The Rasp

Philip MacDonald

Tony Medawar

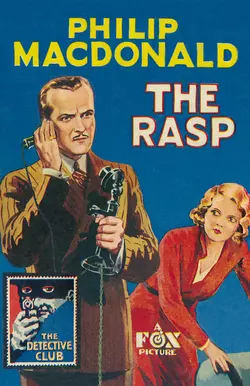

A victim is bludgeoned to death with a woodworker’s rasp in this first case for the famed gentleman detective Anthony Gethryn - the latest in a new series of classic detective novels from the vaults of HarperCollins.Ex-Secret Service agent Anthony Gethryn is killing time working for a newspaper when he is sent to cover the murder of Cabinet minister John Hoode, bludgeoned to death in his country home with a wood-rasp. Gethryn is convinced that the prime suspect, Hoode’s secretary Alan Deacon, is innocent, but to prove it he must convince the police that not everyone else has a cast-iron alibi for the time of the murder.This Detective Story Club classic is introduced by crime fiction expert and writer Tony Medawar, who investigates the forgotten career of one of the Golden Age’s finest detective story writers.

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1924

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd 1932

Copyright © Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1924

Introduction © Tony Medawar 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1932, 2015

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008148119

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780008148126

Version: 2015-10-20

Contents

Cover (#u9fcec753-cb08-536e-b8ac-fcb1010fff30)

Title Page (#u68dc6e1b-0c04-5f2f-82d0-3072e12b75a5)

Copyright (#u1c91d3ab-537e-50d4-aafe-f9565f98ab37)

Introduction (#uf5d634d0-1b7a-50a7-9d01-13790e5510eb)

Chapter I: TOLLING THE BELL (#u87327d60-304b-5b0a-88a3-99941a0f1a7d)

Chapter II: ANTHONY GETHRYN (#u397560d7-af9f-5776-952e-7717e8489590)

Chapter III: COCK ROBIN’S HOUSE (#u9e992304-619f-552b-8a6e-b02edee2a93d)

Chapter IV: THE STUDY (#u00b8eed9-1022-54c2-81f2-ffbbd3e478a6)

Chapter V: THE LADY OF THE SANDAL (#u4f42edcc-61e1-529b-8a5a-3ff81d80278e)

Chapter VI: THE SECRETARY AND THE SISTER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII: THE PREJUDICED DETECTIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII: THE INEFFICIENCY OF MARGARET (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX: THE INQUEST (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X: BIRDS OF THE AIR (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI: THE BOW AND ARROW (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII: EXHIBITS (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII: IRONS IN THE FIRE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV: HAY-FEVER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV: ANTHONY’S BUSY DAY (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI: REVELATION AND THE SPARROW (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII: BY ‘THE OWL’S’ COMMISSIONER (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII: ENTER FAIRY GODMOTHER (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

PHILIP MACDONALD was born in London on 5 November 1900. Writing was in his blood. His paternal grandfather was the Scottish novelist and poet George MacDonald and he was a direct descendant of the MacDonalds who were massacred in Glencoe in 1692. MacDonald’s parents were Constance Robertson, an actress, and Ronald MacDonald, a playwright and novelist. The MacDonalds lived in Chelsea before moving to Twickenham, where Philip attended St Paul’s between 1914 and 1915. His publishers later stated that, on leaving school, he ‘enlisted as a trooper in a famous cavalry regiment, and saw service in Mesopotamia’, now Iraq. While full details have not yet been established, his experiences led to the novel Patrol (1927), which was filmed in 1929 and again as The Lost Patrol in 1934 by director John Ford. MacDonald wrote the script for both films, and there are also echoes of Patrol in his script for another film Sahara (1943).

Other than juvenilia, Philip MacDonald’s serious writing career began with a brace of Buchanesque thrillers, which he co-authored with his father. In the first, Ambrotox and Limping Dick (1920), a new drug ‘Ambrotox’ is stolen from a country house and an heiress is kidnapped. The second, The Spandau Quid (1923), is notable for the many small details that prefigure MacDonald’s most famous novel, The List of Adrian Messenger (1959). The Spandau Quid has a frenetic pace and a confusing plot involving smuggled gold, a sunken U-boat and ‘Germans, Sinn Feiners and Bolsheviks’. Both books feature Superintendent Finucane of the Criminal Investigation Department of Scotland Yard, but the policeman is drawn so sketchily that he cannot be considered a series detective.

No doubt keen to capitalise on the burgeoning popularity of detective fiction, MacDonald decided to try his hand at what would come to be known as whodunits. His first attempt, The Rasp, was first published ninety years ago (August 1924) and forms the debut of MacDonald’s best-known creation, Colonel Anthony Ruthven Gethryn. The Rasp was widely praised and Gethryn would go on to appear in another eleven detective stories which maintain a generally high standard. They included ingenious murderers (The Choice, 1931), well-realised settings (The Crime Conductor, 1931, set in London’s theatre quarter) and novel concepts (Persons Unknown, also 1931, later published as The Maze, in which the reader and Gethryn are presented with precisely the same information in the form of evidence presented at an inquest).

It is likely that MacDonald saw Gethryn as a romanticised version of himself and, as an amateur sleuth of independent means, MacDonald’s detective has much in common with Dorothy L. Sayers’ rather better-known creation, Lord Peter Wimsey. Born approximately fifteen years earlier than MacDonald, Gethryn—whose unusual middle name is pronounced ‘rivven’—is the son of a Spanish mother and a ‘hunting country gentleman’ as a father. ‘No ordinary child’, Gethryn excelled at school and at Trinity College, Oxford, where he studied History and Classics. After University he travelled extensively before returning home to write poetry and a single, reasonably successful novel before being appointed as private secretary to a Government Minister. On the outbreak of war, Gethryn enlisted as a private in an infantry regiment but a year later he was invalided out and, with the help of his Uncle Charles, became a member of the British Secret Service. By 1919, Gethryn had attained the rank of Colonel and been decorated several times. When Uncle Charles died, he left Gethryn a substantial annual income, equivalent to £400,000 in today’s money. Gethryn promptly settled into a house in Stukeley Gardens, a fictional street in Knightsbridge, London, and resigned himself to a life of leisure from which he quickly tired. In need of distraction, he joined an old University friend to become the co-proprietor of a magazine, and it is in this capacity that the reader discovers him at the outset of The Rasp, ‘tall…with a dark, sardonic sort of face and a very odd pair of eyes”.

MacDonald did not only write about Gethryn. In the 1920s and 30s he penned several other novels and some very good non-series detective stories, including two of the three titles published under the pen name of Martin Porlock: Mystery at Friar’s Pardon (1931) features an outrageously simple solution to a baffling ‘impossible crime’, and X v. Rex (1933) is one of the earliest crime novels to feature a serial killer. Almost all of his books were warmly praised, though some critics noted an increasing tendency to structure his books as if they were a treatment for a film. In fact, MacDonald’s first script was an adaptation of his own novel, Patrol, and the second, Raise the Roof (1930), is generally recognised as the first British film musical.

In 1931, after marrying the writer Florence Ruth Howard, Philip MacDonald moved to Hollywood to focus on writing for the screen rather than the page. His third full script was an adaptation of The Rasp (1932), co-written with another crime writer, J. Jefferson Farjeon. Directed by Michael Powell, The Rasp starred Claude Horton as Gethryn, and was well-received by critics and audiences, but sadly no copies are now known to survive and the film is considered lost. As well as adapting his own work such as Rynox (1932) for films, MacDonald produced many original film scripts throughout the 1930s and 40s, including several for the very popular Charlie Chan series based on the novels by John P. Marquand. Working sometimes with other writers, MacDonald also adapted the work of writers, such as Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1930) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher (1945); he also wrote the script for two versions of Love from a Stranger (1937 and 1945), adapting Frank Vosper’s stage play, which was itself a heavily reworked version of a play by Agatha Christie, The Stranger, based on her own short story ‘Philomel Cottage’.

Although Philip MacDonald focused on screenplays for the cinema and television during the 1940s, 50s and 60s, he also wrote a small number of novels. These included The Sword and the Net (1941), a well-regarded Second World War thriller published under the by-line ‘Warren Stuart’, and Forbidden Planet (1956), the novelisation of the cult science fiction film of the same title. And after a solitary Gethryn short story, ‘The Wood-for-Trees’ (1947), 1959 saw the publication of the last and—in the opinion of many critics—the best of the Gethryn series, The List of Adrian Messenger. In this thrilling novel, Gethryn identifies the ruthless mind behind a series of seemingly accidental deaths. John Huston’s enjoyable 1963 film of The List of Adrian Messenger starred George C. Scott as MacDonald’s detective, with memorable if somewhat bizarre cameos from Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra, as well as a brief appearance by Huston himself. The highlight of the film is a fox hunt, a controversial sport in which MacDonald had a lifelong interest. He had been a keen horseman from very young and had an unfulfilled ambition to ride in the Grand National. MacDonald also had a lifelong love of boxing, reflected in Gentleman Bill: A Boxing Story (1922), and he loved dogs—after moving to Woodland Hills in Los Angeles, he and Ruth bred Great Danes.

