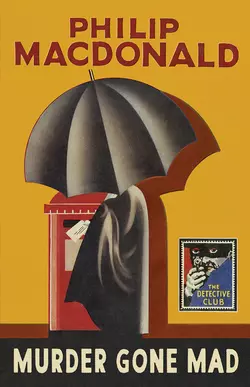

Murder Gone Mad

Philip MacDonald

L. Tyler C.

The first Golden Age detective novel to feature a serial killer with no rational motive - and surely impossible for Scotland Yard to solve?A long knife with a brilliant but perverted brain directing it is terrorising Holmdale – innocent people are being done to death under the very eyes of the law. After every murder a business-like letter arrives announcing that another ‘removal has been carried out’, and Inspector Pyke of Scotland Yard has nothing to go on but the evidence of the bodies themselves and the butcher’s own bravado. With clear thinking impossible in the face of such a breathless killing spree, the police make painfully slow progress: but how do you find a maniac who has no rational motive?Philip MacDonald had shown himself in The Noose and The Rasp to be a master of the detective novel. In Murder Gone Mad he raised the stakes with the first Golden Age crime novel to feature a motiveless serial killer prompted only by blood lust – inspired by the real-life case in 1929 of the Düsseldorf Monster – and this time without the familiar Anthony Gethryn on hand to reassure the reader.This Detective Story Club classic is introduced by L. C. Tyler, Chair of the Crime Writers Association and author of the award-winning ‘Elsie and Ethelred’ crime novels and the John Grey historical mysteries.

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#ulink_fe980f04-0655-5706-b015-dd579b96a7d9)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published for The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1931

Copyright © Estate of Philip MacDonald 1931

Introduction © L. C. Tyler 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216351

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008216368

Version: 2016-11-23

Contents

Cover (#u3ece1815-26ae-5624-b6eb-620365867cb1)

Title Page (#uf08ff41a-75d1-5e3b-a1fc-70891ed07855)

Copyright (#u22d91005-fcee-5f9e-88f3-d897c4654561)

Introduction (#u9b1f4744-e498-5b21-89e2-3b8266f273c8)

Chapter I (#u5e37a24e-8586-5c79-b721-8bb91cd43091)

Chapter II (#u43db0ab1-8a49-5417-b0c8-605c6e485b35)

Chapter III (#uac8a2f1a-b9d1-58ee-b63e-c2c51ca3aaa5)

Chapter IV (#uffc6b69d-fbaa-5e19-998c-30f9ee345ed2)

Chapter V (#uef601a85-3c2e-56da-8856-804944ea19f7)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_56b80905-6f21-53cd-a28f-95df3c5cfec7)

INTRODUCTIONS, like prologues, are often best skipped. They are not, after all, what you have bought the book for and few good stories really need an explanation.

And yet, readers of this volume may welcome a short account of Philip MacDonald and his work, if only because after his death in 1980 his books quickly slipped from public view and information on him can be surprisingly difficult to find and sometimes contradictory. Even the year of MacDonald’s birth has for some reason become veiled in mystery. 1896, 1899, 1900 and 1901 are all quoted by reliable sources.

The question of his birth can be quickly cleared up. Census records show that he was born on 5 November 1900 into a family that was very much part of the British literary establishment. His grandfather was the Scottish novelist and poet, George MacDonald, whose pioneering fantasy writing influenced many other writers, including J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and indeed G.K. Chesterton. His father was the playwright and novelist Ronald MacDonald and his mother the actress Constance Robertson. At the time of his birth the family was living (with one servant) at 9 Rossetti Mansions, Chelsea. Later they moved (gaining an additional servant on the way) to 25 St Margaret’s Road, Twickenham, from where MacDonald attended St Paul’s School. During the First World War, he served in Mesopotamia, though again details are hard to come by. His publisher after the war claimed he had served as a trooper in a ‘famous cavalry regiment’ but never thought to say which one and, to the best of my knowledge, nobody has subsequently identified it for certain. (It may have been the Machine Gun Corps Cavalry.) Whichever regiment it was, and whatever action he saw, MacDonald made good use of his experience in one of his earliest novels, Patrol (1927),in which a cavalry troop finds itself lost in the desert. It is told very much from the point of view of the ordinary soldier—the only officer is already dead at the start of the tale, having failed to impart to his second-in-command their current location or the object of the mission. Only the bravery and common sense of the troopers can see them through to possible safety—it is apparent where in the military hierarchy MacDonald’s sympathies lay.

His earliest publication was the perhaps unfortunately named Ambrotox and Limping Dick (1920),written jointly with his father under the pen name Oliver Fleming. He would later write variously as Anthony Lawless, Martin Porlock, W.J. Stewart and Warren Stewart. The first book under his own name however was The Rasp, which was published by Collins in 1924 and introduced his main series protagonist, gentleman detective and scholar Colonel Anthony Ruthven Gethryn. The Rasp was an immediate success and was later made into a film. Other crime novels followed in rapid succession. In 1931 MacDonald published no fewer than seven: four under his own name, two as Lawless and one as Porlock. In the same year he moved to Hollywood with his new wife, the author F. Ruth Howard, and started a career as a screenwriter, both adapting his own work and writing original film scripts. These last included contributions to popular series such as Charlie Chan and Mr Moto. He also adapted Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca and Agatha Christie’s short story ‘Philomel Cottage’(as Love from a Stranger).

Though MacDonald maintained the flow of crime fiction novels during the 1930s, film work and later television increasingly dominated his output. He did however win two Edgar Allan Poe Awards for his short stories in the ’50s and his final Gethryn novel, The List of Adrian Messenger, published in 1959, is arguably the finest that he ever wrote.

What characterises MacDonald’s output, in addition to the remarkable speed with which he produced it, is its inventiveness. At the same time that Agatha Christie was experimenting with storyline, producing one classic plot after another, MacDonald was consciously experimenting with the form of the detective novel. The Maze (1932), another of his best works, dispenses with a detective almost completely. The reader is presented with transcripts of the evidence given by witnesses at a coroner’s court. Only at the very end does Anthony Gethryn appear to confirm or refute the reader’s solution. Rynox (1930) begins with an epilogue, ends with a prologue and is interrupted by a series of sardonic comments from the author—MacDonald acting as a sort of Greek chorus in his own book, foreshadowing future developments. ‘All is not well’ we are told ‘with RYNOX. RYNOX is at that point where one injudicious move, one failure of judgment, one coincidental piece of bad luck will wreck it …’ Like most Greek choruses, he’s spot on. There is a metafictional side to his work as well. Having, in another book, discovered a body in the study, Gethryn remarks to the policeman: ‘Ever read detective stories, Boyd? They’re always killed in their studies. Always! Ever notice that?’ MacDonald also uses humour well and produces some lovely quotable lines. One of my favourites (from Adrian Messenger) is: ‘That winter, like all California winters, was unusual.’

The other side of the coin of this remarkable flow of witty and innovative books was however a tendency to ignore detail in a way that less brilliant, more conventional writers would never have dared to do. Julian Symons described MacDonald as ‘a restless but careless experimenter’. There are times when you feel that MacDonald is so caught up in his own cleverness that he misses, or can’t be bothered with, the obvious. On at least one occasion the reader is left wondering why it didn’t occur to the police to look for fingerprints, which would have shortened their investigations by a couple of hundred pages. But the pace is such that it probably doesn’t occur to the reader either until long after they have finished the book.

Murder Gone Mad, the third of MacDonald’s books to be republished in this series,encapsulates many of the strengths outlined above. It is one of the earliest books to make use of the serial killer. (It also incidentally anticipates the invention of CCTV as a means of detecting crime.) It works splendidly as a ‘fair play’ detective story. But at the same time it is a very clever satire on the British class system. Holmdale, the scene of the murders, is a new town, painfully conscious of its image. It does not like to be referred to as ‘Holmdale Garden City’, with the lower middle class undertones that the name carries, and certainly does not like the bad publicity created by a series of grizzly murders. The killer seems determined to lower the tone of things still further, their invoice-like communications to the police, one following each killing, smacking very much of ‘trade’:

My Reference ONE

R.I.P.

