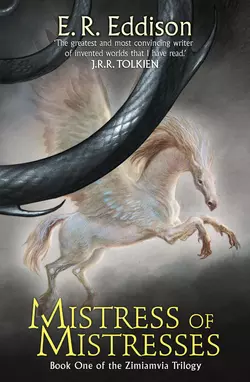

Mistress of Mistresses

E. R. Eddison

Douglas Winter E.

The first volume in the classic epic trilogy of parallel worlds, admired by Tolkien and the great prototype for The Lord of the Rings and modern fantasy fiction.According to legend, the Gates of Zimiamvia lead to a land ‘that no mortal foot may tread, but that souls of the dead that were great upon earth do inhabit.’ Here they forever live, love, do battle, and even die again.Edward Lessingham – artist, poet, king of men and lover of women – is dead. But from Aphrodite herself, the Mistress of Mistresses, he has earned the promise to live again with the gods in Zimiamvia in return for her own perilous future favours.This sequel to The Worm Ouroboros recounts the story of Lessingham’s first day in this strange Valhalla, where a lifetime is a day and where – among enemies, enchantments, guile and triumph – his destiny can be rewritten.

Copyright (#ulink_b88a4b54-86ae-5c3a-9539-74ac526aa527)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © E. R. Eddison 1935

Jacket illustration by John Howe © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2014

E.R. Eddison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578139

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007578146

Version: 2014-09-09

Dedication (#ulink_26046e34-5a37-51a8-bc25-29b00e9560fe)

WINIFRED GRACE EDDISON

To you, madonna mia,

and to my friend

EDWARD ABBE NILES

I dedicate this

Vision of Zimiamvia

Proper Names the reader will no doubt pronounce as he chooses. But perhaps, to please me, he will keep the i’s short in Zimiamvia and accent the third syllable: accent the second syllable in Zayana, give it a broad a (as in ‘Guiana’), and pronouce the ay in the first syllable – and the ai in Laimak – as in ‘aisle’: keep the g soft in Fingiswold: let Memison echo ‘denizen’ except for the m: accent the first syllable in Rerek and make it rhyme with ‘year’: remember that Fiorinda is an Italian name, Amaury, Amalie, and Beroald French, and Antiope, Zenianthe, and a good many others, Greek: last, regard the sz in Meszria as ornamental, and not be deterred from pronouncing it as plain ‘Mezria’.

Mère des souvenirs, maîtresse des maîtresses,

O toi, tous mes plaisrs! ô toi, tous mes devoirs!

Tu te rappelleras la beauté des caresses,

La douceur du foyer et le charme des soirs,

Mère des souvenirs, maîtresse des maîtresses!

Les soirs illuminés par l’ardeur du charbon,

Et les soirs au balcon, voilés de vapeurs roses.

Que ton sein m’était doux! que ton cœur m’était bon!

Nous avons dit souvent d’impérissables choses

Les soirs illuminés par l’ardeur du charbon.

Que les soleils sont beaux dans les chaudes soirées!

Que l’espace est profond! que le cœur est puissant!

En me penchant vers toi, reine des adorées,

Je croyais respirer le parfum de ton sang.

Que les soleils sont beaux dans les chaudes soirées!

La nuit s’épaississait ainsi qu’une cloison,

Et mes yeux dans le noir devinaient tes prunelles,

Et je buvais ton souffle, ô douceur, ô poison!

Et tes pieds s’endormaient dans mes mains fraternelles.

La nuit s’épaississait ainsi qu’une cloison.

Je sais l’art d’évoquer les minutes heureuses,

Et revis mon passé blotti dans tes genoux.

Car à quoi bon chercher tes beautés langoureuses

Ailleurs qu’en ton cher corps et qu’en ton cœur si doux?

Je sais l’art d’évoquer les minutes heureuses!

Ces serments, ces parfums, ces baisers infinis,

Renaîtront-ils d’un gouffre interdit à nos sondes,

Comme montent au ciel les soleils rajeunis

Après s’être lavés au fond des mers profondes?

– O serments! ô parfums! ô baisers infinis!

BAUDELAIRE

CONTENTS

Cover (#u7f85330d-504b-5c7e-a19b-b2f1bcc9278f)

Title Page (#u0b89d958-41b7-5a95-926a-955803faaf27)

Copyright (#ue27ce6ff-f2a2-568a-9ccd-3ac5f89dc500)

Dedication (#u98f4454c-e70e-5685-abcf-b71549def8fe)

Epigraph (#ubf7e0827-c7a0-5aa5-bad0-0ad284608f09)

Foreword by Douglas E. Winter (#u534f6659-7ff5-5901-a67c-7507d117ec20)

THE OVERTURE (#u093b4160-de38-555a-843d-c0842f7bba73)

ZIMIAMVIA (#ufe7e13be-0693-5186-a6c3-fe72e3366cf7)

I. A Spring Night in Mornagay (#ub0296704-92b4-5676-adde-034a9d0b64b2)

II. The Duke of Zayana (#ufee142db-bd1d-514a-b488-8ede7c4a65b5)

III. The Tables Set in Meszria (#ube1db29e-822d-5428-a8a0-d9b4cdd89396)

IV. Zimiamvian Dawn (#u05862199-1ef0-5e12-99b6-9b470d37f03b)

V. The Vicar of Rerek (#u1df5d449-0f73-55ee-b546-3905a3e0cc39)

VI. Lord Lessingham’s Embassage (#ua3942d33-0645-52e6-9f07-5a0e3c506636)

VII. A Night-Piece on Ambremerine (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII. Sferra Cavallo (#litres_trial_promo)

IX. The Ings of Lorkan (#litres_trial_promo)

X. The Concordat of Ilkis (#litres_trial_promo)

XI. Gabriel Flores (#litres_trial_promo)

XII. Noble Kinsmen in Laimak (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII. Queen Antiope (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV. Dorian Mode: Full Close (#litres_trial_promo)

XV. Rialmar Vindemiatrix (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI. The Vicar and Barganax (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII. The Ride to Kutarmish (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII. Rialmar in Starlight (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX. Lightning Out of Fingiswold (#litres_trial_promo)

XX. Thunder Over Rerek (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI. Enn Freki Renna (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII. Zimiamvian Night (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

DRAMATIS PERSONAE (#litres_trial_promo)

MAPS OF THE THREE KINGDOMS (#litres_trial_promo)

ALSO BY E. R. EDDISON (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_90051bfd-a1c9-5dba-980c-178b0f84b889)

BY DOUGLAS E. WINTER (#ulink_90051bfd-a1c9-5dba-980c-178b0f84b889)

‘Is this the dream? or was that?’

WORDS create worlds: storytelling is a kind of godhood, taking the imperfect day of language, moulding it in the writer’s own image and, with skill, breathing it to life. The task is a formidable one, and it is little wonder that most fiction is content with reinventing reality, safely sculpting what is known. And why not? Stories are for the most part entertainment, ephemeral, meant only for the moment. Few novels strive for life beyond their covers; few hold us in their dominion for years, fewer still for lifetimes. The words and the worlds of E. R. Eddison, which I first discovered more than twenty years ago, still intrigue me, uplift me, haunt me, today. I know that I am not alone.

Eric Rücker Eddison (1882–1945) was a civil servant at the British Board of Trade, sometime Icelandic scholar, devotee of Homer and Sappho, and mountaineer. Although by all accounts a bowler-hatted and proper English gentleman, Eddison was an unmitigated dreamer who, in occasional spare hours over some thirty years, put his dreams to paper. In 1922, just before his fortieth birthday, a small collector’s edition of The Worm Ouroboros was published; larger printings soon followed in both England and America, and a legend of sorts was born. The book was a dark and blood-red jewel of wonder, equal parts spectacle and fantasia, labyrinthine in its intrigue, outlandish in its violence. It was also Eddison’s first novel.

After writing an adventure set in the Viking age, Styrbiorn the Strong (1926), and a translation of Egil’s Saga (1930), Eddison devoted the remainder of his life to the fantastique in a series of novels set, for the most part, in Zimiamvia, the fabled paradise of The Worm Ouroboros. The Zimiamvian books were, in Eddison’s words, ‘written backwards’, and thus published in reverse chronological order of events: Mistress of Mistresses (1935), A Fish Dinner in Memison (1941), and The Mezentian Gate (1958). (The final book was incomplete when Eddison died, but his notes were so thorough that his brother, Colin Eddison, and his friend George R. Hamilton were able to assemble the book for publication.) Although the books are known today as a trilogy, Eddison wrote them as an open-ended series; they may be read and enjoyed alone or in any sequence. Each is a metaphysical adventure, an intricate Chinese puzzle box whose twists and turns reveal ever-encircling vistas of delight and dread.

