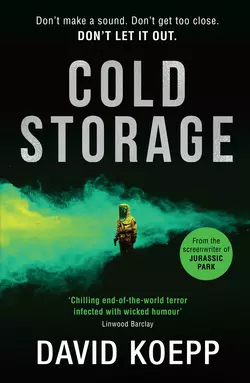

Cold Storage

David Koepp

‘To be simultaneously terrifying and hilarious is a masterstroke few writers can pull off, but Koepp manages in this incredible fiction debut that calls to mind a beautiful hybrid of Michael Crichton and Carl Hiaasen. Cold Storage is sheer thrillery goodness, and riotously entertaining’ Blake Crouch, NY Times bestselling author‘A thrilling, funny, and unexpectedly moving joy ride’ Scott Smith, NY Times bestselling authorThe astonishing debut novel by the screenwriter of Jurassic Park: a wild and terrifying adventure about three strangers who must work together to contain a highly contagious, deadly organism.When Pentagon bioterror operative Roberto Diaz was sent to investigate a suspected biochemical attack, he found something far worse: a highly mutative organism capable of extinction-level destruction. He contained it and buried it in cold storage deep beneath a little-used military repository.Now, after decades of festering in a forgotten sub-basement, the specimen has found its way out and is on a lethal feeding frenzy. Only Diaz knows how to stop it.He races across the country to help two unwitting security guards –one an ex-con, the other a single mother. Over one harrowing night, the unlikely trio must figure out how to quarantine this horror again. All they have is luck, fearlessness, and a mordant sense of humour. Will that be enough to save all of humanity?With swiftly plotted action, a sharp sense of humour, and an altogether brilliant display of storytelling, Cold Storage is a white-knuckled, uniquely enjoyable thriller.PRAISE FOR COLD STORAGE‘To be simultaneously terrifying and hilarious is a masterstroke few writers can pull off, but Koepp manages in this incredible fiction debut that calls to mind a beautiful hybrid of Michael Crichton and Carl Hiassen. Cold Storage is sheer thrillery goodness, and riotously entertaining’ Blake Crouch, New York Times bestselling author of Dark Matter‘A thrilling, funny, and unexpectedly moving joy ride’ Scott Smith, New York Times bestselling author

DAVID KOEPP is a celebrated American screenwriter and director best known for his work on Jurassic Park, Spider-Man, Panic Room, War of the Worlds and Mission: Impossible. His work on screen has grossed over $6 billion worldwide.

Cold Storage

David Koepp

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

Copyright (#ulink_3961a14d-4af0-5e1d-9383-599b0280ee1e)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © David Koepp 2019

David Koepp asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 978-0-008-33452-9

Note to Readers (#ulink_bebabdd5-c802-5b0b-a69d-8020ce5649be)

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008334512

FOR MELISSA, WHO SAID, “YEAH, SURE!”

Contents

Cover (#u7f31cb1d-8b89-501e-be62-3d1e33c90819)

About the Author (#u45f962b8-12e8-5bdc-8771-405a950a51bb)

Title Page (#u22ac657f-1eee-5523-bb25-604a663662fe)

Copyright (#ulink_91b06722-ccea-538b-925f-7f2d11aec8ad)

Note to Readers (#ulink_2194c7b1-c3dc-527d-8297-7dc2950e0791)

Dedication (#u1076a4dd-eec0-5936-a689-9e860ed0b74c)

Prologue (#ulink_afdcbc3c-98f8-5bfb-8b80-d3b0a20ea22e)

December 1987

One (#ulink_a255b7d5-37e7-5f46-bd9e-6eb918ae3593)

Two (#ulink_fc5c9e57-071a-56ba-b128-089ade44a7c4)

Three (#ulink_326e9963-2be1-52d4-ba01-4575601d91d5)

Four (#ulink_757241c8-ddf9-5e8b-b406-47a184487f3e)

March 2019

Five (#ulink_217bcb50-d195-595b-a2a2-6c04f8ca4af9)

Six (#ulink_89972ed6-0fab-5b66-bf80-900d4d6fca73)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

The Next Four Hours

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

The Last Thirty-Four Minutes

Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterwards

Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_bad43418-e75f-5950-b236-1eb24147d5a9)

The world’s largest single living organism is Armillaria solidipes, better known as the honey fungus. It’s about eight thousand years old and covers 3.7 square miles of the Blue Mountains in Oregon. Over eight millennia it has spread through a weblike network of lines underground, sprouting fruiting bodies above the earth that look like mushrooms. The honey fungus is relatively benign, unless you’re an herbaceous tree, bush, or plant. If you are, it’s genocidal. The fungus kills by gradual takeover of the root system and moves up the plant, eventually choking off all water and nutrients.

Armillaria solidipes spreads across the landscape at a rate of one to three feet per year and can take thirty to fifty years to kill an average-sized tree. If it could move significantly faster, 90 percent of all botanic growth on Earth would die, the atmosphere would turn to poison gas, and human and animal life would end. But it is a slow-moving fungus.

Other fungi are faster.

Much faster.

December 1987 (#ulink_7b4fb937-180f-50f7-acec-1223733320e9)

One (#ulink_14bcbed4-7075-57f0-a03c-f12e89f5ee82)

After they’d burned their clothes, shaved their heads, and scrubbed themselves until they bled, Roberto Diaz and Trini Romano were allowed back into the country. Even then they hadn’t felt entirely clean, only that they had done everything they could, and the rest was up to fate.

They were in a government-issue sedan now, rattling down I-73 just a few miles from the storage facility at the Atchison mines. They followed close behind the open-air cargo truck in front of them, tight enough that no civilian vehicle could get in between them. Trini was in the front passenger seat of the sedan, her feet up on the dashboard, a posture that always infuriated Roberto, who was behind the wheel.

“Because it leaves footprints,” he told her, for the hundredth time.

“It’s dust,” Trini replied, also for the hundredth time. “I wipe it right off, look.” She made a half-assed attempt to wipe her footprints off the dashboard.

“Yeah, but you don’t, Trini. You don’t wipe it off, you kind of smear it around with your hand and then I wipe it off when we return it to the pool. Or I forget and I leave it, and somebody else has to do it. I don’t like making work for other people.”

Trini looked at him with her heavy-lidded eyes, the ones that didn’t believe half of what they saw. Those eyes and what they could see were the reason she was a lieutenant colonel at forty, but her inability to refrain from commenting on what she saw was the reason she’d go no further. Trini had no filter and no interest in acquiring one.

She stared at him for a thoughtful moment, took a long drag off the Newport between her fingers, and blew a cloud of smoke out the side of her mouth.

“I accept, Roberto.”

He looked at her. “Huh?”

“Your apology. For back there. That’s why you’re bitching at me. You bitch at me because you don’t know how to say you’re sorry. So I’ll save you the trouble. I accept your apology.”

Trini was right, because Trini was always right. Roberto said nothing for a long moment, just stared out at the road ahead.

Finally, when he could, he muttered, “Thank you.”

Trini shrugged. “See? Not so bad.”

“I behaved badly.”

“Almost. But not quite. Seems like pretty small potatoes now.”

They’d talked endlessly about what had happened in the four days since it had all started, but they were pretty much talked out now, having relived and re-examined every moment from every conceivable angle. Except for this one moment. This one had gone unspoken, but now they were speaking about it, and Roberto didn’t want to leave it that way.

“I didn’t mean with her. I meant the way I talked to you.”

“I know.” Trini put a hand on Roberto’s shoulder. “Lighten up.”

Roberto nodded and stared straight ahead. Lightening up did not come easily to Roberto Diaz. He was in his midthirties, but his personal and professional accomplishments had raced ahead of his chronological age because he never lightened up, he Got Shit Done. He ticked boxes. Head of class at the Air Force Academy? Tick. Major in the USAF by the age of thirty? Tick. Superb physical and mental conditioning with no obvious flaws or weaknesses? Tick. Perfect wife? Tick. Perfect baby boy? Tick. None of this could be accomplished through patience or passivity.

