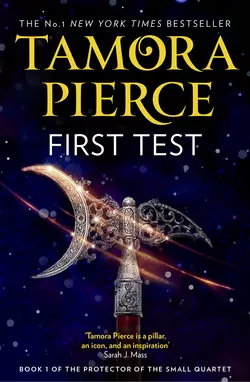

First Test

Tamora Pierce

Kel will not allow this first test to be her last. The adventure begins in the New York Times bestselling series from the fantasy author who is a legend herself: TAMORA PIERCE. A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. HER FIRST TEST WILL NOT BE HER LAST. Keladry of Mindelan is the first girl who dares to take advantage of the new rule that allows women to train for knighthood. But standing in Kel’s way is Lord Wyldon the training master, who is dead set against girls becoming knights. A woman should be lovely. A woman should be charming. A woman should not be deadly. Wyldon demands Kel pass a one-year trial that no male page has ever had to endure. It’s just one more way to separate Kel from her fellow trainees. Kel must prove herself twice as good as her male peers just to be thought equal. But she is not to be underestimated. Kel will fight to succeed, even when odds are stacked against her. Book one of a powerful and classic fantasy quartet about smashing the ceilings others place above you, by the bestselling author of the Song of the Lioness series and Tempests and Slaughter. A powerful classic that is more timely than ever, the Protector of the Small series is about smashing the ceilings others place above you. In a landmark quartet published years before it’s time, Kel must prove herself twice as good as her male peers just to be thought equal. A series that touches on questions of courage, friendship, a humane perspective – told against a backdrop of a magical, action-packed fantasy adventure. ‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones’Washington Post

FIRST TEST

BOOK 1 OF THE PROTECTOR OF THE SMALL QUARTET

Tamora Pierce

Copyright (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Tamora Pierce 1999

Map copyright © Isidre Mones 2017

Jacket design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Tamora Pierce asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008304195

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008304201

Version: 2019-06-25

PRAISE FOR TAMORA PIERCE (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

‘Tamora Pierce didn’t just blaze a trail. Her heroines cut a swathe through the fantasy world with wit, strength, and savvy. Pierce is the real lioness, and we’re all just running to keep pace.’

LEIGH BARDUGO, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce creates epic worlds populated by girls and women of bravery, heart, and strength. Her work inspired a generation of writers and continues to inspire us.’

HOLLY BLACK, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘Tamora Pierce’s books shaped me not only as a young writer but also as a young woman. Her complex, unforgettable heroines and vibrant, intricate worlds blazed a trail for young adult fantasy – and I get to write what I love today because of the path she forged throughout her career. She is a pillar, an icon, and an inspiration.’

SARAH J. MAAS, #1 New York Times bestselling author

‘I take more comfort from and as great pleasure in Tamora Pierce’s Tortall novels as I do from Game of Thrones.’

Washington Post

‘Tamora Pierce and her brilliant heroines didn’t just break down barriers; they smashed them with magical fire.’

KATHERINE ARDEN, author of The Bear and the Nightingale

Dedication (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

To Mallory, who totally made it happen

Contents

Cover (#u8c62c155-a259-5910-88de-1330fcc9dceb)

Title Page (#ue9a571bd-5cdf-569e-b389-8ac23342b549)

Copyright

Praise for Tamora Pierce

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1: Decisions

Chapter 2: Not So Welcome

Chapter 3: The Practice Courts

Chapter 4: Classrooms

Chapter 5: Kel Backs Away

Chapter 6: The Lance

Chapter 7: Kel Takes a Stand

Chapter 8: Winter

Chapter 9: Tests

Chapter 10: The Royal Forest

Chapter 11: Spidren Hunt

Cast of Characters

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Read on for a Preview of Page

Also by Tamora Pierce

About the Publisher

Map (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

CHAPTER 1 (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

DECISIONS (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

Alanna the Lioness, the King’s Champion, could hardly contain her glee. Baron Piers of Mindelan had written to King Jonathan to say that his daughter wished to be a page. Alanna fought to sit still as she watched Wyldon of Cavall, the royal training master, read the baron’s letter. Seated across his desk from them, the king watched the training master as sharply as his Champion did. Lord Wyldon was known for his dislike of female warriors.

It had been ten long years since the proclamation that girls might attempt a page’s training. Alanna had nearly given up hope that such a girl – or the kind of family that would allow her to do so – existed in Tortall, but at last she had come forward. Keladry of Mindelan would not have to hide her sex for eight years as Alanna had done. Keladry would prove to the world that girls could be knights. And she would not be friendless. Alanna had plans to help Keladry through the first few years. It never occurred to the Champion that anyone might object.

Alanna half turned to see Wyldon better. Surely he’d read the letter at least twice! From this side the puffy scars from his battle to save the younger princes and princess were starkly visible; Wyldon’s right arm was in a sling yet from that fight. Alanna rubbed fingers that itched with the urge to apply healing magic. Wyldon had the idea that suffering pain made a warrior stronger. He would not thank her if she tried to heal him now.

Goddess bless, she thought tiredly. How will I ever get on with him if I’m to help this girl Keladry?

Wyldon was not flexible: he’d proved that to the entire court over and over. If he were any stiffer, Alanna thought wryly, I’d paint a design on him and use him for a shield. He’s got no sense of humour and he rejects change just because it’s change.

Still, she had to admit that his teaching worked. During the Immortals War of the spring and early summer, when legendary creatures had joined with the realm’s human enemies to take the kingdom, the squires and pages had been forced into battle. They had done well, thanks to their training by Wyldon and the teachers he had picked.

At last Lord Wyldon returned the letter to King Jonathan, who placed it on his desk. ‘The baron and the baroness of Mindelan are faithful servants of the crown,’ the king remarked. ‘We would not have this treaty with the Yamani Islands were it not for them. You will have read that their daughter received some warrior training at the Yamani court, so it would appear that Keladry has an aptitude.’

Lord Wyldon resettled his arm in its sling. ‘I did not agree to this, Your Majesty.’

Alanna was about to say that he didn’t have to agree when she saw the king give the tiniest shake of the head. Clenching her jaws, she kept her remark to herself as King Jonathan raised his eyebrows.

‘Your predecessor agreed,’ he reminded Wyldon. ‘And you, my lord, implied agreement when you accepted the post of training master.’

‘That is a lawyer’s reply, sire,’ Wyldon replied stiffly, a slight flush rising in his clean-shaven cheeks.

‘Then here is a king’s: we desire this girl to train as a page.’

And that is that, Alanna thought, satisfied. She might be the kind of knight who would argue with her king, at least in private, but Wyldon would never let himself do so.

The training master absently rubbed the arm in its linen sling. At last he bowed in his chair. ‘May we compromise, sire?’

Alanna stiffened. She hated that word! ‘Com—’ she began to say.

The king silenced her with a look. ‘What do you want, my lord?’

‘In all honesty,’ said the training master, thinking aloud, ‘I had thought that our noble parents loved their daughters too much to place them in so hard a life.’

‘Not everyone is afraid to do anything new,’ Alanna replied sharply.

‘Lioness,’ said the king, his voice dangerously quiet. Alanna clenched her fists. What was going on? Was Jonathan inclined to give way to the man who’d saved his children?

Wyldon’s eyes met hers squarely. ‘Your bias is known, Lady Alanna.’ To the king he said, ‘Surely the girl’s parents cannot be aware of the difficulties she will encounter.’

‘Baron Piers and Lady Ilane are not fools,’ replied King Jonathan. ‘They have given us three good, worthy knights already.’

Lord Wyldon gave a reluctant nod. Anders, Inness, and Conal of Mindelan were credits to their training. The realm would feel the loss of Anders – whose war wounds could never heal entirely – from the active duty rolls. It would take years to replace those who were killed or maimed in the Immortals War.

‘Sire, please, think this through,’ Wyldon said. ‘We need the realm’s sons. Girls are fragile, more emotional, easier to frighten. They are not as strong in their arms and shoulders as men. They tire easily. This girl would get any warriors who serve with her killed on some dark night.’

Alanna started to get up. This time King Jonathan walked out from behind his desk. Standing beside his Champion, he gripped one of her shoulders, keeping her in her chair.

‘But I will be fair,’ Wyldon continued. His brown eyes were hard. ‘Let her be on probation for a year. By the end of the summer field camp, if she has not convinced me of her ability to keep up, she must go home.’

‘Who judges her fitness?’ enquired the king.

Wyldon’s lips tightened. ‘Who but the training master, sire? I have the most experience in evaluating the young for their roles as future knights.’

