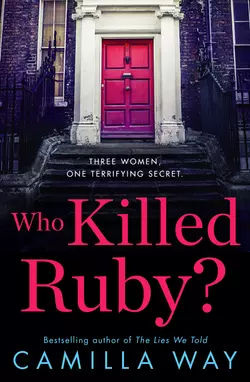

Who Killed Ruby?

Camilla Way

‘Gripping psychological suspense’ Fiona Barton, Sunday Times bestselling author of The Child ‘Keeps you guessing till the very end’ Cara Hunter, author of All The Rage You never know what’s going on behind closed doors… If you passed it on the street, you’d see an ordinary London townhouse. You might wonder about the people who live there, assume they’re just like you. But inside a family is trapped in a nightmare. In the kitchen, a man lies dead on the blood-soaked floor. Soon the police will come, and they’ll want answers. Perhaps they'll believe the family’s version of events – that this man is a murderer who deserved to die. But would that be the truth? Perfect for fans of Clare Mackintosh, Cara Hunter and Ruth Ware Praise for Camilla Way: ‘An original page turner’ Sun ‘A top class psychological thriller, smartly crafted and oozing tension’ Sunday Mirror ‘Adds pace and suspense in a way that’s refreshing for even the most jaded of readers’ Stylist

Copyright (#ulink_f35f8dc2-23c8-53bd-8bc0-cc173d1ec8e3)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Camilla Way 2019

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Magdalena Russocka / Trevillion Images (http://www.trevillion.com)

Camilla Way asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008280994

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008281014

Version: 2019-05-20

Dedication (#ulink_f35f8dc2-23c8-53bd-8bc0-cc173d1ec8e3)

For my mum, Anna Way, with love

Contents

Cover (#u63db8518-6930-59de-917c-c9bab7e0a78b)

Title page (#uf66d3e13-6939-54d9-970a-d868e6531de2)

Copyright (#ue9769e4d-9f96-5269-ab3a-2bb1cda95a03)

Dedication (#udfe07142-3654-57ba-be9a-e4e662e85973)

Chapter 1 (#u892a4930-64ad-5b12-b52e-2d41e58622ce)

Two Months Earlier (#ub1b82d69-bc8c-53cf-a0aa-8ed93900a03f)

Chapter 2 (#ufbf1edaf-1942-5cd1-939a-29f7224a9be9)

Chapter 3 (#u6bd74f06-5a8d-5ea9-a208-1cb9e1213b30)

Chapter 4 (#uac3b138a-fed8-5c6f-889e-bd8129d69a0d)

Chapter 5 (#u1898f9aa-7493-5995-b6e9-91ea0a7cd631)

Chapter 6 (#u22ea7581-ef18-5057-9b5e-ee9ade11f455)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight Months Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Camilla Way (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_5424dc0a-45e2-5db4-b54f-4d02eff2f8b1)

They stand there, the three of them, looking at the dead man, his blood creeping slowly across the floor. Despite the savagery of his death the room is very still, almost peaceful after the violence that has led to this.

Soon the police will come. They will charge into this nice expensive kitchen in this rather lovely London townhouse with their boots, their batons, their loud authority, and will want to know what happened, whom to hold responsible.

It’s Vivienne who speaks first. ‘What will we do?’ she asks, her teeth chattering with shock. ‘What will we tell them?’

The seconds drip by slowly until her mother at last replies. ‘We will tell them that this is the man who murdered Ruby,’ she says.

TWO MONTHS EARLIER (#ulink_9ad6de8d-f74b-5d3a-a9e8-b069db1377d7)

2 (#ulink_2ee27c35-acd6-55a8-a0f1-ab5ff0eeeedc)

It’s almost closing time. Outside on the dark Peckham street rain falls on flickering puddles. A man, weaving in and out of traffic and clutching a can of cider, thumps his fist on idling cars. Beyond him the Rye lies abandoned, its rain-soaked lawns and gardens, ponds and playgrounds cloaked in darkness now.

Vivienne checks her watch: ten to six, only three tables occupied still. Walton, the elderly Trinidadian who calls in most days, finishing his slice of vanilla sponge; a teenage couple on table number four, eyes locked, hands clasped over tea long gone cold. And the doctor. Her gaze flickers over him then away again as it has for the past hour, as it does every time he arrives and takes the same corner table, asking for strong black coffee, pulling a notepad from his jacket pocket and beginning to write. His fingers barely pause as the words flow in a language she doesn’t recognize. She has noticed herself waiting for him each day.

Soon Vivienne begins to shut up shop, pulling the blinds down, collecting menus and sugar bowls. ‘Closing now,’ she calls.

The teenagers leave first, with Walton close behind. ‘Goodbye, Elizabeth Taylor. Goodbye!’ he says. ‘See you tomorrow!’

She smiles and waves him off, turning back to find the doctor standing only a few feet away and she jumps to find him suddenly so close. ‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘Two coffees, was it? Three eighty, please.’

‘Elizabeth Taylor?’ he asks as he hands her the money.

It’s the first non-coffee-related thing he’s said to her. ‘Reckons I look like her, daft sod.’ She laughs to show the absurdity of it, and he smiles politely.

‘This is a nice place.’ He nods towards the pink neon sign in the window that says Ruby’s. ‘And this is your name? Ruby?’ His accent curls around the words. Is he Russian, she wonders. Polish?

‘Oh, no, I’m Viv. Ruby was my sister but she died when we were young.’

He glances at her. ‘I see. I’m sorry for your loss.’

She waves her hand breezily to show how over it she is, though in truth the very thought of Ruby makes her throat thicken, even now. ‘You live near here?’ she asks, to change the subject.

‘I work at the hospital.’ He nods in the direction of King’s College and she affects a look of surprise, as if she hadn’t already clocked weeks ago the NHS tag hanging around his neck, the name Dr Aleksander Petri in black type.

‘Well,’ he pats his pockets as if looking for something and she lets her gaze flicker over him again. He has a kind face, she thinks; his almond-shaped eyes thick-lashed and so dark as to be almost black, his mouth— ‘I must go,’ he says, jolting her from her reverie. ‘Thank you for the coffee,’ and then he is gone, the door thudding gently closed behind him.

Her friend Samar arrives moments later, his hair wet with rain. ‘Was that him?’ he asks, clapping his hands together for warmth. ‘Dr Feelgood?’

‘Yep.’ She fetches the broom to sweep the floor.

‘And?’ He looks at her expectantly. ‘Any progress?’

‘Nope.’ She pronounces the word so that it ends with a satisfying ‘puh’ and Samar rolls his eyes.

‘Ask him out, for God’s sake.’ He follows after her, helping her lift chairs onto tables. ‘Did I tell you Ted’s taking me to Paris?’ he says after a while, with unconvincing nonchalance.

She stares at him. ‘You’ve only just got back from Amsterdam! Jesus, how many romantic mini-breaks does one couple need?’ But she sees the glow in his eyes, sees how the person he was has been transformed by love, and sighs. ‘Ask if he’s got any single straight friends, will you?’

Half an hour later Viv turns the corner into Chiltern Avenue. It’s a wide, tree-lined street, the Victorian semis large and impressive, set amongst spacious, well-kept gardens. She sees her mother’s house ahead and quickens her pace as the rain picks up. Her mum’s corner of Peckham has changed almost beyond recognition in the quarter of a century that she’s lived here, the slow and steady creep of gentrification transforming what was once a shabby, unfashionably edgy part of south-east London into something shiny and desirable, the original demographic squeezed out family by family as loft and kitchen extensions, four-by-fours and a general sheen of exclusivity and wealth has taken its place.

Only her mother’s house stands out from the homogenized, sanitized crowd. Number 72 is a faded kaleidoscope of colours; the paintwork a peeling turquoise, the guttering a weather-beaten red, the door a washed-out yellow. In the front garden rainbow-striped windmill spinners tatty with rain and mud poke up through banks of weeds, and the bent browned husks of long-dead sunflowers bow before a brass sculpture of a naked woman, her breasts and belly green with the passage of time. A trio of wind chimes hang from the branches of a leafless sycamore, their music mingling with the rain.

