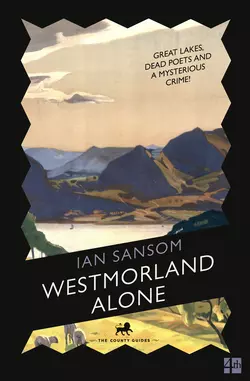

Westmorland Alone

Ian Sansom

‘Beautifully crafted by Sansom, Professor Morley promises to become a little gem of English crime writing; sample him now’ Daily MailWelcome to Westmorland. Perhaps the most scenic county in England! Home of the poets! Land of the great artists! District of the Great lakes! And the scene of a mysterious crime…Swanton Morley, the People’s Professor, once again sets off in his Lagonda to continue his history of England, The County Guides.Stranded in the market town of Appleby after a tragic rail crash, Morley, his daughter Miriam and his assistant Stephen Sefton find themselves drawn into a world of country fairs, gypsy lore and Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling. When a woman’s body is discovered at an archaeological dig, for Morley there’s only one possible question: could it be murder?Join Morley, Miriam and Sefton as they journey along the Great North road and the Settle-Carlisle Line into the dark heart of 1930s England.

The Market Place of Appleby

Copyright (#ulink_36c6625b-fdd2-5825-912c-ed5535331922)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

Copyright © Ian Sansom 2016

Cover image © Science & Society Picture Library / Getty Images

Ian Sansom asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008121747

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780008121754

Version: 2016-12-08

Dedication (#ulink_2f8bff62-041a-5cfe-8fe1-291df0dd1866)

For the other Morley

Epigraph (#ulink_e663e223-8d24-55e5-9614-54312760cf56)

Here we entered Westmoreland, a country eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England.

DANIEL DEFOE,

A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain

Contents

Cover (#uea996688-ef78-5e0d-847e-9123ae7e462e)

Title Page (#ub7a82667-53d6-5e0b-97bd-7e3c617c42dc)

Copyright (#ue0722f97-4c5b-5077-8d8c-2a9138154836)

Dedication (#uc96a649f-0287-539b-b824-b201a95aafb4)

Epigraph (#uf82d561a-e080-50d1-90c7-1ac200c3c405)

Chapter 1: The Infernal Streets of Soho (#u7a1c6b2e-c962-5157-b410-a43719cb4c60)

Chapter 2: Rise and Shine and Give God The Glory (#ud7fe1911-ad12-5103-a12d-2a268f3c8dba)

Chapter 3: 72 Miles, 1,728 Yards (#u6fd6881b-b158-524e-8642-44b72749fe90)

Chapter 4: Pandaemonium (#u009fe5ab-3d39-5796-9b6d-f917e9ad674f)

Chapter 5: Wild West Appleby (#u3023cb20-9aeb-5f94-86d0-7b4ee347d217)

Chapter 6: The Locomotive Accident Examination Guide (#u47665a40-c8ec-59b1-af42-d4730cc46740)

Chapter 7: Pencilariums and Pharmacopoeias (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8: English Archaeological Records (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: Death and Deceit and Despair (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: Merrie Englande (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: Stephen ‘Jawbone’ Sefton (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: The Stench of Cabbage and Onions (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: The Joy of Pickling (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: Gavver-Mush (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: A 22-Lever Midland Tumbler (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: The Hanging Room (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Ejecta, Rejecta, Dejecta (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: Some Photographic Techniques (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: A Totally Different Complexion (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: Dora’s Station Café (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: The End of the Story? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: Open to Closed (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Ian Sansom (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_60e8489e-248f-5586-8345-1ae31efd39ba)

THE INFERNAL STREETS OF SOHO (#ulink_60e8489e-248f-5586-8345-1ae31efd39ba)

LONDON WASN’T KILLING ME. The opposite.

We had returned from Devon in a low mood. Things had not gone at all according to plan. Miriam was no doubt distracting herself with some dubious engagement or other and Morley was probably working on some mad side project – a history of war, perhaps, or of the Machine Age, or of Russian literature, or indeed of Russia, or of fish, of friendship, of God, of the gold standard, goodness only knows what. (See, for example, Morley’s War – And its Enemies (1938), Morley’s Forces of Nature in the Service of Man (1932), Morley’s Fish, Flesh and Fowl: A History of Edible Animals (1935), Morley’s Mighty Bear: A Children’s History of Russia (1930), Morley’s Studies in Christian Love (1934), Morley’s God: His Story (1936), and one of my favourites, published rather unfortunately in 1929, Morley on Money: How to Make It, How to Spend It, How to Save It.) I was just glad that I’d been granted a few days’ leave. I had been making the most of them.

I had been drinking late in the Fitzroy Tavern, and had then found myself at an after-hours club just off Marshall Street which was frequented by some of my old International Brigade chums. The club was run by a big Kerryman named Delaney who ran a number of places around Soho. Delaney self-consciously styled himself as a ‘character’ – all thick Irish charm, topped off with faux-aristo English manners. He wore a white tie and tails, carried a silver-topped cane with a snuff-pot handle and came across as everyone’s friend, the debonair host, generous, witty and easy-going. He was not at all to be trusted. I had been introduced to him by a couple of lads from Spain, Mickey Gleason, a tough little Cockney with a beaten-up face, and a classically dour stick-thin Scotsman named MacDonald. Gleason liked to boast that he had saved my life in Spain, when in fact all he’d done was to cry a well-timed ‘Get down!’ when we had come under unexpected fire one evening near Figueras. And MacDonald had loaned me money – dourly – on my return. So I was in debt to them both, in different ways. Delaney had also been in Spain, apparently, though I hadn’t met him there. It was said that he’d been working as some kind of fixer. I rather suspected that he had enjoyed as much business with Franco’s forces as with the Republicans.

Delaney’s places were famous for their wide range of entertainments and refreshments, and for the clientele. It used to be said that to meet everyone in England who really mattered one had only to stand for long enough at the foot of the stairs of the Athenaeum on Pall Mall: the same might just as truly be said of Delaney’s basement bars and bottle parties. Poets, artists, lawyers, politicians, doctors, bishops and blackmailers, safebreakers and swindlers: in the end, everyone ended up at Delaney’s.

I’d started out drinking champagne with one of Delaney’s very friendly hostesses, a petite redhead with warm hands, cold blue eyes, sheer stockings and silk knickers, who seemed very keen for us to get to know one another better – but then they always do. She told me her name was Athena, which I rather doubted. Sitting on my lap, and several drinks in, she persuaded me into a card game where I soon found myself out of my depth and drinking a very particular kind of gin fizz, with a very particular kind of kick – a speciality of the house. My head was swimming, the room was thick with the scent of perfumes, smoke and powders, I had spent every penny of the money that Morley had paid me for our Devon adventure, I was in for money I didn’t have – and Athena, needless to say, had disappeared. My old Brigade chums Gleason and MacDonald were watching me closely. Even through the haze I realised that if I didn’t act soon I was going to be in serious trouble: Delaney was renowned for calling in his debts with terrible persuasion.

I excused myself and wandered through to the tiny courtyard out back. There were men and women in dark corners doing what men and women do in dark corners, while several of the hostesses stood around listlessly smoking and chatting, including Athena, who glanced coolly in my direction and ignored me. She was off-duty. Out here, there was no need to pretend.

I picked my way through the squalor, past beer crates and barrels, and went to use the old broken-down lavatory in the corner of the yard. When I tried to flush the damned thing I found it wasn’t working. I stood pointlessly rattling the chain for a moment and then climbed drunkenly up onto the seat and quickly discovered the problem. There was no water in the cistern. And there was no water in the cistern for a very good reason: the lav served as Delaney’s quartermaster’s store. I had found myself a little treasure-trove. A honeypot. I glanced up and thanked the heavens above. Through the rotting makeshift roof of the lav I could see the starry blue sky. It was a beautiful warm autumn evening. Suddenly, everything seemed OK. And anything seemed possible. I seemed to have shaken off my torpor. Without hesitation – without thinking at all – I decided that this unlikely Aladdin’s cave presented me with the perfect opportunity to make up for some of my losses inside. I dipped my hand in and helped myself to some supplies. I took only what I needed.

I felt revived and reinvigorated. I considered returning to the game. I had a feeling my luck had changed. Athena and the other women had gone back inside and there were only one or two couples remaining in the yard. It would have taken a dousing with a bucket of cold water to get their attention. In the opposite corner to the lav was a convenient big black door out into an alleyway. I realised I could probably disappear and no one would notice.

I unbolted the door, slipped into the alleyway, and started walking.