Alanna turned to stare at the king. ‘No boy has ever undergone a probationary period!’ she cried.

Wyldon raised his good shoulder in a shrug. ‘Perhaps they should. For now, I will not tender my resignation over this, provided I judge whether this girl stays or goes in one year’s time.’

The king weighed the request. Alanna fidgeted. She knew Lord Wyldon meant his threat, and the crown needed him. Too many great nobles, dismayed by the changes in Tortall since Jonathan’s coronation, felt that Wyldon was their voice at court. If he resigned, the king and queen would find it hard to get support for their future changes.

At last King Jonathan said, ‘Though we do not always agree, my lord, you know I respect you because you are fair and honourable. I would hate to see that fairness, that honour, tainted in any way. Keladry of Mindelan shall have a year’s probation.’

Lord Wyldon nodded, then inspected the nails on his good hand. ‘There is one other matter,’ he remarked slowly. He looked at Alanna. ‘Do you plan to involve yourself in the girl’s training? It will not do.’

Alanna bristled. ‘What is that supposed to mean?’

‘You wish to help the girl, understandably.’ Wyldon spoke as though the mild words made his teeth hurt. ‘But you rarely deal with the lads, my lady. If you help the girl, it will be said that you eased her path in some special way. There are rumours that your successes are due to your magical Gift.’

‘By the Goddess,’ snapped Alanna, crimson with fury. If the king had not forbidden her to challenge men on personal grounds years before, she would have taken Wyldon out to the duelling court and made him regret his words.

‘Alanna, for heaven’s sake, you know the gossip,’ King Jonathan said. ‘Stop acting as if you’d never heard it before.’ He looked at Wyldon. ‘And you suggest …’

‘Lady Alanna must keep from all contact with the girl,’ Wyldon replied firmly. ‘Even a moment’s conversation will give rise to suspicion.’

‘All contact?’ cried Alanna. ‘But she’ll be the only girl among over twenty boys! She’ll have questions – I could help—’ She realized what she had said and fell silent.

King Jonathan gently patted her shoulder. ‘Is there no other way?’ he asked.

Wyldon shook his head. ‘I fear not, sire. The Mindelan girl will be the cause of trouble as it is, without the Lioness hovering over her.’

The king thought it over. At last he sighed. ‘Lord Wyldon has the right of it. You must stay away from Keladry of Mindelan, Alanna.’

‘But Jonathan – sire—’ she pleaded, not believing he would do this.

‘That is an order, lady knight. If you cannot accept that, say as much now, and I will find you work elsewhere.’

She stared at him for a long moment, lips tight. At last she got to her feet. ‘Don’t tax yourself. I’ll find knight’s work myself,’ she told him. ‘As far from Corus as possible.’ She stalked out of the room, slamming the door in her wake.

The men stared at the door. Each of them was trying to remember if Alanna the Lioness had ever spoken to Jonathan in that tone before.

Baron Piers and Lady Ilane of Mindelan watched Keladry read the reply from the training master. A Tortallan who did not know them well might have thought the man and woman felt nothing, and that their ten-year-old daughter was only concerned, not upset. That was far from true. The family had spent the last six years living in the Yamani Islands, where displays of deep emotion were regarded as shameful. To get the Yamanis to respect them, they had all learned to hide their feelings. Home in Mindelan again, they still acted as Yamanis, hiding uneasiness and even distress behind still faces.

Kel struggled to reread the letter, afraid to say a word. If she did, her shaking voice would give her away. Instead she waited as she tried to control the anger and sense of betrayal that filled her.

‘It is not the reply we expected,’ Baron Piers said at last. He was a short, stocky man. Keladry had his build, delicate nose, and dreamy, long-lashed hazel eyes. Her brown hair was several shades lighter than his. When Kel did not reply he continued, ‘His declaration of ten years ago was that girls could become pages. Nothing was said of probation then.’

‘Keladry?’ asked her mother. ‘You can say what you feel. We are no longer among the Yamanis.’ She was a thin, elegant woman, taller than her husband by nearly a head, with hair that had gone white very early in life and a deep, musical voice. All Keladry had from her was height. At the age of ten the girl was already five feet tall and still growing.

It took Kel a moment to register what her mother had said. She tried a smile. ‘But, Mama, I don’t want to get into bad habits, in case I go back with you.’ She looked at Lord Wyldon’s letter again. She had expected to be a page when her parents returned to the Yamani Islands in eighteen months. From the tone of this letter, perhaps she ought not to count on that.

‘It isn’t right,’ she said quietly, even fiercely. ‘No boys have probation. I’m supposed to be treated the same.’

‘Don’t give your answer yet,’ Baron Piers said quickly. ‘Take the letter with you. Think about what it says. You’re not hasty, Kel – this is a bad time to start.’

‘Reflect as if you have all of time, even when time is short,’ added her mother in Yamani. ‘Be as stone.’

Kel bowed Yamani-style, palms flat on her thighs. Then she went to find someplace quiet to think.

First she went to her room beside the nursery. That wasn’t a good choice. Two of her brothers’ young families lived at Mindelan. With the children and their nursemaids next door, there was enough noise to drown out trumpets. No one had seen her creep into the room, but her oldest nephew saw her leaving it. Nothing would do for him but that she give him a piggyback ride around the large room. After that, all of the older children wanted rides of their own. Once that was done, the nursemaids helped Kel to escape.

She tried to hole up by the fountain in the castle garden, but her sisters-in-law were there, sewing and gossiping with their maids. The kitchen garden was her next choice, but two servants were there gathering vegetables. She stared longingly at her favourite childhood spot, the highest tower in the castle, and felt a surge of anger. Before they had gone to the islands her brother Conal had teasingly held her over the edge of the tower balcony. Until that time she had visited the top of that tower at least once a day. Now the thought of it made her shudder.

There were hundreds of places she might use around the castle, but they were all indoors. She needed to be outside. She was trying to think of a place when she remembered the broad, shallow Domin River, which ran through the woods. No one would be there. She could sit by the water and think in peace.

‘Miss?’ called a voice as she strode through the inner gate in the castle wall. ‘Where might you be going?’

Kel turned to face the man-at-arms who had called to her. ‘I don’t know.’

The man held out a small horn. ‘If you’re not going to the village, you need one of these.’ He spoke carefully. The baron and his family had been home only for three months, and the people were still not sure what to make of these strange, Yamani-like nobles. ‘They told you the rule, surely. Any time you go outside the castle or village, you take a horn. You never know when one of them monsters, centaurs or giants or whatever, will show its face.’

Kel frowned. The legendary creatures that had returned to their world five years before had an unnerving way of showing up when they were least expected. For every one that was harmless or willing to get on with humans, there were fistfuls that weren’t. Bands of men-at-arms now roamed throughout the fiefdom, searching for hostile visitors and listening for the horn call, which meant someone was in trouble.

I’m not going very far, she wanted to argue, but the Yamanis had taught her to obey a soldier’s commands. She accepted the horn with a quiet thank-you and slung it over one shoulder. Checking that Lord Wyldon’s letter was tucked securely in the front of her shirt, she left the road that led from the castle gate and headed through their orchards. Once past the cultivated trees she entered the woods, following a trail down to the water.

By the time she could see a glint of silver through the trees she had worked up a mild sweat. The day was warm and the walk was longer than she had thought it would be. When a rock worked its way into her shoe, she sat on a log to get it out.

‘It’s not right,’ she muttered to herself, undoing the laces that held the leather around her ankle. ‘You’re a page for four years. That’s how it’s been done for centuries. Now they’re going to change it?’ When she up-ended the shoe and shook it, nothing fell out. She stuffed a hand inside, feeling around for the stone. ‘And just because I’m a girl? They ought to treat me the same. All I want is the same chance as the boys. No more, no less. That’s right, isn’t it?’ She winced as a sharp edge nipped one of her fingers. Working more carefully, she wiggled the bit of rock out of a fold in the leather. ‘Probation is not fair, and knighthood training has to be fair.’

The stone was out; her mind was made up. If they couldn’t treat her the same as they would the boys, then she wasn’t going to settle for a half portion. She would have to become a warrior some other way.

Kel sighed and put her shoe back on. The problem was that now she would have to wait. The Queen’s Riders took volunteers when they were fifteen or older. The queen’s ladies, those who were expected to ride, handle a bow, and deal with trouble at Queen Thayet’s side, went to her in their fifteenth year as well. And who was to say Kel wouldn’t be living in the Yamani Islands by then?

One thing she knew: convent school, the normal destination for noble girls her age, was not a choice. Kel had no interest whatever in ladylike arts, and even less interest in the skills needed to attract a husband or manage a castle. Even if she did, who would have her? Once she’d overheard her sisters-in-law comment that no man would be interested in a girl who was built along the lines of a cow.

