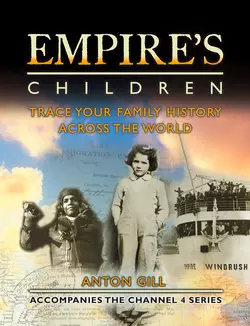

Empire’s Children: Trace Your Family History Across the World

Anton Gill

From the makers of 'Who Do You Think You Are?' comes 'Empire's Children' – a tie-in edition to a six part TV series for Channel 4 – which tells the story of Empire, and follows the personal journeys of six British celebrities as they retrace their steps through their multicultural past.British society is in every way defined by its Imperial past. It is home to 2.3 million British Asians, 570,000 Caribbeans and 250,000 Chinese. Not to mention Cypriots, Australians and southern Africans. These people represent different cultures and divergent experiences but they all share a common heritage: they are the children (grandchildren, or great grandchildren) of Empire; and their lives have been shaped by that legacy.In the second part of the 20th century, Britain relinquished control of 64 countries and half a billion subjects. During that period, many thousands of those same former British subjects fled their homes to build new lives here.What were they hoping to find? Why did they want to come to the very country they'd fought so hard to free themselves from? What kinds of lives were they leaving behind? What was the reality of their new life here? And how was British society itself shaped by their arrival and assimilation here? Real concerns that are very much in forefront of our minds in the multicultural melting pot that Britain is today.‘Empire’s Children’ seeks to answer these questions by concentrating on the personal and emotive journeys of six chosen celebrities as they retrace the steps which they – or their parents or grandparents – took in order to reach this country for the first time. The stories will cover post colonial histories of Africa, the subcontinent, the West Indies, Australasia, South East Asia and Cyprus. In some cases, they will spend some time in the former colony and experience the motivations as well as the drama of the journey itself.

EMPIRE’S CHILDREN

TRACE YOUR FAMILY HISTORY

ACROSS THE WORLD

ANTON GILL

DEDICATION (#ulink_1fb5c4ac-1159-5ad0-846d-a5d3b3f410e5)

FOR J.A.

(gratefully)

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_f039d194-3971-5f1a-b9c5-748373a9b673)

All empire is no more than power in trust

John Dryden

How is the empire?

King George V (attributed dying words)

The wheels of fate will one day compel the British to give up their empire…What a waste of mud & filth will they leave behind!

Rabindranath Tagore

CONTENTS

COVER PAGE (#ufb8fe1ee-08e4-5011-8003-01d86a50cc11)

TITLE PAGE (#udbfb9c07-a256-53df-83ad-381ff10616a4)

DEDICATION (#ue9c2ed4f-df9e-575d-8e0a-d08b371911ef)

EPIGRAPH (#ue253a8e4-5c5c-5ffa-a921-1d1ada528643)

FOREWORD (#u9a0edb7c-2244-5664-b455-3e3c3cfd8054)

PROLOGUE (#uec2ce5aa-43a2-5e91-ae27-f41519b4dbaf)

PART ONE: RULE BRITANNIA (#u1ca44411-8300-55a4-940a-b8fb6a382876)

CHAPTER 1: GOLD AND PLUNDER (#uea49e23d-fa5d-51dd-8908-bc415e62ee4b)

CHRIS BISSON (#ulink_0e4a5ecf-b531-543f-8c1f-7da135ea17e2)

CHAPTER 2: TRIUMPH AND DISASTER (#u13aa64f5-0927-580f-8da6-393aa5268c73)

DIANA RIGG (#ulink_dfffc875-1824-5d7f-a8b3-e8a57dbd7646)

CHAPTER 3: THE SECOND EMPIRE (#litres_trial_promo)

DAVID STEEL (#litres_trial_promo)

PART TWO: ALMOST INEVITABLE CONSEQUENCES (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 4: WAR AND PEACE (#litres_trial_promo)

JENNY ECLAIR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5: BEARING UP, BEARING DOWN (#litres_trial_promo)

ADRIAN LESTER (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE: TIS NOT TOO LATE … (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6: THE SECOND WORLD WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH (#litres_trial_promo)

SHOBNA GULATI (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7: LETTING GO: INDIA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8: TO SEEK ANEWER WORLD (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9: LETTING GO: THE CARIBBEAN AND AFRICA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10: AFTER THE RAJ: IMMIGRATION FROM SOUTH ASIA (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

RESOURCES (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER WORKS (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_7f17daf9-2263-5e01-bb91-1cf323d5bb9e)

This book accompanies the Channel 4 television series of the same name produced by Wall-to-Wall. It is designed to fill in the background of the stories (which are included here) told in the six television episodes, by describing briefly the rise and fall of the British Empire, but concentrating on its last days – those following the end of the Second World War – together with the impact of emigration to Britain from her former colonies, the effect of Britain on the immigrants and their effect on her, and the gradual and still incomplete journey towards integration and harmony. Recent events, including highly destructive and successful terrorism, and ill-advised and equally violent reactions to it, have interrupted the process. One can only hope that it will resume, but current damage will take a generation or two to repair.

Any opinions expressed in these pages which are not otherwise acknowledged are my own, and should not be associated with any of the individuals or organizations mentioned above, or elsewhere in the Acknowledgements.

British influence as a world power began to develop towards the end of the sixteenth century, grew to full flower in the nineteenth, and only began its long decline after the First World War, a decline which accelerated during the second half of the twentieth century.

During the entire period a number of things changed, among which place names and the British currency system are the most obviously striking. As names and references to the old British, non-decimal currency occur from time to time in the narrative which follows, it is good to be aware of them.

On 21 February 1971, the United Kingdom adopted a decimal system of currency similar to those already in use in most countries. Everyone born in the UK from the late 1960s onwards will be aware that 100 pence equals £1. It was not always thus. Before 1971, a system of pounds, shillings and pence existed. According to that system, which had been in use for centuries, there were 240 pennies (or pence) in a pound. Twelve pennies made up a shilling, and there were twenty of those in a pound. The pound was designated by the familiar £ symbol (denoting libra, the Latin for ‘pound’), the shilling by ‘s.’, and the penny by ‘d.’ (the first letter of denarius, the Latin word for a small Roman silver coin). Sums of money were expressed thus: the modern £1.25p would have been £1. 5s. Od., 25p would have been 5s. Od. or 5/-.

Apart from the shilling and the penny there were several other coins, in use at various periods, each representing other subdivisions of the pound. Those that survived to 1971 were the half-crown, the florin (2s. or 10p), the sixpenny and threepenny bits, and the halfpenny.

There is one other measurement of money that the reader should be aware of: the guinea. The guinea ceased to exist as a coin long ago, and largely disappeared as a recognized unit of payment before the watershed of 1971. Before that it was used latterly as an expression of payment of professional fees. The BBC paid contributors in guineas, and the fees of medical specialists and lawyers were demanded in them. The guinea was worth £1.05p, or £1. 1s. Od.

The origin of the guinea is interesting and has a direct connection with the early period of British dominion overseas. The coin was first struck in 1663, ‘in the name and for the use of the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa’. It was intended for the Guinea trade and was originally made of gold from Guinea, the name given to a small portion of the west coast of Africa. The splendidly named company, headed by Charles II’s brother James, Duke of York (later James II), dealt mainly in slaves. It had its ups and downs, but traded in slaves until 1731, when it switched to ivory and gold. It provided gold to the Royal Mint from 1668 to 1722. The slave trade continued to flourish until its abolition (by Britain at least) in 1807.

Place names and names of definition present a slightly more complicated problem. Names of definition change with assumptions of political correctness. Once, the term ‘Black’ was generally thought offensive, but ‘Negro’ was not, at least not to ‘white’ people. Now the reverse is true. Appalling as it seems now, people in the 1950s and earlier would quite innocently call a pet black Labrador ‘Nigger’ or a black cat ‘Sooty’ or ‘Blackie’. Most of us have come a long way towards greater integration and understanding since then, but at some cost; and sensibilities must be treated with respect as a result.

