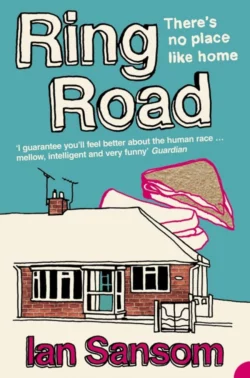

Ring Road: There’s no place like home

Ian Sansom

A warm, humane, and sharply observed tale of small town life that is by equal turns hilarious and moving.Big Davey Jones is coming home. He's been gone almost 20 years now, but nobody's forgotten him. Davey's a local hero – his miracle birth as the seventh son of a seventh son brought fame to this little town and they've been grateful ever since. But Davey's home town has changed much in the intervening years. The traditional family business like Billy Finlay's Auto-Supplies and Calton's Bakery and Tea Rooms have been replaced with 'Exciting New Housing Developments!' and even a nightclub called 'Paradise Lost'.The locals haven't changed much though. Bob Savory, who always had it in him, has made a million with his company Sandwich Classics, and he's branching out now, with an Irish themed restaurant on the ring road. Francie McGinn, the divorced minister at The People's Fellowship, is still trying to convert the town through his Fish-and-Chip Biblical Quiz Nights and his Good Friday Carvery & Gospel Night. And Sammy, the town's best plumber, is depressed as ever and looking for solace at the bottom of the whisky bottle.Clever, touching and, above all, utterly spot-on in its depiction of small town life, Ring Road is confirms Ian Sansom’s status as one of our most perceptive authors working today.

RING ROAD

There’s no place like home

IAN SANSOM

For my family

Contents

Cover (#ue71d221b-a854-544d-b1b3-4e0241bc2469)

Title Page (#uceb1399d-091c-581b-b740-796bebe6e32b)

Preface (#ud0ef4378-e965-5197-b0ce-c2809f244ab1)

1 The Seventh Son (#u24a2ce13-e177-5659-8176-03b9f64a722d)

2 Sandwiches (#ua26e7f16-fe5d-5070-87a5-3e781be7390d)

3 Jesus, Mary and Joseph (#ub07f9327-deae-52f2-897e-3b7b4501d9ae)

4 The Dump (#ua7b6e07e-b8ab-5179-af0f-cfba9dc630a4)

5 Fellowship (#u2f79f940-9c67-51a6-b9f2-93b442f97724)

6 Massive (#uc20f0830-e73c-5352-8604-cb82ae71a2e0)

7 Plumbing (#u226955af-3a49-5656-8b48-66b65b47ca49)

8 The Steam Master (#ubae4ee52-e362-55fa-a958-1708c96202fa)

9 Closure (#u8998cbe5-ac47-5da4-913c-0eae82cbc57d)

10 Print (#u29e50158-be8e-57e6-b4a7-d9d05ac9d050)

11 The Quality Hotel (#u3e1fe073-d77b-595c-b5a1-a99e6125eb37)

12 Unisex (#u68e33c0c-6408-51eb-ae0e-333f17fb9c4f)

13 Deep Freeze (#u9a635526-f678-52f7-be18-5c086606e7aa)

14 Self-Help (#ue33a263e-26c1-5453-95d1-f41fe21ee28b)

15 Line Dancing (#u9adc33dd-6ad4-5754-b41e-d611506e5041)

16 Speedy Bap! (#u352cfcbf-567c-57f8-b92f-fa43daf28ade)

17 Condolences (#ueefeb4d9-595b-562e-96b4-1619b5dbbd43)

18 The Bridal Salon (#ua71bf355-3f60-595a-98c2-f4bc2fbc299c)

19 Country Gospel (#u6db8dd66-0a68-53a0-aa71-650537ee2028)

20 Cigars (#u00d64952-5577-58db-9d5c-d43dd2acfbc9)

21 Christmas Eve (#u7b39dfea-5e13-5851-bc9a-d28e293ca93c)

Index of Key Words, Phrases and Concepts (#u0da49704-77c2-5eb8-80e6-3ed166ae0265)

Acknowledgements (#ua0ef2dfa-dd66-5f08-9249-e25618090172)

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features … (#ud16907c5-72f0-5a76-b29f-4026df914f1b)

About the author (#u6b6a99a6-2af6-5412-9499-4407d88eae31)

Q & A

Life at a Glance (#ulink_d2d059f4-13a6-5212-861d-844208c3e61e)

Favourite Books/Authors (#ulink_fd9b9264-b690-53e4-a745-0392537b7d4f)

About the book (#u62bc24c1-3fcd-56cb-810d-bedcec985932)

A Critical Eye

Sandwich Spread (#ulink_e9edbf59-490e-5cb7-8c9c-d01154963784)

Read on (#u8e803ae6-f2dd-5d8d-83cd-b137e58867f7)

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You’ll Like … (#ulink_c56f09d7-b9eb-5ffd-a171-a04aa18ef115)

Find Out More (#ulink_a217eacf-b518-5e0b-aa7b-3e404a68682e)

By the same author (#u2b79765d-7d65-51d8-9d8e-134feb0b2c89)

Praise (#uc0788ced-9c98-545b-bf2f-91742b514e29)

Copyright (#u273828ea-ad30-51a4-a9ac-4dab2d08c918)

About the Publisher (#ueb83753d-1946-5cc2-830f-29b3e265a390)

Preface (#ulink_f9e64cab-f8df-5d9a-af1f-cf8b9143e02d)

Containing the customary avowals, apologies, concealments of artistry, confidences, explanations and precepts, and a note on the tipping of winks

I worked on a farm once, when I was first married, in County Antrim, and one of the men I worked with had been in London doing the roads, during the early Seventies, at the beginning of the Troubles, and he claimed that things were so bad in those days that he would post ham in an envelope back home to his family in Belfast. I was never sure if he was having me on or not – it’s always difficult to tune in to another nation’s sense of humour, and I was an Englishman abroad – but I always thought it was a nice idea, and I like to think of this book as similar in some way, as the equivalent of some ham in an envelope, posted in reverse, from me here to you elsewhere, wherever you are. It’s probably like ham in other ways too, some people would say.

When I published my first book, The Truth about Babies (Granta, 2002), my wife said she’d only read the next one if I managed to make no mention of vomit, diarrhoea, urine, sperm and other bodily fluids, and I’ve done my best, although she may wish to skip a few pages… The index is designed for those with similar aversions or inclinations.

When I sent my mum a copy of the baby book she said, ‘That’s nice, dear,’ which is pretty much what she’s said to me since I first brought drawings home from school, and which still seems to me about the right response to anyone claiming to be an artist. These days, reticence is easily underrated. But then so is enthusiasm. When we were growing up my mum and dad provided for us children, they cooked good food for us to eat, they made sure we brushed our teeth and were polite, and didn’t watch too much television, they taught us how to make our own beds, helped us with our homework and pointed out interesting things when we were on long car journeys. Perhaps this last explains the footnotes.

The rest of the mechanics of the book are obvious, I hope, and require no further admissions or explanation. (Apart, perhaps, from the brief chapter summaries and epigraphs, which seem to me a mere practical courtesy but which I’m aware are currently out of fashion, and so may seem avowed and unusual rather than commonsensical or natural, like wearing spats, or clogs, or a smock. But fashions come and go – maybe if you keep the book in a cupboard in a few years’ time it’ll all be back in again.)

Writers are, of course, wilful and selfish individuals who only get away with writing because other people allow them the privilege, but I know from long experience that listening to writers saying their thank yous is a bit like listening to people pray or talking about sex – it’s not necessarily unpleasant and everyone does it sometimes, but you do wonder if maybe they could learn to do it in their own heads and in the privacy of their own homes. So I have left all my acknowledgements until the end. They are an apology as much as an explanation.