Philip MacDonald died in California on 10 December 1980. At his best he was among the most innovative of the writers of the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction and, in Anthony Gethryn, he created one of the great gentleman sleuths of the genre.

TONY MEDAWAR

May 2015

All the Birds of the Air

Fell a-sighin’ and a-sobbin’

When they heard of the death

Of Poor Cock Robin.

‘Who’ll dig his Grave?’

‘I,’ said the Owl,

‘With my little Trowel;

I’ll dig his Grave.’

‘Who killed Cock Robin?’

‘I,’ said the Sparrow,

‘With my Bow and Arrow,

I killed Cock Robin!’

CHAPTER I (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

TOLLING THE BELL (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

I

THE Owl shows its blue and gilt cover on the book-stalls every Saturday morning. Thursday nights are therefore nights of turmoil in the offices in Fleet Street. They are always wearing nights; more so, of course, in hot weather than in cold. They are nights of discomfort for the office-boy and of something worse for the editor.

Spenser Hastings edited The Owl, and owned a third of it; and the little paper’s success showed him to possess both brains and capacity for hard work. For a man of thirty-three he had achieved much; but that capacity for work was hard tested—especially on Thursday nights. As to the brains, there was really no doubt of their quality. Take, for instance, The Owl ‘specials’. After he had thought of them and given birth to the first, The Owl, really a weekly review, was enabled to reap harvests in the way of ‘scoops’ without in any way degenerating into a mere purveyor of news.

The thing was worked like this: If, by the grace of God or through a member of the ‘special’ staff or by any other channel, there came to Hastings’s ears a piece of Real News which might as yet be unknown to any of the big daily or evening papers, then within a few hours, whatever the day or night of the week, there appeared a special edition of The Owl. It bore, in place of the blue and gold, a cover of red and black. The letterpress was sparse. The price was twopence. The public bought the first two out of curiosity, and the subsequent issues because they discovered that when the red and black jacket was seen Something had really Happened.

The public bought the real Owl as well. It was always original, written by men and women as yet little known and therefore unspoilt. It was witty, exciting, soothing, biting, laudatory, ironic, and sincere—all in one breath and irreproachable taste.

And Hastings loved it. But Thursday nights, press nights, were undoubtedly Hell. And this Thursday night, hotter almost than its stifling day, was the very hell of Hells.

He ruffled his straw-coloured hair, looking, as a woman once said of him, rather like a stalwart and handsome chicken. Midnight struck. He worked on, cursing at the heat, the paper, his material, and the fact that his confidential secretary, his right-hand woman, was making holiday.

He finished correcting the proofs of his leader, then reached for two over-long articles by new contributors. As he picked up a blue pencil, his door burst open.

‘What in hell—’ he began; then looked up. ‘Good God! Marga—Miss Warren!’

It was sufficiently surprising that his right-hand woman should erupt into his room at this hour in the night when he had supposed her many miles away in a holiday bed; but that she should be thus, gasping, white-faced, dust-covered, hair escaping in a shining cascade from beneath a wrecked hat, was incredible. Never before had he seen her other than calm, scrupulously dressed, exquisitely tidy and faintly severe in her beauty.

He rose to his feet slowly. The girl, her breath coming in great sobs, sank limply into a chair. Hastings rushed for the editorial bottle, glass and siphon. He tugged at the door of the cupboard, remembered that he had locked it, and began to fumble for his keys. They eluded him. He swore beneath his breath, and then started as a hand was laid on his shoulder. He had not heard her approach.

‘Please don’t worry about that.’ Her words came short, jerkily, as she strove for breath. ‘Please, please, listen to me! I’ve got a Story—the biggest yet! Must have a special done now, tonight, this morning!’

Hastings forgot the whisky. The editor came to the top.

‘What’s happened?’ snapped the editor.

‘Cabinet Minister dead. John Hoode’s been killed—murdered! Tonight. At his country house.’

‘You know?’

The efficient Miss Margaret Warren was becoming herself again. ‘Of course. I heard all the fuss just after eleven. I was staying in Marlin, you know. My landlady’s husband is the police-sergeant. So I hired a car and came straight here. I thought you’d like to know.’ Miss Warren was unemotional.

‘Hoode killed! Phew!’ said Hastings, the man, wondering what would happen to the Party.

‘What a story!’ said Hastings, the editor. ‘Any other papers on to it yet?’

‘I don’t think they can be—yet.’

‘Right. Now nip down to Bealby, Miss Warren. Tell him he’s got to get ready for a two-page special now. He must threaten, bribe, shoot, do anything to keep the printers at the job. Then see Miss Halford and tell her she can’t go till she’s arranged for issue. Then, please come back here; I shall want to dictate.’

‘Certainly, Mr Hastings,’ said the girl, and walked quietly from the room.

Hastings looked after her, his forehead wrinkled. Sometimes he wished she were not so sufficient, so calmly adequate. Just now, for an instant, she had been trembling, white-faced, weak. Somehow the sight, even while he feared, had pleased him.

He shrugged his shoulders and turned to his desk.

‘Lord!’ he murmured. ‘Hoode murdered. Hoode!’

II

‘That’s all the detail, then,’ said Hastings half an hour later. Margaret Warren, neat, fresh, her golden hair smooth and shining, sat by his desk.

‘Yes, Mr Hastings.’

‘Er—hm. Right. Take this down. “Cabinet Minister Assassinated. Murder at Abbotshall—”’

‘“Awful Atrocity at Abbotshall”,’ suggested the girl softly.

‘Yes, yes. You’re right as usual,’ Hastings snapped. ‘But I always forget we have to use journalese in the specials. Right. “John Hoode Done to Death by Unknown Hand. The Owl most deeply regrets to announce that at eleven o’clock last night Mr John Hoode, Minister of Imperial Finance, was found lying dead in the study of his country residence, Abbotshall, Marling. The circumstances were such”—pity we don’t know what they really were, Miss Warren—“the circumstances were such as to show immediately that this chief among England’s greatest had met his death at the hands of a murderer, though it is impossible at present to throw any light upon the identity of the criminal.” New paragraph, please. “We understand, however, that no time was lost in communicating with Scotland Yard, who have assigned the task of tracking down the perpetrator of this terrible crime to their most able and experienced officers”—always a safe card that, Miss Warren—“No time will be lost in commencing the work of investigation.” Fresh paragraph, please. “All England, all the Empire, the whole world will join in offering their heartfelt sympathy to Miss Laura Hoode, who, we understand, is prostrated by the shock”—another safe bet—“Miss Hoode, as all know, is the sister of the late minister and his only relative. It is known that there were two guests at Abbotshall, that brilliant leader of society, Mrs Roland Mainwaring, and Sir Arthur Digby-Coates, the millionaire philanthropist and Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Conciliation. Sir Arthur was an extremely close and lifelong friend of the deceased and would affirm that he had not an enemy in the world”—’

Miss Margaret Warren looked up, her eyebrows severely interrogative.

‘Well?’ said Hastings uneasily.

‘Isn’t that last sentence rather dangerous, Mr Hastings?’

‘Hm—er—I don’t know—er—yes, you’re right, Miss Warren. Dammit, woman, are you ever wrong about anything?’ barked Hastings; then recovered himself. ‘I beg your pardon. I—I—’

There came an aloof smile. ‘Please don’t apologise, Mr Hastings. Shall I change the phrase?’

‘Yes, yes,’ muttered Hastings. ‘Say, say—put down—say—’

‘“—and are stricken aghast at the calamity which has befallen them”,’ suggested the girl.

‘Excellent,’ said Hastings, composure recovered. ‘By the way, did you tell Williams to get on with that padding? That sketch of Hoode’s life and work? We’ve got to fill up that opposite-centre page.’

‘Yes, Mr Williams started on it at once.’

‘Good. Now take this down as a separate piece. It must be marked off with heavy black rules and be in Clarendon or some such conspicuous type. Ready? “The Owl, aghast at this dreadful tragedy, yet arises from its sorrow and issues, on behalf of the public, a solemn exhortation and warning. Let the authorities see to it that the murderer is found, and found speedily. England demands it. The author of this foul deed must be brought swiftly to justice and punished with the utmost rigour of the law. No effort must be spared.” Now a separate paragraph, please. It must be underlined and should go on the opposite page—under Williams’s article. “Aware of the tremendous interest and concern which this terrible crime will arouse, The Owl has made special arrangements to have bulletins (in the same form as this special edition) published at short intervals in order that the public may have full opportunity to know what progress is being made in the search for the criminal.

