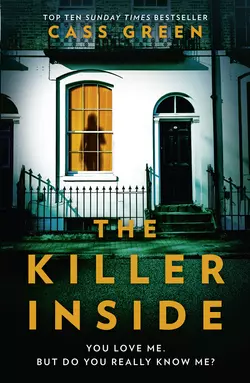

The Killer Inside

Cass Green

‘Dark, twisty and menacing, I couldn't put it down!’ Roz Watkins You love me. But do you really know me? The gripping new thriller from the Sunday Times bestseller A perfect childhoodYou were the golden girl. The apple of your parents’ eyes. My beautiful, clever wife. A perfect marriageI would do anything for you. But some things about me must stay hidden. A perfect liarOne summer afternoon, it all begins to unravel. Because I’m not the only one with terrible secrets to hide. And when the truth comes out, it seems we both have blood on our hands… ‘So complex, so twisty, so compelling’ Rachel Abbott ‘A compulsive, addictive read, cast with unnerving characters and a premise that packs a real emotional punch’ Lucy Clarke

THE KILLER INSIDE

Cass Green

Copyright (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Caroline Green 2019

Caroline Green asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design by Sim Greenaway © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Stephen Mulcahey/Arcangel Images, Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008287245

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780008287252

Version: 2019-07-29

Dedication (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

Dedicated to The Sibs: Helenanne Hansen and Charlie Green

Contents

Cover (#u60df5f98-337b-508f-afd1-e32f99d2a429)

Title Page (#ue99d944e-64f1-5838-a003-8850b90bfbb5)

Copyright

Dedication

Summer 2019

Summer/Autumn 2018: Elliott

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Spring 2003: Liam

Autumn 2018: Elliott

Irene

Summer 2003: Liam

Autumn 2018: Elliott

Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Elliott

Winter 2018: Elliott

Autumn 2003: Liam

Summer 2019: Elliott

Autumn 2003: Liam

Summer 2019: Irene

Elliott

Elliott

Summer 2019: Liam

Elliott

Elliott

Spring 2021: Irene

Elliott

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cass Green

About the Publisher

SUMMER 2019 (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

There are three people alive inside the whitewashed family home at one pm on this sunny afternoon in late July. And because not much happens on this quiet road in this quiet seaside town, the first gunshot could perhaps be mistaken for a misfiring exhaust.

But at this time of the afternoon, there is only a young man walking an elderly West Highland terrier on the road and he is lost in the music pumping through high-end, noise-cancelling headphones. Oblivious to the shriek of the seagulls and the rhythmic smash of surf against rock, he doesn’t hear the sharp retort of the gun or the screaming in its aftermath either.

By the time the second shot comes – at 1.34 pm – he is long gone. The only witness to the violence is a seagull perched on the back wall, which tumbles into the air in outrage at the sound.

It is less than a minute later when the gun fires for the third time.

SUMMER/AUTUMN 2018 (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

ELLIOTT (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

That festival was a big deal in our part of the world.

Just up the road from the seaside town we called home, the End of the Summer event was usually a low-key, family-run affair with a number of acts you’ve probably never heard of.

But this year was very different. For some complicated reason involving a favour by Dave Grohl, The Foo Fighters – one of the biggest bands in the world – were headlining. The band is the mutual favourite of me and my wife Anya and as soon as I heard about it, I knew we had to be there.

Tickets went on sale at nine am on a day in June, when my Year Five class was doing guided reading, followed by maths. I told them they were going to watch Planet Earth as a treat for being good (not true – they had been little bastards the day before) while I endlessly pressed redial on my phone with one hand, the other attempting to access ever-crashing ticket websites on the school computer. When it got to ten am I had to stop briefly to let the class out to play, before racing to the staffroom to continue.

When I got the automated message telling me, with totally unwarranted cheerfulness, that, ‘Due to exceptional demand, tickets to the End of the Summer festival are now sold out,’ I said, ‘Bollocks,’ loud enough and with sufficient heat that some of the older guard in the staffroom gave me pinched looks.

But then, the weekend before the event, a miracle occurred.

My friend at work, Zoe, knew someone roadying, and she was able to get her hands on two extra tickets; one for me, and one for Anya.

We were ecstatic. It was the very last weekend before the schools were back and it felt like a perfect way to end the summer.

And anyway, Anya needed cheering up.

We’d only been ‘trying’ as they say (such a weird expression because actually, we were quite good at it) for six months or so. But each time her period arrived, she became more dejected and withdrawn. The last time she’d claimed she ‘had a real feeling’ even though she was only overdue by a day or two. She made me laugh by saying things like, ‘Will you still fancy me when I am big with child?’

Maybe the humour was a disguise for how high her hopes had been raised.

On the day of the festival, we woke up to mizzling, nasty rain in the air and a low-slung sky. Anya was quiet that morning. I tried to chivvy her with some lame jokes, but she just smiled weakly and it was somehow worse than rolled eyes. When I asked what was wrong, she said she had a bit of a headache and I decided not to press.

Clad in wellies and waterproof coats, we arrived at the festival in a downpour. Our feet were sucked into claggy, viscous mud straight away and we were sweating inside our jackets.

I took the decision that the best way to fight off the vagaries of the weather was to drink as much as possible.

By late afternoon, I didn’t mind the mud.

And finally, at six, the sun came out.

We’d seen a weird kind of emo rock band and a folk-punk duo I like, plus some comedy in one of the tents. The main event was still to come.

I made my way back to Anya with two more wobbly pints of cider in my hands that I’d had to queue painfully long for. Her head was turned away from me and, as I reached her and said, ‘Hey,’ she seemed to startle.

‘You’re shaking,’ I said, noticing her hand as she took the plastic glass from me. ‘Are you cold?’

She gulped a long mouthful. Her eyes when they met mine were oddly bright. She seemed to be crackling with energy in a way that happened sometimes. It was very sexy.

‘It’s nothing,’ she said and turned to look at the stage. This was clearly a lie.

‘Hey,’ I said again, placing my hand on her slim arm, which was covered in goose bumps. ‘Did something happen?’

She shook her head vigorously. ‘People are dickheads, that’s all. Some bloke knocked into me and wasn’t very sorry.’

‘Where is he?’ I said, turning to look at the thickening crowd.

‘Gone,’ she said and gave me a wonderful smile that seemed to come from nowhere. ‘Let’s forget it, okay?’

‘Okay, if you’re sure.’ I took a swig of my pint.

I allowed myself to relax and soak up the buzz of the crowd. Soft evening light bathed us. The nearest group of people included a small girl whose face was painted like Spiderman, and a man in shorts with an Oasis T-shirt that seemed to have come from younger, slimmer times straining over his belly. He was bellowing about seeing Oasis at ‘Glasto’ to a small, middle-aged woman with a long-suffering expression.

Anya took a sip of her pint and did a little turn to survey the crowd. She was wearing what she called her ‘festival dress’, a long, hippyish affair with thin straps and a brown hem of mud, her waterproof coat tied around her waist. I didn’t resist the urge to kiss her freckled shoulder and she gave me a quick, warm smile.

There was a palpable thrum of excited energy in the crowd. The thing we’d all been waiting for was happening any moment now.

I heard someone call my name and turned to see Zoe squeezing her way towards us through the knots of people, grinning.

Zoe was almost six feet tall with her afro and, even though I had repeatedly told Anya that I hadn’t really noticed, you’d have to be insane not to recognize that she was kind of gorgeous. She wore thick-framed glasses that would have made anyone else look like Morrissey on a bad day, but highlighted her big, brown eyes, and she always had on brightly coloured lipstick. She could be stern when needed but the kids adored her; she had even won over some of the racist old parents round here.

The fact that she stood out at all was one of the downsides of living in this small, seaside town. I was born and raised in the crowded, multi-cultural heart of London and, well … it was an adjustment. I’d been asked more than once here – with a note of suspicion – if I was an Arab, because of my dark colouring and beard.

This place had its downsides, which sometimes made me want to run screaming back to the city, but it was also beautiful, cheap enough, and, therefore, home.

Zoe was my best friend at work – and, by default, probably in the town – but I sensed a tightening in Anya’s expression whenever her name came up. So, I tried not to talk about her too much. That Anya could ever be a bit territorial and jealous was, frankly, something I still found flattering.