Eddison’s four great fantasies are linked by the enigmatic character of Edward Lessingham – country gentleman, soldier, statesman, artist, writer, and lover, among other talents – and his Munchausen-like adventures in space … and time. Although he disappears after the early pages of The Worm Ouroboros, Lessingham is central to the books that follow. ‘God knows,’ he tells us, ‘I have dreamed and waked and dreamed till I know not well which is dream and which is true.’ One of the pleasures of reading Eddison is that we, too, are never certain. Perhaps Lessingham is a man of our world; perhaps he is a god; perhaps he is only a dream … or a dream within a dream. And perhaps, just perhaps, he is all of these things, and more.

In a transcendent moment of The Worm Ouroboros, the Demonlords Juss and Brandoch Daha, searching desperately for their lost comrade-in-arms, Goldry Bluzco, ascend to the dizzying heights of Koshtra Pivrarcha. There, in the distance, they see paradise. Lord Juss speaks:

‘Thou and I, first of the children of men, now behold with living eyes the fabled land of Zimiamvia. Is that true, thinkest thou, which philosophers tell of that fortunate land: that no mortal foot may tread it, but the blessed souls do inhabit it of the dead that be departed, even they that were great upon earth and did great deeds when they were living, that scorned not earth and the delights and the glories thereof, and yet did justly and were not dastards nor yet oppressors?’

‘Who knoweth?’ answers Brandoch Daha. ‘Who shall say he knoweth?’

If anyone knows, it is Edward Lessingham. In the Overture to Mistress of Mistresses, we learn that old age has claimed him, his final hours watched over by a mysterious lover. Lord Juss’s question is repeated, and the reader – like Lessingham – is taken straightaway to Zimiamvia. This is neither the biblical paradise, nor that of classical mythology, but a mad poet’s dream of Northern Europe during the Renaissance. Zimiamvia is an imperfect heaven – what other kind could exist without boredom for its residents? – a Machiavellian playground for men and gods, where mystery and menace, romance and revenge, swordplay and soldiering are the natural order of things.

Three kingdoms comprise this otherworld – known, from north to south, as Fingiswold, Rerek and Meszria – and all are ruled by the wise, firm hand of King Mezentius. In Zimiamvia, Lessingham lives on, his earthly self a duality. His namesake, Lord of Rerek, is his Apollonian half – the embodiment of reason, logic, science. Lord Lessingham is cut from the same cloth as the Demon heroes of The Worm Ouroboros, a demigod and bravo, a man of action and of honour with but a single stain: kinship, and thus loyalty in blood, to Horius Parry, the ambitious Vicar in Rerek. Parry, in turn, is the scheming serpent of this enigmatic Eden, a villain extraordinaire whose instinct for treachery and terror – and for surviving to scheme again another day – is worthy of the most diabolical of devils.

Lessingham’s Dionysian qualities – magic, art, and madness – are found in Duke Barganax, bastard son of King Mezentius and his mistress Amalie, the Duchess of Memison. Barganax takes counsel in the aged yet ageless Doctor Vandermast, a mysterious Merlin who is given to spouting Spinoza and minding his lovely shapeshifting nymphs, Anthea and Campaspe. ‘My study,’ says Vandermast [in A Fish Dinner in Memison], ‘is now of the darkness rather which is hid in the secret heart of man: my office but only to understand, and to watch, and to wait.’

With the deaths of King Mezentius and his only legitimate son, Styllis – in which Parry’s perpetually bloody hand is suspect – the crown descends to the beautiful and doomed Queen Antiope, with whom, inevitably, Lord Lessingham will fall in love. The struggle for power, by wile and war and witchery, enwraps Zimiamvia in a web of passion and violence that is tangled by strange shifts of time.

‘Time,’ Eddison tells us, ‘is a curious business’, and in Zimiamvia it grows more and more curious. ‘Is this the dream?’ his characters ask, ‘or was that?’ [A Fish Dinner in Memison]. These tales are not simply written backwards, they defy most novelistic notions of time. Eddison was exceptional in his embrace of the fantastique;in his fiction there are no logical imperatives, no concessions to cause and effect, only the elegant truths of the higher calling of myth. Characters traverse distances and decades in the blink of an eye; worlds take shape, spawn life, evolve through billions of years and are destroyed, all during a dinner of fish. These are dreams made flesh by a dreamer extraordinaire.

Ten years: ten million years: ten minutes. One and the same, says Eddison, and in Zimiamvia we journey beyond the pure heroic adventure of The Worm Ouroboros into an existential-romantic quest, a speculation on the nature of woman and man, Goddess and God, reality and dream: ‘It was in that moment as if he looked through layer upon layer of dream, as though veil behind veil: the thinnest veil, natural present: the next, as if a dumb-show strangely presented by art magic’ [Mistress of Mistresses]. Eddison’s characters exist beyond time, beyond dimension, woven into a tapestry that circles and circles on itself, as abiding and eternal as its central image: the worm Ouroboros, that eateth its own tail.

‘If we were Gods, able to make worlds and unmake ’em as we list, what world would we have?’ [A Fish Dinner in Memison]. Here is the central dilemma of Zimiamvia:the nature and means of creation. Worlds within worlds, stories within stories, characters within characters, phantasms within phantasms – this is a majestic maze of mythmaking, a fiction that questions all assumptions of reality. Eddison thus proves more than a dreamer; like the very best writers of the fantastique, he saw this fiction of (im)possibilities as the truest mirror of our lives, one that shines back brightly the depths of the human spirit as well as the surfaces of the flesh.

Eddison’s prose is archaic and often difficult, an intentionally affected throwback to Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. His characters are thus eloquent but long-winded; they speak not of killing a man, but of ‘sending him from the shade into the house of darkness’ [The Worm Ouroboros]. In his finest moments, Eddison ascends to a sustained poetic beauty; listen, for example, to the haunting premonition of the renegade Goblin Gro:

‘For as I lay sleeping betwixt the strokes of night, a dream of the night stood by my bed and beheld me with a glance so fell that I was all adrad and quaking with fear. And it seemed to me that the dream smote the roof above my bed, and the roof opened and disclosed the outer dark, and in the dark travelled a bearded star, and the night was quick with fiery signs. And blood was on the roof, and great gouts of blood on the walls and on the cornice of my bed. And the dream screeched like the screech-owl, and cried, Witchland from thy hand, O King!’ [The Worm Ouroboros]

At other times the reader is virtually overwhelmed with words. Palaces and armoury were Eddison’s particular vices; he describes them with such ornate grandeur that page after page is lavished with their decoration. The reader should not be deterred by the density of such passages; like a vintage wine, a taste for Eddison’s prose is expensively acquired, demanding the reader’s patience and perseverance – and it is worthy of its price. These are books to be savoured, best read in the long dark hours of night, when the wind is against the windows and the shadows begin to walk – books not meant for the moment, but for forever.

The Zimiamvian trilogy inevitably has been compared with J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, but apart from their narrative ambition and epic sweep, the books share little in common. (Eddison, like Tolkien, disclaimed the notion that he was writing something beyond mere story: ‘It is neither allegory nor fable but a Story to be read for its own sake’ [The Worm Ouroboros’preface]. But as the reader will no doubt observe, he proves much less convincing.)

If comparisons are in order, then I suggest Eddison’s obvious influences – Homer and the Icelandic sagas – and that most controversial of Jacobean dramatists, John Webster, whose blood-spattered tales of violence and chaos (from which Eddison’s characters quote freely) saw him chastised for subverting orthodox society and religion. The shadow of Eddison may be seen, in turn, not only in the modern fiction of heroic fantasy, but also in the writings of his truest descendants, such dreamers of the dark fantastique as Stephen King (whose own epics, The Stand and The Dark Tower, read like paeans to Eddison) and Clive Barker (whose The Great and Secret Show called its chaotic forces the Iad Ouroboros).

Eddison would have found this line of succession, like the cyclical popularity of his books, the most natural order of events: the circle, ever turning – like the worm Ouroboros, that eateth its own tail – the symbol of eternity, where ‘the end is ever at the beginning and the beginning at the end for ever more’.

