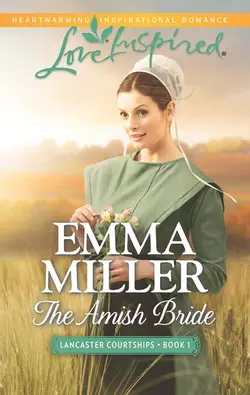

The Amish Bride

Emma Miller

An Unexpected CourtshipEllen Beachey's dreams of being a devoted Amish wife and mother are finally within her reach. But she didn't expect she'd have to choose between two brothers.Golden-haired Micah has a heart filled with adventure and a ready smile. Serious but gentle elder brother Neziah is a devoted and caring father of two. But Ellen and Neziah share a heartbreaking past that might prevent any hope of a future. Ellen never imagined an arranged union as a way to find true love. She wants to be loyal to her family, but she needs to follow her heart…if only she can figure out what it wants.Lancaster Courtships: Life and love in Amish countryCollect all 3 book in the series!The Amish Bride by Emme MillerThe Amish Mother by Rebecca KertzThe Amish Midwife by Patricia Davids

An Unexpected Courtship

Ellen Beachey’s dreams of being a devoted Amish wife and mother are finally within her reach. But she didn’t expect she’d have to choose between two brothers. Golden-haired Micah has a heart filled with adventure and a ready smile. Serious but gentle elder brother Neziah is a devoted and caring father of two. But Ellen and Neziah share a heartbreaking past that might prevent any hope of a future. Ellen never imagined an arranged union as a way to find true love. She wants to be loyal to her family, but she needs to follow her heart…if only she can figure out what it wants.

“No matter what happens between you and me, I think you should find the wife who’s meant for you.”

“Does that mean you prefer Micah over me?” Neziah asked.

“I didn’t say that.”

He felt his heart swell with…hope. “So I’m still in the running?”

She turned to him, and in the darkness he could feel her more than he could see her. “Now you sound like Micah. This is not a contest.” She rose. “I should get home.”

He jumped up. “I guess we need to talk about what happened with us. When we ended our courtship. Do you want to talk about that, Ellen?”

To his surprise, she gave a laugh. “I think we’ve had enough serious discussion for one night, don’t you?”

He smiled and fell in step beside her. “Can I hold your hand?” he whispered.

She laughed again and gave him a little push. And then he felt her small, warm hand slip into his and he grinned all the way to her farmhouse steps.

EMMA MILLER lives quietly in her old farmhouse in rural Delaware. Fortunate enough to be born into a family of strong faith, she grew up on a dairy farm, surrounded by loving parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Emma was educated in local schools and once taught in an Amish schoolhouse. When she’s not caring for her large family, reading and writing are her favorite pastimes.

The Amish Bride

Emma Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

A friend loves at all times…

—Proverbs 17:17

Contents

Cover (#ufd74d835-c250-5979-b6c5-664f3fca1565)

Back Cover Text (#uda8a6be5-20e1-55f3-b90e-cb8ba064167e)

Introduction (#u055c4a43-9a6f-5def-97cf-3fd0d99c617b)

About the Author (#u05f53f05-dfbb-50db-8fd2-2cd78a5938fd)

Title Page (#u80eacc46-668d-5ca6-8527-d12dcb6c1526)

Bible Verse (#u9ec49067-27a5-52b8-8de7-a59dec7a3688)

Chapter One (#ulink_3e750888-a1fd-5fe1-bf9a-9eb1861d2edd)

Chapter Two (#ulink_b8bcc6e9-943e-5744-abd1-3814a40d8d26)

Chapter Three (#ulink_e4093dd8-3552-5cfe-a50b-cc68a2a71e3e)

Chapter Four (#ulink_a90f78ad-da39-5b49-a0fd-7d1427727519)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_b35bdf59-e4f5-5c41-af3c-1430fda0aec3)

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

It was half-past nine when Ellen Beachey halted her push scooter at the top of the steep driveway that ran from her parents’ white farmhouse down to the public road. Normally, she would be at the craft shop by nine, but this had been one of her mother’s bad days when her everyday tasks seemed a lot more difficult. Her mam was in her midseventies, so it wasn’t surprising to Ellen that she was losing some of her vim and vigor. After milking the cow and feeding the chickens before breakfast, Ellen had remained after they’d eaten to tidy up the kitchen, finish a load of wash and pin the sheets on the line.

She didn’t mind. She was devoted to her mutter, and it was a gorgeous day to hang laundry. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky, the sticky heat of August had eased and there was a breeze, sweet with the aroma of ripening grapes and apples from the orchard. But with her dat’s arthritis acting up, and her mam not at her best, Ellen felt the full weight of responsibility for the shop and the household. The craft store was her family’s main source of income, and it was up to her to see that it made a profit.

This had been a good week at Beachey’s Craft Shop. School would soon be starting, and many English families were taking advantage of the last few days of summer vacation to visit Lancaster County. Ellen had seen a steady stream of tourists all week, and the old brass cash register had hardly stopped ringing. It meant good news for Lizzie Fisher, in particular. Her king-size Center Diamond quilt, meticulously stitched with red, blue and moss-green cotton, had finally sold for the full asking price. Lizzie had worked on the piece for more than a year, and she could certainly use the money. Ellen couldn’t wait to tell her the good news. One of the best things about running the shop was being able to handle so many beautifully handcrafted Amish items every day and to provide a market for the Plain craftspeople who made them.

A flash of brilliant blue caught Ellen’s attention, and she glimpsed an indigo bunting flash by before the small bird vanished into the hedgerow that divided her father’s farmstead from that of their neighbors’, the Shetlers. Seeing the indigo bunting, still in his full summer plumage, made her smile. All her life, she’d been fascinated by birds, and this particular species was much rarer than the blue grosbeak or the common bluebird. Ellen wondered if the indigo bunting had a mate and had built a nest in the hedgerow, or was just passing through in an early migration. She scrutinized the foliage, hoping to see the bird again, but it remained hidden in the leaves of a wild cherry tree. She could hear the bird’s distinctive chrrp, but it didn’t reappear.

And, Ellen reminded herself, the longer she stood there watching for the bird, the later she’d be for work. She needed to be on her way. She shifted her gaze to the steep driveway ahead of her.

Maybe this was the morning to be sensible and act like the adult she was. She could just walk her scooter to the bottom of the lane and then hop on once she reached the road. But the temptation was too great. She scanned the pavement in both directions as far as she could see for traffic. Nothing. Not a vehicle in sight. Taking pleasure in each movement, Ellen stepped onto the scooter, gripped the handles and gave a strong push with her left foot. With a cry of delight, she flew down the hill, laughing with excitement, bonnet strings flying behind her.

Ellen waited until the last possible moment before squeezing the handbrakes and leaning hard to one side, whipping the scooter around the mailbox, onto the public road. A cloud of dust flew up behind her, and pebbles scattered as she hit the pavement. The scooter fishtailed and she continued to brake, bringing it to a stop.

One of these days, Ellen thought. One of these days, you’re going to come down that hill so fast that you can’t stop and land smack-dab on top of the bishop’s buggy. But not today.

As she stepped off the scooter, her heart still pounded. Her knees were weak, and her prayer kapp was hanging off her head from a single bobby pin. She was definitely too old to be doing this. What would the community say if they saw John Beachey’s spinster daughter, a fully baptized member of the church and long past her rumspringa years, sailing down her father’s driveway on her lime-green push scooter? Although most Plain people were accepting of small eccentricities within the community, it would almost certainly be cause for a scandal. The deacon would be calling on her father out of concern for her mental, spiritual and physical health.

Chuckling at the thought, Ellen pinned up her kapp and shook the dust off her apron. She moved to the crown of the road and began to make her way toward the village of Honeysuckle. However, she’d no sooner rounded the first wooded bend when she saw a familiar gray-bearded figure sitting on the side of the road.

“Simeon!” she called, pushing the scooter faster. “Vas is? Are you all right?” Simeon Shetler, a widower and a member of her church district, lived next door with his two grown sons and two grandsons. Ellen had known him since she was a child.

“Hallo!” He waved one of his metal crutches. “Jah, I am fine.” He gestured with the other crutch. “It’s Butterscotch who’s in trouble.”

Ellen glanced at the far side of the road to see Simeon’s pony nibbling grass fifty feet away. The pony was hitched to the two-wheeled cart that her one-legged neighbor used for transportation. “What happened?” she asked as she hurried to help Simeon to his feet. “Did you fall out of the cart?”