Anyway, I do hope you enjoy the book – it’s meant for you to enjoy. It would be presumptuous of me to say what it’s all about, or even to pretend that I know, although maybe you’ll understand if I say that as a child on summer evenings, on Sundays, our parents would often have relatives over for tea – this was before barbecues had arrived and when family lived close by – and my aunts and uncles would come and we would sit around the dining table, which now serves me as a desk, and we would eat sandwiches and salads, and we would talk and play games, and I would fight with my cousins, and I can remember that I was amazed that these people were supposed to be my relatives, people with whom I seemed to have nothing whatsoever in common. It was a long and painful lesson, undiminished even by crab paste and trifle, and I thought it would be good to write a book that somehow reflected those Sunday teatimes, and which would remind me of the many different ways in which people live their lives, which is what makes our lives possible.

It would be self-serving of me to say anything else, except perhaps that the town is not meant to be a replica of any particular place, although I believe it does exist, and that I’ve never met any of the people, although there are equivalents, and that each chapter can be read on its own as well as in relation to all the others, although I hope, of course, that you’ll read them all. There are no themes that I’m aware of and any obscurities are unintentional.

It seems necessary, finally, to apologise to the busy reader for this, a preface, which suggests either an uncertainty or an unnecessary formality on the part of the author, or perhaps both. Writers are traditionally opposed to explanation, since it diminishes the effect of the masterly voice and style, but I have always found it a hardship not to be helpful, which is a failing, I know, but it’s still better, I think, even now, with the effects of excess everywhere apparent, to be told too much rather than too little. Arrogance, bullying, puffery, rapacity, self-awe and the tipping of winks can get you a long way in life, and it seems to get a lot of authors further than most, but in the end I believe it’s better simply to be honest and to try to be explicit. And if you can’t be, you should at least try and pretend.

Thank you, again.

Bangor – Belfast – Donaghadee, 2003

1 The Seventh Son (#ulink_895be20b-4c6f-5cc2-902e-d7ab7036471b)

In which there is scenery and Davey Quinn returns to his home town, with some considerable determination, and is shocked at what he finds

‘That’s some weather we’ve been having.’ That’s what people say where I come from, when they don’t know what else to say, which is most of the time.

Once we get going we’re OK, but it can take us a while to warm up to a conversation – about five years is the average. In fact, in most instances conversation never quite catches fire, but that doesn’t stop us laying down the kindling, stating our good intentions, preparing for something that in all likelihood may never happen. We may never get round to the big blaze, we may never exchange a confidence or share a secret or speak out of turn, not even when fuelled by drink, which tends to leave us speechless and starry-eyed, stupefied rather than garrulous and overflowing, but still every day we will happily talk about the weather, and about our children, and about births and deaths and marriages, and thus recently, of course, about the return of big Davey Quinn, after nearly twenty years away.

Davey is famous in our town because he is the seventh son of a seventh son, which is a rare distinction anywhere but nothing short of a miracle here, where the population has been growing for as long as anyone can remember but where the family size is getting smaller – these days a seventh son seems not so much a hopeless indulgence as a sheer impossibility, or an embarrassment, even among the most devout of the dwindling and ageing congregation at the Church of the Cross and the Passion, where Davey’s parents still attend regularly and still give thanks for the fact of his wonderful birth, long after the event.

Davey, needless to say, does not share his parents’ enthusiasm and never has done. His is a distinction that he did not earn, and did not ask for, and it has proved to be a heavy burden for which he was quite unprepared. It would probably be fair to say that Davey Quinn has found his position in life more difficult to bear than most: his fame has taken its toll. The famous photographs that appeared in the local paper, the Impartial Recorder, can still be found framed in pubs and bars around town, places that like to fill their walls with the faces of local celebrities, as a warning and a witness, perhaps, to the meaninglessness and transitoriness of human life, for who now remembers our champion high-diver, Don Kennedy, who competed at the 1936 Munich Olympics, and who walked around town on his hands every morning and did marathon push-up demonstrations in the old market place (which is now the multi-storey)? Or even Barbara McAlesee, the Impartial Recorder’s ‘Woman of the Week’ as recently as 1979, who knitted scarves and hats from the fur of dead pets, and who appeared on the once popular Sunday night television programme That’s Life, and who exists now only in a faded newspaper cutting behind the counter at Scarpetti’s, alongside an example of her handiwork, a muffler, framed, made from the fur of the late Mrs Scarpetti’s terrier, Massimo? Or the McLaughlin brothers, the tap-dancing twins who danced their way out of town and into Broadway success in the chorus of the musical Hold on to Your Hats in 1943, which starred Al Jolson and Martha Raye singing ‘She Came, She Saw, She Cancanned’?

The most popular and much reproduced photograph of Davey shows him with his eyes sealed shut, wrapped tight in a blanket and stranded in the arms of his suited and black-spectacled father, with his six brothers in duffel coats and parkas crowding around in front, looking utterly fed-up, standing outside the old cottage hospital – formerly the soap-works – on Union Street, which is where all the Quinn brothers were born, two generations of them, and which is long since demolished, which has made way for an extension to what used to be the Technical College and is now the Institute of Higher and Further Education, and which may some day become a university, if the Principal, Hugh Scullion, has his way, which he usually does.* (#ulink_cce71bd9-9041-5b91-9657-4f60145be9c8)

From this great seat of learning, then, what was once that little cottage hospital, Davey Quinn made not only our local news, but the national news, and the international – within a week of his birth he had straddled the globe as evidence of God’s amusement and of the wonder of fornication. The midwife’s slap – Miss Carroll’s, as it happens, a lovely, jolly woman, who committed suicide a few years ago, the day after her retirement, a terrible tragedy and a loss which was felt by the whole town, many of whom she had brought to life with her own bare hands, with her renowned firm slap – and Davey’s cold cry seemed to carry from earth to heaven, and far across land and sea, as far, they say, as America, where his tiny features could be seen on news-stands from state to state and on the televisions of the nation.

These days parents might grow rich on the proceeds of such an extraordinary birth, but back then we were all innocent and little Davey was not regarded as a commodity – he was, rather, and to all of us, a gift. A commodity can at least be bought and sold – it is a free exchange. But a gift implies obligations: it is therefore difficult to refuse or to return. Poor Davey, the runt of the litter, a little miracle, an excitement in all four corners of the globe, was the fulfilment of a life’s ambition for his father, Davey Senior, as he became known, and he was therefore, naturally, a huge disappointment to him and hence to himself. Babies, if only they knew the dismal realms they were about to enter, would probably never heed the call and never leave those remote gold and silver coasts from whence they come and have their lodgings. They would pause, consider the darkness, and sit right back down again on their fat little hunkers and never cross the waters into memory and oblivion. Surely no being rushes to embrace its own apotheosis? Unless, of course, that being be man.

Some years ago Davey left to travel the world and to try to escape his unique privilege and responsibilities, to try to escape photographs of himself in pubs and bars, to find riches and even, perhaps, he told himself then, believing such to be possible, to find himself. He got as far as London, where no one believed him – they thought he was joking – if he told them he was the seventh son of a seventh son, even if they stayed around long enough to hear him tell, which was not often and certainly never when he or they were sober or during the hours of daylight, and so in the end it ceased to matter. The wonderful and the terrible, his colossal, inescapable self, became first hilarious and then irrelevant, and finally unmentionable. He found refuge in work and in friendships, and in all the usual and time-honoured traditions. He drank the cup to the lees and there was a vast blur, and in the crowd he became successfully, magnificently anonymous. Among the millions of other talebearers, he lost himself and disappeared.

I don’t know the exact circumstances which brought him to the point of return – there are rumours, of course – but he’s back and it’s good to have him back, and what people are saying is this.

