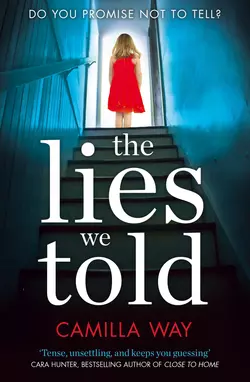

The Lies We Told: The exciting new psychological thriller from the bestselling author of Watching Edie

Camilla Way

DO YOU PROMISE NOT TO TELL?A DAUGHTERBeth has always known there was something strange about her daughter, Hannah. The lack of emotion, the disturbing behaviour, the apparent delight in hurting others… sometimes Beth is scared of her, and what she could be capable of.A SONLuke comes from the perfect family, with the perfect parents. But one day, he disappears without trace, and his girlfriend Clara is left desperate to discover what has happened to him.A LIFE BUILT ON LIESAs Clara digs into the past, she realizes that no family is truly perfect, and uncovers a link between Luke’s long-lost sister and a strange girl named Hannah. Now Luke’s life is in danger because of the lies once told and the secrets once kept. Can she find him before it’s too late?

Copyright (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Camilla Way 2018

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Stephen Carroll/Trevillion Images (https://www.trevillion.com/) (staircase), Jacinta Bernard/Trevillion Images (https://www.trevillion.com/) (girl)

Camilla Way asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008159092

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008159085

Version: 2018-12-12

Table of Contents

Cover (#u118687c4-b9f3-5634-94a6-8e33d183b1f5)

Title Page (#u64fc2d48-d6e5-504a-ad6d-ea14fb44d961)

Copyright (#u63c53bd1-f815-579e-9b11-6771dc56aded)

Dedication (#ud0464326-f295-55dc-b67d-7fb08d8df01f)

Chapter 1 (#u4fe4e8d3-5378-5f5c-9b31-a3e56bf85dcd)

Chapter 2 (#u74154aed-4161-5c01-934a-dbf4f25f072a)

Chapter 3 (#u328297cd-4502-5450-8d78-08f14d3f308a)

Chapter 4 (#u63bcf495-7d56-51d8-8b32-7020dc6c49a7)

Chapter 5 (#u02150cbd-dbcc-5cf6-b656-7b7ffdb52b29)

Chapter 6 (#ubf2acac3-fcee-5ec5-84da-9556c1638274)

Chapter 7 (#u4e1f1540-e532-5898-9b18-f349c19918c2)

Chapter 8 (#u747ccbe8-c0cc-5200-96f5-ab2d74681663)

Chapter 9 (#udb482c7a-8231-5509-ab94-d9acdff35977)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading… (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Camilla Way (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Dedication (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

For Albert and Sidney

1 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

Cambridgeshire, 1986

At first I mistook the severed head for something else. It wasn’t until I was very close that I realized it was Lucy. To begin with I thought the splash of yellow against the white of my pillow was a discarded sock, a balled-up handkerchief perhaps. It was only when I drew nearer and saw the delicate crest of feathers, the tiny, silent beak, that I fully understood. And suddenly I understood so much more: everything in that moment became absolutely clear.

‘Hannah?’ I whispered. A floorboard creaked in the hall beyond my bedroom door. My scalp tightened. ‘Hannah,’ louder now, yet with the same, fearful tremor in my voice, ‘is that you?’ No answer, but I felt her there, somewhere near; could feel her waiting, listening.

I didn’t want to touch my little bird’s head, could hardly bear to look at the thin, brown line of congealed blood where it had been sliced clean from the body, the half-open, staring eyes. I wondered if she’d been alive or dead when it happened, and started to feel sick.

When I went to Hannah’s bedroom she was standing by her window, looking down at the garden below. I said her name and she turned and regarded me, her beautiful dark eyes sombre, just a trace of a smile on her lips. ‘Yes, Mummy?’ she said. ‘What’s wrong?’

2 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

London, 2017

Clara woke to the sound of rain, to a distant siren wailing somewhere along Old Street, and the low, steady thump of bass from her neighbour’s speakers. She knew instantly that Luke wasn’t home – not just absent from their bed but from the flat itself – and for a moment she lay staring into the darkness before reaching for her phone: 04:12. No missed calls, no text messages. Through the gaps of her curtains she could see the falling rain caught in a streetlamp’s orange glare. Below her window on Hoxton Square came the sudden sharp peal of female laughter, followed by the clattering stumble of high heels.

Another hour passed before she gave up on sleep. Beyond their bedroom door the first blue light had begun to seep into the flat’s dark corners, the furniture gradually taking shape around her, its colours and edges looming like ships out of the darkness. The square’s bars and clubs were silent now, the last stragglers long gone. Soon the sweep and trundle of the street cleaners’ truck would come to wash the night away, people would emerge from their buildings heading for buses and trains; the day would begin.

Above her, the repetitive beat continued to pound and, sitting on the sofa wrapped in her duvet now, she stared down at her phone, her tired mind flicking through various explanations. They hadn’t had a chance to speak yesterday at work, and she’d left without asking him his plans. Later, she’d met a friend for drinks before going to bed early, assuming he’d be back before too long. Should she call him now? She hesitated. They’d only moved in together six months before, and she didn’t want to be that girlfriend – nagging and needy, issuing demands and curfews – it was not the way things worked between them. He was out having fun. No big deal. It had happened before, after all – a few drinks that had turned into a few more, then sleeping it off on someone’s sofa.

Yet it was strange, wasn’t it? To not even text – to just not come home at all?

It wasn’t until she was in the shower that she remembered the importance of the day’s date. Wednesday the twenty-sixth. Luke’s interview. The realization made her stand stock-still, the shampoo bottle poised in mid-air. Today was the big interview for his promotion at work. He’d been preparing for it for weeks; there was no way he would stay out all night before something so important. Quickly she turned the water off and, wrapping herself in a towel, went back to the living room to find her phone. Clicking on his number she waited impatiently for the ringtone to kick in. And then she heard the buzzing vibration coming from beneath the sofa. Crouching down she saw it, lying on the dusty expanse of floor, forgotten and abandoned: Luke’s mobile. ‘Shit,’ she said out loud, and as though surprised, the pounding music above her head ended in abrupt silence.

She clicked open her emails and sure enough there it was, a message from Luke, sent last night at 18.23 from his work address.

Hey darling, left my phone at home again. I’m going to stay and work on stuff for the interview, probably be here til eight, then coming home – want to have an early night for tomorrow. You’re out with Zoe, aren’t you? See you when I do, Lx

An hour later, as she made her way up Old Street, she told herself to get a grip. He’d changed his mind, that was all. Decided to go for a pint with his team, then ended up carrying the night on. He couldn’t let her know because he was phoneless – nothing else to it. She would see him soon enough at work, hung-over and sheepish, full of apologies. So why was her stomach twisting and turning like this? Beneath the April sky, grey and damp like old chewing gum, she walked the ugly thoroughfare, already gnarled with traffic, the brutal hulking buildings of the roundabout ahead, the wide pavements filled with commuters pressing on and on, clutching coffee, earbuds in, staring down at phones or else inward-looking, unseeing, as they moved as one towards the white tiled station entrance, to be sucked in then hurtled forward, and spat out again the other end.

The magazine publishers where they both worked was in the centre of Soho. Though they were on separate magazines – she a writer on a finance title, he heading the design desk of an architectural quarterly – it’s where they’d met three years ago, shortly before they’d started going out.

It had been her first day at Brindle Press and, eager to make a good impression, she’d offered to make the first round of teas. Anxiously running through everyone’s names as she’d sloshed water on to teabags and stirred in milk and sugar, she’d piled too many mugs on the tray before she’d hurried out of the kitchen. The mess when it slipped from her hands and came crashing to the floor had been spectacular; scattered shards of broken crockery, rivers of brown steaming liquid, her carefully chosen ‘first-day’ dress soaked through.

Fuck. Fuck fuck fuck. It was only then that she’d looked up and seen him, the tall, good-looking man standing in the doorway, watching her with amusement. ‘Oops,’ he’d said, crouching down to help her.

‘Christ, I’m an idiot,’ she’d wailed.

He’d laughed. ‘Don’t worry about it,’ he said, then added, ‘I’m Luke.’

That evening, when her new team had taken her out for welcome drinks she’d spotted him at the bar, her heart quickening as she met his gaze, his dark eyes holding her there, as though he’d reached out his hand and touched her.

