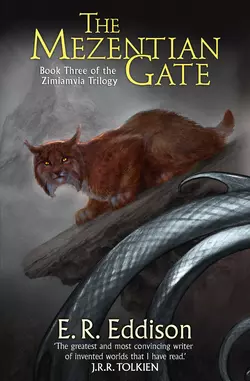

The Mezentian Gate

E. R. Eddison

Paul Thomas Edmund

The third volume in the classic epic trilogy of parallel worlds, admired by Tolkien and the great prototype for The Lord of the Rings and modern fantasy fiction.E. R. Eddison was the author of three of the most remarkable fantasies in the English language: The Worm Ouroboros, Mistress of Mistresses and A Fish Dinner in Memison. Linked together as separate parts of one vast romantic epic, fans who clamoured for more were finally rewarded 13 years after Eddison’s death with the publication of the uncompleted fourth novel, written during the dark years of the Second World War.This new edition of The Mezentian Gate includes additional narrative fragments of the story missing from the original 1958 edition. Together with an illuminating introduction by Eddison scholar Paul Edmund Thomas, this volume returns Edward Lessingham to the extravagant realm of Zimiamvia and concludes one of the most extraordinary and influential fantasy series ever written.

Copyright (#ulink_096ec862-eab9-504a-b732-d2ac535d8da4)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Introduction © Paul Edmund Thomas 1992

Copyright © E.R. Eddison 1958, 1992

Jacket illustration by John Howe © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 2014

E.R. Eddison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578177

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007578184

Version: 2014-09-16

Dedication (#ulink_a2245c72-3720-5b19-9bc9-f8e0624e879d)

To you, madonna mia,

WINIFRED GRACE EDDISON

and to my mother,

HELEN LOUISA EDDISON

and to my friends,

JOHN AND ALICE REYNOLDS

and to

HARRY PIRIE-GORDON

a fellow explorer in whom (as in Lessingham)

I find that rare mixture of man of action and

connoisseur of strangeness and beauty in their

protean manifestations, who laughs where I laugh

and likes the salt that I like, and to whom I owe

my acquaintance (through the Orkneyinga Saga)

with the earthly ancestress

of my Lady Rosma Parry

I dedicate this book.

E. R. E.

Proper names the reader will no doubt pronounce as he chooses. But perhaps, to please me, he will keep the i’s short in Zimiamvia and accent the third syllable: accent the second syllable in Zayana, give it a broad a (as in ‘Guiana’), and pronouce the ay in the first syllable – and the ai in Laimak, Kaima, etc., and the ay in Krestenaya – like the ai in ‘aisle’; keep the g soft in Fingiswold: let Memison echo ‘denizen’ except for the m: accent the first syllable in Rerek and make it rhyme with ‘year’: pronounce the first syllable of Reisma ‘rays’; remember that Fiorinda is in origin an Italian name, Amaury, Amalie, and Beroald French, and Antiope, Zenianthe, and a good many others, Greek: last, regard the sz in Meszria as ornamental, and not be deterred from pronouncing it as plain ‘Mezria’.

Let me not to the marriage of true mindes

Admit impediments, love is not love

Which alters when it alteration findes,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no, it is an ever fixed marke

That lookes on tempests, and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandring barke,

Whose worths unknowns, although his higth be taken.

Love’s not Times foole, though rosie lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickles compasse come,

Love alters not with his breefe houres and weekes,

But beares it out even to the edge of doome:

If this be error, and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

SHAKESPEARE

And ride in triumph through Persepolis!

Is it not brave to be a King, Techelles?

Usumcasane and Theridamas,

Is it not passing brave to be a King,

And ride in triumph through Persepolis?

MARLOWE

I cannot conceive any beginning of such love as I have for you but Beauty. There may be a sort of love for which, without the least sneer at it, I have the highest respect and can admire it in others: but it has not the richness, the bloom, the full form, the enchantment of love after my own heart.

KEATS

CONTENTS

Cover (#ubcb284e4-3637-5402-96c2-cc08cdd3d687)

Title Page (#ud2ea0fbc-c94b-5a06-82de-4e981106089f)

Copyright (#uc76efe89-a556-5b38-b7c6-5c5f33cd39e1)

Dedication (#u7c988c40-3cd8-56eb-892f-ecdbaa707746)

Epigraph (#u057c6120-693a-56a8-bd02-80c48e4e2120)

Introduction by Paul Edmund Thomas (#udff319c8-c4bc-59c1-87a9-58c2c372d6b0)

Prefatory Note by Colin Rücker Eddison (#u20fb622b-4516-5c5e-8abc-c7bde3ae6559)

LETTER OF INTRODUCTION (#u3bb3ed3c-ba06-5dce-9ada-6ff42ebe9afc)

PRAELUDIUM: LESSINGHAM ON THE RAFTSUND (#uc5deba9a-44cb-5779-983a-411b366b85f6)

BOOK ONE: FOUNDATIONS (#u1e93ceab-cf99-5345-9c4d-a11da6a650fe)

I. Foundations in Rerek (#u41e0d857-024e-53d8-b98d-8a11781b8cc5)

II. Foundations in Fingiswold (#u92d3b99f-4ada-5cd5-8789-27adfdaf083e)

III. Nigra Sylva, where the Devils Dance (#ua8c660c7-359f-5952-b397-e4053b59bc03)

IV. The Bolted Doors (#litres_trial_promo)

V. Princess Marescia (#litres_trial_promo)

VI. Prospect North from Argyanna (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK TWO: UPRISING OF KING MEZENTIUS (#litres_trial_promo)

VII. Zeus Terpsikeraunos (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII. The Prince Protector (#litres_trial_promo)

IX. Lady Rosma in Acrozayana (#litres_trial_promo)

X. Stirring of the Eumenides (#litres_trial_promo)

XI. Commodity of Nephews (#litres_trial_promo)

XII. Another Fair Moonshiny Night (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK THREE: THE AFFAIR OF REREK (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII. The Devil’s Quilted Anvil (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV. Lord Emmius Parry (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK FOUR: THE AFFAIR OF MESZRIA (#litres_trial_promo)

XV. Queen Rosma (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI. Lady of Presence (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII. Akkama Brought into the Dowry (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII. The She-Wolf Tamed to Hand (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX. The Duchess of Memison (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK FIVE: THE TRIPLE KINGDOM (#litres_trial_promo)

XX. Dura Papilla Lupae (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI. Anguring Combust (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII. Pax Mezentiana (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIII. The Two Dukes (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIV. Prince Valero (#litres_trial_promo)

XXV. Lornra Zombremar (#litres_trial_promo)

XXVI. Rebellion in the Marches (#litres_trial_promo)

XXVII. Third War with Akkama (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK SIX: LA ROSE NOIRE (#litres_trial_promo)

XXVIII. Anadyomene (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIX. Astarte (#litres_trial_promo)

XXX. Laughter-loving Aphrodite (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXI. The Beast of Laimak (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXII. Then, Gentle Cheater (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXIII. Aphrodite Helikoblepharos (#litres_trial_promo)

The Fish Dinner: Transitional Note (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK SEVEN: TO KNOW OR NOT TO KNOW (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXIV. The Fish Dinner: First Digestion (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXV. Diet a Cause (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXVI. Rosa Mundorum (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXVII. Testament of Energeia (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXVIII. Call of the Night-Raven (#litres_trial_promo)

XXXIX. Omega and Alpha in Sestola (#litres_trial_promo)

GENEALOGICAL TABLES (#litres_trial_promo)

MAP OF THE THREE KINGDOMS (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by E. R. Eddison (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_2068f383-dcae-5aaa-af62-6f1dc7486e0d)

BY PAUL EDMUND THOMAS (#ulink_2068f383-dcae-5aaa-af62-6f1dc7486e0d)

THE twelfth chapter of E. R. Eddison’s first novel, The Worm Ouroboros, contains a curious episode extraneous to the main plot. Having spent nearly all their strength in climbing Koshtra Pivrarcha, the highest mountain pinnacle on waterish Mercury, the Lords Juss and Brandoch Daha stand idly enjoying the glory of their singular achievement atop the frozen wind-whipped summit, and they gaze away southward into a mysterious land never before seen:

Juss looked southward where the blue land stretched in fold upon fold of rolling country, soft and misty, till it melted in the sky. ‘Thou and I,’ said he, ‘first of the children of men, now behold with living eyes the fabled land of Zimiamvia. Is that true, thinkest thou, which philosophers tell us of that fortunate land: that no mortal foot may tread it, but the blessed souls do inhabit it of the dead that be departed, even they that were great upon earth and did great deeds when they were living, that scorned not earth and the delights and the glories thereof, and yet did justly and were not dastards nor yet oppressors?’

