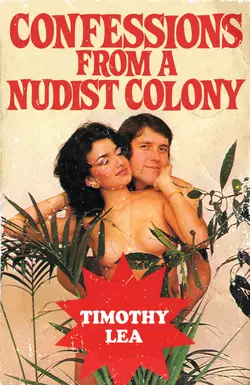

Confessions from a Nudist Colony

Timothy Lea

If you go down to the woods today, you’re in for a BIG surprise…Another romping tale from Timothy Lea’s CONFESSIONS series, available for the first time in eBook.Available for the first time on eBook, the classic sex comedies from the 70s.Sid Noggett and Timothy Lea are getting back to nature. That means playing Blind Man’s Buff in, well, the buff, and foraging with Dimity Dropwort, a fair farmer’s lass who likes viewing nature from a horizontal position… You’d best avert your eyes!Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS FROM A HOLIDAY CAMPCONFESSIONS OF AN ICE CREAM MANCONFESSIONS FROM THE CLINKand many more!

Publisher’s Note (#ulink_8727cd41-b9ca-5f61-8686-561d74100d7d)

The Confessions series of novels were written in the 1970s and some of the content may not be as politically correct as we might expect of material written today. We have, however, published these ebook editions without any changes to preserve the integrity of the original books. These are word for word how they first appeared.

CONFESSIONS FROM A NUDIST COLONY

Timothy Lea

CONTENTS

Publisher’s Note (#u4568a87d-261f-57bc-8545-564b2e023ff8)

Title Page (#u19f74a54-b8b8-50ab-8dcb-5f343aa0a2f2)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also Available in the Confessions Series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Timothy Lea (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#u4074e919-cd27-5560-a108-082bf6362d33)

‘Wonderful, isn’t it?’ says Sid. We have just come out of The Highwayman and he is gazing across the rolling expanse of couples trying to have it off in the middle of Clapham Common.

‘The first bit of sun always brings them out,’ I say.

‘What are you on about?’ says Sid, irritably. ‘I was referring to spring unfurling her mantle of green, not that bloke tucking his shirt down the front of that bird’s skirt. I don’t know how they have the gall to carry on like that in front of everyone. That geezer with the brown demob suit and a pork pie hat ought to get amongst them with his sharpened stick.’

‘The game warden?’ I say. ‘He’s too busy stopping people stoning the crocuses. Anyway, what’s got into you, Sid? They used to have to send a bloke round after you with a bucket of sand to fill in the dents. You’re the last person to start casting asparagus.’

But Sid is not listening to me. He is still under the spell of spring and four pints of mild and bitter. ‘Just grab a niff of that breeze,’ he drools. ‘You’d never think that had to blow over Clapham Junction to get here, would you?’

‘To say nothing of ducking round Battersea Power Station,’ I agree with him. ‘Yes, Sid, it’s a rare treat for the hooter, even after what you’ve just done.’

Sid takes a few brisk steps towards the pond where the middle-aged wankers crash their model boats into each other, and throws his arms wide. ‘Not just the hooter,’ he says. ‘All the senses rejoice. Look at the little buds on that chestnut tree. Each one glistening under its coating of sooty smog. That’s nature in blooming riot. Will our children ever see anything like this? That’s what I ask myself.’

‘I hope not,’ I say, ripping my eyes away from the bloke who is clearly connected by more than mental ties to his lady love. ‘They don’t care, some of them, do they?’

‘All over the grass,’ says Sid in disgust. ‘I don’t know how they can bring themselves to do it. You’d think they’d just want to lie back and clock nature weaving her magic spell, wouldn’t you?’

‘Surely that’s what gets them going,’ I say. ‘I mean, look at that pigeon up there. He’s not playing leapfrog with the other one. That’s nature saying “get at it!”’

‘Pigeons are always like that,’ says Sid distastefully. ‘You remember what they did to the seat of my bike? I only left it outside Reg Perkins’ loft for a couple of minutes, too.’

‘Yes, very embarrassing,’ I say. ‘Incidentally, the loose cover has just come back from the cleaners. I think Mum was hoping you might cough up a bit towards the bill.’

‘What about my trousers?’ says Sid. ‘It’s not my fault Reg Perkins can’t house-train his bleeding pigeons. She ought to get on to him about it!’

‘Just a thought, Sid,’ I say, deciding quickly that there is little chance of making headway in that direction. ‘Certainly is a lovely day.’

‘Definitely!’ Sid takes a deep breath and winces. ‘When it’s like this you couldn’t consider living anywhere else, could you?’

‘Er – yes,’ I say. Sid’s words sound a bit strange coming from a bloke who was quite happy bumming round the Mediterranean on SS Tern until an American admiral tried to run him down with his ship – he was unhappy because he had just seen Sid boarding another vessel with his wife and a couple of camels. (See Confessions from a Luxury Liner for surprising details.)

‘Finest country in the world,’ waxes Sid. ‘Don’t ever let anyone else tell you different. We may have our problems but when the sun is shining – shit! Can’t people control their animals? Bleeding notices everywhere and nobody takes a dicky bird. The only way they’d do any good is if you put them low enough to scrape your foot on. I’d like to see some geezer’s horrible hound doing his business on the public thoroughfare. I’d follow him home and drop one in his front garden.’

‘Highly sophisticated, Sid,’ I venture. ‘I hate to think what kind of aggro that could spark off. What do you fancy doing now? We could mosey down and collect our sausage.’ (Sausage roll: dole = National Assistance).

‘Nah,’ says Sid, finishing scraping his shoe and dropping the stick into the bin reserved for icecream wrappers. ‘It’s always a bit crowded after the boozers have shut. Let’s leave it to thin out. I hate to look as if I need the money.’

‘You just take it to save hurting anyone’s feelings, don’t you, Sid?’

‘And to keep it in the country,’ says Sid. ‘I reckon it’s the least I can do. All those Micks and Pakis would have it back to Bangladesh in no time – or any other part of Ireland you care to mention. That brings back memories, doesn’t it?’

‘You mean the couple having it off under the caravan?’ I say.

‘Nah,’ says Sid. ‘Don’t you ever think about anything else? I was referring to the fair. I remember coming up here as a kid. I never had money to spend on anything but I used to watch the roundabouts whipping round and listen to the records. I thought it was great. It was better than the telly in those days.’

‘There wasn’t any telly in those days, was there?’ I say. ‘I thought you had to listen to the radio with a pair of earphones.’

‘You’ve no sense of neuralgia, have you?’ says Sid. ‘I suppose you’re too young. It’s when you start slowing up a bit that you begin to remember.’

‘Blimey!’ I say. ‘If you can hang on a minute, I’ll nip into one of these caravans and see if anyone’s got a violin. What’s come over you? Nature, childhood. I’ve never known you like this.’

‘It’s a kind of menopause,’ says Sid ‘or I suppose you should say ‘manopause’. A time of life when you take stock of where you are and where you’re going. Have you noticed anything unusual about me lately?’

‘You fastened your cardigan to one of your fly buttons on Tuesday,’ I say, trying to remember. ‘Or was it Wednesday?’

‘I don’t mean that!’ snaps Sid. ‘I haven’t had an idea what we’re going to do next, have I? Normally, new career opportunities are bombarding my nut like flies round a steaming horse turd. But at the moment – nothing. I’m worried, I don’t mind admitting it.’