Welcome to that fabled paradise, Zimiamvia: Once you have entered these words, this world, you may never leave.

DOUGLAS E. WINTER

1991

in memory of Phil Grossfield

THE OVERTURE (#ulink_c7f1b389-01e9-5ca7-9b31-5ca3a17310ae)

THE UNSETTING SUNSET • AN UNKNOWN LADY BESIDE THE BIER • EASTER AT MARDALE GREEN • LESSINGHAM • LADY MARY LESSINGHAM • MEDITATION OF MORTALITY • APHRODITE OURANIA • A VISION OF ZIMIAMVIA • A PROMISE.

LET me gather my thoughts a little, sitting here alone with you for the last time, in this high western window of your castle that you built so many years ago, to overhang like a sea eagle’s eyrie the grey-walled waters of your Raftsund. We are fortunate, that this should have come about in the season of high summer, rather than on some troll-ridden night in the Arctic winter. At least, I am fortunate. For there is peace in these Arctic July nights, where the long sunset scarcely stoops beneath the horizon to kiss awake the long dawn. And on me, sitting in the deep embrasure upon your cushions of cloth of gold and your rugs of Samarkand that break the chill of the granite, something sheds peace, as those great sulphur-coloured lilies in your Ming vase shed their scent on the air. Peace; and power; indoors and out: the peace of the glassy surface of the sound with its strange midnight glory as of pale molten latoun or orichalc; and the peace of the waning moon unnaturally risen, large and pink-coloured, in the midst of the confused region betwixt sunset and sunrise, above the low slate-hued cloud-bank that fills the narrows far up the sound a little east of north, where the Trangstrómmen runs deep and still between mountain and shadowing mountain. That for power: and the Troldtinder, rearing their bare cliffs sheer from the further brink; and, away to the left of them, like pictures I have seen of your Ushba in the Caucasus, the tremendous two-eared Rulten, lifted up against the afterglow above a score of lesser spires and bastions: Rulten, that kept you and me hard at work for nineteen hours, climbing his paltry three thousand feet. Lord! And that was twenty-five years ago, when you were about the age I am today, an old man, by common reckoning; yet it taxed not me only in my prime but your own Swiss guides, to keep pace with you. The mountains; the unplumbed deeps of the Raftsund and its swinging tideways; the unearthly darkless Arctic summer night; and indoors, under the mingling of natural and artificial lights, of sunset and the windy candlelight of your seven-branched candlesticks of gold, the peace and the power of your face.

Your great Italian clock measures the silence with its ticking: ‘Another, gone! Another, gone! Another, gone!’

Commonly, I have grown to hate such tickings, hideous to an old man as the grinning memento mori at the feast. But now (perhaps the shock has deadened my feelings), I could almost cheat reason to believe there was in very truth eternity in these things: substance and everlasting life in what is more transient and unsubstantial than a mayfly, empirical, vainer than air, weak bubbles on the flux. You and your lordship here, I mean, and this castle of yours, more fantastic than Beckford’s Fonthill, and all your life that has vanished into the irrevocable past: a kind of nothingness. ‘Another, gone! Another, gone!’ Seconds, or years, or aeons of unnumbered time, what does it matter? I can well think that this hour just past of my sitting here in this silent room is as long a time, or as short, as those twenty-five years that have gone by since you and I first, on a night like this, stared at Lofotveggen across thirty miles of sea, as we rounded the Landegode and steered north into the open Westfirth.

I can see you now, if I shut my eyes; in memory I see you, staring at the Lynxfoot Wall: your kingdom to be, as I very well know you then resolved (and soon performed your resolve): that hundred miles of ridge and peak and precipice, of mountains of Alpine stature and seeming, but sunk to the neck in the Atlantic stream and so turned to islands of an unwonted fierceness, close set, so that seen from afar no breach appears nor sea-way betwixt them. So sharp cut was their outline that night, and so unimaginably nicked and jagged, against the rosy radiance to the north which was sunset and sunrise in one, that for the moment they seemed feigned mountains cut out of smoky crystal and set up against a painted sky. For a moment only; for there was the talking of the waves under our bows, and the wind in our faces, and, as time went by with still that unaltering scene before us, every now and again the flight and wild cry of a black-backed gull, to remind us that this was salt sea and open air and land ahead. And yet it was hard then to conceive that here was real land, with the common things of life and houses of men, under that bower of light where the mutations of night and day seemed to have been miraculously slowed down; as if nature had fallen entranced with her own beauty mirrored in that sheen of primrose light. Vividly, as it had been but a minute since instead of a quarter of a century, I see you standing beside me at the taffrail, with that light upon your lean and weather-beaten face, staring north with a proud, alert, and piercing look, the whole frame and posture of you alive with action and resolution and command. And I can hear the very accent of your voice in the only two things you said in all that four hours’ crossing: first, ‘The sea-board of Demonland.’ Then, an hour later, I should think, very low and dream-like, ‘This is the first sip of Eternity.’

Your voice, that all these years, forty-eight years and a month or two, since first I knew you, has had power over me as has no other thing on earth, I think. And today – But why talk of today? Either today is not, or you are not: I am not very certain which. Yesterday certainly was yours, and those five and twenty years in which you, by your genius and your riches, made of these islands a brighter Hellas. But today: it is as well, perhaps, that you have nothing to do with today. The fourteenth of July tomorrow: the date when the ultimatum expires, which this new government at Oslo sent you; the date they mean to take back their sovereign rights over Lofoten in order to reintroduce modern methods into the fisheries. I know you were prepared to use force. It may come to that yet, for your subjects who have grown up in the islands under the conditions you made for them may not give up all without a stroke. But it could only have been a catastrophe. You had not the means here to do as you did thirty-five years ago, when you conquered Paraguay: you could never have held, with your few thousand men, this bunch of islands against an industrialized country like Norway. Stir’s, ‘Shall the earth-lice be my bane, the sons of Grim Kogur?’ They would have bombed your castle from the air.

And so, I think fate has been good to you. I am glad you died this morning.

I must have been deep in my thoughts and memories when the Señorita came into the room, for I had heard no rustle or footfall. Now, however, I turned from my window-gazing to look again on the face of Lessingham where he lay in state, and I saw that she was standing there at his feet, looking where I looked, very quiet and still. She had not noticed me, or, if she had, made no account of my presence. My nerves must have been shaken by the events of the day more than I could before have believed possible: in no other way can I explain the trembling that came upon me as I watched her, and the sudden tears that half blinded my eyes. For though, no doubt, the feelings can play strange tricks in moments of crisis, and easily confound that nice order which breeding and the common proprieties impose even on our inward thoughts, it is yet notable that the perturbation that now swept my whole mind and body was without any single note or touch of those chords which can thrill so loudly at the approach of a woman of exquisite beauty and presumed accessibility. Tears of my own I had not experienced since my nursery days. Indeed, it is only by going back to nursery days that I can recall anything remotely comparable to the emotion with which I was at that moment rapt and held. And both then as a child, and now half-way down the sixties: then, as I listened on a summer’s evening in the drawing-room to my eldest sister singing at the piano what I learned to know later as Schubert’s Wohin?, and now, as I saw the Señorita Aspasia del Rio Amargo stand over my friend’s death-bed, there was neither fear in the trembling that seized me and made my body all gooseflesh, nor was it tears of grief that started in my eyes. A moment before, it is true, my mind had been feeling its way through many darknesses, while the heaviness of a great unhappiness at long friendship gone like a blown-out candleflame clogged my thoughts. But now I was as if caught by the throat and held in a state of intense awareness: a state of mind that I can find no name for, unless to call it a state of complete purity, as of awaking suddenly in the morning of time and beholding the world new born.

For a good many minutes, I think, I remained perfectly still, except for my quickened breathing and the shifting of my eyes from this part to that of the picture that was burning itself into my senses so that, I am very certain, all memories and images will fall off from me before this will suffer alteration or grow dim. Then, unsurprised as one hears in a dream, I heard a voice (that was my own voice) repeating softly that stanza in Swinburne’s great lamentable Ballad of Death (#litres_trial_promo):

By night there stood over against my bed

Queen Venus with a hood striped gold and black,

Both sides drawn fully back

From brows wherein the sad blood failed of red,

And temples drained of purple and full of death.

Her curled hair had the wave of sea-water

And the sea’s gold in it.

Her eyes were as a dove’s that sickeneth.

Strewn dust of gold she had shed over her,

And pearl and purple and amber on her feet.

