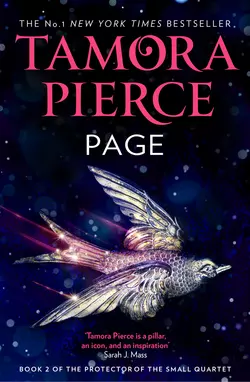

Page

Tamora Pierce

When they say you will fail … fail to listen. The adventure continues in book two of the New York Times bestselling series from the fantasy author who is a legend herself: TAMORA PIERCE. A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. WHEN THEY SAY YOU WILL FAIL… FAIL TO LISTEN. As the only female page in history to pass the first year of training to become a knight, Keladry of Mindelan is a force to be reckoned with. But Kel’s battle to prove herself isn’t over. She must masterher paralyzing vertigo, the gruelling training schedule and the dark machinations of those who would rather she fail. But in times of danger, Kel shines. The kingdom’s nobles are beginning to wonder if she can succeed far beyond what they imagined. And those who hate the idea of a female knight are getting desperate – they will doanything to halt her journey. A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. In a landmark quartet published years before it’s time, Kel must prove herself twice as good as her male peers just to be thought equal. A series that touches on questions of courage, friendship, a humane perspective – told against a backdrop of a magical, action-packed fantasy adventure. ‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones’Washington Post

PAGE

BOOK 2 OF THE PROTECTOR OF THE SMALL QUARTET

Tamora Pierce

Copyright (#ulink_10d4a451-8590-563f-9d6c-0f9245c0320c)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Tamora Pierce 2000

Map copyright © Isidre Mones 2017

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Tamora Pierce asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008304225

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008304232

Version: 2019-06-25

PRAISE FOR TAMORA PIERCE (#ulink_a0b350c4-eb98-500e-b06b-0b22cc19ce4a)

‘Tamora Pierce didn’t just blaze a trail. Her heroines cut a swathe through the fantasy world with wit, strength, and savvy. Pierce is the real lioness, and we’re all just running to keep pace.’

LEIGH BARDUGO, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce creates epic worlds populated by girls and women of bravery, heart, and strength. Her work inspired a generation of writers and continues to inspire us.’

HOLLY BLACK, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce’s books shaped me not only as a young writer but also as a young woman. Her complex, unforgettable heroines and vibrant, intricate worlds blazed a trail for young adult fantasy – and I get to write what I love today because of the path she forged throughout her career. She is a pillar, an icon, and an inspiration.’

SARAH J. MAAS, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones.’

Washington Post

‘Tamora Pierce and her brilliant heroines didn’t just break down barriers; they smashed them with magical fire.’

KATHERINE ARDEN, author of The Bear and the Nightingale

Dedication (#ulink_45311471-b031-5aa9-a0e8-835ce01bf22b)

To Julia Niederhut Muche

Contents

Cover (#u1477ccd2-8221-5be9-800b-9e67c712781b)

Title Page (#u0dd913aa-5f61-5a29-b831-1af1e3f6b1e4)

Copyright (#u1e6a3442-e0c9-5491-ab66-33064a95d81e)

Praise for Tamora Pierce (#ued7565c9-9bc0-579f-a3c8-bbb61bd7209d)

Dedication (#u64a6a04f-d3aa-51b1-9551-8290ca4e4132)

Map (#ub275ee6a-019c-59b1-b2eb-23777c4777e9)

Autumn to Midwinter Festival, in the 14th year of the reign of Jonathan IV and Thayet, his Queen, 453 H.E. (Human Era) (#u7b28b5f4-d1c1-5477-820a-a3fbdb2e50ec)

Chapter 1: Page Keladry (#u098f1b23-166a-585d-bc46-232dc441a92b)

Chapter 2: Adjustments (#u3bc06e37-617a-57b0-bd18-dc210d51dbc1)

Chapter 3: Brawl (#u32d37d44-e8e0-5699-98fc-32ca05cff72a)

Chapter 4: Woman Talk (#u5f9a9a2f-c9c0-5660-9cd9-0e8696292089)

Chapter 5: Midwinter Service (#litres_trial_promo)

Late Winter–Early Spring 454 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6: More Changes (#litres_trial_promo)

Summer 454 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7: Hill Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8: Messages (#litres_trial_promo)

Autumn 454–Winter 455 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: Autumn Adjustments (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: The Squires Return (#litres_trial_promo)

Spring 455 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: Unpleasant Realities (#litres_trial_promo)

Summer 455–Spring 456 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: Vanishing Year (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: The Test (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Needle (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: Consequences (#litres_trial_promo)

Cast of Characters (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on for a Preview of Squire (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Tamora Pierce (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map (#ulink_4dafe858-f569-592c-a4ba-3b259f905ce6)

Autumn to Midwinter Festival, in the 14th year of the reign of Jonathan IV and Thayet, his Queen, 453 H.E. (Human Era) (#ulink_d2dea6e7-95d8-54a8-a554-af0cb72b4b8c)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_be573c86-ae69-5490-b029-e8e9717b314e)

PAGE KELADRY (#ulink_be573c86-ae69-5490-b029-e8e9717b314e)

Autumn that year was warm. Heat lay in a blanket over the basin of the River Olorun, where the capital of Tortall covered the banks. No breath of air stirred the pennants and flags on their poles. The river itself was a band of glass, without a breeze anywhere to ruffle its shining surface. Traffic in the city moved as if the air were thick honey. No one with sense cared to rush.

Behind the royal palace, eleven-year-old Keladry of Mindelan stared at the rising ground that led from the training yards to the pages’ wing and decided that she had no sense. She felt as if she’d let people beat her with mallets all morning. Surely it was too hot for her to do as she normally did – run up that hill to reach her rooms and bathe. After all, she would be the only one to know if she walked today.

Who would think this cursed harness would make such a difference? she wondered, reaching under her canvas practice coat to finger broad leather straps. At some point during her first year as page, she had learned that second-, third-, and fourth-years wore weighted harnesses, and that more weights were added every four months, but she had never considered it in terms of herself. Now she wished that she had donned something of the kind in the empty summer months, when she made the daily trek to the palace to keep up her training. If she had, she wouldn’t ache so much now.

She wiped her sleeve over her forehead. It’s not even like you’re carrying a lot of weight, she scolded herself. Eight little discs – maybe two pounds in lead. You trained last year and all summer with lead-weighted weapons, just to build your strength. This can’t be that different!

But it was. Hand-to-hand combat, staff work, archery, and riding took extra effort with two pounds of lead hanging on her shoulders, chest, and back. I’ve got to run, she told herself wearily. If I don’t move soon, I’ll be late to wash and late to lunch, and Lord Wyldon will give me punishment work. So heat or no, I have to go up that hill. I may as well run it.

She waited a moment more, steeling herself. She hated this run. That slowly rising ground was torture on her legs even last spring, when she’d been running it off and on for more than half a year.

No stranger, looking at her, would have thought this dishevelled girl was the sort to cause a storm of argument at court. She had a dreamer’s quiet hazel eyes, framed in long lashes, and plain brown hair that she wore cropped as short as a boy’s. Her nose was small and delicate, her skin tan and dusted with freckles. She was big for a girl of eleven, five feet three inches tall and solidly built. Only someone who looked closely at her calm face would detect a spark in her level gaze, and determination in her mouth and chin.

At last she groaned and began to trot up the hill. Her path took her behind the mews, the kennels, and the forges. Men and women in palace livery and servants’ garb waved as she ran past. A woman told some kennel workers, ‘Looka here – tol’ ya she’d be back!’

Kel smiled through pouring sweat. No one had thought that the old-fashioned training master would allow the first-known girl page in over a century to stay after her first year. When Lord Wyldon surprised the world and allowed Kel to stay, many had assumed Kel would ‘come to her senses’ and drop out over the summer holiday.

You’d think by now they’d know I won’t quit, she thought as she toiled on up the hill.

She was lurching when she reached the kitchen gardens, her shortcut to the pages’ wing. There she had to catch her breath. An upended bucket did for a seat. She inhaled the scents of marjoram, sage, and thyme, massaging her calf muscles. For the hundredth time she wished she could use the palace baths as the boys did, instead of having to go all the way to her room to wash.

‘Hi! You!’ cried a male voice from the direction of the kitchens. ‘Come back with those sausages!’

Kel got to her feet. A cook raced out of the kitchen, waving a meat cleaver. Empty beanpoles, stripped after the harvest, went flying as he crashed through them. Metal flashed as the cleaver chopped through the air. The man doubled back and ran on, plainly chasing something far smaller than he. Once he stumbled; once he dropped the cleaver. On he came, cursing.

The dog he pursued raced towards Kel. A string of fat sausages hung from his jaws. With a last burst of speed, the animal ducked behind Kel.

The cook charged them, cleaver raised. ‘I’ll kill you this time!’ he screeched, face crimson with fury.