‘“These bulletins will be of extraordinary interest, since we are in a position to announce that a special correspondent will despatch to us (so far as is consistent with the wishes of the police, whom we wish to assist rather than compete with) at frequent intervals, from the actual locus of the crime a résumé of the latest developments.”’ Hastings sighed relief and leant back in his chair. ‘That’s all, Miss Warren. And I hope—since the thing is done—that the murderer’ll remain a mystery for a bit. We’ll look rather prize idiots if the gardener’s boy or someone confesses tomorrow. Get that stuff typed and down to the printers as quick as you can, please.’

The girl rose and moved to the door, but paused on the threshold.

‘Mr Hastings,’ she said, turning quickly, ‘what does that last bit mean? Are you sending one of the ordinary people down there—Mr Sellars or Mr Briggs?’

‘Yes, yes, I suppose so. What I said was all rot, but it’ll sound well. We just want reports that are a bit different from the others.’

She came nearer, her eyes wide. ‘Mr Hastings, please excuse me, but you must listen. Why not let The Owl be really useful? Oh, don’t you see what it would mean if we really helped to catch the murderer? Our reputation—our sales. Why—’

‘But I say, Miss Warren, look here, you know! We’ve not got an office full of Holmeses. They’re all perfectly ordinary fellers—’

‘Colonel Gethryn,’ said the girl quietly.

‘Eh, what?’ Hastings was startled. ‘He’d never—Miss Warren, you’re a wonder. But he wouldn’t take it on. He’s—’

‘Ask him.’ She pointed to the telephone at his side.

‘What? Now?’

‘Why not?’

‘But—but it’s two o’clock,’ stammered Hastings. He met the level gaze of his secretary’s blue eyes, lifted the receiver from its hook, and asked for a number.

‘Hallo,’ he said two minutes later, ‘is that Colonel Gethryn’s flat?’

‘It is,’ said the telephone. Its voice was sleepy.

‘Is—is Colonel Gethryn in—out—up, I mean?’

‘Colonel Gethryn,’ said the voice, ‘who would infinitely prefer to be called Mr Gethryn, is in his flat, out of bed, and upon his feet. Also he is beginning to become annoyed at—’

‘Good Lord—Anthony!’ said Hastings. ‘I didn’t recognise your voice.’

‘Now that you have, O Hastings, perhaps you’ll explain why the hell you’re ringing me up at this hour. I may mention that I am in execrable temper. Proceed.’

Spencer Hastings proceeded. ‘Er I—ah—that is—er—’

‘If those are scales,’ said the telephone, ‘permit me to congratulate you.’

Hastings tried again. ‘Something has happened,’ he began.

‘No!’ said the telephone.

‘D’you think you could—I know it’s an extraordinary thing to ask—er, but will you, er—’

Miss Margaret Warren rose to her feet, removed the instrument from her employer’s hands, put the receiver to her ear and spoke into the transmitter.

‘Mr Gethryn,’ she said, ‘this is Margaret Warren speaking. What Mr Hastings wished to do was to ask whether you could come down here—to the office—at once. Oh, I know it sounds mad, but we’ve received some amazing news, and Mr Hastings wishes to consult you. I can’t tell you any more over the phone, but Mr Hastings is sure that you’ll be willing to help. Please come; it might mean everything to the paper.’

‘Miss Warren,’ said the telephone sadly, ‘against my will you persuade me.’

CHAPTER II (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

ANTHONY GETHRYN (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

ANTHONY RUTHVEN GETHRYN was something of an oddity. A man of action who dreamed while he acted; a dreamer who acted while he dreamed. The son of a hunting country gentleman of the old type, who was yet one of the most brilliant mathematicians of his day, and of a Spanish lady of impoverished and exiled family who had, before her marriage with Sir William Gethryn, been in turn governess, dancer, mannequin, actress, and portrait painter, it was perhaps to be expected that he should be no ordinary child. And he was not.

For even after taking into consideration the mixture of blood and talents that were rightly his, Anthony’s parents soon found their only child to be possessed of far more than they had thought to give him. From his birth he proved a refutation of the adage that a Jack-of-all-Trades can be master of none.

At school and at Oxford, though appearing almost to neglect work, he covered himself with academic glory which outshone even that of his excellence at racquets and Rugby football. Not only did he follow in the mathematical tracks of his father, but also became known as an historian and man of classics.

He left Oxford in his twenty-third year; read for the bar; was called, but did not answer. He went instead round and about the world, and did not, during the three and a half years he was away, use a penny other than earnings of one sort and another.

He returned home to settle down, painted two pictures which he gave to his father, wrote a novel which was lauded by the critics and brought him not a penny, and followed up with a book of verse which, though damned by the same critics, was yet remunerative to the extent of one hundred and fifty pounds.

Politics came next, and for some six months he filled adequately the post of private secretary to a Member of Parliament suspected of early promotion to office.

Then, in Anthony’s twenty-eighth year, on top of his decision to contest a seat, came the war. On the 15th of August, 1914, he was a private in an infantry regiment; by the 1st of the following November he had taken a commission in the artillery; on the 4th of May, 1915, he was recovered from the damage caused by a rifle-bullet, an attack of trench-fever, and three pieces of shrapnel. On the 18th of July in that year he was in Germany.

That calls for explanation. Anthony Ruthven Gethryn was in Germany because his uncle, Sir Charles Haultevieux de Courcy Gethryn, was a personage at the War Office. Uncle Charles liked and had an admiration for his nephew Anthony. Also, Uncle Charles was aware that nephew Anthony spoke German like a German, and was, when occasion demanded, a person of tact, courage, and reliability. ‘A boy with guts, sir. A boy with guts! And common sense, sir; in spite of all this poetry-piffle and paintin’ cows in fields and girls with nothin’ on. A damnation clever lad, sir!’

So Uncle Charles, having heard the wailings of a friend in the Secret Service division concerning the terrible dearth of the right men, let fall a few words about his nephew.

And that is how, in the year 1915, Anthony Ruthven Gethryn came to be, not as a prisoner, in the heart of Germany. He was there for eighteen long months, and when Uncle Charles next saw his nephew there were streaks of grey in the dark hair of the thirty-year-old head.

The results of Anthony’s visit were of much value. A grateful Government patted him on the back, decorated him, gave him two months’ leave, promoted him, and then worked him as few men were worked even during the war. It was queer work, funny work, work in the dark, work in strange places.

Anthony Ruthven Gethryn left the army at the end of 1919, at the age of thirty-three. To show for his service he had a limp (slight), the C.M.G., the D.S.O., a baker’s dozen of other orders (foreign: various) and those thick streaks of gray in his black hair. Few save his intimate friends knew either of that batch of medals or of his right to the title of Colonel.

Anthony stayed with his mother until she died, peacefully, and then, since his father—who had preceded his wife by some two years—had left no more than a few hundreds a year, looked round for work.

He wrote another novel; the public were unmoved. He painted three pictures; they would not sell. He published another book of poems; they would not sell either. Then he turned back to his secretaryship, his M.P. being now a minor minister. The work was of a sort he did not care for, and save for meeting every now and then a man who interested him, he was bored to extinction.

Then, in July of 1921, Uncle Charles fell a victim to malignant influenza, became convalescent, developed pneumonia, and died. To Anthony he left a dreadful house in Knightsbridge and nine or ten thousand a year. Anthony sold the house, set up in a flat, and, removed from carking care, did as the fancy took him. When he wanted to write, he wrote. When he wished to paint, he painted. When pleasure called, he answered. He was very happy for a year.

But then came trouble. When he wrote, he found that immediately a picture would form in his head and cry aloud to be put on canvas. If he painted, verse unprecedented, wonderful, clamoured to be written. If he left England, his soul yearned for London.

It was when this phase was at its worst that he renewed a friendship, begun at Trinity, with that eccentric but able young journalist, Spencer Hastings. To Anthony, Hastings unbosomed his great idea—the idea which could be made fact if there were exactly twice as much money as Hastings possessed. Anthony provided the capital, and The Owl was born.

Anthony designed the cover, wrote a verse for the paper now and then; sometimes a bravura essay. Often he blessed Hastings for having given him one interest at least which, since the control of it was not in his own hands, could not be thrown aside altogether.

To conclude: Anthony was suffering from three disorders, lack of a definite task to perform, severe war-strain, and not having met the right woman. The first and the second, though he never spoke of them, he knew about; the third he did not even suspect.

CHAPTER III (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

COCK ROBIN’S HOUSE (#ue02e7625-8970-509b-9942-41f492cae9c0)

I

THE sudden telephone message from Hastings at two o’clock on that August morning and his own subsequent acceptance of the suggestion that he should be The Owl’s‘Special Commissioner’ had at least, thought Anthony, as he drove his car through Kingston four hours later, remedied that lack of something definite to do.