Anyway, Zoe was looking great at the festival, in some sort of orange catsuit thing with a thick yellow scarf around the front of her hair. She pulled me into a hug and I could sense Anya tensing next to me.

‘Everything okay?’ Zoe said, turning to Anya.

She gave her an odd sort of look, but I didn’t think anything of it then.

Anya’s smile was tight. ‘Yeah, brilliant,’ she said. ‘And we’re so grateful for the tickets, aren’t we, Ell?’ But she reached for my fingers at the same time and it felt like she was making a point.

Zoe didn’t seem to notice anyway. She began to tell me a story about one of the mothers saying her son didn’t have any time to do an after-school club any more because ‘one of his tutors’ was changing days.

‘One of them?’ she said now. ‘He’s ten years old!’

Our school didn’t have too many pushy parents, but a slow gentrification process was happening in the town, which meant a new demographic of parent. We didn’t have any Octavias or Gullivers. Yet. Kept things interesting, anyway. I listened to the story and laughed at the right bits but was acutely conscious of Anya standing silently next to me the whole time.

After a few moments a tall woman with a shaved head and Cleopatra-like eyes came over, clutching two bottles of beer, one of which she thrust at Zoe.

‘Oh cheers,’ said Zoe. ‘This is Tabitha. Tab … Elliott, my partner in crime at school. And his wife Anya.’ We all nodded our hellos.

‘By the way,’ said Zoe, turning to me again. ‘You still okay to get started on the Charney Point visit? It has to be done quickly because they’re closing for a major refurb in October.’

This was a trip for Year Five to go to a Viking museum that was about ten miles down the coast. I’d logged it onto the school calendar and needed to remember to fill out all the risk assessment stuff. I made a mental note.

‘Safe in my hands, Miss,’ I said with a little salute. Zoe grinned and then our attention was diverted by a change in energy in the crowd. The background music abruptly stopped.

I always love that moment when the band is just about to come on. The anticipation reaches a kind of critical mass. You can feel the wave of energy that’s gathering force before it crashes down over you, drenching you in euphoria.

There was a loud roar as the lights at the side of the stage began to strobe the crowd, even though it wasn’t yet dark.

Anya squeezed my hand and whispered, ‘I didn’t know.’ She was grinning wildly now, happier than I had seen her all day.

When she saw my look of bafflement, she nodded at Zoe and Tabitha, whose fingers were entwined.

I stared.

‘I didn’t either.’

Zoe saw us looking over at her.

‘There’s only so much diversity Beverley Park Primary School can take, isn’t there?’ she shouted with a grin.

I laughed, but it was forced. Surely, I wasn’t someone Zoe felt she had to hide anything from? I was her mate. But had she actively kept it from me, though? Had I ever bothered to ask about a boyfriend or a girlfriend, even though Anya repeatedly tried to pump me for this sort of information? Well …

My thoughts were interrupted by a thunder of cries from the crowd, so loud I felt them thrumming through my feet, and the band bounced onto the stage.

Dave Grohl shouted, ‘Are we fuckin’ ready?’ and everyone went wild.

A few songs in and my throat was aching from shouting and singing along. Forests of arms in exultant Vs waved before us and I couldn’t control the daft grin on my face. I glanced at Anya and saw she was trying to crane her neck to get a better view. The group in front of us were all unusually tall.

I nudged her and pointed to my shoulders, waggling an eyebrow suggestively.

She shook her head and laughed, mouthing, ‘No way.’

I got down onto my haunches and patted my shoulders again.

‘Come on!’ I yelled. ‘I can take it!’

Anya was giggling now, eyes gleaming.

‘I’ll break your neck!’ she shouted. I turned and gave her a hurt look.

‘Are you casting aspersions on my manliness?’

Chortling almost helplessly, she hitched up her long skirt and carefully wound one leg over my shoulder, then the other, holding onto my head as she wobbled into position.

In truth, she was an awful lot heavier than I’d expected her to be at this unfamiliar angle. Plus, I realized that I was actually quite drunk. But I was a determined man. As I struggled to my feet, Anya sliding around on top of me, I felt a warning twinge of pain in my lower back and a burst of masculine pride all at the same time.

The band began to play the opening chords of ‘Everlong’.

Despite the pain increasing by the second in my back, warm, sweet contentment spread through all my synapses. Anya’s hands were in the air, my fingers clasped around her slim ankles. My mind was fuzzy from cider, but I knew somehow this would be one of those moments I wouldn’t forget. I even pictured myself doing this with a child one day; carrying a little boy or girl on my shoulders and pointing out planes, dogs, cars …

We’d be the sort of parents who still went to gigs, too.

I don’t really know what happened next. It felt as though she shifted and I slightly lost my balance. For a heart-lurching few moments I thought we were both going to smash face down into the people in front.

She shouted above the music, ‘Down! Let me down!’

I crumpled awkwardly to my knees and Anya climbed off my shoulders so abruptly she almost wrenched my head off.

‘What happened?’ I said, rubbing my neck. It came out more angrily than I’d intended, but I was in pain.

‘You almost dropped me, that’s what happened,’ she said. Her eyes looked huge, stricken, in her ashen face. Then she said, ‘I want to go home.’

For a moment all I could do was stare at her. Anya was usually the last person dancing when they turned the lights off. I’d literally never heard her say anything like that before. I didn’t know what to do with it.

‘I mean it, Ell,’ she said and that was when I saw her eyes were brimming over with tears.

‘What’s wrong? What is it?’

‘I don’t feel well.’ She swiped at her eyes with the heel of her hand. ‘There’s something going around at work. Maybe it’s that. Or maybe it was that kimchi earlier. I should have had the burger, like you did.’

The thought of leaving before the end of this much-anticipated gig made resentment burn like acid in my guts. I wanted to say, ‘I’m not going anywhere. You do what you want,’ like a disappointed little kid. The words were right there, about to spill out. Then I saw how sickly and green she looked. What kind of person would that make me? Especially as I had almost caused her to break her neck.

I pulled her into my arms and could feel her trembling.

‘Okay,’ I said, and began to lead her through the crowd.

It took us for ever to get through the press of sweaty, beaming faces that turned to frowns as we pushed past. The air smelled of sun cream, beer, and sweat, with the odd sweet waft of weed.

When we got to the gates I turned to her, to make one last bid.

‘Are you absolutely sure about this?’ I said.

‘I need to go home,’ she said, and with that she threw up all over my shoes.

Twenty minutes later, we were in an Uber. Anya had barely said a word since being sick. I’d hurriedly offered her water and called the cab, then she’d sat on the side of the road with her head in her hands until it arrived.

Inside the car, she leaned her head back against the seat and closed her eyes. My happy drunkenness was quickly morphing into a flat, depressed feeling.

I gazed out of the window as the car got onto the brief stretch of dual carriageway, but, before we were able to reach any kind of speed, we hit a traffic jam. I sighed and sat back in my seat. The air was filled with the desperate wail of an ambulance then the blue lights of a police car flashed past us in the burgeoning dusk.

The sight tapped into a deep, unhappy place inside me, a place where memories too painful to share were kept. I looked across at my sleepy wife, as if she were a talisman against these feelings. To my surprise, her eyes were open, and she was staring right at me. It was unnerving; like she knew what I had been thinking about.

Picture a little girl waking up in her bedroom with primrose walls on the morning of her tenth birthday.

She still has her toy Simba in her arms, even though she pretends she doesn’t cuddle him at night. It had been a babyish present, but she secretly loves him. In fact, she loves everything about The Lion King, which is why, when her mother suggested it as a theme for the party, she couldn’t hide the excitement. Some of her friends might think it’s a bit silly when you are in Year Five but she doesn’t really care.

She bounds downstairs and sucks in her breath when she sees the transformation happening in the den. Balloons in every shade of green are hanging in cascades along one wall and a huge, painted sticker says ‘HAKUNA MATATA’, over a table that already groans with food.

A woman with a white apron on bustles past her and places a tray of sausage rolls on the table, next to a bowl of animal-shaped chocolate biscuits. The table is covered in some sort of matting stuff so it looks like it is wearing a grass skirt.

