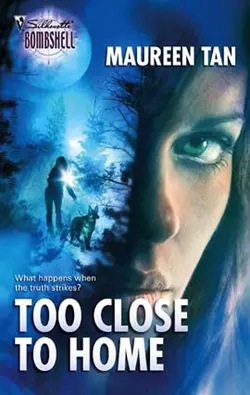

Too Close To Home

Too Close To Home

Maureen Tan

Brooke Tyler knows a thing or two about secrets. Growing up, she'd sworn to keep certain skeletons in the family closet. But her silence came at a heavy price, not the least of which was giving up the love of her life.Today, Brooke is a small-town cop, sworn to uphold the law and uncover the truth. Until her latest investigation unearths another long-buried secret: a dead body. And then others. A virtual killing field. As she delves into these murders, Brooke discovers more than she bargained for–that every secret she's ever kept was based on a lie….

If Chad could manage to approach this case with professionalism and some measure of detachment, so could I.

Until the forensics report came in, I would avoid speculating about who the murder victim—and the murderer—might be. I would investigate this crime just as I’d investigate any other crime. I would work with Chad and we would build our case carefully and meticulously. Basing it on facts, likely circumstances and evidence.

And if the investigation pointed to someone I loved? Threatened to expose facts long buried?

My stomach did a half twist, destroying my sense of calm.

Just do your job, I told myself. The way you were taught. One step at a time. Follow the evidence wherever it leads.

Then deal with the consequences.

Dear Reader,

Have you been lost and alone in a forest at night?

During a search-and-rescue training exercise, I put myself in that situation, experiencing the disorientation and terror that real victims often feel. My imagination ran wild as small forest noises became threatening sounds and uneven darkness tricked me into seeing shadowy forms. At one point, I was sure that ticks were raining down on me from the trees overhead and I fought the impulse to run away screaming. You can imagine my relief when a young German shepherd crashed through the underbrush with his human handler fast at his heels.

That night and my love of dogs were the inspiration for Too Close to Home’s heroine, rookie cop and search-and-rescue volunteer Brooke Tyler. Brooke’s fictitious adventures play out against a real and often treacherous backdrop—the atmospheric Shawnee National Forest area of southern Illinois. From the murky water of a cypress swamp to towering river bluffs to forested hills cut with jagged ravines, Brooke must confront and overcome challenges.

An intriguing geography of the heart is as important to me as the story’s physical geography. Brooke’s world is complicated by her family’s commitment to helping abused women escape to safety. No sooner than she’s found the man she’ll love forever, she’s sacrificed that relationship to protect her family’s dangerous legacy. The question is, can she live with her heartbreaking decision and overcome perils that strike Too Close to Home?

Maureen Tan

Too Close to Home

Maureen Tan

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Books by Maureen Tan

Silhouette Bombshell

A Perfect Cover #9

Too Close to Home #108

MAUREEN TAN

is a Marine Corps brat, the eldest of eight children and naturally bossy. She and her husband of thirty years have three adult children and two grandchildren. They currently share their century-old house with a dog, three cats, three fish and a rat. Much to his dismay, their elderly Appaloosa lives in the barn. Most of Maureen’s professional career has involved explaining science, engineering and medical research to the public. To keep her life from becoming boring, she has also worked in disaster areas as a FEMA public affairs officer and spent two years as a writer for an electronic games studio. Maureen’s first books, AKA Jane and Run Jane Run, detail the exploits of a female British agent.

For the kind and hospitable folks of Elizabethtown, Illinois. For my family and friends of all generations. For my mother, who taught me reading and courage and love. And especially for Peter, who still looks good in jeans.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Epilogue

Prologue

I was sixteen. Old enough that I no longer believed in story-book monsters. Young enough that, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, I didn’t quite believe in human monsters.

Dr. Porter changed that.

“I’m getting tired of waiting,” he called from the vicinity of the living room. “Come take your punishment like a good little wife.”

His coaxing, reasonable voice was accompanied by the rhythmic slapping of a leather strap against an open hand. The sound echoed off the glossy, hard surfaces of the expensive suburban home and carried clearly into the kitchen at the back of the house.

“Obviously, you’ve forgotten who your master is,” he continued. “You must be reminded.”

From where I stood, I couldn’t see Dr. Porter. Or the strap. But I’d seen the welts and bruises left by the strap. Left by Dr. Porter on his wife’s flesh. So maybe that was why it was all too easy to imagine what he looked like. No matter that I knew better, that Aunt Lucy and Gran had more than once reminded me that appearance was a poor predictor of behavior, I couldn’t help but picture bulging muscles and twisted, lunatic features.

Nothing about his voice convinced me otherwise. And because my upbringing was Baptist and biblical, I imagined it was the same voice the serpent had used in the Garden of Eden. Low, vaguely seductive and absolutely evil.

“It will only be worse if I have to come get you, Missy.”

My name was Brooke. Not Missy. Missy Porter was gone. And monster or not, devil or not, I stood my ground and waited for her husband. Because that was what I’d promised Missy I would do.

Just moments earlier, when the lock had turned in the front door, she’d been standing beside me in the kitchen. I’d watched as the blood drained from her face and she began trembling.

Missy was terrified. With good reason. Earlier that day, her husband had come home unexpectedly and found her packing. Missy’s punishment began before he’d left the house and he’d promised to continue it when he returned. In the meantime, he’d taken their twin sons away with him, confident that she would never run away without her children.

When we’d first arrived, she hadn’t answered the door. Fearing that Dr. Porter’s escalating abuse had turned homicidal, Gran and I crept around the house trying to get a glimpse inside. We found an open window, shouted Missy’s name again, and heard a woman sobbing.

Right then, I’d seen in Gran’s face that she wished Aunt Lucy was at her side. But Aunt Lucy was home with a broken leg and—no matter that I was nothing more than a gawky adolescent girl with boring brown eyes and chopped-off brown curls—I was her replacement on this rescue. Mostly because, unlike Gran, I could see well enough to drive after dark. I was also undeniably more nimble than Gran. Reluctantly, she agreed that I should crawl inside. Without saying a word, she gave me the big leather handbag that concealed my grandfather’s gun.

I’d found Missy in the kitchen, sitting naked on the stool where her husband had ordered her to stay, urine puddling on the floor beneath her. Horrified and unsure of what to do or say, I ran to the kitchen door and let Gran in. Valuable time passed as she convinced Missy to leave the stool, to escape as planned. Then Gran stood guard on the front porch and I waited inside as Missy got dressed.

We were almost to the foyer when the doorbell rang three times. A warning that Dr. Porter was approaching. Gran’s usual tactic—posing as a neighbor in search of a lost cat—bought us enough time to backtrack to the kitchen. And in that time, Missy lost her nerve.

As her husband bellowed for her from the front of the house, she stood, indecisive, unable to chose between the promise of escape and the certainty of abuse, between the risk of directing her own life and the terror of letting her husband control it. With her children in the balance, the decision was agony. And it was hers alone. In the end—with the sound of her husband’s heavy steps echoing down the hallway toward us—she chose survival.

“Run to the blue van parked down the street,” I whispered just before she bolted out the kitchen door. “I’ll slow him down, give you time to get away.”

I pulled my grandfather’s gun from the handbag.

I waited for the monster to come get me.

Dr. Porter’s cool tone warmed with growing anger.

I flinched at the obscenities he thought he was directing at his helpless wife, used both hands to support the weight of the bulky Smith & Wesson Victory revolver and waited for him. His breath, I was certain, would smell like rotting meat. His face would have flaring nostrils and pointed teeth. His eyes would be reddened by bloodlust and fury. It was the stuff of horror flicks and nightmares and novels by Koontz and King. But it was happening to me.

He screamed as he rushed through the doorway.

“You little bitch! I’ll drag your fuc—”

The sight of me and my gun brought him slamming to a halt.

“Missy’s not home,” I said into the sudden silence.

Between us was the polished granite counter, six empty plastic water bottles and the stool where he’d left his wife sitting for several agonizing hours. He’d compelled her to drink every bottle, then ordered her to remain on the stool until he returned. After years of being battered into submission, she’d done exactly as he’d said.

The revolver trembled in my hands as I pointed it past the water bottles to a spot where a blue silk tie was framed by the V of his gray vest. His light brown eyes stretched wide as his lips formed a moist O surrounded by the short, wiry hairs of his beard.

