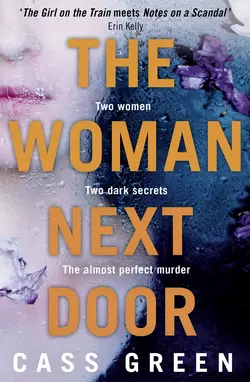

The Woman Next Door: A dark and twisty psychological thriller

Cass Green

A No.1 e-book bestseller, perfect for fans of Ruth Ware, Shari Lapena and Clare Mackintosh.Two suburban women. Two dark secrets. The almost perfect murder.Everybody needs good neighbours…Melissa and Hester have lived next door to each other for years. When Melissa’s daughter was younger, Hester was almost like a grandmother to her. But recently they haven’t been so close.Hester has plans to change all that. It’s obvious to her that despite Melissa’s outwardly glamorous and successful life, she needs Hester’s help.But taking help from Hester might not be such a good idea for a woman with as many secrets as Melissa…

THE WOMAN NEXT DOOR

CASS GREEN

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

This is a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Killer Reads

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Caroline Green 2016

Caroline Green asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © JULY 2016 ISBN: 9780008203559

Version 2016-12-11

Table of Contents

Cover (#ud2ee3eff-1f4c-5d0c-ac43-b8e237f22a47)

Title Page (#uc1c4535f-ff97-567e-8a2c-d34bde3ab6f8)

Copyright (#u8ccc7a32-8f71-5275-a7b0-524a105d2af1)

Part One (#u52b1a575-655a-57f0-a768-6da776bb0de2)

Hester (#u80975ffb-f23d-563d-84af-4316cac9b2af)

Melissa (#ub1e4a085-50b6-58e5-b942-71c48d02b2a2)

Hester (#u7981c99c-094b-5e95-9264-a7351118876b)

Melissa (#ue2fa224a-1751-5fae-98a4-4a6b45471215)

Hester (#u1242b8b6-a38e-53ce-93f2-ac49f3560607)

Melissa (#u85532459-0ad0-5845-83f2-3099d5f1024d)

Hester (#u71551f59-721b-52ff-991c-518841a60d59)

Melissa (#u31fee3a5-d59a-561f-94fd-e6854cfdf3db)

Hester (#ua95ab920-f7a5-568f-aeb0-6b5e80174d69)

Melissa (#u6e75d94e-a59e-5da2-9f47-2bb522faebed)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Melissa (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Five Months laterMELISSA (#litres_trial_promo)

Hester (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

HESTER (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

Cough, sniff, sigh.

Sniff, sigh, cough.

And so it goes on.

Mary, at the next terminal, is a veritable one-person orchestra of bodily sounds. It must be something to do with her size. She’s constantly spilling out of herself, like there’s someone bigger trapped inside.

She’s not the only person I’m finding distracting today. The old chap opposite, Jacky, I think he’s called, apparently believes an Adult Education course on Essential Computer Skills – in a library – is a suitable place to eat his lunchtime sandwiches. I can clearly hear the click of his jaw as he masticates bread, cheese, and pickle. The reason I know so much about the sandwich is because he is scattering a confetti of the contents over the keyboard.

You would think that his advanced years would have brought a little more wisdom about this sort of thing. He is possibly like many of the elderly and doesn’t really give a stuff anymore what others think. I quite envy that.

I clear my throat and turn my attention back to the screen, where I ‘scroll’ down the pages of the Mail Online. It’s all depressing: stories about immigration; teenagers heading off to join ISIS; and politicians telling the usual fibs.

But I enjoy knowing the correct word for what I am doing. I am now a woman who ‘scrolls’, ‘downloads’, and ‘surfs the web’, among other things.

Oh yes, Terry, you didn’t think I had it in me, did you?

The point is: I will no longer feel inadequate when I see people tapping away at computers, as though they belong to yet another club I am excluded from. I can do this now, too. Although heaven knows whether I really shall bother.

I look around the library, glancing at the big clock to see how much of the session is left. A couple of teenagers across the way have managed to cover a whole table with their belongings and, like the old man, are openly eating lunch. One of them has some sort of fast food and the fatty, savoury smell tickles my nose and makes my tummy give a little growl. I would never eat anything like that, but breakfast does seem a long time ago.

I think about lunch – a ham sandwich perhaps, or an omelette – and picture my kitchen. Bertie will be a big scruffy comma in his bed, gently snoring. The clock will tick with a dull thunk, which has always been a little too loud. Or maybe there just aren’t enough other noises to balance it out?

This sort of thinking will get me nowhere. I can feel one of my funks coming on and I must fight it. Maybe I will bake a cake when I get home. Something complicated, which involves skill. It could be my own small celebration for reaching the last lesson of the course?

I certainly deserve a pat on the back for sticking with it. It’s fair to say I had a shaky start, mainly because I didn’t enjoy the patronizing attitude of the tutor, Alice, an Antipodean who looks about twelve yet always reeks of cigarette smoke. She has a slightly seedy appearance; her small fingers are adorned with chipped, grubby-looking polish and her dark blonde hair has been put into those horrible dreadlocks. Why on earth a white girl would do that with her hair is anyone’s guess. They’re piled on top of her head every which way giving her the appearance of a young nicotine-stained Medusa. She speaks in a cheerful lilting way that is a little too heavy on the question marks. And she never seems to wear a bra so her small bosom jiggles about like a pair of tennis balls under the vest tops she favours.

She was patient enough when I struggled at the beginning. I’ll give her that.

It didn’t come to me easily at first. I had a tendency to lift the mouse off the table while trying to master it. When I explained, once, that I was trying to move the cursor ‘up’, she actually said, ‘Aww, bless?’ Bliss.

I was stunned! You would think I was a child or a little old lady instead of a healthy woman of just 62. I said, ‘Young woman, I suggest you show a bit of respect.’ That told her. Since then, she still does the annoying laughing thing, but her eyes are always sliding off somewhere other than my face.

No, I’m not sorry this is coming to an end. I only took the course to get myself out of the house, and I am not going to be making friends with any of this lot.

Most of them are much older than me, and the woman nearest my own age – who goes by the name ‘Binnie’ – isn’t really my class of person. She catches my eye now, then looks down again. No doubt she took it personally when I turned down her suggestion to ‘go for a cuppa’ after the class on the first week. I said, ‘I’m afraid I don’t really drink tea,’ which was a bit of a white lie, because I do in fact drink it a great deal!

But she is one of those women who positively exudes her maternal bounty like an aura. I’ve heard her going on about ‘my daughter’ and ‘my newest grandson’ to anyone who will listen. She even, if you can believe this, has a tote bag with ‘World’s Best Grandma’ and a giant picture of a gurning infant on it. She is one of those women entirely defined by the workings of her womb. I know that, if I had taken her up on her offer, the ‘cuppas’ would barely be on the table before she would be saying, ‘So Hester do you have children?’

Why do women ask this question so readily? It’s not as though we talk about the intimate workings of our bodies in any other context. It’s a very personal question and I have never really found a comfortable way to field it. I want to reply, ‘That’s none of your business’, but I’m aware that would be a little rude.

No, she is not really my sort of person. My mind drifts back to my baking plan and I muse on what sort I could make. A nice lemon drizzle, or a rich fruitcake perhaps. But the gloomy feeling I have been trying to hold off is descending now, falling around my shoulders like a dank shroud.

I know what will happen if I embark on a baking project. I will have a couple of pieces of whatever it will be and then the rest will just sit there, wasted, drying out, until I throw it into the wheelie bin. I can’t give any of it to Bertie. It’s very bad for dogs to have sweet things. They can get diabetes and heart disease just like we can.

If I was like Binnie over there, I expect the cake would last five minutes before sticky-fingered little ones were cramming pieces into their mouths like hungry birds. It really is so unfair. All of it.

‘Are you all right, Hester?’ Hister.

I look up. Alice is peering directly into my face, for once, with an expression of sugary sympathy. Glancing around I become aware that several of them are looking at me now. Binnie’s eyes are wide, and Jackie has paused mid-munch of his sandwich, his bottom lip glistening with grease and hanging slightly open.

So many eyes. All on me.