With the last cadence I was startled awake to common things, as often, startling out of sleep, you hear words spoken in a dream echo loud beyond nature in your ears. I rose, inwardly angry with myself, with some conventional apology on the tip of my tongue, but I bit it back in time. The verses had been spoken not with my tongue but in my brain, I thought; for the look on her face assured me that she had heard nothing, or, if she had, passed it by as some remark which demanded neither comment on her part nor any explanation or apology on mine.

She moved a little so as to face me, her left hand hanging quiet and graceful at her side, her right resting gently on the brow of the great golden hippogriff that made the near bedpost at the foot of Lessingham’s bed. With the motion I seemed to be held once again in that contemplation of peace and power from which I had these hours past taken some comfort, and at the same time to be rapt again into that state of wide-eyed awareness in which I had a few minutes since gazed upon her and Lessingham. But now, just as (they tell us) a star of earthly density but of the size of Betelgeuze would of necessity draw to it not matter and star-dust only but the very rays of imponderable light, and suck in and swallow at last the very boundaries of space into itself, so all things condensed in her as to a point. And when she spoke, I had an odd feeling as if peace itself had spoken.

She said: ‘Is there anything new you can tell me about death, sir? Lessingham told me you are a philosopher.’

‘All I could tell you is new, Doña Aspasia,’ I answered; ‘for death is like birth: it is new every time.’

‘Does it matter, do you suppose?’ Her voice, low, smooth, luxurious (as in Spanish women it should be, to fit their beauty, yet rarely is), seemed to balance on the air like a soaring bird that tilts an almost motionless wing now this way now that, and so soars on.

‘It matters to me,’ I said. ‘And I suppose to you.’

She said a strange thing: ‘Not to me. I have no self.’ Then, ‘You,’ she said, ‘are not one of those quibbling cheap-jacks, I think, who hold out to poor mankind hopes of some metaphysical perduration (great Caesar used to stop a bung-hole) in exchange for that immortality of persons which you have whittled away to the barest improbability?’

‘No,’ answered I. ‘Because there is no wine, it is better go thirsty than lap sea-water.’

‘And the wine is past praying for? You are sure?’

‘We are sure of nothing. Every path in the maze brings you back at last to Herakleitos if you follow it fairly; yes, and beyond him: back to that philosopher who rebuked him for saying that no man may bathe twice in the same river, objecting that it was too gross an assumption to imply that he might avail to bathe once.’

‘Then what is this new thing you are to tell me?’

‘This,’ said I: ‘that I have lost a man who for forty years was my friend, and a man great and peerless in his generation. And that is death beyond common deaths.’

‘Then I see that in one river you have bathed not twice but many times,’ she said. ‘But I very well know that that is no answer.’

She fell silent, looking me steadfastly in the eye. Her eyes with their great black lashes were unlike any eyes that I have ever seen, and went strangely with her dark southern colouring and her jet-black hair: they were green, with enormous pupils, and full of fiery specks, and as the pupils dilated or narrowed the whole orbs seemed aglow with a lambent flame. Frightening eyes at the first unearthly glance of them: so much so, that I thought for an instant of old wild tales of lamias and vampires, and so of that loveliest of all love-stories and sweet ironic gospel of pagan love – Théophile Gautier’s: of her on whose unhallowed gravestone was written:

Ici gît Clarimonde (#litres_trial_promo),

Qui jut de son vivant

La plus belle du monde.

And then in an instant my leaping thoughts were stilled, and in awed wonderment I recognized, deep down in those strange burning eyes, sixty years in the past, my mother’s very look as she (beautiful then, but now many years dead) bent down to kiss her child good night.

The clock chiming the half hour before midnight brought back time again. She on the chime passed by me, as in a dream, and took my place in the embrasure; so that sitting at her feet I saw her side-face silhouetted against the twilight window, where the darkest hour still put on but such semblance of the true cloak of night as the dewdrops on a red rose might wear beside true tears of sorrow, or the faint memory of a long forgotten grief beside the bitterness of the passion itself. Peace distilled upon my mind like perfume from a flower. I looked across to Lessingham’s face with its Grecian profile, pallid under the flickering candles, facing upwards: the hair, short, wavy, and thick, like a Greek God’s: the ambrosial darknesses of his great black beard. He was ninety years old this year, and his hair was as black and (till a few hours ago, when he leaned back in his chair and was suddenly dead) his voice as resonant and his eyes as bright as a man’s in his prime age.

The silence opened like a lily, and the Señorita’s words came like the lily’s fragrance: ‘Tell me something that you remember. It is good to keep memories green.’

‘I remember,’ answered I, ‘that he and I first met by candlelight. And that was forty-eight years ago. A good light to meet by; and a good light for parting.’

‘Tell me,’ she said.

‘It was Easter time at Mardale Green in Cumberland. I had just left school. I was spending the holidays with an aunt of mine who had a big house in the Eamont valley. On Easter Sunday after a hard day by myself on the fells, I found myself looking down on Mardale and Haweswater from the top of Kidsty Pike. It was late afternoon, and the nights still closed in early. There was leavings of snow on the tops. Beneath my feet the valley was obscure purple, the shadows of night boiling up from below while weak daylight still walked the upper air and the mountain ridges. I ran down the long spur that Kidsty Pike sends down eastwards, dividing Randale from Riggindale. I was out of breath, and half deaf too after the quick descent, for I had come down about fifteen hundred feet, I suppose, in twelve minutes by the time I came to cross the beck by the farmhouse at Riggindale. Then I saw the light in the church windows through the trees. I remembered that Haweswater and all its belongings were condemned to be drowned twenty feet deep in water in order that some hive of civilization might be washed, and I thought I would go in to evening service in that little church now while I might, before there were fishes in its yew-trees instead of owls. So I stumbled my way from the gathering dusk of the quiet lane through the darkness of those tremendous yews, and so by the curtained doorway under the square tower into that tiny church. I loved it at first sight, coming in from the cold and darkness outside: a place of warmth and gentle candles, with its pews of oak blackened with age, its little Jacobaean gallery, its rough whitewashed walls, simple pointed windows, low dark roof-beams: a glamorous and dazzling loveliness such as a child’s eyes feed upon in its first Christmas tree. As I found my way to a seat half-way up the aisle on the north side, I remember thinking of those little earthenware houses, white, green, and pink, that you can put a night-light inside; things I had forgotten for years, but I had one (as I remembered) long ago, in those lavender and musk-smelling days of childhood, which seemed far more distant to me then, when I was nineteen, than they do now; German things, I fancy: born of the old good German spirit of Struwwelpeter and Christmas trees. Yes, it was those little earthenware houses that I thought of as I sat there, sensuously loving the candlelight and the moving shadows it threw: safe shadows, like those there used to be in the nursery when your nurse was still there; not the ghostly shadows that threatened and hovered when she had gone down to supper and you were left alone. And these shadows and the yellow glamour of the candles fell on kind safe faces, like hers: an old farmer with furrowed, strong, big-boned, storm-weathered features, not in his Sunday-go-to-meeting suit, but with heavy boots nailed and plastered with mud, as if he had walked a good distance to church, and rough strong tweed coat and breeches. Three or four farmers, a few farm men, a few women and girls, an old woman, a boy or two, one or two folk in the little gallery above the door: that was all the congregation. But what pleased me most of all was the old parson, and his way of conducting the service. He was white-haired, with a bristly moustache. He did everything himself single-handed: said the prayers, read the lessons, collected the offertory, played the harmonium that did duty for an organ, preached the sermon. And all these things he did methodically and without hurry or self-consciousness, as you might imagine him looking after a roomful of friends at supper in the little rectory across the road. His sermon was short and full of personalities, but all kindly and gentle-humoured. His announcements of times of services, appointments for weddings, christenings and what not, were interspersed with detailed and homely explanations, given not in the least ex cathedra but as if across the breakfast-table. One particularly I remember, when he gave out: “Hymn number one hundred and forty: the one hundred and fortieth hymn: Jesus lives! No longer now Can thy terrors, death, appal us.” Then, before sitting down to the harmonium, he looked very benevolently at his little flock over the tops of his spectacles, and said, “I want everybody to try and get the words right. Some people make a mistake about the first line of this hymn, and give it quite a wrong meaning. Remember to pause after ‘lives’: ‘Jesus lives!’ Don’t do like some people do, and say ‘Jesus lives no longer now’: that is quite wrong: gives quite a wrong meaning: it makes nonsense. Now then: ‘Jesus lives! No longer now’;” and he sat down to the harmonium and began.