She’d made the mistake of repeating that comment to her mother, when Kel’s plan to be a page had first come up. Her mother had gone white with fury and had put her daughters-in-law to mending several years’ worth of old linens. It had taken a great deal of persuasion for Kel to convince her mother that her quest for knighthood did not mean she wanted to settle for second best, knowing she would never marry. Getting Ilane of Mindelan to agree to her being a page had been a negotiation every bit as complicated as what her father had done to get the Yamanis to sign the treaty.

And see the good that did me, Kel thought with disgust. Lord Wyldon offers me second best anyway, and I won’t take it. I could have saved my breath talking Mama around.

She was ready to get to her feet when the sound of bodies crashing through the brush made her look up. Gruff voices reached her ear.

‘Hurry up!’ a boy growled from near the river. ‘Do you want us t’get caught?’

‘The Cow’s at home,’ replied a second boy’s voice. ‘She stays there all morning.’

Kel stood, listening. If they were on the lookout for her, then they were up to something bad. In just three months she had taught the local boys she was someone to respect. Kel grabbed a sturdy fallen branch and ran towards the voices. Racing into open ground between the trees and river, she saw three village boys. They were about to throw a wriggling cloth sack into the Domin.

Her mouth settled into a tight, angry line; her hazel eyes glittered. ‘Put that down!’ she cried.

The boys whirled, startled, dropping their burden on a half-submerged tree limb. One of them punched the smallest in the shoulder. ‘Home all morning, eh?’

Kel shouted, ‘I know all of you! And you know the law in Mindelan – no killing of animals without the baron’s leave!’

The biggest, taller than she by half a head, advanced. The other two were right behind him. ‘Who’s to make us stop, Cow?’

The Yamanis had taught her well. She waded into the boys, using her club as an equalizer. She whacked them in the belly so they couldn’t breathe, and on the collarbones and biceps so they couldn’t raise their arms. One youth punched her face; he caught her on the outside of one eye. She changed her grip on her branch and swept his feet from under him, then stood on one of his arms.

Another lad grabbed a branch and swung at her; she blocked it with hers, then rammed the length of wood into his stomach. He doubled over, gasping. Kel shoved him into the third boy. Down they went in a tumble. When they untangled themselves, they ran. Their comrade also chose to make his escape.

Kel looked around for the sack. The current had tugged the tree limb on which it rested out into the deeper, faster water at the centre of the river. She didn’t hesitate, but waded into the water. Kel was a good swimmer and the river here was fairly shallow. She doubted that whatever small creatures were struggling in the sack could swim.

Movement on the far bank made her look up. What she saw made her halt, cold water rushing around her thighs. Something black and strange-looking walked out from under the shelter of the trees. It looked like a giant furred spider nearly five feet tall, with one difference. The thing had a human head. It stared at Kel, then grinned broadly to reveal sharp teeth.

Her flesh crawled; hairs stood up on her arms and the back of her neck. Spidren, she thought, recognizing it from descriptions. Spidrens in our woods.

Like most of the legendary creatures that now prowled the Human Realms, they were virtually immortal, immune to disease and old age. They died only when something or someone took pains to kill them. They fed on animals and human blood. No one could get spidrens to make peace with human beings.

The thing reared up on its back legs, revealing a light-coloured shaft at the base of its belly. From it the spidren squirted a high-flying grey stream that soared into the air over the river. Kel threw herself to one side, away from the grey stream and the sack she was trying to catch. The stuff was like rope. She realized it was a web when it fell in a long line across the surface of the water. It had missed her by only a foot. The spidren bent and snipped the rope off from its belly spinneret with a clawed leg. Swiftly it began to wind the length of web around another clawed foot. As it dragged through the water, the sticky thing caught on the cloth sack. The spidren reeled in its catch as a fisherman might pull in a line.

Kel brought the horn up to her mouth. She blew five hard blasts and might have continued to blow until help came, as the spidren gathered up the sack. It discarded its web with one clawed foot, held the sack with a second, and reached into it with a third. The beast grinned, its eyes never leaving Kel, as it pulled out a wet and squirming kitten.

The horn fell from the girl’s lips as the spidren looked the kitten over. It smacked its lips, then bit the small creature in half and began to chew.

Kel screamed and groped on the river bottom with both hands for ammunition. Coming up with a stone in each fist, she hurled the first. It soared past the spidren, missing by inches. Her next stone caught it square in the head. It shrieked and began to climb the bluff that over-looked the river to its left, still holding the sack.

In the distance Kel heard the sound of horns. Help was on its way – for her, but not for those kittens. She scrabbled for more stones and plunged across the river, battling the water to get to the same shore as the monster. It continued to climb the rocky face of the bluff until it reached the summit just as Kel scrambled onto the land.

Once she was on solid ground, she began to climb the bluff, her soaked feet digging for purchase in soft dirt and rock. Above, the spidren leaned over the edge of the bluff to leer at her. It reached into the sack, dragged out a second kitten, and began to eat it.

Kel still had a rock in her right hand. She hurled it as hard as she had ever thrown a ball to knock down a target. It smashed the spidren’s nose. The thing shrieked and hissed, dropping the rest of its meal.

Kel’s foot slipped. She looked down to find a better place to set it and froze. She was only seven feet above the water, but the distance seemed more like seventy to her. A roar filled her ears and her head span. Cold sweat trickled through her clothes. She clung to the face of the bluff with both arms and legs, sick with fear.

Leaving its sack on the ground, the spidren threw a loop of web around a nearby tree stump. When it was set, the creature began to lower itself over the side of the bluff. Its hate-filled eyes were locked on the girl, whose terror had frozen her in place.

Kel was deaf and blind to the spidren’s approach. Later she could not recall hearing the monster’s scream as arrows thudded into its flesh, just as she could not remember the arrival of her brother Anders and his men-at-arms.

With the spidren’s death, its web rope snapped. The thing hurtled past Kel to splash into the river.

A man-at-arms climbed up to get her, gently prising her clutching fingers from their holds. Only when Kel was safely on the shore, seated on a flat rock, was she able to tell them why she had tried to kill a spidren with only stones for weapons. Someone climbed the bluff to retrieve the sack of kittens while Kel stared, shivering, at the spidren’s body.

Her brother Anders dismounted stiffly and limped over to her. Reaching into his belt pouch, he pulled out a handful of fresh mint leaves, crushed them in one gloved hand, and held them under Kel’s nose. She breathed their fresh scent in gratefully.

‘You’re supposed to have real weapons when you go after something that’s twice as big as you are,’ he told her mildly. ‘Didn’t the Yamanis teach you that?’ During the years most of their family had been in the Islands, Anders, Inness, and Conal, the three oldest sons of the manor, had served the crown as pages, squires, then knights. All they knew of Kel’s experiences there came in their family’s letters.

‘I had to do something,’ Kel explained.

‘Calling for help and staying put would have been wiser,’ he pointed out. ‘Leave the fighting to real warriors. Here we are.’ A man-at-arms put the recovered sack into his hands. Anders in turn put the bag in Kel’s lap.

Nervously she pulled the bag open. Five wet kittens, their eyes barely opened, turned their faces up to her and protested their morning’s adventure. ‘I’ll take you to our housekeeper,’ Kel promised them. ‘She knows what to do with kittens.’

Once the animals were seen to and she had changed into a clean gown and slippers, Kel went to her father’s study. With her came a small group of animals: two elderly dogs, three cats, two puppies, a kitten, and a three-legged pine marten. Kel gently moved them out of the way and closed the door before they could sneak into the room. Anders was there, leaning on a walking stick as he talked to their parents. All three adults fell silent and looked at Kel.

‘I’ll do it,’ she said quietly. ‘I want the training, and the right weapons. Anders was right. It was stupid to go after a spidren with stones.’

‘And if they send you home at the end of a year?’ asked Ilane of Mindelan.

Kel took a deep breath. ‘Then I’ll still know more than I do now,’ she said firmly.

Piers looked at his wife, who nodded. ‘Then we’d best pack,’ said Ilane, getting to her feet. ‘You leave the day after tomorrow.’ Passing Kel on her way to the door, her mother lightly touched the eye the village boy had hit. It was red, blue, and puffy – not the worst black eye Kel had ever had. ‘Let’s also get a piece of raw meat to put on this,’ suggested the woman.

The next evening, Kel made her way to the stables to visit her pony, Chipper, to explain to him that the palace would supply her with a knight’s mount. The pony lipped her shirt in an understanding way. He at least would be in good hands: Anders’s oldest son was ready to start riding, and he loved the pony.