As usual the front door rests on its latch and Viv pushes it open with a sigh of disapproval but steps into the light, high-ceilinged hall to feel the house’s familiar pull, its peaty, musty smell of boiling pulses; the spicy sweetness of sandalwood and patchouli, and she relaxes into its warmth and familiarity. Her mother runs a sort of boarding house for the waifs and strays of South London: the abused, the addicted, the lost and the lonely. Sent to her by local refuges, psych wards and rehab centres, her guests take up residence in one of the many light and airy bedrooms, some for a few weeks, others for a few months, until they are deemed fit to return home or are found a more permanent place elsewhere. The most cursory of glances reveals this is not a lucrative enterprise, yet somehow the house’s colour, character and atmosphere transcends the worn furniture, the splintering floorboards and grubby paintwork.

To the right of the hall is the kitchen and Vivienne enters it now to find her daughter Cleo seated at the large pine table, her head bowed over her school books, half of which are obscured by an enormous ginger tom lying supine across them, his vast furry belly vibrating with loud contentment. A lightshade made from many pieces of coloured glass throws rainbow squares across the wide, well-worn floorboards. The walls are covered in a jumble of art prints and black-and-white photographs, an Amnesty International poster, a framed Maya Angelou quote. Books crowd together on the shelves; texts on feminism and politics and spiritualism and psychology, and Vivienne doesn’t know if her mother has ever read these books, has never in fact witnessed her read any of them, but supposes that she must have, once.

She goes to her daughter and kisses the top of her head. ‘Where’s Gran? Sorry I’m late, Sammy popped in.’

Cleo looks up at her distractedly, her school tie tugged half out of its knot. ‘That’s all right. Can we go home now? I need to—’

She’s interrupted by the appearance of her grandmother. Stella seems to sail rather than walk into any room she enters. She’s an impressive sight; tall and statuesque, her long grey hair dyed a faded magenta. She wears a voluminous kaftan in shades of green and red with a necklace of brightly painted African beads. She’s in her mid sixties but, rather like her home, the heady mix of colour and flair surpasses the general wear and tear of age and one is aware only of her attractiveness.

Stella’s voice is deep and rich, and seeing her daughter she says, ‘Oh, hello, darling. Now, I came in here for something, but I have absolutely no idea what it is.’ She wanders over to the stove to poke at something simmering there with a spoon. ‘Would you like some nettle and elderflower tea? It’s homemade.’

They are alike, physically, although at five foot six Viv doesn’t quite have her mother’s impressive stature, something she’s both relieved and a little regretful about. ‘Christ, no,’ she says, then takes a seat and asks, ‘who’ve you got staying here at the moment, anyway?’

‘Just four: a new woman came last night, the others I think you’ve met – we still have Shaun, of course.’

She says the name fondly, just as Vivienne inwardly shudders at the mention of Stella’s long-standing guest. Hastily she turns back to her daughter. ‘Did you manage to finish your project, love?’ she asks.

But before Cleo can reply, Stella interjects with a crisp, ‘I doubt it. She’s spent most of her time fiddling with that phone of hers.’

As if on cue, Cleo’s mobile pings and she snatches it up eagerly, while Stella sighs.

Vivienne has noticed a hint of discord recently, like a cold draught blowing between her daughter and mother. It’s nothing she can put her finger on, just an occasional, troubling tension that she’s not entirely sure she’s imagined. She looks at Cleo, tapping furiously on her phone, her school books abandoned. She doesn’t share her and Stella’s pale skin, dark hair and violet-blue eyes, but instead has the same strawberry blond curls, the creamy, freckled complexion and wide, pale green eyes of Ruby. In fact, in recent months a passing expression or angle of Cleo’s face will bring Viv’s dead sister back so vividly that it sometimes makes her heart stumble. Perhaps that’s what’s behind the occasional frost she detects in her mother’s tone when she talks to her granddaughter: perhaps pain is at its root; the three of them have always been so close, after all.

Stella’s landline rings and she picks it up to embark on a long and involved conversation about a mindfulness workshop she’s hosting, and a few minutes later a young woman comes in, dark-haired and painfully thin, her small awkward frame a collection of sharp angles clothed in black. She startles at the sight of Vivienne, her eyes darting from her to Cleo with a look of panic as she backs away. ‘No, please don’t go,’ Viv says gently. ‘Are you OK? Would you like something?’

The woman plucks anxiously at her skirt. ‘No. I …’ She turns to leave, but just then Stella hangs up the phone and goes to her. ‘Jenna, how are you feeling?’ She puts an arm around her. ‘Headache gone now, is it?’

Visibly relaxing, she looks at Stella gratefully. ‘Yes, thank you,’ she whispers. ‘I thought I’d make a cup of tea.’

She has that effect on people, her mother, on the waifs and strays that she collects, has always collected, in one way or another. They all adore her. Even before she turned this house into a refuge, they would find her, seeking her out, sensing within her a place of comfort and safety. Viv watches as the young woman is steered towards the kettle, Stella’s hand upon her shoulder.

Cleo looks up to check that her mother’s attention is elsewhere, then turns back to her phone. It vibrates to indicate there’s a new message, and her heart leaps.

Cleo?

Hey.

Hey. Where were u yesterday? Missed u.

She stares at the words in surprise. He’s never said anything like that before. Had to do something with Mum, she writes.

K. Wot u up 2?

Nothing much. Homework.

She beams back at the little smiling face. They met on a Fortnite board on a gaming site a few months back. It’s only recently they’ve begun private messaging. His name is Daniel and he’s a year older than she. He’s told her he lives near Leeds and she’s told him she’s in London. Yesterday he sent her a picture of himself – a blond-haired boy smiling shyly beneath a beanie hat – and she’s been thinking about him ever since.

U there?

Yeah.

Thought I’d scared U off wiv my pic. Lol.

Course not. It’s nice.

Thanx. U got one?

She hesitates, but nevertheless her thirteen-year-old heart feels a thrill of excitement. Maybe, she writes. She glances at her mum, sees that she’s watching her, and hastily drops the phone.

‘Who’s that you’re texting, love?’

‘Just Layla.’ She’s a bit scared how easily the fib trips off her tongue. She doesn’t usually lie to her mum, or that is, only about how many sweets she’s had, or if she’s got any homework to do. But her mother only nods and turns back to the weird thin lady who looks terrified of everything.

Cleo knows she’s not got much time. She wants to give him something more and quickly writes, Gtg, spk 2mrw and then, before she can stop herself, she adds a

then stares at it in horror. Why did she do that? Seriously, why? That’s not cool. That’s so babyish, so … and then he’s replied. And he’s put a

too and she grins in relief.

‘Come on,’ her mum says to her, handing her her coat. ‘It’s time to go.’

Viv watches her daughter gather her books with painful slowness and tries to hide her agitation. She can hear Shaun’s voice from somewhere above, a door opening and then closing again, the sound of footsteps on the stairs. She resists the urge to drag Cleo away, her coat half hanging off her.

It happened a few weeks ago. Stella had gone away on a weekend yoga retreat and, as Cleo was on a rare visit to her father’s, had asked Vivienne to look after the house and guests in her absence. She’d been doing the books for the café at the kitchen table with a glass of wine when Shaun appeared.

He’d been staying there for a month by then, but they’d never made much more than small talk before. She tried to remember what Stella had told her about him: a recent spell in rehab for drugs, she thought. He had walked into the kitchen and stopped when he saw her, then leaned against the fridge, appraising her, a rather cocksure smile upon his face. ‘You in charge of the asylum tonight then?’ he’d asked.

She’d laughed. ‘Something like that.’

He sat down opposite her then, and she was slightly taken aback by his sudden proximity. He was tall and well built, with a broad Mancunian accent and was, she would guess, in his late thirties, tattoos covering his muscular arms, a somewhat belligerent air.

She’d looked back at him levelly. ‘So, how’re you finding it here? Settled in OK?’

He shrugged. ‘Yeah, it’s sound. Your mum’s all right, ain’t she?’ He stretched and yawned, the hem of his T-shirt rising up to reveal a flash of taut stomach. ‘She’s a character, any rate. Looks like a right old hippy and talks like the queen. What is she, some kind of aristo, slumming it with the proles?’

Viv had smiled and murmured a non-committal, ‘Hardly.’ The fact was, Stella’s parents had most certainly been wealthy, but Viv had never met them. Stella had been estranged from them since before she was born, and her and Ruby’s childhood had been anything but privileged.

‘Well, any road,’ Shaun said then, ‘knows what she’s about, don’t she?’ He nodded at her ledger book. ‘What you doing there, then?’

So Vivienne had told him about her café.

