valley. The familiar mountains surrounding Brackendale were out of sight, and instead there was a new vista – steep screes tumbling down to meet the lush fields of Glydesdale, a few farms dotted through the valley and a little cluster of cottages surrounding the church. Soon they would join the road at the bottom that followed the stream through the dale to the village and the church where Jed would be reunited with Edie’s coffin, before it was put into the ground. He’d be walking this route many more times over the next year, he knew, coming to visit her grave. And after that, when Brackendale was evacuated, who knew where he’d be living. He could only hope that he would still be within easy reach of the Glydesdale church so he’d be able to continue paying his respects.

Edie’s older sister, Winnie, a spinster who lived in the nearby town of Penrith, met them by the church lych-gate. Her eyes were red-rimmed. ‘One so young as Edie should never have to be buried,’ she said, between her sobs, and Jed nodded in reply, swallowing hard, not trusting himself to say anything. He did not want to break down in front of Stella, whose hand he held tightly throughout the quiet and sombre service. The girl was so brave, he thought. Only a few gentle sniffs gave away the fact that she was weeping. She held her head high throughout, and stepped forward to throw a handful of dirt into the grave when he nudged her. Only then did she have to dash away a tear.

As they walked away from the grave and people started heading back up the track that led over the fells and back to Brackendale, Jed began to regret his decision to walk. Poor Stella – the child had had enough. How could he have expected her to walk all the way here and back again? She was exhausted. He looked around for someone who might have driven the long way round from Brackendale. Perhaps someone would be able to give her a lift. But almost the whole village had walked with him, as a sign of solidarity. He had welcomed it, but right now he could do with someone who had a motor car, or at least a pony and trap. Winnie had travelled by bus, and hurried off after the service to catch the one back to Penrith, after pressing Jed’s hand and urging him to stay in touch.

‘Jed Walker, isn’t it? I am sorry for your loss.’

He spun around to see who was speaking. She was a well-dressed woman of perhaps forty, wearing a tailored black coat and a neat hat, and carrying a shiny black handbag.

‘Aye, I’m Jed Walker,’ he answered.

She held out a black-gloved hand. ‘Alexandria Pendleton. Your wife used to be my housemaid, before she married. I live up at the manor.’

Of course, he recognised her now. She was from the ‘big house’ as the village folk liked to call it. In days gone by, before the Great War, the Pendletons had owned most of the land around here. But now there was just the manor house and one farm. The current squire of the manor worked in government and spent most of the week in London, travelling up and down the country each week by rail. Jed shook her hand, ashamed of his rough workman’s hands against her soft leather. ‘Pleased to meet you, ma’am.’

‘Edie was a good worker. We missed her when she left us to get married. So tragic that she has died so young. Oh, is this your daughter?’

Stella had sidled up to Jed and once again slipped her hand into his.

‘Aye, this is my eldest. Stella, say hello to the lady.’

Stella bent her knees in an approximation of a curtsey, then stepped back so she was partly behind Jed. She was hiding her tear-stained face, he realised.

‘Sorry about the lass. It’s been a hard time for her, and we had a long walk over the fells from Brackendale.’

‘Surely you’re not going to make her walk back as well?’ Mrs Pendleton looked shocked. ‘Wait there a moment.’ She trotted off across the churchyard in her high-heeled shoes, and caught the arm of a man in a chauffeur’s cap and jacket. Jed watched as she spoke to him; he nodded, and then she returned to Jed and Stella.

‘You shall ride back to Brackendale in my motorcar. Thomas will take me home first for I have much to do, and then he will return here to take you and the child home.’ She nodded curtly, a woman who was clearly used to being obeyed.

‘Thank you. That is very kind,’ Jed replied.

‘It is nothing. You can wait by the lych-gate.’ Mrs Pendleton took her leave, and walked over to the front of the church where her Bentley was waiting.

‘Come on, lass. We’ll wait where she said, and then we’ll get a ride in a big, powerful motorcar.’ Jed took Stella’s hand and began to walk over to the lych-gate. But before they had got very far, Maggie approached.

‘What was all that about? Hobnobbing with the gentry now, are you?’ She gave him a quirky smile as if to show she was teasing. Jed felt irritated. Why couldn’t the woman see that today, the day he buried his wife, was no time to be fending off flirtatious neighbours?

‘Stella’s tired. Mrs Pendleton has offered her motorcar to take us home.’

‘Ooh, exciting! Is there space for me, do you think?’