Now, as she approached her desk the phone rang, its tone signalling an internal line and she snatched it up eagerly. ‘Luke?’

But it was his deputy, Lauren. ‘Clara? Where the fuck is he?’

She felt herself flush. ‘I don’t know.’

There was a short, surprised silence. ‘Right. What, you don’t … you haven’t seen him this morning?’

‘He didn’t come home last night,’ she admitted.

There was another silence while Lauren digested this. ‘Huh.’ And then she heard her say loudly to whoever was listening nearby, ‘He didn’t come home last night!’ A chorus of male laughter, of leering comments she couldn’t quite catch, though the tone was clear: Naughty Luke. They were joking, she knew, and their laughter was comforting, in a way, signifying their lack of concern. Still, she clutched the receiver tightly until Lauren came back on the line. ‘Well, not to worry. Fucker’s probably dead in a ditch somewhere,’ she said cheerfully. ‘When you do speak to him, tell him Charlie’s raging, he’s missed the cover meeting now. Later, yeah?’ And then she hung up.

Maybe she should go through his contacts list, ring around his friends. But what if he did arrive soon? He’d be mortified she’d made such a fuss. And surely he was bound to turn up sooner or later – people always did, after all.

Suddenly his best friend Joe McKenzie’s face flashed into Clara’s mind and for the first time her spirits lifted. Mac. He’d know what to do. She grabbed her mobile and hurried out into the corridor to call him, feeling immediately comforted when she heard his familiar Glaswegian accent.

‘Clara? How’s it going?’

She pictured Mac’s pale, serious face, the small brown eyes that peered distractedly from beneath a mop of black hair.

‘Have you seen Luke?’ she asked.

‘Hang on.’ The White Stripes blared in the background while she waited impatiently, imagining him fighting his way through the chaos of his photographic studio before the noise was abruptly killed and Mac came back on the line. ‘Luke? No. Why? What’s— haven’t you?’

Quickly she explained, her words spilling out in a rush: Luke’s forgotten mobile, his email, his missed interview. ‘Yeah,’ Mac said when she’d finished. ‘That’s odd, right enough. He’d never miss that interview.’ He thought for a moment. ‘I’ll call around everyone. Ask if they’ve seen him. He’s probably been on a bender and overslept, you know what he’s like.’

But his text half an hour later said, No one’s heard from him. I’ll keep trying though, I’m sure he’ll turn up.

She couldn’t shake the feeling something was very wrong. Despite his colleagues’ laughter, she didn’t really think he’d been with another woman. Even if he had, a one-night stand didn’t take this long, surely? She made herself face the real reason for her anxiety: Luke’s ‘stalker’.

Putting the word in inverted commas, treating it all as a bit of a joke, was something Luke had done ever since it had begun nearly a year ago. He’d even christened whomever it was ‘Barry’ – a comical, harmless name to prove just how unthreatened he was by it all. ‘Barry strikes again!’ he’d say, after yet another vicious Facebook message, or silent phone call, or unwelcome ‘gift’ through the post.

But then things had got weirder. First an envelope stuffed with photographs had been pushed through their door. Each one was of Luke and showed him doing the most mundane of things – queuing at a café, or walking to the Tube, or getting into their car. Whoever had taken them had clearly been following him closely – with a wide-angled lens, Mac had said. It had made Clara’s skin crawl. The photos had been stuffed through their letterbox with arrogant nonchalance, as if to say, This is what I can do: look how easy it is. But though she’d been desperate to call the police, Luke wouldn’t hear of it. It was as if he was determined to pretend it wasn’t happening, that it was merely an annoyance that would soon go away. And no matter how much she begged, he wouldn’t budge.

And then, three months ago, they’d come home late from a party to find the door to their flat forced open. Clara would never forget the creepy chill she’d felt as they silently walked around their home, knowing some stranger had recently been there – going through their things, touching their belongings. But the strange thing was, everything had been left in perfect order: nothing had been stolen; nothing, as far as she could tell, had been moved. Only a handwritten message on a page torn from Clara’s notepad was sitting on the kitchen table: I’ll be seeing you, Luke.

At least Luke had been sufficiently rattled to let Clara report that to the police. Who didn’t even turn up until the next day and discovered precisely nothing – the neighbours hadn’t seen anything, no fingerprints had been found – and as nothing had been taken or damaged, within days the so-called ‘investigation’ had quietly fizzled out.

Stranger still, after that, it was as if whoever it was had lost interest. For weeks now there’d been no new incidents, and Luke had been triumphant. ‘See?’ he’d said. ‘Told you they’d get bored eventually!’ But although Clara had tried hard to put it out of her mind, she hadn’t quite been able to forget the menace of that note – or the idea that the culprit was still out there somewhere, biding their time.

And now Luke had disappeared. What if ‘Barry’ had something to do with it? Even as she allowed the thought to form she could hear Luke’s laugh, see his eyes roll. ‘Jesus, Clara, will you stop being so dramatic?’ But as the morning progressed her sense of foreboding grew and when lunchtime came, instead of going to her usual café, she found herself walking back towards the Tube.

She reached Hoxton Square half an hour later, and when she caught sight of her squat, yellow-bricked building on its furthest corner, she was struck suddenly by the overwhelming certainty that Luke would be there waiting for her, and she ran the final few hundred yards, past the restaurants and bars, the black railings and shadowy lawn of the central garden and, out of breath by the time she reached the front door, she impatiently unlocked it before sprinting up the communal stairs to her flat. But when she got there, it was empty.

She sank into a chair, the flat too silent and still around her. On the coffee table in front of her was a photo she’d had framed when they’d first moved in together and she picked it up now. It was of the two of them on Hampstead Heath three summers before, heads squashed together as they grinned into the camera, a scorching day in June. That first summer, the days seemed to roll out before them hot and limitless, London theirs for the taking. She had fallen in love almost instantly, as effortlessly as breathing, certain she had never met anyone like him before, this handsome, exuberant man so full of energy and sweetness and easy charm and who, (inexplicably it seemed to her) appeared to find her just as irresistible. As she gazed down at the photo now, their happiness trapped and unreachable behind glass, she traced his face with her finger. ‘Where are you,’ she whispered, ‘where the bloody hell are you, Luke?’

At that moment she heard the front door slam two floors below and her heart lurched. She listened, her breath held as the footsteps on the stairs grew louder. When they paused outside her door she sprang to her feet and rushed to open it, but with a jolt of surprise found it was her upstairs neighbour, and not Luke, staring back at her.

She didn’t know the name of the woman who’d lived above them for the past six months. She could, Clara thought, be anything between mid-twenties and mid-thirties, it was impossible to tell. She was very thin with long, lank brown hair, behind which could occasionally be glimpsed a small, finely featured face covered in a thick, mask-like layer of make-up. In all the time Clara and Luke had lived there she’d never once replied to their greetings, merely shuffling past with downcast eyes whenever they met on the stairs. Every time either of them had gone up to ask her to turn her music down, which she played loudly night and day, she refused to answer the door, merely turning the volume up higher until they went away.

‘Can I help y—’ Clara began, but the woman had already begun heading towards the stairs. Clara was watching her go when her worry and stress got the better of her. ‘Excuse me!’ she blurted, and her neighbour froze, one foot poised on the first step, eyes averted. ‘It’s about the music. Could you give it a rest, do you think? It’s all night long, and sometimes most of the day too, can’t you turn it down once in a while?’

At first it seemed the woman wasn’t going to reply, but slowly she turned her face towards Clara. Her eyes, rimmed thickly in black kohl, landed on her own before flitting away again, as she asked softly and with the faintest ghost of a smile, ‘Where’s Luke, Clara?’

Clara could only stare back at her, too surprised to respond. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘Where’s Luke?’

She’d had no idea the woman even knew their names. Perhaps she’d seen them written on their post, but it was the way she said it – so familiar, so knowing, and with such a strange smile on her lips. ‘What do you mean?’ Clara asked but the woman only turned and carried on up the stairs. ‘Excuse me! Why are you asking about Luke?’ but there was still no reply. Clara stood staring after her. It was as if the world was conspiring in some surreal joke against her. The door to the upstairs flat opened and then closed again and at last Clara went back to her own flat. She stood in her narrow hallway, listening, until a few seconds later the familiar thud of bass began to thump against her ceiling once more.

