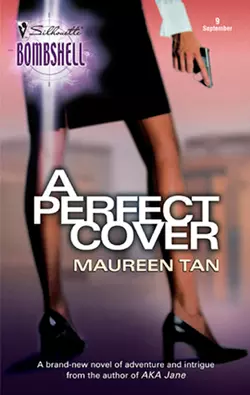

A Perfect Cover

Maureen Tan

Mills & Boon Silhouette

Lacie Reed was the best agent to send to the Big Easy to catch a serial killer. Not just because of her stellar track record, but because the undercover operative looked exactly like the kind of woman this murderer might go for.Lacie was more than ready to play the mouse, knowing she had a big cat to catch. But once she infiltrated the small New Orleans community, befriending the very people she was trying to protect, the stakes got higher. Lacie began taking risks so big that Detective Anthony Beauprix wondered if he had hired the wrong girl for this gruesome case. Good thing Lacie always got her man. And if the sexy detective didn't watch himself, she'd get him, too….

“Tan writes in cutting bursts of staccato energy, a style that mellows only for a few delectable passages of romance.”

—Library Journal

“…too dangerous…no backup…can’t allow it…another way…against policy…irresponsible if I…”

Finally he ran out of steam. Or so I thought.

“Lacie, you’re smart and perceptive and you know your stuff. I wouldn’t mind spending more time with you. Professionally. Or personally. But there’s no way I’m going to let you risk your life for this case.”

I stared at him, taken off guard by his admission. But I wasn’t about to let my emotions get in the way of my better judgment. Or doing the work I was committed to.

“I’m going to do this,” I said quietly. “You can help me. Or you can cut me loose. Like it or not, Anthony, I have the perfect cover.”

Dear Reader,

We’re new, we’re thrilling, and we’re back with another explosive lineup of four Silhouette Bombshell titles especially for you. This month’s stories are filled with twists and turns to keep you guessing to the end. But don’t stop there—write and tell us what you think! Our goal is to create stories with action, emotion and a touch of romance, featuring strong, sexy heroines who speak to the women of today.

Critically acclaimed author Maureen Tan’s A Perfect Cover delivers just that. Meet Lacie Reed. She’ll put her life on the line to bring down a serial killer, even though it means hiding her identity from the local police—including one determined detective.

Temperatures rise in the latest Athena Force continuity story as an up-and-coming TV reporter travels to Central America for an exclusive interview with a Navy SEAL, only to find her leads drying up almost before her arrival. That won’t deter the heroine of Katherine Garbera’s Exposed….

They say you can’t go home again, but the heroine of Doranna Durgin’s first Bombshell novel proves the Exception to the Rule. Don’t miss a moment as this P.I.’s assignment to guard government secrets clashes with the plans of one unofficial bodyguard.

Finally, truth and lies merge in Body Double, by Vicki Hinze. When a special forces captain loses three months of her memories, her search to get them back forces her to rely on a man she can’t trust to uncover a secret so shocking, you won’t believe your eyes….

We’ll leave you breathless! Please send me your comments c/o Silhouette Books, 233 Broadway, Suite 1001, New York, NY 10279.

Best wishes,

Natashya Wilson

Associate Senior Editor

A Perfect Cover

Maureen Tan

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

MAUREEN TAN

is a Marine Corps brat, the eldest of eight children and naturally bossy. She and her husband of thirty years have three adult children, two grandchildren and currently share their century-old house with a dog, three cats, three fish and a rat. Much to his dismay, their elderly Appaloosa lives in the barn. Most of Maureen’s professional career has involved explaining science, engineering and medical research to the public. To keep her life from becoming boring, she has also worked in disaster areas as a FEMA public affairs officer and spent two years as a writer for an electronic games studio. Maureen’s first Bombshell book, A Perfect Cover, is set in New Orleans and recounts one woman’s fight to save Vietnamese immigrants from a serial killer.

For my family and friends, who make it all worthwhile.

And for Peter, the love of my life.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Epilogue

Prologue

I never knew my mother. She was probably a prostitute. Or perhaps she was just a woman who loved the wrong man. In either event, she was most likely dead.

There was panic in the streets of Saigon when Ho Chi Minh’s troops poured into the city. Barefoot, ragged soldiers carrying AK-47s streamed from hidden tunnels. The Cholon district was in flames. South Vietnamese soldiers were stripping off their uniforms, trying to blend in with the population. And the Americans—caught off guard by the swift fall of the city—were fleeing the embassy’s rooftop by helicopter, abandoning their friends and allies.

Abandoning their children.

That day, an American soldier—a black man in a torn and charred Marine sergeant’s uniform—burst into Grandma Qwan’s home. He interrupted a dozen orphaned children and Grandma Qwan as they knelt in prayer, saying the Rosary out loud, petitioning the Virgin for her protection.

The soldier’s hands were badly burned, Grandma Qwan told me later, but still he held a blanket-wrapped toddler tightly in his arms.

“Her name is Lai Sie,” he said in Vietnamese as he put the child gently on her feet and placed a silk-wrapped bundle on the floor beside Grandma Qwan.

Stunned into silence, Grandma Qwan simply stared at the soldier. His hair was singed, his eyes were bloodshot, and tears streaked the gray soot that coated his dark face. Later that night, Grandma Qwan discovered enough money and jewelry among the little girl’s clothing to support the orphanage for years.

“Please. Keep her safe for me,” was the soldier’s only request. “I’ll come back for her.”

Then he’d disappeared into the chaos of the smoke-filled streets.

I waited for years, but my American father never returned. And no young Vietnamese woman stepped forward to claim me.

Grandma Qwan loved and protected me as she did all of the children in her care. But my coloring and features, inherited from my parents, made me an outcast in my own country. I was bui doi. Throughout my childhood, I heard the curse shouted by pedicab drivers, spat out by old women in the marketplace, muttered when soldiers knocked me aside, used as a taunt by playmates.

Bui doi. Dust of life. Bui doi. Child of dust.

Chapter 1

I was sitting in darkness, waiting to be rescued. Or to die. As were we all. More than fifty of us, trapped inside the long, battered trailer of an eighteen-wheeler. Men and women, young and old. A few adolescent children. But no infants. Yet.

All around us were splintery shipping crates, large and small. They filled the trailer top to bottom and front to back, with just enough room left between the rows to conceal a human cargo. Shipping labels, stenciled in black paint, said the crates contained an assortment of machine parts destined for America. We, too, had been destined for America. But the truck that pulled us was long gone, its trailer and its cargo—human and machine—stationary. We were locked in and abandoned. And the heat was becoming unbearable.

Beside me, Rosa groaned—a deep, harsh sound with surprisingly little volume to it. I leaned in closer to her, my hand brushing the sleeve of her light cotton dress, then moving to find a thick braid, a soft cheek and, finally, her forehead. It was damp with perspiration. From the heat. And from her labor. I stroked Rosa’s hair back away from her face, murmured pleasant, soothing nonsense and tried to give comfort where none existed.

Rosa groaned and tensed again. My wristwatch was gone, stolen. But I had counted the seconds between her contractions, confirming what we both already knew. Soon, Rosa’s child would arrive. And I wished I could stop the inevitable.

I’d met Rosa weeks earlier. As the sun rose over the lush green of the jungle, a group of desperate and excited strangers had gathered on a hill, close enough to the Actuncan Cave to feel the cool, damp air flowing from its mouth. We had each paid a life’s savings to smugglers called polleros— chicken herders—for a few forged papers, the promise of a minimum-wage job and legal citizenship for any of our children born on U.S. soil.

“Me llamo Rosa Maria Martinez,” Rosa had said. “I go to America. To New York City.”

“I am Lupe Cordero,” I replied in Spanish that was touched by the distinctive accents of rural Guatemala. “From Chichicastenango. I am fifteen and go to live with my sister in Houston.”

Lies. All of it. My real name was Lacie Reed. I was twenty-seven, an American citizen, and I had no sister. But there was nothing about my appearance to make her doubt me. My hair was dark and curly, my skin unwrinkled and golden-brown, my almond-shaped eyes dark. And I was tiny—small-boned and just a breath over five feet tall. Like Rosa and the others, I was dressed to travel in nondescript clothing that would draw little attention.

This wasn’t the first time I’d lied for my Uncle Duran. I was Special Assistant to the Right Honorable Senator Duran Reed, a position that covered an amazing variety of activities. This time, it meant being part of an interagency task force that included Mexico’s National Immigration Institute and the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. The INS.