He had driven at once to The Owl’s headquarters, had arranged matters with Hastings within ten minutes, and had then telephoned to a friend—an important official friend. To him Anthony had outlined, sketchily, the scheme, and had been given in reply a semi-official ‘Mind you, I know nothing about it if anything happens, but get ahead’ blessing. He had then driven back to his flat, packed a bag, left a note for his man, and set out for Marling in Surrey.

From his official friend he had gathered that once on the right side of Miss Hoode his way was clear. As he drove he pondered. How to approach the woman? At any mention of the Press she would be bound to shy. Finally, he put the problem to one side.

The news of John Hoode’s death had not moved him, save in the way of a passing amazement. Anthony had seen too much of death to shed tears over a man he had never known. And the Minister of Imperial Finance, brilliant though he had been, had never seized the affections of the people in the manner of a Joe Chamberlain.

Passing through Haslemere, Anthony, muttering happily to himself ‘Now, who did kill Cock Robin?’ was struck by a horrid thought. Suppose there should be no mystery! Suppose, as Hastings had suggested, that the murderer had already delivered himself.

Then he dismissed the idea. A Cabinet Minister murdered without a mystery? Impossible! All the canons were against it.

He took his car along at some speed. By ten minutes to eight he had reached the Bear and Key in Marling High Street, demanded a room and breakfast, and had been led upstairs by a garrulous landlord.

II

Bathed, shaved, freshly clothed and full of breakfast, Anthony uncurled his thin length from the best chair in the inn’s parlour, lit his pipe, and sought the garden.

Outside the door he encountered the landlord, made inquiry as to the shortest way to Abbotshall, and placidly puffing at his pipe, watched with enjoyment the effect of his question.

The eyes of Mr Josiah Syme flashed with the fire of curiosity.

‘’Scuse me, sir,’ he wheezed, ‘but ’ave you come down along o’ this—along o’ these ’appenings up at the ’ouse?’

‘Hardly,’ said Anthony.

Mr Syme tried again. ‘Be you a ’tective, sir?’ he asked in a conspiratorial wheeze. ‘If so, Joe Syme might be able to ’elp ye.’ He leant forward and added in a yet lower whisper: ‘My eldest gel, she’s a nouse-maid up along Abbotshall.’

‘Is she indeed,’ said Anthony. ‘Wait here till I get my hat; then we’ll walk along together. You can show me the way.’

‘Then—then—you are a ’tective, sir?’

‘What exactly I am,’ said Anthony, ‘God Himself may know. I do not. But you can make five pounds if you want it.’

Mr Syme understood enough.

As they walked, first along the white road, then through fields and finally along the bank of that rushing, fussy, barely twenty-yards wide little river, the Marle, Mr Syme told what he knew.

Purged of repetitions, biographical meanderings, and excursions into rustic theorising, the story was this.

Soon after eleven on the night before, Miss Laura Hoode had entered her brother’s study and found him lying, dead and mutilated, on the hearth. Exactly what the wounds were, Mr Syme could not say; but by common report they were sufficiently horrible.

Before she fainted, Miss Hoode screamed. When other members of the household arrived they found her lying across her brother’s body. A search-party was at once instituted for possible murderers, and the police and a doctor notified. People were saying—Mr Syme became confidential—that Miss Hoode’s mind had been unhinged by the shock. Nothing was yet known as to the identity of the criminal, but—(here Mr Syme gave vent to many a dark suggestion, implicating in turn every member of the household save his daughter).

Anthony dammed the flow with a question. ‘Can you tell me,’ he asked, ‘exactly who’s living in the house?’

Mr Syme grew voluble at once. Oh, yes. He knew all right. At the present moment there were Miss Hoode, two friends of the late Mr Hoode’s, and the servants and the young gent—Mr Deacon—what had been the corpse’s secretary. The names? Oh, yes, he could give the names all right. Servants—his daughter Elsie, housemaid; Mabel Smith, another housemaid; Martha Forrest, the cook; Lily Ingram, kitchen-maid; Annie Holt, parlour-maid; old Mr Poole, the butler; Bob Belford, the other man-servant. Then there was Tom Diggle, the gardener, though he’d been in the cottage hospital for the last week and wasn’t out yet. And there was the chauffeur, Harry Wright. Of course, though, now he came to think of it, the gardener and the chauffeur didn’t rightly live in the house, they shared the lodge.

‘And the two guests?’ said Anthony. It is hard to believe, but he had assimilated that stream of names, had even correctly assigned to each the status and duties of its owner.

‘One gent, and one lady, sir. Oh, and there’s the lady’s own maid, sir. Girl with some Frenchy name. Duboise, would it be?’ Mr Syme was patently proud of his infallibility. ‘Mrs Mainwaring the lady’s called—she’s a tall, ’andsome lady with goldy-like sort of ’air, sir. And the gent’s Sir Arthur Digby-Coates—and a very pleasant gent he is, so Elsie says.’

Anthony gave a start of pleasure. Digby-Coates was an acquaintance of his private-secretarial days. Digby-Coates might be useful. Hastings hadn’t told him.

‘There be Habbotshall, sir,’ said Mr Syme.

Anthony looked up. On his left—they had been walking with the little Marle on their right—was a well-groomed, smiling garden, whose flower-beds, paths, pergolas and lawns stretched up to the feet of one of the strangest houses within his memory.

For it was low and rambling and shaped like a capital L pushed over on its side. Mainly, it was two storeys high, but on the extreme end of the right arm of the recumbent L there had been built an additional floor. This gave it a gay, elfin humpiness that attracted Anthony strangely. Many-hued clouds of creeper spread in beautiful disorder from ground to half-hidden chimney-stacks. Through the leaves peeped leaded windows, as a wood-fairy might spy through her hair at the woodcutter’s son who was really a prince. A flagged walk bordered by a low yew hedge ran before the house; up to this led a flight of stone steps, from the lower level of the lawns. Opposite the head of the steps was a verandah.

‘This here, sir,’ explained Mr Syme unnecessarily, ‘is rightly the back of the ’ouse.’

Anthony gave him his congé and a five-pound note, hinting that his own presence at Marling should not be used as a fount for bar-room gossip. Mr Syme walked away with a gait quaintly combining the stealth of a conspirator and the alertness of a great detective.

Anthony turned in at the little gate and made for the house. At the head of the steps before the verandah he paused. Voices came to his ear. The tone of the louder induced him to walk away from the verandah and along the house to his right. He halted by the first ground-floor window and listened, peering into the room.

Inside stood two men, one a little round-shouldered, black-coated fellow with a dead-white face and hands that twisted nervously; the other tall, burly, crimson-faced, fierce-moustached, clad in police blue with the three stripes of a sergeant on his arm.

It was the policeman’s voice that had attracted Anthony’s attention. Now it was raised again, more loudly than before.

‘You knows a blasted sight more o’ this crime than you says,’ it roared.

The other quivered, lifted a shaking hand to his mouth, and cast a hunted look round the room. He seemed, thought Anthony, remarkably like a ferret.

‘I don’t sergeant. Re-really I d-don’t,’ he stammered.

The sergeant thrust his great face down into that of his victim. ‘I don’t believe you this mornin’ any more’n I did last night,’ he bellowed. ‘Now, Belford, me lad, you confess! If you ’olds out against Jack ’Iggins you’ll be sorry.’

Anthony leaned his arms on the window-sill and thrust head and shoulders into the room.

‘Now, sergeant,’ he said, ‘this sort of thing’ll never do, you know.’

The effect of his intrusion tickled pleasantly his sense of the dramatic. Law and Order recovered first, advanced, big with rage, to the window and demanded what was the meaning of the unprintable intrusion.

‘Why,’ said Anthony, ‘shall we call it a wish to study at close quarters the methods of the County Constabulary.’

‘Who the —ing ’ell are you?’ The face of Sergeant Higgins was black with wrath.

‘I,’ said Anthony, ‘am Hawkshaw, the detective!’

Before another roar could break from outraged officialdom, the door of the room opened. A thick-set, middle-aged man of a grocerish air inquired briskly what was the trouble here.

Sergeant Higgins became on the instant a meek subordinate. ‘I—I didn’t know you were—were about, sir.’ He stood stiff at attention. ‘Just questioning of a few witnesses, I was, sir. This er—gentleman’—he nodded in the direction of Anthony—‘just pushed his ’ead—’

But Superintendent Boyd of the C.I.D. was shaking the interloper by the hand. He had recognised the head and shoulders as those of Colonel Gethryn. In 1917 he had been ‘lent’ to Colonel Gethryn in connection with a great and secret ‘round-up’ in and about London. For Colonel Gethryn Superintendent Boyd had liking and a deep respect.