‘Done all right for yourself, haven’t you?’ Though he’d been smiling, there was a hint of resentment in his tone. He’d pulled out a tin of tobacco, begun rolling a cigarette, and started telling her about his misspent youth in Manchester. He was entertaining; funny and quick-witted, though she sensed this was a well-worn charm offensive, that there was an unpredictability hiding behind his smile and his mood might change in an instant. She’d met men like him before. She had, too many times in her youth, slept with men like him before, the sort whose swagger and bravado was a front for damage and gaping insecurity, who triggered her instinct to appease, pacify and bolster.

He was exactly the sort of man, in fact, that she had trained herself to avoid. ‘Your problem is, you go for lame ducks,’ Samar told her once. ‘It’s your saviour complex. You must get it from your mother.’ It was unfortunate that Shaun was so very good looking.

He had just finished telling her about how he and his school friends had stolen a milk float when suddenly he’d disarmed her by saying, ‘You’re one of those women who don’t know how fit they are, aren’t you?’

And it was so clichéd, such an obvious line, yet even as she’d rolled her eyes she’d felt a reluctant thrill. Probably because she’d recently turned forty and no one (apart from Walton) had said anything even vaguely complimentary to her for quite some time. And she hated herself for it, saw by the flash in his eyes that he’d seen his words had hit their mark, and if she’d drunk a little less wine, or been a little less giddy at finding herself childfree for the first time in months, she might have put him firmly in his place.

Instead she’d laughed, ‘Oh do me a favour,’ and he’d grinned back at her, the air altering between them, both of them knowing now what the score was. She’d poured herself another drink, enjoying the back and forth of flirtation, telling herself it would only go so far: she would finish her wine then go upstairs to bed, alone. But, of course, it didn’t happen quite like that.

And when she’d woken up the next morning in his bed she’d been full of self-loathing and regret. Sleeping with Stella’s guests was about as stupid as it got, and her mother would be furious if she found out. She’d slipped from the bed, silently scooping up her clothes and escaping to Stella’s room – where she was supposed to have slept that night. Knowing that her mum was due back later that afternoon, she’d fled for home as soon as she could, before Shaun even had time to surface.

She’d managed to avoid him for a while after that and life had gone on, though she’d shuddered whenever she thought of him. She’d only just begun to forgive herself, to hope she’d got away with it when, unexpectedly, he’d called her.

She’d answered her mobile as she was rushing to fetch Cleo from a party.

‘All right, Viv. How’s tricks?’

‘How did you get my number?’ she asked, before remembering with a sinking heart that it was pinned to the corkboard in her mother’s kitchen, the ‘in case of emergencies’ contact for when Stella was out.

‘Well, that’s not very friendly, is it?’

‘Sorry. I …’

‘Wanted to know if you fancied a drink.’

‘Um, I’m not sure that’s a good idea,’ she’d replied slowly.

‘Oh, right, like that is it?’ His voice was instantly hard, the fragile ego she’d sensed lurking there revealed in a heartbeat.

‘No, of course not,’ she’d said hastily. ‘I’m just not … I’m sorry, but I don’t want to get into anything, we probably shouldn’t have …’

He’d given a belligerent laugh. ‘Think you’re too good for me, is that it? Should have been grateful, saggy old bitch.’ His sudden aggression had stunned her. He’d cut her off, leaving her to stare down at her phone, her heart pumping with shock and anger.

That had been two weeks ago. She’d not seen him since, had managed to avoid coming to her mother’s house until today. But as she and Cleo finally get to the door, Shaun appears at the top of the stairs. He stops, looking her up and down insultingly, and she feels a flash of cold dislike.

‘Going so soon?’ he says, sauntering down towards her.

She puts her hand on Cleo’s shoulder and steers her towards the door. ‘Yep, gotta run. Bye.’ She and Cleo go out into the night, and she closes the door firmly behind her, a shiver of disgust prickling her skin.

Their house is a twenty-minute walk from Stella’s, on the other side of the Rye, and Vivienne pushes Shaun from her thoughts as she links her arm through her daughter’s. ‘How was school today, love?’ she asks.

For a while they chat about a history project Cleo’s been working on and how she thinks her team will do in an upcoming football match, and Viv smiles down at her, her happy, popular child, always tumbling from one enthusiasm to the next. She’d been twenty-six when she’d become pregnant, a result of a brief and unhappy fling with one of the suppliers for her café, a handsome but feckless Irishman named Mike who was a few years younger than herself. He’d run a mile at the news of her pregnancy and had kept only sporadic contact with his daughter since. It had always been the two of them after that, and as a result they’d always been close – as close as Viv was to her own mother, in fact.

As they draw nearer to their street Vivienne shivers in the cold November night and murmurs, ‘Thank God it’s Friday. I can’t wait to get home. We’ll have spaghetti for tea, shall we?’

They pass beneath a street lamp just as Cleo looks up at her and smiles, and there is, again, something in the angle of her face, in the expression in her eyes, that takes Viv’s breath away. Her daughter looks in that split-second so exactly like Ruby that her sister is brought back to life with sudden, shocking force.

It’s a new thing, Cleo’s random expressions triggering this heart-jolting reaction in her. Out of the blue a memory will turn up, glinting and sharp, to stop Viv in her tracks. Tonight she’s transported back to the little house in Essex where she and Ruby spent their childhood, a white, ramshackle cottage on the edge of a stretch of fields. In this memory Ruby is sixteen and heavily pregnant, dressed in a blue cotton dress and standing by the window that’s crisscrossed with iron latticing, the light falling on her red-gold hair, her hand resting on her swollen belly.

Viv, aged eight, had gone to her sister and pressed her cheek upon her tummy, gazing up at her as she listened intently. And then it happened: as Ruby smiled down at her with the exact same expression that she’ll see mirrored in her own daughter’s face thirty-two years later, Vivienne felt something move beneath her cheek and squealed in excitement. ‘Did you feel that?’ she asked. ‘I felt him! I felt the baby kick!’

And Ruby grinned and said, ‘Yes, I felt it too. Not long to go, Vivi. Two weeks and you’ll be an auntie.’ An auntie at eight years old! How important and grown-up and wonderful that felt. She would love this baby with all her heart; she did already.

But she never got to meet her sister’s child, never had a chance to call him by the name Ruby had so carefully chosen. Noah. Her nephew would have been called Noah. Because almost two weeks later, a few days before her due date, Ruby would be dead, and Noah with her.

Now, walking along the dark street with her own child, a passing motorbike rouses her from her thoughts. Seeing that they’ve nearly reached their gate she swallows back the shards of pain that have risen to her throat. ‘Come on,’ she says to Cleo, opening the door. ‘Go and get changed and I’ll make dinner, then we’ll watch something on Netflix, shall we?’

Alone in the kitchen, she puts the radio on and pours herself a glass of wine. She hates it when this mood descends upon her. It’s the anniversary of Ruby’s death on Monday and it always upsets her, no matter how prepared for it she is. Noah would have turned thirty-two this year, and as she has done every single year since it happened, she imagines the person he might have become – from toddler, to schoolboy, to teenager and young man – a sadness gathering inside her that’s hard to shake off. ‘Come on, Viv, get a grip,’ she tells herself and, tuning the radio to a music station, she turns the volume up, then starts to put together the ingredients for spaghetti bolognese.

3 (#ulink_865c9e48-3477-5337-9e9e-fb4d1c2afaf4)

There’s so much of that day that she doesn’t remember. She knows that she was the only other person in the house when Ruby was killed. That it was she who found her sister’s body, hugely pregnant, splayed out across her bedroom floor. She knows that it was her evidence that helped put Ruby’s murderer away. But though Viv knows what she said she saw, she cannot link those words to any clear, concrete images, as though the details are locked inside a box she has no access to. She’s been told that this is common; the mind’s way of protecting her from the trauma of that day, but still those buried memories won’t let her be, tapping and scratching at the box’s lid, as though willing her to relent and let them back out.

Even the time before the murder is hazy, her life in that little white cottage only returning to her in flashes. They were very poor, she remembers that. Viv and Ruby, eight years between them, each had different fathers; men who were bad and made their mother sad and who they learned never to ask about because they were gone and that was all. The house was down a narrow lane with four other cottages. She sees the patio tiles outside it, dandelions poking through the cracks, an old, abandoned swing set on the patchy lawn, the fields stretching out beyond. Inside, the rooms were sparsely furnished, the panes loose in the casement windows, the wind whistling through the gaps. In her bedroom under the eaves a pattern of pink and red roses crept across the walls. Her sister’s identical one was across a narrow corridor, a quilt on the bed of orange and turquoise and green.