Where am I headed?, where am I headed?, where am I headed?, Roberto would ask himself. The future was all he thought about, planned for, obsessed over. His life moved fast, it stayed on schedule, and he played things straight.

Well. Most things.

They both just stared at the truck ahead of them for a while. Through the canvas flap over the rear gate they could see the top of the metal crate they’d flown halfway across the planet. The truck hit a pothole, the crate slid back a foot or so, and they both sucked in their breath involuntarily. But it stayed settled in the back. Just a few more miles to the caves and this would be over. The crate would be safely stashed three hundred feet underground till the end of time.

The Atchison Caves were a limestone mine back in 1886, a massive quarry that went down 150 feet under the Missouri River bluffs. They started out producing riprap for the nearby railroads and dug as far down as God and physics would allow, until the pillars of unmined rock that held the place up reached the very outside limit of any sane engineer’s willingness to sign off on their safety. During World War II the empty caverns, now a sweet eighty acres of naturally climate-controlled underground space, were used to house perishables by the War Food Administration, and eventually the mining company sold the whole space to the government for $20,000. A couple million dollars in renovations later, it had become a highly secured government storage facility used for disaster and continuity of government planning, storing impeccably machined tools in a state of well-oiled readiness, set to ship them anywhere, any time, only please God let there be a nuclear war first so this was worth all the money.

It would be worth it today.

The call had been a weird one from the first ding. Technically, Trini and Roberto were with DNA, the Defense Nuclear Agency. Later it would become part of DTRA, but that particular government mishmash wouldn’t be cobbled together until the Defense Department’s official reorganization in 1997. Ten years earlier they were still DNA, and their brief was simple and clear: stop everybody else from getting what we have. If you smell a nuclear program, find it and wreck it. If you get a lead on some nightmarish bioweapon, make it go away forever. Expense will not be spared; questions will not be asked. Two-person teams were preferred, to keep things compartmentalized, but there was always backup if you needed it. Trini and Roberto rarely needed it. They’d been to sixteen different hotspots in seven years and had sixteen liquid kills to their names. Kills were not literal; it was agency-speak for a weapons program that had been neutralized. But there had been casualties along the way. Questions were not asked.

Sixteen missions, but none remotely like this one.

THE USAF TRANSPORT HAD ALREADY BEEN WARMING UP AT THE BASE when they bounded up the stairs and came on board. There was only one other passenger, and Trini took the seat directly opposite her. Roberto sat across the aisle, in a backward seat also facing the bright-eyed young woman in well-worn safari gear.

Trini held a hand out to her and the young woman took it. “Lieutenant Colonel Trini Romano.”

“Dr. Hero Martins.”

Trini just looked at her, nodding and popping in a piece of Nicorette, taking Hero’s measure, unafraid to hold silent eye contact while she sized her up. It was disconcerting. Roberto just gave Hero a half salute; he never enjoyed playing the whole I-see-right-through-you game.

“Major Roberto Diaz.”

“Nice to meet you, Major,” Hero said.

“What kind of doctor are you?” Roberto asked.

“Microbiologist. University of Chicago. I specialize in epidemiological surveillance.”

Trini was still looking at her. “That your real name? Hero?”

Hero hid her sigh. It was a question with which she was not unfamiliar after thirty-four years. “Yes, that’s my real name.”

“Hero like Superman or Hero like in Greek mythology?” Roberto asked.

She turned her gaze to Roberto. That was a question she didn’t hear nearly as much.

“The latter. My mother was a classics professor. You know the story?”

Roberto looked up, squinting his left eye and staring into the space just above and to the right of his head, the way he did when he was trying to pull an obscure fact out of his brain’s nether regions. He found the nugget of information and dragged it up out of the swamp.

“She lived in a tower on a river?”

Hero nodded. “The Hellespont.”

“Somebody was in love with her.”

“Leander. Every night he’d swim the river to the tower and make love to her. Hero would light a lamp in the tower so he could see his way to the shore.”

“But he drowned anyway, right?”

Trini turned and stared at Roberto, her displeasure plain. Roberto was good-looking to an irritating degree. The son of a Mexican father and a California blonde mother, he radiated good health and had a head of hair that would last forever. He also had a smart and funny wife named Annie, whom Trini actually found tolerable, which was saying something. Yet he’d been on this plane all of thirty seconds and was clearly trying to charm this woman. Trini had never picked her partner for a jerk before and hoped he wouldn’t turn out to be one now. She watched him, chewing her gum like she was mad at it.

But Hero was engaged. She kept on talking to Roberto, ignoring Trini.

“Aphrodite became jealous of their love. One night she blew out Hero’s light, and Leander was lost. When she saw he had drowned, Hero threw herself out of the tower to her death.”

Roberto took a moment and thought about that. “What exactly is the moral there? Try to meet somebody on your side of the river?”

Hero smiled and shrugged. “Don’t piss off the gods, I guess.”

Trini, weary of their banter, glanced back at the pilots and spun a finger in the air. The engines immediately whined, and the plane started to move down the runway with a jerk. Subject changed.

Hero looked around, concerned. “Wait, we’re going? Where is the rest of your team?”

“You’re looking at us,” Trini said.

“Are you—I mean, are you sure? This might not be something we can handle on our own.”

Roberto conveyed Trini’s confidence, but without the edge. “Why don’t you tell us what it is,” he said to Hero, “and we’ll let you know if we think we can handle it.”

“They told you nothing?” she asked.

“They told us we’re going to Australia,” Trini said, “and that you’d know the rest.”

Hero turned and looked out the window, watching as the plane left the earth. No turning back now. She shook her head. “I will never understand the army.”

“Me neither,” Roberto said. “We’re in the air force. Seconded to the Defense Nuclear Agency.”

“This isn’t nuclear.”

Trini frowned. “They sent you, so I assume they suspect a bioweapon?”

“No.”

“Then what is it?”

Hero thought about that for a second. “Good question.” She opened the file on the table in front of her and started talking.

Six hours later, she stopped.

WHAT ROBERTO KNEW ABOUT WESTERN AUSTRALIA COULD FIT INTO A very small book. More of a flyer, really: one page and with large type. Hero told them they were going to a remote township called Kiwirrkurra Community, in the middle of the Gibson Desert, about 1,200 kilometers east of Port Hedland. It had been established a decade earlier as a Pintupi outstation, part of the Australian government’s ongoing attempts to allow and encourage Aboriginal groups to move back to their traditional ancestral lands. They’d been mistreated and cleared out of those same territories for decades, most recently in the 1960s as a result of the Blue Streak missile tests. You can’t very well be living on land that we want to blow up. It’s unhealthy.

But by the midseventies the tests were over, political sensitivities were on the rise, and so the last of the Pintupi had been trucked back to Kiwirrkurra, which wasn’t even the middle of nowhere, but more like a few hundred miles outside the very outer rim of nowhere. But there they lived, all twenty-six Pintupi, as peaceful and happy as human beings can be in a stifling desert without power, telephone lines, or any connection to modern society. They rather liked being cut off, in fact, and the elders in particular were pleased with their return to their ancestral lands.

And then the sky fell.

Not all of it, Hero explained. Just a chunk.

“What was it?” Roberto asked. He’d been holding eye contact with her throughout the brief history so far, and don’t think for a second Trini didn’t notice. In fact, she was glaring at Roberto, as if psychically willing him to stop.

“Skylab.”

Now Trini turned her head and looked at Hero. “This was in ’79?”

“Yes.”

“I thought that fell into the Indian Ocean.”

Hero nodded. “Most of it did. The few pieces that hit land fell just outside a town called Esperance, also in Western Australia.”

“Close to Kiwirrkurra?” Roberto asked.

“Nothing is close to Kiwirrkurra. Esperance is about two thousand kilometers away and has ten thousand residents. It’s a metropolis by comparison.”

“What happened to the pieces that fell in Esperance?”