There are cupcakes with swirly green icing shaped like leaves, and some have orange snakes curled up on the top, complete with tiny forked tongues. She reaches out a finger and touches one of the tongues to find it is made from thin liquorice strips. Resisting the temptation to eat one, she turns away, not wanting to spoil its perfection. Sometimes, she thinks, the Before is better than the actual event. Sometimes she thinks about this so much that she cries because holidays and Christmas and parties are hardly ever as good as she hopes they’ll be.

The food has been talked about a lot before the party because Lottie from school is bringing her brother with her and he has something wrong with him. They have to be really careful with the food, which doesn’t seem fair when it is her party.

Still, she won’t let that spoil it. It’s going to be the best party ever.

It’s not her fault that everything goes so badly wrong.

ELLIOTT (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

We had a restless night. Anya tossed and turned, and the room felt stiflingly hot. I finally dropped into a deep sleep sometime in the early morning and woke at ten to the sound of gentle rain against the window and a grey sky.

Anya was already up, her side of the bed cold.

My head was throbbing, but I forced myself to pull on running gear. Much as my body and mind resisted it, it seemed as though exercise might help and, anyway, I deserved the punishment. Yawning, I walked through to the kitchen. I was expecting to see her reading the papers on her iPad, her favourite mug steaming next to her. But now I noticed there were none of the usual weekend smells; toast cooked until almost black the way she liked it, and strong coffee that she made as though it was an art form. I wouldn’t have been that bothered if we had instant, was the God’s honest truth. But I guessed I was finally getting used to the good stuff.

The kitchen felt gloomy and I snapped on the main lights. There was a note on the table.

Ell,

I’ve gone over to Mum and Dad’s for the day. I’m still feeling a bit shit and I think I need some of my mum’s TLC. We both know what a terrible patient I am.

Not sure what time I’m back.

X

I didn’t see why she had to go over to Julia and Patrick’s because she was feeling ill. It seemed a bit selfish too, especially as Patrick hadn’t been in the best of health since his heart attack the year before. It was true that she wasn’t a good patient; whoever invented the term ‘man flu’ clearly hadn’t met my wife. But I would have been perfectly happy to make her tea and deliver dry toast, or whatever you’re meant to do, when needed. And if I was being really honest, Julia was more of the ‘pull yourself together’ school of middle-class woman than your cuddly supplier of chicken soup.

The truth was that Anya had form for doing this. Every now and then she would have a couple of days of being a little withdrawn when she would gravitate towards her mum and dad, instead of me. Yes, I know that sounds hurtful, and it was, a little.

But you have to understand what they were like as a family. Tight-knit, fiercely loyal to each other. Once you were ‘in’ you felt special too. It was a golden circle. I’d thought families like this only existed on television until I’d met the Rylands.

I looked at the note again.

The kiss – single – didn’t lessen the uncomfortable sensation that the note was a little cold, by her usual standards. There would usually be a little joke, or a ‘Love YOU’, which was a thing we did.

I thought about the events of the evening before. Her odd mood. The atmosphere when Zoe arrived. Me almost dropping her from my shoulders. Her wanting to go, then being sick. That weird vibe in the Uber …

The fact that some of these memories had hazy edges gave me a prickling feeling of shame. How many pints of cider had I drunk? Five? Six?

Had I ruined our day out? An unpleasant feeling began to creep over my skin. Sometimes, when I drank too much, it made me conscious that ‘Nice Respectable Teacher Elliott’ was a thin veneer over the treacly darkness I feared lay inside me.

I bashed out a text.

No worries. Hope you feel better. Love YOU xxxx

Outside, I turned left and began to run along the coast road. It was raining, that fine rain that deceived you into thinking it didn’t mean business, but which soon drenched you through to the bones. My hair clung to my head and I was breathing like an old man, filled with my usual conviction that everything about this activity was wrong and unnatural.

Drum and bass thumped through my earbuds, which usually spurred me on to run harder, but just felt annoying today. I switched the music off and all I could hear was the roaring of waves hitting the shore, my own rasping breath and the hiss of the odd car going through puddles as it passed me.

The sea was to my left; silvery grey in the rain, lace-edged waves licking at the slick, shining sand. There was a low wall and scrubby grass between the road and the beach down below, yellow signs dotted here and there that warned of unfenced cliff, with a dramatic stick man falling to his death.

This road seemed to go on for ever, past bungalows on the other side that already had a closed-up-for-winter, sad look about them, and the café that still gamely had bright beach towels and deckchairs with ‘witty’ slogans for sale on its covered porch.

After a while I turned right, heading up the hill that led to Petrel Point, where there was a World War Two lookout and a great view.

This was a savage bit of the run, and there was an easier route via a path leading from a car park on the other side, but the view at the top made it worthwhile.

As I made my way up the hill, the usual metamorphosis began to occur. I slowly began to transcend the feeling of hating running and everything connected with running, as my body warmed up and my stride became more fluid.

I’d never run in my life until we moved here. At first, I did it because it seemed like the sort of thing people in their thirties did when they left London and, frankly, I was a bit lost. The endless space around me felt as though it might suffocate me, in a weird way, and I couldn’t get used to everyone looking the same. Why are people so obsessed with having space? Buildings make me feel secure. I’ve never had much of a desire to be the tallest thing on the horizon.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not one of those people who thinks London is the be-all and end-all of civilization. I wouldn’t want to have stayed where I grew up, in a shitty council flat in one of the more depressing bits of north London. It was just a bit more of an adjustment than I’d expected it to be.

Anya grew up in the next town along.

Lathebridge is a genteel place, with its famous Grand Hotel on the front that hosts a small arts festival every year, and its white regency houses along the seafront.

Casterbourne is more crummy arcades and charity shops than cream teas and literary folk, but it was cheap enough for us to buy a small house, with help, and well, there was always the sea. Right now, a silvery band was spreading across the horizon and promising brightness to come. It was one of the things I’d come to love about living here, that the weather could change so quickly. I could see for miles as I reached the top.

I was starting to feel simultaneously better and absolutely knackered, so I looped round past the fort and made my way back down towards home.

I pictured what Anya was probably doing right now. She’d be on the long sofa in their living room – sitting room – probably curled up watching telly and maybe drinking her beloved green tea.

I had an idea; maybe I’d have a shower and just turn up. No one was going to object, were they?

Many, perhaps most, people felt quite differently about their parents-in-law.

When friends made disparaging jokes about their own, bemoaning Christmases and birthdays in their company, I smiled along as though I got it, but really, mine were two of my favourite people in the world.

When I first met Julia and Patrick, I was a little nervous of what they would make of me. I worried that a primary school teacher who came from my sort of background would be a terrible shock to their middle-class sensibilities. All manner of Tobys and Julians and whatever, with Oxbridge degrees and jobs in the City, must have been queuing up.

I had enough of a chip on my shoulder without them even knowing my full story. They still don’t know about my so-called father. Only Anya does.

But the minute I met them, I felt welcome. Sometimes I marvelled at how quickly they’d accepted me. Almost like they had been waiting … and there I was.

Anya told me about her sister, Isabella, who had died of an infection when she was a few days old and whose solo picture – a small, red face in a white blanket – sat among all the ones of the sister who lived. Anya confessed that she felt guilty for having no feelings about this stranger at all and I could understand it, a little. But I think it was one of the reasons they were all so close, as a family. They were grateful for what they had, and maybe conscious that it could be taken away in a few failed breaths.

I was a bit taken aback that Anya was really called Anastasia. Julia only brought that out to wind her up though, as she hated that name. As a tiny girl they had called her ‘Stasi’, but it was a little too East German Torture Squad when written down, so it morphed into Anya, which she used as her official name now.

Patrick was a barrel of man with a hearty laugh and a propensity to see the positive in everything. He came from working-class roots, growing up in Liverpool and going on to work in shipping. Sometimes he made a comment about me and him having things in common, but we didn’t, not really. Very occasionally, you would witness him on the phone dealing with someone difficult and there would be the smallest flash of something else – something sharp-edged that was swaddled by his comfortable home life. He liked to go hunting now and then in Scotland, and I was grateful he never felt the need to ask me along for a father-son-in-law bonding session over dead, furry animals. Not my thing, in any lifetime.

