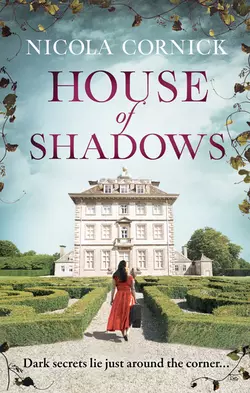

House Of Shadows: Discover the thrilling untold story of the Winter Queen

Nicola Cornick

For fans of Barbara Erskine and Kate Morton comes an unforgettable novel about three women and the power one lie can have over history.London, 1662:There was something the Winter Queen needed to tell him. She fought for the strength to speak.‘The crystal mirror is a danger. It must be destroyed – ‘He replied instantly. ‘It will’.Ashdown, Oxfordshire, present day: Ben Ansell is researching his family tree when he disappears. As his sister Holly begins a desperate search, she finds herself inexplicably drawn to an ornate antique mirror and to the diary of Lavinia, a 19th century courtesan who was living at Ashdown House when it burned to the ground over 200 years ago.Intrigued, and determined to find out more about the tragedy at Ashdown, Holly’s only hope is that uncovering the truth about the past will lead her to Ben.‘Fans of Kate Morton will enjoy this gripping tale.‘– Candis

NICOLA CORNICK is a historian and author. She studied at London University and Ruskin College Oxford and works for the National Trust as a guide at the seventeenth century hunting lodge Ashdown House in Oxfordshire. Her award-winning books are international bestsellers and have been translated into 26 languages.

ISBN: 978-1-474-03808-9

HOUSE OF SHADOWS

© 2015 Nicola Cornick

Published in Great Britain 2015

by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

Version: 2018-06-29

To Andrew, who has lived with my obsession with Ashdown House and William Craven for many years.

All my love as always.

Let your life lightly dance on the edges of Time.

Rabindranath Tagore

Acknowledgements (#ulink_88c16fea-7f37-5756-8f21-4d933bed68f2)

All my thanks go to my wonderful editor Sally Williamson who had faith in me to write this book and who gave me endless encouragement and support. I’m also hugely grateful to all my writing friends, especially the Word Wenches and the lovely Sarah Morgan for giving me the confidence finally to write the book of my heart.

I am very fortunate to work as part of a great team of volunteers at Ashdown House. Thank you all for sharing your knowledge and for being so much fun to work with. Special thanks go to Maureen Dawson and to Richard Henderson at the National Trust.

I’d also like to thank Denny Andrews for showing me the site of Coleshill House and Neil Fraser for being so generous in sharing his archive on the Ashdown Estate.

I would like to pay tribute to the late Keith Blaxhall, for many years the Estate Manager at Ashdown Park. His enthusiasm and encouragement was inspiring to me and it was a great privilege to have known him.

Finally a big thank you to Julie Carr for allowing me to ‘borrow’ her lovely dog Bonnie for this story, and to Bonnie herself for graciously agreeing to star in House of Shadows.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u06e74c17-b31d-53d7-83e2-fb4d7f7789ec)

About the Author (#u110cb157-68ae-5957-b362-f599102432ce)

Title Page (#ubb91d28a-868e-5aee-a4ed-e6a0f8e500bd)

Copyright (#uc8f36ce3-31f5-5ca5-b588-399e118e1cdb)

Dedication (#u18018a90-63d4-5324-9554-7b5b2d35c8e6)

Epigraph (#u8eb7ac93-b553-5782-89f1-2c8cf6d7207d)

Acknowledgements (#uc60519fa-22ad-5390-9f9c-6dc941e1f984)

Prologue (#ufff634ef-c8b1-542f-993f-854dc54388a8)

Chapter 1 (#u4ca2de71-007e-5322-8327-0382baeac7d4)

Chapter 2 (#ub68a13c6-f95b-57ba-9a40-09600be8c0ea)

Chapter 3 (#ua0944154-93a7-547e-a64b-e9269b0b4cea)

Chapter 4 (#u53fc19dd-da95-5a55-be1f-aae95af4cff2)

Chapter 5 (#u950e416c-aae0-5bf9-95ed-3c4d3edf11e8)

Chapter 6 (#u5efdd78d-9d5c-5d23-afa6-dd7294d2c7fe)

Chapter 7 (#ua87795c5-f9a2-5f67-acd1-3bace4494427)

Chapter 8 (#u03109c46-e0d3-5d8d-9aca-f4f500881430)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Author Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract from The Woman in the Lake (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_73408c36-cc75-5f48-b905-26d1455bbcb5)

London, February 1662

She dreamed about the house on the night before she died. In the dream she felt as insignificant as a child; a miniature queen clad in a cream silk gown embroidered with gold. The collar prickled the nape of her neck as she craned her head to gaze up, up at the dazzling white stone of the house against the blue of the sky. It made her dizzy. Her head spun and the golden ball that adorned the roof seemed to plunge like a shooting star falling to earth.

Beyond the walls of her bedchamber crouched the city; filthy, noisy and seething with life. But in her dreams she was far from London; she had followed the wide ribbon of the Thames upriver, past the hunting ground at Richmond, and the great grey walls of Windsor, to a place where two rivers met. She took the narrower path through drowsy meadows thick with daisies and the hum of bees, for in her dream she was a summer princess, not a winter queen. The river became a chalk stream that bubbled up from springs deep in the dappled woods until finally she burst out of the shade and onto the highlands, and there was the house in a hollow of the hills, a little white palace fit for a queen.

Her lips moved. One of her women, weary, anxious, attentive, bent to catch the whisper. It could not be long now.

‘William.’

It caused consternation. She had sent him away, her cavalier, told her servants to bar the door against him.

‘Madam …’ The woman was uncertain. ‘I don’t think—’

The queen’s eyelashes flickered. Her eyes, blue-grey, were clear, imperious.

‘At once.’

‘Majesty.’ The woman curtsied, ran.

The room was hot, windows and doors closed, fire roaring. She drifted between sleep and waking, on the fringes of shadow. Outside, dawn was breaking over the river, the water rippling with a silver wake. It was unseasonably mild for February and the air felt heavy, waiting.

He came.

She heard the stir, felt the cool shift of the air before the door closed again, sealing them in.

‘Leave us.’

No one argued, which was good because she was too tired for arguments now. Her eyes would not open. In the silence she could hear everything though; the hiss of the fire as a log settled deeper in the grate, the creak of the floorboards beneath his boots as he crossed the room to her side.

‘Sit. Please.’ It was an effort to speak. There was no time for discussion now, or apologies, even if she had wished to make them, which she did not.

He sat. Now that he was close she could smell on him the night cold and the scent of the city. She could not see him but she did not need to. She knew every plane of his face, each line, each curve. It was as though they were written on her heart, an indelible picture.

There was something she needed to tell him. She fought for the strength to speak.

‘The crystal mirror—’

‘I will get it back. I swear it,’ he replied instantly. A second later his hand grasped hers, warm and reassuring but still she shook her head. She knew it was too late.

‘It will elude you,’ she said.

He had never understood the power of the Order of the Rosy Cross or its instruments, though perhaps he did now, now that the damage was done.

‘Danger to you—’ She tried one last time to warn him. ‘Take care or it will destroy you and your kin as it did me and mine.’ She was gasping for breath, frightened.

His fingers tightened on hers. ‘I understand. Believe me.’

She felt the knot inside her ease. She had to trust him. There was no alternative. Her life was unravelling like a skein of wool. Soon the thread would run out.

‘I want you to take this. Keep it safe, hidden.’ With an effort she opened her eyes and unclenched the fingers of her right hand. A huge pearl spilled into her lap, glowing with baleful fire in the subdued light. Even now, looking on it for the last time, she could not like it, for all its ethereal beauty. It was too powerful. It was not the fault of the jewel, of course, but of the men who had sought to use it for their own wicked purposes. Both mirror and pearl had once been a force for good, strong and protective, until their power had been corrupted through the greed of men. The Knights had been warned not to misuse the instruments of the Order and they had disobeyed. They had unleashed destruction through fire and water, just as the prophecy had foretold.

She heard the catch of Craven’s breath. ‘The Sistrin pearl should be given to your heir.’

‘Not yet.’ She was so very tired now but this last task must be completed. ‘You need to break the link between the pearl and the mirror. One day the mirror will return and then it must be destroyed. Keep the pearl safe until that is done.’

