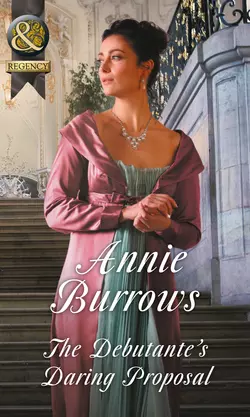

The Debutante′s Daring Proposal

Энни Берроуз

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘I want you to marry me.’Miss Georgiana Wickford has a plan to avoid the marriage mart—she’ll propose a marriage of convenience! She hasn’t spoken to the Earl of Ashenden since their childhood friendship was torn apart, but now Edmund is her only hope.Edmund refuses to take any bride, especially the unsuitable country miss who abandoned him years ago. But when he sees beautiful Georgie at the mercy of society’s rakes it arouses his protective instincts. And soon the Earl is tempted to claim the daring debutante for himself!