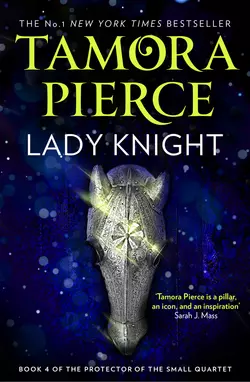

Lady Knight

Tamora Pierce

Duty or glory: which will she choose? The adventure continues in the final instalment of the New York Times bestselling series from the fantasy author who is a legend herself: TAMORA PIERCE. A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. Keladry of Mindelan has finally achieved her lifelong dream of becoming a knight – but it’s not quite what she imagined. In the midst of a brutal war, Kel has been assigned to oversee a refugee camp. Others are sent to fight. Though certain she has been given this inglorious and difficult task because Lord Wyldon continues to deny she is equal to her male peers, Kel is learning the importance of caring for people who havebeen robbed of their homes, of self-respect and of safety. Perhaps this is the most important battleground in the war? But when Kel discovers truths behind the monstrous killing devices that her friends are fighting without her, will she honour her sworn duty... or embark on a quest that could turn the tide of the war? A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. In a landmark quartet published years before it’s time, Kel must prove herself twice as good as her male peers just to be thought equal. A series that touches on questions of courage, friendship, a humane perspective – told against a backdrop of a magical, action-packed fantasy adventure. ‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones’Washington Post

LADY KNIGHT

BOOK 4 OF THE PROTECTOR OF THE SMALL QUARTET

Tamora Pierce

Copyright (#u0bd1f467-fa25-5e57-9e0c-96a17134a055)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Tamora Pierce 2002

Map copyright © Isidre Mones 2017

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Tamora Pierce asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008304287

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008304294

Version: 2019-06-25

PRAISE FOR TAMORA PIERCE (#u0bd1f467-fa25-5e57-9e0c-96a17134a055)

‘Tamora Pierce didn’t just blaze a trail. Her heroines cut a swathe through the fantasy world with wit, strength, and savvy. Pierce is the real lioness, and we’re all just running to keep pace.’

LEIGH BARDUGO, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce creates epic worlds populated by girls and women of bravery, heart, and strength. Her work inspired a generation of writers and continues to inspire us.’

HOLLY BLACK, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce’s books shaped me not only as a young writer but also as a young woman. Her complex, unforgettable heroines and vibrant, intricate worlds blazed a trail for young adult fantasy – and I get to write what I love today because of the path she forged throughout her career. She is a pillar, an icon, and an inspiration.’

SARAH J. MAAS, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones’

Washington Post

‘Tamora Pierce and her brilliant heroines didn’t just break down barriers; they smashed them with magical fire.’

KATHERINE ARDEN, author of The Bear and the Nightingale

Dedication (#u0bd1f467-fa25-5e57-9e0c-96a17134a055)

To the people of New York City, I always knew the great sacrifice and kindness my neighbours are capable of, but now the rest of the country knows, too.

Contents

Cover (#u588938ff-ffcc-5c1d-ae5d-bd801dabf303)

Title Page (#u57f9a7c3-ed15-54df-8f51-d4d94e8ae76d)

Copyright

Praise for Tamora Pierce

Dedication

Map

Mid-March, Corus, the capital of Tortall; in the 21st year of the reign of Jonathan IV and Thayet, his Queen, 460 H.E. (Human Era)

Chapter 1: Storm Warnings

Chapter 2: Tobe

April 1–14, 460 near the Scanran border

Chapter 3: Long, Cold Road

Chapter 4: Kel Takes Command

April 15–23, 460 the refugee camp on the Greenwoods River

Chapter 5: Clerks

Chapter 6: Defence Plans

Chapter 7: Tirrsmont Refugees

Chapter 8: First Defence

April 30, 460 Fort Mastiff

Chapter 9: Mastiff

May 2–3, 460 Haven

Chapter 10: The Refugees Fight

May 6–June 3, 460 Haven and Fort Mastiff

Chapter 11: Shattered Sanctuary

June 4–7, 460 Haven and Fort Mastiff

Chapter 12: Renegade

Chapter 13: Friends

Chapter 14: Vassa Crossing

June 8, 460 Scanra, between the Vassa and Smiskir Rivers

Chapter 15: Enemy Territory

June 9–10, 460 the Pakkai road

Chapter 16: Opportunities

June 10–11, 460 Blayce’s Castle

Chapter 17: The Gallan’s Lair

Chapter 18: Blayce

September 10, 460

Epilogue

Cast of Characters

Glossary

Notes and Acknowledgments

Read on for a Preview of Tempests and Slaughter

Also by Tamora Pierce

About the Publisher

Map (#u0bd1f467-fa25-5e57-9e0c-96a17134a055)

Mid-March, Corus, the capital of Tortall; in the 21st year of the reign of Jonathan IV and Thayet, his Queen, 460 H.E. (Human Era) (#u0bd1f467-fa25-5e57-9e0c-96a17134a055)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_070eeb3a-2e86-5d2c-a0a5-c07fa69ede0c)

STORM WARNINGS (#ulink_070eeb3a-2e86-5d2c-a0a5-c07fa69ede0c)

Keladry of Mindelan lay with the comfortable black blanket of sleep wrapped around her. Then, against the blackness, light moved and strengthened to show twelve large, vaguely rat- or insectlike metal creatures, devices built for murder. The killing devices were magical machines made of iron-coated giants’ bones, chains, pulleys, dagger-fingers and -toes, and a long, whiplike tail. The seven-foot-tall devices stood motionless in a half circle as the light revealed what lay at their feet: a pile of dead children.

With the devices and the bodies visible, the light spread to find the man who seemed to be the master of the creations. To Keladry of Mindelan, known as Kel, he was the Nothing Man. He was almost two feet shorter than the killing devices, long-nosed and narrow-mouthed, with small, rapidly blinking eyes and dull brown hair. His dark robe was marked with stains and burns; his hair was unkempt. He always gnawed a fingernail, or scratched a pimple, or shifted from foot to foot.

Once that image – devices, bodies, man – was complete, Kel woke. She stared at the shadowed ceiling and cursed the Chamber of the Ordeal. The Chamber had shown Kel this vision, or variations of it, after her formal Ordeal of knighthood. As far as Kel knew, no one else had been given any visions of people to be found once a squire was knighted. As everyone she knew understood it, the Ordeal was straightforward enough. The Chamber forced would-be knights to live through their fears. If they did this without making a sound, they were released, to be proclaimed knights, and that was the end of the matter.

Kel was different. Three or four times a week, the Chamber sent her this dream. It was a reminder of the task it had set her. After her Ordeal, before the Chamber set her free, it had shown her the killing devices, the Nothing Man, and the dead children. It had demanded that Kel stop it all.

Kel guessed that the Nothing Man would be in Scanra, to the north, since the killing devices had appeared during Scanran raids on Tortall last summer. Trapped in the capital by a hard winter, with travel to the border nearly impossible, Kel had lived with growing tension. She had to ride north as soon as the mountain passes opened if she was to sneak into Scanra and begin her search for the Nothing Man. Every moment she remained in Tortall invited the growing risk that the king would issue orders to most knights, including Kel, to defend the northern border. The moment Kel got those orders, she would be trapped. She had vowed to defend the realm and obey its monarchs, which would mean fighting soldiers, not hunting for a mage whose location was unknown.

‘Maybe I’ll get lucky. Maybe I’ll ride out one day and find there’s a line of killing devices from the palace right up to the Nothing Man’s door,’ she grumbled, easing herself out from under her covers. Kel never threw off her blankets. With a number of sparrows and her dog sharing her bed, she might smother a friend if she hurried. Even taking care, she heard muffled cheeps of protest. ‘Sorry,’ she told her companions, and set her feet on the cold flagstones of her floor.

She made her way across her dark room and opened the shutters on one of her windows. Before her lay a courtyard and a stable where the men of the King’s Own kept their horses. The torches that lit the courtyard were nearly out. The pearly radiance that came to the eastern sky in the hour before dawn fell over snow, stable, and the edges of the palace wall beyond.

The scant light showed a big girl of eighteen, broad-shouldered and solid-waisted, with straight mouse-brown hair cut short below her earlobes and across her forehead. She had a dreamer’s hazel eyes, set beneath long, curling lashes, odd in contrast to the many fine scars on her hands and the muscles that flexed and bunched under her nightshirt. Her nose was still unbroken and delicate after eight years of palace combat training, her lips full and quicker to smile than frown. Determination filled every inch of her strong body.

Motion in the shadows at the base of the courtyard wall caught her eye. Kel gasped as a winged creature waddled out into the open courtyard, as ungainly on its feet as a vulture. The flickering torchlight caught and sparked along the edges of metal feathers on wings and legs. Steel legs, flexible and limber, ended in steel-clawed feet. Between the metal wings and above the metal legs and feet was human flesh, naked, hairless, grimy, and in this case, male.