Craven did not refuse her gift or tell her that he had no time for superstition. Once he had scorned her beliefs. No longer. She watched him scoop up the pearl on its heavy gold chain and stow it within his shirt. His face was grave and set, as though he were facing battle, such was the weight of her commission.

‘Thank you.’ Her smile was weary. Her eyes closed. ‘I can sleep now.’

There was a sudden commotion. The door swung back with a crash and a protesting creak of hinges. Voices; loud, commanding. Footsteps, equally loud: her son Rupert, come to be with her at the end, always hasty, always late.

There was so little time now.

She opened her eyes again. The room swam with shadows and the red and gold of firelight but she felt cold. She looked on Craven for the last time. Grief was etched deep into his face.

‘Old,’ she thought. ‘We have had our time.’ The loss cut her like a knife. If only …

‘William,’ she said. ‘I am sorry. I wish we had another chance.’

His face lightened. He gave her the smile that had shaken her heart from the moment she had first seen him.

‘Perhaps we shall,’ he said, ‘in another life.’

She forgot that her time could be measured in breaths now, not hours or even minutes, and tightened her grip urgently on his hand.

‘The Knights of the Rosy Cross believed in the rebirth of the spirit,’ she said, ‘but it is against the Christian teaching.’

He nodded. His eyes were smiling. ‘I know it is. Yet still I believe it. It comforts me to think that we shall meet again in another time.’

Her eyes closed. A small smile touched her lips. ‘It comforts me, too,’ she said softly. ‘Next time we shall be together always. Next time we shall not fail.’

Chapter 1 (#ulink_c9556483-e057-55ee-944f-8aa8125d982f)

Palace of Holyroodhouse, Scotland, November 1596

King James paused with his hand already raised to the iron latch. Even now he was not sure that he was doing the right thing. A spiteful winter wind skittered along the stone corridor, lifting the tapestries from the walls and setting him shivering deep within his fur-lined tunic.

The pearl and the mirror should be given to Elizabeth, that was indisputable; they were her birthright. Yet this was a dangerous gift. James knew their power.

The Queen of England had made no show of her baptismal present to her goddaughter and namesake. In fact it was widely believed that Mr Robert Bowes of Aske, who had stood proxy for Her Majesty at the christening, had brought no gift with him at all. It was only after the service had been completed, the baby duly presented as the first daughter of Scotland, and the guests had dispersed to enjoy the feast, that Aske had called James to one side and passed him a velvet box in which rested the Sistrin pearl and the jewelled mirror.

‘These belonged to your mother,’ Bowes had said. ‘Her Majesty is eager that they should be passed to her granddaughter.’

For diplomacy’s sake James had bitten back the retort that had sprung to his lips. Trust the old bitch of England to present as a gift those items that were his daughter’s by right. But then he could play this game as well as any; he had paid Elizabeth of England the compliment of naming his firstborn girl after her. It was outrageous flattery for his mother’s murderer, but politics was of more import than spilt blood.

‘Majesty?’

He turned. Alison Hay, the baby’s mistress-nurse was approaching. Her face bore no trace of surprise or alarm, although he could only imagine her speculation in finding King James of Scotland dithering outside his baby daughter’s chambers. He should have thought to send for one of the Princess Elizabeth’s attendants rather than to loiter like a fool in cold corridors. But Mistress Hay’s arrival had brought with it relief. There was now no cause to knock or to enter this realm of women. James’ insides curdled at the thought of the stench of the room, of stale sweat and that sweetly sour smell that seemed to cling to a baby. The women would all be grouped about the child’s cradle, fussing and smiling and clucking like so many hens. Thank God that soon they would all be departing for Linlithgow where the princess would have her own household under the guardianship of Lord and Lady Livingston.

He groped in his pocket and his fingers closed over the black velvet of the box.

‘This is for the Princess Elizabeth. A baptismal gift.’ He held it out to her.

Mistress Hay did not take the box immediately. A frown creased her brow.

‘Would Your Majesty not prefer to give it to Lady Livingston—’

‘No!’ James was desperate to be rid of the burden, desperate to be gone. ‘Take it.’ He pushed it at her. The box fell between their hands, springing open, the contents rolling out onto the stone floor.

He heard Mistress Hay gasp.

Few men – or women – had seen either the Sistrin pearl or the jewelled mirror. The pearl had never been worn and the mirror had never been used. Both were shaped like teardrops. Both shone with an unearthly bluish-white glow, the one seeming a reflection of the other: matched, equal, alike.

The pearl had been born of water, found in the oyster beds of the River Tay centuries before, and had been part of the collection of King Alexander I. The mirror had been forged in fire by the glassblowers of Murano, its frame decorated with diamonds of the finest quality and despatched as a gift to James’ mother Mary, Queen of Scots on her marriage. Mary had delighted in the similarity of the two and had had the rich black velvet box made for them.

Yet from the first there had been rumours about both pieces. The Sistrin pearl was said to have formed from the tears of the water goddess Briant and to offer its owner powerful protection, but if its magic was misused it would bring death through water. There were whispers that the Sistrin had caused King Alexander’s wife Sybilla to drown when Alexander had tried to bind its power to his will. The mirror was also a potent charm, but it was said that it would wreak devastation by fire if it were used for corrupt purposes. James was a rational man of science and he did not believe in magic, but something about the jewels set the hairs rising on his neck. If he had been of a superstitious disposition he would have said that it was almost as though he could feel their power like a living thing; crouched, waiting.

Alison Hay was on her knees now, scrabbling to catch the pearl before it rolled away and was lost down a drain or through a crack in the floor. James did not trouble to help. He did not want to touch it. The mirror lay where it had fallen, facing up, miraculously unbroken.

Alison grabbed the pearl and struggled to her feet, flushed, breathing hard. In one hand she had the box, the pearl safely back within it, glowing with innocent radiance. In the other she held the mirror. As James watched, she glanced down at its milky blue surface. Her eyes widened. Her lips parted. James snatched it from her, bundling it roughly face down into the box and snapping the lid shut.

‘Don’t look into it,’ he said. ‘Never look into it.’

It was too late. Her face was chalk white, eyes blank pools.

‘What did you see?’ James’ voice was harsh with emotion. Terror gripped him, visceral, setting his heart pounding. Then, as she did not reply: ‘Answer me!’

‘Fire,’ she said. She spoke flatly as if by rote, ‘Buildings eaten by flame. Gunpowder. Death. And a child in a cream-coloured gown with a crown of gold.’

‘Twaddle.’ James gripped the box as though he could crush the contents; crush the very idea of them. ‘Superstitious nonsense, all of it.’ Yet even he could hear the hollow ring of fear in his voice. Before magic, cold reason fled.

‘Lock them away,’ he said, pushing the box back into the nurse’s hands. ‘Keep them safe.’

‘Majesty.’ She dropped a curtsey.

It was done. From behind the closed door he heard the thin wail of a baby and the murmur of female voices joined in a soothing lullaby. James turned on his heel and walked away, heading for the courtyard and the fresh clean air of winter to chase away the shadow that stalked him. Yet even outside under a crystalline grey sky plump with snow he was not free of guilt. He had given the Sistrin and the mirror to his baby daughter, as the Queen of England had commanded, but it felt that in some terrible way he had cursed her with it.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_18425b2a-016a-581f-bb06-98b5f43ef7ae)

Wassenaer Hof, The Hague, autumn 1631

There was a full moon and a cold easterly wind when the Knights of the Rosy Cross came. The wind came from the sea, crossing the wide sand dunes and whipping through the streets to curl about the corners of the Wassenaer Hof, seeking entry through cracks and crannies.

Elizabeth watched the knights’ arrival from her window high in the western wing of the palace. The moonlight dimmed the candles and fell pitilessly bright on the cobbles. In that white world the men were no more than dark cloaked shadows.

She had thought that such folly was over. The Fellowship of the Rosy Cross belonged to a time long ago. It had been a dream borne of their youth. She and her husband Frederick had been so passionate about it once. They had been possessed of a desire to change the world, to spread knowledge, science and wisdom. Their court at Heidelberg had been a refuge for scholars and philosophers.

Now she felt so very different, drained of faith, betrayed, as flimsy as the playing card for which she was named the Queen of Hearts.