He woke up, they say, and urinated bright red, which was a shock, I guess. Urine is usually yellow, wherever you’re from and wherever you’re living; it is one of life’s few constants, sometimes perhaps a little darker, sometimes perhaps a little lighter, but always yellow, even for the likes of little Annie Wallace and her family, and the Buckles, and the Hawkinses, and the Delargys, our town’s Jehovah’s Witnesses, who have long since forsaken the wicked pigmenting tints of tea and coffee and alcohol, and birthdays, yet whose holy and clean-living wee is still distinctly yellow. Davey Quinn’s urine that morning was a red-wine kind of a red, a welcome colour in a fine-cut crystal glass over a nice evening meal in a favourite restaurant, but never good on porcelain first thing in the morning, and so it was that Davey decided that it was time to come home. He’d been away long enough. His kidney was ruptured. They’d read him his last rites in the hospital, apparently, but he was out and about and fighting fit six weeks later – Davey is nothing if not a fighter – and the very next day he booked his ticket home.

He made it back via our so-called International Airport, which, it has to be said, is not noticeably International – there are tray bakes on sale in the gift shop, for example, and more copies of the Impartial Recorder than there are business books in the newsagent – but it has a reciprocal arrangement with a similar airport in the south of France and there’s a flight once a week, to and from, which grants them both their titles.

So Davey made it back safely and in some style, but alas his luggage did not make it. It’s always touch and go flying in here, whether you’ll arrive with what you left with. Most of us in our time have lost something in transit, even if it’s only our nerves or our resolve, usually because of the final descent, which requires a steep bank round and a sudden drop of altitude, when suddenly you see home and your stomach is in your mouth and you realise exactly how tiny it is, how small, your town, and your street, and your little house in your little street, how insignificant in the great scheme of things: it can be a sobering experience for someone just returning from business, or a weekend shopping trip or visiting relatives in a city, full of themselves and the complimentary drinks and the bag of nuts. Cities exist in and of themselves, and require no explanation, they just are. In a city you can kick back and relax, and you need only concern yourself with questions of who you are and what you are, and how you’re going to be more, and bigger, and better: if you’d ever attended the Philosophy for Beginners evening classes with Barry McClean at the Institute you would probably have called these empirical questions of essence and existence.* (#ulink_f07282ac-bd11-5e74-b414-0e829b11ab4f) A city, in other words, makes you a utilitarian. But when you look at our town you just straight away think to yourself: why? A small town can make you metaphysical.† (#ulink_7a0bf723-93c9-51d9-b4d3-0999e6a80f99)

Marie Kincaid, who lives in town and who commutes up to the airport, sees people facing up to this question every day, as they step off planes on to the tarmac and into the drizzle, and wonder exactly how they got here and whether there might possibly be a chance to go back. Marie is a Baggage Reclaim Supervisor: she calls the loading bay her Bermuda Triangle and her life is spent attempting to discover its many mysteries. Despite closed-circuit television and X-rays and searches, there’s still a lot of theft and loss of baggage: it’s almost as if the luggage knows something that the passengers don’t, and when they pass through on the conveyor belt at the point of departure they think, well, actually, I quite like it here, thank you very much, and I think I’ll stay. There is luggage belonging to people from our town in all the major cities of the world, living under an assumed name.

Davey had set off with two suitcases, which he’d somehow acquired over the years, graduating first from a grip to a rucksack. They were suitcases which Davey had never in fact used except to store his CDs and cassettes, which he’d sold before returning. He’d found it hard to part with some of them, not so much because he wanted to be able to listen to the music, but because he didn’t want to forget what it was once like wanting to listen to music, but then he thought, well, I have a working radio, what more do I need?* (#ulink_56745388-e04a-5c43-ad47-c58e54a6fbf2) What he needed was the money, so he sold his memories, and he reclaimed the suitcases from under his bed and packed.

In the airport, when everyone else had claimed their luggage and the carousel had shut down and his cases hadn’t arrived, Davey went to see Marie at the Baggage Reclaim desk and Marie smiled her widest, most uncompromising and half-humorous smile and said, ‘Nothing we can do about it, I’m afraid.’

Marie has had the opportunity to practise this particular smile over a number of years now, and it hardly ever failed to work its magic, even on non-native speakers of English. It was a philosophical smile, a smile that suggested that although the loss of luggage obviously caused her pain, she understood from a wider and longer perspective that it was a small matter and that you, the unfortunate but undoubtedly reasonable passenger, should regard it as a small matter also, for thus and this way, the smile implied, lay the path to enlightenment. Davey interpreted this complex smile correctly and filled in a pink form without protest under Marie’s benign gaze. The luggage, said Marie, might be over on the next flight. Or it might not. And then she checked Davey’s name and signature on the form, which was when it happened. ‘I know you,’ she said.

‘You do?’

‘Of course. I know you.’

‘Right,’ said Davey.

‘David Quinn?’ She wagged a finger at him.

‘Yes,’ said Davey.

She’d caught him: she had him bang to rights. ‘The son of David Quinn?’

‘Yes,’ he agreed mournfully. He knew what was coming.

‘The seventh son of the seventh son?’

What could he say? They were words that he hadn’t heard for twenty years and he could live without hearing for another twenty more. But he couldn’t deny it, although he’d hoped that perhaps he could have got away with it. He’d thought that if he stayed away long enough he might have become unrecognisable to the past, but it was not to be so; the past has a very long memory.

For most of us, for those of us who return home out of necessity, or in mere shame or pity, rather than in triumph and trailing clouds of glory or with our reputations preceding us, the journey home is always a disappointment. For most of us there’s never going to be ticker tape and no free pint, no surprise pick-up at the station or the airport, and the best we can hope for is a mild handshake from our father and a teary hug from mum. Which is never enough.

But Davey had wanted nothing more. He’d have been happy to creep back unannounced and unnoticed – a quick pat on the back, then pick up the car from the Short Stay car park and home for a nice cup of tea. That would have been just fine.

They say that everybody wants secretly to be recognised, but Davey Quinn really had wanted to be left alone and it had suited him, the years of anonymity, it had given him space to breathe and to get to know himself. Living away, he thought he’d finally begun to grow into his face, the jut of his own chin, the set of his own nose, the furrows of his own brow: he felt pretty sure that they all reflected his new, different, more secure sense of himself. He thought that he’d found the perfect disguise.

‘You haven’t changed a bit,’ said Marie, hand on hip.

‘Really?’

‘You get back a lot?’

‘I haven’t been back in twenty years,’ he said.

‘Living in London?’

‘Yes,’ he agreed.

‘You’ll see a lot of changes.’

‘Uh-huh,’ he said. ‘Right.’

‘I’ll see what I can do about the luggage,’ said Marie, picking up her walkie-talkie.

‘Thanks,’ said Davey, turning to walk away.

‘Honest to God, you look just the same,’ repeated Marie.

‘Good,’ said Davey.

‘And that extra bit of weight suits you.’ And then she spoke into the walkie-talkie. ‘Maureen?’ she said. ‘You’ll never guess who I’ve got here.’

There was a crackle.

‘David Quinn.’

And then more crackle.

‘Yes. Him.’

And then crackle again.

‘Maureen says welcome home. And Happy Christmas.’

‘Thanks,’ said Davey. ‘The same to you.’

It was getting late and he caught a cab. The driver was humming along to a tune on the radio, a typical piece of bowel-softening Country and Western, sung in an accent yearning for America but tethered firmly here to home. Davey sat down heavily in the back, dazed, and stared out of the window.

So this was it.

Home.

Marie was totally wrong. There weren’t a lot of changes. In fact, everything looked exactly the same: the same rolling hills, the same patches of fields and houses, the same roundabouts, the motorway. It was all just as he remembered it. A landscape doesn’t change that much in twenty years.

Or the weather.