‘Well, well, sir,’ he said, beaming. ‘Fancy seeing you. They didn’t tell me you were staying here.’

‘I’m not,’ Anthony said. Then added, seeing the look of bewilderment: ‘I don’t quite know what I am, Boyd. You may have to turn me away. I think I’d better see Miss Hoode before I commit myself any further.’

He swung his long legs into the room, patted the doubtful Boyd on the shoulder, sauntered to the door, opened it and passed through. Turning to his right, he collided sharply with another man, a person of between forty and fifty, dressed tastefully in light grey; broad-shouldered, virile, with a kindly face marked with lines of fatigue and mental stress. Anthony recoiled from the shock of the collision. The other stared.

‘Good God!’ he exclaimed.

‘You exaggerate, Sir Arthur,’ said Anthony.

Sir Arthur Digby-Coates recovered himself. ‘The most amazing coincidence that ever happened, Gethryn,’ he said. ‘I was just thinking of you.’

‘Really?’ Anthony was surprised.

‘Yes, yes. I suppose you’ve heard? You must have. Poor Hoode!’

‘Of course. That’s why I’m here.’

‘But I thought you’d left—’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Anthony, ‘I’ve left the Service. Quite a time ago. I’m here because—look here, this’ll sound rot if I try to explain in a hurry. Can we go and sit somewhere where we can talk?’

‘Certainly, my boy, certainly. I’m very glad indeed to see you, Gethryn. Very glad. This is a terrible, and awful affair—and, well, I think we could do with your help. You see, I feel responsible for seeing that everything’s done that can be. It may seem strange to you, Gethryn, the way I’m taking charge of this; but John and I were—well ever since we were children we’ve been more like brothers than most real ones. I don’t think a week’s passed, except once or twice, that we haven’t seen— This way: we can talk better in my room. I’ve got a sitting-room of my own here, you know. Dear old John—’

III

It was three-quarters of an hour before Anthony descended the stairs; but in that time much had been decided and arranged. So much, in fact, that Anthony marvelled at his luck—a form of mental exercise unusual in him. He was always inclined to take the gifts of the gods as his due.

But this was different. Everything was being made so easy for him. First, here was dear, stolid old Boyd in charge of the case. Next, there was Sir Arthur. As yet they were the merest acquaintances, but the knight had, he knew, for some time time been aware of and impressed by the war record of A. R. Gethryn, and had welcomed him to the stricken household. Through Sir Arthur, Miss Hoode—whom Anthony had not seen yet—had been persuaded to accept Anthony, despite his present aura of journalism.

Oh, most undoubtedly, everything was going very well! Now, thought Anthony, for the murderer. This, in spite of its painful side, was all vastly entertaining. Who killed Cock Robin Hoode?

Anthony felt more content than for the last year. It appeared that, after all, there might be interest in life.

In the hall he found Boyd; with him Poole, the butler—a lean, shaking old man—and a burly fellow whom Anthony knew for another of Scotland Yard’s Big Four.

Boyd came to meet him. The burly one picked up his hat and sought the front door. The butler vanished.

‘I wish you’d tell me, colonel,’ Boyd asked, ‘exactly where you come in on this business?’

Anthony smiled. ‘It’s no use, Boyd. I’m not the murderer. But lend me your ears and I’ll explain my presence.’

As the explanation ended, Boyd’s heavy face broke into a smile. He showed none of the chagrin commonly attributed to police detectives when faced with the amateur who is to prove them fools at every turn.

‘There’s no one I’d rather have with me, colonel,’ he said. ‘Of course, it’s all very unofficial—’

‘That’s all right, Boyd. Before I left town I rang up Mr Lucas. He gave me his blessing, and told me to carry on provided I was accepted by the family.’

Boyd looked relieved. ‘That makes everything quite easy, then. I don’t mind telling you that this is a regular puzzler, Colonel Gethryn.’

‘So I have gathered,’ Anthony said. ‘By the way, Boyd, do drop that “Colonel”, there’s a good Inspector. If you love me, call me mister, call me mister, Boydie dear.’

Boyd laughed. He found Anthony refreshingly unofficial. ‘Very well, sir. Now, if we may, let’s get down to business. I suppose you’ve heard roughly what happened?’

‘Yes’

‘Much detail?’

‘A wealth. None germane.’

Boyd was pleased. He knew this laconic mood of Anthony’s; it meant business. He was pleased because at present he felt himself out of his depth in the case. He produced from his breast-pocket a notebook.

‘Here are some notes I’ve made, sir,’ he said. ‘You won’t be able to read ’em, so let me give you an edited version.’

‘Do. But let’s sit down first.’

They did so, on a small couch before the great fireplace.

Boyd began his tale. ‘I’ve questioned everyone in the house except Miss Hoode,’ he said. ‘I’ll tackle her when she’s better, probably this afternoon. But beyond the fact that she was the first one to see the body, I don’t think she’ll be much use. Now for the facts. After supp—dinner, that is, last night, Mr Hoode, Miss Hoode, Mrs Mainwaring and Sir Arthur Digby-Coates played bridge in the drawing-room. They finished the meal at eight-thirty, began the cards at nine and finished the game at about ten. Miss Hoode then said good-night and went to her bedroom; so did the other lady. Sir Arthur went to his own sitting-room to work, and the deceased retired to his study for the same purpose.’

‘No originality!’ said Anthony plaintively. ‘It’s all exactly the same. Ever read detective stories, Boyd? They’re always killed in their studies. Always! Ever notice that?’

Boyd—perhaps a little shocked by the apparent levity—only shook his head. He went on: ‘That’s the study door over there, sir, the only door on the right side of the hall, you see. That little room just opposite to it—the one you climbed into this morning—is a sort of den for that old boy Poole, the butler. Poole says that from nine-forty-five until the murder was discovered he sat in there, reading and thinking. And he had the door open all the time. And he was facing the door. And he swears that no one entered the study by the door during the whole of that time.’

‘Mr Poole is most convenient,’ murmured Anthony. He was lying back, his legs stretched out before him.

Boyd looked at him curiously. But the thin face was in shadow, and the greenish eyes were veiled by their lids. A silence fell.

Anthony broke it. ‘Going to arrest Poole just yet?’ he asked.

Boyd smiled. ‘No, sir. I suppose you’re thinking Poole knows too much. Got his story too pat, so to speak.’

‘Something of the sort. Never mind, though. On with the tale, my Boyd.’

‘No, Poole’s not my man. By all accounts he was devoted to his master. That’s one thing. Another is that his right arm’s practically useless with rheumatism and that he’s infirm—with an absolute minimum of physical strength, so to speak. That proves he’s not the man, even if other things were against him, which they’re not. You’ll know why when I take you into that room there, sir.’ The detective nodded his head in the direction of the study door.

‘Well,’ he continued, ‘taking Poole, for the present at any rate, as a reliable witness, we know that the murderer didn’t enter by the door. The chimney’s impossible because it’s too small and the register’s down; so he must have got in through the window.’

‘Which of how many?’ Anthony asked, still in that sleepy tone.

‘The one farthest from the door and facing the garden, sir. The room’s got windows on all three sides—three on the garden side, one in the end wall, and two facing the drive; but only one of ’em—the one I said—was open.’

Anthony opened his eyes. ‘But how sultry!’ he complained.

‘I know, sir. That’s what I thought. And in this hot weather and all. But there’s an explanation. The deceased always had them—those windows—shut all day in the hot weather, and the blinds down. He knew a thing or two, you see. But he always used to open ’em himself at night, when he went in there to work. I suppose last night he must ’ave been in a great hurry or something, and only opened one of ’em.’ He looked across at Anthony for approval of his reasoning, then continued: ‘But the queer thing is, sir, that that open window shows no traces of anything—no scratches, no marks, no nothing. Nor does the flower-beds under it either.’

‘Any fingerprints anywhere on anything?’ said Anthony.

‘None anywhere in the room but the deceased’s—except on one thing. I’ve sent that up to the Yard—Jardine’s taken it—for the experts to photograph. I’ll have prints sometime this afternoon I should think.’ Boyd’s tone was mysterious.

Anthony looked at him. ‘Out with it, Boyd. You’re like a boy with a surprise for daddy.’

‘As a matter of fact, sir,’ Boyd laughed, rather shamefacedly, ‘it’s the modus operandi, so to speak.’

‘So you’ve found the ber-loodstained weapon. Boyd, I congratulate you. What was it? And whose are the fingerprints?’

‘The weapon used, sir, was a large wood-rasp, and a very nasty weapon it must have made. As for the fingerprints, I don’t know yet. And it’s my firm belief we shan’t be much wiser when we’ve got the enlargements—not even if we were to compare ’em with all the prints of all the fingers for miles round. I don’t know what it is, sir, but this case has got a nasty, puzzling sort of feel about it, so to speak.’