‘You mustn’t get yourself in a state,’ I comfort. ‘Maybe we should venture beyond those screens at the Labour more often. They might have something right up our street.’

‘I don’t want to work on my own doorstep,’ says Sid. ‘Swanning round the Med gave me a taste for the wide open spaces. That’s why I’m so contented up here. Look at the light on the sail of that yacht. The sun gives it an almost translucent quality – like when you’re sitting on your mum’s karsi.’

I take it that Sid is referring to the way the sun shines through the cracks in the door and focuses on the cut up bits of the TV Times in the bog paper holder but I don’t really like to ask. ‘I could certainly do with some bread,’ I say.

‘What for?’ says Sid. ‘What good’s bread?’

His words strike me round the face with the force of an ice-cold halibut freshly wrenched from the Arctic Ocean.

‘What good is bread?’ I repeat. ‘Everything we’ve ever done has been based on your desire to stash away a few bob.’

‘I was young then,’ says Sid. ‘No more than a gullible boy with distorted values. I used to think that if money couldn’t buy happiness at least you could live miserably in comfort, but I don’t believe that any more. Look at Paul Getty.’

‘That’s not him, is it?’ I say. ‘Behind the thermos with the blonde bird? She’s a bit young for him, isn’t–?’

‘No!’ says Sid, cuttingly. ‘I meant examine the situation of Paul Getty and ask yourself if he has found true happiness. I’ve realised that money isn’t the answer, Timmo. There’s much more to life than sipping your Bovril out of a gold-plated mug in front of Match of the Day in colour.’

‘And you don’t think Paul Getty has realised that?’

‘I do think he’s realised that,’ says Sid emphatically. ‘But he’s realised it too late. That’s why he’s always looking so blooming miserable. I don’t intend to make the same mistake.’

‘Thank gawd!’ I say. ‘You’d have been unbearable as the richest man in the world.’

Sid ignores what some might have considered to be a trace of sarcasm in my voice. ‘The only thing, is that having rejected riches, I don’t know where to turn. I’m in a state of limbo. Timbo – I mean, Timmo.’

‘Well,’ I say. ‘As it so happens, fate has directed us to the right spot. Look what it says on that caravan. “Madame Necroma reveals all: £1”. Your future laid bare for a couple of bars, Sid. Can’t be bad.’

I am not really serious but Sid’s mince pies light up. ‘Yeah!’ he says. ‘She should know, shouldn’t she? They have a gift, these people. Lend us a quid.’

‘Do me a favour!’ I say. ‘She can make do with the gifts she’s already got. I’ve already bought most of the booze you drunk in that rubber. Anyway, I’m very happy with you in a state of limbo. It doesn’t cost me money.’

‘There you go again,’ says Sid. ‘Money. It’s your BO and end all, isn’t it? You can’t think about anything else. You’re so inflexible. If it wasn’t for my ability to mellow and develop as a human being you’d be exactly where you were when I first met you.’

‘Don’t make it sound too tempting,’ I say.

‘What I always have difficulty in making you understand,’ says Sid, ‘is that you have a wonderful opportunity to learn from my experience in life. I go through things so that you don’t have to.’

‘Like my fiancée,’ I say.

‘You’re not still worrying about that,’ says Sid. ‘It was so long ago – and anyway, you were never properly engaged.’

‘Wouldn’t have made any difference if we’d been getting married,’ I say wearily. ‘You’d have been trying to feel her up while you handed me the ring.’

‘No need to be coarse,’ says Sid. ‘That’s all behind us now – all that sexual foolishness. Now I’m a more mature human being I can see what Mary Whitehouse and Lord Longford are up to.’

‘You’ve heard rumours, have you?’ I say, beginning to get interested. ‘Don’t tell me that nice Antonia Fraser’s daddy has done something untoward.’

‘Of course not!’ says Sid. ‘I didn’t mean “up to” in the slap and tickle sense. I was referring to their stand against the corrupting influence of books like the ones your Dad keeps in the hallstand.’

‘He doesn’t any more,’ I say. ‘They’re in the cistern.’

‘Blimey, I wondered why he was in there for so long. Dirty old sod! How did you find out?’

‘I pulled the chain one day and nothing happened–’

‘You have to pull it quickly and then give it one long pull,’ interrupts Sid.

‘Do you mind?’ I tell him. ‘It is my home. I ought to know how to use the karsi. Why don’t you belt up and let me finish?’ I pause for a censorial moment – good word that, isn’t it? – and then continue. ‘When I climbed up on the seat I found that a couple of mags had slipped underneath the ballcock.’

‘How very appropriate,’ says Sid. ‘They must have been a bit soggy.’

‘They were,’ I say. ‘But it didn’t spoil the effect. The photos on the reverse side of the page showed through so you had one bird on top of the other.’

‘You had that anyway,’ says Sid. ‘Oh dear. How sad it all is. Your Dad has grown old without achieving maturity. I’d feel sorry for him if he wasn’t such a miserable old git. Lend us a quid.’

I had hoped to talk Sid out of his insane impulse to help Madame Necroma towards a new set of frilly curtains for her caravan but once he gets an idea into his crust it can be very hard to budge. We are still arguing when one of the curtains is pulled aside and a bird with a beauty spot and a lot of makeup snatches a gander at us. She looks a bit ruffled, as does the geezer who appears when the caravan door opens. His knees are practically the first thing to hit the top step and he staggers down the rest of them like he has both feet through the slit of his Y-fronts.

‘Find it all right, did you?’ asks Sid.

The bloke looks not a little taken aback. ‘What do you mean?’ he says suspiciously.

‘You know,’ says Sid, jerking his head towards the window. ‘Does she know her stuff?’

The bloke gives a little shiver and pulls his mac around him. ‘Unbelievable,’ he says.

Sid turns to me. ‘There you are! Come on, don’t be a berk. Maybe she’ll take something off for the two of us.’

‘She won’t take anything off,’ says the bloke. ‘I asked her specially.’

‘Well, we’ll have a go anyway,’ says Sid. ‘Come on, Timmo! Don’t you want to know what the future holds in store?’

The bloke gives Sid another funny look and hurries away muttering. ‘Nice chap,’ says Sid. ‘He clearly found it a moving experience. Did you notice that glazed look in his eyes?’

‘I was concentrating on the way his knees bashed together,’ I say. ‘Do you really want to go through with this, Sid?’

‘Definitely,’ says my diabolical brother-in-law. And he bounds up the steps like a jack rabbit.

No sooner is his Oliver Twist poised in front of the Rory than it whips open and the bird in the window nearly clocks him one with one of her enormous earrings. They are so big that you could sit a parrot on them – provided you did not mind running the risk of it doing its business in your earhole. She is now wearing a head scarf tied tightly round her nut and her generous knockers heave beneath an embroidered shawl.

‘Madame Necroma?’ says Sid. ‘Good afternoon, madame. My friend and I would like to avail ourselves of your service.’

‘Both of you?’ says the bird.

‘Exactly,’ says Sid. ‘You have perceived my meaning to the T. We were wondering if there was a possibility of you making a reduction in our case?’

‘I’ll reduce anything you show me,’ says Madame Necroma. ‘Come in, boys. You don’t want to hang about. There’s narks everywhere. It’s getting impossible to turn over a couple of bob without finding a copper.’