It had been fine when they left the airport, but now the rain was sheeting down and about twenty miles along the motorway one of the windscreen wipers popped off – the whole arm, like someone had just reached down and plucked it away, like God Himself was plucking at an eyebrow.

‘Jesus!’ screamed the driver, having lost all vision through the windscreen in what seemed to be a massive and magic stream of liquid pouring down from the heavens, as if God, or Jesus, were now pissing directly on to the car, as if He were getting ready for an evening out, and they swerved across three lanes and pulled over on to the hard shoulder.

‘Did you see that?’

‘I did,’ said Davey.

‘Jesus Christ. Blinded me.’

‘You OK?’

‘Yeah, thanks. Yeah. I’m fine.’

The car was rocking now, as lorries passed by, and then there was a sudden clap of thunder in the distance.

‘You wouldn’t be any good at repairs, would you?’ asked the driver, turning round.

‘No, not really,’ said Davey.

‘Would you mind having a look, though? It’s just, I don’t know anything about cars. And this asthma.’ The man coughed, in evidence. ‘It gets bad in the rain.’ He reached for a cigarette, put it in his mouth ready to light it and waited, his hand shaking slightly.

‘Right,’ said Davey, who did look as though he knew about cars and who felt sorry for the man, who reminded him of his father: it was the shakes, and the cigarette, and the thickset back of the neck; the profile of most men here over forty, actually. ‘I’ll just go ahead then, shall I?’

‘I’d be grateful, if you would.’

Davey got out. The cars on the inside lane were inches from him, flank to flank, and the rain was busy pasting his clothes to him, and the wind was getting up, turning him instantly from safe passenger into a sailor rolling on the forecastle in the high seas.

He checked first round the front. The whole of the wiper’s arm had gone – just the metal stump remained – so he then made his way round to the rear and started pulling off the back windscreen wiper, in the hope he might be able to use it as a replacement. He managed to cut his hands on the fittings and the spray from the road was whipping up his back, but in the end, with a twist and a wrench, he managed to get the wiper off. And in so doing he dropped the little plastic lugs that had held it in place – they rolled on to the road – so there he was, big Davey Quinn, not an hour back home, down on his knees, soaked to the skin in the pouring rain, reaching out a bloodied hand into a sea of oncoming traffic.

It was no good. They were out too far and the traffic was too heavy. He gave up. He got back into the back seat, drenched, defeated, and dripping wet and blood.

The driver was smoking. ‘Good swim?’ he asked, chuckling at his own joke. ‘No luck?’

‘No.’ Davey reached forward and gave the driver the back wiper. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘You’re all right.’

The driver called into his office on the radio. They’d send someone along with a spare. It might take a while, maybe an hour or so.

An hour.

Davey thought about it.

Davey had been thinking about coming home for as long as he’d been away – there was not a day went past when he didn’t think about it – but it was a journey in which irresolution might still easily overtake him. He had enough money in his wallet and on his cards to be able to go back to the airport right now and get the next plane out, and maybe wait another twenty years before returning. He was, therefore, a man who could not afford to hesitate.

The time was now or never.

He’d come this far: he was going to have to keep going. He was going to have to maintain his velocity.

He said he’d walk the rest of the way.

‘Walk?’ said the driver.

‘Yeah,’ said Davey.

‘As in, on your feet?’

‘Yeah,’ repeated Davey.

‘Walking? In this rain?’

‘Yes,’ said Davey one more time.

‘Are you joking?’

‘No. It’s not far from here, is it?’

‘Next exit. He won’t be long, though, with the spare.’

‘No, I’ll push on, I think.’

‘Well, it’s your decision, pal. What’s the hurry?’

‘I just …’ Davey couldn’t explain it. ‘I need to get back. What do I owe you?’

‘Well, I’ll have to charge you full fare and extra for the damage to the wiper.’

‘Right,’ said Davey. He believed him.

‘No, I’m having you on!’ said the driver. ‘Jesus! Where have you been?’

‘London,’ admitted Davey.

‘Well,’ said the driver philosophically. ‘I’ll tell you what. This isn’t London. We’ll call it quits. OK?’

‘OK,’ said Davey. ‘Cheers.’ People at home, he thought: they were the salt of the earth.

‘Happy Christmas,’ said the man as Davey slipped out. ‘And good luck.’

Davey had made it about half a mile and halfway down the slip road in the squall and rain before he realised that he’d left his little rucksack, his only hand luggage, in the car.

The rucksack contained a bottle of whiskey for his parents, a bottle for himself and his wallet, stuffed with cash and cards.

He turned and walked back towards the car, in the face of the traffic spitting up fountains in his face.

The car had gone – there was just a wiper on the hard shoulder to mark where once it had been.

So this was how it was going to have to be. He was going to have to return, as he had left, with nothing and in ruin.

He put one foot in front of the other and set off in the wake of the cars’ slipstream.

It’s a long walk from the motorway to the outskirts of our town – an hour, maybe two, I’m not sure, it’s not a walk I’d care to take myself – but eventually in the distance, on that profound horizon, Davey saw the golf club, the outskirts, with its big stone sleeping lions and its 20-foot forbidding hedges, and there was probably a good half-inch of water in his shoes by this time, and his clothes were like wet canvas as he stood and rested his hand on the head of one of the lions and gazed at the entire grey town down below him.

A lot can change in a small town in twenty years. In twenty years men and women can do a lot of damage. There is no mildness in the hearts of small-town councillors and planners, and you should never underestimate what small-town people are capable of. You can double it and double it again, and keep on going with your calculations until you think you’ve achieved the unimaginable, and still you’d never come close. Any estimate will never match up to the extraordinary outstretched reality.

The people of my home town have outdone themselves. We have exceeded all expectations. We have gone further than was absolutely necessary. We have confounded probability and ignored all the maths. We have been reckless and we have been greedy, we have eaten ourselves alive, sucked the very marrow from our bones, and spat out the remaining pieces.

Davey was amazed. He was heading straight for the centre of town, past all the old landmarks – Treavy’s second-hand cars, Pickering’s the monumental masons, McKenzie’s broom factory and the old planing mill, where they used to stack the sashes and doors outside under a huge tarpaulin canopy, and J. W. John’s, the big coal depot, where the coal would sometimes fall over the wall, and we’d go to collect it and bring it home, or dig pits in the woods and gather kindling and try to make fires.

They’re all gone, of course – Treavy’s, Pickering’s, McKenzie’s, John’s. There is nothing of them remaining at all. It’s been quite a clearance. Even the long steep road Davey was coming in on, shin-deep in mud and puddles, what used to be Moira Avenue, a mazy S-shaped road flanked with trees and the cast-iron railings protecting the town’s little light industry, is now a straight flat dual carriageway with housing developments tucked up tight behind vast sheets of panel fencing on either side, a good quarter of a mile of soft verges and For Sale signs.

At the very end of the road, a road Davey no longer recognised but which he now alas knew, every foot-aching inch of it, at a big new junction with four sets of lights where the water had formed in deeper puddles, was the Kincaid furniture factory. Or rather, was the Kincaid furniture factory. There’s nothing there at all now. Just mud, and sprouting weeds, and a sign, ‘COMING SOON: EXCITING NEW DEVELOPMENT OF TWO AND THREE BED HIGH-SPEC TURNKEY FINISH TOWN HOUSES’, with a high-spec view, it should be noted, of the health centre car park, Macey’s the chemists, and Tommy Tucker’s chipper, which have all survived the clearances.

Molested by the remorseless rain, Davey Quinn waited for the little green man to tip him the wink, then he crossed over into the centre proper.

The old fire station is still there, but it has been converted into apartments – ‘LUXURY, FULLY FITTED APARTMENTS’, apparently, and two of them still for sale. The big tower where you used to see the long red hose hanging down to dry – what we called God’s Condom – is long gone.