‘It was just at that moment, as we all stood up to sing that innocent hymn with its difficult first line, that I first saw Lessingham. He was away to my right, at the back on the south side, and as the congregation rose I looked half round and saw him. I remember, years later, his describing to me the effect of the sudden view you get of Nanga Parbat from one of those Kashmir valleys; you have been riding for hours among quiet richly wooded scenery, winding up along the side of some kind of gorge, with nothing very big to look at, just lush, leafy, pussy-cat country of steep hillsides and waterfalls; then suddenly you come round a corner where the view opens up the valley, and you are almost struck senseless by the blinding splendour of that vast face of ice-hung precipices and soaring ridges, sixteen thousand feet from top to toe, filling a whole quarter of the heavens at a distance of, I suppose, only a dozen miles. And now, whenever I call to mind my first sight of Lessingham in that little daleside church so many years ago, I think of Nanga Parbat. He stood half a head taller than the tallest man there, but it was the grandeur of his bearing that held me, as if he had been some great lord of the renaissance: a grandeur which seemed to sit upon every limb and feature of him with as much fitness, and to be carried with as little regard or notice from himself, as the scrubby old Norfolk jacket and breeches in which he was dressed. His jacket was threadbare, frayed at the cuffs, strapped with leather at the elbows, but it was as if lighted from within, as the flame shows in a horn lantern, with a sense of those sculptured heroes from the Parthenon. I saw the beauty of his hand where it rested on the window-sill, and the ruby burning like a coal in the strange ring he wore on the middle finger. But just as, in a snow mountain, all sublimities soar upwards to the great peak in the empyrean, so in him was all this majesty and beauty and strength gathered at last in the head and face; that serene forehead, those features where Apollo and Ares seemed to mingle, the strong luxurious lines of the mouth showing between the upcurled moustache and the cataract of black beard: that mouth whose corners seemed the lurking-places of all wild sudden gleams, of delightful humour, and melancholy, and swift resolution, and terrible anger. At length his unconscious eyes met mine, and, looking through me as lost in a deep sadness, made me turn away in some confusion.

‘I thought he had been quite unaware of me and my staring; but as we came out into the lane when church was over (it was starlight now, and the moon risen behind the hills) he overtook me and fell into step beside me, saying he noticed that we wore the same tie. I hardly know which was to me the more astonishing, that this man should deign to talk to me at all, or that I should find myself within five minutes swinging along beside him down the lake road, which was my way home, and talking as easily as if it had been to an intimate friend of my own age instead of a man old enough to be my father: a man too who, to all outward seeming, would have been more in his element in the company of Cesare Borgia or Gonsalvo di Cordova. It was not, of course, till some time after this that I knew he traced his descent through many generations of English forefathers to King Eric Bloodaxe in York, the son of Harald Hairfair, that Charlemagne of the north, and, by the female line, from the greatest ruler of men that appeared in Europe in the thousand years between Charlemagne and Napoleon: the Emperor Frederick II, of whom it has been written that “the power, which in the rout of able and illustrious men shines through crannies, in him pours out as through a rift in nature”. In after years I helped Lessingham a good deal in collecting material for his ten-volume History of Frederick II, which is of course today the standard authority on that period, and ranks, as literature, far and away above any other history book since Gibbon.

‘We talked at first about Eton; then about rowing, and riding, and then about mountains, for I was at that time newly bitten with the climbing-madness and I found him an old hand at the game, though it was not for a year or so that I discovered that he was among the best (though incomparably the rashest) of contemporary climbers. I do not think we touched on the then recent War, in which he attained great distinction, mainly in East Africa. At length the wings of our talk began to take those wider sweeps which starlight and steady walking and that aptness of mind to mind which is the basis of all true friendship lead to; so that after a while I found myself telling him how much his presence had surprised me in that little church, and actually asking him whether he was there to pray, like the other people, or only to look on, like me. Those were the salad-days of my irreligious fervour, when the strange amor mortis of adolescence binds a panache of glory on the helmet of every unbelief, and when books like La Révolte des Anges or Swinburne’s Dolores send a thrill down the spine that can never be caught again in its pristine vigour when years and wisdom have taught us the true terrors of that drab, comfortless, and inglorious sinking into not-being which awaits us all at last. He answered he was there to pray. This I had not expected, though I had been puzzled at the expression on his face in church: an expression that I thought sat oddly on the face of a pagan God or an atheistical tyrant of the renaissance. I mumbled some awkwardness about his not looking to me much like a churchman. His laughter at this seemed to set the whole night a-sparkle: he stopped, caught me by the shoulder with one hand and spun me round to face him. His mouth was smiling down at me in the moonlight in a way which made me think of Pater’s essay about Mona Lisa. He said nothing, but I felt as if I and my half-fledged impieties shrank under that smile to something very naked and nerveless: a very immature Kapaneus posturing before Thebes; a ridiculous little Aias waving a toy sword against the lightning. We walked on beside the dark lake. He said nothing, neither did I. So completely had he already bound me to his chariot-wheels that I was ready, if he had informed me that he was Anabaptist or Turk, to embrace that sect. At length he spoke, words that for some reason I have never forgotten: “No doubt”, he said, “we were both in that little place for the same reason. The good, the true, the beautiful: within that triangle (or rather, upon that point; for ‘truth’ is but to say that beauty and goodness are the ultimate reality; and goodness is servant to beauty), are not the Gods protean?” Rank bad philosophy, as I soon learned when I had made some progress in metaphysics. And yet it was out of such marsh-fires that he built up in secret places of his mind (as, from time to time in our long friendship, I have from fleeting revelations and rare partial confidences discovered), a palace of pleasure or house of heart’s desire, a creed, a myth, a fabric of pure poetry, more solid in its specifications and more concrete in its strange glorious fictions and vanities beyond opium or madness than this world is, and this life that we call real. And more than that, for he moulded life to his dreams; and, besides his poems and writings “more lasting than brass”, his paintings and sculptures that are scrambled for by the picture-galleries of Europe, and those other (perhaps the most astounding) monuments of his genius, the communities of men who have felt the iron and yet beneficent might of his statecraft, as here in Lofoten – besides all these things, I know very well that he found in this Illusion of Illusions a something potent as the fabled unction of the Styx, so that no earthly loss, pain, or grief, could touch him.

‘It was not until after many years of friendship that I got some inkling of the full power of this consolation; for he never wore his heart for daws to peck at. The bare facts I was soon informed of: his marriage, when he was not yet twenty-six, and she barely twenty, to the beautiful and brilliant Lady Mary Scarnside, and her death fifteen years later in a French railway accident along with their only child, a girl. This tragedy took place about two years before our meeting in Mardale church. Lessingham never talked of his wife. I learned that he had, soon after her death, deliberately burnt down their lovely old house in Wastdale. I never saw her portrait: several, from his own brush, were destroyed in the fire; he told me, years later, that he had subsequently bought up every picture or photograph of her that he could trace, and destroyed them. Like most men who are endowed with vigorous minds and high gifts of imagination, Lessingham was, for as long as I have known him, a man of extreme attractiveness to women, and a man to whom (as to his imperial ancestor) women and the beauty of women were as mountain air and sunshine. The spectacle of the unbroken succession and variety of ladies, who crowned, like jewels, the ever increasing splendour and pomp of his existence, made me think that his marriage had been without significance, and that he never spoke of his wife because he had forgotten her. Later, when I heard about the burnt portraits, I changed my mind and supposed he had hated her. It was only when our friendship had ripened to a deep understanding in which words were scarcely needed as messengers between our minds, that I realized how things stood: that it was only his majestic if puerile belief in her personal immortality, and his own, beyond the grave, that upheld him in all the storm and peace and magnificence and high achievement of the years (fifty, as it turned out) that he was to live on without her.