Lionel Frederick Colby,

died Friday 23rd November

THE BUTCHER

When a report is produced by the police examining the murders to date, the victims are listed under ‘clerical class’, ‘leisured class’, ‘labouring class’ and ‘skilled workman class’—a fairly nuanced series of distinctions. But, the police report concludes, the murderer ‘must belong to the clerical or governing class’ to have the opportunity to mix with all classes of the community—a member of the working classes simply wouldn’t have the contacts. When Dr Reade is suspected, somebody who knows him protests: ‘Blasted rot, my dear fellow! What I mean: a chap, a decent chap like Reade, the sort of chap who’s always good for a hand of Bridge and that sort of thing; the sort of chap one has dinner with and all that … he can’t possibly be this Butcher.’ But, of course, we all know that he or any of the citizens of Holmdale could be the killer. MacDonald also anticipates Nancy Mitford’s popularisation of U and non-U language by putting the word ‘lounge’ firmly in quotation marks.

All classes are however united in their horror at the unremitting succession of killings. ‘Is our city to be another Düsseldorf?’ asks the local paper, somewhat enigmatically—not just lower middle class then but, worse still, German?

The Düsseldorf references are almost certainly inspired by the case of Peter Kürten, the so-called Vampire of Düsseldorf or Düsseldorf Monster, who during the 1920s murdered at least nine people, mainly (like The Butcher) by stabbing, and who was executed the year Murder Gone Mad was published. It took the German police over a year to catch him—something that does not impress the British officers seeking the Holmdale murderer, though initially they do little better than their Düsseldorf counterparts—perhaps because Gethryn is, we learn, injured and unavailable. This time it is Superintendent Arnold Pike, a character from earlier books, who leads the investigation and eventually makes the arrest under what prove to be trying circumstances. Thus it all ends in precisely the way a detective story is supposed to end, with the reader having been given a fair chance to guess which suspect Pike will apprehend at the conclusion.

Murder Gone Mad, originally published in MacDonald’s annus mirabilis of 1931, is one of his most successful, most satisfying books. John Dickson Carr listed it as one of the ten best detective novels ever written. Its reprinting in the revived Detective Club series will hopefully introduce it to a new generation of crime fans and help re-establish MacDonald’s reputation as one of the most original and most readable writers of the Golden Age.

L.C. TYLER

September 2016

CHAPTER I (#ulink_befd137a-badb-523f-833b-89abb3de9ad4)

I

THERE had been a fall of snow in the afternoon. A light, white mantle still covered the fields upon either side of the line. The gaunt hedges which crowned the walls of the cutting before Holmdale station were traceries of white and black.

The station-master came out on to the platform from his little overheated room. He shivered and blew upon his hands. The ringing click-clock of the ‘down’ signal arm dropping came hard to his ears on the cold air.

‘Harris!’ called the station-master. ‘Six-thirty’s coming!’

A porter came out from behind the bookstall. He was thrusting behind a large and crimson ear a recently pinched-out end of a cigarette.

The six-thirty came in with much hissing of steam and a whistling grind of brakes. The six-thirty reached the whole length of Holmdale’s long platform. The six-thirty looked like a row of gaily-lighted, densely-populated little houses. The six-thirty’s engine, for some reason known only to itself and its attendants, let off steam in a continuous and teeth-grating shriek. The doors of the six-thirty all along the six-thirty’s flank began to swing open. Holmdale was the six-thirty’s first stop since leaving St Pancras, now forty miles and forty-five minutes behind it.

The station-master stood by the foot of the steps leading up to the bridge. He opened a square and bearded mouth and chanted his nightly chant, quite unintelligibly, of what was going to happen to the train. He should properly have walked up and down the train with his chant, but he knew only too well that to walk at all against this tide which now covered the platform like a moving carpet of black, huge locusts, was impossible.

The six-thirty’s engine ceased its hissing. There was a great slamming of doors which sounded under the station’s iron roof like big guns heard in the distance. There were indistinguishable cries from one end of the train to the other. The guard held up his lantern, green-shaded. The six-thirty settled down to her work. The little lighted houses, most of them now untenanted, began once more their rolling march … The six-thirty was gone.

But, as yet, only the very first trickles of the black flood were over the bridge and outside Holmdale station. They were so tight packed, the units which went to the making of this flood, that speed, however passionately each unit undoubtedly desired it, was impossible. They surged up the stairs. At the head of the stairs they split into two streams, one flowing right and east and the other left and west. Two streams flowed across the bridge and down other stairs. At the foot of each staircase stood a harassed porter snatching such tickets as offered themselves and glancing, like a distracted nursemaid, at hundreds of green, square pieces of pasteboard marked ‘Season’.

The left-hand staircase leads into the main booking hall of Holmdale station and this hall is lighted. As the flood, after the first trickling, really surges into the hall, it is possible for the first time fully to realise that not only are the component parts of the flood human, but that these humans are not uniform. Look, and you will see that there are women where at first you would have been prepared to take oath that there had been nothing save men. Look again, and you will see that all the hats are not, as you first supposed, bowler hats and from the same mould, but that every here and there a rebellious head flaunts cap or soft hat. Look again, and you will see that the men and the women are of different height, different feature and perhaps, even, different habit. But you will look in vain for man or woman who does not carry a small, square, flat case.

The flood pours through the booking hall and out through the double doors into the clear, cold night. In the gravelled, white-fenced, semi-circular forecourt to the station, wait, softly chugging, two bright-lighted omnibuses looking like distorted caravans. Each of these omnibuses is meant to hold—as he who peers may read—twenty-seven passengers. Each, not less than two minutes after the flood has begun to break about their wheels, grinds off through the night with fifty at least. The rest of the flood, thinning gradually into trickles and then, at last, into units, goes off walking and talking. Their voices carry a little shrill on the cold, dark air and the sound of their boot-soles rings on the smooth iron road. Between the forecourt and the station is a dark expanse edged at its far sides by little squares of yellow light where the houses begin.

II

‘Coo!’ said Mr Colby. ‘Sorry we couldn’t get the bus, ol’ man!’

‘Not a bit. Not a bit,’ mumbled Mr Colby’s friend, turning up the rather worn velvet collar of his black coat.

‘Not,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that I mind myself. Personally, Harvey, I rather look forward to a nice, crisp trudge. Seems somehow to blow away the cobwebs.’

‘Yes,’ said Mr Harvey. ‘Quite.’

Mr Colby, having shifted his umbrella and attaché-case to his right hand, took Mr Harvey’s arm with his left.

‘It’s only a matter,’ said Mr Colby, ‘of a mile and a bit. Give us all the more appetite for our supper, eh?’

‘Quite,’ said Mr Harvey.

‘I wish,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that it wasn’t so dark. I’d have liked you to have seen the place a bit. However, you will tomorrow morning.’

Mr Harvey grunted.

‘There are two ways to get to my little place,’ said Mr Colby. ‘One’s across the fields and the other’s up here through Collingwood Road. Personally, I always go over the fields but I think we’ll go by Collingwood Road tonight. The field’s a bit rough for a stranger if he doesn’t know the ground.’ Mr Colby broke off to sniff the cold air with much and rather noisy appreciation. ‘Marvellously bracing air here,’ said he. ‘Didn’t you feel it as you got out of the train? You know we’re nearly five hundred feet up and really right in the middle of the country. Yes, Harvey, five hundred feet!’

‘Is that,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘so?’

‘Yes, five hundred feet. Why, since we’ve been here, my boy’s a different lad. When we came, a year ago, his mother—and his old dad too, I can tell you—were very worried about Lionel. You know what I mean, Harvey, he was sort of sickly and a bit undersized and now he’s a great big lad. Well, you’ll see him yourself … Here we are at Collingwood Road.’

‘Collingwood Road, eh?’ said Mr Harvey.

Mr Colby nodded emphatically. In the darkness, his round, bowler-hatted head looked like a goblin’s.

‘We don’t live in Collingwood Road, of course. We’re right at the other side of the place. More on the edge of the country. Our bedroom and the room you’re sleeping in tonight, ol’ man, look out right across the fields and woods. In the spring, as Mrs Colby was saying to me only the other day, it’s as pretty as a picture.’

Mr Harvey unburdened himself of a remark. ‘A good idea,’ said Mr Harvey approvingly, ‘these Garden Cities.’

‘Holmdale,’ said Mr Colby with some sternness, ‘is not a Garden City. You don’t find any long-haired artists and such in Holmdale. Not, of course, that we don’t have a lot of journalists and authors live here, but if you see what I mean, they’re not the cranky sort. People don’t walk about in bath-gowns and slippers the way I’ve seen them at Letchworth. No, sir, Holmdale is Holmdale.’

Perhaps the unwonted exercise—they were walking at nearly four miles an hour—coupled with the cold and bracing air of Holmdale—had induced an unusual belligerence in Mr Harvey. ‘I always understood,’ said Mr Harvey argumentatively, ‘that the place’s name was Holmdale Garden City.’