Hero turned to the next section of her notes. The pieces that fell in Esperance had been, rather enterprisingly, scooped up by the locals and put in the town’s museum—formerly a dance hall, but quickly converted to the Esperance Municipal Museum & Skylab Observatorium. Admission was four dollars, and for that you could see the largest oxygen tank from the orbiter, the space station’s storage freezer for food and other items, some nitrogen spheres used by its attitude control thrusters, and a piece of the hatch the astronauts would have crawled through during their visits. A number of other chunks of unrecognizable debris were also put on view, including a piece of sheet metal that rather suspiciously had the word SKYLAB neatly lettered in undamaged bright red paint across its middle.

“For years NASA assumed that was all that would ever be found, as the rest of it either burned up on re-entry or is at the bottom of the Indian Ocean,” Hero continued. “After five or six years, they figured anything else on land would have turned up by then or was somewhere uninhabitable.”

“Like Kiwirrkurra,” Roberto offered.

She nodded and turned another page.

“Three days ago, I got a call from the NASA Space Biosciences Research Branch. They’d gotten a message, relayed through about six different government agencies, that someone was calling from Western Australia because ‘something had come out of the tank.’”

“What tank?”

“The extra oxygen tank. The one that fell on Kiwirrkurra.”

Trini sat forward. “Who called from Western Australia?”

Hero looked down at her notes. “He identified himself as Enos Namatjira. He said he lived in Kiwirrkurra and his uncle had found the tank in the dirt five or six years earlier. Uncle had heard about the spaceship that crashed, so he moved it in front of his house and kept it there as a souvenir. But now there was something wrong with it, and he was getting sick. Quickly.”

Roberto frowned, trying to piece it together. “How did this guy know what number to call?”

“He didn’t. He started with the White House.”

“And it got through to NASA?” Trini was incredulous. Such efficiency was unheard of.

“It took him seventeen calls, and he had to drive thirty miles to get to the phone every time, but yes, he finally got through to NASA.”

“He was determined,” Roberto said.

“He was, because by that time, people were dying. They finally put him in touch with me about a day and a half ago. I do work for NASA sometimes, inspecting their re-entry vehicles to make sure they’re clear of any foreign bioforms, which they always are.”

“But you think this time something came back?” Trini asked.

“Not quite. This is where it gets interesting.”

Roberto leaned forward. “I think it’s pretty interesting already.”

Hero smiled at him. Trini tried not to roll her eyes.

Hero continued. “The tank was sealed, and I highly doubt that it could bring anything back from space that it wasn’t sent up with. I went through all the Skylab files, and on the last resupply it seems this particular oxygen tank had been sent up not for O

circulation, but solely for attachment to one of the outer pod arms. There was a fungal organism inside the tank, a sort of cousin of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis. It’s a cool little parasitic fungus that can adapt from one species to another. Known to survive extreme conditions, a bit like Clostridium difficile spores. You know those?”

They looked at her blankly. Knowledge of Clostridium difficile was not a requirement in their line of work.

“Well, they’re pernicious. They can survive anywhere—inside a volcano, bottom of the sea, outer space.”

They just looked at her, taking her word for it. She went on. “Anyway. The sample in the tank was part of a research project. The fungus had some peculiar growth properties and they wanted to see how it was affected by conditions in space. Remember, it was the seventies, orbital space stations were going to be the next big thing, so they needed to develop effective antifungal medications for the millions of people who were going to go live up there. But they never got the chance.”

“Because Skylab crashed.”

“Right. So, after five or six years sitting outside in front of Enos Namatjira’s uncle’s house, the tank started to rust. Uncle wanted to spruce it up a little bit, make it shiny and new again, maybe people would pay to come see it. He tried to remove the rust, but it was resistant. According to Enos, his uncle tried a number of different cleaners, finally using a folkloric solution: cutting a potato in half, pouring dish soap on it, and rubbing it on the surface of the tank.”

“Did it work?”

“Yep. The rust came off easily, and the thing shined up. A few days later, Uncle got sick. He started to behave erratically, not making a great deal of sense. He climbed onto the roof of his house and refused to come down, and then his body started to swell uncontrollably.”

“What the hell happened?” Trini asked.

“From this point forward, everything I say is hypothesis.”

She paused. They waited. Whether Dr. Martins was aware of it or not, she knew how to tell a story. They were transfixed.

“I believe the chemical combination that Uncle used dripped through microfissures in the tank’s exterior and landed inside, where the dormant Cordyceps fungus was rehydrated.”

“With the potato stuff?” Roberto wondered. Didn’t sound very hydrating.

She nodded. “The average potato is seventy-eight percent water. But the fungus wasn’t just rehydrated; it was given pectin, cellulose, protein, and fat. And a nice place to grow. The average temperature in the Western Australian desert at this time of year is well over a hundred degrees Fahrenheit. Inside the tank, it’s probably closer to a hundred thirty. Deadly for us, but perfect for a fungus.”

Trini wanted to get to the point. “So, you’re saying the thing came back to life?”

“Not exactly. Again, I’m speculating, but I think it’s possible the polysaccharide in the potato combined with the sodium palmitate in the dish soap to produce a pro-growth environment. Normally, they’re both large, boring, inert molecules, but you put them together, you might have some good unpredictable fun. Don’t blame Uncle; I mean, the guy was trying to produce a chemical reaction.”

She was getting warmed up now—her eyes shone with the intellectual exercise of it all—and Roberto couldn’t help it, he couldn’t tear his eyes away from hers.

“And he did?”

“He sure the fuck did!”

Lord, she swore too. Roberto smiled.

“But I don’t think either the polysaccharide or the sodium palmitate was the underlying change agent.”

She leaned forward, as if telling the punch line to a joke that everyone was absolutely going to love.

“It was the rust. Fe

O

.nH

O.”

Trini spit her gum into a tissue and popped in a fresh piece. “Do you think, Dr. Martins, that somewhere inside you lurks the capacity to summarize?”

Hero turned to Trini, her demeanor matter-of-fact again.

“Sure. We sent up a hyperaggressive extremophile that is resistant to intense heat and the vacuum of space, but sensitive to cold. The environment sent the organism into a dormant state, but it remained hyper-receptive. At that point, it must have picked up a hitchhiker. Maybe it was exposed to solar radiation. Maybe a spore penetrated the microfissures in the tank on re-entry. Either way, when the fungus returned to Earth it was reawakened and found itself in a hot, safe, protein-rich, pro-growth environment. And something caused its higher-level genetic structure to change.”

“Into what?” Roberto asked.

She looked from one to the other of them, the way a teacher looks at a pair of slightly dim students who refuse to grasp the obvious. She spelled it out for them.

“I think we created a new species.”

There was silence for a moment. Since it was Hero’s theory, she claimed naming rights. “Cordyceps novus.”

Trini just looked at her. “What did you tell Mr. Namatjira?”

“That I needed to check some things and he should call me back in six hours. He never did.”

“What did you do then?”

“Called the Defense Department.”

“And what did they do?” Roberto asked.

She gestured. “Sent you guys.”

Two (#ulink_ba1bd9a6-216a-5949-a500-423b5e9505bc)

The next six hours of the flight passed in relative silence. As they flew over the western coast of Africa and night fell, Trini did what she always did on the way to a mission, which was to take sleep when it was available. She also never passed an available bathroom without using it. It was the little things. Limit your needs. Hero got tired of looking at Trini’s boots on the seat next to her, so when the plane was mostly dark, she got up, climbed over her, and crossed the aisle to Roberto’s side.

“Do you mind?” she whispered, gesturing to the empty seat next to him. He did not mind. Not in the slightest. He shifted his legs, giving her room to squeeze through, and she made herself as comfortable as possible, settling into the seat next to him. The ostensible reason for the move was that this new seat would give her a place to put her own legs up, but she could have done that in the other seat, Roberto figured. Maybe the real reason had something to do with the slightly furtive eye contact they’d been making since she’d finished the briefing, but it worked better for him, psychologically anyway, if he assumed the obvious was the case, while knowing full well it was not.

The things you tell yourself.

