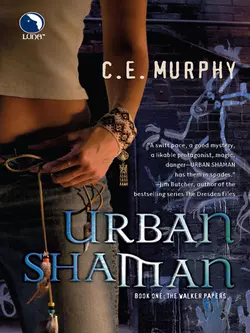

Urban Shaman

Urban Shaman

C.E. Murphy

Joanne Walker has three days to learn to use her shamanic powers and save the world from the unleashed Wild Hunt. No worries. No pressure.Never mind the lack of sleep, the perplexing new talent for healing herself from fatal wounds, or the cryptic, talking coyote who appears in her dreams. And if all that's not bad enough, in the three years Joanne's been a cop, she's never seen a dead body–but she's just come across her second in three days. It's been a bitch of a week. And it isn't over yet.

Praise for

C.E. MURPHY

and her books:

The Walker Papers

Coyote Dreams

“Tightly written and paced, [Coyote Dreams] has a compelling, interesting protagonist, whose struggles and successes will captivate new and old readers alike.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

Thunderbird Falls

“Thoroughly entertaining from start to finish.”

—Award-winning author Charles de Lint

“The breakneck pace keeps things moving…helping make this one of the most involving and entertaining new supernatural mystery series in an increasingly crowded field.”

—LOCUS

“Fans of Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files novels and the works of urban fantasists Charles de Lint and Tanya Huff should enjoy this fantasy/mystery’s cosmic elements. A good choice.”

—Library Journal

Urban Shaman

“C.E. Murphy has written a spellbinding and enthralling urban fantasy in the tradition of Tanya Huff and Mercedes Lackey.”

—The Best Reviews

“Tightly plotted and nicely paced, Murphy’s latest has a world in which ancient and modern magic fuse almost seamlessly…Fans of urban fantasy are sure to enjoy this first book in what looks to be an exciting new series.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

[nominee for Reviewer’s Choice Best Modern Fantasy]

The Negotiator

Hands of Flame

“Fast-paced action and a twisty-turny plot make for a good read…Fans of the series will be sad to leave Margrit’s world behind, at least for the time being.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

House of Cards

“Violent confrontations add action on top of tense intrigue in this involving, even thrilling, middle book in a divertingly different contemporary fantasy romance series.”

—LOCUS

“The second title in Murphy’s Negotiator series is every bit as interesting and fun as the first. Margrit is a fascinatingly complex heroine who doesn’t shy away from making difficult choices.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

Heart of Stone

“[An] exciting series opener…Margrit makes for a deeply compelling heroine as she struggles to sort out the sudden upheaval in her professional and romantic lives.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A fascinating new series…as usual, Murphy delivers interesting worldbuilding and magical systems, believable and sympathetic characters and a compelling story told at a breakneck pace.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

C.E. Murphy

Urban Shaman

Book One: The Walker Papers

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

This book is for my grandfather,

Francis John Joseph McNally Malone,

who would have been proud of me.

Acknowledgments

I hardly know where to begin saying thank you. Starting at the end and working my way backward seems appropriate.

First: my editor, Mary-Theresa Hussey, for taking a chance on a brand-new author; my agent, Jennifer Jackson, for her enthusiasm; and cover artist Hugh Syme, whose work I’m delighted to have my book judged by.

Second: Trip, for pointing out the glaring error in the rough draft and thereby making this a much better book; Silkie, for demanding the next chapter every time she saw me; and Sarah, my critique partner extraordinaire.

Third: my family, who never once doubted they’d be holding one of my books in their hands one day…

And most of all, Ted, who looked out the airplane window in the first place.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER ONE

Tuesday, January 4th, 6:45 a.m.

There’s nothing worse than a red-eye flight.

Well, all right, that’s wildly untrue. There are lots of things worse than red-eye flights. There are starving children in Africa, hate crimes and Austin Powers’s teeth. That’s just off the top of my head.

But I was crammed into an airplane seat that wouldn’t comfortably hold a four-year-old child, and had been for so many hours I was no longer certain what species I belonged to. I hadn’t slept in over a day. I was convinced that if someone didn’t stay awake, the airplane would fall out of the sky, and I couldn’t trust anyone else to do the job.