‘Who knoweth?’ said Brandoch Daha, resting his chin in his hand and gazing south as in a dream. ‘Who shall say he knoweth?’

The land of Zimiamvia probably held only a fleeting and evanescent place in the minds of Eddison’s readers in 1922, because this, the first and last mentioning of Zimiamvia in Ouroboros, flits quickly past the reader, and though it has a local habitation and a name, it does not have a place in the story. Yet in the author’s mind, the name rooted itself so deeply that its engendering and growth cannot be clearly traced. Where did this name and this land come from? How and when was Zimiamvia born? How, while writing Ouroboros in 1921, did Eddison come to think of including this extraneous description of a land inconsequential to the story? Why did he include it?

Who knows? Who shall say he knows? No living person can answer these questions with certainty. What is certain is that Zimiamvia existed in Eddison’s imagination for at least twenty-three years and that he spent much of the rare leisure time of his last fifteen years writing three novels to give tangible shape to that misty land whose existence the Lords Juss and Brandoch Daha ponder and question in those moments on the ice-clad jagged peak of Koshtra Pivrarcha.

When he finished Ouroboros in 1922, Eddison did not ride the hippogriff-chariot through the heavens to Zimiamvian shores directly. Instead he remained firmly earth-bound and wrote Styrbiorn the Strong, a historical romance based on the life of the Swedish prince Styrbiorn Starki, the son of King Olaf, who died in 983 in an attempt to usurp the kingdom from his uncle, King Eric the Victorious. Eddison finished this novel in December 1925, and on 3 January 1926, during a vacation to Devonshire, he found himself desiring to pay homage to the Icelandic sagas that had inspired so many aspects of Ouroboros and Styrbiorn the Strong: ‘Walking in a gale over High Peak Sidmouth … I thought suddenly that my next job should be a big saga translation, and that should be Egil.’ After noting his decision, he justified it: ‘This may pay back some of my debt to the sagas, to which I owe more than can ever be counted.’ Resolved on this project, he steeped himself for five years in the literary and historical scholarship requisite for translating a thirteenth-century Icelandic text into English. It was not until 1930, after Egil’s Saga had been finished and dispatched to the Cambridge University Press, that Eddison focused his attention on the new world that had lain nearly dormant in his mind since at least 1921. Eddison finished the first Zimiamvian novel, Mistress of Mistresses, in 1935. Faber & Faber published it in England; E. P. Dutton published it in America. Eddison says Mistress of Mistresses did not explore ‘the relations between that other world and our present here and now’, and so his ideas of those relations propelled him to write a second novel setting some scenes in Zimiamvia and others in modern Europe. Eddison finished this second novel, A Fish Dinner in Memison, in 1940, but the wartime paper shortage prevented Faber & Faber from publishing it, yet E. P. Dutton published it for American readers in 1941. Eddison says that writing this second novel made him ‘fall in love with Zimiamvia’, and since ‘love has a searching curiosity which can never be wholly satisfied’, the new ideas sprouting from his love grew into The Mezentian Gate.

Eddison never finished this third Zimiamvian novel, for he died from a massive stroke in 1945. He intended The Mezentian Gate to have thirty-nine chapters. Between 1941 and 1945, he wrote the first seven, the last four, and Chapters XXVIII and XXIX. Like many others, Eddison feared a German invasion of England, and he worried that events beyond his control would prevent his finishing The Mezentian Gate. So before November 1944, he wrote an Argument with Dates, a complete and detailed plot synopsis of all of the unwritten chapters. After completing the Argument and thus assuring himself that his novel’s story, at least, could be published as a whole even if something happened to him, Eddison went on to write drafts for several more chapters during his last year of life. In 1958 his brother Colin Eddison, his friend Sir George Rostrevor Hamilton and Sir Francis Meynell (the founder of the Nonesuch Press and son of the poet Alice Meynell) privately published this fragmentary novel at the Curwen Press in Plaistow, West Sussex. The Curwen edition included only the finished chapters and the Argument; it did not include the substantial number of preliminary drafts for unfinished chapters that Eddison composed between January and August 1945. These drafts, extant in handwritten leaves, have lain in the darkness of manuscript boxes in the underground stacks of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and they have been read by few since Eddison’s death.

In Dell’s 1992 edition, Eddison’s neglected manuscript drafts for The Mezentian Gate were finally brought into the light of print, and for the first time the three Zimiamvian novels were pressed within the covers of one volume and united under the title Zimiamvia.

The Writing of The Mezentian Gate

On 25 July 1941, E. R. Eddison wrote to George Rostrevor Hamilton and told of the birth of The Mezentian Gate: ‘After laborious lists of dates and episodes and so on, extending over many weeks, I really think the scheme for the new Zimiamvian book crystallized suddenly at 9 p.m. last night.’ On 2 September Eddison was still excited about his progress and wrote to Hamilton again: ‘You will be glad to know that about 1500 words of the (still nameless) new Zimiamvian book are already written.’ The opening sections, the Praeludium, which he first called ‘Praeludium in Excelsis’ (literally, ‘a preface set in a high place’), and ‘Foundations in Rerek’ alternately filled the sails of his imagination, but he decided to finish the voyage to Rerek before turning his prow toward Mount Olympus, the original setting for the Praeludium. Seven months later, on 2 April 1942, another letter to Hamilton shows that Eddison’s initial swift sailing had quickly carried his imagination into the doldrums:

I am still struggling with the opening of the new book. The ‘Praeludium in Excelsis’ which I had written dissatisfies me: seems to be ornamental rather than profound. So I’m changing the mise en scene from Olympus to Lofoten, and think it will create the atmosphere I’m sniffing for. But, Lord, it comes out unwillingly and painfully.

Evidently, Eddison abandoned his resolve to finish ‘Foundations in Rerek’ first, and his imagination tacked toward Rerek and Olympus in turns, but without gaining much momentum toward either destination. Eddison eventually completed the Praeludium in July and sent it to Hamilton for a critical reading with this qualifying statement attached: ‘it has given me infinite trouble.’ He did not complete ‘Foundations in Rerek’ until 1 October 1942, fourteen months after he began it.

The two opening sections add up to about ten thousand words, and Eddison spent about 420 days composing them. On a strictly mathematical level, Eddison’s average daily rate of composition was about twenty-five words. Surely a turtle’s pace across the page. Such meticulous slowness seems to mark Eddison’s composition: he once told Edward Abbe Niles, his consulting lawyer in America, that the ten thousand words of the thickly philosophical Chapters XV and XVI of A Fish Dinner in Memison took him ten months of 1937.Yet in 1937, Eddison had little free time for writing because he was fully occupied with civil service as the Head of Empire Trades and Head of the Economic Division in the Department of Overseas Trade. One would expect that in 1942, three years into retired life, Eddison would be composing at a faster rate than during his working life, simply because he had more time for writing, but that is not the case. The explanation lies in our understanding the intrusion of World War II upon Eddison’s life and the response of his dutiful nature to the home effort in the war.

On 10 September 1939, one week after Britain and France had declared war on Germany, Eddison speaks of his domestic preparations for wartime:

ARP curtains, ‘Nox’ lights, and so on have occupied most of my waking hours since the trouble began. We are well blacked out – but what a bore it is, night and morning.’

The annoyed tone of the last sentence is notable. Eddison’s ‘motto’ as he declared it in one letter, was ‘anything for a quiet life.’ After spending most of his years in London, Eddison moved to the countryside near Marlborough to live this desired quiet life in which the breezy hours of sunshine and birdsong could be devoted to writing and reading and happy companionship with his wife and family. To have the bright hope for this life, in its first months, tangibly darkened by blackout curtains, and intangibly darkened by the fear of bombing or invasion, must have been bitterly discouraging. Time was out of joint for Eddison’s retired life.