The infernal streets of Soho were unusually quiet and I found myself once again wandering that blessed one-mile square, from Oxford Street to the north and Shaftesbury Avenue to the south, from Regent Street to the west and Charing Cross Road to the east, that strange other-world – or underworld – where so many of us come to escape, and where many of us find ourselves for ever trapped.

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to return to my temporary lodgings, a place just off Wardour Street that generously, if inaccurately, described itself as a hotel. I doubted that the management would be willing to accept an IOU for payment and there was no way I was parting with my recently acquired pocketful of treasure and so, eventually, exhausted from my wandering and still trying to flush the various excitements of the evening out my system, I found myself lying down to nap on a bench outside Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court. This was ironic.

In his Dictionary of Usage and Abusage (1932) Morley writes at great length, and with utter despair, about the common misuse of the term ‘irony’ by both the ill-educated and the over-educated. ‘An ironic statement,’ he writes, ‘is like a good lawyer or a politician. It says one thing but means another. An irony is not merely something odd or unusual. The word “ironic” should never be used to describe the merely unfortunate.’ My laying my head down outside Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court was not therefore, perhaps, strictly speaking, an irony. It was, however, at the very least, extremely unfortunate.

Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court was the first court in which I ever appeared. It was shortly after I had returned from Spain. I had become involved with a woman who was involved with a man who had treated her badly. Fortunately at the time I had money and resources and was therefore able to employ a good lawyer who managed to get me off with only a fine on a charge of common assault. This encounter with the law was an experience I was determined not to repeat. Morley would probably have called this hubris.

It was 3 a.m., I was cold and tired, and as far as I recall my reasoning went something like this: if the safest place to sleep rough is a police cell then the next safest is probably on the steps of a court. On both counts, alas, I turned out to be wrong.

I found myself prodded awake by three varsity types who had clearly enjoyed a long night at the opera. They were all in evening dress. There was a fat blond buffoonish-looking one who wore a yellow gardenia in his buttonhole, a greasy-looking one, with brilliantined hair, and the other – the other might almost have been me, before everything that happened had happened.

The first thing I knew was the greasy one tapping his cigar ash into my eyes.

‘Come on, man! Up! Up!’ He was leaning over me, breathing his fumes into my face. ‘Show some respect to your betters, you filthy swine!’

‘Hey! Tramp!’ called the fat blond, with an Old Etonian drawl. He ran his fingers through his unruly mop of hair. ‘What’s the matter with you! Have you no home to go to? Eh? Come on! Come on! Up! Up! Up! Queensberry Rules, old chap! I’ll take you on!’

The greasy one grabbed me by my lapels. I feared that at any moment he might reach into my pockets.

I acted on instinct.

I raised my knee, catching him on the side of the head. I had been involved in enough brawls in Spain to know that the important thing was just to get away. That’s all I was intending to do.

As he was falling back I hooked my foot around his ankle and then swung a punch at his head with the side of my fist. He twisted as he went down and it was his face that hit the pavement first. There was a sickening thud. The fat blond then came roaring at me, but I managed to push him off easily, and he too went down. The third man ran off.

The fat blond would be fine: he was just winded and shocked. But the greasy-looking one had gone down hard and had gone very quiet: there was a pool of blood haloed around his head. He did not look at all well.

To repeat, to be clear, and in case of confusion: I had been attacked; I had acted in self-defence; and what had happened was clearly an accident.

In his controversial pamphlet ‘In Defence of Self-Defence’ (1939), a much misunderstood little treatise, Morley sets out the criteria by which a person or nation might justly claim the right to defend themselves. Morley’s criteria are clear, detailed and as follows: self-defence may be permissible only if and when ‘1) a culpable 2) aggressor 3) knowingly initiates 4) an unprovoked attack 5) on an innocent victim 6) who is unable to avoid or escape harm 7) without causing necessary 8) or proportionate harm 9) with the sole intention 10) of defending himself’. Morley then further clarifies the permissible conditions and circumstances with a sentence that subsequently caused him much pain and harm: ‘Even when such conditions are met it is still debatable whether self-defence by a nation or person can ever be considered a moral good.’ His timing was unfortunate. It was a misjudgement: everyone, it seems, even Morley, makes mistakes.

All I would have had to have done at that moment was to explain what had happened to the police. It was perfectly simple. I was an innocent man, admittedly an innocent man with a criminal record, who had recently returned from Spain, admittedly fighting with the communists, and who had found employment with one of the country’s most revered and famous authors, admittedly on rather false pretences, and I had been enjoying a quiet evening in Soho, admittedly in an after-hours drinking establishment, from which I had fled, admittedly owing almost one hundred pounds in gambling debts, and with a pocketful of illegal and expensive powders, which were not, strictly speaking, my own … whereupon I had become the victim of an unprovoked attack by culpable aggressors and had acted with the sole intention of defending myself.

I did not in fact attempt to explain this to the police.

I owed it to Morley not to get him involved.

And, of course, I owed it to myself.

I did what anyone else would have done.

I ran.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_7d03329a-0edf-571e-aec8-4aa1b2404837)

RISE AND SHINE AND GIVE GOD THE GLORY (#ulink_7d03329a-0edf-571e-aec8-4aa1b2404837)

AS DAWN BROKE I found myself wandering up Great Portland Street, onto the Euston Road and along towards St Pancras.

The arrangement had been to meet Miriam and Morley outside St Pancras at 7 a.m. in order to set off on our next adventure. The first of the County Guides – to Norfolk – had been published to a few lukewarm reviews by the sort of reviewers who regarded Morley’s work as beneath contempt. ‘Yet another pointless and whimsical outing from England’s self-styled “People’s Professor,”’ wrote some pompous – anonymous – twit in the Times Literary Supplement (or the ‘Times Literary Discontent’, as Morley called it). ‘A work of enthusiasm rather than of serious scholarship,’ complained some frightful bluestocking in The Times. ‘Essentially frivolous,’ concluded the Manchester Guardian. But Morley was not discouraged. He was never discouraged. He was not, I believed at the time, discourageable. The Grand Project, Le Grand Projet – The County Guides, a complete guide to the English counties, a people’s history, forty or more volumes in all, a volume to be completed every three to four weeks, his mad modern Domesday Book – was not to be derailed by anyone, rich or poor, educated, uneducated, varsity, non-varsity, dead or alive.

During my time with Morley I did my best to share his enthusiasm, and his enthusiasms, but I was really always trying to escape, to get away and to start again. The work was not uninteresting, of course, and our adventures became renowned but I was never really anything more than a glorified secretary. Morley referred to me variously over the years as his amanuensis, his assistant, his apprentice, his accomplice, his aide and, alas, as his ’bo. None of these descriptions were really adequate. For all my work and for all that the photographs featured in the books were mine I was only ever an acknowledgement buried among the many others, the page after endless page of Morley’s super-scrupulous solicitudes. ‘With thanks to the ever-accommodating British Library, to the staff of the London Library, to the University of London Library …’ and to all the other libraries, ad nauseam. ‘To H.G. Wells, and to Gilbert Chesterton, to James Hilton, to Nancy Cunard, to Dorothy Sayers, to Rosamond Lehmann, to Naomi Mitchison, and to dear Wystan Auden …’ and to all of my other famous friends. ‘To the dockers of east London, to the factory workers of Manchester …’ and to the fried fish sellers, to the piemen and piewomen, and the dolls’ eyes manufacturers of this great island nation. ‘To the people of Rutland, of East Riding, of west Dorset …’ and of everywhere else. ‘And to Stephen Sefton, and the Society for the Protection of Accidents, without whom …’ Etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.

Every time we finished a book I vowed never to return. Sometimes I dreamed of going back to Spain, or of going back to teaching, of worming my way into the BBC, of pursuing photography seriously as a profession, of starting again somewhere else. Anywhere else. Anywhere but England. And every time I failed. I was always drawn back, again and again. I never quite understood why.

With St Pancras up ahead and the prospect of another tiresome cross-country jaunt before me I was thinking that this time I might simply trail off into deepest darkest north London, to lick my wounds, clear my head and devise a plan.

And then I saw Miriam.

In one of his very strangest books, Rise and Shine and Give God the Glory (1930), part of his ill-fated Early Rising Campaign – hijacked by all sorts of odd bods and unsavoury characters – Morley advises the early riser not only to practise pranic breathing and vigorous exercise, but also to utter ‘an ecumenical greeting to the dawn’, a greeting which, he claimed, was ‘suitable for use by Christians, Jews, Mohammedans, Hindoos, and peoples of all religions and none’. Borrowing words and phrases from Shakespeare, Donne, Thomas Nashe, Robert Herrick and doubtless all sorts of other bits and pieces culled from his beloved Quiller-Couch and elsewhere, the greeting begins with a gobbet from William Davenant: ‘Awake! Awake! The morn will never rise / Till she can dress her beauty at your eyes.’ I was never a great fan of this ‘ecumenical aubade’ of Morley’s but this morning it seemed to fit the occasion.