For two weeks we traveled together on foot, by car and by rickety open truck, making our way from Flores to Tapachula, Mexico. Then two days by freight train brought us to Veracruz. We spent that night in a warehouse, on a dirty concrete floor surrounded by fifty other exhausted refugees.

The United States government wanted these people stopped. These and many thousands like them. A flood of illegals from Central and South America passing through Mexico on their way to the U.S. But even as the government of Mexico cooperated with the U.S. to solve the problem, corrupt officials grew rich extorting the immigrants.

If organized traffickers were brought to justice, the danger for those who continued traveling along Mexico’s underground highway would be lessened. But that required the testimony of a reliable witness. And immigrants who cooperated with the authorities had a bad habit of disappearing or dying.

That was where my skills came in.

In the dim yellow light of a bare overhead bulb, in the layer of grime on the warehouse floor, I used the edge of a plastic cigarette lighter I found in a corner to draw the faces of two National Railway workers I had seen taking bribes that day. It didn’t matter if I used a pencil on a sketch pad, a piece of chalk on a blackboard or a stick on a smooth patch of ground. If I drew what I saw, I could remember it and reproduce it accurately. Always. Faces were easy. As were diagrams and numbers. More than that, the very process of drawing objects and people freed my intuition, enabling me to make connections that weren’t apparent when I merely observed a situation.

And so, that night, I added more descriptions to my mental catalog of incidents and faces. My sketches at journey’s end, along with my recollection of dates, locations and times, would enable both governments to identify and arrest traffickers. Then I would testify against them.

The sun was just rising when we loaded into the truck. We went willingly, ducking beneath an overhead door that had been raised only a few feet from the trailer floor, moving as quickly as we could into the shadowy interior. We squeezed through a maze of claustrophobic aisleways created by shipping crates, occasionally crouching low to avoid a load bar. When our progress through the trailer was briefly stalled by a large, slow-moving man from Honduras, I looked more closely at one of the bars. A ratcheting mechanism telescoped the tubular steel bar outward until it spanned the width of the trailer. Swivel rubber pads at each end wedged the bar tightly into place, creating a strong, temporary, horizontal barrier.

At the far end of the trailer was an open area large enough—barely—to accommodate all of us. Rosa and I settled down in a cramped corner as a pollero announced that the drive would be long and uncomfortable. But it would end in America. In Laredo, Texas. In the meantime, we could relieve ourselves in the buckets he’d placed inside the trailer for us. Then he closed the door with a thud and I heard a heavy lock drop into place. The truck lurched its way out of the freight yard and picked up speed on the roadway.

We were still moving when the narrow pinpoints of daylight coming through small scars in the trailer’s aluminum shell faded to darkness.

In the middle of the night, things went terribly wrong.

It started with sirens in the distance. As the sound came closer and caught up with us, conversation stopped inside the trailer.

“Uno. Dos. Tres.” Rosa counted under her breath as the sirens resolved themselves into at least three vehicles.

The truck slowed and the surface beneath the tires roughened. The floor beneath us sloped slightly to one side as the driver pulled the rig onto the shoulder of the road. But he kept the truck moving.

The sirens blazed past. The red lights of emergency vehicles glanced off the trailer, throwing shattered fragments of light into the interior. Then the light was gone. And the sirens were lost in the distance.

But the driver must have panicked. The truck pulled back onto the highway, continued along at high speed, then abruptly braked and downshifted to make a right turn. More time passed and the road deteriorated. The movement of the trailer became increasingly violent. We were thrown like rag dolls, bouncing against each other and into the unyielding shipping crates.

Then, abruptly, the terrifying ride stopped.

For a moment, except for the sound of the engine, there was silence. Then male and female voices erupted, shouting in Spanish, cursing the driver in the vulgar colloquialisms of Mexico and Guatemala and Honduras and El Salvador. We threatened him, demanding that he open the trailer door and let us out now. But the driver didn’t respond. Instead we felt the jolt as he freed the truck from the trailer. Then he drove away, abandoning us to the desert heat.

Despite the exterior lock, a dozen sets of bare fingers and straining backs and shoulders tried to pull the trailer door upward. The heavier men and a few of the women threw their shoulders against the door, trying to shift it outward. We climbed up the stacked crates, grasped the overhead track for the door and tried to yank it from the brackets that mounted it to the ceiling.

We were still working to escape when the pale beginning of a new day gradually found its way in through the tiny holes in the trailer wall. The heat inside the trailer grew worse. As each escape attempt was revealed as futile, activity inside the trailer slowed. An hour past dawn and those inside the trailer were quiet. Deathly quiet.

Rosa cried out again.

Her contractions were now coming in waves, one after another, barely giving her time to rest in between. For the first time since her labor began, she began crying. Quiet, hopeless weeping. Heart-wrenching, inconsolable weeping.

“Never give up, little one,” I murmured.

Only after I had spoken did I realize that I’d said the words in Vietnamese, repeating them exactly as I had first heard them. Rosa was too preoccupied to notice, but the words brought back memory, still vivid though two decades had passed.

I was eight when Grandma Qwan put me on a fishing boat crowded with people fleeing Vietnam. The men she’d paid had assured her that I would be safe. And perhaps they’d believed that. But we were intercepted midvoyage by Thai pirates. From my hiding place beneath a pile of rotting nets, I listened to the screams as they murdered the men, raped the women and stole everything of value.

Fourteen of us were left alive—cast adrift on a ruined boat without food or water. Thirteen women and one scrawny, mixed-race orphan who reeked of fish guts and filth. Days passed. One by one, the others died. Some of thirst and exposure. Some quietly, hopelessly, casting themselves into the sea. Until just one young woman and I remained. Though I was just a child, I had seen enough death to know that she would not live much longer.

That night she had held me close.

“Never give up, little one,” she had whispered in Vietnamese, as if she were telling me a precious secret.

When I awoke, she was gone. And I was alone.

I did not despair. I did not give up.

I had come too far to die today.

I stopped thinking about the imminent arrival of Rosa’s child. Using an edge of the cigarette lighter against the vertical surface of a nearby crate, I imagined that I was drawing with a nicely sharpened charcoal pencil on paper torn from an expensive vellum pad. I drew the exterior of the trailer, its only door solidly locked, and surrounded it with desert. A blazing sun hung in the sky. Mentally, I set that drawing aside. Then I drew the interior of the trailer.

I began with a rectangle with six solid walls—back and front, sides, ceiling and floor. I sketched the details of a door that pulled upward to open, that rode on tracks mounted parallel to the ceiling. Between the tracks and the ceiling there was at least a foot of space. I added crates. And refugees. And load bars that ratcheted into place…

The load bars could be moved!

I stood and began dragging at one of the horizontal bars as I described my plan to the others. Within moments, I had help. We freed the bar, set it on its end and ratcheted it upward until it pressed against one of the tracks from which the trailer door was suspended. Then the big, slow-moving man from Honduras, who was the strongest among us, continued working the stiff ratchet. He lengthened the load bar one inch at a time until there was so much pressure against the track that it buckled and bent.

Though the door remained on its track, it sagged at a top corner, bringing in a triangle of bright sunlight and a hot desert breeze that was fresher and cooler than the stale air inside the trailer. The space between the door and its frame wasn’t very large. Even the weight and strength of the man from Honduras failed to make it larger. But the gap was enough that a very small, athletic woman from Vietnam could squeeze herself through.

I pushed myself through headfirst and on my back. Head and shoulders escaped the trailer and above me I saw the brilliant blue Texas sky. Cloudless and beautiful. Breathtaking. But the thrilling moment of rebirth was immediately quashed by more practical concerns.

Grabbing finger and handholds wherever I could find them, I hauled myself upward until my entire body was free of the trailer. Then I hung for a moment, catching my breath, taking advantage of the trailer’s height to look off into the distance. As far as I could see, there was nothing but clumps of scrub, spiny cactus and an occasional thorny tree. And lots of rocks. The largest of which I tried not to land on when I pushed away from the trailer and dropped to the desert floor.

The landing was inelegant, but relatively painless. I picked myself up off a patch of dusty earth, spent a moment prying a large dry thorn from the palm of my right hand and dusted the back of my pants. Then, using a solid-looking rock, I tried to dislodge the padlock that locked the trailer door down. Spurred by cries of encouragement coming from within the trailer, I bashed and pounded at the lock until my hands were bloody, until the rock split in two.