And what does she remember of Ruby, before it happened? She knows that she loved her sister more than anyone or anything, that Ruby would take Viv into her bed to comfort her at night when she was sad or frightened. She remembers Ruby’s collection of china pigs lined up on her dressing table, the posters of handsome pop stars on her walls, the sweet floral perfume she used to wear, how she’d throw her head back and laugh wholeheartedly, her green eyes dancing. All those things he took from her; all her spirit and love and smell and warmth and kindness, Jack Delaney took them all.

Everything changed when Jack came into their lives. Overnight, Ruby seemed to become someone else; someone else’s. From the moment she met him her sister glowed, her eyes dreamy and lit with something Viv couldn’t guess at, her thoughts seemingly always filled with him. Ruby would wait for Jack at the window, ignoring Viv, staring eagerly down the lane for his car to appear, or else sit next to the phone, willing it to ring. Ruby told her that they’d met at the pub where she worked on Saturdays collecting and washing glasses. Jack had been sitting at the bar with the three other Delaney brothers, and Viv would picture him with his cigarette and his black hair and his thin-lipped smile and his stupid car parked outside, and feel a hard knot of dislike grow ever tighter in her belly.

Until then Vivienne’s experience of men had been confined to the ghostly, forbidden spectres of her and Ruby’s unmentionable fathers, her teacher Mr Kendal, or the kindly dads of her friends, or even Morris Dryden, the butcher’s grown-up son whom everyone said was soft in the head but whom Viv liked best of all. But Jack was different. Even at eighteen he oozed a complicated, threatening thing that was linked somehow to that new light in Ruby’s eyes, and the time Viv caught them kissing, Jack’s hands up her jumper as though rummaging for change. Slowly, however, Ruby began to alter, her usual glow and happiness seeming to ebb away until bit by bit it had disappeared completely.

Their mother hated Jack, she remembers that too; how she’d hear her and Ruby argue, Stella saying he was a thief and a troublemaker and that everyone in the village knew what he was like, what he and his brothers got up to, fighting and stealing and causing trouble. And Viv would think that her mother didn’t know the half of it, that when she went out to work Jack’s oily smile and fake politeness vanished and the real him would appear, like worms slithering from under rocks. She would see how he would change, a black mood creeping over him like the sun had gone in, how Ruby’s voice would turn pleading and tearful at his meanness and his temper. He was always cross with her about something: about how she’d looked at one of his friends or spoken in a way he didn’t like. And yet Ruby loved him, wanted to make him happy, her voice appeasing, cajoling, desperate to the end.

When Ruby got pregnant their mum said Jack Delaney was never to set foot in her house again, but as soon as Stella went off to the care home she worked at, there he’d be, Vivienne sworn to secrecy. He seemed to get worse, the bigger Ruby’s belly got. Viv would sit in the living room in front of the black-and-white TV and listen to their arguing; his rough, bullying voice, her sister’s tearful apologies, and her little hands would ball into fists, willing it to stop.

And what does she remember of that day, the day of Ruby’s murder? She remembers her sister waiting for Jack upstairs at her bedroom window as usual, running down to answer his knock and calling, ‘Don’t tell Mum, Vivi, OK? Don’t tell Mum that Jack was here.’ How she’d heard the disappointment in Ruby’s voice when she discovered it was only sweet, daft Morris Dryden, come to drop off some chops for their mum. A few minutes later, after Morris had left, she heard the second knock at the door, Jack’s voice this time, Ruby’s high, anxious one after she’d returned downstairs to let him in.

Viv had stayed in the living room, keeping out of his way, but still she heard when they’d begun to argue, heard Ruby’s desperate tears, Jack’s relentless, mocking cruelty. That day there’d been something different about their fight though, something terrible and out of control that made Viv’s heart hammer, made her chew her lip until it nearly bled. And then a scream, a heavy thud, followed by the worst, deepest silence she’d ever known. She’d waited, scarcely breathing, until she heard his tread on the stairs then the front door swinging shut behind him and as soon as she’d dared, she’d crept from the room and tiptoed up to Ruby’s. She’d known she was dead, felt it deep inside of herself, a scream of horror trapped in her throat as she stood at the door, gazing down at her sister’s lifeless body, her poor, bleeding head where she’d hit it as she fell, her green, sightless eyes.

It was the police who found Vivienne eventually; navy blue arms plucking her from the safe darkness of Stella’s wardrobe where she’d gone to hide, clothes brushing against her cheek as she was pulled into the cold brightness where the rooms were full of police and the air full of her mother’s sobs at what she’d found when she’d returned home from work.

Later, Vivienne would be told that she’d said nothing when they found her, that she’d continued to say nothing except for the one word she repeated over and over: ‘Jack.’

Over the following days and weeks, a kind and patient lady with thick round glasses, a turquoise jumper and a gentle voice had, while Stella held her hand, coaxed from her the evidence they’d needed to put Jack Delaney away for good. She’d told how she’d heard him in the house that morning, had heard him shouting at her sister, then Ruby’s terrible cry, the thump as her body hit the floor. Of course Jack had killed Ruby; who else could it have been? There was Morris Dryden’s account too; the butcher’s son telling how he’d passed Jack in the lane after he’d dropped off his delivery. And Declan Fairbanks, their neighbour, who’d seen Jack running from the house ten minutes later, and all the other locals who’d witnessed his bullying behaviour towards his pregnant girlfriend in the months leading up to her death.

Jack Delaney was responsible. There could be no mistake.

After the trial, Stella would sit immobile at the kitchen table for hour after hour, week after week, steeped in grief. It seemed to Vivienne as though all the darkness in Jack had poured into her mother: when Viv looked into her eyes she saw the same dull fury that had once burned in his.

The letters began to arrive soon after. Folded pieces of paper deposited like petrol bombs through the letter box during the night. At first she would bring them to Stella, who would turn away without looking at them, so Vivienne would go to Ruby’s room, where the row of china pigs still stood on the dressing table, where the handsome pop stars still grinned their 100-watt smiles, and she would sit on the bed and wrap the orange and turquoise quilt around herself and begin to read.

They were all from the Delaney family, from Jack’s mother or uncle or brothers. Those from his mother were pleading, desperate. You’ve made a mistake. Please please tell the truth. He’s only 18. He never did it. You know he never did it. He’d never kill no one, please, please make them see. But the ones from his brothers and his uncles were angry, threatening; written in thick black capitals that all but tore through the page: Your daughter’s a lying little bitch. Make her tell the truth. And, You and your brat are fucking liars. Watch your back. She would read them with terror rising inside her. At night she’d lie in her bed and tremble, listening for the letter box to rattle. But Viv hadn’t lied. She had heard him that day. She had told the police she did, so it must have been true.

In a matter of months, the life Viv had always known would be gone forever, though she didn’t know then the changes that were to come. Meanwhile, neighbours and kindly villagers helped take care of her. They looked at her with misty-eyed pity, picking her up from the village primary and taking her home with their own kids; to warm, busy, noisy houses with Danger Mouse on the telly and fish fingers in the oven. Your mum just needs a bit of time, they’d say. She’ll be all right, you’ll see. Later, Viv would be taken back home, to where the temperature seemed to drop twenty degrees and the silence pressed against the walls, to where Stella hadn’t seemed to move from her position at the kitchen table in weeks.

Stella never went back to her job at the care home. The letters from the letting agency piled up on the doormat amongst brown ones with ‘Final Demand’ stamped upon them. When bailiffs pounded on their door Stella behaved as though she couldn’t hear them and Viv was too afraid to let them in herself. Similarly, she learned not to pick up the phone when, relentlessly, it rang, and neither of them noticed when the line was finally cut off.

Only one day stands out from the grinding darkness of those weeks. On an April morning five months after Ruby’s death, Vivienne came downstairs in her uniform ready for school to find a surprising sight. Her mother, up and dressed and ready to go out. ‘Put your coat on, Vivienne,’ she said without looking at her.

Viv hadn’t moved. ‘Where are we going?’

The reply had been astonishing. ‘To see your grandparents,’ Stella had said.

The journey had been a long one, taken first by train then coach to a faraway rain-drenched city and followed by another journey by bus to a small village. She could tell by the look in her mother’s eye that it wasn’t the time for questions, so she’d sat quietly next to her, holding her hand, trying not to worry. She’d never met her grandparents before and she wondered what they might be like. Her mother had only ever told her that they lived far away, and that she hadn’t seen them for a long time, and something had made Viv know not to push for more.