Miriam sat outside St Pancras enthroned in the Lagonda like the sun on the horizon: upright, commanding and incandescent. Her lips were red. She had dyed her hair a silvery gold. She wore a brilliant green dress trimmed with white satin. And she had about her, as usual, that air of making everyone and everything else seem somehow slow and soft and dull, while she alone appeared vivid and magnificent – and hard, and fast, and dangerous. Une maîtresse femme. For those who never met her, it is important to explain. Miriam was not merely glamorous, though she was of course glamorous. Miriam was beyond glamour. Hers was an entirely self-invented, self-made glamour – a self-fulfilling and self-excelling glamour. And on that morning she looked as though she had painted herself into existence, tiny deliberate brushstroke by tiny deliberate brushstroke, a perfectly lacquered Ingres wreathed in glory, the Lagonda wrapped around her like Cleopatra’s barge, or Boadicea’s chariot.

‘Good morning, Miriam,’ I said.

‘Ah, Sefton.’ She took a long draw on her cigarette in its ivory holder – one of her more tiresome affectations. She brought out the ivory holder, as far as I could tell, only on high days, holy days and for the purposes of posing. She looked at me with her darkened eyes. ‘Early, eh? Up with the lark?’

‘Indeed.’

‘And the lark certainly seems to have left its mark upon you.’ She indicated with a dismissive nod an unsightly stain on my blue serge suit – damage from my night outside Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court.

I did my best to rub it away.

‘I’m rather reminded of Lytton Strachey’s famous remark on that stain on Vanessa Woolf’s dress—’ (This ‘famous’ remark is not something that one would wish to repeat in polite company: which is doubtless why Miriam enjoyed so often doing so.)

‘Yes, Miriam. Anyway?’

‘Yes. Well. Father’s away for the papers, Sefton, so really it’s very fortuitous.’

‘Is it?’

‘Yes. It means that you and I can have a little chat.’ This sounded ominous. ‘Why don’t you climb up here beside me.’ She patted the passenger seat of the Lagonda.

‘I’m fine here, thank you,’ I said. It was important to resist Miriam.

‘Well, if you insist,’ she said. ‘I’m afraid I have bad news, Sefton.’

‘Oh dear.’

‘Yes. I’m afraid this is going to be the last of these little jaunts that I’ll be joining you on.’

‘Oh,’ I said, and said no more.

‘Well, aren’t you going to ask me why?’

I paused for long enough to exert control. ‘Why?’

‘Because,’ she said triumphantly, ‘I, Sefton, am … engaged!’

‘Oh.’

‘I think you’ll find it’s traditional to offer congratulations.’

‘Congratulations,’ I said. ‘Who’s the lucky fellow?’

‘No one you know!’ She gave a toss of her head and looked away. ‘He gave me this diamond bracelet.’ She waved her elegant wrist at me. ‘Isn’t it marvellous!’

It was indeed a marvellous diamond bracelet, as marvellous diamond bracelets go. Men had a terrible habit of showering Miriam with marvellous gifts – diamonds, sapphires, furs and pearls, the kind of gifts they wouldn’t dare to give their wives, for fear of raising suspicion.

‘Isn’t it more usual to exchange rings?’ I asked.

‘Oh, the ring is coming!’ said Miriam.

When the poor chap had finalised his divorce, I thought, but didn’t dare say.

The sound of the city was growing all around us: horse and carts, cars, charabancs, paperboys, and above it all, the sound of a woman nearby selling flowers. ‘Fresh flowers! Fresh flowers! Buy my fresh flowers! Flowers for the ladies!’

Miriam smiled her smile at me and glanced nonchalantly away.

‘Anyway, Sefton,’ she continued, ‘this means that I won’t be joining you and Father on any more trips. And so I just wanted some sort of guarantee that you’d be around for as long as this damned project takes. Father has become terribly fond of you, Sefton, as I’m sure you know.’

There was in fact very little sign of Morley’s having become very fond of me. Morley didn’t really do ‘fond’. I don’t think he’d have known the meaning of ‘fond’, outside a dictionary definition.

‘Sefton?’

I didn’t answer.

‘As you know, Father needs a certain amount of … looking after. After Mother died …’

Mrs Morley had died before I had started work with Morley; he and Miriam rarely spoke of her.

‘He needs a certain amount of care and attention. I hope you can—’

We were disturbed by the sounds of what seemed to be an argument – of an English voice uttering some low, strange, unfamiliar words, the sound of a woman shouting in response, either in distress or delight, of voices calling out, and of general confusion and hubbub.

‘Thank you!’ called the voice. ‘Gestena!Danke schön. Grazie. Go raibh maith agat!Xie xie. Muchas gracias!’ It was a Babel of thanks-giving. It could only be one person: Morley.

He approached us, be-tweeded, bow-tied and brogued as ever, and carrying what appeared to be every single British daily newspaper, and very possibly every European paper as well. He appeared indeed like an emblem or a symbol of himself: Morley was, basically, a machine for turning piles of paper into yet more piles of paper. He was also carrying, rather incongruously, an enormous bunch of gaudy and distinctly unfresh-looking flowers.

‘Ah, Sefton!’ he said, thrusting the flowers at me, and the newspapers at Miriam.

‘Flowers, Mr Morley?’

‘Oh no, sorry, they’re for Miriam. The papers are for us, Sefton, reading material on the way.’

I duly handed Miriam the flowers.

‘For me, really?’ she said. ‘You shouldn’t have, Sefton!’ She handed me the papers in return, shaking her diamond bracelet at me unnecessarily as she did so. ‘They’re lovely, Father, thank you.’

‘Well, I could hardly not buy any flowers from the woman, since she allowed me to practise my – admittedly rather rusty – Romani on her.’

I had no idea that Morley spoke Romani. But I wasn’t surprised.

‘Devilish sort of language. Do you know it at all, Sefton?’

‘I can’t say I do, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Dozens of varieties and dialects. Indo-Aryan, of course, but quite unique in many of its features – tense patterns and what have you. And only two genders. Easy to slip up. I fear I may have said something to upset the poor woman. I remember I was in Albania once and I thought I was complimenting this very proud Romani gentleman about his pigs, when in fact I said something about defecating on him and his family! Terribly embarrassing.’

‘Father,’ said Miriam. ‘That’s enough. Get in the car.’ This was one of Miriam’s more successful methods of dealing with Morley: shutting him up and ordering him around.

We were beginning to attract a small crowd of onlookers. The Lagonda was by no means inconspicuous, and Morley was the closest thing to a celebrity that one could possibly be without appearing on the silver screen. I scanned the crowd, beginning to feel distinctly uncomfortable. I half expected to see Delaney, Mickey Gleason, MacDonald, the police, or indeed my old varsity chums from the steps of Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court. Morley of course was unaware and oblivious, as always.

‘Anyway, Sefton, now you’re here you can tell me, what do you think of the Great North Road?’ He was shifting quickly and apparently senselessly from subject to subject – as was his habit.

‘The Great North Road, Mr Morley?’

‘Yes, indeed, the great English road, is it not? The spine of England! From which and to which everything is connected. Any thoughts at all at all at all?’

I had no thoughts about the Great North Road, and Morley wasn’t interested in my thoughts about the Great North Road. He was interested in using me as a sounding board.

‘Do you know Harper’s book on the road?’

‘I can’t say I do, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Pity. Marvellous book. Rather romantic and sentimental perhaps – and outdated, actually, thinking about it.’ His moustache twitched – the telltale sign of an idea forming. ‘Miriam, don’t you think we could perhaps produce our own little homage to the Great North Road on this trip? Four Hundred Miles of England?’

‘I think our hands are rather full at the moment, Father,’ said Miriam. She got out of the car, and ushered Morley into the back seat of the Lagonda, and began fitting his desk around him.

‘Well, a slim volume perhaps? Three Hundred and Forty Miles of England? We could stop our tour at Berwick-upon-Tweed?’

‘Yes, Father.’ This was another of Miriam’s techniques for dealing with Morley: humouring him. It seemed to work.

‘A little preface or prologue, perhaps? A record of significant stops and sights along the way. A kind of investigation of the meaning of the road. You know, I rather have the notion that it might be possible to invent an entirely new kind of writing about places – a kind of chronicling not only of their physical but also their psychical history, as it were.’

