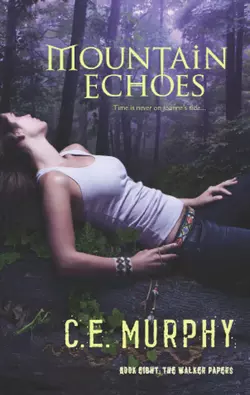

Mountain Echoes

C.E. Murphy

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Зарубежное фэнтези

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Joanne Walker has survived an encounter with the Master at great personal cost, but now her father is missing – stolen from the timeline. She must finally return to North Carolina to find him – and to meet Aidan, the son she left behind long ago.That would be enough for any shaman to face, but Joanne′s beloved Appalachians are being torn apart by an evil reaching forward from the distant past. Anything that gets in its way becomes tainted – or worse.And Aidan has gotten in the way.Only by calling on every aspect of her shamanic powers can Joanne pull the past apart and weave a better future.It will take everything she has – and more. Unless she can turn back time…