Then, though no one could see me, I shook my head. Beating at the lock was wasting time and eating away at my remaining energy. Adrenaline helped, but it was only a temporary cure for dehydration and heat exhaustion.

“Take care of Rosa,” I shouted in Spanish. “I will go find help. And I will come back. I swear.”

Then I turned my back on the trailer, focusing on a single goal. I had to find help. For everyone. I began following the truck’s tire tracks. I wanted to hurry, to run, to push myself to my limits. Instead, I walked. Slowly, steadily, concentrating on my breathing.

I was already tired and thirsty. It didn’t take long before even the ruthless beauty of the desert held no appeal. Thoughts of how I would go about capturing its arid vistas with pen and ink faded. I began cursing the cloudless blue sky, the thorns that pierced my clothing and my skin, the rocks and sand that filled my shoes, and the relentless late-morning sun. My head throbbed in rhythm with every step, with every painful breath.

My attention drifted, back to the trailer, back to Rosa, back to our travels through Mexico and Guatemala. I saw myself walking in the streets of Flores and Veracruz and Tapachula. I stumbled on a rock and fell hard onto my hands and knees. A dry black branch tore a jagged furrow in my leg. Pain brought concentration back with a snap. Ignoring the warm trickle of blood down my left calf, I stood. And made a horrifying discovery.

I had wandered away from the tire tracks.

I tried not to panic, tried not to think of dozens dying because I had gotten lost. I took a deep breath, then another, and carefully reoriented myself. The tracks had been heading north and I had followed them, keeping the rising sun on my right. Now I was facing directly into the sun. I turned slowly, looking for evidence that a truck had recently passed that way. Several dozen yards to my left, I spotted a crushed cactus and a brittle, skeletal tree whose spindly limbs were smashed on one side. I walked in that direction and rediscovered the tracks.

I walked on.

I am in Texas, I repeated to myself. In Texas. Near Laredo. And I must find help. I concentrated on the pattern of tires in the dust. On the details left by the tread. On the texture of the plants crushed by the truck’s passing that way not once, but twice. On the tiny brown lizards that skittered frantically across my path. On insects so small that the track’s grainy texture shaded them.

I walked on.

The tire tracks led to the barest hint of a road. I followed it, head bent, eyes downcast, focused only on the scars that passing tires had laid on the desert floor. I traced each scar with an imaginary stylus, wove each detail into an imaginary length of rope stretching between me and the main highway, between me and the help I needed.

I walked on.

Soon nothing mattered but the heat. The dreadful, pounding heat. And the imaginary rope. I held on to it with my mind, with all the strength that remained in me, watching closely as it gradually twisted, turned and changed. It became a fishing net, worn but still strong, tossed into the sea by the sinewy brown hands of Thai fishermen. Thrown to a child who drifted, helpless and alone, in a battered boat on the South China Sea. Pulled on board by hands that eagerly pressed a tin cup of water to a child’s parched lips.

I walked on.

Suddenly there was a blaring horn and squealing brakes.

America! I thought as I heard a woman shouting at me in English. I’ve made it to America!

More lucid thoughts quickly followed, snapping me back into the present.

I had emerged from the dirt road, stepped into the highway and owed my life to the quick reaction time of a middle-aged woman with bleached-blond hair driving a shiny blue pickup truck. She rolled down her window to get a better look at me, stopped shouting, and scrambled from her vehicle. Her arms around my shoulders supported me as we staggered back to her truck.

I need help, I thought, but the words came out in Spanish. I saw her incomprehension, forced myself to concentrate and managed a language I hadn’t spoken for many weeks.

“Please,” I said in English, “Do you have a phone I can use? To call the police.”

She listened, openmouthed, as I offered the dispatcher enough information to convince him that the situation was beyond urgent. Then I disconnected. And my rescuer stopped me from walking back into the desert alone.

I sipped the bottle of lemon-flavored water she offered as I counted the minutes. A lifetime seemed to pass before the police arrived, before I could lead a convoy of police cars and ambulances to the abandoned trailer.

Within that lifetime, no one inside the trailer died.

Within that lifetime, a baby girl was born.

Chapter 2

U ncle Duran had arranged his desk to take full advantage of the window in his office. A man of upright posture, powerful build and impeccable taste, the senator sat with his back to the expanse of glass, fully aware that the view from the trio of wing-backed chairs facing his desk was a postcard image of the nation’s capitol. Seen from a height and distance that softened detail and muted noise, visitors to his office saw stately monuments, manicured lawns, cherry trees and the orderly movement of pedestrians and traffic along wide boulevards. It was Washington, D.C., at its most picturesque.

Framed by the window as he sat in his leather-bound chair, the senator looked positively presidential.

Not only did he look the part, but he wanted the role. Because he was a man who knew the right people and did the right things, the Beltway press was already speculating that he was a strong contender for the Democratic party’s nomination. Although it was too early in the election cycle for Uncle Duran to make a public announcement, he had begun talking privately and often about his ambitions. Mostly to people who counted. Occasionally to me. Before I’d left for Mexico, he’d wondered out loud if being President would inhibit his ability to act as he saw fit, then smiled as he told me that my job was to be sure that it didn’t.

It was only when he stepped away from his big window and massive desk that first-time visitors realized how big Uncle Duran was. At six foot seven and a muscular three hundred pounds, he dwarfed not only me, but most of his constituency.

It was his size that had terrified me as a child when I first saw him in the Songkhla refugee camp in Thailand. Though I wanted desperately to go to America, I shrank back as this burly, big-voiced man and his entourage approached. Only a camp worker’s tight grip on my hand kept me from running to hide in my bed.

Most Americans I had met had large noses, but this man’s was very large and crooked. His face was craggy, with a tall forehead, a jutting chin and thick eyebrows. Like a fairy-tale giant, I thought as I stared at him. Without hesitating, he leaned forward and scooped me up, lifting me far from the ground. I trembled when I saw that his eyes were like pale pieces of silver. And that his teeth, when he smiled, were large and very white. I had wondered if he ate children.

Then he turned to those who were with him and spoke. My English was not good enough to understand what he said, but the camp worker whispered a translation. As cameras flashed and pencils scribbled on small notebooks, the senator explained that I was special to him. Because he could not locate my father, his brother and his wife would adopt me. I was the first of the needy children that the loving, generous citizens of America would rescue. He intended to find placements for hundreds of children like me—children who had been orphaned by war and who dreamed of America.

Now, almost two decades later and just months past his sixtieth birthday, Uncle Duran’s dark hair had turned the color of brushed steel. But his rich baritone voice and gentleman’s charm still won hearts and even votes on the campaign trail.

Unfortunately, Uncle Duran was not being charming now. Nor was he smiling. The argument that we were having across his centuries-old desk had boiled down to a few simple truths. It didn’t matter that I had worked for him long enough to prove that my professional judgment could be trusted. And it didn’t matter that I was his brother’s only child. It only mattered that I was defying him.

As I stood behind one of the wing-backed chairs, my fingers digging into its cushioned sides, my face impassive, I watched him clamp his unlit cigar between his front teeth and slowly shake his head. Then he rolled the cigar back into a corner of his mouth to speak again.

“Though I warned your parents against him long ago, I’ve overlooked your friendship with Tinh Vu, even tolerated your addressing him as ‘uncle.’ I tried to accommodate a child’s need to rediscover her roots, to embrace the familiar. But you are no longer a child. And you’re more American than you are Vietnamese. Damn it all, Lacie. When was the last time you actually spoke Vietnamese?”

“It’s been a long time,” I admitted. As a teenager, I’d tried to become part of the Vietnamese community in Chicago, but quickly discovered I didn’t belong. Even Uncle Tinh and I had, for many years, conversed in English.

Uncle Duran nodded, smiled around his cigar. But if he thought I was going to back down, he was mistaken.

“Does it matter how Vietnamese I am?” I said. “Or how American? I’m a good mimic and a quick study. As you’ve often pointed out, I can fit in anywhere I want to. All I am asking is to be allowed to do a job that I’m trained to do. That’s all Uncle Tinh is asking.”

Uncle Duran’s smile disappeared.