Some people in Eddison’s position would have ignored the home effort in the war. Eddison could not do this: his long career in government, his interest in history and politics, his patriotism, and his keen sense of responsibility would not allow this in him. In the same letter in which he speaks of hanging the blackout curtains, Eddison tells Hamilton of his volunteering for war service:

I’ve offered my services in general for any local work here that I can tackle: nothing doing so far, but that is hardly surprising. I was going to stage a ‘comeback’ in Whitehall if war burst out a year ago; but fear it would quickly end me were I to attempt it, and that would help nobody. So, I propose to carry on to the best of my ability till a bomb drops on me, or some other form of destruction overtakes me, or till the war comes to an end.

Here is a man fifty-seven and well beyond the age parameters of active military duty, a man recently retired from public life and settled into a new house, a man who retired to devote himself to his personal literary goals, a man not in his best state of health: this man volunteers for war service during the first days of the war. Surely his action reveals a mind instinct with duty.

Only those who lived through the war years in England can truly speak about the anxieties and frustrations of carrying on daily life under the constant danger of the air raids. Living in London, Hamilton felt the German threat closely. On September 13, 1940, he wrote to say that his wife’s mother had come to live at his house, for bombs had fallen perilously near to hers. Plus, Hamilton had gone to work that morning and found the floor of his office covered with shards of window glass shattered by a bomb’s concussion during the previous night. Because he and his family lived in Wiltshire, Eddison did not feel the threat so imminently, and he told Hamilton on September 15, 1940, that although several bombs had fallen in the countryside and one in Marlborough itself, the ‘total casualties and material damage is so far precisely three rabbits!’

Even though the danger was not as grave in Marlborough as it was in London, Eddison’s work as an air raid patrol warden continually interrupted his consciously regular life, a retired life that nevertheless maintained the structure of his working life. On 27 October 1940, Eddison told Hamilton of one incident that exemplifies these interruptions:

I had a complete nuit blanche last Sunday: siren went off and woke me from my first sleep [at] 11.15 p.m.: dressed in five minutes, got here 11.25, and here we were stuck – 3 men and two girls – till 5.50 a.m. Monday, when the siren sounded ‘raiders passed’. No incidents for us to deal with, but they had it in Swindon I gather. Home to bed for ¼ hour, and up, as usual, at 6.30. But, by 9.30 a.m. I was so dead stupid I went to bed and slept till 12.00 and even so pretty washed out for the rest of the day. I don’t know how you folks stick it night after night: I suppose the adaptability of the human frame comes blessedly into play.

Eddison’s coming home to sleep for fifteen minutes and then rising ‘as usual’ at 6.30 seems silly. He was living in retirement without professional responsibilities, and the scheduled hour of his rising from sleep was a demand self-imposed. The consequence of maintaining such rigid regularity on this occasion produced only weariness and inefficiency in the morning. And yet the disciplined Eddison surrendered to the needs of his body reluctantly, for he did not return to bed until three hours later.

Eddison’s ARP work affected the whole of his six years of retired life, but although it was wearying and annoying to him, the ARP work was not the most demanding of the daily tasks that kept him from his writing desk. He begins the 27 October ‘nuit blanche’ letter with a paragraph about gardening:

I’m writing this in the ARP control room: my Sunday morning turn of duty. I boil my egg and have my breakfast about 7 a.m., and get down here by 7.45 and take charge until 11. I like it, because after that my day is free to garden; which at the moment, is a pressing occupation. I’m cleaning the herbaceous border of bindweed, a most pernicious and elusive pest: it takes about 2 hours of hard digging and sorting to do a one foot run, and there are sixty feet to do. And the things are heeled in elsewhere and waiting to be planted when my deinfestation is complete.

For Eddison, gardening was not welcome physical exercise after stiff-backed hours of concentration at the writing table. Rather, gardening was his major occupation during these years; it was the work of duty that had to be done before the work of his heart’s desire. Gardening is, of course, a seasonal work, and the hours Eddison spent at it surely fluctuated, but during the autumnal harvest it took up many hours every day. Eddison told Gerald Hayes in the autumn of 1943 that gardening took 42 hours per week, ARP work took 10 or 11 hours, and that he was also trying to work on The Mezentian Gate every day even if he could only give it one half-hour.

Eddison devoted himself to gardening because the wartime food rationing in England created discomforting shortages, and Eddison wanted to be as self-sufficient as possible so that the rations could be supplemented without having to be relied on. Gardening became more important after the birth of Eddison’s granddaughter Anne in November 1940, because then Eddison had another person to feed besides his wife, Winifred, his daughter Jean, his mother, Helen, when she came to visit, and himself. For Christmas in 1941, Edward Abbe Niles sent the Eddisons food parcels from New York, and on 18 December, Eddison thanked him in a letter: ‘On the whole we don’t do too badly for food … One gets used (though I won’t say reconciled) to short commons in things like bacon and sugar: eggs would be a severe deprivation if one had to depend on a ration, but we have six hens who keep us going with their contributions, and very lucky we are, and wise, to have started keeping them last summer.’ Eddison’s strenuous efforts in the garden, and the clucking efforts of the hens, seem to have been successful in allowing the family to live comfortably. However, Eddison’s daughter Jean says that it was eventually necessary to eat all of the hens, even the ones they had become attached to as household pets.

Although Eddison’s many hours of gardening and ARP work filled his days and sometimes his nights, his letters from the first year and a half of the war do not have a strong tone of frustration over his lack of time for writing. Perhaps the reason is that he was between books during these months. He was busy with matters relating to A Fish Dinner in Memison: rewriting the cricket scene in Chapter III for an American audience unfamiliar with the game, and sending many letters to Niles in regard to the contract with Dutton. These things occupied his writing hours well into the first months of 1941. Also, perhaps he was not frustrated because he was enjoying the sweetness of having finished a work that pleased him well, and he was happily anticipating the publication of A Fish Dinner in Memison in May 1941.

But Eddison was never a dawdler, especially when new ideas arose like breezes to fill the sails of his imagination: only three months after A Fish Dinner in Memison was published, he began working on The Mezentian Gate. A cluster of letters from late in 1941, the period in which Eddison was working on the opening sections, shows his careworn tone and his frustration with the ability of these mundane tasks to balk his efforts to have time for writing. The two most potent letters are enough to show this wearied tone. On 27 November 1941, Eddison wrote to his Welsh friend Lewellyn Griffith:

I too am the sport and shuttlecock of potatoes, onions, carrots, beets, turnips, and – for weeks on end – after these are laid to rest – of autumn diggings and sudden arithmetical calculations aiming at a three year rotation of crops scheme for our kitchen garden, to enable me to get on with these jobs without further thought, and learn perhaps to garden as an automaton while my mind works on the tortuous politics of the three kingdoms and the inward beings and outward actors in that play, over a period of eighty years.

The second letter is to Eddison’s American friend Professor Henry Lappin and was written one month after the first:

Forgive a brief letter. I have no leisure for writing – either my next book or the letters I badly owe. For I am already whole time kitchen gardener, coal heaver, and so on, and look likely to become part time cook and housemaid into the bargain, this in addition to my part-time war work; and these daily jobs connected with keeping oneself and family clean, warm, and nourished, leave little enough time for the higher activities. Perhaps this is good for one, for a time; anyway it is part of the price we all have to pay if we want to win this war.

Eddison is tired of his domestic tasks, and in both letters he stresses the time they take up. He also makes a clear separation between these chores and his writing by calling his writing a ‘higher activity’ in the second letter and by stating his mental detachment from gardening in the first letter.

Part of Eddison’s frustration must have stemmed from the sheer size of The Mezentian Gate. The plot of Mistress of Mistresses covers fifteen months; that of A Fish Dinner in Memison, one month. Had he completed the sagalike Mezentian Gate, the plot would have extended over seventy-two years. Considering the number of episodes alone, Eddison’s working on the ‘tortuous politics of the three kingdoms’ over a period of seven decades was the most ambitious goal of imaginative contriving he ever attempted.

Eddison’s progress on The Mezentian Gate crawled doggedly through 1942 and through most of 1943. On 6 November 1943, Eddison wrote to his new friend C. S. Lewis and said that he was feeling joyful about the new progress he was making on the novel. This letter signals the beginning of a nine-month period of fruitful productivity. Though he had been at work on Chapter II, ‘Foundations in Fingiswold’, since he had finished ‘Foundations in Rerek’ in October 1942, Eddison completed Chapters II–VI between December 1943 and 14 February 1944.