The absolute truth was that Roberto was much less than innocent in this situation. He’d felt an immediate attraction to Dr. Hero Martins, and though it was the last thing in the world he would ever act on, he needed to know that the old charm was still there when he needed it. He and Annie had been married for just about three years, and it had been a rough start. Work was overwhelming for both of them in the first year, Annie had gotten pregnant much sooner than they intended, and the pregnancy was a difficult one, forcing her to stay in bed for the last four or five months of it. That’s hard enough for anybody, but Annie had been a perpetual motion machine; she was a journalist and accustomed to life on the road. Home confinement felt like a punishment. Then the baby came, and it was, you know, a baby.

That was pretty much it for their easy years. Where were the just-us years, where was the blissful early marriage time when we enjoyed our youth and beauty and freedom and each other, and where, as long as we’re talking, was the sex, for God’s sake? Roberto hated being this particular cliché, the married dude who laments the post-baby sex life wipeout, but still. He was a human male in the prime of his life. It was difficult, at this point, for him to picture himself and Annie making it to their emeritus years together. Not at this rate.

But he loved her. And he didn’t want to cheat.

So he flirted. He’d never really been good at it when it counted, but something about not wanting it to lead anywhere made it easier. Roberto surprised himself with the ease with which he could talk to attractive women at this point in life and how positively they responded to him. A stable and unattainable man with a job in his midthirties was a lot different from a twenty-four-year-old grunt with a hard-on and a tongue tied in knots.

It played neatly into Hero’s own predilections and preference. Since the end of her overlong, overly tortured post-college relationship with Max, a man-child doctoral student more or less her own age, she’d had a thing about married men. Not a thing for married men—that would suggest a certain amoral craving, doing a thing because it was bad, not doing it in spite of it being bad. No, Hero had a thing about married men, i.e., a personal rule or guideline, based on all the obvious advantages, which she had laid out in a notebook one day during an exceptionally dull class on laser micromachining. The advantages were, in order of importance:

1 They tended toward the adult in demeanor, having embraced life’s changes by showing a willingness to marry and some concept of shared existence, which by definition involved compromise and other-directed thinking.

2 They were usually better in bed, not just from volume of experience, but from repeated experience with the same woman, which couldn’t help but lead to a sense of how to give pleasure as well as receive, unless they were complete narcissists, which was usually unlikely, given reason 1.

3 They were polite and grateful and didn’t leave a lot of shit on the floor, having been housebroken for at least a few years by an adult woman not their mother.

4 They had somewhere to go, usually within a reasonable time frame after sex, which freed up her evenings for work.

5 They were, by definition, unable to pursue an exclusive relationship, which left her free to do as she liked, on the off chance something better came along.

Hero knew perfectly well that there were many, many reasons that did not work in their favor, that did not speak to the good character of the married lover, which she neatly summed up in a single item on the facing page of her journal:

1 They’re cheaters.

And so was she, and she knew it. She didn’t cheat on them; she never had multiple lovers—one romantic complication at a time was more than enough in her life. And she wasn’t cheating their unlucky spouses, by her estimation, because she didn’t know them and had never promised them anything. The only person she was cheating was herself, by hanging out with a succession of people who it seemed, by the very nature of their relationship, did not know how to love.

Still, here she was, and here Roberto was, and here they were, possibly headed to their own doom (rationalize much?), and there surely could be no harm in making a little pleasant, life-affirming conversation with a handsome soldier in his midthirties who clearly had a thing for her. The fact that he wore a wedding ring was a total coincidence.

While Trini slept, Roberto and Hero stretched their legs out on the seats in front of them, reclined as far as they could, and whispered to each other. They weren’t tired—the frisson in the air between them was too invigorating—so they talked about his life, with the exception of his wife and kid, and they talked about hers, with the exception of her romantic history with Guys Like Him. They talked about her work, and about his, and the dangers he’d faced, and the exotic and frightening places she’d been in search of new microorganisms. And as they talked, they slid lower and lower in the seats, and their heads inclined ever so slightly closer together, and when the cabin took on a bit of a chill somewhere over Kenya, Roberto got up, found a couple of harsh wool blankets in the storage cabinet nearby, and they snuggled underneath them.

Then she scratched her nose.

And when she put her hand back down, it was on the seat between them, her little finger brushing against the outside of his right thigh. He felt it, and she left it there. Another twenty minutes went by, another twenty minutes of effortless, breathy talk, none of it with even the whisper of impropriety to it, and the next move was his, which he made by shifting in his seat, theoretically to stretch his stiff legs, but when he put them back up on the seat in front of him, his leg was now fully pressed against hers, and she returned the pressure almost immediately. Neither of them spoke of it; neither of them acknowledged it in any way. If you listened to their conversation, you could assume they were two colleagues from slightly different fields who had met at a professional conclave and were having the most innocent, upstanding, and rather boring conversation in the world.

But she never moved her hand, and neither released the pressure in their legs. They knew. They just weren’t saying.

After a while, Hero stretched and stood up. “Bathroom.”

He pointed toward the back. She smiled thanks, squeezed out of the row, and walked off toward the rear of the plane.

Roberto watched her walk away. Inside, he was panicked, and had been for several hours. He couldn’t quite believe what was happening. None of his relatively innocent flirtations had ever gone nearly so far, and it was like sliding into a mud-slicked hole that he couldn’t climb out of. Every movement he made only pulled him deeper in, and when he didn’t move it was worse, gravity took over and pulled him down.

And he liked it. He was angry, not getting what he wanted or deserved at home, and why not this woman, this brilliant, beautiful creature who asked so little of him and found him so fascinating and was clearly, genuinely interested in him? Why not, other than the fact that it was completely wrong? Or maybe it wasn’t even happening. Maybe the pressure of her hand and leg had easily explainable and innocent reasons behind them—she probably hadn’t even noticed, for Christ’s sake—and he was letting his overactive sex drive run away with his rational mind, as usual.

Or maybe it was happening, and maybe he wanted it to. Maybe he would get up, wander to the back of the plane, talk to her some more there, and if her eyes happened to linger on his for a few seconds longer than they ought to, he’d kiss her. Maybe that’s exactly what he’d do. Maybe that’s what he’d get up and do right now.

Roberto summoned every bit of resentment he could find, every ounce of righteous indignation he’d acquired over three frustrating years of marriage, and he stood up.

That’s when he felt the hand on his arm.

He turned. Trini was awake, staring up at him, the fingers of her strong right hand clamped around Roberto’s left forearm.

Roberto looked down at her, his face turning into a poorly rendered mask of utter innocence. Trini just looked at him, her penetrating gaze bright even in the dim cabin light.

“Sit down, Roberto.”

Roberto’s mouth opened, but no words came out. He wasn’t a very good liar, even worse at wholesale invention, and rather than stammer out something stupid, he just closed his mouth again and shrugged an I don’t know what you’re talking about shrug.

“Sit down.”

Roberto did. Trini leaned over and put a hand on the back of his neck.

“That ain’t you, kid.”

Roberto felt a hot flush rise in his cheeks—anger, embarrassment, and thwarted desire sending any spare blood to his face on the double. “Stay out of it.”

“My advice exactly.” Trini kept staring.

Roberto looked away. He felt humiliated and wanted to make her feel the same. He turned back to Trini. “Jealous?”

He’d wanted to lash out, and he did; he’d wanted to hurt, and he hit the target. Trini’s face fell, ever so slightly, less in wounded pride than in disappointment.

Trini had been on the other side of her first and only marriage for ten years already, and the fact that she’d ever married in the first place was remarkable in itself. The marriage fell apart not because of the travel and secrecy required in her line of work, but because of her innate distaste for other human beings. People were okay; she just didn’t like looking at or listening to them. She’d been alone for a decade now and liked it.

In her mind, she’d always thought of her occasional attraction to Roberto as a purely chemical response to his rather overstated good looks. She liked him fine, she enjoyed working with him, she deeply admired his professionalism and the fact that he felt no compulsion toward small talk, but she’d never had any romantic interest in him whatsoever. He was her co-worker. Her incredibly good-looking co-worker. Sometimes even people who don’t like sweets admire a piece of chocolate cake. That’s what it’s designed to do: it’s supposed to look good. So was he. And he did, usually. No big deal. Trini kept it to herself.