“Nay, I’m not so foolish as that. I may be getting old, but I’m not dotty-headed.” They spoke, as most Amish did when they were among their own kind, in Deitsch, a dialect that the English called Pennsylvania Dutch. “But I will admit, seeing your pretty face coming down the road was a welcome sight.”

“Have you been like this long?” she asked, taking no offense at his compliment, which might have seemed out of place coming from most Amish men. Simeon was known as something of a flirt, and he always had a pleasant word for the women, young or old. But he was a kind man, a devout member of the community and would never cross any lines of propriety.

“Long enough, I can tell you. It took me ten minutes to climb back out of that ditch.”

As a young man, Simeon had had a leg amputated just below the knee. Although he had a prosthetic leg and had gone to physical therapy to learn how to walk with it, he never wore it. For as long as Ellen could remember, the molded plastic and titanium prosthetic had hung on a peg on his kitchen wall. Usually, Simeon made out fine with his crutches, which extended from his forearms to the ground, but when he fell, he wasn’t able to get back on his feet without a steady object like a fence post, or the aid of a friendly hand.

Simeon grinned. “Some fool Englisher threw a bag of trash from one of those food-fast places into the ditch. I thought I could pick it up if I got down out of the cart. I would have been able to, but I slipped in the grass, fell and slid into the ditch. And then by the time I crawled back out, that beast—” he shook his crutch again at the grazing pony “—trotted away.” He chuckled and shrugged. “So, as you can see, I was stuck here until a Good Samaritan came along to rescue me.”

“Are you sure you’re all right?” she asked, looking him over.

“I’m fine. Catch the pony before he takes off for town,” Simeon urged. “Then we need to have a talk, you and me. I think maybe it was God’s plan this happened this morning. I have something important to discuss with you.”

“With me?” Ellen looked at him quizzically. Simeon was an elder in their church, but she couldn’t think of anything that she’d done wrong that would cause concern. And if she was in trouble for some transgression, it should have been the deacon who’d come to speak to her and her parents to remind her of her duties to the faith community.

Unless...

Was it possible that Simeon or one of his sons had recently seen her antics on the push scooter? She didn’t think so. She was careful about when and where she gave in to her weakness for thrilling downhill rides. And Bishop Harvey had approved the bright color of her push scooter, once she’d explained that she’d gotten it secondhand as a trade for a wooden baby cradle.

The unusually bright, lime-green push scooter was an expensive one from a respected manufacturer in Intercourse. She could have had it repainted, but that would cost money and time, even if she did it herself. Bishop Harvey was a wise leader and a practical man. He understood that, with Ellen’s father owning only one horse, she needed a dependable way to get back and forth to the craft shop without leaving her parents stranded. And if the fluorescent color on the push scooter was brighter than what was customarily acceptable, the safety factor made up for the fancy paint.

“See, there he goes.” Simeon pointed as the pony moved forward, taking the cart with him. “Headed for Honeysuckle, trying to make a bigger fool of me than I already am. We’ll be lucky if you catch him.”

“Oh, I’ll catch him, all right.” Ellen reached for the lunch box tied securely in her scooter basket on the steering column. She unfastened it, removed a red apple and walked down the road toward the pony. “Look what I have!” she called. “Come here, boy.”

Butterscotch raised his head and peered at her from under a thick forelock. His ears went up and then twitched.

Ellen whistled softly. “Nice pony.”

He pawed the dirt with one small hoof, took a few steps and the cart rolled forward, away from her.

“Easy,” Ellen coaxed. “Look what I have.” She held up the apple. “Whoa, easy, now.”

The pony wrinkled his nose and snorted, side-stepping in the harness, making the cart shift one way and then the other. Ellen walked around in front of him and took a bite out of the apple before she offered it again. Butterscotch sniffed the air and stared at the apple. “Goot boy,” she crooned, knowing he was anything but a good boy.

The palomino was a legend in the neighborhood. For all his beauty, he was not the obedient pony a man like Simeon needed. This was not the first time Butterscotch had left his owner stranded. And Butterscotch didn’t stay put in his pasture, either. He was a master of escape: opening locked gates, squeezing through gaps in fences and jumping ditches to wander off into someone’s orchard or garden to feast on forbidden fruit. He’d been known to nip and kick at other horses, and more than once he’d run away while hitched, overturning the cart. Ellen couldn’t imagine why the Shetlers kept him. He certainly wasn’t safe for Simeon’s grandsons to ride or drive. A clever pony like him was a handful for anyone to manage, let alone a one-legged man in his sixties.

Cautiously, Ellen took a few steps closer to the pony. Butterscotch tossed his head and moved six feet farther down the road. “So that’s the way it will be,” she said. The sound of a vehicle alerted her to an approaching car. The driver, coming from the direction of Honeysuckle, slowed. The pony stood and watched as the sedan passed. He wasn’t traffic shy, which was the one good thing that Ellen could say about him.

When the car had disappeared behind her, Ellen took another bite of the apple, turned her back on Butterscotch and retraced her steps toward Simeon. She heard the creak of the harness and the rattle of wheels behind her, but she kept walking. She kept going until she was almost even with Simeon, then stopped and waited. It wasn’t long before she felt the nudge of a soft nose on her arm. Without making eye contact, she held out the remainder of the apple. Butterscotch sunk his teeth into the piece of fruit, sending rivulets of juice dripping down Ellen’s arm. Swiftly, she reached back and took hold of the pony’s bridle.

“Gotcha,” she murmured in triumph.

Once Simeon was safely on the seat of the cart, reins in hand, with the cart turned toward Honeysuckle again, he waved to her scooter. “Why don’t you put that in the back? Ride with me. We can talk on the way.”

Curious and a little apprehensive, Ellen lifted her scooter into the back. He offered his hand. She put a foot into the iron bracket and stepped up into the cart. “Have I done something wrong?” she asked.

She couldn’t imagine what. She hadn’t been roller skating at the local rink in months, and she took care to always dress modestly in public, even if she did wear a safety helmet when she used her scooter in high-traffic areas.

“Of course not.” Simeon shook the reins. “Walk on.” Butterscotch moved forward and the cart rolled along. “You’re an excellent example for our younger girls, Ellen,” he said, turning to favor her with a smile. “You’re devout and hardworking.”

Now he really had her attention. The familiar sound of horse’s hooves alerted her to a horse and buggy coming up behind them. Ellen glanced over her shoulder; the driver was Joseph Lapp. She and Simeon waved as Joseph swung around, passing the pony cart. He waved back and quickly moved on ahead of them.

“Wonder if we’ll start tongues clucking, riding together,” Simeon remarked.

Ellen looked at him, hoping he was joking. Simeon wasn’t going to ask if he could come courting, was he? It seemed like once a month he was asking someone permission to court—a matter that kept the women of the community, from age eighteen to eighty, chuckling. But the twinkle in his faded blue eyes told her that he was teasing, and she relaxed a little.

“I want to discuss with you a problem that’s been worrying me in my household.” He tugged at his full gray beard thoughtfully. “As you know, ours is a bachelor house—one grandfather, two grown sons and two small boys. And we’re sorely in need of a woman’s hand. Oh, we cook and clean and try to keep things in order, but everyone knows a good woman is the heart of any home.”

Unconsciously, she clasped her hands together and tried to think of what she would say if he asked to walk out with her. A few months ago, he’d asked her twenty-nine-year-old widowed friend, Ruthie.

“You’re what, Ellen? Two and thirty?”

“Thirty-three,” she said softly.

“Jah, thirty-three. Almost three years younger than my Neziah.” He fixed her with a level gaze. “You should have married long ago, girl. You should be a mother with a home of your own.”

“My parents...” she mumbled. “They’ve needed help, and—”

“Your devotion to your mother and father is admirable,” he interrupted. “But in time, they’ll both be gathered to the Lord, and you’ll be left alone. And if you wait too long, you’ll have no children to care for you in your old age.”

Her mouth went dry. What Simeon was saying was true. A truth she tried not to think about. It wasn’t that she hadn’t once dreamed of having a husband and children, simply that the time had never been right and the right man had never asked her. She’d had her courting days once, but her father had gotten ill and then there was the fire...and the years had simply gotten away from her. She believed that God had a plan for her, but her life seemed whole and happy as it was. If she never married, would it be such a tragedy?