She was a pale reflection; an echo fading into the dark. Men had called her union with Frederick the marriage of Thames and Rhine; a political match between a German prince and an English princess destined to strengthen the Protestant cause. She had not cared for such things. She had not been educated for politics then. It had been simple; one look at Frederick and she had fallen in love. They had wed in winter but she had felt blessed by light and fortune. Frederick’s ascent to the throne of Bohemia had been the final glory. The future had been so bright, but it had been a false dawn followed by nothing but grief and loss. Bohemia had been lost in battle after only a year, Frederick’s own lands overrun by his enemies. They had fled to The Hague to a makeshift court and a makeshift life.

Elizabeth rested one hand on her swollen belly. After eighteen years of marriage and twelve children, people spoke of her love for Frederick in terms of indulgence, never questioning her devotion. They knew nothing.

Tonight she was so angry. She knew why Frederick had summoned the knights. There was new hope, he said. Their long exile would soon be over. The Swedish King had smashed the army of the Holy Roman Emperor and was sweeping through Germany in triumph. Frederick wanted the Knights of the Rosy Cross to scry for him, to see whether Gustavus Adolphus’ victory would give him back his patrimony. He had taken both the Sistrin pearl and the crystal mirror with him to foretell the future; the knights demanded it. But the treasures were not Frederick’s to take; they were hers.

Elizabeth felt restless. Her rooms were noisy. They always were; her ladies chattered louder than her monkeys. She was never alone. Tonight though, she was in no mood for music or masques or cards. Suddenly the repetition of her life, the sameness, the tedium, the hopes raised and dashed time and again, made her so frustrated that she shook with fury.

‘Majesty?’ One of her ladies spoke timidly.

‘Fetch my cloak,’ Elizabeth said. ‘The plain black.’

They bustled around her like anxious hens. She should not go out. His Majesty would not like it. It was too cold. She was with child. She should be resting.

She ignored them all and closed the door on their clucking. Down the stairs, along the stone corridor, past the great hall with its gilded leather, where the servants were sweeping and tidying after supper, out into the courtyard, feeling the sting of the cold air. She passed the stables and as always the scent of horses, leather and hay comforted her. Riding – hunting – made her life of exile tolerable.

She looked back across the yard at the lights of the palace winking behind their brightly coloured leaded panes. She had never considered the Wassenaer Hof to be her home, even though she had lived in The Hague for over ten years now. They still called her the Queen of Bohemia, but in truth she reigned over nothing but this palace of red brick with its jostling gables and ridiculous little towers.

The building was swallowed in shadows. Here in the gardens there was the sharp scent of clipped box that always caught in her throat and the sweet smokiness of camomile. The gravel of the parterre crunched beneath her feet. She could never walk here without thinking of the gardens Frederick had designed for her at Heidelberg Castle, with their grottoes and cascades, their orange trees and their statuary. All had been on a grand scale that had matched Frederick’s ambition. All gone. She had heard that an artillery battery now stood on the site of her English Garden. As for Frederick’s ambition, she had believed that had been crushed too, struck down at the Battle of the White Mountain, buried under the losses that had bruised his honour and his fortune alike. But then, tonight, he had sent for the Knights of the Rosy Cross and brought them here, to the water tower, to tell him if his fortunes would rise again.

He had taken their son, too. Charles Louis was a mere thirteen years old, but Frederick had said it was time his heir should see what the future held for him. That had angered Elizabeth too. She had already lost one son and kept Charles Louis close. He was too precious to put in danger.

She drew the hood of the cloak more closely about her face. The scrape of the metal latch sounded loud in her ears; the wall sconce flared in the draught. She closed the door softly behind her and started to descend the stone steps to the well, taking care to make no noise. It was odd that for all that the old tower was dry and the stair well lit, she felt as though the water had seeped into the very stones and now lapped around her, inimical and cold. She had hated water ever since it had taken the life of her eldest son two years before. Even now, his drowning haunted her dreams. She could not shake the belief that in some way she and Frederick had brought the loss upon themselves through the misuse of the Sistrin pearl’s magic. Her father had warned her of its power and told her it should never be used for personal gain.

Elizabeth shivered, clutching the edge of her cloak closer to ward off the cold. Below she could hear the sound of water now; when the well was full the overflow from the Bosbeek, the forest stream, flowed through an arched drain and out into the Hofvijver Lake. Tonight it sang softly as it ran. The music of the water was a good omen. Frederick would be pleased.

Another step and she passed the guardroom on the left. Shadows shifted behind the half-open door. She held her breath and trod more softly still, down towards the sacred well.

At the bottom of the spiral stair the space opened out into a room with a vaulted ceiling held aloft by stone pillars. It was familiar to her, as were the items on a table to the right: a bible, a skull, an hourglass, a compass and a globe, the tools of the Knights’ trade. Flames burned high in a wide stone fireplace, the golden light rippled over the water of a star-shaped well in the opposite corner of the room. The Knights were kneeling around the edge. The well had a shallow inner shelf and Elizabeth knew they would have placed the Sistrin pearl on that ledge, in its natural element of water. They were waiting for the jewel to exert its magic and reflect the future in the crystal mirror.

Light fractured from the crosses each man wore, some silver, some a soft rose gold that seemed to glow with a radiance of its own. Elizabeth could see the mirror in Frederick’s hand, the diamonds shining with the same dark fire as the crosses. She did not look at the reflection in the glass itself. She feared the mirror’s visions.

The heat was overpowering and the air laden with smoke and the sweet-woody scent of frankincense. The sun, moon and stars on the knights’ robes seemed to spin before her eyes. Her head ached sharply. Caught off guard, Elizabeth took a step back. She put out a hand to steady herself against one of the stone pillars but met thin air.

Someone caught her from behind, his hand over her mouth, one arm about her waist, pulling her out of the room, swinging the door shut behind them. It was sudden and shocking; no one touched the Queen, least of all manhandled her. Instinct took over; instincts she did not know she possessed. She bit down hard, tasting the tang of leather against her tongue, and he released her at once, though the bite could not have hurt and nor could her feeble attempts to lash out with boots or elbows.

‘Hellcat.’ His voice was deep and he sounded amused, as though her puny efforts were pitiful. She was the one who was angry and she allowed herself to indulge in it.

‘You fool.’ She spun around to face him. She was shaken, ruffled, more than she ought to have been. ‘Don’t you know who I am?’

She saw his eyes widen, hazel eyes, which held more than a hint of laughter. In the flaring torchlight she could see he was of no more than average height, which still made him several inches taller than she. He looked strong though, and durable. His hair was a rich chestnut, curling over the white lace of his collar, his nose straight, a cleft in his chin. And even in this moment of stupefaction, even as he recognised her, there was still amusement in his face rather than the deference he should be showing her.

‘Your Majesty.’ He bowed.

She waited, haughty. His lips twitched.

‘Forgive me,’ he said smoothly, after a moment. Nothing more, and it did not sound like a request, still less like an apology.

He was young, this man, a good deal younger than she was, possibly no more than two- or three-and-twenty. Elizabeth thought she recognised him, though she did not know his name. She could see he was a soldier not a courtier. Unlike the Knights of the Rosy Cross he was clad plainly in shirt, breeches, cloak and boots. There was a sword at his side and a knife in his belt.

Heat and sudden tiredness hit her again, making her sway. Perhaps her ladies had been right, damn them. She was six months pregnant and should have been resting.

The expression in his eyes changed from amusement to concern. He took her hand, drawing her forwards.

‘Come into the guardroom—’

‘No!’ She hung back. ‘I don’t want anyone to see me …’

‘There is no one here but me.’

She allowed him to usher her through the door into the small chamber. It was Spartan, with a bare floor and one candle on a battered table. A meagre fire glowed in the grate. It was no place for a Queen but there was a chair, hard and wooden, and Elizabeth sank down onto it gratefully.

‘You are guarding the ceremony alone?’ she asked.

‘I am.’ He looked rueful. ‘Badly, it would seem.’

She smiled at that. ‘You could not have anticipated this.’

‘That the Queen herself would choose to come and watch?’ He shrugged, half-turning aside to pour her a cup of water from the carafe on the table. ‘I suppose not.’

‘I am a member of the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross,’ Elizabeth said. ‘I have every right to be here.’

His hand stilled. He turned back, dark brows raised. ‘Then why not exercise that right openly? Why creep in like a thief?’