But in ’83 she had been in a jeep accident and had broken two bones in her lower back, an exceptionally painful injury that resulted in her subsequent addiction to the painkillers the base physician had liberally prescribed to her. It was at bedtime that Trini liked them best; she’d take one an hour before bed and then nod off into drifty opiate sleep, feeling like nothing hurt, and not only that, even more than that, nothing ever would hurt, then or ever again. And where else in life can you get that assurance?

The addiction dug in and grew. It went on for nearly six months, undetected by everyone except Roberto. He confronted his friend about it and then gave enormous amounts of time, energy, and emotional support to help Trini get clean. Trini insisted on doing it without any other outside help whatsoever, and Roberto agreed to try. Early on, during one of Trini’s worst shaking, sweating, sleepless nights, she’d started to panic, and Roberto had climbed in bed with her and held her, just trying to get her through it all. Trini had looked up at him at one point, told Roberto she was in love with him and always had been, and moved to kiss him. Roberto deflected, told his friend to shut up and go to sleep, and Trini did.

They slept that way all night, and nothing happened. Roberto never told Annie about it, and in fact he and Trini had never spoken of it again themselves.

Until now, when Roberto wanted to hurt her.

Which he had.

From the other end of the plane, the bathroom door closed with a soft click. Hero came out and headed back to her seat.

Trini turned the other way and slouched down to go back to sleep.

Roberto moved to the window, shoved a pillow up against it, pulled the blanket up to his chin, and pretended to be out like a light when Hero got back.

In this way, the three of them flew on to Australia carrying considerably more baggage than they’d left with.

Three (#ulink_fdcd3b28-b6d8-51e7-9984-e9907dfbb25f)

The biohazard suits were uncomfortable as hell, and the worst part, in Trini’s opinion, was that there was nowhere to put a gun. She waved her Sig Sauer P320 around in the air near her hip, flapping her lips inaudibly behind the glass of her face piece.

Hero just looked at her, still puzzled by these soldiers and their inexperience with the very sort of event they’d been sent to investigate. She tapped the buttons on the side of the helmet, and her voice crackled in Trini’s headset.

“Use the radio, please.”

Trini fumbled on the side of her head until she found the right button and pressed it.

“Doesn’t this goddamn thing have a pocket?”

Outside Kiwirrkurra, they had changed into level A hazmat suits, which were fully encapsulating chemical entry suits with self-contained breathing apparatuses. They also wore steel-toed boots with shafts on the outside of the suit and specially selected chemical-resistant gloves. And no, there were no pockets, which would sort of defeat the purpose of the whole thing, providing both a nook and a cranny for God knows what to ride home with you.

Hero decided a simple “No” would suffice to answer Trini’s grumpy question. Trini had sucked down three cigarettes in quick succession after they’d landed—she’d been on Nicorette and the new nicotine patch for the entire flight—and she was wound tighter than the inside of a golf ball. Best to keep one’s distance, Hero decided.

Roberto turned and looked behind them, at the vast expanse of desert they had just crossed. Their jeep had kicked up a massive fantail of dust and the prevailing winds were blowing their way, which meant a few hundred kilometers’ worth of sediment was airborne and swirling toward them.

“Better get started while we can still see,” he said.

They turned and started the walk into town. They’d parked half a mile away and the going was slow in the suits, but they could see the structures that dotted the horizon from here. Kiwirrkurra was a collection of one-story buildings, a dozen at the most, unpainted, a patchwork of colors coming from the cast-off wood and scrap particle board that had been given to the residents by the resettlement commission. As far as planned communities went, it didn’t show much planning—just a main street, structures on either side of it, and a few outbuildings that had been thrown up later, possibly by latecomers who preferred a bit of space between themselves and their neighbors.

The first odd thing they saw, about fifty yards outside of town, was a suitcase. It sat in the middle of the road, packed and closed and waiting patiently, as if expecting a ride to the airport. There was no one and nothing else around it.

They looked at one another, then went to it. They stood around the suitcase, staring at it as if expecting it to reveal its history and intentions. It did not.

Trini moved on, holding the gun in front of her.

They reached the first building, and as they came around the front of it, they saw this one had only three walls, not four, built that way on purpose for maximum airflow in the intensely arid environment. They paused and looked inside, the way you’d look into a doll-house. There were cutaway areas: a kitchen, a bedroom, a bathroom (that room had a door), and another tiny bedroom at the far end of the structure. In the kitchen, there was food on the table, buzzing with flies. But there were no people.

Roberto looked around. “Where is everybody?”

That was the question.

Trini backed away, into the street again, turning in cautious semicircles, scanning the place.

“Cars are still here.”

They followed her gaze. There were cars, all right, just about one per driveway, a jeep or motorcycle or pickup or old sedan. However the residents had managed to get where they were going, they hadn’t driven.

They continued on, past what might have been a playground, more or less in the center of town. An old metal swing creaked on its chain, blowing in the wind that now swept the desert sand and dust into town ahead of it. Roberto turned and squinted into the coming clouds. The sand ticked against the glass of his faceplate, and it was hard not to blink, though of course he didn’t need to.

Another thirty yards and they reached the other side of town. The front door to the biggest house was ajar, and Trini pushed it open the rest of the way, using the barrel of the Sig Sauer. Roberto gestured to Hero to wait on the porch, and he and Trini stepped inside, one after the other, in a practiced maneuver.

Hero waited in front, watching their movements through the open door and the dirty front window. They searched the place, room by room, Trini always in the lead, gun in hand. Roberto was the more thorough and perhaps the more cautious of the two, moving carefully and steadily and never facing in the same direction for too long. Hero admired the grace and ease with which he moved, even in the cumbersome suit. But she also knew there was nothing to fear in there. Everything about Kiwirrkurra so far suggested a ghost town—she was sure of their result before Trini came out a few minutes later and announced it.

“Fourteen houses, twelve vehicles, zero residents.”

Roberto put his hands on his hips, relaxing his guard a bit. “What the actual fuck?”

That was when Hero saw what they’d come for. There, at the far end of town, in front of one of the best kept of the very modest houses, was a silver metal tank, its finish recently polished to a bright and reflective shine.

“I don’t think that’s from here.”

They walked toward the tank, wary. The wind swirled harder, and the dust in the air billowed around the houses, rearing up in columns in front of them before dust-deviling back to the ground in a corkscrew and moving on. It was getting hard to see.

“Stop here.” Hero held a hand out when they were still ten feet from the tank. She scanned the ground around them as best she could in the billowing sand, then continued on, searching the ground carefully before she placed each step.

“Walk in my footsteps.”

They did, following her in single file, careful to place their feet directly onto her boot prints as they went.

Hero reached the tank and squatted down. She saw the fungal covering immediately, but only because of her practiced eye. An untrained observer wouldn’t have perceived anything more than a greenish patch on the rounded surface of the tank, a bit like oxidized copper. The tank wasn’t in pristine condition anyway; it had made an uncontrolled re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, after all, that’s going to put a few dents in anything. But to Hero, the unremarkable greenish patch read like a semaphore.

Trini looked around them, still with her gun at the ready, just in case. She took a few steps toward the house, watching where she walked. She stopped, studying the building, which wasn’t very different from the other ones. But there was one thing she noticed—the car. An old Dodge Dart, it was parked at an odd angle to the house, its hood pushed almost right up against a porch pillar. The porch had a low-slung, corrugated roof that bent down at an angle, and from where the car was parked it wasn’t a very big step up from the hood to the roof. Trini looked up, thinking.

Back at the silver tank, Hero bent down, pulling her sample case around in front of her. She clicked it open, snapped out a 20x magnifying lens, and squeezed it to activate the LED lights around the edge of the beveled glass. Through the lens, she got a closer look at the fungus. It was alive, all right, and florid, visibly seething even at this magnification. She leaned as close as she dared, looking for active fragmentation. There was movement there, and she wished like hell she had a more powerful magnifier, but twenty power was the most the field kit carried, which meant she had to get closer still.