Kel put her hands on her hips. ‘Me or the dog?’

‘Out of the way, page!’ he snarled, circling to her left. ‘He’s stolen his last meal!’

As she turned to keep herself between the man and his prey, Kel glanced behind her. The dog huddled by her seat, gobbling his catch.

‘Stop right there,’ Kel ordered the man.

‘Move, or I’ll report this to my lord Wyldon,’ he snapped. ‘I’ll get that mongrel good and proper!’

Kel gathered dog and sausages up in her arms. ‘You’ll do no such thing,’ she retorted. The dog, knowing what was important, continued to gorge.

‘You’ll hand that animal over now, my lad, if you know what’s right,’ the servant told her. ‘He’s naught but a thieving stray. He’s got to be stopped.’

‘With a meat cleaver?’ demanded Kel.

‘If that’s what it takes.’

‘No,’ she said flatly. ‘No killing. I’ll see to it the dog doesn’t steal from you.’

‘Sausages is worth money! Who’s to pay for them? Not me!’

Kel reached instinctively for her belt and sighed, impatient with herself. She didn’t wear her purse with training clothes. ‘Go to Salma Aynnar, in charge of the pages’ wing,’ she said loftily. ‘Tell her Keladry of Mindelan requests that she pay you the cost of these sausages from my pocket money. And you’d better not overcharge her,’ she added.

‘Kel … Oh, Mithros’s’ – he looked at her and changed what he’d been about to say – ‘shield. You’re the girl. Being soft-hearted will do you no good, mistress,’ he informed her. ‘Be sure I’ll get my money. And if I see that animal here again’ – he pointed at Kel’s armful – ‘I’ll chop him up for cat-meat, see if I won’t!’

He thrust his cleaver into his belt and stomped back to the kitchens, muttering. Kel adjusted her hold on the dog and his prize and headed for the pages’ wing. ‘We aren’t allowed pets, you know,’ she informed her passenger. ‘With my luck, all those sausages will make you sick, and I’ll have to clean it up.’ She passed through an open door into the cool stone halls of the palace. As she trotted along, she examined her armful.

The dog’s left ear was only a tatter. He was grey-white for the most part; black splotches adorned the end of his nose, his only whole ear, and his rump. The rest of him was scars, healing scrapes, and staring ribs. His sausages eaten, he peered up into her face with two small, black, triangular eyes and licked her. His tail, broken in two places and healed crookedly, beat her arm.

‘I am not your friend,’ Kel said as she reached her door. ‘I don’t even like you. Don’t get attached.’

She put him down, expecting him to flee. Instead, the dog sat, tail gently wagging. Kel put her key in the lock and whispered her name, releasing the magic locks that protected her from unwanted visitors. The year before, the boys had welcomed her by ruining her room and writing on her walls, making such protections necessary. While she had made friends among the pages since that time, there were still boys who would play mean tricks to make her leave.

She followed the dog into the two rooms that were her palace home and halted. Two servants awaited her before the hearth. One she knew well: Gower, the long-faced, gloomy man who cleaned her rooms and fetched hot water for washing and baths. The other was a short, plump, dark girl with crisp black hair worn neatly pinned in a bun. She was quite pretty, with huge brown eyes and full lips. Kel didn’t know her, but she was dressed like a servant in a dark skirt and a white blouse and apron. On that hot day she wore the sleeves long and buttoned at the wrist.

Kel waited, uncertain. Gower would surely report the dog to Salma. Kel was trying to decide how much to bribe him not to when he coughed and said, ‘Excuse me, Page Keladry, but I – we – that is …’ He shook his head, ignoring the dog, who sniffed at him. ‘Might I introduce my niece, Lalasa?’

The girl dipped a curtsy, glancing up at Kel with eyes as frightened as a cornered doe’s. She was just an inch taller than Kel, and only a few years older.

‘How do you do,’ Kel said politely. ‘Gower, I’m in a bit of a rush—’

‘A moment, Page Keladry,’ Gower replied. ‘Just a moment of your time.’

In the year he had waited on her, Gower had never asked for anything. Kel sat on her bed. ‘All right.’ She took off her practice jacket and harness as Gower talked.

His voice was as glum as if he described a funeral. ‘Lalasa is all alone but for me. I thought she might do well in the palace, and she might, one day, but …’

Kel looked at him under her fringe as she pulled at one of her boots. Suddenly Lalasa was there, her small hands firm around the heel and upper. She drew the boot off carefully.

‘She’s country-bred, not like these bold city girls,’ Gower explained. ‘When city girls act shy, well, men hereabouts think they want to be chased. Lalasa’s been … frightened.’ Lalasa did not meet Kel’s eyes as she removed the other boot and Kel’s stockings. ‘If it’s this way for her in the palace, the city would be worse,’ Gower went on. ‘I thought you might be looking to hire a maid.’

Kel blinked at Gower. Pages and squires were allowed to hire their own servants, but having them cost money. While Kel had a tidy sum placed with Salma, against the day that she might get enough free time to visit the markets, she wasn’t certain that she could afford a maid. She could write to her parents, who had remained in Corus to present two of Kel’s sisters at court that autumn. Kel wasn’t sure their budget, strained by the costs of formal dresses and the town house, held spare money for a daughter who would never bring them a bride-price.

She was about to explain all this when Lalasa turned her head to look back and up at her uncle. Kel saw a handspan of bruise under her left ear.

Suddenly Kel felt cold. Gently she took Lalasa’s right arm and drew it towards her, pushing the sleeve back. Bruises like fingerprints marked the inside of her forearm.

Lalasa refused to meet her eyes.

‘You should report this,’ Kel told Gower tightly. ‘This is not right.’

‘Some are nobles, miss,’ replied the man firmly. ‘We’re common. And upper servants? They’ll get us turned out.’

‘Then tell me the names and I’ll report them,’ she urged. ‘Salma would help, you know she would. So would Prince Roald.’

‘But his highness is not everywhere, and others will make our lives a misery,’ Gower replied. ‘In the end it’s Lalasa’s word against that of an upper servant or noble. It’s the way of the world, Page Keladry.’

Kel heard a whisper and bent down. ‘What did you say?’ she asked.

Lalasa met her eyes and glanced away. ‘They meant no harm, my lady.’

‘Grabbing you by the neck so hard it bruised? Of course they meant harm!’ snapped Kel.

Gower knelt. ‘Please, Lady Keladry,’ he said. ‘If she’s your maid, she’ll be safe. Your family is in great favour since they brought about the Yamani alliance.’

‘Please get up,’ Kel pleaded. No one had knelt to her since she was five. Then the tribute had been to her mother, standing beside her. ‘Gower, stop it!’ I’ve enough pocket money to pay her for the quarter, she thought hurriedly as she stood and tried to tug the man to his feet. If I explain to Mama and Papa, they’ll help, I know they will. ‘She’s hired, all right? Please stop that!’

He stared up into her face. ‘Your word on it?’

‘Yes, my word as a Mindelan.’

‘You won’t be sorry, miss,’ Gower told her as he rose. ‘Ever.’

Kel heard footsteps pound in the hall outside. ‘Oh, I’m going to be late!’ She scribbled a note for Salma, asking for an extra magicked key to Kel’s door, a silver noble as a month’s wages, and a spare cot for Lalasa to sleep on. She waved the note to dry the ink and gave it to Gower. ‘About the dog,’ she began.

‘What dog?’ Gower asked. He bowed; Lalasa curtsied. They left Kel to get ready for lunch.

Shaking her head at her folly – she didn’t need another complication in her life – Kel looked around until she saw the dog. He had jumped onto her bed to nap. ‘Good for you,’ she said, and stripped off the rest of her clothes.

A real bath was impossible. She wet her head and scrubbed her face and under her arms, mourning the proper soak that would have eased her aching muscles and made her feel less sticky. Perhaps she could visit the women’s baths that night, though it meant she’d have to take time from her after-supper exercises and classwork.

‘First day and I’m already behind,’ she remarked as she struggled into hose and tunic. ‘Oh, how splendid.’

Kel raced into the mess hall that served the pages and squires. All eyes turned towards her; some boys growled. Lunch was the pages’ most anticipated meal of the day after a morning’s rough-and-tumble in practice. Since none could eat until everyone had arrived, latecomers were never greeted pleasantly.

‘I suppose she thinks she’s one of us now, so she doesn’t have to be polite any more.’ Joren of Stone Mountain’s cultured voice was clear over the boys’ low mutter.

‘Page Keladry.’ Lord Wyldon of Cavall, the training master, could pitch his voice to carry through a battle or across the hall easily. Kel faced his table, placed on a dais at the front of the room, and bowed. ‘A knight who is tardy costs lives. Report to me when you have eaten.’

Kel bowed again and went to get her food.