Eddison’s constant rule of composition was that he worked on whatever part of the novel made his imagination sail most confidently; he did not hold himself to a course bearing determined by the plot’s chronology. In early 1944, Eddison decided to work on the end of the novel, and he wrote to Gerald Hayes on 22 February about his intention:

I am getting on with The Mezentian Gate, being now about to write the last five chapters which in the last two weeks I have roughed out on paper in scenario form, or synopsis, or by whatever absurd name it should be called. When they are written there will be in existence at least the head and tail. That is a stage I shall be glad to have reached and passed; not only because there will then be cardinal points fixed, by which to build the body of the book, but also because if I were then to be snuffed out there would remain a publishable fragment able to convey some suggestion of what the finished opus was to have been.

The clause ‘because if I were then to be snuffed out’ is a curious one because it most obviously refers to the threat of the German bombings, but it could also refer to the questionable state of Eddison’s health, a matter that he held in close privacy. In any case, the sentence helps to explain why Eddison, several months later, composed such a meticulously complete synopsis of the middle twenty-six chapters.

Writing steadily over the spring and summer of 1944, Eddison completed the four final chapters and Chapter XXXIV, nearly 31,000 words, in six months. He was especially proud of the climactic chapter, ‘Omega and Alpha in Sestola.’ Eddison told Hamilton that he had spent 290 hours upon the chapter, and that it had cost him more energy than anything he had written previously. By late January 1945, Eddison had completed Chapters XXVIII and XXIX, which concern Fiorinda’s first appearance on the Zimiamvian stage and her ill-fated marriage to Baias. Then Eddison worked extensively on Chapter XXX, which he designed to show Fiorinda’s entrance into society after the death of Baias, and especially to show the responses of the other characters to her and her somewhat tainted reputation. Many of Eddison’s unfinished pieces for the chapter have a light-hearted humorous tone which is refreshing after so much Zimiamvian solemnity. The chapter’s best scene shows Zapheles falling in adoration at Fiorinda’s feet only to become a plaything for her amusement. In Beroald’s words: ‘it is but one more pair of wings at the candle flame: they come and go till they be singed’. Eddison never completed the chapter, and it is the last part of the book that he worked on. It is a sad thing to read the unfinished pieces of this chapter, for they are confidently and sometimes exquisitely written, yet some of them date to within two weeks of his sudden death.

Another sad thing is that just before his death, Eddison was discovering a basis for a new Zimiamvian book. ‘I foresee the 4th beginning to shape itself,’ he wrote to his friend Christopher Sandford in May 1945. ‘I think if it materializes it will really be the fourth – an exception to my habit of writing history backwards.’ But the book would never get its chance, for the end came quickly and unexpectedly on 18 August. Winifred Eddison tells the story to George Hamilton:

I cannot be anything but thankful that he went so quickly. He and I had been sitting outside after tea last Friday, talking most happily. I felt so strongly at the time how happy he seemed. We fed the hens together and those of our neighbours, who are away. At about 6:30 I came in to prepare supper and at 7:00 p.m. gave the usual whistle that all was ready. There was no answer, but often the whistle didn’t carry. On searching for him, I found him lying unconscious and breathing heavily-Jean came almost at once and has been the greatest help and support. The doctor said it was ‘a sudden and complete blackout’ for him. He could have felt nothing and that is what makes me so glad. He never regained consciousness.

The suddenness of the fatal stroke makes me wonder whether it was caused by a gradual period of declining health or by the strenuous work impressed upon Eddison by the war. If his war work brought him to his unfortunate and untimely end, he would not have changed events if he could have. He declared his views on his war service on 24 November 1942, in a letter to an American writer named William Hurd Hillyer:

When the civilized world is agonized by a Ragnarok struggle between good and evil; when everything that can be shaken is shaken, and the only comfort for wise men is in the certitude that the things that cannot be shaken will stand; poets and artists are faced squarely with the question whether they are doing any good producing works of art: whether they had not better put it by and get on with something more useful. That is not a question that can with any honour be evaded. Nor can any man answer it for others.

This philosophically minded man was dutiful and responsible; he placed the interests of his family and his community above his own. Eddison exhausted himself in the garden to ensure that his family had enough to eat. In doing this, one could say, Eddison was doing only what was necessary and what he was obliged to do as the head of the household. True, and yet the ARP work was neither necessary nor obligatory: he volunteered for it, it seems, as an alternative form of service when his doctor forbade his joining the Home Guard. His sense of duty made the service obligatory.

Looking at the whole of his retired years, I wonder whether Eddison took too much upon himself. He viewed his wartime tasks as work that could not be evaded without dishonour. But writing was his real work. He would have written more, and he would have lived less strenuously had there been no national crisis impinging on his retired life. Perhaps he would have lived longer, too. Part of me wants to see him as a victim, but I know that he would not want to be thought of in that way; his Scandinavian heritage was too ingrained in him for that. I think he would rather it be said that he thought of death as did Prince Styrbiorn, the hero of his historical novel Styrbiorn the Strong: when the Earl Strut-Harald predicts that Styrbiorn will live a short life, Styrbiorn replies, ‘I reck not the number of my days, so they be good.’

PAUL EDMUND THOMAS

July 1991

PREFATORY NOTE (#ulink_55382847-5048-5260-b3e8-9ae35dd14cf5)

BY COLIN RÜCKER EDDISON (#ulink_55382847-5048-5260-b3e8-9ae35dd14cf5)

MY brother Eric died on 18 August 1945. He had written the following note in November 1944:

Of this book, The Mezentian Gate, the opening chapters (including the Praeludium) and the final hundred pages or so which form the climax are now completed. Two thirds of it are yet to write. The following ‘Argument with Dates’ summarizes in broad outline the subject matter of these unwritten chapters. The dates are ‘Anno Zayanae Conditae’: from the founding of the city of Zayana.

The book at this stage is thus a full-length portrait in oils of which the face has been painted in but the rest of the picture no more than roughly sketched in charcoal, As such, it has enough unity and finality to stand as something more than a fragment. Indeed it seems to me, even in its present state, to contain my best work.

If through misfortune I were to be prevented from finishing this book, I should wish it to be published as it stands, together with the ‘Argument’ to represent the unwritten parts.

E. R. E.

7th November, 1944

Between November 1943 and August 1945 two further chapters, XXVIII and XXIX, were completed in draft and take their place in the text.

A letter written in January 1945 indicates that in the writing of Books Two to Five my brother might perhaps have ‘unloaded’ some of the detail comprised in the Argument with Dates. In substance, however, there can be no doubt that he would have followed the argument closely.

My brother had it in mind to use a photograph of the El Greco painting of which he writes at the end of his letter of introduction. I am sure that he would have preferred and welcomed the drawing by Keith Henderson which appears as a frontispiece. The photograph has been used, by courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, as a basis for the drawing.

We are deeply grateful to my brother’s old friend Sir George Rostrevor Hamilton for his unstinted help and counsel in the preparation of The Mezentian Gate for publication. We also warmly appreciate the generous assistance given by Sir Francis Meynell in designing the form and typographical layout for the book. The maps were originally prepared by the late Gerald Hayes for the other volumes of the trilogy of which The Mezentian Gate is a part.

COLIN RÜCKER EDDISON

1958

LETTER OF INTRODUCTION (#ulink_4a6b8f47-9a43-5e77-9bb2-2924236ee6a2)

TO MY BROTHER COLIN (#ulink_4a6b8f47-9a43-5e77-9bb2-2924236ee6a2)

DEAR Brother:

Not by design, but because it so developed, my Zimiamvian trilogy has been written backwards. Mistress of Mistresses, the first of these books, deals with the two years beginning ‘ten months after the death, in the fifty-fourth year of his age, in his island fortress of Sestola in Meszria, of the great King Mezentius, tyrant of Fingiswold, Meszria, and Rerek’. A Fish Dinner in Memison, the second book, belongs in its Zimiamvian parts to a period of five weeks ending nearly a year before the King’s death. This third book, The Mezentian Gate, begins twenty years before the King was born, and ends with his death. Each of the three is a drama complete in itself; but, read together (beginning with The Mezentian Gate, and ending with Mistress of Mistresses), they give a consecutive history, covering more than seventy years in a special world devised for Her Lover by Aphrodite, for whom (as the reader must suspend unbelief and suppose) all worlds are made.

