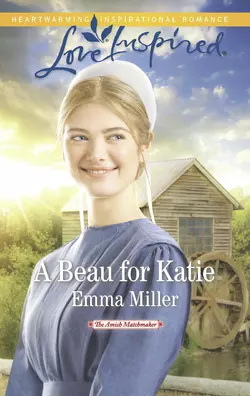

A Beau For Katie

Emma Miller

The Housekeeper's Surprise MatchAgreeing to work for two weeks as a housekeeper to help a family in need, seems like a good idea to Katie Byler. But when Katie sees the handsome, young—and single—Freeman Kemp for the first time, she wonders what she’s gotten herself into. Freeman may be considered a catch, but the stubborn young man is driving strong-willed Katie to distraction. When the two of them decide to play matchmaker for Freeman's elderly uncle though, their feud takes a different turn. The spark between them is strong, but can Katie and Freeman reach common ground to find their happily-ever-after?The Amish Matchmaker: Bringing love to Seven Poplars—one couple at a time!

The Housekeeper’s Surprise Match

Agreeing to work for two weeks as a housekeeper to help a family in need seems like a good idea to Katie Byler. But when Katie sees the handsome, young—and single—Freeman Kemp for the first time, she wonders what she’s gotten herself into. Freeman may be considered a catch, but the stubborn young man is driving strong-willed Katie to distraction. When the two of them decide to play matchmaker for Freeman’s elderly uncle, though, their feud takes a different turn. The spark between them is strong, but can Katie and Freeman reach common ground to find their happily-ever-after?

“Maybe you could find your razor. You’re badly in need of a shave.”

She hesitated, then continued, “I could do it for you, if you like. My brother broke two fingers on his right hand once and I—”

“No. Let me do it by myself.”

She went to change the sheets and returned to the bathroom to find him still sitting at the sink. There were uneven patches of beard on his cheeks and a trickle of blood down his chin. Wordlessly, he handed the razor to her, grimaced and squeezed his eyes shut.

She’d thought that shaving Freeman would be no different than shaving her brothers, but as she stood there looking at him, she realized it was.

Her pulse quickened, and she felt a warm flush beneath her skin. Shaving Freeman was more intimate than she’d supposed it would be and she was thankful that his dark eyes were closed.

“All done.”

“Thank you.”

“You look a lot better.” And he did, more than better. He had the kind of good looks that cautious mothers warned their daughters against.

EMMA MILLER lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

A Beau for Katie

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

He who finds a wife finds what is good

and receives favor from the Lord.

—Proverbs 18:22

Contents

Cover (#u6cf5fa87-df07-5230-9f64-f8bfa2562dcf)

Back Cover Text (#u81bfa62d-d69d-506c-983c-c9f1f47fde04)

Introduction (#ua57883fe-e5e9-5a2b-9e66-092a3099e950)

About the Author (#ue1c55aa5-8a1d-51d9-983c-9405cf66debb)

Title Page (#u48ace9e4-0542-5edd-8e8d-4be11974a10e)

Bible Verse (#u4d6c7e13-efe2-5655-b3af-2a26e39259e0)

Chapter One (#ulink_712559b7-2f0c-5bff-a067-e56b1f6ea450)

Chapter Two (#ulink_591c2fc0-aacc-54a2-88cc-d37ce154c9dc)

Chapter Three (#ulink_ccdb4b36-05c6-5ed9-9b3d-6cac7a527189)

Chapter Four (#ulink_49446a24-f372-5fb1-ac7c-3c905b6114c8)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_5a0f74d4-0888-5f33-a72f-c690da1693a9)

Millside Amish Community,

Kent County, Delaware

July

Suddenly apprehensive, Katie Byler reined in her horse on the bridge, easing the buggy to a standstill. Next to the dam was the feed-and-grain mill, a business that had been there since colonial times and was one of the few water-powered mills left in Delaware. On the far side was the millpond, a large stretch of water surrounded for the most part by trees. Out in the middle of the pond, a pair of Canada geese bobbed, and overhead, iridescent dragonflies and some sort of birds swooped and fluttered. It was a beautiful sight with the morning light sparkling on the blue-green water, and on any other day, Katie would have taken delight in it. Today, however, she had serious concerns on her mind.

She may have let Sara Yoder talk her into something she’d regret.

Behind her, Sara, the county’s only Amish matchmaker, stopped her mule and climbed down from her buggy. “What’s wrong?” She came to stand beside Katie’s cart. “Why did you stop?” Sara raised her voice to be heard above the rush of water under the bridge. “We’re blocking traffic.”

Katie made a show of looking in both directions, up and down the road. It was a private lane, and anyone using it would be coming to or leaving the mill. At the moment, the parking lot in front of the mill had only one car and it was parked, with no one inside. The lane behind her was empty. “Ne, I don’t think so,” she answered in Deitsch, the German dialect that the Amish used among themselves.

“Don’t tell me you’re having second thoughts.” Sara folded her arms over her bosom and gave Katie the look from beneath her black bonnet, the look that had given Sara a reputation for taking no nonsense. “You said you would accept the job, and I gave Jehu my word that you would start this morning.”

“I know I agreed to it, but now...” She met Sara’s strong-minded attitude with her own. She liked the middle-aged woman, admired her really. Sara had gumption. She was an independent woman in a traditional society where most widows depended on fathers or sons to provide for them.

Katie narrowed her gaze on the matchmaker. Sara didn’t have the pale Germanic skin of most Amish; she was half African American, with a coffee-colored complexion and dark, textured hair. Katie knew Sara’s heritage because she’d asked her the first time they’d met. “How do I know that you’re not trying to match me with Freeman Kemp?” she asked. “Because if you are, I’ll tell you right off, it’s a hopeless cause. He’s one man I’d never consider for a husband.”

Katie and Freeman had clashed when they were volunteering as helpers at a wedding the previous November. She’d been in charge of one of the work parties, and she’d made a suggestion about the way the men were loading chairs into the church wagon. Freeman had taken affront and had behaved immaturely, stalking off to sulk while the other men continued to work. It hadn’t been an argument exactly, but it was clear that although her way was far more sensible, Freeman was offended by being told what to do by a woman. Katie couldn’t have cared less. Growing up with older brothers, she’d learned early to speak up for herself, and if Freeman disliked her because of her refusal to be submissive, that was his problem.

Sara arched one dark brow and sighed. “Poor Freeman is laid up in bed with a broken femur. He hasn’t asked me to find him a wife, and if he did discover he needed one this week, I doubt you’re in any danger of him running you down and dragging you before the bishop.” She shrugged. “It’s because of his injury that he needs a housekeeper. You have no need for concern about your reputation, if that’s your worry. Freeman’s grandmother lives right next to him in the little house. She’s in and out of Freeman’s place all day long, and she’ll provide the chaperoning the elders expect.”

“That’s not what worries me,” Katie muttered. Sara was just like her: she never minced words. “I just don’t want any misunderstandings. Freeman Kemp is one of those men all the single girls moon over. You know, him being so good-looking and so well-to-do.” She nodded in the direction of the mill and surrounding property, the farmhouse and little grossmama haus where his grandmother lived. “I wouldn’t want him to think that I’m one of them.”

Sara laid a small brown hand on the dashboard of Katie’s buggy. “If you’re intimidated by Freeman, I’m sure I can get someone else to take the job. I wouldn’t want to force you to do anything that made you feel uncomfortable.”

“I’m not intimidated by him.” Katie sat up a little straighter, tightened the reins in her hands and gazed ahead at the farmhouse. “Certainly not.” She was probably making too much of a small incident. Freeman had made a remark about her bossiness to a friend of her brother’s not long after the wedding incident, but he’d probably forgotten all about the unpleasantness by now.

“Good.” Sara patted Katie’s knee. “Then there’s no reason to keep them waiting any longer. The sooner you start, the sooner you can put the house in order.”

* * *

“Well, Uncle Jehu, if you hired a housekeeper without my say-so, you can just un-hire her.” Freeman lay propped up on pillows in a daybed against the kitchen wall. “We need a strange woman rattling around here about as much as I need another broken leg.”

“Now, boy, calm yourself,” the older man said quietly in Deitsch. His arthritis-gnarled fingers moved, twisting a cord in a continuous game of cat’s cradle, forming one shape after another. “It’s only temporary. A younger pair of willing hands might bring some order to this mess we call a house.”

Freeman glanced away. His uncle meant no insult. Calling him boy was a term of affection, but Freeman felt it was demeaning sometimes. He was thirty-five years old and he’d been running the family mill since he was twenty. Everyone in their Amish community accepted him as a grown man and head of this house, but because he’d never married, his uncle still thought of him as a stripling.