‘Joren of Stone Mountain.’ Lord Wyldon’s level tone was the same as it had been for Kel. ‘Good manners are the hallmark of a true knight. You too will report once you have finished.’

Kel sighed. She and Joren had not got on during her first year as a probationer. She’d hoped that would change now that she was a true page. If Joren was to be punished on her account, she didn’t think it would improve his feelings about her.

Once her tray was filled, Kel looked around. Hands waved from a table at the back. She walked over and slid into place among her friends. Nealan of Queenscove poured her fruit juice while other boys passed the honey-pot and butter.

‘So, Keladry of Mindelan,’ said Neal, his slightly husky voice teasing, ‘not even a full day in your second year, and already you have punishment work lined up. Don’t leave it to the last minute, that’s what I say!’ He was a tall, lanky youth who wore his light brown hair combed back from a widow’s peak. His sharp-boned face was lit by green eyes that danced wickedly as he looked at her. He was sixteen, older than the other pages, but only in his second year. He had put aside a university career to become a knight. Neal had taught Kel to know the palace the year before, assisting her with classwork and cheering her worst moods with his tart humour. In return she tried to keep him out of trouble and made him eat his vegetables. It was a strange friendship, but a solid one.

‘Neal’s just disappointed because he thought he’d be first.’ The quiet remark had come from black-haired, black-eyed Seaver. He, too, was a second-year page.

‘I’m surprised he didn’t dump porridge on Lord Wyldon this morning, just to get the jump on the rest of us,’ joked Cleon. A big, red-headed youth, he was a fourth-year page. ‘Guess you’ll have to wait till next autumn, Neal.’ He smacked the top of Neal’s head gently, then went for seconds.

Kel looked to see who else had joined them. There was red-headed Merric of Hollyrose, whose temper was as quick as Cleon’s was slow; dark, handsome Faleron of King’s Reach, Merric’s cousin; and Esmond of Nicoline, whose normal powdering of freckles had thickened over the summer. All were her friends and members of the study group that had met in Neal’s room the previous year. With them were three new first-year pages, boys that Cleon, Neal, and Merric had chosen to sponsor. She wasn’t sure if they were friends or not. They would have been rude to refuse to sit with their sponsors, and thus with The Girl.

Only one of their company was missing, Prince Roald, but that was expected. Roald, now a fourth-year page, was always careful to slight no one. He had eaten with Kel, Neal, and their group the night before. Today he and the boy he had chosen to sponsor sat with some third-year pages.

Lunch passed quickly, the boys’ talk filling Kel’s ears. She had little to say. After living in the Yamani Islands for six years, she had picked up Yamani habits, including a reluctance to chatter or let emotions show. Someone had to listen to all that talk.

At last it was time to hand in her tableware and present herself to Lord Wyldon. Joren was already at the dais, waiting. Lord Wyldon always made it clear when he was ready to speak to his charges.

When Kel reached the dais, Joren stepped away from her. Kel sighed inwardly, her face Yamani-blank. Joren and his cronies had done their best to make her leave the year before. For her part, she had declared war on their hazing of the first-years beyond what she felt was reasonable. Interference with Joren and his clique had often turned into fist fights until her friends began to join her. At year’s end, there were enough of them to stop Joren’s crowd from hazing entirely. Over the summer Kel had let herself hope that Joren would give up now. Glancing at him, she realized her hopes were empty.

Three years older, Joren was just four inches taller than Kel and beautiful. His shoulder-length hair was so blond it was nearly white. It framed pale skin, rosy cheeks, and sky blue eyes set among long, fair lashes. He was one of the best pages in unarmed and weapons combat, although in Kel’s opinion he was heavy-handed with his horse.

Well, I’ve only one more year with him, Kel thought as Lord Wyldon finished cleaning his plate. After he takes his big examination, he’ll be a squire and gone most of the year.

Lord Wyldon drained his cup and set it down sharply. His dark eyes, as hard as flint, inspected first Joren, then Kel. Did he regret that he had allowed her to stay? Kel wondered for the thousandth time. Over the summer she had learned that last year the betting among the servants had been twenty to one against Lord Wyldon’s allowing her to enter her second year.

Now, looking at Wyldon’s hard, clean-shaven face, marred by a scar that stretched from his right eye into his close-cropped brown hair, she wondered why. If she smacked the training master’s bald crown would the answer pop out of his mouth? The thought nearly made her laugh aloud, the image was so funny, but her Yamani training held. Her lips didn’t quiver; her throat didn’t catch. She blessed the Yamanis as the training master drummed his fingers on the table.

‘Joren of Stone Mountain, I will have a two-page essay on good manners by Sunday evening,’ he said. As always, the words came reluctantly from his mouth, as if he felt he might be poorer by giving them away. ‘Keladry of Mindelan, for your lateness, you will labour in the pages’ armoury for one bell of time on Sunday afternoon.’ It was the standard punishment, no more and no less than he gave any other page for tardiness.

She bowed, just as Joren had. They were not permitted to argue.

‘You are both dismissed.’ Lord Wyldon picked up his documents. Joren made sure he beat Kel out of the mess hall. She let him have the lead, since he seemed to think it was important. Once he was out of her way, she ran back to her rooms. She needed to collect her books for the afternoon’s classwork.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_4399312d-ab23-5923-b304-7489fa858f91)

ADJUSTMENTS (#ulink_4399312d-ab23-5923-b304-7489fa858f91)

The dog was still asleep on her bed. He was not alone. While Kel had to keep the big shutters locked when she was out, the small pair over them were open in all weather so the sparrows that had adopted her could fly in and out. Three now perched on her coverlet, eyeing the dog with interest.

‘He isn’t staying,’ Kel told the small brown birds. The dog’s tail wagged, though he didn’t open his eyes.

One sparrow flew over and perched on her shoulder with a peep. It was the female who led the flock. A pale spot on top of her head had earned her the name Crown. Kel gave the bird a sunflower seed and gathered her books. Crown flew back to the bed to continue her inspection of the newcomer.

The palace animals were peculiar. They seemed wiser, in the human sense, than most other animals. The difference was caused by a young woman named Daine, the Wildmage, whose magic allowed her to communicate with animals. After she had talked to Kel’s gelding Peachblossom, the vicious horse allowed Kel to ride him without making her bleed for the privilege. Even Daine’s mere presence affected palace animals permanently. Three months before, Kel’s sparrows had led Kel and a troop of hunters to the lair of the giant, human-headed spider monsters called spidrens, though Daine had not been there to ask it of them.

Might Daine help with this dog? Kel wondered as she locked the door behind her.

Neal had been waiting in the corridor. He wrapped an arm around her shoulders. ‘Come, Mindelan,’ he said cheerfully, towing her towards the classroom wing. ‘While you were here riding your evil horse and bending a bow all summer, did you crack a single book?’

‘I helped the housekeeper with the accounts,’ retorted Kel, letting her friend tow her. ‘Did you bend a bow or ride a horse all summer?’

‘Had to,’ Neal said gloomily as they walked into their first class, reading and writing with the Mithran priest Yayin. ‘Our master at arms kept after me.’

She sat next to him. ‘We’ll make a knight of you yet, Queenscove.’

‘That’s what I’m afraid of,’ he retorted.

After class Kel returned to her rooms to find that life had suddenly improved. A full tub of hot water awaited her. She could take a real bath while the ugly dog looked on. As she soaked, Kel realized he, too, had been washed. His fine, short fur shone white between scars. He was still homely. His legs were a little bowed, supporting a barrel chest and thin hips. She had already noticed that twice-broken tail and his torn ear. His whole ear was sharp, pointed, and upright on a head shaped like a thick ax blade. That skull looked too big even for his sturdy neck, but the dog lifted it with pride.

‘You will never be a beauty,’ Kel informed him as she dried off. He wagged his absurd tail, as if she’d complimented him.

As she put on a brown shift, orange gown, and stockings – she always wore a dress to supper, in case anyone had forgotten that she was a girl – she noticed other welcome changes. Her desk had been neatened, her clothes pressed till not a single wrinkle was left. There was a bowl, empty even of crumbs, and a half-empty water dish: the girl Lalasa had washed and fed the dog. She had also found Kel’s store of seeds and filled the sparrows’ feed and water dishes. No bird droppings could be seen anywhere.

Someone pounded on her door. ‘Kel, come on!’ yelled Neal. ‘I’m hungry!’

When she opened the door, he poked his head inside. ‘The cooks say there’s ham and blueberry pies, since it’s the first day. I love blueberry pie – Mithros, that is the ugliest dog in the world.’ He stepped inside.

The dog trotted over to sniff him energetically. His crooked tail began to whip. He stood on his hind legs, braced his paws on Neal’s long thighs, and rooted at one of the youth’s pockets.