‘Psychical geography?’ I said.

‘Exactly!’ said Morley.

‘I don’t think it would catch on, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘No?’

‘No, Father.’

‘Well, just a straightforward guide then, perhaps? Stilton. Stamford. Boroughbridge. Are you a fan of Stilton, Sefton?’

‘Stilton, Mr Morley?’

‘The cheese, man. Are you a Stiltonite? Lovely with a slice of apple, Stilton.’

‘Where do you stand on Stilton, Sefton?’ asked Miriam.

‘The English Parmesan, Stilton,’ said Morley. ‘Or perhaps Parmesan is the Italian Stilton …’

‘Sorry?’

I was no longer listening. I had spotted a policeman who had noticed the crowd and who was now walking briskly towards us. He seemed to be looking directly at me. I was still standing by the Lagonda. I checked quickly behind me; if I was quick I’d be able to make it across the Euston Road and disappear.

All was not lost.

And then it was.

I had spotted him too late.

The policeman blew his whistle: many people had now stopped and were staring. I had nowhere to go.

‘Hey! You!’ he called, reaching the Lagonda. ‘You! What on earth are you doing?’

‘Excellent whistle!’ said Morley, from the back of the Lagonda.

‘What?’

‘Your whistle, Officer. I wonder, is it made by Messrs J. Egdon of Birmingham, by any chance?’

‘I have no idea,’ said the policeman.

‘They’re renowned for their whistles,’ said Morley.

‘Really? And you’re a whistle expert, are you?’

‘I wouldn’t say that …’ began Morley. He was a whistle expert, obviously.

‘Who are you and what do you think you’re doing?’ demanded the policeman.

‘Well, to answer your second question first, if I may,’ said Miriam. ‘I think you’ll find that what we’re currently doing is speaking with you.’

‘You are blocking the entrance to the station, madam,’ said the policeman, unamused.

It was true: Miriam had parked, as usual, without care or regard for other road-users, and our small gathering of onlookers had begun to cause a problem.

‘Oh, that!’ said Miriam. ‘Are we? Really? I hadn’t noticed. I’m terribly sorry.’

‘I’m not looking for an apology, madam. You realise I could book you under the Road Traffic Act of 1930 for obstructing the king’s highway?’

‘Oh, I’m sure you could book us, Officer,’ said Miriam, lowering her voice and fixing the poor policeman with her most glimmering smile. ‘But the question is, would you?’

This threw the policeman rather, who obviously was not accustomed to being flirted with by a woman of Miriam’s considerable expertise and world-class charms. He changed his line of questioning and turned to me.

‘Is this man with you, madam?’ He had clearly noted my rather rumpled appearance.

‘Him?’ said Miriam.

I could see that she was considering causing mischief. I prepared to sprint.

‘Of course!’ she said. ‘He’s my fiancé, aren’t you, darling!’ She leaned across the car and offered her cheek for me to kiss. I had no choice but to oblige. ‘He’s just bought me some flowers, Officer. Isn’t he adorable?’

‘Ha!’ came a laugh from the back seat.

‘And this gentleman?’ asked the policeman, nodding towards Morley.

‘This is my father, Officer.’

‘And where are you all headed this morning, might I ask?’ The policeman addressed his question to me.

‘We are headed to …’ I had no idea. Miriam and Morley usually didn’t tell me where our next destination was until we were en route. I rather suspected that this was often because they didn’t know themselves.

‘We are headed, sir, to the very heart of the country!’ said Morley. ‘The hub! The centre! The cultural capital!’

‘And where is that exactly?’ asked the policeman, having extracted a notebook from his pocket and taken down the registration of the car.

‘Westmorlandia!’ said Morley. ‘Westmoria! The western Moorish county.’ He began whistling the Toreador Song from Carmen. (He had a recording of the Spanish mezzo-soprano Conchita Supervia singing the role of Carmen, which he claimed was one of the great cultural achievements of all time. He also claimed this, it should be said, for Caruso singing ‘Bella figlia dell’ amore’ in Rigoletto, Rosa Ponselle in Tosca, and John McCormack singing just about anything.)

‘No. Still no wiser, sir. If you wouldn’t mind spelling that for me?’

‘Westmorlandia! One of the truly great English counties!’ continued Morley. ‘Home of the poets! Land of the great artists! We shall be visiting the mighty Kendal. Penrith – deep red Penrith! Ambleside. And we shall follow the River Eden as she rises at Mallerstang and makes her majestic way to the Solway Firth—’

‘We’re visiting the Lake District, basically,’ said Miriam.

‘Ah,’ said the policeman, writing in his notebook.

‘Westmorland!’ cried Morley. ‘Do get it right, Miriam, please. Westmorland! Which – combined with Cumberland – might together accurately be described as “the Lake District”, though of course the designation is rather misleading because—’

‘And what is your business exactly in Westmorland, sir?’

‘Our business? Our business, sir, is to do no less than justice and no more than to offer honest praise!’

‘Exactly what is your business in Westmorland, sir?’ The policeman was getting tired: I’d seen it before. Morley’s eccentricities could be extremely wearing.

‘We are writing a guidebook,’ said Miriam. ‘To the county and its—’

‘Roofs!’ cried Morley. ‘The roofs of Westmorland are some of the finest in the land, Officer. Did you know?’ Morley had a great enthusiasm for roofs. He began explaining the quality of the roofs of Westmorland to the policeman, who wisely decided at that point that it was time to give up.

‘On you go then, please,’ he said. ‘If you don’t mind. Move along now, people,’ he told the crowd. ‘There’s nothing to see here.’

‘Thank you, Officer,’ said Miriam. ‘Come on, darling,’ she said to me.

I remained silent and did not breathe a sigh of relief until the policeman had plodded his way far enough from the car and the crowd had begun to disperse, and then I breathed a very big sigh of relief indeed.

‘Let’s go,’ I said to Miriam, moving quickly around to the passenger side of the Lagonda.

‘All aboard the Skylark!’ cried Morley.

‘You’re keen all of a sudden,’ said Miriam to me.

‘Charming man,’ said Morley. ‘The British bobby – curious, steadfast, and yet always polite.’

‘Indeed,’ said Miriam. ‘Now, gentlemen, shall we just check our route.’ She produced a map and several of the boards onto which Morley had mounted his county maps. ‘Our route. We begin in London, obviously.’

‘Starting at the GPO?’ said Morley. ‘The traditional starting point of the Great North Road?’

‘Starting here, Father. And then Herts, and Beds, and Cambridgeshire, Rutland, Lincs, Notts, West Riding—’

‘And then a left turn at Scotch Corner?’ said Morley.

‘And then a left turn at Scotch Corner,’ agreed Miriam.

I was half listening and had already begun opening the door when I saw him: MacDonald. He was perhaps a hundred yards away, across the other side of the Euston Road. I recalled him mentioning before that he lived somewhere up around King’s Cross. When he saw me, as inevitably he would, he would doubtless want to raise the small matter with me of my having abandoned our card game, and possibly the no less small matter of my having departed with several packets of Delaney’s precious ‘snuff’.

I stood rooted to the spot.

‘Scotch Corner,’ continued Morley, ‘being of course the junction of the traditional Brigantian trade routes in pre-Roman Britain, and the site where the Romans fought the Brigantes. The Brigantes being?’

‘A Northern Celtic tribe, Father,’ said Miriam wearily.

‘Correct! And they fought the Romans at the Battle of?’

‘Scotch Corner?’ I said.

MacDonald had seen me. He stared for a moment in surprise and then smiled a dark smile and began making his way hurriedly through the traffic. I had less than two minutes. If I stayed with Miriam and Morley and the car we wouldn’t be going anywhere fast.

I had a choice. I could either make a run for it or …

‘The Battle of Scotch Corner is correct!’ said Morley. ‘You know, perhaps you’re finally getting to grips with this stuff, Sefton. We’ll also have a look at the Stanwick fortifications, which are about five miles north-west of Scotch Corner, and which I think I’m right in saying form the most extensive Celtic site in Britain—’

‘I think I might get the train, actually, Mr Morley, and meet you there.’

‘The train?’ said Miriam.

‘Ah!’ said Morley. ‘You’re thinking of the Settle–Carlisle line, Sefton, are you not? Possibly the greatest railway line in the country. A sort of railway companion to our Great North Road journey?’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘That’s exactly what I’m thinking, Mr Morley.’ MacDonald was twenty yards away and closing fast. ‘I would just need some money, to—’

‘Of course,’ said Morley. ‘Good thinking, Sefton. I think it would certainly add immeasurably to the book if you were to travel by train, we were to travel by car, and then we could compare notes when we arrive in Westmorland and—’

‘I really need to go now though.’