Few things surprised Elizabeth these days. Few people challenged her. It was one of the privileges of royal blood, to be unquestioned. ‘Never explain, never complain’ was an adage that her mother, fair, frivolous Anne of Denmark, had taught her. This man evidently thought that a commoner might question a queen.

All the same she chose to ignore his question, tasting the water he passed her instead, which was warm and brackish but not altogether unpleasant.

‘I don’t believe I know you,’ she said.

He bowed again. ‘William Craven. Entirely at your service.’

Many men had said those words to her over the years. The court was crowded with young men such as this William Craven; men who dedicated themselves and their swords to her service. She knew that some saw her as a princess in distress, others as a martyr to the Protestant cause, unfailingly courageous in the face of adversity. Sometimes she wanted to tell them that there was no place for romantic gallantry in either war or politics. The years of exile had taught her that war was brutal and dangerous, and that politics were corrupt and ground on tediously slowly. But of course she never said so. They all maintained the pretence.

‘Lord Craven,’ she said. ‘Of course. I have heard much about you.’

His mouth turned down at the corners. ‘I too have heard what men say about me at the court.’

She met his gaze very directly. ‘What do they say?’

He smiled ruefully and she saw the lines deepen around his eyes and drive a crease down one lean cheek. He still looked young, but not as young as before. ‘That my father was a shop-keeper and my grandfather a farm labourer; that I bought my barony; that I owe my place in the world to my father’s money and your brother’s need for it.’ Despite his ruefulness he sounded comfortable with the malice. Or perhaps he had heard it so many times before that it had ceased to sting.

‘Charles is perennially in need of money,’ Elizabeth said. ‘As am I myself.’

Craven’s eyes widened at that, then he laughed, deep and appreciative. ‘Plain dealing,’ he said. ‘From a queen. That is uncommon.’

So they had both surprised the other.

Elizabeth put the cup of water down on the flagstone by her chair. ‘What I actually meant was that I had heard Prince Maurice speak highly of your talents as a soldier. He said you are loyal and courageous.’

Craven shifted, the table creaking as he leaned his weight against it. ‘Prince Maurice said I was reckless,’ he corrected gently. ‘It’s not the same.’

‘He spoke of your bravery and skill,’ Elizabeth said. ‘Take the compliment when it is offered, Lord Craven.’

He inclined his head although she was not sure whether it was simply to hide the laughter brimming in his eyes. ‘Majesty.’

There was no doubt, the man lacked deference. As the grandson of a farm labourer he should not have had a manner so easy it bordered on insolence. Yet Elizabeth found she liked it. She liked the way he did not flatter and fawn.

The silence started to settle between them. It felt comfortable. She knew she should go before the ceremony ended; before Frederick came looking for her. She had told him she wanted no part of the ceremony tonight and to be found here would invite questions. Yet still she did not move.

‘You are not one of the Order?’ she asked, gesturing towards the door to the water chamber.

He shook his head. ‘Merely a humble squire. I don’t believe—’ He broke off sharply. For the first time she sensed constraint in him.

‘You don’t believe in the principles of the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross?’ Elizabeth asked. ‘You don’t believe in a better world, in seeking universal harmony?’

His face was half-shadowed, his expression difficult to read. ‘Such ambitions seem worthy indeed,’ he said slowly, ‘but I am a simple man, Your Majesty, a soldier. How might this universal harmony be achieved?’

Ten years earlier, Elizabeth might have told him it would be through the study of the wisdom of the ancient past, through philosophy and science. She had believed in the cause then, believed that they might build a better world. But the words were hollow to her now, as was the promise that the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross had held for the future.

‘… Scrying in the waters.’ Craven’s voice drowned out the clamour of her memories. He sounded disapproving. ‘Sometimes it is better not to know what the future holds.’

Elizabeth agreed with that. If she had known her future ten years ago she was not sure she would have had the strength to go forwards towards it.

‘The Knights have powerful magic.’ She could not resist teasing him. ‘They can read secret thoughts. They can pass through locked doors. They can even turn base metal into gold.’

She thought she heard him snort. ‘As the son of a merchant, I know better than most how gold is made and it is not from base metal.’

Their eyes met. Elizabeth smiled. The silence seemed to hum gently between them, alive with something sharp and curious.

‘Are you wed, Lord Craven?’ she asked on impulse.

Craven looked surprised but no more so than Elizabeth felt. She had absolutely no idea as to why she would ask a near stranger such an impertinent question

‘No, I am not wed,’ Craven answered, after a moment. ‘There was a betrothal to the daughter of the Earl of Devonshire—’ He stopped.

A Cavendish, Elizabeth thought. He looked high indeed for the son of a merchant. But then if he was as rich as men said he would be courted on all sides for money, whilst those who sought it sniped at his common ancestry behind his back.

‘What happened?’ she said.

He shrugged. ‘I preferred soldiering.’

‘Poor woman.’ Elizabeth could not imagine being dismissed with a shrug and a careless sentence. That was not the lot of princesses. If they were not beautiful men pretended that they were. If they were fortunate enough to possess beauty, charm and wit then poets wrote sonnets to them and artists had no need to flatter them in portraits. She had lived with that truth since she was old enough to look in the mirror and know she had beauty and more to spare.

‘Soldiering and marriage don’t mix,’ Craven said bluntly.

‘But a man needs an heir to his estates,’ Elizabeth said. ‘Especially a man with a fortune as great as yours.’

‘I have two brothers,’ Craven said. His tone had eased. ‘They are my heirs.’

‘It’s not the same as having a child of your own,’ Elizabeth said. ‘Do not all men want a son to follow them?’

‘Or a daughter,’ Craven said.

‘Oh, daughters …’ Elizabeth’s wave of the hand dismissed them. ‘We are useful enough when required to serve a dynastic purpose, but it is not the same.’

His gaze came up and caught hers, hard, bright, challenging enough to make her catch her breath. ‘Do you truly believe that? That you are the lesser sex?’

She had never questioned it.

‘I heard men say,’ Craven said, ‘that King Charles believes he gets better sense from you, his sister, than from his brother-in-law.’

Insolence again. But Elizabeth was tempted into a smile.

‘Perhaps my brother is not a good judge of character,’ she said.

‘Perhaps you should value yourself more highly, Majesty.’ His gaze released hers and she found she could breathe again.

‘History demonstrates the truth.’ Craven had turned slightly away, settling the smouldering log deeper into the fire with his booted foot. ‘Your own godmother, the Queen of England, was a very great ruler.’

‘I think sometimes that she was a man,’ Elizabeth said.

Craven looked startled. Then he gave a guffaw. ‘In heart and spirit perhaps. Yet there are plenty of men lesser than she. My father admired her greatly and he was the shrewdest, hardest judge of character I know.’ He refilled the cup with water; offered it to her. Elizabeth shook her head.

‘Did not the perpetrators of the Gunpowder Treason intend for you to reign?’ Craven said. ‘They must have believed you could be Queen of England.’

‘I would have been a Catholic puppet.’ Elizabeth shuddered. ‘Reign, yes. Rule, most certainly not.’

‘And in Bohemia?’

‘Frederick was King,’ Elizabeth said. ‘I was his consort.’ She smiled at him. ‘You seek to upset the natural order of things, Lord Craven, by putting women so high.’

‘Craven!’ The air stirred, the door of the chamber swung open and Frederick strode in, his cloak of red swirling about him. In contrast to Craven, austere and dark, he looked as gaudy as a court magician. Craven straightened, bowing. Elizabeth felt odd, bereft, as though some sort of link between them had been snapped too abruptly. Craven’s attention was all on Frederick now. That was what it meant to rule, even if it was in name only. Frederick demanded and men obeyed.

‘The lion rises!’ Frederick was more animated than Elizabeth had seen him in months. Melancholy had lifted from his long, dark face. His eyes burned. Elizabeth realised that he was so wrapped up in the ceremony that he was still living it. He seemed barely to notice her presence let alone question what she was doing alone in the guardroom with his squire. He drew Charles Louis into the room too and threw an arm expansively about his heir’s shoulders.

This is our triumph, his gesture said. I will recapture our patrimony.

‘The lion rises!’ Frederick repeated. ‘We will have victory! I will re-take Heidelberg whilst the eagle falls.’ He clapped Charles Louis on the shoulder. ‘We all saw the visions in the mirror, did we not, my son? The pearl and the glass together prophesied for us as they did in times past.’