‘When you said was,’ said Mr Colby, ‘you are right. The place’s name is Holmdale, Harvey. Holmdale pure and Holmdale simple. At the semi-annual general meeting of the shareholders—Mrs Colby and I have got a bit tucked away in this and go to all the meetings—the one held last July, it was decided that the words Garden City should be done away with. I supported the motion strongly; very, very strongly! And fortunately it was carried.’ Mr Colby laughed a reassuring, friendly laugh and once more put his left hand upon Mr Harvey’s right arm. ‘So you see, Harvey,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that if you want to get on in Holmdale you mustn’t call it Holmdale Garden City.’

‘I see,’ said Mr Harvey. ‘Quite.’

They were now at the end of Collingwood Road—a long sweep, flanked by small, neat, undivided gardens and small, neat-seeming, shadowy houses. Beneath a street lamp—a curious and most ingeniously un-street-lamplike lamp—which was only the third that they had passed in the whole of their three-quarter mile walk, Mr Colby stopped to look at his watch.

‘Very good time,’ said Mr Colby. ‘Harvey, you’re a bit of a walker! I always take my time here and I find I’ve beaten last night’s walk by fully half a minute. Now we haven’t far to go. We shall soon be toasting our toes and perhaps having a drop of something.’

‘That,’ said Mr Harvey warmly, ‘will be very nice.’

They crossed the narrow, suddenly rural width of Marrowbone Lane and so came to the beginning of Heathcote Rise.

‘At the top here,’ said Mr Colby, ‘we turn off to the right and then we’re home.’

‘Ah!’ said Mr Harvey.

‘The only thing about this walk,’ said Mr Colby glancing about him in the darkness with the air of one who knows the place so well that clear vision is not required, ‘the only thing about this walk that I don’t like, is this bit. Of course you can’t see it, Harvey, but I assure you Heathcote Rise isn’t—well—isn’t, as you might say, worthy of the rest of Holmdale. I don’t think anyone could call me snobbish, but I must say that I think it rather extraordinary of the authorities to let this row of labourers’ cottages go up here. They ought to have kept that sort of thing for The Other Side.’

‘The other side,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘of what?’

‘The railway, of course,’ said Mr Colby. ‘You see, the idea is to have what you might call an industrial quarter one side of the railway and a—well—a superior residential quarter on this side of the railway. Very good notion, don’t you think, ol’ man?’

‘Splendid!’ said Mr Harvey.

‘Round here. Round here,’ Mr Colby, with increasing jocularity, swung Mr Harvey to his left. They entered the dark and box-hedged mouth of what seemed to be a narrow passage. They came out after ten yards of this into a small rectangle. So far as Mr Harvey was able to see, this rectangle was composed of small and uniform houses all ‘attached’ and all looking out upon a lawn dotted with raised flower beds. Round the lawn were small white posts having a small white chain swung between them. All the square ground-floor windows showed pinkly glowing lights. Mr Harvey wondered for a moment whether all the housewives of The Keep—he knew his friend’s address to be No. 4, The Keep—had chosen their curtains together.

‘Here we are! Here we are! Here we are!’ said Mr Colby in a sudden orgy of exuberance. He had stopped before a small and crimson door over which hung by a bracket a very shiny brass lantern. He released the arm of Mr Harvey and fumbled for his key chain, but before the keys were out the small red door opened.

‘Come in, do!’ said Mrs Colby. ‘You must both be starved!’

They came in. The small hall was suddenly packed with human bodies.

‘This,’ said Mr Colby looking at his wife and somehow edging clear, ‘is Mr Harvey. Harvey, this is Mrs Colby.’

‘Very pleased,’ said Mr Harvey, ‘to meet you.’

‘So am I, I’m sure,’ said Mrs Colby. She was a plump and pleasant and bustling little person who yet gave an impression of placidity. Her age might have been anywhere between twenty-eight and forty. She was pretty and had been prettier. She stood looking from her husband to her husband’s friend and back again.

Mr Colby, whose christian name was George, was forty-five years of age, five feet five and a half inches in height, forty-one and a half inches round the belly and weighed approximately ten stone and seven pounds. He had pleasing and kindly blue eyes, a good forehead and a moustache which seemed, although really it was not out of hand, too big for his face.

Mr Harvey was forty years old, six feet two inches in height, thirty inches round the chest and weighed, stripped, nine stone and eleven pounds. Mr Harvey was clean-shaven. He was also bald. His face, at first sight rather a stern, harsh, hatchet-like face, was furrowed with a myopic frown and two deep-graven lines running from the base of his nose to the corners of his mouth. When Mr Harvey smiled, however, which was quite frequently, one saw, as just now Mrs Colby had seen, that he was a man as pleasant and even milder natured than his host.

‘This,’ said Mr Colby throwing open the second door in the right-hand wall, ‘is the sitting-room. Come in, Harvey, ol’ man.’

Mr Harvey squeezed his narrowness first past his hostess and then his host.

‘You coming in, dear?’ said Mr Colby.

His wife shook her head. ‘Not just now, father. I must help Rose with the supper.’

‘Where’s the boy?’ said Mr Colby.

‘Upstairs,’ said the boy’s mother, ‘finishing his home lessons. It’s the Boys’ Club Meeting after supper and he wants to get the work done first.’

‘If we might,’ said Mr Colby with something of an air, ‘have a couple of glasses …’

Mrs Colby bustled away. Mr Colby went into the sitting-room with his friend. Mr Colby impressively opened a cupboard in the bottom of the writing desk and took from the cupboard a black bottle and a syphon of soda water. Mrs Colby entered with a tray upon which were two tumblers. She set the tray down upon the side table. She raised the forefinger of her right hand; shook it once in the direction of her husband and once, a little less roguishly, at Mr Harvey.

‘You men!’ said Mrs Colby.

Mr Colby and his guest lay back in their chairs, their feet stretched before the fire. In each man’s hand was a tumbler. They were very comfortable, a little pompous and entirely happy. To them, when the glasses were nearly empty, entered Master Lionel Colby; a boy of eleven years, well-built and holding himself well; a boy with an engaging round face and slightly mischievous, wondering blue eyes which looked straight into the eyes of anyone to whom he spoke. Lionel obviously combined in his person, and also probably in his mind, the best qualities of his parents. He shook hands politely with Mr Harvey. He reported, with some camaraderie but equal politeness, his day’s doings to his father.

‘Homework done?’ said Mr Colby.

Lionel shook his head. ‘Not quite all, daddy. I came down because mother told me to come and say how-do-you-do to Mr Harvey.’

Mr Colby surveyed his son with pride. ‘Better run up and finish it, son. Then come down again. What are you going to do at the Boys’ Club tonight?’

The round cheeks of Lionel flushed slightly. Lionel’s blue eyes glistened. ‘Boxing,’ said Lionel.

The door closed gently behind Lionel.

‘That,’ said Mr Harvey with genuine feeling, ‘is a fine boy, Colby!’

Mr Colby made those stammering, slightly throaty noises which are the middle-class Englishman’s way when praised for some quality or property of his own.

‘A fine boy!’ said Mr Harvey again.

‘A good enough lad,’ said Mr Colby. His tone was almost offensively casual. ‘Did I happen to tell you, Harvey, that he was top of his class for the last three terms and that the headmaster, Dr Farrow, told me himself that Lionel is one of the best scholars he’d had in the last twenty years? Not, mind you, Harvey, that he isn’t good at games. He’s captain of the second eleven and they tell me he’s going to be a very good boxer. I must say—although it isn’t really for me to say it—that a better, quieter, more loving lad it’d be difficult to find in the length and breadth of Holmdale.’

‘A fine boy!’ said Mr Harvey once more.

III

At nine o’clock in the Trumpington Hall, Master Lionel Colby had the immense satisfaction of having proved himself so immeasurably superior to his opponent, a boy three years older and a full stone heavier than himself, that Sergeant Stubbs had stopped the bout.

‘I only wish,’ said Lionel to himself, ‘that dad and mum had been there.’ ‘I’m sorry,’ said Lionel aloud to his cronies, with a self-condemnatory swagger quite delicious, ‘I didn’t realise I was hitting so hard.’

At nine o’clock in the Holmdale Theatre—a building so modern in conception, so efficient in arrangement, and so pleasantly strange in decoration that earnest Germans made special trips to England to see it—the curtain was going down upon the first act of the Yeomen of the Guard as performed by the Holmdale Mummers. With supers, the cast of the Yeomen of the Guard, as performed by the Holmdale Mummers, amounted to seventy-four. There were in the theatre somewhere between two hundred and fifty and three hundred people, two hundred and twenty-two of whom were relatives of the cast.