Some things, though, remain. Down Bridge Street, past the bus station and the train station and the Chinese takeaways, the old Quality Hotel, our landmark, our claim to fame, still sits on the corner of Main Street and High Street, in all its glorious six storeys, with its balustraded parapet, its castellations and gables, its mullioned windows and square corner turrets, and its flat-roofed concrete back-bar extension and basement disco, the site of so many breathless adolescent fumbles and embraces, a place where so many relationships in this town were formed and celebrated, and where so many of them faltered.

It is completely derelict, of course, the hotel, just a shell these days, a red, rain-soaked crust held up by rusty scaffolding poles and a big 10-foot sign on one of the crumbling turrets announcing that it has been ‘ACQUIRED FOR MAJOR REDEVELOPMENT’, no one knows exactly what. The peeling red stucco is stained with pigeon shit. It’s a wreck, but at least it’s still there. Like a lot of us, in fact.

Sitting, as if in commentary and judgement upon it and upon us, directly opposite the hotel and facing our only remaining free car park, are the new offices of the Impartial Recorder, our local paper, a journal of record, housed in a three-storey concrete building in the popular brutalist manner, with its red neon sign announcing both its name and the additional words, ’COMMERCIAL PRINTERS’.

Shaking now, with the cold and the shock, Davey set his face against the prevailing winds and the haze of rain, and prepared for the final drag before home, up Main Street. Past Duncan McGregor’s, the tailor and staunch Methodist and gentleman’s outfitter. Past the five bakeries, each offering its own speciality: the lovely treacle soda bread in the art deco Adele’s; the Wheaten’s miniature barnbracks; the ginger scones in Carlton’s Bakery and Tea Rooms; the big cheese-and-onion pasties in McCann’s; the town’s best fruit cake in Spencer’s. Past the four butchers, including Billy Nibbs’s dad, Hugh, ‘H.NIBBS, BUTCHER AND POULTERER’, with its large stained-glass frontage and its mechanical butcher forever cleaving a calf’s head in two, and McCullough’s, ’ALSO LICENSED TO SELL GAME’, with its hand-painted legend, ‘Pleased to Meet You, Meat to Please You’. Past the nameless paint shop that everyone called the Paint Shop; and Orr’s the shoe shop, and McMartens’, their competitors; past the small bookshop, known as the Red Front because of its pillar box flaky frontage; and Peter Harris Stationery; and Noah’s Ark the toy shop; Maxwell’s photographers; the entrance to the old Sunrise Dairy; King’s Music, run by Ernie King and his son Charlie; Priscilla’s Ladies Separates and Luxury Hair Styling; Gemini the Jewellers; Finlay’s Auto-Supplies; Carpenter’s tobacconists; the Frosty Queen, the ice cream parlour, which featured an all-year-round window display of a plastic snow-woman; and the Bide-A-While tea shop, famous for its cinnamon scones and its sign promising ‘Customers Attended in the Latest Rapid Service Manner’.

All of them absent without leave. Gone. Disappeared. Destroyed.

And in their place? Charity shops for old people, and blind people, and poor children, and other poor children, and people with bad hearts, and cancer, and dogs; amusement arcades; chip shops; kebab shops; minicab offices; and a new club called Paradise Lost whose entrance features fibreglass Grecian columns and a crude naked eighteen-foot Adam and Eve, hands joined above the doorway and Eve mid-bite of an apple the size of a watermelon; and deep, deep piles of rubbish in the doorways of shuttered shops. Just what you’d expect. A street of bright plastic and neon shop fascia, holes, gaps, clearances and metal-fenced absences. Main Street had once been called what it was. But now, what could you call it? It hardly deserved a name. The old cast-iron street sign has long since vanished.

Virtually drowning now, breathing water and no part of him left dry, Davey managed to accelerate his march and reached the brow of the hill.

The Quinn family bungalow used to be on the edge of town, an outpost, past the People’s Park and the old council offices, part of a small estate looking proudly over its own patch of green with swings and a slide and a see-saw, and a small football pitch with its own goalposts, which was marked out twice a year by the council, and looking out back over trees and fields.

It’s still there. The family home remains. It hasn’t gone anywhere.

But it no longer sits as a promontory and is no longer proud. It has been humbled and made small, bleached and filthied not only by the passing of time and the fading of memory, but by the ring road, which has stretched and uncoiled itself around our town, its street lights like tail fins or trunks uplifted over and above in a triumphal arch, leading to mile upon mile of pavementless houses – good houses, with their own internal garages – and to our shopping mall, Bloom’s, the diamond in the ring, our new town centre, the place to be, forever open and forever welcoming, the twenty-four-hour lights from its twenty-four-hour car park effacing the night sky, ‘Every Day a Good Day Regardless of the Weather’.

The sky was erased and empty, high above the red-brick new estates, as Davey Quinn pushed open the rusty gate – which used to be red – and went to ring on the door of his family home, the prodigal returning. The varnish on the poker-worked wooden sign by the door has long since peeled away, revealing the natural grain of the wood, made pale by the sun and the wind, and swollen by rain, but the house name is scorched deep enough and black enough, and you can still see it clearly from the road: Dun Roamin’.

* (#ulink_91eed8e9-2a8a-526a-b45e-8809b5d1e40e)Hugh Scullion, it should be explained, for those from out of town, is a man with a mission and a man with a mission statement (see the Impartial Recorder, 4 December 1999, ‘Principal’s Millennium Message’). Hugh has many, many chins and he wears novelty socks. He has a B.Ed, and an M.A., and twenty years solid in RE. behind him, but most importantly he has energy and he has opinions, and he has made our Institute what it is today, a county-wide centre of excellence, a ‘provider of a full portfolio of Higher and Further Education programmes’ according to its prospectus, and where once the Quinns were pushed and squeezed and forced out into the world it is now possible to take a night class in Computing or in Accounting or in various Beauty Therapies, taught by accredited professionals, and with concessionary fees available. Early booking advised. Enrolment throughout the year.

Some of the Institute’s courses are, of course, more popular than others: Conversational Italian, for example (Thursdays, 7.30–9, in the Union building), taught by the town’s remaining Italian, Francesca, daughter of the Scarpettis, who themselves returned to Italy long ago, while Francesca remained and married a local man, Tommy Kahan, a local police officer and the proud possessor of what is almost certainly the town’s only degree in sociology. Francesca herself is now of a certain age but of undiminished charms and her class is always oversubscribed. Philosophy for Beginners, on the other hand (Wednesdays, 7.30–9, in the demountable behind the main Union building), taught by Barry McClean, the local United Reformed Church minister, is consistently cancelled, due to lack of interest: he’s under pressure to change the course title in the Institute brochure to something like ‘Money, Sex and Power’, which should draw in the crowds, and then he could teach them the Nicomachean Ethics, Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason and Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil just the same. Class numbers would probably fall off in the first couple of weeks, but all fees are paid up front, so by the time the students realised it’d be too late. This raises an ethical dilemma for Barry, but Hugh Scullion has pointed out that the only ethical dilemma he’s facing at the moment is whether or not to do away with the teaching of philosophy altogether and to replace it with more courses in subjects that people actually want to study, such as Leisure and Hospitality Management, and Music Technology. Barry is currently seeking advice and consolation in the pre-Socratics. His wife is encouraging him to take more of an interest in gardening. Fortunately, the Institute runs courses and Barry is entitled to a discount.

* (#ulink_3ee3410d-9882-5ac4-9be1-32b81120b6f3) Philosophy for Beginners, Week 1, ‘Ethics’.

† (#ulink_3ee3410d-9882-5ac4-9be1-32b81120b6f3) Philosophy for Beginners, Week 2, ‘Metaphysics’.