Uncle Jehu gestured with his chin in the general direction of the kitchen sink where Freeman’s grandmother stood washing their breakfast dishes. “No insult meant to you, Ivy.”

Freeman’s paternal grandmother bobbed her head in agreement. “None taken. I said from the start when I came to live here I wouldn’t be anyone’s housekeeper. I’ve plenty of chores to keep me busy at my own place, not to mention waiting on customers at the mill. And what with my arthritis, I can’t do it all.” She eyed her grandson, sitting up in the bed, his leg cast from ankle to upper thigh, resting in a cradle of homemade quilts. “Jehu’s right, Freeman. This house can stand a good cleaning. There are more cobwebs in this kitchen than the hayloft.”

“You think I don’t see them?” Freeman swallowed his rising impatience and forced himself not to raise his voice. “As soon as I get this cast off, I’ll redd it all up. I did fine before I broke my leg, didn’t I?” He still felt like a fool, breaking his leg the way he did. Anyone who’d been raised around farm animals should have known to take care and get a friend to lend a hand. He’d just been too sure of himself, and his own pride had gotten the better of him.

Ivy shook a soapy finger at him. “Stop fussing and make the best of it.” She dipped a coffee cup in rinse water and stacked it in the drainer. “Maybe the Lord put this hurdle in your path to make you take stock of your own shortcomings. You’ve a good heart. You’re always eager to help others, but you’ve never had the grace to accept help when you need it.” She drew her mouth into a tight purse and nodded. “Jehu’s already arranged the girl’s hire for two weeks.”

“And she’s coming this morning,” his uncle said as he twisted the string into a particularly intricate pattern. “So accept it gracefully and make her welcome.”

A motor vehicle horn beeped from the parking lot.

“Another customer,” Grossmama declared, quickly drying her hands on a dishtowel. “We’re going to have another busy one at the mill. Didn’t I say that buying those muslin bags with Kemp’s printed on them and advertising would pay off? The Englishers drive from all over the state to get our stone-ground bread flour.” Retrieving her black bonnet from the table, she put it on over her prayer kapp, and bustled out the door.

“With a housekeeper, we might get something to eat other than oatmeal,” Uncle Jehu offered his nephew by way of consolation.

“I heard that!” his grandmother called back through the screen door. “Nothing wrong with oatmeal. I eat it every day, and I’ve never been sick a day in my life.”

“Never sick a day in her life,” his uncle repeated under his breath.

Freeman couldn’t help chuckling. He was as tired of oatmeal as Uncle Jehu. There was nothing wrong with his grandmother’s oatmeal. It was tasty and filling, but after eating it every morning since he was discharged from the hospital, he longed for pork sausage, bacon, over-easy eggs and home fries. And he was tired of her chicken noodle soup that they ate for dinner and supper most days, unless a neighbor was kind enough to drop by with a meal. “A few more days and I’ll be up and about,” he told his uncle. “I can take over the cooking, like I used to.”

His uncle scoffed. “Unless you want to end up back in the hospital, you’ll follow doctor’s orders. A broken thighbone’s a serious thing. In the meantime, the house is getting away from us, and so is the laundry.” He shook his head. “It’s a good thing I’m blind. Otherwise I would have been ashamed to go to church in a shirt that’s been worn three Sundays and not been washed and ironed.”

“No. Housekeeper,” Freeman repeated firmly, emphasizing each syllable.

Jehu’s terrier, Tip, leaped off the bed and ran barking to the door.

“Too late.” Uncle Jehu broke into a self-satisfied grin. “Sounds like a buggy coming. Must be Sara Yoder and her girl now.”

“You should send her back. We don’t need her,” Freeman protested, but only half-heartedly. He knew the battle was lost. He wouldn’t hurt the poor girl’s feelings by sending her away now that she was here. He would have to make the best of it.

“Ne. You heard Ivy. I already hired her.” Jehu didn’t sound a bit repentant; in fact, he seemed quite pleased with himself.

Freeman had a lot of respect for his mother’s oldest brother, and more than that, he loved him. It was a pity when a man couldn’t be master in his own house. Freeman was used to having his grandmother living in the grossmama haus. She’d been part of the household even before his parents died, and the two of them got along as easily as chicken and dumplings. But Uncle Jehu had only come to live with him the previous summer and didn’t always seem to understand that Freeman liked to do things his own way. Caring for his uncle was his responsibility, and he was glad to do it, but he didn’t want to have decisions made for him as if he were still a child.

“Fine,” Freeman muttered, feeling frustrated that he couldn’t even get up to greet Sara and the housekeeper properly. It was demeaning to be laid out in a bed like this. But after a complication the previous week, his surgeon had been adamant. Freeman needed to keep his leg elevated at all times for another three days. “Who is this housekeeper? Do I know her?”

“She’s from Apple Valley church district, but the two of you have probably crossed paths somewhere.”

“You can at least tell me her name if you’re forcing me to have her in my house.”

His uncle looked up, sightless brown eyes calm and peaceful. “Name’s Katie. Katie Byler.”

“Katie Byler!” Freeman repeated. “Absolutely not.” He flinched as he spoke and pain shot up his leg. He groaned, reaching down to steady his casted leg. “Not Katie Byler, Uncle Jehu. Anyone but Katie Byler.” He frowned. “She’s the bossiest woman I ever met.”

His uncle chuckled. “I thought you said your mudder was the bossiest woman you ever met. Ya, I distinctly remember you saying that.” He rose, tucked his loop of string into his trousers’ pocket and made his way to the door. He chuckled again. “And maybe my sister was. But I never saw that it did your father any harm.”

“Please, Uncle Jehu,” Freeman groaned. “Get someone else. Anybody else.”

“Too late,” his uncle proclaimed. He pushed open the door and grinned. “Sara, Katie. Come on in. Freeman and I’ve been waiting for you.”

* * *

Katie followed Sara into the Kemp house, pausing just inside the doorway to allow her vision to adjust to the interior after the bright July sunshine.

“Here’s Katie,” Sara announced, “just as I promised, Jehu. She’ll lend a hand with the housework until he’s back on his feet.” She motioned Katie to approach the bed. “I think you two already know each other.”

“Ya,” Freeman admitted gruffly. “We do.”

“We’re so glad you could come to help out,” his uncle said. “As you can see by this mess, you haven’t come a day too early.”

Katie removed her black bonnet, straightened her spine, and took in a deep breath. The girls were right about one thing; Freeman Kemp wasn’t hard on the eyes. Even lying flat in a bed, one leg encased in an uncomfortable-looking cast, he was still a striking figure of a man. The indoor pallor and the pain lines at the corners of his mouth couldn’t hide the clean lines of his masculine jaw, his white, even teeth, or his straight, well-formed nose and forehead. His wavy brown hair badly needed a haircut, and he had at least a week’s growth of dark beard, but the sleeveless cotton undershirt revealed a tanned neck, and broad, muscular shoulders and arms.

Freeman’s compelling gaze met hers. His eyes were brown, not the walnut shade of Sara’s but a golden brown, almost amber, with darker swirls of color, and they were framed in lashes far too long for a man.

Had he caught her staring at him? Unnerved, she recovered her composure and concealed her embarrassment with a solicitous smile. “Good morning, Freeman,” she uttered in a hushed tone.

Puzzlement flickered behind Sara’s inquisitive eyes, and then her apple cheeks crinkled in a sign of amused understanding. She moved closer to the bed, blocking Katie’s view of Freeman’s face and his of hers and began to pepper him with questions about his impending recovery.

Rescued, Katie turned away to inspect the kitchen that would be her domain for the next two weeks. She’d never been inside the house before, just the mill, but from the outside, she’d thought it was beautiful. Now, standing in the spacious kitchen, she liked it even more. It was clear to her that this house had been home to many generations, and someone, probably a sensible woman, had carefully planned out the space. Modern gas appliances stood side by side with tidy built-in cabinets and a deep soapstone sink. There was a large farm table in the center of the room with benches on two sides, and Windsor chairs at either end. The kitchen had big windows that let in the light and a lovely old German open-shelved cupboard. The only thing that looked out of place was the bed containing the frowning Freeman Kemp.

“You must be in a lot of pain,” Sara remarked, gently patting Freeman’s cast.

“Ne. Nothing to speak of.”

“He is,” Jehu contradicted. “Just too stubborn to admit to it. He’ll accept none of the pain pills the doctor prescribed.”

Freeman’s eyes narrowed. “They gave them to me at the hospital. I couldn’t think straight.”