‘I thought I might find you here,’ a voice said as Kel fed Chip an apple. She squeaked in surprise. For a man with a limp and a cane, Anders moved very quietly. ‘You know we’ll take care of him.’

Kel nodded and picked up a brush to groom the pony’s round sides. ‘I know. I’ll miss him all the same.’

Anders leaned against a post. ‘Kel …’

She looked at him. Since the incident on the river the day before, she’d caught Anders watching her. She barely remembered him before their departure to the Islands, six years ago – he had already been a knight, handsome and distant in his armour, always riding somewhere. In the months since their return to Mindelan, she had come to like him. ‘Something the matter?’ she asked.

Anders sighed. ‘Do you realize it’s going to be hard? Maybe impossible? They’ll make it tough. There’s hazing, for one thing. I don’t know when the custom started, but it’s called “earning your way”. It’s just for the first-year pages. The senior ones make you run stupid little errands, like fetching gloves and picking up things that get knocked over. You have to do it. Otherwise it’s the same as saying you don’t have to do what the older pages did, as if you think you’re better than they are. And older pages play tricks on the young ones, and some of them will pick fights. Stand up for yourself, or they’ll make your life a misery.’

‘In the rules they sent, fighting isn’t allowed.’

‘Of course it’s forbidden. If you’re caught, they punish you. That’s expected. What you must never do is tattle on another page, or say who you fought with. That’s expected, too. Tell them you fell down – that’s what I always said. Otherwise no one will trust you. A boy told when I was a page. He finally left because no one would speak to him.’

‘But they’ll punish me for fighting?’

‘With chores, extra lessons, things like that. You take every punishment, whatever it’s for, and keep quiet.’

‘Like the Yamanis,’ she said, brushing loose hairs from Chipper’s coat. ‘You don’t talk – you obey.’

Anders nodded. ‘Just do what you’re told. Don’t complain. If you can’t do it, say that you failed, not that you can’t. No one can finish every task that’s given. What your teachers don’t want is excuses, or blaming someone else, or saying it’s unfair. They know it’s unfair. Do what you can, and take your punishment in silence.’

Kel nodded. ‘I can do that, I think.’

Anders chuckled. ‘That’s the strange thing – I believe you can. But, Kel—’

Kel went to Chip’s far side, looking at Anders over the pony’s back. ‘What?’

The young man absently rubbed his stiff leg. ‘Kel, all these things you learned in the Islands …’

‘Yes?’ she prodded when he fell silent again.

‘You might want to keep them to yourself. Otherwise, the pages might think you believe you’re better than they are. You don’t want to be different, all right? At least, not any more different than you already are.’

‘Won’t they want to learn new things?’ she wanted to know. ‘I would.’

‘Not everyone’s like you, Kel. Do what they teach you, no more. You’ll save yourself heartache that way.’

Kel smiled. ‘I’ll try,’ she told him.

Anders straightened with a wince. ‘Don’t be out here too long,’ he reminded her. ‘You’re up before dawn.’

Unlike normal dreams, in which time and places and people did strange things, this dream was completely true to Kel’s memory. It began as she knelt before an altar and stared at the swords placed on it. The weapons were sheathed in pure gold rubbed as smooth and bright as glass. She was five years old again.

‘They are the swords given to the children of the fire goddess, Yama,’ a lady-in-waiting beside Kel said, awe in her soft voice. ‘The short sword is the sword of law. Without it, we are only animals. The long sword is the sword of duty. It is the terrible sword, the killing sword.’ Her words struck a chord in Kel that left the little girl breathless. She liked the idea that duty was a killing sword. ‘Without duty,’ the lady continued, ‘duty to our lords, to our families, and to the law, we are less than animals.’

Kel smelled burning wood. She looked around, curious. The large oil lamps that hung from the temple ceiling by thick cords smelled of perfume, not wood. Kel sniffed the air. She knew that fires were terrible on the Yamani Islands, where indoor walls were often paper screens and straw mats covered floors of polished wood.

The lady-in-waiting got to her feet.

The temple doors crashed open. There was Kel’s mother, Ilane, her outer kimono flapping open, her thick pale hair falling out of its pins. In her hands she carried a staff capped with a broad, curved blade. Her blue-green eyes were huge in her bone-white face.

‘Please excuse me,’ she told the lady-in-waiting, as calm and polite as any Yamani in danger, ‘but we must get out of here and find help. Pirates have attacked the cove and are within the palace.’

There was a thunder of shod feet on polished wood floors. Swords and axes crashed through the paper screens that formed the wall behind the altar. Scanrans – men already covered in blood and grime – burst into the room, fighting their way clear of the screens and their wooden frames.

An arm wrapped tight around Kel’s ribs, yanking her from her feet. The lady-in-waiting had scooped her up in one arm and the swords in the other. Faster than the raiders she ran to Ilane of Mindelan.

The lady tumbled to the ground. Kel slid out the door on her belly. Turning, too startled to cry, she saw the lady at her mother’s feet. There was an arrow in the Yamani woman’s back.

Ilane bent over the dead woman and took the swords. Hoisting them in one hand, she swung her weapon to her right and to her left. It sheared through the heavy cords that suspended five large oil lamps. They fell and shattered, spilling a flood of burning oil. It raced across the temple in the path of the raiders who were running towards them. When their feet began to burn, they halted, trying to put the fire out.

‘Come on!’ Kel’s mother urged. ‘Hike up those skirts and run!’

Kel yanked her kimono up and fled with Ilane. They skidded and slipped over the polished floors in their Yamani sock-shoes, then turned down one corridor and another. Far down one passage they saw a new group of Scanrans. Kel and her mother ran around a corner. They tried another turning – it led to a dead end. They were trapped. The walls that now blocked them in on three sides were sturdy wood, too. They could have cut their way through paper ones.

Ilane turned. Scanrans armed with swords or axes blocked the way out.

Ilane thrust the gold swords into Kel’s arms and pushed her into a corner, then stood before her. ‘Get down and be quiet!’ she said, gripping her weapon in both hands. ‘I think I can hold them off with this.’

Kel put the swords behind her and huddled. The men came at her mother, laughing and joking in Scanran. She peeked around the edge of her mother’s kimono. At that moment Ilane swung the bladed staff – glaive, Kel remembered as it swung, they called it a glaive – in a wide side cut, slicing one pirate across the chest. Whipping it back to her left, she caught another of them in the throat. Blood struck Kel’s face; even dreaming, she could smell it. Breathless, the sheathed swords poking into her back, she watched her mother lunge and retreat, using her skill and her longer weapon to hold the enemy off. Ilane killed a third and a fourth attacker before a squad of guardsmen raced around the corner to finish the rest.

When the pirates were dead, Kel’s mother turned and reached a hand down to her. ‘Let’s go to find your father,’ she said quietly.

Kel grasped the hand, and let her mother pull her to her feet. Then Kel gathered up the golden swords that had been trusted to them.

When they faced their rescuers, the guards knelt as one. They bowed low to the woman and the girl, touching their heads to the bloody floor.

Kel woke, breathing fast, her eyes shining. Her heart raced; she trembled all over. The dream was not scary; it was exciting. She loved it. She loved that it had all been real.

I want to be like that, she told herself as she always did. I want to protect people. And I will. I will. I’ll be a hero one day, just like Mama. Just like the Lioness.

Nobody will kill two kittens in front of me then.

CHAPTER 2 (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

NOT SO WELCOME (#u3fb4c574-a243-5a3a-ac75-02b8b1e1c065)

Wyldon of Cavall nodded to Baron Piers, but his eyes were on Kel. He looked her over from top to toe, taking in every wrinkle and spot in her tunic and breeches and the fading bruise around her eye.

Kel met his gaze squarely. The training master was handsome, for all that he was completely bald on top. He wore what was left of his light brown hair cropped very short. A scar – so red and puffy, it had to be recent – ran from the corner of his eye across his right temple to dig a track through his hair to his ear. His right arm rested in a sling. His eyes were brown, his mouth wide; his chin was square with a hint of a cleft in it. His big hands were marked with scars. He dressed simply, in a pale blue tunic, a white shirt, and dark blue hose. She couldn’t see his feet behind the big desk, but she suspected that his shoes were as sensible as the rest of him.

Even the Yamanis would say he’s got too much stone in him, she thought, looking at the scuffed toes of her boots. He needs water to balance his nature. Peering through her lashes at the training master, she added, Lots of water. A century or two of it, maybe.