I returned his stare, as surprised by his appearance as he was by mine. He was ordinary. Absolutely, horrifyingly ordinary. Medium height, slightly pudgy and dressed in a three-piece suit. Mouse-colored hair had receded enough to make his forehead look tall, and his neatly trimmed mustache and beard were shot through with gray. His right shoulder was slightly humped, but not so much that he would stand out in a crowd of other middle-aged, average-looking men.

No matter how he looked, I told myself, he was still a monster. A threat to Missy. And to me.

“Drop the belt,” I said.

He surprised me again by immediately opening his hand and releasing the thick leather strap. Its buckle clattered noisily against the tiled floor, but he didn’t take his eyes from me and the gun I held. The bright spot of the task light above the counter glinted off a string of spittle at the corner of his mouth.

It was then, suddenly, that I realized the monster was terrified. Of me. And that I—Brooke Tyler—was utterly in control.

My hands steadied as my fear was replaced by an awareness of my own power. And the power of the weapon I held. With just the slightest pressure of my right index finger, I could kill this monster who looked human but took pleasure in torture and pain and humiliation. I could keep him from hurting Missy—or any other woman—ever again.

It wouldn’t be murder, wouldn’t be a sin. It would be justice.

Something in my expression told him what I intended.

He raised his hands in front of his face, arms crossed at the wrist and palms faced outward as if they could shield his face from the impact of a .38 caliber bullet. And he whimpered.

Maybe that very human reaction saved his life. Or maybe it was the sound of a horn blaring outside. Three times, then twice again. The signal that Missy was safely inside the van. A reminder of the promise I’d made on the family Bible on my last birthday. With Gran, Aunt Lucy and my seventeen-year-old sister, Katie, as witnesses, I’d placed my hand on the worn leather cover and sworn to protect the Underground. To keep its work secret. To continue our family’s legacy, begun during the Civil War, of aiding the helpless and abused.

Killing Dr. Porter could betray us all.

Missy would surely be blamed for the murder, but a police investigation might expose the Underground, forcing our network of safe houses to shut down. Jeopardizing the women we were supposed to be helping.

In the space of a heartbeat, reason supplanted rage. Or, at least, controlled it. But part of me still lusted for a small measure of revenge. That, as much as the desire to escape town unimpeded by Dr. Porter, inspired me.

I ordered him to strip.

Without the tailoring of his suit coat to hide it, the curve in his back and the hunch in his shoulder were even more obvious. But I felt not a moment of sympathy for this hateful, ordinary man.

There were two large crystal water pitchers in the buffet. I made him fill them before he took Missy’s place on the kitchen stool, then kept my grandfather’s gun pointed squarely at him as I demanded that he drink both pitchers dry. And I watched, unmoved, as he gagged in his haste to please me.

“I’ll be right back,” I said and had no problem matching the menace I’d heard in his voice. I simply imagined the way he’d spoken to Missy hours earlier. “If you move from that stool or if you mess yourself—” I stepped behind him, pressed the tip of the gun against the bare flesh where his spine twisted just below his shoulder blades “—you will be punished. I swear.”

Then I backed out of the kitchen.

The engine was running and Katie had just crawled over into the passenger’s seat when I yanked the van’s driver-side door open. I climbed inside, dropped the purse that concealed my grandfather’s gun on the floor between me and Katie, and glanced over my shoulder.

Gran was seated behind me. An empty row separated her from Missy, who huddled into the corner of the bench seat at the very back of the boxy van. There was more metal frame than window there—a comforting location for someone who wanted to hide.

I flashed a smile at my grandmother and my sister. Success, I thought. My very first solo extraction for the Underground and everything had gone right. Before long, our van would blend into the heavy interstate traffic moving away from the St. Louis metro area. Away from Dr. Porter.

I couldn’t help feeling a bit self-satisfied. Within hours, Missy would be tucked into one of the guest rooms at the Cherokee Rose Hotel, our family home. Our family’s business. Within days, she would continue her journey along the Underground network, moving from one privately owned hotel or bed-and-breakfast to another until she reached her final destination. There, she’d be given a new identity, a job and a safe place to live. And we’d arrange for her children to be snatched from their father and returned to her.

Before I could pull away from the curb, Katie tugged at my arm.

“Where are the little boys?” she said urgently.

“They weren’t at home,” I said simply.

“So she just abandoned them?”

Katie made no effort to keep her voice down or to disguise her outrage. And there was no doubt that what she said carried clearly because Missy began sobbing.

I looked over my shoulder in time to see her struggle up from her seat, move forward past the empty row of seats, reach for the handle that opened the van’s side door. Then Gran’s hand darted out and I saw the sinewy muscle beneath her leathery skin flex with effort as her long, bony fingers caught Missy’s wrist and held it captive.

A fit, lean sixty-three years old, Gran was undoubtedly strong enough to force Missy back into her seat. But that would turn a rescue into a kidnapping and we, like Dr. Porter, would be denying Missy control of her own life. If her life was to change, Missy had to make her own decision.

The van was already running, so I shifted it into Drive. But I kept my foot on the brake, my hands on the steering wheel, and my attention split between the rear of the van and the front door of the Porter home. I couldn’t help wondering how long fear would control Dr. Porter’s fury, how long he would remain where I’d left him.

A frozen eternity passed as Gran simply looked at Missy, her expression one of utter sadness. She shook her head slowly and I knew that the intensity of her pale blue eyes would be magnified by the thick lenses she always wore. She lifted her hand away from Missy’s hand as she spoke. Missy leaned forward just enough to grasp the door handle but she didn’t pull it.

“You did what you had to do, Missy. You escaped,” Gran said. “You’re no good to your children if you’re dead. Or horribly injured. We have to get you to safety. First. Then we’ll get your babies back.”

Tears were streaming down Missy’s cheeks, but she nodded. Maybe it was the strength of Gran’s voice and the utter conviction of her words that returned Missy to her seat. Or maybe it was the sight of her husband—red-faced, barefoot and dressed only in his trousers—emerging from the house. He saw the van and raced across the lawn toward us.

I pulled away from the curb and the tires squealed as I floored the gas pedal. Inside the van, my passengers huddled down in their seats. Outside, Dr. Porter stood screaming obscenities in a cloud of exhaust smoke. There was nothing he could do to bring his wife back except, perhaps, call the police. But then he might have to explain why she’d fled. And I doubted he’d want to do that.

I rounded a corner, putting Dr. Porter out of sight. Another stretch of residential street, another quick turn, and I joined the heavier traffic on a main thoroughfare and headed for the interstate.

A glance in the rearview mirror briefly revealed Missy’s blotchy, tearstained face. Then she covered her face with her hands. I changed lanes, then checked the mirror again, seeking Gran’s eyes. But I was distracted by a quick movement beside me as my sister turned back around in her seat to stare at Missy. Her golden hair framed a face twisted ugly with anger. Her hazel eyes were narrowed, and her full bow lips were pressed into a tight line. Then she opened her mouth.

“Hey, you! Missy Porter!” she said, her usually soft, breathy voice sounding tight.

Certain that she would say something we all would regret, I reached quickly for the dashboard, cranked the volume setting on the radio up to maximum and turned on the power. Noise blasted through the van’s interior and drowned out Katie’s shrill yelp as I pinched her hard.

“Behave,” I mouthed as she jerked her head in my direction.

Katie surprised me by doing as I said. She faced forward again, sat rigidly with her hazel eyes fixed on the view out the front window. The muscles along her jaw flexed as she gritted her teeth.

I reached out again and dialed the radio down several notches.

“Sorry,” I said loudly in no one’s direction.

Then I fiddled with the controls until I found a country-western station where Toby Keith was singing something bawdy. The song was just loud enough to cover a front-seat conversation.

“What’s wrong with you?” I said to my sister once both of my hands were back on the steering wheel. “You don’t have any reason to be mean to her. You weren’t inside that house, didn’t see what she had to endure. She didn’t have a choice.”

“Oh, yes, she did,” Katie hissed. “She could have stayed with her children. Protected them. That’s what a good mother is supposed to do. Isn’t it?” And then more urgently, she repeated: “Isn’t it?”

That’s when I realized that she wasn’t really talking about Missy Porter.