My stomach was alternating between nausea from the airline meal I’d eaten hours earlier, and hunger from not eating another revolting meal more recently. I’d forgotten to take my contact lens case with me in my carry-on, and my eyes were burning. My spine was so bent out of shape I’d have to visit a chiropractor for a week to stand up straight again. I was flying back from a funeral to be fired.

Overall, starving children in Africa were taking a distant second to my own misery and discomfort. Shallow, but true.

A very small part of my mind was convinced that if the flight attendants would just let me into the unpressurized luggage compartment to find my contact case, everything would miraculously be right with the world. None of them would let me, so my contacts were welded to my eyes. Every several minutes I decided it wasn’t worth it and started to take them out. Every time, I remembered that they were my last pair and I’d have to suffer with glasses until I made an eye appointment.

I might have succumbed, but the glasses in question were also with my luggage. The idea of navigating a soft-focus world full of featureless faces gave me a headache.

Not that I didn’t have one anyway.

I climbed over the round man sleeping peacefully beside me and went to the bathroom. At least I could take the contacts out and stew them in tap water for a few minutes. Anything would be better than keeping them in my eyes.

Anything except my reflection. Have you ever noticed that the mirror is by far the largest object in those tiny airplane restrooms? I was a sick pasty color under the flickering florescent light, my eyes much too green against a network of bloodshot vessels. I looked like a walking advertisement for one of those “wow” eye-drop commercials. Second runner-up for Least Attractive Feature on an International Flight was my hair. I put my contacts in two little paper cups and set them ostentatiously on the appropriate sides of the sink, then rubbed water through my hair to give it some life again.

Now I looked like a bloodshot porcupine. Big improvement. The only thing on my person that didn’t look slimy was the brand-new silver choker necklace my mother’d given me just before she died. A Celtic cross pendant sat in the hollow of my throat. I wasn’t used to jewelry, and now that I’d been reminded it was there, it felt mildly horrible, like someone was gently pushing his thumb against the delicate flesh. I shuddered and put my contacts back in before weaving my way back down the aisles to my seat. The flight attendants avoided me. I couldn’t blame them.

I rested my forehead on a grease spot I’d left on the window earlier. The airlines, I thought, must have custodians who clean the windows, or there’d be an inches-thick layer of goo on them from people like me.

That thought was proof positive that I shouldn’t be allowed to stay up for more than eighteen hours at a time. I have a bad habit of following every thought to its miserable, pathetic little end when I’m tired. I don’t mean to. It’s just that my brain and my tongue get unhinged. Though some of my less charitable acquaintances would say this condition didn’t require sleep deprivation.

The plane had been descending for a while now, and I squinted at my heavy black wristwatch. The bright orange button for changing the time had become permanently depressed in Moscow, or maybe Venice. Probably Moscow; I’d found Moscow depressing, and saw no reason why the watch shouldn’t. It claimed it was 5:50 p.m., which meant it was almost seven in the morning. I frowned out the window, trying to find the horizon. The sky wasn’t turning gray yet, not flying into Seattle three days after New Year’s. I blinked at the darkness, trying to unglue my contacts again.

My eyes teared up and I spent a few minutes with my hands over them, hoping perversely that I didn’t blink the contacts out. By the time I could see again, the captain had announced the final descent into Seattle. Couldn’t they find a less ominous phrase for it? I don’t like flying as it is, even without the implication that before landing I might want to have all my worldly and spiritual affairs in order. I pressed my head against the window so I could see the ground when it came into view. Maybe I could convince it to let us land without it being our real final descent.

Or maybe not. The plane banked abruptly and began to climb again. A moment or two later the captain’s voice crackled over the intercom.

“Sorry about that, folks. Little disagreement over who got to land next. We’re going to take another spin around the Emerald City and then we’ll have you at the gate right on time.”

Why do airline pilots always call passengers “folks”? I don’t usually take umbrage at generic terminology—I’m one of those forward-thinkers who believes that “man” encompasses the whole darned race—but at whatever o’clock in the morning, I thought it would be nice to be called something that suggested unwashed masses a little less. Ladies and gentlemen, for example. Nevermind that, being an almost six-foot-tall mechanic, I had a hard time passing for a lady on a good day, which this wasn’t.