Katie nodded. “You’re wise to tough it out if you can. Too many people start taking those things and then find that they can’t do without them. Rest and proper food for an invalid will do you the most good.”

Freeman glanced away, as if feeling uncomfortable at being the center of attention. “I’m not an invalid.”

Katie sighed, wondering if a broken femur had been the man’s only injury or if he’d taken a blow to the head. If lying on your back, leg encased in a cast propped on a quilt, didn’t make you an invalid, she didn’t know what did. But Freeman, as she recalled, had a stubborn nature. She’d certainly seen it at the King wedding.

For an eligible bachelor who owned a house, a mill and two hundred acres of prime land to remain single into his midthirties was almost unheard of among the Amish. Add to that Freeman’s rugged good looks and good standing with his bishop and his church community. It made him the catch of the county, several counties for that matter. They could have him. She was a rational person, not a giggling teenager who could be swept off her feet by a pretty face. Freeman liked his own way too much to suit her. Working in his house for two whole weeks wasn’t going to be easy, but he or his good looks certainly didn’t intimidate her. She’d told Sara she’d take the job and she was a woman of her word.

“I agree. Rest is what he needs.” Ivy Kemp came into the house, letting the terrier out the door as she entered. “But he’s always been headstrong. Thinking he could tend to that injury to the bull’s leg by himself was what got him into trouble in the first place. And not following doctor’s orders to stay in bed was what sent him back to the hospital a second time.”

“Could you not talk about me as though I’m not here?” Freeman pushed himself up on his elbows. “Two weeks, not a day more, and I’ll be on my feet again.”

“More like four weeks, according to his doctors,” Jehu corrected.

Katie noticed that the blind man had settled himself into a rocker not far from Freeman’s bed, removed a string from his pants’ pocket, and was absently twisting the string into shapes. She didn’t know Jehu well but she’d seen how easily he’d moved around the kitchen and how he turned his face toward each speaker, following the conversation much as a sighted person might. She found him instantly likable.

“Do you know this game?” Jehu asked in Katie’s general direction. “Cat’s cradle?”

“She doesn’t want to play your—”

“I do know it,” Katie exclaimed, cutting Freeman off. “I played it all the time with my father when I was small. I love it.”

“Do you know this one?” Jehu grinned, made several quick movements and then held up a new string pattern.

Katie grinned. “That’s a cat’s eye.”

“Easy enough,” the older man said, “but how about this one?”

“Uncle Jehu, she didn’t come to play children’s games.” Freeman again. “She was hired to clean up this house.”

Katie rolled up her sleeves. “So I was.” She glanced Jehu’s way. “Later on, I’ll show you one you might not know, but right now I better get to work.” She turned back in the direction of the kitchen appliances. “I can see I’m desperately needed. There’s splatters of milk all over the floor near the stove, and I see ants on the countertop.” She removed her black apron and took an everyday white one from the old satchel she’d brought with her.

“It sounds as if Katie has her day’s work cut out for her.” Sara clapped her hands together. “I’d best get on my way and leave her to it.”

Ivy glanced out the window. “I see she’s driven her own buggy.”

“Ya,” Katie confirmed. “We came in two vehicles.”

“Katie lives in Apple Valley with her mother and brother,” Sara volunteered. “Too far for her to drive back and forth every day. I have all those extra bedrooms since I added the new addition to my house. It seemed sensible that she should stay with me.”

Especially since my brother just brought home a wife, Katie thought. Patsy deserved to have the undisputed run of her kitchen. Katie was quite fond of Patsy, who seemed a perfect wife for Isaac. But Katie didn’t need to be told that an unmarried sister was definitely a burden on a young couple, so taking this job and living away for a while would give them time to settle into married life. Plus the money she earned by her labor would be put to good use.

“No need for you to run off so quick,” Ivy told Sara. “Won’t you take a cup of tea over at my place?”

Ivy Kemp was a neat little woman, plump rather than spare, tidy as a wren and just as cheerful. Again, Katie only knew her from intercommunity frolics and fund-raisers, but she seemed pleasant and welcoming.

“Tea?” Jehu got to his feet with more vigor than Katie would expect of a man near seventy. “Tea would hit the spot, Ivy. You don’t happen to have any of those raisin bran muffins left over, do you?”

“As a matter of fact, I do.” Ivy beamed, heading for the door. “But I won’t promise they taste as good as they did yesterday when they came out of the oven. You will stay for tea, won’t you, Sara? I do love a chance to chat with someone from another church. I hear you made a good match for that new girl with that young man—what’s his name...”

In less time than it took Katie to locate a broom, she and Sara had made their goodbyes, and the three older people had left to go next door to the grossmama haus for their tea and muffins. Ivy had invited Katie, too, but she’d declined. There was too much to do in Freeman’s house and she wanted to get busy.

“I imagine you’ll be wanting dinner at noon,” she said to Freeman, careful not to look directly at his face and into those striking golden eyes. “Do the doctors have you on a special diet?”

“Oatmeal,” he said testily. “I’ve been eating a lot of oatmeal.”

Katie cut her eyes at him. “Odd thing for a sickbed.”

“I’m not sick.”

“Ya, you said that.” She opened the refrigerator and grimaced. “I hope the milk and eggs are fresh.”

“And why wouldn’t they be?”

“If they are, they would be the only thing in that refrigerator that is. It looks as if a bowl of baked beans died in there. The butter is covered in toast crumbs and it looks like there’s a hunk of dried up cheese in the back.” She wrinkled her nose. “Pretty pitiful fare.”

“Spare me your humor.” Freeman shut his eyes. “Just cook something other than oatmeal or chicken noodle soup. Anything else. My grandmother has served me so much chicken soup it’s a wonder I’m not clucking.”

“I’ll keep that in mind.” She closed the refrigerator door, thinking of the cut-up chicken that Sara had insisted they bring in a cooler. Chicken soup had been one of her options, since she’d known that Freeman was confined to bed and recovering from a bad accident. But she could just as well fry up the chicken with some dumplings. Providing, of course, that there weren’t weevils in the flour bin. She’d have to take stock of the pantry and freezer, if Freeman even had a freezer or a flour bin. If they expected her to cook three decent meals a day, she’d have to have the groceries to do it.

She decided that cleaning the refrigerator took precedence over the sticky floor; she’d just sweep now and mop later. Once that was done, she decided she’d better do something about the state of the kitchen table. The tablecloth was stained and could definitely use a washing. Someone had washed dishes that morning and left them on the sideboard to dry, but dirty cups, bowls and silverware littered a side table next to Freeman’s bed. A kitchen seemed an odd place for a sick man to have his bed, but she could understand that he might want to be in the center of the home rather than tucked away upstairs alone. And it could be that the bathroom was downstairs. She hadn’t been hired for nursing, but, if she knew men, doubtless the sheets could stand laundering.

“That wasn’t kind of you,” she remarked as she cleared the table and stripped away the soiled tablecloth. “Chastising your uncle when he wanted to show me his string game. You should show more respect for your elders.”

Freeman opened one eye. “He’s blind, not slipping in his mind. Cat’s cradle is for kinner. It was him I was thinking of. I wanted to save him embarrassment if you assumed—”

“I hope my mother taught me better than that,” Katie interrupted. “I try not to form opinions of people at first glance or to judge them.” He didn’t answer, and she turned her back to him as she scrubbed the wooden tabletop clean enough to eat off. She would look for a fresh tablecloth, but if none were available, this would suffice until she could do the laundry.

“I don’t mean to be rude,” Freeman said. He exhaled loudly. “I didn’t know you were coming—didn’t know any housekeeper was coming. It was my uncle’s idea.”

“I see.” Katie moved on to the refrigerator. The milk container seemed clean and the milk smelled good so she put that on the table with whatever else seemed salvageable. The rest went directly into a bucket to be disposed of. “It’s been a good while since anyone did this,” she observed.

“It’s not something that I can manage with my leg in a cast.”

“Six months, I’d guess, since this refrigerator has had a good scrub. You don’t need a housekeeper, you need a half dozen of them if you expect me to get this kitchen in shape today.”

“It’s not that bad.” He pushed up on his elbows. “Neither Uncle Jehu nor I have gotten sick from the food.”

“By the grace of God.” The butter went into the bucket, followed by a wilted bunch of beets and a sad tomato. “Do you have a garden?”

Freeman mumbled something about weeds, and she rolled her eyes. Sara’s garden was overflowing with produce. She’d bring corn and the makings of a salad tomorrow. A drawer contained butter still in its store wrapping. The date was good, so that went to the table. “Is there anything you’re not supposed to eat?” she asked.

“Oatmeal and chicken soup.”

She smiled. He was funny; she’d give him that. “So you mentioned.”