Morley consulted his two watches – the luminous and the non-luminous dials.

‘Yes, the seven fifteen, would that be it?’ He had – naturally – memorised most of Bradshaw’s. ‘If you hurry you might just catch it.’

‘I’m going to catch it.’

‘Good, now let’s give the man the means, Miriam, shall we?’

Miriam looked at me suspiciously but nonetheless began rooting around in her handbag.

‘And the camera, Miriam, give him the camera. Come on, hurry!’

‘The new Leica, Father? But I thought I might—’

‘Now, now, Sefton is our photographer. We did buy the camera for him. It’s the new Leica, Sefton. I was particularly impressed by the set-up we saw in Devon, and I thought perhaps you might enjoy using it. Give you something to play with on the train.’

‘I’m sure Sefton will find something to play with on the train,’ said Miriam, handing over the camera and a handful of cash. ‘That should be enough to cover a third-class fare, Sefton. You’ll be travelling third class, of course?’ Miriam smiled at me.

‘For colour?’ said Morley. ‘Yes, good thinking, Miriam. Travelling with the people. Ours is a people’s history, after all.’

‘Of course,’ I said.

MacDonald was just five yards away. I could see the veins throbbing in his neck and his eyes bulging.

‘I think we’ll beat you to it,’ said Miriam, but I didn’t answer: I had already begun to run.

‘Sefton!’ shouted Miriam after me. ‘Where will we see you?’

‘Appleby!’ cried Morley. ‘The county town of Westmorland! We’ll meet you at Appleby, Sefton!’

I ran into the station, shouting to the porters for the seven fifteen: they pointed me to platform 3. I ran past the ticket inspector and made it to the last carriage of the train, where a young mother was struggling to get on with a young girl and a baby. The guard was calling the departure as I managed to lift up the girl and slam the door behind us – and the train shuddered forward.

I stood for a long time at the window looking out for MacDonald, but there was no sign of him. I must have lost him in the crowd.

Satisfied, I made my way to a compartment, squeezing past fellow passengers and their luggage. There was the woman with the baby and the child.

‘Mummy, Mummy,’ said the little girl. ‘It’s the nice man, Mummy.’

The young woman smiled at me warmly.

‘Do you mind if I join you?’ I said.

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘Thank you so much for helping.’

‘The baby will cry,’ said the little girl. ‘But all babies cry. What’s that?’ she asked, pointing at the Leica.

‘It’s a camera,’ I said.

‘What’s a camera?’

‘It’s something that you can take pictures with.’

‘Like a drawing?’

‘Yes, I suppose.’

‘Is there a pencil inside it?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘There’s not a pencil.’

‘Is there a pen?’

‘No, there’s not a pen either.’

‘Is there paint?’

‘Look,’ I said. ‘Do you want to see?’

The girl looked at her mother, her mother nodded, and the little girl came and sat close to me; as we left London I showed her how to open the camera, how to check the shutter and the focus and how to frame a photograph. I took her photograph and she took mine.

‘Are you coming with us?’ asked the girl. ‘Mummy, can the man come with us?’

‘The man is on his own journey,’ said the mother. ‘He’ll be going somewhere himself.’

‘We’re going to Carlisle,’ said the little girl. ‘Where are you going?’

I looked at her. I felt suddenly exhausted. ‘I don’t know, actually,’ I said. ‘I don’t know where I’m going.’

‘You’re funny,’ said the girl. ‘You’re a funny man!’

‘He’s just tired,’ said the mother. ‘Let him rest now.’

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_eadfce21-7178-5758-a483-3cd9808c8ab4)

72 MILES, 1,728 YARDS (#ulink_eadfce21-7178-5758-a483-3cd9808c8ab4)

IT WOULD NOT BE an exaggeration to say that Morley was obsessed with the Settle–Carlisle line. He was obsessed with a lot of things, of course, but the Settle–Carlisle remained for him one of the great foundation stones – ‘one of the canonical lines’, he famously called it – of England. I have no doubt that if he could have seen the destruction later wrought upon the railways he would not have despaired: he simply would not have let it happen. There would have been campaigns, organisations, books, leaflets, marches on London, a popular uprising: Mr Beeching would have taken one hell of a beating.

After our trip to Westmorland, Morley revised and updated his famous book, 72 Miles, 1,728 Yards (1935), in which he describes the route of the Settle–Carlisle line, mile by mile, yard by yard, tunnel by tunnel, viaduct by viaduct, every gradient, every ascent, every twist and every turn. I doubted that the new edition would sell a single copy. It became a bestseller. His most popular lecture series – by far – during our time together was on the Settle–Carlisle line, more popular than the ‘World of Wonders’ series and the ‘Home Husbandry’ series combined, more popular even than the infamous ‘Communism, Fascism: What Exactly is the Difference?’ lecture, which always drew a crowd (and which, indeed, on a number of occasions, caused a riot). In the Settle–Carlisle lectures he lovingly described the planning and construction of the line, its maintenance, and its day-to-day operations, beginning and ending with a sing-song recitation of the names of all the stations: Settle, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Ribblehead, Dent, Garsdale, Kirkby Stephen, Crosby Garrett, Ormside, Appleby, Long Marton, Newbiggin, Culgaith, Langwathby, Little Salkeld, Lazonby and Kirkoswald, Armathwaite, Cotehill, Cumwhinton, Scotby, Carlisle. Anywhere north of Watford the recitation of the station names alone would often earn him a standing ovation. (Admittedly, the lectures tended to be less popular in the Home Counties, though they played surprisingly well in London.)

Indeed, in recognition of his work promoting the railway industry in general and the Settle–Carlisle line in particular the big four railway companies – the old LNER, and the GWR, the LMS and SR – awarded Morley in 1939 a fat little golden locket, inscribed with his name, on a chain. He needed only present the locket to a ticket inspector on board a train to be granted free first-class travel the length and breadth of the country. Morley cared almost nothing for awards and baubles: one bathroom at St George’s was rather eccentrically papered with moulding black and white certificates and citations that might more usually have been proudly framed and displayed, and a crusty old armoire in a guest bedroom served as storage space for his various medals, statuettes and gifts ‘in recognition of’, many of them featuring depictions of pens and quills carved in marble, onyx, or, in one case – after our trip to Durham – made out of coal. Morley referred habitually to such awards and honours as ‘chaff’ and, occasionally, as his ‘pointless paper empire’.

But the Big Four locket travelled with him everywhere until the day he died.

According to Morley in 72 Miles the Ribblehead viaduct was one of the modern wonders of the world, and the route of the Settle–Carlisle line ‘a journey into the heart of England and Englishness’. (He also made this claim, it should perhaps be conceded, about the west Norfolk coastal route, the GWR journey down to Devon, the Esk Valley line, and the all-electric Southern Belle route from Victoria to Brighton.) Describing the Settle–Carlisle line he rose to sweeping rhetorical heights:

There is perhaps not even in Switzerland, nor in India, nor indeed in our own green and pleasant land, a more magnificent journey than that through the great valley of the Ribble, and on round the broad shoulder of the mighty Whernside at Blea Moor, on through the valleys of the Dee and Garsdale, up and over the watershed to the summit at Aisgill, and then through the justly named Eden Valley towards Carlisle. If the good Lord Himself had been a railway engineer during the glory years of the mid- to late nineteenth century, he could not have plotted a finer route.

‘The Settle–Carlisle line is not a journey by rail,’ he famously concludes 72 Miles. ‘It is the journey of a soul.’ There was perhaps a slight tendency in all his work for Morley to wax unnecessarily lyrical but in his great paean to the Settle–Carlisle line his prose found its proper subject. The book combined perfectly his poetic instincts with his obsessive practical concerns. He was an expert on every aspect of the line, from the ‘long, tall’ Douglas fir and Baltic pine sleepers, to the ‘doughty’ granite chipping ballast, the ‘proud’ stations, the tunnels, the viaducts and the signals. And of course, alas, he became an expert on its tragedies.