The trilogy will, as I now foresee, turn to a tetralogy; and the tetralogy probably then (as an oak puts on girth and height with the years) lead to further growth. For, certain as it is that the treatment of the theme comes short of what I would, the theme itself is inexhaustible. Clearly so, if we sum it in the words of a philosopher who is besides (as few philosophers are) a poet in bent of mind and a master of art, George Santayana: ‘The divine beauty is evident, fugitive, impalpable, and homeless in a world of material fact; yet it is unmistakably individual and sufficient unto itself, and although perhaps soon eclipsed is never really extinguished: for it visits time and belongs to eternity.’ Those words I chanced upon while I was writing the Fish Dinner, and liked the more because they came as a catalyst to crystallize thoughts that had long been in suspension in my mind.

In this world of Zimiamvia, Aphrodite puts on, as though they were dresses, separate and simultaneous incarnations, with a different personality, a different soul, for each dress. As the Duchess of Memison, for example, She walks as it were in Her sleep, humble, innocent, forgetful of Her Olympian home; and in that dress She can (little guessing the extraordinary truth) see and speak with her own Self that, awake and aware and well able to enjoy and use Her divine prerogatives, stands beside Her in the person of her lady of the bedchamber.

A very unearthly character of Zimiamvia lies in the fact that nobody wants to change it. Nobody, that is to say, apart from a few weak natures who fail on their probation and (as, in your belief and mine, all ultimate evil must) put off at last even their illusory semblance of being, and fall away to the limbo of nothingness. Zimiamvia is, in this, like the saga-time; there is no malaise of the soul. In that world, well fitted to their faculties and dispositions, men and women of all estates enjoy beatitude in the Aristotelian sense of

(activity according to their highest virtue). Gabriel Flores, for instance, has no ambition to be Vicar of Rerek: it suffices his lust for power that he serves a master who commands his dog-like devotion.

It may be thought that such dark and predatory personages as the Vicar, or his uncle Lord Emmius Parry, or Emmius’s daughter Rosma, are strangely accommodated in these meads of asphodel where Beauty’s self, in warm actuality of flesh and blood, reigns as Mistress. But the answer surely is (and it is an old answer) that ‘God’s adversaries are some way his owne’. This ownness is easier to accept and credit in an ideal world like Zimiamvia than in our training-ground or testing-place where womanish and fearful mankind, individually so often gallant and lovable, in the mass so foolish and unremarkable, mysteriously inhabit, labouring through bog that takes us to the knees, yet sometimes momentarily giving an eye to the lone splendour of the stars. When lions, eagles, and she-wolves are let loose among such weak sheep as for the most part we be, we rightly, for sake of our continuance, attend rather to their claws, maws, and talons than stay to contemplate their magnificences. We forget, in our necessity lest our flesh become their meat, that they too, ideally and sub specie aeternitatis, have their places (higher or lower in proportion to their integrity and to the mere consciencelessness and purity of their mischief) in the hierarchy of true values. This world of ours, we may reasonably hold, is no place for them, and they no fit citizens for it; but a tedious life, surely, in the heavenly mansions, and small scope for Omnipotence to stretch its powers, were all such great eminent self-pleasuring tyrants to be banned from ‘yonder starry gallery’ and lodged in ‘the cursed dungeon’.

The Mezentian Gate, last in order of composition, is by that very fact first in order of ripeness. It in no respect supersedes or amends the earlier books, but does I think illuminate them. Mistress of Mistresses, leaving unexplored the relations between that other world and our present here and now, led to the writing of the Fish Dinner; which book in turn, at its climax, raised the question whether what took place at that singular supper party may not have had yet vaster and more cosmic reactions, quite overshadowing those affecting the fate of this planet. I was besides, by then, fallen in love with Zimiamvia and my persons; and love has a searching curiosity which can never be wholly satisfied (and well that it cannot, or mankind might die of boredom). Also I wanted to find out how it came that the great King, while still at the height of his powers, met his death in Sestola; and why, so leaving the Three Kingdoms, he left them in a mess. These riddles begot The Mezentian Gate.

With our current distractions, political, social and economic, this story (in common with its predecessors) is as utterly unconcerned as it is with Stock Exchange procedure, the technicalities of aerodynamics, or the Theory of Vectors. Nor is it an allegory. Allegory, if its persons have life, is a prostitution of their personalities, forcing them for an end other than their own. If they have not life, it is but a dressing up of argument in a puppetry of frigid make-believe. To me, the persons are the argument. And for the argument I am not fool enough to claim responsibility; for, stripped to its essentials, it is a great eternal commonplace, beside which, I am sometimes apt to think, nothing else really matters.

The book, then, is a serious book: not a fairy-story, and not a book for babes and sucklings; but (it needs not to tell you, who know my temper) not solemn. For is not Aphrodite

– ‘laughter-loving’? But She is also

– ‘an awful’ Goddess. And She is

– ‘with flickering eyelids’, and

– ‘honey-sweet’; and She is Goddess of Love, which itself is

– ‘Bitter-sweet, an unmanageable Laidly Worm’: as Barganax knows. These attributes are no modern inventions of mine: they stand on evidence of Homer and of Sappho, great poets. And in what great poets tell us about the Gods there is always a vein of truth. There is an aphorism of my learned Doctor Vandermast’s (a particular friend of yours), which he took from Spinoza: Per realitatem et perfectionem idem intelligo: ‘By Reality and Perfection I understand the same thing.’ And Keats says, in a letter: ‘Axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses.’

Fiorinda I met, and studied, more than fifteen years ago: not by any means her entire self, but a good enough shadow to help me to set down, in Mistress of Mistresses and these two later books, the quality and play of her features, her voice, and her bearing. The miniature, a photograph of which appears as frontispiece, belongs to the Hispanic Society of America, New York: it was painted circa 1596 by El Greco, from a sitter who has not, so far as I know, been identified. But I think it was painted also in Memison: early July, A.Z.C. 775, of Fiorinda (aet. 19), in her state, as lady of honour: the first of Barganax’s many portraits of her. A comparison with Mistress of Mistresses (Chapter II especially, and – for the eyes – last paragraph but one in Chapter VIII) shows close correspondence between this El Greco miniature and descriptions of Fiorinda written and published more than ten years before I first became acquainted with it (which was late in 1944): so close as to make me hope the photograph may quicken the reader’s imagination as it does mine. I record here my acknowledgements and thanks to the Hispanic Society of America for generously giving me permission to reproduce the photograph now used, by courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, as a basis for the drawing which appears as a frontispiece.

So here is my book: call it novel if you like; poem if you prefer. Under whatever label—

I limb’d this night-peece and it was my best.

Your loving brother,

E. R. E.

Dark Lane,

Marlborough,

Wiltshire.

PRAELUDIUM (#ulink_c9916380-04be-5064-91fa-5bbb18161ffb)

LESSINGHAM ON THE RAFTSUND (#ulink_c9916380-04be-5064-91fa-5bbb18161ffb)

IT was mid July, and three o’clock in the morning. The sun, which at this time of year in Lofoten never stays more than an hour or two below the horizon, was well up, fingering to gold with the unbelievably slowed deliberation of an Arctic dawn first the two-eared peak itself and then, in a gradual creeping downward, the enormous up-thrusts of precipice that underpin that weight and bulk, of Rulten across the Raftsund. Out of the waters of that sea-strait upon its westerly side the mountains of naked stone stood up like a wall, Rulten and his cubs and, more to the north, the Troldtinder which began now, with the swinging round of the sun, to take the gold in the jags of their violent sky-line. The waters mirrored them as in a floor of smoke-coloured crystal: quiet waters, running still, running deep, and having the shadow of night yet upon them, like something irremeable, like the waters of Styx.

That shadow lingered (even, as the sun drew round, seemed to brood heavier) upon this hither shore, where Digermulen castle, high in the cliffs, faced towards Rulten and the Troldfjord. The castle was of the stone of the crags on whose knees it rested, like-hued, like-framed, in its stretches of blind wall and megalithic gauntnesses of glacis and tower and long outer parapet overhanging the sea. To and fro, the full length of the parapet, a man was walking: as for his body, always in that remaining and untimely thickening dusk of night, yet, whenever he turned at this end and that, looking across the sound to morning.