She closes the door behind us and we take a gander round the inside of the caravan. ‘Blimey,’ says Sid. ‘I never seen one with a double bed in it before.’

‘It folds away to make a couple of work surfaces,’ says Madame. ‘Now, what can I do to accommodate you? Both together? Or, one at a time? Or one watching? – it’s amazing how popular watching has become lately. I suppose it’s the telly?’

‘What’s the cheapest?’ I ask quickly.

‘One at a time, flat rate,’ says Madame. ‘A quid each.’

‘You go ahead,’ I say to Sid. ‘I’ll give it a miss. I’m not all that keen.’

‘Charming!’ says Madame Necroma.

‘Don’t take it to heart,’ says Sid. ‘It’s a question of bees, not doubting your professional integrity. We’re both the same sign anyway. Scorpio: brooding, sensual, possessive–’

‘Skint!’ says Madame Necroma.

‘I’ll wait for you outside,’ I say to Sid.

‘Right,’ says Sid. ‘Don’t fret. Whatever I learn will be to our mutual advantage. This might be the turning point, Timmo. It could be the best quid you’ve ever spent.’

I am still trying to tell him that I only lent him the money when Madame Necroma pushes me down the steps. She certainly seems in a hurry to get on with it. I suppose Sid’s stars could be on the point of moving into a different quarter. I believe it is a very precise science.

When I get outside I have a quick shufti round the fair and then take a butcher’s at the couples on the common. I soon give this up because the other people who are clocking them are such a disgusting lot. It’s like pornography. There is nothing wrong with it except the kind of person it attracts. It makes you feel dirty to be associated with them.

About ten minutes have gone by and I reckon that Madame Necroma must have finished with Sid. She did not look the type to hang about. I wander back to the caravan and am slightly surprised that there is no sign of Clapham’s answer to Paul Newman. Nor is there any sound from the caravan. Madame must still be gazing intently into her crystal ball. Best to leave them at it rather than interrupt the seance, or whatever it is. Sid would be furious if I spoilt his big moment.

I have just started counting the china alsatians in the caravan windows when I turn and see a female copper surveying me with what would pass for interest in any other bird. I don’t know what it is but I immediately start feeling guilty. My palms get hot and sweaty and when I move it is as if I expected a jemmy to drop out of my trouser leg. I turn away but I am conscious that the bird is still watching me. Perhaps she thinks I am casing the caravans prior to a spot of B. and E.

‘Psssst!’ Do my senses deceive me or is it her making that noise? I turn and she waggles a finger at me and retires behind a trailer. What can she want? Perhaps it is a new way of arresting people. You nip round the corner after PC Niceparts and a blooming great bule bashes you over the nut with his truncheon. Still, what have I got to worry about? I haven’t done anything. I take a deep breath and trip round the side of the trailer – some twit has left an electric cable stretched across the grass. The Bluebird is waiting for me and, I must say, she could take me in charge any day of the week. Neat as a guardsman’s sewing kit and eyes like warm toffee. She has a delicate dust of freckles on her face and her eyelashes flop about like they have just been washed and she can’t do a thing with them. All in all, she looks as if she would find it difficult to straighten a seam in her stocking, let alone arrest anyone.

‘CID?’ she murmurs. She is nodding over my shoulder when she speaks and I am so busy clocking the plus features that for some reason I think she is referring to Sid – we often call him El Cid, anyway.

‘Er – yes,’ I say, not wanting to give too much away. You never know what Sid has been up to.

‘Balham,’ she breathes. ‘Sorry I’m late for our Romeo Victor. Has there been much action?’

I don’t answer at once because I am trying to work out who this Romeo Victor bloke is. Perhaps I misheard her and she said Romany Victor. That would make more sense in our present surroundings. ‘Look,’ I say. ‘I think there’s been a mistake.’

‘You were expecting a man.’ To my surprise her lip starts to tremble. It is a nice lip, as is its plump little friend underneath, and a wave of sympathy runs through my Y-fronts.

‘Only Sid,’ I say.

‘I don’t know Sid,’ she says. ‘I’ve only just joined the station.’

‘Balham,’ I say. ‘Oh yes, you said.’

‘I won’t let you down,’ says the bird. ‘I may only be a woman but inside me beats the heart of a man.’

‘Blimey!’ I say. ‘I bet that made the Police Gazette. It’s wonderful what surgeons can do these days, isn’t it?’

For a moment, I think the bird is going to burst into tears.

‘You’re making fun of me!’ she accuses. ‘I was referring to Elizabeth the First’s words at Tilbury.’

‘Oh, them,’ I say. ‘Yes, well, you should have made yourself clear. I missed that episode when it was on the telly. What precisely are you trying to say to me?’

‘I’m trying to say that you can rely on me,’ she says. ‘I won’t let you down. I don’t care what they’re doing in there. I won’t be shocked. Just say the word and I’ll be right with you – oh!’ While I am wondering what the hell she is talking about she suddenly whips a pair of handcuffs from under her skirt and slaps them on my wrists. God knows where she keeps her truncheon.

‘Don’t look surprised!’ she hisses. ‘Somebody’s watching us from the window. I’ll pretend to arrest you.’

I glance up at the window of Madame Necroma’s caravan and am not a little taken aback to see Sid blinking down at me. He looks strangely flushed and dishevelled. Maybe it is the surprise of seeing me being led off by one of the female fuzz. I raise my manacled mitts along with my eyebrows and his boat race is joined by Madame Necroma’s. She is looking a bit on the heated side and I can’t help wondering what they have been doing. Surely it is beyond the realms of possibility that kapok karate has been indulged in? Before I can indulge the horrible thought to excess, the female copper has led me round the corner and is feeling in the pocket of her tunic.

‘Sorry about that,’ she says, sounding like Barbara Cartland watching one of her pekes relieve itself against your ankle. ‘I thought they might think it was a bit fishy if they saw us hanging about outside the caravan – oh no!’

Her face goes all horror-struck like Harold Wilson looking at the latest trade figures and I am swift to realise that something is wrong. ‘Look,’ I say. ‘I don’t want to sound unsympathetic and I always used to enjoy Z Cars, but what is going on around here?’

‘I’ve lost the key to the handcuffs,’ she says. ‘Oh gosh. You’re going to think I’m an awful goose.’

‘At the very least,’ I say. ‘Look, you could get arrested for this. Everybody’s looking at me.’

‘Come over to the car,’ she says. ‘Perhaps the driver will have a spare one. I am most awfully sorry about this.’

‘So you should be!’ I hiss. Honestly, you feel like sticking your tongue out at Jack Warner, don’t you? No wonder the country is in a mess. I wonder this kid was able to cut out the application form without doing herself a serious injury. She must have needed guidance to follow the dotted lines round the advertisement. If she was not easy on the eye-balls I might be thinking about writing to my MP.

‘What’s he done, miss?’ says one of the kids who is clustering around us.

‘Child murder!’ I tell him. ‘Hop it, you horrible little basket!’

‘Looks a villain,’ says another God forbid. ‘Do you want any help, miss?’

‘No thanks,’ I say. ‘I’m going quietly. Which is more than you will be if you don’t scarper sharpish!’ I make a threatening lunge and they drop back half a dozen paces.

There is a police car parked under a tree and the bloke at the wheel puts down his copy of Six Hundred Ways To Thump Someone And Leave No Trace and leaps out hungrily. ‘Got the ponce, have you?’ he says looking me up and down hungrily. ‘Wait till we get you back to the station, matey.’