“And I am asking you—no, I am telling you—that I will not authorize this venture. I have been part of your life longer than Tinh Vu has. I was the one who found you, who gave you a family and a job that means something. Can you so easily dismiss my decision about this?”

Tears welled in my eyes. I didn’t want to defy him, to hurt him. But it was because of him, because of the values he’d taught me, that I had made the only decision I could when Uncle Tinh called.

“You’ve told me often of your work for the senator,” Uncle Tinh had said. “Can you come down to New Orleans right away? On business, Lacie. Please. My people…our people…need you.”

How could I say no?

I looked directly at Uncle Duran, lifting my chin for emphasis.

“I’m sorry, Uncle Duran,” I said. “This is something I have to do.”

He moved the cigar away from his mouth, put it down on the clean crystal ashtray on his desk. When he lifted his head, our eyes met and I braced for what I knew was coming.

“You’re fired,” he said clearly. “Effective immediately.”

I had chosen.

And so had he.

I went back to my adjacent and more functional office. Determinedly dry-eyed, I packed my personal belongings into several cardboard boxes as Uncle Duran stood in the doorway and watched, unspeaking. Then he helped me carry my possessions downstairs and load them into my car. But before I turned the key in the ignition, he leaned into the open driver’s side window.

“Even if I approved of Tinh Vu, which I don’t now and never have,” he said, “I cannot risk having anyone in my employ so closely associated with organized crime. I know what your feelings are on this subject, and I’ve tried to spare them by waiting until now to bring this up. I have evidence, Lacie. Recent evidence that Tinh Vu is actively involved in the production and distribution of breeder documents. You, of all people, should know what that means.”

Then he stepped back from the car. But he spoke, once again, before I’d completely rolled up the window.

“Should you ever find the courage to face the truth about your Uncle Tinh, call me. We can revisit the issue of your employment.”

That gave me plenty to stew over as I sped down the Beltway toward the studio apartment I rented. Uncle Duran’s suspicions about Uncle Tinh’s ties to organized crime were all too familiar. But a specific accusation and talk of evidence were new.

Even though he had never even met him, Uncle Duran had never made a secret of his dislike for Uncle Tinh. It seemed to me that his dislike grew to the point of near obsession when Tinh’s City Vu opened in New Orleans. After that, Uncle Duran had taken every opportunity to point out that great food and impeccable service were not the reasons the restaurant thrived. Impossible, he said any time an opportunity presented itself, that an immigrant could parlay a storefront restaurant in Evanston, Illinois, into a landmark twenty-room hotel and restaurant just a block from the French Market in New Orleans. Tinh Vu could not have achieved this merely through hard work.

I agreed. And so did Uncle Tinh.

Even when he still lived in Evanston, Uncle Tinh had catered to those who wanted to keep their business dealings private. It was not unusual for businessmen, cops, politicians, criminals and, I suspected, individuals who combined two or more of those avocations to meet over a meal in the little storefront. Uncle Tinh always managed to arrange that such meetings were undisturbed. In New Orleans he’d taken the concept a step further. He claimed proudly that if you were to ask any journalist in the Big Easy where the city’s power brokers met, their list would include the quartet of small dining rooms on the mezzanine level of Tinh’s City Vu. Those rooms, I knew, were swept daily for listening devices.

That did not make my adopted Vietnamese uncle a criminal.

Supplying false documents did.

A few years earlier I’d helped the INS break up a documents syndicate in Los Angeles by locating a storage facility that, when searched, yielded two million “breeder” documents. Such documents—counterfeit social security cards, resident alien cards, U.S. birth certificates and more—established legitimate backgrounds for illegal immigrants. They proved legal residency in the U.S. and were used—bred—to obtain genuine documents such as driver’s licenses, student ID cards and insurance cards. Counterfeit documents were big business. The stash I’d discovered was worth forty million dollars on the streets. And those who produced such documents were closely tied to those who exploited illegals once they arrived in the U.S.

In the past I had dismissed Uncle Duran’s periodic accusations about Uncle Tinh, thinking that he was unnecessarily suspicious. And, perhaps, jealous. But now, as I turned onto the ramp down to the garage beneath my building, I wondered whether I should return to Uncle Duran’s office and examine the evidence he claimed to have.

Did I have the courage to do that?

The tears that I’d so successfully suppressed for most of the afternoon began to creep down my cheeks as I pulled into my parking spot. I killed the engine, lay my arms across the steering wheel and rested my forehead against them. For a few minutes I sat that way, unmoving, as I considered my options.

Though I owed much to my Uncle Duran and I had worked hard to make him proud of me, Uncle Tinh was my oldest and dearest friend. He and I first met when my new American parents took me to a little campus restaurant in Evanston, Illinois, for pho. As I attacked the noodle soup with chopsticks and a deep ceramic spoon, Tinh Vu had nodded approvingly, then come over to chat with us. In doing so, he gave my parents a means to communicate with a nine-year-old girl who had lived with them for just a few weeks. My parents spoke only a few words of Vietnamese; I knew only the broken and often crude English spoken by street-smart teens at the refugee camp.

Over the years I ate in the restaurant’s tiny kitchen frequently. Beneath a colorful poster of the kitchen god, Ong Tao, Uncle Tinh and I talked about our lives and our problems and our dreams as we ate steaming bowls of pho or nibbled chopsticks full of do chua, a spicy-hot fermented pickle. About the time I went off to college, Uncle Tinh sold the campus town restaurant and moved to New Orleans. But despite busy schedules, we kept in touch. My last visit to the Big Easy had been just five months earlier.

I trusted Uncle Tinh with my life. Did I trust him not to lie to me?

I lifted my head from my arms and sniffled as I dug around the glove compartment for a tissue. I blew my nose, then looked at myself in the rearview mirror. My own very serious dark eyes stared back at me.

I knew what I was going to do.

I would go to New Orleans. Uncle Tinh would explain the current crisis in detail and, if it was within my power, I would stay and help the Vietnamese community. At the same time, I would observe and interact with my Uncle Tinh not only from the perspective of someone who had grown up loving him, but as the adult I now was.

When I had done all I could, I would return to Washington. There, though the thought of it made my heart ache, I would examine Uncle Duran’s evidence. If it had substance, I would confront Uncle Tinh, giving him a chance to convince me of his innocence.

And if I discovered that Uncle Duran’s accusations were true?

I took a deep breath as I stepped from my car. I squared my shoulders, straightened my spine and lifted my chin. For the second time that day, I made the only decision I could.

If Uncle Tinh was a criminal, I would dedicate myself to bringing him to justice.

Chapter 3

A week later I checked into the room that Uncle Tinh had reserved for me at the Intercontinental New Orleans. The luxury high-rise hotel was conveniently located in the Central Business District and offered impeccable service along with the anonymity of almost five hundred guest rooms.

My flight was an early one so, as we’d agreed, once I’d settled into my room, I joined Uncle Tinh at the Old Coffee Pot. His restaurant—Tinh’s City Vu—was a dinner place, so the Old Coffee Pot was our long-time favorite for a quiet, relaxed breakfast.

Uncle Tinh was already sitting at one of the little tables in the restaurant’s tree-shaded courtyard when I arrived. Before he realized I was there, I stood for a moment watching him sip his coffee and, once again, I found it impossible to believe that this man could be a criminal. I walked over to stand beside the sun-dappled table.

“Hello, Uncle Tinh,” I said.

He smiled broadly as he stood and hugged me enthusiastically. Then he held me briefly at arm’s length, his dark eyes sparkling as he asked about my flight. I looked back at the man who was the bridge between my two worlds, my only connection to my birthplace and its culture.

Although he was almost sixty, Uncle Tinh looked much the same as he had the day I met him. He had a round, unlined face, a body kept strong through the practice of martial arts and was tall for a Vietnamese man—almost five foot eight inches. His head was shaved clean and his hands, as always, were beautifully manicured. He wore a white dress shirt that was unbuttoned at the collar, a pair of gray trousers and his trademark leather sandals. His favorite Rolex watch—a bit battered from hard use—rode on his right wrist, accommodating his left-handedness.

“You look lovely as ever, chère,” he said as we settled into our chairs. “Fit, certainly. But maybe a little too thin.”

I laughed. No matter how much I weighed, Uncle Tinh complained that I looked too thin. In the past month, I had, in fact, regained all the weight I’d lost in Mexico. Which put me at my usual one hundred and five pounds. And I was sure that the bulky blue cotton sweater and jeans that I wore made me look several pounds heavier.