Care has to be taken with other general definitions. It is okay to call ‘Europeans’ that as a catch-all, but we are well aware that Europe is made up of a number of very different nations, languages, religious sects and cultures. That has not always been true of Europeans’ perception of other parts of the world. While the term ‘Asians’ appeared soon after the end of the Second World War as a useful umbrella-term for those peoples inhabiting what had been British India – that is to say, the Burmese, the modern Pakistanis, the modern Bangladeshis, the Sri Lankans and the Indians – nowadays the slightly more defining term South Asians appears to be preferred. The same sort of issue applies to the question of whether to use ‘West Indian’ or ‘Afro-Caribbean’ as a denomination of convenience when one cannot specify a particular island or island nation.

Such applications change with fashion and time. I have opted for those which, after consultation, seem most acceptable at the time of writing to those to whom they are applied. If any offence is caused by any reference in the pages which follow I apologize, for this is purely unintentional.

Two earlier usages which occur less frequently these days but will be found in older books, articles and so on are ‘Anglo-Indian’ and ‘Eurasian’. The former can mean either a person born in India of mixed Anglo-South Asian parentage, or a native British white (Caucasian) person who had spent a considerable time in India, usually in government or military service, possibly born there, and who would have considered India, not Great Britain, his or her principal home. The term ‘Eurasian’ denotes only the former category, that is, a person born of Caucasian-South Asian parents. I have decided in this book to use Eurasian for a person of mixed race, and Anglo-Indian for the British Indian long-termers. But be aware that the latter expression will sometimes be found elsewhere denoting the former.

Place names can change with the political climate. Look, for example, at the progression over the last century or so from St Petersburg to Petrograd, to Leningrad, and now back to St Petersburg. If you look at an atlas published in 1937 and at an atlas published in 2007 you will see a large number of name and even frontier changes, in the Russian landmass, in what was British India, and in Africa. Only British India and Africa concern us here, and almost all the dramatic changes of name there had taken place by 1980, when the last British colony, Rhodesia (earlier, Southern Rhodesia), became Zimbabwe.

One or two countries have changed their names twice or more in the past half-century. For example, the Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo, a name it shared with a neighbouring state, the former French colony of Congo. In 1966 the former Belgian territory was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo. After a period of war and unrest one political leader, General Mobutu, became dominant, and under him the country became the Republic of Zaire in 1971. (The name ‘Zaire’ derives ultimately from Nzere, a local name for the River Congo.) But, as was the case in so many newly independent African states, repression and unrest continued, and Zaire’s future was compromised in the mid-1990s by involvement in the war in neighbouring Rwanda. This led to the fall of Mobutu and the reversion under new leadership, in 1997, of Zaire to its earlier name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Many other colonies – British and otherwise – in Africa changed their names on independence, often reverting to pre-colonial or ancestral names. Thus the first to attain autonomy, the Gold Coast, became Ghana. Tanganyika and Zanzibar merged as Tanzania, Nyasaland became Malawi, Northern Rhodesia became Zambia, Bechuanaland became Botswana, South-West Africa became Namibia (as late as 1990), and so on.

The situation in what had been known as British India (prior to the end of the Second World War) changed with the end of British rule there and the political partition of the subcontinent in 1947. The original divisions were India, East and West Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon, along with a couple of the former Independent States (separate countries within the Raj but more or less in thrall to it) which had refused to become subsumed within either the new Hindu or Pakistani divisions. One of these, Kashmir, is still being fought over today. Ceylon, independent of Britain since 1948, changed its name to Sri Lanka (meaning ‘Venerable Lanka’) following a socialist revolution in 1972. A year earlier, East Pakistan (itself formerly Bengal) broke away from West Pakistan (now Pakistan (‘Land of the Pure’) and became the independent state of Bangladesh (‘Land of the Bangla Speakers’). Burma, which became fully independent of Great Britain in 1948, changed its name to Myanmar (its pre-colonial name) in 1989, and that of its capital from the westernized ‘Rangoon’ to ‘Yangon’.

I have decided to follow my own judgement in what place names to use in the pages which follow. This means on the whole that for African and South Asian countries I will use their current names, with their former colonial names afterwards in brackets where appropriate. However, in some cases I have stuck to older usages as still being more familiar to most readers. Thus, for example, although I have preferred Beijing to Peking, I have used Madras rather than Chennai, Bombay rather than Mumbai, and Burma and Rangoon rather than Myanmar and Yangon. I have also used Mecca rather than Makkah, Cawnpore rather than Kanpur, Calcutta rather than Kolkata, and Mafeking rather than Makifeng. Where any elucidation or explanation is necessary, I have given it immediately in parentheses, but in the course of telling a complex story I apologize here and now for any inconsistencies.

Where it applies (England was a separate country from Scotland until 1707 and Scotland played only a tiny part in an independent colonization process before then) I have also decided to use ‘Great Britain’ or ‘Britain’ rather than ‘the United Kingdom’ because to me the former names reflect the period better than the latter, and tie in more euphoniously with what lies at the centre of this exploration of the British Empire.

PROLOGUE (#ulink_3c9f7361-eaab-5e14-882a-e5bfc91a8f9a)

But as the debate was nearing an end, I felt I had been too harsh with the man who would be my partner in a government of national unity. In summation, I said, ‘The exchanges between Mr (F. W.) de Klerk and me should not obscure one important fact. I think we are a shining example to the entire world of people drawn from different racial groups who have a common loyalty, a common love, to their common country… In spite of criticism of Mr de Klerk,’ I said, and then looked over at him, ‘sir, you are one of those I rely upon. We are going to face the problem of this country together.’ At which point I reached over to take his hand and said, ‘I am proud to hold your hand for us to go forward. ‘Mr de Klerk seemed surprised, but pleased.

Nelson Mandela

At the end of January 2007 the Anglo-Dutch metals giant Corus, which had until a 1999 merger been British Steel, was bought by the Indian company, Tata Steel, of Jamshedpur. One hundred years earlier, when the British Empire was at its height, such a future concept would have been unthinkable. Even sixty years ago, when, in August 1947, India finally achieved its independence in a hurried and, some still argue, botched job by its last Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the idea of an Indian concern taking over a British one would have been beyond the scope of most imaginations, Indian or British. The visionary novelist Salman Rushdie, whose seminal work, Midnight’s Children, redefined the moment of independence for a new generation, could not have conceived of it when his ground-breaking work was published twenty-six years ago, when the author himself was a mere thirty-four years old.

The world has turned radically in a half-century, and in doing so it has submerged the greatest, largest and longest-lived empire that ever was, and seen the reduction of its mother country from a real world leader to one which on the one hand hangs on the coat-tails of the USA, and on the other refuses fully to integrate with its natural partners in Europe. We, the Children of Empire, still retain a memory that seems more concrete than ghostly of our powerful past, and it still influences our thinking.

But when I say ‘we’ in such a context I am immediately at fault, because there are Children of Empire who are not by descent British at all, except for the fact that the countries they or their parents or grandparents or even earlier forebears came from for generations – in some cases back to the seventeenth century – lived under the shadow and protection of the British Crown. As we settle into the twenty-first century, we must grow used to the idea that India will soon overtake China in terms of population size; and that both those countries will soon become the dominant industrial and economic powers of the world.

In the pages that follow we will hear some of their stories, but here at the beginning it is worth making one allusion to the first wave of Caribbean immigrants to British shores, in 1948, nearly sixty years ago, on the Empire Windrush. Small in number – there were fewer than 500 of them – the men and women of the Windrush, dressed in their best, who had come to seek a new life in a mother country they had always been taught to love, respect and revere, met a mixed reception. A nervous parliament prevaricated – though Prime Minister Clement Attlee stood firmly on the side of the angels – while the racist extreme right, headed by Oswald Mosley, who had previously supported Hitler’s anti-Semitic policies, foamed at the mouth. A decade later, after suffering years of poor lodgings for high rents, and a gamut of racist prejudice from the locals, the immigrants had to suffer one more great indignity – the race riots of Nottingham and then Notting Hill in the summer of 1958. Here it will suffice merely to quote from Mike and Trevor Phillips’s masterly account, largely through vox pop interviews, of early immigration to Britain, Windrush – the Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain, to give a flavour of those times:

Notting Dale differed considerably from Brixton or Paddington, and it might have been tailormade [sic] for the main event. Notting Dale had everything St Ann’s Well Road [in Nottingham] had, and more, in much larger quantities. It had multi-occupied houses with families of different races on each floor. It had a large population of internal migrants, gypsies and Irish, many of them transient single men, packed into a honeycomb of rooms with communal kitchens, toilets and no bathrooms. It had depressed English families who had lived through the war years then watched the rush to the suburbs pass them by while they were trapped in low income jobs and rotten housing. It had a raft of dodgy pubs and poor street lighting. It had gang fighting, illegal drinking clubs, gambling and prostitution. It had a large proportion of frightened and resentful residents. A fortnight before the riots broke out there was a ‘pitched battle’ in Cambridge Gardens, off Ladbroke Grove, between rival gangs, and the residents of several streets got together to present a petition to the London County Council asking for something to be done about the rowdy parties, the mushroom clubs and the violence.