It would have been a hard guess to tell the age of him. Now and again, under certain effects of the light, deep old age seemed suddenly to glance out of his swift eagly eyes: a thing incongruous with that elasticity of youth which lived in his every movement as he paced, turned, or paused: incongruous with his thick black hair, clipped short but not so short as to hide the curliness of it which goes most with a gay superfluity of vigour of both body and mind that seldom outlasts the prime, and great coal-black beard. Next instant, what had shown as the ravages of the years, would seem but traces of wind and tempest, as in a man customed all his life to open weather at sea or on mountain ridges and all desolate sun-smitten places about the world. He was taller than most tall men: patently an Englishman, yet with that facial angle that belongs to old Greece. There was in him a magnificence not kingly as in ordinary experience that term fits, but deeper in grain, ignoring itself, as common men their natural motions of breathing or heart-beat: some inward integrity emerging in outward shape and action, as when a solitary oak takes the storm, or as the lion walks in grandeur not from study nor as concerned to command eyes, but from ancestral use and because he can no other.

He said, to himself: ‘Checkmate. And by a bunch of pawns. Well, there’s some comfort in that: not to be beaten by men, but the dead weight of the machine. I can rule men: have, all my life ruled them: seen true ends, and had the knack to make them see my ends as their own. Look at them here: a generation bred up in these five-and-twenty years like-minded with me as if I had spit ’em. Liker minded than if they had been sprung from my loins. And now?—

the bright day is done,

And we are for the dark.

What can a few thousand, against millions? Even if the millions are fools. It is the old drift of the world, to drabness and sameness: water, always tending by its very nature to a dead level.’ He folded his arms and stood looking seaward over the parapet. So, perhaps, Leonidas stood for a minute when the Persians began to close in upon the Pass.

Then he turned: at a known step, perhaps: at a known perfume, like the delicate scent of the black magnolia, sharpened with spindrift and sea-foam and wafted on some air far unlike this cool northern breath of the Raftsund. He greeted her with a kind of laugh of the eyes.

‘You slept?’

‘At last, yes. I slept. And you, mon ami?’

‘No. And yet, as good as slept: looking at you, feeding on you, reliving you. Who are you, I wonder, that it is the mere patent of immortality, after such a night, only to gaze upon your dear beauties asleep? And that all wisdom since life came up upon earth, and all the treasure of old time past and of eternity to come, can lie charmed within the curve of each particular hair?’ Then, like the crack of a whip: ‘I shall send them no answer.’

Something moved in her green eyes that was like the light beyond the sound ‘No? What will you do, then?’

‘Nothing. For the first time in my life I am come to this, that there is nothing I can do.’

‘That,’ said she, ‘is the impassable which little men are faced with, every day of their lives. It awaits even the greatest at last. You are above other men in this age of the world as men are above monkeys, and have so acted; but circumstance weighs at last too heavy even for you. You are trapped. In the tiger-hunts in old Java, the tiger has no choice left at last but to leap upon the spears.’

‘I could have told you last night,’ he said ‘(but we were engrossed with things worthier our attention), I’ve everything ready here: for that leap.’ After a pause: ‘They will not move till time’s up: noon tomorrow. After that, with this new Government, bombers no doubt. I have made up my mind to meet them in the air: give them a keepsake to remember me by. I will have you go today. The yacht’s ready. She can take you to England, or wherever you wish. You must take her as a good-bye gift from me: until we meet – at Philippi.’

She made no sign of assent or dissent, only stood still as death beside him, looking across at Rulten. Presently his hand found hers where it hung at her side: lifted it and studied it a minute in silence. It lay warm in his, motionless, relaxed, abandoned, uncommunicative, like a hand asleep. ‘Better this way than the world’s way, the way of that yonder,’ he said, looking now where she looked; ‘which is dying by inches. A pretty irony, when you think of it: lifted out of primaeval seas not a mountain but a ‘considerable protuberance’; then the frosts and the rains, all the infinitely slow, infinitely repeated, influences of innumerable little things, getting to work on it, chiselling it to this perfection of its maturity: better than I could have done it, or Michael Angelo, or Pheidias. And to what end? Not to stay perfect: no, for the chisel that brought it to this will bring it down again, to the degradation of a second childhood. And after that? What matter, after that? Unless indeed, the chisel gets tired of it.’ Looking suddenly in her eyes again: ‘As I am tired of it,’ he said.

‘Of life?’

He laughed. ‘Good heavens, no! Tired of death.’

They walked a turn or two. After a while, she spoke again. ‘I was thinking of Brachiano:

On paine of death, let no man name death to me,

It is a word infinitely terrible—’

‘I cannot remember,’ he said in a detached thoughtful simplicity, ‘ever to have been afraid of death. I can’t honestly remember, for that matter, being actually afraid of anything.’

‘That is true, I am very well certain. But in this you are singular, as in other things besides.’

‘Death, at any rate,’ he said, ‘is nothing: nil, an estate of not-being. Or else, new beginning. Whichever way, what is there to fear?’

‘Unless this, perhaps?—

Save that to dye, I leave my love alone.’

‘The last bait on the Devil’s hook. I’ll not entertain it.’

‘Yet it should be the king of terrors.’

‘I’ll not entertain it,’ he said. ‘I admit, though,’ – they had stopped. She was standing a pace or two away from him, dark against the dawn-light on mountain and tide-way, questionable, maybe as the Sphinx is questionable. As with a faint perfume of dittany afloat in some English garden at evening, the air about her seemed to shudder into images of heat and darkness: up-curved delicate tendrils exhaling an elusive sweetness: milk-smooth petals that disclosed and enfolded a secret heart of night, pantherine, furred in mystery. – ‘I admit this: suppose I could entertain it, that might terrify me.’

‘How can we know?’ she said. ‘What firm assurance have we against that everlasting loneliness?’

‘I will enter into no guesses as to how you may know. For my own part, my assurance rests on direct knowledge of the senses: eye, ear, nostrils, tongue, hand, the ultimate carnal knowing.’

‘As it should rightly be always, I suppose; seeing that, with lovers, the senses are the organs of the spirit. And yet – I am a woman. There is no part in me, no breath, gait, turn, or motion, but flatters your eye with beauty. With my voice, with the mere rustle of my skirt, I can wake you wild musics potent in your mind and blood. I am sweet to smell, sweet to taste. Between my breasts you have in imagination voyaged to Kythera, or even to that herdsman’s hut upon many-fountained Ida where Anchises, by will and ordainment of the Gods, lay (as Homer says) with an immortal Goddess: a mortal, not clearly knowing. But under my skin, what am I? A memento mori too horrible for the slab in a butcher’s shop; or the floor of a slaughter-house; a clockwork of muscle; and sinew, vein and nerve and membrane, shining – blue, grey, scarlet – to all colours of corruption; a sack of offals, to make you stop your nose at it. And underneath (when you have purged away these loathsomeness of the flesh) – the scrannel piteous residue: the stripped bone, grinning, hairless, and sexless, which even the digestions of worms and devouring fire rebel against: the dumb argument that puts to silence all were’s, maybe’s, and might-have-beens.’

His face, listening, was that of a man who holds a wolf by the ears; but motionless: the poise of his head Olympian, a head of Zeus carved in stone. ‘What name did you give when you announced yourself to my servants yesterday evening?’

‘Indeed,’ she answered, ‘I have given so many. Can you remember what name they used to you, announcing my arrival?’

‘The Señorita del Rio Amargo.’

‘Yes. I remember now. It was that.’

‘“Of the Bitter River.” As though you had known my decisions in advance. Perhaps you did?’

‘How could I?’

‘It is my belief,’ he said, ‘that you know more than I know. I think you know too, in advance, my answer to this discourse with which you were just now exploring me as a surgeon explores a wound.’

She shook her head. ‘If I knew your answer before you gave it, that would make it not your answer but mine.’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘you shall be answered. I have lived upon this earth far into the third generation. Through a long life, you have been my book (poison one way, pleasure another), reading in which I have learnt all I know: and this principally, to distinguish in this world’s welter the abiding from the fading, real things from phantoms.’

‘Real things or phantoms? And you can credit seeing, hearing, handling, to resolve you which is which?’

‘So the spirit be on its throne, I can; and answer you so out of your own mouth, madonna. But I grant you, that twirk in the corner of your lips casts all in doubt again and shatters to confusion all answers. I have named you, last night, Goddess, Paphian Aphrodite. Was that a figure of speech? a cheap poetaster’s compliment to his mistress in bed? or was it plain daylight, as I discern it? Come, what do you think? Did I ever call you that before?’