She looked back, over her shoulder, at Roberto.

“Slide your hand through the loop in the suit between my shoulder blades.”

Roberto looked down. There was a tight vertical flap of fabric sewn into the back of the suit, a handle of sorts, with just enough space to get his fingers through. He did as she asked.

“Now hold on tight,” she said. “I’ll pull against you, but don’t let me go. If I start to fall, give me a hard pull back. Don’t be shy about it. Don’t let me touch it.”

“You got it.”

He held on tight. Hero braced her feet just short of the tank, about a foot away from it, and leaned forward, putting the magnifying glass and her mask as close to the surface of the middle of the tank as she possibly could. Roberto hadn’t expected her to have quite as much confidence in him as she apparently did, and he swayed a little as she let her weight fall forward. But he was strong and recovered quickly, resetting his feet and holding her steady.

The faceplate of Hero’s helmet moved to within three inches of the surface of the tank, she switched the lens to max magnification and close focus and flicked the LEDs to their brightest setting.

She gasped. Through the lens, even at this minimal magnification, she could clearly see fruiting bodies sprouting off the mycelium, stalks with a capsule at the top, swelling at their seams with ready-to-spread spores. The mycelium’s growth was so fast it was visible.

“Jesus Christ.”

Roberto couldn’t see around her bulky suit, and the curiosity was killing him. “What is it?”

Hero couldn’t tear her eyes away.

“I don’t know, but it’s huge, and it’s fast. And heterotrophic; it’s got to be pulling carbon and energy out of everything it touches, otherwise there’s no way it …” She trailed off, staring at something intently.

“No way what?”

Hero didn’t answer. She was fascinated by one of the fruiting bodies. Its capsule was bloating beneath the lens, ballooning up off the surface of the tank.

“This is the most aggressive sporing rate I’ve ever—”

With a sharp pop, the entire fruiting body burst, and the lens of the magnifying glass was flecked with microscopic bits of goo. Hero shouted and involuntarily lurched backward, away from the tank. She was more startled than frightened but lost her balance for a moment and threw her right foot out to the side to steady herself. Her boot squished through something soft before finding solid ground next to the tank, but it was too little too late; she was past the tipping point and on her way down, right into whatever she’d just stepped in. She watched as the ground moved up toward her in slow motion.

And then she was moving upward again. With one strong, controlled tug on the loop at the back of her suit, Roberto pulled her onto her feet next to him.

She looked up at him, grateful.

He smiled. “Careful.”

A voice called from nearby. “Hey.”

They turned. Trini was standing on the roof of the house, about ten feet above them. “I found Uncle.”

It wasn’t much of a climb, even in the suits. First onto the hood of the car, then one big step up onto the porch roof, then a sort of jump with a shoulder roll, and they were all the way up. Roberto went last, so he could give Hero a shove up onto the roof if needed, and he was so preoccupied with making sure she didn’t fall that he failed to notice the sole of her boot, even when it passed within a foot of his face. He would have had to be pretty eagle-eyed to see it anyway, because there wasn’t much of the stuff, but it was there.

Near the heel, between the fourth and fifth hard rubber corrugated ridges of her right boot, there was a smear of green fungus she’d picked up when she lost her balance back at the tank.

Hero scrambled the rest of the way over the edge of the roof, Roberto flipped himself up to join her, and they walked the few paces over to where Trini stood looking down at something. The wind and dust had picked up substantially, so her view was partially obscured, but Trini knew a human corpse when she saw one. This one was in rough shape. Uncle couldn’t have been dead for all that long, but the damage to his corpse was extensive, and it wasn’t postmortem. The flesh wasn’t mangled from the outside, by scavengers or weather.

“He exploded,” Hero said.

Boy, did he ever. What used to be Uncle was now a husk that had been turned inside out, everything internal made external. His rib cage was wrenched open cleanly and violently at his sternum, parted like a suit coat lying on the floor with nobody in it. His arms and legs were denuded of flesh, their bones pockmarked with what looked like more tiny explosions from within, and the plates of his skull had been split apart along their eight seams, as if the glue that held him together suddenly failed all at once.

Roberto, who had seen a lot of ugly things, had never seen anything like this. He turned away, and as he did so the wind let up, the dust cleared for a moment, and all at once he had an unimpeded view looking back the way they’d come. Every building in town was more or less the same height, and from up here on top of Uncle’s house, he could see onto all the other rooftops.

“Oh my God.”

The others turned and saw what he saw.

The rooftops were covered with dead bodies, every single one of them burst open in the same way as Uncle’s.

Roberto didn’t need to count to know there would be twenty-six.

AT THE MOMENT THEY STOOD ON THE ROOF, PIECING TOGETHER WHAT had happened to the residents of the doomed village, the fungus was busily at work between the corrugated rubber ridges of Dr. Hero Martins’s right boot. Cordyceps novus had reached a barrier, the hard rubber sole between the boot and her foot, and if there was one thing it hated, it was a barrier. But every good villain has a henchman.

In its mutated state, the fungus housed an endosymbiont, an organism that lived within its body in a mutualistic relationship. What the fungus couldn’t do, the endosymbiont could—in this case, catalyze the synthesis of random chemicals in a special new structure in order to break through barriers. It was like having your own chemistry set.

The endosymbiont, which lived on the surface of the fungus in the form of a light sheen, was exposed to the atmosphere every time Hero took a step. It absorbed as much oxygen as it could, combined it with carbon drawn from the dust and dirt particles that had stuck to the goo, and formed a tight network of carbon-oxygen double bonds. These carbonyl groups, now active ketones, pushed their way upward, toward the sole itself, until stopped there by the hard, unyielding mass.

So it hybridized again. The new ketone sampled available elements from the rubber and dirt and dust and cycled quickly through a variety of carbon skeletons. It mutated into oxaloacetate, which is great if you want to metabolize sugar but no use getting through the sole of a boot. Undaunted, it mutated again, into cyclohexanone, which would have been good for making nylons, and then into tetracycline, superb if you’re fighting pneumonia, and then, finally and most damagingly, it recomposed itself as H

FSbF

—fluoroantimonic acid.

The powerful industrial corrosive began eating its way through the rubber bottom of Hero’s boot.

The mutation process so far had taken just under ninety seconds.

Hero, of course, was unaware of what was happening. As they climbed down from the roof and hurried back to the tank, she was distracted, trying to explain what they had just seen. The fungus, she speculated, was mimicking the reproductive pattern of Ophiocordyceps, a genus that consisted of about 140 different species, each one of which reproduced by colonizing a different insect.

“How’s it do that?” Trini had her gun out again and her head was on a swivel as they climbed down onto the roof of the car.

Hero explained: “Let’s say its target species is an ant. The ant walks along the forest floor, and it passes over a tiny spore of the fungus. The spore adheres to the ant, digs through its outer shell, and nests inside it. It moves through the body as quickly as it can, making its way to the ant’s brain, where the rich nutrients send it into an exponential growth phase, helping it reproduce up to ten times as fast as it would in any other part of the body. It spreads into every portion of the brain until it controls movement, reflex, impulse, and, to the extent that an ant can think, thoughts. Even though the ant is still technically alive, it’s been hijacked by the invader to serve its needs.” She jumped to the ground. “And the only thing a fungus needs is to make more fungus.”

Roberto looked around, understanding the town better now. Or the people, anyway. Jesus, the people, all of them.

Hero walked quickly to the tank and knelt down beside it, flipping open her sample case again. “The ant stops acting for itself. All it knows is it has to move. Up. It climbs the nearest stalk of grass, clamps its jaws down as hard as it can, and waits.”

“For what?” Trini asked.

“Until the fungus overfills the body cavity and it explodes.”

Roberto looked up at the roofs of the houses and shivered. “That’s why they climbed. To spread the fungus as far as they could.”