“One of your desserts will remedy that, I’m sure,” I said.

“Ah, that reminds me. Since your last visit, I have created a new dessert. It will be a favorite, I think. But you are my most honest critic. So I wait for your approval before adding it to the menu.”

I had never yet disapproved of one of Uncle Tinh’s desserts.

“I will sample it at the first opportunity,” I said.

Uncle Tinh waited until I’d taken my first bite of the callas—crispy Creole rice cakes smothered in hot maple syrup—before telling me that he’d arranged for me to attend an evening gala in the Garden District. It was being given by the Beauprix family.

“Anthony Beauprix is the son of an old acquaintance of mine. He is a policeman and a friend of the Vietnamese community here in New Orleans.”

Uncle Tinh, it seemed, had already decided to contact me when Beauprix had come to him for help. Beauprix had told Uncle Tinh that without someone inside the Vietnamese community, his investigation was hopelessly stalled. That was when Uncle Tinh had told Beauprix about me. Uncle Tinh laughed as he related that part of their conversation. Or, more correctly, he laughed in reaction to my expression.

“No offense, sir,” Beauprix had said to him. “but I was hoping you could recommend someone who lives or works in Little Vietnam. Someone who’d be willing to pass relevant information on to me. The last thing I need is some gal from up north coming down here and playing cop. I don’t doubt she’s good at her job—she sounds like a fine little actress. But this is police business, always best handled by the police.”

I didn’t know Beauprix and hadn’t worked with the New Orleans P.D., but the attitude was all too familiar. And I knew from experience that my size would make it even easier for him to underestimate me.

“For this,” I asked Uncle Tinh pointedly, “I’ve disrupted my life?”

“Patience, chère,” he replied. His accent, like his restaurant’s food, mixed the French of upper-class Vietnam with the Creole accents of New Orleans. “If I had the means to aid the Vietnamese community without involving you or the police, I would. Certainly, many in Little Vietnam would prefer it that way. But I have only wealth and the guilt of one who did not suffer as many of my countrymen did. This situation requires the intervention of outsiders. Anthony Beauprix is doing his best. But whether he likes it or not—whether he knows it yet or not—he needs you. That means convincing him to accept your help. I have already laid the groundwork. So now I will tell you how it can be done….”

I spent the rest of the day shopping and, by midafternoon, put a dent in the expense money that Uncle Tinh had given me. I was pleased with the purchases I carried back to my room in an assortment of boxes and bags. I now had a suitable dress, appropriate undergarments and matching shoes to wear to the gala. I shed my clothes in the dressing room—a luxury I’d longed for in my small D.C. apartment—and took a long soak in the deep marble tub.

I submerged myself so only my face was above water and considered my future. Unlike Uncle Duran, I was not independently wealthy. Thanks to Uncle Tinh, my stay in New Orleans would cost me nothing and I had enough savings to coast for a while. But eventually I would have to support myself.

If Uncle Duran’s evidence was nothing more than malicious speculation—and I felt that it likely was—I would seek a new job among organizations that already appreciated my diverse and, by most standards, peculiar skills. Past assignments had given me contacts within an alphabet soup of government agencies specializing in national security: CIA, FBI, ATF, DSS, INS. One of them would probably hire me. But the appeal of my job with Uncle Duran had been the commitment to the immigrant community that he and I shared.

As I made circles in the bubbles with my toes, questions about my future ran through my mind. Would I ever again be able to work for Uncle Duran? Did I even want to? Would he blackball me, making finding another job in Washington impossible? What impact would conflict with Uncle Duran have on my parents?

So many questions. No answers.

My mind flashed to the poster that hung in my adoptive mother’s office, and I smiled. Her favorite movie was Gone With the Wind.

“I won’t think about that now,” I said out loud in my best Scarlett O’Hara imitation. “I’ll think about it tomorrow.”

I splashed enthusiastically just for the hell of it, spent a moment blowing bubbles with my head beneath the water and my hair splayed out around me, then practiced my New Orleans accent by reciting Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham out loud until the words echoed off the bathroom’s glossy white-tiled walls.

Out of the tub, I thought about slipping into one of the cushy terry-cloth bathrobes supplied by the hotel, realized that one-size-fits-all wasn’t created with me in mind and, instead, wrapped myself in a thick, white bath towel. Then I sat on the upholstered bench in front of the lighted vanity, carefully applied my makeup, fixed my hair and slipped on my new clothes. I was a vision in basic black.

“Ah, the belle of the ball,” I said as I turned slowly in front of the room’s full-length mirror. Then I laughed and added, “Not!”

Unlike Scarlett, I wasn’t dressed in dusty velvet drapes. But I doubted that Beauprix would fully appreciate my wardrobe choice. At least, not tonight. I took the elevator downstairs and was pleased to note that few eyes turned in my direction as I made my way through the lobby.

I could have taken a cab, but this was New Orleans and I loved the romance, if not the Spartan nineteenth-century amenities, of the city’s arch-roofed streetcars. The St. Charles line ran past the front of the Intercontinental, at the No. 3 stop. I got on, carrying the exact change required, dropped my five quarters into the box and felt like Cinderella going to the ball.

Unfortunately, my teal-green coach was crowded with tourists and commuters, and all the reversible wooden seats were occupied. So I stood toward the back, congratulated myself on selecting new shoes that were actually comfortable, and enjoyed the New Orleans scenery sliding past at nine miles an hour.

About twenty minutes later, I stepped down from the coach at stop No. 19 and walked for two blocks. The umbrella I’d taken as a defense against the light drizzle was almost unnecessary—live oaks formed living canopies along the residential blocks above Louisiana Avenue. The house I was looking for was on Prytania and Seventh, just a block below the free-standing vaults and above-ground crypts of the City of Lafayette Cemetery.

The Beauprix home was a double-galleried Victorian gem with a first-floor living area that even the bodies and voices of several hundred guests didn’t fill completely. Inside, the huge open spaces of the first floor were a swirl of color and texture, of light and sound. Everywhere, tall crystal vases spotlighted by tiny, intense lights overflowed with pink and violet varieties of roses, lilacs, irises and gladiolas floating in clouds of baby’s breath.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t at the moment fully appreciate the beautiful decor, the sounds of celebration or the smell of fresh flowers. Because within a few minutes of my arrival through the back kitchen door of the lovely house, I had ended up standing at a stainless-steel counter, surrounded by the bustle and din of food preparation and reeking of fish and onions.

I wrinkled my nose and tried not to breathe too deeply as I finished dusting a large silver tray of pale-pink appetizers with a sprinkle of red caviar and finely chopped chives. Grateful that the smell was not necessary to my disguise, I wandered across the kitchen to the sink, carefully washed my hands, then rubbed them dry on the front of my bibbed apron. Beneath the black apron was a black rayon uniform that hung limply below my knees. Beneath that, there was enough padding to make me look forty pounds heavier and distinctly barrel-shaped. Once my hands were dry, I briefly tucked my right hand into an apron pocket, assuring myself that the tiny electronic device I’d hidden there was still safe. It was one of a handful of specialized items I’d collected over the years and brought with me to New Orleans.

“Olivia!” the caterer said loudly. “Take that tray out to the dining room, please.”

I counted to ten slowly before looking up, deliberately slack-jawed and blank-eyed, from my contemplation of the heavy support hose and the sturdy black shoes I wore. For the gala, carefully applied makeup had changed my complexion from golden to dusky and I had braided my hair in deliberately thick, uneven corn rows. The wax forms that thickened my cheeks and made my upper lip protrude also distorted my voice.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said slowly.

Ignoring the direction of the woman’s pointing finger, I picked up the silver tray nearest the sink. It was littered with a few limp pieces of parsley, a half-nibbled radish and a few abandoned olives.

The caterer—a tall, middle-aged black woman whose presence seemed to calm the chaos of the busy kitchen—was destined to be a saint. She spent only a moment rolling her eyes heavenward before stepping in front of me, taking the tray from my hands and returning it to the counter.

“This one, honey.” She gave me a filled tray, then corrected my hands so that they held it level. “Now be careful, Olivia. Don’t spill.”

“No, ma’am.”

I offered her a smile enhanced by a gold-capped front tooth, then walked to the dining room down a short hallway lined with glass-fronted shelves stacked with fine china and polished silver.