Jed shook his head. ‘She offered the ride to me and Stella. I wouldn’t dare take anyone else. The word’ll get back to her and she’ll think I was taking advantage. Sorry, Maggie.’

‘Hmph. I suppose I’ll have to walk, then.’ Maggie turned on her heel and marched away, leaving Jed breathing a sigh of relief. They had history, he and Maggie. Way back when they were young, just in their twenties, he’d stepped out with her once or twice. There’d been a couple of bus rides into Penrith, and visits to the cinema. A dance or two, and a Christmas kiss under the mistletoe in the Lost Sheep. But then he’d met Edie and had fallen head over heels in love with her – her easy laugh, her endless optimism and kindness, her soft grey eyes and capable hands. He’d had to let Maggie down gently, and although she’d come to his and Edie’s wedding and congratulated them, she’d never married herself, and he’d always suspected she had never quite got over losing him. Well, it couldn’t be helped. A man couldn’t influence who he fell in love with, could he? And he would never regret a second of the time he’d spent with Edie.

He sat beside Stella, inside the lych-gate, and took her hand. ‘We’ll be all right, lass. You, me and little Jessie. We’ve still got each other, and your ma’ll be watching over us from up above, like that skylark you saw.’

She turned to him and offered up a sad smile. His heart melted. She was the spit of Edie, and like her in temperament too. Jessie, in contrast, was shaping up to be more like him – impetuous, contrary, and a bit of a handful at two years old. But Stella was a darling, a good girl, a real asset. Just as well. She’d had to grow up quickly when her mother became ill, and now she’d have even more responsibilities if they were to stay together as a family, the three of them. He sighed. The future would be tough, and he had no idea how they would manage. His only consolation was that his love for his daughters was surely powerful enough to pull them through.

A crunch of gravel made him look up. The Bentley was back. The chauffeur remained sitting in the driving seat, gesturing to Jed to open the back door. He’d have got out and opened it for Mrs Pendleton, Jed thought wryly, but he was grateful enough that Stella was not having to walk. He tugged open the door, and Stella climbed in first, then he followed. Inside, the car smelt of leather and polish. If it hadn’t been the day of Edie’s funeral Jed felt he’d have enjoyed the experience. It wasn’t every day you had a ride in an expensive motorcar like this one. Usually his transport would be the bus to Penrith or a ride in a trailer towed by one of his neighbours’ tractors.

The road route back to Brackendale took them to the bottom end of the Glydesdale valley, following the stream, before turning northwards in the direction of Penrith. A little further along there was a left turn, heading westwards into the Brackendale valley. This was the new road, built by the waterworks to allow easy access for the construction traffic. It was smoothly surfaced and wide enough for two tipper trucks to pass each other. A far cry, Jed thought, from the rutted old track, more potholes than tarmac, that they’d had to use before. The new road continued past the dam worksite and as far as Brackendale Green, along the side of the valley. It marked, Jed supposed, where the new waterline was expected to be, once the valley was flooded.

‘Pa, look,’ Stella said, tugging his arm and pointing out of the window. The site of the dam had come into view as they’d rounded a corner. It had been a few months since he’d last come this way, and it was clear much progress had been made. Whereas before there’d been just a scar across the valley where the land had been cleared and dug out to house the huge foundations for the dam, now there were massive concrete structures rising up. Fifty feet wide at the base, and tapering towards the top. The highest sections were over fifty feet high but Jed had heard the dam would be up to a hundred feet above the level of the Bere beck that flowed through the valley.

‘It’s coming on,’ he said to Stella.

‘What will happen when the dam goes all the way across?’ she asked, turning to him with her wide, sad eyes. So like Edie’s, he thought, with a stab of pain at her loss.

‘Then the water will rise up on the upper side, and the little lake we already have will grow very much bigger, lass. And they’ll control how much water flows through into the pipes that will lead all the way to Manchester.’

‘What about our village? Will the water reach there?’

‘It will eventually, lass.’

‘What will we do?’

Was this really the best time for such a conversation? On the very day they’d buried her poor mother? Jed sighed. She had to know, sooner or later. ‘We’ll have to go and live somewhere else. Everyone will.’

‘Where?’

‘That I don’t know, lass. I really don’t know.’