“I’ve long prayed over my own sons’ dilemma,” Simeon confided as he loosened the reins and flicked them over Butterscotch’s back to urge him on faster. “Neither one is married now, and both would be the happier if they were. So I’ve prayed and waited for an answer, and it seems to me that the Lord has made clear to me what must be done.”

Ellen turned to him. “He has?”

Simeon turned the full force of his winning smile on her. “You should marry one of them.” He didn’t wait for her to respond. “It makes perfect sense. My land and your father’s are side by side. Most of his is wooded with fine old hardwood, and we make our living by the lumber mill. I’ve known you since you were a babe in arms, and there’s no young woman I’d more willingly welcome into our family.”

She, who never was at a loss for words, was almost speechless. “I...” She stopped and started again. She couldn’t help but stare at Simeon. “You think I should marry Neziah or Micah?”

“Not only think it, but am certain of it. I already told them both at breakfast this morning.” He narrowed his gaze. “Now I expect you to be honest with me, Ellen. Do you have any objection to either of them for reason of character or religious faith?”

She shook her head as the images of handsome, young, blond Micah and serious, dark-haired Neziah rose in her mind’s eye. “Nay, of course not. They’re both men of solid faith, but—”

“Goot,” he pronounced, “because I don’t know which the Lord intends for you. I’ve told both of my sons that I expect each of them to pay court to you and make a match as soon as may be decently arranged. The choice between them will be yours, Ellen. Steady Neziah and his children or my rascally, young Micah.” He gazed out over the pony with a sly smile. “And I care not which one you take.”

* * *

It was an hour later at the craft store when Ellen was finally able to share her morning adventure with Dinah Plank, the widow who helped in the shop and lived in the apartment upstairs. Dinah, a plump, five-foot-nothing whirlwind of gray-haired energy, was a dear friend, and Ellen valued her opinion.

“So, Simeon came right out and told you that you should marry one of his sons?” Dinah paused in rearranging the display of organic cotton baby clothing and looked at her intently through wire-framed eyeglasses. “Acting as his sons’ go-between, is he?”

“So it seems.” Ellen stood with an empty cardboard box under each arm. She had two orders to pack for mailing, and she wanted to get them ready for UPS.

“What did you tell him?” The older woman shook out a tiny white infant’s cap and carefully brushed the wrinkles out of it. Light poured in through the nine-paned windows, laying patterns of sunlight across the wide-plank floor of the display room and bouncing off the whitewashed plaster walls.

“Nothing, really. I was so surprised, I didn’t know what to say.” She put the mailing boxes on the counter and reached underneath for a couple of pieces of brown-paper wrapping. “I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. They’ve been such goot neighbors, and of course, my dat and Simeon are fast friends.”

“You think Simeon has already said something to your father?”

“I can’t imagine he did.” She lined the first cardboard box with two pieces of brown paper. “Dat would have certainly said something.”

Dinah propped up a cloth Amish doll, sewn in the old-fashioned way, without facial features. The doll was dressed for Sunday services with a black bonnet and cape, long black stockings and conservative leather shoes. “Well, you’re not averse to marrying, are you?”

“Nay. Of course not.” She reached for the stack of patchwork-quilt-style placemats she was shipping. “I’m just waiting for the man God wants for me.”

“And you’ll know him how?” She rested one hand on her hip. “Will this man knock on your door?”

Ellen frowned and added another layer of brown paper to the box before adding eight cloth napkins.

“My marriage to Mose was arranged by my uncle, and it worked out well for both of us.” Dinah tilted her head to one side in a way she had about her when she was trying to convey some meaning that she didn’t want to state outright. “We each had a few burrs that needed rubbing off by time and trial and error, but we started with respect and a common need. I wanted a home and marriage with a man of my faith, and Mose needed sons to help on his farm.”

Ellen nodded. She’d heard this story more than once, how Dinah and Mose had married after only meeting twice, and how she’d left Ohio to come to Lancaster County with him. The marriage had lasted thirty-four years, and Dinah had given him four sons and three daughters. Most lived nearby, and any of her children would have welcomed Dinah into their home. But she liked her independence and chose to live alone here in the apartment in Honeysuckle, and earn a living helping with the craft shop.

“I was an orphan without land or dowry,” Dinah continued, fiddling with the doll’s black bonnet. “And few ever called me fair of face. But I was strong, and God had given me health and ambition. I knew that I could learn to love the man I married. Mose was no looker, either, but he owned fifty acres of rich ground and was a respected farrier. Together, with the help of neighbors, we built a house with our own hands and backs.”

“And were you happy?”

Dinah smiled, a little sadly. “Jah, we were very happy together. Mose was an able provider and he worked hard. Respect became friendship and then partnership, and...somewhere along the way, we fell in love.” She tapped the shelf with her hand. “So my point of this long story is that Mose didn’t come knocking on my door. Our marriage was more or less arranged.”

Ellen sighed and smoothed the denim blue napkins. “But it sounds so much like a business transaction—Simeon deciding that his sons need wives and then telling them who they should court. Me living next door, so I’m the nearest solution. If one of them wanted to walk out with me, why didn’t he say so, instead of waiting for their father to make the suggestion?”

Ellen sank onto a three-legged wooden stool carved and painted with a pattern of intertwined hearts and vines. She glanced around the room, thinking as she always did, how much she loved this old building. It had started life nearly two hundred years earlier as a private home and had been in turn a tavern, a general store, a bakery and now Beachey’s Craft Shop.

“Maybe you should have married when you had the chance.”

“I wasn’t ready,” she said. “And you know there were other reasons, things we couldn’t work out.”

“With Neziah, you mean?” Dinah passed.

Ellen nodded. She was as shocked by Simeon’s idea that she should consider Neziah again, as she was by the whole idea that he should tell her or his boys who they should marry.

“That was years ago, girl. You were hardly out of your teens, and as hardheaded as Neziah. Are you certain you’re not looking for someone that you’ve dreamed up in your head, a make-believe man instead of a flesh-and-blood one?” The sleigh bells over the front door jingled, indicating a visitor.

Ellen rose.

Dinah waved her away. “I’ll see to her. You finish up packaging those orders. Then you might put the kettle on. If it’s pondering you need, there’s nothing like a cup of tea to make the studying on it easier.”

“Maybe,” Ellen conceded.

Dinah shrugged. “One thing you can be glad of.”

“What’s that?”

“That old goat Simeon wasn’t asking to court you himself.” She rolled her eyes. “Thirty-odd years difference between you or not, he wouldn’t be the first old man looking for a fine young wife.”

“Dinah!” she admonished. “How could you say such a thing?”

Dinah chuckled. “I said it, but you can’t tell me you weren’t thinking it.”

“I suppose Simeon is a good catch, though a little too old for me.” Ellen glanced up, smiling mischievously. “Maybe you’re the one who should think about courting one of the Shetler bachelors.”

Dinah laughed as she walked away. “Maybe I should.”

Chapter Two (#ulink_155288ae-39c7-577e-9843-c3997b0c7d1a)

That afternoon Ellen walked her scooter up the steep driveway to her house. “Start each day as you mean to go,” her father always said. And today surely proved that wisdom. She hadn’t reached the craft shop until past her usual hour that morning, and now she was late arriving home. She left the scooter in the shed in a place where the chickens wouldn’t roost on it, and hurried toward the kitchen door.

Ellen had left chicken potpie for supper. On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, the days that she closed the store at five, she and her parents usually had their main meal together when she got home. It was after six now, though. She hoped they hadn’t waited for her.

Ellen had been delayed because of a mix-up with the customer orders that Dinah had packed and mailed a week earlier. The reproduction spinning wheel that had been intended for Mrs. McIver in Maine had gone instead to Mrs. Chou in New Jersey. And the baby quilt in the log cabin pattern and an Amish baby doll Mrs. Chou had been expecting had gone to Mrs. McIver. Mrs. Chou had taken the mistake with good humor when Ellen had called her from the store’s phone. Mrs. McIver hadn’t been so understanding, but Ellen had been able to calm her by promising to have the spinning wheel shipped overnight as soon as she received it back from Mrs. Chou.

Dinah felt terrible about the mix-up; unfortunately, it wasn’t the first time she’d made a mistake shipping an order. Dinah was a lovely woman, but other than her charming way with tourists who came into the shop, her shopkeeper’s skills were not the best. After two years behind the counter, she still struggled running credit cards, the cash register continually gave her a fit and Ellen had given up trying to get her to make the bank deposits. But Dinah needed the income, and since the fire, it had been comforting to have someone living in the apartment upstairs. So, in spite of the disadvantages of having Dinah as an employee, Ellen and her father agreed to keep her as long as she was willing to work for them.