Wyldon drummed his fingers on his desktop. At last he smiled tightly. ‘Be seated, please, both of you.’

Kel and her father obeyed.

Wyldon took his own seat. ‘Well. Keladry, is it?’ She nodded. ‘You understand that you are here on sufferance. You have a year in which to prove that you can keep up with the boys. If you do not satisfy me on that count, you will go home.’

He’s never said that to any boy, Kel thought, glad that her face would not show her resentment. He shouldn’t be saying it to me. She kept her voice polite as she answered, ‘Yes, my lord.’

‘You will get no special privileges or treatment, despite your sex.’ Wyldon’s eyes were stony. ‘I will not tolerate flirtations. If there is a boy in your room, the door must be open. The same is true if you are in a boy’s room. Should you disobey, you will be sent home immediately.’

Kel met his eyes. ‘Yes, sir.’ She was talkative enough with her family, but not with outsiders. The chill that rose from Wyldon made her even quieter.

Piers shifted in his seat. ‘My daughter is only ten, Lord Wyldon. She’s a bit young for that kind of thing.’

‘My experience with females is that they begin early,’ the training master said flatly. He ran a blunt-tipped finger down a piece of paper.

‘It says here that you claim no magical Gift,’ stated Lord Wyldon. ‘Is that so?’

Kel nodded.

Lord Wyldon put down the paper and leaned forward, clasping his hands on his neatly ordered desk. ‘In your father’s day, the royal household always dined in the banquet hall. Now our royal family dines privately for the most part. On great holidays and on special occasions, feasts are held with the sovereigns, nobles, and guests in attendance. The pages are required to serve at such banquets. Also, you are required to run errands for any lord or lady who asks.

‘Has she a servant with her?’ he asked Kel’s father.

‘No,’ Piers replied.

‘Very well. Palace staff will tend her rooms. Have you any questions?’ Wyldon asked Kel.

Yes, she wanted to say. Why won’t you treat me like you treat the boys? Why can’t you be fair?

She kept it to herself. Growing up in a diplomat’s house, she had learned how to read people. A good look at Wyldon’s square, stubborn face with its hard jaw had told Kel that words would mean nothing to this man. She would have to prove to him that she was as good as any boy. And she would.

‘No questions, my lord,’ she told him quietly.

‘There is a chamber across the hall for your farewells,’ Wyldon told Piers. ‘Salma will come for Keladry and guide her to her assigned room. No doubt her baggage already is there.’ He looked at Kel. ‘Unpack your things neatly. When the supper bell rings, stand in the hall with the new boys. Sponsors – older pages who show the new ones how things are done – must be chosen before we go down to the mess.’

After Kel said goodbye to her father, she found Salma waiting for her in the hall. The woman was short and thin, with frizzy brown hair and large, dark eyes. She wore the palace uniform for women servants, a dark skirt and a white blouse. A large ring laden with keys hung from her belt. As she took Kel to her new room, Salma asked if Kel had brought a personal servant.

When the girl replied that she hadn’t, Salma told her, ‘In that case, I’ll assign a servant to you. We bring you hot water for washup and get your fire going in the morning. We also do your laundry and mending, make beds, sweep, and so on. And if you play any tricks on the servants, you’ll do your laundry and bed-making for the rest of the year. It’s not our job to look after weapons, equipment, or armour, mind. That’s what you’re here to learn.’

She briskly led the way through one long hall as she talked. Now they passed a row of doors. Each bore a piece of slate with a name written in chalk. ‘That’s my room,’ Salma explained, pointing. ‘The ground floor here is the pages’ wing. Squires are the next floor up. If you need supplies, or special cleaning and sewing, or if you are ill, come to me.’

Kel looked at her curiously. ‘My brothers didn’t mention you.’

‘Timon Greendale, our headman, reorganized service here six years ago,’ Salma replied. ‘I was brought in five years back – just in time to meet your brother Conal. Don’t worry. I won’t hold it against you.’

Kel smiled wryly. Conal had that effect on people.

Salma halted in front of the last door in the hall. There was no name written on the slate. ‘This is your room,’ she remarked. ‘I told the men to put your things here.’ She brushed the slate with her fingertips. ‘Your name has been washed off. I have to get my chalk. You may as well unpack.’

‘Thank you,’ Kel said.

‘No need to thank me,’ was Salma’s calm reply. ‘I do what they pay me to.’ She hesitated, then added, ‘If you need anything, even if it’s just a sympathetic ear, tell me.’ She rested a warm hand on Kel’s shoulder for a moment, then walked away.

Entering her room, Kel shut the door. When she turned, a gasp escaped before she locked her lips.

She surveyed the damage. The narrow bed was overturned. Mattress, sheets, and blankets were strewn everywhere. The drapes lay on the floor and the shutters hung open. Two chairs, a bookcase, a pair of night tables, and an oak clothespress were also upended. The desk must have been too heavy for such treatment, but its drawers had been dumped onto the floor. Her packs were opened and their contents tumbled out. Someone had used her practice glaive to slash and pull down the wall hangings. On the plaster wall she saw written: No Girls! Go Home! You Won’t Last!

Kel took deep breaths until the storm of hurt and anger that filled her was under control. Once that was done, she began to clean up. The first thing she checked was the small wooden box containing her collection of Yamani porcelain lucky cats. She had a dozen or so, each a different size and colour, each sitting with one paw upraised. The box itself was dented on one corner, but its contents were safe. Her mother had packed each cat in a handkerchief to keep it from breaking.

That’s something, at least, Kel thought. But what about next time? Maybe she ought to ship them home.

As she gathered up her clothes, she heard a knock. She opened her door a crack. It was Salma. The minute the woman saw her face, she knew something was wrong. ‘Open,’ she commanded.

Kel let her in and shut the door.

‘You were warned this kind of thing might happen?’ Salma asked finally.

Kel nodded. ‘I’m cleaning up.’

‘I told you, it’s your job to perform a warrior’s tasks. We do this kind of work,’ Salma replied. ‘Leave this to me. By the time you come back from supper it will be as good as new. Are you going to change clothes?’

Kel nodded.

‘Why don’t you do that? It’s nearly time for you to wait outside. I’ll need your key once you’re done in here.’

Kel scooped up the things she needed and walked into the next room. Small and bare, it served as a dressing room and bathroom. The privy was behind a door set in the wall. There was little in here to destroy, but the mirror and the privy seat were soaped.

Kel shut the door. Before she had seen her room, she had planned to wear tunic and breeches as she had for the journey. She’d thought that if she was to train as a boy, she ought to dress like one. They were also more comfortable. Now she felt differently. She was a girl; she had nothing to be ashamed of, and they had better learn that first thing. The best way to remind them was to dress at least part of the time as a girl.

Stripping off her travel-stained clothes, she pulled on a yellow linen shift and topped it with her second-best dress, a fawn-brown cotton that looked well against the yellow. She removed her boots and put on white stockings and brown leather slippers.

Cleaning the mirror, she looked at herself. The gown was creased from being packed, but that could not be helped. She still had a black eye. There was nothing she could do with her mouse-brown hair: she’d had it cropped to her earlobes before she’d left home. Next trip to market, maybe I’ll get some ribbons, she thought grimly, running a comb through her hair. Some nice, bright ribbons.

She grinned at her own folly. Hadn’t she learned by now that the first thing a boy grabbed in a fight was hair? She’d lose chunks of it or get half choked if she wore ornaments and ribbons.

Overhead a bell clanged three times. She winced: the sound was loud.

‘Time,’ Salma called.

If she thought anything of the change in Kel’s appearance, she kept it to herself. Instead she pointed to yet another piece of writing: Girls Can’t Fight! Salma’s mouth twisted wryly. ‘What do they think their mothers do, when the lords are at war and a raiding party strikes? Stay in their solars and tat lace?’

That made Kel smile. ‘My aunt lit barrels of lard and had them catapulted onto Scanran ships this summer.’

‘As would any delicately reared noblewoman.’ Salma opened the door. Once they had walked into the hall, she took the key from Kel and went about her business, nodding to the boys as they emerged from their rooms.

Kel stood in front of her door and clasped her hands so no one could see they shook. Suddenly she wanted to turn tail and run until she reached home.

Wyldon was coming down the hall. Boys joined him as he passed, talking quietly. One of them was a boy with white-blond hair and blue eyes, set in a face as rosy-cheeked as a girl’s. Kel, seeing the crispness of his movements and a stubbornness around his mouth, guessed that anybody silly enough to mistake that one for a girl would be quickly taught his mistake. A big, cheerful-looking red-headed boy walked on Wyldon’s left, joking with a very tall, lanky youth.