‘Never in so many words,’ she said, very low. ‘But I sometimes scented in you, great man of action you are in the world’s eyes, a strange capacity to incredibilities.’

‘Let me remind you, then, of facts you seem to affect have forgotten. You came to me – once in my youth, once in my middle age – in Verona. In the interval, I lived with you, in our own house of Nether Wastdale, lifted up and down the world, fifteen years, flesh of my heart, heart of my heart. To end that, I saw you dead in the Morgue at Paris: a sight beside which your dissecting-table villainy a few minutes since is innocent nursery prattle. That was fifty years ago, next October. And now you are come again, but in your black dress, as in Verona. For the good-bye.’ She averted her face, not to be seen. ‘This is wild unsizeable talk. Fifty years!’

‘Whether it be good sense or madhouse talk I am likely to know,’ he said, ‘before tomorrow night; or, in the alternative, to know nothing and to be nothing. If that be the alternative, so be it. But I hold it an alternative little worthy to be believed.’

They were walking again, and came to a bench of stone. ‘O, you have your dresses,’ he said, taking his seat beside her. His voice had the notes the deeps and the power of a man’s in the acme of his days. ‘You have your dresses: Red Queen, Queen of Hearts, rosa mundi; here and now, Black Queen of the sweet deep-curled lily-flower, and winged wind-rushing darknesses of hearts’ desires. I envy both. Being myself, to my great inconvenience, two men in a single skin instead of (as should be) one in two. Call them rather two Devils in a bag, when they pull against one another or bite one other. Nor can I ever even incline to take sides with either, without I begin to wish t’other may win.’

‘The fighter and the dreamer,’ she said: ‘the doer, the enjoyer.’ Then, with new under-songs of an appassionate tenderness in her voice: ‘What gift would you have me give you, O my friend, were I in sober truth what you named me? What heaven or Elysium, what persons and shapes, would we choose to live in, beyond the hateful River?’

His gaze rested on her a minute in silence, as if to take a fresh draft of her: the beauty that pierced her dress as the lantern-light the doors of a lantern: the parting of her hair, not crimped but drawn in its native habit of soft lazy waves, as of some unlighted sea, graciously back on either side over the tips of her ears: the windy light in her eyes. ‘This is the old story over again,’ he said. ‘There is but one condition for all the infinity of possible heavens: that you should give me yourself, and a world that is wholly of itself a dress of yours.’

‘This world again, then, that we live in? Is that not mine?’

‘In some ways it is. In many ways. In every respect, up to a point. But damnably, when that point is reached, always and in every respect this world fails of you. Soon as a bud is ready to open, we find the canker has crept in. Is it yours, all of it, even to this? I think it is. Otherwise, why have I sucked the orange of this world all my life with so much satisfaction, savoured it in every caprice of fortune, waded waist-deep in this world’s violences, groped in its clueless labyrinths of darkness, fought it, made treaty with it, played with it, scorned it, pitied it, laughed with it, been fawned on by it and tricked by it and be-laurelled by it; and all with so much zest? And now at last, brought to bay by it; and, even so, constrained by something in my very veins and heart-roots to a kind of love for it? For all that, it is not a world I would have you in again, if I have any finger in the plan. It is no fit habit for you, when not the evening star, unnailed and fetched down from heaven, were fair enough jewel for your neck. If this is, as I am apt to suspect, a world of yours, I cannot wholly commend your handiwork.’

‘Handiwork? Will you think I am the Demiurge: builder of worlds?’

‘I think you are not. But chooser, and giver of worlds: that I am well able to believe. And I think you were in a bad mood when you commissioned this one. The best I can suppose of it is that it may be some good as training-ground for our next. And for our next, I hope you will think of a real one.’

While they talked she had made no sign, except that some scarce discernible relaxing of the poise of her sitting there brought her a little closer. Then in the silence, his right hand palm upwards lightly brushing her knee, her own hand caught it into her lap, and there, compulsive as a brooding bird, pressed it blindly down.

Very still they sat, without speaking, without stirring: ten minutes perhaps. When at length she turned to look at him with eyes which (whether for some trick of light or for some less acceptable but more groundable reason) seemed now to be the eyes of a person not of this earth, his lids were closed as in sleep. Not far otherwise might the Father of Gods and men appear, sleeping between the Worlds.

Suddenly, even while she looked, he had ceased breathing. She moved his hand, softly laying it to rest beside him on the bench. ‘These counterfeit worlds!’ she said. ‘They stick sometimes, like a plaster, past use and past convenience. Wait for me, in that real one, also of Your making, which, in this world here, You but part remembered, I think, and will there no doubt mainly forget this; as I, in my other dress, part remembered and part forgot. For forgetfulness is both a sink for worthless things and a storeroom for those which are good, to renew their morning freshness when, with the secular processions of sleeping and waking, We bring them out as new. And indeed, shall not all things in their turn be forgotten, but the things of You and Me?’

BOOK ONE (#ulink_46a4167e-8e4f-5ab1-a79e-782a9bfb7c81)

I (#ulink_a29ec0f7-598d-5a7f-b7ee-0197fca15475)

FOUNDATIONS IN REREK (#ulink_a29ec0f7-598d-5a7f-b7ee-0197fca15475)

PERTISCUS Parry dwelt in the great moated house beside Thundermere in Latterdale. Mynius Parry, his twin brother, was lord of Laimak. Sidonius Parry, the youngest of them, dwelt at Upmire under the Forn.

To Pertiscus it had long seemed against reason, and a thing not forever to be endured, that not he but his brother Mynius must have Laimak; which, seated upon a rock by strength inexpugnable, had through more than twenty-five generations been to that family the fulcrum of their power, making men regard them, and not lightly undertake anything that ran not with their policy. In those days, as from of old, no private man might live quiet in Rerek, for the envies, counterplottings, and open furies of the great houses, each against each: the house of Parry, sometimes by plain violence, other times using under show of comity and friendship a more mole-like policy, working ever to new handholds, new stances, on the way up towards absolute dominion; while, upon the adverse side, the princely lines of Eldir and Kaima and Bagort in the north laboured by all means, even to the sinking now and then of their mutual jealousies, to defeat these threats to their safeties and very continuance. Discontents in the Zenner marches: emulations among lesser lords, and soldiers of fortune: growing-pains of the free towns, principally in the northern parts: all these were wound by one party and the other to their turn. And always, north and south, wings shadowed these things from the outlands: eagles in the air, whose stoops none might securely foretell: Meszria in the south, and (of nearer menace, because action is of the north but the south apter to love ease and to repose upon its own) the great uneasy power of the King of Fingiswold.

So it was that the Lord Pertiscus Parry, upon the thirty-eighth birthday of him and Mynius, which fell about winter-nights, took at last this way to amend his matter: bade his brother to a birthday feast at Thundermere, and the same night, when men were bemused with wine and Mynius by furious drinking quite bereft of his senses, put him to bed to a bear brought thither on purpose, and left this to work till morning. Himself, up betimes, and making haste with a good guard to Laimak swiftlier than tidings could overtake him, was let in by Mynius’s men unsuspecting; and so, without inconvenience or shedding of blood made himself master of the place. He put it about that it was the Devil had eat his brother’s head off, coming in the likeness of a red bear with wings. Simple men believed it. They that thought they knew better, held their tongues.

After this, Pertiscus Parry took power in Laimak. His wife was a lady from the Zenner; their children were Emmius, Gargarus, Lugia, Lupescus, and Supervius.

Emmius, being come of age, he set in lordship at Sleaby in Susdale. Lugia he gave in marriage to Count Yelen of Leveringay in north Rerek. Gargarus, for his part simple and of small understanding, grew to be a man of such unthrifty lewd and abominable living that he made it not scrupulous to lay hand on men’s daughters and lawful wives, keep them so long as suited the palate of his appetite, then pack them home again. Because of these villainies, to break his gall and in hope to soften the spite of those that had suffered by him, his father forced him to pine and rot for a year in the dungeons under Laimak. But there was no mending of his fault: within a month after his letting out of prison he was killed in a duello with the husband of a lady he had took by force in the highway between Swinedale and Mornagay. Lupescus grew up a very silent man. He lived much shut up from the world at Thundermere.

Of all Pertiscus’s children the youngest, Supervius, was most to his mind, and he kept him still at his side in Laimak.

