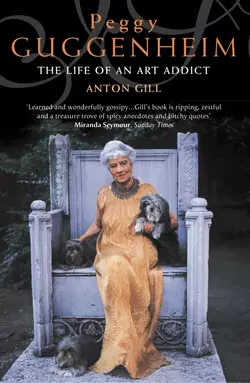

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

Anton Gill

This edition does not include illustrations.Please note that due to the level of detail, the family tree is best viewed on a tablet.The wayward life (1898–1979) of the voracious art collector and great female patron of world-famous artists.‘Mrs Guggenheim, how many husbands have you had?’ ‘Do you mean my own, or other people’s?’ Peggy Guggenheim was an American millionairess art collector and legendary lover, whose father died on the Titanic returning from installing the lift machinery in the Eiffel Tower. She lived in Paris in the 1930s and got to know all the major artists – especially the Surrealists. (Later she bullied Max Ernst into marrying her, but was snubbed by Picasso.) When the Second World War broke out, she bought great numbers of paintings from artists fleeing to America; as a Jew she escaped from Vichy France and set up in New York, where in the 1940s and 50s she befriended and encouraged the New York School (Jackson Pollock, Rothko, etc.)Her emotional life was in constant turmoil – a life of booze, bed and bohemia (mostly rich bohemia). Her favourite husband was a drunken English dilettante writer called Lawrence Vail, but she bedded many others, including Samuel Beckett. Later she moved to Venice, where her memory is enshrined in the world-famous palazzo that houses her Guggenheim Collection.

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM

The Life of an Art Addict

ANTON GILL

To Marji Campi (who started all this)

with admiration, gratitude and love

London, New York, Paris, Venice; 1997–2001

Contents

Cover (#u3e11d194-9c99-5fd8-bc72-44f37ba99faf)

Title Page (#ub515e4dc-1e8a-58e3-acac-f4117b1bc474)

Dedication (#uc7c74410-f6c0-54c8-b383-9006c017fbe6)

Family Tree (#ueb1aec1f-06de-5c7a-99ad-029c02ed865d)

Foreword (#uaa232d12-834c-5f01-bacb-9dfdf634fe2b)

Prelude (#u752f7737-918e-5b5f-8a52-c2006439cc3e)

Part 1: Youth (#u8ca5462b-b7b9-5b65-812c-82222a3d5d1a)

1: Shipwreck (#ud9bb917f-2d57-527e-bb89-f36c03265313)

2: Heiress (#uc182918a-16d8-519f-8957-d15ba56c3513)

3: Guggenheims and Seligmans (#u1064a6f4-2ace-55f1-b967-085af4c22771)

4: Growing Up (#u640719e3-96ef-51a7-af14-e54f09198988)

5: Harold and Lucile (#uab17e0f1-6e81-57fd-8af7-e811b0ba6b48)

6: Departure (#u76d847b3-dd4a-573a-84c2-2a0844be845b)

Part 2: Europe (#u1a1852bd-d9a1-53dd-b22f-5e77c3a6ee8f)

7: Paris (#u4be2530c-c842-51a3-9afe-85f93bd67933)

8: Laurence, Motherhood and ‘Bohemia’ (#ub1bb5e61-ff82-58b5-a848-75688e75be1a)

9: Pramousquier (#ua76be2bf-5555-5e04-82a2-ce25635ca5f5)

10: Love and Literature (#litres_trial_promo)

11: Hayford (#litres_trial_promo)

12: Love and Death (#litres_trial_promo)

13: An English Country Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

14: Turning Point (#litres_trial_promo)

15: ‘Guggenheim Jeune’ (#litres_trial_promo)

16: Paris Again (#litres_trial_promo)

Intermezzo: Max and Another Departure: Marseilles and Lisbon (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3: Back in the USA (#litres_trial_promo)

17: Coming Home (#litres_trial_promo)

18: Art of This Century (#litres_trial_promo)

19: Memoir (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 4: Venice (#litres_trial_promo)

20: Transition (#litres_trial_promo)

21: Palazzo (#litres_trial_promo)

22: Legacy (#litres_trial_promo)

23: ‘The last red leaf is whirl’d away …’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Coda (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Source Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Family Tree (#ulink_5853520f-c0ac-5859-bff0-52bb08f11d28)

Foreword (#ulink_75805df1-f725-5a72-aca7-b61ded9c96a4)

This book is made up of material derived from private and public archives and collections, published works, unpublished works, letters, diaries, interviews, gossip, e-mails, telephone conversations, videotapes, faxes, websites and so on. Despite the fact that the subject is recent, a number of discrepancies of spelling have cropped up in proper names. Where that has happened, I have used the version most commonly used by others.

I have not tampered with usage, grammar or spelling in direct quotations from original material such as letters, though I have tidied up typographical errors – for many years Peggy Guggenheim used an ancient typewriter with a faded blue ribbon, and her typing was not accurate. I have left eccentricities of spelling alone (Peggy habitually spelt ‘thought’ ‘thot’, and ‘bought’ ‘bot’), and have provided an explanation only if the level of obscurity seemed great enough to warrant one. Round brackets in quoted passages belong to the passage; glosses within such passages are in square brackets.

Titles of artworks in Peggy’s collection are generally the same as those used by Angelica Z. Rudenstine in her catalogue of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Other paintings and sculptures are given the names they’re most commonly known by.

I’d like to express my thanks here at the outset to all who helped. A lot of people had a profound personal contact with Peggy, and shared their memories of her with me generously. I am most grateful to them – their names are in the acknowledgements at the end of the book. I have had to be selective in the use of some tangential detail for reasons of both focus and of space. Readers interested in further exploration of the background to this book are referred to the bibliography. Inevitably what I have written will lead to a certain amount of disagreement. Some of the material conflicted, and some was clogged with gossip and rumour. I can only say that to the best of my ability I have checked all the matter I have used for correctness, and that I have tried to keep speculation to a minimum. I thank Marji Campi, Barbara Shukman and Karole Vail for looking over the manuscript, but I alone am accountable for any errors. I have not, however, consciously sought to mislead or offend anyone in this record of the life of a complex, anarchic, remarkable woman.

Anton Gill

London, 2001

Prelude (#ulink_fdfbdf6d-7090-506a-9ec1-92192b5f91d1)

A Party

‘Her obduracy in contention and her warmth in friendship, her generosity and her stinginess, her plunges into gloom and wholehearted abandonment to laughter, her puritan streak and her reckless addiction to the erotic were all contradictions of the essence of her personality.’

MAURICE CARDIFF, Friends Abroad

The rain, which had not stopped for a week, ceased in the late afternoon of 29 September 1998, so that by the evening the flagstones in the garden were dry. The heat and the humidity relented too, so that as the crowd gathered the atmosphere and the temperature were perfect.

The garden was that of the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an eighteenth-century pile in Dorsoduro, on the Accademia bank of the Grand Canal in Venice, between the Accademia Bridge and Santa Maria della Salute, close to where the Canal Grande debouches into the Canale di San Marco. The palazzo is exotic. It was never finished. It only has a sub-basement and one storey, with a flat roof that doubles as a terrace; but the garden is one of the largest in Venice. The trees are huge. When Peggy Guggenheim owned and lived in the palace, the garden was muddy and overgrown, and the sculptures planted in it – the bronze trolls of Max Ernst, the minimalist, organic forms of Arp and Brancusi – inhabited it as mysterious beings might lurk in a wood, waiting for the traveller to come upon them unaware.

Several hundred guests were gathering that Tuesday evening twenty years after her death in a more manicured space: neatly flagged and gravelled, with the sculptures openly displayed. Not all of the sculptures now belong to the art collection which Peggy Guggenheim brought here in the late 1940s. Many are part of the collection of the Texan collectors Patsy and Raymond Nasher.

The crowd has assembled in the electrically lit, mosquito-free night. The garden is full. Dress ranges from super-elegant to T-shirt and jeans, but everyone is stylish. Le tout Venise is here to mark the opening of an exhibition commemorating the centenary of Peggy’s birth. Organised by one of her granddaughters, the exhibition has come here from New York, where it opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Solomon was Peggy’s uncle, though their two art collections were separate entities during most of her lifetime. The granddaughter, Karole Vail, is the only Guggenheim grandchild to work for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She is among the guests, in a Fortuny dress, elegantly echoing the Fortuny dress Peggy often wore. Her sister Julia and her cousins are there too – six of the seven surviving grandchildren. Mark has not come. Fabrice died in 1990.