As Ellen climbed the back steps to her parents’ house, voices drifted through the screen door, alerting her that they had visitors. And since they were speaking in Deitsch, they had to be Amish. But who would be stopping by at suppertime?

Ellen walked into the kitchen to find Simeon Shetler, his two sons and his two grandsons seated around the big table. The evening meal was about to be served.

Ellen covered her surprise with a smile. “Simeon. Micah. Neziah. How nice to see you.” The table was set for eight, so clearly the Shetlers had been expected. Had her mother invited them for supper and forgotten to mention it? It was entirely possible; there were many things that slipped Mary Beachey’s mind these days.

Of course, there was the distinct possibility that plans to have dinner together had been made after her conversation with Simeon this morning. Ellen’s cheeks grew warm. Surely Micah and Neziah weren’t here to—

The brothers got to their feet as Ellen entered the kitchen, and she saw that they were both wearing white shirts and black vests and trousers, their go-to-worship attire—which meant that the visit was a formal one. For them, not their father. Simeon wore his customary blue work shirt and blue denim trousers.

It appeared that the two younger Shetler men had come courting.

She opened her mouth to say something, anything, but nothing clever came to her, so she looked at her father. Surely there had been a misunderstanding or miscommunication with the Shetlers. Surely her father would have wanted to talk in private with Ellen about Simeon’s proposition before inviting them all to sit down together to talk about it.

John Beachey met his daughter’s gaze and nodded. He knew her all too well. He knew just what she was thinking. “Jah, Ellen. We’ve talked, Simeon and I.”

“You have?” she managed.

“We have, and we’re in agreement. It’s time you were married, and who better than one of the fine sons of our good neighbor. A neighbor, who,” he reminded pointedly, “helped us out so much when we had the fire.”

The fire, Ellen thought. That weighty debt: rarely mentioned but always remembered.

How many years ago had it been now? Seven or eight? The suspicious fire, probably caused by teenaged mischief makers, had started at the back of the store and quickly spread through the old kitchen and up through the ceiling into the second floor. Quick-thinking neighbors had smelled smoke and seen flames, and the valiant efforts of a local fire company had prevented the whole building from being a loss. But smoke and water had destroyed all of the contents of the shop, leaving them with no means of support and no money to rebuild. Simeon had showed up early the next day with a volunteer work force from the community to help. He’d provided cash from his own pocket for expenses, lumber from his mill and his sons’ services to provide the skilled carpentry to restore the shop. Over the years, her father had been able to repay Simeon’s interest-free loan, but they owed the Shetlers more than words could ever express.

“Sit, please.” She waved a hand to the men and boys.

Having Simeon’s sons standing there grinning at her was unnerving. Or at least, handsome, blond-haired Micah was grinning at her. Neziah, always the most serious of the three Shetler men, had the expression of one with a painful tooth, about to see the dentist. He nodded and settled solidly in his chair.

The room positively crackled with awkwardness, and Ellen wished she were anywhere but there. She wished she could run outside, jump on her push scooter and escape down the drive. Everyone was looking at her, seeming to be waiting for her to say something.

Neziah’s son Joel, age five, came to her rescue. “Can we eat now, Dat? I’m hungry.”

“Jah, I’m hungry, too,” the four-year-old, Asa, echoed.

The boys did not look hungry, although boys always were, Ellen supposed. Joel, especially, appeared as if he’d just rolled away from a harvest table. His chubby face was as round as a donut under a mop of unruly butter-yellow hair, hair the same color as his uncle Micah’s. Asa, with dark hair and a complexion like his father’s, was tall for his age and sturdy. Someone had made an effort to subdue their ragged bowl cuts and scrub their hands and faces, but they retained the look of plump little banty roosters who’d just lost a barnyard squabble and were missing a few feathers. Still, the boys had changed the focus from her and the looming courtship question back to ground she was far steadier on—the evening meal.

“We waited supper for you,” Ellen’s mother explained. “Come, Dochter, sit here across from Micah and Neziah.”

Ellen surveyed the table. There would be enough of a main dish for their company because she’d made the two potpies. She also saw that her mother had fried up a platter of crispy brown scrapple and brought out the remnants of a roasted turkey. “Let me open a jar of applesauce and some of those delicious beets you made this summer, Mam,” she suggested. As she turned toward the cupboard, she took off her good apron, which she wore at the shop, and grabbed a black work apron from a peg on the wall. “I’ll only be a moment,” she said. “I’m sure the boys like applesauce.” Tying the apron on, she retrieved the jar and carried it to the table.

“Do you have pie?” Joel called after her. “Grossdaddi promised we would have pie. He said you always got pie.”

“And cake,” Asa chimed in.

“Boys,” Neziah chided. “Mind your manners.”

“But Grossdaddi said,” Joel insisted.

Ellen went to the stove and scooped biscuits from a baking sheet and dropped them into a wooden bowl that had been passed down from a great-grandmother. They were still warm, so they must have just come from the oven.

Her mother rose to seek out a pint of chow-chow, and a quart of sweet pickles that they’d put up just a week ago. In no time, they were all seated, and Ellen’s father bowed his head for the silent prayer.

When Ellen looked up once prayer was over, Micah met her gaze, grinning. He seemed to be enjoying the whole uncomfortable situation. But as she started to pass the platters and bowls of food, she found herself smiling, as well. Having friends at the table was always a blessing. She might not have expected to find the Shetlers here this evening, but here they were, and she’d make the best of it. So what if they were there to talk about a possible courtship between her and one of the Shetler men? No one was going to make her marry anyone.

Shared meals were one of the joys of a Plain life, and it was impossible not to enjoy Simeon and Micah’s teasing banter. The children concentrated on devouring their supper, eating far more than Ellen would suppose small boys could consume. Unlike Micah, Neziah ate in silence, adding only an occasional Jah and a grunt or nod of agreement to the general conversation. Neziah had always been the quiet one, even as a child. How he could have such noisy and mischievous children, Ellen couldn’t imagine.

Simeon launched into a lengthy joke about a lost English tourist who stopped to ask an Amish farmer for directions to Lancaster. The story had bounced around the community for several years, but Simeon had a way of making each tall tale his own, and Ellen didn’t mind. At least when he was talking, she didn’t have to think of something to say to either of her would-be suitors.

Joel looked up from his plate, waved his fork and asked, “Now can we have pie?”

“Rooich,” Micah cautioned, raising a finger to his lips. Quiet. He then pointed his finger in warning to keep Asa from chiming in.

Ellen glanced at Neziah to see his reaction to his brother chastising his boys, but Neziah’s mouth was full of potpie and he seemed to be paying no mind. It was his third helping. She was glad she’d made two large pies, because the first dish was empty and the second held only a single slice.

Neziah suddenly began to cough and Micah slapped him on the back. Neziah reddened and turned away from the table. His brother handed him a glass of milk, and Neziah downed half of it before clearing his throat and wiping his mouth with a napkin. “Sorry,” he gasped, turning back to the table. “Chicken bone.”

Ellen blushed with embarrassment. “I’m sorry,” she said hastily. She’d been so certain that she’d gotten all the bones out of the chicken before adding it to the other ingredients.

“I may be a dumb country pig farmer,” Simeon said, delivering the punch line of his story, “but I’m not the one who’s lost.” He looked around, waiting for the reaction to his joke and wasn’t disappointed.

Her mam and dat laughed loudly.

“Jah,” her mother agreed. “He wasn’t, was he? It was the fancy Englisher with the big car who was lost.”

Simeon slapped both hands on the table and roared with delight. “Told him, didn’t he?” Tears ran down his cheeks. “Lot of truth in that story, isn’t there?”

Ellen’s father nodded. “Lot of truth. Not many weeks pass that some tourist doesn’t stop in the craft shop to ask how to find Lancaster. And I say, you’re standing in it.”

“Course he means the town,” Ellen’s mam clarified. “Lancaster County’s one thing, the town is another.”

“Town of Lancaster’s got too many traffic lights and shopping centers for me.” Simeon wiped his cheeks with his napkin. “But I do love to laugh at them Englishers.”

Joel wiggled in his chair and whined. “I want my pie. Grossdaddi, you promised there’d be pie for dessert.”