It was past two. She should go back to work; her colleagues would be worried by now. But Clara didn’t move. Should she start phoning around hospitals? Perhaps she should google their numbers – at least that way she would be doing something. She went to the small box room they used as an office and at a touch of the mouse pad Luke’s laptop flickered into life, the browser opening immediately at Google Mail – and Luke’s personal email account.

For a second she stared at the screen, her finger hovering, knowing she shouldn’t pry. But then her gaze fell upon his list of folders. Below the usual ‘Inbox’ ‘Drafts’ and ‘Trash’ was one labelled, simply, ‘Bitch’. She stared at it in shock before clicking on it. And then her jaw dropped – there were at least five hundred messages, sent from several different accounts over the past year, sometimes as often as five times a day. She opened and read them one by one.

Did you see me today, Luke? I saw you. Keep your eyes peeled.

And,

I know you, Luke, I know what you are, what you’ve done. You might have most people fooled, but you don’t fool me. Men like you never fool me.

How are your parents, Luke? How are Oliver and Rose? Do they know the truth about you – your family, your friends, your colleagues? How about that little girlfriend of yours, or is she too stupid to see? She looks really fucking stupid, but she’ll find out soon enough.

And,

Women are nothing to you, are we, Luke? We’re just here for your convenience, to fuck, to step over, to use or to bully. We’re disposable. You think you’re untouchable, you think you’ve got away with it. Think again, Luke.

Then,

What will they say about you at your funeral, Luke? Say your goodbyes, it’s going to be soon.

The very last one had been sent only a few days before.

I’m coming for you, Luke, I’ll be seeing you.

It had been a woman, all this time? And he’d known about it for months, had known but hadn’t told her – had never even mentioned the emails. Did he know who it was? It was clearly someone who knew him very well – knew his parents’ names, where Luke worked; knew his movements intimately. Was it the same person who had broken into their flat, sent the photographs, the letters? Perhaps it was a joke, she thought wildly. An elaborate prank dreamt up by one of his friends. But then, where was he? Where was Luke? I’m coming for you, Luke. I’ll be seeing you.

She was deep in thought when the sound of her intercom sliced through the silence, making her jump violently, her heart shooting to her mouth.

3 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

Cambridgeshire, 1986

We waited such a long time for a baby. Years and years, actually. They couldn’t tell us why, the specialists. Couldn’t find a single reason why it didn’t happen for Doug and me. ‘Unexplained Infertility,’ was the best they could come up with. You think it’s going to be so simple, starting a family, and then when it’s taken from you, the future you’d imagined snatched away, it feels like a death. All I ever wanted was to be a mum. When school friends went off to university or found themselves jobs down in London, I knew it wasn’t for me. I didn’t want to be a career woman, didn’t need a big house and lots of money. I was content with our cottage in the village I’d grown up in, Doug’s building business; I just wanted children, and Doug felt exactly the same way.

I used to see them when they came back to our village for holidays, those old classmates of mine. And I’d see how they looked at me, with my clothes from the market and my lack of ambition, see the flash of superiority or bewilderment in their eyes when they realized I didn’t want to be just like them. But I didn’t care. I knew that what I wanted would bring me all the happiness I’d need.

Year by year, woman by woman, things began to change. They began to change. As we all neared our thirties, baby after baby began to make their appearance on those weekend visits. Of course, I’d been trying for a good few years by then, had already had many, many months of disappointment to swallow, but nothing hit me quite as hard as seeing that endless parade of children of the girls I used to go to school with.

Because I could see it, in their faces, how it changed them. How overnight the nice clothes and interesting careers and successful husbands which had once defined them became suddenly second place to what they now had. It wasn’t the change in them physically; the milk-stained clothes or the tired faces, it wasn’t the harassed air of responsibility or the being a member of a new club or even the obvious devotion they felt. It was something I saw in their eyes – a new awareness, I suppose – that most hurt me. It seemed to me as though they’d crossed into another dimension where life was fulfilling and meaningful on a level I could never understand. And the jealousy and despair I felt was devastating. Plenty of women, I knew, were happily childfree, leading perfectly satisfying lives without kids in them, but I wasn’t one of them. For as long as I could remember, having a family of my own was all I’d dreamt of.

So, when finally, finally, our miracle happened, it was the most amazing, most joyful thing imaginable. That moment when I held Hannah in my arms for the first time was one of pure elation. We loved her so much, Doug and I, right from the beginning. We had sacrificed so much, and waited such a long time for her, such a horribly long time.

I don’t remember exactly when the first niggling doubts began to stir. I couldn’t admit it to myself at first. I put it down to my tiredness; the shock and stress of new motherhood, or a hundred other different things rather than admit the truth. I didn’t let on to anyone how worried I was. How frightened. I told myself she was healthy and she was beautiful and she was ours, and that’s all that mattered.

And yet, I knew. Somehow I knew even then that there was something not quite right about my daughter. An instinct, of the purest truest kind, in the way animals sense trouble in their midst. Secretly I would compare her to other babies – at the clinic, or at Mother and Baby clubs, or at the supermarket. I would watch their expressions, their reactions, the ever-changing emotions in their little faces and then I’d look into Hannah’s beautiful big brown eyes and I’d see nothing there. Intelligence, yes – I never feared for her intellect – but rarely emotion. I never felt anything from her. Though I lavished love upon her it was as though it couldn’t reach her, slipping and sliding across the surface of her like water over oilskin.

At first, when I voiced my concerns to Doug, he’d cheerfully brush them aside. ‘She’s just chilled out, that’s all,’ he’d say, ‘let her be, love,’ and I’d allow myself to be reassured, telling myself he was right, that Hannah was fine and my fears were all in my head. But when she was almost three years old, something happened that even Doug couldn’t ignore.

I was preparing breakfast in the kitchen while she sat on the floor, playing with a makeshift drum kit of pots and pans and spoons I’d got out to entertain her with. She was hitting one pan repeatedly over and over, the sound ricocheting inside my skull, but just as I was mentally kicking myself for giving them to her the noise suddenly stopped. ‘Hannah want biscuit,’ she announced.

‘No, darling, not yet,’ I said, smiling at her. ‘I’m making porridge. Lovely porridge! Be ready in a tick!’

She got up, said louder, ‘Hannah want biscuit now!’

‘No, sweetheart,’ I said more firmly. ‘Breakfast first, just wait.’

I crouched down to rummage in a low drawer for a bowl, and didn’t hear her come up behind me. When I turned, I felt a sudden searing pain in my eye and reeled backwards in shock. It took a few moments to realize what had happened, to understand that she’d smashed the end of her metal spoon into my eye with a strength I never dreamed she had. And through my reeling horror I saw, just for a second, her reaction; the flash of satisfaction on her face before she turned away.

I had to take her with me to the hospital, Doug not being due back for several hours yet. I have no idea whether the nurse in A&E believed my story, or whether she saw through my flimsy excuses and assumed me perhaps to be a battered wife, one more victim of a drunken domestic row. If she did guess at my shame and fear, she never commented. And all the while Hannah watched her dress my wounds, listened to the lies I told about walking into a door with a silent lack of interest.

Later that evening when she was in bed, Doug and I stared at each other across the kitchen table. ‘She’s not even three yet,’ he said, his face ashen. ‘She’s only a little girl, she didn’t know what she was doing …’

‘She knew,’ I told him. ‘She knew exactly what she was doing. And afterwards she barely raised an eyebrow, just went back to hitting those damn pots like nothing had happened.’

And after that, Hannah only got worse. All children hurt other kids, it happens all the time. In every playgroup across the country you’ll find them hitting or biting or thumping each other. But they do it out of temper, or because the other child hurt them, or to get the toy they want. They don’t do it the way Hannah did – for the sheer, premeditated pleasure of it. I used to watch her like a hawk and I’d see her do it, see the expression in her eyes as she looked quickly around before inflicting a pinch or a slap. The reaction of pain was what motivated her. I knew it. I saw it.

We took her to the doctor’s, insisting on a referral to a child psychologist – the three of us trooping over to Peterborough to meet a man with an earnest smile and a gentle voice, in a red jumper, named Neil. But though he did his best with Hannah, inviting her to draw him pictures of her feelings, use dolls to act out stories, she refused, point-blank. ‘NO!’ she said, pushing crayons and toys away. ‘Don’t want to.’