‘Yes, why on earth do you ask?’ I bark a short laugh but it sounds entirely unnatural.

Alice hesitates and then actually puts her grubby little paw on my shoulder. I look at it until she takes it away. She clears her throat.

Blushing (rather prettily) she says, ‘It’s just that you seemed to be, um, muttering something? I wondered who you were talking to?’

My tummy seems to flip over and my breath catches so I have to cover it up by pretending to cough. I can feel the heat creeping up my throat and flooding my cheeks.

Oh dear God. I have finally started talking to myself? What am I doing?

‘Hester?’ she says again.

I stiffen my spine and meet her gaze full on so that she is then the one who is blushing. I gather my handbag from where it is resting next to the computer monitor and rise to my feet.

‘I am quite well, thank you,’ I say. ‘I think I’m going to go home now.’

‘Oh, okay?’ she says, in that annoying singsong voice. ‘It’s just, we’re all planning to go the pub? You’re very welcome to join us?’

I can’t think of anything I’d like to do less. I can just picture it. Alice, all full of fake bonhomie; the oldies getting squiffy and promising loudly (and falsely) to keep in touch.

No. I’d rather stare at my uneaten cake and find out what’s on Radio 4.

Yet it stings.

It’s the, ‘You’re very welcome to join us’, thing. It wasn’t, ‘Oh no, Hester, you have to come to the pub! It wouldn’t be the same without you!’ Ha! It’s like I’m an afterthought. And now my silly eyes blur and kaleidoscope Alice’s face in front of me.

But I still have my pride. I have achieved what I set out to do. I have learned how to use a computer. I am finished here.

‘No thank you,’ I say and then the lie just slides out of my mouth. ‘My daughter and grandchild are visiting later. I have things to do today.’

‘Oh?’ Alice seems to chew the word and then the bright smile is plastered over her face once again. ‘Well, I hope you have a lovely time with them? It’s been great meeting you?’

‘Yes, I’m sure,’ I say, before walking quickly away towards the exit.

I catch Binnie’s eye, and I can see her look of surprise.

I expect Terry is laughing in his grave.

MELISSA (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

As the stylist cocks the mirror to show her the back of her hair, Melissa can’t help picturing a shaven-headed teenager in a Moscow bedsit.

‘Looking gorgeous, don’t you think?’ says Susie.

Melissa nods and forces a tight smile. They say the best hair comes from Russia, and this type of blonde is worth every penny of the £400. If only she could get rid of the lurid Gulag imagery.

‘Those’ll see you right for another six weeks or so,’ says Susie, with a kindly squeeze of her shoulders.

‘Great, thanks Susie.’

But it’s hard to feign the enthusiasm she knows is expected. The whirr and blast of hairdryers and the tinny thud of the background music have anaesthetized her into a kind of stupor. She can’t even quite remember what she and Susie had been talking about during the endless hours she has been sitting in this chair. She feels somehow bonded to it.

Her reluctance to get up prompts Susie to speak quietly into her ear.

‘Why don’t you finish your tea before you go?’ she says in her soft Geordie accent. ‘Boss likes to get people out the door, if you know what I mean, but you’re all right for a bit longer. My eleven o’clock hasn’t even arrived yet.’

Melissa murmurs her gratitude as Susie bustles away and reaches for the delicate china teacup cooling next to the jumble of brushes, scissors, and tongs in front of her.

The cloth pyramid of camomile tea has a greasy shine to it and the liquid is tepid and almost slimy as it slips down her throat, which feels scratchy. She coughs experimentally and begins to fret. It would be the worst time to come down with something. She could picture herself croaking miserably at people over the music of the party. There’s some zinc and vitamin C at home. She’ll dose herself up with them later.

Looking back at her reflection, she runs a hand through her hair, turning her head this way and that. She takes care not to snag the tiny plugs woven into her own thin, expensively dyed tresses, which now hang in glossy waves the colour of butterscotch, wishing yet again that she didn’t always do this. Wonder about the provenance of the hair, that is.

Surely there’s nothing wrong with it? It’s no different from the Bio Gel that adorn her fingers in a colour she is told is ‘French Nude’, although Melissa thinks her fingertips look a bit creepy. Android, almost. She wonders what percentage of her is now artificial.

But the extensions feel different. She pictures some poor pretty girl losing the only asset she has so that a rich woman thousands of miles away can enjoy the weight of it on her shoulders. All too easy to picture the grubby transaction involved in selling your own hair.

It is as she is musing gloomily on this that she feels a strange prickle of unease, like there has been a ripple in the atmosphere, a tiny, fizzing depth charge deep in the primeval part of her brain.

She frowns and looks around.

Someone is watching her. Melissa turns her head sharply to look at the main window. It is slightly steamed up and the displays of flowers – ugly spiky things that she privately detests but which are presumably deemed stylish – obscure the view a little but she can see a swatch of High Street outside.

People drift or march past the window. It’s a perfectly ordinary day in North London.

Life bustles on, oblivious to Melissa. No one is looking in at her.

Of course they aren’t. What was she expecting? Who was she expecting?

She gets up crisply and walks to the desk to pay, her stomach still roiling queasily from the shock of thinking she was being watched. Her back aches and her bottom is stiff from hours of sitting.

Susie seems to materialize from nowhere and, taking care not to damage her newly faked nails, Melissa rummages for her purse and then opens the small wooden box that has been discreetly placed in front of her, containing the bill.

Melissa knew that this morning wouldn’t come cheap, but still, the cost of hair extensions and styling, manicure, pedicure, and eyebrow threading, at almost £600, gives her a thrill of transgressive pleasure.

She hopes Mark will choke on his coffee, as she pushes her credit card across the counter to Susie and looks for a twenty to leave as a tip. If he’s going to behave like one of those husbands, then she will be one of those wives.

Outside on the High Street it feels like the contrast button on an old television has been turned up too high. Everything is too bright; nauseatingly colourful. Melissa feels the sharp pinch of a headache beginning in her forehead. She finds her sunglasses and pushes them onto her face a little clumsily, eyes greedy for the shade. A branch of Boots is just over the road and Melissa decides to buy some water and paracetamol before setting off home. Maybe she can head this thing off at the pass so she can enjoy the party later. The caterers will be almost finished now and all that needs to be done is to oversee the Ocado delivery, which is bringing the majority of the booze. It’s a bit late, but they let her down yesterday, citing some sort of freezer catastrophe. She hopes the champagne will have enough time to chill for this evening.

It is as she is crossing over to Boots that Melissa feels the crawling sensation again, like fingertips skittering across her skin. She is certain now that it isn’t in her head. She read once that it’s something to do with peripheral vision.

Someone is definitely watching her.

Melissa’s heart begins to thud uncomfortably hard as she whips around in a full circle, eyes narrowed behind her dark lenses. Someone has just been swallowed up by the doors of Superdrug but she didn’t see them clearly. The High Street is busy – full of normal people, gazing into phone screens, yanking irritable children along, or, in the case of the few old people dotted about, ambling painstakingly with shoppers or small decrepit dogs. No one is staring at Melissa.

Goosebumps scatter across her arms and she shivers, even though the air is close and heavy. A car alarm shrieks nearby and Melissa flinches. The air feels soupy, with traffic fumes mingling with the cigarette smoke wafting from a doorway, where a young woman’s head is bent over her mobile, apparently having a furious conversation at low volume.

At the far end of the High Street, near the library and fire station, Melissa can see a figure who looks familiar. It takes a minute to realize it’s her next-door neighbour, Hester. She is a fussy, annoying little woman who was constantly in Melissa’s face when she first moved into the street. Hester was far too interested in how Melissa was bringing up Tilly, and although she had occasionally helped with babysitting, she was more trouble than she was worth. Melissa managed to slip free of her attention and the last contact they’d had was earlier this year. Melissa couldn’t remember the details because it happened bang in the middle of the Sam thing. Something to do with recycling, or parking.

Melissa is in no mood to see Hester just now. She has enough to worry about. Even though it is only a ten-minute walk home from here, she hurries over to the taxi rank and climbs into the first available car, catching the appreciative look tossed her way by the driver. As she leans forward to give the address, she feels warmed by the attention and thinks about what he sees: a good-looking, well-groomed woman of means. Someone he could only ever admire from a distance. And if he’d known her back then? She doubts he would have allowed her in his taxi.