A few changes of water, a little elbow grease and the refrigerator was empty and clean. Katie started moving items from the table, thinking she’d run outside and get the chicken to let it sit in salted water.

“Butter goes on the middle shelf,” Freeman instructed.

She glanced over her shoulder at him. “Not where it says butter?” She pointed to the designated bin in the door with the word printed across it.

He scowled. “We like it on the middle shelf.”

“But it will stay fresher in the butter bin.” She smiled sweetly, left the butter in the door and went back to the table for the milk.

A scratching at the screen door caught her attention and she went to see what was making the noise. When she opened the door, the small brown-and-white rat terrier that Ivy had let out darted in, sniffed her once and then made a beeline for Freeman’s bed. “Cute dog.”

“His name is Tip.” The terrier bounced onto a stool and then leaped the rest of the way onto the bed. He curled under Freeman’s hand and butted it with his head until Freeman scratched behind the dog’s ears.

Katie watched him cuddle the little terrier. Freeman couldn’t be all bad if the dog liked him.

She filled the kettle with water and put it on the gas range. She’d seen that there was ice. She’d make iced tea to go with dinner. And if there was going to be chicken and dumplings, she would need to find the proper size pot and give that a good scrub, as well. She planned the menu in her head. Besides the chicken dumplings, she’d have green beans and pickled beets, both canned and carried from Sara’s pantry, possibly biscuits and something sweet to top it all off. She’d have to check that weed-choked garden to see if there was something ripe that she could use.

“What are you making for dinner?” Freeman asked.

Oatmeal, she wanted to say. But she resisted. It was going to be a long two weeks in Freeman Kemp’s company. “I’m not sure yet,” she answered sweetly. “It will be a surprise to us both.”

“Wonderful,” Freeman said dryly. “I can’t wait.”

Katie swallowed the mirth that rose in her throat. Her employer’s nephew might not be the cheeriest companion but at least she wouldn’t be bored. Sara had warned her that working in Freeman’s house would be a challenge. And there was nothing she liked better.

Chapter Two (#ulink_51fc8fdb-aba6-5a56-8f5e-0098089cdca7)

Freeman watched Jehu reach for another biscuit. It was evening and the air was noticeably cooler in the house than it had been in the heat of the afternoon. Being cooped up in the house was making Freeman stir-crazy as it was; the heat seemed to add to his irritability. Thinking back on the day, he hoped he hadn’t been too ill-tempered with Katie. He didn’t mean to be short with people; it was just his situation that made him crabby. That and the radiating pain in his leg.

Jehu and Ivy were seated at the kitchen table eating leftovers from the midday meal that Katie had cooked. He was lying in his bed, but Katie and Jehu had moved it closer to the table for the noon meal so that he could more easily be included in the conversations, and no one had bothered to push the bed back against the wall. Katie hadn’t stayed to have supper with them, though he’d almost hoped she would. It was nice to have someone else to talk to besides his uncle and grandmother. Before Katie left to return to Sara Yoder’s, where she was staying, she’d heated up the leftovers, carried them to the table and made him a tray.

“Good biscuits.” Jehu felt around for the pint jar of strawberry jam Katie had brought them from her own pantry.

“I thought you must think they were,” Ivy remarked. “Since that’s your third.”

Jehu smiled and nodded. “They are. Aren’t they, Freeman?”

“Mmm,” Freeman agreed. It was hard to talk with his mouth full. Nodding, he used the rest of his biscuit to sop up the chicken gravy remaining on his plate. He couldn’t remember when anything had tasted so good as the meal Katie had served them this afternoon and he was now enjoying it all over again. The green beans were crisp and fresh, and the chicken and dumplings were exactly like those he remembered his mother making. His grossmama Ivy had always been dear to him, but no one had ever called her a great cook.

“She’s done a marvel on this kitchen,” his grandmother pronounced. “She’s managed to find the kitchen table under the crumbs and I can walk on this floor without hearing the sand grit under my feet.” She looked at Freeman. “We should have got her in here the week you got crushed by that cow.”

“It was a bull,” Freeman reminded her.

She lifted one shoulder in a not convinced gesture. “Not a full grown one.”

“Nine hundred pounds, at least.” Freeman reached for his coffee. It tasted better than what he usually made. Katie’s work, again.

“Pleasant girl, don’t you think?” his uncle remarked. For a man who couldn’t see, Uncle Jehu had no trouble feeding himself. Somehow, he could eat and drink without getting crumbs in his beard or spots on his clothing. He’d always been a tidy person, almost dapper, if a Plain man could be called dapper. He liked his shirts clean and he wouldn’t wear his socks more than once without them being washed. “That Katie Byler.”

“Ya,” Freeman agreed. The food was certainly a welcome relief from his grandmother’s chicken soup, and the kitchen did look better clean, but there was such a thing as overdoing the praise. He wiggled, trying to get in a more comfortable position. He’d had an itch somewhere near the top of his knee, but it was under the heavy cast and he couldn’t scratch it. Even when he wasn’t in pain there was a dull ache, but he’d just about gotten used to that. It was the itch that was driving him crazy.

“A hard-working girl who can cook like that will make someone a fine wife,” Jehu remarked.

“I was thinking the same thing.” Ivy wiped her mouth with a cloth napkin; Katie had found a whole pile of them in one of the cupboards. “Girls like that get snapped up fast. And she’s pleasant-looking. Don’t you think so, Freeman?”

“What was that?” He’d heard what she said, but didn’t really feel comfortable commenting on a woman’s looks. Besides, he had a pretty good idea where this conversation was going. They had it all the time, and no matter how often he told Jehu and Ivy he wasn’t looking for a wife, they continued looking for him.

“Pretty. I said Katie was pretty. Or hadn’t you noticed?” She glanced at Uncle Jehu and chuckled. He gave a small sound of amusement as he spooned out the last of the dumplings from the bowl on the table onto his plate, without spilling a drop.

“I thought she might be, just by the sound of her voice,” Uncle Jehu said. “You can tell a lot about a person from their voice. Wonder if she’s walking out with anybody?”

“Sara says not.” His grandmother eyed the blackberry cobbler on the table. There was nearly half of the baking dish left, plenty for the three of them to enjoy.

Freeman’s mouth watered thinking about it. Katie had made it with cinnamon and nutmeg and just the right amount of sugar. Too many women used more sugar than was needed in desserts and hid the taste of the fruit with sweetness.

“This coffee could use a little warming up.” Freeman lifted his mug. “I don’t want to put anyone to any trouble, but...”

“It won’t kill you to drink it like it is,” his grossmama told him. “Too much hot coffee’s not good for broken bones. Raises the heat in the body. Cool’s best. Keeps your temperature steady.”

Freeman swallowed the rest of his coffee. There was no use in asking Uncle Jehu to warm up his coffee. He’d just side with Ivy. He usually did, Freeman thought, feeling his grumpiness coming on again. The itch on his leg remained persistent, and he wondered if he could run something down inside the cast to scratch it without causing any harm.

“Freeman could do a lot worse,” Uncle Jehu went on. “He’s not getting any younger.”

“Than Katie?” Ivy pursed her mouth. “You’re right, Jehu. I don’t know why I didn’t think of that myself. She’d fit in well here. And it’s long past time—”

“Don’t talk about me as though I’m not here,” Freeman interrupted. “And I’m not courting Katie Byler.”

“And what’s wrong with her?” Grossmama demanded, turning to him. “She seems a fine possibility to me.”

“Absolutely not,” Freeman protested, pushing his tray away. “And if this is something you’ve schemed up with Sara Yoder, you can forget it. Katie may make a great wife for someone else, but not for me.”

* * *

Katie tossed a handful of weeds into a bucket. “Freeman wasn’t as bad as I expected,” she answered when Sara asked her how her day had gone. She, Sara and two of the young women who lived at Sara’s had come into the vegetable garden after supper to catch up on the weeding. Ellie and Mari had started at the opposite end of the long rows of lima beans, while she and Sara had taken this end, giving the two of them an opportunity to talk privately.

Sara grinned. “I knew you could handle him.”

Both she and Sara were barefooted and wearing a headscarf and their oldest dress. The warm soil felt good under Katie’s feet. She loved the scents of rich earth and the cheery chorus of birdsong that seemed present in any well-tended garden.

“I think he’d be a good match for someone.” Sara used her trowel to chop the sprigs of grass and work up the soil around the base of the lima bean plants. “What with the mill and the farm, he’s well set up to provide for a family.”