A violent shiver racked Elizabeth. The mirror and the pearl had shown Frederick a war-torn future. She remembered the flames reflected in the water, turning it the colour of blood.

‘The lion is the Swedish king’s emblem,’ she said. It was also Frederick’s heraldic device but she thought it much more likely that it would be Gustavus Adolphus whose fortunes would rise further whilst Frederick would lie where he had fallen, unwanted, ignored. He was no solider. He could not lead, let alone re-take his capital.

She caught Craven’s gaze and realised that he was thinking exactly the same thing as she. There was a warning in his eyes though; Frederick was frowning, a petulant cast to his mouth.

‘It was my emblem,’ he said, sounding like a spoilt child. ‘It was my lion we saw.’

Craven was covering Elizabeth’s tactlessness with words of congratulation.

‘Splendid news, Your Majesty,’ he said smoothly. ‘Do you plan to raise an army to join the King of Sweden’s forces immediately?’

‘Not now!’ Elizabeth said involuntarily. The room seemed cold of a sudden, a wind blowing through it, setting her shivering. Her hand strayed to her swollen belly. ‘The baby …’ she said.

Frederick’s face was a study in indecision. ‘Of course,’ he said, after a moment. ‘I must stay to see you safely delivered of the child, my dear.’ His kiss on her cheek was wet, clumsy. It felt as though his mind was already far away. ‘I will write to his Swedish Majesty and prepare the ground,’ he said. ‘There is much to plan.’

The cold inside Elizabeth intensified. She tried to tell herself it was only the shock of their fortunes changing after so many impotent years, but it felt deeper and darker than that. She knew with a sharp certainty that Frederick should not go. It was wrong, dangerous. Although she had not seen the future, she felt as though she had. She felt as though she had looked into the mirror and seen into the heart of grief and loss, seen a landscape that was terrifyingly barren.

‘The winter is no time for campaigning,’ Craven was watching her face. There was a frown between his brows. ‘Besides, there is much to do before we may leave. Troops to send for, supplies to arrange.’ He stopped, started again. ‘Your Majesty—’

Elizabeth realised that he was addressing her. The grip of the darkness released her so suddenly she almost gasped. It felt like a lifting of a curse; she was light-headed.

‘We should get you back to the palace, madam,’ Craven said. ‘You must be tired.’

‘I am quite well, thank you, Lord Craven,’ Elizabeth snapped. She was angry with him. She had thought she had seen something different in him, yet here he was fawning over Frederick like every other courtier she had known. And for all his compliments to her earlier, he spoke to her now as though she were as fragile and inconsequential as any other woman.

Immediately his expression closed down. ‘Of course, Majesty.’

‘Frederick,’ Elizabeth said. ‘If I might take your arm …’

Frederick was impatient. Elizabeth could feel it in him, in the deliberation with which he slowed his steps to help her up the spiral stair, in the tension in the muscles of his arm beneath her hand. He wanted to be back at the Wassenaer Hof, writing letters, planning a conqueror’s return to Germany. She held him back, with her pregnant belly and her woman’s fears. He was solicitous of her, masking his irritation with concern, but she had known him too long to be fooled. War was coming and that was man’s work.

Charles Louis trailed along behind them through the scented garden, scuffing his boots in the gravel, his expression sulky. He appeared to have caught none of his father’s excitement. Elizabeth could hear Craven talking to him. Their voices were too low for her to hear the words, but soon Charles Louis’ tone lifted into animation again. His quicksilver volatility was not easy to control and Elizabeth admired the way Craven had been able to distract him.

The Knights of the Rosy Cross had gone. The gardens were empty; a checkerboard of moon and shadow. Frederick was still talking, of the fall of the city of Leipzig to Gustavus Adolphus, of the destruction of his hated enemy the Spanish general Tilly, of the visions in the mirror, the lion rampant, the walls of Heidelberg rising again, of their future, suddenly so bright.

Elizabeth crushed her doubts and followed her husband into the Wassenaer Hof. The light enveloped them; for a second there was a hush and then Frederick’s blazing enthusiasm seemed to flare like a contagion through the crowds of courtiers and everyone was talking at once, laughing, lit by feverish excitement even though they did not know why they were celebrating. It was then that the cold came back to her, like the turning of a dark tide, setting her shaking so that she had to clutch the high back of one of the chairs to steady herself. The wood dug into her fingers, scoring the skin.

Frederick had not noticed. He was too busy thrusting his way through the crowd, turning to answer men’s questions. It was Craven who was watching, Craven who gestured impatiently for some of her women to come forwards to help her.

‘Lord Craven.’ Elizabeth put her hand on Craven’s arm to halt him when he too would have hurried away.

‘Madam?’ She could not read his expression.

‘You are an experienced soldier.’ Elizabeth spoke abruptly. ‘Watch over my husband for me. Keep him safe. He does not know how …’ She stopped before she betrayed herself, betrayed Frederick, too far, biting back the words on her tongue.

He does not know how to fight.

‘Majesty.’ Craven bowed, his expression still impassive.

‘Thank you,’ Elizabeth said.

He took her hand in his, kissed it. It was a courtier’s gesture, not that of a soldier. His touch was warm and very sure.

He released her, bowed again. She watched him stride away through the throng of people. He did not look back.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_5b63dfce-e0cf-5188-94ad-b2eb9fa3c907)

London, the present day.

Holly was asleep when the call came through on her mobile. She had been working all day and most of the evening on pieces for her latest collection of engraved glass and she was exhausted. She had left her little mews studio and workshop at ten o’clock, had grabbed a quick sandwich and gone to bed.

She swam up from the depths of a dream, groping for the phone that lay on the bedside table. The bright light of the screen made her wince. Normally she switched it off overnight, but she must have forgotten. She and Guy had been quarrelling over her work again. He had stomped off to the spare room, slamming the door, making a theatrical performance of his annoyance. Usually, Holly would have lain awake and fretted that they were arguing again. Just now she was too damned tired to care.

The icon on the screen was her brother’s picture. The time was two seventeen in the morning. The phone rang on and on.

Frowning, Holly pressed the green button to answer. ‘Ben? What on earth are you doing calling at this time—’

‘Aunt Holly?’ The voice at the other end of the line was already talking, high-pitched and breaking with fear, the words lost between sobs and gulps. It was not Ben but his six-year-old daughter, Florence.

‘Aunt Holly, please come! I don’t know what to do. Daddy’s disappeared and I’m on my own here. Please help me! I—’

‘Flo!’ Holly sat up, reaching for the light, her hand slipping in her haste as her niece’s terror seeped into her consciousness and set her heart pounding. ‘Flo, wait! Tell me what’s happened. Where’s Daddy? Where are you?’

‘I’m at the mill.’ Florence was crying. ‘Daddy’s been gone for hours and I don’t know where he is! Aunt Holly, I’m scared! Please come—’ The line crackled, the words breaking up.

‘Flo!’ Holly said again, urgently. ‘Flo—’ But there was nothing other than the rustle and hiss of the line and then a long, empty silence.

‘Are you mad?’

Guy had emerged from the spare room two minutes previously wearing only his crumpled boxer shorts, bleary-eyed, his hair standing on end in bad-tempered spikes.

‘You can’t shoot off to Wiltshire at this time of night,’ he said. ‘What a bloody stupid idea.’

‘It’s Oxfordshire,’ Holly said automatically. She checked the clock, pulling on her boots at the same time. The zip stuck. She wrenched it hard. Two twenty-seven. She had already wasted ten minutes.

She had rung back repeatedly but there had been no reply. The mill house, Ben and Natasha’s holiday cottage, did not have a landline and the mobile reception had always been patchy. You had to be standing in exactly the right place to get a signal.

‘Have you tried Tasha’s mobile?’ Guy asked.

‘She’s working abroad somewhere.’ Ben had told her but Holly couldn’t remember exactly where. ‘I left her a message.’ Tasha had a high-powered job with a TV travel show and was frequently away.

‘Ben’s probably turned up again by now.’ Guy sat down next to her on the bed, putting what she supposed was meant to be a reassuring hand on her arm. ‘Look, Hol, don’t panic. I mean maybe the kid got it wrong—’

‘Her name’s Florence,’ Holly said tightly. It irritated the hell out of her that Guy seldom remembered any of her family or friends’ names, mostly because he didn’t try. ‘She sounded terrified,’ she said. ‘What do you want me to do?’ She swung around fiercely on him. ‘Leave her there alone?’