When they’d arrived, the house had been very large and beautiful, surrounded by rolling countryside. Vivienne, told to wait at the gate, had watched as her mother traipsed up the long drive, approached the door and knocked. A grey-haired man had answered, and Viv never knew what was spoken between them, only that minutes later the door had slammed shut, Stella had returned to where she waited and said in a voice as heavy as stones, ‘Get up, Vivienne. There’s nothing for us here.’

They’d made the return journey mostly in silence, her mother lost in thought and unreachable. It was late when they got back to their cottage and for some time they had stood staring at the front door, the moonlight revealing what was painted there in vicious foot-high letters: LIARS.

4 (#ulink_1eb76ab3-2916-574c-b839-b72616f872d3)

It was a few weeks after that when Vivienne’s life in Essex came to an abrupt end. Viv had returned home from school one day to find Stella packing their one and only suitcase. ‘We’re moving to London,’ she’d said as Viv watched her, wide-eyed. ‘Take that uniform off and throw it in the bin.’ Then she’d tossed her Ruby’s little green rucksack. ‘Put whatever you can fit in there, the rest we’ll leave. Let that pig of a landlord deal with it.’

They left there and then, taking a bus to the nearest station to catch a train to a new life. She had sat across from her mother, her bag of belongings on her lap, and tried to make sense of it all. Were they leaving because of Jack’s family? Or because they had no money left to pay the rent? She had sneaked a glance at her mum, and thought she understood: Ruby’s death was too sad, too terrible, to do anything else but run from.

For the first few months of their new London life they’d moved from place to place, to the spare beds or sofas belonging to ‘friends of friends’, or the sister of someone Stella used to work with. Sometimes Viv thought about the toys and bedroom she’d left behind, she thought of her friends and the people she knew in their village, but then she remembered the cold dragging misery of Ruby’s funeral, the cross bearing her and Noah’s names, the mound of earth covered in irises, her sister’s favourite flower, and she knew she never wanted to go back there again.

Stella never said how she found the commune in Nunhead and Vivienne didn’t ask, it was just another surprising turn in this constantly twisting new life of theirs. It was 1985, Nunhead a grubby pocket of south-east London tucked between New Cross and Peckham. The occasional small and dusty pub filled with small and dusty old men; clusters of council estates, Afro-Caribbean barber shops that stayed open half the night, lights and music and laughter spilling out across the pavement, narrow streets of dirty-bricked terraces, punctuated here and there by a greasy spoon, a bookies, a launderette. It was as far away from their rural Essex lives as Mexico or the moon.

Unity House had been on the border of New Cross, along a wide street lined with tall Victorian houses with steep steps to the door, from where you could look down at the barred windows of the cool dark basement area far below. Viv and her mother had arrived there one rainy Tuesday afternoon. They’d stood staring up at its yellow front door, they and their bags growing steadily damper in the drizzle.

Suddenly the door had opened and a young, pretty woman with a mass of black curls tied back with a red bandana and huge silver hoops in her ears had said, ‘Hello! You must be the new recruits. I’m Jo. Looks like you could do with a cuppa.’ And Viv had looked into Jo’s smiling face and something tightly bound inside her had unloosened a fraction for the first time since they’d left Essex and she’d thought, Thank you, oh thank you, thank you.

Unity House had been the start of it all, the start of their new life, of Stella’s transformation, though they hadn’t known that then. Jo had led them to an enormous kitchen with lime green walls and a long table covered in books and mugs and gardening gloves, a tomato plant someone was in the middle of repotting. Off the kitchen was a brick outhouse, and spying a wooden hutch, Vivienne had let go of her mother’s hand and dropped to her knees to find the biggest rabbit she’d ever seen.

When she returned she’d stared up wide-eyed at the posters pinned to the kitchen walls. One, bizarrely, was of a fish riding a bicycle, another was about something called Greenham Peace Camp. After a while she’d tuned into her mum and Jo’s conversation and was shocked to hear Stella haltingly tell her about Ruby. Viv had held her breath; her mother never talked about these things, not ever, not even to her. But Jo had leaned forward and put her hand on Stella’s arm, her eyes shining with compassion. ‘You’ve come to the right place,’ she said. ‘We’re all survivors here, one way or another.’

When they’d finished their tea, Jo had shown them around their new home, which they soon saw was much bigger than it had appeared from the street: four floors of large, light and airy rooms, linked by narrow passageways and three steep flights of stairs. In the living room one wall was entirely covered by a mural of a naked woman, a white dove in each hand. Everywhere she looked were piles of books, an abundance of pot plants, large, dramatic abstract oil paintings in vivid primary colours, a broken guitar here, somebody’s bike there. Indian throws were pinned across the large bay windows, turning the room’s light a pale mauve, orange, green. Viv can still recall the house’s singular woody, musty smell, feel the fresh air blowing through the always-open garden door.

One by one they were introduced to the others. There was Sandra and Christine, who, strangely, had a son together, a round-faced two-year-old named Rafferty Wolf who called one of them Mummy and the other Mama; they lived on the first floor. Soren, a slender, bright-eyed woman in her sixties, wore her grey hair in a long plait to her waist and was clearly responsible for the artwork displayed throughout the house; her attic space was lined with dozens of canvases, a smell of turps in the air.

On the second floor lived Hayley. A student in her twenties, she had purple spiky hair, a nose ring and a wide smile that showed large and gappy teeth. Her room was thick with cigarette smoke and through its fug Viv saw that her walls were covered in posters and flyers with slogans like ‘Maggie Out!’ and ‘Ban the Bomb!’ and ‘Fuck Capitalism!’ Across the hall was Jo’s room. In the basement lived Kay, who had a man’s haircut, shy brown eyes, wore a man’s suit, and barely spoke. ‘You’ll meet Margo later,’ Jo had promised as she showed them to the room that would be theirs.

That evening a dinner was thrown in their honour. The long table now cleared of gardening things, the nine of them crowded around it, everyone – apart from Viv, her mother and Kay – talking at once while Jo ladled something called goulash onto their plates. Vivienne sat close to her mother, overwhelmed by the hubbub of voices, the good-natured jostling for space, and she’d watched wide-eyed as Sandra, mid conversation, lifted her top to reveal her bare breast for Rafferty Wolf to feed hungrily from.

And then Margo had entered the room. Though in her fifties, her black skin was still luminous, her long dreadlocks only lightly peppered with grey. She was, Viv thought, absolutely beautiful. Her movements slow and languorous, she wore a long billowy blue dress with mustard embroidery at the bodice. She took her seat at the head of the table and while Jo poured her a drink, she had turned her large dark eyes to Viv and her mother. ‘Welcome, Vivienne and Stella, I’m so pleased to have you here,’ she’d said.

Candles flickered and spilled red wax down the necks of wine bottles, their flames casting shadows of the women against the lime green walls. Margo told them how she’d started the commune ‘as a place of shelter, somewhere we can live without violence or fear or censure. Everyone is equal here. We all contribute, we pool our resources, our time and our skills …’ She had a slow, sonorous way of talking that was almost hypnotic. Somebody put some music on, a female voice rising and falling along with a flute and a guitar. Vivienne, sleepy now, leaned her head against her mother’s shoulder as she listened to Margo talk.

One by one, the women had told their stories that night, describing how they’d come to find each other, how Margo and Unity House had changed their lives. Viv must have fallen asleep, because the next thing she knew she was being carried up to bed, a blanket pulled over her, her ears full of the music and the rise and fall of the women’s voices.

They would stay at Unity House for almost a decade, and during that time the strong, clever, loving women who lived there would each, in their own way, help to shape the person Vivienne would become. But, just as that first night it was Margo who’d made the greatest impression upon eight-year-old Viv, it would also prove to be Margo who taught her the most valuable lesson of all – that people aren’t necessarily always who they seem.

5 (#ulink_55b361b3-7fbc-5ae6-945b-b7b4fb570c7e)

When Viv wakes the next morning to the sound of Cleo showering down the hall, she lies in bed staring at the ceiling for a while, thinking about Ruby and the black hole of memories she’d fallen into the night before. The little white Essex cottage, their sudden escape to London, the decade spent at Unity House. She looks at her alarm clock and, remembering it’s Saturday and that Cleo has a football match she needs driving to, groans and pulls herself from the bed. She drank too much again last night. After Cleo had gone to bed she had thought about Monday’s anniversary and one glass of wine had turned into another and then another, as they so often do. Wrapping a dressing gown around herself, she stumbles downstairs to the kitchen where she finds the empty wine bottle and shoves it guiltily in the recycling box with the others.