Philip Rylands is the curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. He has been in charge since the palazzo became a public gallery in 1980. Philip is English, and originally came to Venice from Cambridge University to research a doctoral thesis on Jacopo Palma (il Vecchio). He makes a speech in impeccable Italian. During it, as the light through the trees throws changing shadows on the people below, Mia, Julia’s daughter, the only one of Peggy’s great-grandchildren present, twenty-one months old, clambers onto Untitled (1969) by Robert Morris – a huge rectangle of steel balanced on a massive section of steel dowelling, stretched horizontally on the ground. Mia runs up and down. Her activity turns a few heads.

After two hours, people have begun to filter away, and in another hour the garden will be empty. In a corner a stone slab set into a wall marks the resting places of Peggy’s ‘beloved babies’ – fourteen little dogs, until almost the end all pure-bred Lhasa Apsos, which in a series of generations shared Peggy’s life in the palace. Next to it is another plaque. On it is written: ‘Here rests Peggy Guggenheim 1898–1979’.

The party in 1998 filled the garden. Eighteen years earlier, on 4 April 1980, only four people were present for the interment of Peggy’s ashes. She had died an isolated death just before Christmas the previous year.

Although Peggy’s claim to fame is as one of the foremost collectors of modern art of the first half of the twentieth century, her ‘offstage’ life as a restless combination of wanderer and libertine has attracted so much gossip, obloquy, scandal and delight that it has overshadowed her influence as a patron of painters and sculptors. When she was at the peak of her career, feminism was in its infancy and, apart from the Suffragette movement, not organised on any major scale. Men took it for granted that they had precedence over women, and it would be hard to find a more sexist bunch than the male artists who flourished between 1900 and 1960. Peggy took on their world with a mixture of low self-esteem and aggression, aided by money. She couldn’t enter that world as an artist – a difficult task for any woman at the time – but she could use her money to buy a position in it. In her endeavours she never quite found herself, but she supported three of the most important art movements of the last hundred years: Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract-Expressionism.

It took Peggy some time to come to modern art. She was twenty before she held a contemporary painting in her hands, at the photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s boundary-breaking 291 Gallery in New York City – a picture by Stieglitz’s wife-to-be, Georgia O’Keeffe. If she was flirting with Bohemia as early as that – the introduction to Stieglitz stemmed from work in a cousin’s avant-garde bookshop – it would be another twenty years, one husband and many lovers later before she started work on her own account.

At twenty-one, Peggy came into the first slice of what was a relatively slender fortune. In the years following the First World War, Europe beckoned young Americans, and Peggy, used to childhood holidays on the Continent, and for other reasons too, was among the first to go. There she plunged into the world to which she was to belong for the rest of her life, and in which she was to be a star.

The Second World War forced her, as a Jew, to retreat to America. There, in New York, she created a gallery the like of which had not been seen anywhere before, and through it and the salons – if such a word can be applied to the whiskey-and-potato-chips parties she held – in her house overlooking the East River on East 51st Street, she created a forum where young American artists could meet and confront the old guard of European modern art in exile.

The war over, and another marriage unhappily over too, she returned to Europe, and made her home in Venice. It was there that she set about the task of consolidating her collection. She’d been a flapper, she’d been a profligate, she’d been a Maecenas, she’d been a wife, she hadn’t been much of a mother. Now it was time to become a grande dame. Inside, there had always been an inquisitive and lively girl who had never been able to find love.

When I first visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection I was struck by the refreshing contrast to the splendours of Renaissance and Baroque art in which Venice is so rich. It was a palate-cleanser after which one could return happily to the glories of the Scuola San Rocco or the Frari. Peggy herself, hesitating to name any picture in her own collection as her favourite, did have a favourite painting: The Storm by Giorgione (c.1505), in the Accademia, a stone’s throw from her palazzo. She once said she would swap all of her collection for it.

The festa to mark her one hundredth birthday would have amused Peggy by its contrast to her lonely departure from this world, and it would have touched her that so many people were there. She would also have been appalled at the expense.

Later that evening it began to rain again.

1 Youth (#ulink_c29d886d-70b6-5844-a8a0-4aa885f66cf2)

‘I was born in New York City on West Sixty-Ninth Street. I don’t remember anything about this. My mother told me that while the nurse was filling her hot water bottle, I rushed into the world with my usual speed and screamed like a cat.’

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM, Out of This Century (1979)

CHAPTER 1 Shipwreck (#ulink_0b279a01-7885-53d8-82c1-196d167ac462)

Things had been going badly for Benjamin Guggenheim for a long time. The fact that his marriage was falling apart was something he’d got used to a while back, and, as he admitted to himself, there had been ample consolation – though through it all a nagging lack of satisfaction – for the rapid cooling of his relationship with his wife. The business was another matter. He’d left the family firm eleven years earlier, in 1901, full of injured dignity at what he saw as the high-handed attitude of most of his brothers, determined to go it alone and show them: after all, the expertise he’d picked up in mining and engineering should have stood him in good stead. And, to be fair, it had. Wasn’t his International Steam Pump Company responsible for the lifts that now ran all the way to the top of the Eiffel Tower? And Paris hadn’t been a bad alternative, this past decade, to a loveless, even inimical, New York. If it weren’t for his daughters, Benita, Peggy and Hazel, the three unlikely products of his and Florette’s rare moments of passion (informed by duty) over the first eight years of their union, he might well have cut loose altogether.

But the business was going downhill, and he could see no way of turning it round. He’d never been a businessman, any more than he’d been an enthusiastic student – though the family never failed to remind him that he was the first of the first-generation American Guggenheims to go to university. The failure of his business was worse than the failure of his marriage. Excluded from the family concern, how could he ignore the vast strides that it had made since he’d left at the turn of the century, drawing a modest $250,000 a year from his then-existing interests? Now, in April 1912, he’d decided to return to the States. It would be Hazel’s ninth birthday on the thirtieth. He’d be home for that. And he might drum up some extra capital once home, too, though asking his brothers for a loan would be a long shot, and his wife’s money was too tied up for him to reach, even if he’d had the courage to ask for it. At least no one in the family but himself knew how bad things were. Mismanaged capital, shaky investments and an extravagant lifestyle were to blame.

He’d married Florette on 24 October 1894. She was twenty-four, he was twenty-nine. He’d played the field beforehand, and he was handsome enough to have attracted a better-looking partner; but she was a Seligman, and therefore, though her family looked down on his, a real catch. The Seligmans didn’t have the kind of money the Guggenheims had, but they had the New York cachet the Guggenheims needed, and at that time Ben was still a paid-up member of the family.

Since the birth of his youngest daughter, Ben had spent more and more time in France, looking after his business interests and several mistresses. He’d hardly seen his children in the past year, and not at all in the last eight months, though a letter survives from him to Hazel, written from Paris in early April 1911, which testifies to the affection he had for them. It also indicates that he wanted to see his wife again, though its tone is more dutiful than sincere:

Have just received your letter, am sorry it takes so long for the doll to get through the custom house but when he does reach you I am sure you will like him. We had quite a lot of snow and cold weather yesterday so you see that even in Paris we sometimes are disappointed. However it is again pleasant today and I think we will soon see the leaves on the trees. Tell Peggy I have just rec’d her letter of the 30th Mch but as I just wrote her yesterday I shall not write again today. Tell her also I was very glad to receive this her [?]kind letter and hope that she and you will frequently find time to write me. I am writing Mummie asking if she wants me to rent a beautiful country place at Saint Cloud near Paris. If we take it she can invite Lucille and [?]Doby, and can remove there for July.

With much love from your

Papa

He missed his children, especially the younger two, who adored him and were rivals for his affections. His oldest, Benita, named for him, was almost seventeen – already a young woman, self-possessed, a little cool, beautiful, unlike her mother, but showing signs of wanting nothing more than the moneyed, inactive life of bridge, tea-parties and gossip that Florette enjoyed. Ben was well aware that Florette regarded him as a loser. She had her own means, but she liked money, and she liked acquiring it more than spending it.