Notting Dale also had a clutch of racist activists, operating at the street cornersand in the pubs. Parties like Sir Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement actually had very few members, but in the atmosphere of hostility and uncertainty which had begun to surround the migrants they provided the country with an idiom, a vocabulary and a programme of action which shaped the resentments of inarticulate and disgruntled people at various levels of society. In the week before the Notting Hill riots broke out a drunken fifteen-year-old approached a black man in a railway carriage at Liverpool Street station and was reported as shouting, ‘Here’s one of them – you black knave. We have complained to our government about you people. You come here, you take our women and do all sorts of things free of charge. They won’t hang you so we will have to do it.’

Leaving aside the peculiarity of the boy’s language after it had been filtered through various official reports, the style and content echoes precisely the rhetoric being peddled by such right-wing activists as Mosley, John Bean and Colin Jordan.

There follows an interview with Barbadian osteopath Rudy Braithwaite, who arrived in Britain in 1957:

I remember going to listen to some of the speeches that Mosley would make, you know. I was too young to really take on board what it meant when you talk about the Third Reich and all that sort of thing. And Britain is a white country and it’s for white people, and that sort of thing. That was the gist of the discussion that he would have on this little soap box. And there were a lot of people, who are very respectable now, who used to be supporters of Mosley. I could put my finger on them. I know who they are.

Very massive crowds, big crowds used to come, you know. A lot of people would follow him. I mean, he used to have his meetings on one of the side streets off Westbourne Park Road. And there were people who would really come from everywhere and listen to Mosley, you know. And it was crazy. But that happened. He was a very convincing speaker. And he spoke without a breath, he didn’t take much. He would speak and things would roll out of his mouth, so that he was very impressive. When I remember some of the things that were being said. It’s very impressive. And he said, and perhaps that is true, he used to say, ‘Many of the people who are in high places, who are politicians, would love to say what I am saying now.’

I remember those words. But they are too scared to say it because of the likelihood of jeopardising their wonderful, tidy positions. And, of course, that was borne out by Duncan Sandys [a right-wing Tory MP and minister with a chequered career], who talked about ‘polka-dot grandchildren’. And Gerald Nabarro [a right-wingTory MP and notorious roué of the 1950s and 1960s, mainly famous for his handlebar moustache], who couldn’t even drive on a main street without driving up the wrong way. Yet he got away with it, his racism. He was very blatant about his racist behaviour.

The Empire Windrush, by the way, set off on her final voyage in February 1954, sailing from Yokohama and Kure to the United Kingdom with 1,500 wounded UN soldiers from the Korean War. The battered ship, long past her best, took ten weeks to make Port Said, and she was later condemned.

Prejudice of a different kind hit Britain hard nearly fifty years after the Notting Hill riots, and the form it took is indicative of how radically and dramatically our culture has changed within a generation.

During the London rush hour on 7 July 2005 four bombs exploded, three on the underground at 08.50, and another on a Number 30 bus in Tavistock Square, not far from Euston Station, an hour later. Fifty-two innocent people were killed, and more than 700 injured, some seriously disabled for life. The four suicide bombers were young Muslim men, all of whom were British citizens and all of whom would have had a perfect right to identity cards – the introduction of which as a means of countering terrorism is clearly invalid.

The London bombing (a similar attack was launched in the same city a fortnight later, but miraculously failed) was the third in a series which started with the destruction of the World Trade Center by Al Qaida in New York in 2001 (3,000 dead). The second was the bombing of the Madrid rail system on 11 March 2004 (191 dead, 1,700 wounded).

We can see how long a shadow an empire, even in its last stages, can cast. England has been no stranger to bomb attacks in its recent past anyway, perpetrated by the IRA, and these outrages were also ultimately the result of decisions made decades earlier and perpetuated in the name of the Empire, largely because irreconcilable differences had been created.

It is true that following the bombings young Muslim men, or indeed anyone with similar looks, ran the risk for a time of being regarded with fear and suspicion. But there were no significant race riots such as those that had occurred four years earlier in Oldham and other major cities in northern England. There were race riots in Birmingham in October 2005, but the confrontations then were not between whites and blacks but between Afro-Caribbeans and South Asians, where the former local population is predominantly Christian and the latter predominantly Muslim. The riots, which took place over the weekend of 22/23 October, were triggered by rumours that a black teenage girl had been raped by a gang of Muslim men.

Violent outbursts of this type have occurred from time to time ever since immigrants from the former British colonies began to arrive in noticeable numbers after the end of the Second World War. The first major race riots – not officially recognized as such – were those of Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958. Though the Notting Hill Carnival came into being (in 1959, in St Pancras Town Hall) as a reply to the Notting Hill riots, tensions remained for many years after that. I can still remember the kind of looks I got when I was going out with a Guyanan girl in London in the mid-1960s.

We have – hopefully – come a long way since then. Most people, wherever they have come from, just want to get on with their lives, look after their families, have a more-or-less congenial job, and so on. That is self-evident. It is the few who muck things up for the many, and the many either have to put up with it or suffer. The people of Iraq, who as I write suffer outrages like the London bombs on a daily basis, are no different from anyone else in that respect. Prejudice against foreigners is endemic but it is essentially rare, and it is the child of propaganda. Many Muslims are in as great danger of tarring us white ‘Christians’ with the same sort of brush that we can be in danger of tarring them with. (And we should also be aware that as early as 1995 the French secret service had invented a nickname – ‘Londonistan’ – for our capital, as a result of their suspicion that it was a breeding ground for terrorists operating in Algeria; our reputation not helped by an initially, no doubt commendably liberal, but perhaps ultimately ill-advised indulgence towards such extremists as Abu Hamza al-Masri.)

The victims of the bombs in London, as they would have been in any concentrated multi-ethnic community, were random ones. Several members of what we still call ethnic minorities, including Muslims, inevitably died alongside ‘native’ Britons – something the bombers must have known. The hospital doctors and nurses who looked after the injured counted many non-ethnic Britons in their number. There was little racist reaction: we were united in common shock, outrage and grief. Ironically the most naked prejudice today – often stirred up by sections of the press – is against immigrants from the former Soviet bloc. But there is no stopping the tide, or the constant fluidity of demographics. The British Empire aside, an article appeared in the Evening Standard on 13 November 2006 pointing out that one-third of Londoners today were born outside Britain. This is a good thing. We should not forget that immigration has essentially enriched the country, not threatened or impoverished it. We had better get used to it, and the good news is that, slowly but surely, we are. This is only fair, since the British are a mongrel race anyway – and it is arguably that which has given them their edge in the past.

Britain is, generally speaking, a tolerant nation, though racism in many forms still exists. A thirty-five-year-old black London cabbie recently told me that when he was doing ‘the Knowledge’ his examiners – mainly ex-policemen – would tell him to drive to such destinations as Black Boy Lane (N15) and Blackall Street (EC2). However, there are some positive signs. About a year ago, I was pleased, if not 100 per cent convinced, by the optimism of a British-born Pakistani friend, who has had her share of racial abuse, who told me that she felt she was now living in a country whose institutions had become much more liberal in the last decade or so. She is about forty, and it seems to me, half a generation older, that a growing familiarity with other cultures is leading to a greater sense of ease. Many people have a South Asian doctor. Almost all city-dwellers have a South Asian corner shop or newsagent, or have eaten at one time or another in an Indian or Chinese restaurant. London probably has the greatest choice of cuisines of any city in the world, and Birmingham certainly has among the very best Indian restaurants. Many of our sporting heroes and heroines, whether they are athletes, cricketers or footballers, are of South East Asian, African or Afro-Caribbean origin. The Afro-Caribbean contribution to popular music since the late 1940s has been nothing short of revolutionary. Famously, chicken tikka masala (devised with the British palate in mind) has supplanted fish and chips (originally a French concoction) as the ‘national dish’.