As she makes herself coffee she gives herself a mental shake. Ruby’s death was so long ago; they had survived it, both she and Stella. Jack Delaney had been found guilty and sent to prison, and that was that. It was all in the past.

She’d been in her thirties when he’d finally been released, thanks to an extra eight years added to his sentence for an attack on a fellow prisoner so vicious it had left his victim in a coma, permanently blinded in one eye. On Jack’s release, Viv had avoided all news stories about him, even taking Cleo, ten by then, on holiday to France in case the papers decided to print his picture. She had only vague memories of what he looked like: dark hair, a thin, cruel mouth and heavy brow, but nothing substantial; his image had been banished to the part of her brain where her darkest terrors lived and the shadowy figure who stalked her nightmares was frightening enough without furnishing it with the details a photograph would provide. Her mother later heard he’d emigrated to Canada, and though that should have given Viv comfort, it hadn’t, not really: as long as he was alive she would fear him.

She carries her coffee across to the table and sits down. A pale morning sun casts its glow across the parquet flooring and the kitchen has a gratifyingly warm and cosy feel. This morning, she thinks with satisfaction, her house looks exactly like the tasteful, comfortable, middle-class home she’d spent the past fifteen years and an awful lot of money trying to create. In fact, every room of her pretty Georgian townhouse is a testament to the hours spent lovingly restoring each period detail, or trawling auctions and eBay for the perfect antique lampshade or table or chair. A million miles from the little white cottage, the large and chaotic commune – the sort of home where nothing bad ever happened and never would. A perfectly nice, perfectly safe place in which to raise her daughter.

She hears Cleo come clattering down the stairs seconds before she bursts into the room, stuffing her football kit into her bag. Her curls still wet from the shower, she takes one look at her mother and wails, ‘Oh Mum! You’re not even dressed! You’re supposed to be taking me to footie!’

Guiltily Viv jumps to her feet. ‘OK, OK! I’ll be ready in two minutes. Jeez, relax!’ She gulps her coffee and hurries from the room.

Five minutes later as they are leaving the house, Cleo impatiently rushing ahead, Viv spies their new neighbour, Neil, cutting his hedge. Not having the heart to ignore his eager smile, she gives him a wave, ‘Hello there!’ He’s a slightly chubby man who looks to be in his late forties with badly dyed brown hair and a rather grating laugh, but he’s harmless enough; a welcome antidote at least to the self-satisfied hipsters who’d descended on the area in droves in recent years.

Ignoring Cleo, who’s scowling and rolling her eyes, she says, ‘You’re up and at ’em early, Neil. How’s it all going with the renovations?’

‘Oh, slowly, slowly, you know how it is.’

‘You’ve done wonders with the place.’ She glances up at the sash windows he’s recently installed. It is, in fact, quite astonishing what he’s managed to do in such short a time. Before he’d moved in, the property had belonged to a sweet elderly Cypriot woman who, due to ill health, had allowed the house to fall to rack and ruin over the fifty years she’d lived there. By the time she’d died it had been almost derelict. Shortly after the funeral her daughter had put it on the market for a price Viv had thought extortionate, considering the work that needed doing to it, and it had languished on the market for over eighteen months before suddenly it had sold, to the entire street’s surprise, for the full asking price. A few months later, Neil had moved in.

He’s looking at her hopefully. ‘You and Cleo will have to come round for a cup of tea sometime. I can show you what I’ve done inside.’

‘We’d love to,’ she says, beginning to edge away. ‘That’d be great.’ She smiles apologetically, ‘I’m afraid we’ve got to run now, footie practice, but let’s definitely do that soon, thank you.’

She feels him watching her as they get into the car. Oh, God, does he fancy her? She doesn’t really get that vibe, though she’s not quite sure what vibe she does get, exactly. Perhaps he’s just a bit lonely: she never sees any friends dropping by, no one who looks like family for that matter either. She finds herself hoping very much that he doesn’t fancy her; there’s something about his high-pitched giggle, his eager-puppy eyes that creeps her out a little. Immediately she feels a twinge of self-reproof: You’re not exactly beating them off with a stick yourself, Viv. And then she thinks of Shaun and cringes.

There’s a short warm-up before the match starts so Viv decides to wait in the car. The icy rain that had begun to fall on the journey over there begins to pick up pace and she turns up the heater, savouring these last moments of warmth and dryness before she’s forced out into the freezing cold to watch her rosy-cheeked daughter run around the sodden sports field, happy as a pig in mud. Cleo certainly hadn’t inherited her love of sport from her.

She changes the CD she’d been listening to and idly thinks about what to cook for Samar and Ted later when they come over for lunch – something she’d organized to distract herself from the looming anniversary of Ruby’s death. Before long her thoughts turn to the café and the refurb she’s planning, and she feels a pleasurable tug of excitement.

She sometimes has to pinch herself when she considers how well her life has turned out. A beautiful daughter, her own house and business. For a terrifying time, it had seemed likely that she might not make it through her twenties alive – in fact, if it hadn’t been for Stella and Samar, she doubts she would have done.

In 1991, when she was fourteen, she had received completely out of the blue, a letter telling her that both her maternal grandparents had died and left all their money to her. An astonishing sum of £500,000, to be held in trust until her eighteenth birthday. Half a million pounds! She had called for her mother, remembering the journey they’d made to her grandparents’ beautiful home, senseless with grief and shock, in the aftermath of Ruby’s murder. How her mother had told her, ‘There’s nothing for us here.’

Stella had read the letter in silence. ‘Well,’ she said neutrally, when she’d finished. ‘Looks like you’re going to be rich.’

‘But why didn’t they leave it to you?’ Viv had asked incredulously. ‘They didn’t even know me!’

Stella dropped the letter to the table and said, ‘I don’t want their bloody money.’

In the silence that followed they heard Margo walking to and fro in her bedroom above and Vivienne saw her mother’s whole bearing tense at the sound. ‘What happened between you and your parents?’ she asked her tentatively. ‘Why did they treat you so badly?’ It was a question she’d tried to ask her mother many times over the years, but had never received a satisfactory answer.

But to her surprise Stella said, ‘I didn’t do what they wanted – university, a career, a good marriage. I was so young when I fell pregnant with Ruby. I let them down. They couldn’t forgive me.’

‘And they punished you forever after?’ Viv said hotly. ‘Well, they were bloody bastards, then! I don’t want their money either!’

‘Take it.’

‘No way. Or if I do, we’ll share it.’

And though it had taken her a long time, eventually Stella had been persuaded, and at eighteen, Viv had found herself in the astonishing and very dangerous position of having more money than she knew what to do with. Now, as she waits for Cleo’s football match to start, she pushes the memory away. What had followed had been one of the darkest times of her life and wasn’t something she liked to dwell on.

After the muddy, wet and interminable football match, Viv and Cleo return home, Viv to make a start on lunch, Cleo to get straight on the phone to invite her friend Layla over. ‘To help me with my English essay,’ she explains, somewhat unconvincingly.

Viv’s peeling potatoes when Layla arrives. She pops her head around the door on her way up to Cleo’s room and Vivienne waves hello. ‘How’s it going, sweetheart? Nice to see you.’ Layla and Cleo have been friends since nursery school. She’s a slight girl, with neat tight cornrows, lavender-framed glasses and a terrifyingly high IQ. Layla holds strong views on everything from fracking to the Gaza Strip and isn’t afraid to air them. Though her parents – a jolly, extrovert couple from Mozambique – run a dry-cleaner’s and her older sister Blessing is training to be a beautician, Layla intends to be a human rights lawyer when she grows up, and Viv has absolutely no doubt whatsoever that this will happen one day.

‘Samar and Ted are coming over soon,’ she tells her. ‘Do you want to join us for lunch?’

Layla narrows her eyes. ‘Will it be vegan-friendly, Vivienne?’

‘Erm, no. No, I’m afraid it probably won’t.’

Layla looks at her severely through her glasses. ‘In that case, no thank you. I’ve been reading about the effects of meat consumption on the environment and frankly want no part of it.’

Viv smiles, and notices that Layla is carrying a small duffle bag. ‘What’ve you got in there?’

But before she can reply, Cleo appears and pulls her friend by the arm. ‘Come on, let’s go to my room.’