I watched lights slip away beneath us as we circled. If I have to fly, I like flying into cities in the dark of morning. There’s something reassuring and likable about the purposeful skim of vehicles, zooming along to their destinations. The whisk of cars meant that the people driving them had a goal, somewhere to be, something to do. That was a hell of a lot more than I had.

I stared down at the moving lights. Maybe I didn’t like them after all.

The plane dropped the distance that made me an active voyeur in people’s lives, instead of a distant watcher. I could see individuals under the streetlights. Trees became sets of branches instead of blurry masses of brown.

A school went by below us, swingsets empty. The neighborhood was full of tidy, ordered streets. Carefully tended trees, bereft of leaves, lined uniformly trimmed lawns. Well-washed cars reflected the streetlights. Even from the air well before sunrise, it screamed out, This Is A Good Place To Live.

The next neighborhood over didn’t look as posh. Wrong side of the metaphysical tracks. Cars were older, had duller paint and no wax jobs to make them gleam in the streetlights. Mismatched shingles on patched roofs stood out; lawns were overgrown. It wasn’t that the owners didn’t care. It was that the price of a lawnmower or a matched roof patch could be the difference between Christmas or no Christmas that year.

Not that I knew anything about it.

A whole street went by, lightless except for one amber-colored lamp, the kind that’s supposed to cut through fog. It made the street seem unnaturally vivid, details coming into sharp-edged focus below me.

A modern church, an A-frame with a sharp, nasty spire, was lit by the edges of the lone amber light. Its parking lot was abandoned except for one car, parked at an angle across two spaces, one of its doors hanging open. I wondered if it closed at all. Probably: it was a behemoth from the seventies, the kind of car that will last forever. I grew up with that kind of car. Air bags or no, the little crumply things they make today don’t seem as safe.

Someone tall and lean got out of the car, draping himself over the door as he looked down the street toward the functional light. Even from above I could see the glitter of light on the butterfly knife he played with, comfortable and familiar. Watching, I knew that he could play knife games in the dark and blindfolded, and he’d never stab a finger.

A woman broke into the amber light, running down the center of the street. She took incredibly long strides, eating a huge amount of distance with each step, but her head was down and her steps swerved, like she wasn’t used to running. Her hair was very long, and swung loose, flaring out as she whipped her head back to look behind her.

I twisted in my seat as the plane left the subdivision behind, trying to see.

A pack of dogs leaked out of the darkness. Their coats were pale gold under the amber light, and they loped with the casual confidence of a hunting pack following easy prey.

The woman stumbled, the pack gained and the plane took me away from them.

“You don’t understand. There is a woman in trouble out there.” It was the fourth time I’d said it, and the pilot kept looking at me like I was on drugs. Well, maybe I was. Lack of sleep has the same effect as certain narcotics. I was lodged in the door of the cockpit, other passengers pushing out behind me. Fourteen minutes had passed since I saw the woman. There was a knot of discomfort in my stomach, like I’d throw up if I didn’t find a way to help her. I kept hoping I’d burp and it would go away, but I didn’t, and the pilot was still eyeing me.

“And you saw this from the plane,” he said, also for the fourth time. He had that bright lilting sound to his voice that first grade teachers use to mask irritation. “There are lots of people in trouble, ma’am.”

I closed my eyes. They screamed with pain, tears flooding as I opened them again. Through the upwell, I saw an expression of dismayed horror cross the pilot’s face.

Well, if he was going to fall for it, I might as well milk it. “It was five minutes before we landed,” I quavered. “We circled around and came in from the northwest.” I lifted my wrist to show him the compass on my watch band, although I hoped that, being the pilot, he knew we’d approached from the northwest. “I was looking out the window. I saw a woman running down the street. There was a pack of dogs after her and a guy with a switchblade down the street in the direction she was running.”

“Ma’am,” he said, still very patiently. I reached out and took a fistful of his shirt. Actually, at the last moment, I grabbed the air in front of his shirt. I didn’t think security could throw me out of the airport for grabbing air in a threatening fashion, not even in this post-9/11 age.