It is probably true to say that most people born since, say, the mid-1960s – people who are now middle-aged – have greater tolerance than their parents’ generation, and their children will hopefully be more tolerant still – on both sides. After all, a large number of people of African, Afro-Caribbean and South Asian stock living in Britain today were born here, the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Empire, and the flowers on the grave of that once mighty organization. And if it is depressing to reflect that the current leader of the British National Party was only born in 1959, it is also worth remembering that he was influenced in youth by his parents, and that the BNP has nothing like the clout of, for example, its Austrian or its French counterparts (the latter itself inexorably losing ground), and that Britain can at least be proud that it has never contained a political party of the extreme racist right which has had more than a derisory following, even in areas where ‘blacks’ now outnumber ‘whites’. When the BNP leader was recently (in November 2006) acquitted (by an all-white jury) of charges of racial incitement, the official reaction of the government was an undertaking to reexamine ‘race hate’ laws.

There are still spheres of official life in Britain that are tainted by institutional racism, but in other public areas our record is good. In the sixties and seventies, sitcoms such as Love Thy Neighbour and Till Death Us Do Part dealt uncomfortably with the existence of racism. Although written from an ostensibly liberal point of view, and aspiring to show as ridiculous the characters who exhibited racism, all too often it was the non-European immigrant characters who were the butts of the jokes, and an uneasy sympathy sometimes bolstered the unpleasant protagonists. Such shows now seem to belong to a different planet. British television has nurtured a number of Asian and Afro-Caribbean sitcoms and series – from Empire Road by Michael Abbensetts and broadcast in the late 1970s to Meera Syal’s The Kumars at No. 42 and Goodness Gracious Me. That television is almost painfully aware of its responsibility is borne out by an article by Mark Sweney in the Guardian of 9 November 2006, detailing the results of an investigation carried out by the Open University and the University of Manchester for the British Film Institute (entitled ‘Media Culture: The Social Organisation of Media Practices in Contemporary Britain’), which found that programmes such as Coronation Street, A Touch of Frost and Midsomer Murders have little appeal for members of the non-white ethnic minorities resident in Britain. It is a difficult gap to bridge, for portrayal of the predominantly white communities in the latter two programmes is still valid; oversen-sitivity to the sensibilities of ethnic minorities could be detrimental to harmony.

Britain has a good record too in the field of television journalism, at least in the area of news presentation, where, especially at the BBC and Channel 4, a large proportion of presenters in all fields belong to non-white ethnic minorities. This invites very favourable comparison with the situation in most other European countries. France, for example, has one black female newsreader on France 3, though ethnic minorities are better represented on the new twenty-four-hour news service. In politics and sport, Africans, Afro-Caribbeans and South Asians enjoy a high profile. This is not necessarily new. The first Asian MP, Dadabhai Naoroji, a Parsi, was Liberal Party MP for Finsbury Central for three years from 1892. Maharajah Kumar Sri Ranjitsinji Vibhaji made his cricketing debut for Sussex in 1895. Not that such men’s achievements were anything but unusual for decades to come; nor were either politics or sport untainted by racism. In the year Naoroji lost his seat, Sir Mancherjee Bhownaggree won Bethnal Green for the Conservatives. Bhownaggree, a Parsi lawyer, was far from radical. He supported British rule in India and earned the nickname ‘Bow-the-knee’ from his Indian opponents. But the MP he replaced, a trade unionist called Charles Howell, was indignant that he had been ‘kicked out by a black man, a stranger’. Seventy-three years later, the Conservative MP Enoch Powell distinguished himself by delivering perhaps the most racially inflammatory mainstream political speech of modern times.

In sport, as recently as 2004, the former player and manager Ron Atkinson, who twenty-six years earlier had distinguished himself by the pioneering introduction into his West Bromwich Albion team of three Afro-Caribbean players – Brendan Batson, Laurie Cunningham and Cyrille Regis – disgraced himself when commentating by describing the black French player Marcel Desailly as: ‘He’s what is known in some schools as a fucking lazy thick nigger.’ For all that this may have been an isolated event, such a lapse in public can no longer be tolerated and Atkinson lost his jobs at ITV and on the Guardian instantly. The athlete Linford Christie has pointed out that when he won races, the press described him as a British athlete; when he lost them, he was either an immigrant or a Jamaican.

Christie came to Britain aged seven. For his services to athletics he was awarded, and accepted, the OBE. Meera Syal, born here, accepted the MBE in 1997. But the poet Benjamin Zephaniah, also born here, turned his down in 2003, defying convention by doing so publicly, and giving as his reason that it, and its association with the Empire, recalled to him ‘thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised’. This sparked a discussion about whether the ‘Empire’ gongs should be dropped altogether, though this is unlikely to happen soon.

There is no doubt that elsewhere a dark ghost of Empire remains, exemplified recently by the trial, still ongoing as I write, of Thomas Cholmondeley, heir to the Delamere fortune. The Delameres are an aristocratic family who have farmed in Kenya since the 3rd Baron arrived there in 1903, and they own huge tracts of land, appropriated from the Masai, in the Rift Valley. Their name is associated with the Happy Valley set, which became notorious through the book and film of the same title White Mischief. They do not have a high tradition of tolerance with regard to native Kenyans.

In April 2005, game warden Samson Ole Sisina, aged forty-four, was killed by the then thity-seven-year-old Cholmondeley on the Delamere family’s ranch near Lake Naivasha. Sisina was armed, and dressed in plain clothes, as part of an undercover investigation into the illegal trade in bush meat. Cholmondeley maintained that he shot the warden through the neck, but in self-defence, believing him to be a robber. Local whites immediately said it was the result of police failure to tackle a spate of car-jackings, burglaries and murders. Cholmondeley was acquitted, but in 2006 he was arraigned again on the charge of shooting another black Kenyan dead. This time, Cholmondeley claims that he mistook Robert Njoya for a poacher.

Matters remain tense. Assistant Minister of State Stephen Taurus told mourners at Njoya’s funeral that ‘it is time for these white settlers who are killing our sons to be kicked out of the country’.

PART ONE ‘RULE BRITANNIA’ (#ulink_a9a6f0a2-9c01-5fb2-8c72-fd48357c4cc1)

JAMES THOMPSON

CHAPTER ONE GOLD AND PLUNDER (#ulink_4e13b55f-24a5-5053-8651-97cdd818170b)

Not only did it last far longer than any other in modern times, but at its height the British Empire was also the largest the world had ever seen.

THE EMPIRE REACHED ITS GREATEST EXTENT WHEN BRITAIN COMMANDED AROUND 500 MILLION PEOPLE

The British Empire reached its greatest extent, ironically some time after its decline had set in, in the wake of the First World War, when Britain commanded nearly 40 million square kilometres of the earth’s landmass and around 500 million people – about a quarter of the planet’s terrain and about a quarter of the world’s population at the time. Look at any world map published around the turn of the last century, and you will see a huge part of it marked in red, the colour of the Empire. Red stretches in a more-or-less unbroken swathe from the Yukon in the north-west to New Zealand in the south-east. When it is 6.00 a.m. in the extreme north-west of Canada, it is 2.00 p.m. in London and 3.00 a.m. the following day in Auckland. This great sweep of land, with its massive population, comprising scores of different nationalities and races and hundreds of different languages, was truly ‘the empire on which the sun never sets’.