Julia worked in publishing as a literary agent and was lively, fun company. She tended to clasp me in perfumed hugs and say things like, ‘Darling, how is my most favourite son-in-law?’ as though there were competition for the title.

That’s not to say that I hadn’t found her intimidating when I’d first met her. She’d peered at me over her glasses with a slight frown and, for the first half hour in her company, I’d felt a little like I was under a microscope. Then she’d seemed to change, just like that, and was warm and welcoming. I never really knew what it was that turned her around. Maybe she just saw how I felt about her daughter and approved of the sea of love that was on offer.

Anya was their everything. That was clear to anyone who knew them. She was the golden child – the one who survived – and they would do anything to protect her.

Neither of them ever mentioned my own mum. I think they found it hard to know what to say.

I sometimes imagined how it would have gone if my mum had lived long enough to meet them. I pictured Julia, dressed with her usual style, smelling of some sort of subtle perfume, then Mum in those shapeless dresses that were the only things that fit her and leggings, feet overflowing from her shoes like uncooked dough. She would have smelled of smoke because she would have been so nervous about meeting them and she’d have said, ‘Come on, Elliott, don’t give me that look. It’s one of my few pleasures in life and I only have one or two a day.’

I hated myself for thinking like that and I’d put up with any number of worlds-colliding awkward meetings if she was still here. But she had been dead for ten years now, following a massive heart attack, and it was becoming harder and harder to picture her in the world at all, let alone in mine.

My so-called father, well …

I think about the issue of ‘bad blood’ a lot. You would too, in my shoes.

A few nights before we got married, I’d had a huge attack of nerves, entirely based on the idea that Anya wouldn’t want me if she knew everything about me. I’d got royally pissed and, because I am unable to stop myself from making sarcastic quips to big, angry men, ended up with a black eye and a wobbly tooth.

Anya was furious, and I blurted it out. I decided she needed to know that part at least. I told her about the man who was my father by pure biology alone: Mark Little. He got life for beating a man to death who’d been working in a post office Little was trying to rob at the time. I don’t remember any of this. Part of my mum’s disabilities came from him having thrown her down some stone stairs when I was a newborn baby.

He had hepatitis and died in Brixton Prison. And that was the end of him. At least, in the corporeal sense. I try not to think about it, but I find it very hard to forget that fifty per cent of my DNA comes from him.

Anya had held me tightly that night and told me she loved me and that it was going to take a lot more than a ‘gangster dad’ to change that.

She didn’t know everything about me.

I could only test her love so far.

IRENE (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

Irene placed her chunky Nokia next to the sink and stared out at the small rectangle of back garden.

Why wasn’t Michael picking up? It was the third time she had called him this week and it kept going to voicemail. Her son could be very elusive sometimes.

The grass was emerald bright after all the rain and badly in need of a cut. Michael had promised he would be round this week to do it.

When her husband Colin was alive, the garden was kept in an immaculate state. He spent hours out there, in all weathers, digging flowerbeds and tending their small vegetable patch.

Now and then she pulled up a weed or two, but she wasn’t able to do much these days and relied on Michael, for this and other little jobs about the place.

Sighing, she put the kettle on and then, from nowhere, she was sideswiped by a scene.

The two boys, aged maybe ten and five, playing football on that lawn. It wasn’t so tidy then; strewn with plastic toys, footballs, and cricket bats. This wasn’t one specific memory, just an ordinary afternoon that would have played itself out many times. It was so vivid on the canvas of her mind now, she felt as though she could step right back into it.

Liam, her little firecracker, was probably cheating again, running around his red-cheeked brother with a cheeky grin that meant he got away with an awful lot more than he should. Michael, always so concerned with fairness, would have been huffing and puffing with the injustice of it all. Liam wouldn’t have been able to resist stoking the flames, goading his big brother and maybe calling him a mean name. They would be fighting before she had the chance to rush out and prise them apart.

Michael was so much bigger and stronger than his brother, but would never really hurt him, even when he was pushed. But still they fought like cat and dog and at the time it drove her doolally.

She smiled now, remembering it. It felt as though those long days of the boys’ childhood would go on for ever. But no one told you that they would be gone one day.

She was always so tired then. Her supermarket job left her exhausted every day, with an aching back and sore feet. Little time for much beyond making tea and hanging out washing before sitting in front of the television.

Irene wished she could step back into that afternoon, just for one hour. She’d wrap herself in it, bathe in every single second. There would be no, ‘I’m too tired to play’ or, ‘Go and watch telly, boys, I’m busy.’ There would be cake and sweets and as much Coca-Cola as they wanted to drink. She wouldn’t even bother with the diet stuff. She’d play all day if that’s what they wanted.

She swiped at her eyes.

Silly old baggage.

Glancing now, despite herself, at the space next to the cupboard where the cat bowls had lived until recently. Stupid still to be upset about this, when there were so many awful things going on in the world. Michael had brushed it off a bit when she’d told him.

But she couldn’t help the sadness that surged now as she thought about the comfort that old moggy had been.

The kettle seemed to have boiled already. She wasn’t sure she even felt like a cup of tea now, or the sandwich she was planning to make.

Michael was always nagging her to look after herself properly, but it was difficult, when she was on her own.

She hoped he was alright, whatever he was doing.

What was he doing?

He pretended that he was happy, but she knew he wasn’t, not really. How could they be happy, after what had happened, any of them?

Abandoning all thoughts of tea now, Irene went into the sitting room and picked up the photograph that sat on the mantelpiece. Liam, aged eight, all gappy teeth and sparkling eyes. He was always such a beautiful child. When he was a toddler, people used to stop her to comment on his auburn hair and those big, light brown eyes. Once, when she was up in London for the day visiting her mother, a man in the street gave her a card and said he was from a modelling agency that represented children. Modelling!

Irene had been dying to tell Colin about it when she got home, but he hadn’t been excited at all. He said that Liam already ruled the roost and it wouldn’t do him any favours to make him a bighead. She never called the modelling man.

It was a shameful thing she kept locked away inside; the fact that Liam had always been that tiny bit easier to love than his older brother.

Michael was always sick; always complaining about something or another.

And as an adult, he had all his weird theories about things; that there was a secret group of powerful people who controlled everything we did, that the state was constantly monitoring us. Irene couldn’t really keep up and just humoured him when he went into one of his rants.

Liam, though, seemed to have sprung from her womb raring to go at life. He sparkled with some sort of vitality that pulled you in.

He could have been anything, really. She gazed at the picture in her hands. He was still so open then, at primary school. Later, his smile became uncertain and wary. That was when things started to go wrong for him, at secondary school. He was always drawn to the bad lads, the cheeky ones at first, then worse. Something about extreme behaviour in others seemed to draw him like an insect to a lit window, and just like that insect, he would destroy himself, bashing against the glass.

For a minute she allowed herself a fantasy.

Liam was working in some sort of well-paid job in an office. He had a nice car and liked to go on holidays to hot places, where he bought her daft souvenirs. He hadn’t settled down yet, but was getting serious about the latest girlfriend, a nice girl he’d met at work. Michael’s marriage was still going strong and he hadn’t lost his job. Maybe he’d had a promotion and they would celebrate with Prosecco. Everyone was always going on about Prosecco and Irene hadn’t ever tried it. For a moment the fantasy was so real and delicious she could almost hear the sounds of them all around her.

Irene leaned forwards and covered her face with her hands.

It killed Colin. That was for sure. Even though they had their differences – God knows they did – Colin still loved his son. For a time after they got that postcard, their last contact with him, Colin had raged about the ‘lack of consideration’ and the ‘utter thoughtlessness for anyone else’. But when it was evident that Liam really wasn’t coming back, even when Colin was sick … well, it did for him.

All the postcard said was, ‘I have to go away. I’m sorry. Don’t look for me. Lx’.

His passport was missing. He’d been talking for ages about how he wanted to ‘get away’. Ever since he was a little boy, really.

And now it was just her and Michael left.

She went back into the kitchen to check her mobile again.

Where are you, Michael?

ELLIOTT (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

Gloomy at the prospect of going back to work after the weekend, I’d stayed up too late the night before watching a trashy horror film and drinking a few beers.