‘No!’ says little Miss Blue Serge, blushing. ‘He’s our contact. I locked him up by mistake.’

‘Oh, gawd, Millie!’ says the fuzz. ‘I thought you’d finished for the day when you arrested that store detective for shoplifting. Unlock him quick!’

‘I’ve lost my key,’ says the bird. Her lip has started trembling again and it is clear that she is on the verge of tears.

‘Oh no!’ The rozzer bashes his fist against the side of his nut so hard that his hat nearly falls off.

‘Haven’t you got one?’ says Millie.

‘Course I haven’t got one!’ The fuzz looks about him desperately. ‘Who’s keeping the caravan under surveillance?’

‘Nobody,’ says Millie. ‘I’d better go–’

‘No you don’t! You’ve done enough damage for one day,’ says the fuzz. ‘You stay here. I’ll go.’

‘What about me?’ I say.

‘You can’t go,’ says the copper. ‘Not with those handcuffs on. You get in the car with WPC Marjoribanks. I’ll be back as soon as I can.’

‘Thanks a lot,’ I say, not without a trace of sarcasm.

‘Sorry about this,’ says the male fuzz, considerately opening the car door for me. ‘These combined ops are always a bit of a disaster, aren’t they? Get out of it! !’ His last remark is delivered to the pack of kids round the car as he turns and strides purposefully towards the caravans. The kids follow him.

WPC Marjoribanks slides along the back seat beside me. She has nice little knees and I can’t help clocking the curve of her thighs underneath the blue serge skirt. ‘Alone at last,’ I say.

She smiles nervously. ‘I don’t have to say it again, do I?’

‘Please don’t,’ I say. ‘It doesn’t help very much. Haven’t you got a hacksaw tucked away somewhere?’

She does not answer but starts running her hands over the front of her body. ‘I must have a hole,’ she says.

‘It’s not beyond the realms of possibility,’ I say suavely. ‘Perhaps you’d better have a look for it. I shouldn’t think anything would have much chance of dropping out of that lot.’

I am clocking the front of her tight tunic when I speak and it is true that she would be pushed to smuggle a thin stamp hinge in the space not taken up by knocker.

‘I suppose there’s always a chance,’ she says.

The same thought occurs to me as I watch her fingers delving in the breast pocket of her tunic and a wave of naughtiness sweeps over the maximum stress area of my jeans.

‘Any luck?’ I say.

‘Oh dear,’ she says. ‘There is a hole. The lining’s gone.’

Not surprising with that lot chafing against it, I think to myself. ‘Perhaps it’s slipped down inside,’ I say, jerking my manacled mitts to indicate that some kind of action needs to be taken.

WPC Marjoribanks nods and starts to undo her tunic. She is wearing a plum red half cut bra under her blue shirt and I suck in my breath appreciatively. ‘That’s not government issue, is it?’ I say.

‘What, the shirt?’ she says.

‘The bra,’ I say. ‘I can’t help noticing it when I look. It’s nice.’

‘Oh, no, it’s not – I mean, it’s not police issue. Frankly – if it doesn’t sound like heresy – I’m not all that keen on the uniform. In fact–’ her lip starts to tremble again ‘– I’m not all that keen on the Force.’

‘I don’t like force either,’ I say. ‘There’s too much of it. People talk about sex and violence like they are the same thing but I only see the–’

‘I mean the Police Force,’ she says. ‘Frankly I don’t think I’m cut out to be a copper. That probably sounds terrible to you. How long have you been a flat foot?’

‘Well, I’ve always had a bit of trouble with my arches,’ I say. ‘Mum made me wear my sister’s old sandals when I was a kid and–’

‘A policeman,’ she says. ‘How long have you been with the CID?’

This time I twig what she says: the CID, not the SID. She has obviously mistaken me for a plain clothes copper. I wonder if it would be wise to disillusion her? Especially in our present situation. ‘Not very long,’ I say. I give a light laugh and wait for her to ask me why.

‘What are you laughing at?’ she says.

‘I was just thinking,’ I say. ‘If I wanted to make a pass at you I’d have a problem, wouldn’t I?’ I hold out my wrists and give her the famous Lea slow burn. It is all good clean fun and she smiles gamely.

‘I sometimes wonder if that’s why I joined,’ she says sadly.

‘What do you mean?’ I say.

‘I used to be very free and easy,’ she says. ‘I remember how worried my mother was. I think I thought that if I joined the police force it would be the next best thing to becoming a nun. I’d be protected from myself. The sanctity of the uniform would keep me on the straight and narrow.’

You could nip on my straight and narrow any day of the week, I think to myself. I nod understandingly and take one of her hands in both of mine – I don’t have any alternative with the handcuffs on. ‘You don’t want to go against your true nature,’ I say. ‘Any luck with that key?’

She retrieves her hand and runs it along the hem of her skirt. ‘Nope. It must have dropped out.’

‘Couldn’t have slipped inside your shirt?’ I drop my tethered mitts on her Ned Kelly and have a little feel. It is even more sexy with the bracelets on. Percy certainly thinks so anyway. He bounces up like a rubber pigeon shit. ‘No. There’s nothing there – except you.’ The minute I lay hands on her she stiffens like something else I have just mentioned and it is clear that the pressure of my sensitive looks and fingers is not altogether repugnant.

‘This is awful,’ she says. ‘What would anyone say if they could see?’

‘There’s nobody around to see,’ I say. ‘They’ve all gone off with your mate. Let’s make sure you’re not concealing anything.’

I lower my nut in time with my voice and gently brush my mouth against hers. I wouldn’t exactly say that she abandons herself to my lips but she does not bust the back window jerking her head away.

‘Are you married?’ she says. ‘All the worst ones at the station are married.’

‘I’m not surprised you have problems,’ I say. ‘No, I’m not married.’

‘You shouldn’t be doing that,’ she says.

‘I’m just trying to keep the circulation running through my wrists,’ I say. ‘These handcuffs are blooming tight.’

‘Isn’t there anything else you can feel?’ she says.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘I’ll have to find out.’ Before she can say anything, I drop my mitts to her knee and twist my body round so that I can slide them underneath her skirt.

‘Ooh!’ she says.

‘The steel’s a bit cold, is it?’ I say – consideration for birds’ feelings has always been one of my strong points.

‘Not only that,’ she says. ‘Your cheek’s pretty cool too! I’ve never worked with any one like you.’

‘We could become famous in the anals of crime,’ I say.

‘I think you mean annals,’ she says. ‘Though when you do that with your hands I’m not sure.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘These seats slope down a bit steep.’ I give her another chance to taste the nectar of my lips and this time our cakeholes melt together and I feel her long lashes brushing against my cheek like imprisoned butterflies – poetry, isn’t it? Oh, all right, please yourself. Only trying to extend my range. And, talking about extensions – yes, Percy is rearing roofwards like he is bent on turning my lap into an imitation of a tent being erected. She has gorgeous lips, this bird. They are sort of soft and tacky so that they form themselves to the shape of your cakehole and then cling on like clams. What a bleeding shame that my mitts are manacled. I really feel the urge to mould this bird-sized bule to the stressed steel that is the Lea rib cage.

‘Stop! You must–’ she squawks.