I can imagine the journey that Miriam and Morley enjoyed on the way to Westmorland, the same journey as all our journeys: Morley seated in the back of the Lagonda, among his books and writing requisites, Hermes typewriter wedged into position on the portable desk, sharp pencils at his elbow and paper conveniently to hand, pouring endlessly forth like some magic fountain. His voluminous notes on the journey – including a ton or more of notebooks and index cards and papers for the putative book on the Great North Road, never published – are housed now, along with all his other manuscripts, in Norwich. There, in his favourite county, the ‘still centre’, the reader might recreate that journey from London to the Lakes, from the Whittington Stone at Highgate Hill, ‘memorial to Britain’s most benevolent citizen’, through the beauty of Welwyn village, home to Edward Young, author of Night Thoughts, and, according to Morley, echoing Dr Johnson, ‘perhaps England’s most defected genius’, and on and up past the famous Folly Gateway at North Mimms, stopping off for refreshments at the Roebuck at Broadwater, past the Caxton Gibbet, and on and on past Retford, Bawtry and Doncaster. Morley has often been described – and dismissed – as a mere antiquarian, a provincialist, a dull draftsman, a ‘topophiliac’, in the words of one particularly patronising critic in the Listener, devoted to places rather than to people, but he was also interested in the everyday lives of men and women, and in the chronological as well as the chorological: indeed, a part of his research for the Great North Road book includes dozens of typed pages on the history of the St Leger race, held annually since 1776, when it was won by a brown-bay filly sired by the mighty Sampson; the notes, like Morley, go on and on, and range wide and deep, a complete portrait of people in a landscape, a Brueghel in words. He was, in all his books, and certainly during my time with him compiling The County Guides, a celebrant of all that was living – though in reality our business was often with death.

My guess – though I can’t confirm it – is that it was probably Miriam who spotted the train in the distance. She wouldn’t have wanted us to beat her to Appleby. I can imagine her tossing back her head and stamping her elegant foot hard on the pedal. We must get there before him. Thank goodness she didn’t.

On the train I was showing the little girl how to work the camera. Her name was Lucy. She had a gap-toothed smile and freckles, little fat cheeks, and ringlets, and dark, dark eyes – a happy carefree face, the picture of innocence, a perfect Pears soap little girl. Her mother was dozing with the baby in her arms, the baby’s head resting gently on her breast. Lucy and I sang songs together and played games, and took it in turns to take photographs of the scenery. I took a photograph of her. She took a photograph of me. We whistled with the train’s whistle and knelt together on the seats as the world went rolling by, enjoying the freedom and the speed: the rocks, the stones, the trees, the farms, the sorry-looking Swaledale sheep.

Click.

Click.

Click.

It was one of those warm September days that seems like a bonus, that makes you believe that you still have another chance and that everything is not lost. We cheered as we reached Settle, laid out like a neat little pocket handkerchief under the pure blue sky. We passed a graveyard and then emerged into the vast Ribble Valley. We hollered our way through the long dark tunnel under Blea Moor and again as we reached the summit at Ais Gill, the vast cliffs opposite like something out of the American Wild West, the blazing heather and the dry-stone walls making everything appear as though it were wrapped and packaged and ready for presentation. Looking back, I wonder if that was perhaps the very last time I was truly happy: enjoying the golden stillness of the English countryside, mind and body relaxed and calm, moving inexorably forward and on and up towards the future and adventure. I had no thought then for London and what happened there. No thought for myself. I was moving on. I was in transit, a pilgrim journeying towards better things. Everything subsequently seems somehow darker, less good, lacking, broken and profane.

At a certain point, just before Appleby, the railway crosses the River Eden for the first time. I lifted Lucy up a little by the window, so that she could admire the river and the little viaduct with its piers and parapets and arches: twin wonders of nature and of human invention. A southerly wind blew the choking smoke away and we were granted a perfect view of Westmorland, ‘perhaps the most scenic county in England’, according to Morley. And so it is. I gave Lucy the camera and held her tight while she leaned out and took photographs.

The road swoops along and around from the railway approaching Appleby and in my mind’s eye I can see Miriam in the Lagonda, staring in dismay as we speed away before her. None of us of course had any idea that anything was wrong until things went wrong.

One moment we were upright, and then the next the carriage tipped and everything changed. I remember there being absolute silence before the screaming began.

In his short book about the history of the railways and their impact on the people and landscape of England, Morley’s Ringing Grooves of Change (1938), in a chapter entitled ‘Thundering Towards Our Fate’, he writes that ‘In our Steam Age, humans are becoming incapable of recognising the everyday. We value only the extraordinary. Trains themselves, for example, those astonishing creatures of such recent invention, exist now only in our consciousness and in the public imagination when they become untameable, when they become beasts, when they do damage or become derailed … It seems that in our time the railway accident,’ he concludes, ‘matters more to us than the railway itself. The crash, so much an admitted matter of course in railway travel, is becoming the condition of our culture.’

What follows is perhaps the most difficult and painful recollection from all my time with Morley. I will be as brief but as accurate as I can: the official records are of course available.

The only piece of paper I ever saw framed was Morley’s school leaver’s report, an extraordinary scrap of a document, yellow with age, which hung above his desk and which placed him unceremoniously in division ‘D’ among his classmates, numbered at number 30 out of 30. ‘Morley’s schoolwork this year, as in every other year,’ the report reads in its entirety, ‘has alas been far from satisfactory. His test work has been uniformly poor and his prepared work often worse. In mathematics a typical piece of prepared work scored 2 marks out of a possible 50. In other subjects his work is equally bad. He has often been in trouble because he will not listen but will insist on doing things in his own way. I believe he has ideas of becoming a journalist or a writer. On his present showing in English this is quite ridiculous. He is a boy in possession of eccentric ideas who does not respond to the usual disciplines. He may possibly be suited to employment as an apprentice in some trade that requires neither rote learning nor regular hours.’ Fair comments.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_6da9dbf2-8c04-54ca-9587-27a859955777)

PANDAEMONIUM (#ulink_6da9dbf2-8c04-54ca-9587-27a859955777)

IT WAS THE MOST VIOLENT COLLISION. There was a moment’s shudder and then a kind of cracking before the great spasm of movement and noise began. I fell forward and struck my head on the luggage rack. I was momentarily stunned and knocked unconscious.

When I came to I found we were all tilted together into a corner of the carriage – me, the mother and the baby. Our coach seemed to have tipped to the right, off the tracks, and become wedged against an embankment. What were once the sturdy walls of the carriage were now buckled and torn like the flimsiest material: the wood was splintered, the cloth of the carriage seats split, everything was broken. I remember I shook my head once, twice, three times: it was difficult to make sense of what had happened, the shock was so great. The first thing I recognised was that the mother and baby were both crying loudly – though thank goodness they appeared to be unharmed – and that the carriage was shuddering all around us, shaking and groaning as if it were wounded.

‘Are you OK?’ I said.

The woman continued crying. Her face was streaked with tears.

‘Are you OK?’ I repeated.

Again, she simply sobbed, the baby wailing with her.

‘We must remain calm,’ I said, as loudly and authoritatively as I could manage, above the sounds, trying to reassure both them and myself, willing them to be quiet.

‘Where’s Lucy?’ she said.

Where was Lucy?

I stood up, still rather disorientated and confused.

‘I don’t know—’ I began.

‘You have to get us out!’ said the woman, between sobs. ‘I have to find Lucy.’

‘OK,’ I said. I was still gathering my thoughts, trying to work out what to do.

‘GET US OUT!’ yelled the woman, suddenly frantic. ‘I have to find my daughter! You need to do something.’

I didn’t know what to do.

‘You need to do something!’ yelled the woman again. ‘Help us!’

The carriage continued to rock and sway all around us; clearly, we had to get out.

I looked around: the window was open to darkness and the tracks beneath us.

‘What’s under there?’ cried the woman. ‘Is Lucy under there? Lucy! Lucy!’ She did not wait for a response – she was hysterical. ‘Lucy! Lucy! Lucy!’

‘Look!’ I said. ‘You just have to let me check that everything is safe.’ I was worried that Lucy might be trapped beneath our carriage.

‘Lucy!’ wailed the woman.

‘Let me check if it’s safe!’ I said. ‘And we’ll find Lucy and we’ll get out!’

The shuddering and moaning of the carriage suddenly stopped and the baby paused in its crying and the woman looked at me as though having just woken.

‘You must stay here,’ I said, more calmly. ‘Just for a moment. I have to check if it’s safe. Do you understand? And then we’ll get out together.’

She looked at me, terrified.

‘Don’t leave us here!’ she said.

‘I’m not leaving you here. I’m just going to check that there’s a way out through the window and underneath the carriage and then—’

‘Take my baby!’ she said.

‘What?’

‘Take my baby with you and make sure he’s safe. I’ll wait here for Lucy.’

‘Look, if you just wait here for a moment—’ I began.

‘You’re not leaving us here!’ said the woman. ‘You take my baby and you look for Lucy and I’ll wait for her.’