I slipped behind the long buffet table and carefully set the tray down at the far end of the table, in an open space beside a huge arrangement of irises. The thick petals looked like velvet and were a shade of purple so deep it was almost black. I tucked myself behind the arrangement with my back into a corner.

Slowly, with an air of intense concentration, I began lifting each stem, turning it slightly and settling it back into the vase, as if to make sure that each flower was shown off as beautifully as possible. Except that the flowers I was arranging were at the back of the vase. Either the caterer didn’t notice or she’d given up on keeping the most dim-witted of her employees busy. And I wondered what favor Uncle Tinh had called in to saddle her with such a useless worker.

From behind my curtain of flowers, I peered out at the party through my thick-lensed glasses, genuinely enraptured by the graceful patterns that formed and reformed as guests sought out acquaintances and made new contacts. Laughter mixed with the murmur of voices and the rustle of the leathery leaves of the magnolia trees that overhung the open gallery windows. A live, six-piece band wove it all together with a soft, bluesy melody.

This was New Orleans at its best. For a moment I regretted mightily that Lacie Reed wasn’t making an appearance as herself at the party that Anthony Beauprix had thrown for his father’s eightieth birthday. Briefly, I considered how I could capture the evening in pen-and-ink washed with the faintest suggestion of colors. Then I sighed and considered what Uncle Tinh had told me about my host, Anthony Beauprix.

Besides being a cop who desperately needed my help but was too chauvinistic and anticivilian to accept it, Beauprix was wealthy beyond most people’s wildest dreams. That, Uncle Tinh had told me during breakfast. The Beauprix family was old money, their fortune tied to a history of sailing ships, bootleg rum, smuggled guns and an uncanny ability to end up on the winning side of any war, no matter which side they’d started on. In New Orleans, that knack earned them as much respect as their money did.

Perhaps inspired by a public hanging or two—the citizens of New Orleans also having no problem executing those they respected—the Beauprix family gradually shifted their attention to more legitimate enterprises such as shipping and oil. Which was what made Anthony stand out among the current generation. A maverick, Uncle Tinh said. A beloved black sheep. Unlike his younger brother and sister who’d earned M.B.A.s at Tulane or his engineer and lawyer cousins, Beauprix was a detective in the New Orleans Police Department. A job, Uncle Tinh noted, more suited to the morals and attitudes of the founding members of the Beauprix clan. Certainly in his attitude toward women and his unlikely friendship with Tinh Vu, he was a throwback.

Then Uncle Tinh had shown me a black-and-white print of a photo of Anthony Beauprix that the Times-Picayune had on file. It was a candid shot taken as he’d accepted the police department’s award for valor. The caption taped to the back of the photo mentioned a hostage situation and no one dying. Thanks to Beauprix. From the grainy photo, I could tell that he was taller and slimmer than the mayor, dark-haired, and had his eyes, nose, mouth and chin in approximately the right places.

More guests arrived and the area around the table became crowded, blocking my view of the room. The caterer, who still looked unharried, swept past me, switched out a nearly-empty tray of white-chocolate-dipped strawberries for a full one and disappeared back into the kitchen.

In a halfhearted attempt to keep Uncle Tinh in her good graces, I spent a few minutes brushing crumbs from the linen tablecloth before busying myself with the irises again. I had just finished stuffing a particularly gooey stem back into the vase when a nearby male voice said “the flowers” with the slight rise in tone that usually implies a question.

I lifted my head and slid my eyes in the direction of the voice.

Standing on the other side of the vase, staring in through the flowers, was a man in a tuxedo. He was perhaps six feet tall with olive skin, well-cut dark hair and hazel eyes. He was smiling with a mouthful of perfect teeth.

My first thought was that this was Anthony Beauprix. My second was to wonder who he was smiling at. My third thought was that there was only one possible candidate.

I looked quickly at my feet.

“Do you like the flowers?” Beauprix repeated.

I nodded.

“And strawberries,” I muttered thickly and for no particular reason, except that I’d always believed that distinct characteristics and a personality quirk or two were essential to creating a believable persona.

“What’s your name?”

“Olivia,” I said, wondering why he could possibly want to know my name. Impossible to think that he had seen through my disguise. Perhaps he was planning to complain to the caterer about her useless staff.

I was wrong.

“You’re doing a fine job, Olivia.”

He flashed me another smile, put the plate he was carrying down on the table, picked up several dipped strawberries from the tray and added them to the bounty on the plate. Then he frowned and looked back at me.

“If you wouldn’t mind, would you fetch me a paring knife from the kitchen?” he said.

I nodded, went on the errand and returned fairly promptly.

I watched him slice each of the strawberries on the plate into quarters, wondering at the task.

“Thank you, Olivia,” he said.

I nodded, carefully not making eye contact, and didn’t look up until he’d picked up the plate and turned away from the table. Then I lifted my head and watched him, admiring the fit of his formal wear as he moved across the crowded room, pausing to speak with one guest, then another. He had the muscular build and awareness of body and space that brought to mind a dancer. Or a street fighter. I’d met a lot of cops in the past couple of years, so there was no doubt in my mind: plainclothes had never looked so good. Though it probably helped to have a millionaire’s wardrobe and a personal tailor.

As the crowd parted to let Beauprix pass, I saw that an elderly man—Beauprix’s father, I guessed—had joined the party. He was sitting in a wheelchair in the center of the room, surrounded by a knot of people whose coloring and bone structure marked them as family. Beauprix joined them, leaning down to place the plateful of food carefully on his father’s lap. As the elder Beauprix smiled up at his son, I noticed that the right side of his face remained stiff and expressionless. When he picked up his food, he used his left hand awkwardly and chewed each small piece slowly and methodically.

I kept a close watch on the family group, remaining behind the serving table, but periodically shifting my position so that I could see them through the crowd. My job was easy. They stayed together in the same spot, chatting and laughing as their guests moved forward to greet the elderly gentleman. Periodically, Anthony would lean in close to his father and murmur something that made the old man smile.

After I’d been watching them for about ten minutes, I saw Beauprix nod and smile at his brother and sister. He signaled to the white-suited waiters to provide everyone with a full glass of champagne. While the waiters did their work, he chatted amicably with his family. Then he knelt, put his arm around his father’s shoulders and lifted his champagne glass with the other.

“To a good man, our dear friend, and my lifelong hero. Charles Beauprix.”

Anthony Beauprix wasn’t a handsome man by any conventional definition. But I doubted there was a woman in the room who wasn’t aware of him, who didn’t feel her pulse quicken as he walked past, who couldn’t imagine his hands and lips on her body. Certainly, I wasn’t immune to such thoughts. Nor was I oblivious to the effect that Beauprix was having on my libido. But I had more pressing things to think about. Such as where I was going to set a small, very dramatic fire.

A large cake, lavishly decorated with fresh and spun-sugar flowers, had been baked to celebrate Charles Beauprix’s eightieth birthday. It was several layers tall, rested on a silver-plated wheeled serving cart, and looked like it might serve a hundred people.

Beside the cart was a linen-clad stationary table that supported several large silver trays holding more dessert—dozens of uniform petit fours arranged in soldier-straight rows. Each tiny cake was covered in a smooth layer of marzipan, decorated with a single sugar rose and a pair of fresh violet blossoms, and topped by a small candle.

Toward the end of the evening, the catering staff began the task of lighting all the candles on the cake and the petit fours. Then most of the lights on the first floor were switched off and the large cake was wheeled to the center of the living room, where the Beauprix family was gathered. I stayed behind, lingering near the table that held the petit fours.

The crowd sang “Happy Birthday,” the elder Beauprix worked on blowing out the candles on his cake, Anthony Beauprix stood with his hand on his father’s shoulder and I surreptitiously dripped globs of gel fuel between rows of petit fours. As the last bits of whistling, cheering and applause faded, I tipped a lit candle into the silver tray and quickly stepped away from the table. A heartbeat or two later, there was a satisfying roar.

Someone shouted, “Fire!”

While everyone’s attention was focused on the flaming pastries, I made my way around the perimeter of the crowded room. Before the overhead lights came on, I was racing up a sweeping staircase whose grandeur reminded me of my adoptive mom’s favorite movie. Just call me Scarlett, I thought as I reached the hallway.

“His room has paintings of ships hung on the walls,” Uncle Tinh had told me. “Anthony once told me about his collection. Appropriate, don’t you think, for the descendant of a pirate?”