‘Careful,’ I say. ‘Anything you say will be taken down and used to wipe the condensation off the inside of the windows.’ I have already managed to check that her grumble is no stranger to the velvet gong-belter and without further ado I give her knicks a sponsored trip to kneesville.

‘Stop!’ she squeaks. ‘This is terribly naughty. Supposing we have to make a sprint for it?’

‘Make a splint for it?’ I say. ‘There’s no danger of that I can assure you. Clock this.’

‘No!’ she squeals as I seize my opportunity to reveal Britain’s latest space probe financed entirely by pubic subscriptions. ‘I was referring to our raid on the vice ring. We may be called into action at any moment.’ She gazes into my lap and I see her mind grappling with the problem of what use I can be with my hands manacled and an enormous hard on. I suppose I could always try to batter down the door of a caravan if the worst came to the worst.

‘Get on my lap,’ I say. ‘Go on. You know you want to.’ If she doesn’t, I want it enough for both of us. By the cringe! You could paint my nob tartan and call it Throb Roy.

‘Oh, you’re terrible!’ To my relief she bends forward and helps her knicks over her ankles. ‘Are they all like you in the CID?’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘You want to ask for a transfer.’ I raise my arms above my head and she takes a quick shufti out of the window and scrambles across my knees. They are steaming up fast – I mean, the windows not my knees – and it is probably just as well that a discreet veil should be drawn over the proceedings.

‘I could be discharged for this,’ she pants.

‘Likewise,’ I say working my khyber forward to the edge of the seat. ‘Mind how you – ah!’

She tucks my hampton away like your mum bunging a pair of freshly washed socks into a bottom drawer and it is clear that she is no stranger to parking inside the car.

‘I had a boyfriend with a midget,’ she says.

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘Still, they say that size isn’t everything.’

‘An MG Midget,’ she says. ‘It was very cramped.’

‘Of course,’ I say, getting her drift. ‘This is spacious, isn’t it?’ I slip my wrists over her head and shoulders and hug her to me so that the handcuffs press into the small of her back. Honestly, if you want to get into the police this is the only way. The experience could only be improved if she took her hat off but you don’t like to say anything, do you? Not at a moment like this. It might spoil the magic.

‘Ooooh!’ she gasps. ‘I never realised that pounding the beat could be such fun.’

‘It’s not bad, is it?’ I say. ‘Oooh!’ One of the problems of not being able to use my hands is that I have no control over any of my safety valves. Millie the Fuzz is strictly in the driving seat and with her dishing out the pelvic aggro the time to blast off can be measured in seconds. I try to think of Ted Heath’s organ to take my mind off what the copper bottom is doing to me but it is no good. Wisps of hair are hanging down in front of her boat race and she is biting her lip. I hate to see a woman doing a man’s work so I tilt my head forward and bite her lip for her. Not only bite it but suck it and send my tongue in to check that there has been no serious damage. This clearly goes down a treat and Millie joggles around so much that she hops off my hampton. ‘Damn!’ Boy! If all escaped prisoners were recaptured so quickly you would never hear that they had got out in the first place. WPC Marjoribanks gets my dick back on duty in a vulgar fraction of a second and I drive my feet down against the floor of the car. God knows what is happening outside. All the windows are totally steamed up.

‘Awwwwwweeeeee!’ Millie lets out a squeak and then cements herself to my cakehole. Her body has stopped juddering up and down but a long tremor ripples through it and her toes press against the carpet. I can feel myself teetering on the brink and I jerk my fife upwards until the chava lava runs wild through my quivering thighs and I feel like an electric blanket having it off with a cake mixer. It is a very affecting experience.

‘Right, let’s have you – blimey!’ The speaker is Millie’s mate who has just wrenched open the back door. He looks harassed and surprised, in that order. ‘Millie! You’re supposed to be on the job.’

‘Would you like to rephrase that statement?’ I say.

‘It was bad enough with that bloke in the charge room,’ says the male fuzz. ‘You were only supposed to be taking him a cup of tea.’

‘I was only trying to soften him up,’ protests Millie. ‘Why must you keep bringing up my past?’

‘Time to move on is it, chief?’ I say. ‘Don’t worry about leaving me. I’ll be all right.’ It has occurred to my shrewd brain that the sooner the two coppers slope off the better. What I had with Millie was very beautiful but it could not last. It was just a flash in the pants really. If I arrived home with a female fuzz Dad would have a heart attack – on second thoughts –

‘You’re a disgrace to the uniform,’ says the male copper. ‘Come, Marjoribanks. Button your tunic and shove your knickers down the back of the seat with the rest of them. There’s work to be done.’ He turns back to me. ‘You’d better wait here.’

‘Have no fear, squire,’ I tell him. ‘I’m not going anywhere.’

I am blooming nearly right, too. Have you ever tried pulling up a pair of trousers with handcuffs on? – no! not on the trousers. Why would anyone want to handcuff a pair of trousers? Wake up! This isn’t exactly highbrow reading but you are supposed to have a certain amount of nous. Now, where was I? Oh yes. Standing beside this police car with my bum hanging out of my jeans. I can’t make any progress inside the vehicle and it is only when I straighten up that I begin to get somewhere – like nearly arrested again. I feel such a berk giving little jumps in the air and trying to pull my trousers up at the same moment. A couple of old ladies give me a very nasty look and though I can’t lip read I reckon they are looking around for a keeper. Ungrateful old bags! You’d think they would be glad of a bit of excitement at their age, wouldn’t you?

In the end I manage to tuck my fife away and I am ready to scarper. My shirt is hanging out at the back but I can’t do anything about that with the handcuffs on and nobody is going to draw any conclusions. I mean, it is often like that when you come out of the karsi, isn’t it?

I take a few steps along the road and then remember Sid. Is he still nattering to Madame Necroma or will he have come out and wondered where I am? I had better slip back and have a discreet dekko. Millie and her mate seemed interested in the lady so I had better step warily.

I approach the fair from a different angle and carefully pick my way through the caravans. The fair is now in full swing and the music is grinding out above the hum of the generators. I come round a corner and focus on Madame Necroma’s caravan just as the door opens and the good lady appears at the top of the steps. She is looking decidedly dishevelled and unhappy and pulling a coat round her shoulders. Behind her appears Millie looking embarrassed and I sink back into the shadows. The driver of the police car is the last to leave and he looks round behind him before closing the door. Where is Sid?

‘You’ve got nothing on me!’ says Madame Necroma. ‘Bleeding fuzz! I’ll have you for this.’ She turns on Millie. ‘You’ll have the curse for seven years!’

Before I can work out quite what she means by this statement, the trio disappear round a caravan. How very strange. I can only imagine that Sid has emerged and sloped off to his pad in trendy Vauxhall. He was never the patient type. But hist, what ist? The caravan seems to be trembling. Maybe I had better take a butcher’s. I keep a tight grip on the front of my round the houses and shuffle across the bruised grass littered with fag packets. Up the steps and I try the door. It opens. Inside, it looks just as it did when I last saw it. There is a bowl of Japanese fighting fish but they can’t be belting each other hard enough to set up the vibration that is running through the caravan. I look down at the crumpled bed and – wait a minute! There is only half a bed compared with what there used to be. I switch my gaze to the side of the caravan and see a piece of material I recognise. It is a fragment of Sid’s lumber jacket – we call it that because it is so diabolical that nobody knows how he could have lumbered himself with it. It is protruding from the door of a cupboard. The door of a cupboard that is shuddering as if someone is pressing against it from the inside. Could it be that –? No! It seems impossible – but yet – stranger things have happened to Sidney Noggett.