‘But—’

‘You! Take the baby!’ she cried. ‘And you make sure he’s safe. And then you come back for me and Lucy.’

She was confused. She thrust the sobbing child towards me. I had no choice but to tuck him under one arm and crawl down with him through the window into the darkness underneath the train. If I got the baby out I could get the mother out. And then I could find Lucy.

Everything was wrong. It was dark, chthonic. There was a smell – a horrible sort of combination of hot metal and coal and oil and damp earth. I was breathing fast. It was as though we were being born. I made my way carefully with the baby underneath the carriage and across the tracks – I remember the rails somehow being greasy, with oil? – and then up into the light.

It was the most incredible sight: coaches were slewed across the tracks, rails were bent and twisted into terrible shapes, giant sleepers uprooted, the ballast ploughed through and scattered, and thick black smoke was everywhere. Passengers were emerging from their carriages and there were men running down the line towards us from up ahead. But what do I remember the most and the most clearly? It was the sound: the sound of birds singing. It seemed impossible, impossible that they could be heard above the din of breaking glass, and of grinding mechanical noises, and the rushing of flames, and the terrible cries of injured people, but there they were: birds, singing. It was like Spain, again. I deliberately took deep, deep breaths, trying to steady my nerves – and was struck suddenly by another smell, some sickening, thick, horrible smell that somehow I didn’t recognise.

I ran a few yards with the baby heavy in my arms. Now I could see the full length of the train: it looked like a buckled toy, as though having been tossed up and destroyed by some malevolent child. Up ahead was Appleby Station, with its proud sign and its fine passenger footbridge and over to my left were the station’s stables and cattle pens, the sound of the innocent animals joining the cacophony. And fire – fire was quickly spreading through the carriages, some of which had shattered entirely, stripped back to their thin pale wooden frames. It was a graveyard scene. It was pandaemonium.

Everything was wrong

One of the train guards was wandering up and down politely calling out, ‘Are there any doctors on the train? Any doctors on the train at all? Any nurses? Nurses? Any nurses?’ He might almost have been asking for passengers to present their tickets. A dining car steward was sitting down at the side of the tracks, stiff, stunned, blood on his starched white jacket, and – the most extraordinary thing – a refreshment trolley perfectly upright beside him, the Nestlé chocolate bars scattered around his feet, still glistening in their bright wrappers, broken cups and saucers like fragments of some vast whole. I ran over towards him and placed the crying baby in his arms.

‘Sir!’ I said. ‘I need your help. Sir?’

He looked at me blankly.

‘You must go up to the station and look after the baby,’ I said. ‘Yes? Until the mother comes.’

He continued to look at me blankly.

I repeated myself: ‘You must take this baby and go up to the station. Do you understand? I need you to get up and take the baby with you up to the station, yes?’

He looked at me for what seemed like a long time but then nodded and I helped him up and he began walking slowly along the line towards the safety of the station.

‘Go to the station with the baby!’ I yelled at him again – he glanced back and nodded – and then I ran and plunged back down under the carriage to help the mother. Soon the flames from the other carriages would reach us.

She remained exactly where I had told her, in the corner of the carriage, entirely still now, and white, panic-stricken.

‘Your baby is OK,’ I said. ‘A steward has the baby up at the station. We’re going to get you up to the station.’

‘Where’s Lucy?’ she said.

‘I didn’t—’

‘I’m going to wait here for Lucy,’ she said.

‘You can’t wait here,’ I said. ‘We have to go.’

‘But Lucy will come and try to find me here!’ She pressed herself into the corner of the carriage.

‘No. Lucy’s a sensible girl, she’ll know what to do. She’ll know where to find you. Come with me. Come on.’

She shook her head.

‘Now!’ I shouted, and I grabbed first one arm and then the other. ‘Now!’ I repeated, and she hit out at me and screamed but I wrestled with her and dragged her down and down through the window and under the train and up into the infernal daylight. As we emerged, a guard came staggering towards us, a terrible cut across his skull, his face sheeted with blood.

‘Where’s my daughter?’ the woman yelled at him, as if he were personally responsible. ‘Where’s Lucy? And my baby? Where’s my baby?’ She grabbed at the poor man, but he was in no state to respond and he simply pushed her away and staggered on past, entirely lost and silent.

I held the woman’s arms firmly. ‘Look at me!’ I said. ‘Look at me!’ And I looked deeply into her eyes, willing her to be calm and to understand and I explained that her baby was with the dining car steward up at the station and I told her to go on ahead, and that I would find Lucy and bring her to her.

‘You promise that you’ll bring her to me?’ she said, heaving with tears.

I promised. I promised I would find Lucy.

I can remember to this day the look she gave me – trusting, fierce, her eyes wide – and I can remember that she then gave a little jolt of resignation or offence, I don’t know which, as if she had been pierced or branded. Then she turned and walked on, joining what was now a long stream of men, women and children passing alongside the burning train, many of them dragging their suitcases and belongings with them, some of them silent, others calling out for loved ones, or weeping and wailing, dishevelled and distraught. This is the end of the world, I thought: this is what it looks like.

A man somewhere close by was frantically yelling for help. I turned towards the sound and ran over to the noise. Our carriage was now in flames and the fire was encroaching on the next carriage: the man was yelling from inside. I clambered and pulled myself up and onto the carriage, using all my strength, and made my way across to the window, which was filthy – and shut. I could see terrified faces inside: the man with his wife and children were trapped beneath me. The maroon skin of the carriage was warped and already beginning to warm with flames. It was like looking down into a nightmare from a nightmare. I tried to open the window, pulling and tugging, but it was jammed where the walls of the carriage had buckled.

‘Stand back!’ I yelled. ‘Stand back.’

The family disappeared from the window and I stood and attacked it with my heel, stamping and stamping with all my weight until the glass had shattered, until all that was left was a jagged gap in the glass and I could kneel down and one by one managed to help pull them free. They scurried up and out and over the ruined train and hurried up the line towards the station.

I jumped down and away from the train, exhausted. I tried to take my bearings.

There to my left was the station sign, ‘APPLEBY STATION’, and there was the station, with its big tall cast-iron water column, and the signal box on up ahead, and the signals, and to the right there was another large building, emblazoned with the words ‘EXPRESS DAIRY COMPANY CREAMERY’, the letters bold in red, with a fading image of a milk bottle substituting for the ‘I’ in DAIRY. And there, incredibly, was the engine, which had somehow parted company from the train and become embedded in this vast building, in the Express Dairy Company Creamery, milk flooding everywhere, soaking into the ground, lying in pools – black milk – and the crimson engine sunk and drowning, choking and gurgling like some dying animal, hot steaming coals sizzling in the darkening liquid. The engine’s chimney had gone, and lying by the footplate I could make out the figure of a man – the fireman? The driver? – lying in a pool of liquid, his clothes smoking, his shovel next to him. Metal. Flames. Machinery disassembled. Like the devil’s foundry. It seemed incomprehensible. Surreal. The stuff of nightmares and dreams – hashish dreams and opium nightmares.

And then I remembered: where was Lucy?

‘Lucy! Lucy!’

I began searching. I yelled and yelled and yelled.

The first thing that Miriam and Morley heard, apparently, was my voice. They were nearly at the station themselves when the train crashed and Miriam had immediately pulled the Lagonda over and run down to the line, Morley close behind her, already making guesses and calculations as to the cause. By the time I saw them there were men everywhere with shovels and pickaxes and rope, clearing the carriages, and Morley was taking notes, Miriam assisting with the injured.

The hours that followed seem now like a blur. Men rushing with buckets to douse the flames, and then the fire engine arriving, and the ambulance, and finally the police. ‘Ah, potius mori quam foedari,’ muttered Morley, or something. We were herded together in the tiny waiting rooms at Appleby Station, rumours and theories beginning to spread as quickly as the flames from the engine: the train had run into a stationary goods vehicle; hundreds were dead; no one was dead; we had collided with an oncoming train. It was the driver’s fault; the fireman; the signalman; it was a natural disaster; an act of God; a robbery gone wrong. There were terrible injuries, and great shock and tears, but there was also laughter and jokes – the appalling, disgusting, incomprehensible contradictions of humans thrown together in a crowd, first class, third class, and everything in between. I remember the young nurse who dressed my wounds assuming that Miriam and I were married – ‘Your husband’s very brave, madam, people say he saved a lot of lives. He’s a good man’ – and Miriam shooting back, as sharp as you like, ‘First, he’s not my husband. Second, as for him being good or not – in any sense – I couldn’t possibly comment.’ I think that’s what she said. I think I remember the nurse saying that I had lost a lot of blood and that she wanted to take me to the hospital for treatment, and my refusing, and Miriam arguing with me, and … but, as I say, everything was a blur.