A step behind the blond page and Wyldon came a tall boy who walked with a lion’s arrogance. He was brown-skinned and black-eyed, his nose proudly arched. A Bazhir tribesman from the southern desert, Kel guessed. She noticed several other Bazhir among the pages, but none looked as kingly as this one.

When the training master halted, there were only five people left in front of doors on both sides of him: four boys and Kel. Her next-door neighbour, a brown-haired boy liberally sprinkled with freckles, bowed to Wyldon. Kel and the others did the same; then Kel wondered if she ought to have curtsied. She let it go. To do so now, after bowing, would just make her look silly.

Wyldon looked at each of them in turn, his eyes resting the longest on Kel. ‘Don’t think you’ll have an easy time this year. You will work hard. You’ll work when you’re tired, when you’re ill, and when you think you can’t possibly work any more. You have one more day to laze. Your sponsor will show you around this palace and collect those things which the crown supplies to you. The day after that, we begin.’

‘You.’ He pointed to a boy with the reddest, straightest hair Kel had ever seen. ‘Your name and the holding of your family.’

The boy stammered, ‘Merric, sir – my lord. Merric of Hollyrose.’ He had pale blue eyes and a long, broad nose; his skin had only the barest summer tan.

The training master looked at the pages around him. ‘Which of you older pages will sponsor Merric and teach him our ways?’

‘Please, Lord Wyldon?’ Kel wasn’t able to see the owner of the voice in the knot of boys who stood at Wyldon’s back. ‘We’re kinsmen, Merric and I.’

‘And kinsmen should stick together. Well said, Faleron of King’s Reach.’ A handsome, dark-haired boy came to stand with Merric, smiling at the redhead. Wyldon pointed to the freckled lad, Esmond of Nicoline, who was taken into the charge of Cleon of Kennan, the big redhead. Blond, impish Quinden of Marti’s Hill was sponsored by the regal-looking Bazhir, Zahir ibn Alhaz. The next pairing was the most notable: Crown Prince Roald, the twelve-year-old heir to the throne, chose to show Seaver of Tasride around. Seaver, whose dark complexion and coal-black eyes and hair suggested Bazhir ancestors, stared at Roald nervously, but relaxed when the prince rested a gentle hand on his shoulder.

Only Kel remained. Wyldon demanded, ‘Your name and your fief?’

She gulped. ‘Keladry of Mindelan.’

‘Who will sponsor her?’ asked Wyldon.

The handsome Zahir looked at her and sniffed. ‘Girls have no business in the affairs of men. This one should go home.’ He glared at Kel, who met his eyes calmly.

Lord Wyldon shook his head. ‘We are not among the Bazhir tribes, Zahir ibn Alhaz. Moreover, I requested a sponsor, not an opinion.’ He looked at the other boys. ‘Will no one offer?’ he asked. ‘No beginner may go unsponsored.’

‘Look at her,’ Kel heard a boy murmur. ‘She stands there like – like a lump.’

The blond youth at Wyldon’s side raised a hand. ‘May I, my lord?’ he asked.

Lord Wyldon stared at him. ‘You, Joren of Stone Mountain?’

The youth bowed. ‘I would be pleased to teach the girl all she needs to know of life in the pages’ wing.’

Kel eyed him, suspicious. From the way a few older pages giggled, she suspected Joren might plan to chase her away, not show her around. She looked at the training master, expecting him to agree with the blond page.

Instead Lord Wyldon frowned. ‘I had hoped for another sponsor,’ he commented stiffly. ‘You should employ your spare hours in the improvement of your classwork and your riding skills.’

‘I thought Joren hated—’ someone whispered.

‘Shut up!’ another boy hissed.

Kel looked at the flagstones under her feet. Now she was fighting to hide her embarrassment, but she knew she was failing. Any Yamani would see her shame on her features. She clasped her hands before her and schooled her features to smoothness. I’m a rock, she thought. I am stone.

‘I believe I can perfect my studies and sponsor the girl,’ Joren said respectfully. ‘And since I am the only volunteer—’

‘I suppose I’m being rash and peculiar, again,’ someone remarked in a drawling voice, ‘but if it means helping my friend Joren improve his studies, well, I’ll just have to sacrifice myself. There’s nothing I won’t do to further the cause of book learning among my peers.’

Everyone turned towards the speaker, who stood at the back of the group. Seeing him clearly, Kel thought that he was too old to be a page. He was tall, fair-skinned, and lean, with emerald eyes and light brown hair that swept back from a widow’s peak.

Lord Wyldon absently rubbed the arm he kept tucked in a sling. ‘You volunteer, Nealan of Queenscove?’

The youth bowed jerkily. ‘That I do, your worship, sir.’ There was the barest hint of a taunt in Nealan’s educated voice.

‘A sponsor should be a page in his second year at least,’ Wyldon informed Nealan. ‘And you will mind your tongue.’

‘I know I only joined this little band in April, your lordship,’ the youth Nealan remarked cheerily, ‘but I have lived at court almost all of my fifteen years. I know the palace and its ways. And unlike Joren, I need not worry about my academics.’

Kel stared at the youth. Had he always been mad, or did a few months under Wyldon do this to him? She had just arrived, and she knew better than to bait the training master.

Wyldon’s eyebrows snapped together. ‘You have been told to mind your manners, Page Nealan. I will have an apology for your insolence.’

Nealan bowed deeply. ‘An apology for general insolence, your lordship, or some particular offence?’

‘One week scrubbing pots,’ ordered Lord Wyldon. ‘Be silent.’

Nealan threw out an arm like a Player making a dramatic statement. ‘How can I be silent and yet apologize?’

‘Two weeks.’ Keladry was forgotten as Wyldon concentrated on the green-eyed youth. ‘The first duty for anyone in service to the crown is obedience.’

‘And I am a terrible obeyer,’ retorted Nealan. ‘All these inconvenient arguments spring to my mind, and I just have to make them.’

‘Three,’ Wyldon said tightly.

‘Neal, shut it!’ someone whispered.

‘I could learn—’ Kel squeaked. No one heard. She cleared her throat and repeated, ‘I can learn it on my own.’

The boys turned to stare. Wyldon glanced at her. ‘What did you say?’

‘I’ll find my way on my own,’ Kel repeated. ‘Nobody has to show me. I’ll probably learn better, poking around.’ She knew that wasn’t the case – her father had once referred to the palace as a ‘miserable rat-warren’ – but she couldn’t let this mad boy get himself deeper into trouble on her account.

Nealan stared at her, winged brows raised.

‘When I require your opinion,’ began Wyldon, his dark eyes snapping.

‘It’s no trouble,’ Nealan interrupted. ‘None at all, Demoiselle Keladry. My lord, I apologize for my wicked tongue and dreadful manners. I shall do my best not to encourage her to follow my example.’

Wyldon, about to speak, seemed to think better of what he meant to say. He waited a moment, then said, ‘You are her sponsor, then. Now. Enough time has been wasted on foolishness. Supper.’

He strode off, pages following like ducklings in their mother’s wake. When the hall cleared, only Nealan and Keladry were left.

Nealan stared at the girl, his slanting eyes taking her in. Seeing him up close at last, Kel noticed that he had a wilful face, with high cheekbones and arched brows. ‘Believe me, you wouldn’t have liked Joren as a sponsor,’ Nealan informed her. ‘He’d drive you out in a week. With me at least you might last a while, even if I am at the bottom of Lord Wyldon’s list. Come on.’ He strode off.

Kel stayed where she was. Halfway down the hall, Nealan realized she was not behind him. When he turned and saw her still in front of her room, he sighed gustily, and beckoned. Kel remained where she was.

Finally he stomped back to her. ‘What part of “come on” was unclear, page?’

‘Why do you care if I last a week or longer?’ she demanded. ‘Queenscove is a ducal house. Mindelan’s just a barony, and a new one at that. Nobody cares about Mindelan. We aren’t related, and our fathers aren’t friends. So who am I to you?’

Nealan stared at her. ‘Direct little thing, aren’t you?’

Kel crossed her arms over her chest and waited. The talkative boy didn’t seem to have much patience. He would wear out before she did in a waiting contest.

Nealan sighed and ran his fingers through his hair. ‘Look – you heard me say I’ve lived at court almost all my life, right?’

Kel nodded.

‘Well, think about that. I’ve lived at court and my father’s the chief of the realm’s healers. I’ve spent time with the queen and quite a few of the Queen’s Riders and the King’s Champion. I’ve watched Lady Alanna fight for the crown. I saw her majesty and some of her ladies fight in the Immortals War. I know women can be warriors. If that’s the life you want, then you ought to have the same chance to get it as anyone else who’s here.’ He stopped, then shook his head with a rueful smile. ‘I keep forgetting I’m not in a university debate. Sorry about the speech. Can we go and eat now?’