At nine o’clock in the library of The Hospice, which was the large house of Sir Montague Flushing, K.B.E., the chairman of the Holmdale Company Limited, Sir Montague himself, was concluding a small and informal speech to those six of his fellow directors who had, that night, dined with him. Sir Montague was saying:

‘… and so I think that we may, gentlemen, very fairly congratulate ourselves upon drawing near to the conclusion of a very successful year. It is true that this year, as in the past, we have been unable to pay any dividend upon Ordinary Shares. It is also true that we have had to mortgage a thousand acres of building land on the Collingwood site, but, in opposition to these two facts, we have the increased and ever increasing influx of citizens. We have the success of our (a), (b) and (d) building schemes and we have the satisfaction of knowing that before many more months are out we shall be a fully self-contained borough with an Urban District Council of its own.

‘I am sure you will join with me, gentlemen, in giving thanks to Mr Dartmouth for his untiring efforts towards this very desirable end. When I tell you that Mr Dartmouth is to be the Clerk to the new Urban District Council, nominally giving up his position as Secretary to the Company, I am sure that you will appreciate how very helpful the new situation may prove.’

Sir Montague sits down. There is no clapping because this is an informal meeting, but there is a hearty and hive-like bumble of appreciation. Sir Montague’s manservant—the only manservant in Holmdale as this is the only library—makes slow and steady round. The glasses of Sir Montague, the Managing Director, Mr Dartmouth, the Company’s Secretary who is soon to be Clerk to the Council, and the other Directors—Mr Archibald Barley, Colonel Fairfax, Mr Cuthbert Mellon, Mr Ernest May and Mr Charles E. Lordly—are filled. A prosperous enough gathering of men who have, in the manner of all big fish in small ponds, persuaded themselves that their pond is the world.

At nine o’clock in the Maxton Hall, which is on The Other Side, Mr James Wildman is concluding a speech to an earnest audience. Mr Wildman is saying:

‘… And now to come to the peroration of my remarks. I can only hope that I have done some little service to the cause, by making certain-sure that all of my audience tonight will be fighting heart and soul, tooth and nail for the Silk Workers. (Applause.)

‘Before I sit down I should like to add to my final and concluding remarks the final statement that before I sit down I should like to say that, in conclusion, and quite apart from my proper subject, it would give me great pleasure to add that I consider Holmdale Garden City (What’s that, Mr Chairman?). I beg your pardon, ladies and gentlemen, I should have said Holmdale, that I consider Holmdale to be a proper move in the right direction. It has not been my pleasure and privilege to visit this salubrious spot before this occasion of this, my auspicious visit tonight, but now that I have paid a visit to Holmdale Gar … I beg your pardon, Mr Chairman, to Holmdale, I feel that it would not be right for me to conclude my remarks and to sit down without expressing my appreciation of the very salubrious qualities of this … er … Holmdale. It seems to me that here you have pleasant homes for jaded workers; pleasant homes set in delightfully rusticating surroundings. It seems to me, in fact, that here you have the beginning of what some of our more educated friends would call the millennium. When I looked about me on my pleasant walk here with Mr Todd here up from the station to this hall where I was to address you tonight I took the opportunity of keeping—as I always do—my eyes open. What I saw was a very pleasant, clean and delightful town set down in the heart of England’s fair green countryside. It has been my painful lot, Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, to have most of my life’s work laid down in the paths of the great cities, and I cannot tell you, I cannot even hope to properly or even with any degree of truthfulness tell you how much I opened my eyes at this very aptly named Holmdale of yours. It is, if I may coin the phrase, Holmdale by name and Holmdale by nature. It is a home town of little, clean, nice, decent, orderly homes; homes for that backbone of England, the working man … God bless him!’

At nine o’clock in the Baden-Powell Drill Hall, Mr William Farthingale had amassed so many points in the Progressive Whist Drive, organised by the Holmdale Mothers’ Protective Aid Society, that it seemed almost certain that he would run away with the first prize of a massive pair of ebony and silver-backed hair brushes. At nine o’clock in No. 3, Pettifers Lane, Mrs Sterling was, not without grumbling, cooking the late supper of her husband who worked at the Holmdale Electricity Supply Company. At nine o’clock in No. 14, Prester Avenue, Mrs Tildesly-Marshall was announcing to the guests in her drawing-room that Mr Giles Freshwater would now sing—Miss Sophie May accompanying—Gounod’s ‘Ave Maria’, after which we will have a little bridge. At nine o’clock in Claypits Road, Miss Ursula Finch, the part proprietor and sole editor of the Holmdale Clarion, locked up the Clarion’s office. At nine o’clock in the surgery of No. 10 Broad Walk, Dr Arthur Reade was assuring the wife of Mr Fox-Powell, the solicitor, that there would be no addition to the family. At nine o’clock in Links Lane, Albert Rogers was kissing Mary Fillimore. At nine o’clock in the parlour of The Cottage in High Collings, Mr Julius Wetherby was having his nightly quarrel with Mrs Julius Wetherby. At nine o’clock in The Laurels Nursing Home, which was on the corner of Collingwood Road and Minters Avenue, Mrs Walter Stilson, wife of the Reverend Walter Stilson, was being delivered of a son. At nine o’clock in the drawing-room of No. 4 Tall Elms Road, Mrs Rudolph Sharp, having been assailed three times that day by an inner agony, was drafting, for the eye of her solicitors, a codicil to her will. And at nine o’clock down by the station, Percy Godly, the black sheep son of Emanuel Godly, the tea-broker, whose house, just outside the bounds of the town at Links Corner, was the envy of all Holmdale, was missing the last train to London.

It was at ten-fifteen that Mrs George Colby first evinced signs of more than normal perturbation. She and her husband and the long and saturnine-seeming Mr Harvey had finished their last rubber of wagerless dummy.

Mrs Colby got suddenly to her feet. Her chair fell with a soft crash to lie asprawl upon the blue carpeted floor. In a voice which sounded somehow as if she were having difficulty with her breath, Mrs Colby said:

‘George! I—I—don’t like it! What can’ve happened to him? George, it’s a quarter past ten!’

Mr Colby looked at his watch. Mr Colby looked at the clock upon the mantelpiece. Mr Colby consulted Mr Harvey. Mr Colby, after two minutes, came to the conclusion that a quarter past ten was irrevocably the time.

‘Don’t you remember, dear,’ said Mr Colby, ‘that time when he didn’t come back until just before ten. The boxing had gone on rather longer than usual. You remember I wrote a stiff P.C. to that Mr Maclellon about it—’

‘I know. I know,’ said Mrs Colby, stooping down and picking up her chair. ‘I know, but it isn’t a few minutes to ten now, George. It’s a quarter past!’ She suddenly left off fumbling with her chair and as suddenly was gone from the room. The door slammed to behind her.

‘I expect,’ said Mr Harvey, looking at his host, ‘that the lad’s up to some devilment. A fine lad that and, personally, Colby, I’ve no use for a boy that hasn’t a bit of the devil in him. I remember when I was a lad—’

‘Clara,’ said Mr Colby, ‘gets that worked up.’ He looked at his watch again. ‘All the same, Harvey, ol’ man, it’s late for the nipper. Have a drink? I’d go out only I expect that’s where Clara’s gone. She’ll find him all right playing Tig at the end of the street or something.’

‘Yes,’ said Mr Harvey, and laughed with due heartiness.

The door opened again. A small rush of air blew cool upon the back of Mr Colby’s neck. Mr Colby turned. He saw Mrs Colby. She wore a coat about her plump and admirable shape and a hat pulled anyhow upon her head. But she did not go out. Instead, she dropped in the chair which just now she had left, and, gripping her hands with tightly interlocked fingers one about the other, sat breathlessly still and said:

‘I don’t feel up to it, George. You go and see.’

George looked at his Clara. ‘Tired, my dear?’ said George. ‘We’ll go instead, eh, Harvey?’

‘A breath of fresh,’ said Mr Harvey facetiously, ‘is just what the doctor ordered.’

There was a hard, black frost. After the warmth of the little parlour, the cold air outside caught at their breath. They both coughed.

‘A snorter of a night!’ said Mr Colby.

‘It is,’ agreed Mr Harvey, ‘that!’

They turned left out of the little red door. They turned up the path to the narrow passage which joins The Keep to Heathcote Rise. Out of the passage Mr Colby turned to his right.