Ellen eyed the two little boys. Asa and Joel were unusually demanding for Amish children; some might even say they were spoiled. And, to her way of thinking, Joel’s father allowed him perhaps too many sweets. He was a nice boy when he wasn’t whining, but if he got any chubbier, he’d never be able to keep up with the other kids when they ran and played. If he were her child, he’d eat more apples and fewer sugary treats. But, as her mam liked to say, people without kids always had the most opinions on how to raise them.

“Enough, boys!” Neziah said, clearly embarrassed by their behavior. “You’ll have to forgive my children. Living rough with us three men, they’re lacking in table manners.”

Micah chuckled.

Since he was still unmarried, he didn’t have a beard. The dimple on his chin made him even more attractive when he laughed. Ellen couldn’t imagine what he would want with her when half the girls in Lancaster County wished he’d ask to drive them home from a Sunday night singing.

“It’s more than table manners, I’d say,” Micah teased. “These boys are wild as rabbits and just as hard to herd when it comes time for bath or bed.”

“Which is why they need a mother’s hand,” Simeon pronounced. “And why we came to ask for your daughter in marriage, John.”

“To one of us,” Micah added. “Your choice, Ellen.” He chuckled again and punched his brother’s shoulder playfully. “Although, if she has her pick, Neziah’s starting this race a good furlong behind.”

Ellen glanced at Micah. Self-pride wasn’t an attribute prized by the Plain folk. Everyone knew that Micah was full of himself, but still, with his likeable manner, he seemed to be able to get away with it.

And to prove it, he winked at her and grinned. “Tell the bishop I said that, and he’ll have me on the boards in front of the church asking for forgiveness for my brash talk.”

“Micah! What will the John Beacheys think of you with your nonsense?” Simeon asked. “Be serious for once. Your brother is as good a candidate for marriage as you. And Ellen would be a good wife for him, as well.” He shrugged. “Either way, we’ll have a woman in the house to set it right and put my grandsons’ feet on the narrow path.”

Ellen frowned, not liking the sound of that. Did the Shetlers want her, or just some woman to wash, cook and look after the children? Maybe it was true that she was getting too old to be picky, but she wouldn’t allow herself to be taken advantage of.

She glanced at the plate of food she’d barely touched. She couldn’t believe they were all sitting there seriously talking about her marrying one of the Shetlers.

The kitchen felt unusually warm, even for a late-August evening, and Ellen ran a finger under the neckline of her dress to ease the tightness against her skin. What could she say? Her parents and the Shetlers were all looking expectantly at her again.

Folding his arms over his chest, Neziah spoke with slow deliberation. “You’re telling Ellen that she should choose between us, but I’ve not heard her say that she’ll have either of us. This is your idea, Vadder. Maybe it’s not to Ellen’s liking.”

“Not just my idea,” Simeon corrected. “Nay. I say plainly that I believe it’s God’s plan. And John’s in agreement with me. Think about it. I don’t know why we didn’t see it before. Here I sit with two unwed sons, one with motherless children he struggles to care for and the other sashaying back and forth across the county from one singing to another in a rigged-out buggy with red-and-blue flashing lights.” His brow furrowed as he stared hard at Micah. “And don’t mention rumspringa, because it’s time you put that behind you and came into the church.”

“Listen to your father.” Ellen’s dat nodded. “He’s speaking truth, Micah. He wants what’s best for you. He always has.”

“Jah,” Simeon said. “I’ve held my tongue far too long, waiting for the two of you to stop sitting on the fence and court some young woman. Neziah’s mourned the boys’ mother long enough, and Micah’s near to being thought too flighty for any good family to want him. It’s time.”

Micah toyed with his fork. “I’m not yet thirty, Vadder. It’s not as if no girl would have me.”

“I’ll fetch the coffee and apple pie,” Ellen offered. She began clearing away the plates while Simeon wagged a finger at Micah.

“You know I’m but speaking what’s true. Deny it if you can. Neither of you have been putting your minds to finding a good wife. And you must marry. It’s not decent that you don’t. I’ve talked to you until I’m blue in the face, and I’ve prayed on it. What came to me was that we didn’t have to look far to find the answer to at least one of our problems.”

“Jah.” Ellen’s mother leaned forward on her elbows and pushed back her plate. “And you’ve worried about your sons no more than I’ve lost sleep over our girl. She should have been a wife years ago, should have filled our house with grandchildren. She’s a good daughter, a blessing to us in our old age. But it’s time she found a husband, and none better than one of your boys.”

“I agree,” Ellen’s father said. “I’ve known Neziah and Micah since they were born. I could ask no more for her than she wed such a good man as either of them.” He smiled and nodded his approval. “The pity is, we didn’t think of this solution sooner.”

“No solution if Ellen’s not willing,” Neziah pronounced. His serious gaze met hers and held it. “Are you in favor of this plan or are you just afraid to speak up and turn us out the door with our hats in hand?”

Everyone looked at her again, including the two children, and Ellen felt a familiar sinking feeling. What did she want? She didn’t know. She stood in the center of the kitchen feeling foolish and clutching the pie like a drowning woman with a lifeline. “I...Well...”

“Is the thought of marrying one of us distasteful to you?” Neziah asked when she couldn’t answer.

He had none of the showy looks of his brother. Neziah’s face was too planed, his brow too pronounced, and his mouth too thin to be called handsome. Not that he was ugly; he wasn’t that. But there was always something unnerving about his dark, penetrating gaze.

Neziah was only three years older than she was, but he looked closer to ten. Hints of gray were beginning to tint his walnut-brown hair. The sudden loss of his wife and mother in the same accident three years ago had struck him hard. Maybe it was the responsibility of being both father and mother to two young children that stamped him with an air of heaviness.

“We’re all friends here,” Neziah continued. “No one will think less of you if this isn’t something you want to consider.”

Micah relaxed in his chair. “I say we’ve thrown this at her too fast. I wouldn’t blame her for balking.” He met Ellen’s gaze. “Give yourself a few days to think it over, Ellen. What do you say?”

“Jah,” Ellen’s mother urged, rising to take the pie from her hands. “Say you will think about it, daughter.”

“You know your mother and I wouldn’t even consider the idea if we thought it was wrong for you.” Her father beamed, and Ellen’s resistance melted.

What could be wrong with thinking it over? As Simeon and her dat had said, either of the Shetler brothers would make a respectable husband. She would be a wife, a woman with her own home to manage, possibly children. She took a deep breath, feeling as if she were about to take a plunge off the edge of a rock quarry into deep water far below. She actually felt a little lightheaded. “I will,” she said. “I’ll think on the whole idea, and I will pray about it. Surely, if it is the Lord’s plan for me, He’ll ease my mind.” She held up her finger. “But my agreement is to think on the whole idea. Nothing more.”

Simeon smacked his hands together. “Goot. It is for the best. You will come to realize this. And whichever one you pick, I will consider you the daughter I never had.”

Ellen turned toward Simeon, intent on making it clear to her neighbor that she hadn’t agreed to walk out with either of his sons when the little boys kicked up a commotion.

“Me!” Asa and Joel both reached for the pie in the center of the table. “Me!” they cried in unison.

“Me first!” Joel insisted.

“Nay! Me!” Asa bellowed.

“I knew you’d see it our way, Ellen,” Micah said above the voices of his nephews. He rose from his chair. “I was so sure you’d agree that I brought fishing poles. You always used to like fishing. Maybe you and me could wander down to the creek and see if we could catch a fish or two before dark.”

Ellen looked at Micah, then the table of seated guests, flustered. “Go fishing? Now?”

“Oh, go on, Ellen,” her father urged. “We can get our own pie and I’ll help your mother clean up the dishes.” He glanced at Micah. “Smart thinking. Best strike while the iron is hot, boy. Get the jump on Neziah and put your claim in first.”

Mischief gleamed in Micah’s blue eyes. “It’ll get you out of here.” He motioned toward the back door. “Come on, Ellen. You know you want to. I’ll even bait the hook for you.”

She cut her eyes at him. “As if I need the help. If I remember correctly, it was me who taught you how to tickle trout.”

“She did,” Micah conceded to the others, then he returned his attention to her. “But I’ve learned a few things about fishing since then. You don’t stand a chance of catching the first fish or the most.”

“Don’t I?” Ellen retorted. “Talk’s cheap but it never put fish on the table.” Still bantering with him, she took off her kapp, tied on her scarf and followed him out of the house.

* * *

Fifteen minutes later, Micah stepped out on a big willow that had fallen into the creek. The leaves had long since withered, but the trunk was strong. Barring a flood, the willow would provide a sturdy seat for fishermen for years. And the eddy in the curve of the bank was the best place to catch fish.