What a pity they hadn’t produced a son. But that was something the Guggenheim clan was seldom capable of.

The closest Ben had to a son was his nephew Harry, one of the five boys the seven brothers had managed to produce to carry the family name forward – though Ben’s sisters also had sons. Ben had had lunch with Harry in Paris on 9 April, shortly before leaving for Cherbourg to pick up his ship for the States. Harry was a shade strait-laced already at twenty-two, but Ben talked to him about his business affairs, playing down his difficulties; Harry’s father was Daniel, the most dominant, though by no means the richest, of Ben’s brothers. Ben steered clear of personal observations. A few years earlier, when Harry was fourteen or fifteen, Ben had got into hot water by offering him this piece of advice: ‘Never make love to a woman before breakfast for two reasons. One, it’s wearing. Two, in the course of the day you may meet somebody you like better.’

Shortly before the meeting with Harry, Ben had a problem to deal with. The ship he was booked on, with his chauffeur, René Pernot, and his secretary-valet, Victor Giglio, was suddenly unable to sail, owing to an unofficial strike over pay by her stokers. Ben was one of a number of irritated passengers who were forced to find alternative berths, but after a number of wires to London, New York and Southampton, luck appeared to favour him. He managed to get two first-class cabins, for his valet and himself, and a second-class berth for his chauffeur, on the White Star Line’s new flagship, RMS Titanic, which was making her maiden voyage, stopping at Cherbourg on the evening of 10 April, en route from Southampton to New York via the French port, and Queenstown (now Cóbh) in Ireland. It wasn’t cheap – the first-class cabins cost $1520 each one-way – but the ship was very fast, at the cutting edge of technology and, in first class at least, the last word in elegance. Ben, used to the good things in life even in adversity, was pleased that the switch had had to be made. And when he looked at the passenger list and saw in what august company he’d be travelling, he wondered whether the manner of his crossing the Atlantic might send a message to his brothers that he was doing better than he actually was.

Ben was the fifth of seven brothers. Only William, the youngest, might have been sympathetic, but William had cut loose from the family firm at the same time as Ben, and while he shared Ben’s love of the good life, he was a self-absorbed young man. Like Ben, he had become a ‘poor’ Guggenheim. Each of the two brothers had given up a capital interest of $8 million when they’d left the business – something else Ben had kept secret from his wife.

Nevertheless, as he settled into his cabin on B deck, Ben could reflect that ‘poor’ was a relative term. He still had plenty of money by most people’s standards, and his older brothers, as far as he could see, had yet to make serious money themselves. In his forty-seventh year, Ben still had time to turn his fortunes round.

But it was not to be. We don’t know where Ben was at 11.40 p.m. on the night of 14 April, but the chances are that he had already retired to his cabin. Wherever he was, he would have felt the faint, grinding jar that came from the bowels of the ship at that moment. He may well have seen the iceberg as it glided past. But like most on board, he did not feel any concern. After all, the Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable. Relying on this, and ignoring ice warnings which had come from other ships in the area throughout the day, the captain, Edward J. Smith, a veteran sailor making his last voyage before retirement, had continued to sail virtually at full speed. Egged on by J. Bruce Ismay, White Star’s president, he was attempting to set a new transatlantic record.

At about midnight, by then joined by Giglio, Guggenheim was being helped into a lifejacket by the steward in charge of that set of eight or nine cabins. Henry Samuel Etches urged Guggenheim against the latter’s protests to pull a heavy sweater over the lifejacket (few aboard, cocooned from the elements in the well-heated, brilliantly-lit liner, had any idea of how cold the North Atlantic was), and sent him and his valet on deck. As first-class passengers, their places in lifeboats were assured. However, in the next hour or so, as confusion mounted and it became clear that women and children might be left aboard the sinking ship as the inadequate (and in the event woefully underfilled) lifeboats began to be cast off, Benjamin Guggenheim and Victor Giglio did a stylish and brave thing: they returned to their cabins, changed into evening dress, and then set about helping women and children into the boats. Ben is reported to have said, ‘We’ve dressed in our best, and are prepared to go down like gentlemen.’

The rest of the story may belong to the corpus of Titanic myth, but it’s reasonable to believe some of the details of Ben’s last moments. However, as neither Giglio nor the chauffeur, René Pernot, survived either, it is impossible to verify them. The first-class cabin steward, Etches, was ordered to take an oar in a lifeboat, and did survive. He subsequently made his way to the St Regis Hotel in New York, where several members of the Guggenheim family had apartments, and asked to see Ben’s wife, as he had been entrusted with a message from her husband. Florette, who already knew that Ben was missing, was too grief-stricken to see him; he was received by Daniel Guggenheim. The encounter was widely reported, but the fullest account of Etches’ story appeared in the New York Times on 20 April:

… I could see what they [Ben and Giglio] were doing. They were going from one lifeboat to another, helping the women and children. Mr Guggenheim would shout out, ‘Women first’, and he was of great assistance to the officers.

Things weren’t so bad at first, but when I saw Mr Guggenheim and his secretary three-quarters of an hour after the crash there was great excitement. What surprised me was that both Mr Guggenheim and his secretary were dressed in their evening clothes. They had deliberately taken off their sweaters, and as nearly as I can tell there were no lifebelts at all.

It is possible that Etches concocted a tale of heroism with an eye to a reward of some kind from the wealthy family; but in view of the fact that Ben and his valet were not the only men who went down with the ship rather than take what could have been seen as the cowardly expedient of getting into lifeboats, it seems unlikely. Other newspapers reported that among the prominent people on board, John Jacob Astor IV, of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, President Taft’s military aide, Major Archibald Butt, and Isidore Straus of Macy’s department store also helped others into the boats and thus sacrificed their own lives. Etches added that Ben had told him, ‘If anything should happen to me, tell my wife in New York that I’ve done my best in doing my duty,’ and that ‘No woman shall go to the bottom because I was a coward.’ Significantly, Bruce Ismay, who did save himself, was profoundly affected from the moment he was taken aboard the rescue ship, Carpathia. As the chronicler of the disaster, Walter Lord, records in his book A Night to Remember: ‘During the rest of the trip Ismay never left [his] room; he never ate anything solid; he never received a visitor … he was kept to the end under the influence of opiates. It was the start of a self-imposed exile from active life. Within a year he retired from the White Star Line, purchased a large estate on the west coast of Ireland, and remained a virtual recluse until he died in 1937.’

Ben’s family was devastated by his loss. Strangely, eight hours before the Titanic struck the iceberg, Florette and her three daughters were returning home from the eighty-ninth birthday party given for Florette’s father, James Seligman, when Benita’s attention was drawn to a newsvendor shouting, ‘Extra! Extra!’ By some clairvoyance, she urged her mother to buy a paper, insisting that ‘something terrible must have happened to Poppa’s boat’, as Hazel later recounted to a Guggenheim family chronicler, John H. Davis.

Though there is no reason to disbelieve Etches’ account, many apocryphal stories did grow up around the disaster. The newspapers had a field day, and this was not surprising. In the days before film, pop and sports celebrities figured largely in the public consciousness, it was the rich, the great and the good who filled these roles, and the Titanic had taken a fine crop of them to the bottom with her. There was another element too, which only became apparent months and even years later. The sinking of the unsinkable was a defeat of Humankind by Nature. Total and assured belief in technology foundered. The same year, Captain Robert Falcon Scott and his party died on their return journey from the South Pole: their bodies were discovered in November, another blow to the world’s confidence in itself. The First World War would soon decisively break down the old order.

In the rush to report the news of the sinking, various journalistic errors occurred. On 20 April the Daily Graphic brought out a commemorative edition focusing on the disaster, in which a photograph of Ben’s younger brother Simon appeared over the caption, ‘Benjamin Guggenheim’ – a further source of distress to the family. Etches is referred to as ‘James Johnson’ – another steward – in several accounts, and, most wildly of all, it was claimed that Ben had left a fortune of $92 million, ‘mostly to his family’. As his family had no idea of how much he was actually worth, this news aroused mixed feelings; but any optimistic reaction must have been tempered by the fact that Ben had only carried a life insurance policy of $23,000. Not a bad sum in itself – as a comparative guide, the prominent British journalist and sex-reformer William T. Stead, who also drowned in the disaster, was insured for $10,000; but the highest level of insurance of those on board was $50,000.