Chapter 3 (#ulink_10971b0f-efc3-5a2a-80be-2d49eb4153c9)

LAURA (#ulink_10971b0f-efc3-5a2a-80be-2d49eb4153c9)

It was late afternoon by the time Laura arrived at her destination. She’d researched on the internet for campsites near to Bereswater, the lake that occupied the valley where Brackendale Green had once stood. There was one in the next valley, Glydesdale, and she’d been able to book a pitch online. And finally, after a long and tedious drive up the M6, here she was, with a full week ahead to climb some mountains, relax in the sunshine, have a long hard think about her future and of course, explore Gran’s birthplace. The weather forecast predicted that the dry, sunny weather would continue for a few more days yet.

The scenery, as she’d left the main roads, entered the Lake District and driven along the narrow twisting road that led into Glydesdale, had been breathtaking. Dry stone walls lined the lane, beyond which were fields in which the year’s lambs, now four or five months old, still bleated for their mothers and tried to suckle. A pretty stream ran along the valley bottom. Either side of the valley, beyond the fertile low-lying fields, were the slopes of the mountains, or ‘fells’ as they were more usually known in this part of the country. Bracken gave way to heather higher up, then craggy rocks. Here and there scree runs tumbled down the mountainsides. A waterfall, now only a trickle after the prolonged drought, made its way down over rocks and through a ravine lined with stumpy trees. It was beautiful. Laura couldn’t wait to get her walking boots on, her rucksack on her back, and start exploring. She felt as though the countryside was already working wonders and washing away her problems. What a great idea of Gran’s it had been, to have a holiday now before the good weather ended!

At the campsite she parked outside the wooden building which served as an office and small shop, and went inside to check in.

‘You’ve come at a good time,’ the girl who was manning the desk and cash register told her. ‘The kids go back to school this week, so all the families left at the weekend. We’re half empty so you can pick your pitch. Down beside the stream is nice, and there are a few trees for shade if it gets too hot.’

‘Sounds lovely!’ Laura said, accepting a map of the campsite which showed where the amenities – shower block, toilets, launderette – were sited.

‘We open the shop at eight each morning, and there’ll be fresh bread and croissants, plus bacon butties, coffee and tea if you don’t want to cook your own breakfast. We can do packed lunches too, if you’re off up the fells.’

Laura grinned. ‘Perfect. What more could a camper want?’

The girl smiled back. ‘We aim to please. A detailed weather forecast for the next day is pinned on the door each afternoon. Worth checking before you set out, but I can tell you there’s no danger of rain until at least Friday. So, there’s your tag to hang on your tent, and a sticker for your car windscreen. As I said, take any pitch you want.’

‘Thanks so much. I think I’m going to enjoy camping here,’ Laura said. She turned to leave, and almost bumped into a sandy-haired man who she hadn’t noticed was standing behind her, waiting to pay for a pint of milk and a pack of sausages. ‘Whoops! Sorry.’

‘No problem,’ he said. ‘You missed standing on my foot, so that’s OK.’ He smiled, an attractive, slightly lopsided smile that made his grey eyes crinkle at the edges. ‘You’ve just arrived? I can recommend those pitches beside the river. Perfect to cool your feet after a hot day walking in the hills.’

‘Thanks, I’ll go and check it out,’ Laura replied, as she left the office.

‘Enjoy your stay.’ He waved, then turned to pay for his shopping.

That bloke was right, Laura thought, as she drove slowly around the campsite, checking out the available pitches. The area beside the stream was definitely the most inviting, and there was a large pitch free beside a spreading oak tree. She pulled out her compass to check which way was east. Always good to have some shade in the mornings, or the heat of the morning sun could drive you out of your tent before you’d had a chance to have a decent lie-in. Looked like the tree would do the job, so she parked her car, opened the boot and began setting up camp.

The tent was brand new. As was her sleeping bag. In the end, she’d avoided a possible confrontation with Stuart by treating herself to new kit. For summer camping, cheap festival gear was good enough. It only took her half an hour to get everything set up, and her little camping gas stove (also new) up and running to make a cup of tea. She unfolded a deckchair she’d found in Gran’s shed, set it in the sunshine and sat down to wait for her pot to boil. Behind her, the little stream was chuckling to itself like a giggling child as it bubbled over stones down the valley. Ahead of her was the most amazing view, framed by branches of the oak, across the valley to the fells. She’d need to pull out her detailed map of the area to work out which ones they were, but already she could see an enticing-looking path zigzagging its way up one of them. But that would have to wait – tomorrow she wanted to go to Brackendale. She sighed with contentment. It was shaping up to be a very good week.