* (#ulink_ae1d41c1-547c-5538-a195-36b8b818e0d3) He certainly did not need Prince’s Lovesexy, he realised, or Deacon Blue’s Raintown, or the Smiths’ World Won’t Listen, or Simple Minds’ Once Upon a Time, or Marillion, or the Fatima Mansions, or Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, or Blue Oyster Cult, or the Cult, or John Cougar Mellencamp’s The Lonesome Jubilee, or Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians’ Shooting Rubber Bands at the Stars, CDs he could not possibly imagine or remember himself ever having wanted or set out to buy, nor any of the dozens of home-made compilation tapes marked simply ‘Various’, or ‘Happy Daze’, or ‘Paul and Keith’s Rave Spesh’, on grubby BASF Chrome Extra II (90), and SONY HF and BHF (90), and red and white TDK D90, and Memorex dBS+, and AGFA F-DXI-90 and featuring almost exclusively the music of James, the Stone Roses, the Wonder Stuff, REM, and the Housemartins, and also, invariably, Primal Scream’s ‘Loaded’, The Farm’s ‘Groovy Train’ and Carter the Unstoppable Sex Machine’s ‘Sheriff Fatman’.

2 Sandwiches (#ulink_cafac21e-70ee-5400-ba6e-fdb9bfe5c5d2)

A short account of Bob Savory – his life, his times, his knives, his mother, his capacity for self-enriching, self-reproach and his famous bill of fare

The wind would near have knocked you over. It was gale-force. Bob Savory lost two trees in his grounds: an oak that was older even than the house, and a silver birch by the far pond. Bob has grounds and an old house. He has ponds both near and far. Bob is an old friend and, much more than any of the rest of us, Bob has made it. Bob has it all. Bob has trees that are not leylandii. Bob has done what seems so difficult to us, but which seems so natural to him: he has made money.

Bob is a successful local businessman, possibly the most successful local businessman around here since the titled landowners and gentlemen farmers and the great whiskered industrialists of centuries past, when our town used to make all its own and look after itself, when you might be able to sit down in your local after a long day’s work and eat local cheese with your local bread and your local pint in your local tweeds and your local linens round a roaring fire made from the local logs and then nip upstairs to get a good old-fashioned seeing-to and a local disease from a good old local girl, and you’d probably be dead by the time you were forty.

There were reminders of those good old days everywhere when we were growing up, from the big brick warehouses up on Moira Avenue and the polished red granite-fronted offices on High Street, with their huge carved bearded heads over the ornate archways, right down to the hole-in-the-wall boot scrapers and the cast-iron corner bollards and the old drinking fountains at the bottom of Main Street by the Quality Hotel, served by taps in beautiful shell-shaped niches, and the big stone trough for horses, which were all removed for the car park and road-widening scheme years ago, and which no one has seen since – although some people say they now sit as ornaments in the garden of our ex-mayor and council chairman, Frank Gilbey, a man who presided over twenty years of unrestrained and unrestricted planning and development during the last decades of the twentieth century, a man whose name will live on as the mayor who cut the ribbon on the ring road and opened Bloom’s, the mall, and changed for ever the face of our town. Everyone knows the name of Frank Gilbey, a man who owns a chain of hairdressers and lingerie shops throughout the county, and who has a roundabout on the ring road named after him. His name will live on, Councillor Frank Gilbey, while the names of those nineteenth-century giants, the great entrepreneurs and philanthropists of the past, which once were everywhere – Joseph King and Samuel Jelly and James Whisker, written above offices and shops, and given to parks and streets and community halls, and on all our school cups and certificates – are now hidden and obliterated.

Bob Savory’s fame and fortune may not last for ever but for the moment he is rich and famous and successful, an intimate even of Frank Gilbey’s, a business associate, a partner with Frank, in fact, in a number of prestigious developments, a local son to be proud of, and when people ask him what is the secret of his success – which they do, about once a month, in the Impartial Recorder, our local paper, which likes to do its best for local business and for whom Bob is about the closest thing we have to a living, breathing, home-grown celebrity, with all his own hair and an actual jawline – he smiles his big perfect white smile, the result of years of expensive cosmetic dentistry and worth every penny, he says, and he looks straight at the camera and he says just one word: sandwiches.

Sandwiches, sandwiches. White or brown, hot or cold, rolls, baps, tortilla wraps, subs and bagels, croissants, pittas, panini, it really doesn’t matter what to Bob, as long as you can eat it with one hand and the filling doesn’t drip down on to your shirt. So no hot cheese or scrambled egg, and no loose meat, but just about everything else: Brie, bacon and avocado, turkey and ham, egg and onion, tuna and onion, tuna and anything, all-day breakfasts, double – and triple-deckers, roast beef and horseradish, roast vegetables and mozzarella, chicken and prawn and cold sausage, every imaginable combination of cheese and meat and bread, smothered in every kind of mayo and mustard and sauce known to man, and some unknown, some made to a secret recipe known, they say, only to Bob, and handed down from generation to generation. Bob knows everything there is to know about sandwiches. He is our sandwich king, the prince, the lord, our contemporary Earl of Sandwich. When it comes to sandwiches Bob just seems to know what people like. He has a sixth sense. He has an instinct.* (#ulink_4841842e-fe5d-529e-990d-3c7a20fbf859)

I can remember when Bob was just getting into the catering business, or at least had gone into a restaurant and got himself a job, which is perhaps not quite the same thing, but it was a pretty big deal around here and in retrospect it was clearly the beginning of great things for Bob Savory.

Most of us when we left school had ambitions only to get out of town and maybe go to London, to Soho, to get to see inside a sex shop, visit some record shops, and maybe get a place of our own with a few lifelong friends and be able to stay up all night, drinking and listening to loud music, and meeting girls we hadn’t been to school with, girls who maybe worked in the sex shops, or who, like us, were just in browsing and who weren’t going to be afraid to explore their sexuality. But when it came to it we were content to end up working at the local garage, or on the sites, or going on to the Tech if we had the grades, and living with our parents until they kicked us out, and marrying the sister of a friend, and losing touch with our ambitions and our record collections, but Bob always had a firm plan and a purpose, right from an early age, and he never changed his mind and he never got distracted.

I remember seeing him the day he’d just bought his first set of knives and the look on his face, when he unwrapped them in the pub, to let us all admire: it was the look of a man who knew where he was going in life. It was the look of a man with a sharp knife in his hand and the future before him like a lamb to the slaughter. Bob’s knives were not like the knives our mothers had at home. Bob’s were German knives, made from high-carbon steel, with three beautiful silver rivets in the handles, not like they were ordinary rivets just holding the thing together, but like they were meant to be there, like they had been ordained, three perfect eternal rings, and Bob sat with us in the Castle Arms on the red velour, with these six-and ten-inch blades, and he rolled up his sleeves and he raised his hands, like the priest with the host, and he balanced the knives on his middle finger, one by one, and they perched there, like beautiful shiny birds come down to rest. They’d cost him his first month’s wages and then some, but he was as proud as you would be if you’d just met the woman of your dreams, and he handled those blades with exactly the same kind of care and attention, gazing at them fondly, and perhaps a little shyly, imagining their future life together. Bob told us you could get all sorts of different knives, knives of every size and for every purpose. He said there was even a knife called a tomato knife, for cutting tomatoes, and of course none of us had ever even heard of such a thing as a tomato knife, and we laughed at him and joked about all the other knives he should get: how about an egg knife, we said, where’s your cucumber knife, Bob, and your lettuce knife, and your knife for the cutting of toasted ham and cheese sandwiches, huh, and he rolled up his knives, in this brand-new beautiful thick green roll of material, and tied them up with their new strings, and we never saw them again, and that night we went back to our parents’ houses with their plastic-handled cutlery and tried to balance bread knives on our fingers.