The Stormwing looked at Kel and grinned, baring sharp steel teeth. His face was lumpy and unattractive, marked by a large nose, small eyes, and a thin upper lip with a full lower one. He had the taunting smile of someone born impudent. ‘Startle you, did I?’ he enquired.

Kel thanked the gods that the cold protected her sensitive nose, banishing most of the Stormwing’s foul stench. Stormwings loved battlefields, where they tore corpses to pieces, urinated on them, smeared them with dung, then rolled in the mess. The result was a nauseating odour that made even the strongest stomach rebel. Her teachers had explained that the purpose of Stormwings was to make people think twice before they chose to fight, knowing what might happen to the dead when Stormwings arrived. So far they hadn’t done much good as far as Kel could see: people still fought battles and killed each other, Stormwings or no. Tortall’s Stormwing population was thriving. But this was the first time she’d seen one on palace grounds.

Kel glared at him. ‘Get out of here, you nasty thing! Shoo!’

‘Is that any way to greet a future companion?’ demanded the Stormwing, raising thin brown brows. ‘You people are getting ready to stage an entertainment for our benefit up north. You’ll be seeing a lot of us this year.’

‘Not if I can help it,’ Kel retorted. Grimly she walked across her dark room, stubbing her toe on the trunk at the foot of her bed. She cursed and limped over to the racks where she kept her weapons. When she found her bow and a quiver of arrows, she strung the bow and hopped back to her window. She placed the quiver on her window seat and put an arrow on the string. Outside, the courtyard was empty. The Stormwing’s footprints in the snow ended right under Kel’s window.

Scowling, Kel looked up and around. There he was, perched on the peak of the stable roof, a steel-dressed portent of war. Kel raised her bow. She wouldn’t actually kill the creature, just make him go away.

He looked down at her, cackled, and took to the air, spiralling out of Kel’s range. He flipped his tail at her three times in a mockery of a wave, then sailed away over the palace wall.

‘I hate those things,’ grumbled Kel as she removed the bowstring. The thought of anyone’s dead body providing Stormwings with entertainment gave her the shudders. And she knew chances were good that she might become a Stormwing toy very soon.

There was no point in going back to sleep now. Instead, Kel cleaned up, dressed, and took down her glaive. It was her favourite weapon, a wooden staff five feet long, filled in iron, cored with lead, and capped by eighteen inches of curved, razor-sharp steel. Banishing all thoughts, opening herself to movement, she began the first steps, thrusts, lunges, and spins of the most complicated combat pattern dance she knew.

Her dog, Jump, grumbled and crawled out of bed. He leaped out of one of the open windows to empty his bladder. The sparrows, fluffed up and piping their own complaints, fluttered outside to visit their kinfolk around the palace.

Raoul of Goldenlake and Malorie’s Peak, Kel’s former knight-master and present taskmaster, was not in his study when Kel arrived there after breakfast. Another morning conference, she thought, and sat down with chalk and slate to calculate the number of wagons they’d need to move the King’s Own’s supplies up to the Scanran border. She was nearly done when Lord Raoul came in, a sheaf of papers in one ham-sized fist.

‘We’re in it for certain,’ he told Kel. He was a big man, heavily muscled from years of service with the Own. His ruddy face was lit with snapping black eyes and topped with black curls. Like Kel, he was dressed for comfort in tunic, shirt, breeches, and boots in shades of maroon, brown, and cream. He slammed his bulk into one of the chairs facing the desk where she worked. ‘You know, I thank the gods every day that Daine is on our side,’ he informed Kel. ‘If ever we’ve needed a mage who can get animals to spy and carry messages, it’s now.’

Kel nodded. Unlike other generations, hers did not have to wait for Scanran information until the mountain passes cleared each year. Daine, known as the Wildmage, shared a magical bond with animals, one that endured even when she was not with them. For three years her eagles, hawks, owls, pigeons, and geese had carried tidings south while the land slept through winter snows, allowing Tortall to prepare for the latest moves in Scanra.

‘Important news, I take it?’ Kel asked.

‘I’m glad you’re sitting down,’ Raoul said. ‘The Scanrans have a new king.’

Kel shrugged. Rulership in Scanra was always changing. The clan lords were unruly and proud; few dynasties ruled for more than a generation or two. This one hadn’t even lasted a full generation. She was surprised that Raoul would be concerned about yet another king on what was called the Bloody Throne. Far more worrisome was the threat that had emerged a couple of years before, a warlord named Maggur Rathhausak. He had studied combat in realms with real armies, not raiding bands. Serving as one clan’s warlord, he had conducted enough successful raids in Tortall that other clans had asked him to lead their fighters as well. With more warriors he had won more victories and brought home more loot and slaves, enough to bribe other clans to swear allegiance to him. It was Rathhausak that the Tortallans prepared to fight this year, not the ruling council in Hamrkeng or its king.

‘So they’ll be fighting each other all summer instead of …’ Kel let her voice trail off as Raoul shook his head. ‘Sir?’ she asked, unsure of his meaning.

‘Maggur Rathhausak,’ Raoul told her. ‘He’s brought all Scanra’s clans into his grip. This year he’ll have a real army to send against us. A real army, trained for army-style battle, instead of a basketful of raiding parties. Plus however many of those killing devices he can send along to cut our people to shreds. The messages from the north report at least fifty of the things, wrapped up in canvas and waiting for the spell that will make them move again.’

Kel set her chalk and slate down. Then she swallowed and asked, ‘The council let Maggur take over?’

‘They weren’t given a choice. Maggur had nine clans under his banner last year. The word is he smuggled them into the capital at Hamrkeng after the summer fighting and, well, persuaded all the clans to make him king.’ Raoul tossed his papers on the desk with a sigh. ‘We knew it was to be war this summer, but we thought we’d be facing half the warriors in the country, not all. Jonathan’s sending messengers out to all the lords of his council. He wants our army to start north as soon as we can manage it.’ The big man grinned, exposing all his teeth, wolflike. ‘We’ll prepare the warmest reception for our northern brothers that we can. Once they cross our border, they’ll think they’ve marched into a bake oven, by Mithros.’

Kel stared blindly at the papers Raoul had just thrown onto the desk. It was decision time: await the crown’s orders, or slip away to wait for the northern passes to clear so she could track down the Nothing Man? She didn’t know enough; that was the problem. She needed information, and there was only one place she could think of to get it. ‘Sir, has anybody ever entered the Chamber of the Ordeal a second time?’

For a moment the only sound was the crackle of the fire in the hearth. Raoul froze. At length he said, ‘I must tell the bathhouse barber to clean my ears tomorrow. I could have sworn you just asked me if anyone has ever returned to the Chamber of the Ordeal. That’s not funny, Kel.’

‘I didn’t mean to be funny, sir,’ she replied. Shortly after her Ordeal and knighthood, Raoul had commanded her to address him by his first name, but ‘sir’ was as close as she could bring herself. She clenched her hands so he couldn’t see them shake. ‘I’m serious. I need to know if you’ve ever heard of anyone going back there.’

‘No,’ Raoul said firmly. ‘No one’s been mad enough to consider it. Most folk can tell if once is more than enough. Why in the name of the Great Mother Goddess do you ask?’

Kel swallowed. If he didn’t like her question, he really wouldn’t like what she was about to say. ‘I need to talk to it.’

Raoul rubbed his face with one hand. ‘You need to talk to it,’ he repeated.

Kel nodded. ‘Sir, you know me,’ she reminded him. ‘I wouldn’t ask anything silly, not when you bring such important news. But I have to know if I can enter the Chamber again. I need to find something out.’

‘You’re right, I do know you,’ Raoul said glumly. ‘No, no, you wouldn’t jest at a time like this. I’m afraid you’re stuck, though. No one has been allowed back inside that thing in all history. No one would ever want to go back. You’ll just have to settle for what you got in there the first time.’ He held her questioning eyes with his own anxious ones.

Kel wished that she could explain, but she couldn’t. Knights were forbidden to tell what had taken place during their Ordeal. ‘I didn’t mean to worry you, sir,’ she told him at last.

Raoul scowled at her. ‘Don’t frighten me like that again. I’ve put far too much work into you to see you go mad now.’ He looked around. ‘What were we doing last?’

‘Wagon requisitions, sir,’ she replied as she held up her slate.

He took it and reviewed her numbers. ‘Let’s finish this now. I won’t be able to work on them this afternoon – the council will be meeting.’

Kel fetched the papers he needed. ‘There was a Stormwing in the courtyard this morning,’ she remarked as she laid them out. ‘I think he already knows how bad things will be this summer.’

Raoul grunted. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised. They probably smell it. Now what’s this scrawl? I can’t read Aiden’s writing.’ They spent the rest of the morning at work, sorting through the endless details that had to be settled before the men of the King’s Own rode north to war.