It was years since she’d last been camping. Stuart’s style was more suited to package holidays in Ibiza – sunshine, booze and partying. She’d gone along with it because she loved him and loved being with him. And they’d had fun. At least, she’d thought it was fun at the time. Looking back, she wondered why she’d never pushed for them to try a different type of holiday. One that didn’t involve daily hangovers. Would he have agreed? Who knew? If he had, it might have left them with a healthier relationship – one in which they were more of a partnership. She could see it more clearly now they’d been apart a few months – theirs had not been a relationship of equals. She’d always done whatever Stuart wanted, as though she was his pet lapdog. Perhaps it was as well it had finished the way it had, allowing no way back, although she did miss the intimacy. She missed having a best friend, too, and knew it would be ages before she could trust anyone fully again.

She spent the evening lounging outside her tent, cooking a simple meal of pasta with grated cheese, which tasted amazing when accompanied by a glass of Pinot Noir. She read books until the sun went down behind the mountains, took an evening walk around the campsite, called Gran to check she was all right, then put herself to bed early, just as it was getting dark, tired after the long drive north. Maybe the Lake District was already working its magic, as she managed to doze off without crying herself to sleep.

The following morning dawned bright and clear, but despite the shade of the oak the inside of the little tent was stifling hot by eight o’clock. Laura dressed quickly in shorts and a T-shirt, and bought coffee and a bacon butty from the campsite shop. As she ate them she studied her map, and realised the zigzag path she could see going up the fells on the other side of the valley led into Brackendale. It was marked on the map as the Old Corpse Road. ‘Interesting name for a footpath,’ she muttered to herself, making a mental note to google it at the next opportunity. It looked to be about three kilometres to walk, with four hundred metres of ascent, from the campsite to Brackendale, and on a day like this why not walk it rather than drive around? She packed her rucksack with a bottle of water, a hastily made sandwich and some snacks, donned her walking boots and set off.

To begin with her route took her along the lane going further up the valley, past a church with its overgrown graveyard, full of lopsided lichen-clad gravestones. A little further on, a public footpath sign pointed the way to ‘Brackendale via Old Corpse Road’.

The track wound its way between acres of waist-high dried-out bracken, then began the zigzags she could see from the campsite, where heather and outcrops of rock flanked the path. As she climbed higher the temperature seemed to increase as there was no shade and very little breeze. The land smelt dry and dusty. She sat to rest on a flat-topped rock that was just to the side of the path, wondering whether it was natural or had been placed there for some reason. She took a gulp of water from her bottle, wishing she’d brought more than one as she was not at the top of this climb and it was half gone already.

As she walked she found herself thinking about her clients, and wondering how they were getting on without her. Of course the agency would be sending alternative carers, but some clients always told her how much they looked forward to Laura’s visits. Like dear old Bert Williamson, who always had a joke ready for her every time she came. As often as not it’d be one she’d heard before – usually from Bert himself the previous week, as his memory was not the best – but she’d chuckle anyway and tell him he was such a card, as she got him washed, dressed and ready for the day. And lovely Ada, where her morning calls would always include helping the old lady pick out earrings and a necklace to match her outfit for the day. Her job paid poorly but it was so meaningful and worthwhile, and people like Bert and Ada made it enjoyable. The worst moments were when she arrived at a client’s home to find them very sick, and she’d need to call an ambulance and send them off to hospital, knowing there was a strong chance they wouldn’t come home again. Her training had taught her not to get too involved with clients, but sometimes she couldn’t help it.

At last the gradient levelled out and she found herself crossing a rounded hilltop, land that might be boggy in a wet season but currently was formed of hardened mud, with the path winding its way through. The view changed – now she could see a new range of higher hills that must be on the far side of Brackendale looming on the horizon. Eventually the path began to lose height and then suddenly, as it turned a corner, there it was – the whole valley of Brackendale laid out before her. She gasped at the sight. Away over to her right she could just see the dam, and a small lake, not much more than a pond, this side of it. A huge expanse of muddy lake-bed covered the rest of the valley floor, just as she’d seen on the TV news report. Around the edges was a fringe of pebbles, as though normally the reservoir had a bit of pebble beach. The valley sides were lined with trees. She squinted, trying to pick out the ruins of the village amongst the dried mud, but from this height it was difficult to be sure what she was seeing. It would be nice to have a companion, someone to talk to about what they could see, but of course there was no one. Stuart would never have come on this type of holiday. Neither would Martine. With a jolt Laura realised those two were probably well matched after all. She sniffed back the tears that threatened to fall, pushed all thoughts of Stuart out of her mind and picked up her pace on the descent, desperate to get down to the lakeside and start exploring.