She is unrecognizable now.

Surely.

Melissa settles back in the seat as the car pulls away and tries to think calming thoughts. No one is watching her. No one is following her.

No one knows.

Her mobile trills, making her jump a little and she inwardly curses herself for her jumpiness.

‘Babes, it’s me.’ Saskia’s husky voice pours into her ear like warm oil.

Despite having been educated at an elite girls’ boarding school, and growing up riding ponies and skiing, Saskia’s diction wouldn’t be out of place at a gathering of Pearly Kings and Queens.

Her Mockney affectation sometimes irritates Melissa, but she is also one of the warmest people she has ever met. She laughs like a navvy and can infect Melissa with a dose of humour when she is otherwise unable to feel it. Her loyalty during the Sam episode will never be forgotten by Melissa. Saskia knows all too well what it is like to be cheated on, and the father of her teenage son was sent packing a few years previously.

‘What’s up?’ she says, stifling a yawn. The idea of lying down on the scuffed, smelly seat of the car and taking a nap feels worryingly tempting.

‘Not much,’ says Saskia. ‘Just wondered if you need any last-minute help? I know you have caterers in but I’m about if you need me.’

‘That’s really sweet, Sass, but I think I’m all sorted.’

There’s a brief silence before Saskia speaks again. ‘And has there been any change of heart …?’

Melissa sighs. ‘Nope. He claims it’s “totally unavoidable”. Can you believe him?’

Saskia groans and then Melissa hears the suck and pop of her cigarette.

‘Fuck Mark,’ says Saskia. ‘I’m going to be there to make sure it’s the best damned party ever. Nathe is coming along and he can be your barman or something.’

Melissa smiles. ‘I can always rely on you.’

‘Love ya.’ Saskia hangs up.

The car has been stuck in a jam for the last few minutes and Melissa cranes now to see what is going on.

‘Some sort of hold-up, is there?’ she says to the driver, whose eyes are now framed in the rear-view mirror as he looks back at her.

‘There’s a lorry that was fannying around unloading something at the back of Asda, but it looks like we’re moving now. In a hurry?’

Melissa nods and then turns to the window. She has no interest in chatting through the rest of this journey. As the taxi hums back into movement again, the driver doesn’t attempt any further conversation.

They turn down leafy streets where the houses are set back from the road. Several of the houses have original stone sculptures on the gateposts, and when Tilly was little she loved what she called the ‘stone piggies’ that stand sentry at Hester’s gate.

Melissa swears under her breath as she sees the other woman walking just ahead. Hester has managed to get back before her. Not prepared to risk being stuck with her on the doorstep, Melissa switches on a smile for the driver.

‘Could I ask you to pull over just here?’ she says and she sees his rectangular gaze, harder now.

‘Sure,’ he says.

She spends some time pretending to look for money, until she is sure Hester is safely inside.

HESTER (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

I am starting to wonder whether I did the right thing in leaving the library so hastily.

The afternoon has trickled by in a succession of mindless television programmes, which flicker and squawk away in the background. I’m not watching any of them really, but I’m loth to turn them off. They provide a buffer against the silence.

I keep picturing them all in the pub, getting steadily more inebriated. Faces will be flushed now with alcohol, bulbous elderly noses spidered with red veins, mouths open and revealing yellowing dentures as they laugh and laugh and laugh. At me. I’m sure they will be having a right old time of it. ‘Silly, funny old Hester,’ they’ll say. ‘Isn’t she the strange one?’

Damn them all.

I know full well what Terry would have made of this.

He was always telling me I was too quick to act, too rash. He’d get that look, the one that seemed to suggest he was a man who required a superhuman level of forbearance.

‘Hester, you need to give people a chance,’ he’d whine. ‘You’re so quick to judge.’

What he really meant was, ‘Hester, you should let people walk all over you.’

I never anticipated how much he would still haunt me, fifteen years after he died. He seems to be there, yacking away in my head, almost all the time.

My mouth feels stale and I go to pick up my cup of tea but discover that it is quite cold. I must have been sitting here even longer than I had realized. This happens sometimes. I sit down to watch television, and before I know it, it’s time to put Bertie out and I don’t even remember what I’ve been watching. I gulp it down anyway, wincing a little at the way it coats my mouth with a milky film.

It is then that I hear the purring of a vehicle stopping outside. I get to my feet and go to the bay window that looks out onto the street. An Ocado van has just pulled up outside, directly below my window. The driver, a balding coloured man of indeterminate middle age, hefts himself out of the front and noisily opens the doors on the side of the van. I part a gap in my nets, noticing the sickly greyness that tells me it’s time I washed them again, and stand to the side of the window just so. From this position I can clearly see the contents of the large plastic crates as they are disgorged from the back.

For some reason Melissa has her delivery arrive without carrier bags and it means that I can see exactly what she has ordered from week to week. She has no qualms, it seems, about showing the world all the intimate items, the tampons and deodorants, the panty liners and cotton buds, but I suppose we are all different.

I can tell a lot about the domestic cycles of the house from the shopping. I know when Tilly is home from school because there are slabs of Diet Coca-Cola in the mix, or when Mark is away because the expensive bottled beers he favours are missing. When Melissa is on her own, the shopping contains a lot of organic, low-calorie ready meals. Heaven knows why she needs to diet. Melissa has a wonderful figure and, if anything, could do with a little more meat on her bones.

But this time as I watch the crates emerging from the back of the van it becomes apparent that this is no ordinary delivery.

There’s always rather a lot of alcohol but today I see boxes of what looks like champagne. And is that … Pimm’s?

More crates are yanked from the van with a scraping sound and now I see forests of French sticks in one. Another is positively crammed with expensive soft fruits such as mangoes and bright strawberries. The colours glow, jewel-like, in this grey afternoon and fill me with a dull ache of longing somewhere around my sternum.

Glancing at my own fruit bowl, I see it contains one banana, stippled and overripe, and a forlorn tangerine that has lost its gloss and looks dry to the touch. I sigh and turn back to the window.

The driver closes the doors of the vehicle with a tinny clang.

And then he turns and looks directly at me, a smirk wrapping around his face.

I pull back from the window so fast I crash painfully into the television. It’s an old one and, for a second, the blonde grinning woman on the screen fragments. There is a zigzagging of the image, an angry hiss of static, before the picture rights itself again.

Staggering back into the shadows, rubbing my bruised hip, I reel from the hot scald of humiliation for the second time in a day.

What was he trying to say with that look? That he has seen me before, watching, and finds it odd. I squeeze my hands into fists so tightly my nails bite the soft flesh of my palms.

I walk into the kitchen on trembling legs and slump into a chair, trying to catch my galloping breath.

I have nothing whatsoever to be embarrassed about, yet I seem to ache with shame. Pressing my hand to my cheek I can feel that I am flushed and feverish.

How dare that van driver judge me?

How could someone like him possibly understand someone like me?

It’s not that I’m spying on Melissa. It’s just a way of keeping in touch with what’s going on in her life.

I sometimes find it hard to make sense of where it all went so wrong.

When that little family first moved in next door, I noticed how she carried Tilly, as though the baby were a grenade. Melissa often looked exhausted but she was still beautiful, still wonderfully turned out. A rush of tender motherly emotion would wash over me as I watched her awkwardly rock the tiny bundle in her arms. I knew I could help her if she would let me.

And she did. For a time. In fact, there was a period when I became quite indispensable to her, if you want the truth.

I was always babysitting at late notice for Tilly. Over time I believe she came to think of me as sort of an aunt, although I couldn’t get ‘Auntie Hester’ to stick as a monica, or whatever that expression is.

There was a time when I fancied I might be invited on holiday with them, even though I was never convinced Mark liked me. Melissa had been complaining about the fact that Tilly would never join the children’s holiday clubs when they went to their various resorts. Always classy places, like Mark Warner, or Sandals. Although I imagine these days, with his television career, they go to fancier venues still.

Anyway, all I did was hint that an extra pair of hands could really help but Melissa seemed not to understand. I didn’t want to push it.