After lunch Kel saw to her horses, stabled in the building the Stormwing had turned into his momentary perch. There were ostlers, whose job it was to mind the hundreds of horses kept at the palace, but Kel preferred to see to her riding mount, Hoshi, and her warhorse, Peachblossom, herself. The work was soothing and gave her time to think.

Jump watched as she tended the horses. The scruffy dog had put in an appearance at Kel’s side about mid-morning, clearly recovered from having his morning’s sleep interrupted by Kel and a Stormwing.

Jump was not a typical palace dog, being neither a silky, combed, small type favoured by ladies nor a wolf- or boar-hound breed prized by lords. Jump was a stocky, short-haired dog of medium size, a combat veteran. His left ear was a tatter. His dense fur was mostly white, raised or dented in places where it grew over old scars. Black splotches covered most of the pink skin of his nose, his only whole ear, and his rump. His tail was a jaunty war banner, broken in two places and healed crooked. Jump’s axe-shaped head was made for clamping on to an enemy with jaws that would not let go. He had small, black, triangular eyes that, like those of any creature who’d spent a lot of time with Daine the Wildmage, were far more intelligent than those of animals who hadn’t.

‘I need more information,’ Kel murmured to Jump as she mucked out Hoshi’s stall. ‘And soon, before the king orders us out with the army. I certainly can’t tell the king I won’t go. He’ll want to know why, and I can’t talk about what happened during my Ordeal.’

Jump whuffed softly in understanding.

Her horses tended, Kel reported to a palace library. There, she and the other knights who were her year-mates (young men who had begun their page studies when she had) practised the Scanran tongue. Many Scanrans spoke Common, the language used in all the Eastern Lands between the Inland Sea and the Roof of the World, but the study of Scanran would help those who fought them to read their messages and interpret private conversations.

After lessons Kel spent her time as best she could. She cared for her weapons and armour, worked on her sword and staff skills in one of the practice courtyards, ate supper with her friends, and finally read in her room. When the watch cried the time at the hour after midnight, she closed her book and left her room, with Jump at her heels.

The palace halls were deserted. Wall torches in iron cressets burned low. Kel did not see another soul. In normal times the nobility would be at parties; not this year. The coming war dictated their hours now. They retired before midnight after evenings spent figuring what goods and labour they could spare for the coming bloody summer. Even the servants, always the last to sleep, were abed. It was like walking in a dream through an empty palace. Kel shivered and grabbed a torch from the wall as she passed the Hall of Crowns.

It was a good idea. No lights burned in the corridor that led to her destination. The Chapel of the Ordeal was used only at Midwinter, when squires took their final step to a shield. Now it was shut and ignored. Still, the chapel’s door was never locked. Kel shut it once she and Jump were inside. There was no need to post a guard: over the centuries, thieves and anyone else whose motives were questionable had been found outside the chapel door, reduced to dried flesh and bone by the Chamber’s immeasurable power.

Once a year during her term as a squire, Kel had visited the Chamber to try her will against it. On those visits she had confined her encounter with it to touching the door. To converse with the thing, she suspected that she had to go all the way inside once again.

Kel set her torch in a cresset near the altar. Its flickering light danced over the room: benches, the plain stone floor, the altar with its gold candlesticks and cloth, and the large gold sun disc, the symbol of the god Mithros. To the right of the disc was the iron door to the Chamber of the Ordeal.

At first Kel could not make her legs go forward. She had never had a painless experience from the Chamber. In the grip of its power she had lived through the death of loved ones, been crippled and useless, and been forced to stand by as horrors unfolded.

‘This is crazy,’ she told Jump. The dog wagged his tail, making a soft thwapping noise that seemed loud in the quiet chapel.

‘You wait here,’ Kel told him. She ordered her body to move. It obeyed: she had spent years shaping it to her will. She stepped up to the iron door. It swung back noiselessly into a small, dark room with no windows or furnishings of any kind.

Kel trembled, cold to the bone with fear. At last she walked into the Chamber. The door closed, leaving her in complete darkness.

She stood on a flat, bare plain without a tree, stream, or animal to be seen. It was all bare earth, with no grass or stones to interrupt the boring view.

‘What is this place?’ she asked aloud. Squires were forbidden to speak during the Ordeal, but surely this was different. In an odd way, this was more like a social visit than an Ordeal. ‘Do you live here?’

It is as close as your human mind can perceive it. The Chamber’s ghostlike voice always spoke in Kel’s head without sounding in her ears.

Kel thrust her hands into her pockets. ‘I don’t see why you haven’t done something with it,’ she informed the Chamber. ‘No furnishings, no trees, or birds … If you’re going to bring people here, you ought to make things look a bit nicer.’

A feeling like a sigh whiffled through Kel’s skull. Mortal, what do you want? demanded the Chamber. Its face – the face cut into the keystone over the inside of the iron door – formed in the dirt in front of her. It was lined and sexless, with lips so thin as to be nearly invisible. The deep-set eyes glinted yellow at Kel. The task you have been set is perfectly clear. You will know it when you find it.

Kel shook her head. ‘That’s no good. I must know when and where. And I’d like another look at the little Nothing Man, if you please.’

Instantly the dirt beneath her was gone, the air of the plain turned to shadow, as if she dreamed again. She fell like a feather, lightly, slipping to and fro in the wind. When she landed, she was set on her feet as gently and tidily as she could have hoped.

During her Ordeal she had seen the Chamber’s idea of her task as an image on the wall in a corner of the grey stone room. Now she was living the image, standing in a room like a cross between a smithy and a mage’s studio. Unlike her vision and the dreams that had followed it, this place was absolutely and completely real. Behind her, a forge held a bed of fiery coal. An anvil and several other metalworking tools lay nearby. Along one wall stood open cupboards filled with dried herbs, crystals, books, tools, glass bottles, and porcelain jars. Between her and the cupboards was a large stone worktable with gutters on the sides. It was covered with black stains. To her left was another, smaller, kitchen-style hearth set into the wall. Its fire had burned out.

Kel inhaled. Scents flooded her nose: lavender, jasmine, and vervain; damp stone; mould; and under it all, the coppery hint of old blood.

There he was, scrawny and fidgeting as he stood beside the worktable chewing a fingernail. Kel shrank back.

It is safe, the Chamber said. He cannot see you.

The Nothing Man was just as she remembered, just as he’d been in all those dreams she’d had since Midwinter. There was nothing new to be learned from this appearance.

In the shadows to Kel’s right, metal glinted. She gulped and backed up as a killing device walked out of the shadows, dragging a child’s body. The devices also looked just as she remembered, both from her Ordeal and from a bloody day the previous summer when she and a squad of men from the King’s Own had managed to kill one. The device was made to give anyone who saw it nightmares. Its curved black metal head swivelled back and forth, with only a thin groove to show where a human neck would be. Long, deep pits served as its eyes. Its metal visor-lips could pop open to reveal clashing, sharp steel teeth. Both sets of limbs, upper and lower, had three hinged joints and ended in nimble dagger-fingers or -toes. Its whiplike steel tail switched; the spiked ball that capped it flashed in the torchlight.

The little man flapped an impatient hand. The machine left the room through a door on Kel’s right, towing its pitiful burden.

Moments after it was gone, a big man came in. He was tall enough to have to stoop to get through the door. His greying blond hair hung below his shoulders. A close-cropped greying blond beard framed narrow lips. Brown eyes looked out over a long, straight nose. He wore a huntsman’s buff-coloured shirt, a brown leather jerkin, and brown leather breeches stuffed into calf-high boots. At his belt hung axe and dagger. He stopped in front of the Nothing Man and hooked his thumbs over his belt.

‘We just shipped twenty more to King Maggur. That leaves you with ten, Master Blayce,’ he said, his voice a deep baritone. He spoke Scanran. ‘Barely enough to make it to spring.’

Blayce, Kel thought intently.

‘It’ll do, Stenmun,’ Blayce replied. His voice was a stumbling whine, his Scanran atrocious. ‘Maggur knows—’

Suddenly Kel was back in the Chamber’s dreary home. She spared a glance around – did she see a tree in the distance? – before she turned to glare at the face in the pale stone. ‘Where is he?’ she demanded. ‘Look, Maggur Rathhausak is king now. He’ll march once Scanra thaws out. The king will be sending the army – that includes me – north as soon as he can. You have to tell me where to look so I can leave before that happens! If I go now, I won’t be disobeying the king. We mortals call that treason.’

I cannot, the Chamber said.

Kel disagreed with a phrase she had learned from soldiers.