‘Look,’ Neil said, once the receptionist had taken Hannah out of the room. ‘She’s very young. Children act out sometimes. It’s entirely possible she didn’t realize how badly she would hurt you.’ He paused, fixing me in his sympathetic gaze. ‘You also mentioned a lack of affection from her, a lack of … emotional response. Sometimes children model what they see from their parents. And sometimes it helps if the parent remembers that they are the adult, and the child is not there to fulfil their own emotional needs.’

He said all this very kindly, very sensitively, but my fury was instantaneous. ‘I cuddle that child all day long,’ I hissed, ignoring Doug’s restraining hand on my arm. ‘I talk to her, play with her, kiss her and love her and I tell her how special she is every single minute. And I don’t expect my three-year-old to “fulfil my emotional needs”. What kind of idiot do you think I am?’ But the seed was set, the implication was clear. By hook or by crook it was my fault. And deep down of course I worried that Neil was right. That I was deficient somehow, that I had caused this, whatever ‘this’ was. We left that psychologist’s office and we didn’t go back.

That day, the day she killed Lucy, I stood looking in at my five-year-old daughter from her bedroom door and any last remaining hope I’d had – that I’d been wrong about her, that she’d grow out of it, that somewhere inside her was a normal, healthy child – vanished. I marched across the room and took her by the hand. ‘Come with me,’ I said and led her to my bedroom. Her expression, biddable, mildly interested, only made my fury stronger. I dragged her to the bed and she stood beside me, looking down at Lucy’s head on my pillow and I saw – I know I saw – the flicker of enjoyment in her eyes. By the time she’d turned them back to me they were entirely innocent once more. ‘Mummy?’ she said.

‘It was you,’ I said, my voice tight with anger. ‘I know it was you.’ I loved that bird. I had inherited her from an elderly neighbour I’d once been close to, and during those years of childlessness Lucy had become the focus of all my attention; a pretty, defenceless little creature to take care of, who needed me. Hannah knew how much I loved her. She knew.

‘No,’ she answered, and tilted her head to one side as she continued to consider me. ‘No, Mummy. It wasn’t me.’

I left her standing by the bed and ran downstairs to the kitchen. And there was Lucy’s cage, its door swung open, the tiny headless body lying on the floor beside it cold and stiff. I looked around the room, my eyes darting wildly about. How had she done it? What had she used? She had no access to the kitchen knives, of course. Suddenly a thought struck me and I ran back up the stairs to her bedroom. And there it was. The metal ruler from Doug’s toolbox, lying on her table. I’d heard her asking him for it the day before – for something she was making, she’d said. It lay there now, next to her craft things and I stared down at it as nausea rose in me.

I hadn’t heard Hannah follow me from the kitchen until she slipped into the room and stood beside me. ‘Mummy?’ she said.

My heart jumped, ‘What?’

Her eyes fell to my belly. ‘Is it all right?’

The slight lisp, that pretty, melodic voice of hers, so adorable – everybody commented on it. I bit back my revulsion. ‘What?’ I asked. ‘Is what all right?’

She considered me. ‘The baby, Mummy. The little baby in your tummy. Is it all right? Or is it dead too?’

I put a hand to my belly as defensively as if she’d struck me there. Her gaze bored into me. ‘Why would the baby be dead?’ I whispered. ‘Why would you say that?’ There’s no way she could have known of course that she’d touched upon my greatest fear – that this new baby, our second miracle, would not survive, would not be born alive. It was the stress of my relationship with Hannah that caused this paranoia, I think. I almost felt as though I would deserve it, because I’d made such a mess of everything with her. My unborn baby would be taken from me, as penance.

As I gazed into her eyes, fear stroked the back of my neck. ‘Stay right here,’ I said. ‘Stay here until I say.’

That night I described to Doug what had happened. ‘What are we going to do?’ I asked him. ‘What the hell are we going to do?’

‘We don’t know it was Hannah,’ he said weakly.

‘Who the hell was it, then?’

‘Maybe … God, I don’t know! Maybe it was a fox, or one of the neighbours’ kids mucking about?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous!’

‘We have foxes in the garden all the time,’ he said. ‘Are you sure the back door was closed?’

‘Well, no,’ I said, ‘It was open. But …’

‘We’ve had to tell Hannah before about leaving the cage door unfastened,’ he added.

This was also true, she loved to feed Lucy, and though she knew she wasn’t allowed to open the door without me there, it was possible she had fiddled with the latch. ‘OK, but what about what she said about the baby?’ I demanded.

Doug rubbed his face tiredly. ‘She’s five years old, Beth. She doesn’t understand about death yet, does she? Maybe she’s feeling anxious about having a new sibling.’

I stared at him. ‘I can’t believe you’re saying this! I know it was Hannah. It was written all over her face!’

‘And where were you?’ he said, his voice rising too. ‘Where the hell were you when all this was going on? Why weren’t you watching her?’

‘Don’t you dare make this my fault,’ I shouted. ‘Don’t you dare do that!’ On we argued, our worry and distress causing us to turn on each other, sniping and defensive.

‘Mummy? Daddy?’ Hannah appeared in the doorway, looking sleepy and adorable in her pink pyjamas. She held her teddy in her hand. ‘Why are you shouting?’

Doug got to his feet. ‘Hello, little one,’ he said, his voice suddenly jolly. ‘How’s my princess? Got a cuddle for your daddy?’

She nodded and edged closer, but then said in a small, sad voice, ‘Is it because of Lucy?’

Doug and I exchanged a look. He picked her up. ‘You know how it happened?’

She shook her head. ‘Mummy thinks I did it, but I never did! Mummy loves her birdy and so do I.’ Tears welled, spilling from her eyes. ‘I would never, ever hurt Lu-Lu bird.’

Doug held her close. ‘I know you wouldn’t, of course you wouldn’t. It was only somebody playing a nasty trick, that’s all. Or a fox. Maybe a naughty fox did it. Come on, sweetheart, don’t cry, please don’t cry. Let’s get you back to bed.’ I knew he was fooling himself, too scared to admit the truth, but I’d never felt so lonely, so wretched, as I did at that moment. As they left the kitchen I looked up and caught Hannah watching me over her father’s shoulder, her expression impassive now. We held each other’s gaze before they turned the corner and disappeared from view.

4 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

London, 2017

When Clara answered her intercom it was Mac’s voice she heard, crackling back at her as though from a different world; an innocent, ordinary place where emails weren’t sent that stopped your heart from beating, that turned your blood to ice. ‘Jesus,’ he said after she’d buzzed him up, ‘you look awful. I tried you at work but they said you hadn’t come back after lunch so …’ he paused. ‘Clara? Are you all right?’

Without replying she led him to the computer and pointed at the screen. ‘Read these,’ she said.

Obediently he sat. She watched him as he read, his head bowed, thick black hair sticking out in all directions, his rangy six-foot frame hunched uncomfortably in the small office chair, as though he might uncoil and come springing out of it like a jack in the box. It was good to see him, the band of fear that had been wrapping itself ever tighter round her chest loosening a fraction.

Mac had been Luke’s closest friend since school and spent almost as much time at their flat as they did. He was life as she’d known it only twenty-four hours before: nights out at The Reliance, evenings in with beers and a box set, long, hung-over Sunday lunches in the Owl and Pussycat; private jokes and shared history, the comfort and ease of old friendship: he was the mainstay of her and Luke’s relationship, witness to their happy, normal life – before everything had become so entirely not normal, before the creeping awareness that everything was very far from normal indeed.

‘Holy shit,’ he said, when he’d read the last message.

‘Did you know about them?’ she demanded.

He glanced at her sheepishly. ‘Well yeah, Luke told me he’d been getting dodgy emails, but I didn’t realize they were this bad, that there were so many of them.’

Clara’s voice rose in frustration. ‘Why the hell didn’t he tell me? I can’t believe he kept them from me. They’re so nasty – some of them are fucking sick.’

‘Yeah,’ Mac said. ‘He, um, he didn’t want you to worry …’

‘Oh for God’s sake!’

‘I know, I know. I think he was embarrassed they’re from a woman.’

‘Are you kidding me? Whoever this nutcase is broke into my flat! She’s been threatening my boyfriend. What the hell was Luke playing at, not telling me about it?’ She looked at him sharply. ‘Does he know who she is?’

Emphatically Mac shook his head. ‘No. Honestly, Clara, I don’t think he’s got a clue.’