There were other myths. Throughout her life Hazel, who lost her father a few days short of her ninth birthday, was profoundly affected by the experience. At her own funeral in 1995, she had arranged for ‘Nearer, my God, to Thee’ to be played – but despite popular belief, the hymn was never played as the great ship died. The ship’s band bravely played on until the end – and not a single musician survived – but what they played was ragtime. Another myth which affected the Guggenheims was the story of a ‘Mrs Guggenheim’ being on board with her ‘husband’, a story which quickly inflated to produce a ‘blond singer’, a mistress of Ben’s whom he’d brought aboard at Cherbourg. No such person appears on the Titanic’s passenger list, and it is highly unlikely that even the womanising Ben would return home for his youngest daughter’s birthday, expecting to be met at the New York quayside by his family, with a woman in tow. (It is possible, though unlikely, that he picked someone up on board.)

For a time, Florette continued to cling to the hope that her husband was not dead, but simply missing – the first survivor lists issued were confusing, and the Carpathia aroused press anger by refusing to wire ahead a definitive schedule of whom she had picked up. This was not mischievous or malicious: Captain Rostron was giving wireless priority to ship’s business and survivors’ messages to their families. However, the Carpathia was a slow ship, and she didn’t reach New York until the Thursday following the Sunday night which had seen the Titanic sink.

There is no record of Benita’s reaction to the loss of her father, but Hazel and Peggy left behind their own testimonies. Hazel, who became a painter, was almost always concerned with ships and water in her pictures, and as late as 1969, on the anniversary of the sinking, she produced a five-stanza poem, ‘Titanic Lifeboat Blues’. A year later she had it set to music and recorded it, singing the words herself. The first stanza will suffice to give an impression. Despite its shortcomings, there’s no doubting its sincerity:

Half four score and seventeen years agoMy father stood on deck, declined towards safety to row.Gave his place in lifeboat to the weaker sex.That ship that sank midst wreck of trunk and bunk,Titanic was her name; Titanic was her shame!All this to win Atlantic speeding fame,That ocean sport; near coast of HalifaxHad nearby ship been lax?Who knows, not even writer Walter Lord.Perhaps He knows – Almighty God our LordCan tell what caused death’s knell.

Peggy, approaching fourteen at the time of her father’s death, is more succinct in her autobiography, written in the mid-1940s: ‘My father’s death affected me greatly. It took me months to get over the terrible nightmare of the Titanic, and years to get over the loss of my father. In a sense I have never really recovered, as I suppose I have been searching for a father ever since.’ It is hard to determine how far either woman in later life was being disingenuous. Each may have needed an excuse for the wildness in their lives. However, neither was particularly introspective.

Amidst all the press speculation, Florette and her daughters were to discover the true extent of Ben’s fortune. But it would be a long process.

CHAPTER 2 Heiress (#ulink_27eff1ba-ae1d-58c5-8609-6da1be2f6bf7)

After Ben’s death his powerful brothers, Daniel, Murry, Solomon and Simon, put aside the differences they’d had with him during his life, and pulled together to help his widow and her family. Ben’s International Steam Pump Company, together with a variety of lesser business interests, not to mention his lavish personal tastes, the maintenance of his staff, his mistresses, and a Paris apartment, had absorbed almost all his capital.

As a temporary measure, without her knowledge, the brothers discreetly advanced money from their own pockets to Florette via a private account, and set about the business of unravelling Ben’s affairs. It took seven years to sort everything out and pay off the many creditors. By the time this had been done, all that remained was about $800,000 for Florette and $450,000 for each of the girls. The brothers estimated that Ben had run through about $8 million.

Although the inheritances were no mean sums, they were small compared with the wealth of the Guggenheim empire, and they dictated a change in Ben’s family’s way of living. Florette was proud, and when she discovered that the income she’d been receiving had come from her brothers-in-law, ‘she nearly had a fit’, according to Peggy. (When Florette’s father died in 1916, leaving her $2 million, her circumstances improved considerably, and she was able to repay the loan.) Since Ben had more or less permanently absented himself in 1911, the family had moved into a residential suite at the St Regis Hotel – a Guggenheim stronghold – and the house on East 72nd Street had been let to an aunt of Peggy. Now, in 1912, the St Regis became too expensive, and Florette moved with her daughters to a more modest place on the corner of 5th Avenue and 58th Street – though it did have a 5th Avenue number. Evidently the Seligman family couldn’t or wouldn’t help, and Florette reluctantly started to live on her own money. It is possible that her blood relatives thought she had quite enough to survive on, or perhaps, as she had married into the Guggenheims, it was felt that her maintenance was their responsibility. Either way, no one was going to starve.

But it was a blow to find out just how little Ben had left them with. Hazel Guggenheim told a friend, somewhat melodramatically, that ‘my mother made eggs by the hot water from the faucet’. Servants had to be dismissed, and paintings, tapestries and jewellery sold. Hazel remembered that her father bought paintings by Corot, and ‘owned gorgeous suits and shoes and ties, and wore slippers of Moroccan leather’, and that ‘my mother and he went to the opera every night’. That way of life was gone, and Peggy wrote, ‘from that time on I had a complex about no longer being a real Guggenheim. I felt like a poor relative and suffered great humiliation thinking how inferior I was to the rest of the family.’

The context in which she felt this is best understood by making comparisons. The oldest Guggenheim brother was Isaac. When he died in 1922 he left $10 million. Murry died in 1939 leaving $16 million; Dan in 1930 leaving $6 million. Although Peggy and Hazel were to inherit a further $500,000 apiece from their mother on her death in 1937 – their beloved older sister Benita having died ten years earlier – they still saw their cousins, Murry’s children Edmond and Lucille, coming into $8 million each, and Dan’s children Robert, Harry and Gladys getting about $2 million apiece. Everybody lived in close proximity in New York City and on Long Island, and it isn’t surprising that Peggy, at least, wanted to get away – with Hazel following suit. Benita, at seventeen significantly older at the time of Ben’s death, and gentler and more conventional than her sisters, would follow a different path.

‘After his death,’ Hazel recalled much later to Virginia Dortch, who compiled a portrait of Peggy through the reminiscences of her friends, ‘in order not to offend the Guggenheims, my mother would never marry or even sit alone in a room with a man. I suppose, if father had lived, Peggy would have married bourgeois men and I would have stayed married to them.’ However, this may be disingenuous, and does not take into account Florette’s own eccentricity, however mild it was by comparison with her own brothers’ and sisters’. In any case it isn’t helpful to speculate on what might have been. Peggy and Hazel were rivals for their father’s love and for Benita’s love; later they were rivals for fame and notoriety. For the moment, they turned to religion. ‘After my father’s death I became religious,’ wrote Peggy. ‘I attended the services in Temple Emanu-El regularly, and took great dramatic pleasure in standing up for the Kaddish (the service for the dead).’ The family went into mourning, and Peggy felt ‘important and self-conscious in black’.

Ben’s death as a hero when they were both young girls, and the mythic element lent his death by the fact that his body was never recovered, led Peggy and Hazel to idolise his memory more than they might otherwise have done; but it is doubtful whether his death fundamentally affected the course their lives were to take. More important was the comparative lack of money. The youngest of the Guggenheim brothers, William, sued his older siblings in 1916 over what he considered his illegal exclusion from profits from ventures which had flourished since his departure, specifically a fabulously profitable foray into copper mining in Chile. Unfortunately, he and Ben had signed a disclaimer to participation in the mining ventures of the family firm in January 1912. Florette, loyal to the Guggenheims because of their kindness to her, would have nothing to do with William’s case. The other Guggenheim brothers settled out of court for $6 million, which William, with a reputation for poor investments which led Wall Street to nickname him ‘Willie the Plunger’, and a taste for starlets and beauty queens, big cars, a large staff and a big house, as well as a flirtation with vanity publishing, managed to reduce over the next twenty-five years to virtually nothing. After his estranged wife and her son by him had successfully claimed their rightful shares under New York State law, and after debts and taxes had been deducted, all that the two chorus-liners and two beauty queens who had hoped to be William’s principal heirs at his death in 1941 received was about $1000 apiece. Fortunately for William’s descendants, Simon Guggenheim, knowing his younger brother’s ways, had set up a $1 million trust for his heirs after the lawsuit.