Hero nodded. “It’s a treeless wasteland. The roof was the highest spot they could find. You work with what you’ve got.” Her gloved hands picked carefully through the sharp metal tools in the case. She picked a flat-bladed instrument with a ring grip, slipped it over her right index finger, and flipped open a sample tube with her left hand. Carefully, she scraped as much of the fungus into the tube as she could. “It’s an extremely active parasitic growth, but that’s about all we’ll know until I can isolate the proteins with liquid chromatography and sequence its DNA.”

Roberto stared as she flipped the tube shut with a practiced gesture.

“You’re bringing it back?”

She looked up at him, not understanding. “What else am I supposed to do?”

“Leave it. We’ve got to burn this place.”

“Go right ahead,” she said. “But we need to take a sample with us.”

Trini looked at Roberto. “She’s right. You know she’s right. What’s the matter with you?”

Roberto didn’t get scared very often, but suddenly he was thinking about his little boy and about the possibility that he might never see him again. He’d heard having a kid could do that to you, make you tentative, aware that you served some purpose larger than yourself. To hell with the rest of the world, I make my own people now, and I have to protect them. Nothing else mattered.

And then there was Annie. I have a wife, a woman I love completely whom I was this close to betraying, and I would like very much to get back and get a head start on making that up to her, for the rest of our lives. That’s what was the matter with him, that’s what he was thinking, but he said none of it.

Instead, he said, “For Christ’s sake, Trini, it has an R1 rate of 1:1. Everyone who came in contact with it is dead, every single person. The secondary attack rate is a hundred percent, the generation time is immediate, and the incubation rate is … we don’t know, but less than twenty-four hours, that’s for goddamn sure. You want to bring that back into civilization? We’ve never seen a bioweapon with anything remotely close to this kind of lethality.”

“Which is exactly why it has to be tanked and studied. C’mon, man, you know that. This place won’t stay a secret, and if we don’t bring it back, somebody else’ll come get it. Maybe somebody who works for the other side.”

It was a valid debate, and while they carried on with it, the corrosive inside Hero’s boot heel continued to work with single-minded purpose. The fluoroantimonic acid had proven to be just the thing for eating through hard-soled rubber, but it wasn’t so much digging a hole as changing the chemical composition of the boot itself as it went along. Minor mutations occurred almost in a spirit of experimentation as the strength of the boot’s chemical bonds varied. The substance was a nifty adapter, zipping through most of the benzene group till it found the exact compound it was looking for. Finally, it reached the other side of the sole, evolving out onto the surface of the inner boot, just beneath the arch of Hero’s right foot. Benzene-X—it had hybridized so many times at this point that it defied classification according to current known chemical compounds—had opened a door for the fungus, which was so much larger in molecular size, to pass through to the interior of Hero’s suit.

Which is where Cordyceps novus found nirvana. The boot, like the rest of the hazmat suit, was loose-fitting, designed to encourage air circulation to prevent the wearer from overheating. The breathing apparatus contained a small fan for oxygen recirculation, which meant a fresh supply of O

was continually moving through the inside of the suit. Strands of grateful fungus spun off into whispery tendrils and went airborne, drifting upward on a rising column of warm CO

, until they landed lightly on the bare skin of Hero’s right leg.

Still unaware of the enemy invasion going on inside her suit, Hero screwed the top onto the sample tube, broke a seal on its side, and the tube hissed, a tiny pellet of nitrogen flash-freezing it until it could be reopened in a lab and stored permanently in liquid nitrogen. She dropped the tube back into the foam-padded slot in the case, clicked it shut, and stood up. “Done.”

The debate over what to do next had been resolved the way it always was, which is to say that Trini prevailed. She heard Roberto’s arguments, let them go a little bit past the point she felt was necessary, given the difference in their ranks, then looked directly at her friend, lowered her voice a tone or two, and said just one word.

“Major.”

The conversation was over. Trini was the officer in charge, and the advice of the scientific escort was on her side. The outcome had never been in doubt, but Roberto had felt a humanitarian urge to object anyway. What if, just this once, they did what was obvious and right, even if it was directly contrary to procedure? What if?

But they’d never find out, and in the end, Roberto settled on a secondary assurance: they would take one sample, one, carefully sealed in the biohazard tube, and would not leave Western Australia until the two respective governments had agreed to drop an overkill load of oil-based incendiary bombs on the place. Anything would suffice, even old M69s or M47s loaded with white phosphorous would do the job. There was nothing left to save here anyway.

They left town and walked back toward the jeep.

Four (#ulink_4f3606a5-2303-5c54-b7aa-da26c04c9c2c)

Inside Hero’s suit, Cordyceps novus found what it had been looking for: a tiny scratch in the surface of Hero’s calf. Even an overwide pore opening would have been big enough for it to gain entry into her bloodstream, but the open scratch, which cut through two layers of her skin, fairly yawned with possibility.

Hero didn’t even know she had an open wound. It had been an absent-minded scratch; she was reacting to an itch produced by a changed cleaning product—the hotel that washed her jeans last week had used a cheap optical brightener with a higher concentration of bleach than she was used to. So it itched. And she scratched. And the fungus entered her bloodstream.

“What’s that smell?” Hero asked. They were fifty yards from the jeep.

Roberto looked at her. “What smell?”

She sniffed again. “Burnt toast.”

Trini shrugged. “Can’t smell anything.” She looked back, glad to leave the town behind. “This whole place is gonna smell like burnt toast by the end of the day.”

But Roberto was confused, still looking at Hero. “In your suit?”

Hero held up an arm and regarded it, as if reminding herself she was wearing a sealed biohazard suit. “That doesn’t make sense, does it?”

In fact, it made perfect sense. Cordyceps novus was really warming up and had superheated the starches and proteins just inside Hero’s epidermis. As a by-product of the reaction, they outgassed acrylamide, producing the same smell as burnt toast. It was generating heat as well, and the sudden rise in temperature on Hero’s skin would surely bother her soon. But the fungus was attentive to that possibility and was moving fast through her bloodstream, racing to get to her brain, where it would intercept the messages from her pain receptors. This in itself was no great trick—a tick does the same thing, releasing a surface anesthetic as soon as it burrows into its victim’s skin so its bloodsucking can go unnoticed for as long as possible. But the fungus had a long way to travel and a lot of receptors to block. Hero’s heartbeat accelerated, which circulated her blood faster, inadvertently helping her would-be killer.

She stopped walking. “There can’t be a smell in my suit, it’s sealed and overpressured. There’s nothing in here but oxygen and clean CO

. Why is there a smell in my suit?”

She was starting to panic. Trini tried to defuse it. “There are probably a lot of jokes I could make here—”

“It’s not fucking funny,” Hero snapped.

“It’s not, Trini, shut the hell up. Something penetrated her suit.”

“That’s not possible,” Hero said, to convince herself as much as anyone else.

“Just keep moving,” Trini advised. “We’ll lose the suits at the jeep. We can’t take them out of here anyway, they need to burn. We’ll check yours for breaches.” She looked at Hero, her manner serious. “Do you feel anything?”

Hero thought. “No.”

Roberto persisted. “Take a minute. Focus on each part of your body. Anything different at all?”

Hero’s breathing steadied. She considered the question, going through her anatomy from the bottoms of her feet to the top of her head. “No. Nothing different.”

Inside her body, it was a different story. The fungus had penetrated Hero’s brain and was reproducing at nightmare speed, seeking out and blocking her nociceptors the way an invading army shuts down the internet and television stations. There was a red alert blaring in Hero’s brain, flags were waving, alarm bells ringing, but the ends of her sensory neurons’ axons had been taken over and blocked from responding to damaging stimuli. They could no longer send potential threat messages to her thalamus and subcortical areas. They were screaming into a void.

Hero Martins was dying, but the neural message she got from her brain was that everything was fine, just fine, don’t worry about a thing.

“I’m okay.”

“You’re sure?” Roberto asked.

She nodded. “Let’s just get out of here.”