The second door on the left opened into the room I was looking for. Downstairs, I could hear shouting and the sounds of a fire extinguisher being discharged. That noise was muffled as I pulled Anthony Beauprix’s bedroom door shut behind me.

Time was short, so I gave the room only a sweeping glance. His queen-size bed was covered with soft bedding in shades of cream and tan, the dresser and desk were polished mahogany and the desk chair and love seat were covered with a nubby brown fabric. Tall bookcases were built in against one wall. Opposite, ceiling-to-floor guillotine windows flanked by sheer curtains in a surprising shade of tangerine let in the night air from a second-floor gallery. Paintings of tall ships and battles at sea hung on the walls, and a scale model of the U.S.S. Constitution graced the fireplace mantle.

Neat and comfortable, I thought as I crossed the room to Beauprix’s bed and knelt on the pillows. Hanging above the headboard was a gilt-framed oil painting of the Constitution defeating the British frigate Guerriére in 1812. I admired the artist’s use of blue, ochre and crimson as I swung the painting aside, revealing a vintage wall safe. The safe’s location and Beauprix’s habit of keeping his “piece” locked in the safe when company was in the house was information Uncle Tinh had provided. Information obtained from the Beauprix housekeeper’s adult daughter, whose husband liked to play the ponies. In exchange for the information, Uncle Tinh had arranged for a gambling debt to be canceled.

From my apron pocket I pulled out the electronic device. It was the size of a quarter and attached by thin wires to a pair of ear buds. I put the tiny black pads in my ears, placed the device against the safe, turned the dial slowly and listened. Right. Click. Left. Click. Right again. Click. A quick tug at the safe’s handle and the job was done.

I ignored everything else inside and went for Beauprix’s gun, a Colt .45 semiautomatic compact officer’s model. Uncle Tinh had suggested that it was exactly the item needed to get Beauprix’s attention. After returning the bullets to the safe, I tucked the unloaded gun securely between my belly and the corset-like padding I wore. Before closing the safe, I left a handwritten note inside. An invitation, of sorts. Then I went out the gallery window, shinnied down a vine-wrapped drainpipe and ran around the house to the kitchen door.

The kitchen was bustling with clean-up activity. The caterer, apparently unruffled by a mere fire, was calmly giving directions to her staff. As her back was to the kitchen door, I slouched in through the doorway. My apron was wet and soiled from my encounter with the drainpipe, so I picked up the nearest littered serving tray from the counter and tipped it toward me, adding a smear of discarded party food to my apron. Then I began scraping the remainders of crackers smeared with paté and thin brown bread topped with a pink-flecked spread into the garbage.

The caterer turned, saw me working hard, and nodded.

“Good, Olivia. Very good.”

I couldn’t help but smile.

The phone call I was expecting came near midnight. There was no warmth or humor in the deep male voice on the other end.

“City morgue,” Anthony Beauprix said. “Six a.m.”

Then he disconnected.

Chapter 4

T he ringing phone and cheerful female voice that was the Intercontinental’s wake-up service pulled me out of bed at four forty-five the next morning. Between bites of a room-service breakfast of crusty French rolls dipped, New Orleans style, in rich strong coffee, I dressed for my meeting with Anthony Beauprix.

I pulled my hair back into a French twist, applied makeup to emphasize my high cheekbones and the shape of my eyes, and put on khaki slacks, a black top and dress boots that added a couple of inches to my height. A glance in the full-length mirror mounted in the room’s tiny foyer confirmed what I already knew: I looked as unlike the slow-witted Olivia as was possible.

A taxi dropped me off in the lot adjacent to the city morgue where Beauprix was already waiting. He wore dark slacks, a blue-on-cream pin-striped shirt that definitely wasn’t off the rack and a silk tie that probably cost more than my entire outfit. He was leaning against one of the three cars parked in the parking lot at that ungodly hour. It was a standard police-issue unmarked four-door sedan, the kind that any street-savvy twelve-year-old with halfway decent eyesight can pick out from half a block away.

Beauprix’s legs were crossed at the ankle and he was smoking a cigarette. He didn’t bother moving, but watched with his head tilted as the taxi disgorged me near the entrance to the small lot.

I walked over to his car.

“Ms. Reed, I presume,” he said.

His voice was too hostile to be business-like and I suspected he wouldn’t shake my hand if I stuck it out. So I didn’t bother. I kept my own tone moderate.

“Yes, I’m Lacie Reed. Tinh Vu suggested I might be of some help to you.”

Beauprix threw his cigarette onto the pavement and ground it slowly beneath the toe of a very expensive leather shoe.

“I didn’t ask for your help,” he said. “Last night, you took something that belongs to me. I’d like it back. Now.”

Beauprix sounded like a man very used to having his own way. And his expression was clearly intended to make it difficult not to give him what he wanted. Dark, straight brows angled down over narrowed, hazel eyes; an angry flush of color underlaid his olive complexion and stained his broad cheekbones; his full lips were pressed into a thin, hard line.

Spoiled brat, I thought. But I smiled pleasantly as I replied.

“Returning your property before we talk would make it awfully easy for you to walk away. And that would make Uncle Tinh unhappy. So maybe I’ll hang on to it for just a little longer.”

“Maybe you don’t understand, little girl.” He spoke just above a whisper, and though his accent softened his vowels, he was unmistakably furious. “This is not a game and I have no intention of talking with you. If you don’t return my stolen property, I do intend to arrest you. Charge you with breaking and entering—”

There was no doubt in my mind that when he and his police buddies played good cop/bad cop, he always got to be the bad cop. Not that intimidation or bad temper was going to work on me.

“I didn’t break in,” I said matter-of-factly. “I walked in. I even spoke to you. Last night, you were charming.”

He forgot his anger for a moment as he stared at me assessingly, focusing exclusively on my face. Comparing it, I was sure, with the faces of any strangers he’d met the night before. Most people remembered features that could be changed readily—height and weight, eye and hair color, the appearance of teeth, the shape of a nose. Only the visually astute or the very well trained noticed the shape and placement of ears, eyes and mouth.

Beauprix was talented or well-trained or both.

“Flowers. And strawberries,” he said slowly, searching. “A homely woman. Kinda backward. And shy.” Disjointed detail became coherent memory. “Olivia!”

He snapped his fingers, almost shouting the name as a look of triumph and, perhaps, the slightest flicker of admiration swept his face. But his expression hardened almost immediately as his voice turned accusing.

“You! You set that damned fire! Not to mention, you scared my daddy half to death. So maybe we’ll just add arson and property damage to the list of charges—”

I lost my patience. And my temper. It was too early for such nonsense. Besides, I hadn’t had nearly enough coffee that morning. I stuck my arms out toward Beauprix, thumbs touching, wrists limp and hands palms down.

“Go ahead, Officer. Cuff me. Read me my rights. See how far that will get you.”

At that point, the sheer absurdity of the situation must have struck Beauprix. He snorted, gave his head a quick shake and waved his hand in my direction. The gesture was, at best, dismissive.

“Oh, hell, little girl!” he said. “You proved your point. And your uncle won his bet. Just give me back my damned piece and let me get back to work.”

When Uncle Tinh had suggested I remove Beauprix’s gun from his safe, he hadn’t mentioned any bet.

“Bet?” I said as irritation gave way to curiosity. “What bet?”

Beauprix seemed surprised that I didn’t know.

“The bet he and I made,” he said. “When we were arguing about whether I needed your help or not. Which I don’t. And whether you were as good as he said. Which I said you weren’t. And, well, maybe I was wrong in that regard. But, in any event, he said you’d leave a personal message for me. At my home. During my daddy’s birthday party. He said that I was naturally inclined to be pigheaded and it was worth five thousand dollars to him to prove me wrong.”

The old scoundrel, I thought. He’d used me. And it took some effort to keep my expression serious.

“You took the bet,” I said.

He nodded.

“Yeah.”

“And lost. Not only five thousand dollars, but your damned gun.”

“Yeah.”

Then I took a guess.

“And now you’re pissed. Not over the money, which is probably going to some local charity, but because the foxy old bastard outsmarted you. Again.”

He began to nod, then looked at me and grinned instead.

“Yeah,” he said, and almost laughed. “Real pissed.”

He looked down at the pavement again and gave the mangled cigarette a poke with his shoe.