The bottom of the track led into a car park, after crossing a stile. There were a number of cars parked there, presumably either hikers or tourists who’d come to see the empty reservoir. An information board beside the car park gave a few sketchy details about the history of the valley and the building of the dam, complete with a grainy photo of what the village of Brackendale Green looked like in the early 1930s. Laura peered closely at this, noting the church, a pub, a bridge over a stream, a group of cottages tightly packed in what was presumably the village centre, and then some more scattered cottages and farm buildings further out. She lifted her head to look at the dried lake-bed, where she could now clearly see the low, broken walls that the TV reporter had pointed out. She tried to map buildings shown on the photo against the ruins but from where she was standing it wasn’t possible. Time to venture onto the dried mud and explore it properly.

She crossed the car park, walked a little way along the lane that would normally hug the shores of the lake, then when she was near to some of the ruins she left the road, crossed the band of pebbles and tentatively set foot on the grey mud. It was rock solid, criss-crossed with cracks from the weeks of sunshine, and smelt a little of rotting vegetation, as any aquatic plants the lake had hosted had long since perished in the dry heat. More confident now that she’d discovered how firm the mud’s surface was, she set out across it to the nearest piece of wall. It was about waist high, with mounds of rubble inside, and a clear doorway. On the opposite side to the door were the remains of a window, complete with some green-glazed tiles on the inside ledge. Laura entered the cottage, and immediately felt the surface beneath her feet change, as though there were only a couple of inches of dried mud on top of a more solid base – stone flags, she presumed.

The next cottage felt different underfoot. She knelt down and rubbed at the dried mud with her fingertips, discovering wooden floorboards beneath. Presumably pretty rotten after eighty years underwater, so she left that cottage quickly.

There was someone else crossing the lake-bed towards the ruins. As he approached she recognised the sandy-haired man from the campsite. He was heading directly for her, and raised a hand in greeting.

‘Amazing, isn’t it?’ she said, when he was within earshot.

He smiled, and pushed a hand through his hair. ‘Certainly is. To think people once lived here, walked up this street, went into their homes or shops or pubs.’ He turned and gazed across the remains of the village, then pulled a bottle of water out of his rucksack and offered it to her. ‘I can’t believe how hot it is, either.’

‘I know. Boiling. But I’ve got my own water, thanks.’

They began walking along what must once have been the main street through the village, with remains of buildings tightly packed on both sides. ‘I’m Tom, by the way,’ he said, holding out his hand for her to shake.

‘Laura. Pleased to meet you.’

‘So did you come here especially to see the remains of the village?’ he asked.

She nodded. ‘Well, yes, but also to have a holiday and do some walking. I adore the Lake District.’

‘Me too. I’ve been here a week already, climbing with a mate. He’s a teacher so he had to leave at the weekend and go back to work today. But the weather’s so amazing I decided to stay for a few more days on my own as I’m not due back in the office till next week.’ He stopped and once more looked around at the ruins, then spoke quietly, almost to himself. ‘I wonder which one it was.’

‘Sorry?’

He shook his head slightly as though coming out of a daydream. ‘Sorry. Just musing. I’ve researched my family tree, you see, and one branch of my ancestors came from here.’

‘Wow, that’s amazing! My grandmother was born here, too. That’s one reason why I came. We saw an item on the news about it, and she told me then she was born here. I hadn’t known. She’s a bit too frail to make the trip up here herself, though.’

‘Do you know which house she lived in?’

Laura shook her head. ‘No, I’ve no idea.’ She looked up at him and smiled. ‘Weird to think our ancestors might have known each other. Who was it in your family tree who lived here? How long ago?’

‘My dad’s maternal grandmother. That’s my great-grandmother – she was the last of the family to live here. Her daughter, my grandmother, was born elsewhere, during the war. My great-grandmother married, had her daughter and was widowed all during the war years. Your grandmother must be quite a bit older than mine, if she was born here.’

‘She’s over ninety.’

‘A great age. Does she have any memories of being here?’

‘Yes, some, I think, though she hasn’t spoken much about it.’

‘You should ask her.’

