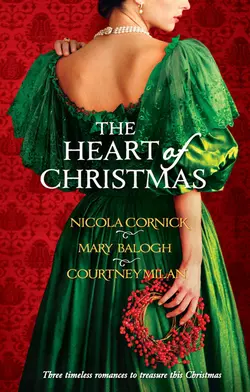

The Heart Of Christmas: A Handful Of Gold / The Season for Suitors / This Wicked Gift

Nicola Cornick и Courtney Milan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 920.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A HANDFUL OF GOLD by Mary Balogh Not only is Julian Dare dashing and wealthy, but he′s the heir to an earldom. So what do you get a man who has everything? Innocent, comely Verity Ewing plans on giving him her heart—the most precious gift of all.THE SEASON FOR SUITORS by Nicola CornickAfter some close encounters with rakes, heiress Clara Davenport realizes she needs expert advice. And who better than Sebastian Fleet, the most notorious rake in town? But the tutelage doesn′t go as planned, as both Sebastian and Clara find it difficult to remain objective in lessons of the heart! THIS WICKED GIFT by Courtney MilanLavinia Spencer has been saving her pennies to give her family Christmas dinner. Then her brother is swindled, leaving them owing more than they can ever repay. Until a mysterious benefactor offers to settle the debt. Lavinia is stunned by what dashing William White wants in return. Will she exchange a wicked gift for her family′s fortune?