‘A wood-rasp, eh?’ mused Anthony. ‘Not very enlightening. Doesn’t belong to the house, I suppose?’

‘As far as I can find out, sir, most certainly not.’ Boyd’s tone was gloomy.

‘H’mm! Well, let us advance. We’ve absolved the aged Poole; but what about the rest of the household?’ Anthony spread out his long fingers and ticked off each name as he spoke. ‘Miss Hoode, Mrs Mainwaring, her maid Duboise, Sir Arthur, Elsie Syme, Mabel Smith, Maggie—no, Martha Forrest, Lily Ingram, Annie Holt, Belford, Harry Wright. Any of them do? The horticultural Mr Diggle’s in hospital and therefore out of it, I suppose.’

Boyd stared amazement. ‘Good Lord, sir!’ he exclaimed, ‘you’ve got ’em off pat enough. Have you been talking to them?’

‘Preserve absolute calm, Boyd; I have not been talking to them. I got their dreadful names from an outsider. Anyhow, what about them?’

Boyd shook his head. ‘Nothing, sir.’

‘All got confused but trustworthy alibis? That it?’

‘Yes, sir, more or less; some of the alibis are clear as glass. To tell you the truth, I don’t suspect anyone in the house. Some of the servants have got “confused alibis” as you call it, but they’re all obviously all right. That’s the servants; it’s the same only more so with the others. Take the secretary, Mr Deacon; he was up there in his room the whole time. There’s one, p’r’aps two witnesses to prove it. The same with Miss Hoode. And the other lady; to be sure she’s got no witnesses, but that murder wasn’t her job, nor any woman’s. Take Sir Arthur, it’s the same thing again. Even if there was anything suspicious—which there wasn’t—about his relations with the deceased, you can’t suspect a man who was, to the actual knowledge of five or six witnesses who saw him, sitting upstairs in his room during the only possible time when the murder can have been done.

‘No, sir!’ Boyd shook his head with vigour. ‘It’s no good looking in the house. Take it from me.’

‘I will, Boyd; for the present anyhow.’ Anthony rose and stretched himself. ‘Can I see the study?’

Boyd jumped up with alacrity. ‘You can, sir. We’ve been in there a lot, taking photos, et cetera; but it’s untouched—just as it was when they found the body.’

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_cec20fd8-bb5d-5680-acae-228d09616f37)

THE STUDY (#ulink_cec20fd8-bb5d-5680-acae-228d09616f37)

ONCE across the threshold of the dead minister’s study, Anthony experienced a change of feeling, of mental attitude. Until now he had looked at the whole business in his usual detached and semi-satirical way; the reasons for his presence at Abbotshall had been two only—affection for Spencer Hastings and desire to satisfy that insistent craving for some definite and difficult task to perform. He had even felt, at intervals throughout the morning, a wish to laugh.

But, now, fairly in the room, this aloofness failed him. It was not that he felt any sudden surge of personal regret. It was rather that, for him at least, despite the sunlight which blazed incongruously in every corner, some cold, dark beastliness brooded everywhere.

The big room was gay with chintz and as yet unfaded flowers of the day before; the solid furniture was of some beauty—in fact, a charming room. Yet Anthony shivered even before he had seen the thing lying grotesque upon the hearth. When he did see it, somehow the sight shook him out of the nightmare of dark fancy. He stepped forward to look more closely.

Came the sound of a commotion from the hall. With a muttered excuse, Boyd went quickly from the room. Anthony knelt to examine the body.

It sprawled upon the hearth-rugs, legs towards the window in the opposite wall. The red-tiled edge of the open grate forced up the neck. The almost hairless head was dreadfully battered; crossed and re-crossed by five or six gaping gashes, each nearly half an inch wide and an inch or so deep. Of the scalp little remained but islands and peninsulas of skin and bone streaked with the dark brown of dried blood, among it ribands of grey film where the brain had oozed from the wounds.

The body was untouched, though the clothes were rumpled and twisted. The right arm was outstretched, the rigid fingers of the hand resting among the pots of fern which filled the fireplace. The left arm was doubled under the body.

Anthony, having gazed his fill, rose to his feet. As he did so, Boyd re-entered. He looked flushed and not a little annoyed.

Anthony turned to him, raising his eyebrows.

‘Only a bit more trouble with some of these newspaper fellows, sir. But thank the Lord, I’ve got rid of ’em now. Told ’em I’d give ’em a statement tonight. What they’d say if they knew you were here—and why—God knows. There’ll be a row after the case is over, but there you are. Miss Hoode’s agreeable to you, and I don’t blame her, but she won’t hear of any of the others being let in. I don’t blame her for that either.’ He nodded towards the body. ‘What d’you make of it, sir?’

‘Shocking messy kill,’ Anthony said.

‘You’re right, sir. But what about—things in general, so to speak?’

Anthony looked round the room. It bore traces of disturbance. Two light chairs had been overturned. Books and papers from the desk strewed the floor. The grandfather clock, which should have stood sentinel on the left of the door as one entered it, had fallen, though not completely. It lay face-downwards at an angle of some forty-five degrees with the floor, the upper half of its casing supported by the back of a large sofa.

‘Struggle?’ said Anthony.

‘Yes,’ said Boyd.

‘Queer struggle,’ said Anthony. He sauntered off on a tour of the room.

Boyd watched him curiously as he halted before the sofa, dropped on one knee, and peered up at the face of the reclining clock.

He looked up at Boyd. ‘Stopped at ten-forty-five. That make the murder fit in with the times the people in the house have told you?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘When are you going to have the room tidied?’

‘Any time now. We’ve got the photos.’

‘Right.’ Anthony got to his feet. ‘Let us, Boyd, unite our strength and put grand-dad on his feet.’

Between them they raised the clock. Anthony opened the case and set the pendulum swinging. A steady tick-tock began at once.

Anthony looked at his watch. ‘Stopped exactly twelve hours ago, did grandfather,’ he said. ‘Doesn’t seem to be damaged, though.’

‘No, sir. It takes a lot to put those old clocks out of order.’

Anthony went back to the front of the sofa and stood looking down at the carpet.

‘No fingerprints, you said?’

‘Except on the wood-rasp, absolutely none but those of the deceased, sir. I’ve dusted nearly every inch of the room with white or black. All I got for my pains were four good prints of the deceased’s thumb and forefinger. They’re easy enough to tell—very queer-shaped fingers and a long scar on the ball of his right thumb.’

Anthony changed the subject. ‘What time did you get here, Boyd?’

‘About four this morning. We came by car. I made some preliminary inquiries, questioned some of the people, and went down to the village at about eight.’

‘Who’s that great red hulk of a sergeant?’ said Anthony, flitting to yet another subject. ‘You ought to watch him, Boyd. When I came along he was indulging in a little third degree.’

‘I heard it, sir. That’s why I came in.’

‘Good. Who was the timid little ferret?’

‘Belford—Robert Belford, sir. He’s a sort of assistant to Poole and was valet to the deceased.’

‘How did he answer when you questioned him?’

‘Very confused he was. But his story’s all right—very reasonable. I don’t consider him, so to speak. He hasn’t got the nerve, or the strength.’

Anthony stroked his chin. ‘It’s easy enough to see,’ he said, ‘that you don’t want to be persuaded away from your idea that an outsider did this job.’

‘You’re right, sir,’ Boyd smiled. ‘As far as I’ve progressed yet an outsider’s my fancy. Most decidedly. Still, one never knows where the next turning’s going to lead to, so to speak. Of course, I’ve got a lot of inquiries afoot—but so far we’ve less than nothing to go on.’

‘Anything stolen?’

‘Nothing.’

Anthony was still gazing down at the carpet before the sofa. Again he dropped on one knee. This time he rubbed at the thick pile with his fingers. He rose, darting a look round the room.

‘What’s up, sir?’ Boyd was watching attentively.

‘A most convenient struggle that,’ murmured Anthony.

‘What’s that? What d’you mean, sir?’

‘I was remarking, O Boyd, that the struggle had been, for the murderer, of an almost incredible convenience. Observe that the two chairs which were overturned are far from heavy; observe also that the carpet is very far from thin. These light chairs fell, not, mark you, on the parquet edging of the floor, but conveniently inwards upon this thickest of thick carpets. Observe also, most puissant inspector, that the articles dislodged from the writing-table, besides falling on the carpet, are nothing but light books and papers. Nothing heavy, you see. Nothing which would make a noise.’

‘I follow you, sir,’ Boyd cried. ‘You mean—’

‘’Ush, ’ush, I will ’ave ’ush! I would finally direct your attention to the highly convenient juxtaposition of this sofa here and our friend the clock. This sofa is a solid, stolid lump of a sofa; it’s none of your trifling divans. In fact, it would require not merely a sudden jerk but a steady and lusty pull to move it, wouldn’t it?’