She went to the screen and read the last email aloud. ‘“I’m coming for you.” I mean, what the fuck?’ She looked around for her phone. ‘I’m going to call the police.’

Mac got up. ‘I’m pretty sure they won’t do anything until he’s been missing twenty-four hours. Look, Clara, I think these emails are from some weirdo who wants to rattle Luke – an ex maybe, but I doubt they have anything to do with him not coming home last night.’

‘Where the bloody hell is he, then?’

He shrugged. ‘Perhaps he’s just gone away for a wee while to clear his head.’

‘Clear his head? Why on earth would he need to clear his head?’

But Mac’s eyes slid away from hers and instead of replying he said, ‘I’ve called all his friends, but I guess he could be at his parents’ place. Have you tried there?’

The question made Clara pause. ‘No, not yet.’

‘Maybe you should check with them. It’s the first thing the police will do.’

Mac was right. His mum and dad’s house in Suffolk was the obvious place Luke would go – in fact she was surprised it hadn’t occurred to her before. She’d never known anyone as close to their parents as Luke. Perhaps the emails had rattled him enough to make him want to get out of London for a few days. But in that case, why hadn’t he told her?

Looking down at her phone, she hesitated. ‘What if he’s not there, though? You know what his mum and dad are like – they’ll be beside themselves.’

‘Aye, you’re not wrong there.’

She and Mac stared at each other, both thinking the same thing: Emily.

Luke never talked about his older sister and Clara only knew the bare facts: when she was eighteen, Emily had walked out of the family home and was never heard from again. He’d been ten years old at the time, his brother Tom, fifteen. He had told her a few months after they’d started dating, one night at his old place in Peckham, a shared flat off Queens Road in a dilapidated Victorian terrace, where at night they would lie in bed and listen to the music and voices carrying from the bars and restaurants squeezed into the railway arches across the street, trains thundering over the elevated tracks above.

‘And you’ve no idea what happened to her?’ she’d asked, astonished by his story.

Luke had shrugged, and when he’d spoken again there was a heaviness to his voice she’d not heard before. ‘No, none of us had a clue. She just walked out one day. Left a note saying she was leaving home, and we never heard from her again. It totally destroyed my family; my parents never got over it. Mum had a nervous breakdown and in the end it was better to never mention her. All the pictures of her got put away, everyone stopped talking about her.’

Clara had sat up, appalled. ‘But that’s awful! You were only ten, you must have wanted to talk about her, it must have devastated you and your brother too.’

The hand that had been stroking her leg paused. ‘We learnt it was better not to, I suppose.’

‘But … was there … I mean, weren’t the police involved?’

He shook his head. ‘She went of her own free will. I think that was the hardest part for my mum and dad – she left a note saying she was going, but no explanation as to why or where. My dad told me they hired a private detective to try and find her but it didn’t come to anything.’ He shrugged. ‘She completely vanished.’

And in that moment she’d understood something about Luke that had always puzzled her. Something she’d glimpsed hovering behind the laughter and the jokes, his need to be the life and soul of every party, a sorrow flickering barely there at the edges of him she hadn’t quite been able to put her finger on before.

‘What was she like?’ she’d asked softly.

He smiled. ‘She was ace. She was funny and sweet but kind of … fierce, you know? I was only ten, and I guess I’m biased, but I don’t think you meet many people like her. She was so passionate about stuff, she’d go off on all these rallies and marches, save the whale, women’s rights, you name it. Drove Mum and Dad mad because she’d never just stay still and get on with her school work. I was only a kid, but even then I admired her for it, how principled she was, how sure she was about what was right and wrong. And she was a free spirit, you know?’ He sighed and rubbed his face. ‘Maybe our house was too restrictive for her and she wanted her freedom. Who knows? Maybe that’s why she went.’

‘I’m so sorry,’ Clara had said quietly. ‘I can’t imagine how hard it must have been for you all.’

He got up, crossed the room to pull a book down from its shelf and handed it to her. It was a thin volume of children’s poems. T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. ‘She gave me this a few months before she left,’ he told her. ‘She used to read it to me when I was a kid. It was …’ he stopped. ‘Well, anyway. That’s kind of all I have left of her.’

Reverently, Clara had opened it and read aloud the message written on the flyleaf. ‘“For Mungojerrie, from Rumpelteazer. Love you Kiddo. Always, E xx” ‘Mungojerrie?’ Clara had queried, and he’d smiled.

‘They’re the names of the cats in one of the poems – her favourite one.’

He’d been silent for a while before saying, ‘Anyway, it’s all in the past now,’ and he’d taken the book from her hands and pulled her towards him and started kissing her again, to stop her questions, she’d sensed. Whenever she’d tried to bring Emily up after that, he’d simply shrug and change the subject until eventually she’d given up, though she’d found herself thinking about her often, the missing sister of her boyfriend who’d walked away from home one day, never to be heard from again.

Now, with sudden decisiveness she said to Mac, ‘I’m going to drive over there.’

His eyebrows shot up. ‘To Suffolk? How long will that take?’

She looked around for her keys and bag. ‘An hour and a half tops. At least I’ll be doing something. I can’t just sit here waiting for him, I feel like I’m going mad. And I think you’re right – I think that’s where he’ll be. He’s so close to his mum and dad. And if he has gone there because he’s freaked out by the emails, I’d prefer to talk to him face to face.’

‘OK,’ Mac said slowly, ‘but what if he’s not?’

She glanced at him. ‘Then I’ll call the police, which is another reason why I should warn Rose and Oliver first. Will you stay here in case he does come back?’

Mac nodded and patted his laptop bag. ‘Sure, I’ve a load of pictures to edit – might as well work here as anywhere else.’

She hesitated. ‘Will you call the hospitals too?’

‘Clara, I really don’t think anything …’

‘Please, Mac.’

He held his hands up in defeat. ‘OK, sure.’

As soon as Clara got into her car, she phoned her office, putting her mobile on hands-free, before setting off across town towards the M11. She was almost at the North Circular before her editor grudgingly accepted her explanation of ‘personal problems’ and agreed she could have the next day off. After that she phoned Lauren, who confirmed there’d still been no word from Luke all day. Finally she asked to be put through to the security desk where she reached George, the guard who’d been on duty the night before. He told her that Luke had left the building via the back entrance at around 7.30, that they’d had a brief chat about the football and there’d seemed nothing wrong. ‘You know Luke,’ he chuckled, ‘always got a smile on his face.’

As she drove through the London streets she thought about Luke’s parents. She remembered how nervous she’d been the first time he’d brought her to The Willows, his childhood home in Suffolk. Rose and Oliver had sounded so impressive; so very much larger than life – and so very different from her own mum and dad.

It had been a morning in late May. The house they drew up to stood alone, stark against the bleak beauty of the Suffolk landscape, the seemingly endless flat fields, the sky vast and blue and cloudless above them. Luke had led her around the side of the building through to a long and sweeping garden, its borders a carefully controlled riot of colour, a white lilac tree at its centre heavy with flowers that filled the air with their sweet powdery scent. ‘Wow,’ she’d murmured and Luke had smiled. ‘My mum’s pride and joy, you should see the parties she throws here every summer – the whole village comes along, it’s insane.’ And there, at the far end of the garden, kneeling at a flower bed, secateurs in hand, had been Rose. She’d stood up when she heard them approach, and Clara’s belly had dipped with apprehension. What would this woman, this cultured, educated, retired surgeon, think of her? Would she like her, think her good enough for her son?

But Rose had smiled, and walked towards them, and in that instant Clara had known everything would be OK. This slim, pretty, fresh-faced woman in a pink summer dress was not in the least intimidating. Instead, Clara had been bowled over by Rose’s charm, the way her eyes lit up when she smiled, the genuine warmth with which she’d hugged her, her infectious, enthusiastic way of talking. Rose had led her into the kitchen that first day and patting her hand had said, ‘Come and have a drink and tell me all about yourself, Clara, it’s so lovely to have you here.’

Oliver, Luke’s dad, had emerged from somewhere out of the depths of the house, a tall and bearded bear of a man, Luke’s features mirrored in his own, his son’s kindness and good humour shining from his almost identical brown eyes. He was a university lecturer, the author of several books on art history. Slightly shy, he was quieter and more reserved than his wife but Clara had warmed to him instantly.