‘Yes. I could ask her too for names of anyone she remembers from those days. But she was only about ten or eleven when the village was abandoned so she might not remember anyone. What was your great-grandmother’s name?’

‘Margaret Earnshaw.’

‘My gran is Stella Braithwaite. But that’s her married name. I’m not sure what her maiden name was. I need to make a list of all these questions to ask her!’ Laura grinned. It was great to have someone to talk to about all this, and Tom certainly seemed interested.

‘It’s fabulous that she’s still around to ask. My grandmother died a few years back so most of what I know is from online research. In fact, it was when she was diagnosed with cancer that I began researching my family tree. I recorded her speaking about the past, everything she could remember, to give me a start. But she never lived here, and she said her mother, Margaret – though everyone knew her as Maggie – never spoke about her early life.’ Tom sighed. ‘So I’ve no one to ask. The people who lived here are all just names and dates to me.’

They’d reached the end of the main village street, and come to a small stone bridge. It looked incongruous sitting there in the middle of the lake-bed, a bridge crossing nothing. ‘This must have been the footbridge over the stream that flowed through the valley to the original small lake. It’s marked on the old maps of the village,’ Tom said. ‘Amazing that it’s still in such good condition.’ He ran a hand over the stonework. He was right – the mortar between the stones appeared solid, the surface of the bridge looked as though a quick sweep would restore it to perfect condition.

They turned and looked back at the village. ‘I really want to know more about it now,’ said Laura. ‘Coming here has made it all very real. I can’t wait to ask Gran to tell me more about it.’

‘Why don’t you ask her now? You could ring her, perhaps? Maybe she could describe whereabouts her house was. And I’d love to know if she remembers any Earnshaws.’

Laura looked at her watch. Monday, midday. Gran would be at home, pottering around the house, perhaps thinking about making herself a light lunch. She had no lunchtime carer visit, so unless one of her many friends had come to call, she’d be on her own, and hopefully the phone would be within reach. ‘OK, I’ll try her now.’ She pulled out her mobile and punched in Gran’s number. Thankfully, standing out here in the middle of the valley there was some reception. She felt a quiver of excitement as she waited for Stella to answer. Would she be able to pick out the right house? What a shame Gran was not fit enough to be able to come here herself.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_05daa272-18e1-56f0-bf05-b251b362f9c9)

JED (#ulink_05daa272-18e1-56f0-bf05-b251b362f9c9)

‘Stella, watch Jessie for me, will you?’ Jed called from the workshop, where he was trying to file down a piece of metal to make a replacement bracket for the seat of old Sam Wrightson’s tractor. Jessie, now that she could walk, was becoming difficult to look after when he was trying to work. While she’d been a baby he could put her in the playpen he’d made from chicken mesh, with a few toys, and she’d amuse herself. She’d always seemed happy enough as long as she could see him. But now, she refused to go in the playpen and if he put her in it she simply lifted one side of it up and crawled out underneath, giggling in that infectious yet infuriating way she had. And then she’d stand too close while he was welding, or start lifting tools off his bench to play with, or try to play hide-and-seek under the workbench. It was really not a suitable place for a small child to be.

‘Yes, Pa, coming.’ Stella was just home from school, thank goodness, and if she could keep an eye on Jessie for a couple of hours Jed would be able to get on with some work, until the light failed. He had electric light in the workshop, but was short of oil for the generator – what little he had needed to be conserved.

‘Come on, Jessie. Let’s go and look for tadpoles. Pa, we’ll be down by the lake. I won’t let Jessie get wet.’ Stella retrieved Jessie from the pile of oily dust sheets she’d been hiding in, and took her by the hand.

‘Be back in time for tea,’ Jed said.

‘All right.’ Stella and Jessie left the workshop, and Jed heaved a sigh of relief. He could get on uninterrupted at last. And he needed to. If he didn’t get some of his backlog of jobs finished he wouldn’t be paid. That would mean no more oil for the generator, no new clothes for Stella who was rapidly growing out of her school uniform, and no food on the table. Life was indeed hard. He still missed Edie with a pain that felt like an iron fist punching him in the gut. He’d promised her the girls would want for nothing. He would provide for them, no matter what it took.

‘Jed? Hello! I saw Stella go out with your little one, so I guessed you’d be on your own now. Let me make you some tea – I’m sure it’s about time you sat down for a rest.’ It was Maggie.

Jed sighed, and put down his tools. ‘I could do with a cuppa, it’s true, but I’ve not the time to sit down to drink it.’