‘Caught me out, old man, didn’t you?’ asked Neal with a grin. He crouched, pulling a roll from his pocket, and gave it to the dog. It was gone in three bites. ‘You know we can’t have dogs,’ he reminded Kel, scratching the animal’s rump. ‘Mithros and Goddess, he is ugly.’

‘You said that already. I know I can’t have a dog. Neal, will the Wildmage take him?’

‘Daine? Of course,’ he replied. ‘She’s here – I saw her last night. Ask her after supper.’

‘Did you maybe want to go with me?’ she offered gingerly, afraid that she might cause Neal hurt by asking him along. Last year, he had introduced her to Daine when Kel had needed help with Peachblossom. Kel had seen that Neal was smitten with Daine, though she lived with the mage Numair Salmalín.

‘No,’ he told Kel nobly, and sighed. ‘It just tries my heart, to see her with that old man.’

Kel didn’t think Master Numair was so old, but she held her tongue. It did no good to argue with her lovestruck friend.

‘Kel, is Neal here?’ Merric stuck his head into the room. ‘Let’s be prompt to supper, shall we?’ His blue eyes widened. ‘That’s an ugly dog. You know we aren’t allowed pets.’

‘He goes to Daine tonight,’ Kel snapped. She thrust her friends from the room.

The king joined them for supper, as he had the year before. He ate with Lord Wyldon, then spoke to the pages and the few squires present about the importance of their studies. Kel watched and listened, her face Yamani-smooth. While she owed King Jonathan her duty and her service, she still wasn’t sure that she liked him. The king had allowed Lord Wyldon to put Kel on a year’s probation, something no other page had to endure. It had not been fair.

Suddenly she remembered something her father had said when the Yamani emperor ordered the execution not only of a band of robbers but of their women and children as well. ‘Rulers are seldom nice people, Kel,’ he’d remarked, his eyes sad. ‘Even good ones make choices that will hurt somebody.’

But what if I want him to be nice? she asked her father now as she watched her king smile at the eager boys. What if I want him to be fair?

‘You may want anything you like,’ her mother would have said. ‘That doesn’t mean you’ll get it.’

She smiled, but she kept it inside. She didn’t want the king to think she smiled at him.

As soon as the king had gone, Lord Wyldon called, ‘Keladry of Mindelan.’

Now what? thought Kel, halfway to the door. Has he heard about the dog? She went back to the training master’s table.

At least he didn’t keep her in suspense. ‘I understand you have taken a maid into your service,’ he remarked when she bowed.

Kel heaved an inner sigh of relief. ‘Yes, my lord.’

‘You are permitted to do so. However, a servant is a privilege, not a right, in the pages’ wing. In addition to your obligations to anyone in your service, you have obligations to me and to the palace.’ He regarded her levelly, toying with his knife. ‘She is not to involve herself physically with any page or squire. Her presence is not considered chaperonage for you. If there is a boy in your rooms, the door remains open. If she is ill, you will call and pay a healer. If she cannot read and write, you must teach her. If she misbehaves – is a thief, or lewd, or quarrelsome – you are liable. If she runs off, or stays away overnight without your permission, or disobeys you, do not ask palace guards or servants to find her or to help you to discipline her. That you must do yourself. Am I understood?’

Kel bowed. ‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Do your duty by her, and by us,’ Lord Wyldon said firmly. ‘You are dismissed.’

Kel left, finding that the halls had cleared while they talked. Most of the boys had vanished to begin their studies. Now Kel grabbed the dog and wrapped him in a blanket. ‘You keep still,’ she ordered as she carried him down the hall. The chambers where Daine lived were on the floor above the classrooms. The dog struggled on the narrow stair, finally poking his head out of the blanket. He then stopped fighting and gazed around with interest.

He was so bony, and so light! Couldn’t she keep him until he’d made up for the meals he had missed? Kel stopped on the landing to blink eyes that stung with tears. She knew she was being silly. Daine would feed him well, and she could heal his wounds. She could talk to him through her magic, and understand his replies. In a day or two the dog wouldn’t even remember Kel, he’d be so happy.

Thoroughly miserable and determined to hide it, Kel resumed her climb to the second floor. Walking slowly, she checked engraved name plates on the doors until she found the one that read: ‘Numair Salmalín, Veralidaine Sarrasri’. Wrestling a hand free of the blanket, Kel knocked.

The door opened. For a moment Kel was confused – she saw no one. A sharp whistle drew her gaze, and the dog’s, down to the floor. A young dragon, just two feet tall, was looking up at them. Her scales were dusty blue, her large, slit-pupilled eyes sky blue. She had draped her foot-long tail over a forepaw, like the train on a gown.

‘Aren’t you pretty,’ Kel said, admiring the small creature. She had seen the dragon Skysong, nicknamed Kitten, before, though at a distance. ‘Is Daine about?’ Dragons, even very young ones like Kitten, were supposed to be as intelligent as human beings.

The dragon tilted her slender muzzle and voiced a trill, then raised herself on tiptoe to inspect the dog. Kel knelt politely so the two could look at each other.

‘Keladry, hello!’ the Wildmage said cheerfully as she came to the door. ‘Welcome back!’ She was just three inches taller than Kel and slender, with tumbling smoky curls and grave, blue-grey eyes. She was dressed for rough work in breeches and shirt. Feathers clung to her hair. Her shirt was speckled with bird droppings and a streak of green slime that had to have come from a horse or donkey.

Kel got to her feet and smiled at Daine. ‘It’s good to be back, my lady.’

‘Who’s this?’ Daine stretched out her hands.

As Kel handed the dog over, she explained how she had met him. ‘My maid gave him a bath and some more food, so he doesn’t look as bad as he did,’ she finished. ‘But I can’t keep him. Would you? He likes you already.’ It was true; the dog was gleefully licking Daine’s face. When she set him down, he offered Kitten the same attention. Kitten stepped back with a shrill whistle. Scolded, the dog looked up at Kel and panted, tongue lolling.

‘I can try to keep him,’ Daine said, a doubtful look in her eyes. ‘He needs patching up, and something for worms. He’s barely more than a pup.’ She crouched beside the dog, running her hands over his scrawny frame. ‘He says his name is Jump.’

Kel backed up. ‘Name him as you like, my lady,’ she said, clenching her hands behind her back. She was not going to get upset over a dog she’d known less than half a day, and that dog going to the best home in the palace. ‘Thank you for taking him. If there’s anything I can do for you …’

Daine looked up at Kel. ‘You came almost every day this summer to ride Peachblossom and groom him,’ the Wildmage said quietly. ‘You bring him treats, and go easy on the rein, when last year at this time he could look forward to another brutal master or death. And Crown and her flock say that you always stopped by, though you knew Salma was looking after them. It is I who thank you, Keladry, for them. You treat animals as well as you treat human beings.’ She smiled. ‘I will try to keep Jump. If you find other animals in need, come to me.’

She offered her hand. Kel gripped it gently, mumbled something about appreciation, and fled. She had to stop in the stairwell to collect herself. Daine the Wildmage thought well of her!

Suddenly she heard a boy snap, ‘I don’t understand why I have to.’

She stiffened, her senses alert. Down the steps she went, cat-silent, until she was just around the corner from the ground floor landing.

‘It’s a page’s duty to obey.’ The perfectly chill voice belonged to Joren.

‘You first-year squirts need lessoning.’ That was Vinson of Genlith, one of Joren’s cronies. Kel shook out her shoulders, loosening them up.

‘This is a waste of time.’ The new voice belonged to Joren’s closest friend, Zahir ibn Alhaz. Zahir had stopped helping the others to haze new pages late last winter. ‘We have better things to do.’

‘What?’ demanded Vinson. ‘Are you afraid of the Lump and her friends?’ The Lump, or the Yamani Lump, was their nickname for Kel.

‘When you’re done with children’s games, Joren, let me know,’ Zahir said. Kel heard steps fade into the distance.

After a moment Joren said tightly, ‘Get to work, boy.’

‘But cleaning spilled ink I can’t even see—’ protested the voice Kel had first heard.

There was a thud. ‘We see it,’ drawled a new voice belonging to Garvey of Runnerspring. He and Vinson were Joren’s chief companions in hazing first-years.

Kel flexed her hands. They knew we didn’t expect them to start up the first night of training, she thought angrily. They knew we’d think they were as tired as the rest of us, so they sneaked around and found a victim.

She looked at her clothes. Since she hadn’t expected to patrol the halls in search of bullies, she hadn’t changed into shirt and breeches after supper. Fighting in a dress would be tricky. Rolling up her skirt, she gathered it at one side and knotted it. I don’t care if Oranie thinks that sashes make me look thick-waisted, Kel told herself. Oranie was her sharp-tongued second oldest sister. From now on, that’s what I wear.

Kel walked down the last few steps and into the ground floor hall. Ten yards away one of the new first-years, Owen of Jesslaw, lay on the floor. Vinson, Garvey, and Joren stood around him, leaving him nowhere to run.