“This is different,” I said. “Missy’s not like her.”

Eleven years earlier, our mother had left us alone with a stranger. Just for a little while. While she got a fix with the money he’d given her. She didn’t bother asking him what the money was for, didn’t wonder about his generosity.

When he began touching me, Katie had attacked him with teeth and fists.

“Get Momma!” she screamed as I broke free.

I ran as fast as I could. I searched for our mother in all the places I knew. The alley. The street corner. The bar at the end of the block.

I couldn’t find her anywhere.

So I did what she said we should never do. I found a cop and showed him where we lived.

I took him into our building, dragged at his hand so he would hurry, hurry, hurry. I told him to ignore the roaches and, instead, to concentrate on not falling through the traps that Momma and her friends had cut into the stairs and in the upstairs hallway. To keep the police from sneaking in and throwing everyone in jail.

Momma had said that the police put children in jail, too. But I didn’t care. Because even then I knew there were far worse things.

I’d brought help as fast as I could, but the stranger had already gone.

He hadn’t left right away.

Briefly, I looked away from the traffic, reached across the front seat of the van and covered Katie’s hand with mine. Our eyes met, and the smile that passed between us was sad and full of memory. And though I was sixteen and old enough to know better, I wished that I could go back in time. Wished for a chance to run faster, to find a cop sooner, to be brave enough to stay and fight by Katie’s side. I wished for a chance to save my sister just as she’d saved me.

Gran always said to be careful what you wished for.

Chapter 1

Eight years later

Lust.

That’s what any thought of Chad Robinson’s muscular six-foot-two frame, copper hair and green eyes inspired. The sound of his deep voice with its down-home drawl inevitably notched lust up another level, pushing almost-nostalgic warmth in the direction of aching desire. Not a particularly good way to feel about a man I was determined not to fall back in love or in bed with.

So when I answered the phone on a hot, humid evening in mid-June and heard Chad’s voice on the line, I kept my thoughts focused on the business at hand, not the memory of his hands. It was a good strategy for ex-lovers who were determined to remain friends.

In the time it had taken me to cross the kitchen and lift the cordless phone from its cradle, Chad had apparently been distracted from his call. When I put the phone to my ear, he was already speaking to someone in the background.

“Yeah. Good idea. The water gets pretty deep in those ditches. As soon as Brooke and her search dog are headed this way, I’ll take the southbound stretch and do the same….”

“Hey there,” I said by way of greeting, personal issues abruptly irrelevant as the snatch of conversation hinted at the reason for his call. “What’s going on?”

Chad’s attention returned to the phone.

“We’ve got a missing toddler, Brooke. Family lives northwest of town. The forest is right in their backyard. I checked the map. The house is in Maryville jurisdiction.”

As a deputy sheriff for Hardin County, Chad usually patrolled the southern Illinois towns of Humm Wye, Peters Creek, Iron Furnace and everything in between. When no cop was on duty in Maryville, his patrol looped a bit farther south to include the town where the two of us had grown up. Undoubtedly, that had happened tonight. Because, at the moment, Maryville’s entire police force was off duty and standing barefoot in the middle of her kitchen, considering dinner possibilities.

Chad gave me directions that started at the intersection of two meandering county roads. From there, he described his location in tenths of a mile and natural landmarks.

“How fast can you and Possum get here?” he said.

Away from the bluffs of the Ohio River, where the original town had been built, Maryville’s ragged boundaries were created by fingers of human habitation jamming deep into the vast Shawnee National Forest. I lived at the tip of one of those fingers. The missing child’s home was on another, in an area of expensive, very isolated homes. Even with four-wheel drive and a native’s intimate knowledge of the area’s back roads…

“I need half an hour,” I said, then asked him for details.

With the receiver held between my ear and shoulder, I listened to him talk as I walked halfway down the hall to my bedroom. There, I snatched a pair of jeans and a long-sleeved denim shirt from the closet. Though the T-shirt and cutoffs I’d changed into when I’d gone off duty were more appropriate to June’s hot and humid weather, they were poor protection against branches and thorns. I wasn’t even tempted to change back into my uniform. Maryville’s budget paid for one replacement uniform annually. Not quite a year as a rookie cop in the town’s newly created one-person department, and I was already out-of-pocket for two uniforms.

But uniform or not, and although Chad was the responding officer, the location of the house meant that I was not just a searcher, I was also the police officer in charge. So I began gathering the information I needed for both those roles as I exchanged shorts for jeans and slipped the long-sleeved shirt over my T-shirt. I clipped my shiny Maryville PD badge onto the shirt’s breast pocket.

“When the call came in, I had dispatch contact the forest service and pull some rangers from the Elizabethtown district office,” Chad said. “They’re searching the immediate area.”

“You’ve already searched the house?”

“Yep. First thing,” Chad said matter-of-factly. “Every room, every closet, behind the furniture and under all the beds. I checked the garden shed and the garage, too.”

I nodded, pleased by the information. All too often, cops and inexperienced searchers focused their attention on searching areas beyond the house right away, only later discovering a lost child fast asleep in a closet or in the backseat of the family car. Or, more tragically, overcome by heat in an attic crawl space.

“The parents are sure Tina’s wandered off,” Chad continued. “That’s her name. Tina Fisher. Did I tell you she’s four years old? The parents have been searching for her since sunset. Sure wish they’d of called us right away.”

But they hadn’t, which was typical.

Chad provided me with a few more sketchy details as I re-crossed the kitchen, snatched two bottles of lime-flavored Gatorade and a handful of granola bars—tonight’s dinner—from refrigerator and pantry. Then I moved my shoulder to hold the phone more securely against my cheek as I sat down on a wooden bench by the back door and laced on a pair of oiled-leather hiking boots.

From his nearby cushion, my old German shepherd, Highball, wagged his tail and woofed twice, ever hopeful that when I put on boots it meant playtime for him. But Highball was too old for this kind of search. Too old, really, for any kind of search.

“Brooke? You still there?”

“Yeah,” I said slowly. “Give me a minute….”

I spent that minute trying to figure out if I was seeking feedback from a cop far more experienced than I, one who’d been on the force for three years and in the military police before that. Or if I was simply looking for the kind of reassurance that only an old friend or an ex-lover can provide. In the end, I gave up on sorting it out and simply blurted out what was on my mind.

“What’s your feeling on this one, Chad? Do you think she’s really lost?”

It was his turn to hesitate. And I suspected that he, too, was recalling a cool day in early spring more than a year earlier. Back when I was still a civilian, when the county police force knew me as that gal who helped out when folks got lost. Or maybe as the gal that Officer Robinson intended to marry, if only she’d get around to saying yes. Back then, I already suspected that the only possible answer I could give Chad was no. But I still hoped that when folks said that love conquered all, those conquests might include guilt and deception. The reality was, love couldn’t stand up to either.

Anyway, on that particular spring day, Highball and I had been called in to look for another missing child. Possum was still more puppy than adult, and the older dog had always been a marvel at in-town searches, capable of ignoring the distractions of traffic and onlookers and the confusion of scents.

We found the body near a sagging post-and-wire fence that did a poor job of separating a run-down trailer court from a field that was shaggy with the remains of last year’s corn crop. The two-year-old boy was wrapped in his favorite blanket and buried beneath a pile of damp, winter-rotted leaves nearly the same color as the blood that crusted his hair.

I helped Chad stretch yards of yellow plastic tape from one tree to the next. CRIME SCENE. DO NOT ENTER. Then I walked slowly back to the street where the little boy lived and stood on the curb, just watching, as the ambulance arrived.

Usually, when I found a missing person—living or dead—there was a moment of primitive glee, a flash of adrenaline-spurred triumph. But this time, as the paramedics loaded the tiny body into the ambulance, I could think only of the terrible loss. Then the rear doors were slammed shut and the ambulance pulled away without screaming sirens. Without haste.

The media was at the scene to cover the story of the missing toddler. Reporters and camera crews from papers and TV stations as far away as Evansville and Paducah trolled the crowd, hungry for one more detail, a unique angle, an award-winning photo, a bit of footage dramatic enough to make the national news. Desperate to avoid their prying eyes, I tugged Highball’s leash and quickly walked away. When the tattered gray trunk of a century-old sycamore was between me and the media, I stopped, dropped to my knees and buried my face in the thick fur of my dog’s ruff.