‘The Trumpington Hall,’ said Mr Colby, ‘is just up here. Matter of three or four hundred yards.’

‘Ah!’ said Mr Harvey. ‘Quite.’

They did not get so far as the Trumpington Hall. There are two street lamps in the quarter mile length of Heathcote Rise. The first was behind Mr Colby and Mr Harvey as they left the mouth of The Keep. The second was about two hundred yards from the mouth of The Keep. They were walking upon the raised side path and as they came abreast this lamp, Mr Colby, as seemed his habit when passing street lamps, paused to take out the great silver watch. Mr Harvey, halting too, happened to glance over Mr Colby’s plump shoulder and down into the road.

‘My—God!’ said Mr Harvey.

‘What’s that!’ said his companion sharply. ‘What’s that!’

But Mr Harvey was gone. With an agility which would at any other time have been impossible to him, he had dropped down into the road and was now half-way out into the broad thoroughfare. Mr Colby, despite the cold, bony fingers of fear clutching at his vitals, scrambled after.

Mr Harvey was on his knees in the middle of the road, but he was within the soft, yellow radiance cast by the lamp. He was bending over something.

Mr Colby came trotting. Mr Colby halted by Mr Harvey’s shoulder.

Mr Harvey looked up sharply. ‘Get away!’ he said. ‘Get away!’

But Mr Colby did not get away. He was standing like a little, plump statue staring down at the thing beside which Mr Harvey knelt.

‘Oh!’ said Mr Colby in a whisper which seemed torn from him. And then again: ‘Oh!’

What he looked at—what Mr Harvey was looking at—was Lionel.

And Lionel lay an odd, twisted, sturdy little heap on the black road and where Lionel’s waistcoat should have been was something else. Mr Harvey picked up one of Lionel’s hands. It was cold like the road upon which it was lying.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_7774285d-8551-512b-898d-23e1b223fef8)

I

THE next day—Saturday—was a windless day of hard frost and bright sunshine. The sort of day, in fact, which had been used to fill the placid heart of Mr Colby with boyish joy. But now Mr Colby’s heart was black.

Mr Colby sat, a huddled and shrunken little figure, at the table in his tiny dining-room. The chair upon the other side of the table was occupied by Miss Ursula Finch, the editor and owner of the Holmdale Clarion. Miss Finch was small and neat and brisk. Miss Finch’s age might have been thirty-three but probably was ten years more than this. Miss Finch was severely smart in a tweedy-well-tailored manner. Miss Finch’s pencil was busy among the rustling pages of her notebook, for Miss Finch was her own star reporter. But the eager, piquant face of Miss Finch was clouded with most unbusinesslike sympathy. And although her questions rattled on and on and her pencil flew, the eyes of Miss Finch were suspiciously bright.

It seemed suddenly to Mr Colby that he could not stand any more. Miss Finch had asked him a question. He did not answer it. He sat staring across the little room at the yellow distempered wall. First, all those policemen asking questions. What time did he leave? What time did you expect him back? Where was he going? What was he doing? Why was he doing it? What time did you start to look for him? Did anyone go with you to look for him? Where did you find him? How did you find him? Do you know anyone who bears enmity against yourself or him? If so, why? If not, why not? How? Who? Where? What? When? And now, this woman—although she was nicer than the policemen—now this woman, asking her questions. The same questions really, only put differently and more, as a man might say, intimate …

Mr Colby thought of the bedroom immediately above this room where he sat; the bedroom where, on the double bed, Mrs Colby lay a huddled and vacantly staring heap …

Mr Colby got to his feet. His chair slid back along the boards with a grating clatter. He said:

‘I’m sorry, miss. I can’t tell you any more. I want—I want—’ Mr Colby shut his mouth suddenly. He sat down again with something of a bump and remained sitting, his folded hands squeezed between his knees. He looked at the floor.

Miss Finch shut her note-book with a decisive snap and put round it its elastic band. She rose from her chair. Automatically Mr Colby, a well-mannered little person, got to his feet. Miss Finch came round the table in an impulsive rush. ‘I ought,’ said Miss Finch, ‘to have something awful done to me for worrying you, Mr Colby, upon such a dreadful day as this must be for you. But I would like you to understand, Mr Colby, that however much of a ghoulish nuisance I may seem, I may really be doing something to help. It may not seem like that to you at the moment. But it really is. You see, Mr Colby, nowadays the Press, by throwing what you might call a public light on things, helps authorities to … to … to find the monsters responsible for—’

‘Oh, please!’ said Mr Colby, holding out his hand as if to protect himself from a blow.

Miss Finch, with an impulsive gesture, seized the hand in both of hers and pressed it. ‘You poor man!’ she said.

Mr Colby withdrew his hand. Mr Colby opened the door for Miss Finch. In the hall Miss Finch halted and collected her stubby umbrella and tucked it martially beneath her left arm. She said:

‘If there is anything I can do for you or Mrs Colby—in a purely private capacity, I mean, Mr Colby—I do hope you will let me know … You wouldn’t like me, I suppose, to run up and sit with Mrs Colby for a little while? It would only be a little, because I’m so busy …’

Mr Colby shook his head dumbly. He opened the street door and shut it, a second later, upon the well-tailored back of Miss Finch. He wandered back to his dining-room and sat down once more at his dining-table and sighed and swallowed very hard and put his head in his hands.

II

‘Do they,’ asked Sir Montague Flushing of his manservant, ‘insist upon seeing me personally?’

Spender bowed gravely. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘And you have put them in …?’ said Sir Montague.

‘In the library, sir.’

Sir Montague blew out his cheeks and frowned. Sir Montague paced up and down the carpet. He said at last, half to himself:

‘These newspaper men are a public nuisance!’

‘Should I, sir,’ suggested Spender, ‘tell them that you are too busy to see them?’

‘No,’ said Sir Montague. ‘No. No. No. I suppose I must see ’em. What papers did you say they came from?’

‘One of the—er—gentlemen, sir,’ said Spender, ‘stated that he represented The Evening Mercury. The other was from The Wire.

‘I see. I see,’ said Sir Montague.

(Extract from The Evening Mercury, dated Saturday,

24th November.)

THE HOLMDALE MURDER

etc., etc.

(From our Special Correspondent.)

Holmdale, Saturday

Stranger and stranger grows the mystery of the murdered schoolboy, whose body was found at ten o’clock last night in the middle of a peaceful roadway in Holmdale Garden City. The problem that faces the police is no small one. The boy—Lionel Frederick Colby, of 4 The Keep, Holmdale—had left home at about 7.30 p.m. to visit the Boys’ Club, whose meetings are held in the Trumpington Hall. He had been in good spirits when he left home and had arrived at twenty-five minutes to eight at the Boys’ Club. Here he had spent the evening in the usual way, and had notably distinguished himself in the boxing competition which was held that night. He left the Hall with a number of companions when the Club meeting closed at 9.20. Half-way back towards his home—The Keep, which is off Heathcote Rise, is not more than five or six minutes’ walk from the Hall—Lionel remembered, according to two of his friends who have been interviewed by the Police, that he had left his gymnasium shoes and sweater behind. His companions had tried to dissuade him from going back, telling him that he would not find the place open. Lionel, who was a boy of great determination, stated that he had promised his mother not to forget the sweater as she wanted to wash it the next day. One of the boys, Charles Coburn (13) of 28 Lochers Avenue, Holmdale, stated to the police that he remembered Lionel saying that he would be able to climb in at a window. He left Coburn and the other boys in the middle of Heathcote Rise at approximately 9.25. At about a quarter past ten, Mr Colby, the boy’s father, together with a guest (Mr Harvey) went out to see whether they could find Lionel. They walked down Heathcote Rise towards Trumpington Hall, but half-way on this journey—beside a street lamp—they made the appalling discovery.

Police Theories

As was reported in earlier editions, the wound which caused Lionel Colby’s death had apparently been made by a very sharp implement, probably a long knife. The stomach had been slit open from bottom to top. Death must have been instantaneous. The night was hard and frosty, and it was not possible therefore to find any trace such as footmarks, etc. The police are certain, however, that the murder was done on the spot where the body was found, as all traces of blood, etc., point to this conclusion.

People resident in the houses which line both sides of Heathcote Rise have, of course, been questioned, but none of them can testify to having heard any disturbance. Dr F. W. Billington of Holmdale, who acts as Police Surgeon to the Holmdale and Leewood district, examined the body at 11.30 p.m. last night. Dr Billington gives it as his opinion that life had not then been extinct for more than two hours. The police are of the opinion that Lionel was killed on his return from the gymnasium whence, as all windows were locked, he had been unable to fetch the shoes and sweater. The police are completely puzzled by the absence of a motive for such a terrible crime.