‘Oh, you will. It’ll only be a few minutes. I’ll pop into your kitchen and make the tea then, shall I?’ Maggie didn’t wait for an answer, but went through to his cottage straight away. He continued working while she was there, feeling vaguely uncomfortable about her being in his home on her own, poking about in what he still thought of as Edie’s kitchen. But, he berated himself, she was only being kind and neighbourly. And he could certainly do with the tea.

She was back a minute later with a steaming mug, and a slice of fruit cake. He pressed his lips together. That cake had been a gift from Mrs Perkins at the village shop, and he’d been saving it for the girls’ tea. But if he told Maggie that, it would be admitting how much he was struggling.

‘Thank you.’ He took the mug and sat on a stool beside his workbench.

Maggie pulled a battered chair forward, brushed it off, and sat tentatively on the edge of it. ‘Any time. I’m here for you, you know. Anything I can do to help.’

Take Jessie for a few hours each day, Jed thought, but he’d tried that once when Edie was sick and it hadn’t worked out. Jessie hadn’t taken to Maggie, and she’d ended up bringing the tantrumming child back to him after only an hour, saying she was uncontrollable. ‘Thanks, Maggie.’

She smiled, patted her hair, and pulled her chair a little nearer him. ‘Remember, any time you need anything, anything at all, you know where I am.’

‘Thanks,’ said, again. ‘Actually, Maggie . . .’

‘Yes?’

‘I just need some time to get on with my work. Stella’s taken Jessie out for an hour or so, and I need to get this piece finished for Sam Wrightson’s tractor seat, and at least one of those bicycle repairs done, and the knife-sharpening for Mrs Perkins, before they come back.’

‘But it’s already five o’clock. Surely it’s time to stop work for the day? We could go across to the Lost Sheep for a drink while they’re out.’

He shook his head. ‘No, Maggie, I really must get this work done now.’

‘Oh, well. Later, perhaps? When the little one’s in bed? Your Stella can babysit.’

‘I might be in the Sheep for a pint later,’ he said. It was Friday after all, and it had been a tough week. With Stella home all weekend he could catch up on his work then.

Maggie smiled wolfishly, and once more patted her neatly waved blonde hair. ‘I shall see you there, then,’ she said. She stood up, brushed down the back of her skirt, and leaned over Jed to kiss his cheek. Her blouse had a couple of buttons undone, and he averted his eyes to avoid seeing straight down the front of it.

‘You’re blushing!’ she said, with delight. ‘It was only a peck on the cheek, you silly man!’ She flounced out of the workshop, stopping at the door to waggle her fingers at him. ‘See you later!’

He let out a huge sigh. Well, at least now he could get on at last. He finished his tea, took the uneaten slice of cake back through to the cottage, and continued working until Stella came home with a tired but happy Jessie.

After tea, when Jessie was fast asleep and Stella ready for bed but snuggled with a book beside the kitchen stove, Jed fetched his cap and jacket. He was tired, but a pint would help him sleep. Too often these days he lay awake for hours fretting over the future. ‘I’ll be off to the pub then, lass. You know where I am if you need me.’ The pub was less than fifty yards up the lane from the cottage, so he had no qualms about leaving the girls on their own.

‘We’ll be fine, Pa. I’ll be off to bed at the end of this chapter anyway.’ Stella yawned, then reached up to kiss his cheek. ‘Night-night.’

He gave her a squeeze and kissed the top of her head. What a good daughter he had! She’d taken on so many responsibilities since Edie’s death, and yet nothing seemed to faze her. She was so grown up, and yet still able to play as a child should, with Jessie or her schoolmates.

Before going to the pub he walked to the other end of the lane, where, on the edge of the village, was his father’s tiny cottage. He tapped on the door but did not wait for an answer – Isaac was a little deaf and more often than not, asleep beside his fireplace. The door led straight from the lane into the front room, which was both kitchen and sitting room. Behind it, at the back of the cottage, was a bedroom, and outside in the yard, a privy.

As usual, Isaac was sitting in his armchair, head tilted back, snoring loudly when Jed entered. He gently shook the old man awake, then banked up the fire.

‘All right there, Pa? Have you had your dinner?’

‘Aye, nice bit of lamb stew. Maggie brought it, bless her.’

Jed raised his eyebrows at this. Was this another of Maggie’s attempts to get into his good books, or just an example of neighbourly kindness to an old man? ‘Good of her. Was it nice?’