‘Like I said, Ben will have turned up by now.’ Guy smothered a yawn. ‘He probably crept out to meet up with some tart, thinking the kid was asleep and wouldn’t notice. I know that’s what I’d be doing if I was married to that hard-faced bitch.’

‘I daresay,’ Holly said, not troubling to hide the edge in her voice. ‘But Ben’s not like you. He—’ She stopped. ‘Ben would never leave Flo on her own,’ she said.

She stood up. The terrified pounding of her heart had settled to an anxious flutter now, but urgency still beat through her. Two thirty. It would take her an hour and a half to get to Ashdown if there was no traffic. An hour and a half when Flo would be alone and fearful. The terror Holly had felt earlier tightened in her gut. Where the hell was Ben? And why had he not taken his phone with him wherever he had gone? Why leave it in the house?

She racked her brains to remember their last phone conversation. He’d told her that he and Florence were heading to the mill for a long weekend. He’d taken a few days off from his surgery in Bristol. It was the early May Bank Holiday.

‘I’m doing some family history research,’ he’d said, and Holly had laughed, thinking he must be joking, because history of the family or any other sort had never remotely interested her brother before.

She was wasting time.

‘Have you seen my car keys?’ she asked.

‘No.’ Guy followed her into the living room, blinking as she snapped on the main light and flooded the space with brightness.

‘Jesus,’ he said irritably, ‘Now I’m wide awake. You’re determined to ruin my night.’

‘I thought,’ Holly said, ‘that you might come with me.’

The genuine surprise on his face told her everything she needed to know.

‘Why go at all?’ Guy said gruffly, turning away. ‘I still don’t get it. Just call the police, or a neighbour to go over and check it out. Isn’t there some old friend of yours who lives near there? Fiona? Freda?’

‘Fran,’ Holly said. She grabbed her keys off the table. ‘Fran and Iain are away for a couple of days,’ she said. ‘And the reason I’m going—’ she stalked up to him, ‘is because my six-year-old niece is alone and terrified and she called me for help. Do you get it now? She’s a child. She’s frightened. And you’re suggesting I go back to bed and forget about it?’

She picked up her bag, checking for her purse, phone, and tablet. The rattle of the keys had brought Bonnie, her Labrador retriever, in from her basket in the kitchen. She looked wide-awake, feathery tail wagging.

‘No, Bon Bon,’ Holly said. ‘You’re staying—’ She stopped; looked at Guy. He’d forget to feed her, walk her. And anyway, it was comforting to have Bonnie with her. She grabbed Bonnie’s food from the kitchen cupboard and looped her lead over her arm.

‘Right,’ she said. ‘Let’s go.’ In the doorway she paused. ‘Shall I call you when I know what’s happened?’ she asked Guy.

He was already disappearing into the bedroom, reclaiming the space she had left. ‘Oh, sure,’ he said, and Holly knew she would not.

Holly rang Ben’s number every couple of minutes but there was never any reply, only the repeated click of the voicemail telling her that Ben was unavailable and that she should leave a message. Eventually that stopped, too. There was no return call from Tasha, either. Holly wondered about calling her grandparents in Oxford. They were much closer to Ashdown Mill and to Florence than she was, though the car was eating up the miles of empty road. The mesmerising slide of the streetlights was left behind and there was nothing but darkness about her now as she drove steadily west.

In the end she decided not to call Hester and John. She didn’t want to give either of them a heart attack, especially when there might be no reason to worry. Even though she was furious with Guy, she knew he might be right. Ben could have returned by now and Florence might be fast asleep again and, with the adaptability of a child, have forgotten that she had even called for help.

Holly had not wanted to call the police for lots of reasons ranging from the practical – that it could be a false alarm – to the less morally justifiable one of not wanting to cause problems for her brother. She and Ben had always protected each other, drawing closer than close after their parents had been killed in a car crash when Holly was eleven and Ben thirteen. They had looked out for each other with a fierce loyalty that had remained fundamentally unchanged over the years. Their understanding of each other was relaxed and easy these days, but just as close, just as deep. Or so Holly had thought before this had happened, leaving her wondering what the hell her brother was up to.

She pushed away the unwelcome suspicion that there might be things about Ben that she neither knew nor understood. Guy had planted the seed of doubt, but she crushed it angrily; she did know that Ben and Tasha were going through a bad patch but she could not imagine Ben being unfaithful. He simply wasn’t the type. Even less could she imagine him neglecting his child. There had to be some other reason for his disappearance, if he had actually vanished.

But there was Florence, who was only six, and she had been alone and terrified. So it was an easy decision in the end. Holly had called the local police, keeping her explanation as short and factual as possible, sounding far calmer than she had felt. If anything happened to Florence and she had not done her best to help, she would have failed Ben as well as her niece.

The sign for Hungerford flashed past, surprising her. She was at the turn already. It was twelve minutes to four. Ahead of her the sky was inky dark, but in her rear-view mirror she thought she could see the first faint light of a spring dawn. Perhaps, though, that was wishful thinking. The truth was that she didn’t feel comfortable in the countryside. She was a city girl through and through, growing up first in Manchester and then in Oxford after her parents had died, moving to London to go to art college and staying there ever since. London was a good place for her glass-engraving business. She had a little gallery and shop in the mews adjoining the flat, and a sizeable clientele.

At the motorway roundabout she turned right towards Wantage then left for Lambourn. She knew the route quite well, but the road looked deceptively different when the only detail she could see was picked out in her headlights. There were curves and turns and shadowed hollows she did not recognise. She was heading deep into the countryside now. A few isolated cottages flashed past, shuttered and dark. She took the right turn for Lambourn and plunged down into the valley, the car’s lights illuminating the white-painted wooden palings of the racehorse gallops that ran beside the road. The little town was silent as she wove her way through the narrow streets. As the stables and houses fell away and the fields rolled back in, Holly had the same feeling she always had on approaching Ashdown; a sense of expectancy she had never quite understood, a feeling of falling back through time as the dark road opened up before her and the hills swept away to her right, bleak and empty, crowned with a weathercock.

She and Ben had raced up to the top of Weathercock Hill as children, throwing themselves down panting in the springy grass at the top, staring up at the weather vane as it pierced the blue of the sky high above. The whole place had felt enchanted.

Ben. Her chest tightened again with anxiety. She was almost there. What would she find?

The lights picked out a huge advertising hoarding by the side of the road. The words flashed past before she could make out more than the first few:

‘Ashdown Park, a select development of historic building conversions …’

Trees pressed close now to the left, rank upon rank of them like an army in battle order. There was a moment when the endless wood fell back and through the gap in the trees Holly thought she saw a gleam of white; a house standing tall and foursquare with the moonlight reflecting off the glass in the cupola and silvering the ball on the roof. A moment later and the vision had gone. The woods closed ranks, thick and forbidding, swallowing the house in darkness.

The left turn took her by surprise and she almost missed it even though she had come this way so many times before. She bumped along the single-track road, past a bus stop standing beside the remains of the crumbling estate wall. The old coach yard was off to the left; it seemed that this was where the majority of the building work was taking place, behind the high brick-and-sarsen wall. Even in the dark Holly could see the grass verge churned up by heavy machinery and the crouching shadow of a mechanical digger. There was another sign here, a discreet one in cream with green lettering, giving the name of the developers and directing all deliveries back to the site office on the main road.

The lane turned left again, running behind the village now, climbing towards the top of the hill. A driveway on the right, a white-painted gatepost flaking to wood beneath and a five-barred gate wedged open by the grasses and dandelions growing through it.

Ashdown Mill.

She stopped on the gravel circle in front of the water mill and turned off the engine. Bonnie gave a little, excited bark. Holly could hear the thud of her tail as the dog waited impatiently to jump out of the back. There were two other cars on the gravel, a small saloon car and Ben’s four-by-four. The exhaustion and relief hit Holly simultaneously. Her shoulders ached with tension. If Ben was here and it had all been a big misunderstanding she would kill him.

She opened her door and slid out, her legs stiff, an ache low in her back. Outside the car the air had a pre-dawn chill to it. The daylight was growing slowly, trickling through the trees and washing away the moon.