I thought I was safe, so I wept. But within moments, voices—urgent and demanding—surrounded me, and I feared that my private tears for a dead child would make someone’s news story complete. Then, unexpectedly, Chad was there. He hunkered down beside Highball and me and wrapped his arms around both of us. His snarled commands had kept the reporters at bay.

Now, another young child was missing.

I stood by the back door, looking out its window, waiting for Chad’s reply.

“I don’t know, Brooke. I really don’t. The parents seem real upset, but…”

His words trailed off as he left unspoken the reality we both understood. Upset parents didn’t mean that one of them hadn’t murdered their child.

I sighed, fingered my badge for a moment. My job no longer ended with the rescue or recovery of a victim. If Tina was dead, my responsibility was to find out how and who and maybe why. Any tears would have to wait.

“Finding Tina is a priority,” I said. “But if you haven’t already told them, would you please remind the rangers that we could be dealing with a crime? If they find the child dead, tell them not to move her body. I know they’ll have to check for vitals. But after that, they need to back off and leave the scene as undisturbed as possible. And Chad, maybe assign one of the rangers to sit with the Fishers. Call it moral support, but don’t let them do any cleaning up that might impede a murder investigation, okay?”

In all likelihood, Chad didn’t need me to tell him any of that, either. And I understood that, whether they knew what to do or not, a lot of seasoned male cops would have resented taking direction from a female and a small town’s rookie police officer. But Chad and I had never had a problem where our professional lives were concerned. When I’d first pinned on a badge, we’d worked out the ground rules. Almost a year later and, despite the recent upheaval in our personal relationship, those rules and our friendship still worked.

In this situation, the rule was simple. My jurisdiction. My responsibility. Chad apparently also remembered the rule and responded accordingly.

“Will do,” he said. “Another county cop is on the way to back me up, so I’ll have her keep an eye on the parents. Anything else?”

“I don’t think so,” I said, my tone inviting feedback.

Apparently, Chad had no advice to give.

“Then see you soon,” he said and disconnected.

Out in the kennel area and seemingly oblivious to the heat, Highball’s replacement was bouncing around on the other side of a six-foot-tall chain-link fence and barking up a storm. The young dog’s excitement was most likely prompted by one of his namesakes searching for grubs in the woodpile.

“He walks like an old fat possum,” Gran had observed as my new German shepherd puppy waddled his way across the room to greet her. And though he’d grown up to be a graceful and athletic dog, the undignified nickname stuck. Possum.

I turned away from the window to pick up a powerful compact flashlight from the far corner of the kitchen counter. Everything else I needed, including my webbing belt and its assortment of small packs, was already in the white SUV that doubled as Maryville’s only squad car and my personal vehicle. That was a fairly standard arrangement for small-town police departments.

Customizing the SUV to accommodate a dog wasn’t. But the city council members had observed that my volunteer work to locate the lost, complete with search-and-rescue dogs, was just as important to the citizens of Maryville as the job they’d now be paying me for. So the modifications to the SUV had been made, and I’d been grateful.

“Come on. Kennel time,” I murmured to Highball.

His kennel area was outside, adjacent to Possum’s, and going there always meant a meal. Or a treat. And a tennis ball to chew on. Highball raised his graying head, rose slowly to his feet and wagged his tail as he joined me at the back door.

I pulled a ball cap over my cropped brown curls, then reached into the stoneware bowl on the kitchen counter and snatched up the keys to my squad car.

I was ready to go.

The Fishers lived on top of a rise in a modern, two-story log home, deliberately rustic and heavy on the windows. Out front, a low fence of flat river rock enclosed the yard and lined the approach to the house.

When I pulled into the drive, I saw Chad on the front porch, uncomfortably perched on the front edge of an Adirondack chair and leaning over a low wooden table. He was in uniform, which was short-sleeved and dark blue, but had set his billed cap aside, exposing crew-cut coppery-red hair. Thousands of insects swarmed around him, attracted by the yellow glow of the light mounted above the door. His attention was so completely absorbed by whatever was on the table that he seemed oblivious to them.

I turned off my headlights, cut the engine and sat for just a moment.

In my rearview mirror, I could see flashlights bobbing—rangers searching through the cattails and tall rushes growing in the swampy ditch that paralleled the road at the front of the property. The only other illumination in the area shone from the windows of the Fisher family’s home, where all of the interior lights seemed to be on.

I climbed down from my SUV and walked around to the back to lift the door of the topper and drop the tailgate. From inside his crate, Possum whined excitedly, eager for the search.

“In a minute,” I said, and he settled back down.

I pulled the items I needed from the bed of the truck and sprayed myself with insect repellent. My utility pack was on a webbing belt. I slung it around my waist, tied my two bottles of sports drink into the pack’s side pockets, and slipped my flashlight through one of the belt loops. A canteen of water for Possum was added to my load, along with a small, folded square of waterproof fabric that cleverly opened into a water dish. I took a pair of two-way radios from the locked box near the tire well. One, I’d leave with Chad. The other, I clipped to my belt.

Then I released Possum from his crate.

He jumped down from the bed, mouthed my hand briefly in an affectionate but sloppy greeting, then stood with his tail wagging and his body wiggling. For him, searching for a missing person was the ultimate game of hide-and-seek, its successful conclusion rewarded by the praise he craved.

I bent down to clip a reflective neon collar with a dangling bell around his neck, then slipped a reflective orange vest over his head and secured the belly straps. The lettering and large cross on each side of the vest proclaimed Possum’s status, RESCUE DOG. Then I stood and, with Possum at my heels, joined Chad.

He was concentrating on using a ruler and a narrow-tipped red marker to extend a line on a topographical map. Tomorrow, I knew, the grids that he was drawing would be used for a more comprehensive search. If I failed to locate the child, a full-scale ground search would be organized and mounted at first light.

“Sure hope we won’t be needing this,” I heard him murmur as I stepped in beside him. Briefly, I rested my hand on his shoulder in greeting, then leaned in closer to get a better look at the map.

He finished the line, turned his head, smiled up at me. And I tried not to think about how much I still loved him.

“Hey there, Brooke,” he said. “Thanks for coming.”

Tina Fisher was wearing pink.

Pink cotton slacks. A T-shirt printed with pink bunnies. Pink barrettes in her straight blond hair. Her shoes were pink, too—rubber-soled Stride Rite leather sneakers—and they were gone. Maxi was also missing, and Tina’s mother explained that the bedraggled, one-eyed teddy bear was Tina’s constant companion.

The Fishers stood close to each other as they spoke. Her hand periodically moved to pat the hand that he’d rested on her shoulder. When I asked when they’d last seen Tina, Mrs. Fisher’s composure crumbled. She turned and smothered her sobs against her husband’s chest.

“It’s all my fault,” I heard her say. “I should have watched her more closely….”

Mr. Fisher wrapped his arms around her, then looked over her shoulder at me.

“Can you give us a minute?” he asked.

I nodded.

“No problem,” I said.

And I meant it. As a searcher, I was pressed for time. But as a cop, I welcomed the opportunity to take a long, hard look at the pair. To add my perceptions to what Chad had already seen. To begin building my case should lost turn out to be murdered. It would be my first murder investigation, and I wanted to do everything by the book. As I’d been taught.

“Your instincts about people are better than mine,” Chad had said before he opened the front door and waved me inside ahead of him. “They claim the little girl wandered away while they were fixing dinner. The more time I spend with them, the more I’m inclined to think they’re telling the truth. But see what you think.”

Just inside the door, I’d spent a moment glancing around the first floor. The interior and its country-chic furnishings confirmed what the exterior had suggested. The house was modern and expensive. Living, dining and food-prep areas blended seamlessly in an open floor plan, and I’d wondered how a small child could have wandered away unnoticed by either parent. Then I’d reminded myself that children were fairly adept at doing just that kind of thing.

Mr. and Mrs. Fisher had risen from a clean-lined, cocoa-colored sofa as Chad and I had entered the living area. Chad had made quick introductions, then he’d gone back outside. A young woman in a uniform that matched Chad’s had been listening from a nearby easy chair. She’d acknowledged me with a quick nod, then excused herself to make coffee, leaving me alone with Tina’s parents.