Now Tilly is away at boarding school and, when she comes home, she smiles politely and answers my questions, but there is a sense that she is keen to get away. I see it in her eyes. How can things have changed so much?

She’s certainly not that same girl who liked to make biscuits with me in my kitchen. I think of her small arms moving like pistons inside my big mixing bowl, flour dusting her hair, and it’s hard to connect the picture with that near-adult. But there’s no point dwelling on it. Time moves on.

But I don’t see why Melissa and I can’t still be friends, just because Tilly has grown up. She began to drift away as soon as Tilly started primary school, locally.

First, she was never in when I called round to ask her for coffee. At least, I don’t think she was there. Once, I thought I saw movement at an upstairs window but I’m sure I must have imagined this.

Why on earth would Melissa hide from me of all people?

A few months slipped by, then half a year. We always seemed to be coming in and out at different times. Missing each other.

But I think it was the business with the bins that really caused the rift.

You see there’s an alleyway running alongside my house where the bins, for both Melissa’s house and my own, are kept. I have always put the bins out on a Monday morning and our little ‘system’ (as I liked to think of it) was that she would put them back that evening.

When she left them out in the road until Wednesday morning the first couple of times, I thought nothing of it. But then it seemed to become a habit. And that wasn’t the only thing. It’s very clear that one set of bins is for number 140, mine, and another for 142, hers. But she started to put things in randomly, as though it didn’t matter which bin belonged to whom. I’d go to recycle my read copies of the ’Mail and find it was filled with wine bottles and online shopping packaging. It really was quite irritating. I’m very fond of Melissa, but I suppose this began to really bother me on top of everything else.

At first I’d gently remove the items and put them back into her own bin, hoping that it would get the message across. But it carried on until one day when my entire bin was filled with packaging from Habitat. (It contained a duvet. Duck down. 9.5 tog.) I really felt I should say something. So I went round there. I was perfectly polite and friendly. But I think I may have caught her on a bad day.

She is usually immaculate, as I said, from her shining crown of blonde hair to her prettily painted toenails. That day though, she had on some sort of tracksuit thing and her hair was scraped back into an untidy ponytail. Her eyes looked dull and oddly vacant. It was like no one was there, if that makes sense. Although my heart went out to her (really, I longed to give her a hug and tell her it would be okay) I was determined to say my piece.

But it all seemed to go wrong. She listened without commenting and then simply closed the door in my face. I felt as though I had been slapped. I did something quite out of character at home. I found a dusty old bottle of sherry at the back of my cupboard and had a small glass to calm my nerves. The cloying thickness almost made me sick. God knows how long it had been there. But the whole thing really cut me to the quick.

Such a silly business to fall out over; things have never really been the same since.

I couldn’t think of a reason to go round. I would try to make conversation from the front garden (I’d watch for the car and then make sure I was in position) but it has never really been the same.

I so wish that we could be friends again.

Bertie, who always senses when I am distressed, huffs to his feet now. I reach down and scratch the wiry grey hair behind his ears in what I think of as his ‘special spot’. He shudders with bliss and his eyes roll back in his head.

My boy.

I’ve read that King Charles spaniels can live to the age of fifteen. Bertie is only thirteen but I can tell he has lost his lustre a bit lately. He’s not the only one.

‘Shall Mummy get your dinner?’ I say wearily.

His tail jerks and circles like a wonky propeller. I get up. I pour some of his special food into his bowl and place it down on his mat. He starts to eat it with enthusiasm but then loses interest. Sighing again, I open the back door. The kitchen suddenly feels very small.

For one awful moment I think I am going to go quite mad. I’m so very sick of being lonely.

And then, as I stand there, looking out at my overgrown lawn, I have the beginnings of a wonderful idea.

Melissa must be having a party, with all that alcohol arriving. There will be such a lot to do. It would take me no time to knock up some scones or a Victoria sponge. She never was much of a baker. She once told me that my lemon drizzle cake was like ‘sex on a plate’. I was a bit embarrassed by this, to be honest, but I appreciated that she meant it in a complimentary way. And didn’t I have an urge to do some baking earlier? Maybe it was an omen. Perhaps I was meant to leave the library the way I did.

For all I know, Melissa has been waiting for an excuse to patch things up between us. This could be the perfect opportunity to mend bridges.

I’m not even offended that I haven’t been invited. I couldn’t expect her to, when relations were so strained between us.

‘Right, Bertie,’ I say, reaching for my apron, which hangs on a hook on the kitchen door. ‘Mummy had better get busy.’

I’m the older, more mature, person. It’s time to put things right.

MELISSA (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

The diazepam doesn’t seem to be working. She took it more than two hours ago but she’s still waiting for the blunting sensation to take effect, for all the hard angles in her mind to soften and blur. The sensation of unease she experienced at the hairdressers has clung to her like a succubus.

She keeps telling herself there’s no reason to feel anxious.

Nothing has happened.

All is well.

Melissa stands on the landing and rotates the tips of her fingers into the centre of her forehead. This supposedly wards off headaches, according to Saskia, who picked it up from some alternative therapist. She swears by it, but Melissa remains unconvinced as she gouges hard, rhythmic circles into her skin.

Tilly emerges from her bedroom dressed in pink and green pyjamas that strain across her hips. Her hair is matted on one side and her face is puffy with sleep. She has inherited the distinctive russet brown curls Melissa used to have. It’s a lovely colour and Melissa wishes she herself had been able to keep it.

In every other respect Tilly is her father’s daughter, from the heavyset shoulders and square, blunt-toed feet, to the almost bovine brown eyes, fringed with enviable lashes. Melissa thinks she carries about a stone more than she should, but she is still a very attractive girl when she makes an effort.

Today she has violet smudges under her eyes. Since the GCSE exams finished, she lives in onesies or pyjamas and thick socks and spends her days padding from fridge to bedroom, where she lies like a large tousled cat, tapping at her iPad and dozing.

But today is a party in her honour and she clearly hasn’t been through the shower yet, judging by the cocktail of teenage sweat, stale coffee, and the sickly watermelon-flavoured lip balm she favours rising from her. Her iPad sits lightly on one hand like a prosthesis. Tilly blinks, slowly, as though she has emerged from a subterranean lair.

Mother and daughter eye each other and Tilly attempts an exploratory smile, which morphs into a yawn that smells of sleep. Melissa’s face remains impassive. She doesn’t want to shout at Tilly and yet it would be so very easy to do right now.

‘When are you planning to get ready?’ she says crisply. ‘This is your party, after all.’ Downstairs there is a metallic clatter as the caterers begin to pack away some of their equipment. One of them laughs loudly and says, ‘You wish!’ A song from Melissa’s youth – ‘Babooshka’ by Kate Bush – wails tinnily from the radio on the windowsill. She has already asked them to turn the radio down once. Thank God they are almost done.

Tilly’s eyes are already being dragged towards the abyss of her iPad, where Walter White is paused, staring out at red, baked earth. She has been on a Breaking Bad marathon for the last two days, only pausing to sleep and eat.

‘Soon, Mum. I promise.’

Tilly disappears back into her bedroom.

It’s the gentleness in her voice that has prompted Melissa’s eyes to prickle and ache, unexpectedly. As if Melissa were being humoured. She has made it quite plain that she doesn’t really want a party. But she will obviously play along, just to keep her mother happy. In her own time.

She’d always imagined, in the days when all her tiny daughter did was cry, shit, and feed, that the compensations would come when she was older; when she was a proper person, they would do all the things she never did with her own mother. Melissa pictured her and Tilly cosy on a sofa, bonding over 1980s movies like The Breakfast Club and Pretty in Pink. Or mother and daughter puffing out their cheeks and complaining good-naturedly about aching feet as they sat down to a good lunch, surrounded by bags from a morning spent shopping.

But none of these fantasies had ever quite come off.

Tilly didn’t like what she called ‘girly’ films, preferring instead to watch violent science fiction thrillers with her father. And the few times Melissa had coaxed her daughter into the West End to shop, they had ended up falling-out and glowering at each other over uneaten salads in Fenwick’s café.

Melissa thought it would be nice to celebrate the end of the GCSEs, that was all. It seemed like the kind of thing a family like them – secure, middle class, loving – should be doing.