Bonnie was running around with her nose to the ground, released from the captivity of the car, a bounce in her step. She chased around the side of the whitewashed mill and disappeared from view. Holly slammed the car door and hurried after her, pushing open the little gate in the picket fence and running up the uneven stone path to the door, calling for Bonnie as she went.

All the lights were on inside the mill. The door opened before she reached it.

‘Ben!’ she burst out. ‘What the hell—’

‘Miss Ansell?’ A uniformed policewoman stood there. ‘I’m PC Marilyn Caldwell. We spoke earlier.’ She had kind eyes in a pale face pinched with tiredness, and there was something in her voice that warned Holly of bad news. Her heart started to thump erratically again. A headache gripped her temples.

She noticed that one of the door panels was splintered and broken.

‘We had to break it to get in.’ There was a note of apology in PC Caldwell’s voice. ‘The handle is too high for Florence to reach.’

‘Yes.’ Holly remembered that the door had a heavy, old-fashioned iron latch. So Ben had not been there when the police had arrived and there was no sign of him now. Her apprehension was edged with something deeper and more visceral now.

She fought back the terror; breathed deeply.

‘Is Florence OK?’

‘She’s fine.’ Marilyn Caldwell laid a reassuring hand on Holly’s arm. She shifted a little so that Holly could see through into the mill’s long living room. Florence was sitting on the sofa next to another female police officer. They were reading together, although Florence’s eyes were droopy with tiredness and puffy with her earlier tears.

Holly’s heart turned over to see her. She took an involuntary step forwards. ‘Can I go to her, please—’

‘Just a moment.’ The note in PC Caldwell’s voice stopped her. ‘I’m afraid we haven’t found your brother, Miss Ansell.’ She was looking at Holly with forensic detachment now. ‘We’ve searched the house and the woods in the close vicinity, also all the roads nearby. There’s no sign.’

Holly was taken aback. Fear fluttered beneath her breastbone again. This was not right.

‘Is that Dr Ansell’s car outside?’ PC Caldwell asked.

‘Yes.’ Holly rubbed her tired eyes. ‘He can’t have driven anywhere.’

‘Perhaps a friend came to pick him up,’ PC Caldwell suggested. ‘Or he walked to meet someone.’

‘In the middle of the night?’ Holly said. ‘Without his phone?’

PC Caldwell’s expression hardened. ‘It’s hardly unknown, Miss Ansell. I imagine he thought Florence was asleep and slipped out. Perhaps he’s lost track of the time.’

‘That would be ridiculously irresponsible.’ Holly felt furious and tried to rein herself in. She was tired, worried. She had driven a long way. She needed to calm down. Evidently PC Caldwell thought so too.

‘We fully expect Dr Ansell to turn up in the morning,’ she said coldly. ‘When he does, please could you let us know? We’d like to have a word.’

‘You’ll have to stand in line,’ Holly said. Then: ‘I’m sorry. Yes, of course. But …’ Doubt and fear stirred within her again. The emotions were nebulous but strong. Her instinct told her that Ben had not simply walked out.

‘He left his phone,’ she said. ‘And all his stuff’s scattered about. It doesn’t look as though he planned to go out.’

PC Caldwell was already signalling discreetly to her colleague that it was time to leave. She seemed completely uninterested.

‘We’ve traced Mrs Ansell,’ she said. ‘She’s on her way back from Spain but might not make it until tomorrow night. Apparently she’s been,’ she checked her note pad, ‘helicopter skiing in the Pyrenees?’ She sounded doubtful.

‘Very probably,’ Holly said dryly. ‘Tasha works for a travel show – Extreme Pleasures?’

‘Oh yes!’ Marilyn Caldwell’s face broke into a smile. ‘Wow! Natasha Ansell. Of course! How exciting. Well—’ She stopped, realising that the situation did not really merit celebrity chit-chat. ‘We’ll be back tomorrow,’ she said. She turned on an afterthought. ‘Do you know what your brother was doing here, Miss Ansell?’

‘It’s his holiday cottage,’ Holly said. ‘We co-own it.’ She rubbed her eyes again, feeling the grittiness of them. Suddenly she was so tired she wanted to sleep where she was standing. ‘He was down here with Flo whilst Tasha was away working,’ she said. ‘He said he was doing some research. Family history. It’s quiet here. A good place to think.’

PC Caldwell nodded. ‘Right,’ she said. Holly could see her wondering how on earth someone as glamorous as Tasha could be mixed up in a messy situation like this with a man whose idea of fun was family history research.

‘Well,’ the policewoman said. ‘We’ll call back to chat to Mrs Ansell tomorrow.’

I bet you will, Holly thought.

She felt utterly furious, livid with PC Caldwell for being more interested in Tasha’s fame than in Ben’s disappearance, angry that Tasha hadn’t even bothered to ring her to make sure it was OK for her to look after Flo until she got back, and most annoyed of all with Ben for vanishing without a word. The anger helped her, because behind it the fear still lurked, the sense that something was wrong and out of kilter, that Ben would never voluntarily disappear leaving his daughter alone.

Bonnie, picking up on Holly’s mood, made a soft whickering noise and Holly saw Florence look up from the storybook. Her niece’s eyes lit up to see them and she scrambled from the sofa.

‘Aunt Holly!’ Florence rushed towards her, arms outstretched. ‘You came!’ Holly scooped her up automatically, feeling the softness of Florence’s cheek pressed against hers, inhaling the scent of soap and shampoo. Florence clung like a limpet, her hot tears scalding Holly’s neck. Holly could feel her niece’s fear and desolation and her heart ached for her. Security was such a fragile thing when you were a child. She understood that better than most.

‘Hello Flo,’ she said gently. ‘Of course I came. I’ll always come when you call me. You know that.’

‘Where’s Daddy?’ Florence was wailing. ‘Why has he gone away?’

‘I don’t know,’ Holly said, hugging her tighter. ‘He’ll be back soon. I’m sure of it.’ She wished she were.

Later, when Florence had finally fallen into an exhausted sleep, Holly carried her niece upstairs in the pale light of the May dawn and put her gently on the big double bed in the main bedroom with her toy rabbit cuddled up in her arms. Then she went over to the window seat and leaning her head back against the panelled wall, closed her eyes for a moment.

Although as children she and Ben had shared the smaller bedroom next door, this was the room she had been drawn to every time. She loved the way the light poured in from the high windows.

So early, the room was still full of morning shadow. Ben’s stuff was scattered all around; a shirt discarded over the arm of the chair, his watch on the chest of drawers, the bed half-made. It looked as though he had just stepped out for a second and would be back at any moment and that disturbed Holly more than it reassured her. This was all so out of character.

Nostalgia and a feeling almost like grief caught her sharply in her chest. She remembered how, as children, she and Ben would imagine the bed as a flying carpet taking them to faraway lands. They had told each other stories more spectacular, adventurous and exciting than any they had read in books. It had been magical. There had even been a little compartment hidden beneath the cushion on the window seat where they would leave each other secret messages …

The breath stopped in her throat. Softly, so as not to wake Florence, Holly slipped off the seat and lifted the cushion up. The little brass handle she remembered was still there. She pulled. Nothing happened. The box lid seemed wedged shut. She tugged a little harder.

The wood lifted with a scrape that she was afraid for a moment would wake Florence, but the child did not stir. Holly knelt down and peered inside.

There was nothing there except for a receipt for some dry cleaning, a dead spider and a misshapen yellow pebble.

Holly felt an absurd sense of disappointment and loss. What had she imagined – that Ben would have left her a secret message to explain where he had gone? No matter how wrong it felt to her that he had simply vanished into thin air, she had to believe that the police were correct. Come morning Ben would walk in full of anxiety for Flo and apologies and relief, explaining … But here Holly’s imagination failed her. She could not think of a single reason why he would do what he had done.

Eventually, when she felt calm enough, she went and curled up next to Florence on the big double bed. She didn’t sleep but lay listening to Florence’s breathing and felt a little bit comforted. After a while she fell into an uneasy doze, Bonnie resting across her feet.

She was woken some time later by an insistent ringing sound. For a moment she felt happy before the memory of what had happened rushed in, swamping her consciousness. She stumbled from the bed and down the stairs, making a grab for her bag and the phone, wondering if it was Guy calling to see what had happened.