“Don’t ma’am me…” I stared at his chest until my eyes focused enough to read his name badge. “Steve. Is that your name? Steve. Don’t ma’am me, Captain Steve. I just need to know our rate of descent. Humor me, Captain Steve. I work for the police department. You don’t want me to go to the six o’clock news after a murder’s been discovered and tell them all about how the airline wouldn’t lift a finger to help the woman who died.”

I didn’t know why I bothered. The woman was probably dead by now. Still, Captain Steve blanched and looked back over his shoulder at his instruments. I retrieved my hand and smiled at him. He blanched again. I guess my smile wasn’t any better than my hair or eyes just now.

“Hurry,” I said. “Once the sun comes up the streetlights will go off and I don’t know if I’ll be able to find her then.”

I left my luggage in the airport and climbed into a cab, trying to work out the triangulation of height, speed and distance. “Drive,” I said, without looking up.

“Where to, lady?”

“I don’t know. Northwest.”

“The airline? It’s just a couple feet down the term—”

“To the northwest,” I snarled. The cabby gave me an unfriendly look and drove. “Do you have a map?” I demanded a minute later.

“What for?”

“So I can figure out where we’re going.”

He turned around and stared at me.

“Watch the road!” I braced myself for impact. Somehow—without looking—he twitched the steering wheel and avoided the collision. I collapsed back into the seat, wide-eyed. “Map?” I asked, somewhat more politely.

“Yeah, here.” He threw a city guide into my lap. I thumbed it open to find the airport.

Airplanes go fast. I realize this isn’t a revelation to stun the world, but it was a little distressing to realize how far we’d flown in five minutes, and how long it would take to drive that. “All right, we’re going northwest of the lake.” I remembered seeing its off-colored shadow making a black mark below the plane as we’d left the subdivision behind. “Somewhere in Aurora.”

“Think? That ain’t such a good neighborhood, lady. You sure you wanna go there?”

“Yeah, yeah, I know. I’m trying to find somebody who’s in trouble.”

The cabby eyed me in the rearview. “That’s the right place to look.”

I glared at him through my eyebrows. He smiled, a thin I’ve-seen-it-all grin that didn’t really have any humor in it. He had gray eyes under equally gray, bushy eyebrows. He had a thick neck and looked like he’d be at home chewing on a stogie. I asked if he had a cigarette. He turned around and looked at me again.

“Those things’ll kill you, lady.”

His voice was rough and deep like a lifetime smoker’s. Surprise showed on my face and he gave me another soulless smile, reflected in the mirror. “My wife died of emphysema three years ago on our forty-eighth wedding anniversary. You want a smoke, kid, find it somewhere else.”

Sometimes I wonder if I have a big old neon sign stamped on my forehead, flashing Asshole. I retaliated with stunning wit: “I’m not a kid.”

Gray eyes darted to the mirror again, and back to the road. “You’re what, twenty-six?”

Nobody ever guessed my age right. Since I was eleven, people have misguessed my age anywhere from three to seven years in one direction or the other. I felt my jaw drop.

“It’s a gift,” the cabby said. “A totally useless gift. I can tell how old people are.”

I blinked at him.

“Great way to get good tips,” he went on. “I go into this long explanation of how I always get ages right, and then I lie. Works like a charm.”

“So why’d you guess my age right?” The question came out of my mouth without consulting my brain first. I didn’t want to have a conversation with the cabby.

“Never met anybody who didn’t want to be in their twenties, so what’s the point? Why you going out there, lady? Lotta trouble out that way, and you don’t look like the type.”

I glanced sideways at the window. A faint reflection looked back at me. He was right. I looked tired, hopeless and worn-out, but not like trouble. “Looks can be deceiving.” His eyes slid off the rearview mirror like he was too polite to disbelieve aloud. “It’s somebody else who’s in trouble,” I said. “I saw her from the plane.”

He twisted around yet again. “You’re trying to rescue somebody you saw from an airplane?”

“Yeah.” I flinched as he twitched the steering wheel to keep in our lane, again without looking. “What do you do, use the Force?”

He glanced at the road and shrugged before turning around again. “So, what, you’ve got a hero complex? How the hell are you gonna find one dame you saw from the air?”