‘These pragmatical sophisters, with their loose psychology and their question-begging logic-chopping that masquerades as metaphysic! I would almost give them leave to gag truth and lead the world by the nose like a jackass, if they could but be men as this man, and bend error and self-deception to high and lofty imaginings as he did. For it is certain mankind would build better if they built for themselves; few can love and tender an unknown posterity. But this man, as I have long observed him, looked on all things sub specie æternitatis; his actions all moved (like the slow procession of this northern summer night) to slow perfection, where the common run of men spoil all in their makeshift hurry. If he followed will-o’-the-wisps in metaphysics, they proved safe lights for him in practical affairs. He was neither deceived nor alarmed by the rabble’s god, mere Quantity, considering that if you inflate it big enough the Matterhorn becomes as insignificant as a grain of sand, since the eye can no longer perceive it, and that a nebula in which our whole earth would be but as a particle in a cloud of tobacco-smoke is (unless as a whetter of imagination’s appetite), more unimportant than that smoke, because further divorced from life. And so, with sound wisdom, he applied all his high gifts of nature, and that sceptre which his colossal wealth set ready in his hand, not to dissipate them in the welter of the world, but to fields definite enough to show the effect. And for all his restless vigour and love of action, he withheld himself as a rule from action in the world, except where he could find conditions, as in Paraguay and again in Lofoten, outside the ordinary texture of modern life. For he felt, I think, by a profound instinct, that in modern life action swallows up the individual. There is no scope for a good climber, he said, to show his powers in a quagmire. Well, it is night now; and no more climbing.’

It was not until I had ended that I felt I had been making something of a fool of myself, letting my thoughts run away with my tongue. For some minutes there was silence, broken only by the solemn ticking of the clock, and now and then a sea-bird’s desolate cry without. Then the Señorita’s voice stole on the silence as a meteor steals across darkness: ‘All must pass away, all must break at last, everything we care for: lips wither, the bright brain grow dim, “the vine, the woman, and the rose”: even the names, even the mention and remembrance of created things, must die and be forgotten; until at last not these only, but death and oblivion itself must – cease, dissipated in that infinite frost of illimitable nothingness of space and time, for ever and ever and ever.’

I listened with that sensation of alternating strain and collapse of certain muscles which belongs to some dreams where the dreamer climbs insecurely from frame to frame over rows of pictures hung on a wall of tremendous height below which opens the abyss. Hitherto the mere conception of annihilation (when once I had imaginatively compassed it, as now and then I have been able to do, lying awake in the middle of the night) had had so much power of horror upon me that I could barely refrain from shrieking in my bed. But now, for the first time in my life, I found I could look down from that sickening verge steadfastly and undismayed. It seemed a strange turn, that here in death’s manifest presence I, for the first time, found myself unable seriously to believe in death.

My outward eyes were on Lessingham’s face, the face of an Ozymandias. My inward eye searched the night, plunging to those deeps beyond the star-shine where, after uncounted millions of light-years’ journeying, the two ends of a straight line meet, and the rays complete the full circle on themselves; so that what to my earthly gaze shows as this almost indiscernible speck of mist, seen through a gap in the sand-strewn thousands of the stars of the Lion, may be but the back view of the very same unknown cosmic island of suns and galaxies which (as a like unremarkable speck) faces my searching eye in the direct opposite region of the heavens, in the low dark sign of Capricorn.

Then, as another meteor across darkness: ‘Many have blasphemed God for these things,’ she said; ‘but without reason, surely. Shall infinite Love that is able to wield infinite Power be subdued to our necessities? Must the Gods make haste, for Whom no night cometh? Is there a sooner or a later in Eternity? Have you thought of this: you had an evil dream: you were in hell that night; yet you woke and forgot it utterly. Are you tonight any jot the worse for it?’

She seemed to speak of forgotten things that I had known long ago and that, remembered now, brought back all that was lost and healed all sorrows. I had no words to answer her, but I thought of Lessingham’s poems, and they seemed to be, to this mind she brought me to, as shadows before the sun. I reached down from the shelf at my left, beside the window, a book of vellum with clasps of gold. ‘Lessingham shall answer you from this book,’ I said, looking up at her where she sat against the sunset. The book opened at his rondel of Aphrodite Ourania. I read it aloud. My voice shook, and marred the reading:

Between the sunset and the sea

The years shall still behold Your glory,

Seen through this troubled fantasy

Of doubtful things and transitory.

Desire’s clear eyes still search for Thee

Beyond Time’s transient territory,

Upon some flower-robed promontory

Between the sunset and the sea.

Our Lady of Paphos: though a story

They count You: though Your temples be

Time-wrecked, dishonoured, mute and hoary—

You are more than their philosophy.

Between the sunset and the sea

Waiteth Your eternal glory.

While I read, the Señorita sat motionless, her gaze bent on Lessingham. Then she rose softly from her seat in the window and stood once more in that place where I had first seen her that night, like the Queen of Love sorrowing for a great lover dead. The clock ticked on, and I measured it against my heart-beats. An unreasoning terror now took hold of me, that Death was in the room and had laid on my heart also his fleshless and icy hand. I dropped the book and made as if to rise from my seat, but my knees gave way like a drunken man’s. Then with the music of her voice, speaking once more, as if love itself were speaking out of the interstellar spaces from beyond the mists of time and desolation and decay, my heart gave over its fluttering and became quiet like a dove held safe in its mistress’s hand. ‘It is midnight now,’ she said. ‘Time to say farewell, seal the chamber, and light the pyre. But first you have leave to look upon the picture, and to read that which was written.’

At the time, I wondered at nothing, but accepted, as in a dream, her knowledge of this secret charge bequeathed to me by Lessingham through sealed instructions locked in a fireproof box which I had only opened on his death, and of which he had once or twice assured me that no person other than himself had seen the contents. In that box was a key of gold, and with that I was at midnight of his death-day to unlock the folding doors of a cabinet that was built into the wall above his bed, and so leave him lying in state under the picture that was in the cabinet. And I must seal the room, and burn up Digermulen castle, and him and all that was in it, as he had burnt up his house in Wastdale fifty years before. And he had let me know that in that cabinet was his wife’s picture, painted by himself, his masterpiece never seen by living eye except the painter’s and the sitter’s; the only one of all her pictures that he had spared.

The cabinet doors were of black lacquer and gold, flush with the wall. I turned the golden key, and opened them left and right. My eyes swam as I looked upon that loveliness that showed doubtfully in the glittering candlelight and the diffused rosy dusk from without. I saw well now that this great picture had been painted for himself alone. A sob choked me as I thought of this last pledge of our friendship, planned by him so many years ago to speak for him to me from beyond death, that my eyes should be allowed to see his treasure before it was committed, with his own mortal remains, to the consuming element of fire. And now I saw how upon the inside panels of the cabinet was inlaid (by his own hand, I doubt not) in letters of gold this poem, six stanzas upon either door:

A VISION OF ZIMIAMVIA

I will have gold and silver for my delight:

Hangings of red silk, purfled and worked in gold

With mantichores and what worse shapes of fright

Terror Antiquus spawn’d in the days of old.

I will have columns of Parian vein’d with gems,

Their capitals by Pheidias’ self design’d,

By his hand carv’d, for flowers with strong smooth stems,

Nepenthe, Elysian Amaranth, and their kind.

I will have night: and the taste of a field well fought,

And a golden bed made wide for luxury;

And there – since else were all things else prov’d naught –

Bestower and hallower of all things: I will have Thee.

—Thee, and hawthorn time. For in that new birth though all

Change, you I will have unchang’d: even that dress,

So fall’n to your hips as lapping waves should fall:

You, cloth’d upon with your beauty’s nakedness.

The line of your flank: so lily-pure and warm:

The globéd wonder of splendid breasts made bare:

The gleam, like cymbals a-clash, when you lift your arm;

And the faun leaps out with the sweetness of red-gold hair.

My dear – my tongue is broken: I cannot see:

A sudden subtle fire beneath my skin

Runs, and an inward thunder deafens me,

Drowning mine ears: I tremble. – O unpin

Those pins of anachite diamond, and unbraid

Those strings of margery-pearls, and so let fall

Your python tresses in their deep cascade

To be your misty robe imperial—

The beating of wings, the gallop, the wild spate,

Die down. A hush resumes all Being, which you

Do with your starry presence consecrate,

And peace of moon-trod gardens and falling dew.

Two are our bodies: two are our minds, but wed.

On your dear shoulder, like a child asleep,

I let my shut lids press, while round my head

Your gracious hands their benediction keep.

Mistress of my delights; and Mistress of Peace:

O ever changing, never changing, You:

Dear pledge of our true love’s unending lease,

Since true to you means to mine own self true—

I will have gold and jewels for my delight:

Hyacinth, ruby, and smaragd, and curtains work’d in gold

With mantichores and what worse shapes of fright

Terror Antiquus spawn’d in the days of old.

Earth I will have, and the deep sky’s ornament:

Lordship, and hardship, and peril by land and sea—

And still, about cock-shut time, to pay for my banishment,

Safe in the lowe of the firelight I will have Thee.