I grab hold of the handle in the wall and pull. Nothing happens so I pull with both hands and my trousers fall down. Hardly have they touched the floor than the missing half of Madame Necroma’s bed swings down to carpet level. On it sprawls the bright pink body of a naked man lying amongst a pile of discarded clothing and crumpled Tarot cards. His face looks like a chimpanzee’s bum after it has slid down a helter skelter without a mat.

‘Blimey!’ I say. ‘Are you all right, Sid?’

Sid does not answer me but looks round the caravan. ‘Don’t say she’s gone!’ he says. ‘We were just getting to the interesting part.’

CHAPTER TWO (#u4074e919-cd27-5560-a108-082bf6362d33)

‘I can’t believe that she was a nail,’ says Sid.

‘Stands to reason,’ I say. ‘That’s why the fuzz had the caravan under surveillance. I bet they’re pumping her down at the station at this very minute.’

Sid winces and then shakes his hand sadly. ‘I thought she had something,’ he says.

‘I wouldn’t be surprised,’ I say, ‘You’d better have a dunk with the Dettol. Use one of the egg cups if you can get your –’

‘I didn’t mean that!’ says Sid. ‘Where’s your romantic streak? I was referring to our instantaneous report.’

‘You mean rapport,’ I say. ‘A report is a bang – still, I suppose, when you come to think of it –’

‘Sometimes you meet someone and it’s as if you’ve known them all your life,’ muses Sid. ‘Making love seemed as natural as the couple of quid I gave her.’

‘I thought you didn’t have any money?’ I say.

‘I found I had another quid on me,’ says Sid. ‘I reckon it would have worked, too.’

‘What would have worked?’ I say.

‘She said that she would be able to get nearer to the reality that was me if we made love.’

‘And did she?’ I ask.

‘I don’t know,’ says Sid. ‘There was this bang on the door and “wump!” She presses a button and half the bed with me on it whips into the wall.’

‘So you got nothing out of her?’ I say.

‘I wouldn’t say that,’ says Sid. ‘She was completely at one with me about the environment. She had this feeling that our heritage was very precious and that we would squander it at our peril.’

‘That’s nice,’ I say.

‘And she resolved my uncertainty about the future,’ says Sid. ‘With her help I think I’ve found the answer.’ He leans back and taps his nail file against the end of his finger.

‘Go on,’ I say. I am referring to Sid’s effort to cut through the handcuffs with Mum’s nail file but he is making indifferent progress and is clearly more interested in his latest crack-pot scheme.

‘You might well cock your lug holes,’ he says. ‘This little number represents everything I feel like doing at the moment. A return to nature and a life free from stress and strain. I can almost hear the rooks crowing.’

‘Cocks crow,’ I say. ‘Rooks caw. What is it, Sid? Put me out of my misery.’

‘A camping site by the seaside,’ says Sid. ‘What could be simpler?’

‘You mean caravans?’ I ask.

‘Caravans, tents, anything. All you need is a bit of water and somewhere for them to have a Tom Tit and clean their Teds. A field will do. It’s a doddle to look after, and all the time you’ve got the sky as a ceiling above your head, You wake to the sound of birdsong. You’re in the middle of people who are enjoying themselves. And the moment was never riper. With this once great country of ours temporarily in diarrhoea straits, more and more families are taking holidays at home, discovering the joys of their own countryside.’

‘Where are you thinking of doing this?’ I ask.

Sid rubs his hands together. ‘Funny you should say that. When it came to a site I really fell on my feet.’

‘They look as if something fell on them,’ I say – somebody once described Sid as comatose and hammer toes.

‘Don’t take the piss,’ says Sid. ‘You’re going the right way to get a button down hooter when you go on like that. Just ask intelligent questions and you might learn something.’

‘Which one of Madame Necroma’s relations owns a field near the sea?’ I ask.

‘Her aunt,’ says Sid. ‘Wait a minute! How did you know she had a relation who owned a field?’

‘I’ve got mystic powers,’ I say. ‘I can foretell every time you are going to be conned. How much did you pay for this place?’

‘I haven’t paid anything yet,’ says Sid. ‘I’m not a fool! I’m not going to buy it without seeing it. It might be totally unsuitable. Really, Timmo, you do get up my bracket when you imply that I’m some kind of Charlie when it comes to sussing out job opportunities.’

He is still fuming when Dad comes in. I am a bit choked because I had not wished to be caught in a situation which might alarm my sensitive parent. ‘What have you two skiving ’arstards been doing?’ he says as I thrust my arms out of sight beneath the table.

‘Nothing,’ I say automatically.

‘I can believe that,’ says Dad. ‘Now, I’m going to say two words that should strike terror into your hearts: hard work.’

‘Why? Do you want us to translate them for you?’ says Sid.

Dad is clearly feeling righteous after putting in one of his irregular days at the lost property office and does not warm to Sid’s merry quip. ‘Bleeding disgrace!’ he snarls. ‘A working man does an honest day’s labour and he has to put up with two of his family behaving like bloody kids. Haven’t you got anything better to do than hop about in sacks?’

‘Ah – yes,’ says Sid. ‘Sacks. Well, we’re trying to get fit, aren’t we?’

In fact, what happened is a bit more complicated than that. The fuzz take most of Sid’s clothes with them when they leave the caravan and when Madame Necroma’s old man comes in and finds a naked Sid trying to pull up the trousers of a bloke wearing handcuffs he gets the wrong idea. You can’t blame him really. I mean, we live in disturbing times when what went for our grandfathers does not even make us think about coming. When he throws us down the steps of the caravan we are in a bit of a quandary and it is just as well that there is this pile of sacks lying behind the coconut shy. We slip two on sharpish and hop off home. Probably the most knackering experience I have ever undergone, especially coming after Millie – not that I did come after Millie. I am pretty certain that we came at the same time. Anyway, it helped to disguise Sid’s naughty parts and the fact that I was wearing handcuffs.

‘I’ll tell you how to get fit,’ says Dad. ‘Do some bleeding work! The country can’t afford to support grasshoppers any more.’

‘If it can support you, it can support anybody,’ says Sid. ‘Grasshoppers, arse hoppers, you name it!’

‘Hello, dear,’ says Mum, coming in with a tray of tannic poisoning – or tea as she calls it. ‘Did you get your certificate all right?’

‘Oh!’ says Sid. ‘Been down to Doctor Khan, have we? How long did he give you this time?’

‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about!’ says Dad. ‘He’s useless if you don’t wear a turban.’

‘Don’t be like that,’ says Sid. ‘That curry powder did wonders with your warts.’

‘And you know who owns the supermarket where I had to buy it?’ complains Dad. ‘Only his blooming brother-in-law. I remember when you used to get your stuff at a chemist. He told Mrs Kedge to wear a lentil poultice and it was leaking out of her knickers all down the high street.’

‘Walter!’ Mum jerks up the spout of the tea pot in protest.

‘Well, it’s true. It’s no good trying to draw a veil over these things. It’s like this business of having to pay for your medical certificate. It’s profiteering off the sick and needy.’