In fact, she’d fallen in love with everything about the Lawsons that day: their beautiful, rambling house, the easy affection they’d showed one another, even the way they argued and joked, good-naturedly mocking each other’s flaws – Oliver’s messiness and tendency towards hypochondria, Rose’s bossy perfectionism or Luke’s inability to lose at anything without sulking. It was a revelation to Clara, who’d grown up in a house where even the smallest of perceived slights could lead to weeks of offended silence. She had been conscious, that first visit to The Willows, of the strangest feeling of déjà vu, as though she’d returned after a long absence to somewhere she’d once known well; the place where she was always meant to be.

On those early visits Clara would secretly, eagerly, look for signs of Luke’s lost sister, but never found any. Emily wasn’t in any of the framed photos in the elegant living room, and only Tom and Luke’s old preschool paintings were lovingly displayed on the kitchen walls, autographed in their childish scrawls. She had sounded like such a strong and vivid personality from Luke’s description, yet even in the small attic room that had once been hers, no trace of Emily remained. She was so carefully deleted from the fabric of her family that it somehow made her all the more present, Clara thought. What had happened to Luke’s sister, she brooded; why would someone leave this loving family home so suddenly, then vanish into thin air? The question fascinated her because, despite the Lawsons’ warm hospitality, the welcoming comfort of their beautiful home, she could feel the sadness that lingered there still, in the corners and the shadows of each room.

Over the following three years Clara would hear Emily’s name mentioned only once. It was at a birthday party for Rose, The Willows full to bursting with friends from the nearby village, ex colleagues of hers from the hospital, Oliver’s writer and publishing friends and what felt like the entire faculty of the university he taught at. Oliver had been extremely drunk, regaling Clara with an anecdote about a recent research trip when suddenly he had fallen silent, staring down at his drink, apparently lost in thought.

‘Oliver? Are you OK?’ she’d asked in surprise.

He’d replied in a strange, thick voice, ‘She meant the world to us you know, our little girl, we loved her so very much.’ And to her horror his eyes had filled with tears as he said, ‘Oh my darling Emily, I’m so sorry, I’m so very sorry.’ She had stared at him, frozen, until Luke’s brother Tom had appeared and gently led him away, murmuring, ‘Come on, Dad, time for bed now, that’s right, off we go.’

At last Clara left London behind and joined the M11. It should only take her another hour or so to reach Suffolk. Would Luke be there? She gripped the steering wheel tighter and pressed her foot on the accelerator. Surely he would – he had to be. Unbidden, the emails she’d read earlier came back to her – It’s going to be soon, Luke, your funeral’s going to be very soon – and she felt again the knot of fear tightening in her stomach.

She reached The Willows as the sun began to set. As she got out of the car and gazed up at the house, cawing jackdaws circled above the surrounding fields in the twilight sky. This moment of stillness before nightfall seemed to capture the place at its most magical. It was an eighteenth-century farmhouse, clematis and blood flower clambering over its red bricks, an ancient weeping willow shivering in the breeze. On either side of the low, wide oak door, crooked, crown-glass windows offered a glimpse into the beautiful interior beyond. It was a house out of a fairy story; enchanted and remote beneath this endless empty sky. She approached the door now, taking a deep breath before she knocked. Please be here, Luke, please, please, just be here.

She heard the familiar sound of their ancient spaniel, Clementine, bounding to the door, followed by the latch being raised. It was Oliver who opened it. He peered out at her, not seeming to recognize her at first, clearly wary to have someone appear out of the blue, they were so remote and alone out here. Eventually, his expression cleared. ‘Good Lord, Clara!’ He turned and called behind him, ‘Rose, it’s Clara! Oh do calm down, Clemmy! Come in, come in, what a lovely surprise. What on earth are you doing here?’

She glanced over his shoulder to the cosy glow of the room behind him and felt the house’s familiar pull. She caught the smell of something cooking and pictured Rose in the kitchen listening to Radio Four while she made dinner, a welcoming, irresistible scene of affluent domesticity, so different from the chilly semi-detached she’d grown up in in Penge. But before she could reply, Rose came running up behind him. ‘My goodness, darling, hello! Where’s Luke?’ She looked beyond Clara to the car, her expression pleased and expectant.

Clara’s heart sank. Shit. ‘He’s not with me, actually,’ she admitted.

Oliver frowned. ‘Oh?’ he said, adding gallantly, ‘Oh well, how lovely to see you anyway. Come in, come in!’

But Rose was still smiling at her. ‘Why not?’ she asked.

‘You haven’t heard from him, then?’

‘No, not since the weekend.’

Before Clara could say anything else, Oliver was ushering her through to the kitchen. ‘Come in! Come in and sit down.’

While Rose bustled about putting the kettle on and Oliver chatted about a new book he was researching, Clara leant down to stroke Clemmy, and wondered how to begin.

Finally, Rose placed the tea on the table in front of her and, sitting down, said mildly, ‘So, my darling, where’s that son of ours?’

Clara took a deep breath. ‘Nobody’s seen Luke since yesterday evening, around seven thirty,’ she told them. ‘He emailed me to say he was coming home but he didn’t turn up and he doesn’t have his mobile on him. He had an important interview today, as well as a big meeting at work … but nobody’s heard anything from him.’ She looked from one to the other of their faces. ‘It’s just not like him and I’m so worried. I thought he might have come here, but …’

Oliver looked perplexed. ‘Well … perhaps he’s gone to stay with friends, or …’

Clara nodded. ‘The thing is, and it might be nothing, but he’d been getting these weird emails lately, and a few things had started to happen. A break-in at our flat, and dodgy phone calls, and, well, photographs. We hadn’t wanted to worry you, so …’

‘Phone calls? Photographs? What sort of photographs?’ asked Rose in bewilderment.

‘Whoever it was had been following Luke, taking pictures, I think they were meant to scare him.’

Rose’s face suddenly drained of colour behind her carefully applied make-up. ‘What did the emails say?’

‘They weren’t very nice,’ Clara admitted. ‘Quite threatening, saying they were going to come after him, talking about his funeral …’

‘Oh God. Oh dear God.’ Rose put a trembling hand to her mouth.

‘I don’t—’ Clara began, but was interrupted by the sound of floorboards creaking overhead, then footsteps on the stairs. She looked from Rose to Oliver in confusion. For a strange, chilly moment she wondered if it was Luke she could hear – the disquieting thought occurring to her that his parents had lied to her, that Luke had been here all along. It took her a second or two to recognize the man who appeared at the kitchen door as Luke’s older brother, Tom.

They stared at each other blankly for a moment until Tom said, ‘Clara! What – where’s Luke?’

She watched Tom as he listened to his father explain the reason for her visit. She had never quite been able to get a handle on Luke’s older brother. Perhaps it was because the rest of the Lawsons were so welcoming that Tom’s reticence was more noticeable, but it had long seemed to her that he kept himself a little apart from his family, that his aloofness almost bordered on disdain. And though he’d always been polite enough to her on the rare occasions that they met, she’d never quite managed to break through his reserve.

It was unusual to find Tom at The Willows at all, in fact. Although he lived relatively nearby, in Norwich, he was not as close to Rose and Oliver as his younger brother, visiting far less frequently than Luke. Unlike Luke, he took after their mother physically, rather than Oliver, having inherited her high cheekbones and blue, almost turquoise eyes – though apparently none of her natural warmth. She remembered Luke telling her once that Tom had split from a long-term girlfriend a year or so before, though Luke hadn’t known why. ‘That’s Tom for you,’ he’d said. ‘Closed bloody book when it comes to that sort of stuff.’

‘He’s probably just drunk somewhere,’ Tom said now with the elder-sibling dismissiveness she knew drove Luke crazy. She bit back a rush of irritation, and managed to murmur politely, ‘I hope so.’

‘But what about this stalker person?’ Rose asked anxiously.

Tom shrugged and, going over to his parents’ extensive wine rack, helped himself to a bottle. ‘Probably some unhinged ex of his,’ he said, reaching for a glass. ‘God knows he’s had enough of those.’ He glanced at Clara and perhaps catching her annoyance looked a little abashed and added more kindly, if patronizingly, ‘I’m sure he’ll turn up soon. I really wouldn’t worry.’

At that moment Rose gripped her husband’s arm. ‘Oh, Oli, where is he? Where is he?’