He turned and offered Ellen his hand. “Don’t worry,” he said, “it’s safe enough.” He had both fishing poles in his free hand, while Ellen carried the can with the bait.

The rocky stream was wide, the current gentle but steady as the water snaked through a wooded hollow that divided his father’s farm from her dat’s. When they were children, he, Neziah and Ellen had come here to fish often. Now, he sometimes brought his nephews, Joel and Asa, but Neziah didn’t have the time. Sometimes the fishing was good, and sometimes he went home with nothing more than an easy heart, but it didn’t matter. Micah thought there was often more of God’s peace to be found here in the quiet of wind and water and swaying trees than in the bishop’s sermons.

“Thanks for asking me to come fishing, Micah,” Ellen said as she followed him cautiously out onto the wide trunk. “I needed to get out of there, and I couldn’t think of a way to make a clean getaway without offending anyone.”

“Jah,” Micah agreed. “I wanted to get away, too. Not from supper. That was great. But my dat. When he takes a crazy notion, he’s hard to rein in.”

“So you think that’s what it is? His idea that you and Neziah should both court me, and that I would choose between you? It’s a crazynotion?”

The hairs on the back of Micah’s neck prickled, warning him that he’d almost made a big misstep, and not the kind that would land him in the creek. “Nay, I didn’t mean it like that. It’s a good idea, one I should have come up with a long time ago. Me and you walking out together, I mean, not you picking one of us. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it. My vadder is right that I’ve been rumspringa too long. I didn’t want to discuss it back there, but I’ve been talking to the bishop about getting baptized. I’m ready to settle down, and a good woman is just what I need.”

Ellen sat down on the log and dangled her legs over the edge. She was barefooted, and he couldn’t help noticing her slender, high-arched feet. “I’m nearly four years older than you,” she said.

He grinned at her. “That hasn’t mattered since I left school and started doing a man’s work. I’ve always thought you were one of the prettiest girls around, and we’ve always gotten along.” Maybe not the prettiest, he thought, being honest with himself, but Ellen was nearly as tall as he was and very attractive. She’d always been fun to be with, and she was exactly the kind of woman he’d always expected to marry when he settled down. Ellen never made a fellow feel like less than he was, always better. Being with her always made him content...sort of like this creek, he decided.

“And our fathers’ lands run together, of course.” She took the pole he offered and bent over her line, carefully threading a night crawler onto the hook. “Handy for pasturing livestock.”

He studied her to see if she was serious or testing him, but she kept her eyes averted, and he couldn’t tell. He decided to play it safe. “We’ve been friends since we were kids. We share a faith and a community. Maybe that’s a good start for a marriage.”

“Maybe.” She cast her line out, and the current caught her blue-and-white bobber and whisked it merrily along.

“Dat says all the best marriages start with friendship,” he added.

“And it doesn’t bother you that I’m thirty-three and not twenty-three?”

“Would I be here if it did?” Now she did raise her head and meet his gaze, and he smiled at her. “It was my vadder’s idea, but I wouldn’t have agreed if I didn’t think it was something I wanted to do. You’re a hard worker. I hope you think the same of me. I’ve got a good trade, and I own thirty acres of cleared farmland in my own name. And the two of us have a lot in common.”

“Such as?”

“I like to eat and you’re a good cook.” He laughed.

She smiled.

“Seriously, Ellen. You get my jokes. We both like to laugh and have a good time. You know it’s true. There’s a big difference between me and Neziah.”

“He has always been serious in nature.”

“And more so since the accident. He doesn’t take the joy in life that he should. Bad things happen. I didn’t lose a wife, I know, but I lost my mother in that accident. You have to go on living. Otherwise, we waste what the Lord has given us.”

She nodded, but she didn’t speak, and he remembered that he’d always liked that about her. Ellen was a good listener, someone you could share important thoughts with.

“Sometimes I think my brother’s meant to be a preacher, or maybe a deacon. He’s way too settled for a man his age. Just look at his driving animal. I always thought you could tell a man’s nature by his favorite driving animal.”

“Neziah drives a good mule,” she suggested.

“Exactly. Steady in traffic. Strong and levelheaded, even docile. An old woman’s horse.” It was no secret that he was different than Neziah. He liked spirited horses and was given to racing other buggies on the way to Sunday worship, not something that the elders smiled on.

“Don’t be so hard on your brother,” Ellen defended. “He has his children’s safety to think about. You know how some of these Englishers drive. They don’t think about how dangerous it is to pass our buggies on these narrow roads.”

“Jah, I know, but I’m careful about when and where I race. I don’t mean to criticize Neziah. He’s a good man, and I’d not stand to hear anyone criticize him. But he’s too staid for you. Remember that time we all went to Hershey Park? You and me, we liked the fast rides. Neziah, he got sick to his stomach. We’re better suited, and if you’ll give me a chance, I’ll prove it to you.”

“I think I—” She sounded excited for a second then sighed. “I had a bite but I think the fish is playing with me.” She reeled in her line and checked the bait. Half of her worm was missing. “Look at that. Now I’ll have to put on fresh bait.”

He steadied himself against a branch and watched her, wondering why it had taken his father’s lecture to stir him into action. For years he’d been going to all the young people’s frolics, flirting with this girl and that, when all the time he’d hardly noticed Ellen. He had seen her, of course, gone to church with her, worked on community projects with her, eaten at her father’s table and welcomed her to his own home. But he hadn’t thought of her in the way he suddenly did now, as a special woman whom he might want to make his wife. The thought warmed him and made him smile. “You don’t think I’m too young for you, do you?” he asked.

“Nay,” she said, taking her time to answer. “I suppose not. But it’s a new idea for me, that I marry a friend, rather than someone I was in love with.”

Micah felt a rush of pleasure. “How do we know we won’t discover love for each other if we don’t give ourselves the chance?”

Her dark eyes grew luminous. Her bobber jerked and then dove beneath the surface of the creek, but Ellen didn’t seem to notice the tension on her fishing pole. “You think that could happen?”

He grinned. “I think that there’s a very good possibility that that’s exactly what might happen.”

Chapter Three (#ulink_39ed9dd8-4cf0-5335-8d02-cfc834832562)

They walked back to her lane just as twilight was falling over the farm fields. “Danki, Micah,” Ellen said. “The fishing was fun. I’d forgotten how much I liked it.”

Her first moments alone with him, when they’d left the house, had been awkward. But then they’d fallen back into the easy rhythm of their younger days with none of the clumsiness of the situation that she’d feared. Being so comfortable with Micah made her wonder if maybe they could be happy together. What if Micah was whom God had intended for her all along?

“You should take these,” he said, holding a string of three perch.

“You caught two of them. Don’t you want to take them home to fry for breakfast?”

He still held them out. “Three measly fish for the five of us? Not worth the trouble of cleaning and cooking them. No, you’d best take them.”

“Danki for the fish, too, then. Dat loves fried fish for breakfast.”

“You’re welcome. And you are going to think about walking out with me,” Micah reminded. “Right?” He stood there, fishing poles in hand, smiling at her and completely at ease.

“Jah, I will.” She smiled at him. “God give you a restful sleep.”

“And you, Ellen.” He used no courting endearments, but she liked the way he said her name, and she felt a warm glow inside as she savored it. She didn’t want to spoil the feeling and was afraid that he might linger, might want to sit with her on the porch or stay on after her parents had gone to bed. Instead, he bestowed a final grin and strode off whistling in the direction of his own home.

Ellen walked slowly up the driveway and through her father’s barnyard, inhaling deep of the scent of her mother’s climbing roses and the honeysuckle that grew wild along the edge of the hedgerow. She drank in the peace of the coming night. Crickets and frogs called their familiar sounds, and evening shadows draped over the barnyard, easing her feelings of indecision. How wonderful life is, she thought. You expect each day to be like the one before, but the wonder of God’s grace was that you never really knew from one hour to another what would come next.

A single propane lamp glowed through the kitchen window, but the house was quiet. Simeon, Neziah and the boys had left. The only sign of movement was a calico cat nursing kittens near the back door. But the light meant that her parents were still up. Her father was too fearful of fire to retire and leave a lamp burning. Ellen stepped inside, the string of fish dangling from her finger. “Mam?” she called softly. “Dat?”

“Out here.” Her father’s voice came from the front of the house.