Mr and Mrs Colby are extremely popular in their own circle and have no enemies. Lionel, too, was a very well liked boy. He had no enemies at school, and was a prominent and popular member of the local Boys’ Club and also of the Holmdale troop of Sea Scouts. At present the police theory is that the crime was committed by a pervert, or homicidal lunatic.

They have, of course, several clues which they are following up.

Mrs Colby, Lionel’s mother, is prostrate from shock, but I managed to secure an interview with Mr George Colby, the father. He could give me no help, but stated that all he lived for now was to see the capture of the wretch who had robbed him of his only child.

Grave Concern in Holmdale

Sir Montague Flushing, K.B.E., the prominent Managing Director of the Holmdale Company Limited, stated in an interview today that he was himself deeply and terribly shocked by the tragedy.

‘How such a thing,’ said Sir Montague, ‘could take place in this happy little town of ours is utterly beyond my imagination!’

Sir Montague added that he would be only too grateful if the London Press would give full publicity to his statement, ‘that not only the citizens of Holmdale, but mothers and fathers throughout England could rest assured that the Holmdale Company (who are, of course, the proprietors of the whole Garden City) would do everything in their power to aid and assist the regular authorities in tracking down the author of the outrage.’

III

That was in The Evening Mercury late afternoon edition. Similar writings were in the other evening papers. The station, usually deserted upon a Saturday afternoon, was besieged at the time of the paper-train’s arrival by a crowd fully a third as big as that which upon weekdays left the six-thirty. Within four minutes of the arrival of the papers, the book-stall had not one left.

There was, in Holmdale today, only one topic of conversation. Holmdale was duly horrified. Holmdale was duly sympathic. Holmdale was inevitably a town in which every third inhabitant was satisfied that, given the job, he could lay his hands upon the criminal in half the time which it would take the police. Holmdale was also, though it would have vilified you for making the allegation, very delightfully excited. It was not every day that Holmdale came into the public eye. Holmdale looked forward to Monday morning when once more ‘up in town’ it would be the centre of a hundred interested groups all asking— ‘I say, don’t you live in that place where that boy’s been killed?’

Something, in short, had happened in Holmdale. Holmdale was News. Holmdale was on the Front Page.

The papers came down on Saturdays by the train arriving at Holmdale at 6.20. By 6.45 all Holmdale knew what London was saying of it. But all Holmdale did not know that at 6.45, Holmdale’s postman was carrying in his bag three letters for which the London Press would have given the heads of any of their reporters. The first of these letters was delivered at The Hospice. The second at The White Cottage, Heathcote Rise, which was Holmdale’s Police Station, and the third at the office of the Clarion in Claypits Road. In that order—because that was the way the postman went round—they were delivered, and in that order they were read.

Sir Montague Flushing, going through his evening’s post, came suddenly across a yellow linen paper envelope. He was a man who always speculated about a letter before he opened it, and this letter he turned that way and the other between his fingers. He did not know the paper. He did not know the minute, backward-sloping writing. He had never seen ink so shinily black. He slipped an ivory paper knife under the flap of the envelope …

He found himself staring, with wide and startled eyes, at a single sheet of paper of the same texture and colour as the envelope. Upon this sheet was written, in the same ink and writing, but with larger characters:

My Reference ONE

R.I.P.

Lionel Frederick Colby,

died Friday, 23rd November …

THE BUTCHER

CHAPTER III (#ulink_92928456-7341-5373-a457-82e0c6cdf00c)

I

THE Chief Constable looked at Inspector Davis, then from that unreadable face down again to his blotting pad where there lay, side by side, three quarto sheets of yellow paper, each bearing in its centre a few words written in a dead black and shining ink.

The Chief Constable cleared his throat; shifted uneasily in his chair.

‘What do you think, Davis?’ said the Chief Constable, ‘Hoax?’

Inspector Davis shrugged. ‘May be, sir, may be not. One can’t tell with these things.’

The Chief Constable thumped the desk with his fist so that the glass ink-bottles rattled in their mahogany stand. He said:

‘But damn it, man, if it isn’t a hoax, it’s …’

‘Exactly, sir,’ The Inspector’s voice and manner were unchanged. His cold blue eyes met the frowning puzzled stare of his superior.

The Chief Constable picked up the centre sheet and read aloud to himself, for perhaps the twentieth time this morning: ‘My reference One. R.I.P. Lionel Frederick Colby, died Friday, November 23rd. The Butcher.’

‘Oh, hell!’ said the Chief Constable, ‘I never did like that damn Garden City place.’

Inspector Davis shrugged. ‘So far it hasn’t been any trouble to us, sir,’ he said.

‘But,’ said the Chief Constable interpreting the Inspector’s tone, ‘you think it’s going to be.’

‘May be,’ said Davis. ‘May be not.’

The Chief Constable exploded. ‘I wish to God you’d be less careful! … Now, let’s get down to business. I suppose you’ve tried to trace this paper.’

Davis nodded. ‘This paper is what they call Basilica Linen Bank, sir. It’s purchasable at any reputable stationers. It’s expensive and it’s only made in that yellow colour for Christmas gift boxes. The number of Christmas gift boxes of the yellow variety sold since the first Christmas display about three weeks ago is so large that we can’t get any help that way.’

The Chief Constable held up a hand. ‘One moment, Davis, one moment. Is this stuff on sale at the Holmdale shop? What do they call it?’

‘The Market, sir,’ said Davis. ‘Yes, it is. But not the yellow variety, therefore this paper was bought somewhere outside Holmdale.’

The Chief Constable scratched his head. ‘Post mark?’ he suggested without hope.

‘The letters were post-marked 10.30 a.m. Holmdale.’

‘So that,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘they were posted actually in the place itself, on the morning after the crime was committed and were delivered that same evening?’

‘That, sir,’ said Inspector Davis, ‘is correct.’

‘And,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘we’ve no more idea of who cut this boy up than the man in the moon!’

Inspector Davis shook his head. ‘None, sir. In fact, so far as we can see, the man in the moon’s about the most likely person.’

‘I can’t,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘give you a warrant for him.’ He dropped his elbows on his desk and his face into his hands. He said after a moment,

‘Damn it, Davis. We can’t sit here joking about this!’

‘No, sir,’ said Davis.

Once more the Chief Constable thumped the desk so that the ink jars rattled.

‘We’ve got,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘to do something.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Davis.

‘What the hell,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘are we doing?’

For the first time Davis’s face showed sign of embarrassment. He shuffled his feet. He cleared his throat.

‘Of course, sir,’ said Davis, ‘we’re making careful enquiries …’

The Chief Constable exploded. ‘For God’s sake is it necessary to work that stuff off on me?’

Inspector Davis smiled, a faint, embarrassed smile. ‘There’s nothing else, sir,’ he said, ‘to say … If only we could find someone that could have any possible reason for wanting this boy out of the way …’

‘I know,’ said the Chief Constable wearily, ‘I know. Well, there’s nothing more I can say, Davis. Carry on as best you can. Only for God’s sake get a pair of handcuffs on to somebody before we have the whole countryside about our ears.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Davis.

The telephone bell by the Chief Constable’s table rang shrill.

‘Who’s that? …’ said the Chief Constable, ‘Yes … Martindale speaking. Oh, yes, Jeffson …What? … Yes … Go on, yes … Where? What time? … Good God! All right, I’ll send … Eh? What’s that you say? … Just read that over again, will you. Slowly, while I write it down.’ He picked up a pencil; scribbled to the telephone’s dictation upon his blotting pad; looked at what he had written; spoke again into the receiver: ‘All right, I’ve got that.’ His voice was no longer astonished, but weary, and with something of fear beneath its weariness. He spoke again: ‘Yes … Yes … I should think they would. Well, we’ll do what we can as quick as we can. Ring off now, will you. Stay where you are and I’ll let you have a word within half-an-hour.’ He hung up the receiver and, with an abstracted air, lifted the telephone and placed it at the edge of his desk. He looked at Davis for so long and in such pregnant silence that at last Davis was forced to break it. He said:

‘What was that, sir?’

‘That,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘was Jeffson. You know Jeffson, I think, Davis. Jeffson, from Holmdale?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Davis, half rising from his chair; then throwing himself firmly into it again.