‘So you’ve been down the library all day?’ accuses Sid. ‘Queueing up with the dossers to have a crack at the page three nude in the Sun.’

‘Some swine tore it out!’ says Dad. ‘That’s nice, isn’t it? Taxpayers’ money and all. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was one of Khan’s lot. They like white women.’

‘Well, that’s only fair,’ says Sid. ‘I mean, you like black women, don’t you? I remember how choked you were when you thought those African birds were going to have to cover up their knockers on the telly.’

‘Sidney!’ says Mum.

‘Nearly turned him against the monarchy, it did,’ says Sid. ‘He couldn’t make up his mind whether to write to Buckingham Palace or Bernard Delfont. In the end he chose Bernard Delfont because he was more influential.’

‘It was the artistic licence I was worried about,’ says Dad.

‘You ought to be more worried about the TV licence,’ says Mum. ‘We’ve had three reminders and you still haven’t done anything.’

‘What have you got there?’ asks Dad. Like a berk, I have raised my hands to grab the tea and Dad has clocked my wrists.

‘He’s got his cufflinks tangled,’ says Sid. ‘Nice, aren’t they? A bit on the large side but handsome.’

‘It’s nothing to be alarmed about,’ I say. ‘This bird thought I was something else – I mean someone else.’

‘Picked you out in an identity parade, did she?’ says Dad. ‘Don’t worry, my son. They’ll never make it stick. What did you do? Nick her handbag. Where is it?’

‘I didn’t nick anything,’ I say.

‘You don’t have to lie to me, son,’ says Dad. ‘I’m your father. I’ll stick by you. We may have our ups and downs but when the chips are down we Leas stick together.’

‘Look –’ says Sid.

‘Shut up!’ says Dad. ‘You led him into this, I suppose? Made him the catspaw for your evil designs. Played on his simple nature.’

‘What do you mean simple?’ I say.

‘Your father’s right, dear,’ says Mum. ‘Don’t let them put words into your mouth. Say you never touched the girl.’

‘I didn’t touch the girl,’ I say. ‘I mean, not like that I didn’t.’

‘Of course, it could go badly with him,’ says Dad. ‘There’s his criminal record to be taken into consideration.’

‘Don’t be daft!’ I say. ‘The only criminal record I’ve got is “The Laughing Policeman”.’

‘He laughs in the teeth of danger!’ says Sid. ‘Makes you proud, doesn’t it? Shall I start piling the furniture against the door? How long do you think we’ll be able to hold out? Better nip out and get a few cans of beans before they get round here.’

‘Shut up, Sid!’ I say. ‘You’re not funny. Haven’t we got anything stronger than this nail file, Dad?’

‘Of course!’ says he from whose loins I sprung with understandable haste. ‘Is that the best he could do for you, my son? Hang on a minute, I’ll get my blow torch.’

‘I’ll go quietly!’ I scream, leaping to the window.

‘Now see what you’ve done,’ says Sid. ‘You’ve inflamed his persecution mania. Why don’t you calm down and start baking him a cake with a file in it?’

‘Because, if his mother made it he’d never be able to bite through to the file,’ says Dad.

‘Walter!’ Mum is understandably upset. ‘How could you? Haven’t I made a nice home for you and the kiddies? Why do you have to say a thing like that? If you don’t like my cooking, you know what you can do.’

‘Yeah. Go on gobbling down the bicarbonate of soda like I do at the moment. Don’t make a scene for Gawd’s sake. There’s more important things to worry about.’

At this moment, fraught with unpleasantness and overhung by a thin veil of menace, the doorbell rings.

‘Who’s that?’ says Mum.

Sid takes a dekko through the lace curtain. ‘Blimey!’ he says. ‘It’s the fuzz!’

‘Don’t take the piss,’ I say, ‘Let me have a – oh no!’ Standing on the doorstep and tucking thoughtfully at his helmet strap is an enormous copper.

‘Right!’ says Dad. ‘I’ll handle this. You get out the back and pretend you’re pushing the lawnmower down to the shelter. I don’t want the neighbours to notice anything.’

‘They’ll notice you haven’t got a lawn,’ says Sid.

‘Shut up!’ says Dad.

‘Dad,’ I say. ‘I don’t think–’

‘I know you don’t,’ says Dad. ‘That’s why I have to do it for you. Now, get out there and stop arguing.’

‘Your father knows best,’ says Mum. ‘Stay in the shed till we come for you. Check there’s nobody round the back, Sid.’ When they go on like that you really feel that you have done something and I begin to wonder if my spot of in and out with Millie was against the law in more senses than one.

‘Right,’ says Dad. ‘Here we go.’

‘Don’t antagonise them, Walter,’ calls Mum.

‘You can rely on me,’ says Dad.

‘There’s nobody round the back,’ says Sid. ‘Come on, Bogart!’ He pushes me out of the back door as I hear Dad opening the front.

The lawmower Dad was talking about is another piece he has ‘saved’ from the lost property office where he is supposed to work. The only piece of grass in the back yard is growing between its rusty blades and the roller stops going round after two yards. I abandon it, not caring whether the neighbours are watching or not, and go and sit in the corrugated iron shelter which Dad kept from the last war and which now holds most of his world famous collection of gas masks. There is a large wooden wireless with a lot of fretwork on the front of it, a tattered copy of a magazine called John Bull and a Players fag packet with a bearded matelot as part of the design. This is where Dad must have repulsed Hitler. I wonder how he is doing with the fuzz? I am reading about how some geezer called Alvar Liddell planned his rock garden when Sid sticks his head round the door.

‘Well,’ he says. ‘They’ve gone.’

‘Oh good,’ I say. ‘Mum and Dad all right?’

‘It’s them that’s gone!’ says Sid. ‘Blimey, your old man didn’t half ask for it. The copper had only come round to tell him that the reflector on his bike had dropped out. Your Dad had his helmet off seconds after he opened the door. Screaming about a police state at the top of his voice, he was. Then your Mum waded in. She’s strong, isn’t she?’

‘When she gets worked up,’ I say. ‘Oh my Gawd. What did she do?’

‘Socked the copper round the mug with that wire basket of earth that used to have flowers in it. They were like wild animals. I don’t know what would have happened if the police car hadn’t gone past. It took three blokes to get them through the doors.’

‘What a diabolical mix-up,’ I say. ‘Poor old Dad. He was only trying to do his best, wasn’t he? It’s quite touching really.’

‘Yes,’ says Sid. ‘Blood is thicker than water and your old man is thicker than both. Don’t worry. You can make it up to him when we get the camping site organised. A nice little holiday by the sea is what they both need. It’ll set them up a treat.’

It occurs to me that for once in his life Sid is right. Mum and Dad do deserve some sort of perk after their brave but misguided attempt to save me from the nick. I only hope that Little Crumbling will be up their street.

‘It looks nice,’ says Sid as we study my old school atlas and have a cup of Rosie prior to nipping down the station and rescuing Mum and Dad – we find a file in the shelter that gets the cuffs off. ‘Little Crumbling, just next to Great Crumbling. You don’t know it, Timmo, do you? You were down that way once.’

Sid is referring to my experience as a Driving Instructor at Cromingham, emergent jewel of North Norfolk. (Shortly to become an epic movie, folks!)

‘I don’t remember it, Sid,’ I say. ‘Still, I didn’t get around much.’