Their home was small as Amish homes went, but comfortable. When her father and his neighbors had built it, he and her mother were already past the age when they expected to be blessed with children. A big kitchen, a pantry, a living room, bath and two bedrooms comprised the entire downstairs. Her room was upstairs in an oversize, cheerful chamber with two dormer windows and a casement window that opened wide to let in fresh breezes from the west. She also had a small bath all to herself, a privacy that few Amish girls had. Growing up, her girlfriends, most from large families, had admired the luxury, but she would have gladly traded the cheerful room with its yellow trim, clean white claw-foot tub, fixtures and tiny shuttered window for a bevy of noisy sisters crowded head to foot in her bedroom.

The double door near the staircase stood open, and her father called again to her from the front porch. “Come, join us. And bring another bowl for beans.”

Butter beans, Ellen thought. The family often sat on the porch in the evenings this time of year and shelled butter beans. She and her mother canned bushels of beans for winter. Quarts of the beans already stood in neat rows in the pantry beside those of squash, English peas, string beans, corn, tomatoes and pickles. She wrapped the fish in some parchment paper and put it in the propane-run refrigerator. They’d keep until morning when she or her father would clean them. She washed her hands, found a bowl and carried it out to the porch. Her parents sat side by side in wooden rocking chairs, baskets of lima bean hulls and bowls of shelled beans around them.

“Catch any fish?” her father asked.

“In the fridge. If you clean them, I’ll fry them up for our breakfast.” Ellen took the chair on the other side of him. Her chair. Her mother sat still, her chin resting on her chest; she was snoring lightly. Her mother often drifted off to sleep in the afternoon and early evening. She didn’t have the vigor that Ellen was used to, and she worried about her. “Has she been asleep long?”

“Just a little while. Company wore her out.” He dumped butter beans still in their shells into Ellen’s bowl. “Course, you know how she loves to have people come. And she adores children, even those rascals of Neziah’s. Nothing makes her happier than stuffing a child with food, unless it’s singing in church. Your mother always had the sweetest voice. It was what drew me to her when we were young.”

Ellen nodded and smiled. She knew what her father was up to. They were so close that she was familiar with all his tricks. He was deliberately being sentimental about her mother to keep Ellen from talking about what she’d sought him out for. He knew that she was unhappy with the ambush that had happened at supper, and he wanted to avoid the consequences. But she suspected that he’d be disappointed if she let him get away with it, so she went straight to the heart of the pudding.

“You shouldn’t have asked the Shetlers here for supper to talk about this courting business without talking to me first,” she admonished gently. “I can’t believe you didn’t wait to see whether I was in favor of this or not.”

“Ach...ach, I was afraid you’d be vexed with me. I told your mother you would.” He gestured with his hand. “But it is such a good solution to Simeon’s problem and ours. And how could I refuse him? He came to me at midday, told me what was on his mind and said that he’d already approached you with the idea and you were in favor. Then he invited himself and his sons to supper.” He shrugged as if to say, what could I do? “He’s a good neighbor and an old friend.”

“Friends or not, I’m your daughter, and who I will or won’t marry is a serious matter. If you knew I wouldn’t approve, you shouldn’t have done it,” she said, unwilling to surrender so easily to being manipulated.

She had the greatest respect for her father’s judgment, but he’d always fostered independence in her. Even at a young age, he’d treated her more as another adult in the home than as a child. Maybe it was because her mother had always been an uncomplicated and basic person, content to allow her husband and the elders of the church to make decisions for her, while his was a keener mind that sought in-depth conversation. Or perhaps it was because she’d been the only child and he doted on her.

In any case, the Bible said “Honor thy father and mother,” and she hoped she hadn’t taken advantage of his leniency. She’d taken care not to be forward in front of others, especially with the more conservative of the community. But here, in their own home, with none but him to hear, how could she do less than protest his high-handedness?

“What was I to say to Simeon?” he went on. ‘“Nay, old friend, you can’t come to share bread with us until I see if my daughter wants to marry either one of your boys?’” He found a withered lima bean and cast it to the brown-and-white rat terrier sitting at his feet. Gilly caught the bean in the air and chomped it joyfully.

“It was a shock to see Micah and Neziah all dressed in their best, here at the table.” Ellen glanced at her mother, but she snored on, her hands loose in her lap, her bowl of unshelled beans hardly started. “She was good tonight, don’t you think?” she said, waffling by talking of something easier. “Her morning started bad, so I worried...”

Her father’s face was lost in shadow now, but Ellen knew he was smiling. He had such fondness for her mother, his love seemingly growing stronger with his wife’s slow mental decline. “She perked up when I told her that the children were coming. Buzzed around the kitchen like she was forty. Her biscuits were light enough to float, don’t you think? And she was sharp as a needle at supper.” Her father continued to hull limas, his fingers moving unconsciously without pause. Fat beans dropped by ones, twos and threes into the wide basket in his lap.

“Jah,” Ellen agreed. “No lapses in memory.” And her mother’s biscuits had been good tonight. She’d not forgotten the rising or the salt as she did sometimes. And she hadn’t let them stay in the oven until the bottoms began to burn. Once, not long ago, Ellen had come in from the garden to find the kitchen full of smoke and her mother standing motionless in the center of the room, staring at the stove and coughing. Ellen had had to get the biscuits out of the oven and shoo her mother outside where she could breathe. It was those lapses in judgment that made Ellen apprehensive about her mother’s health.

“So, Dochter, did you enjoy yourself on your outing with young Micah?”

“I did have a good time,” she admitted. “But you know I would have put the Shetlers off if I’d had the choice. This isn’t something that I can decide in a few hours.”

“But you are open to being courted by Micah or his brother?” When she didn’t answer right away, her father pressed on. “You have to marry, Ellen. You know that, don’t you? What will you do when your mother and I go to our reward? We’re not young, either of us. You’re a healthy young woman. You need a family of your own. And it would fill our hearts with joy if you could give us a grandchild before we die.”

She swallowed. Her throat felt tight, as if an invisible hand was squeezing it. It was all perfectly logical, of course, but what about her heart? Her parents had married for love, and she had hoped for the same.

“I’m not asking you to marry either of Simeon’s boys,” he father went on. “I’m only asking that you give them a chance.”

Her gaze met his, but she still didn’t speak.

“Just...just a month. That’s all I ask of you. Give them a month.” He smiled the smile he knew she could never resist. “Is that too much for an old man to ask of his daughter?”

He said it so sweetly that she sighed and looked at the lima bean in her hand. “No, I suppose it’s not too much to ask, so I will walk out with them,” she said softly. “But I’ll tell you now—” she pointed with the empty hull at him “—I’ll only truly consider Micah, not Neziah.”

“Don’t be foolish. You cared for Neziah once. You came close to marrying him.”

She tightened her mouth. “That was a long time ago,” she said. “Marrying Neziah would have been a mistake. We were—are—too different. He isn’t the husband for me, and I’m certainly not the wife for him.” Memories she hadn’t stirred up in years came back to her, and she felt her heart trip. Things had been so complicated with Neziah, and she had been so young. “I’d feel trapped in a marriage with him.”

“Then you’re wise to refuse him.” He leaned closer to her. “But you are open to being courted by Micah?”

She nodded. “Jah. If you think I should do that, I will.”

“And you don’t think it’s being unfair to Neziah to allow him to believe you’re considering his suit?”

“Honestly, Dat, I think he went along with Simeon’s idea just to please his father. I bet he’s trying to figure out at this very moment how to get out of this.”

“Then we will put this all in God’s hands,” her father said. “He’s never failed to be there when we need Him. It pleases me that you are willing to walk out with the Shetler boys, and I will place my hopes and prayers on the best solution for all of us.”

She nodded, her heart suddenly lighter. “I’ll put my trust in Him,” she agreed. And for the first time in years, she allowed herself to think of a different life than she had thought hers would be...one that included a husband, a baby and new possibilities.

* * *

“I’m hungry,” Joel said in Deitsch as Neziah lifted him out of the bathtub and wrapped him in an oversize white towel.

“Jah, me, too,” Asa agreed in Deitsch. “I want milk and cookies. Can we have milk and cookies, Dat?”

“English,” Neziah reminded them. “Bath time is English. Remember? Soon Joel will go to school, and the other children will speak English. You wouldn’t want them to call him a woodenhead, would you?” Asa wriggled out of his grasp and retreated to the far end of the claw-footed porcelain tub. “Come back here, you pollywog.” He captured the escapee and stood him beside his brother. It always surprised him how close they were in size, even though Asa was nearly two years younger. Neziah wrapped his younger son in a clean blue towel and sat him on the closed toilet seat.