I am not part of your idea of time, the Chamber told her. Apparently her language had not offended it. You mortals are like fish swimming in a globe of glass. That globe is your world. You do not see beyond it. I am all around that globe, everywhere at once. I am in your yesterdays and tomorrows just as I am in your today, and it all looks the same to me. I only know you will find yourself in that one’s path. When you do, you must stop him. He perverts life and the living. That must not continue. Its tone changed; later, Kel would think the thing had been disgruntled. I thought you would like the warning.

Kel crossed her arms over her chest, disgusted. ‘So you don’t know when I’ll see that piece of human waste. The Nothing Man. Blayce. Or that warrior of his, what’s his name? Stenmun.’

No.

‘And you don’t know where they are.’

Your ideas of countries and borders are meaningless to me.

‘But you thought I’d be happy to know that the one who’s making the killing devices, who’s murdering children, will come my way. Sometime. Someplace.’

You must right the balance between mortals and the divine, the balance that is my reason to exist. That creature defies life and death. I require you to put a stop to it. Your satisfaction is not my concern.

Kel wanted to scream her frustration, but years of hiding her emotions at the Yamani court stopped her. Besides, screaming was a spoiled child’s response, never hers. And as a knight at eighteen, she was supposed to act like an adult, whatever that meant. She tried one last time. ‘The sooner, the better.’

You will meet him, and you will fix this. Now go away. The iron door swung open.

‘Can I at least talk to people about it? Tell them that you showed me this?’ she demanded.

If you think they will believe you. You are not considered to be a seer or a mage, and your own mages know the name of Blayce already. They just cannot find him.

Kel responded with another word learned from soldiers and walked out of the Chamber.

The news of Maggur’s coronation in Scanra sped the process of gathering Tortallan fighters and supplies. Preparation for war filled the hours at the palace. Every knight not already assigned was summoned to the throne room. The king and queen told the knights that they were now in military service to the crown for the length of the war and gave them their instructions. Kel remained under Lord Raoul’s orders for the moment. She readied her own gear as she helped him assemble all that his men would require.

Weather-mages turned their attention to the northern mountains. A week later they told the monarchs that while it would be hard going, Tortall’s army could move out. The next day the warriors readied for departure in the guest-houses and fields around the Great Road North, assembling knights, men of the King’s Own, six Groups of the Queen’s Riders, ten companies of soldiers from the regular army, and wagon after wagon of supplies. It would take three times longer to reach their border posts than if they waited another two weeks for the sleet, snow, and mud of the northern roads to clear. But it would be worth the trouble if they could be in place when the Scanrans came to call.

At dawn on the first morning of the last week of March, the army’s vanguard of knights and lords of the realm set off for the border. Kel rode Hoshi, with Jump in one of her saddlebags and sparrows clinging to every part of her and her equipment. On the bluffs north of the city she murmured a soft prayer to Mithros for victory and one to the Goddess for the wounded to come. She was starting a prayer to Sakuyo, the Yamani god of jokes and tricks, when Lord Raoul snarled a curse. She looked at him, startled: he was riding just in front of her with the King’s Champion, Alanna, the realm’s only other lady knight, and Duke Baird of Queenscove, chief of the realm’s healers and father of Kel’s best friend, Neal. Everyone else turned in their saddles to see what could make the easygoing Raoul so angry. He was pointing a finger that shook with rage.

Below them lay the city of Corus, sprawled on both sides of the Olorun River. Across from them on the high ground south of the river lay the royal palace, its domes and towers clear in the growing light of sunrise.

Above the palace flew Stormwings by the hundreds, males and females, like a swarm of hornets. The sun bounced off their steel feathers and claws, shooting beams at anyone who looked on. Higher the Stormwings rose. Slowly, lazily, they wheeled over the capital city, then streamed north over the army as if they pointed the way to battle.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_79dcc6e1-bc08-5a9a-9194-72e455031ac1)

TOBE (#ulink_79dcc6e1-bc08-5a9a-9194-72e455031ac1)

Riding with Third Company of the King’s Own, Kel had spent plenty of time slogging through mud and slush. She was used to that. It was her frequent riding companions, Prince Roald and Sir Nealan of Queenscove, who sometimes made her wish her family had stayed in the Yamani Islands. The bitter conditions were echoed by the moods of both young men. They were betrothed and in love with the women they were to marry. They moped. Kel tried to make them think of other things, but the moment conversation lagged, they returned to the contemplation of their Yamani loved ones.

Kel felt sorrier for Prince Roald. Two years older than Kel, the prince was to have married Princess Shinkokami in mid-May, before the arrival of word that Maggur had taken the Scanran throne. Instead of an expensive ceremony, he and Shinko had decided to put their wedding off. Both showed cheerful faces to the public, saying they had traded rose petals for arrows to arm their soldiers, but to their close friends their disappointment was plain.

Neal, usually dramatic in love, would not talk about his lady, Yukimi, at all. It was such a change from his normal behaviour that Kel was convinced he truly loved her Yamani friend. Before, he’d made high tragedy of his beautiful crushes and his own heartbreak, but not this time. Not over a plump and peppery Yamani.

With Roald on one side and Neal on the other, Kel had to wonder about her own sweetheart, Cleon of Kennan. They hadn’t seen each other in over a year. A knight two years older than Kel, he was stuck in a northern border outpost, where he had been assigned to teach the locals how to defend themselves. He’d been unable to get or send letters during both winters. Had he forgotten her? She wasn’t even sure if he knew she’d survived her Ordeal.

I’ll write to him when I know where I’m to be posted, she promised herself. Maybe we’ll even be assigned to the same place. I’d like that.

She smiled at the idea. They’d never got much time alone: something had always interrupted. Perhaps by now he’d be over his impractical idea that he wanted them to marry before they made love, as proper young noblemen did with proper young noblewomen.

Nothing would come of waiting to marry. Years ago, Cleon’s mother had arranged his marriage to a young noblewoman with a fine dowry. Cleon thought that, given time, he might convince his mother that Kel would make a better wife. Kel was not so sure. As the youngest daughter of a family that was not wealthy, her dowry was small. She was also not ready to marry. She’d only just earned her shield; there was so much to do before she could think of settling down. Cleon loved her, wanted to have children by her. She wanted love and children, too – someday. Not now. Not with Scanra ready for all-out war against Tortall. Not with a future that included Blayce the Nothing Man.

Romance wasn’t the only thing to think about, but it was more pleasant than reality. Knights used their powerful mounts and the wagons of armour, tack, and weapons to break trail through snow and ice, clearing the way for the foot soldiers of the regular army. It was slow going.

At least Peachblossom, Kel’s infamous, temperamental warhorse, behaved. He was a strawberry roan: reddish hide flecked with white, and red-brown stockings, face, mane, and tail. Eight years with Kel had cured him of his tendency to attack others. It was only when they got held up and he was bored that Kel caught him eyeing Neal, his favourite target. When that happened, Kel excused herself and rode ahead to join Lord Raoul or Lady Alanna.

To everyone’s relief, the countryside offered dry quarters for the military. War parties rode north so regularly that local farmers made extra money by letting soldiers bed down in their barns. Officers and knights slept at crown wayhouses. These large inns provided snug quarters and plentiful food, doubly welcome after a day in the cold and wet. Often villages encircled the wayhouses, offering shops and more places to find shelter for the night.

Each day as she walked into the comfort of a wayhouse, Kel hoped the Stormwings that flew above the army found only cold, damp perches for the night. She wished them ice-covered wings and frostbite in their human flesh. Each morning she saw the flash of their steel feathers and heard their jeering calls as the army marched on. And each morning their numbers were as great as they’d been the day before.

Kel had been on the road ten days when they stopped in Queensgrace for the night. The Jug and Fire was the largest of three wayhouses there, so large that even first-year knights had rooms to themselves. By the time Kel got to her room after tending her mounts, a hot bath awaited her. She soaked until the mud and ice were out of her pores, then dried herself, dressed in clean clothes, and went down to eat with her friends. Except for the conversation of the villagers, who had come to see the nobles, the only sounds were the clatter of cutlery and occasional quiet requests for butter, salt, or the refill of a tankard.

Kel finished and thrust her plate back with a grateful sigh. A bowl of winter fruit sat on the table she shared with Neal and her year-mates, reminding her of her horses. They deserved a treat after that day’s work. She scooped up two apples and excused herself.

A shortcut through the kitchens meant she was outside for only a couple of yards rather than the width of the large courtyard. It also meant she entered the stable unnoticed, through a side door rather than the main entrance.

The long building lay in shadow, the lanterns being lit only around the front entrance. The horses dozed, glad to be under shelter. Kel was letting her eyes adjust to what light there was when she heard the hard whump! of leather on flesh, and a child’s yell.

‘I tol’ ye about foolin’ around the horses when there’s work to be done,’ a man snarled. He stood two rows of stalls over from Kel, his back to her. He raised his right hand; a leather strap dangled from his fist. ‘You’re supposed to be in that kitchen washin’ up, you thankless rat turd!’ Down plunged the hand; again, the sound of a blow as it struck, and a yelp.