Katie rolled her eyes. “I don’t know about that. Any woman who takes Freeman Kemp for a husband is asking for trouble. The man thinks he knows everything. Even when he doesn’t. He tried to tell me how to scrub the floor. Can you imagine? And the man doesn’t know where butter goes in the refrigerator. And when I tell him the truth of the matter, he gets all cross.”

Sara added another handful of weeds to the bucket. They would go into the chicken yard and the scavenging hens would make quick work of them. Nothing ever went to waste on an Amish farm. “Men naturally think they know the best way to do things,” she said. “But the wisest of them learn to think before they speak when it comes to women’s chores.”

“I guess no one ever told Freeman that.” Katie tugged at a particularly stubborn pigweed. It came away with a spray of dirt, and she shook it off and added it to the pile. Sara’s garden was as tidy as her house, row after row of green peppers, sweet corn, beets, squash and onions. Heavy posts set into the ground made a sturdy support for the wires that supported lima bean vines. Lima beans were one of Katie’s favorite vegetables and they were the concern this evening. A summer garden that wasn’t worked regularly soon became a tangle of weeds and a haven for bothersome insects.

“Does Freeman seem to be in a lot of pain? Ivy told me the break was a bad one. If he’s irritable, that could be the reason,” Sara suggested.

“Hard to judge how much pain a person is in.” Katie pulled the weed bucket closer to them as they moved down the row. “I think he’s more bored from having to stay in bed than anything else. I know it would drive me to distraction if I couldn’t be up doing.”

“Jehu is nice, though, isn’t he?”

“He is. He was very welcoming. He told me not to pay any mind to Freeman’s grumpiness. He’s an amazing man, really. He knows his way all over that farm, doesn’t need a bit of help. I think Freeman said he can see shadows. But you’d never know Jehu was blind the way he moves.”

Sara tossed a weed in the bucket. “My cousin Hannah told me that he was a skilled leather worker for years. He still works for the harness shop down his way. Pieces he can stitch from memory.”

“It’s such a shame that he lost his sight,” Katie said.

Sara paused in her weeding and gave Katie a thoughtful look. “It is, but God’s will is not always for us to understand. All we can do is accept it and try to make the best of the blessings we have.”

From the far end of the rows, Mari and Ellie began to sing “Amazing Grace.” Ellie, a little person not more than four feet tall, had a sweet, clear soprano voice, while Mari’s rich and powerful alto blended perfectly. Katie smiled, enjoying the sound of their voices in the fading light of the warm evening.

“I had a letter today from Uriah Lambright’s aunt.” Sara straightened up and rubbed the small of her back. “She says that the family is eager for you to come and visit. Have you given any more thought to considering him?”

“Evening,” came a deep male voice.

The four women looked in the direction of the garden gate.

“Ah, James.” Sara smiled at the Amish man in his midthirties who had just walked into the garden.

“Katie, do you know James?” Sara asked.

“We’ve met.” She nodded to him. “Evening to you too, James.”

James smiled at her and then turned his attention back to Sara. “Can I steal away some of your help?” he asked. “It’s such a nice evening, I thought maybe Mari would like to take a ride with me.”

Mari came toward them, blushing and brushing dirt from her skirt. Like Katie, Mari was barefoot with only a scarf for a head covering. “I wish you’d given me fair warning,” she said, smiling up at James. “I’m not fit to be seen. Can you wait long enough for me to make myself decent and see where Zachary is?”

Zachary was Mari’s son, a boy about nine years old. Mari and Zachary were staying with Sara while they made the transition from being English to becoming Amish again. Mari had been raised Amish, but had left the church as a teen and was now returning to the church.

James laughed and used two fingers to push his straw hat higher on his forehead. He was a tall, pleasant-looking man with a quick smile. “I’ll wait, but you look fine to me. If you’re going to change your clothes, you’d best be quick. Zachary’s already in the buggy, and he’s trying to convince me that we should go for ice cream.”

Mari glanced at Sara who made shooing motions. “Go on, go on,” Sara urged. “We can finish up here.”

“You’re sure?”

“Off with you before I change my mind and put James to work, too,” Sara teased.

James swung the gate wide open and Mari hurried to join him. The two walked off, already deep in conversation.

Katie watched them for a minute. She wasn’t jealous of Mari’s happiness, but she was wistful. Katie wanted to marry and have children, but she was beginning to fear it would never happen. She had always assumed God intended her for marriage and a family; it was what an Amish woman was born to. But what if He didn’t wish for her to marry?

With a sigh, Katie returned to her work and she and Sara continued weeding until they met Ellie halfway down the row. “You’re a fast worker,” she told Ellie, observing her work. The soil behind Ellie was as neat and clean as a picture in a garden magazine.

“Danke. I try.” Ellie’s face creased in a genuine smile. “I think the beans at the far end will be ready for picking by tomorrow afternoon.”

“If you can wait until after supper, I’d be glad to help you,” Katie offered. She liked picking limas, and gardening with other women was always easier than doing it alone. “Willing hands make the work go faster,” her mother always said.

“Great,” Ellie replied. “It won’t take long if we pick them together.”

Ellie was the first little person that Katie had ever known, but someone who obviously didn’t let her lack of height hinder her. Sara had explained privately that although Ellie had come to Seven Poplars to teach school, Sara had every hope of making a good marriage for her. Ellie was certainly pretty enough to have her choice of men to walk out with, with her blond hair, rosy cheeks, and sparkling blue eyes. Katie had liked her from the first, and she hoped that they might become good friends.

“All right,” Sara said, looking across the garden. “I think we’ve got time to do another row. But there are a lot of full pods on this row. I think we better get to them. Who wants to pick while the other two keep weeding?”

“You pick,” Katie told Sara. “I don’t mind weeding. It’s satisfying to see the results when I’m finished.”

“Ya,” Ellie said. “Good idea. I can weed, too.”

“All right,” Sara brushed the dirt off her hands. “It’s a bumper crop this summer. Just the right amount of rain, thank the Lord.”

“Let’s get to it,” Katie told Ellie. “Once it starts to get dark, the mosquitoes will come out, and we’ll be fair game, bug spray or no bug spray.”

Nodding agreement, Ellie and Katie began to pull weeds again while Sara sought out the plump lima bean pods amid the thick foliage. Conversation came easily to the three of them, and Katie found herself more at ease with Ellie with every passing minute. She was good company, making them double over with laughter at her tales of students. Katie hadn’t attended the Seven Poplars schoolhouse, but she’d been there several times for fund-raising events, and Ellie was such a good storyteller that she could picture each event as Ellie related it. Her own school, further south in the county, had been larger, with two rooms rather than one, but otherwise almost identical. Both schools were first through eighth grade and taught by young Amish women.

Sara soon filled her apron with limas and had to return to the house for a basket for them and a second bucket to hold the weeds. When she returned, she brought a quart jar of lemonade to share. Katie and Ellie stopped work long enough to enjoy it before taking up their task again.

“I had a letter from one of my former clients in Wisconsin,” Sara said when they’d reached midrow. “Dora Ann Hostetler.”

“Do you know her, Ellie?” Katie asked, remembering that Sara had told her that Ellie had come from Wisconsin, too.

Ellie slapped at a hovering horsefly and shook her head. “Ne, but Wisconsin’s a big state. A lot more Amish communities there than here.”

“Anyway,” Sara continued. “Dora Ann was a widow with three little girls. A plain woman, but steady, and with a good heart. I found just the man for her last year, a jolly widower with four young boys in need of a mother. She wrote to say that she and Marvin have a new baby boy. She also wanted me to know that her bishop will be visiting in Dover next month, and he’ll be preaching here in Seven Poplars. She likes him and assures me that he preaches a fine sermon.” She looked at Katie. “Will you be coming to church with us, or going home to your family’s church?”

Katie paused in her weeding. “I think I’d like to come with you while I’m here,” she said. Sara’s mention of the letter from her friend reminded her of the one that Sara had received from Uriah’s aunt. “You started to tell me earlier about the note from Uriah’s family,” she reminded.

“Yes, but...” Sara hesitated. “Would you rather discuss that in private?”

“Ne, I don’t mind.” Katie chuckled. “Actually, I’d like to hear Ellie’s opinion.”

Sara placed her basket, now nearly full of lima beans, on the ground. “Katie has an interested suitor,” she explained to Ellie. “A young man who used to be a neighbor to her family here in Kent County.”

“Uriah, his parents and brothers and sisters moved to Kentucky years ago,” Katie said as she tamped down the weeds in the bucket to make room for more. “Uriah is the oldest.”

“The family has a farm and a sawmill in Kentucky,” Sara added. She continued searching for ripe beans. “Uriah’s father made initial contact with me a few weeks ago about the possibility of making a match for his son with Katie.”