They turned when they heard Kel’s sigh. ‘I hoped you’d all realized how stupid this is,’ she remarked coolly.

Joren smiled. ‘My day is complete,’ he said. The three older boys moved apart, then closed in on Kel.

Owen struggled to his feet. He was short and chubby, with plump hands and big feet. His tumble of brown curls looked as if somebody had yanked them. His grey eyes were set under brows shaped like question marks laid flat. Confused, he looked from Kel to the fourth-years.

‘I’m sure you have classwork,’ Kel told him, shifting to put a wall at her back. ‘Get to it. These boys’ – she put a world of scorn into the word – ‘and I have a debate to continue.’

Owen stayed where he was.

Maybe he doesn’t understand, Kel thought. She backed up, to draw the fight away from him.

Garvey came at Kel from the right, punching at her head. She slid away from his punch, grabbed his arm, pushed her right foot forward, and twisted to the left. Garvey went over her hip into Vinson, who’d attacked on her left. Joren, at the centre, came in fast as his friends hit the wall. Kel blocked Joren’s punch to her middle, but his blow was a feint; his left fist caught her right eye squarely. Kel scissored a leg up and out, slamming her right foot into Joren’s knee. Joren hissed and grabbed her hair. Someone else – Vinson – tackled her. Kel let his force throw her into Joren. Down the three of them went in a tumble. Joren let go of her hair, fighting to get out from under her and Vinson. Kel elbowed him in the belly and turned to thrust her other hand into Vinson’s face, encouraging him to get off her by pressing his closed eyes with her fingers.

Garvey waded in and grabbed the front of her gown to haul her to her feet. Owen – forgotten until that moment – struck him from behind. Down Garvey went, face-first, chubby Owen clinging monkey-like to his back as Kel rolled out of the way. Owen beat Garvey wildly about the head and shoulders with one hand.

Not much technique, Kel thought as she got to her knees, but he’s got plenty of heart.

Joren’s arm wrapped around her neck, cutting off her air. Vinson attacked her, cursing, his blows nearly as wild as Owen’s. Kel’s vision was going dark when hands pulled Joren’s arm away. Kel gasped for air. Dark breeches and white shirts on her rescuers told her palace servants had put a halt to things.

Two hands wrapped around her arm and drew her to her feet. Kel looked down a couple of inches into Owen of Jesslaw’s shining grey eyes. ‘That was jolly!’ he said. Apparently a bloody nose and a cut that dripped blood into his ear were not important. ‘Did you learn to fight like that here?’

‘So.’ Lord Wyldon coldly eyed Kel and Owen. ‘Already you instruct the new boys in your brawling ways.’

‘We fell down,’ Kel replied steadily. She knew this play by heart; so did the training master. First he questioned the senior pages, who claimed they had fallen. Then he questioned her – and, for the first time, the boy who’d been the object of the hazing. No other first-years had stayed to help before.

‘Three footmen and a torch boy said you were fighting,’ Lord Wyldon pointed out.

‘They were mistaken, my lord,’ she replied.

Wyldon drummed his fingers on his desk. Finally he said, ‘Owen of Jesslaw, you have made a very poor start. Report to Osgar Woodrow at the forge outside the squires’ armoury for the first bell of time every night after supper for a week. You may cool your passions by sharpening swords.’ His brown eyes locked on Kel. ‘As for you, Mindelan – report to Stefan Groomsman at the same hour. He is to find you work pitching hay down from stable lofts.’

Clammy sweat broke out between Kel’s shoulder blades. ‘St-stable lofts, my lord. Of course.’ At training camp before the summer holiday, Lord Wyldon had made Kel climb every day to deal with her fear of heights. Kel bit her lip guiltily: while she had trained all summer, she had not tried to look down from anything higher than a few steps. I bet he knew, she thought queasily. I bet he knew I didn’t climb anything on holiday.

‘A final word, Page Keladry.’ Lord Wyldon stood, bracing his hands on his desk. ‘This will stop,’ he said tightly. ‘There was never so much fighting before you came. It will end now.’

Maybe you just never heard about all the fights, Kel thought wearily. Big boys picking on little ones just to be mean. Maybe no one made enough of a fuss to bring it to your notice.

From the corner of her eye she saw the red-faced Owen open his mouth. Kel bowed to Wyldon and managed to stumble, banging into the new boy. The training master waited for them to stand at attention once more, then dismissed them.

‘Why’d you do that?’ demanded Owen when they closed the door behind them. ‘Why’d you bump me?’

‘Because you were about to say something,’ she replied calmly. ‘You aren’t supposed to say anything except that you fell down. Whatever punishment he gives you, whatever he says, you take it in silence.’

‘But they started it,’ he argued. ‘You were helping out another noble, like we’re supposed to, and they waded into you.’

Kel sighed. ‘That’s not why I did it.’

Turning into their own hallway, Kel and Owen halted. The prince, Neal, Cleon, and Kel’s other friends stood there, waiting.

‘Good evening, your highness,’ Kel said.

Prince Roald nodded gravely.

Neal strode over to her. ‘What on earth did you think you were doing? I thought we solved all this last year!’

Kel replied, ‘We did.’

‘Then why did you patrol without us? We had a deal. We went with you and we dealt with that lot as a team.’

‘Don’t yell at her,’ Owen snapped. ‘You should have seen her fight. And they started it.’

The prince smiled at him. Roald of Conté was a fourth-year page, quiet and contained, with his father’s very blue eyes and black hair that could have come from either of his parents. He was so polite that he appeared stiff, and he made friends with difficulty, but when he spoke, he was listened to. ‘We have been trying to stop the hazing of first-years,’ he told Owen. ‘And I believe I suggested that you study with our group.’ Roald was Owen’s sponsor, charged with teaching him palace ways.

‘But there was a library, your highness,’ Owen said. ‘A big one. I was just going to look.’

‘And I wasn’t patrolling,’ replied Kel. ‘I had to see Daine. When I came downstairs …’ She shrugged.

‘And got a black eye for your pains,’ Neal said with disgust. He reached towards her, green magical fire shimmering around his fingertips.

Kel stepped back. ‘You’ll get in trouble with my lord if you heal something he can see,’ she pointed out. ‘Fix Owen’s cut.’

Now it was the plump boy’s turn to step back. ‘What?’ Owen demanded nervously.

‘Neal has the healer’s Gift of magic,’ said the prince. ‘Don’t be silly. He can at least make it so that cut and your nose don’t hurt as much.’

Owen rolled his eyes, but let Neal care for his injuries. The cut in his scalp was shallow; Neal shrank that. ‘The nose isn’t worth troubling with,’ he told Owen. ‘It’s not broken. Just be careful how you blow it.’ He looked at Kel with a rueful smile. ‘Might we at least get some classwork done?’

Kel went to her rooms. Gathering her books, she was trying to remember her assignments when she heard a sound behind her. She whirled, dropping her books. Someone gasped and ducked inside the dressing room.

‘Who—?’ Kel began, then remembered: Lalasa. She would sleep in the dressing room, like the servants who attended other pages. Kel had seen Lalasa’s cot and the wooden screen that gave her privacy when she took her bath. ‘It’s just me.’

The older girl peered around the door, then ran forward and knelt to gather Kel’s fallen books. ‘My lady, forgive me, I never meant—’ She glanced up at Kel and gasped again. ‘My lady, your pardon, your poor eye! Who could have done such a thing? Shall I fetch a healer – no, Uncle says only my lord Wyldon may approve healers … A cut of meat, perhaps ice from the ice house if they’ll let me have it. Oh, my lady,’ she wailed, her hands clasped before her.

Kel blinked at her. ‘It’s just a black eye,’ she said. ‘Please don’t dither at me.’

‘But it’s all swollen! How can you see?’

‘Badly,’ admitted Kel. ‘It’ll mend. I’ve had them before.’

‘Doesn’t it hurt?’ begged Lalasa. ‘You act like it’s nothing.’

Kel shrugged. ‘It hurts, yes, but not as bad as some I’ve had. May I have my books, please? I have to study.’

Neal stuck his head in the door. ‘Are you coming?’ he demanded. ‘We only have a bell left before bedtime, and half of us are stumped on that catapult mathematics problem. Who’s she?’

Kel sighed and introduced Neal to Lalasa. The girl who had been so outspoken in her dismay went quiet the moment she saw Neal. Silently she backed towards the dressing room, stopping only to curtsy when Kel gave her friend’s name.

Why hide? wondered Kel as she left the room with Neal. ‘Does she know you?’ she asked as they went to his rooms.

‘No – should she? I mean, I saw her working in the squires’ wing once or twice last year. Timid little creature.’

His chambers were crowded. With the addition of the first-years to their study group, there was a boy on every surface that might be claimed as a seat. The cluster on the bed shifted, making room for Kel. They were all boys who had got her help with mathematics before: it was Kel’s favourite subject, and she was good at it.