“I passed a couple basic math classes in college,” I muttered. “Look, I got the approximate height and speed we were traveling from the pilot, so figuring out the distance wasn’t that hard. I mean, adjusting for the change in speed is kind of a pain in the ass, but—” I set my teeth together to keep myself from rattling on. It was a moment before I was sure I had enough control over my brain to continue without babbling. “Someplace in that vicinity there’s a modern church on a street with only one amber streetlight. If I can find it before the lights go out—”

“Then you’ll be the first one on a murder scene. You’re nuts, lady. You must be desperate for thrills.”

“Like it could possibly be any of your business,” I snapped.

“Touchy, too. Pretty girl like you oughta be on her way home to her sweetie, not chasin—”

“I don’t have one.” I admit it. I snarled again.

“With your personality, I can’t figure why not, lady.”

I leaned forward and rubbed my eyes with my fingertips, elbows on my knees. The knot of unpleasantness in my stomach felt like it was trying to push its way out through my sternum, pressuring me to act whether I liked it or not. The idea that it would go away if I could just find the woman was settled into my bones, logic be damned. “Haven’t you ever just really felt like you had to do something?”

“Sure. I felt like I really had to marry my old lady when she got knocked up.”

I was in a cab with Plato. His depth overwhelmed me. I lifted my head enough to stare over the back of the seat at his shoulder. He grinned. He had good teeth, clean and white and strong, like he hadn’t ever smoked. They were probably false.

“Never felt like I had to go chasing down some dame I saw from an airplane, nope. Guess I figured I had enough troubles of my own without adding on somebody else’s.”

I leaned against the window, eyes closed. “Maybe I’ve got enough that I need somebody else’s to make the load seem lighter.”

I could feel his gaze on me in the rearview mirror again. Then he grunted, a sort of satisfied noise. “All right, lady. Let’s go find your corpse.”

CHAPTER TWO

“Thanks for the vote of confidence.” I glowered out the window. I wouldn’t have been so annoyed if I’d felt more confident myself. The cabby—whose name was Gary, according to the posted driver’s license, and whose seventy-third birthday had been three days ago—drove like the proverbial bat out of hell, while I clung to the seat and tried not to gasp too audibly.

The streetlights were still on when we got to Aurora, and I wasn’t actually dead, so I felt like I shouldn’t complain. Gary pulled into a gas station. I squinted tiredly at the back of his head. “What are you doing?”

“Go ask if anybody knows where that church of yours is.”

My squint turned into lifted eyebrows. “I thought men couldn’t ask for directions.”

“I ain’t askin’,” Gary said with aplomb. “You are. Go on.”

I got.

The pimply kid behind the counter didn’t look happy to see me. Judging from his thrust-out lip and down-drawn eyebrows, I figured he wasn’t happy to see anybody, and didn’t take it personally. He smirked at me when I asked about the church. Smirking is not a nice expression. The only person in the history of mankind who’d been able to make smirking look good was James Dean, and this kid, forgive me Senator Bentsen, was no James Dean.

I tried, briefly, to remember if I’d been that sullen and stupid when I was sixteen. I figured the fact that I couldn’t remember didn’t bode well, and went straight for the thing I knew would have gotten my attention at that age: cash. I wasn’t usually prone to bribing people, but I was too tired to think of anything else and I was in a hurry. I dug my wallet out and waved a bill at the kid. His eyes widened. I looked at it. It was a fifty.

Shit.

“You better walk me to the church for this, kid.”

He didn’t take his eyes from the bill. “There’s two A-frames I can think of. One’s about five blocks from here. The other is a couple miles away.”

“Which direction? For both of them.” He told me, still watching the fifty like it was a talisman. I sighed, dropped it on the counter, and muttered, “Thanks,” as I pushed my way out of the gas station. He snatched it up, hardly believing I was really handing it over. Great. I’d just turned a kid onto the lifetime role of snitch.

Worse, I’d given away a quarter of the meager cash I had on hand, and cabs from SeaTac were damned expensive. I climbed back into the car. “East a few blocks, and if that’s not it, there’s another one to the southwest. Hurry, it’s getting light out.”