The detective applied his considerable weight to the arm of the sofa. Nothing happened.

‘You see!’ continued Anthony with a gesture. ‘See you also then the almost magical convenience with which, in the course of the struggle, this lumping sofa was moved back towards grandfather, who stood nearly three feet from the sofa’s usual position, which position can be ascertained by noting these four deep dents made in the carpet by the castors. Oh, it’s all so convenient. The sofa’s moved back, then grandfather falls, not with a loud crash to the floor but quietly, softly, on to the back of the sofa. Further, those two vases on that table there beside the clock weren’t upset at all by the upheaval. Those vases wobble when one walks across the room, Boyd. No, it won’t do; it won’t do at all.’

‘You’re saying there wasn’t any struggle at all; that the scene was set, so to speak.’ Boyd’s tone was eager. His little grey eyes were alight with interest.

Anthony nodded. ‘Your inference is right.’

‘I had explained things to myself by saying that the carpet was thick and old Poole rather deaf,’ said the detective, ‘because he did say that he heard a noise like someone walking about. Of course, he just thought it was his master. I’ll wager it wasn’t, though. I’m sure you’re right, sir. I hadn’t noticed the sofa had been shifted. This is a very queer case, sir, very queer!’

‘It is, or anyhow it feels like that. What about the body, Boyd? Aren’t you going to have it moved?’

‘Yes, sir, any time now. It was going to be moved before you came; then Jardine wanted to take some more photos. After that, you being here, sir—well, I thought if you were going to have anything to do with the case you might like to see everything in status quo, so to speak.’

Anthony smiled. ‘Thanks, Boyd,’ he said. ‘You’re a good chap, you know. This isn’t the first job we’ve done together by any means; but all the same, it’s most refreshing to find you devoid of the pro’s righteous distrust of the amateur.’

Boyd smiled grimly. ‘Oh, I’ve got that all right, sir. But I don’t regard you in that light, if I may say so, though we may disagree before this case is over. And—well, sir, I’ve not forgotten what you did for me that night down at Sohlke’s place in Limehouse—’

‘Drop it, man, drop it,’ Anthony groaned.

Boyd laughed. ‘Very well, sir. Now I’ll go and see about having the body moved upstairs.’

‘And I,’ said Anthony, ‘shall think—here or in the garden. By the way, when’s the inquest?’

‘Tomorrow afternoon, here,’ said Boyd, and left the room.

Anthony ruminated. This study of Hoode’s, he reflected, was curious, being in itself the end of the longer wing of the house and having, therefore, window or windows in all three sides. As Boyd had said, only one of these windows was open, the farthest from the door of the three which looked out upon the terraced gardens and the river at their foot. All the others—two in the same wall, one in the end wall, and two overlooking the drive—were shut and latched on the inside. The open one was open top and bottom.

Anthony looked at it, then back at the writing-table. He seemed dissatisfied, for he next walked to the window, surveyed the room from there, and then crossed to the swivel-chair at the writing-table and sat down. From here he again peered at the open window, which was then in front of him and slightly to his left.

He was still in the chair when Boyd came back, bringing with him a policeman in plain clothes and a man in the leather uniform of a chauffeur. Anthony did not move; did not answer when Boyd spoke to him.

The body covered and lifted, the grim little party, Boyd leading, made for the door. As they steered carefully through it, the grandfather clock began to strike the hour. Its deep ring had, it seemed to Anthony, a note ominous and mournful.

The door clicked to behind the men and the shrouded thing they carried. The clock struck again.

‘Good for you, grandfather,’ muttered Anthony, without turning in his chair to look. ‘I wish to High Heaven you could talk for a moment or two.’

‘Bong!’ went the clock again.

Anthony pulled out his watch. The hands stood at eleven o’clock. ‘All right, grand-dad,’ he said. ‘You needn’t say any more. I know the time. I wish you could tell me what happened last night instead of being so damned musical.’

The clock went on striking. Anthony wandered to the door, paused; and went back to the writing-table. As he sat down again the clock chimed its final stroke.

He felt a vague discomfort, shook it off and continued his scrutiny of the table. It was of some age, and beautiful in spite of its solidity. The red leather covering of its top had upon it many a stain of wear and inks. Yet one of these stains seemed to differ from the general air of the others. He rubbed it with his fingers. It was raised and faintly sticky. It was at the back of the flat part of the table-top. Immediately behind it rose two tiers of drawers and pigeon-holes. Also, its length was bisected by a crack in the wood.

He rubbed at the stain again; then cursed aloud. That vague sense of something wrong in the room, something which did not fit, the essential sanity of life, had returned to his head and spoilt these new thoughts.

The door opened and shut. ‘What’s the matter, sir? Puzzled?’ Boyd came and stood behind him.

‘Yes, dammit!’ Anthony swung round impatiently. ‘This room’s getting on my nerves. Either there’s something wrong in it or I’ve got complex fan-tods. Never mind that, though. Boyd, I think I’m going to give you still more proof that there was no struggle. Come here.’

Boyd came eagerly. Anthony twisted round to face the table again.

‘Attend! The body was found over there by the fireplace. If one accepts as true the indications that a struggle took place, the natural inference is that Hoode was overpowered and struck down where he was found. But we have found certain signs that lead us to believe that the struggle was, in fact, no struggle at all, and here, I think, is another which will also show that Hoode’s body was dragged over to the hearth after he had been killed.’

Boyd grew excited. ‘How d’you mean, sir?’

‘This is what I mean.’ Anthony pointed to the stain he had been examining. ‘Look at this mark here, where my finger is. Doesn’t it look different to the others?’

‘Can’t say that it does to me, sir. I had a look over that table myself and saw nothing out of the ordinary run.’

‘Well, I beg to differ. It not only looks different, it feels different. I notice these things. I’m so psychic, you know!’

Boyd grinned at the chaff, watching with keen interest as Anthony opened a penknife and inserted the blade in the lock of the table’s middle drawer.

‘I think,’ said Anthony, ‘that this is one of those old jump locks. Aha! it is.’ He pulled open the drawer. ‘Now, was that stain different? Voilà! It was.’

Boyd peered over Anthony’s shoulder. The drawer was a long one, reaching the whole width of the table. In it were notebooks, pencils, half-used scribbling pads, and, at the back, a pile of notepaper and envelopes.

On the white surface of the topmost envelope of the pile was a dark, brownish-red patch of the size, perhaps, of a half-crown. Boyd examined it eagerly.

‘You’re right, sir!’ he cried. ‘It’s blood right enough. I see what you were going to say. This is hardly dry. It must have dripped through that crack where the stain you pointed out was. And the position of that stain is just where the deceased’s head would have fallen if he had been sitting in this chair here and had been hit from behind.’

‘Exactly,’ said Anthony. ‘And after the first of those pats on the head Hoode must’ve been unconscious—if not dead. Ergo, if he received the first blow sitting here, as this proves he did, there was no struggle. One doesn’t sit down at one’s desk to resist a man one thinks is going to kill one, does one? What probably happened is that the murderer—who was never suspected to be such by Hoode—got behind him as he sat here, struck one or all of the blows, and then dragged the body over to the hearth to lend a touch of naturalness to the scene of strife he was going to prepare. He must be a clever devil, Boyd. There’s never a stain on the carpet between here and the fireplace. There wouldn’t have been on the table either, only he didn’t happen to spot it.’

The detective nodded. ‘I agree with you entirely, sir.’

But Anthony did not hear him. That wrong something was troubling him again. He clutched his head, trying vainly to fix the cause of this feeling.

Boyd tried again. ‘Well, we know a little more now, sir, anyhow. Quite a case for premeditation, so to speak—thanks to you.’

Anthony brought himself back to earth. ‘Yes, yes,’ he said, ‘But hearken again, Boyd. I have yet more to say. Don’t wince, I have really. Here it is. Assuming the reliability as a witness of Poole, the old retainer, we know the murderer didn’t come into this room through the door. Nor could he, as you’ve explained, have used the chimney. Remains the one window that was open. Observe, O Boyd, that that window is in full view of a man seated at this table. Now one cannot come through a window into a room at a distance of about two yards from a man seated therein at a table without attracting the attention of that man unless that man is asleep.’

‘I shouldn’t think Hoode was asleep, sir.’

‘Exactly. It is known that Hoode was a hard worker. Further, if I’m not mistaken, he’s been more than usually busy just recently—over the new Angora Agreement. I think we can take it for granted he wasn’t asleep when the murderer came in through that window. That leads us to something of real importance, namely, that Hoode was not surprised by the entry of the murderer.’