Kel strode quickly but silently across the distance between her and the man. The next time he drew his arm back, she seized it in one iron-fingered hand, digging her nails deep into the tender flesh between the bones of his wrist.

‘You dare—’ the innkeeper growled, turning to look at her. He was bigger than Kel, unshaven and slope-shouldered. His muscle came from hoisting kegs and beating servants, not from eight years of combat training. His eyes roved from Kel’s set face to her personal badge, a grey owl on a blue field for House Mindelan, and below it, Kel’s own ornament of crossed glaives in cream lined with gold. There were two stripes of colour for the border – the inner ring cream, the outer blue. They meant she was a distaff, or female, knight.

The innkeeper knew who she was. That information spread quickly everywhere Kel went. ‘This’s no business of yours, lady,’ he said, trying to yank free of her. ‘Look, he’s allus ditchin’ chores, never minds his work. Likely he’s out here to steal. Leave me deal with him.’

The boy, who sat huddled in a corner of the empty stall, leaped up and spat at the innkeeper’s feet. He then bolted across the aisle and into the next stall.

‘No!’ shouted Kel, but it was too late. The boy slipped in manure and skidded to a halt under Peachblossom’s indignant nose. ‘Peachblossom, leave him be! Boy, he’s mean, get out now!’ While the gelding had learned to live near others like a civilized creature, he could not be approached by just anyone.

Peachblossom lowered his muzzle to sniff the ragged scrap of humanity before him. The boy waited, perfectly still, as the big gelding whuffled through his guest’s hair and under his arms, then gently lipped the boy’s nose. Kel waited, horrified, for the shriek of agony that would come when Peachblossom bit.

The shriek never came. Peachblossom continued to inspect the newcomer inch by inch.

‘Milady, you oughtn’t go between a man an’ his servants,’ the innkeeper said, trying to be agreeable. ‘I’ll never get him to do proper work now.’ He tried to wrest his hand from Kel’s grip. She tightened her muscles, digging even deeper into his wrist. He couldn’t shake her loose, and he was afraid to anger a noble by striking her.

As he struggled, Kel inspected the skinny urchin who had so bewitched Peachblossom. The shadows around the lad’s deep-set blue eyes were not all from lack of sleep. There was an old black eye, a newer bruise on one cheekbone, and a scabbed cut across his sloping nose. The boy glared at the innkeeper, his chin square and determined. There were new welts on his arms and back visible through holes in his shirt. A slit in half-rotten breeches revealed a long, recent bruise. He was barefoot, his feet red and chapped. His matted hair might be blond if it were clean.

As she watched, he reached up and gently stroked Peachblossom’s muzzle.

Horse magic, Kel thought. It has to be. And this idiot treats a lad that useful like a whipping boy. She looked at the innkeeper. Fury boiled in her veins, but she kept her face calm, allowing no emotion to escape. It was a skill she had perfected. ‘Tell me he is not your son,’ she said mildly.

The innkeeper made a face. ‘That stray pup? We took him in of charity, fed and clothed him, and gave him a home. He works here. I’ve the right to discipline him as I please.’

‘You would lose that right if he weren’t forced to depend on you. He’d be long gone.’ Her voice was still pleasant. Her inner self, the sensible part, shrieked that she had no business doing what she was about to do. She was on her way to a war; boys took much more looking after than sparrows, dogs, or horses.

‘Let him starve? That would be cruel,’ the man insisted. Looking at him, Kel realized that he believed it. ‘He’s got no family. Where can he go?’ demanded the innkeeper. ‘But he can’t just leave work. Boys need discipline. Elsewise he’ll go as bad as the feckless Scanran slut that whelped him an’ left him on the midwife’s step.’

‘If he was left with the midwife, how did he come to you?’ Kel asked.

‘She died. We bid for the boy’s indenture. Paid for seven years, we did. Been more trouble than he’s worth, but we’re gods-fearin’ folk, an’ charity be a virtue.’ The man looked piously towards the ceiling, then at Kel. ‘Forgive my sayin’ so, milady, but this be no affair of yours.’

Kel released him. ‘I think the district magistrate would find your treatment of this boy to be very much his affair,’ she informed the man. ‘Under the law indentured servants have some rights. What did you pay when you bid for his services?’

‘You can’t buy his contract,’ protested the innkeeper. ‘It ain’t for sale.’

Kel wrapped both hands in his tunic and dragged his face down to hers. ‘Either tell me, or I visit the magistrate tomorrow, and you’ll have no say in the matter,’ she informed him. ‘This boy is an indentured servant, not a slave. Accept my coin now, or have him taken with no payment tomorrow, it’s all the same to me.’

When the innkeeper looked away, she released him, knowing she had won.

‘Two copper nobles,’ growled the man.

‘One,’ said the boy grimly. ‘Only one, an’ I been workin’ for ’im for three year.’

‘Lyin’ little rat!’ snapped the innkeeper, darting to Peachblossom’s stall. The gelding lunged without touching the boy at his feet and snapped, teeth clicking together just in front of the innkeeper’s face. The man tried to run backwards and fell, ashen under his whiskers.

Kel looked in her belt purse. She wouldn’t have paid a copper bit for ten boys in that condition, but she wanted to be rid of the innkeeper. She held up two copper nobles. ‘I’ll take his indenture papers before you have this. Get them, right now.’

The man fled the stable.

Kel sighed and walked into Peachblossom’s stall. ‘You’re getting slow,’ she informed the gelding. ‘Time was you’d have had his whole arm in your teeth.’

Peachblossom snorted in derision and backed up.

‘Not that I’d mind,’ Kel admitted, looking at the lad. ‘A good bite would keep him from hitting people with that arm for a while. But I suppose it would make a fuss.’ She propped her hands on her hips, disgusted with herself. Why had she done this?

Even as she asked herself if she’d run mad, she knew that she couldn’t have done anything else.

Kel inspected the boy. Clothes, particularly shoes, were required. His present rags would have to be burned. He needed a bath and a haircut. He probably had lice. Shaving his head and scrubbing him with lice-killing soap would eliminate that problem. He didn’t look old enough to need shaving anywhere else. And he needed a healer.

Kel looked over at Hoshi’s stall, where Jump gnawed a bone. Chances were that it had not been intended for his supper, since there was quite a bit of meat on it. She only hoped the inn’s staff didn’t know who the thief was.

‘Jump, will you get Neal, please?’ Kel asked the dog. Jump thrust his bone under the straw, then trotted out of the stable. The boy followed the dog’s movements with wide eyes but made no comment that might draw Kel’s attention.

‘What’s your name?’ she asked. ‘And how old are you?’

The boy retreated under Peachblossom’s belly. He watched her warily from between the gelding’s forelegs. After a moment he said, ‘Tobe, miss. Tobeis Boon. I think I’m nine.’

Kel repeated, ‘Boon?’

The boy nodded. ‘Auld Eulama said I musta been a boon to someun, though she didn’t know who.’

‘Eulama?’ asked Kel.

‘Midwife as reared me, best’s she knowed.’

Kel scratched her head. ‘Whose opinion is that?’ she enquired, intrigued by his frank way of talking. ‘That she did the best she knew?’

‘All Queensgrace, lady. They all say’t. Way they talk, it din’t do me much good.’ It seemed Tobeis – Tobe – was as intrigued by Kel as she was by him. He inched forward.

Kel indicated the boy’s guardian. ‘It’s not so long ago that I convinced him not to savage everyone in reach. I’ve known him eight years. I was sure he’d kill you.’

‘Aww, he’s a good un.’ Tobe wrapped a casual hand around as much of Peachblossom’s right foreleg as he could manage. ‘Ain’t nobody likes Alvik – me master there.’

Here came Alvik himself with a writing board, a quill, an ink pot, a sheet of grimy paper, sealing wax, and a candle. Kel briskly signed Tobe’s indenture papers, handed over the coins, and watched the innkeeper also sign, then seal the document. As soon as Kel had the completed bill of sale in hand, Alvik fled. He passed Neal and Jump on their way in.

‘You know, Mindelan, our lives would be easier if the dog just broke down and talked,’ Kel’s friend announced. ‘I was winning that card game.’ He glared down at Jump. ‘There was no need to grab me.’

Kel smiled. ‘If you’re not bleeding, he was being nice, and it’s not fair for you to play cards with ordinary folk.’ To Tobe she explained, ‘He remembers all the cards dealt.’

Neal looked to see who she spoke to, and stared. ‘Kel, that monster has a boy under his belly.’

‘That monster hasn’t touched him,’ replied Kel. Neal had every reason to expect the worst of the big gelding. ‘Will you take a look at the boy? Tobe – Tobeis Boon, this is my friend Neal.’ She didn’t give Neal’s titles, not wanting to make the boy uncomfortable. ‘Tobe, my friend is a healer. I want him to look at you.’