That Empire is gone, but its legacy is immense, and its effects are still felt in almost every corner of the world. Sir Richard Turnbull, among the last governors of Tanganyika and of Aden, once cynically told my mother that the Empire would leave behind only two traces of its existence, the game of football and the expression ‘fuck off’. That is understating the case. To take one other frivolous example (and many would argue with my choice of that adjective immediately), the game of cricket, whose origins in England go back at least as far as the sixteenth century, is only played as a serious professional game in countries across the world which were once part of the Empire. In the case of the Caribbean island states, it is a game they have made their own and at which they famously trounced the mother country first as early as 1950. In more mundane areas, British approaches to civil and military administration, and law, have taken root and continued to develop in countries that were once ruled by Britain, their efficacy underpinned by the fact that, for all their faults, the British were able to run their Empire with relatively small numbers of soldiers and civil servants. Techniques of commerce and banking (adopted from the Dutch and the Italians) evolved in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have continued to influence international trade. And the greatest legacy of the Empire is the English language.

THIS GREAT SWEEP OF LAND WAS TRULY’ THE EMPIRE ON WHICH THE SUN NEVER SETS’.

But what was all this built on? What was the lynchpin for the English (and later the British) to acquire and maintain their Empire? The answer is sea power. With the development of aeroplanes during and after the First World War and rocketry during the Second, the importance of the Royal Navy and its strategic ports across the world declined. Though ships and submarines as missile carriers would still make their contribution, the new craft could stay at sea for long periods. In the case of the submarines their whereabouts could be kept totally secret. They had no need of the old bases. The Empire was originally founded on maritime dominance. When this became a less important factor in world politics, and when other countries began to overtake us industrially, economically and in the development of new military technology, the Empire became far less easy to maintain.

One of the first monarchs to encourage overseas exploration was the Portuguese King Henry, called ‘the Navigator’, under whose sponsorship Portugal took and colonized the Azores as early as 1439. Having a west-facing coastline it was logical that the first line of travel should be westwards, and Henry’s explorers were soon followed by others. The Portuguese were great seafarers, and their development of shipbuilding technology would be closely followed by the two other European seafaring nations.

Exploration in the name of enrichment and the extension of power was what motivated the early navigators. Spain was not slow to follow Portugal in setting forth across the Atlantic, commissioning the (probably) Genoese sailor Cristóbal Colón (Columbus). He made four voyages westwards between 1492 and 1504, making landfall in the Caribbean and on the coast of Central America.

The idea that the earth was a sphere, and not flat, was widely acknowledged, and had been for centuries. As early as the beginning of the Christian era the earth’s spherical shape was accepted by most educated people in the West. The early astronomer Ptolemy based his maps on the idea of a curved globe and also developed the systems of longitude and latitude. Although arguments in favour of a flat earth still persisted, the modern idea that people in the Middle Ages generally believed in it is actually a nineteenth-century confection. A land route to the east had been well established since antiquity, and the Ancient Egyptians were already importing lapis lazuli – a hugely expensive luxury – from Afghanistan. But the development and refinement of the ocean-going ship opened a world of new possibilities. Rumours of great wealth overseas, and of the legendary Christian kingdom of Prester John, fired the imaginations of kings and explorers alike. Soon after Colón’s voyages, the Spanish realized that the lands he discovered did not belong to Asia as had been expected (his aim had been to find a westward route to the Spice Islands) but to an entirely new continent; and the reports he brought back of it were promising.

Although the Portuguese Vasco da Gama established a passage around the coast of Africa and the Cape of Good Hope to reach the south-eastern tip of India at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the main thrust of exploration by sea concentrated on the faster westward route, the theory being that one would reach lands of great wealth ‘somewhere off the west coast of Ireland’. The rivalry between Portugal and Spain needed some formal regulation, and Pope Innocent VIII presided over the negotiations which led to the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. It declared that all the undiscovered world to the west of a north – south meridian established about 1,550 kilometres west of the Cape Verde Islands should be the domain of Spain, and all of it to the east should be Portugal’s. The line, about 39° 50’ West, was not rigidly respected, and Spain did not oppose Portugal’s westward expansion into Brazil, which is why Brazilians speak Portuguese and the rest of South America speaks Spanish, but a demarcation was established.

It was far from the last time Western European countries would loftily carve up the rest of the world by treaties and edicts with no reference either to the people who lived there, or, often, to each other. Possession was nine-tenths of the law, and native inhabitants, whom they quickly found relatively easy to crush, the more so since they had no gunpowder, were there to be exploited or evicted. The first explorer to show real sympathy for or interest in local peoples was William Dampier in the latter half of the seventeenth century. (He was quite a man: pirate turned explorer-zoologist-hydrographer, he identified, plotted and traced the trade winds and published a book on them which stayed in use until the 1930s. No wonder Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn invited him to dinner.) The first circumnavigation of the globe was accomplished between 1519 and 1522 by the ships of another Portuguese, Fernão de Magalhães (Magellan), though he himself died in the Philippines and so did not complete the voyage. A new route, though a perilous one, cutting through what is now called the Magellan Strait, in Tierra del Fuego just to the north of Cape Horn, was thus established, and a new ocean opened up, which Magalhães named Mare Pacifico – the Pacific Ocean – because of the apparent calmness of its surface. The impact of this discovery on human history (together with the stories Magalhães’s surviving crew brought back when they finally returned home) was probably the greatest since that of fire or the wheel.

THE SPANISH REALIZED THAT THE LANDS COLON DISCOVERED BELONGED TO AN ENTIRELY NEW CONTINENT, AND REPORTS WERE PROMISING.

Meanwhile England, the other emergent maritime power of the time, had not been slow to pick up on the activities of Portugal and Spain. King Henry VII engaged another Genoese (some say he was Venetian), Giovanni (also known as Zuan) Caboto, to undertake a westward-bound voyage of discovery on his behalf, famously giving him:

full and free authoritie, leave, and power, to sayle to all partes, countreys… of the East, of the West, and of the North, under our banners and ensignes, with five ships… and as many mariners or men as they will have in saide ships, upon their own proper costes and charges, to seeke out, discover, and finde, whatsoever iles, countreys, regions or provinces of the heathen and infideles, whatsoever they bee, and in what part of the world soever they be, whiche before this time have beene unknowen to all Christians.

John Cabot, as we call him, set off in 1497, after a false start the year before, and became perhaps the first European to set foot on Newfoundland since the semi-legendary Viking voyagers of about 500 years before (we only know for sure that Erik the Red reached Greenland, but he or his successors may have got further, and there is evidence to suggest it).

Henry had sent Cabot, hot on the heels of the Portuguese and the Spanish, in search of something more than a large northern offshore island – and Cabot himself had meant to make landfall further south. The myth of El Dorado did not become current until thirty years later or so, but people’s imaginations had been fired by the possibilities of great wealth in the brand new continent that they suspected lay beyond the coastline they had hit. Cabot, it later turned out, had discovered wealth of another kind: the most fecund stocks of codfish in the world. In any case, he claimed Newfoundland for England. She had a foothold.

Henry VII was an extremely shrewd, financially alert monarch, and quick to realize that an investment in sea power would be a wise one. He accordingly started to build up his navy, a task which his son, Henry VIII, who succeeded him in 1509, took over with enthusiasm.

During the first half of the sixteenth century the Spanish developed colonies in the Caribbean, conquered Mexico, and began to make inroads into the continent of South America. Spanish galleons soon began to bring back gold and other treasures from the New World, and King Carlos V became a rich man, aiming at world power. At the same time, Henry VIII instituted the English Reformation and withdrew from the Roman Catholic Church. Envious of Spanish success, and also worried by the threat of overweening Spanish power, the English now began to see themselves as the potential champions of a Protestant Europe.

ENGLAND HAD BEEN GROWING EVER MORE CONFIDENT AS A NAVAL POWER AND THERE CAME A FLOWERING OF BRILLIANT ENGLISH SEAFARERS.

This ambition was checked by Henry’s ultra-Catholic daughter, Mary, whose reign saw England in danger of becoming a vassal of Spain, and it was not until Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558 that the Church of England finally became properly established.