I’d acted like a volunteer, not a cop, kept my voice sympathetic and my tone unaccusing. But still, my gently asked questions had reduced Tina’s mother to tears.

As his wife buried herself in his arms, Mr. Fisher half turned so that his broad shoulders sheltered most of her upper body from my view. Then he pressed his lips to the top of her head. Which still left me plenty to look at.

They were both lean and blond and had narrow noses, even white teeth and golden tans. Each wore short-sleeved designer-label knit shirts—his white and hers pale pink—over khaki shorts and athletic shoes designed for a fitness-club workout, not trekking through rough terrain. But their appearance made it clear that they had, indeed, been in the woods. Their clothing was grubby and perspiration-stained and their shoes were streaked with grass stains. Socks, which he wore and she didn’t, were hung with burrs and her ankles were raw with mosquito bites.

Tina’s mother and father were also both bloodied by the wild roses and raspberries that invaded sunny boundaries between cultivated yards and the forest. Away from tended trails, their whiplike branches were difficult to avoid, especially if one wasn’t paying attention to them. The couple’s bare arms and legs were crisscrossed with long, thin scratches, and a tear on the back of Mr. Fisher’s shirt still had a few large thorns embedded in the ragged fabric.

I tipped my head, considered the possibilities. Hope and instinct supported Chad’s assessment—ignoring their own welfare, Mr. and Mrs. Fisher had searched frantically through the nearby woods for their missing child. Missing because she’d wandered off, or because some human predator had exploited an unlocked back door or an untended child in the yard.

Bitter experience suggested an alternate scenario. Tina was murdered in the house and one or both of her parents had been so intent on hiding her body that physical discomfort was irrelevant.

“Please, honey,” the husband was saying, “don’t do this to yourself. I didn’t know she’d figured out how to unlock the back door. Did you?”

“No,” came his wife’s muffled reply. “But she’s smart.”

“Yes, she is. So she probably went outside and saw a butterfly or a bunny and followed it into the woods. Nobody’s fault. So now, what we need to do is help Officer Tyler find her. Okay?”

“Okay,” she sobbed.

A moment later, still remaining within the circle of her husband’s arms, Tina’s mother turned her tearstained face back in my direction.

“I’m sorry,” she said, still sniffling but once again coherent. “What else do you need to know?”

I shook my head.

“Nothing else. But I do need a piece of Tina’s clothing. Something she’s worn recently. That hasn’t been washed. Like socks. Or pajamas. Or underwear.”

“I’ll get it,” she said eagerly.

As she scurried into a nearby room, I opened the small, unused paper sack I’d carried with me into the house. When Mrs. Fisher returned, she had a pair of socks clutched in her hand. They were pink, ruffled at the cuffs and obviously worn.

“Thanks,” I said, dropping the socks into the sack.

With the Fishers in tow, I walked to the front porch where I’d left Possum waiting. With my body propping the door open, I held the open bag at his level. He nosed the fabric, memorizing the scent of this particular human being.

“Possum, find Tina,” I commanded.

As I tucked the sack into one of the exterior pockets of the search pack, Possum trotted past me to nuzzle each of the Fishers, his tail moving in a rhythm that I recognized as concentration. They stared, unmoving, probably unbelieving, as Possum walked past them and into the house.

“Possum’s comparing your scent to Tina’s, sorting Tina’s smell from yours,” I explained. “Now he’s following Tina’s scent.”

“Why doesn’t he keep his nose on the floor?” Tina’s father asked.

“Sometimes he does, but mostly he picks up scents carried by air currents. When you’re searching for someone who’s lost, it’s more efficient not to have to follow the—”

I caught myself and didn’t say victim. But the truth was that Tina was in terrible danger.

“—Tina’s exact route.”

Even without the possibility that her parents were involved in her disappearance, there were plenty of deadly natural hazards in the deep forests, wooded ridgetops, steep rocky slopes and narrow creek bottoms of the ancient Shawnee hills. And there was also the possibility that she’d never entered the woods, that she’d ended up somewhere along the road and a human predator had happened by at just the wrong moment.

I dragged my mind away from that bleak train of thought, concentrated instead on Possum’s progress through the house. He circled the living room, then headed upstairs, with me and the Fishers at his heels.

“But Tina’s outside,” the mother said, her voice traveling in the direction of despair.

“Don’t worry,” I said, knowing that Possum was seeking the place where Tina’s scent was most heavily concentrated. “He knows his job.”

With four rooms to choose from at the top of the landing, Possum made a beeline into a bedroom where the wallpaper was decorated with intertwined mauve flowers. He went directly to the twin bed, nuzzled the pillow and a wad of soft blankets, then wagged his tail.

Easy enough to guess that the room belonged to a little girl, but I made sure.

“Tina’s?”

The mother nodded and the father didn’t look as panicked as he had just moments earlier.

Possum emerged from the bedroom.

“Good boy,” I said. “Find Tina.”

Possum went back downstairs, pushed his way beneath the dining table and nosed several stuffed toys that were gathered around a plastic tea set, then made his way quickly and very directly to the nearby patio door. He scratched at the glass and whined.

“That’s the door we found open,” the father said, sounding as if he’d just witnessed magic.

I told the parents to wait in the house as I opened the door wide for Possum. With little more signal than a half wag of his tail, he crossed the deck, negotiated a set of shallow steps and then angled across the lawn toward a split-rail fence separating the backyard from the forest. Easy enough for Possum—or a small child—to slide between the rails. I climbed over, staying just behind my dog as we crossed the brushy perimeter separating the yard from the deeper shadows of the woods.

Before we plunged into the undergrowth, I switched off my flashlight, giving my eyes a few moments to adjust to the darkness that confronted us. Then I breathed a quick prayer asking for guidance for my feet and Possum’s nose. And protection for the child.

Chapter 2

Mosquitoes.

I couldn’t see them, but their high-pitched whine was constantly in my ears. They swarmed around me, a malevolent, hunger-driven cloud on the humid night air. Time was on their side. Trickles of salty perspiration would soon dilute the repellent I wore. Then they would feed.

I was used to itching.

Ticks.

The forest was infested with them. Sometimes, they were a sprinkling of sand-sized black dots clinging to my ankles. Often, they were larger. I carefully checked for them after every foray into tall grass or forest, pried their blood-bloated bodies from my skin with tweezers, and watched for symptoms of Lyme disease.

Ticks, too, were routine.

Spiders.

Their webs were spun across every path, every clearing, every space between branch and bush and tree. A full moon would have revealed a forest decked with glistening strands—summer’s answer to the sparkle of winter ice. But the moon was a distant sliver, weak and red in a hazy sky, and I found the webs by running into them. The long, sticky wisps clung to my face, draped themselves around my neck, tickled my wrists and the backs of my hands.

I’d feared spiders since childhood, remembered huddling beside Katie as a spindly-legged spider lowered itself slowly from a cracked and stained ceiling. Back then, I’d pounded on that locked closet door, screaming for my mother to please, please let us out. Maybe she hadn’t heard me or maybe she simply hadn’t cared. But now, with each clinging strand I brushed away, I imagined the web’s caretaker crawling on me, just as the spider in the closet had. I wanted to run from the forest, strip off my clothes, scrub myself with hot water and lye soap.

Of course, I didn’t.

I ignored the silly voice that gibbered fearfully at the back of my mind and concentrated on following Possum, guided mostly by the reflective strip on his collar. Periodically, I paused long enough to take a compass reading or tie a neon-yellow plastic ribbon around a branch or tree trunk at eye level. The markers would enable me to find my way out. Or help Chad and his people find their way in. Sometimes I spent a minute calling out to Tina and listening carefully, praying for a reply.

She didn’t answer.

When I wasn’t shouting Tina’s name, the only sounds besides my breathing and the crunch of my footsteps were Possum’s panting, the tinkle of the bell on his collar and his steady movement through the brush. Overhead, the canopy of trees thickened, almost blocking the sky. Night wrapped itself around us like an isolating cocoon, heightening awareness and honing instincts. Ahead, the inky blackness was broken only by the erratic flash of fireflies that exploded, rather than flickered, with brightness. Behind us, humans waiting beneath electric lights became distant and unreal, irrelevant to the search.