Secure.

Middle class.

Loving?

That’s what she’d thought.

Mark is a doctor, specializing in IVF, who had made a decent living by combining private work with his NHS practice at the Whittington Hospital. But two years ago he had taken part in a BBC documentary set in the private clinic in Bloomsbury where he worked two days a week.

The programme was called The Baby Business and it became something of a hit. Every week, thousands of people would discuss the ins and outs of various couples’ reproductive failures and successes (more of the former than the latter) over their morning coffees or at bus stops.

There was Janine and Paul, a young man who had almost died from testicular cancer who longed now to be a father; the Hewlett twins, a pair of sisters who caused a spike in egg donation numbers for a few weeks in late 2013; and a stubbornly un-telegenic, spiky-mannered couple called Trudy and Gary. Every week they bickered with each other on camera and argued with the medical advice given. They were media catnip and Trudy’s lugubrious expression even prompted an internet meme in which her face was overlaid by a bleating goat. When their third attempt at IVF failed, the atmosphere shifted and she became Tragic Trudy.

But Mark was the real star of the show. His salt-and-pepper hair, and warm twinkly manner as he delivered both good and bad news, proved to be a ratings winner. Before long he began to receive invitations onto various daytime television sofas.

The BBC commissioned a follow-up series of TBB, as they called it. At home Mark privately called it BBB, for Babies Bring Bucks. All of this had been welcome in terms of money, but for Melissa, having a spotlight shone into her life, a spotlight that could throw every long-abandoned and grubby corner into the sharpest relief, it felt like a particularly cruel cosmic joke.

Mark couldn’t understand why Melissa wouldn’t accompany him to the various events he was invited to with increasing frequency. She’d always managed to find an excuse. It wasn’t her thing. Or she felt like a night in. No one wanted her there, after all. They’d only be talking shop.

And it was true that she had no interest in this world. Television people bored her. Their natural privilege was a balm that lubricated their way through life, so they never seemed to snag and falter. They had no idea, the Emmas and the Sachas and the Benedicts, of what the world was like for most of the population, despite the desire to entertain and document them.

But her avoidance of the limelight had blown up in her face in more than one way. Firstly, Mark claimed that her unwillingness to enjoy his success helped push him into the arms of Sam. Mark said that the affair was over, really, before it started.

‘It meant nothing. It was a terrible mistake. I’m so sorry. I wouldn’t hurt you for the world.’

As though it wasn’t far too late to say this.

As a rule, Melissa worked hard to keep her younger self hidden; the small, hard Matryoshka doll that lurked beneath lacquered layers. Mark’s grovelling words, which seemed to drip so easily from his lying lips, finally forced her out of hiding.

Melissa was as shocked as he was when she hit him, and the yellowish patina of his bruised cheek was noticed by Make-Up when he next turned up for filming.

But Melissa was being carried on a tide now, one that washed her to Sam’s flat in a mansion block in Swiss Cottage. The younger woman’s eyes rounded almost comically and she gave a small gasp, like a hiss of gas from a balloon, as Melissa stepped out of the shadows and stood in front of her.

Melissa spoke to her in a measured, calm voice. Afterwards, Sam scurried away on her long, coltish legs, scarlet-cheeked and breathing heavily. She’d left the programme soon after.

They never spoke of it again but the gears of their marriage seemed to turn with more friction now; small irritations Melissa had previously overlooked grated more than ever.

Mark suggested a meal out one evening – ‘to talk’. They went to the new restaurant that had opened down the road, which had just appeared in the Observer magazine. It was as they stepped towards the white canopy of The Bay, between miniature bay trees in square metal pots, that a photograph was snapped – or stolen – as Melissa thought of it. She hadn’t even noticed a flash.

But a week later, a friend of Saskia’s had spotted the Society pages piece in Hello! magazine. Melissa, smiling, in her black sheath dress and heels, making an effort, and ‘Handsome Baby Doc Mark’, solicitously touching the small of his wife’s back as they entered, ‘the exciting new eatery that has opened close to the glamorous couple’s Dartmouth Park home.’

Saskia had been surprised by Melissa’s muted reaction to the piece, and then sympathetic about the sudden onset of food poisoning that sent Melissa rushing to the downstairs toilet, where she vomited and shook so hard that she could feel her teeth rattling in her skull.

It was just one picture. It meant nothing.

That’s what she told herself in the coming weeks, and she almost began to believe it.

But lately Melissa can’t seem to shake the feeling that her whole world is simply a snow globe that could tip over and shatter into a million lethal pieces with the slightest push of a fingertip.

Glancing out of the window on the landing now, Melissa sees that the sky seems to be slung low, like a heavy white blanket. The light has a sickly, oppressive edge to it and the house feels full of shadows. Maybe this headache is a warning that a thunderstorm is coming. It feels as though even the weather is out to sabotage the day.

Giving herself a mental shake, Melissa walks into the kitchen and feels marginally better at the industry there. The caterers have been busy all morning and the fridge is heaving with platters and dishes of colourful, tastefully arranged food, but every surface is clean and shining, ready for the guests to arrive a little later.

Ocado have been and gone; the flowers have been delivered – a tall arrangement of lilies that perfectly offsets the newly hung green and gold wallpaper. Really, everything is looking perfect.

Melissa sweeps her hair back from her shoulders, taking care not to ruin its smooth line. Now she only has to slip into the dress and sandals she bought for today and then it won’t be long until the first guests arrive.

Finally, she allows herself to feel a ripple of pleasurable anticipation. The house looks great, she looks great, and it will be the kind of day that makes all her hard work worthwhile.

Today is about her, Melissa.

And Tilly. Of course.

The doorbell chimes and Melissa walks down the hallway to open the door, wondering if there are any deliveries she has forgotten about.

‘Ah,’ she sighs. ‘Hello.’

Hester – stiff helmet hair, horrible pink blouse, and brown slacks – smiles shyly up at her. She’s a small, scurrying sort of a woman who reminds Melissa of a squirrel.

Melissa hates squirrels.

The sight of Hester now causes a claustrophobic sensation of disappointment to crowd in, as if she is literally stealing her air. It takes her brain a second or two to see that the other woman appears to be holding a tray of scones, of all things.

‘What can I do for you?’ she says, eyeing them suspiciously, her smile tight but bright.

Something shifts in Hester’s expression and she lowers the tray a little before her prim lips twitch.

‘It’s good to see you, Melissa,’ she says. ‘Well, I can see you’re having a function of some kind and I know you must be very busy. I was at a loose end today and I’ve been doing some baking. I made rather too many scones. I wondered if you might find a use for them?’

Irritation spikes in Melissa’s chest.

Function?

It’s such a blatant lie that she had accidentally ‘made too many scones’. There seem to be a thousand of the bloody things on that tray.

Scones are definitely not going to sit alongside polenta with figs, red onion and goat’s cheese, or the balsamic-glazed pecans with rosemary and sea salt.

‘It’s okay, thank you, Hester,’ says Melissa, smiling warmly to stifle the strange urge to scream. ‘I’m quite covered for food. I have caterers, you see.’

The polite refusal seems to pierce the other woman. Her face slackens around the jaw and her shoulders sag. She’s always been passive-aggressive, Melissa thinks. It’s why she has tried to keep her distance in recent times.

Melissa takes a deep, steadying breath. Did people have to be so oversensitive? She knows what she’s going to have to say. Mark thinks it’s funny to call her the Ice Queen, but she doesn’t actually want to go around actively upsetting people. She comforts herself with the thought that Hester will probably be too intimidated to accept the invitation. It isn’t really her sort of party, after all; her with her scones and her 1970s ‘do’.

‘But I’m very grateful for the offer, Hester,’ she continues. ‘And, um …’ The words gather, oversized and chewy, in her mouth. ‘Would you like to drop by at some point later? It’s nothing fancy,’ she adds in a hurry, ‘just a small gathering. I’m sure you’ve got better things to …’

‘I’d love to!’ Hester’s response rings out, a little too shrill, before Melissa has even finished her sentence. Her face and neck flush and blotch with pleasure.

