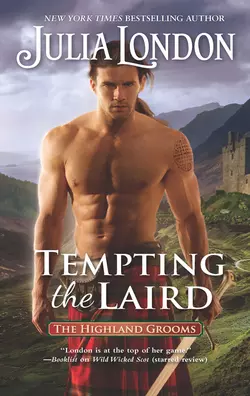

Tempting The Laird

Julia London

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Warm, witty and decidedly wicked—great entertainment.’ Stephanie Laurens on Hard-Hearted Highlander.Mystery and desire cloak the Scottish HighlandsUnruly. Unmarried. Unapologetic. Catriona Mackenzie’s reputation precedes her everywhere she goes. Her beloved late aunt Zelda taught Cat to live out loud and speak her mind, and that’s exactly what she does when Zelda’s legacy—a refuge for women in need—comes under fire. When her quest puts her in the path of the disturbingly mysterious Hamlin Graham, Duke of Montrose, Cat is soon caught up in the provocative rumours surrounding the dark duke.Never one to retreat, Cat boldly goes where no one else has dared for answers. Shrouded in secrets, a hostage of lies, Hamlin must endure the fear and suspicion of those who believe he is a murderer. The sudden disappearance of his wife and the truth he keeps silent are a risk to his chances at earning a coveted parliamentary seat. Bu he’s kept his affairs tightly held until a woman with sparkling eyes and brazen determination appears unexpectedly in his life. Deadly allegations might be his downfall, but his unleashed passion could be the duke’s ultimate undoingPraise for Julia London:‘Julia London writes vibrant, emotional stories and sexy, richly drawn characters.” New York Times bestselling author Madeline Hunter‘An absorbing read from a novelist at the top of her game.’ Kirkus Reviews, starred review, on Wild Wicked Scot‘Expert storytelling and believable characters make the romance [one that] readers will be sad to leave behind.’ Publishers Weekly, starred review, on Wild Wicked Scot