Kel nodded again. This time, when he strode off down the hall, she trotted to keep up with him.

When they passed through an intersection of halls, Nealan pointed. ‘Note that stairwell. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s a shortcut to the mess or the classrooms. It heads straight down and ends on the lower levels, underground.’

‘Yessir.’

‘Don’t call me sir.’

‘Yessir.’

Nealan halted. ‘Was that meant to be funny?’

‘Nossir,’ Kel replied, happy to stop and catch her breath. Nealan walked as he spoke, briskly.

Nealan threw up his hands and resumed his course. Finally they entered a room filled with noise. To Kel it seemed as if every boy in the world was here, yelling and jostling around rows of long tables and benches. She came to a halt, but Nealan beckoned her to follow. He led her to stacks of trays, plates, napkins, and cutlery, grabbing what he needed. Copying him, Kel soon had a bowl of a soup thick with leeks and barley, big slices of ham, a crusty roll still hot from the oven, and saffron rice studded with raisins and almonds. She had noticed pitchers of liquids, bowls of fruit, honey pots, and platters of cheese were already on the tables.

As they stopped, looking for a place to sit, the racket faded. Eyes turned their way. Within seconds she could hear the whispers. ‘Look.’ ‘The Girl.’ ‘It’s her.’ One clear voice exclaimed, ‘Who cares? She won’t last.’

Kel bit her lip and stared at her tray. Stone, she thought in Yamani. I am stone.

Nealan gave no sign of hearing, but marched towards seats at the end of one table. As they sat across from one another, the boys closest to them moved. Two seats beside Nealan were left empty, and three next to Kel.

‘This is nice,’ Nealan remarked cheerfully. He put his food on the table before him and shoved his tray into the gap between him and the next boy. ‘Usually it’s impossible to get a bit of elbow room here.’

Someone rapped on a table. Lord Wyldon stood alone at a lectern in front of the room. The boys and Kel got to their feet as Wyldon raised his hands. ‘To Mithros, god of warriors and of truth, and to the Great Mother Goddess, we give thanks for their bounty,’ he said.

‘We give thanks and praise,’ responded his audience.

‘We ask the guidance of Mithros in these uncertain times, when change threatens all that is time-honoured and true. May the god’s light show us a path back to the virtues of our fathers and an end to uncertain times. We ask this of Mithros, god of the sun.’

‘So mote it be,’ intoned the pages.

Wyldon lowered his hands and the boys dropped into their seats.

Kel, frowning, was less quick to sit. Had Lord Wyldon been talking about her? ‘Don’t let his prayers bother you,’ Nealan told her, using his belt knife to cut his meat. ‘My father says he’s done nothing but whine about changes in Tortall since the king and queen were married. Eat. It’s getting cold.’

Kel took a few bites. After a minute she asked, ‘Nealan?’

He put down his fork. ‘It’s Neal. My least favourite aunt calls me Nealan.’

‘How did His Lordship get those scars?’ she enquired. ‘And why is his arm in a sling?’

Neal raised his brows. ‘Didn’t you know?’

If I knew, I wouldn’t ask, Kel thought irritably, but she kept her face blank.

Neal glanced at her, shook his head, and continued, ‘In the war, a party of centaurs and hurroks—’

‘Hur – what?’ asked Kel, interrupting him.

‘Hurroks. Winged horses, claws, fangs, very nasty. They attacked the royal nursery. The Stump—’

‘The what?’ Kel asked, interrupting again. She felt as if he were speaking a language she only half understood.

Neal sighed. There was a wicked gleam in his green eyes. ‘I call him the Stump, because he’s so stiff.’

He might be right, but he wasn’t very respectful, thought Kel. She wouldn’t say so, however. She wasn’t exactly sure, but probably it would be just as disrespectful to scold her sponsor, particularly one who was five years older than she was.

‘Anyway, Lord Wyldon fought off the hurroks and centaurs all by himself. He saved Prince Liam, Prince Jasson, and Princess Lianne. In the fight, the hurroks raked him. My father managed to save the arm, but Wyldon’s going to have pain from it all his life.’

‘He’s a hero, then,’ breathed Kel, looking at Wyldon with new respect.

‘Oh, he’s as brave as brave can be,’ Neal reassured her. ‘That doesn’t mean he isn’t a stump.’ He fell silent and Kel concentrated on her supper. Abruptly Neal said, ‘You aren’t what was expected.’

‘How so?’ She cut up her meat.

‘Oh, well, you’re big for a girl. I have a ten-year-old sister who’s a hand-width shorter. And you seem rather quiet. I guess I thought the girl who would follow in Lady Alanna’s footsteps would be more like her.’

Kel shrugged. ‘Will I get to meet the Lioness?’ She tried not to show that she would do anything to meet her hero.

Neal ran his fork around the edge of his plate, not meeting Kel’s eyes. ‘She isn’t often at court. Either she’s in the field, dealing with lawbreakers or immortals, or she’s home with her family.’ A bell chimed. The pages rose to carry their empty trays to a long window at the back of the room, turning them over to kitchen help. ‘Come on. Let’s get rid of this stuff, and I’ll start showing you around.’

Salma found them as they were leaving the mess hall. She drew Kel aside and gave her two keys. One was brass, the other iron. ‘I’m the only one with copies of these,’ Salma told her quietly. ‘Even the cleaning staff will need me to let them in. Both keys are special. To open your door, put the brass one in the lock, turn it left, and whisper your name. When you leave, turn the key left again. The iron key is for the bottom set of shutters. It works the same as the door key. Lock the shutters every time you leave, or the boys will break in that way. Leave the small upper shutters open for ventilation. Only a monkey could climb through those. Don’t worry if any of the boys can pick locks. Anyone who tries will be sprayed in skunk-stink. That should make them reconsider.’

Kel smiled. ‘Thank you, Salma.’

The woman nodded to her and Neal, and left them.

Neal walked over to Kel. ‘If they can’t wreck your room, they’ll find other things to do,’ he murmured. When Kel raised her eyebrows at him, he explained, ‘I learned to read lips. The masters at the university were always whispering about something.’

Kel tucked the keys into her belt purse. ‘I’ll deal with the other things as they come,’ she said firmly. ‘Now, where to?’

‘I bet you’d enjoy the portrait gallery. If you’re showing visitors around, it’s one of the places they like to go.’

After leading Kel past a bewildering assortment of salons, libraries, and official chambers, Neal showed her the gallery. He seemed to know a story about every person whose portrait was displayed there. Kel was fascinated by his knowledge of Tortall’s monarchs and their families; he made it sound as if he’d known them all personally, even the most ancient. She stared longest at the faces of King Jonathan and Queen Thayet. She could see why the queen was called the most beautiful woman in Tortall, but even in a painting there was more to her than looks. The girl saw humour at the back of those level hazel eyes and determination in the strong nose and perfectly shaped mouth.

‘She’s splendid,’ Kel breathed.

‘She is, but don’t say that around the Stump,’ advised Neal. ‘He thinks she’s ruined the country, with her K’miri notion that women can fight and her opening schools so everyone can learn their letters. Anything new gives my lord of Cavall a nosebleed.’

‘Still determined to go to war with the training master, Nealan?’ enquired a soft, whispery voice behind Kel.

She whirled, startled, and found she was staring at an expanse of pearl-grey material, as nubbly as if it were a mass of tiny beads melted together. She stumbled back one step and then another. The pearl-grey expanse turned dark grey at the edges. Looking down, Kel saw long, slender legs ending in lengthy digits, each tipped with a silver claw.

She backed up yet another step and tilted her head most of the way back. The creature was fully seven feet tall, not counting the long tail it used to balance itself, and it was viewing her with fascination. Its large grey slit-pupilled eyes regarded her over a short, lipless muzzle.

Kel’s jaw dropped.

‘You’re staring, Mindelan,’ Neal said dryly.

‘As am I,’ the creature remarked in that ghostly voice. ‘Will you introduce us?’

‘Tkaa, this is Keladry of Mindelan,’ said Neal. ‘Kel, Tkaa is a basilisk. He’s also one of our instructors in the ways of the immortals.’

Kel had seen immortals other than the spidren on the riverbank, but she had never been this close to one. And it – he? – was to be one of her teachers?