‘Not while he’s in there,’ protested Neal.

At the same time the boy said, ‘He’s no healer, just some noble.’

Neal glared at Tobe. ‘I’m a healer and a noble.’ He looked at Kel. ‘What have you done now, Mindelan?’

Kel shrugged. ‘I need a servant. Tobe seemed to want a change, so I hired him away from the innkeeper.’

‘You mean he’s another of your strays,’ Neal pointed out. ‘Didn’t that griffin teach you anything?’

‘Griffin?’ Tobe asked, scooting a little forward of Peachblossom’s legs. ‘You saw a griffin?’

Kel smiled. ‘I’ll tell you about it if you’ll let Neal have a look at you.’

Tobe eyed Neal with considerable suspicion. ‘Folk like him don’t touch the likes of me.’

‘If you knew how I spent my squiredom, you’d know the likes of you are most of what I ended up touching,’ Neal informed him. ‘I can get rid of your lice and fleas,’ he added as Tobe scratched himself.

‘Cannot,’ retorted the boy.

‘Can too,’ Neal replied. ‘The handiest spell I ever learned.’

Convinced that Neal would talk the boy around, Kel went to see about having a hot bath drawn and carried up to her room.

‘Miss, you shouldna bother with that un,’ the maid she paid for the service commented. ‘He’s a gutter rat, as like to bite a helpin’ hand as not.’

Thinking of Peachblossom and the baby griffin she’d once cared for, Kel replied, ‘If he does, it won’t be the first time.’

When Neal brought Tobe to her room, Kel was just donning the oiled canvas cloak and broad-brimmed hat she used to keep off the rain. Under the cloak she wore a quilted coat made by her former maid, Lalasa, now a dressmaker. Lalasa had spared no effort on the coat for the mistress who had given her a start in business. By the time Kel had tied the cloak around her neck, she was sweating.

‘Here he is.’ Neal pushed open Kel’s door to admit Jump and Tobe. ‘Did you order supper for him?’

‘I remember that much from my own healings, thank you,’ Kel replied. ‘I appreciate your seeing to him, Neal.’

Her friend waved a hand in dismissal and left, closing the door. Kel regarded her new servant. ‘You see that?’ She pointed to the tub that sat squarely in front of the hearth. ‘It’s a bath. You climb in and you don’t climb out and eat before you’re clean. Scrub all over, understand?’ Hanging on to Tobe, she saw that Neal had done well: the boy’s weals and scabbed-over cuts showed now as pink, healthy, new skin. ‘There’s soap in that bowl. Use it,’ she continued. ‘The little pick is to clean under your nails. Remember your hair, your ears, and your private parts.’ She released him.

The boy went to the tub, stuck a finger in the water, and glared at Kel. ‘It’s hot!’ he exclaimed.

‘Don’t expect hot baths every night,’ she told him, straight-faced. She could see that he was dismayed at the thought of washing in hot water. ‘But you’ll do this on your own, or I’ll do it for you, with a scrub brush. My servants are clean.’

Tobe hung his head. ‘Yes, lady.’

Kel pointed to the bed, where she had set out drying cloths and one of her spare shirts. ‘Dry with those and put that on for now,’ she said. ‘Don’t wear your old things.’

‘Not even me loincloth?’ he asked, horrified.

‘You’re getting fresh ones. Clean ones,’ she said, immovable. ‘I’m off to take care of that now. When you’re dry, wrap up in a blanket and look outside – the maid will leave a tray with your supper by the door. I got a pallet for you’ – she pointed to it, on the side of the hearth opposite the table – ‘so you can go to bed. You’ll be sleepy after a decent supper and Neal’s magicking.’

‘Yes, lady,’ replied the boy. He was glum but resigned to fresh clothes and a bath. He glanced around the room, his eyes widening at the sight of her glaive propped in a corner. ‘What pigsticker is that?’

Kel smiled. ‘It’s a Yamani naginata – we call it a glaive. I learned to use one in the Islands, and it’s the weapon I’m best with. Clothes, off. Bath, now, Tobe.’

He gaped, then exclaimed, ‘With a girl lookin’ on? Lady, some places a fellow’s got to draw the line!’

‘Very true,’ Kel replied solemnly, trying not to grin. ‘Don’t give Jump any food. He’s had one good meal already tonight.’

Jump, sprawled between the tub and the fire, belched and scratched an ear. His belly was plump with stolen meat.

Kel rested a hand on Tobe’s shoulder. ‘You’ll do as I ask?’

He nodded without meeting her eyes.

Kel guessed what was on his mind. ‘I’ll never beat you, Tobe,’ she said quietly. ‘Ever. I may dunk you in the tub and scrub you myself if I come back to find you only washed here and there, but you won’t bleed, you won’t bruise, and you won’t hobble out of this room. Understand?’

He looked up into her face. ‘Why do this, lady?’ he asked, curious. ‘I’m on’y a nameless whelp, with the mark of Scanra on me. What am I to the likes of you?’

Kel thought her reply over before she gave it. This could be the most important talk she would have with Tobe. She wanted to be sure that she said the right things. ‘Well, Peachblossom likes you,’ she answered slowly. ‘He’s a fine judge of folk, Peachblossom. Except Neal. He’s prejudiced about Neal.’

‘He just likes the way Neal squeaks when he’s bit,’ Tobe explained.

Kel tucked away a smile. It sounded like something Peachblossom would think. ‘And for the rest? I do it because I can. I’ve been treated badly, and I didn’t like it. And I hate bullies. Now pile those rags by the door and wash. The water’s getting cold.’ Not waiting for him to point out that cooler water didn’t seem so bad, she walked out and closed the door. She listened for a moment, waiting until she heard splashes and a small yelp.

He’s funny, she thought, striding down the hall. I like how he speaks his mind. Alvik didn’t beat that from him, praise Mithros.

At the top of the stairs, Kel halted. Below her, out of sight, she could hear Neal: ‘… broken finger, half-healed broken arm, cracked ribs, and assorted healed breaks. I’m giving your name to the magistrate. I’ll recommend he look in on you often, to see the treatment you give your other servants.’

‘Yes, milord, of course, milord.’ That was Innkeeper Alvik’s unmistakable voice, oily and mocking at the same time. ‘I’m sure my friend the magistrate will be oh so quick to “look in on” me, as you say, once you’re down the road. Just you worry about Scanra. They’ll be making it so hot for you there, you’ll be hard put to remember us Queensgrace folk.’

‘Yes, well, I thought of that,’ Neal said, his voice quiet but hard. ‘So here’s something on account, something your magistrate can’t undo.’

She heard a rustle of cloth. Alvik gasped. ‘Forcing a magic on me is a crown offence!’

‘Who will impress the crown more, swine? The oldest son of Baird of Queenscove, or you?’ asked Neal cruelly. ‘And did my spell hurt?’

‘Noooo,’ Alvik replied, dragging the sound out. Kel imagined he was checking his body for harm.

‘It won’t,’ Neal said. ‘At least, as long as you don’t hit anyone. When you do, well, you’ll feel the blow as if you struck yourself. Clever spell, don’t you think? I got the idea from something the Chamber of the Ordeal did once.’ Neal’s voice went colder. ‘Mind what I say, innkeeper. When you strike a servant, a child, your wife, your own body will take the punishment. Mithros cut me down if I lie.’

‘All this over a whore’s brat!’ snarled the innkeeper. ‘You nobles are mad!’

‘The whore’s brat is worth far more than you.’ Neal’s voice was a low rumble at the bottom of the stairs. ‘He’s got courage. You have none. Get out of my sight.’

Kel waited for the innkeeper to flee to his kitchen and Neal to return to the common room before she descended. It was useless to say anything to Neal. He would just be embarrassed that he’d been caught doing a good deed. He liked to play the cynical, heartless noble, but it was all for show. Kel wouldn’t ruin it for him.

It was a long ride to the wagonloads of goods for those made homeless by the Scanrans. Her lantern, hung from a pole to light Hoshi’s way, provided scant light as icy rain sizzled on its tin hood. Other riders were out, members of the army camped on either side of the road for miles. Thanks to their directions, Kel found the wagons in a village two miles off the Great Road North. They were drawn up beside one of the large, barnlike buildings raised by the crown to shelter troops and equipment on the road. In peaceful years local folk used the buildings to hold extra wood, grain, animals, and even people made homeless by natural disasters.

The miserable-looking guards who watched the wagons scowled at Kel but fetched the quartermaster. Once Kel placed money in his palm, the quartermaster allowed her to open the crates and barrels in a wagonload of boys’ clothes.