Possum picked up the pace, moving steadily forward, detouring only for tree trunks and the thickest, most tangled patches of roses and raspberries. I struggled to keep up with him, knowing that calling him back or slowing him down risked breaking his concentration.

I ignored the thorns I couldn’t avoid, dodged low-hanging branches, skirted tree trunks and stepped over deeper shadows that marked narrow streams, twisted roots and fallen trees. Sometimes I used my flashlight, running it over the ground to judge the terrain ahead. Always, I paid for that indulgence with several minutes of night blindness, and I didn’t turn the light on often.

As I made my way through the forest, fragmented thoughts of Tina—fragmented bits of hope—floated to mind. Maybe we’ll find her easily. She’ll be tired and cranky and mosquito-bitten, but okay. She’ll be okay. Possum and I will take her back to her parents. To the parents who love her. Who would never harm her. She’ll be okay. We’ll find her, and we’ll go home. I’ll take a hot shower and have a cold beer. Possum can have a dog biscuit. Maybe two. If we find Tina. Alive.

Ten minutes later, Possum’s pace slowed.

He wavered, whined and stopped. He had lost the scent. A more experienced search dog, like Highball, would have known what to do next and done it. But Possum was still young and not always confident.

I hurried to his side and gave him a brief, encouraging pat, then checked him for signs of heat stress. Youth had its advantages—he was doing fine. Then I pulled Tina’s socks from my pocket. When I held the bag open for Possum, he sniffed the fabric again, lifted his head, put his nose in the air, and wandered in an erratic little circle. He whined again, definitely frustrated.

I oriented my body slightly to the left and pointed.

“Go on,” I said. “Find Tina.”

Possum followed my direction. I counted ten, slowly. When nothing about the dog’s movement hinted that he’d rediscovered Tina’s trail, I called him back. Then I turned to the right and sent him off that way.

Still nothing.

I moved forward several yards and we repeated the process. Left, then right. On each sweep, I sent Possum farther away from me. After that, he needed no direction and followed the ever-expanding pattern on his own. The night was still and humid—bad search conditions for any air-scenting dog. And although he was fit, Possum’s heavy coat made him susceptible to the heat. If he didn’t pick up the trail soon…

Patience, I told myself. Patience.

Minutes later, Possum rediscovered a wisp of Tina’s scent. His ears pricked, his tail wagged and his pace suddenly became faster and more deliberate. He continued through the woods with me at his heels.

Between the darkness and the terrain, it was difficult to know how far we had gone. I knew where I was, generally. Knew that I could turn around and find my way back to the Fishers’ house. But, at the moment, the physical landmarks that were so clearly marked on Chad’s map had little to do with the reality of the forest.

Possum’s collar disappeared. And didn’t reappear.

I could still hear his bell, so I assumed he was simply blocked from my view. I hurried forward, not considering what I wasn’t hearing—the sounds of his movement through the brush.

A spider’s web, strung between two trees at shoulder level, probably saved my life. I walked into it. And somehow noticed that, rather than trailing back over my neck and chin, the strands tickled my cheeks and nose, driven by the slightest stirring of upward-moving air. I stopped in my tracks, heart pounding from a sudden rush of adrenaline, my body sensing danger before my conscious mind registered it.

I switched on my flashlight and, with hands trembling from reaction, aimed it two strides forward. And down. A long way down. Maybe forty or fifty feet. I’d nearly stepped off a soil-covered outcrop of crumbling limestone, nearly tumbled to the stream bed below. Now that I was standing still, I could hear moving water.

The seeping groundwater that fed the stream had carved deep scars into the ravine’s limestone walls. Horizontal fissures marked places where softer rock had been washed away between layers of less porous stone. Soil had collected on the exposed ledges, creating islands of ferns and a network of slippery, narrow paths. In some places, water-weakened towers of limestone had sheered away from the walls, taking mature trees down with them. Everywhere, shattered trunks and branches were wedged across the ravine, creating a crisscross pattern of rotting and overgrown bridges.

I told myself that Tina had not fallen into the ravine. I told myself that Chad was right—that my instincts were good—and that no human monster had abused and then discarded her over the edge.

Possum’s bell jingled in the distance, and my flashlight beam made his collar glow. He had entered the ravine south of where I stood and was moving back in my direction, moving steadily along a ledge that would eventually put him six feet below me.

Just a few steps away from me was a tree that leaned precariously over the ravine. An old cottonwood whose trunk was probably seven feet around. There was a ragged hole in the trunk, partially obscured by vines, that narrowed to a point at the height of an adult’s waist. The wider opening at the base was just large enough that it might look inviting to a child seeking shelter. I got down on all fours and bent my elbows to peer inside the dark scar, hoping to find Tina curled up asleep. Safe. And discovered that eroding soil, crumbling limestone and twisted roots had created a natural chute inside the rotting trunk. A chute that would send a body downward…

I wrenched my light away from the interior, aimed it over the nearby precipice. A tapering curtain of long, thick tendrils hung directly beneath the old tree, the longest of them trailing down to the narrow ledge below.

Impossible to see what those roots might be hiding.

“Tina!” I called urgently.

The slightest echo of my own voice answered me.

She might be lying there unconscious. Or sleeping. She might not be there at all.

The slope beside the tree was steep but not absolutely vertical.

I checked the ledge carefully for signs of her as I considered my strategy. I could walk along the ravine’s edge until I found a place where I could climb down more easily. That would take time and I risked losing sight of Possum, but I’d probably not fall and break my bones. Or I could climb down right here, using the strongest of the tree roots to slow my descent.

I put one hand on the cottonwood for balance and leaned way out into the darkness. Four feet below the first ledge was another jutting outcropping that was at least double the width of the one immediately beneath me. If I could make it down to the first ledge, it was an easy jump to the next one. If I slipped and tumbled past the first ledge, the second one would be my safety net, though reaching it that abruptly was not part of my plan.

And from there? I asked myself. Too easy to imagine me sitting, stranded and broken-limbed, suddenly needing rescue myself. Embarrassing and certainly not helpful to Tina. Especially if she wasn’t even down there.

Air currents in and around ravines are complex, I reminded myself. It was impossible to know if the scent Possum was following was actually directly below me. Or upwind. Or maybe, though unlikely, drifting from the opposite side of the ravine. Common sense overcame urgency, and I decided to spend a few extra minutes searching for a safer way down. I played the light around my feet, taking one last, close look at the terrain before turning off my flashlight.

That’s when I saw the shoe print.

It was tiny, rounded at the toe and angled into the soft earth between two thick roots. The words Stride Rite were lightly embossed into the soil.

That changed everything. Now I knew, without doubt, that Tina had been here. Standing. Walking. Impossible to know if she’d been accompanied or alone, but at the moment she’d stepped next to the tree, Tina had been alive.

And in the next moment? I asked myself. I grasped for hope, for some thought that didn’t involve Tina climbing inside the tree and then tumbling down into the darkness. Or being pushed…

But Possum was intent on working his way down into the ravine.

Trust your dog. That was a fundamental rule of canine search-and-rescue work.

I radioed Chad, told him what I’d found and where I was going, and asked him to head my way. Now.

I spent another minute calling out for Tina and listening. Cicadas shrilled. Mosquitoes buzzed. Frogs trilled. But besides the sound of my own breathing, I heard nothing human. So I climbed down into the ravine. With my belly pressed against the crumbling edge, I controlled my descent by wrapping one hand around one of the thicker exposed roots, then digging the fingers of my free hand and the toes of my boots into the limestone wall. My passage triggered a miniature avalanche of pebbles and soil that poured down on my feet when I landed on the narrow ledge.

It was a sloppy descent—unsafe, poorly planned and scary. But it got me where I needed to be. I shook the loose soil away from my boots, brushed the worst of it from my face and the front of my shirt, and retrieved my flashlight. Then, turning my back on the twisted mass of tree roots, I looked toward Possum.

Instead of rushing to greet me as I expected, he stopped just out of reach. He cowered, tucked his tail between his legs, turned his head and one shoulder away from me and whined.

He wasn’t reacting to me.

Only one thing triggered that posture in a search dog. Possum hadn’t been trained as a cadaver dog, but if death had laid its distinctive scent nearby, he would pick up that less familiar but still human smell and understand at some level what it meant.

I understood exactly what it meant.

My first thought was: Oh, dear Lord! The child is dead.