A moment later Viv hears Cleo’s door close and the stereo being switched on, and she relaxes, relieved that Cleo seems to have bounced back after the disappointing visit to her father’s a few weeks before. Mike had recently had a new baby with his girlfriend Sonia, and Cleo’s last visit had been her first introduction to her half-brother. She’d been quiet when she returned, and evasive to Viv’s gentle questioning. She absolutely doted on her dad, despite the myriad ways he’d let her down. Viv sighs and gets the chicken out of the fridge ready for roasting, shuddering when she remembers that had also been the weekend she’d slept with Shaun. Should have been grateful, saggy old bitch. Jesus. She shakes her head: she certainly knew how to pick them.

Upstairs, Layla is watching Cleo rummage through her duffle bag. ‘What do you want all this stuff for anyway?’ she asks her. ‘My sister will go crazy if she finds out I’ve taken it.’

Cleo pulls out a handful of cosmetics and looks at them in wonder. ‘I want you to take a picture of me, I’m sick of looking the way I always look. I’ve been watching YouTube videos on how to put this stuff on.’

Layla frowns. ‘But what’s the picture for?’

‘Just … OK, promise not to freak? I’ve been talking to this boy online, on the Fortnite forum, you know? His name’s Daniel and he sent me a picture of himself and he’s amazing. Now he wants one of me. And I don’t want to look like some stupid kid. I want to look cool.’

Layla’s unimpressed. ‘I think this is a very bad idea, Cleo. It’s highly likely that this Daniel person is what’s known as a catfish. They made us watch that documentary about it at school, remember?’

But Cleo only shrugs. Yes, he could be a fake, but she doesn’t think so, and in a way, it doesn’t really matter. It’s like a game she’s caught up in. She’s never going to meet him, so what’s the harm in it? It’s almost like getting lost in a film or a book, a fun, easy way to talk to a cute boy without the embarrassment of having to do it face-to-face. And she’s found she wants to be different, suddenly, from the same old Cleo who plays football and gets good grades and looks much younger than everyone else in her year. She’d heard a few boys at school talking about her as she walked past them a week or so ago, sniggering, saying she looked like a boy and had no breasts, that they wouldn’t touch her with a bargepole. And even though she knew deep down they were idiots, it had triggered something inside her, a restless anxiety that she was being left behind. She wished she could be more like Layla and not care, but the truth was she did. ‘I just want to try it,’ she says to her friend. ‘Will you help?’

Sighing, Layla picks up a tube of mascara and a lipstick, and shrugs her agreement, surprising both of them over the next twenty minutes by being a dab hand with it. ‘No idea why Blessing needs to go to college to learn how to do this stuff,’ she mutters, running some straightening irons through Cleo’s hair. ‘It’s not exactly rocket science.’

Cleo smiles and listens to the sounds of her mother preparing lunch downstairs. She thinks about how over the past few days her mum’s face has taken on a familiar, distracted look. Every year at this time it’s the same: the sadness of an awful, unimaginable thing that had happened a lifetime ago to someone she had never known sweeps through their house, pressing itself against the window panes, drifting up between floorboards, dimming the lights and chilling the air. And this year, like all the ones before it, she’d had no idea what to say to make her mum feel better.

‘Do this,’ Layla instructs her, pushing her lips into a pout as she brandishes a shade of lipstick called Hubba Hubba!

As Cleo obeys, her thoughts turn to her recent visit to her dad’s house, how much she’d been looking forward to meeting her new brother, how when she’d arrived it had been nothing like she’d thought it would be.

Her dad and Sonia seemed to exist in an exhausting cycle of nappies and feeding and sleepless nights, beset with anxieties about sniffles and temperatures and something called colic, something called croup. The baby had been clamped to Sonia’s breast for what seemed like hours on end and Cleo had felt in the way, an inconvenience. When she talked, her voice was too loud, her movements too clumsy. When she’d finally been allowed to hold Max, he had screamed so hard that Sonia had taken him back with a sigh of exasperation and she’d started to cry herself, only for her dad to say, ‘For goodness’ sake, Cleo, don’t you start; you’re a big girl now, grow up!’

And despite his exhaustion, she’d seen how her dad gazed down at his new son, felt the love that bound the three of them so tightly, and something inside her had hurt, as though the more warmth there was in their little house, the colder she felt inside, and she’d wanted to go home to London, feeling guiltily relieved when her dad drove her to the station and tiredly waved her off.

‘Right,’ says Layla briskly. ‘All finished.’ Eagerly Cleo goes to look at herself in the mirror and grins in amazement. Her hair is sleek and sophisticated rather than its usual mess of curls; the eyeliner, mascara and lipstick Layla’s used has definitely made her look prettier as well as older – at least fifteen, she thinks. She runs to her mother’s room and returns wearing a red, scoop-necked T-shirt, then again gazes at her reflection in the mirror, delighted with herself. ‘OK, now take a picture of me,’ she says excitedly.

Later, when Layla has left, Cleo sends the picture straight to Daniel. His response is almost instant – Wow, you’re so beautiful! – and happiness fizzes inside her. Then she hears her mum calling from downstairs. ‘Cleo? Sammy and Ted are here. Come down!’

G2g xx, she writes, then runs to the bathroom and scrubs the make-up from her face, before returning the T-shirt to her mother’s closet and heading for the stairs.

In the kitchen, Samar is telling Vivienne and Ted a story about a well-known theatre actress he’d once worked with. A long career in stage management has provided him with a seemingly endless supply of salacious gossip, but even by his standards, today’s tale is pretty hair-raising. ‘But I mean, how is that even possible?’ Viv muses when he’s finished. ‘And with a Great Dane, for Christ’s sake?’ She sighs wonderingly and pours Samar a glass of wine, then offers the bottle to Ted. ‘How about you, Ted? You joining us today?’

‘Oh, better not, I’m on a diet.’ He pats his round stomach regretfully.

When Viv turns back to Samar she’s surprised to see the wistfulness in her friend’s eyes as he gazes over at Ted. It occurs to her suddenly that they’d both been quieter than usual today and she wonders if they’ve had a row. Samar has always been uncharacteristically unforthcoming about their relationship. When he’d first introduced him to her she’d been dubious; Ted hadn’t seemed the most obvious match for her friend. While Samar was skinny as a whippet, habitually dressed in black and had a sense of humour verging on depraved, Ted had a lilting Welsh accent, was balding and overweight, and favoured comfortable clothes in various shades of beige. He’d always struck her as a bit staid for someone as extrovert as Samar.

She also couldn’t help feeling that Ted didn’t entirely approve of her and Samar’s close friendship. He often avoided joining them whenever they got together, sending Samar with an apologetic excuse that never quite felt authentic. When he did appear she sometimes had the nagging sense that he was there under sufferance and couldn’t help wonder if he might not like her very much. She takes a sip of her wine and tries to push the thought away. Samar is clearly head over heels, things have moved fast between them and on the whole they both seem happy together. The slight atmosphere today is probably down to a lover’s tiff, she decides, as she catches Samar’s eye and smiles. She gets to her feet and, sliding the chicken from the oven, bastes it with sizzling fat before slamming it back in. ‘So, tell me about this trip to Paris,’ she says to Ted. ‘Can’t believe you’re whisking him off again.’

‘What can I say? I like to spoil him.’

‘God, you lucky sod,’ she says to Samar enviously.

Ted shakes his head. ‘I’m the lucky one.’ At this she sees Samar beam with pleasure, whatever tension there’d been between them apparently forgotten.

Samar and Viv had met aged fourteen when he joined Deptford Green Comprehensive in Year 9. Both of them had been easy targets for the school’s bullies – Vivienne for wearing handmade clothes courtesy of Soren, having her hair cut by Hayley with the kitchen scissors, and for living in a house with ‘a bunch of weirdo lezzers’ that ‘didn’t even have a telly’, and Samar for being Pakistani, gay and seemingly unapologetic about both. Together they’d bunk off to hang out in Nunhead cemetery where they’d sit within its vast, overgrown sprawl amidst the broken angels and mausoleums, smoking spliffs pilfered from Hayley’s stash and pouring over copies of The Face and i-D, dreaming about what better, cooler, well-dressed people they’d be when they grew up.

Samar never said much about his home life but it hadn’t taken Viv long to get the gist – three sisters and an unhappy mother in a two bedroom flat in New Cross, a father who was perpetually drunk and full of a nameless rage that he liked to take out on his skinny, rebellious son. Samar had loved the commune, loved Stella with a fervour close to hero worship. He’d become one of her original devotees, first in the long line of waifs and strays she’d counsel over the years, and even now remained one of her most ardent fans.