We were silly to scoff. These days Bob has his own catering company, Old-Fashioned Foods (Cooked the Traditional Way), and a subsidiary called Sandwich Classics. He has a fleet of vans he runs out of the industrial estate, up by the new fire station, and the motto on the side of the sandwich vans says it all. The signs read ’SANDWICH CLASSICS AND SNACK FOODS FOR THE DISCERNING PALET’.* (#ulink_3faf4a28-aa58-5753-88dc-a05928e14a6a) The sandwiches are Bob’s big earner. They go the whole of the length and breadth of the county. He’s talking about setting up a franchise.

Bob also has a stake, a small but significant financial interest, in the big new Irish-themed restaurant out on the ring road – the Plough and the Stars they call it – which offers delicacies such as Turkey O’Toole, and Flannigan’s Fish Sandwich, and Banbridge Cajun Chicken Tagliatelle, ‘chunks of tender local chicken dusted with cajun spices and served on a bed of tagliatelle, covered in a creamy white wine sauce (vegetarian option available)’. It’s good. Or at least it’s profitable. People flock to it in their cars, on their way to or from Bloom’s, the shopping mall, and the DIY superstores and the big new private gym, the Works, which is right next door. The central feature in the Plough and the Stars – which was advertised on opening in a full-colour two-page centre spread in the Impartial Recorder as, ’AN ARCHITECT-DESIGNED WAREHOUSE-STYLE EATING EXPERIENCE’ – is a fibreglass whitewashed cottage with three-foot-high animatronic leprechauns who enter and exit on the quarter-, the half-hour and the hour, singing ‘Danny Boy’, ‘Galway City’ and ‘The Bard of Armagh’. The words of the songs are on the back of the laminated menus and most customers are happy to join in, as long as their mouths aren’t full of ‘The Kerryman’s Garlic Bread (made with fresh Kerry butter)’, or ‘Belfast City Trifle’ and sometimes even when they are.

Bob lives outside town, far from the Plough and the Stars, beyond the ring road, in a house set in its own landscaped grounds, now minus two trees, with outbuildings, and its own jacuzzi, and a games room with a pool table, and table tennis, a minibar, genuine antique furniture and original art on the walls, and a hallway so vast that in the winter he lights a big fire and has carol singers, a twelve-foot Christmas tree, and he invites us all round with our children to play party games, and he sits on this antique chair he calls a gossip-seat – and who are we to argue? – dressed up like Santa, handing out presents, like the proverbial lord of the manor.

Bob has definitely made it.

But Bob is not a satisfied man. Of course, the secret of Bob, the glory of Bob, is that he’s not a satisfied man: if he were a satisfied man he’d be just like the rest of us, living in a semi off the ring road, treeless and jacuzziless, and those with a ‘discerning palet’ would be cheated of sandwich classics and old-fashioned foods (cooked the traditional way). Bob works seven days a week, fifteen, sixteen hours a day, talks endlessly on his mobile phone and he hasn’t taken a holiday in years, not since he paid for a group of us to go on holiday with him to a resort in Spain, which was not a success, which was a disaster, in fact – he paid our fares and our accommodation, but he made it clear that we would have to pay for our own food and drink and entertainment, and I think, to be honest, some of us felt cheated, as if Bob should have gone the whole hog and paid for everything, as if he owed us something, and those of us who didn’t feel that probably felt that we owed him something, so in the end everyone was dissatisfied. Generosity can be hard to bear and a generous friend can be a burden. Harry made a joke one night when we were in a club in Marbella that the whole thing was probably tax deductible anyway, so it didn’t really count, and Bob left the club, caught a cab straight to the airport and we didn’t see him for months afterwards.

Not that Bob is lonely, or that he needs our company. He’s had relationships with many women over the years – many many women – and he’d like a family of his own, he says. He’d like a big family – a dozen children he reckons he could cope with – but he’s not yet found the right woman. He’s getting older, of course, like the rest of us, but the women seem to have stayed around about the same age – early twenties, which is undoubtedly a good age, nothing wrong with it at all, and none of us would wish to deny Bob or his female friends their various pleasures, but you can’t help but think that even the young can get stuck in a rut. In fact, the young may even be a rut. At the moment Bob is kind of stuck on waitresses – from the Plough and the Stars mostly. As well as his investment in the business, Bob is employed by the restaurant as something called a Menu Consultant, which seems to mean nothing except that he gets to hang out in the kitchens occasionally, and to meet the waitresses and drive them home – he drives a Porsche at weekends and a BMW during the week – and for the first few weeks everything goes fine, but after a while the young ladies always want to talk, and Bob never has much to say. Bob is a doer rather than a talker or a thinker and at the end of a day he just wants peace and quiet, and a little bit of rest and relaxation. He does not want to sit and talk about the state of the world or the state of play between man and woman. He is not a man who enjoys contemplating his own navel: he would rather be contemplating someone else’s. So pretty soon he finds himself driving someone else home from the restaurant and the waitresses find themselves waiting tables elsewhere. As a consequence, the Plough and the Stars enjoys a rather high staff turnover, and the loyal front-of-house manager, Alison, says one day they’re going to run out of young women in the town to employ and they’ll have to start importing them. Bob thinks that this would not be such a bad idea.

Now Bob is, of course, a rich man, a millionaire, although, as he points out, being a millionaire these days is nothing special. Virtually everyone is a millionaire these days, according to Bob, or they could be. Bob reckons he needs at least another £2 million to be really comfortable. He’s got it all worked out. With an extra £2 million, maybe a little more, he could afford to live the rest of his life on about £120,000 per annum. Which would be quite sufficient, as long as you’ve cleared all your major debts. And Bob has cleared nearly all his debts. Except for one.

His mother.

Bob is an only child and his dad, Sammy, Sam Savory, a wiry man with a thick head of hair and as thin as a whippet and as strong as an Irish wolfhound, died a few years ago. He was a sheet-metal worker. He worked hard all his life and then he got cancer and was dead within six months of retiring. Mesothelioma – a cancer caused only by exposure to asbestos. It was not a good death. It was an industrial death. Bob paid, of course, for private nursing, but it couldn’t save Sam, and Bob’s mum Maureen was ashamed: she felt her husband should somehow have known he was working with asbestos and should have been aware of the dangers, even before anyone knew there were dangers. She blamed him and so did Bob. They felt that it reflected badly on the family. It’s difficult sometimes to feel sympathy for the dead and the dying. Sometimes, when someone dies, even someone close to you – especially someone close to you – you just think, how dare you? And in Bob’s case, and for his mum, there was also the corollary: how dare you and how dare you die of such a stupid man-made disease, something which was so easily avoidable? If only you’d worn gloves and a mask and some protective clothing you would have been OK. None of this would have happened. None of us would have had to be so upset. It was your own fault. They didn’t even claim for compensation.* (#ulink_d02a591b-fffc-5eaf-9d12-43363efbb0fa)

And now Bob’s mother Maureen has Alzheimer’s. Bob can’t believe it. Sometimes he’ll shout and rage at her, when no one else is there: he can’t believe she’s really ill. A part of him thinks she’s putting it on. Silly woman, he calls her. Silly bitch. Stupid cow. Challenging her. Words he remembers saying to her only once before, when he was a child, after they’d had some argument or other and his mother had said to him, ‘You’re not too old for me to give you a good hiding, you know,’ and he smirked at her and so she did, she smacked him, right across the backside, and he felt the full force of her wedding ring and he never said the words again. Until now. When Maureen deteriorated one of the nurses recommended a book to Bob, to help him cope, but Bob doesn’t read books. He does not admire book learning: what Bob admires is expertise. So he buys in twenty-four-hour care. It’s the least he can do.