During this time, however, England had been growing ever more confident as a naval power and in response, perhaps by one of those accidents of history, perhaps because so great an opportunity was there, came a flowering of brilliant English seafarers. Many of them – and the politicians who backed them – were also staunchly anti-Catholic and anti-Spain. Elizabeth had no desire to see Spain remain in the ascendant unchallenged, but she had inherited a weak exchequer. In order to fill her coffers and undermine Spanish power, she condoned, semi-officially, what amounted to a campaign of piracy. If Spain had stolen a march on England and colonized lands which were a source of gold, then England would take her gold from her when and where she could. The propagandist and chronicler for all this activity was Richard Hakluyt, whose Voyages remain essential reading for any serious student of this period. And pirates did not only take gold. Where they could, they relieved the Spanish of their charts, which were worth more, since they traced coastlines and showed harbours, which the English had no knowledge of.

It was not simple piracy, of course – only Spain was officially targeted – and the men who carried out the campaigns ranged from bold adventurers and explorers like Sir Francis Drake, through Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Sir John Hawkins, to the cultivated and sophisticated Sir Walter Ralegh, whose last disastrous venture to South America in search of Eldorado, for the unpleasant King James I, was to cost him his life, as a sop to the King of Spain. In the course of his adventures, Drake became one of the earliest circumnavigators of the globe (1577–80) and the first to complete the voyage as commander of his own expedition from start to finish. Hawkins contributed many technical improvements to warships, and is now credited with introducing both tobacco and the potato to England. On a less noble note, he was also the first English mariner to become involved in the nascent slave trade. Ralegh founded the first British colony in North America on Roanoke Island, just off the coast of what was then the putative colony of Virginia (named in honour of Elizabeth, who had granted Ralegh a charter to claim land in the New World in her name). It was not a success at first, but it established what would become a permanent British settlement in the Americas. However, for all their efforts, the English never did find gold of their own in the Americas. Even the potato did not become popular for two centuries, though tobacco did. It was the first money-making product to come to the Old World.

Spain found herself plagued by English ships in the Pacific, in the Atlantic and in the Caribbean, and decided in the end to punish the unruly northerners once and for all. There were other political and religious matters which forced the issue. Elizabeth was a nimble diplomat, managing to string Spain along for years with the possibility of an alliance by marriage, and keeping Mary Queen of Scots, her cousin and Catholic rival, and a Frenchwoman in all but name, alive as long as she could. But the plots against Elizabeth which centred on Mary could not be ignored or foiled for ever, and Elizabeth finally, reluctantly, had her executed in 1587. A strong response from Spain was inevitable, but the ill-advised and unlucky venture of the Grand Armada against England came to grief spectacularly in 1588. It confirmed the superiority of English seamanship, and from 1588 on England began to establish itself as the leading maritime power of the world, a position Britain was to maintain for three centuries.

The Elizabethans sowed the seeds of colonization, and by the 1620s Virginia was beginning to boom on the back of successful tobacco exports, just as, in a more modest way, a colony established in Newfoundland thrived on the cod fishery business. But in 1620 a new kind of settler arrived in what is now Massachusetts.

Puritans, who sought a plainer form of worship than the Church of England, which still maintained many of the trappings of the Catholic faith, began to feel the weight of religious prejudice on account of their nonconformist attitudes. As a result a group of them sought refuge in Holland, where they enjoyed greater freedom, but not the full autonomy they desired. After a decade or so they returned to England and, having obtained a grant of land from the Virginia Company which ran the colony there, set sail for the New World on the tiny Mayflower, along with a number of other immigrants. The Mayflower was blown off course and made landfall far to the north of Virginia, and the Pilgrim Fathers, as they came to be known, founded a colony where they landed. They were the first Europeans to settle on that coast, and had a hard time of it at first, but they stuck it out and eventually prospered, establishing farms and gradually spreading inland. About fifteen years later, Catholic religious exiles would form a colony which they called Maryland, in honour of Charles I’s queen, Henrietta Maria. The English were now firmly established on the east coast of North America.

JUDGED BY EUROPEAN STANDARDS, THE LOCALS WERE ‘BRUTE BEASTS’, AN INCONVENIENT THORN IN THE COLONIZERS’ SIDE.

Contact with the local inhabitants – the Native Americans – was limited and generally unfriendly. The Spanish had managed to destroy huge numbers of the local populations they encountered with guns and – less deliberately but more effectively – with imported European diseases against which the locals had no natural resistance. Judged by European standards, and it would be a long time before anyone took an anthropological interest in the peoples of the colonized countries, the locals were ‘brute beasts’, who needed to be converted to Christianity and/or destroyed as an inconvenient thorn in the colonizers’ side. Shakespeare’s Caliban in The Tempest – itself in part a reflection on colonization – shows a sympathetic (for its time) take on the ‘native’. And when emotional and personal contact was made, it was rare enough to enter into modern myth. The Native American princess Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, born about 1595, married an Englishman, John Rolfe, and returned to England with him and their son, Thomas, where she lived in Brentford. She was presented at Court, but later fell ill, and died at the beginning of her return voyage to Virginia in 1617. A few more exotic outsiders arrived here in the course of the century, prompting such literary responses as Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko, and Defoe’s Man Friday – who, however, kept his place.

England, still at loggerheads with Spain, had had an eye on the Caribbean islands since John Hawkins first took captured Africans there from Guinea and sold them to the Spanish as slaves to work the land (the native populations having largely been killed off). In 1627, Charles I granted a charter to settle the uninhabited island of Barbados and establish tobacco plantations there. They did not work, but tobacco was replaced with sugar cane and the sugar industry boomed. Then, in 1655, an army sent by Oliver Cromwell took Jamaica from Spain. Ravaged by dysentery and malaria, the first settlers held out on account of the money to be made, and the sugar plantations established there soon demanded an immense workforce, not least because life for the workers was hard and short. Initially, a system of indentured servants was introduced, generally poor people from the homeland who undertook to work for a fixed term – three to five years – on a very modest wage, in return for their passage out and their keep. These people endured extremely harsh conditions and were treated no better than serfs. Some went voluntarily to escape even grimmer or hopeless conditions at home; others were kidnapped – ‘bar-badosed’. Many Irishmen and women suffered this fate after Cromwell’s crushing campaigns in their country, one of England’s first and most abused colonies. Few lived long.

It was not a system that worked well, and it became harder and harder to fill places left vacant by the high mortality rate. Increasingly, Spanish and English planters in the Caribbean looked for a new source of labour, and in that search a new international trade was truly born.

The slave trade was so successful that it lasted from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, formed the basis for the prosperity of such towns as Liverpool and Bristol, and made the fortunes of large numbers of individuals. Slavers were proud of their trade, saw nothing wrong in it, and one even had the figure of a slave incorporated in his coat of arms.

It was so profitable because the ships which plied it were never out of use. A ship would leave England for the coast of West Africa loaded with finished goods such as firearms, stoves, pans, kettles and nails, along with iron bars and brass ingots. These would be traded for slaves rounded up in the interior by local, often Arab, traders, but also provided by local chiefs from the prisoners taken in local wars. The slaves were densely packed into the holds of the ships in dismal conditions, but enough of them survived the crossing to make a profit for the traders, who, having sold their cargoes in such places as Barbados and Jamaica, but also trading with the Spanish since political enmity and religious difference have never cut much ice with profit, then loaded their ships with refined sugar or tobacco to take back home. This was known as the triangular trade, and may be responsible for the fact that the British sailor employed to sail the ship had an even greater likelihood of death en route (usually from yellow fever, malaria or scurvy) than the slave. By 1700, it was estimated to be worth £2 million in contemporary terms – perhaps a hundred times that or more in modern money. Because the death rate was high, and because even when slaves bred the rate of infant mortality was high, demand for replacements was inexhaustible. Eric Williams, a former prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago and a historian of the Caribbean, gives an example from Barbados which is worth quoting: ‘In 1764 there were 70,706 slaves in the island. Importations to 1783, with no figures available for the years 1779 and 1780, totalled 41,840. The total population, allowing for neither deaths nor births, should, therefore, have been 112,546 in 1783. Actually it was 62,258.’ The slave population therefore was smaller by 8,448 people than it had been nineteen years earlier.