Aged seventeen, in the mid-nineties, they’d discovered London’s gay scene, embracing every bar and club the city had to offer, returning faithfully every Saturday night to be transported to a world where neither Ruby’s death nor Samar’s dad could follow them.

When, after barely scraping through her A-levels, Vivienne inherited her grandparents’ money, life had been wonderful at first. Viv found them a flat to rent in Deptford and she and Samar partied by night and slept by day, their lives an exciting whirl of recreational drugs, booze and men. But then, suddenly, things had changed. Samar landed his dream job as a stagehand in the West End, and didn’t want to go out quite so much any more. He began to nag Viv about the drugs and drink she was consuming, the strange men waking up in their flat every weekend. In turn, she thought he was a boring, nagging hypocrite who needed to lighten up. Eventually, they’d had a major falling out. Samar had moved out of the flat and Viv had carried on partying without him.

And then, entirely out of the blue, or so it had seemed at the time, Vivienne, now twenty-two, had fallen into a darkness so thick and bottomless that she could find no way of dragging herself out. For weeks she’d stayed at home, sinking lower and lower, a sadness pressing on her chest that made her unable to eat or wash or countenance the world outside her flat. When she slept her dreams were plagued by horrors from which she’d wake breathless with fear, tears in her eyes, her sister’s name on her lips.

Finally, wanting to build bridges and concerned when she didn’t answer her phone, Samar had called around, using his old key to gain entry when there was no response to his knock. Within minutes he’d bundled Viv into a cab and taken her straight to Stella’s, and over the next year the two of them slowly helped put Vivienne back together. When Viv thinks back to that time she shudders to think what would have happened if Samar hadn’t rescued her, if her mum hadn’t been there to take charge.

It was a time in her life she never wanted to return to, especially since having Cleo. Sometimes though she feels the darkness like a black beast circling her, waiting for its chance to pounce. Only her need for alcohol remains from those dark days and nights of sex and booze and drugs; wine was the one thing she’d not managed to relinquish, not while her nightmares continued to haunt her.

The chicken out of the oven, Viv is about to call Cleo down to eat when Samar says quietly, ‘It’s the anniversary on Monday, isn’t it?’

She nods, touched that he remembers every year.

‘How’re you feeling?’

‘Oh, you know. I’ve no idea why I still get so upset every time. Why I can’t just move on. She died thirty-two years ago, for God’s sake.’

‘Have you never had therapy for it?’ Ted asks.

She glances at him. ‘No, but I’ve always had my mum to talk to, and you know how brilliant she is.’ Even as Viv makes this remark it occurs to her that Ted, in fact, hasn’t met Stella yet. Before he came on the scene she, Stella and Cleo would enjoy frequent Sunday lunches around at Samar’s flat, but that hadn’t happened in months. Again the worrying thought occurs to her that Ted, though perfectly polite to her face, might not quite approve of her and Samar’s closeness and she feels a lingering disquiet that the friendship that had survived since their schooldays might not endure if he tried to come between them.

But Ted merely nods. ‘Even so, maybe someone totally neutral wouldn’t be a bad idea.’

‘Oh, don’t bother,’ Samar tells him. ‘She won’t go. I’ve tried to talk her into it a billion times.’

Viv smiles and shrugs. The thought of talking to a stranger about her sister’s death has always made her feel intensely uncomfortable, though she’s not sure why. She’d been grateful that her mother had never insisted on it when she was young.

‘You sure you’re OK, though?’ Samar asks again, coming over and putting his arm around her.

She leans her head on his shoulder. ‘I hate this time of year.’

‘What you need is a bit of excitement in your life. How about that doctor guy from the café? Are you going to ask him out?’

She laughs. ‘No, Samar, I’m bloody not. For one thing, I don’t even know if he’s single.’

‘Well, get yourself on a few dating websites, then. It worked for me and Ted.’

‘Yeah,’ she says, ‘maybe you’re right.’ But her thoughts linger on the doctor, and she’s not sure what it is about him that intrigues her so, only that there’s something about his grave smile, the calm brown of his eyes that she can’t quite let go of.

Much later, after her guests have left and Cleo is sound asleep, Viv goes about turning off the lights and locking the front door. Outside, the November wind bounds and batters along the street, she hears a bottle rolling to and fro along the pavement, a dog’s distant bark. Before she goes to bed she glances in at Cleo sleeping before softly creeping away.

No matter how hard she tries not to think about it, her mind returns again and again to the day her sister died, a familiar niggling doubt worrying at the peripheries of her consciousness. This strange uncertainty is something that has dogged her all her life. Perhaps it was Jack’s continued assertion of his innocence – he had appealed three times against his conviction – or his family’s unwavering belief that she had lied, but she’s never quite been able to shake it off.

As she gets undressed she reminds herself of how badly Jack had treated Ruby, how both Morris Dryden and their neighbour Declan had said they’d seen him in their lane at the time of the murder. She reaches for her sleeping pills, wanting only oblivion. The right man had gone to prison; there could be no mistake.

She wakes to darkness, her head slow and foggy from the pill, to feel fingers gripping her shoulder and she jerks away in alarm.

‘Mum, wake up! Wake up, Mum, it’s OK, it’s only me.’

Sitting up, Viv gazes around her in confusion. ‘Cleo? What’s the matter?’

‘You were shouting in your sleep again.’

‘Oh, God, love, I’m sorry.’ She leans over and switches on the bedside light to find her daughter crouching by her bed, blinking in the sudden brightness.

‘It’s OK. You were really screaming. Are you all right?’

‘I’m fine. I’m sorry, darling. I’m OK.’

Cleo straightens and yawns, her face swollen with sleep. ‘Sounded like a bad one this time.’

‘It was. Thanks for waking me, I’m so sorry I disturbed you. Go back to bed. I’m fine.’

When Cleo leaves, Viv waits for her heart to cease its frantic hammering. The nightmare had begun the way it always did. She’s a child again, sitting in the living room while Ruby and Jack argue in the room above. A slow dread creeps through her. She knows that her sister is about to die but she’s unable to move a muscle, to do anything at all to stop it. What happens next always varies; occasionally she’ll go to Ruby’s bedroom to see a dark faceless figure standing over her sister’s body, sometimes she’ll run from the house knowing that her sister’s killer is on her heels, his hand reaching out to grab her.

In tonight’s dream though, just as she’d heard her sister’s scream she’d looked up to find their old neighbour, Declan Fairbanks staring in at her through the living room window. For a moment she’d held his pale blue gaze before being hit by the overwhelming rush of fear that had caused her to scream out so loudly that she’d woken Cleo – and probably half the street too.

It was not the first time she’d dreamt of Declan; he often appeared in her nightmares, always with an accompanying feeling of disquiet. Sometimes she’ll dream that Morris Dryden is there too, his happy grin and rosy cheeks incongruous with her terror.

This, of course, is not surprising, tied as Morris and Declan are to that day, their witness statements playing a key role in Jack’s conviction. But she’s noticed lately that her unease when she dreams of Declan is laced with something else – a queasy kind of revulsion. She remembers little about him: a rather severe-looking man in his fifties, dark hair peppered with grey, very striking pale blue eyes. She has a dim recollection of him shouting at her once for kicking a ball at his window. Perhaps that’s where her aversion springs from, the childish memory of being chastised mixed with the general horror of Ruby’s death. Perhaps that was all it was.

For a long time she lies staring at the ceiling, only the street lamp below her window casting its weak glow upon the blackness. The wind has stopped; the world outside is silent now. But when at last she starts to drift off back to sleep, a sudden noise from the street jerks her back to full consciousness. What was that? Her window is open a crack and she lies very still, listening, until another sound from outside has her sitting up, suddenly alert. There it is again: feet shuffling on the pavement below, then the sound of someone clearing their throat. Her nostrils prickle as she detects the faint trace of cigarette smoke. Slipping from her bed she creeps to the window and looks out.

There is someone standing by her gate and she feels a jolt of shock when she realizes that it’s her mother’s boarder, Shaun. He’s looking away down the street, the red glow from his cigarette rising and falling as he takes a drag, and she quickly steps back from the street lamp’s glare. What on earth? She waits, heart pounding, until she hears him move off, his footsteps on the pavement gradually retreating, and when she dares to peer out once more she sees him rounding the furthest corner, before finally disappearing from view.

6 (#ulink_3f3307ef-e441-5db1-acec-461c47049bb4)