Half blinded with tears, I read the stanzas and copied them down. All the while I was conscious of the Señorita’s presence at my side, a consciousness from which in some irrational way I seemed to derive an inexplicable support, beyond comprehension or comparisons. These were things which by all right judgement it was unpardonable that any living creature other than myself should have looked upon. Yet of the lightness of her presence (more, of its deep necessity), my sense was so lively as to pass without remark or question. When I had finished my writing, I saw that she had not moved, but remained there, very still, one hand laid lightly on the bedpost at the foot of the bed, between the ears of the great golden hippogriff. I heard her say, faint as the breath of night-flowers under the stars: ‘The fabled land of ZIMIAMVIA. Is it true, will you think, which poets tell us of that fortunate land: that no mortal foot may tread it, but the blessed souls do inhabit it of the dead that be departed: of them that were great upon earth and did great deeds when they were living, that scorned not earth and the delights and the glories of earth, and yet did justly and were not dastards nor yet oppressors?’

‘Who knows?’ I said. ‘Who dares say he knows?’

Then I heard her say, in her voice that was gentler than the glow-worm’s light among rose-trees in a forgotten garden between dewfall and moonrise: Be content. I have promised and I will perform.

And as my eyes rested on that strange woman’s face, it seemed to take upon itself, as she looked on Lessingham dead, that unsearchable look, of laughter-loving lips divine, half closed in a grave expectancy, of infinite pity, infinite patience, and infinite sweetness, which sits on the face of Praxiteles’s Knidian Aphrodite.

ZIMIAMVIA (#ulink_86b70eec-43e6-53b0-b764-cd19508b086f)

PRINCIPAL PERSONS

LESSINGHAM

BARGANAX

FIORINDA

ANTIOPE

I A SPRING NIGHT IN MORNAGAY (#ulink_e34d3c11-6560-5bd5-b31e-5dd9ff67d92f)

A COMMISSION OF PERIL • THE THREE KINGDOMS MASTERLESS • POLICY OF THE VICAR • THE PROMISE HEARD IN ZIMIAMVIA.

‘BY all accounts, ’twas to give him line only,’ said Amaury; ‘and if King Mezentius had lived, would have been war between them this summer. Then he should have been boiled in his own syrup; and ’tis like danger now, though smaller, to cope the son. You do forget your judgement, I think, in this single thing, save which I could swear you are perfect in all things.’

Lessingham made no answer. He was gazing with a strange intentness into the wine which brimmed the crystal goblet in his right hand. He held it up for the bunch of candles that stood in the middle of the table to shine through, turning the endless stream of bubbles into bubbles of golden fire. Amaury, half facing him on his right, watched him. Lessingham set down the goblet and looked round at him with the look of a man awaked from sleep.

‘Now I’ve angered you,’ said Amaury. ‘And yet, I said but true.’

As a wren twinkles in and out in a hedgerow, the demurest soft shadow of laughter came and went in Lessingham’s swift grey eyes. ‘What, were you reading me good counsel? Forgive me, dear Amaury: I lost the thread on’t. You were talking of my cousin, and the great King, and might-a-beens; but I was fallen a-dreaming and marked you not.’

Amaury gave him a look, then dropped his eyes. His thick eyebrows that were the colour of pale rye-straw frowned and bristled, and beneath the sunburn his face, clear-skinned as a girl’s, flamed scarlet to the ears and hair-roots, and he sat sulky, his hands thrust into his belt at either side, his chin buried in his ruff. Lessingham, still leaning on his left elbow, stroked the black curls of his mustachios and ran a finger slowly and delicately over the jewelled filigree work of the goblet’s feet. Now and again he cocked an eye at Amaury, who at last looked up and their glances met. Amaury burst out laughing. Lessingham busied himself still for a moment with the sparkling, rare, and sunset-coloured embellishments of the goldsmith’s art, then, pushing the cup from him, sat back. ‘Out with it,’ he said; ‘’tis shame to plague you. Let me know what it is, and if it be in my nature I’ll be schooled.’

‘Here were comfort,’ said Amaury; ‘but that I much fear ’tis your own nature I would change.’

‘Well, that you will never do,’ answered he.

‘My lord,’ said Amaury, ‘will you resolve me this: Why are we here? What waiting for? What intending?’

Lessingham stroked his beard and smiled.

Amaury said. ‘You see, you will not answer. Will you answer this, then: It is against the nature of you not to be rash, and against the condition of rashness not to be ’gainst all reason; yet why (after these five years that I’ve followed you up and down the world, and seen you mount so swiftly the degrees and steps of greatness that, in what courts or princely armies soever you might be come, you stuck in the eyes of all as the most choice jewel there): why needs must you, with the wide world to choose from, come back to this land of Rerek, and, of all double-dealers and secretaries of hell, sell your sword to the Vicar?’

‘Not sell, sweet Amaury,’ answered Lessingham. ‘Lend. Lend it in cousinly friendship.’

Amaury laughed. ‘Cousinly friendship! Give us patience! With the Devil and him together on either hand of you!’ He leapt up, oversetting the chair, and strode to the fireplace. He kicked the logs together with his heavy riding-boots, and the smother of flame and sparks roared up the chimney. Turning about, his back to the fire, feet planted wide, hands behind him, he said: ‘I have you now in a good mood, though ’twere over much to hope you reasonable. And now you shall listen to me, for your good. You do know me: am I not myself by complexion subject to hasty and rash motions? Yet I it is must catch at your bridle-rein; for in good serious earnest, you do make toward most apparent danger, and no tittle of advantage to be purchased by it. Three black clouds moving to a point; and here are you, in the summer and hunting-season of your youth, lying here with your eight hundred horse these three days, waiting for I know not what cat to jump, but (as you have plainly told me) of a most set obstinacy to tie yourself hand and heart to the Vicar’s interest. You have these three months been closeted in his counsels: that I forget not. Nor will I misprise your politic wisdom: you have played chess with the Devil ere now and given him stalemate. But ’cause of these very things, you must see the peril you stand in: lest, if by any means he should avail to bring all things under his beck, he should then throw you off and let you hop naked; or, in the other event, and his ambitious thoughts should break his neck, you would then have raised up against yourself most bloody and powerful enemies.

‘Look but at the circumstance. This young King Styllis is but a boy. Yet remember, he is King Mezentius’ son; and men look not for lapdog puppies in the wolf’s lair, nor for milksops to be bred up for heirship to the crown and kingdom of Fingiswold. And he is come south not to have empty homage only from the regents here and in Meszria, but to take power. I would not have you build upon the Duke of Zayana’s coldness to his young brother. True, in many families have the bastards been known the greater spirits; and you did justly blame the young King’s handling of the reins in Meszria when (with a warmth from which his brother could not but take cold) he seemed to embrace to his bosom the lord Admiral, and in the same hour took away with a high hand from the Duke a great slice of his appanage the King their father left him. But though he smart under this neglect, ’tis not so likely he’ll go against his own kindred, nor even stand idly by, if it come to a breach ’twixt the King and the Vicar. What hampers him today (besides his own easeful and luxurious idleness) is the Admiral and those others of the King’s party, sitting in armed power at every hand of him in Meszria; but let the cry but be raised there of the King against the Vicar, and let Duke Barganax but shift shield and declare himself of’s young brother’s side, why then you shall see these and all Meszria stand in his firm obedience. Then were your cousin the Vicar ta’en betwixt two millstones; and then, where and in what case are you, my lord? And this is no fantastical scholar’s chop-logic, neither: ’tis present danger. For hath not he for weeks now set every delay and cry-you-mercy and procrastinating stop and trick in the way of a plain answer to the young King’s lawful demand he should hand over dominion unto him in Rerek?’

‘Well,’ said Lessingham, ‘I have listened most obediently. You have it fully: there’s not a word to which I take exceptions. Nay I admire it all, for indeed I told you every word of it myself last night.’

‘Then would to heaven you’d be advised by’t,’ said Amaury. ‘Too much light, I think, hath made you moon-eyed.’

‘Reach me the map,’ said Lessingham. For the instant there was a touch in the soft bantering music of his voice as if a blade had glinted out and in again to its velvet scabbard. Amaury spread out the parchment on the table, and they stood poring over it. ‘You are a wiser man in action, Amaury, in natural and present, than in conceit; standing still, stirs your gall up: makes you see bugs and hobthrushes round every corner. Am I yet to teach you I may securely dare what no man thinks I would dare, which so by hardness becometh easy?’