But it wasn’t her mobile that was ringing. She found Ben’s phone halfway down the side of the sofa and pressed the button to answer the call.

‘Dr Ansell?’ It was a voice she didn’t recognise, male, slightly accented, sounding pleasant and business-like. ‘This is Espen Shurmer. My apologies for calling you so early but I wanted to catch you to confirm our meeting on Friday—’

‘This isn’t Ben,’ Holly said quickly. ‘I’m his sister.’

There was a pause at the other end. ‘My apologies again.’ The man sounded faintly amused. ‘If you would be so good as to pass me over to Dr Ansell.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Holly said. ‘He’s not here. I …’ She could feel herself stuttering, still half-asleep. She wasn’t sure why she had answered the call and now she didn’t know what to say. ‘I’m afraid he’s disappeared,’ she blurted out.

This time the silence at the other end of the line was more prolonged. Just when she thought Espen Shurmer had hung up, and was feeling grateful for it, he spoke again.

‘Disappeared? As in you do not know where he is?’ He sounded genuinely interested.

‘Yes,’ Holly said. ‘Last night.’ She was not sure why she was telling this man so much when he was probably no more than a business acquaintance of Ben’s. ‘So I’m afraid I don’t know if he’ll be able to make your meeting … I mean, if he comes back I’ll tell him, but I can’t guarantee he’ll be there …’ She let her voice trail away, feeling an absolute fool.

‘Miss Ansell,’ the man at the other end said, ‘Forgive me for not introducing myself properly. My name is Espen Shurmer and I am a collector of seventeenth-century artefacts, paintings, glass, jewellery …’ He paused. ‘I had arranged to meet your brother on Friday night at 7.30pm after a private view at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. He contacted me a couple of weeks ago to request the meeting.’

‘Oh.’ Holly was at a loss. ‘Well, I’m sorry I can’t be of more help, Mr Shurmer, but I have no idea what Ben wanted to talk to you about. Actually I’m very surprised he got in touch. Art isn’t really his thing …’ She stopped again, realising she was still babbling even if what she was saying was true. Ben had zero interest in the arts. He had always supported her engraving career and had even bought a couple of her glass paperweights for his surgery, but she had known it had only been because she had made them herself. She had loved him for it but she was under no illusions about his interest in culture.

‘I know what it was that your brother wished to discuss, Miss Ansell,’ Espen Shurmer said. ‘He wanted some information on a certain pearl, a legendary stone of great worth.’

Holly sat down abruptly. ‘A … pearl?’ She said. She thought she had misheard. ‘As in a piece of jewellery? Are you sure? I mean …’ It was possible that Ben might have been buying a gift for Natasha, but she was certain he would have bought a modern piece rather than approaching an antiques collector. Such an idea would never even have crossed his mind.

‘I think we should meet to discuss this,’ the man said, after a moment. ‘It is most important. If your brother is unable to keep the appointment, would you be able to come in his place, Miss Ansell? I should be extremely grateful.’

Holly hadn’t even thought about what would happen beyond the next few hours, let alone on Friday. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said. ‘I’m sorry, Mr Shurmer, but Ben will probably be back by then and anyway, this is nothing to do with me.’

‘Seven thirty at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford,’ Shurmer said, cutting in so smoothly she barely noticed the interruption. ‘I should be greatly honoured if you choose to be there, Miss Ansell,’ he added with old-fashioned courtesy.

The line clicked as the call went dead.

Holly put the phone down slowly, found her bag and grabbed her tablet. She typed in the name Espen Shurmer and the time, the date and the name of the Ashmolean Museum. The information came up at once – a lecture and private view of portraits and artefacts from the court in exile of Elizabeth, the Winter Queen, sister of King Charles I, which preceded a major new exhibition starting at the end of May. Espen Shurmer, she read, was a Dutch collector of 17

-century painting and glass, and he had donated a number of items to the museum.

She felt a pang of regret as she closed the tablet. She would have loved to see an exhibition of seventeenth-century artefacts and talk to a renowned expert. But there would be no need. Ben would be back soon, she was sure of it. She had to be sure because there was Flo to console and there were her own fears to fight. The longer Ben was absent, the more those shadows grew like monsters, the fear that Ben would never come back and she would be alone again, totally alone this time, like they had been after their parents had died, only so much worse …

She fought back the panic. It was important to keep busy. She needed to make breakfast for Flo, then they could both take Bonnie for a walk, and by then Ben would be home …

But Ben had not come back by lunchtime when Holly drove down to the deli to fetch sandwiches, nor was he back by three when they came back from another walk in the woods with Bonnie. All day Holly had felt her anxiety rising and squashed it down relentlessly, but it grew inside her, filling the empty spaces, filling her mind so she found it almost impossible to concentrate on anything. When she heard a car coming up the track towards the mill she had to restrain herself from running outside to see if it was Ben.

‘It’s Mummy!’ Flo had none of Holly’s reticence and had bounded up from the painting they had been doing to rush out of the door, Bonnie at her heels. Holly followed them more slowly. She and her sister-in-law had always had a brittle relationship. Ben had been a link between them, but now he was missing, and Holly felt suddenly wary.

Tasha, looking as elegant as though she was stepping onto the catwalk, slammed the door of her little red sports car and came hurrying across the gravel on her vertiginously high heels.

‘What the fuck is all this about?’ She demanded without preamble, meeting Holly by the gate. ‘I’ve had to come all the way back from Spain! Where is he, the stupid bastard?’

Holly blinked. Tasha seemed to notice Flo for the first time and bent down to pick her up. ‘Hello darling.’ She held Flo and her sticky painting fingers a little bit away from her. ‘Don’t worry, sweetie, I’m here now.’ She gave Bonnie a vertical pat, designed as much to push her away as greet her. Tasha was not a pet person.

‘Let’s go inside,’ Holly said.

‘I don’t want to stay,’ Tasha said, taking off her sunglasses and fixing Holly with her big blue eyes. ‘I’m going home to Bristol. I’m not hanging around here waiting for Ben to turn up when he feels like it. Have you got Flo’s bag?’

‘It’s not packed,’ Holly said coldly, ‘since you didn’t let me know you were coming.’ She was too exhausted for tact. She and Tasha had never been close; she had tried to like her sister-in-law but it had proved very difficult.

‘Sorry.’ To Holly’s surprise Tasha seemed to deflate all of a sudden like a pricked balloon. ‘I really do appreciate you coming down, Holly, and looking after Flo. But I’m just so bloody angry! It’s just not on for Ben simply to walk out on all his commitments—’

‘Wait.’ Holly put a hand on Tasha’s arm. ‘What do you mean? Surely you don’t think he’s just upped and gone?’

‘That’s exactly what I think,’ Tasha said fiercely, scrubbing at her eyes. She pushed the dark glasses firmly back down on her nose. ‘He was spending all his spare time down here. He’s probably got another woman, for all I know.’

‘He was doing family history research,’ Holly protested.

Her sister-in-law gave a look of such searing scorn that she blushed.

‘Yeah, and I’m Marilyn Monroe,’ Tasha said.

‘I don’t believe it!’ Holly said. She was so outraged she forgot that Flo was listening, taking it all in with her blue eyes wide, so like her mother’s. ‘Hell, Tasha, you know Ben would never do a thing like that! He’d certainly never leave Flo alone! And besides, where would he go? He’d never disappear without telling anyone!’

‘You mean you think he’d never vanish without telling you,’ Tasha said, a hint of pity in her voice now that set Holly’s teeth on edge. ‘Oh Holly …’ She shook her head. ‘I know you think the two of you are really close but you don’t know Ben that well. Trust me.’ She took Flo’s hand. ‘Come on, sweetie, let’s go and get your stuff.’

Holly watched them walk up the path together and into the mill. Desolation swamped her, along with a terrible fear that her sister-in-law might be right. Secretly she had always believed she knew Ben better than anyone, even his wife. Had Ben hidden the truth of deeper fissures in his marriage? Holly could not believe it.

The sun, sparkling on the millpond, dazzled her eyes. Suddenly she felt close to tears. It felt as though she was trapped in a world where nothing was what it seemed and she was the only one trying to keep a tenuous faith. Beside her, Bonnie stood tense, her head tilted to one side, picking up on her mood once again.

‘Come on, Bon Bon,’ Holly said, suddenly fierce. ‘I know this isn’t right. I don’t care what everyone else says.’