‘Tom’s right. He’ll turn up,’ Oliver murmured, putting a comforting hand over hers, but though his voice was reassuring, Clara saw the worry in his eyes.

She got to her feet. ‘I’m so sorry for upsetting you all like this,’ she said miserably.

‘What will you do now?’ Tom asked.

‘I’ll call the police as soon as I get home, if he’s still not back. He’ll have been missing for twenty-four hours by then, so hopefully they’ll take it seriously.’ She looked around for her bag.

‘That’s actually a myth, you know,’ Tom replied.

She blinked. ‘What is?’

‘That you have to wait twenty-four hours. You can report someone missing whenever you like – the police still have to take it seriously.’

She picked up her bag, ignoring his know-it-all tone. ‘Well anyway, I’ll be off now,’ she said. ‘Mac’s back at the flat, calling around the hospitals. Just in case,’ she added, seeing Rose’s alarmed expression.

‘Oh God, oh dear, I don’t …’ Flustered, Rose got to her feet.

‘I’m sure he’ll turn up,’ Clara said with more conviction than she felt. ‘Tom’s right, he’s probably had a heavy night and is sleeping it off somewhere. I’m only going to ring the police to be sure.’

Rose nodded unhappily. ‘Will you phone me when you’ve spoken to them?’ She and Oliver looked so fearful that Clara wished she hadn’t come. For the first time since she’d met them, their characteristic energy and vitality seemed to slip, and though they were only in their sixties still, she caught a disconcerting glimpse of the frail, elderly people they would one day become.

‘Of course,’ she said firmly. ‘Straight away.’ Quickly she hugged Rose and kissed Oliver on the cheek before raising her hand and giving Tom a brief wave of farewell. ‘I’ll speak to you soon. I’m so sorry, but I’d better head back now.’

As soon as she got in her car she phoned Mac. ‘Any news?’ she asked.

‘No. The hospitals say no one’s been admitted who fits his description – no one who hasn’t already been identified anyway.’ He paused. ‘I take it his mum and dad haven’t heard from him?’

‘No,’ she said quietly.

‘Shit.’ There was a silence. ‘How’d they take it?’

‘Not brilliantly. Rose was very upset.’

‘Fucking hell, I’m going to kill that dozy bastard when I see him.’

She gave a weak laugh. ‘Oh God, Mac. Where the hell is he?’

Mac didn’t reply for a moment, and then in a voice completely unlike his, said, ‘I don’t know, Clara. I really don’t know.’

5 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

Cambridgeshire, 1987

Our son, Toby, was born a few weeks before Hannah’s sixth birthday and from the very first moment he was a joy. I adored being his mother; the way his little eyes would follow me around the room, how he’d reach for me as soon as I drew near – the almost telepathic way we communicated. It was as though we were one person; he seemed to melt into me when I held him, his head tucked tightly under my chin, the skin of his body warm against mine. I felt as though finally I was loved and needed in the way I’d always dreamed of being. We adored each other, it was as simple as that, and yes, I guess it did make Hannah feel pushed out a bit.

But I tried hard to make her feel included. I followed the advice in every book I could find about sibling rivalry, did my best to show her she was loved as much as her brother. It almost always backfired. ‘Today we’re going to have a Hannah and Mummy day,’ I told her one morning over breakfast. ‘What would you like to do?’ I asked her brightly. ‘Anything you want!’

She stared balefully back at me as she shovelled Shreddies into her mouth, but didn’t reply.

‘Swimming? Cinema?’

Still nothing.

‘Shopping for a new toy?’

She shrugged.

‘Shopping it is then!’

We drove to the nearest town with a large toy store in its centre. ‘We can go for tea and cakes first,’ I suggested. ‘Isn’t this fun? Us girls together? You’re such a big girl now, perhaps we can choose a pretty dress for you.’ She just stared out of the window while I prattled on.

The shop was one of those lovely old-fashioned ones selling tasteful and expensive handmade toys for the sort of parents allergic to plastic. It wasn’t the kind of place I usually shopped in, but I’d wanted to buy Hannah something really special and original. We wandered the aisles, but though I pointed out countless dolls, games and stuffed toys, she barely glanced at them, staring back at me with undisguised boredom. I began to lose my patience. ‘Come on, love, you can have anything you want, just take a look!’

It was at that moment that I spotted, at the far end of the shop, someone I used to know from the village I grew up in. I completely froze, my heart pounding at such a strange and unexpected shock. I ducked my head and turned quickly away, hurrying along another aisle. I couldn’t face the questions that would have been asked, the inevitable fishing for details as to why Doug and I had left so suddenly all those years before.

Hiding behind a display of teddy bears I looked around for Hannah, my heart sinking when I realized she wasn’t there. ‘Hannah!’ I hissed, ‘Where are you?!’ At last I spied my former neighbour leaving and heaved a sigh of relief. At that moment Hannah appeared from around the corner.

‘I want to go home,’ she said.

I was too drained to argue any longer. ‘Fine. Have it your way.’

It was as we were leaving that I felt the hand on my arm. I turned to see a middle-aged woman glaring at me with obvious distaste. ‘You’ll have to pay for these,’ she said, tight-lipped.

It was then that I noticed her ‘Manager’ badge. ‘I’m sorry?’ I asked.

She held out her hand, filled with what looked like tiny wooden sticks. ‘She did this, I saw her,’ the woman said, nodding at Hannah. ‘You’ll need to pay for them. Would you come this way, please?’

I realized then that what she was showing me was the beautiful set of hand-painted wooden dolls from the eye-wateringly expensive doll’s house I’d pointed out to Hannah when we’d first arrived. Every single one of them had had their heads and limbs snapped off. I looked at Hannah who gazed innocently back at me.

We drove home in silence. When I unlocked the front door I all but ran to Toby, grabbing him from Doug’s arms and burying my face into his comforting, warm little neck, hurrying up to my bedroom and shutting the door behind us.

From the beginning, Doug and I dealt with Hannah’s behaviour very differently. I still had the faint scar at the corner of my eye, the sight of Lucy’s empty cage stashed forlornly in our garage to remind me what she was capable of. Toby was a very clingy baby who hated to be put down, and occasionally I’d glance up to see Hannah watching us together, gazing over at us in such an unsettling manner that it made me shiver.

So, yes, I guess I was a little over-protective of my baby son, wary and watchful of my daughter whenever she was near. As he was breastfed I always had an excuse to keep him close by me, but soon Doug began to resent me for what he saw as me monopolizing our boy. ‘You’ve made him clingy,’ he’d complain when Toby would cry for me the moment he tried to pick him up. It was as though he thought I was deliberately keeping his son from him, but that just wasn’t true.

Doug’s way of dealing with Hannah was to lavish her with attention, no matter what she did, as though he hoped the force of his love alone might steer her on the right track. If he came home from work, for example, and found her on the naughty step, he would – much to my annoyance – scoop her up and give her a biscuit, taking her with him to the living room to watch her favourite cartoon on TV, while I played with Toby in a separate room. Slowly our family began to divide into two, with Toby and me on one side, Doug and Hannah on the other. It was true that she was much better behaved when she was with her father, but I sensed that she enjoyed the growing rift between Doug and me. I saw the spark of pleasure in her eyes when we argued, how happy she seemed when we ate our meals in offended silence.

A few months before Hannah turned seven Doug and I were summoned, yet again, to the school to talk about her behaviour. We’d had a row earlier that morning and drove there in almost complete silence, Toby sleeping in his car seat behind us, Doug staring grimly at the road ahead. As we drove I brooded over Hannah. Had I caused it, whatever ‘it’ was? Had the pain of those years of childlessness affected how I’d bonded with my first child? I had felt so broken, so utterly alone back then; nobody had understood, not really – not even Doug. In my misery and isolation had I put up such a self-protective wall between myself and the world that it’d made my heart harder, incapable of fully loving and accepting my daughter when she finally came along? Is that what she sensed and railed against? I stared out of my window, trying to fight my tears, until we drew up in front of West Elms Primary.

The school tried its best to be understanding, Hannah’s young teacher earnestly offering us strategies and action points to help deal with our delinquent, troubled daughter, giving us leaflets to read, suggesting counselling – before quietly intimating that Hannah would eventually be asked to leave if it continued, that they had the other children to consider, after all. ‘Does she have any friends?’ I asked miserably.