‘Jeffson,’ said the Chief Constable, very slowly, ‘was telephoning to tell me that at 9.15 this morning, three-quarters of an hour ago, Davis, a man called Walters, who’s a milk-roundsman in Holmdale, saw a small car—a Baby Austin—standing at the end of one of the roads. He would have taken no interest in this car, except that as he passed and happened to glance down into it from his float, he saw what at first sight looked to him like a bundle of old clothes. He thought no more about it—for the moment.’ The Chief Constable’s words were coming now slower and slower: it was not so much that he was seeking dramatic effect as that he was, it seemed, trying to order his own thoughts. ‘But, Davis, he went back the way he had come, and as he got abreast of the Baby Austin, he looked down into it again … And he saw that what he had thought was a bundle of old clothes, was a bundle of new clothes … with something inside ’em. What was inside them, Davis, was a girl—a girl called Pamela Richards …’ The Chief Constable paused. The Chief Constable looked hard, over his hands which played now with a pen-holder, at Davis.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Davis.

‘Pamela Richards,’ said the Chief Constable, ‘was dead. Pamela Richards had been slit up the stomach in just the way that two days ago Lionel Colby was slit up the stomach …’

Davis’s lips, beneath his tight and tidy waxed moustache, pursed themselves. There came from them the ghost of a long drawn-out whistle of amazement.

The Chief Constable nodded. ‘Exactly, Davis. Only more so.’ The Chief Constable leant forward, pointing the end of the pen-holder at the Inspector. ‘And, Davis,’ he said, ‘almost at the moment when this milkman, Walters, was finding the body, three letters—letters like this’—here the Chief Constable tapped upon the centre of those three yellow sheets which lay upon his blotter—‘letters like this were being read by Flushing, Jeffson and the Editor of the Holmdale Clarion—letters, Davis, which were unstamped, and which must have been delivered by hand during the night.’

‘Was that letter, sir,’ said Davis, eagerly leaning forward in his chair, ‘what you were scribbling down on your blotter?’

‘It was,’ said the Chief Constable. ‘I will read it to you. It was set out just like these here. It said:

My Reference Two. R.I.P. Pamela Richards died Sunday, 25th November. And it was signed …’

‘The Butcher,’ said Davis.

II

‘What’s this? What’s this?’ said Percy Godly. ‘What’s this? What’s this?’

The boy with the red brassard of the Holmdale Clarion pushed forward the bundle of sheets which he held. ‘Special,’ said the boy. ‘Special extra. All about the Butcher.’ And that was in the official wire. ‘Blime, sir,’ said the boy, ‘ain’t it torful!’ And that was in the boy’s own voice.

‘Isn’t what,’ said Percy Godly, ‘torful?’

He pushed sixpence into the boy’s hand and waved away the change and snatched one of the broadsheets. He leaned against the corner of one of The Market windows and looked down at his purchase. He saw, in staring headlines two inches deep:

WHO IS THE BUTCHER?

HOLMDALE PANIC STRICKEN.

IS OUR CITY TO BE ANOTHER DÜSSELDORF?

THE BUTCHER’S SECOND LETTER.

PROMINENT LEADER OF HOLMDALE’S YOUNGER SET

DONE TO DEATH.

WHAT IS BEHIND THESE MURDERS?

Editorial Office, Claypits Road

This morning, at 9.15 a.m. Richard Henry Arthur Walters, a milkman in the employ of The Holmdale Market Limited, driving in the course of his rounds down New Approach, off Marrowbone Lane, saw a motor car—a small motor car of the ‘Baby’ type—standing, apparently deserted, in the semi-circular sweep at the head of the Approach. As he passed, what Walters thought a peculiar bundle in the front seat of the car attracted his attention and later, as he returned, passing the car once more, this bundle again attracted his attention. So much so, that he halted his horse, got off the milk float, and investigated.

Horribly Mangled Body

To Walter’s surprise and horror, he found that what he had thought was a ‘bundle’ was, in reality, the body of that well-known and charming young member of Holmdale’s ‘Upper Ten’—Miss Pamela Richards—the daughter of Mr and Mrs Arthur Richards, Sunview, Tall Elms Road. Walters discovered immediately that Miss Richards was not only dead, but that she had been dead for a considerable time. The injuries which had led to her death were almost identical with those which led to the death of that poor lad Lionel Colby, whose mother, the Clarion learns with regret, is likely to become dangerously ill with brain fever, brought about by her grief.

Police Activity

Official enquiries into the circumstances of Miss Richard’s death have elicited the following facts:

(1) That in the opinion of the Police Surgeon, Dr Billington, Miss Richards had been dead, when Walters found her, for at least eight hours.

(2) That Miss Richards, on the preceding evening, had left the house of Mrs Rudolph Sharp in Tall Elms Road, after a bridge party, at 12 midnight.

(3) That Miss Richards, at Mrs Rudolph Sharp’s request, had spent some time in transferring to their various homes those of Mrs Rudolph Sharp’s guests who either had no motor cars, or who had not brought their motor cars.

(4) That the last known person to see Miss Richards alive was the last of Mrs Sharp’s guests that she carried home—Mr Henry Warburton of 5 Oak Tree Grove.

(5) That Miss Richards had upon the day before broken off an engagement of marriage.

(6) That Miss Richards both throughout the evening and at 12.10 when she bade good-night to Mr Warburton and his family, had seemed in the best of spirits and far from anticipating evil fortune.

(7) That Miss Richards had, so far as her parents and immediate friends and acquaintances can vouch-safe, no enemy whatever in the world.

Ex-fiancé

It is rumoured that Miss Richard’s ex-fiancé is a well-known figure in Holmdale, but that the engagement was broken off by mutual rather than individual arrangement.

Police Theories of the Crime

In a long interview which our special representative had this morning with Inspector Davis of the County Constabulary, who is in charge of this and the Colby case, we learn that three letters signed, ‘The Butcher,’ were received this morning referring to the death of Miss Richards. These letters, except that the reference was two and the name—that of Miss Richards—was different, were identical in other respects with the letters received after Lionel Colby’s death. Inspector Davis was very frank with our representative. He pointed out that in this case of murder without apparent motive, investigation must necessarily be slower at the start than in the case where a motive or motives are immediately visible. His considered theory of how the crime actually took place is as follows:

Miss Richards—after taking Mr Warburton home—was proceeding towards her own domicile in Tall Elms Road, via High Collings, Marrowbone Lane and, as a short cut, New Approach. At the corner of New Approach (at the spot where the car was found this morning) it is the police theory that she was hailed and stopped the car, when the murderer—leaning into the car upon some pretext such as asking the time or the way—must have struck at her, killing her instantaneously and fearfully mutilating her in the same way that Lionel Colby was mutilated, namely, by terribly slitting her stomach. There can be no doubt, fortunately, that death was instantaneous, and therefore practically painless.

Police enquiries have ascertained, Inspector Davis told us, that at that time all the households of the occupied houses in New Approach were abed. A small car of the type owned by Miss Richards does not make much noise and none of the occupants of New Approach heard a sound. There are no street lights in New Approach, and after the dastardly murder had been committed, there was nothing to prevent the malefactor from calmly and cold-bloodedly going quietly upon his way.

Bereaved Family

The Clarion learns with deep regret that Mrs Richards, Miss Pamela Richard’s mother, is critically ill owing to the terrible shock imposed by her daughter’s untimely end. Mr Richards also was prostrate with shock. It is truly terrible to think how these tragedies affect, not only their victims, but also those whose loved and adored ones have been so suddenly, and as it were, by some all powerful demon, snatched from them in such a diabolic and undetectable way.

Mr Percy Godly, a little whiter than usual about his jowls which were so like gills, crunched the single sheet Clarion special into a hard ball; threw it viciously into the gutter; raised himself from his leaning posture and walked, a thought unsteadily, away. He passed in his walk the whole long green-painted front of The Market, Holmdale’s one shop, and, at this time every morning, Holmdale’s social centre.

A man stepped into Mr Godly’s path; a man who said:

‘Hullo, Godly. I say, Godly old man, I am damn sorry. Dreadful business!’

Mr Godly apparently did not hear this man. He side-stepped and walked on, his eyes fixed in a wide and clear stare. Mr Godly faced, at the far end of The Market, a group of young matrons who stood with neat and busily wagging heads, and talked together at the top of their voices, the subject for once being, in every case, the same. From this group the youngest matron detached herself and rushed towards Mr Godly with hand outstretched as if to clutch him by the arm. But, still staring with that glazed look before him, he twitched the arm away before the hand could descend upon it, and walked steadily on.

The young matron stared after him. ‘Well!’ she said, and went back to her group. The heads of the group had turned to follow Mr Godly’s progress until at the corner by Holmdale’s Inn, The Wooden Shack, he disappeared from sight.