Melissa regards her wearily. ‘Marvellous,’ she says, forcing her lips into a semblance of a smile. ‘Any time from five then. I’ve still got rather a lot to do, so you’ll have to forgive me if I don’t chat. See you later.’ She closes the door before Hester has time to make any more demands.

Bloody Hester.

At least she’d been forced to take her fucking scones back with her.

HESTER (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

Although Melissa said any time after five, I didn’t want to appear too keen so I have waited until almost twenty past to go round. I lift the heavy doorknocker in the shape of a lion’s head. With its tarnished gold snout and blank eyes, it seems to assess me unfavourably as I rap once, and then again with more confidence than I am feeling.

My heart is beating a little too fast and my armpits prickle uncomfortably in the flowered dress that was chosen after much painful wardrobe deliberation. It was dispiriting to note that everything I own, although clean and pressed, is a little worn and soft to the touch from wear. This is the best I could do. They will have to take me as they find me.

Strains of music and loud male laughter seep from the house but no one answers. Just for a second, I get the wildest, oddest, sensation that they aren’t going to let me in. I will stand here, ignored, until I am forced to take my bottle of Blossom Hill Merlot home. I don’t even like wine, and this cost more than five pounds.

But a vague flash of colour through the stippled glass of the door sort of coagulates into a shape and the door opens.

Tilly blinks, then frowns. Finally, she smiles.

‘Hester? What are you doing here?’

I swallow and smile brightly, hoping she won’t be able to see how much her surprise has stung me. Has she forgotten how close we were, too?

‘I’m coming to the party, of course,’ I say, tilting my chin. ‘Your mother invited me this afternoon.’

Her cheeks flush as she remembers her manners. She’s all smiles now, beckoning me inside.

‘Go on through and get yourself a drink,’ she says. ‘Ma’s out there holding court, I expect.’ She turns to the stairs and her legs scissor away and above me at speed. She is wearing a pair of short dungarees over black tights, which hardly seem like party clothes to me.

I make my way inside. The hallway smells just lovely and I can see that Melissa has new wallpaper since I was last invited round. It’s a bit of a funny colour, the sort of dark green you used only to see in institutions, but I expect it cost a bomb. I expect they all favour this overpriced decor round here.

We live in a part of London that I’ve heard described as ‘on the wrong side of the North Circular’. It’s always suited me fine, but when the train line was extended into the City, all the yuppies started moving in with their lattes and their big cars and their complicated prams. Now I’d be lucky to afford a garden shed in the area.

But it’s just as close and unpleasant in here as in my boring old hallway, that’s for sure. The lilies on the hall table are already nodding drowsily and speckling mustard-coloured pollen. It’s a devil to get out of clothes, that stuff, so I give the table a wide berth as I make my way towards the kitchen at the back of the house. I pass the sitting room and see a couple of people standing in there smiling and talking animatedly.

I haven’t really been that nervous until now but my tummy begins to positively thunder with butterflies as I step down into the packed kitchen.

Sensations assail me and I almost stumble. Conversation and laughter billow around me like clouds of smoke. There’s a repetitive tsst-tsst musical beat coming from somewhere. And peacock flashes of colour everywhere. Summer frocks cling to bodies in pink, scarlet, turquoise, black. High-heeled, impossible sandals and painted toes. Lipsticked mouths sipping at drinks or parting in wide smiles.

It’s so hot in here.

I lift my shoulder and subtly drop my head to check that I don’t smell of the perspiration that is prickling my armpits. I have showered and am wearing both deodorant and perfume but I already feel uncomfortable. You wouldn’t think it was possible to feel both invisible and horribly self-conscious all at once, but I do. I always do at this sort of thing.

‘Ah! Hester, isn’t it?’

The husky voice makes me turn sharply to my left.

‘Oh, hello Saskia,’ I say, without enthusiasm.

Melissa’s annoying friend is gurning away, revealing a line of healthy pink gum above the white, almost horsey, teeth. A glass of something alcoholic and fizzy is held precariously in one manicured hand.

She laughs, but I don’t recall having made a joke. She leans over and I catch a strong scent of the cigarette smoke on her breath along with a pungently spicy perfume.

‘Have you just arrived?’ she says. ‘Can I get you a drinkie?’

I let my gaze sweep over her.

Today she is wearing a bright orange halter-neck dress that is cut very low and the two large brown orbs of her bust are almost popping out. In actual fact, her tan is so deep, she is probably darker-skinned than a good many coloured people. I glance down to see orange toenails with some sort of pattern on them poking out of gold sandals. She has money but absolutely no class, that one.

I force myself to meet her thickly made-up eyes. It always feels like she is secretly mocking me but I force myself to smile and say, ‘I can help myself, thank you.’

‘No, let me!’ she trills. The next thing I know, she has gripped me by the arm and she’s almost dragging me through a forest of people to the kitchen island, where we find Melissa, chatting animatedly to a small bespectacled woman.

‘Look who I found!’ says Saskia.

Melissa gives her a look I can’t read.

But then she says, ‘So glad you could make it, Hester,’ with real warmth. She even touches my wrist lightly and I don’t mind that her fingertips feel rather clammy against my skin. Maybe I am not the only person struggling with the muggy heat.

I am quite overcome with relief at her kind welcome. For a second I fear tears may well up. I did do the right thing in coming! Oh if only I’d had the courage to make a move sooner. What a waste of time it has been, this silly falling-out business.

‘Hello, Melissa!’ I say, ‘You’re looking lovely.’

And she is. She is pretty as a picture in a red and white flowered frock that cinches in at the waist. She has more class in her little finger than Saskia. I really don’t know what she sees in that woman.

‘What can I get you to drink?’ she says brightly, her arm sweeping to show the breadth of beverages on offer.

I hesitate. I was going to ask for a sparkling mineral water as usual. I’m not much of a drinker. But maybe it is the happy atmosphere here, or maybe it is the fact that Melissa and I are friends again, which makes me decide to let my hair down for once.

Why not? It can be my little celebration for finishing that computer course. I must tell Melissa about it at some point, but not yet. She is too busy with the party today.

‘I’ll have some of that lovely Pimm’s you’ve got in, if I may,’ I say. A confused frown pinches between her eyebrows and she looks around.

It takes a second for me to realize what I have said. The Pimm’s isn’t immediately visible. I only know about it, of course, because I happened to see the delivery earlier. It would be terrible if she thought I was spying on her. That isn’t at all what I was doing, after all.

Embarrassment congeals like cold fat inside my tummy but at that moment, thank goodness, she is commandeered by a laughing man to her left who seems to have something urgent to impart.

‘Pimm’s it is,’ says Saskia and melts away. I’m just thinking about quietly walking back the other way when I spot the woman Melissa was talking to when I arrived. She’s smiling at me in a hopeful sort of way, and I recognize straight away that she is feeling a little out of place, like me. I’ve always been good at reading people. I have a sort of antenna for it, if you like.

‘Hello, I’m Jess,’ she says, still smiling.

‘Hester,’ I say, flinching, as a very tall glass of Pimm’s, stuffed with cucumber and a long straw, is thrust at me by a tanned male hand.

‘Here you go, get that down your neck!’

Saskia’s son, Nathan, is standing next to his mother. The last time I saw him he was about eight years old and crying because he’d fallen off the trampoline, skinning his elbow. I seem to remember an incident involving a wee accident on Melissa’s sofa and a loud tantrum too.

Now he must be over six foot tall. He winds a muscular brown forearm around his mother’s neck. The boy has an unironed old t-shirt on and his hair hangs over his eyes in mucky blond coils. He grins, showing strong white teeth that look particularly carnivorous, and I notice that his green eyes have little gold flecks in them, as if he is lit by something bright within. I look away from his gaze. It’s too much, like looking at the sun. Saskia pulls him in for a loud kiss on the cheek, staring at me the whole time.

‘Isn’t my boy gorgeous?’ she says. ‘Go on, isn’t he?’

I feel quite sick with confusion. What am I supposed to say? If I say, ‘Yes he’s very handsome,’ she may think I am some kind of pervert who favours teenage boys, and if I say, ‘I think he could do with a good bath and a haircut,’ they will both be offended. Thankfully I’m saved by Nathan baying, ‘Gerroff!’ and pulling away from his mother, who bays with laughter.