Who would believe it was just Neal and me a year ago? she thought. I thought we’d never have any friends, what with Lord Wyldon hating him for being fifteen and educated, and me being The Girl.

About to take the offered place, she had an idea. ‘You know, they do allow study groups to meet in the libraries.’ She smiled. ‘I believe there’s room for us in the classroom-wing library.’ Last year Joren and his friends had made life miserable for any first-year who entered the room. It was only right that their group reclaim it for people who wanted to study.

The boys looked at each other, then at Kel. Without a word they gathered their things and streamed out of Neal’s room. Owen left skipping to a soft chant of ‘Books, books, books!’

Neal threw open his arms as if to embrace his now-empty chambers. ‘What shall I do with all this space in the evenings?’ he enquired airily, waving Kel out ahead of him. ‘Plant a garden, perhaps, begin my eagerly awaited career in sculpting—’

‘If I were you, I’d practise my staff work,’ Kel replied. ‘You need to.’

The bell that signalled the end of their day clanged, and the pages returned to their rooms. By then Kel felt each and every bruise from the fight and from her day’s training with that weighted harness. Stiffly she put her books on her desk, noticing a mild, clean scent in the air.

‘I made willow tea for my lady,’ explained Lalasa as she poured a cup from the kettle on the hearth. ‘And Salma gave me a package for you.’

Kel looked the package over. It was like others she’d received from an unknown benefactor: a plain canvas wrapper tied with string and a plain label. She undid the knots and pulled the canvas away to reveal a small wooden box.

She wriggled the top off to reveal the contents: a pamphlet and three oval leather balls, each of a size that would fit into her palm. Did her mysterious well-wisher want her to learn to juggle? She picked up a ball, which was heavier than it looked. Kel squeezed it. From the texture, it was filled with sand.

‘What on earth?’ she muttered, and leafed through the pamphlet. It was hand-lettered and clearly illustrated. Suddenly she began to grin.

‘What is it, my lady?’ asked the maid.

‘Exercises,’ replied Kel. ‘For my arms, and my hands.’ She moulded the leather ball in her left hand, squeezing hard. ‘This is supposed to strengthen my grip.’ How does he know, or she, what’s needed? Kel wondered, scanning the descriptions of the exercises. Last year it had been a good knife, her jar of precious, magicked bruise balm, and a fine tilting saddle for Peachblossom. Now it was more exercises, small ones she could do any time, that would help to build strength in her hands and arms.

Reminded of the bruise balm, Kel took the jar out of her desk and dabbed a little on her swollen eye. The throbbing ache in it began to fade.

I wish I knew who you were, she thought, sipping the tea that Lalasa had made. I would like to thank you – and ask why you do these things for me.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_ded6ee0d-a746-5c2a-a300-960670915e36)

BRAWL (#ulink_ded6ee0d-a746-5c2a-a300-960670915e36)

The next morning Kel rose before dawn as always. It was not easy. She felt stiff, old, and battered. When she stubbed her toe, she remembered that she could only see through one eye. At least the blackened eye no longer ached so much.

I could have had ice, Kel thought bitterly. But no. I had to be tough. I was mad when I chose this life, she decided as she unlocked her large shutters. I was stark raving mad, and my family was too polite to mention it. That’s what living with the Yamanis does to people. They get so well-mannered they won’t mention you’re crazy.

She opened the shutters wide. Outside lay a small stone-flagged courtyard with a slender, miserable tree at the centre. The flock of sparrows perched on its branches headed for Kel, swirling around her in a rustle of feathers and a chorus of peeps. Except during winter, they preferred to sleep outside and join her for seed and water in the short grey time before sunrise. While most of the birds went straight to the dishes, a few landed on her shoulders and arms. Kel gently stroked their heads and breasts with a finger. She had nearly thirty after the spring nesting. Brown-and-tan females and males, the males also sporting black collars, they appeared to see Kel as a source of food and entertainment. They chattered to her constantly, as if they hoped that with enough repetition, this great slow creature would understand them.

She was admiring the male whose pale-spotted head had earned him the name Freckle when something large and white vaulted the windowsill on her blind side. It landed beside her with a thump as the sparrows took to the air. She backed up to look at it properly.

The dog Jump grinned cheerfully at her, tongue lolling. His crooked tail whipped the air briskly.

‘Absolutely not,’ Kel said firmly. She pointed to the window. ‘You live with Daine now! Daine!’

Jump stood on his hind legs and thrust his heavy nose into Kel’s hand.

‘How did you know to come in here?’ Kel leaned out of her window. If she hadn’t been so vexed, she would have been impressed – it was four feet from the ground to her sill. She turned to glare at the dog. ‘Back to Daine, this instant!’ she ordered. ‘Out!’

‘Out?’ a quavering voice enquired. Lalasa stood at the dressing room door. ‘What did I—’

Kel pointed to Jump.

‘Oh. The dog has returned.’ Lalasa padded out into the main room and poked up the hearth fire, then put a full pot of water over it. ‘My lady should have roused me. I did not mean to lay abed after my lady was up.’

‘I wake before dawn,’ Kel said, going to the corner where she had left her practice glaive. ‘I practise before I dress.’ She gave the weapon an experimental swing, making sure there was plenty of clear space in this part of her room. She didn’t want to break anything as she exercised.

At least she had got some real glaive practice over the summer. While her sisters Adalia and Oranie, young Eastern ladies now, had lost the skills they learned in the Yamani Islands, their mother had trounced Kel every day for a month before Kel’s old ability had returned. Kel often thought that Ilane of Mindelan could give even the Shang warriors who taught the pages a real fight with a glaive.

Kel swept the weapon down and held it poised for the cut named ‘the broom sweeps clean’. Her grip was not quite right. She adjusted it and looked up, ready to begin the pattern of movements and strikes that were her practice routine.

Lalasa stood against the wall beside the hearth. Her hands, covered by the large quilted mitts used to lift hot things off the fire, were pressed tight over her mouth. Her eyes were huge.

Now what? Kel wanted to say. She wasn’t used to explaining her every move to someone. Instead of scolding, she bit her tongue and made herself think of a lake, quiet and serene on a summer’s day. When she had herself under control, she asked, ‘What’s the matter, Lalasa?’

‘I – I want to be out of your way, my lady, is all. It’s so big. Do you always swing it like that?’

Kel looked at her weapon, confused. It was just a practice glaive, a five-foot-long wooden staff with a lead core, capped by a curved, heavy, dull blade eighteen inches long. ‘That’s what it’s for. See, you can wield it like a long-handled axe’ – she brought the glaive up overhand and chopped down – ‘or you can thrust with it.’ Kel shifted her hands on the staff and lunged. ‘Or you can cut up with the curved edge.’ She swung the weapon back to the broom-sweeps-clean position, and stopped. Lalasa was plainly more frightened than ever. ‘You could learn to use it,’ offered Kel. ‘To protect yourself. The Yamani ladies all know how to wield the glaive.’

Lalasa shook her head vigorously. Grabbing the pot of hot water, she scuttled into the dressing room with it.

I wish she wasn’t so nervous, Kel thought, clearing her heart for the pattern dance. I hope she gets over it.

She put Lalasa from her mind and took her opening position. Step and lunge … Her stiff body protested. She was panting by the time she was done. Next she forced herself through twenty of the floor press-ups that Eda Bell, the Shang Wildcat, had said would strengthen her arms. As she finished, the great bell that summoned all but the deafest nobles from their beds rang. It was the beginning of another palace day.

Kel walked into the dressing room. Hot water steamed in her basin; soap, drying cloth, brush, comb, and tooth cleaner were all laid out neatly beside it. Even in here, Lalasa had made things more comfortable. A tall wooden screen hid her bed and the small box that held her belongings. She had found a scarlet rug somewhere, a brazier for heat when it turned cold, and a cloth hanging to cover the privy door. Kel’s morning clothes – shirt, canvas breeches, stockings, boots, a canvas jacket – were draped neatly over a stand that Kel had always thought was a hurdle put in her room by mistake.

‘Lalasa,’ she said when she was dressed, ‘would you like to learn ways to make people let go? Holds, and twists to free your arms, grips that will make them think twice about bothering you? I know some, and—’

Lalasa shook her head so hard that Kel wondered if her brain might rattle. ‘Please no, my lady,’ she said in her tiny, scared voice. ‘It’ll be different now, with my having a proper mistress. That’s what Uncle said. The nobles don’t mess with each other’s servants. And I’ll be careful. I’ll be no trouble to you, my lady, you’ll see.’

‘Hey, Mindelan!’ someone yelled in the outside hall. ‘Come on!’