‘We basilisks are travellers and gossips,’ Tkaa remarked, as if he had read her mind. ‘I earn my keep here by educating those who desire a more precise knowledge of those immortals who have chosen to settle in the Human Realms.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Kel said, breathless. She started to curtsy, remembered that a page bowed, and tried to do both. Neal braced her before she could topple over. Once she had regained her balance, the red-faced Kel bowed properly.

‘I am pleased to meet you, Keladry of Mindelan,’ the basilisk told her as if he hadn’t noticed her clumsiness. ‘I shall see you both the day after tomorrow.’ With a nod to Kel and to Neal, he walked out of the gallery, tail daintily raised.

Neal sighed. ‘We’d better get back to our rooms. Tomorrow’s a busy day.’ He led her back to her room, pointing out his own as they passed it. ‘We’ll meet in the mess hall in the morning,’ he told her.

Kel used the key as Salma had directed, and entered her room. Everything was in place, her bed freshly made up, curtains and draperies rehung. A faint scent of paint still drifted from the walls. ‘Gods of fire and ice, bless my new home,’ she whispered in Yamani. ‘Keep my will burning as hot as the heart of the volcano, and as hard and implacable as a glacier.’

A wave of homesickness suddenly caught her. She wished she could hear her mother’s low, soothing voice or listen to her father read from one of his books.

Emotion is weakness, Kel told herself, quoting her Yamani teachers. I must be as serene as a lake on a calm day. It was hard to control her feelings when so much was at stake and she was so far from home.

But control her feelings she would. If anyone here thought to run her off, they would find she was tougher than they expected. She was here to stay.

To prove it, she carefully unpacked each porcelain lucky cat and set it on her mantelpiece. Only when she had placed each of them just so did she scrub her face and put on her nightgown.

Climbing into bed, she took a deep breath and closed her eyes. She imagined a lake, its surface as smooth as glass. This is my heart, she thought. This is what I will strive to be.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_3fbffffe-3c0b-5792-bd60-e8a353c6bcfc)

THE PRACTICE COURTS (#ulink_3fbffffe-3c0b-5792-bd60-e8a353c6bcfc)

The next morning Kel heard the chatter of birds. She crept over to her open window and peered outside. It was nearly dawn, with the barest touch of light colouring the sky. Before her was a small courtyard with a single bedraggled tree growing at its centre. On it perched house sparrows, drab in their russet brown and tan feathers, the males with stern black collars. Several birds pecked at the circle of earth around the tree. Kel watched them as the pearly air brightened. Poor things, she thought, they’re hungry.

In her clothespress she had stowed the last of the fruit-bread Mindelan’s cook had given her for the journey south. Kel retrieved it and broke it up into crumbs, then dumped it on the courtyard stones. She was watching the sparrows devour it when the first bell rang and someone rapped on her door. She opened it and said a cheerful good morning to the servant who stood there with a pitcher of hot water.

‘Good is as good does, Page Keladry,’ he said, his long face glum. He placed his burden on her desk. ‘I’m Gower. I’m to look after you.’ He began to sweep out the hearth as Kel took the water into her dressing room.

A new fire was laid when she returned to the main room, her face washed and her teeth clean. ‘If you’ve anything special you require, soap or cloths or such, tell me,’ Gower said sorrowfully. ‘Within reason, of course.’

Kel blinked at him. She’d never met anyone this gloomy. ‘Thank you, Gower,’ she replied, intimidated. ‘I don’t need anything just yet.’

‘Very good, miss,’ he said, then shook his head. ‘I mean, Page Keladry.’

She sighed with relief when he left, and hurried to dress.

Undiscouraged by Gower, she wished Neal a good morning when she found him in the mess hall. He looked at her through bleary eyes and mumbled, ‘There’s nothing good about it.’ Kel shook her head and ate breakfast in silence.

The day flew by. It began underground, where the palace stores were kept. A tailor took Kel’s measurements. Then his assistant dumped a load of garments into her arms. She got three sets of practice clothes, sturdy tan cotton and wool garments to be worn during the morning. She also received three changes of the pages’ formal uniform – red shirt and hose, gold tunic – to be worn in the afternoon and at royal gatherings. Shoes to match her formal gear were added; her family had supplied boots for riding and combat practice. Neal took the cloaks and coats she was given for cold weather.

Once she had stowed her things, Neal took her for another tour. They spent the morning inside, visiting the classrooms, libraries, indoor practice courts, and supply rooms like the pages’ armoury on the first level underground. After lunch, Neal took her to the outdoor practice courts and stables; the gardens, where she might wait on guests; and last of all, the royal menagerie. That night she dreamed the hooting calls of the howler monkeys from the Copper Isles and the chittering of brightly coloured finches.

The next day she woke not to the gaudy finches’ calls or the songs of Yamani birds, but to the friendly gossip of the courtyard sparrows. In hopes of seeing them again, she’d swiped a couple of rolls from the mess hall. Now she tore the rolls up and put the scraps outside the window for the birds.

As she finished, the bell rang. Gower rapped on her door as he’d done the day before, bringing hot water. Once he had cleaned the hearth and gone, Kel got dressed and ran to the mess hall. Her first day as a page had begun.

After breakfast, the pages flocked to one of the practice yards. Kel would take her first steps on the path to knighthood in these wood-fenced bare-earth rectangles and their adjoining equipment sheds. I’ll work hard, she promised herself. I’ll show everyone what girls can do.

Two Shang warriors, masters of unarmed combat, awaited the pages in the first yard. One of them sat on the fence, looking them over with pale, intelligent eyes. Her short-cropped tight grey curls framed a face that was dainty but weathered. She was clothed in undyed breeches and a draped, baggy jacket.

The other Shang warrior stood at the centre of the yard, his big hands braced on his hips. He was a tall Yamani, golden-skinned, with plump lips and a small nose. His black eyes were lively, particularly for a Yamani. His black hair was cropped short on the sides and longer on top. His shoulders were heavy under his undyed jacket. Both he and the woman wore soft, flexible cloth shoes.

‘For those who are new,’ he said, no trace of accent in his clear, mellow voice, ‘I am Hakuin Seastone, the Shang Horse. My colleague, who joined me this summer, is Eda Bell, the Shang Wildcat.’

‘Don’t go thinking you can bounce me all over the ground just because I look like somebody’s grandmother,’ the woman said dryly. ‘Some grandchildren need more raising than others, and I supply it.’ She grinned, showing very white teeth.

Kel saw the redheaded Merric swallow. She agreed: the Wildcat looked tough.

‘You older lads, pair up and go through the first drill,’ ordered Hakuin. ‘Grandmother here will keep an eye on you. As for you new ones …’ He beckoned them over to a corner of the yard. Once they stood before him, the man continued, ‘Your first and most important lesson is, learn how to fall. Slap the ground as you hit, and roll. Like this.’ He fell forward, using his arms to break his fall. The boys jumped; the sound and the puff of dust he raised made the fall appear more serious than it was.

The Horse got to his feet and held a hand out to blond Quinden. When the boy took it, he found himself soaring gently over Hakuin’s hip. Only after he landed did the boy remember to slap the ground.

‘You have to do that earlier, as you hit,’ said Hakuin gently, helping Quinden up. ‘Now.’ He beckoned to Kel and offered a hand.

She took it, meaning to let him throw her as he had Quinden, but the moment she felt his tug, six years of Yamani training took over. She turned, letting her back slide into the curve of his pulling arm as she gripped him with both hands and drew him over her right hip. He faltered, then steadied, and swept Kel’s feet from under her. She released his arm, then tucked and rolled forward as she hit the ground. She surged back up again and turned to face him, setting herself for the next attack.

He stood where she had left him, smiling wryly. Horrified, Kel laid her hands flat on her thighs and bowed. She expected a swat on the head or a bellow in her ear – Nariko, the emperor’s training master, had had no patience with people who didn’t complete a throw or counter a sweeping foot.

When no one swatted or bellowed, she looked up through her fringe. Everyone was staring at her.

Kel looked down again, wishing she could disappear.

‘See what happens when you get too comfortable, Hakuin?’ drawled the Wildcat. ‘Someone hands you a surprise. If you’d been a hair slower, she’d’ve tossed you.’

‘Isn’t it bad enough I am humbled, without you adding your copper to the sum, Eda?’ the Horse enquired. ‘Look at me, youngster,’ he ordered. When Kel obeyed, she saw Hakuin’s black eyes were dancing. ‘Someone has studied in the Yamani Islands.’

‘Yes, sir,’ she whispered.

‘Your teacher was old Nariko, the emperor’s training master, am I right? She always did like that throw. She drilled me in it so many times I wanted to toss her into a tree and leave her there.’

Kel nodded, hiding a smile.