Jess laughs politely as they move off to bother someone else, Saskia protectively cupping the back of her son’s neck.

Jess smiles at me again and I try to smile back, although my cheeks feel stiff and unnatural. I take a too-big sip of my drink and I can feel the alcohol seeping through me instantly.

I regard Jess. She’s a small woman, like me, with very short light-brown hair. I’m sure the rectangular glasses perched on her snub nose are very trendy, if you like that sort of thing.

‘Do you have any children, Hester?’ she says. She looks at me with open curiosity.

I can’t stop myself from heaving a sigh of resignation.

I should be inured to it by now.

But, ‘No, I do not,’ I say, perhaps a little sharply. Flustered, I gulp another large mouthful of the Pimm’s. It warms me down into my stomach and helps me avoid seeing the inevitable look of pity on Jess’s face. So I take another. I had forgotten how nice Pimm’s was. It’s slipping down so easily.

‘Me neither,’ she says cheerfully. I look at her with renewed interest.

‘I thought you were maybe connected to one of Tilly’s friends,’ she says conspiratorially. ‘It seems most people here are trailing teenagers. Here’s to being unencumbered!’

To my surprise, she tips her glass of wine and chings it against mine. Her lips quirk and her eyes twinkle. I find that I quite like her.

Emboldened by the alcohol I decide to change the subject.

‘So how do you know Melissa?’ I say.

‘Through Zumba classes,’ she says with a grin and does a funny little wiggle. ‘Have you ever tried it?’

I shake my head vigorously and have another sip. It’s only now that I am remembering I didn’t have any lunch. Zumba, indeed.

‘I’ve never really been one for foreign cookery,’ I say. Jess emits a strange squawk. I think she is laughing at me but all I can see is warmth in her eyes.

‘Hester, you are a bit of a hoot,’ she says.

‘Hmm, am I now.’ I’ve no idea why she has said this. New people should come with an instruction booklet, I think, taking another sip.

I peer at a table laden with food I can’t identify. I always find buffet-style eating a bit of a minefield. First there is the business of trying to hold a drink, the food, and a napkin all at the same time. Then there is the worry of having food stuck between your teeth. Terry once very cruelly pointed out that I had spinach in my teeth in front of guests, and I’ve never really got over it.

I realize Jess is looking at me and it must be time for me to make a comment back to her. I’ve really quite forgotten how to behave in public. Since I stopped working, I probably do spend a little bit too much time alone.

I suppose it’s a little like tennis: conversation. For some reason this makes me want to laugh and, to compensate, I take another sip of the drink. To my complete surprise, I realize I have finished it. I really am starting to feel quite relaxed.

‘Wow, that barely touched the sides!’ says Jess and before I know it, I’m grinning back. I don’t know why. It isn’t very funny. I really should have something to eat before too long.

‘I’ve finished mine too,’ says Jess. ‘Let’s get a top-up.’

‘Allow me, ladies!’

That annoying boy pops up next to us. I hand him my empty glass and he disappears off with it.

I smile at Jess. She really does seem terribly nice.

MELISSA (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

Melissa winces at the sudden starburst of pain behind her eyes. She slicks on more lipstick and then sighs, closing her eyes and leaning her forehead against the blissfully cool glass of the bathroom mirror.

The diazepam has done nothing but give her a dry mouth and her headache hasn’t responded to double painkillers. She has been sipping champagne all afternoon, yet remains completely sober. It seems her body is depressingly resistant to chemical help today, when she needs it the most.

She washes her hands and comes out of the en-suite. Mark has left a balled-up pair of socks in the middle of the floor. Melissa picks them up and then throws them savagely against the far wall. They drop to the carpet with a disappointing lack of bounce.

‘Fuck you Mark,’ she murmurs.

Mark was meant to return from a medical conference in Durham this afternoon, in time for the party. Then two days ago he’d announced that the BBC wanted to fit in some studio filming, to be slotted around the location scenes for the next series. The studio is in Manchester.

He had argued strongly that he had no choice, but when he’d added, ‘It’s not like Tilly wants this party, is it?’ it had been obvious how he really felt.

A few days ago she’d watched him throw his suit bag onto the bed, whistling like a man who has no real cares. Like a man who thinks everything is fixed now. He’d been wearing only a turquoise towel around his middle and she could see a new softness there. The bedroom was filled with steam and the scent of the Czech & Speake aftershave she’d bought him for Christmas.

He hadn’t even bothered with aftershave before his television career had taken off. Mark used to get his suits from John Lewis and he’d wear whatever ties and shirts Melissa put into his wardrobe. Now, despite putting on weight, he fusses about haircuts and Melissa has caught him patting under his chin and examining the line of his jaw in the mirror.

Always an attractive man, with his dark brown eyes and the smattering of salt-and-pepper in his hair, as he approaches 44, he looks more comfortable in his skin than ever before.

And look where that led us, she thinks.

A wave of torpid, sapping exhaustion washes over Melissa now. For a second she longs to crawl under the sheets, close her aching eyes and allow darkness to press her into oblivion.

Apart from Saskia, there are very few people downstairs who she actually wants to talk to. They are mostly parents she has met over the years or neighbours. The conversations with parents always felt like jousting matches, each jabbing the other with pointed boasts about their children. She doesn’t know any of Tilly’s boarding school friends, so these guests were mainly from primary school days. They had little in common anymore anyway.

Sometimes she imagined what would happen if any of them found out about the things she had done. A cold chill creeps over her arms and she rubs them briskly. The chances of anyone from Before recognizing her in that picture must be infinitesimal. She has been told that her light green eyes are distinctive. But lots of people have light green eyes.

Giving herself a mental shake, she arranges her face into one of friendly hospitality. She can do this. It’s really no different from putting on her make-up.

As Melissa comes to the bottom of the stairs she hears a piercing, high-pitched laugh she doesn’t recognize.

The party feels thinner somehow – like it has lost fat and heft, rather than individuals – and she wonders whether some guests have left without saying goodbye. Maybe she was upstairs for longer than she thought? Or maybe it is just that all the young people have decamped to the summerhouse at the bottom of the garden. She can hear the thump of music coming from there and hopes Tilly is finally enjoying herself.

There’s that baying laugh again. Emerging onto the patio she spies Hester, talking animatedly to a couple from the tennis club, who regard her with blank expressions. The scene is so unexpected it takes a moment to make sense of it. Hester’s hair is sticking damply to her forehead and her eyes have a bright, unfocused glaze. Is she … drunk?

The woman who once said, ‘Mind my French’, after using the word ‘bloody’ and who Mark once joked wears a chastity belt under her old-lady skirts? Hester, drunk?

‘Here she is!’ Hester trills as Melissa cautiously approaches.

Gary and Sue meet her puzzled gaze and Sue raises an eyebrow, quizzically, at Melissa, barely stifling a smile.

Melissa gives her a stricken look back.

‘I was just telling your friends Gary and … um … Thing, that I used to look after Tilly all the time when she was little. I was like an aunty to her, wasn’t I, Melissa? We’re all terribly proud of her now, aren’t we?’

Melissa grimaces and tries to convey an apology with her eyes to Gary and Sue.

‘Well, you certainly helped me out once or twice,’ she says. ‘And yes, we are very proud of her.’

Hester hiccups and then turns to look around the garden, her eyes narrowed.

‘Where did that Jess one go? I liked her. Although I’m not completely sure she isn’t one of those. Not that I care! Live and let live, I say. As long as they are not rubbing our noses in it.’

Sue tuts.

‘Oh dear God,’ says Melissa under her breath.

‘Gosh, look at the time!’ says Gary, pretending to look at his watch, not very convincingly.

‘It’s Pimm’s o’clock!’ trills Hester and collapses into giggles, staggering slightly against Melissa, who takes hold of her arm.

Hester leans into her. For a small woman, she feels surprisingly solid. Melissa is momentarily reminded of holding Tilly as a toddler; the dense heat of her compact body.

‘You seem to be having a good time, Hester,’ says Melissa tightly. ‘Have you had any water?’

Hester hiccups and belatedly puts a hand over her mouth.