He kept there also for years, under his hand, his nephew Rasmus Parry, Mynius’s only son. Rasmus had been already full grown to manhood when he had sight of his father’s corpse, headless and its bowels ploughed up and the bear dead of her wounds beside it (for Mynius was a man of huge bodily strength) in that inhospitable guest-chamber at Thundermere; yet these horrid objects so much inflamed his mind that nought would he do thenceforth, day or night, save rail and lament, wishing a curse to his soul, and drink drunk. Pertiscus scorned him for a milksop, but let him be, whether out of pity or for fear lest his taking off might be thought to argue too un-manlike a cruelty. In the end, he found him house and land at Lonewood in Bardardale, and there, no great while afterwards, Rasmus, being in his drunken stupor, fell into a great vat of mead and thus, drowned like a mouse, ended his life-days.

Seventeen years Pertiscus sat secure in Laimak, begraced and belorded. Few loved him. Far fewer were those, how high soever their estate, that stood not in prudent awe of him. He became in his older years monstrously corpulent, out-bellied and bulked like a toad. This men laid to the reproach of his gluttony and gormandizing, which indeed turned at last to his undoing; for, upon a night when he was now in his fifty-sixth year, after a surfeit he had taken of a great haggis garnished with that fish called the sea-grape putrefied in wine, a greasy meat and perilous to man’s body, which yet he affected beyond all other, he fell down upon the table and was suddenly dead. This was in the seven hundred and twenty-first year after the founding of the city of Zayana. In the same year died King Harpagus in Rialmar of Fingiswold, to whom succeeded his son Mardanus; and it was two years before the birth of Mezentius, son of King Mardanus, in Fingiswold.

Supervius was at this time twenty-five years of age: in common esteem a right Parry, favouring his father in cast of feature and frame of mind, but taller and without superfluity of flesh: all hardness and sinew. Save that his ears stood out like two funguses, he was a man fair to look upon: piercing pale eyes set near together, like a gannet’s: red hair, early bald in front: great of jaw, and with a fiery red beard thick and curly, which he oiled and perfumed, reaching to his belt. He was of a most haughty overweeningness of bearing: hard-necked and unswayable in policy, albeit he could look and speak full smoothly: of a sure memory for things misdone against him, but as well too for benefits received. He was held for a just man where his proper interest was not too nearly engaged, and a protector of little men: open-handed, and a great waster in spending: by vulgar repute a lycanthrope: an uneasy friend, undivinable, not always to be trusted; but as unfriend, always to be feared. He took to wife, about this time, his cousin Rhodanthe of Upmire, daughter of Sidonius Parry.

Men judged it a strange thing that Supervius, being that he was the youngest born, should now sit himself down in his father’s seat as though head of that house unquestioned. Prince Keriones of Eldir, who at this time had to wife Mynius’s daughter Morsilla, and had therefore small cause to love Pertiscus and was glad of any disagreeings in that branch of the family, wrote to Emmius to condole his loss, styling him in the superscription Lord of Laimak, as with intent by that to stir up his bile against his young brother that had baulked him of his inheritance. Emmius returned a cold answer, paying no regard to this, save that he dated his letter from Argyanna. The Prince, noting it, smelt in it (what soon became generally opinioned and believed) that Supervius had prudently beforehand hatched up an agreement with his eldest brother about the heirship, and that Emmius’s price for waiving his right to Laimak had been that strong key to the Meszrian marchlands: according to the old Rerek saying:

A brace of buttocks in Argyanna

Can swing the scales upon the Zenner.

This Lord Emmius Parry, six years older than Supervius, was of all that family likest to his mother: handsomer and finelier-moulded of feature than any else of his kindred: lean, loose-limbed, big-boned, black of hair, palish of skin, and melancholic: wanting their fire and bestial itch to action, but not therefore a man with impunity to be plucked by the beard. He was taciturn, with an ordered tongue, not a swearer nor an unreverent user of his mouth: men learned to weigh his words, but none found a lamp to pierce the profoundness of his spirit. He was a shrewd ensearcher of the minds and intents of other men: of a saturnine ironic humour that judged by deed sooner than by speech, not pondering great all that may be estimate great: saw where the factions drew, and kept himself unconcerned. No hovering temporizer, nor one that will strain out a gnat and swallow a camel, neither yet, save upon carefully weighed necessity, a meddler in such designs as can hale men on to bloody stratagems: but a patient long-sighted politician with his mind where (as men judged) his heart was, namely south in Meszria. His wife, the Lady Deïaneira, was Meszrian born, daughter to Mesanges of Daish. He loved her well, and was faithful to her, and had by her two children: Rosma the first-born, at that time a little maid seven winters old, and a son aged four, Hybrastus. Emmius Parry lived, both before at Sleaby and henceforward in Argyanna, in the greatest splendour of any nobleman in Rerek. He was good to artists of all kind, poets, painters, workers in bronze and marble and precious stones, and all manner of learned men, and would have them ever about him and pleasure himself with their works and with their discourse, whereas the most of his kin set not by such things one bean. There was good friendship between him and his brother Supervius so long as they were both alive. Men thought it beyond imagination strange how the Lord Emmius quietly put up his brother’s injuries against him, even to the usurping of his place in Laimak: things which, enterprised by any other man bom, he would have paid home, and with interest.

For a pair of years after Supervius’s taking of heirship, nought befell to mind men of the change. Then the lord of Kessarey died heirless, and Supervius, claiming succession for himself upon some patched-up rotten arguments with more trickery than law in them, when the fruit did not fall immediately into his mouth appeared suddenly with a strength of armed men before the place and began to lay siege to it. They within (masterless, their lord being dead and all affairs in commission), were cowed by the mere name of Parry. After a day or two, they gave over all resistance and yielded up to him Kessarey, tower, town, harbour and all; being the strongest place of a coast-town between Kaima and the Zenner. Thus did he pay himself back somewhat for loss of Argyanna that he had perforce given away to his brother.

Next he drew under him Telia, a strong town in the batable lands where the territories of Kaima marched upon those subject to Prince Keriones: this professedly by free election of a creature of his as captal of Telia, but it raised a wind that blew in Eldir and in Kaima: made those two princes lay heads together. Howsoever, to consort them in one, it needed a solider danger than this of Telia which, after a few months, came to seem no great matter and was as good as forgot until, the next year, the affair of Lailma, being added to it, brought them together in good earnest.

Lailma was then but a small town, as it yet remains, but strongly seated and walled. Caunas has formerly been lord of it, holding it to the interest of Mynius Parry whose daughter Morsilla he had to wife: but some five years before the death of Pertiscus Parry, they of Lailma rose against Caunas and slew him: proclaimed themselves a free city: then, afraid of what they had done, sought protection of Eldir. Keriones made answer, he would protect them as a free commonalty: let them choose them a captain. So all of one accord assembled together and put it to voices, and their voices rested on Keriones; and so, year by year, for eight years. The Lady Morsilla, Caunas’s widow, was shortly after the uproar matched to Prince Keriones; but the son of her and Caunas, Mereus by name, being at Upmire with his great-uncle Sidonius Parry and then about twelve years of age, Pertiscus got into his claws and kept him in Laimak treating him kindly and making much of him, as a young hound that he might someday find a use for. This Mereus, being grown to manhood, Supervius (practising with the electors in Lailma) now at length in the ninth year suborned as competitor of Keriones to the captainship. Faction ran high in the town, and with some blood-letting. In the end, the voices went on the side of Mereus. Thereupon the hubble-bubble began anew, and many light and unstable persons of the Parry faction running together to the signiory forced the door, came riotously into the council chamber, and there encountering three of the prince’s officers, with saucy words and revilings bade them void the chamber; who standing their ground and answering threat for threat, were first jostled, next struck, next overpowered, seized, their breeches torn off, and in that pickle beaten soundly and thrown out of the window.

Keriones, upon news of this outrage, sent speedy word to his neighbour princes, Alvard of Kaima and Kresander of Bagort. The three of them, after council taken in Eldir, sent envoys to both Laimak and Argyanna, to make known that they counted the election void because of intermeddling by paid agents of Supervius Parry (acting, the princes doubted not, beyond their commission). In measured terms the envoys rehearsed the facts, and prayed the Lords Emmius and Supervius, for keeping of the peace, to join with the princes in sending of sufficient soldiers into Lailma to secure the holding of new elections soberly, so as folk might quietly and without fear of duress exercise their choice of a captain.