Chillingly, the slaves were referred to as ‘product’, in rather the same way as the Nazis later referred to the Jews. Rebellious slaves (and there were several rebellions) suffered vicious punishments, and those who stole sugar cane to eat themselves could, if caught, look forward to being flogged, to having their teeth pulled out, and to other cruel humiliations, as one Jamaican estate owner noted in his diary in May 1756, having caught two slaves ‘eating canes’: ‘Had [one] well flogged and pickled, then made [the other] shit in his mouth.’ Slaves who escaped headed for the hills where they formed their own communities, governed by a system of laws developed by themselves. The British, borrowing a word from the Spanish cimarrones (peak-dwellers), called them ‘Maroons’. So successful and independent did these communities become that the British, despairing of destroying them, eventually concluded treaties with them, and, ironically, engaged them to hunt down other escaped slaves.

THE SLAVE TRADE CONSTITUTED ONE OF THE GREATEST MIGRATIONS IN RECORDED HISTORY.

In the course of the eighteenth century, when the slave trade peaked, more than 1,650,000 people were uprooted, shipped and sold. The slave trade constituted one of the greatest migrations in recorded history. In England itself, and especially in London, there was a sizeable black population – Simon Schama tells us that there were between 5,000 and 7,000 in mid-eighteenth-century London alone. All of them were technically free, while resident in Britain, under the law, but many, despite the intervention of early activists such as Granville Sharp on their behalf, were cruelly abused by their employers. Some, like Dr Johnson’s servant, Francis Barber, enjoyed the benefits of education and became minor celebrities. Others, especially young men and boys, were often employed in aristocratic houses as pages – the modern equivalent of fashion accessories, dressed in exotic costumes believed suitable to their backgrounds. Yet others eked out a precarious living as musicians or waiters. There were a few soldiers and sailors. For women, the choice was stark: most only had recourse to either begging or prostitution.

ABUSE OF COLONIZED PEOPLES AND OF FORMER SLAVES CONTINUED EVEN LONGER. IN SOME PLACES, IT CONTINUES TODAY.

By the end of the eighteenth century, an abolition movement gathered momentum in Britain. A medallion was struck by the pottery magnate Josiah Wedgwood in the 1790s showing a kneeling, chained slave, and bearing the legend ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’, which did much to popularize the cause; and its supporters succeeded in bringing about an end to the slave trade and then slavery itself by Acts of Parliament passed in 1807 and 1833. The institution itself did not die out instantly. It lingered long in India, and in the former British colonies in America it would survive for another thirty years at least. And abuse of colonized peoples and of former slaves continued even longer. In some places, it continues today. The descendants of slaves, of course, form the majority of the populations of the Caribbean states today.

England was not only expanding in the western hemisphere. Coffee – its name derives from the Arabic qahwah – spread to Europe from the Muslim world (its origins in antiquity are in Ethiopia), and towards the end of the seventeenth century it became an immensely chic, and expensive, drink in London, where coffee houses blossomed almost as fast as chains like Starbucks do today. Tea – even pricier – followed, imported from China. Chocolate, much drunk in the eighteenth century, quickly followed. These new and popular tastes for the exotic suggested new markets. The Dutch had established trading links with the Spice Islands of south-west Asia at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and colonized them under the aegis of the Dutch East India Company. Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to the Royal East India Company in 1600, according it the usual high-handed carte blanche, irrespective of any other nation. Rivalry between the Dutch and the English concerns simmered throughout the 1600s, leading to a string of Anglo-Dutch wars towards the end of the century, but resolved by the accession of William of Orange to the British throne in 1689. The French East India Company established a base at Pondicherry (now Puducherry) in 1673, creating further rivalry as the trading possibilities opened up in India began to promise rich rewards.

The English established trading stations in Surat, in what was to become Madras (now Chennai) and in what was to become Calcutta. In 1661 Charles II of England received Bombay (now Mumbai) as part of the dowry due on his marriage to the Portuguese Catherine of Braganza. The Portuguese had colonized the Goan coastal strip over one hundred years earlier. ‘Bombay’ derives from the Portuguese bom baia – ‘good bay’. Much of the rest of India at the time was under the control of the fading Mughal empire (one of the last great emperors, Shah Jahan, created the Taj Mahal as a tomb for his wife in the middle of the seventeenth century), but the subcontinent was also divided into petty kingdoms whose warlike rivalries worked to the advantage of the European interlopers.

Trade dominated here initially, not colonization, and far from encountering unsophisticated tribes who could easily be dominated, the local peoples here were organized and powerful. Initially, the Europeans stuck to their coastal trading stations and bickered among themselves. The sea voyage east had to be made via the Cape of Good Hope (where Britain also established coastal bases) and was considerably longer (six months) than that to the Americas (about eight weeks), so East India Company officials enjoyed a great degree of latitude and independence, often making private fortunes on their own account.

The process by which India gradually fell under exclusively British control is long and complex, but, briefly, the Dutch were outmanoeuvred because they had a less versatile range of goods to trade with. The French, whose main centre was at Pondicherry, just south of Madras, ultimately foundered when the ambitious governor of the Compagnie des Indes, the Marquis Dupleix, fell foul of one of the first great heroes of the British Empire, Robert Clive. Clive, a severely flawed and pugnacious character who was to commit suicide (succeeding at the third attempt) at the age of forty-nine in 1774, was nevertheless a brilliant soldier and an able and astute administrator and negotiator. When the equally truculent Dupleix, with the aid of Indian allies, took Madras (then called Fort St George) in 1746, Clive recaptured it, and went on to take Pondicherry from the French, effectively neutralizing their influence. Not long after this campaign (1751–3), Clive, after a brief interval in England, returned to India to crush another enemy.

In 1756 the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj Ud Daulah, became disaffected with the East India Company’s interference in the internal affairs of his country, and sensed (correctly) a threat to his independence. In June 1756, he ordered an immediate stop to improvements in the fortifications of Fort William in Calcutta. The Company ignored him. Thereupon the Nawab laid siege to the fort and took it after a bloody battle. His troops imprisoned about 120 British and Indian survivors – men, women and children – in a barrack which measured only about 4.5 by 5.5 metres, and left them there without food or water overnight. The air to breathe was limited among such a large number, the heat was atrocious, and when the prisoners were released the next morning it was found that only twenty-three were still alive. This was the famous Black Hole of Calcutta.

Apart from the need to nip this rebellion in the bud, for the British were indeed planning to use Bengal as a base for greater expansion in India, the affront demanded vengeance. Clive acted swiftly, moving north from Madras, and took Calcutta with relative ease on 2 January 1757. Siraj continued his fight, but the British forces had superior discipline and weaponry, and he was defeated finally at the Battle of Plassey towards the end of June. Titular control of Bengal passed to Siraj’s former commander-in-chief, who was already in Clive’s pocket. The hegemony of the East India Company was assured, and, incidentally, once Bengal was surely in its grasp, the Company took over the lucrative opium trade, formerly the preserve of the Dutch, and exported the drug to China.

APART FROM THE NEED TO NIP THIS REBELLION IN THE BUD, THE AFFRONT OF THE BLACK HOLE OF CALCUTTA DEMANDED VENGEANCE.

Siraj was not the only Indian ruler to try to assert his independence against the British. Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore (1750–99), was the eldest son of Haider Ali. He succeeded his father as ruler of Mysore in 1782. Tipu was a cultivated man, a poet and a linguist, as well as an able soldier. He is one of the heroes of Indian independence. An early opponent of the British, and quick to see the danger of giving them too much rope, he fought alongside his father, then an ally of the French, and defeated the British in the Mysore War of 1780–4. He continued to resist the British for the rest of his reign, and died bravely, defending his capital, Seringapatam, when Mysore’s resistance came to an end.

The most famous relic of his reign is his Tiger-Organ, a life-sized model of a Bengal tiger mauling a prostrate British redcoat. The organ is fitted with a number of pipes, and when operated, the tiger roared and growled and the soldier cried and groaned. After Tipu’s fall, it was seized and sent for display to the East India Company Museum in London, where it created a great stir. Keats even alluded to it (rather foolishly) in his ‘Cap and Bells’. It can now be seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, but it is no longer played.