Kel sighed and looked at Jump. He had watched her get ready, his tiny eyes intent. ‘After breakfast, will you take him to Daine?’ she asked. ‘She’s on the floor above the classrooms, with—’

Lalasa was shaking her head again. ‘My lady, she’ll turn me into something. She’s uncanny, forever talking to animals and covered with the mess they make …’

Kel was a patient girl, but there was something to Lalasa’s meekness that set her teeth on edge. ‘That’s silly,’ she snapped.

Lalasa stared at the floor.

And here I’ve frightened her again, thought Kel. Now her head ached as much as the rest of her. ‘Look. Will Gower do it, if you ask him? Take Jump up to Daine?’

Lalasa nodded. ‘Yes, my lady.’

‘Then please ask him to.’ Kel left before she could say anything else.

Lalasa just needs to get used to me, she told herself as she joined the boys headed for the mess hall. She just needs to learn I won’t be mean to her. Then she won’t be so, so mouse-ish. Please, Goddess.

Neal’s first block of Kel’s first punch felt every bit as soft and weary as her blow. They both made faces.

‘What’s the matter, second-years? Tired?’ Kel had always thought that Hakuin Seastone, the Shang Horse, was improperly cheerful for a Yamani. Now he circled her and Neal, grinning. He was tall for an Islander, with plump lips and dark, almond-shaped eyes framed with laughlines. His glossy black hair was cropped short on the sides and long on top, so a hank of it always lay against his broad forehead like a comma. He wore plain practice clothes and went barefoot. ‘Add two pounds of weight to your chests and you act like you carry the world. Put strength into your blocks. I want those punches to mean something! What if you’re unhorsed and fighting in mail or plate armour? You’ll wish you’d listened to old Hakuin then. Ready, begin. High punch, high block! Middle punch, middle block! Low punch, low block!’

His teaching partner, the Shang Wildcat, peered into Owen’s face. She was an older woman, her skin lightly tanned from summer, her close-cropped curls silvery white. ‘What are you looking at the seniors for?’ she asked Owen, pale eyes glinting. ‘You don’t get to look around till you punch like a fighter, not a cook kneading bread.’

Kel tried to will more vigour into aching muscles. At breakfast Faleron and Roald had said that everyone was exhausted when they first donned the harness, or when new weights were added, but Kel didn’t remember if she had noticed the older pages struggling last year.

‘I hear the third day’s worse,’ Neal moaned as the bell rang. It was their signal to lurch to the yard where Lord Wyldon and Sergeant Ezeko drilled them on staff combat.

‘I just want to live through today,’ said Merric as they filed down the hill.

The fourth-years, walking behind them, pushed by the younger pages to take the lead. They did it roughly, yelling, ‘Oldsters first!’ Passing Kel, Joren thrust his elbow back, clipping her black eye. Kel gasped and bent over, covering her throbbing eye.

A cool hand rested on hers, and something flowed through her fingers. The pain vanished. Kel took her hand away, and glared at Neal.

‘It still looks nice and puffy and colourful.’ His voice was dry, his green eyes worried. ‘Kel, we have to do something about him.’

‘Yes,’ she replied, ‘stay out of his way. Joren’s a page for just one more year, and that’s what I mean to do.’

‘She’s right.’ The prince stopped beside them. ‘If she takes revenge, she’s the one who will look bad.’

‘So there,’ Kel told Neal, and marched on down to the next practice court. Beneath her calm exterior she wished fiercely that she could pound the meanness out of Joren. Even as she thought it, she knew she would do better to ignore him. Water, she thought, collecting her staff from the shed where it was kept. I am a summer lake on a windless day, clear, cool, and still. Joren is a cloud. All he can do is cast a shadow on my surface. I’ll be here long after he’s gone. She concentrated on that thought fiercely until Lord Wyldon and the sergeant barked orders for the first series of exercises.

The yard rang with the clack of wood striking wood and yelps from those pages whose fingers got hit. Kel listened to the noise and let it fill her – it worked better than thoughts of a clear lake to clear her head. At least she was less stiff after their time with the two Shangs.

Settled into the rhythm of the first exercise, she looked for the training master. Lord Wyldon watched them from the fence. Keeping his eyes on them, he crouched to scratch the ear of an ugly white dog with black spots.

Kel’s attention wavered; Faleron smacked her collarbone with his staff. The force of the blow drove her to her knees as pain shot like lightning through her right side.

‘Kel, you didn’t block it!’ cried Faleron, appalled. ‘Neal—’

‘Back in line, Page Nealan!’ Ezeko ordered as he came over. ‘If there’s a break, she’ll see a proper healer!’ He knelt beside Kel and felt her collarbone, his fingers gentler than his face. He was a barrel-chested black man, a Carthaki veteran who had fled slavery to enter Tortall.

‘Just – a bruise, I think,’ Kel said, gasping for breath. ‘The – the strap—’

The sergeant pulled her jacket aside, examining the harness. ‘You took the blow on that?’ he demanded. ‘I don’t feel anything broken.’

Kel nodded.

‘Stupid,’ Ezeko told her. ‘You haven’t let anybody land one in months. I don’t care how tired you are, pay attention!’

‘If we are done fluttering over the girl?’ Lord Wyldon demanded, walking over. ‘Back to work, lads. Can you use the arm?’ he asked Kel gruffly.

The emperor’s soldiers fight with broken arms, Kel thought, remembering the hard-faced men who defended the Yamani court. It isn’t broken, just bruised. Really bruised. She nodded, meeting Lord Wyldon’s gaze squarely.

He sighed. ‘Yancen of Irenroha, pair with Faleron.’ Yancen, a third-year, obeyed. ‘Mindelan, with Prosper of Tameran.’ Prosper was a new page. Kel saw what Lord Wyldon intended: she could defend herself against Prosper even with a bad right arm. As Wyldon continued to rearrange the pairs, Kel glanced at the fence where he’d been. Jump noticed her look and wagged his tail.

Neal saw the dog as they were putting their staffs away. ‘Is that—?’ he asked. Lord Wyldon was scratching Jump’s spine.

Kel nodded.

‘I thought you gave him to Daine,’ Neal murmured.

‘I did,’ she replied. They walked to the archery courts with the other pages. Lord Wyldon and Sergeant Ezeko brought up the rear, Jump trotting beside them.

‘You know, if he doesn’t want to stay, Daine won’t make him,’ Neal whispered.

Kel sighed. She did know. The Wildmage had refused to change the nature of Kel’s contrary mount Peachblossom. ‘That’s why she said she would try to keep Jump,’ Kel told Neal gloomily as they gathered their bows and quivers of arrows. ‘Because she thought maybe he wouldn’t stay with her.’

When she looked around halfway through the archery lesson, the dog was nowhere in sight. Kel took heart. Perhaps Jump had realized Kel wouldn’t encourage him.

Perhaps he’s off stealing and getting chopped up by that cook, a treacherous voice whispered in her mind. Kel ignored it. She couldn’t solve the world’s problems, after all. Not yet, at least.

Her relief and worry turned to resentment as the boys reached the pages’ stable for their final morning class. Jump sat by the door, scratching one of his scars.

‘Go away,’ she muttered as she walked by. ‘Go back to Daine!’

As she opened the door to Peachblossom’s stall, the dog trotted in ahead of her. His jaunty air suggested that a horse of Kel’s was a horse of his. Peachblossom instantly put back his ears, retreated until his rump hit the stable wall, and stamped. Jump sat and regarded the horse.

Peachblossom was a horse to regard with care. He was a small destrier who would have been too big for Kel if he had not allowed her to ride him. He was gelded, with strawberry roan markings: reddish brown stockings, face, mane, and tail, and a rusty coat flecked with white. Only three people could handle him without getting bitten, Kel, Daine, and the chief ostler, Stefan Groomsman.

‘Ignore the dog,’ she advised the gelding as she stiffly went over him with a brush. ‘He thinks he belongs to me, but he’s mistaken.’

Peachblossom snorted disbelief, but he’d found the apple Kel had brought, and he did like the brush. He stepped away from the wall.

Despite the pain in her shoulder, Kel put the riding saddle on him and mounted up. This week there would be no work with the lance and the heavier tilting saddle. The pages would be riding only, the seniors to show they hadn’t gone soft over the holiday, the first-years to show they could manage a horse. It was boring, but as the ache in her shoulder spread, Kel decided boredom was preferable.

At least Jump didn’t follow them out, or if he did, he made sure Kel never saw him. She was able to concentrate on putting Peachblossom through his paces until the end-of-morning bell. She returned to the stable and groomed her mount, glad the morning had ended.

Faleron, whose fire chestnut was Peachblossom’s neighbour, leaned on the rail between the stalls. ‘Kel, I’m still not sure about that catapult problem,’ he confessed, embarrassed. He knew more Tortallan law than any other page, but mathematics came hard for him. ‘If I fetch it to lunch, would you take a look?’

Kel nodded. ‘You didn’t have to ask, you know.’