Ben and William had been born and brought up under a less onerous burden than their brothers, to the latters’ resentment; but with hindsight they had cause to be grateful for their father’s severity. Ben and William were the ones singled out for university education before joining the family firm. William, for all his failings, had a sensitive and intellectual streak, and a sense of history which prompted him to write an eccentric but nevertheless important memoir of himself and, more importantly, the early days of the Guggenheim empire. And although Solomon Guggenheim was to demonstrate that an artistic sensibility existed within the family, it was Ben who was the principal inspiration for his middle daughter’s decision to live in artistic circles, and for her love of Europe.

Above all, despite all attempts at assimilation, Peggy was marked by her Jewishness. She belonged to a family within the Jewish New York community which was still regarded as arriviste despite its great wealth, and she was a member of the poorest branch of that family. She experienced anti-Semitism early on, and understood the refugee society’s eternal need to stick together and find security in money – Peggy was only second-generation American. Both her grandfathers had come from the middle-European Jewish peasantry and had started out in America as peddlers. From them she inherited two basic characteristics of the successful trader: a love of money and a disinclination to part with it without good reason. If she didn’t set out to make money, in the end what she invested in pictures repaid itself a thousandfold. In leaving Peggy without the fortune her cousins enjoyed, Ben, ironically, did her a favour.

CHAPTER 3 Guggenheims and Seligmans (#ulink_e7f29584-99a3-5cbc-8b2d-adf746fb22fc)

Both Peggy’s grandfathers left Europe – Meyer Guggenheim in 1847, James Seligman in 1838 – to escape the financial and professional restrictions placed on Jews in the Old World. The Jewish communities of Europe were centuries old, but since the Crusades Jews had found themselves increasingly the object of mistrust, suspicion and fear. The communities defensively kept to themselves and did not integrate, but the countries in which they lived regarded them as at best unwelcome guests, and promulgated laws which ensured that life for them was as difficult and uncomfortable as possible. The majority of them lived in small rural settlements in eastern Europe and Russia, and were not allowed to farm or own land other than their own homes; even such ownership was subject to tariffs and taxes Christians were exempt from. Jews were not allowed to engage in mining, or the smelting of metal, or any other major industrial enterprise, or to practise in any of the professions outside their faith. The only jobs that remained open to them were tailoring, peddling, small-time retail in commodities, and moneylending. The Church permitted them to deal in moneylending because it considered Jews exempt from two tenets, ironically enough from the Old Testament: Exodus 22, verse 25: ‘If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer, neither shalt thou lay upon him usury’; and Deuteronomy 23, verse 19: ‘Thou shalt not lend upon usury to thy brother; usury of money, usury of victuals, usury of any thing that is lent upon usury.’ Pragmatically, the Church acknowledged the necessity for moneylending, but also saw that it was unpopular, and so, with political acumen, accorded the right to practise it to the Jews.

The origin of the Guggenheim family is uncertain, but it is possible that they originally came from what is now called Jügesheim, to the south-east of Frankfurt-am-Main. By the end of the seventeenth century the Guggenheims had moved to Switzerland from Germany, where the treatment of the Jews was harsher. In Switzerland the Jewish community enjoyed a monopoly on moneylending; but as commerce grew and money increasingly began to be used as capital for ventures, the advantages of lending it on interest began to be seen as sound business practice, and the Church’s prohibition on Christian usury was relaxed at the Fifth Lateran Council of 1512–18. The principal function of Jews in Switzerland thus became superfluous, and, with a growing Christian population, the cantons began to expel them. By the end of the eighteenth century the Jewish population of the entire country was reduced to two small communities, in Ober Endingen and Lengnau.

It was in Lengnau, a small village about twenty-five miles north-west of Zürich, that the Guggenheims settled. The earliest of Peggy’s ancestors on her father’s side whom we can trace for certain was a man called Jakob. Jakob Guggenheim was an elder of the synagogue and a respected local scholar of the Talmud, whose acquaintance was sought by a relatively enlightened Protestant Zürich pastor called Johann Ulrich, who had taken his arthritic wife to the nearby spa town of Baden in about 1740. As a result of their meeting Ulrich, already interested in Judaism, became a friend, but unfortunately the pastor’s proselytising zeal led him to persuade one of Jakob’s sons, Josef, to convert to Christianity. The procedure took sixteen tormented years as the sensitive and intellectual Josef struggled with his conscience. It broke up the friendship; but the Guggenheims had had their first brush with the politically dominant religion. Jakob’s protest at his son’s conversion was so angry that he incurred the wrath of the Christian community, which obliged him to pay a massive six-hundred-florin fine in order to remain in Lengnau. That he could afford it shows how prosperous the family was.

Jews were still allowed to lend money, and another of Jakob’s sons, Isaac, displayed a particular gift for the business. When he died in 1807 at an advanced age, he left 25,000 florins in coin, plate and goods; but life continued to be hard for the Jews of Lengnau, and by the time Isaac’s grandchildren reached maturity his patrimony had all but disappeared.

One of them, Simon, worked as a tailor in the village for thirty years without any significant financial gain to show for it. He lost his wife in 1836, and had to bring up a son, Meyer, and four surviving daughters alone. By 1847 Meyer was nearly twenty and worked as a peddler, travelling in Switzerland and Germany. The younger daughters, though, presented a problem: Simon didn’t have enough of the money required by Swiss law (as applied to Jews) to provide them with dowries (which would then be taxed), so they were not allowed to marry.

The problem of matrimony touched Simon personally. He was fifty-five in 1847, but had become attached to a widow, Rachel Weil Meyer, fourteen years his junior. She had three sons and four daughters, but she also had a reasonable amount of capital. This, together with the value of Simon’s home and contents, should have been enough, they hoped, to persuade the authorities that they themselves had sufficient money to get married. But the authorities were unimpressed. Simon and Rachel had had enough. They began to look for a solution away from home.

In 1819 the Savannah, built at Savannah, Georgia, the first steam-assisted sailing ship designed to cross the Atlantic, had made the passage from her home port to Liverpool in twenty-five days. The ship had a full rig of sails, and only used her steam-driven paddles for the small proportion of the voyage when there was no wind; but her successful crossing suddenly brought the young republic of the United States much closer to Europe, and foreshadowed an era of relatively cheap, quick and reliable crossings of the ocean. Other, more sophisticated ships soon followed. America sought talent, labour and immigrants to bolster its still comparatively small European population, and to people its huge virgin territories. For the Jews of Europe the country had one massive attraction: there were no ghettos, and no discriminatory restrictions – unless, of course, you were a native American.

Jews from rural Germany, especially rural Bavaria, a very hard-pressed region, started emigrating early on, and their letters home carried nothing but praise for the New World. It was a huge step for Simon and Rachel, by the standards of the time already both well advanced in years, and rural Swiss-Germans with no other experience of the world; but repression at home offered them little alternative. Here was a place where they could live freely, not as barely tolerated and exploited ‘guests’, even though their family roots reached back centuries. They sold Simon’s property, pooled their resources, and set off with their children overland for Koblenz.

From there they continued to Hamburg, where they spent only a short time before taking steerage berths on a sailing ship – the cheapest passage they could find – bound for America. The voyage took eight weeks, the conditions were cramped and the travellers had to share them with a flourishing population of rats. Although dried fruit was supplied, the food was basic – chiefly hard-tack – and water was rationed very strictly. There was no privacy.

For Simon’s son Meyer and Rachel’s fifteen-year-old daughter Barbara, however, the discomfort of the journey was eclipsed by something far more important: they fell in love. By the time the American coastline rose on the horizon, they had decided – as soon as they could afford it – to marry. This strengthened Meyer’s resolve to do well. He was a small, energetic man, with strong features and a bulbous nose which many of his descendants, including his granddaughter Peggy, would inherit. Capable of kindness, and not averse to the finer things in life (good cigars and fine white wine featured in his later prosperity), he had a liberal side and a certain sense of humour. As a businessman, however, he was habitually mistrustful, cold and acute. He was obsessed with making money, and though he had an aptitude for it, he also worked at it relentlessly.