Boyd scratched his head. ‘’Fraid I don’t quite get you, as the Yanks say, sir.’

Anthony looked at him with benevolence. ‘To make myself clearer, I’ll put it like this: he either (i) expected the murderer—though not, of course, as such—and expected him to enter that way; or (ii) did not expect him to enter that way, but on looking up in surprise saw someone who, though he had entered in that unfamiliar way, was yet so familiar in himself as not to cause Hoode to remain long, if at all, out of his seat. Personally, I think he didn’t leave his chair at all. Is not all this well spoken, Boyd?’

‘True enough, sir. I think you’re quite right again. I’ve been a fool.’ Boyd was dejected. ‘Of the two views you propounded, so to speak, I think the first’s the right one. The murderer was an outsider, but one the deceased was expecting—and by that entrance.’

‘And I,’ said Anthony, ‘incline strongly toward my second theory of the unconventional entry of the familiar.’

Boyd shook his head. ‘You’d hardly credit it, sir,’ he said solemnly, ‘but some of these big men get up to very funny games. I’ve had over twenty years in the C.I.D., and I know.’

‘The mistake you’re making in this case, Boyd,’ Anthony said, ‘is thinking of it as like all your others. From what little I’ve seen so far of this affair it’s much more like a novel than real life, which is mostly dull and hardly ever true. As I asked you before, d’you ever read detective stories? Gaboriau, for instance?’

‘Lord, no, sir!’ smiled the real detective.

‘You should.’

‘Pardon me, sir, but you’re a knock-out at this game yourself and it makes me wonder, so to speak, how you can hold with all that ’tec-tale truck.’

‘A knock-out? Me?’ Anthony laughed. ‘And I feel as futile as if I were Sherlock Holmes trying to solve a case of Lecoq’s.’ He put a hand to his head. ‘There’s something about this room that’s haunting me! What is the damned thing? Boyd, there’s something wrong about the blasted place, I tell you!’

Boyd looked bewildered. ‘I don’t know what you mean, sir.’ Then, to humour this eccentric, he added: ‘Ah! if only this furniture could tell us what it saw last night.’

‘I said that to the clock,’ said Anthony morosely. Then suddenly: ‘The clock, the clock! Grandpa did tell me something! I knew I’d seen or heard something that was utterly wrong, insane. The clock! Good God Almighty! What a fool not to think of it before!’

Boyd became alarmed. His tone was soothing. ‘What about the clock, sir?’

‘It struck. D’you remember it beginning when you were taking the body away?’

‘Yes.’ Boyd was all mystification.

‘What time was that?’

‘Why, eleven, of course, sir.’

‘Yes, it was, my canny Scot. But grandfather said twelve. I was thinking about something else, I must have counted the strokes unconsciously.’

‘But—but—are you sure it struck twelve when’—Boyd glanced up at the old clock—‘when it said eleven?’

Anthony crossed the room, opened the glass casing of the old clock-face, and moved the hands on fifteen minutes. They stood then at twelve.

‘Bong!’ went the clock.

They waited. It did not strike again.

Anthony was triumphant. ‘There you are, Boyd! Grandpa looks twelve and says one. There’s another strand of that rope you’re making for the murderer. Miss Hoode came in here at eleven-ten, to find the murder done and the murderer gone. Your time’s almost fixed for you. He wasn’t here at eleven-ten, but he was here after eleven, because, to put the striking of that clock out as it is, the murderer must have put back the hands after the hour—eleven, that is—had struck. If he’d done it before the striking had begun, grand-dad wouldn’t be telling lies the way he is.’

Boyd’s expression was a mixture of elation and doubt. ‘I suppose that’s right, sir,’ he said. ‘About the striking, I mean. Yes, of course it is; just for the moment I was a bit confused, so to speak. Couldn’t work out which way the mistake would come.’

‘It seems to me,’ said Anthony, ‘that the whole reason he faked this elaborate struggle scene was in order that the clock could be stopped under what would seem natural circumstances. But why, having stopped the clock, did he alter it? Two reasons occur to me. One is that he merely wished to make it seem that the murder was done at any other time except that when it really was. That’s rather weak, and I prefer my second idea. That is, that the time to which he moved the hands has a significance and wasn’t merely a chance shot. In other words, he set the thing at ten-forty-five because he had a nice clean alibi for that time. Judging by the rest of his work he’s a man of brains; and that would’ve been a pretty little safeguard—if only he hadn’t made that mistake about the striking.’

‘They all make bloomers—one time or another, sir. That’s how we catch ’em in the main.’

‘I know.’ Anthony’s tone was less sure than a moment before. ‘All the same it’s a damn silly mistake. Doesn’t seem to fit in somehow. I’d expected better things from him.’

‘Oh, I don’t know, sir. He’d probably got the wind up, as they say, by the time he’d got so near finishing.’

Anthony shrugged. ‘Yes, I suppose you’re right. By the way, Boyd, tell me this. How did Miss Hoode come to be downstairs at ten past eleven? I thought she was supposed to have gone to bye-bye after that game of cards.’

‘As far as I know—I haven’t been able to see her yet, sir—she came down to use the telephone—not this one but the one in the hall—about some minor affair she’d forgotten during the day. After she’d finished phoning she must’ve wanted to speak to her brother. Probably about the same matter. That’s all, sir.’

‘It’s so weak,’ said Anthony, ‘that it might possibly be true.’ Then, after a pause: ‘I think I’ve had about enough of this tomb. What you going to do next, Boyd? I’m for the garden.’ He walked to the door. ‘You took the weaker end of my reasoning if you still believe in the mysterious outsider.’

Boyd followed across the hall, through the verandah and down the steps which led from the flagged walk behind the house to the lawns below.

Anthony sat himself down upon a wooden seat set in the shade of a great tree. He showed little inclination for argument.

But Boyd was stubborn. ‘You know, sir,’ he said, ‘you’re wrong in what you say about the “insider”. You’d agree with me if you’d been here long enough to sift what evidence there is and been able the way I have to see and talk to all the people instead of hearing about them sketchy and second-hand, as it were.’

Anthony looked at him. ‘There’s certainly something in that, Boyd. But it’ll take a lot to shift me. Mind you, my predilection for the “insider” isn’t a conviction. But it’s my fancy—and strong.’

Boyd fumbled in his breast-pocket. ‘Then you just take a good look at this, sir.’ He held out some folded sheets of foolscap. ‘I made that out before you got here this morning. It’ll tell you better what I mean than I can talking. And I only sketched the thing to you before.’

Anthony unfolded the sheet, and read:

SUMMARY OF INFORMATION ELICITED

1. MissLAURA HOODE. Played cards until 10 o’clock with deceased, Sir A.D.-C., and Mrs Mainwaring. Then went to bed. Was seen in bed at approximately 10.30 by Annie Holt, parlour-maid, who was called into room to take some order as she passed on her way to the servants’ quarters. Miss Hoode remembered, at about 11.5, urgent telephone call to be made. Got up, went downstairs to phone, then thought she would consult deceased first. Entered study, at 11.10, and discovered body. [Note—By no means a complete alibi; but it seems quite out of question that this lady is in any way concerned. She is distraught at brother’s death and was known to be a devoted sister. They were, as always, the best of friends during day.]

N.B. It appears impossible for a woman to have committed this crime, since the necessary power to inflict blows such as caused death of deceased would be that of an unusually strong man.

2. Mrs R. MAINWARING. Retired at same time as Miss Hoode Was seen in bed by her maid, Elise Duboise, at 10.35. Was waked out of heavy sleep by parlour-maid, Annie Holt, after discovery of body of deceased.

3. ELISE DUBOISE. This girl sleeps in room communicating with Mrs Mainwaring’s. The night was hot and the door between the two rooms was left open. Mrs Mainwaring heard girl get into bed at about 10.40. The parlour-maid had to shake her repeatedly before she woke.

4. Sir A. DIGBY-COATES. Went upstairs, after cards, to own sitting-room (first-floor, adjoining bedroom) to work at official papers. Pinned note on door asking not to be disturbed, but had to leave door open owing to heat. Was seen, from passage, between time he entered room until time murder was discovered, at intervals averaging a very few minutes by Martha Forrest (cook), Annie Holt (parlour-maid), R, Belford (man-servant), Elise Duboise, Mabel Smith (housemaid), and Elsie Syme (housemaid). The time during which the murder must have been committed is covered.

5. Mr A. B. T. DEACON (Private Secretary to deceased). Went to room (adjoining that of Sir A. D.-C.) to read at approximately 10.10. Was seen entering by Mabel Smith, who was working in linen-room immediately opposite. She had had afternoon off and was consequently very busy. Stayed there till immediately (say two minutes) before murder was discovered. She can swear Mr Deacon never left room the whole time, having had to leave door of linen-room open owing to heat.