Faleron grinned. ‘Mama raised me polite.’

In a nearby stall Garvey muttered, ‘So, Faleron, you’re friends with her now because you can have her whenever you want?’

Faleron threw down his brush and went for the other boy. Sore shoulder or no, Kel flew out of the stall. She caught Faleron just a foot from the sneering Garvey and hung on to him, putting all of her weight into it.

The older boy fought her grip. ‘Gods curse it, Kel, you heard what he said!’

‘I heard a fart,’ Kel said grimly. ‘You know where those come from. Let it go.’

Faleron relaxed, but she still kept both hands wrapped around his arm. He was easy-going, but everyone had sore spots. At last Faleron made a rude gesture at Garvey and let Kel pull him away.

They had almost reached their horses when Neal’s unmistakable drawl sounded through the stable: ‘Joren is so pretty. Say, Garvey, are you two friends because you can have him?’

Garvey roared and charged, but Joren got to Neal first. Before they landed more than a punch each, Neal’s friends, including Kel, attacked them. More boys entered the brawl, kicking and hitting blindly, striking friend as often as foe. Kel nearly fainted when someone’s boot hit her bruised collarbone.

Above the din made by boys and frightened horses, Kel heard the sound of breaking wood. Realizing she would never reach Neal, praying he didn’t get his silly head broken, she grabbed Merric and Seaver by the collar and backed up, dragging them with her. The press of bodies behind her let up suddenly; she nearly fell over backwards.

Startled, she looked around and saw Peachblossom. His teeth firmly sunk into Cleon’s jacket, the gelding drew the big youth out of the fray. Prince Roald gripped Owen by both arms to keep him out of the brawl; Roald’s horse, the black gelding Shadow, held Faleron by the arm as he slowly pulled him free. Zahir’s bay shouldered through the mob, stepping on no one, but forcing them to move away from him and each other.

For a moment a chill ran through Kel. She thought uneasily, The animals here are so strange. Then she shook it off. The harridan who trained the ladies of the Yamani court to defend themselves had always said, ‘We use the tools at hand.’ These animals, uncanny or not, were the right tools for this mess.

She thrust Merric and Seaver into a ruined stall and grabbed Cleon’s arm. ‘Peachblossom, can you find Neal?’ she asked her horse.

The big gelding released Cleon’s jacket, blew scornfully, and waded into the fight. Unlike Zahir’s bay, he was not careful of feet or fingers. If they were in the way, Peachblossom stepped on them. Several boys rolled clear to nurse bruises and broken bones.

‘You can let go, Kel,’ said Cleon, his voice dry. He watched Cavall’s Heart, Lord Wyldon’s dark dun mare, who had also broken out of her stall. She dragged Garvey out of the pile. ‘Even I’m not stupid enough to argue with horses. Particularly not these horses.’

Kel glared up at him. Cleon was a fourth-year, but he was also a friend. ‘I’m glad you’re smart enough to realize that much,’ she told him.

Cleon slapped her cheerfully on the back. ‘What’s the matter, dewdrop? Don’t you like men fighting to protect your honour?’

‘I can defend my own honour, thank you,’ she replied. ‘I thought it was Joren’s honour at stake. And stop calling me those idiotic nicknames. That joke is dead and rotting.’ She watched as Jump grabbed Vinson by the ankle, stopping the boy’s attempts to kick anyone.

Peachblossom had just seized Neal’s jacket, with Neal’s shoulder in it, when Lord Wyldon, Sergeant Ezeko, and three stable hands entered. They tossed the buckets of water they carried on the pages. Silence fell.

‘I want this place straightened up and these horses groomed afresh.’ Lord Wyldon’s voice, and eyes, were like iron. ‘That includes Heart. You will then wash and assemble in the mess hall. I will address you further there.’ He looked them over, pale with fury. ‘You are a disgrace, the lot of you.’ He turned on his heel and walked out.

Silently the pages got to work.

By the time they reached the mess hall, Lord Wyldon had worked out their punishment. It included bread-and-water suppers for a week, study alone in their rooms at night, no sweets, and no trips out of the palace until Midwinter. Those pages who already had Sunday afternoon punishment work were to put that off until the general punishment was done. They were all to help carpenters rebuild the stable. Finally, the training master added two more lead weights to the senior pages’ harnesses.

The subdued pages went to afternoon classes in nearly complete silence. When it was time to dress for supper, Kel scrambled into her shift and gown, stopping only to demand of Lalasa why Jump hadn’t been taken to Daine that morning. When Lalasa, cringing, replied that Gower had carried the dog up to the Wildmage right after breakfast, Kel shook her head. She would have to deal with Jump later.

Still wearing boots and heavy wool stockings under her gown, she went to Neal’s room and pounded on his door. He let her in without a word, but protested when she closed the door behind her.

‘Do you want everyone hearing what I have to say?’ she demanded sharply.

‘If the Stump catches you here with the door shut—’ The Stump was Neal’s nickname for Lord Wyldon.

‘He won’t.’ Kel put her fists on her hips and glared at her friend. ‘You were sixteen last month. You’re supposed to know better. Did you honestly think you were helping me down there?’

He had the strangest look on his face. ‘Are you – Kel, the Yamani Lump – are you yelling at me?’

‘Yes, I am!’ Kel snapped. ‘You didn’t solve anything, you just made it worse!’

He sat on his bed. ‘Maybe, maybe not. I think they’ll reconsider, next time they want to start fights over your virtue.’

Kel blinked at him. ‘What has my virtue to do with anything?’

‘I’m surprised they didn’t try it last year. Oh, I suppose they made dirty little jokes with each other, never mind that a real knight is supposed to treat women decently. Maybe they thought saying you’re a lump, and not as strong, and on probation, was bad enough.’

‘Are you making sense yet?’ Kel wanted to know. This conversation had taken a very uncomfortable turn.

‘But you’re still here. Now they’re really worried. They haven’t changed their minds about lady knights just because Wyldon let you stay.’

‘I didn’t expect them to,’ Kel informed him.

‘Well, so, they decided to try new insults today. And talk of different kinds of sex makes people crazy.’

‘Your point is …?’ she asked. Her mother had explained how babies were made. Nariko had taught the court ladies, including Kel’s family, how to preserve their honour from rapists. That didn’t seem to be what Neal was talking about.

‘See, Kel, if all of a sudden everyone’s getting into fights about your virtue, maybe the Stump will get rid of you after all.’ Neal sighed and finger-combed his hair back from his face.

Fear trickled down Kel’s spine like cold water. Could Lord Wyldon change his mind? Who would protest if he did? The king had allowed her to be put on probation in the first place. No doubt if Wyldon told him Kel had to go, the king would agree. ‘I’m eleven,’ she said at last. ‘That’s too young to be lying with men, Neal. Much too young.’

He inspected a bruise on his wrist, and touched a fingertip to it. A green spark flashed and the bruise faded. ‘Facts don’t matter with Joren and his crowd. Just gossip. Just making your friends angry enough to fight. I reminded them that gossip is a tricky weapon, that’s all. It cuts two ways.’

Kel sighed. ‘I still don’t think you did me any good. I can take a few insults.’

‘You can – I can’t.’ Neal peered out the door. ‘Hall’s empty. Shoo.’ As she walked by, he added, ‘I consider myself chastised.’

She stopped and turned back. ‘What you said about Garvey and Joren – it’s not an insult in Yaman. Some men prefer other men. Some women prefer other women.’ Kel shrugged.

‘In the Eastern Lands, people like that pursue their loves privately,’ replied Neal. ‘Manly fellows like Joren think it’s a deadly insult to be accused of wanting other men.’

‘That doesn’t make sense,’ Kel said.

‘It’s still an insult on this side of the Emerald Ocean, my dear. Now, if I may shave before our bread-and-water feast?’

Kel eyed Neal’s cheeks and chin. ‘You don’t need to.’

Neal sighed. ‘I live in hope, as the priest said to the princess. If you don’t mind?’

Kel went back to her room, shaking her head.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_9275ccd7-57c9-5b01-ac14-9717ca256b87)

WOMAN TALK (#ulink_9275ccd7-57c9-5b01-ac14-9717ca256b87)

Their punishments for the stable fight cooled the hottest tempers. Kel thought just the addition of two more harness weights would have done it. Even the fourth-year pages were not ready for the change, and it was astonishing how much difference an extra pound made. For weeks Kel felt as if her bones had turned to wax. Master Oakbridge, whose etiquette class was at the end of the day, began to hit their desks with his pointer stick to keep them awake. Extra work, given when sleepy pages didn’t finish classwork, piled on top of Lord Wyldon’s physical penalties.

Bread-and-water suppers did not help. Scant meals on their schedule meant growling bellies. Sometimes Kel thought it was hunger and the prospect of added weights, rather than insults that cut two ways, that made Joren and his friends leave her and her crowd alone.