The joint families’ destination was Philadelphia, where they may already have had friends or relatives – it was the usual method for second- or third-wave immigrants to follow to where cousins or neighbours from the old country had already established bridgeheads, one reason being that few immigrants spoke the language of the new country when they arrived. Away from the north-east, the United States in 1848 was still more or less unexplored: the rapid colonisation and urbanisation of the next seventy years or so was only just getting under way. Philadelphia, however, founded by William Penn in 1682, was by now a prosperous and important city of some 100,000 people, including 2500 Jews. The Jews were integrated into the local community, but only held positions of minor social and financial standing.

Once they had disembarked, organised their modest baggage and adjusted to the unfamiliar, exciting and frightening environment, the large family set about finding a place to live. They rented a house in a poor district outside the city centre, and immediately Simon and Rachel married. The next thing to do, before their slender savings were exhausted, was to find work. Rather than seek employment, Simon and Meyer decided to work for themselves. As it would take more capital than they could afford to set up a tailor’s shop for Simon, they both took to peddling, the work Meyer already had experience in. Stores were few and far between and transport was hard, so most people, especially in outlying areas, tended to buy whatever they needed from travelling salesmen. Old Simon worked the streets of the town, while young Meyer left home each Sunday with a full pack for the country districts, not returning until the following Friday. It can’t have been easy, walking miles on foot, sleeping in the cheapest lodgings, with robbery and abuse a constant worry, but before long he had established both routes and a routine.

The Guggenheims had to learn fast – both the language and local business practice – but on the other hand they were free of all the laws and taxes imposed on Jews back in Switzerland, so there was a sense of liberation which made the graft easier to bear, and also motivated them. For Meyer especially this new beginning was stimulating, and he quickly discovered within himself a great aptitude for business. Iron stoves were rapidly replacing the old open hearths, and one of his best-selling lines was a form of blacklead for cleaning them. Meyer saw that if he could find a way of making his own polish, rather than buying it from the manufacturer, he could make a far greater profit while keeping his retail price low. In those days there was no law restricting such a practice, and history doesn’t relate how the manufacturer reacted to the loss of one small client, but Meyer took a can of the stuff he was buying to a friendly German chemist, who analysed it for him. Thus armed with the recipe, and after several messy experiments in his scant time off, Meyer not only produced his own stove blacking, but improved upon the original by making a version that would stay on the stove, but not on the hands of the person cleaning it. Before long he was selling his polish in such quantities that Simon gave up his own round and stayed home to produce it, using a second-hand sausage-stuffing machine. Soon Meyer was making eight to ten times the profit he had formerly made.

He didn’t stop there. Coffee was already taking hold as the favourite drink of America, but real coffee was extremely expensive. Poorer people drank coffee essence, a liquid concentrate of cheap beans and chicory. Meyer’s step-brother Lehman had already started to produce some of this at home, and now Meyer added it to his list of wares. By this time he was an experienced salesman with a reliable body of customers who trusted him. Four years after getting off the boat he was, at twenty-four, an established figure in the stoveblack and coffee-essence businesses. He married Barbara at Philadelphia’s Keneseth Israël Synagogue and the newlyweds set up house for themselves. It was a good match and a successful marriage. Barbara’s gentle and selfless personality made her the perfect complement to Meyer. She never questioned his authority and always supported him. She was a good mother to their children, and if she had a fault at all it might have been to over-indulge her younger offspring. Meyer, on the other hand, could be a stern disciplinarian. His youngest son, William, recalls in his memoirs that his father had ‘no tendency to spare the rod. Whippings were not infrequent; he employed a leather belt, a hairbrush, or any convenient paddle whenever the need suggested itself to him … None was allowed to doubt for long that his father’s word was law or to think that that law might be broken with impunity.’

From the start, Barbara showed an inclination to charitable work, which increased as her means did, though throughout her life she showed no inclination to use the money her husband earned to spoil or pamper herself. Just as Meyer established the business empire, ruthlessly developed by the more able of his sons after his death, so perhaps did their mother’s influence incline them to set up the charitable foundations for which the family remains famous, after they had made their fortune.

In the course of the next twenty years, Meyer and Barbara produced eight sons, including twin brothers, and three daughters. One of the twins, Robert, died in childhood, and their daughter Jeannette only lived to be twenty-six. But the survivors would grow up to be the heirs and developers of a business empire which was among the biggest half-dozen in America a century ago, and which was gathering strength when Meyer’s granddaughter Peggy was born.

Meanwhile, Meyer expanded and diversified his business interests, always driven by the desire to increase the security of his position in society by making ever larger sums of money. He didn’t necessarily cling to it – the years following his marriage would be punctuated by a series of house moves which tracked his rise in Philadelphia society – but he was extremely careful with it, and would never spend it unless there were some material, political, business or social gain to be made. One of his favourite proverbs came straight from the rural peasantry of his birth: ‘Roast pigeons don’t fly into your mouth by themselves.’ This dictum was one which he tried to inculcate into each of his sons: with Isaac, the oldest, born in 1854, he was not altogether successful, but with the three middle sons, Daniel (1856), Murry (1858) and Solomon (1861), he had greater success. The surviving twin, Simon (1867), also remained within the family fold; the surviving daughters, Rose and Cora, born in 1871 and 1873, following nineteenth-century practice both made good marriages and remained a credit to their parents. Benjamin (1865) and William (1868), however, followed their own paths, as we have seen.

As for education, Meyer, unlike his wife not particularly observant of his faith, chose the best for his children, regardless of religious affiliation, and they were sent to Catholic day schools, which paved the way for their disassociation from the religion and mores of their forefathers. Though Ben and William enjoyed the advantages of further education, only William showed any serious propensity for scholarship; the others were encouraged by their father to enter the family firm as soon as they could, and learn business through hands-on experience. The older boys, who worked hard alongside their father, were later aggrieved when Meyer decided to divide profits equally between all his sons; but Meyer countered their objections by pointing out that in time it would be the younger ones who would carry the burden of the work. He alluded to another piece of peasant wisdom: a bundle of sticks cannot be broken: individually, the sticks can be broken. The older boys knuckled under, but were not reconciled.

In the 1870s, having made small fortunes by the standards of the time in ventures as diverse as lye (used in soap-making) and the burgeoning railroads, Meyer turned his attention to lace. In 1863, all proscriptive laws against the Jews in Switzerland had been repealed, and one of Barbara’s uncles had established a lace factory back home. With a supplier established, Meyer now entered the lucrative lace business. His flair for diversification once again paid off, to the extent that by 1879 he was worth approaching $800,000. But his greatest gamble was yet to come. Two years later he was offered a third of the interest in two silver and lead mines outside the boom town of Leadville in Colorado by a Quaker friend, Charles Graham. Graham had borrowed money to buy two-thirds, but the mines, called the ‘A.Y.’ and the ‘Minnie’ after the original prospector and his wife, who had sold out for very little, were not doing well, and Graham couldn’t afford to repay the loan on half his share when it became due. William Guggenheim records that Graham’s price was $25,000, though it may have been as little as $5,000 – sources differ. In any event Meyer, who knew nothing about mining, thought it was worth the risk. His other partner was one Sam Harsh.

Before too long Meyer made his way to Leadville, in the wake of the disturbing news that the mines were flooded. To pump them out would cost $25,000, more than his two partners could afford. Meyer hesitated, but reflected that after all the investment in relation to his capital was still relatively small – and maybe too he was following what had so far proved to be an unerring instinct. He had steam-pumps developed for the job, the forerunners of a hydraulic power system which would be the cornerstone of his son Benjamin’s later business interests. He bought out his partners, had the mines cleared and repaired, watched the expenses mount, and worried and waited. But he didn’t have to wait long. In August 1881 rich seams both of lead and silver were struck. Soon the mines were bringing in $200,000 a year; by the end of the decade the yield had risen to $750,000.