During its ascendancy, from the time of Clive’s victories in the mid-eighteenth century to its demise in the wake of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the British East India Company, or ‘John Company’ as it was nicknamed, through a policy of shrewd trade-offs with local rulers, and of playing them off against each other; through the placement of British ‘advisers’ in the various courts of the rajahs and maharajahs, and the development of a highly efficient private army, ran the subcontinent for the British with a minimum of fuss and a great deal of profit.

Another aspect is of interest. It was not until the nineteenth century that fraternizing with the local people began to be discouraged as a general rule. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, miscegenation was actively encouraged, and many a prominent ‘British’ officer was born as a result. James Skinner (1778–1841), the founder of ‘Skinner’s Horse’ cavalry regiment, had an English father, but a Rajput mother.

Such events, tragic as they are, and whatever the truth behind them, are the very last twitchings of a dead age. More serious are the possible repercussions. There has been talk in Kenya of following Zimbabwe’s lead in forcible repossession of farms owned by whites. Over all this falls the shadow of Empire.

In Britain, and much more positively, belonging as it were to a different age, perhaps the greatest recent flowering of ‘immigrant’ talent has been in the arts. Not only does Britain have established sculptors and painters of the calibre of Anish Kapoor (born in Bombay in 1954 but now living in England) and Chris Ofili (born in Manchester in 1968) as well as rising stars such as Raqib Shaw (born in 1974 in Calcutta, now living and working in London), but in the last decade or two she has been privileged to see a great wave of new novelists from the non-white ethnic minority community. Apart from established, eminent, even venerable writers such as R. K. Narayan, Anita Desai and Salman Rushdie and the Nobel prizewinners Sir V. S. Naipaul and Wole Soyinka, recent years have seen a flood of novels from the pens of such (predominantly female) writers as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Monica Ali, Kiran Desai, Andrea Levi, Zadie Smith and Arundhati Roy. Not all of these, of course, live in Britain, but their work has exercised profound influence here and enriched her cultural heritage immeasurably, as well as having been influenced to a greater or lesser degree but always irresistibly by the old Empire. And so the complicated, colourful story continues. But to understand the true roots of the Children of Empire, we must first look at the origins of that Empire itself, at the men and women who shaped it, and how it, in the course of three centuries, shaped them.

CHRIS BISSON TRINIDAD (#ulink_62d6780e-2ba6-570f-9671-abe1da71be09)

Chris Bisson is a familiar face on British television. He is probably best known for playing shopkeeper Vikram Desai for three years, when Coronation Street introduced its first South Asian family. He has also starred as Saleem Khan, the son of a Pakistani fish-and-chip shop owner in the 1999 film East is East, and as Kash, owner of the local mini-mart in the Channel 4 hit series Shameless.

Despite playing so many Asian roles, a lot of them as a shopkeeper or shopkeeper’s son, Chris doesn’t see himself as Asian. His paternal family’s roots are in India but over the last century the family’s history has been so changed by the British Empire that they have lost all connection with the subcontinent. Chris’s grandfather and father were born in Trinidad and he has grown up feeling British West Indian, not Indian. It’s a family history that made him question what it really means to be British in the twenty-first century.

Chris was born in Manchester in 1975. His mother, Sheila, who is white, grew up in a small family in Wythenshawe, a suburb of Manchester. Her relationship with Chris’s father, Mickey, was the first she had had with someone who was not white. Mickey’s lively household, with his nine brothers and sisters in Moss Side, was a culture shock. Sheila’s parents found their daughter’s relationship difficult initially but things changed when their grandson, Christopher, was born.

Chris wanted to find out how the British Empire has shaped his family’s history. His father, Mickey, arrived in Britain in 1965. Chris went to talk to his father about his memories of that time. Mickey recalls how cold it felt in Britain in August. He also remembers the affluent lifestyle that the family left behind and showed Chris photographs of the large house they had owned in Trinidad. Mickey wondered why his father left that life and the successful businesses he had built up. It was clear that Chris needed to go to Trinidad to find out more. He had never been to the island before.

Although Chris’s father was born in Trinidad he is ethnically Indian, like 40 per cent of the island’s population. Chris knew that the key to unlocking the family story was his great-grandfather, whom he knew simply as ‘Bap’. No one in the family had any idea of Bap’s full name and no pictures existed of him. All they knew was that he came to Trinidad from India. When Chris arrived in Trinidad, his first stop was to visit his second cousin, Rajiv, whom he had never met before. Bap was Rajiv’s grandfather so he is a generation closer than Chris. Rajiv was able to provide Chris with two vital pieces of information. The first was that Bap’s full name was Bishnia Singh and the second was that he came from Jaipur in Rajasthan. This was unusual for a labourer – firstly to come from Jaipur and secondly because he was a warrior cast.

IT IS ESTIMATED THAT 2.5 MILLION INDIAN PEASANTS LEFT THEIR VILLAGES AND WERE SHIPPED AROUND THE EMPIRE TO WORK AS CHEAP LABOUR.

Chris suspected that, like most of Trinidad’s original Indian population, Bishnia came to the island as an indentured labourer. In the early nineteenth century Trinidad’s economy thrived on its sugar, cotton and cocoa plantations, which were worked by African slaves. When slavery was abolished in the 1830s the British, who had ruled the island since 1797, needed a new source of cheap, plentiful labour. They began importing Indian peasants under the indentured labour scheme to replace the freed slaves, but refused people of a higher cast, which is why Bishnia’s situation is unusual.

In order to confirm his suspicion, Chris enlisted the help of Shamshu Deen, an historian and genealogist. To his astonishment, Shamshu traced Bishnia to a book in the Trinidadian National Archives containing a register of Indian immigrants to Trinidad between 1901 and 1906. Among the 10,000 names in the book, Shamshu found Bishnia’s. Bishnia’s ‘number’ was recorded as 121,347, revealing that he was among the last of the indentured labourers to come to the island. In total, 147,592 labourers made the journey between the start of the scheme in Trinidad in 1845 and its abolition in 1917. But Shamshu had uncovered even more information for Chris. Each immigrant was issued with an Emigration Pass, signed by the ‘Protector of Emigrants’ in India. Bishnia’s pass recorded that he was 5’ 4”, had a ‘scar on left shin’ and was only seventeen years old when he emigrated. He arrived in Trinidad in January 1905, after a three-month voyage with 620 others, on a purpose-built ship called the Rhine. Chris was amazed by the level of detail contained in the document, which included the village (Kownarwas) that Bishnia came from. The pass held another surprise and showed just how much his great-grandfather gave up when he went to Trinidad: it records the name of Bishnia’s wife, whom he left behind in India.

Chris’s next stop was Nelson Island, off the coast of Trinidad. Nelson Island was the disembarkation point and quarantine station for the new indentured labourers, who were kept there for ten days. Chris visited the barracks, originally built by slaves in 1802, which were created to house the Indians, like Chris’s grandfather. The barracks were the first solid structure to be erected on Trinidad or Tobago. He found it an eerie and unsettling place, now inhabited by vultures and adorned with graffiti saying ‘Fock da British’. Once they had been certified at the barracks as fit and well, the labourers would be sent from Nelson Island to work on one of Trinidad’s 300 plantations.

In total, it is estimated that 2.5 million Indian peasants left their villages and were shipped around the Empire under the scheme to work as cheap labour in places they had never even heard of, including Mauritius, British Guiana and East Africa as well as Trinidad. Half a million of these so-called ‘coolies’ were brought to work on the sugar, coffee and cocoa plantations of the Caribbean. Although these labourers were not slaves and had signed contracts of employment, many were illiterate and could not read these contracts. It was not uncommon for people to be tricked into becoming labourers. Chris met ninety-six-year-old Nazir Mohammed who was brought to Trinidad as a baby by his mother, an indentured labourer. She was tricked by Indian recruiters who told her they were taking her to find her missing husband but instead took her and her baby to the labour depot. Nazir then grew up on a Trinidad plantation as a child labourer. He described conditions on the estate where he spent twelve years as being akin to slavery. The workers were forced to work and were whipped by the foreman.