Then I caught myself. This was no time for the handler to fall apart. I pushed aside my feelings, ignored the painful tightening in my gut. I pressed my eyes shut as I took a deep breath and let it out slowly. When I opened my eyes again, my emotions were back under control. I could do what needed to be done.

Certainly, recovering Tina’s body was urgent. But now, comforting my dog was more important than that. It was up to me to make sure that he was rewarded for finding a victim, living or dead. So I went down on one knee and called Possum closer. I took his big head in my hands, put my cheek against his soft, warm muzzle and ruffled his shaggy fur.

“You’re a good boy,” I murmured. “A very good dog. You found her.”

Then I lifted my head and dug in my pouch for Possum’s favorite treat—bits of crisp, thick-sliced bacon. Almost absentmindedly, I fed him tiny pieces as I considered how air currents might move in and along a ravine. Upward, certainly. But eddies of air would form on each ledge, creating pools of scent that might not have originated there. When Possum reacted, there’d been nothing visible between him and me but bare soil and a few maidenhead ferns growing from tiny cracks in the limestone wall. So unless he had sensed particles of flesh or bone or drops of blood that were invisible to me—something that was possible but unlikely in this circumstance—the body was probably below us.

Before moving again, I took careful note of exactly where Possum and I stood and what we were disturbing. If this was a crime scene, our very presence was destroying forensic evidence, our every movement overlaying traces left by a killer with traces of our own. My priority was to find Tina, to recover her body. But after that, I wanted justice. More, I wanted the child’s death avenged. Which meant that I needed a crime scene that was as intact as I could leave it.

Possum finished up the last of the bacon.

I wiped my greasy fingers on my jeans, ran the back of my shirtsleeve across my eyes, then stood and played the flashlight’s beam along the ledge just below us. Visually, I divided it into grids, carefully checking each square. I saw nothing unusual. But below that barren outcropping, detail disappeared. Whole sections of the ravine were hidden by foliage and fallen trees. If Tina’s body was down there somewhere, there was only one way to find out.

But first, there was an area of the ledge we were on that had to be searched more thoroughly. Just in case. I poured Possum a dish of water, noticed that his tail was moving again, and knew that he would be okay. Then I turned, concentrating the flashlight’s beam on the cascade of roots obscuring the limestone wall.

Behind me, Possum moved.

In some detached part of my mind, I felt his nose press briefly against the back of my thigh, heard him jump down to the ledge below. But most of my attention was on a bedraggled toy bear caught among the first layer of roots. Mint-green with a white belly and an embroidered pink smile. Tina’s teddy bear, Maxi. One of Maxi’s fuzzy arms was nearly torn away and his single yellow eye reflected the light.

I knelt, squatted back on my heels and angled my body forward so that I could look into the dark cave beneath the tree without disturbing anything. My flashlight’s beam was broken and diffused, so I peered in closely, trying to penetrate the veil of roots and soil.

I saw a body.

Headless.

A tangle of trailing roots wove together a spine, rib cage and pelvis, holding them almost upright. On the ground beside the pelvis were the double bones of a forearm with a skeletal hand and a few finger bones still attached. Nearby, half buried by soil and debris, my flashlight’s beam revealed a cheekbone, a dark eye socket and the rounded dome of a fleshless skull. A creeping vine grew like a shock of curly hair through a jagged hole in the forehead.

Tears of relief blurred the grisly scene in front of me.

Not Tina. Thank God, not Tina.

An adult, long dead.

Then my stomach twisted at a sudden and uninvited notion. These bones were Missy Porter, come back to haunt me.

Angrily, I pushed aside the preposterous thought.

Don’t be stupid, I told myself. Though she was long dead, too, Missy’s body hadn’t been concealed within the cocoon of an ancient cottonwood. She would never be embraced by warm, dry earth. Her remains were entombed in steel, hidden where water tupelo and bald cypress sank roots deep into still, oily water. A place where black vultures, frogs and water moccasins were the only witnesses to human secrets.

I knew that because I’d put her there.

Possum barked and barked again.

A child cried out, and the sound was one of surprise rather than pain.

“Go ’way!”

The voice was slurred with sleep.

Yanking my thoughts away from remembered horror and my flashlight’s beam away from newly discovered horror, I directed the light over the edge of the ledge. Below me, all I could see of Possum was his enthusiastically wagging tail. The rest of his body was hidden by the overhang I was on.

“Stop dat!”

A child’s voice.

“Tina?” I called, and then louder, “Tina!”

“I want my mommy!” she said.

I climbed down to the next ledge with more haste than care. And found her.

She was sitting tucked back into a shallow cave that was little more than a depression in the limestone wall, yelling at Possum, pummeling my dog with tiny fists and sneaker-clad feet. Possum had stretched out beside the child, trapping her against the ravine wall. The more Tina struggled and flailed, the more Possum was determined to care for her, mostly by licking her face.

I called Possum to me, ruffled his fur, patted his head, told him he was a fabulous, wonderful, marvelous dog. His body wiggled with such enthusiasm that I briefly feared he might send us both toppling over the edge.

After a few moments, I pointed at a spot a few feet from the child.

“Now sit,” I said, “and stay.”

Tina added to the command sequence.

“Berry bad dog,” she wailed. “Berry, berry bad.”

I knelt beside her and pulled the teddy bear from my belt.

“Oh, no. Possum’s a good dog. Aren’t you, Possum? See, he found Maxi for you.”

Tina quieted immediately as she grabbed the teddy bear. She hugged the poor, torn thing to her chest and covered its grubby head with kisses.

Chapter 3

There was nothing to do but wait.

Too hazardous by far to carry Tina out, risking the narrow ledge that Possum had followed down into the ravine. Foolish and probably impossible to climb back the way I’d climbed down. Chad, I knew, was already on his way. And I admitted to myself that that was a comforting thought.

I looked at the luminous numbers on my watch, saw that Possum and I had been in the woods for just under two hours. Chad and his people, using my markers to find their way, would probably only take half that long to reach us. Though the nighttime temperature was probably still in the mid-eighties, the face of the ravine and the limestone outcropping were damp and cold. So I settled Tina onto my lap and wrapped my shirt around her. Possum curled in beside me and I was grateful for the additional warmth.

As I checked Tina for injuries, we chatted about teddy bears and big trees and missing bedtime and adventures in the woods. By the time I’d determined that Tina’s tumble down to the ledge had miraculously cost her nothing but a few scrapes and bruises, I’d learned most of what I needed to know. Maxi, it seemed, had gotten hungry, so he and Tina had gone into the woods looking for a honey tree. Just like in Winnie the Pooh. It had gotten dark. They’d walked and walked. And then they’d fallen down. Now Tina and Maxi were really, really hungry.

There was no honey for her that night, but the granola bar and lime-flavored sports drink I shared with Tina seemed to do the trick. We offered Maxi and Possum crumbs, which Possum ate with tail-wagging enthusiasm. Tina announced that her teddy bear judged the snack yummy. Then, with Maxi wrapped in her arms, she fell asleep.

I was tired, physically and mentally tired. But I stayed awake anyway, irrationally alert to the presence of predatory spiders on the ledge where we sat. More rationally intent on protecting Tina and listening for the sounds of approaching rescuers. When I heard them, I would aim my flashlight’s beam into the sky to mark our exact location.

In the meantime, I waited.

Time passed slowly in the dark. I held Tina, embracing her warm, soft weight and listening to her breathing. And though it seemed inappropriate to think anything but bright and beautiful thoughts with a successfully rescued child in my arms, my mind quickly drifted to the dark, dirty business of the skeletal remains on the ledge just above me.

“Did you walk into the woods with your murderer?” I murmured under my breath.

Possible, I thought, but it didn’t seem reasonable for a murderer to lure or force a potential victim very far from a road or a trail. Why travel all the way to the ridge when the forest offered adequate, plentiful and more convenient places?

I considered another scenario.

“Were you killed somewhere else, then carried here?”

I shook my head, immediately dismissing the idea. A body is awkward and heavy to carry. My mind veered away from the reason I knew that, and I focused on the idea that no one carries that kind of weight any farther than they have to.

Killing someone in this place made no sense, I told myself. Unless the murderer had chosen the particular spot, the particular tree, for reasons that only a disturbed mind could fathom. But after nearly a year in law enforcement, I had great faith in the human impulse to do things the easy way.

