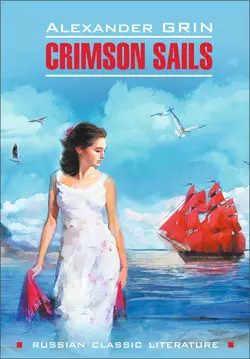

Scarlet Sails / Алые паруса. Книга для чтения на английском языке

Александр Грин

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Русская классика

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 361.00 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: КАРО

Дата публикации: 18.10.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: В книгу вошли замечательные произведения русского писателя Александра Грина «Алые паруса», «Искатели приключений», «Корабли в Лиссе» в переводе на английский язык.