Katie threw Ellie a wry look. “It was the father who asked about me, mind you, not Uriah.”

Ellie sat back on her heels and glanced from Katie to Sara and back to Katie. “So you know Uriah from when you were younger?”

Katie nodded. “They left when we were twelve, maybe thirteen. He was in the same school year as I was. They come back every year or so to see family so I’ve seen him a few times over the last few years.”

“Then you must have some idea of what you think of him,” Ellie said. “Is he someone you can imagine yourself married to?”

Katie sighed. “That’s the problem. I don’t know. I mean, I know he’s a good person and strong in his faith. He’s shy; he’s always been shy. I suppose that’s why his father made the inquiry. And there’s nothing wrong with him.” She sighed again.

“Well, is he hardworking? Does he have any bad habits? Those are the kinds of questions I think you need to ask yourself.” Ellie worked up the ground around the base of a plant. “But I guess the important thing is, do you like him?”

Katie thought for a minute. “I do like him,” she said, then she wrinkled her nose. “I just never thought of him as a possible husband. He was just sort of always...there.”

“So what you’re saying is what?” Ellie asked. “Boring?”

“Ellie!” Sara’s admonition was only half-serious. “What way is that to talk of a man you don’t even know?”

“No... I wouldn’t call Uriah boring,” Katie answered. “He’s serious, but not, you know, not deadly serious.” She thought for a minute. “And he likes dogs. He always had a dog.”

Ellie laughed merrily. “Now there’s a recommendation for a husband. Or it would be if you were a dog.” She shook her head. “It doesn’t sound as if you’re too excited about this offer. So there’s got to be something about him that you don’t like or you’d be more enthusiastic about the idea.” She hesitated. “I know looks shouldn’t matter to us, but...do you find him unattractive?”

“Ne,” Katie insisted. “It’s not like that. He isn’t...ugly. He’s...I don’t know...average-looking, I suppose, and he has nice teeth.”

Ellie giggled. “Nice teeth. There’s a plus.” She shook the dirt off a weed and tossed it playfully at Katie. “If I were you, I wouldn’t be able to contain myself. Not boring, nice teeth, and too shy to come and check you out for himself. Yup. That’s the man for you.”

Katie and Ellie both laughed.

“Put that talk by,” Sara chided, in earnest this time. “Uriah Lambright is a respectable candidate. I would have never brought him up to Katie if I didn’t think so. His aunt tells me that he’s building a house for his new bride, and that he’s well thought of in his community. Not every worthy bachelor is forward around the opposite sex. And since Katie says that she has no objections to taking inquiries further, that’s exactly what I’m doing.”

“Could you do that?” Ellie asked Katie. “Marry someone that you weren’t strongly attracted to? I know I couldn’t. When I choose a husband, if I ever do, I want it to be someone I can love.” She wrapped her arms around her tiny waist. “Someone I just couldn’t live without.”

“Some marriages do start with romance,” Sara conceded, “but not all of them. I’ve arranged many matches between total strangers. There must be respect and liking, and then often, if both parties want the partnership to be successful, love follows.”

“My mother says the same thing.” Ellie got to her feet and brushed the dirt off the back of her dress. “She tells me that if I wait for romantic love, I may end up an old maid, caring for other people’s babies and sitting at other women’s tables.”

“That’s exactly what I’m afraid of,” Katie agreed. “That’s why I know I should take the Lambrights’ offer seriously. I want romance. I want love. But what if that’s not what God intends for me?” Without another weed in sight, she rose to her feet, too. “I’m not saying I’m ready to say ya to Uriah, but neither am I willing to just say no outright. What if he is the person God intends for me to wed? And so far, he’s the only one who’s shown any interest other than the occasional ride in a buggy home from a singing.”

“I don’t know.” Ellie turned thoughtful. “I understand what you’re saying, but I think I hear a but there.” She looked up at Katie. “You’re saying all the right things, but I think there has to be something about this Uriah that makes you cautious.”

“I suppose it’s that I’m not convinced that Uriah is interested in me,” Katie admitted readily. “He hasn’t written, and he hasn’t come to see me. What if his family is more interested in this match than he is? I know that his parents and his grandmother always liked me, but I wouldn’t be marrying them. What if Uriah’s being pushed into this match?”

“That’s always a possibility,” Sara agreed. “And if that’s the case, then I certainly wouldn’t advise you to accept his offer of courtship. But you don’t know the facts yet. Both you and Ellie are young, and the young tend to believe they have all the answers.” She met Katie’s gaze, waggling her finger at her. “I will tell you this. More than one young woman has broken her own heart waiting for the perfect man to appear from far off, while the one she should have chosen—” she pointed at Katie “—was standing right in front of her.”

Chapter Three (#ulink_47ea4706-cba6-55bd-9638-431f02bc3c28)

There were no complaints from Freeman on the meal Katie cooked the following morning, and if not jovial, he was at least polite to her. Jehu had a third helping of bacon and toast, and Freeman did admit that her meal was an improvement over his grandmother’s oatmeal.

Ivy hadn’t come over to the big house yet; presumably, the older woman was enjoying a respite from the men and eating her preferred breakfast. Still, Katie missed Ivy’s cheerful presence at the table. She liked Ivy’s no-nonsense way of dealing with the men, especially Freeman, and she reminded Katie of her own grossmama, Mary Byler, who’d passed away several winters earlier.

Once everyone had eaten and the dishes were washed and put away, Jehu and the dog went to the mill and Katie turned to the laundry. “When is the last time those sheets of yours were washed?” she asked Freeman.

He scowled at her. “Not long.”

“How long exactly?” she persisted.

“Probably when I came home from the hospital.”

She sniffed in disapproval and pursed her lips. “It won’t do, you know. Lying on dirty linens.”

His dark eyes narrowed. They were still beautiful eyes, but the expression was peevish and resentful, like an adolescent who’d been told he couldn’t go fishing with his friends but had to stay home and clean the chicken coop. “And how do you suggest that I change and wash these sheets?”

“Don’t be surly,” she scolded. “I’ll do the washing, but you’ll have to get out of bed so that I can strip it.”

Freeman rapped on his cast with a fist. “Doctor says that the leg has to remain elevated.”

Katie sighed with impatience. “We’re both intelligent people. I think we can figure out a solution.” The previous day, when she’d first come in, she’d noticed a wheelchair folded up and resting against the wall, the packing strap still wrapped around it. Clearly, Freeman had never used the chair. Resolutely prepared for resistance, she approached the bed. “Are you decent?”

“I should hope so. I try to do the right thing.”

It took all of her willpower not to show her exasperation. He was wearing a light blue shirt, wrinkled but clean, rather than the sleeveless T-shirt he’d worn the day before. She’d wanted to know if he had trousers on under the sheet and blankets. And she had the feeling that he knew exactly what she’d been asking and chose to be difficult. “You know what I mean,” she said briskly. “Are you wearing anything other than your skin below your waist?”

Two spots of color glowed through the dark stubble on his cheeks. “Ya,” he muttered. “Grossmama cut a leg off a pair of my pants so I could pull them on over the cast. The traveling nurse was coming to the house when I first got home from the hospital so—” He scowled at her, his blush becoming even more evident. “Why would you need to know what I have on under my sheet?”

Katie pursed her lips and regarded him with the same expression she used with her brothers when they were being impossible. “Because I need to change those sheets, and I can’t get you out of the bed and into the wheelchair without your cooperation.” She folded her arms resolutely. “You’re certainly too heavy for me to carry, but if you’re a miller, I’d guess that you have a lot of strength in your upper body. If I bring that wheelchair up beside the bed, can you use your arms to maneuver into it?”

“Didn’t say yet that I want to get out of bed,” he protested.

She could tell it wasn’t much of an argument, more for show than anything else. “Of course you want to get up. You’d have to be thick-headed to want to stay there like a lump of coal.” She tilted her head, softening her voice. “And, Freeman, you’re anything but slow-witted if I’m any judge.”

“I suppose I could manage to heave myself into the thing,” he said grudgingly. “I hadn’t decided if I was keeping it, though. Wheelchairs are expensive. I’ll be back on my feet soon enough and—”

“It’s going to be weeks before you’re back on your feet,” she interrupted. “Too long for you to lie in that bed.” She stared down at him and he stared up at her and it occurred to her that they could possibly be there all day just waiting to see who would bend first.

He did.

“Fine,” he finally muttered. “But, I warn you, there aren’t any more sheets in the house to fit this size bed. Am I supposed to sit in that contraption all day while you do the laundry and hang it out to dry?”