The wagon’s canvas hood kept off the weather as Kel went through the containers. Tobe looked to be about ten, but he was a runty ten, just an inch or two over four feet, bony and undersized from a life of cheap, scant rations. She chose carefully until she had three each of loincloths, sashes, shirts, breeches, and pairs of stockings, three pairs of shoes that might fit, a worn but serviceable coat, and a floppy-brimmed hat. If she was going to lead Tobe into battlelands, the least she could do was see him properly clothed. The army tailors could take in shirts and breeches to fit him properly; the cobblers could adjust his shoes. Once she had bundled everything into a burlap sack, Kel mounted Hoshi, giving a copper noble to the soldier who had kept the mare inside a shelter, out of the wet. As the rain turned to sleet, they plodded back to Queensgrace.

In Kel’s room, Tobe sat dozing against the wall, afloat in her shirt. When Kel shut the door, his eyes flew open, sky-blue in a pale face. ‘I don’t care if you was drunk or mad or takin’ poppy or rainbow dream or laugh powder, you bought my bond and signed your name and paid money for me and you can’t return me to ol’ Alvik,’ he told her without taking a breath. He inhaled, then continued, ‘If you try I’ll run off ’n’ steal ’n’ when I’m caught I’ll say I belong to you so they’ll want satisfaction from you. I mean it! You can’t blame drink or drug or anything and then get rid of me because I won’t go.’

Kel waited for him to run out of words as water trickled off her hat and cloak onto the mat by the door. She gave Tobe a moment after he stopped talking, to make sure he was done, before she asked, ‘What is that about?’

‘See?’ he cried. ‘You forgot me already – me, Tobeis Boon, whose bond you bought tonight. I knew you was drunk or takin’ a drug or mad. But here I am an’ here I stay. You need me, to, to carry your wine jug, an’ cut the poppy brick for you to smoke, an’, an’ make sure you eat—’

Kel raised her eyebrows. ‘Quiet,’ she said in the calm, firm tone she had learned from Lord Raoul.

Tobe blinked and closed his mouth.

Kel walked over and blew into his face so he could smell her liquor- and drug-free breath. ‘I’m not drunk,’ she told him. ‘I take no drugs. If I’m mad, it’s in ways that don’t concern you. I went out to get you clothes, Tobe. You can’t go north wearing only a shirt.’

She tossed the sack onto her bed and walked back to the puddle she’d left by the door, then struggled to undo the tie on her hat. Her fingers were stiff with cold even after grooming Hoshi and treating her to a hot mash.

When she removed the hat, a pair of small, scarred hands took it and leaned it against the wall to dry. Once Kel had shed the cloak, Tobe hung it from a peg, then knelt to remove her boots. ‘I have clothes,’ he said, wrestling off one boot while Kel braced herself.

‘I saw,’ she replied, eyeing the heap they made on the floor. ‘I wouldn’t let a cat have kittens on them. I ought to take Alvik before a magistrate anyway. Your bond says you get two full suits of clothes, a coat, and a sturdy pair of shoes every year.’

‘It does?’ he asked, falling on his rump with her boot in his hands.

Kel reached inside her tunic and pulled out his indenture papers. ‘Right there,’ she told him, pointing to the paragraph. When Tobe frowned, she knew Alvik had neglected something else. ‘You can’t read, can you?’ she asked.

‘Alvik said I din’t need no schoolin’, ’acos I was too stupid to learn,’ Tobe informed Kel, searching for a cloth to wipe her boots with. He was practised at this: the innkeeper had taught him to look after guests’ belongings as well as their horses, Kel supposed.

‘Lessons,’ she said, folding the papers once more. ‘After we’re settled in the north.’ She yawned. ‘Wake me at dawn. We’ll try those clothes on you then. And I’m not sure about the, the’ – she yawned again – ‘shoes. I’m not sure these will fit. If we stop on the way, perhaps …’

She looked around, exhaustion addling her brain. Her normal bedtime on the road was much earlier than this. She eyed the door, her dripping hat and cloak, her boots, Tobe.

‘Lady?’ he asked quietly. ‘Sounds like you mean to do all manner of things for me. What was you wishful of me doin’ for you?’

‘Oh, that,’ Kel said, realizing that she hadn’t told him what duties he would have. ‘You’ll look after my horses and belongings, and in four years you’ll be free.’ A will, she realized. I need to make a will so he can be freed if I’m slain. She picked up her water pitcher and drank from the rim. ‘For that, I am duty bound to see that you are fed, clothed, and educated. We’ll settle things like days off. You’ll learn how to clean armour and weapons. That ought to keep you busy enough.’

He nodded. ‘Yes, lady.’

‘Very well. Go to bed. I’m exhausted.’ Unbuttoning her shirt, she realized he hadn’t moved. ‘Bed,’ she said firmly. ‘Cover your head till I say you can come out. I won’t undress while you watch.’

She took her nightshirt out of a saddlebag and finished changing once Tobe was on his pallet with his eyes hidden. In the end, she had to uncover him. He’d gone to sleep with the blanket over his head. Kel banked the fire and blew out the last candle that burned in the room.

The killing device moved in her dreams. Blayce the Nothing Man watched it. He pointed to a child who cowered under his worktable: it was Tobe. The metal thing reached under the table and dragged the boy out.

Kel sat up, gasping, sweat-soaked. It was still dark, still night. The rain had stopped. She was at an inn on the Great Road North, riding to war.

‘Lady,’ Tobe asked, his voice clear, ‘what’s Blayce? What’s Stenmun?’

‘A nightmare and his dog,’ Kel replied, wiping her face on her sleeve. ‘Go back to sleep.’

The rain returned in the morning. The army’s commanders decided it would be foolish to move on. Kel used the day to finish supplying Tobe, making sure that what he had fit properly. Tobe protested the need for more than one set of clothes and for any shoes, saying that she shouldn’t spend money on him.

‘Do you want to make me look bad?’ she demanded at last. ‘People judge a mistress by how well her servants are dressed. Do you want folk to say I’m miserly, or that I don’t know my duty?’

‘Alvik never cared,’ Tobe pointed out as he fed the sparrows cracked corn.

‘He isn’t noble-born,’ Kel retorted. ‘I am. You’ll be dressed properly, and that’s that.’

At least she could afford the sewing and shoe fitting. She had an income, more than she had thought she’d get as the poorly dowered youngest daughter of a large family. For her service in the war she received a purse from the crown every two weeks. Raoul had advised her on investments, which had multiplied both a legal fine once paid to her and her portion of Lalasa’s earnings. Lalasa had insisted on that payment, saying that she would not have been able to grow rich off royal custom if not for her old mistress. It was an argument Kel had yet to win. And it did mean that she could outfit Tobe without emptying her purse, a venture Lalasa would approve.

The rain ended that night. The army set out at dawn, Tobe riding pillion with Kel. Once they were under way, Kel rode back along the line of march until she found the wagon that held the gear of the first-year knights, including Hoshi’s tack, spare saddle blankets, weapons, and all Kel needed to tend her arms and armour. She opened the canvas cover on the wagon and slung the boy inside with one arm.

‘There’s blankets under that saddle, and meat and cheese in that pack,’ she informed him. ‘Bundle up. It’s a cold ride. I’ll get you when we stop for the night.’ She didn’t wait for his answer but tied the cover and returned to her friends.

They ate lunch on horseback as cold rain fell again. Knights and squires huddled in the saddle, miserable despite broad-brimmed hats and oiled cloaks to keep the wet out. Kel had extra warmth from Jump and the sparrows, who had ducked under her cloak the moment the rain had returned.

They were crossing a pocket of a valley when Neal poked Kel and pointed. In the trees to their left, a small figure moved through the undergrowth, following them. Kel twitched Peachblossom off the road and into the woods, cutting Tobe off. He stared up at her, his chin set.

‘I left you in the wagon so you wouldn’t get soaked,’ Kel informed him. He was muddy from toes to knees. ‘Are you mad?’

Tobe shook his head.

‘Then why do this?’ she asked, patiently. ‘You’re no good to either of us if you get sick or fall behind.’

‘Folk took interest in me ’afore, lady,’ replied the boy. ‘A merchant and a priestess. Soon as I was gone from their sight, they forgot I was alive. Sometimes I think I jus’ dreamed you. If I don’t see you, mayhap you’ll vanish.’

‘I’m too solid to be a dream. Besides, I paid two copper nobles for your bond,’ Kel reminded him. ‘Not to mention what we laid out for the sewing and the cobbler.’

‘Folk’ve given me nobles jus’ for holdin’ the stirrup when they mounted up,’ Tobe informed her. ‘Some is so rich, a noble means as much to them as a copper bit to ol’ Alvik.’

Kel sighed. ‘I’m not rich,’ she said, but it was for the sake of argument. Compared with this mule-headed scrap of boyhood, she was rich. It was all she could do not to smile. She recognized the determination in those bright blue eyes. It matched her own.