Lessingham laid his forefinger on this place and that while he talked. ‘Here lieth young Styllis with’s main head of men, a league or more be-east of Hornmere. ’Tis thither he hath required the Vicar come to him to do homage of this realm of Rerek, and to lay in his hands the keys of Kessarey, Megra, Kaima, and Argyanna, in which the King will set his own captains now. Which once accomplished, he hath him harmless (so long, at least, as Barganax keep him at arm’s length); for in the south there they of the March openly disaffect him and incline to Barganax, whose power also even in this northern ambit stands entrenched in’s friendship with Prince Ercles and with Aramond, spite of all supposed alliances, respects, and means, which bind ’em tributary to the Vicar.

‘But now to the point of action; for ’tis needful you should know, since we must move north by great marches, and that this very night. My noble cousin these three weeks past hath, whiles he amused the King with’s chaffer-talk of how and wherefore, opened unseen a dozen sluices to let flow to him in Owldale men and instruments of war, armed with which strong arguments (I have it by sure intelligence but last night) he means tomorrow to obey the King’s summons beside Hornmere. And, for a last point of logic, in case there be falling out between the great men and work no more for learned doctors but for bloody martialists, I am to seize the coast-way ’twixt the Swaleback fells and Arrowfirth and deny ’em the road home to Fingiswold.’

‘Deny him the road home?’ said Amaury. ‘’Tis war, then, and flat rebellion?’

‘That’s as the King shall choose. And so, Amaury, about it straight. We must saddle an hour before midnight.’

Amaury drew in his breath and straightened his back. ‘An hour to pack the stuff and set all in marching trim: and an hour before midnight your horse is at the door.’ With that, he was gone.

Lessingham scanned the map for yet a little while, then let it roll itself up. He went to the window and threw it open. There was the breath of spring in the air and daffodil scents: Sirius hung low in the south-west.

‘Order is ta’en according to your command,’ said Amaury suddenly at his side. ‘And now, while yet is time to talk and consider, will you give me leave to speak?’

‘I thought you had spoke already,’ said Lessingham, still at the window, looking round at him. ‘Was all that but the theme given out, and I must now hear point counterpoint?’

‘Give me your sober ear, my lord, but for two minutes together. You know I am yours, were you bound for the slimy strand of Acheron. Do but consider; I think you are in some bad ecstasy. This is worse than all: cut the lines of the King’s communications northward, in the post of main danger, with so little a force, and Ercles on your flank ready to stoop at us from his high castle of Eldir and fling us into the sea.’

‘That’s provided for,’ said Lessingham: ‘he’s made friends with as for this time. Besides, he and Aramond are the Duke’s dogs, not the King’s; ’tis Meszria, Zayana, all their strings hold unto; north winds bring ’em the cough o’ the lungs. Fear not them.’

Amaury came and leaned himself too on the window-sill, his left elbow touching Lessingham’s. After a while he said, low and as if the words were stones loosed up one by one with difficulty from a stiff clay soil, ‘’Fore heaven, I must love you; and it is a thing not to be borne that your greatness should be made but this man’s cat’s-paw.’

Sirius, swinging lower, touched the highest tracery of a tall ash-tree, went out like a blown-out candle behind a branch, and next instant blazed again, a quintessential point of diamond and sapphire and emerald and amethyst and dazzling whiteness. Lessingham answered in a like low tone, meditatively, but his words came light on an easy breath: ‘My cousin. He is meat and drink to me. I must have danger.’

They abode silent at that window, drinking those airs more potent than wine, and watching, with a deep compulsive sense of essence drawn to essence, that star’s shimmer of many-coloured fires against the velvet bosom of the dark; which things drew and compelled their beings, as might the sweet breathing nearness of a woman lovely beyond perfection and deeply beyond all soundings desired. Lessingham began to say slowly, ‘That was a strange trick of thought when I forgot you but now, and forgot my own self too, in those bubbles which in their flying upward signify not as the sparks, but that man is born for gladness. For I thought there was a voice spake in my ear in that moment and I thought it said, I have promised and I will perform. And I thought it was familiar to me beyond all familiar dear lost things. And yet ’tis a voice I swear I never heard before. And like a star-gleam, it was gone.’

The gentle night seemed to turn in her sleep. A faint drumming, as of horse-hooves far away, came from the south. Amaury stood up, walked over to the table, and fell to looking at the map again. The beating of hooves came louder, then on a sudden faint again. Lessingham said from the window, ‘There’s one rideth hastily. Now a cometh down to the ford in Killary Bottom, and that’s why we lose the sound for awhile. Be his answers never so good, let him not pass nor return, but bring him to me.’

II THE DUKE OF ZAYANA (#ulink_c08ba25c-2dca-5a44-a88e-01907a517b6a)

PORTRAIT OF A LADY • DOCTOR VANDERMAST • FIORINDA: ‘BITTER-SWEET’ • THE LYRE THAT SHOOK MITYLENE

THE third morning after that coming of the galloping horseman north to Mornagay, Duke Barganax was painting in his privy garden in Zayana in the southland: that garden where it is everlasting afternoon. There the low sun, swinging a level course at about that pitch which Antares reaches at his highest southing in an English May-night, filled the soft air with atomies of sublimated gold, wherein all seen things became, where the beams touched them, golden: a golden sheen on the lake’s unruffled waters beyond the parapet, gold burning in the young foliage of the oak-woods that clothed the circling hills; and, in the garden, fruits of red and yellow gold hanging in the gold-spun leafy darkness of the strawberry-trees, a gilding shimmer of it in the stone of the carven bench, a gilding of every tiny blade on the shaven lawn, a glow to deepen all colours and to ripen every sweetness: gold faintly warming the proud pallour of Fiorinda’s brow and cheek, and thrown back in sudden gleams from the jet-black smoothnesses of her hair.

‘Would you be ageless and deathless for ever, madam, were you given that choice?’ said the Duke, scraping away for the third time the colour with which he had striven to match, for the third time unsuccessfully, the unearthly green of that lady’s eyes.

‘I am this already,’ answered she with unconcern.

‘Are you so? By what assurance?’

‘By this most learn’d philosopher’s, Doctor Vandermast.’

The Duke narrowed his eyes first at his model then at his picture: laid on a careful touch, stood back, compared them once more, and scraped it out again. Then he smiled at her: ‘What? Will you believe him? Do but look upon him where he sitteth there beside Anthea, like winter wilting before Flora in her pride. Is he one to inspire faith in such promises beyond all likelihood and known experiment?’

Fiorinda said: ‘He at least charmed you this garden.’

‘Might he but charm your eyes,’ said the Duke, ‘to some such unaltering stability, I’d paint ’em; but now I cannot. And ’tis best I cannot. Even for this garden, if ’twere as you said, madam (or worse still, were you yourself so), my delight were poisoned. This eternal golden hour must lose its magic quite, were we certified beyond doubt or heresy that it should not, in the next twinkling of an eye, dissipate like mist and show us the work-a-day morning it conceals. Let him beware, and if he have art indeed to make safe these things and freeze them into perpetuity, let him forbear to exercise it. For as surely as I have till now well and justly rewarded him for what good he hath done me, in that day, by the living God, I will smite off his head.’

The Lady Fiorinda laughed luxuriously, a soft, mocking laugh with a scarce perceptible little contemptuous upward nodding of her head, displaying the better with that motion her throat’s lithe strong loveliness. For a minute, the Duke painted swiftly and in silence. Hers was a beauty the more sovereign because, like smooth waters above a whirlpool, it seemed but the tranquillity of sleeping danger: there was a taint of harsh Tartarean stock in her high flat cheekbones, and in the slight upward slant of her eyes; a touch of cruelty in her laughing lips, the lower lip a little too full, the upper a little too thin; and in her nostrils, thus dilated, like a beautiful and dangerous beast’s at the smell of blood. Her hair, parted and strained evenly back on either side from her serene sweet forehead, coiled down at last in a smooth convoluted knot which nestled in the nape of her neck like a black panther asleep. She wore no jewel nor ornament save two escarbuncles, great as a man’s thumb, that hung at her ears like two burning coals of fire. ‘A generous prince and patron indeed,’ she said; ‘and a most courtly servant for ladies, that we must rot tomorrow like the aloe-flower, and all to sauce his dish with a biting something of fragility and non-perpetuity.’