‘Huh,’ says Sid. ‘You were in the back seat shafting the customers, weren’t you? Well, you can forget about that here. There’s going to be no hanky wanky on my site.’

‘I should hope not!’ I say. ‘Hanky panky would be distasteful enough. What are you planning to do, Sid?’

‘We’ll take the car down and spend a couple of days getting the lay of the land. Apparently a Mrs Pigerty lives on the site, but being of a nomadic disposition she could easily be prepared to part with it for a few quid.’

‘She’s a real gyppo, is she, Sid?’

Sid’s expression registers that he has taken exception to my remark. ‘A Romany, please,’ he says. ‘Steeped in ancient laws and crafts. They’re a noble people with their own language, you know. Just because they’re partial to baked hedgehog for Sunday lunch there’s no need to snoot your cock at them.’

‘No disrespect intended,’ I say. ‘I’ve often thought how pleasant it would be wandering over the breast of the down with the reins twitching between my fingers. Faithful Dobbin snatching at a wild rose as we wade fetlock-deep through verdant pastureland. The sun bouncing off the brightly painted shell of the caravan, the blackened cooking pot swinging lazily beside my earhole. The sweet smell of newly mown hay wafting—’

‘All right! All right!’ shouts Sid. ‘Blimey! Are you after an Arts Council grant or something?’

‘Just trying to get in the mood,’ I say. ‘Honeysuckle twisting round the porch and all that.’

‘Don’t start again,’ pleads Sid. ‘We’ll go and collect your Mum and Dad and set off tomorrow. Should take us about three hours, I reckon.’

In fact it is not easy to get Mum and Dad away from the rozzers. Not because they don’t want to let them go, but because Dad barricades himself in his cell and refuses to come out. As we come through the door we hear him shouting about a ‘fast to the death!’

‘How long’s he been on hunger strike?’ I ask.

‘He started just after he had his tea and biscuits,’ says the bloke behind the desk. ‘You his son, are you? Any history of mental disease in the family?’

‘We had a cousin who became a copper,’ I say.

‘Oh yes, highly whimsical,’ says the bule, slamming his book shut. ‘Listen, funny man. If you don’t get your father out of here in ten minutes, I’ll arrest the whole bleeding lot of you!’

‘Where’s my Mum?’ I say.

‘She’s in with your Dad,’ says the bule.

‘That’s nice,’ says Sid. ‘Family solidarity. Refused to be separated, did they?’

The copper looks a bit embarrassed. ‘They couldn’t be separated,’ he says. He turns round and shouts through a door behind him. ‘Millie! Have you found the keys to those blooming handcuffs, yet?’

It is pissing with rain most of the way up to the Norfolk coast but I don’t allow my spirits to flag. A couple of days out of the Smoke with Sid footing the bills is not to be sniffed at and I wonder where he has it in mind for us to stay, I hope we don’t have to share the same bedroom. You always get a few funny glances and one of the waiters rubbing his knee against you when he ladles out the brown windsor.

‘I’m looking forward to a bit of grub,’ I say, trying to raise the subject discreetly.

‘There should be some chocolate in the glove compartment,’ says Sid. ‘That’s if Jason hasn’t eaten it.’

‘I’m not quite certain whether he has or not,’ I say, examining the stomach-turning mess sticking to the 1955 AA Book.

‘Don’t throw it out of the window,’ says Sid. ‘It’s perfectly eatable once it’s firmed up again. You just want to make sure you don’t get a bit of silver paper against your fillings.’

‘I see there’s a hotel at Great Crumbling,’ I say. ‘Got a couple of rosettes and a lift for invalid chairs.’

‘Yes,’ says Sid. ‘We should be turning off about here. Do you notice how the air has changed?’

‘I think they must be spraying that field,’ I say.

‘I didn’t mean that!’ says Sid. ‘I was referring to the fact that it’s fresh. No smoke, no diesel fumes. We’re going to become new men out here. You know how healthy people look when they come back from their holidays? We’re going to be like that all the time.’

‘They’re skint when they come back from their holidays, too,’ I say.

Sid waves his arms into the air and nearly drives into a field of sugar beet. ‘There you go again. Money! That’s all you bleeding think about. Why don’t you put it behind you and look at the skyline?’

‘I’m sorry, Sid,’ I say. ‘I’ll probably feel better when we’ve checked in at the hotel.’ I wait hopefully but Sid tightens his grip on the wheel and gazes through the windscreen with a new sense of purpose.

‘Did you see that signpost?’ he says. ‘Little Crumbling two and a half miles. It was two miles at the signpost before that. You can tell we’re in the country.’

‘I think I’ll have a bath,’ I say. ‘Then a pot of tea in my room. And maybe a few rounds of hot buttered toast.’

Sid shoves on the anchors. ‘That sounds handy,’ he says.

‘Oh good,’ I say. ‘Maybe I’ll have a few teacakes as well.’

‘I meant that,’ says Sid.

I follow his nod and tilt my head to read a lop-sided sign which says ‘Bitter Vetch Farm. Visitors taken in. No travellers’. Beyond the sign is a muddy track leading to a cluster of dilapidated barns surrounding a building with a moulting thatched roof.

‘I don’t think they still do it,’ I say. ‘It looks deserted.’

‘It can’t be,’ says Sid. ‘There’s smoke coming from the roof.’

‘Maybe it’s on fire?’ I say hopefully.

‘Looks very authentic to me,’ says Sid. ‘You’ll get your food straight off the land there. It was just what you were talking about.’

‘Should be cheap as well,’ I say.

‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ says Sid.

‘No, of course not,’ I say. ‘I wonder you didn’t bring a sleeping bag.’

Sid’s eyes narrow thoughtfully and I wish I had kept my mouth shut. ‘You could stretch out in the back underneath the tiger skin rug,’ he says. ‘Mind your feet on the upholstery and don’t try and pee out of the window.’

‘Sounds very tempting, Sid.’ I say. ‘But I’ll give it a miss if you don’t mind.’

The farmyard has half a dozen bedraggled chickens picking their way round it and if their condition is an example of the fare available at Bitter Vetch Farm it is difficult to see why they should want to hang around, let alone us. Sid however does not seem to notice that they look like long-necked canaries and knocks boldly on the door. There is a moment’s pause and the door is opened by a comfortable Mum-type lady with flour all over her hands. These she wipes on the sheep which is lying on the kitchen table.

‘Good afternoon, madam,’ says Sid briskly. ‘I believe you take people in?’

The woman’s face hardens. ‘If you’m from the Milk Marketing Board you can take your long snouts off our farm! The water in them churns came through the roof. My Dan would never knowingly cheat anyone. He ain’t got the sense.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/timothy-lea/confessions-from-a-nudist-colony/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Timothy Lea

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Эротические романы

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: If you go down to the woods today, you’re in for a BIG surprise…Another romping tale from Timothy Lea’s CONFESSIONS series, available for the first time in eBook.Available for the first time on eBook, the classic sex comedies from the 70s.Sid Noggett and Timothy Lea are getting back to nature. That means playing Blind Man’s Buff in, well, the buff, and foraging with Dimity Dropwort, a fair farmer’s lass who likes viewing nature from a horizontal position… You’d best avert your eyes!Also Available in the Confessions… series:CONFESSIONS FROM A HOLIDAY CAMPCONFESSIONS OF AN ICE CREAM MANCONFESSIONS FROM THE CLINKand many more!