“I used to have a pack-a-day habit. Now I only smoke when I’m pissed.”

I smiled back and revised my opinion of him.

“With a temper like yours, might be better if you cut back to a pack a day again.”

He thought about it for a minute, found the joke and actually did laugh. Then he stepped away from his car and began walking toward the morgue. He didn’t slow his pace to accommodate my shorter stride, but turned his head to talk to me over his shoulder.

“Come on,” he said. “I might as well show you what I’m dealing with. Then you can return my gun, pack your bags and head back up north where you belong.”

The autopsy room was cold and smelled of decay and disinfectant. Pale green ceramic tiles covered the walls and a concrete floor slanted to a drain in the room’s center. Several stainless-steel gurneys—each holding a shrouded cadaver—created an island in the center of the large room. From the doorway where Beauprix and I paused, I could see the cadavers’ feet sticking out from beneath the white sheets. Manila tags dangled from every other big toe. The two walls that ran the length of the room were lined with double rows of shoulder-width, stainless-steel drawers. At the moment, all of the drawers were closed.

We’d come in through a foyer and walked down a short hallway to the autopsy room. Just steps inside the door where we’d entered, there was a battered gray desk where a very thin Caucasian male in a white lab coat was sitting. He was bent forward over the desktop, which gave visitors a top view of thinning, slicked-back hair that was Grecian-Formula-44 dark. At one corner of the desk, nearly at the man’s elbow, was a tower of wire baskets. A basket labeled In was half empty, as was the Out box. The contents of Pending were overflowing onto a folded, greasy paper sack that served as a plate for a half-eaten ham sandwich. A soda can anchored one corner of the sack; dozens of crushed, empty cans filled the wastebasket.

Mayonnaise and yellow mustard had stained several of the papers on the desk, including the one that the man was furiously writing on as he noisily chewed the food in his mouth. He started when Beauprix cleared his throat, looked up quickly to reveal a narrow face and a blob of mustard at one end of a dark, pencil-thin mustache. The movement must have included inhaling a piece of sandwich because he spent the next minute or two choking, sputtering and finally sneezing into a tissue. He looked at Beauprix with teary eyes and I noticed that the tissue had also taken care of the mustard.

“Damn you, Anthony,” he said. “You almost give a man a heart attack.”

He began struggling up from the chair, but Beauprix stopped him.

“Don’t let us interrupt you, Joe. I know the way. If I need you, I’ll just give a shout.”

Joe flashed Beauprix a smile as he settled in his chair and went back to his paperwork.

Beauprix picked up a small blue jar of Vicks from the corner of Joe’s desk. He twisted off the metal lid and put in on the desk before using his little finger to dip into the jar’s gooey contents. I watched as he put a smear on the inside edge of each nostril. Then he casually tossed the jar to me. I caught it, followed his example, then screwed the lid back on before returning the jar to its spot.

“You won’t need these,” Beauprix said, snatching a pair of disposable gloves from a box that was weighing down the contents of the In basket. He pulled on the gloves as he walked around the clutter of newly arrived corpses, moving along the left wall as his graceful strides carried him quickly through the room. He stopped in front of a drawer in the top row, second from the far wall.

I followed more slowly, taking in details. Each drawer had a preprinted number and was sequentially numbered, with 1 prefixing the upper row and 2 prefixing the lower. Most of the drawers also had a more temporary index card with the victim’s name scrawled on it in indelible black marker. The drawer that Beauprix stood beside was labeled 15/Nguyen Tri.

Beauprix looked at me and, when he spoke, his voice was in some middle ground between concern and challenge—a male cop struggling to figure out how to relate to a woman who is not his mother, sister, lover or a hooker or a perp.

“Sure you can you handle this?” he said.

“I’m not a rookie,” I said, implying that my experience with corpses was recent and professional. Certainly the memory of those who had died around me on a small boat in the South China Sea remained vivid.

“All right then,” Beauprix said.

He pulled the drawer and it slid noiselessly open, releasing a draft that briefly intensified the cold and the smell in the room. Inside the drawer was a corpse shrouded in a dark green sheet.

Beauprix grasped the edge of the sheet, folded it back and revealed the face of a young man. Waxy yellow skin. Blue lips. Darkly hollow eyes. An angular face with a thin growth of long, silky hair on the chin and upper lip. Largish ears. Dark, straight hair clumped with dried blood.

Suddenly the autopsy room was airless and much too warm. And everything seemed to be slowly rotating….

A strong hand grasped my arm.

“Don’t you faint on me, little girl,” Beauprix said.

His voice made it a challenge.

Anger cleared my head and I pulled away from his support. I lifted my chin, swallowing the bitter liquid that had pooled at the back of my throat, and took a deep breath. The sharp whiff of menthol made it possible for me to ignore the smell that accompanied the oxygen.

“I’m okay,” I said shortly. “Get on with it.”

“Nguyen Tri,” Beauprix said. “Five foot five. One hundred twenty-five pounds. Body found below the I-10 bridge on the east side of the Inner Harbor Canal.”

He said the words as if he was reading from a clip board, as if the boy was nothing more than a number on a toe tag. I wondered if the fate of this child was nothing more to him than a job. Curiosity compelled me to lean forward and turn my head so that I could look directly into Beauprix’s face. Our eyes met.

“Tomorrow, we’re releasing the body. His family will be burying him on his eighteenth birthday,” Beauprix continued without pausing. But I knew, without a doubt, that his indifference was feigned.

I looked away, refocusing on the boy’s face. But some detached part of me was still thinking about Beauprix. About what I had glimpsed in his eyes. Could I capture that suffering, I wondered, with pen and ink? And that thought led me to wonder if I wasn’t the coldhearted monster in this vignette.

“The trauma to the head—” I began and was surprised when the words emerged as a whisper. I cleared my throat. “The trauma to the head,” I repeated. “Was that the cause of death?”

Beauprix used a gloved hand to part the young man’s longish hair.

“You see how little blood there is here, in spite of the relatively large wound? That’s an indication that the blow was delivered after the time of death. Judging from this mark here, he was struck with a sharp—”

“What killed him?” I interrupted.

“It isn’t going to be pretty….”

“I need to know.”

He pulled the sheet away.

“He was tortured. Then dumped.”

Beauprix’s voice mixed oddly with the ringing in my ears. I saw brown-encrusted punctures and slashes. Distorted hands with mutilated fingers. And a deep wound just over the heart.

My head throbbed, my cheeks and ears burned, tears blurred my eyes. Bile rose in my throat, filled my mouth. I gagged and turned blindly away, seeking escape.

I felt Beauprix’s hands on my shoulders.

“Hang on,” he murmured, and there was nothing but sympathy in his tone. “Bathroom’s just around the corner.” He guided me through the door near Joe’s desk, across the foyer and into a tiny rest room. “Go ahead. Throw up. You’ll feel better.”

Chapter 5

I entered Uncle Tinh’s hotel through a locked door on a narrow alley. The word Private was stenciled on the door, which was just a few feet removed from the entrance to the restaurant’s kitchen. During my first visit to New Orleans, Uncle Tinh had given me a key to the private door.

Unlocked, the door swung open to reveal a small foyer and a smooth wall of marble hung with two simply framed photos. One photo was in color, taken of Uncle Tinh standing in front of Tinh’s City Vu. Matted in the same frame was a newspaper article about the hotel’s recent renovation and the restaurant’s grand opening.

The other photo was older, black-and-white, and looked like a candid shot. In it, a middle-aged Vietnamese man, who I recognized as Uncle Tinh, sat at a sidewalk café sharing a meal with a group of American soldiers and journalists. He wore a uniform shirt, but the camera angle made it impossible to see his rank. Everyone in the photo was laughing or smiling.

The photo had been taken just weeks before Saigon fell to the Vietcong, Uncle Tinh had told me. Uncle Tinh was among those taken by chopper from the rooftop of the American embassy to an aircraft carrier bound for Hong Kong. From there, he had immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Evanston, Illinois. In all the years I’d known him, I had never heard Uncle Tinh speak of who or what he’d left behind.

To the left of the foyer entrance was a highly polished wood panel that, at the push of a button, slid silently open to reveal an elevator large enough to accommodate two people comfortably. I tapped a five-number code onto the keypad inside, the elevator door closed and I was taken upstairs to Uncle Tinh’s apartment—the entire fourth floor of a seventeenth-century Creole town house.