‘Aye. Could have done with a pudding, after. You’re not looking after me enough, lad. All day here, on my own, and only for Maggie coming in I’d be starving by now.’

‘I’m here now, aren’t I? And if you hadn’t eaten already I’d have fetched you something.’

Isaac grunted. ‘Nowt but a crust of bread and cold mutton, no doubt. Ah well, ’tis the lot of the old to be neglected. Suppose you’re off to the pub now. Never mind me. I’ll sit here a while and smoke my pipe afore I haul myself into my bed.’

Jed ignored the grumbling. Isaac had been a long-time widower, and as he’d aged he’d become more and more grumpy. No matter what people did for him, he’d always complain it wasn’t enough. Jed finished banking up the fire, made his father a cup of tea and fetched him his pipe and tobacco. ‘There, now. You have all you need. I’ll look in on you tomorrow – I’ll bring little Jessie up to see you at lunchtime.’

Isaac smiled toothlessly. ‘Ah, the little pet. Yes, you bring her. She loves her old grandpa, does that one. Well, if the Lord spares me till the morning, I’ll have her bonny face to look forward to.’

At least that had cheered Isaac up a little. And Jessie did seem to like him – she’d always climb onto the old man’s lap and cuddle up, stroking his beard. Jed checked there was nothing else he could do, then bade his farewell. Time to get himself on the outside of a good pint, he thought. He knew that sooner rather than later, Isaac would have to give up living alone in his little cottage. He’d have to come to live with Jed and the girls. They could turn the little parlour, rarely used since Edie’s demise, into a bedroom, as Isaac would not be able to manage the stairs. Then Jed would be at his father’s beck and call, and there’d be even fewer opportunities to get his work done. But Isaac was his father, and he’d take care of him, no matter what. God, how he needed that pint now!

The Lost Sheep was busy that evening. Good, Jed thought. Less chance of Maggie cornering him, if there were plenty of other people about. He was more than happy to spend time with her in a group, but on her own she was just too pushy for his liking. It was only a month since Edie had been buried. It wasn’t right to be seen with another woman. Especially one that he wasn’t even the slightest bit interested in.

Sam Wrightson was standing near the bar, and Jed went straight over to join him, ordering himself a pint of ale from the landlord, John Teesdale. ‘Evening, Sam. Busy tonight, isn’t it?’

‘Aye. Some of the navvies from the dam-building are in. That lot, over there –’ Sam jerked his head backwards to indicate a group of men who’d clearly already had a few pints. ‘You fixed my tractor seat yet?’

‘Yes, the part’s all ready for you. Bring your tractor to me tomorrow and I’ll fit it for you.’

‘Good. Fed up of that seat swivelling round. Tricky to drive forward when you find yourself facing backwards. Well, cheers.’ Sam held his glass aloft. Jed chinked his own against it, then took a long pull of it. In the corner, the dam-workmen were beginning to sing raucously, one of them standing on a stool to conduct the others.

‘They’re having a fine time,’ Jed commented.

‘Aye. Teesdale’s keeping an eye on them, though. Word is they caused trouble the other night, up at the King’s Head. Landlord there threw them out and banned them for a fortnight. That’s why they’ve come down here.’ Sam eyed the gang warily. ‘They’ve a cheek, though, turning up here, when it’s their work that’s going to be the death of our village.’

‘They’re just doing their job,’ Jed replied.

‘That’s as maybe, but they should do their drinking elsewhere.’

Jed nodded vaguely. ‘Aye, maybe so.’

Sam wasn’t letting go of his theme. ‘Pub feels different with them here, too. Doesn’t feel right. Listen to that singing, if you can call it that. Caterwauling, more like. Not what we normally have in the Lost Sheep.’

‘Everything’s changing, Sam. We’ve only to get used to it. ’Tis all we can do.’

Sam snorted. ‘I’ll not get used to it. I’ll be moved out of Brackendale afore I’m used to it.’

‘You got somewhere to go?’ Jed raised his eyebrows. People were beginning to move out, and he knew he should start looking for jobs and accommodation elsewhere, but his heart hadn’t been in it. Not since Edie died.

‘Fingers in pies, Jed. Fingers in pies. Nothing definite.’ Sam sighed and looked around him. ‘Just hope Teesdale stays till the end, and keeps this place open.’ He stepped smartly sideways to avoid being jostled by one of the dam-workers. ‘Hope he bans this lot before then, any road.’