Then it hit me. The ridge simply wasn’t as inconvenient as it seemed. Unless you were searching for a lost child, there was no reason to approach it from the Fishers’ backyard, to crash through the underbrush or walk along deer paths that were easy only for a child as small as Tina to follow. It was an indication of how exhausted I was that I hadn’t immediately considered that the murderer could approach the ridge from other directions.

I shifted slightly, settled Tina more comfortably into my lap, then pressed my eyes shut, picturing the map that Chad had laid out on the Fisher’s front porch. I thought about it, working to recall each of the roads and formal trails that crisscrossed the area. Then I visualized the route Possum and I had followed and estimated the distance we’d traveled.

Camp Cadiz, I realized, was actually much closer to us than to the Fishers’ house. Park a vehicle at Camp Cadiz, walk into the forest along the well-marked River-to-River Trail and cross the footbridge that spanned the ravine. After that, I figured the spot where Tina and I waited was no more than a quarter of a mile along the ravine from the bridge.

At gunpoint, a living victim could be forced to walk to this very place. And, if one was strong and determined enough, a body could be carried from the parking lot at Camp Cadiz to the place where I’d found the bones.

The campground—the most primitive of all the campgrounds in the Shawnee National Forest—was remote and only occasionally used by backpackers making the days-long river-to-river trek between the Ohio and the Mississippi. It was the kind of place where a murder could easily go unwitnessed.

I’d visited Camp Cadiz. Once. Eight years earlier. And I hadn’t been hiking. I’d been driving Gran, Katie and the woman we had just rescued to the safety of the Cherokee Rose. The detour to Camp Cadiz had been brief and unexpected, but the events of that night had seared the campground’s layout into my memory.

I cuddled Tina closer—comfort for her, comfort for me—as I remembered.

Gran had to pee.

Like many such urges, it presented itself at a most inconvenient moment. We were about thirty minutes away from Maryville. And that, as Gran was fond of saying, put us exactly at the hind end of nowhere. Certainly, we were an uncomfortably long way from the nearest public restroom.

The road, lit only by the headlights of the boxy, blue passenger van I drove, cut through a densely wooded and virtually unpopulated section of the Shawnee National Forest. As we slowed to round curves, our lights skimmed undergrowth that, from the van, looked impenetrable. Given Gran’s poor night vision and the city suit she was wearing, it probably was.

Gran was as outdoorsy as I was. Lean and athletic, she was an amateur naturalist who had spent most of her life exploring the forest, hiking alone for hours. But no matter that she’d willingly spend hours in a bog or scramble up a rocky slope in search of a medicinal plant or climb high into the branches of a tree to glimpse some endangered species, Gran wasn’t the kind of person who would relieve herself in public. And—no matter how unlikely it was that anyone would see her—she considered the side of the road as definitely public.

I mulled over the problem, but before I could come up with an alternative, Gran offered one.

“The turnoff for Camp Cadiz should be close,” she said.

We’d gone less than a quarter of a mile when I spotted the small, reflective green sign pointing the way to Camp Cadiz with white letters. A quick turn down a gravel road and we were there.

Seven decades earlier, when F.D.R. had been president and long before southern Illinois bothered itself with concerns about tourism, Camp Cadiz had been a Civilian Conservation Corps camp. The shadowy remains of half a dozen old barracks still dotted the campground. River-stone foundations and clumps of trees and brush provided privacy between a dozen primitive campsites. Along the camp’s perimeter, thick foliage joined with the night to create a wall of darkness beneath a starry sky.

The outhouse was at the far edge of the campground.

Missy was curled up sleeping on the bench seat at the very rear of the van. She straightened when I turned into the rutted lot and shifted into Park. I looked over my shoulder in time to see her confused and panicked look as her eyes darted around the interior.

Gran, who sat just behind me, turned her head and spoke before I could.

“It’s all right, honey,” she said, her tone as soothing as the slow, soft syllables that marked her speech and belied her energetic personality. “You’re safe. We’re just stopping so that I can use the facilities.”

“We’ll be at the Cherokee Rose in under an hour,” I added. “Where there’s a nice, clean bathroom. With a toilet that flushes. But if you can’t wait…”

Missy shook her head and managed a weak, exhausted smile. Then she turned to rest her forehead against the side window and stared out at the darkness.

Katie was beside me in the front seat, still snoring softly.

Even half-asleep, my sister was beautiful—petite and curvy with pale yellow hair, hazel eyes flecked with gold and a peaches-and-cream complexion. An angel, people were always saying. And I agreed, not only because she was pretty but because she’d been my guardian angel during the earliest years of our childhood. Maybe that’s why I’d stood up for her that morning when she’d stripped off her apron, come running from the kitchen and unexpectedly climbed into the van.

“I’m going, too,” she’d announced breathlessly.

Gran shook her head.

“You and I have talked about this before, Katie. You have to accept that there are things that you simply can’t manage.”

I hated it when Gran used that tone with Katie. Katie’s asthma, according to Aunt Lucy, was the only reason her involvement with the Underground was limited to playing hostess and cooking—something she already did for the paying guests at the Cherokee Rose. But there was more to it than that.

“She’s not like Brooke,” I’d once overheard Gran tell Aunt Lucy. “Katie’s not strong emotionally. You’ve seen it yourself. Tears one moment, anger the next. Face it, Lucy. She’s never gotten over her mother abandoning her. Or the abuse.”

As I looked at my sister, I saw uncharacteristic determination in the way she lifted her dimpled chin. Just a couple months short of her eighteenth birthday, Katie was my senior by a year and a half. But over the past couple of years, she’d grown so timid and unsure of herself that I’d begun to think of her as much younger than me.

Now I wondered if the root of that problem was not our mother, but Gran. Although she pushed me to be independent, to take on challenges and pursue my ambitions, she still made most of Katie’s decisions for her. And encouraged Katie to stay close to home. Where it was safe. Usually, Katie seemed content to do whatever Gran wanted.

But not today.

“Go back inside, Katie,” Gran was saying, and her tone made it sound as if she were speaking to a child. “Like a good girl.”

Though twin red blotches were already standing out against her pale cheeks and she’d started wheezing, Katie didn’t move from the backseat. Nothing about her expression changed as she dug in a pocket, took out the inhaler she always carried and gave herself a puff of medicine before tucking it away again.

In that one quick action she reminded me that she was fragile, at least physically. I opened my mouth, ready to suggest to Katie that she’d be more useful if she stayed at home, when she did something she’d never done before. She leaned forward and stretched out her hand to clasp my shoulder.

“Please, Brooke. Don’t leave me behind. I can help, if you’ll let me. I want to make Gran and Aunt Lucy proud of me, just like they are of you. I’m a good driver. When you and Gran go to the house, I’ll sit with the engine running. In case we have to leave fast.”

Maybe it was Katie’s courage that inspired me. Or maybe it was the yearning I heard in my sister’s voice. But it prompted me to do something I’d never done before. I told Gran that Katie was brave and helpful and that she was going with us. I was surprised when Gran hadn’t protested.

Now, I nudged Katie’s shoulder.

“Hey, sleepyhead.”

Katie yawned, stretched her arms upward until they touched the van’s ceiling, then yawned again as she turned her head slowly, blinking the sleep from her eyes as she looked around.

“Pit stop at Camp Cadiz,” I said. “You interested?”

“Ugh,” she muttered. “An outhouse. No way.”

She snuggled back down into the seat and put her arm across her face.

I turned off the engine and the radio, but left the headlights on, aimed in the direction of the outhouse.

I’d planned to sit and wait for Gran. But I shifted in my seat just in time to see her step out and nearly fall headlong into a pothole that she hadn’t noticed in the dark. And it occurred to me that the stretch of weedy meadow between her and the outhouse would present similar hazards, without benefit of the van’s door to grab onto.

I scooted out from behind the wheel and met Gran as she was carefully stepping over one of the logs that kept cars from driving into the campground. I took her arm and held it tight. We walked across Camp Cadiz together, our bodies throwing long shadows in the headlight beams.

Tina kicked and cried out in her sleep.

“Mommy! Daddy!”

I tightened my hold on her.

“Soon, little one. You’ll see them soon.”