In the morning, I was feeling scratchy and tired and not at all like a man who’d just had six weeks off.

I found myself thinking about Mum again, which immediately led me down an unwelcome rabbit hole.

Nowadays I would probably be called a child carer or something, but it didn’t really seem like that at the time. I just had to do a bit more on occasion than most kids my age.

Mum had rheumatoid arthritis that used to flare up quite often, leaving her skin grey and her eyes deadened as she crab-walked gingerly around our small flat. She had strong drugs that were supposed to help but she said they made her sick, so she had periods of not taking them. Her weight had always been a problem and I can’t exactly say we had the best diet, so she was what you’d call clinically obese.

We lived in a ground-floor flat that was a stone’s throw from Holloway Road.

‘Like the prison?’ Anya said once, eyes wide.

Like the prison. Our estate was one of those blocks of flats built in the 1930s.

Morningside House was a big rectangle of brown and white buildings with a scummy grass area in the middle. The ‘No ball games’ signs were ignored but so much of the grass was covered in dog shit that it wasn’t exactly a draw anyway. I mostly played football in the playground after school.

There were benefits to living on the ground floor here, in that you never had to use the pissy-smelling stairs. The lifts never worked. But there was much more chance of being broken into, not that we had anything worth stealing. Mum had her bag taken right off our kitchen table when we were in the other room, eating our favourite meal (Findus Crispy Pancakes and oven chips) and watching EastEnders. We never even heard the door being jemmied open.

But that was lucky, for where we lived. There weren’t quite as many stabbings as you hear about now, but there were still a number, plus the odd shooting. More than anything, though, people opted for the good old-fashioned methods; knuckle, boot, and skull. Maybe the odd car jack or iron bar.

On one side of us was a family with three sons who seemed to spend the better part of the day beating seven shades of shit out of each other. Every now and then you’d hear the mum, Marie, shouting that she would ‘burn down the fucking house one day, with youse-all in it’. It sometimes seemed quite a reasonable idea.

Brendan was the father, a hairy-faced bull of a man whose glower alone could send me scuttling into the house if I happened to come across him outside the flats. The three sons – Frank, Kieran, and Bobby – were all a little older than me but the youngest, Bobby, had enough of a sphere of influence at school for me to avoid ever passing on stuff I saw or heard from their household. Like the time I saw Marie kick him up the backside at the front door because he couldn’t open it fast enough. All it took was one look from him, anger and humiliation glittering hard in his eyes, for me to know to keep my mouth shut.

When Mum’s pain got too bad, she would sometimes go to bed and not get up for a day or two. She took Valium – had been on it for years – from the days when GPs thought nothing of prescribing it for every period of stress or mild sleeplessness. She wasn’t a huge drinker but she knew that if she combined it with alcohol then it would knock her out. That was all she wanted. I don’t think she even liked the taste of alcohol very much.

My neighbour on the other side was an elderly Scottish woman called Mrs McAllister, known as Mrs Mack. She had neat, grey curls and bright eyes behind thick glasses. Her mouth seemed to transmit disapproval without the need for words.

There had always been a polite distance between her and Mum. Mum said she thought Mrs Mack disapproved of us, once speculating it was because of Mum’s brown skin. Or maybe it was because she knew about my father. When she said that it gave me a weird feeling in my stomach. Like there was a thread that tied me to him, still. That I was somehow the same as him.

The whole thing with Mrs Mack started on one of those days when Mum had taken to bed. I came in from school and could tell straight away that she was home, but that something was wrong. There was a stillness, a kind of hesitation in the atmosphere, like the house was waiting for me.

Her bedroom door was closed. I popped my head in and could see the mound of her in the bed, smell the sweetish smell of her bedroom, a mix of smoke, the air freshener on the side, and a uric tang from the damp patch on the ceiling.

Afternoon light was bleeding through the thin orange curtains, highlighting crumpled tissues on the floor next to the bed and an empty can of beer.

This was the sort of detail Anya would never have been able to understand. A gulf of distance so large would open up between her and what she thought my mum was, that I wouldn’t be able to face trying to explain. So, there was only so much I told her about it.

As for the other stuff …

If I could just keep her away from the darkness, you see, and in the light where she belonged, maybe we really had a chance long term. Maybe I would stop feeling that she was an incredible gift I only had on loan.

That day I had been desperate to speak to Mum after school. We’d been given a letter in History about a trip to the Imperial War Museum and it was going to cost parents ten pounds. Museums weren’t free then, so I’d never been, and being a bit obsessed with old war movies, had always wanted to go and see all the tanks and guns. Mum was on benefits and I knew that ten pounds was a lot, but it seemed reasonable to me that we could spare this when it was for school. Especially if Mum could afford a can of Stella when it suited her.

I wandered into the living room and booted a cushion covered in a greasy sort of green taffeta across the room with as much savagery as I could muster. It knocked down a dusty cactus that sat in a knitted pot-cover on the table by Mum’s chair. I glared at it for a moment, then prowled into the kitchen.

Rooting in the fridge, I saw Mum hadn’t got to the shops like she’d said she would. I knew that I’d be trying to find enough change in her purse for some chips again. I was always starving then, right in the middle of a pre-pubescent growth spurt. My knees were like knots in pieces of string, my elongated thigh muscles giving me almost constant pain. I found the crust of a loaf, and slathered on the last of the peanut butter, before folding the whole thing into my mouth at once. It was never enough. Hunger felt like something living inside me, a growling beast that nagged and heckled.

I wandered out to the front of the flats, not knowing what I wanted to do, but feeling like the whole place was wrapping itself round me and squeezing air from my lungs.

Mrs Mack had a series of little pots outside her house, along with a ceramic toadstool and a Smurf holding a fishing rod. I looked down at it, with its annoying blue face, and before I knew what I was doing, I’d slammed my toe into it so hard it went clattering down the length of the path running in front of the houses. My toe hurt through my trainer and, before I could run off, her front door was open, and she was peering out at me.

‘What was that?’ she said. I stared back at her, too numb to speak.

She regarded me through her horn-rimmed glasses like I was a specimen in a jar and said, ‘What are you doing, lurking out there anyway?’

‘Not lurking,’ I managed to grunt. Then, ‘Going to get chips.’ I didn’t know why I added that. It was the first thing that came into my head. I didn’t even have the money for any chips.

She looked at me for a few moments more. ‘I’ve made a cottage pie,’ she said. ‘Do you like cottage pie?’

I shrugged. It wasn’t so much confusion about my feelings on cottage pie (I was hazy on exactly what it was). Guilt at what I’d done, coupled with the horror that she would notice it any second, was stoppering my throat like a wad of cotton wool. My cheeks throbbed with heat and I stared down at my shuffling feet, willing time to move on so I was anywhere but here.

‘Come on,’ she said, opening the door up wider. ‘You’re like a string bean. You need something better than chips inside you.’

I hesitated for a moment, calculating how I might be able to hide the evidence of my Smurf-destruction, and reasoned it would be easier to keep her distracted for a while.

I went into her hallway and the smell of cooking meat immediately flooded my mouth with longing. I had to swallow to stop myself drooling like a dog.

It turned out that I liked cottage pie very much indeed, along with pudding thrillingly steamed in a tin and served with thick custard for afters. I liked the biscuit tin with the picture of the Scottish Highlands on the cover (I only knew that because she told me) and I liked the proper Ribena, gloopy and sweet, that she had instead of Value blackcurrant squash we sometimes had.

I don’t know why that day was different to the others.

But she should never have invited me in.

IRENE (#u46b24a53-b552-5625-ba96-a036c6ddda74)

Irene’s hands trembled as she checked inside her handbag for her purse. It would involve a bus ride to get to Michael’s flat and she got anxious about travelling anywhere on her own lately. But she needed to know what was going on.

She thought about ringing Linda. She still had her number.

The shameful truth was that she was a little frightened of Linda, with her screechy laugh and her sharp tongue. No wonder she and Michael hadn’t lasted, although Irene wasn’t naïve enough to think that her eldest son had been blameless in the marriage.

It was drizzly outside, and Irene felt a strong desire to turn straight back as she began to walk down the street. Everything felt so loud after being on her own for the last couple of weeks – roaring traffic and the jarring sound of human voices.