Based on his experience with stove polish, Meyer saw that if he established his own smelting business, he need not pay anyone to process his ore for him. With the help of his then twenty-three-year-old son Benjamin, a smelter was established at Pueblo at the end of 1888. In the same year the family moved to a new home and new offices in New York, which had by now gained the ascendancy over all other cities in the east as the centre of commerce.

Lace was forgotten. Mining became the centre and the soul of the Guggenheim firm. The world was its unexploited oyster, and with the funds available to them over the years that followed they would gain control of the American smelting industry, and expand their mining operations to Mexico, Chile, Alaska and Angola. Profits would run into the hundreds of millions. They were not always good or ethical employers, their business practice could be sharp, and in those days nobody gave a damn about the ecological effects of mining operations; but they were phenomenally successful. Simply as a family they were formidable: Meyer and Barbara had to remember the birthdays of twenty-three grandchildren. The Guggenheim fortunes would continue to prosper until Peggy’s generation, less interested in business, came into its own.

Barbara, who had contracted diabetes, died on 20 March 1900. Ben and Will pulled out – and were partly pushed out – of the family firm soon after. The other brothers were only too happy to be rid of the interference of their pampered, college-educated siblings, whose ideas of how to run the business clashed with their own. Furthermore, Will, who fancied himself something of a ladies’ man, had blotted his copybook by making a very ill-advised marriage late in 1900, to a woman of dubious virtue. The older brothers coerced him into divorce, but then had to stump up a hefty $78,000 to satisfy the aggrieved ex-wife, although the whole business dragged on for another thirteen years, and in 1904 even threatened to bring scandal upon Will’s second and only slightly more successful marriage. Ben and Will were left with handsome incomes and some interest in the business, but only as far as it had come by the turn of the century. They were cut off from the vast amounts that would accrue to the Guggenheim companies after 1900.

Meyer, growing old, increasingly left the reins of the business to his son Daniel, dabbling in the stock exchange as a means of recreation. ‘When my grandmother died,’ Peggy wrote, ‘my grandfather was looked after by his cook. She must have been his mistress.’ This is a typical Peggy-ism, and need not necessarily be true – she always loved amorous intrigue. ‘I remember seeing her weep copious tears because my grandfather vomited. My one recollection of this gentleman is of his driving around New York in a sleigh with horses, he was unaccompanied and always wore a coat with a sealskin collar and a cap to match.’ The cook-mistress may be an exaggeration by Peggy, but a woman servant called Hannah McNamara sued Meyer for $25,000 shortly after Barbara’s death, claiming to have been his mistress for the past twenty-five years. Meyer denied the whole thing, and the unfortunate business blew over; but the servant’s allegations are not outside the bounds of possibility, and most of Meyer’s sons had one mistress or more at some stage in their lives.

But if there was someone who consoled him during his final years, Meyer kept her secret. He died in Florida, where he’d gone to recover from a cold, in 1905, nearly five years to the day after Barbara.

When Ben Guggenheim successfully wooed and won Florette Seligman in 1894, his family was already substantially richer than hers. But the Seligmans, though they had only arrived in the States about ten years earlier than the ‘Googs’, formed part of the Jewish élite of New York, and looked down on the family which had made so much money from mining and smelting. A Seligman family telegram to cousins back home in Germany may have been deliberately miswritten to show their contempt: ‘FLORETTE ENGAGED GUGGENHEIM SMELT HER’. However, no objection was raised to the match. No one could fail to respect the Guggenheim wealth, or the speed with which it had been made. Benjamin was a bit of a dandy and a bit of a womaniser; he had a warm personality and a delightful smile. Florette was on the plain side and her temperament was difficult. But from each family’s point of view, the union was advantageous.

Despite the difference in the status of the two families in New York, the story of the Seligman origins is remarkably similar to that of the Guggenheims. The little town of Baiersdorf lies midway between Bamberg and Nuremberg in Franconia, Germany. There was a Jewish community there from at least the mid-fourteenth century, and the last Jews belonging to it were deported to a concentration camp in Poland, where they died, in 1942. A large Jewish cemetery remains, and the town, as so many in Germany do, has its Judengasse – Jews’ Street. The Seligmann family – they would drop the second ‘n’ on arrival in America – arrived in Baiersdorf around 1680. In 1818 David Seligmann, a local weaver, married Fanny Steinhardt. The couple set up house in the Judengasse, and over the next twenty years produced eight sons and three daughters, just as the Guggenheims had done. Today there is a Seligmannstrasse in Baiersdorf, and a David and Fanny Seligman Kindergarten, endowed by the family.

Using some of her dowry, Fanny bought a stock of bed linen, bolts of cloth, lace and ribbons. With them she set up a small shop in the family home, and did so well that David’s none-too-impressive fortunes improved. He called himself a wool merchant, and started a sideline in sealing wax. He had to travel frequently on business, so that the upbringing of the children was left, to his misgiving, to his wife.

Travellers from outside Baiersdorf started to use Fanny’s shop, and by the mid-1820s their oldest son, Josef, had begun a modest currency-exchange business. In those days much of Germany consisted of small principalities, and coinage was not standardised, so Josef did a brisk trade, taking a small profit from each exchange. It was a short step from changing money for the convenience of users of his mother’s dry-goods store to running a regular currency exchange, and by the age of twelve the precocious Josef was even handling the occasional US dollar, among other truly foreign coinage.

Fanny was ambitious for all her children, but Josef was the apple of her eye. However, by the mid-1830s, the German rural economy was declining, as more and more people migrated to the increasingly industrialised cities, and Jews, subject to severe legal restrictions, found it ever harder to make ends meet. Some moved to the cities, but received no welcome there. Others began to look outside their native land. As Jewish migrants moved through the country westwards from oppression farther east, in Poland and Russia, word spread about the opportunities awaiting those who could afford, or who dared, to emigrate to America. In time, so great was the emigration that a duality arose in New York Jewish society not only between the insiders and the outsiders, but between those ‘older’ emigrants with German names, and those who mainly came later, with Russian and Slavonic names – these last being at the bottom of the social heap.

Fanny Seligmann had a strategy. Joseph was now fourteen, and she took the unprecedented step in her family of sending him to university in nearby Erlangen, where for two years he studied German literature, and learned some Latin, Greek, English and French. By the time he had graduated at sixteen he wanted nothing more than to spread his wings and go to the United States. Father David, now forty-six years old, a conservative, dour man, raised objections: emigrants were widely regarded as failures, and besides, there were rumours that Jews in America lost sight of their religion. But Fanny was adamant, and although it took her some time to persuade her husband, Josef was allowed to set off, aged eighteen, in July 1837, in the company of eighteen other men, women and children from the town. Fanny had managed to scrape together the money for his passage, and from somewhere too – possibly relatives in her home town of Sulzbach – she’d obtained $100 in US currency, which she carefully sewed into Josef’s knee-breeches. Then she waved him goodbye. She would never see him again. In 1841, aged only forty-two, Fanny died. She had given birth to her eleventh child, a daughter, two years earlier. It was clear that Fanny had been the backbone of the family. Soon after her death, her widowed husband, with several children still at home to look after, ran into financial difficulties.

The journey from Baiersdorf to Bremen, where Josef’s party was to take ship, took seventeen days, travelling overland in two wagons. The crossing on the schooner Telegraph took a further sixty-six days. Including Josef’s party, there were 142 people crammed on board. Passage cost $40, and included a cup of water and one meal a day – which unfortunately consisted of pork and beans, so Josef quickly had to ignore his father’s parting injunction not to forget the Jewish dietary laws. Even so he lost weight on the journey – no bad thing, as he always had a tendency towards corpulence. On the journey he also fell in love, with the daughter of his group’s leader Johannes Schmidt. But unlike Meyer’s, it was simply a shipboard romance, ending in a tearful parting when the Telegraph docked at New York.