At night when he gets home from work, he lets the nurse take a few hours to herself, and he sits down with his mother in front of the wide-screen TV, in his TV room. He’s had the place fitted out with a DVD player and a complete home cinema system – which he’d had to order specially from America. He’d gone to considerable trouble, had got in Harry Lamb the Odd Job Man to help him fix the screen to the joists in the ceiling – but he didn’t enjoy watching the home cinema with his mother. It didn’t feel natural. He only watched it now with the waitresses. With his mum he preferred to watch TV, like they used to when Bob was a child. They watch anything, Bob and his mum. Films. Football. News. Documentaries. It doesn’t matter. It’s all the same. It’s not the content. It’s the act of watching that counts. It is a huge comfort to them both.

Before they go to bed at night, during the adverts, Bob always makes them something to eat. He tends to get hungry around about ten, the same every night, before the news, but it always seems to surprise him, his own hunger. He never seems prepared for it. Sometimes he roams around the kitchen in the semi-darkness, opening cupboards, ransacking for food. Bob is a rich man, but he can find no food in his own house which he would want to eat. What he could really manage would be one of his mum’s roast dinners. He could eat a tray of those roast potatoes. A whole tray. They were always so good. The beef dripping – that was the secret. He knows how to do it, of course – you have to get the beef dripping nice and hot in â saucepan, and then you bash the parboiled potatoes around in there for a bit, and season them with salt and pepper, and then slide them on the tray into the oven, and one hour later, perfect roast potatoes. But he could never be bothered to do it himself. It just wouldn’t be the same.

The rare roast beef, though. He could definitely eat some of his mum’s rare roast beef. And maybe some carrots. And a nice gravy.* (#ulink_7197d14c-3840-5e31-9b58-9f3150a2198b)

He goes from cupboard to cupboard – chocolates, biscuits, crisps, nuts, crackers. None of it is any good. It’s all manufactured. It’s all rubbish. He knows it’s rubbish. Sometimes the rubbish in his cupboards makes him so angry that he throws it all away, just chucks it in the bin. And then he buys more. He buys more rubbish. This is what happens when you’re a rich man in our town. You don’t necessarily buy better. You just buy more. Because there isn’t anything else to buy. You want something more fancy, you have to leave: you have to go to London, or somewhere else where they do funny spaghetti and truffle oils, and novelty cheeses.

Bob’s mother used to make lasagne. And she used to make a salmon soufflé, on special occasions, using a whole tin of salmon – that was good too. And sausage rolls. Macaroni cheese. Pies and pastries. And cakes. The smell of baking. The smell of fresh bread. The food then seemed so different. It was all so good. Bob’s favourite meal, of all the meals his mother used to make … after all these years, he still has no doubt what was his favourite, and every night, between the adverts, he ends up trying to re-create it.

When he used to come home from school he would be just so tired sometimes, and he’d be so hungry, before his dad got home from the works, and so he and his mum would sit down together, his mum drinking her coffee with two sugars and smoking, and him eating the sandwich that she’d made him: white bread and margarine and Cheddar cheese, or sometimes a slice of ham, if they had it in the house, which was not often.

‘How was school?’ she’d ask.

‘Fine,’ he’d say. ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’

‘OK,’ she’d say and that would be fine. They didn’t have to talk: they were mother and son.

They would just sit there, the two of them, looking out of the window, eating cheese sandwiches and waiting for his dad to come home.

So when Frank Gilbey rolled up at Bob’s late one night, just before Christmas, Bob ushered him in, asked him to sit down in the big kitchen equipped with every piece of gadgetry imaginable, and about half a mile of granite work surface and a foundry’s worth of stainless steel, put the kettle on and put a simple cheese sandwich down in front of him.

‘So?’ said Bob.

‘There’s a problem,’ said Frank.

* (#ulink_adb81966-4791-5863-b4b6-e4496df21c47) He also has his own website now, and a cookbook, Speedy Bap!, which includes chapters on ‘Home-Made Burgers that Don’t Fall Apart’, ‘What Next with Tuna?’ and an appendix, ‘Mayo or Pickle?’, in which Bob comes down firmly on the side of chutney. The book is available locally from all good bookshops, or newsagents, price £9.99. It’s been a runaway success county-wide. Bob is in demand all over the place for signings and sandwich-making demonstrations. A new updated edition of the book, Speedy Bap!!, which is guaranteed a lot of local press coverage and includes all-new chapters on low-fat cottage cheese and wafer-thin ham, is due out soon, with additional recipes gathered from Bob’s visits to various Women’s Institutes, Soroptomists, the Waterstones up in the city, and other local groups and associations.

* (#ulink_397df15a-dc35-56ec-a366-1606b8394498) Bob’s old friend Terry Wilkinson, ‘Wilkie the Gut’ to many of us here in town – a man who has enjoyed perhaps a touch too much old-fashioned food (cooked the traditional way) in his time – runs a nice little business, The Gist, up on the industrial estate, specialising in vehicle graphics, and he took care of all the graphics on the vans for Bob. Terry left school with no qualifications and few prospects but he now lives in a five-bedroom house with Jacuzzi in the Woodsides development, and frankly a few slips in spelling and the odd wandering apostrophe are hardly going to worry him: as far as Terry is concerned a palette is a palet is a palate; just as long as you get – as Terry himself might say – the gist.

* (#ulink_c4202638-3369-56e2-979c-1631e8d6fc98) Unlike a lot of people here in town. Martin Phillips, the solicitor on Sunnyside Terrace, has dealt with more than his fair share of vibration white finger, and asbestos exposure, and occupational asthma, and allergic rhinitis over the past few years – dealing with wheezy old and middle-aged men who spent their lives working on the roads, or on the sites, or on the railways, or out in the fields, or in the factories and the steelworks up in the city, which covers just about everyone here, actually, and all of whom are now seeking recompense for lives diminished and cut short, recompense which usually covers about two weeks in Florida with the grandchildren, a new sunlounger for the patio and a slightly better coffin. For further details and information on claiming for industrial diseases contact your local Citizens Advice Bureau or ring Industrial Diseases Compensation Ltd on 0800 454532.

* (#ulink_68a05a1f-27f4-50d8-9bdf-d1bb87253321) Bob’s ‘Sunday Roastie Wedgie’ – cold roast beef, horseradish, English mustard and roasted vegetables in a granary bap – includes just about everything but the gravy (see Speedy Bap!, p.44). He did try experimenting with a cold gravy mayonnaise at one time but the combination of beef stock and whisked eggs was too cloying on the palate. It’s a simple lesson, but one worth repeating: gravy is best served hot.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/ian-sansom/ring-road-there-s-no-place-like-home/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Ian Sansom

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A warm, humane, and sharply observed tale of small town life that is by equal turns hilarious and moving.Big Davey Jones is coming home. He′s been gone almost 20 years now, but nobody′s forgotten him. Davey′s a local hero – his miracle birth as the seventh son of a seventh son brought fame to this little town and they′ve been grateful ever since. But Davey′s home town has changed much in the intervening years. The traditional family business like Billy Finlay′s Auto-Supplies and Calton′s Bakery and Tea Rooms have been replaced with ′Exciting New Housing Developments!′ and even a nightclub called ′Paradise Lost′.The locals haven′t changed much though. Bob Savory, who always had it in him, has made a million with his company Sandwich Classics, and he′s branching out now, with an Irish themed restaurant on the ring road. Francie McGinn, the divorced minister at The People′s Fellowship, is still trying to convert the town through his Fish-and-Chip Biblical Quiz Nights and his Good Friday Carvery & Gospel Night. And Sammy, the town′s best plumber, is depressed as ever and looking for solace at the bottom of the whisky bottle.Clever, touching and, above all, utterly spot-on in its depiction of small town life, Ring Road is confirms Ian Sansom’s status as one of our most perceptive authors working today.