When the boys were little, and scared about something, she used to say to them, ‘Just put one foot in front of the other,’ and that’s what she did now, making her way to the bus stop and joining a small queue of people there. A young woman with a pram was jiggling it backwards and forwards in an attempt to distract a baby that was emitting hiccupy sounds of misery. The woman’s eyes had lilac smudges beneath them and her long red hair was greasy at the roots. Irene gave her a sympathetic smile and the woman looked surprised for a moment, almost as though she felt caught out in her thoughts, then she rewarded Irene with a returned smile.

‘How old?’ Irene said, peering into the pram and seeing a baby so tiny it still bore the wrinkled, shocked look of the newly hatched.

‘Three weeks,’ said the woman quietly. Irene looked up to see her eyes were now brimming with tears.

She patted the hand that was holding the handle of the pram and said, ‘It will get so much easier. I promise you that, sweetheart,’ and the woman nodded her thanks and lowered her eyes.

Climbing onto the bus, Irene felt a stab of guilt at what she had said. If only sleepless nights were the hardest bit of parenting. She hadn’t expected to be worrying herself sick in the wee small hours about her children when it had been thirty-four years since she had given birth.

When, twenty minutes later, she arrived at the street where Michael was renting the attic room, she looked up and down for his car. But there was no sign of it.

That didn’t mean anything in itself, she told herself, as she got to the terraced house where he lived. He might just be out.

Her stomach turned over as she pictured him lying on an unmade bed with an empty bottle of pills next to him. It would be so unlike him to do something like that though, wouldn’t it? He had never been the one to take drugs. Not after his brother.

But life hadn’t been especially kind to him lately. Breaking up with Linda had really cut him up, however much he’d claimed he was ‘better off without her’.

Irene was glad they didn’t have any children of their own, even though she would have loved grandchildren. It would have made the break-up even harder on everyone.

Gathering herself, Irene went to the front door and located the buzzer for the top flat. There was no name, just ‘Top flat’. It wasn’t the sort of place anyone would put down roots. When Michael got made redundant from the print company he’d worked with for many years, he’d been given a small pay-out, which was keeping him afloat. When she’d asked him about getting a new job, he told his mother he was ‘assessing his options’. He was forty, but that wasn’t very old these days, was it? Forty felt like nothing much now, not to Irene, anyway.

There was no reply from the top flat. Irene pressed the buzzer again and then got a shock as the front door was suddenly flung open. A young black man with a woolly hat and a beard, a cigarette halfway to his mouth, seemed as surprised to see her and for a moment they both stared at each other.

‘You going in?’ he said after a moment and Irene blurted out, ‘Do you know Michael? He lives in the top flat?’

The man scrunched his brow for a minute then recognition dawned. ‘That fat ginger bloke?’

Irene bristled, but forced herself to remain polite.

‘He’s my son,’ she said. It was answer enough for the other man who avoided her direct gaze then and said, ‘Not for a while. Ask Rowan on the second floor. She usually knows what’s going on.’

Irene thanked him stiffly and, as he bounded down the steps behind her with an air of gratitude to be getting away, she came into the cramped hallway. There were two bicycles to one side, and on the other an ornate and old-fashioned wooden sideboard with a speckled mirror. It was covered in a sea of post and fast-food flyers and, looking around awkwardly, Irene began to rifle through, separating the letters from the flyers.

She quickly found one, then two letters addressed to Michael, but on closer inspection, they looked like junk mail. She put them back.

The steps were steep, and covered with a treacherously rucked carpet, so she climbed slowly but was still a little out of breath when she got to the top floor. She took a moment to collect herself, then rapped on the door to Michael’s flat. She waited, then did it again, but there was no response.

‘Michael? Love?’ she called out, hating how quivery she sounded. Nothing happened.

Reluctantly, she walked back down the stairs and found herself hesitating on the second floor.

She felt silly knocking on doors and speaking to strangers about her business, but, in for a penny, in for a pound, she guessed.

Some very strange sounds were emanating from inside the flat there. It sounded like someone was giving birth, having an argument and playing the drums at the same time.

Irene steeled herself once again and knocked gently on the door. Nothing happened for a moment and so she did it again with more confidence this time. The music, if that’s what you could call it, abruptly stopped.

The door opened, and a very overweight woman peered blearily out at Irene. She was somewhere in middle age, with hair in pale-coloured dreadlocks held back by a red scarf. Her skin bore the look of a lifelong smoker and there was a sweetish smell that even Irene recognized wafting out of the flat. It no doubt explained the slightly unfocused look in her eyes.

‘Can I help you, darling?’ she said in a surprisingly high-pitched, girlish voice.

‘I’m looking for my son, Michael,’ said Irene. Suddenly she found she was close to tears. Her knees were hurting, and she was gasping for a hot drink. All she wanted was for someone to say, ‘There’s nothing to worry about. Michael’s fine.’

The woman looked at her and something Irene couldn’t place passed across her face. Maybe something had happened between her and Michael. Irene couldn’t help herself immediately hoping he had used protection and then being disgusted with herself for even thinking like this.

‘I haven’t seen him in two weeks,’ said the woman, frowning now. ‘He hasn’t been answering any of my messages.’

‘Oh.’ Irene felt herself sagging and leaned a hand against the doorframe.

She hadn’t wanted it to be anything other than a silly old bat with too much time on her hands worrying about nothing. But this strange person now looked as worried as Irene felt.

‘Look, you’d better come in,’ said the other woman.

ELLIOTT (#ulink_82ea06be-182f-502c-aa49-382eef3274ae)

It was probably thinking about all that childhood stuff earlier, but when I got to the school playground, my eyes seemed to fix on Tyler Bennett straight away.

Tyler was one of those kids it was very hard to like, even though I wasn’t meant to say that. He was a three-foot-high block of truculence, with a sulky face and the ability to be ever the wronged party in a dispute.

He was standing now just inside the school gates with a mutinous expression, clearly waiting for someone. The bell was just about to go so I wandered over to him. He greeted me with the sort of look dogs give when they suspect someone is about to take their bone away.

‘Alright, Tyler?’ I said. ‘What are you doing? Bell’s about to go.’

He ignored me and peered out of the gate, little brow so scrunched his eyes almost disappeared.

‘Are you waiting for something?’ The bell rang out clearly.

‘C’mon, mate, time to go in.’ I touched his shoulder and he reacted as though he had been hit, pulling his arm away violently.

‘Woah!’ I said, taking a step back. At that exact moment, as if conjured up from nowhere, a huge, bullet-headed man appeared at the gate, brandishing Tyler’s school bag and breathing heavily.

‘What are you doing?’ said the man, presumably young Tyler’s progenitor.

‘I’m not doing anything,’ I said reasonably, because I’d met plenty of parents like this one. ‘I was just telling Tyler the bell’s gone.’

‘Did you touch him just then?’

I stared at the man for a second. ‘I tapped him lightly on the shoulder in a friendly way,’ I said, my face entirely straight. ‘Because the bell had gone.’

‘That true, Ty?’

Tyler shrugged. After an agonizing moment’s pause he added, ‘S’pose,’ and I was ridiculously grateful to the little sod for not making this worse just for sport.

‘Right,’ said the man. ‘Well, he was waiting for me, wasn’t he?’ He moved closer to his son, as though making a point, before handing the bag to Tyler, whose gaze was flitting between us in wide-eyed fascination. The man’s eyes narrowed further and he said, ‘Wait, do I know you?’

‘I’m a teacher at your son’s school, so I imagine you may recognize me,’ I said, giving the man a broad smile. His type hated that. You can really wrong-foot aggressive people with a bit of sunshine. I should have stopped there, but my annoying weekend, a residual irritation with Anya for abandoning me, and the toxic swill of my thoughts earlier all conspired against me. Before I turned away, I found myself muttering, ‘You have an excellent day, now.’

The man’s cheeks darkened. It was unnerving to see aggression painted even more boldly on his face.

‘You’ve got a real attitude, do you know that?’ he said, his voice a low rumble that got me in the gut, just as it was intended to.

‘I can assure you I haven’t, Mr, uh …’ My brain flailed for Tyler’s surname before it came to me. ‘Mr Bennett. I’m just trying to do my job and get your son in for the start of the new term.’