The only thing that remains clear is the moment I found Lucy.

She had been flung through the window of our carriage at the moment of impact.

If I hadn’t lifted her to look at the River Eden she would have been with her mother and baby brother, safely recovering in Appleby Station.

But she wasn’t. She was lying in a field, twenty yards or more away from the crash, entirely peaceful, her pinafore dress spotless and clean. Dead.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_22def2e1-4b25-52c7-b5b7-12eb7f52a488)

WILD WEST APPLEBY (#ulink_22def2e1-4b25-52c7-b5b7-12eb7f52a488)

I THINK I’D KNOWN IT from the moment of the crash, but it was too difficult to comprehend. She looked so perfect. She looked unharmed. She lay on her back, looking up at the grey-blue sky. She could have been cloudwatching.

I don’t talk about it unless I’ve drunk a bit – a lot – and even then I don’t tell the full story. I never mention Lucy. I find ways to avoid it, to circumvent it, as I have always found ways to circumvent everything in my life. Finally writing it all down, I suppose, writing all this down, however feeble and forgettable it may seem, however anodyne and nostalgisome – one of Morley’s favourite words, one he’d invented, I assume – is just a way of reassuring myself that it all really happened, and that it really meant something, that everything was linked together, that it wasn’t nothing, and that it wasn’t waste, that she mattered, that we all mattered. Morley’s County Guides were designed as a bold celebration of England and Englishness: my recollections, I suppose, are some kind of minor, lower-case companion. If the County Guides are a scenic railway ride then my own work is the scene of the crash.

So, first we were gathered in Appleby Station, us survivors, our wounds tended in the waiting rooms, and a cup of tea for our troubles, and then we were escorted to various hotels in and around the town to give our statements and to be offered shelter for the night. We were billeted at the Tufton Arms Hotel, right in the centre of the town, down past some railwaymen’s cottages and across the River Eden. It was a short walk but it seemed like a long way, a desperate journey: some people in a hurry, some people going slowly; and many come to gawk at us; all of Appleby, it seemed, had come to find out about the crash. The police did their best to keep them away, but it was impossible to separate bystanders from survivors: we were all jammed together, shuffling forward as one. The only way you could tell the passengers from the locals was that the passengers all looked strangely alike, with that expression of surprise and horror from the moment when the crash had occurred.

‘I’ve not seen it like this since t’fair,’ said one woman, as I jostled my way past.

‘Folk turning out to gawk,’ said another. ‘T’ should be ashamed.’

People were not ashamed, but they were baffled, just as we were baffled. ‘What happened?’ came the endless murmur. ‘What happened?’

Lucy’s mother with her baby walked on up ahead of me, weeping. I made no attempt to go to her, to comfort her or to apologise: I simply lowered my head and walked on.

In Spain I had often suffered exactly the feeling of that afternoon in Appleby: of arriving in a strange town, and not quite knowing or understanding what was happening, and with the knowledge and feeling of already having done something terribly wrong, so that the whole place seemed alien and unkind, a foreign land inhabited by foreign people suffering their uniquely foreign woes in their uniquely foreign ways. According to Morley in the County Guides, Appleby is renowned for its beautiful main street, ‘more Parisian boulevard than English High Street’ but I must admit that on that first day I did not much notice its beauty, and which particular Parisian boulevard Morley had in mind is not entirely clear, since there are none, to my knowledge, that are furnished with butchers, bakers, chandlers, haberdashers, gentlemen’s outfitters, greengrocers and pubs; Paris, for all its allurements, is no real comparison for a prim and proper English county town. A finer and – as it turns out – more fitting comparison for Appleby might be with a Wild West frontier town, in florid English red stone.

The Tufton Arms Hotel had seen better days, though it was difficult to say exactly when those days had been. It was a sad sort of place: scuffed, worn moquette carpets, cheap and pointless marquetry, cracked clerestory lights, plush, dusty furniture; like a vast dull first-class carriage. The hotel bar was the centre of operations. Tea urns had been set out on some of the tables, and plates of bakery buns. There was much bustling and much organising being done: volunteers from the local Band of Hope had somehow appeared, with their own banner, and had positioned themselves in the hotel lobby, arranging places for people to stay, and drawing up lists and matching locals with passengers; the Women’s Institute were doling out the tea and buns; and the police had settled themselves in to conduct interviews. Morley later wrote in praise of the scene as a ‘model of modest English efficiency’. It may have been. It may have been a demonstration of all that is best in the human spirit, a triumph of calm over distress and of civilisation over human wretchedness. All I know is that it was thoroughly depressing and that I was desperate to get away. I needed a drink.

‘Yes, sir?’ asked the barman – one of those old-style hotel barmen, a professional barman, a middle-aged gent, spruce and natty, in a tight little tie and a bottle-green waistcoat. He might just as easily be a town councillor or a greengrocer.

‘Whisky, please.’

‘So, were you in the crash?’ he asked. My torn jacket and bloodied shirt, the bump on my head, and the ragged trousers must have been a give-away. I didn’t answer. ‘Very good, sir. Drinks are on the house for anyone who was in the crash.’

‘In that case make it a double,’ I said.

‘There’ll be no trains in or out for a week, I reckon,’ continued the barman, as he was examining the bottles behind the bar. ‘So I reckon we’ll be getting through a lot of port and lemon.’ He nodded towards the crowd around the bar, mostly women. ‘So, Scotch: we’ve got Haig, Black and White, or Macnish’s Doctor’s Special. Irish, I’m afraid we’ve only Bushmills or …’ He held up a full bottle of Irish whiskey. ‘Bushmills.’

‘I’ll take a Bushmills then.’ I had converted to Bushmills at one of Delaney’s places: he served only Irish whiskey, his famous gin fizz, and other drinks even more distinctly suspect and of no discernible provenance.

‘There was a little girl killed,’ he said. ‘Is that right?’

I said nothing. I drank the whiskey and ordered another. And then another.

I could see her face in the mirror behind the bar. I could see her smile. I could feel her hand holding mine. I could hear her asking questions. She seemed to be everywhere. But the more I drank the quieter she became. I also took a pinch or two of Delaney’s powders – and eventually she was silent.

Morley, hectic and inquisitive as ever, had conveniently situated himself at the far end of the table at which the police had made their makeshift headquarters – the perfect location for a quiet spot of eavesdropping. He was armed with a cup of black tea, and was busy with his pen writing in one of his tiny German waistcoat-pocket-sized notebooks. He had about him his usual glow. Miriam was smoking and surveying the room with a look of pity and disgust. I sat down with them. I felt sick.

‘Ah, Sefton,’ said Morley. ‘The hero of the hour.’

‘Hardly,’ I said.

‘Come, come, we’ve heard all about your exploits, dragging people from their carriages and what have you, saving lives—’

I got up to leave, but Miriam gripped my arm and forced me to sit back down.

‘He’s had a shock, Father. Best to leave it.’

‘Of course!’ said Morley. ‘Yes, of course, quite upsetting.’

‘I wonder actually if, in the circumstances, we should perhaps call a halt to the book, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘Agreed,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ said Morley, to my surprise. ‘Perhaps we should.’

‘Really?’ said Miriam.

‘Till tomorrow morning, perhaps?’

‘What?’ I said.

‘Otherwise we would slip very far behind in our schedule, Miriam.’

‘Our schedule,’ I said, with contempt.

‘Is something wrong, Sefton?’ asked Morley.

‘Father,’ said Miriam, coming to my rescue. ‘I was thinking we should perhaps take a longer break?’

‘Agreed. Again,’ I said.

‘A longer break?’ In all my years with Morley I rarely saw him riled or succumbing to petty rages, but this suggestion made him spiteful. ‘Do you both want us to give up then?’ said Morley. ‘Just because there’s been a train crash?’

‘No,’ said Miriam slowly, as if speaking to an ignorant child. ‘But you’re right: there has been a train crash.’

‘And what on earth do you propose doing when real disaster occurs?’ asked Morley. ‘As it surely will.’

‘Real disaster?’ I said.

‘A war, or a famine? Another Spanish flu? A crash is an accident. It may be a tragedy. But it is not, strictly speaking, a disaster. Do you know what a disaster is?’

‘I think I do,’ I said.

‘Has there been great loss of life?’

‘A little girl died, Father!’ said Miriam.

‘Which is tragic, but as I say, it is not—’

I moved to get up again and again Miriam held me back.

‘I’m sorry but I have no intention of continuing to work with you on this book at this time, Mr Morley,’ I said.