They started walking again, now forty yards from the jeep. Hero’s brain thought through possible reasons a foreign smell should have presented itself inside her suit. Nothing believable came to mind. She decided she would not destroy this suit; she was going to tank and return it, she wanted to have a chance to take it apart and look at every inch of it in case there was a tear or foreign substance inside, in which case somebody in PPE was going to get an earful about procedure.

The jeep was now thirty yards away. Hero felt light-headed and realized she hadn’t eaten since nine or ten hours ago. Then again, looking at Uncle’s mutilated corpse wouldn’t exactly stimulate anyone’s appetite, so there was no reason to think anything unusual about that. She ran through her physical inventory once again, but other than an elevated heart rate and some quickened breathing, there wasn’t anything physically different about her that she could detect. She squinted up at the sun, and as she did a thought floated through her mind.

except there’s no telephone service out here

Well, no, there wasn’t. What did that matter? She looked down at the case in her hand, thinking about what she had inside the tube. People were going to lose their minds over this one. She wondered if the CDC would even accept it.

so there’s no telephone poles

She shook her head to clear it and resumed her train of thought. There were only a handful of labs in the Western Hemisphere that were set up to store biosafety level 4 pathogens, and Atlanta and Galveston would reject it outright, improperly classifying it as extraterrestrial because of its trip outside Earth’s atmosphere.

maybe an electrical tower

The U.S. Army would fight for it, no question about that, but Fort Detrick had suffered a breach eighteen months ago and no one was eager to—

they’ve gotta have power right don’t they have power?

She snapped her head to the side, Come on, focus. They were ten yards from the jeep. Her image of it suddenly shuddered and divided into sixteen identical rectangular boxes, sixteen images of the jeep, neatly separated and replicated. Hero felt her skin go cold because that wasn’t something you could easily ignore or pass off to hunger or exhaustion, but then again, she thought, I used to faint when I was a kid, in school assemblies sometimes, and didn’t it feel like this?, wasn’t there a prickling in her scalp and then her vision would go weird and she’d see double right before she keeled over sure that was probably it low blood sugar or

a radio tower, fifty kilometers back, didn’t I see something, wasn’t it a radio tower?

The image swam through her mind, crisp and clear: they had driven past a radio tower in the middle of the desert, just alongside the road, about a hundred meters high, with a small black utility box at the base of it.

“That’s exactly what it was.”

She’d said that last bit out loud, and Roberto and Trini turned and looked at her.

“What?” Roberto asked.

She looked at him. “Huh?”

“That’s exactly what what was?”

Hero had no idea what he was talking about. Was it possible that Roberto had somehow become infected by the fungus, that it was his suit that had malfunctioned, and that he was starting to lose his mind? She certainly hoped not, he was a nice enough guy, even if he was a total flirt, she really had to lay off the married men, never again, she vowed, right there and then, from now on either find someone appropriate or be content with

It can’t be that hard to climb.

Oh, shit. She had to think this through.

To climb. The radio tower. It had lateral struts about four or five feet apart, but there’s probably a service ladder inside the structure, how else would they repair anything that broke near the top of the thing? I could climb that.

For the last time, the weight and pressure of the healthy, functioning neurons in Hero’s brain outweighed those that had been consumed, destroyed, or shut down by Cordyceps novus. Her prefrontal cortex, which handled reasoning and sophisticated interpersonal thinking skills, reasserted itself in a burst of clarity and control, and told her quite clearly that based on:

1 her disordered thought processes;

2 the smell of burnt toast inside her suit that indicated a foreign contaminant;

3 the expressions on the faces of Trini and Roberto, who clearly thought something was wrong with her; and

4 her sudden and irrational fixation on the feasibility of climbing a fucking radio tower, for Christ’s sake, she had likely been infected by the fungus and was moments away from coming under the control of a rapidly replicating fungus that constituted an extinction-level threat to the human race.

Still walking, she glanced to her right and saw Trini was carrying her handgun loosely at her side as she and Roberto looked back and forth from her to each other, trying to communicate their concern wordlessly rather than over the radio system, which she would be able to hear.

Take the jeep and drive to the tower.

Hero walked faster, headed for the jeep. They let her, happy to fall behind so they could keep an eye on her.

Climb the tower.

As Hero neared the jeep, she saw the keys, the sunlight shining off them in the ignition. She felt pulled toward them.

Climb the tower.

Hero’s frontal lobe was in a doomed fight for control. It made up a third of the total volume of her brain, but was now overrun with a florid, healthy colony of Cordyceps novus. Her flag of intellectual independence fell. Still, her conscious thought didn’t give up; it merely darted away, blew through the wasteland of her already conquered temporal lobe, and turned in desperation to the last part of her mental apparatus that was still free—her parietal lobe. There, her thought stream was precariously her own, but severely limited.

just math now, math and analytics, where X = regeneration of healthy brain tissue probability is zero-X, try recovery rate, recovery rate in event of default

She was pulling up a freshman economics class now, but it was the only scrap of useful knowledge left kicking around unfettered in her head, the only avenue of reasoning left open to her, and it was going to have to do. So, let’s try a calculation, shall we? The equation to be formed would need to answer only one question: Could she survive this?

recovery probability versus loss given default (RP < or > LGD) dependent on instrument type (where IT = hypereffective mutating fungus), corporate issues (where CI = major default of more than 50 percent of healthy brain tissue), and prevailing macroeconomic conditions (where PMCs = every single other person who ever encountered this thing is dead), so RP = IT/CI × PMC = there is no fucking chance whatsoever.

The answer was no. She could not recover. She was going to die. The only question was how many people she was going to take with her when she did.

CLIMB THE TOWER, her brain told her.

And with the tiny bit of volition Dr. Hero Martins still had left, she replied.

NO, she said.

She turned around, fast. Trini didn’t have time to react, in part because she was too stunned by the sight of Hero’s swollen, heaving face, which was distended and discolored, the skin stretched so tight it was cracking. Hero was on her before Trini knew what was happening. She wrenched the gun from Trini’s hand—

“Gun out!” Trini shouted, but Roberto had already seen it. He yelled at Hero to stop, but she was backing away from them already, backing away and turning the gun around on herself. She reached up with her left hand and ripped her suit’s Velcro flap over the zippered O

access port, tore that open, shoved the gun inside the suit, sealed the Velcro flap around the barrel, pressed the barrel of the gun up against her chest—

“Don’t!” Roberto yelled, knowing it was too late even as he said it.

Hero pulled the trigger.

The bullet broke her skin and crashed through her breastbone, tearing open a hole in her chest the size of a quarter. Like a balloon popped by a pin, the rest of her went all at once, bursting at the sudden release of pressure. All Trini and Roberto saw was her head, which in one moment was a disfigured, although recognizable, human head, and the next moment was a wash of green gunk that completely covered the inside of her faceplate.

Hero fell, dead.

But she’d kept her suit intact.

LESS THAN SEVENTY-TWO HOURS LATER, TRINI AND ROBERTO WERE IN the car, just over three miles away from the Atchison mines, their eyes glued to the box in the back of the truck just ahead of them. Hero’s field case had been packed, unopened, into a larger sealed crate filled with dry ice.

So far things had gone smoothly. Gordon Gray, the head of the DTRA, had taken Trini and Roberto exactly at their word, because they were the best, and he ordered their explicit instructions be followed to the letter. When Gordon Gray gave an order, people followed it, and since all the residents of the town were dead and the land itself held no value, there was no one and no reason to object. The firebombing of Kiwirrkurra was agreed to without debate by the respective governments. The unlucky place burned, and with it every molecule of Cordyceps novus, except for the sample in Hero’s biotube.

The question of what to do with the tube was tougher to answer. As Hero had speculated, the CDC wanted no part of storing something that had been born, or at any rate partially bred, in outer space. Though the Defense Department was willing, its only suitable facility was Fort Detrick, which was out of the question. The breach there eighteen months earlier had triggered a top-down review that was only now entering its second stage, and the idea of cutting short a safety analysis in order to store an unknown growth of unprecedented lethality was not met with enthusiasm.