Josef, who immediately anglicised his name – to Joseph Seligman – on arrival in America, as all his brothers who followed would, had more on his mind than regretting the girl. He was a young man driven by ambition, and with a similar motivation to Meyer’s: in money lay security. Soon after his arrival he set off on a hundred-mile hike – he wasn’t going to waste any money on transport, and must have been innocent of the perils of the road – down to Maunch Creek, Pennsylvania, where he had an introduction to a cousin of his mother’s. Maunch Creek wasn’t much of a place, but Joseph quickly got a job, at $400 a year, as financial clerk to a canal-boat building company. He made friends with the boss; the Seligmans would always have the knack of striking up good relationships with the right people, in this case Asa Packer, a small-town businessman who would prove to be an invaluable contact. Packer went on to become a multi-millionaire, the founder of a university, the president of a railroad, and a US Congressman.

After a year, Joseph turned down the offer of a generous pay-rise and invested the $200 he’d saved in various portable goods. With them he set off on foot, carrying a two-hundred-pound pack, peddling to farms in the region. It was hard and sometimes dangerous work, but Joe was tough and single-minded. He was also a brilliant salesman, and within six months he had made a profit of $500, part of which he sent off to his two next-eldest brothers, Wolf and Jakob, who were longing to join him, as their passage-money.

Wolf and Jakob – renamed William and James on their arrival in America – were not all-rounders like Joseph. William was idle, and liked the good life, which annoyed his older brother. James however, while not particularly good at accountancy, turned out to be the best salesman of all of them. By 1840 the brothers had bought a place to use as their headquarters in Lancaster, fifty miles west of Philadelphia; the following year the next brother, Jesaias (who became Jesse), came over aged fourteen, and quickly proved to be the accountant the enterprise needed. Over the next two years, growing profits enabled Joseph to get the rest of his family, including his father, over to the New World.

James, handsome, confident and intelligent, showed an aptitude for salesmanship which surpassed even his oldest brother’s, and in 1846 he was delegated to open the New York branch of the family’s fast-expanding dry-goods business. At about the same time Jesse and his youngest brother Henry (Hermann) were establishing another branch at Watertown, in upstate New York. There, Jesse made friends with an army lieutenant stationed nearby. This would turn out to be another fortunate relationship, since the lieutenant’s name was Ulysses S. Grant.

The Seligmans continued to live modestly, even after their business expanded to cover most of the country. As a result of the Gold Rush to San Francisco in the 1850s they were able to reap mighty profits, since gold fever led to enormous price hikes. A blanket bought for $5 could sell for $40, and a quart of whiskey went for $25. Profits from California became the mainstay of the Seligman organisation.

But a new dimension soon crept into their interests. Much of the profit from the west coast took the physical form of gold bullion, which the New York branch used not only to buy new stock, but also to trade on the market. Banking in the United States didn’t become formally regulated until after the Civil War, and there was no bar to anyone entering the field. It didn’t take long for the Seligmans to realise that interest never stopped earning. They loaned, bought and sold IOUs, and eventually offered deposit accounts. By 1852 Joseph, aged thirty-three, was a major New York banker and investor. The only mistake the family made, based no doubt on their traditional thinking, was to avoid tying anything up in property: by and large, they rented. Thus at one point they passed up the chance to buy about one-sixth of Manhattan.

The Seligmans were now solidly established. During the Civil War they sold uniforms to the Union Army, and took the risk of being paid in Treasury Bonds. It paid off, and when the war was over, with their old friend Grant a Yankee hero, they were able to cash in on the post-war boom. Although New York high society was riddled with elaborate rules and regulations, which tacitly excluded Jews from its inner sanctum, no one in business could afford to ignore them. By the mid-1860s the Seligman brothers and sisters had produced about eighty children between them. When Grant became president in 1869, he offered Joseph the post of Secretary to the Treasury. For the first time Joseph faltered. He may have been a millionaire at fifty, but at heart he was still an immigrant Jewish kid, and his confidence failed him. On his own turf, however, he remained king, and the linchpin of the clan’s business activities.

Although by no means on a par with the Astors, Morgans, Vanderbilts or Whitneys, the Seligmans continued to expand. They never had as big a break as the Guggenheims had in mining, but like them they diversified into railroads, and, famously, into the Panama Canal venture. After the builder of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps, failed to achieve the same success in Central America, the Seligmans were able not only to divert interest from a rival canal construction in Nicaragua, but to finance a revolution for Panamanian independence from Colombia in return for the canal contract.

The Guggenheims were always out-of-towners, and were thus less affected by the implicit anti-Semitism of New York society than the Seligmans were. As the Seligmans’ wealth increased, so did their desire to be accepted. Joseph had long since forgotten his father’s injunctions to be strictly observant of his faith, and he and his brothers wanted nothing more than to be accepted by the great and the good. Being Jewish and having a German accent didn’t help, no matter how much money one had, and however much one learned which knives and forks to use when and how to hold them properly, and the correct manner of presenting a calling card. As in the Great Plague of the Middle Ages, so in the temporary financial panic year of 1873, Jews were blamed.

Oddly enough, Sephardic Jews were more likely to be accepted. Moses Lazarus had been one of the founders of New York’s Knickerbocker Club, second in exclusivity only to the Union Club. His daughter Emma even wrote the verse that adorns the Statue of Liberty: ‘Give me your tired, your poor …’ For Ashkenazi Jews, especially those from Germany, it was a different matter. Just as in time they would look down on the Slav and Russian Jewish immigrants, so now they were the newcomers, and their financial acumen meant that they were the victims of envy and its attendant spite.

Still they longed to be accepted. Their synagogue, the Temple Emanu-El on 5th Avenue, was reformed and Americanised. But they also took pride in their old country. They founded their own exclusive clubs: until 1893 the Harmonie Gesellschaft hung a portrait of the Kaiser on its walls. And although the Seligmans had anglicised their first names, they wouldn’t touch their surname (except for dropping the second ‘n’). When William once suggested it, Joseph retorted that if he wanted to, he had better change his to schlemiel. By the late nineteenth century the Ashkenazi Jews of New York comprised a formidable group, including the Contents, the Goldmans, the Kuhns, the Lehmans, the Lewinsohns, the Loebs, the Sachses and the Schiffs. However, when it came to names for their children, Gentile and patriotic American ones were chosen. The thing to do for prominent Jews was to play down their Jewishness. But whatever they did, anti-Semitism remained a core element of society, and Jewish new arrivals found it impossible to avoid or ignore. That it rankled long with Joseph is proven by one dramatic incident.

The Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga had been owned by one Alexander T. Stewart. On his death in 1876 Stewart had left its management to a friend, Harry Hilton, who shared his right-wing views. Stewart had envied Joseph Seligman from the time that Seligman had turned down the Treasury post, which Stewart coveted. It hadn’t helped that Stewart’s subsequent application for the job had been rejected by the Senate.

The hotel had begun to lose money even before Stewart’s death, and Hilton and he believed this was because the Gentile clientele didn’t like the admission of Jews. It wasn’t uncommon for expensive hotels, clubs and even restaurants to refuse admission to Jews in those days, and Saratoga was a major resort for the wealthy. It isn’t clear whether the Seligman family actually went to the hotel in the summer of 1877, or whether they were forewarned: it seems highly unlikely that they would not have booked beforehand. It is possible that Joseph arrived with his family and his baggage in the knowledge that he would provoke a rejection. If so, the humiliation he received must have been half expected. Whatever the truth of the matter, they were rebuffed.

There was a storm in the press, and a furious exchange of letters. Seligman sued Hilton. The liberal elements in society took up Joseph’s cause. But Hilton stuck to his guns: he didn’t like Jews, and they were bad for business. The courts did not find in favour of Seligman, and several other hotels in the Adirondacks, emboldened by Hilton’s move, also introduced a ‘no-Jews’ policy. The only satisfaction Joseph could derive from the affair was the successful boycott of the largest New York department store, also formerly owned by Stewart and now managed by Hilton, which closed as a result. The effect of the case on Joseph was profound: he never recovered from it, perceiving it as the ultimate rejection by a society he had striven all his life to belong to, and into which he had put so much. He died at the end of March 1879, in his sixtieth year. A sad postscript is the resignation as late as 1893 by Jesse Seligman from the Union League Club, his favourite, which his brothers Joseph and William had also been involved in, when, extraordinarily, Jesse’s son Theodore was refused membership on anti-Semitic grounds. Like his older brother, Jesse found that New York was soured for him, and that he had never been truly accepted, even after forty-odd years in the city. He died a year later, leaving $30 million.