The man was frowning now, staring hard at my face, and then a malicious grin broke out over his.

‘I know who you are,’ he said.

I formed my mouth into a pleasant smile. ‘Well, as I said, I work here.’

‘Nah,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘Not from here.’

Did he? I couldn’t think how. His accent was a little more London than the local one, but I still didn’t know him.

‘I don’t think so, Mr Bennett,’ I said. He made a snorting sound, then muttered something under his breath. All I caught was, ‘for you …’

‘I beg your pardon?’ I said.

Bennett did a sort of ‘nya nya’ thing, then shook his head and walked off without saying anything else to his son. Tyler’s thumb had snuck into his mouth during this exchange, something I hadn’t noticed him do before. I attempted a friendly smile.

‘Come on, buddy,’ I said. ‘I’m no happier than you are that the holidays are over. Let’s go in.’

As I got to the building I turned, and my heart seemed to jolt out of its place. Bennett was standing across the road, staring right at me.

ELLIOTT (#ulink_9e14e792-37dd-5332-accd-412ab88a4c87)

I felt on edge all morning after that encounter. I’d dealt with aggressive parents before, as I said, but there was something about him that had really chilled me. There had been the hint of a smile there, like he’d been contemplating actions further down the line that he would enjoy very much, and I wouldn’t. And why did he think he knew me?

At breaktime I looked out for Clare, Tyler’s class teacher. I wanted to know whether she had ever been on the other end of the Tyler paterfamilias’s displeasure.

She wasn’t about – maybe on playground duty. I went to make myself a coffee. There was a sink full of dirty mugs. With a sigh I cleaned one as best I could with hot water and something that had once been a dish scourer, then decided to be the bigger person and do the lot. I was up to my elbows in suds when Zoe appeared next to me.

‘You’re really good at that,’ she said in an earnest-sounding voice. ‘Would you like to be our Sink Monitor this week?’

I mouthed, ‘Piss off,’ at her and threw a bit of foam. She laughed and flicked it away.

‘So …’ I said after a moment. I grinned and waggled my eyebrows.

Her cheeks flushed.

‘What?’ she said.

‘Tell me all about Tabitha then,’ I said, nudging her in the side. She looked down, failing to hide the way her eyes instantly lit up.

‘What do you want to know exactly?’ she said, getting out one of the clean cups and reaching into her handbag for one of her horrible green teabags that tasted of garden mulch.

‘Well, I don’t know,’ I said. ‘You’ve kept so quiet about it, I don’t know anything. I feel like …’ I bit off the end of my sentence.

‘What?’ she said, serious now. It was my turn to blush.

‘I dunno,’ I said. ‘It just seems weird not to tell me.’ I stopped, then said quietly, ‘That …’

‘That I’m a lesbian?’ she said at the top of her voice. Several heads shot up from the various battered chairs around the room. Mary Martinson, who had been a teaching assistant here for about a thousand years as far as I could tell, was staring with her mouth actually open from the sofa in the middle of the room, a plastic bowl of salad in her lap.

I didn’t really know what to do. I hadn’t intended to force Zoe to out herself like that in the middle of the staffroom. I made myself a cup of coffee I no longer wanted. I could hear her breathing heavily next to me as she reached for the packet of Value ginger nuts that some kindly soul had left for all to eat.

I must have looked as awkward as I felt. Zoe touched my arm. I looked at her and she said, ‘Why would I?’ in a quiet voice.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘It’s none of my business. But I thought it might just have come up in conversation, like, I dunno, I talk about Anya.’

Zoe nodded and gestured for me to come over to a quieter bit of the room with her. There were only a couple of minutes left of break and I had things to do, but this felt important, so I followed, with my unwanted coffee.

‘I don’t know why I did that just now,’ she said, taking a sip of her tea. She flashed me a quick, vulnerable smile. ‘I’m still kind of finding my way, in all honesty.’ I waited, and she continued. ‘I was with a bloke for years. Bit of an arsehole. One day I’ll get shitfaced and tell you all about it.’ She puffed out her cheeks and sighed, then continued, in an even quieter voice. ‘I didn’t expect to fall in love with a woman, but it seems I have.’

When she put down her mug I gave her a little mock punch on the arm.

‘Sensible decision,’ I said. ‘Women are lovely. Blokes are hairy, horrible things.’ Her loud laugh turned heads again.

‘I knew I could rely on you for a deep, philosophical conversation,’ she said. ‘Thanks for helping me work through this complex issue.’

‘Anytime, doll,’ I said in my best old-time American accent.

She laughed and then her expression turned serious again.

‘And you?’ she said. ‘Everything okay with you guys?’

I looked back at her, puzzled and not a little discomfited.

‘Me and Anya, you mean?’ I said. ‘Why?’

She looked flustered and gave a slightly forced laugh. ‘Oh, nothing, nothing,’ she said. ‘Just with leaving early and all.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘She was just under the weather, no biggie.’

‘Right,’ she said. ‘Right,’ then, with a bright smile, ‘Anyway, things to do, kids to corral!’

I didn’t manage to see Clare until afternoon break because I was on lunchtime playground duty.

I watched Tyler for a bit at lunchtime. He was part of a football game that mainly involved screaming at the top of his lungs and denigrating the prowess of his team mates. I found myself wondering again about his home life so, when I saw Clare in the staffroom, I asked if I could have a quick word.

Clare was a small, serious woman in her forties. She had a couple of kids and a husband who, as far as I could gather, did as little as he could in their upbringing. She often seemed to be sighing at her mobile phone and generally had a careworn sort of air about her.

We sat down on the sofa. She peeled the lid of a tub of yoghurt and began to spoon the contents into her mouth in small, neat movements.

‘So,’ I said, ‘tell me about Tyler Bennett’s dad.’

She made a face and then said, ‘What do you want to know?’

I told her what happened that morning at the school gates. She sighed and put down her yoghurt and spoon.

‘Well, he’s an ex-soldier,’ she said. ‘His name’s Lee. Emily, Tyler’s mum, died of breast cancer.’

‘Shit,’ I said. ‘I didn’t know.’

‘Hmm.’ She fixed me with a serious look, and her next sentence came out in a rush. ‘I probably shouldn’t pass this on,’ she said, ‘but he’s an ex-offender. I think there were some issues with the mother after he came back from Iraq. Possibly PTSD or something like that. But whatever went on, they had got over their differences when she got sick.’

‘Right,’ I said thoughtfully.

‘I do find him a bit prickly,’ she went on. ‘But I think he’s just trying to cope on his own, so I generally cut him, and the boy, a bit of extra slack. Can’t be easy for them.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Can’t be easy at all.’

As I made my way back to the classroom I thought about poor little Tyler and the big tough man who was trying to be both mum and dad in that sad household.

I felt sorry for him. But I didn’t like the sound of ‘ex-offender’ and the implication of domestic violence.

It was a little too close to home.

IRENE (#ulink_8e208e8c-2c41-5b8a-ae24-21c1a235b5f9)

There was a ginger cat lying across the middle of the carpet. It wore a grumpy expression and gave a silent, shivery mewl as she stepped over it and looked for somewhere to sit down.

A quite astonishingly ugly dog – a pug, perhaps; Irene didn’t really ‘do’ dogs – wandered over and made snuffling noises while pawing at her foot. It was almost spherical, neck wrinkles spilling onto its fat little body.

‘Come on, Elvis,’ said the woman, and scooped the animal up, ‘you need to be on good behaviour for our visitor.’

The room was dimly lit, some kind of Turkish rug slung over the window. It didn’t fit, and daylight streamed from the sides. Otherwise the room was lit by a series of lamps. There was a sofa so low to the ground, Irene worried about getting back out of it again, covered in a pale orange sheet and piled with cushions. Most of them had colourful prints that Irene thought of as Moroccan.

On various surfaces were remnants of half-melted puddles of candles. Along with the sweet drug scent, Irene could smell garlic and some sort of musky perfume from the woman.

‘Can I get you anything to drink? You look a bit peaky,’ said the woman, in that girlish voice. The dog panted in her arms, ham-like tongue lolling, giving it an even more unappealing look.