The bathroom was large and plain with a white tile floor, white fixtures and white walls and window shutters. Neziah wondered if his boys ever realized how lucky they were not to have to use an outhouse as he had for much of his childhood. He hadn’t minded the spiders and the occasional mouse or bat as much as he had the cold on winter nights. He smiled. This modern bathroom with its deep sink, corner shower and propane heater was a great improvement. The Amish elders might be slow to change, but they did make some concessions to the twenty-first century, and bathrooms, in his opinion, were at the top of the list.

“My tummy hurts,” Joel said in English, sticking out his lower lip. “I have hungry.”

“After the big dinner and all the pie you ate at the Beacheys?” Neziah chuckled. “I don’t think so. You’ll have to wait for breakfast.”

Joel’s face contorted into a full-blown pout, and Asa chimed in. “Me hungry, too.”

“Bed and prayers.” Neziah whisked off the towels and tugged cotton nightshirts over two bobbing heads. “Brush your teeth now, and maybe we’ll have time for a little Family Life before lights out.” Family Life was one of the few publications that came to the house, and Neziah made a practice of reading short stories or poems that he thought his sons might like at bedtime.

“But we’re hungry,” Joel whined, retreating to the Deitsch dialect. “My belly hurts a lot.”

“Then cookies and milk will only make it worse,” Neziah pronounced. He scooped up Asa and draped him laughing over his shoulder and took Joel’s hand. “Bed. Now.” Joel allowed himself to be tugged along reluctantly to the bedroom and the double bed the boys shared. Neziah deposited Asa between the sheets then reached down for Joel.

“Read,” Asa reminded. He pulled the sheet up to his chin and dug his stuffed dog out from under his pillow while Joel wormed his way over his brother and curled up on top of the light cotton blanket and sheet.

A breeze blew through the curtainless windows on the north side of the bedroom. Like the bathroom, this was a sparse chamber: the bed, a bookcase, a table and two chairs. There were no dressers. The boys’ clothing was all hung inside the single, small closet. Neziah pulled up a chair, lit the propane lamp and together they shared a short prayer. Then he took the latest copy of Family Life magazine from the table. He’d read to Joel and Asa every night since their mother had died. It was something she’d always done with the children, and although he wasn’t as much at ease with reading aloud as Betty had been, he felt it was the right thing to do.

Strangely, the practice, which he’d begun out of a sense of duty, had become the highlight of his day. No matter how tired he was, spending a few moments quietly with his sons brought him deep contentment. Asa, in particular, seemed to enjoy the poetry as much as Neziah did. It wasn’t something that Neziah would have willingly admitted to anyone, but he found the sounds of the rhyming words pleasing. Joel preferred the stories, the longer the better, but Neziah suspected that it was simply a way of delaying bedtime.

Tonight, Neziah chose a short and funny poem about a squirrel that stored up nuts for winter and when he had finished it he said, “Sleep well,” as he bent to rest a hand lightly on each small head. Joel’s hair was light and feathery; Asa’s thick and curly. “God keep you both,” he murmured.

“Dat?”

“Jah, Joel, what is it? No more about cookies tonight.”

“Nay, Dat. I was wondering. Is Ellen going to be our new mutter?”

Neziah was surprised by the question; he had wondered how much his sons had understood from the conversations he and Micah had had with their father and later at the Beacheys’ table. Apparently, they’d caught the gist of it. “I don’t know,” he answered honestly. He made it a point never to be dishonest with his children, not even for their own good. “Maybe. Would you like that?”

“Grossdaddi said she might marry you,” Joel said, avoiding the question.

“Jah, and...and Uncle Micah, too,” Asa supplied.

Neziah chuckled. “A woman can only marry one man, and a man only one woman. Ellen might marry me or your uncle Micah, or she might not marry either of us.” Neziah slid the chair back under the table and retrieved a crayon from the floor. It was almost too dark to see, and he wouldn’t have noticed it if he hadn’t stepped on it. “Good night, boys.”

“But will she?” Joel persisted.

He stopped in the doorway and turned back to his boys. “We’ll have to wait and see. If she marries your uncle Micah, she’ll be your aunt.”

Joel wrinkled his little nose. “Is that like a mutter?”

A lump rose in Neziah’s throat. Joel had been so small when his mother died, and Asa only an infant. Neither of them could remember what it was like to have a mother. Neziah felt a faint wave of guilt. Had he been selfish in waiting so long to remarry? His sons deserved a mother; everyone in Honeysuckle thought so. But would Ellen be right for them? For him?

“Ellen makes good pie,” Joel said.

Asa yawned. “I like pie.”

“Ellen does make good pie,” Neziah conceded. “Now, no more talking. Time for sleep.” Pretending not to hear the muted whispers behind him, Neziah made his way out of the boys’ room and down the stairs. He didn’t need a light. He knew the way by heart.

He continued on through the house, past the closed door to the parlor, where a thin crack of light told him that his father was still awake reading the Bible or working on correspondence as part of his duties as a church elder. He walked through the kitchen and outside, making his way to the old brick well that stood near the back porch. The windmill and a series of gears, pipes and a holding tank delivered water to the house and bathroom, but the coldest water came from the deep well. Neziah unlatched the hook and slid aside the wooden cover. With some effort, an overhead pulley, a rope and a wooden bucket rewarded him with an icy drink of water scooped out with an aluminum cup that was fastened to the iron frame.

Neziah leaned against the old brick and savored the water. This was another habit of his. Every night, if it wasn’t raining, sleeting or snowing, he’d come out to the well and draw up fresh water. He liked the sensation of the liquid, the rough texture of the bricks and the familiar curves of the bucket and cup. He’d always loved the well. It was a good place to think.

He was still standing there, one hand steadying the bucket, when he heard the rhythmic sound of a stone skipping across water. Instantly, he knew what it was. He finished his water, hung the cup back on the hook and walked across the yard, past the grapevines. At the edge of the small pond in the side yard, he spotted the outline of a figure. The figure tossed something just so and again Neziah heard the familiar splash, splash, splash of a rock skipping across water.

“Only three. Can’t you do better than that?” he called, walking toward his brother.

“It’s not about how many hops. I’m practicing my technique,” Micah explained.

“Ah.” By the light of the rising moon, Neziah picked up a stone from the water’s edge and slid it back and forth over his fingertips, judging its shape and weight. A good rock had to be flat and oval and just the right weight. “Your spin’s still not right.”

“My spin is fine.” Micah picked up another rock, crouched and threw it.

Four skips.

“You should try standing up to start...like this.” Neziah lifted his hand above his head, his wrist cocked, and then swung down and out in one smooth movement. The stone hit the water and skipped one, two, three, four, five times before disappearing beneath the surface.

“Okay, that was just practice. Best two out of three tries,” Micah challenged, picking up another rock.

Neziah smiled. The two of them had been competitive for as long as he could remember, mostly because of Micah, he liked to think. To Micah, everything was a game. But the truth be told, though, Neziah had a small competitive streak himself. Or maybe it just bugged him that his little brother was so good at everything. Nothing ever came hard to Micah.

“Best score of three,” Neziah agreed. He leaned over to find three perfect rocks. “How was fishing with Ellen?”

“Great.”

Neziah could just make out Micah’s face; he was grinning ear to ear. “And Ellen really is agreeable to marrying one of us?”

Neziah saw Micah shrug in the darkness as he picked up a stone, ran his fingers over it and rejected it. “It makes sense, and she’s a sensible woman. Or haven’t you noticed that?”

“You’re not usually so quick to seize on one of Vadder’s ideas.” Finding a near-perfect stone, Neziah passed it to his left hand for safekeeping.

“He’s right. It’s past time I married. I look at you with your two boys and...” Micah turned to Neziah, casually tossing a stone into the air and catching it. “You know what I think of them. Scamps or not, it’s time I had a few of my own. And for that I need a wife. Why not Ellen?”

“She’s older than you.”

Micah laughed. “That’s what she said. Wasn’t our mutter older than our vadder?”

“A year, I think, but there’s more than that between you and Ellen.”

“If it doesn’t bother me, it shouldn’t bother you, brother.” Micah stared at Neziah for a moment. The grin came again. “Not having second thoughts, are you? Wishing you hadn’t called things off when you did?”

“Of course not,” Neziah said a little too quickly. “We walked out together, that’s true, but there were differences that we couldn’t seem to...” He sighed and stood at the edge of the water. “Your turn.”