She tried not to show how amused she was. Stubborn, the man was as stubborn as a broody hen refusing to budge off a clutch of wooden eggs. She suspected he wanted to be out of that bed more than she wanted him to do it, but he wasn’t going to make it easy for her. “You must have other sheets. In a linen closet?”

He nodded. “But I just told you. They won’t fit. They’re for larger beds than this.”

“That’s women’s matters. No need for you to worry yourself over it.” She gave him a sympathetic look. “I’m sure it will be painful...moving from the bed to the chair. If it really is too much, just say so.”

Again, the scowl. “I’m not afraid of a little pain.”

She went to the wheelchair, cut the plastic shipping strap with scissors and began to unfold it. “While you’re out of bed, maybe you could find your razor. You’re badly in need of a shave.”

Being unmarried, Freeman should have been clean-shaven. Either he or someone had shaved him in the last week, but he had at least a five-day growth of reddish-brown beard. His hair was too long. Getting him shaven and onto clean sheets would be a small victory. And she’d found with her father and brothers that small steps worked best with men. You had to make them think ideas were their own. Otherwise, they tended to balk and turn mulish. She hesitated, and then suggested, “I could do it for you, if you like. My brother, Little Joe, broke two fingers on his right hand once and I—”

“I can shave myself. It’s my leg that’s broken, not my hand.”

When she glanced back to the bed, Freeman was looking at the wheelchair with obvious apprehension. She understood his hesitation, but she truly did think his upper body was strong enough to move himself safely into the wheelchair. “If you did get in the chair, you could go out on the porch easy enough,” she said with genuine kindness. “It’s a beautiful day. You must be going mad as May butter staring at these kitchen walls.”

“I am,” he admitted.

Her irritation was fading fast. Freeman was a challenge. He might be prickly, but he was interesting. Being with him kept her on her toes and anything but bored. It must take a lot of energy for him to pretend to be so grumpy. And she suspected it wasn’t his true nature. “What was that?” she teased.

His high brow furrowed. “I said I am. I’m tired of staring at this room. A house is no place for a man in midmorning.”

“Which is our best reason for getting you out of that bed. An easy mind makes for quicker healing.” She brought the wheelchair to the side of the bed. “Careful,” she warned. “Let me help you.”

“Ne. You steady the chair so it doesn’t roll.”

“It won’t. I’ve put the brakes on.”

“Stand aside, then, and let me do it by myself.” Slowly, pale and with sweat breaking out on his forehead, Freeman managed the gap from the bed to the chair. Katie knew that it must have hurt him, but he didn’t make a sound, and finished sitting upright with a look of pure satisfaction on his face.

“Wonderful,” she said, squeezing her hands together. She raised the leg rest and carefully propped his cast on it. Then she released the brake and pushed him out of the kitchen and down the short hall to the bathroom. He told her where to find his razor and shaving cream. “You won’t be able to see into the mirror,” she said, handing him a washcloth and draping a towel around his neck. This mirror was small and fixed to the wall over the sink. “Is there another mirror I could bring in here?”

“I don’t need your help. Just hand me my razor and soap and brush from over there,” he said, pointing to a pretty old oak dresser that she suspected held towels and the like. “I’ve done this hundreds of times. I can manage without the mirror.”

“If you’ll tell me where to find scissors, I could trim the back of your hair. That’s not something you can do yourself,” she offered, putting his things on the edge of the sink.

“My hair is fine. Now go change those sheets you’ve been fussing about.”

She made no argument but went and located a linen closet at the top of the stairs. As Freeman had said, it had sheets for double beds, but she could easily tuck the excess under the mattress. The important thing was that the sheets were clean. They would do for now. Next time, she would have freshly washed and line-dried linen to go on his bed, provided he didn’t fire her first.

When she finished the task and returned to the bathroom, she found him still sitting at the sink, shaving cream on his face and a razor in his hand. There were uneven patches of beard on his cheeks and a trickle of blood down his chin. Wordlessly, he handed the razor to her, grimaced, and clenched his eyes shut. She ran hot water on the washcloth, twisted it until the excess water ran out, and pressed it over his face.

She’d said that shaving Freeman would be no different that shaving her brothers, but as she stood there looking at him, she realized it was. It was very different. She had to steady her hands as she removed the washcloth and began with more shaving cream. Her pulse quickened, and she felt a warm flush beneath her skin.

Shaving Freeman was more intimate than she’d supposed it would be and she was thankful that his dark eyes were closed. The act bordered on inappropriate behavior between an unmarried man and woman, but neither of them intended it to be anything other than what it was. She’d offered with the best of intentions and backing down now would be worse than going through with it, wouldn’t it?

But what if her hands trembled and she cut him? How would she explain that?

She took a deep breath and plunged forward, silently praying, Don’t let my hand slip. Please, don’t let him see how nervous I am. The small curling hairs at the nape of her neck grew damp and her knees felt weak, but she kept sliding the razor down the smooth plane of his cheek. The blade was sharp, and Freeman held perfectly still. If he’d moved, even a fraction of an inch, she knew that the blade would break his skin, but he didn’t, and she managed to finish without disgracing herself.

“All done.” Heady with success, she handed him the wet washcloth. “See, it wasn’t that bad, was it?”

“Thank you.” He wiped his face and opened his eyes.

“I could still do something with your hair,” she offered.

He wiped a last bit of shaving cream from his chin and tossed the washcloth in the sink. “Quit while you’re ahead, woman.”

She laughed. “You do look a lot better.” And he did, more than better. Shaggy hair brushing his shirt collar or not, he had the kind of good looks that cautious mothers warned their daughters against. And with good reason, she thought, as she locked her shaking hands behind her back.

“I’m not a vain man.”

She couldn’t hide a mischievous grin. “Ne?” She thought that he wasn’t telling the exact truth. In her mind, most men were as vain as any woman. They just hid it better. And Freeman had more reason than most to take pride in his looks.

“I’m a Plain man. I have more on my mind than my appearance.”

“I can see that,” she agreed. “But no one said that a clean and tidy man was an offense to the church.”

He fixed her with those lingering brown eyes, eyes that were not as full of disapproval as they had been. “Do you have an answer for everything?” he asked. But she sensed that he was making an effort at humor rather than being sarcastic.

“I try.” She nodded. “Now I’ll leave you to finish washing up. Call when you need me to bring you back out to the kitchen.”

“I think I can push myself,” he grumbled.

Smiling, she left him to go throw the sheets in the wash.

She’d just started mixing a batch of cornbread when Freeman came rolling slowly down the hall. He looked pale, as if he’d run a long distance. She could tell he was in pain, but she didn’t say anything about it. “Do you think you could peel potatoes for me?”

“I suppose I could,” he said. “Isn’t it too early to be starting the midday meal?”

“Too early for cooking. Not too early for starting the preparation. I’ve lots to do this morning, and you have to be organized to get meals on the table on time and still get the rest of your work done.”

“Organization is a good thing,” he agreed. “Not many people understand that. They waste hours that could go to good purpose.”

“Mmm.” She brought him a large stainless steel bowl, a paring knife, and the potatoes. “If you peel these, I’ll cut them up and put them in salted water, ready to cook when it gets closer to mealtime.”

“My mother was a good cook,” he said.

“Mine, too. Better than me.”

“She’s still with you, isn’t she?”

“Ya, thanks be to God. We lost my father a few years ago, but we were fortunate to have him as long as we did. Dat had five heart surgeries, starting when he was a baby. He was never strong, but he lived a full life, and he and my mother were happy together.”

“It’s important, having parents who cared for each other. Mine did, too. They died too soon. An accident.” He shook his head, and she saw the gleam of moisture in his eyes. “I’d rather not talk about it.”

Then why did he bring it up, she wondered. But she was glad that he had, felt that it was a positive step in their relationship. If she was going to work here, for the next two weeks, it would be better if they weren’t always butting heads.

“Do you fish?” he asked.

“What?” She’d been thinking about what he’d said about his parents and hadn’t been giving him her full attention. “Do I like fish? To eat?”

“Ya, to eat. But I meant to catch. I like fishing. It’s what I usually do on summer evenings. We have big bass in the millpond, catfish, perch, as well as sunnies.”

“I do like fishing,” she said. “And crabbing. My dat used to take us to Leipsic. We’d crab off the bridge there. And fish, too, but we never caught many.”

“It takes patience and know-how. Bass, especially, are clever. But very tasty. I use artificial lures for them.”

Jehu strolled in, sniffing the air. “Making corn fritters?”

“Cornbread,” Katie said.

“I love cornbread.” He went to the table and sat down near Freeman. “Laundry going, I hear. You’ve been busy, Katie.” He pulled his cat’s cradle string out of his pocket. “Learned a new one this morning. From Shad, of all people. Shad is Freeman’s apprentice. Good boy, hard worker.”