Miss Foxton sighed. ‘She tends to select a certain type of child with whom to attach herself; the more vulnerable and easily led types. Hannah can be very persuasive when she puts her mind to it. She’ll allow that child to be her ally for a time, and then she’ll grow bored and turn on them completely. It’s a pattern we’ve witnessed repeatedly.’ Her eyes slid away to the pencil she was fiddling with. ‘Daisy Williams is one example, of course. But no, I’ve never seen her truly befriend anyone as such.’

I nodded, remembering Daisy. Shy and eager to please, she was a very pale, thin child with white-blond hair and red-rimmed eyes who reminded me a little of a skinned rabbit. Hannah had homed in on her during the previous school term, enjoyed her new friend’s admiration and slavish devotion for a few weeks, before Daisy had been found, tied up with her own skipping rope and soaking wet, in the playground toilet block. Hannah, all wide-eyed innocence, had maintained that they’d merely been playing a game of cops and robbers, and Daisy had eagerly backed up this claim, but from then on the school had done everything they could to keep the two girls apart, at the insistence, I was sure, of Daisy’s mother, who glared at me with open hostility whenever we crossed paths in the playground.

After our talk with Hannah’s form teacher we walked back to the car in miserable silence. ‘Oh, Doug,’ I said when I was sitting in the passenger seat.

He looked at me and sighed. ‘I know.’ He reached over and took my hand, and for a second something of the old closeness between us flickered. He opened his mouth to speak but at that moment Toby woke and began to cry.

I glanced at Doug and began to open my door. ‘I’d better sit in the back with him,’ I said. Doug nodded, put the key into the ignition and we drove home without another word.

A few days after the school meeting we sat Hannah down and told her what her punishment would be. It was always hard to discipline her because it was difficult to find anything – any treat or toy – that she was genuinely attached to: she literally didn’t care if I confiscated any of her belongings. The only thing she really liked to do was watch television. So on that occasion we told her there’d be no TV for a week. I don’t think I’ll ever forget the look of fury, of pure venom on her face when we gave her the news.

I found the bruise on Toby’s arm the next day. Earlier in the morning I’d left him sitting in his little bouncy chair while I got Hannah ready for school. It was as I was fetching her some clean socks from the tumble dryer that I heard his howl of pain. I raced back up the stairs and there he was, red-faced and hysterical, though moments before I’d left him cooing happily. When I went to find Hannah she was sitting in exactly the same spot on her bedroom floor, placidly doing a jigsaw puzzle. She didn’t even look up when I came in. It wasn’t until later that I found the bruise; a small, angry, purple mark on Toby’s upper arm – as though, perhaps, he’d been pinched very hard. I couldn’t prove it was Hannah, but I knew that it was. Of course I did.

6 (#ue70a4556-8226-543c-897a-85987657e7d8)

London, 2017

Shell-shocked, Clara and Mac walked back from the police station. When they’d arrived and told their story to the young officer at the front desk, he’d appeared unimpressed at first, listening with studied patience as Clara haltingly went through her story. His attitude had changed, however when, putting Luke’s laptop on the desk in front of him, she described the hundreds of threatening emails, the break-in a few months before, the letter and the photographs stuffed through their door.

‘I see,’ he’d said. ‘If you’ll just come with me please.’ She and Mac had been ushered through to a small, windowless room and told to wait. They’d sat in nervous silence as they listened to footsteps come and go in the corridor beyond the closed door.

When it opened they were greeted by a slender black woman who introduced herself as Detective Constable Loretta Mansfield. Briskly she approached them and shook their hands with a firm dry handshake, her eyes quickly searching theirs as she smiled, before sitting down and placing Luke’s laptop on the table between them. ‘Right, Clara,’ she said, ‘I’ve had a chat with my colleague about Luke, and what we’re going to do next is fill in a missing person’s report.’

Clara swallowed hard, her mouth dry with nerves as she went over again what she’d told the officer on the front desk, DC Mansfield’s calm, almond-shaped eyes flicking up to meet hers at various points in her story.

‘And there’d been no arguments between you recently,’ she asked, ‘no indication that Luke might want out of the relationship?’

‘No! And as I said, he’s left his mobile and credit card, and he had an important interview at work he’d prepared hard for. We were … happy!’ she heard her voice rising and felt Mac’s hand on her arm.

Mansfield nodded, then opened the laptop and read through the emails. ‘I see.’ When she looked up again, she cleared her throat decisively. ‘OK, Clara, I’m going to hang on to this for now, and talk it over with my sergeant in CID. What I suggest you do now is go home and wait for us to get in touch, and in the meantime, if you hear from Luke, or if anything else suspicious happens, please call us straight away.’ She got up and with another brief smile and a nod of her head, indicated for Clara and Mac to follow her.

But Clara remained seated, staring up at her in alarm. ‘CID? So you agree those emails could be linked to his disappearance?’ She had half hoped to be fobbed off, to be told she was overreacting, that there was clearly an innocent explanation for it all. The seriousness with which Mansfield was taking her concerns caused darts of panic to shoot through her.

‘It’s possible,’ the DC said. ‘There could be any number of reasons why he’s taken off for a bit. He might have gone out and had a few drinks and not made his way home yet – that happens. Hopefully there’s nothing to worry about. But as I said, go home, and someone will be round to see you as soon as possible. We have your address.’ She went to the door and held it open, and reluctantly Clara got to her feet.

‘Are you all right?’ Mac asked as they trudged back down Kingsland Road towards home.

‘I don’t know. It all feels so strange. You see on the news and stuff about people disappearing, you see those Facebook appeals, and I can’t believe he’s one of them, it’s too surreal. Half the time I’m telling myself there’s some rational explanation and I should just chill out, the other half I feel guilty because I’m not tearing through the streets searching for him. I don’t know what to do.’

He nodded gloomily. ‘He’ll turn up. It’s going to be OK. They’ll find him,’ but she could hear the worry in his voice. As they walked she thought about Mac and Luke, and the friendship they’d had for so many years. Of the two of them, Luke had always had the loudest personality, Mac with his quiet dry wit the straight man to Luke’s clown. And if Luke’s love of the limelight meant he sometimes didn’t know when to quit, ensuring he was always one of the last to leave any party, Mac was invariably there to keep his friend out of trouble, bundling him into a cab when he’d had too much to drink, ensuring that he eventually made it home in one piece. Instinctively now she reached out and linked her arm through his, more grateful than she could say for his calm, steady presence. He glanced down at her and smiled, and together they walked on in silence.

She felt desolate when they returned to the empty flat. There was Luke’s leather jacket hanging on its peg; on the table by the window was a half-completed Scrabble game they’d abandoned two nights before. The last record they’d been listening to sat silent and still on the turntable. It was as though he’d stepped out only moments before, as though he might reappear at any second with a bottle of wine tucked under his arm, smiling his smile and calling her name. He hadn’t taken anything with him – not one single thing a person who was intending to leave home might take.

Mac came and stood beside her. ‘Would you like me to stay over?’ he asked. ‘I could sleep on the sofa.’

She smiled gratefully, suddenly realizing how much she’d been dreading another night alone. ‘Thanks, Mac,’ she said.

She was awoken by the sound of her intercom buzzing. Groggily she sat up, looking about her in confusion, surprised to see that she was still wearing her clothes. The fact of Luke’s disappearance hit her like a train and she gasped in distress. She remembered she’d gone to lie down while waiting for the police to come, had put her head on Luke’s pillow, breathing in the scent of his hair and skin, a feeling of utter hopelessness filling her; nervous exhaustion rolling over her in heavy waves. She must have fallen asleep.

Dazedly she stumbled to her feet and going into the living room saw Mac blinking awake on the sofa. She glanced at the clock: eight a.m. Again the intercom buzzed loudly and she hurried over to answer it. ‘Hello?’

‘Miss Haynes? DS Anderson from CID. Can I come up?’

He was a large man, Detective Sergeant Martin Anderson. Mid-thirties, a slight paunch, small blue-grey eyes that regarded her from the depths of a ruddy face. A proper grown-up, with a proper grown-up job: even though he was less than a decade older than Clara and Mac, he might as well have belonged to an entirely different generation. She clocked his wedding ring and pictured a couple of kids at home who idolized him. A very different sort of life to the ones led by her and Mac and their friends, with their media jobs, their parties and endless hangovers. He was accompanied by DC Mansfield, who nodded at her and flashed her brief, impassive smile.