‘Poor Percy!’ said the youngest matron. ‘I don’t care what you say! I think that when Pam broke off the engagement it hit him very hard.’

‘Poor Percy!’ said the second youngest matron indignantly. ‘Poor Percy, indeed! Poor Pamela, I say! Poor darling Pam!’

‘I say!’ said another, with something in her voice which brought all heads round to her and stilled the chattering mouths. ‘I say! Have any of you thought about this? I’ve only just realised that I haven’t. First that boy—that was awful—and then Pamela. They’re dead! Do you understand? They’ve been killed! They’ve … they’ve … There’s some inhuman thing going about that … that …’ She stopped. She caught her breath. Her eyes were wide. White teeth caught at her lower lip. She suddenly burst into a peal of sound bearing some resemblance to laughter, but having in it no mirth.

The youngest matron put her fingers to her ears. ‘Oh, don’t!’ she said.

The red brassarded boy came running up to the group. Twenty yards from them he began to chant. ‘Special! Special! Extra! Clarion Special! All about the Butcher!’

‘How dreadful!’ The eldest matron fumbled in her purse. ‘Here, boy. Give me one. How much?’

‘Tuppence,’ said the boy.

He had, it appeared, six copies left. The youngest matron was left without one. The previous record circulation of the Clarion for one week, had today with this special and unprecedented daily edition, not only doubled, but trebled itself. Holmdale was excited and more excited. But Holmdale was beginning to wonder whether excitement was so desirable as forty-eight hours ago it had seemed.

III

The Holmdale Theatre is in the Broad Walk. Facing it across the white, wide roadway and the railed-off stretch of turf and rose trees, is the red brick building which houses the offices of The Holmdale Company Limited.

At nine o’clock upon Monday, the 26th November—the evening of the day upon which Pamela Richard’s body was discovered—there was held, in the Board Room in these offices, a special meeting of Directors and others convened by Sir Montague Flushing himself.

Round the long table in the Board Room sat nineteen persons: Sir Montague, the five Directors of the main Holmdale Company, and the eight Directors of the associated and subordinate companies. There were also present Major Robert Wemyss John, who was honorary yet active Captain of Holmdale’s surprisingly efficient fire brigade; the Hon. Ronald Heatherstone, who was Private Secretary to Lord Bayford, upon whose property half of Holmdale was built; Colonel Grayling, head of the Holmdale Branch of the County Special Voluntary Constabulary; Miss Finch to represent the Press, and Arthur Steele, Sir Montague’s Private Secretary, to take notes of the proceedings.

The meeting had begun at seven-thirty. Now, an hour and a half later, it was drawing to its close. Sir Montague was speaking, and speaking, for once, without that pomposity which until today all those gathered about the table had thought part of the real man. He was saying:

‘… I take it then, gentlemen, that we are fully in agreement that as from tomorrow, unless by tomorrow night the Police have laid their hands upon this … this fiend, we’ll take the steps we’ve been discussing … If you have got them down, Steele? … Thank you … I think I’ll read over these points, just to make sure there’s no misunderstanding. First, Colonel Grayling, if he gets permission from the authorities, will have every road patrolled by one or more special constables, in addition to the regular constables who will be so employed. Second, Captain John will provide additional patrolling help out of his volunteers. Third, you, Mr Heatherstone, will obtain, if possible, Lord Bayford’s permission to use some of his outdoor staff, such as gamekeepers, for patrolling the entrances to and exits from the city, so that all incomers and outgoers after dark may be interrogated. Fourth, Miss Finch will issue another special edition of the Holmdale Clarion tomorrow, in which it will be clearly stated that the Holmdale Company are prepared to pay a reward of £500 for information leading to the capture of the … the … murderer. Are we all agreed upon that, gentlemen?’

Sir Montague seemed somehow less portly than usual and certainly less sure of himself and his own greatness as he looked round the table. There was something not without pathos in the anxiously out-thrust face; something almost pitiful in the man’s pallor and uncertainty; something certainly admirable in his earnestness. There were murmurs of assent.

‘You needn’t worry about my end,’ said young Heatherstone heartily. ‘Bayford’ll lend you all his men. If he doesn’t, I’ll send ’em along without asking him.’

‘I’ll get a rush edition out before noon, if I can, Sir Montague,’ said Miss Finch, and rose and fumbled beneath her chair for the perpetual umbrella.

‘I’ll get permission for the Specials all right and enroll a devil of a lot more.’ This in a growl from Grayling.

‘Thank you. Thank you,’ said Flushing. ‘Well, gentlemen, I’m sorry to have kept you so long.’ He glanced at his watch. ‘I see it’s already well past a normal dinner time …’

There was a general shuffling as chairs scraped back over the thick carpet and a sudden muddled hum of many small conversations as men struggled into their coats.

Steele threw open the double doors leading from the Board Room to the hallway. Thirty-eight feet clattered along the hall and so to the main doors and the flight of steps leading down to the pavement. The porter, expectant of tips, flung open the doors. The first rank shivered a little as the cold air struck their faces. The night was dark, but stars blazed in a black and moonless sky. The frost had held and there was a chill wind from somewhere in the north-east. Light, broken into a hundred little shafts by the bodies of the small crowd, flooded out from the hall and stabbed fingers at the darkness. Twenty-five yards away, straight opposite, the red and yellow signs across the face of the theatre winked cheerfully and a yellow rectangle of light poured through the glass doors of the portico.

Young Heatherstone tightened his muffler and turned up the collar of his ulster. He said to Grayling beside him:

‘Looks pretty cheerful, what? Hardly as if there was a … Jumping Gabriel, what’s up!’ The sudden change in his tone from one of idle pleasantness to one of urgent and vehement wonder brought a dozen eyes to peer in the direction of his pointing arm. From out of the theatre’s portico there had rushed suddenly a man in the theatre’s green and gold and scarlet uniform; a man hatless and to judge by his manner distraught; a man who, arrived upon the pavement, looked with quick turnings of his whole body to his right and to his left, and then, standing half crouched, put to his lips a whistle whose shriek throbbed across the cold, dark air.

‘What the devil!’ said Heatherstone, and was gone, crossing the roadway in four strides. He took the railings to the grass in a leap and arrived by the side of the man who whistled before any of his companions had moved a foot. The first few of them to cross the road and the grass saw him, after urgent and gesticulating talk with the commissionaire, disappear at a run into the portico. The commissionaire, turning suddenly, made off to his right at a long, loping run.

Grayling was the first to reach the theatre. He pushed open the heavy swing door which still vibrated with Heatherstone’s entry. In the vestibule he found the beginnings of a white-faced and gaping crowd. From this he singled out a face—a face whiter even than those which surrounded it, but a face beneath the cap of green lace worn as part of their uniform by the women who serve in the theatre. A man of sixty-five, but a man, Grayling, who knew both what he wanted and how to get it. He cut the girl out from the swelling crowd—they were pouring now in gusty lumps from the exits—as a skilled sheep dog a desired ewe.

‘Where?’ barked Grayling. ‘What is it?’

The girl gasped something, pointing. He dropped her arm. He jumped for the arch upon his right which framed the stairs leading up to the Royal Circle and Balcony. Despite his years and weight, he went up the stairs three steps at a time and came, after thirty of them, to the first floor vestibule where was the Tea Lounge and the chocolate counter and main door to the Royal Circle. That door was closed and before it there stood white-faced but determined, the short and ungainly bulk of Rippon, the theatre’s manager. The tall, broad, heavy-coated figure of Heatherstone was leaning, his hands flat upon the front of the chocolate counter, peering over it. At the sound of Grayling’s footsteps he looked up, twisting over his right shoulder a face whose tight clenched mouth, out-thrust jaw and fierce pallor brought the newcomer to his side quicker than would have any words.

‘Look!’ said Heatherstone.

Grayling stood beside him, and now himself peered over the counter and down.

In the uncarpeted semi-circle of floor between the blank back of the counter and the shelves, gaudy with sweatmeat boxes, there lay, like a crumpled life-size doll, the body of a young woman. Her face was pressed to the floor. Her arms were doubled beneath her. Her legs were ungainly asprawl in a position impossible, it seemed, for a living person …

And upon her back, between slight shoulders and waist, there lay like a square yellow lake, a piece of paper.

And out from the paper, staring up at Grayling’s eyes, printed in black ink, were four words:

WITH THE BUTCHER’S COMPLIMENTS.

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_6317a1a1-2c2a-5fe9-9fe6-214de1177849)