“I wouldn’t say apprentice,” Freeman corrected. “Shad’s got a long way to go before he can call himself a miller. Thinks too much of himself, that boy. Headstrong.”

“Sounds likes somebody else I know,” Jehu said. He turned his head in Freeman’s direction. “Sounds like you got him up and out of that bed. And shaved, too, if I’m not mistaken. I smell your shaving cream.” He turned toward the sink where Katie was grating a cabbage she’d brought from Sara’s garden. “You’re a good influence on him, Katie. Best thing in the world for him. Get out of bed, cleaned up, and stop feeling sorry for himself.”

The screen door squeaked and Ivy joined them. The terrier ran across the kitchen and leaped up on the newly-made bed. “What are you up to, Katie? Don’t tell me you’re already starting dinner?” She smiled warmly. “Freeman, look at you. Up and shaved. I think I know who to give credit to for this.”

Freeman grimaced, picking up another potato to peel. “Morning, Grossmama. I’m feeling better, thank you.”

“I can see that for myself,” she answered crisply. “And she’s put you to work.”

“I couldn’t find a vegetable peeler,” Katie said. “Just a paring knife.”

“You won’t, not in this house. I’ve got one if you need to borrow it. Help yourself.” She picked up one of the potatoes Freeman had peeled. “Not bad,” she said, “not good, but not bad. Be more careful. Waste not.” She turned back to Katie. “I just made a fresh pot of tea, and I was hoping that you’d come to my house and have some with me.”

“I don’t know,” Katie hemmed. “I’ve got a lot to do.”

“It’ll wait,” Ivy told her, giving a wave. “Come on. We can get to know each other.” She looked up at Katie. “You know you want to.”

“You should go, Katie,” Jehu encouraged. “I’ll keep an eye on Trouble, here.” He tipped his head in Freeman’s direction.

Katie was torn. She did have a lot to do, but it seemed important to Ivy that they share a pot of tea. And God didn’t put them on the earth just to sweep and wash, did He? In the end, people mattered more than chores. It was something her mother, though a hard worker, had instilled in her young. “Oh...why not?” she conceded.

“I’d like some tea,” Freeman said. “But I like mine cold. The doctor said I should drink lots of fluids.” He frowned. “Katie’s busy. We didn’t hire her to sit and drink tea. She has chores to do, and we were having a serious conversation about—”

“Fishing,” his uncle supplied with a grin. “Which means that she’s certainly earned a break. Go along with Ivy, Katie. Enjoy your tea. I’ll make Grumpy his iced tea. Just as soon as he finishes peeling the potatoes.”

Chapter Four (#ulink_6642ad7c-726b-598d-85ec-f1c2deee61f0)

“Come along, dear. We’ll have a cup of tea and get to know each other better.” Ivy’s invitation was as warm and welcoming as her smile as she led Katie down the walkway between the two houses.

The grossmama haus stood under the trees on the far side of the farmhouse where Freeman and Jehu lived. To reach Ivy’s place, she and Katie had only to follow the brick path from Freeman’s porch to a white picket fence. There, a blue gate opened to a small yard filled with a riot of blooming flowers and decorative shrubs. Katie counted at least a dozen different blooming perennials she could put names to and several she couldn’t. There were climbing roses, hydrangea, hollyhocks and lilies, so many flowers that barely a patch of green lawn was visible.

Hummingbird feeders hung on either side of the front door, and the air was filled with the exciting sounds of the tiny, iridescent-feathered creatures, as well as the buzz of honeybees and the chattering voice of a wren. “How beautiful,” Katie said. “Your flowers.”

“They’re God’s gift to us and a constant joy to me,” Ivy said. “They ask only for sunshine and rain and a little care against the weeds and they bloom their hearts out for us. I’m so pleased that you like my garden. Are you interested in flowers?” She pushed open the front door, ushering Katie into a combined kitchen and sitting room.

Everything inside was neat and orderly. The furnishings were simple: a sofa, an easy chair, a rocker and a round oak table and matching chairs. The appliances were small but new, and they fit perfectly into the small, cheerful cottage with its large windows and hardwood flooring. Colorful family trees, cross-stitch Bible verses and a calendar hung on the walls. A sewing basket sat by the rocker, and a copy of the Amish newspaper, The Budget, lay open on the sofa. In the center of the table rested a blue pottery teapot, a sugar bowl and pitcher, with two cups and saucers.

“I do love my tea, even on a warm day,” Ivy said. “I hope you do, too. Coffee is invigorating, but tea calms the mind and spirit.” She waved toward the table. “Please, sit down.”

Katie took a seat at the table. “Your house is lovely.”

“It’s wonderful, isn’t it? Freeman had it built for me just last year. It’s the first new home I’ve ever lived in. I grew up in an old farmhouse near Lancaster, and then when I married Freeman’s grandfather, I came here to the millhouse as a bride. I never had cause to complain, but I do love my grossmama haus. It’s warm in winter, my stove doesn’t smoke and the floors don’t creak.”

Ivy poured tea into one of the cups and handed it to her. Even Ivy’s dishes showed her love of flowers. The cup and saucer were bright with green leaves and purple violets. “But I’m running on. It comes of living alone, I think. It’s not easy, you know. I fear that when I do have company I never give them a chance to get a word in.” Her speech was grandmotherly, but her eyes, alert and missing nothing, gave evidence of an intelligent and still vibrant woman. She smiled again, disarmingly. “So, tell me about your family, Katie. Do you have brothers and sisters?”

“Two brothers,” she answered. “I’m the youngest. There’s Isaac. He’s the oldest and was named after my father. Isaac has the family farm, and then there’s Robert, who lives across the road from us. Our family is small, but close. Isaac and Robert were always inseparable.”

“Two brothers,” Ivy echoed. “I always wanted brothers. I come from a small family myself. My mother had only two of us that lived past babyhood, my sister and me. My father longed so for sons, but it wasn’t to be.”

Katie stirred milk into her tea. “My father and mother were hoping for a girl. There hadn’t been any girls born in my father’s family for two generations.”

“Funny isn’t it, how patterns repeat in families? My husband was an only child and while we hoped for a large family, we were blessed with only the one child as well.” She looked at the window and sighed. “I always imagined having a wealth of grandbabies to hug and fuss over, but there was only Freeman. With two sons married, I suppose your fortunate mother has grandchildren.”

“Two so far, Robert’s. Isaac just married. It’s partially why I took this job. I really like Patsy, and I thought she should have time to settle into her home without a third woman in the house. Mother lives with us, as well. We lost my father a few years back.”

“I heard about that, and I’m so sorry. Your brother Robert has children?”

“Twins. Boys. Just learning to walk. I adore them.”

“So you’re fond of children?”

“I am.”

“I hope when you marry that you are blessed with more than a single child. It’s hard not to indulge them. But Freeman’s father was a precious child and a good man. He never gave us a night’s worry. I know he’s safe with the Lord, but losing him and Freeman’s mother in that accident was a terrible loss. She was like a daughter to me.”

“Freeman mentioned that they had died.”

“A boating accident. They were fishing on the Susquehanna. She was from Lancaster County, and her uncle took them out. We don’t know what happened. They may have struck a rock. They say the currents are dangerous. I was so distraught that the weight of it fell on Freeman’s shoulders.”

“I’m so sorry.”

Ivy sighed. “Death is part of life. But a mother should never have to bury her child. I don’t care what the bishop says. It goes against everything that is right and natural.” She ran her fingertips absently along the edge of her saucer. “You must think my faith is weak, to talk so.”

“Ne,” Katie assured her. “I can’t imagine how difficult it would be to lose both a husband and your only child.”

Ivy swallowed, her eyes, so much like Freeman’s, sparkled with tears unshed. “It was...very hard. They say it gets easier with time and prayer, but some days...” She broke off and looked out the window. A silence stretched between them, but it was one of shared loss rather than awkwardness. After a moment or two, she glanced at Katie and brightened. “How old are you?”

Katie thought it was an odd question. Why did Ivy care how old the housekeeper was? But she wasn’t offended in any way. “Twenty-three,” she answered. “Twenty-four soon.”

“And have you been baptized into the church?”

“I have. Last summer.”

“Good.” Ivy nodded her approval. “I cannot imagine living through such loss without the knowledge that those I love are forever beyond pain and sickness and that I will someday see them again.”

“That’s true,” Katie said. “I feel the same way about my father. I miss him terribly, but he suffered from his condition, and now he is at peace.”

“Ya. I do believe that.”