‘I’ve only had two drinks but I do feel a little squiffy. Perhaps I should have some of your lovely nibbles! I was just telling, um, Thing …’, Sue smiles primly but doesn’t help her out, ‘that I offered some of my scones but it seems you have done a wonderful job of catering. It’s all lovely! Darned if I can identify any of it, though!’

At this she breaks into peals of laughter. Melissa realizes that she has never really heard Hester laugh properly before. The high-pitched seal bark hurts her head a little bit more.

‘Okay, maybe you should have a drink of water and something to eat, hmm?’ Melissa begins to steer her back into the kitchen, mouthing ‘sorry’ at Gary and Sue, who are already turning to each other and leaning in with conspiratorial grins.

Nathan watches her with a small smile as she comes into the kitchen. Melissa privately thinks that Saskia panders to him far too much. He and Tilly seem to have some sort of awkwardness between them and Tilly has called him, ‘a bit of an airhead’.

He’d even half come-on to Melissa at Christmas and she’d had to pretend it was all a joke. He certainly seems very amused by something as he studies Hester stumbling towards the table of food, which is now a wreck of weary salad leaves, smeared plates, and crumbs.

She wishes they would all go home. She only had this party as a sort of ‘fuck you’; to prove to herself that Mark’s betrayal hasn’t destroyed her. She is a survivor. Not that any of them even knew about it, apart from Saskia. But it all feels so much more trouble than it is worth.

Hester is now folding a mini pavlova into her mouth in one piece so cream dribbles from the corner of her lips. Melissa sighs and says, ‘Wait there,’ and goes to the sink. A woman she knows from the tennis club, Jennie, is nearby. She does a comical staggering motion and murmurs, ‘Gosh, she’s a bit worse for wear! Who on earth is that?’

‘My next-door neighbour,’ says Melissa in a low voice as water from the filter tap splashes noisily into the tall green glass. Normally she would add ice and some fresh mint but there’s no point wasting that on Hester. ‘She’s totally off her face, isn’t she? I didn’t even want her here but she sort of invited herself.’

The other woman laughs. ‘She banged on to me earlier about being one of the family or something,’ she says. ‘I thought it was a bit strange when you’ve never mentioned her!’

‘Oh God,’ says Melissa with feeling, turning off the tap.

‘Well she’s certainly making up for lost time with the food now!’ says Jennie stifling another laugh.

Melissa turns to see Hester cramming crisps into her mouth with a robotic regularity. She takes the water over and places it on the table next to where she stands.

‘Here,’ she says, no longer bothering to hide her irritation, ‘you’d better drink this and then maybe it’s time to go home for a lie-down. I think you’re going to need it, don’t you?’

Hester gazes up with unfocused eyes. Her skin looks clammy and blotchy now. She sways gently on the spot.

The doorbell trills. The sound, like a hard flick on a lighter wheel, ignites hope in Melissa’s chest. The pure joy of it comes as a surprise.

Could Mark have come home after all? But no, that’s ridiculous. He would use his key, wouldn’t he? She hurries to the door and can see straight away that it is a smallish man who stands there. She can’t think of any single men who were invited to the party.

As quickly as it came, the euphoria melts away and ice seems to form in the pit of her belly. Melissa has the strangest feeling that she can’t move. That she shouldn’t move. It would be a foolish act to take those few steps towards the front door.

She doesn’t believe in premonitions. But she does believe in following her instincts and something is telling her that she must not open that door.

She tries to breathe slowly. Be rational, she thinks.

Hasn’t she been feeling strange and paranoid all day? Thinking people are looking at her on the High Street? Peering in at her through the hairdresser’s windows?

It’s absurd.

She turns and looks at herself in the gilt-edged mirror she and Mark bought in an antique shop in Camden Passage when they first got together. He called it ‘shabby chic’ and the expression pleased her greatly. It was new to her and she liked very much that she was now a woman for whom shabby no longer necessarily meant poor, inferior, or dirty.

Melissa tries to breathe slowly as she gazes at her reflection. She sees someone poised and elegant who lives a safe, comfortable, middle-class life. Someone with no reason to be frightened.

The doorbell trills again, insistent as an angry fly banging against glass.

Licking her dry lips, Melissa moves towards the door.

HESTER (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

I’ve had such a wonderful time but I think perhaps I should have stayed away from all that rich food.

My tummy is churning and when I look around Melissa’s kitchen, it’s like all the edges of things have run in the wash. Everything is a bit blurry.

I’m not feeling too clever.

That’s one of Terry’s expressions. ‘Not feeling too clever, old girl?’ he’d say and it annoyed the heck out of me because he was eleven years my elder.

‘Bugger off, Terry,’ I say out loud and it surprises me so much that I belch, to my horror, really quite loudly. I mumble an ‘excuse me’ and realize a strange woman is standing very close to me. I think we spoke earlier but darned if I know what about.

I don’t know where she came from now.

She’s there with her big wobbly face, saying, ‘Are you all right? Are you okay?’ I can smell her perfume and it makes me think of the inside of old handbags that we would get in Scope, which contained all sorts of disgusting things. Old tissues. Sanitary ware. Sweeties stuck to the lining like tumours. This image is so horrible it brings bile into my mouth and the ground does a strange shift sideways. I clutch the table. The woman says, ‘Do you need to sit down?’

It’s the second time today someone has spoken to me like this.

I look her squarely in the eye. Hers are large and very dark. I think she is probably foreign. With all the dignity I can muster I say, ‘I am absolutely tickety-boo’, and then wonder why, because this is another irritating Terry expression. But the words skid and skate into each other like cars on an icy road. ‘Going to the bathroom,’ I say and this time it comes out a bit more clearly.

I am on the landing upstairs now. I remember, too late, that there is a downstairs toilet that would have been closer.

My head is swimming and my insides feel wrong. Maybe it was the pâté on those tiny blinis. It smelled so very meaty. Sometimes I am eating a chop, or a piece of pork, and I remember that it is a dead thing on my plate. It puts me right off. Then all I can think about are tumours and carcasses, which makes my stomach squeeze and relax like a big fist.

Oh dear.

I can’t quite remember which room is the bathroom.

I’m not sure I’ve ever been upstairs here in all these years of living next door. It’s certainly very different to mine. It really is twice the size. But how silly that I don’t know where to go! A small laugh turns into another belch. ‘Whoops, pardon me,’ I say to no one.

I can hear Melissa’s voice, pitched low, at the front door. Melissa! I’m so very happy and relieved that we are friends again. I think I will offer to help tidy up later. There will be such a lot to do. But I may need a small rest first.

If only I could find the bathroom.

I lean over the stairs, intending to ask her where I might find it, but there’s something strange about the way she is standing. Despite my fuzziness I can tell she is somehow braced. Her feet are apart and her shoulders seem to be high. She’s clutching the side of the door like a lifeline. How very odd.

Maybe it’s one of those Chuggers. Chugger buggers! I must say this to Melissa later when we’re clearing up, maybe over a well-earned cup of tea. It will really tickle her.

I lean over the banister a little further and somehow knock my ribs, quite hard. The pain makes me even more queasy. And now something strange is happening to the walls and landing, which tip and pulse around me.

I really must find …

I shove open the nearest door.

Sweat breaks out all over me, greasy and cold. My stomach turns inside out.

I’m staring into Tilly’s face. She’s saying something but I can’t hear because the sour sickness rises up, engulfing me and then spurting out onto the soft pale carpet.

I stare down at the small pool, pink with Pimm’s.

Things have gone terribly wrong.

MELISSA (#uf64af6e8-21e4-55a3-bf2a-6ee75102af77)

‘Hello, Mel. Well don’t just stand there, gawping. You going to invite me in, or what?’

Melissa clutches the doorframe. Viscous shock floods her spine.

She can’t think of a single word to say.

He can’t be here? On her doorstep?

He’s laughing; enjoying the moment. Immersing himself gleefully in her distress like a dog cavorting in a filthy puddle.

When she manages to find words, they tumble out messily.

‘What are you …? Why …?’ It feels imperative that she doesn’t say his name aloud. If she does, it will make this all the more real.

Jamie? At her house?

‘Come on, aren’t you even a little bit pleased to see me after all these years?’