Irene carefully lowered herself onto the sofa, which gave even more than she’d expected. She tried to cover up her discomfort by smoothing her skirt over her knees and fixing the woman with a dignified stare. She wanted to decline the offer, but she really could do with a cup of tea. For a moment she worried that the woman might only have strange druggie tea, then said, ‘Yes please. Do you have tea?’

‘Only PG Tips, I’m afraid,’ said the woman and Irene felt relief flooding her veins.

‘Then yes please,’ she said.

The kitchen was behind a beaded curtain and Irene could see the woman (Rowan, was it?) collecting cups from a tree mug as the kettle boiled.

When she came back into the room, she was also carrying a few misshapen biscuits on a plate, along with Irene’s drink. Irene took the slightly chipped mug, which seemed clean enough, and eyed the strange biscuits now on the coffee table, which was otherwise covered in copies of a magazine called Spirit and Destiny and an almost full ashtray.

‘Have a biscuit,’ said Rowan, taking one herself and biting into it with a loud crunch. ‘They’re made from hemp and flax seeds. Really good for you.’

Hemp definitely sounded druggie. And this person looked very much like the sort who wouldn’t wash her hands after touching an animal. Irene declined, even though her stomach was rumbling, and took a sip of her tea. It was strong and milky, just how she liked it, and she could feel it restoring her almost straight away.

‘I’m Rowan,’ said the woman. She was looking at Irene in that way people do when you get to a certain age; as if you’re daft. The dog settled onto her lap and regarded Irene with the occasional nasal wheeze, like it had a head cold.

‘Yes, I know,’ said Irene and was taken aback to see the bright eagerness on Rowan’s face now.

‘Oh, did he talk about me then?’ she said. ‘Michael?’

‘Sorry, no,’ Irene said quickly. She hadn’t intended this to be cruel but the other woman’s mouth turned down at the sides.

Oh Michael, she thought. This isn’t your sort of person. She wondered if that was why he went away. Had he got in too deep with this woman?

‘He’s talked about you a lot,’ said Rowan, blowing on her tea. Hers was in one of those impractical teacups with a huge circumference and a tiny handle. Steam curled up from it and she seemed to cradle it more for comfort than from a desire to drink. ‘Very warmly.’

Irene couldn’t help the rush of pleasure at hearing these words. It wasn’t something she would have assumed at all. Sometimes she thought she was an annoyance to her eldest son. She didn’t trust herself to speak and instead nodded and took another sip of the tea.

Rowan watched her carefully. Irene got the strange feeling that the other woman knew exactly what she was thinking. Michael wouldn’t have liked that. He was always private.

‘Yes,’ she continued, ‘he said that you’re the strongest woman he has ever known.’

Irene put the mug onto the table too briskly, so that the tea almost slopped out of the top. She mashed her trembling hands together in her lap. Impossible to hold onto any reserve now.

‘Did he really?’ she managed, emotion coagulating in her voice.

Rowan leaned forward and clasped her own hands together, as though praying. The dog slid off her lap and went into the kitchen, where Irene could hear it lustily slurping from a water bowl.

‘He really did.’ She paused. ‘Look,’ she said and gave a deep, wheezy breath inwards, ‘I know all about … well, Liam going missing.’

‘Oh,’ said Irene. ‘That’s not quite what …’ She picked up the cup again for something to do, even though she no longer wanted the tea. It felt strange to say he was ‘missing’ but wasn’t that word painfully on the money in so many ways? There was a long, strained silence. Then she said, ‘Where is Michael, Rowan? Where has he gone?’

‘Well, that’s the thing,’ said Rowan. ‘I think he’s gone looking for him.’

‘What makes you say that?’ This came out too sharply, but Irene couldn’t help it. It touched on the same painful well of hope that allowed her to get out of bed each morning. ‘Has he heard from him?’

Rowan blushed now, unexpectedly, and stared down at her cup. It was very bizarre. She didn’t seem like a woman easily given to embarrassment. Then she looked up and there was something in her eyes that Irene felt herself drawing away from.

‘What is it?’ she said tightly.

‘It came out wrong just now … about looking for him.’

Irene was beginning to feel exhausted from this visit. It was an emotional rollercoaster. Now she was getting irritated with this woman and her riddles.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean,’ said Rowan with excruciating patience, ‘that I think he’s trying to find out exactly what happened to him all those years ago.’

All those years ago … As if it were a hundred. As if it were a thousand. As if it didn’t matter any more.

‘Mrs Copeland,’ said Rowan. ‘You know Michael believes Liam is dead, don’t you?’

ELLIOTT (#ulink_83a1373d-ac34-50a4-8118-a2592c315def)

I was cycling home when it happened.

I’d naïvely thought, moving from London, that it would be easy to cycle here. I’m not exactly sure what planet I was on, thinking city drivers were the aggressive ones, but the way they hammered round the narrow lanes here at all hours had come as a bit of a shock. Still, we only had one car and Anya needed to drive to the next station along for the better train connection to London, where she worked, so I cycled in every day.

I was on the road that led from the top end of town when I heard the sound of a car behind me. It didn’t overtake as I’d expected it to where the road got wider. I turned to look behind me, but the driver had on a baseball cap and sunglasses; plus, they were sort of hunkered down in their seat. The car was a dark SUV – black or dark blue, I couldn’t really tell.

An uneasy feeling rippled up my neck and I pedalled harder, knowing that the turning to lead me off this road was coming up soon. The car just seemed to purr malevolently along behind me for ages. I thought about that movie Duel, where the guy is terrorized by a never-revealed maniac in a huge truck. The road was coming closer and I pedalled even harder. I was almost there when I heard the roar of the engine behind me – right there. Awash with shock, I wobbled and then toppled sideways, crashing onto the narrow pavement. The car zoomed away with an angry roar around the corner before I got a chance to see the number plate.

‘Shit!’ I said. Pain sliced through my knee, which was caught under the bent frame of the bike. My hands blazed with a burning, stinging pain. Looking down, I saw a constellation of tiny stones and beads of blood on both my palms. The front wheel of my bike was all bent from hitting the pavement, and I’d jarred my back.

‘Bastard, bastard,’ I said with feeling and hobbled towards home, having to hold the front half of the bike off the ground all the way.

I was surprised and grateful to find that Anya was there when I got back. She didn’t normally get in until about seven.

I’d taken the bike down the alley to the backyard and I opened the kitchen door to find her standing at the stove, stirring something in a pan. When she saw me, her face went from pleasure to concern in half a beat.

‘Did something happen?’ she said, wiping her hands and coming over to me.

‘Fell off my bike,’ I said. She made a sympathetic noise and took my backpack from me. ‘Well, I say that, but I was essentially forced off it by some tosser who thought I was Dennis Weaver.’

‘Oh no!’ she said, and it made me smile, despite the fact that most parts of my body were hurting right now. One of the things about being married that had never stopped thrilling me was the near-telepathy over cultural references.

She came over and turned my palms round, then gently kissed the grazes. It hurt but I managed not to wince.

Anya helped me wash the grit out, as I told her all about what happened, and then she gently applied antiseptic. Her brow was sweetly scrunched, as if she was doing highly skilled surgery.

My right knee ended up with a large plaster across it, which was bound to come off straight away, but I let her apply it anyway.

‘So,’ she said, as she put away the first aid kit and washed her hands. ‘Did you get a look at the guy’s face? The one in the car?’

‘No, not really,’ I said wearily. ‘He had on a baseball cap and sunglasses. Anyway, it all happened …’

I paused.

‘What?’ said Anya, turning back to me.

‘It’s probably nothing,’ I said. ‘Just that I had an encounter with a parent today and he was a bit aggressive.’ I filled her in on what had happened.

‘Do you think it was him who knocked you off your bike?’ she said. Her back was to me and she turned on the gas under the pan again, before starting to stir. ‘You really didn’t see him? Can you describe him at all?’

I thought about it for a moment, touched by how seriously she was taking this.

‘No,’ I said after a few moments. ‘I can’t believe he’d do that. I mean, it really was nothing.’ I paused again. ‘It’s just that …’

‘What?’

I blew air out through my mouth. ‘I don’t know, Anya, he just said this really strange thing about knowing me. I swear I’ve never spoken to the man before.’

‘Knowing you?’