She evicted the sparrows from the shelter of her cloak and reached a hand down. When he gripped it, Kel swung the boy up behind her. ‘Not a word of complaint,’ she told him. ‘Get under my cloak. It’ll keep the rain off.’

This order he obeyed. Kel waited for the sparrows to tuck themselves under the front of her cloak, then urged Peachblossom back to their place in line.

Neal, seeing her approach, opened his mouth.

‘Not one word,’ Kel warned. ‘Tobe and I have reached an understanding.’

Neal’s lips twitched. ‘Why do I have the feeling you did most of the understanding?’

‘Why do I have the feeling that if you give me a hard time, I’ll tell all of our year-mates your family nickname is Meathead?’ Kel replied in kind.

‘You resort to common insult because you have no stronger arguments to offer,’ retorted Neal. When Kel opened her mouth, Neal raised a hand to silence her. ‘Nevertheless, I concede.’

‘Good,’ Kel said. ‘That’s that.’

‘You got anything to eat?’ enquired a voice from inside her cloak.

April 1–14, 460 near the Scanran border (#ulink_1ba67849-d8d5-57fa-8021-19bddad43109)

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_2bf5c083-072b-5ff3-b8f1-79004ee3bab6)

LONG, COLD ROAD (#ulink_2bf5c083-072b-5ff3-b8f1-79004ee3bab6)

It was well past dark when they reached their next stop, the village of Wolfwood. ‘We’re here for a few days,’ Raoul told the younger knights. ‘Lady Alanna and the troops for the coast leave us here. So will the troops and knights meant for the eastern border. Maybe we’ll even be here long enough to dry out.’

‘What’s dry?’ asked Faleron of King’s Reach wearily.

‘Good question,’ Lady Alanna said, stretching to get the kinks out of her spine. She and Neal chorused, ‘Next question.’ The lady grinned at her former squire. ‘You rode with me too long, Queenscove,’ she pointed out.

‘And I learned things every step of the way, lady knight,’ said Neal with a bow.

Tobe offered to groom Peachblossom and Hoshi. Kel watched as the boy worked.

‘You think he’s a horse-mage?’ Neal murmured. He’d tended his mounts and was ready to go inside. ‘He’s got wild magic with horses?’

‘It seems so,’ Kel admitted, gathering her saddlebags. ‘Look how easy Peachblossom is with him.’ Satisfied that Tobe needed no help, she followed Neal into the wayhouse, Jump and the sparrows trailing behind.

Messengers had warned their hosts of their arrival. There was a tub of hot water in Kel’s room. She scrubbed, changed, then went to find her charge. She found Tobe in Peachblossom’s stall, though both the gelding and Hoshi had been groomed and fed.

‘You’ll sleep in my chamber like last night. There’s a tub there now. Go and wash,’ she ordered. ‘The servants take meals in the east wing of the house. Eat properly, vegetables as well as meat. And drink some milk.’

Tobe grinned at her. ‘He said last night you’re a bear for vegetables – Sir Nealan, that is. Auld Eulama were the same.’ He went to do as he was told. Kel returned to the wayhouse, thinking. They needed to come to an understanding. She couldn’t let him walk, but she didn’t like to share a saddle. Perhaps he could ride Hoshi? Normally Kel would have ridden the mare on a journey like this, but she needed Peachblossom’s strength to help open the road in spots. Hoshi would barely notice Tobe’s weight, and she would keep him out of the mud.

In the common room, Kel picked at her supper, too weary to eat. She was about to go to her room when someone came in. A servant rushed forward to take his wet things; the innkeeper followed to see what the new guest required.

The newcomer was a big fellow, a knight from his tunic badge, with red curly hair and grey eyes. Kel froze. It was Cleon of Kennan, her sweetheart. But something was wrong. She looked at him and saw a brawny knight she knew. Where was the joy of looking at him that she had felt the last time they met? Cleon was as attractive as ever, but he didn’t make her skin tingle as he once had.

Kel bit her lip. As a page she’d thought she was hopelessly in love with Neal. Then, a newly made squire, she’d spent a summer with Lord Raoul and Third Company. Seeing Neal after months of separation, she’d found he looked like just another man, not the bright centre of her heart. Now it had happened again. She and Cleon had kissed, had yearned for time and privacy in which to become lovers. He’d wanted to marry her, though she was not sure that she wanted marriage. Here he was, but she didn’t feel warm and eager at the sight of him. Friendship was there, but passion was gone.

Worse, a part of her wasn’t surprised by the change. They’d been apart for such a long time, with only letters to keep their feelings alive. So much had happened, too much, all of it more vivid and recent than her memories of him. She didn’t want Cleon as a lover now, of that she was sure. There was work to be done. She wanted no lovers until she had settled the Nothing Man’s account.

Kel looked down at her plate. Maybe Cleon wouldn’t see her.

Merric of Hollyrose, at the end of her table, jumped to his feet. ‘Cleon!’ he yelled. Everyone looked at the newcomer and called out greetings. Prince Roald waved him over. Kel fixed a smile on her face.

Cleon too smiled when he saw Kel, but he didn’t seem to notice that Neal offered him a seat beside her. Instead, Cleon took a chair near the prince.

‘Why are you here?’ asked Faleron of King’s Reach. He was one of the knights destined to defend the seacoast. ‘You’re headed the wrong way.’

Cleon glanced at Kel, then looked at Faleron. ‘I got a mage message asking me to come home soonest. You’ve heard there’s flooding in the southwest hills?’

Faleron, whose home was near Cleon’s, sighed. ‘It’s bad,’ he said. ‘Father said a lot of fiefdoms lost their entire stores of grain – oh, no. Yours?’

Cleon nodded, his mouth a grim line. ‘The Lictas River went over its banks and wiped out our storehouses. I’ve got to help Mother raise funds so our people can plant this year.’

Kel met Cleon’s eyes. They had often talked about his home. She knew his estates were short of money.

Abruptly, Cleon stood. ‘May I have a word, Kel? Alone?’

She couldn’t refuse. Her thoughts tumbled as she followed him outside. They stood under the eaves that sheltered the inn’s door, the wind blowing rain onto them. She wondered if he’d noticed she hadn’t moved to kiss him, then realized that he had not tried to kiss her, either. Suddenly she knew what was coming.

‘I’ve just one way to get coin for grain and the livestock we lost, Kel,’ he said. ‘The moneylenders only give Mother polite regrets. I have to marry Ermelian of Aminar or my people will starve this winter.’ He turned away. ‘I’m so sorry. I’d thought, if we had time …’

Relief poured through Kel. She wouldn’t have to hurt him. ‘We knew our chances weren’t good,’ she said over the rattle of sheaves of rain. ‘We did talk about it.’

‘I know,’ he said hoarsely, standing with his back to her. ‘Even knowing I couldn’t break the betrothal honourably, I went ahead and dreamed. That’s the problem with being able to think. It means you wish for things you can’t have.’

Kel wished she could comfort him. Even beyond kisses, he was her friend. She laid a hand on his back. ‘Cleon—’

‘Don’t.’ He twitched away from her touch. ‘I can’t – I’m as good as married now. It wouldn’t be right.’

Relief flooded her again. Cleon was too honourable to kiss her or let her touch him now that he’d agreed to his marriage. She felt shallow, coldhearted, and sorry for him.

‘You said you liked her, when we were on progress,’ she reminded him. ‘You said she’s nice. It could be much worse. People do find happiness, when they’re married to someone good.’

The awful grinding sound that came from his throat was supposed to be a laugh. ‘That’s you, Kel, making the best of it,’ he said. He rubbed his eyes with his arm before he turned to face her. ‘You’re right. I saw her while we were on progress. It was after you left to help that village after the earthquake. She is nice. She’s also pretty and kind. Some of our friends can’t say as much about the wives arranged for them. She just isn’t you. She isn’t my friend, or my comrade.’ He tried to smile.

Kel’s heart hurt. Cleon was still her friend, if not her lover. ‘Come inside,’ she told him. ‘Dry out, and eat. We’ll do our duty, like we’re supposed to. And we can be friends, surely. Nothing changes that.’

‘No,’ he whispered. ‘Nothing will ever change that.’ He raised a hand as if to touch her cheek, then lowered it and went inside.

Kel didn’t cry for her friend and the sudden, hard changes in their lives until she was safe in bed and Tobe was lightly snoring on his pallet. She thought she’d muffled herself until he said, ‘It’s awright, lady. I’d be ascairt, too, goin’ off for savages to shoot at.’

Kel choked, dried her eyes on her nightshirt sleeve, and turned onto her back. ‘It’s not the war, Tobe,’ she replied. She groped for the handkerchief on her bedside table, sat up, and blew her nose. ‘I’ve been shot at. I can bear it. I’m crying because my friend is unhappy and everything is changing.’

‘Is that what you’re ’posed to do?’ he asked. ‘Cry for your friends, though they ain’t dead? Cry when things change?’