“What, you want to get your fingers in the blood while it’s still warm? You need help, lady.”

“Joanne.” Having a nosy cabby know my name had to be better than being called “lady” for another half hour. “And you’re the one hung up on corpses. I’m hoping she’s still alive.” I tugged on my seat belt, scowling again. It was starting to feel like a permanent fixture on my face.

“You always an optimist, or just dumb?”

A shock of real hurt, palpable and cold, tightened itself around my throat and heart. I fumbled the seat belt. It took effort to force the words out: “You have no right to call me dumb.” I stared out the window, seat belt in one numb hand, trying furiously to blink tears away. Gary looked at me in the rearview, then twisted around.

“Hey, hey, hey. Look, lady. Joanne. I didn’t mean nothin’ by it.”

“Sure.” My voice was harsh and tight, almost too quiet to be heard. “Just drive.” I got the seat belt on this time. Gary turned around and drove, quiet for the first time since I’d gotten in the cab.

I watched streetlights go by in the hazy gold of sunrise, trying to get myself under control. I didn’t generally cry easily and I didn’t generally get hurt by casual comments from strangers. But it had been a long day. More than a long day. A long week, a long month, a long year, nevermind that it was only the fourth of January. And the day was only going to get longer. I still had to stop by my job and get fired.

The streetlights abruptly winked out as we turned down another street, and with them, my chance to find the runner. A small voice said, “Fuck.” After a moment I realized it was me.

“That one’s still on,” Gary said, subdued. I looked up, keeping my jaw tight to deny tired, disappointed tears. A bastion of amber stood against the dawn, one single light shining on the entire street. I watched it go by without comprehension, then jerked around so fast I hurt my neck. “That’s it!”

Gary hit the brakes hard enough to make my neck crunch again. I winced, clutching at it as I pressed my nose against the window. “That’s it, that’s it!” I shrieked. “Look, there’s the church! Stop! Stop!” The car was gone from the parking lot, but there was no mistaking the vicious spire stabbing the morning air. “Holy shit, we found it!”

Gary accelerated again, grinning, and pulled into the church parking lot. “Maybe you’re not dumb. Maybe you’re lucky.”

“Yeah, well, God watches over fools and little children, right?” I tumbled out of the cab, getting my feet tangled in the floor mat and catching myself on the door just before I fell. “Well?” I demanded. “Aren’t you coming?”

His eyebrows elevated before he shrugged and swung his own door open. “Sure, what the hell. I never saw a fresh murdered body before.”

I closed my door. “Have you seen stale ones?” I decided I didn’t want to know the answer, and strode away. Gary kept up, which surprised me. He was so broad-shouldered I expected him to be short, but he stood a good two inches taller than me. In fact, he looked like a linebacker.

“You look like a linebacker.”

“College ball,” he said, disparaging enough that it was obvious he was pleased. “Before it turned into a media fest. It’s all about money and glory now.”

“It didn’t used to be?”

He flashed me his white-toothed grin. “It used to be about glory and girls.”

I laughed, stopping at the church door, fingertips dragging over the handle. They were big and brass and twice as wide as my own hands. You could pull them down together and throw the doors open in a very impressive fashion. I wasn’t sure I wanted to.

“You sure your broad is gonna be in here, lady?”

“Yeah,” I said, then wondered why that was. It made me hesitate and turn back to the parking lot. Except for Gary’s cab, it was empty. There was no reason the woman couldn’t have gotten into the car with the man with the butterfly knife, no real reason to think she’d even made it as far as the parking lot, much less the church.

“Yeah,” I said again, but trotted back down the steps. Gary stayed by the door, watching me. The car’d been on the south end of the parking lot, between the woman and the church. I jogged over there, eyes on the ground. I heard Gary come down the steps, rattling scattered gravel as he followed me.

“What’re you looking for? I thought you said the broad was in the church.”

I shrugged, slowing to a walk and frowning at the cement. “Yeah, but that’s probably just wishful thinking. I was wondering if there’d been a fight. If the guy with the knife was after her, she’d have had to have gotten thr—”

“What guy with a knife?” Gary’s voice rose as I crouched to squint at the ground. I looked over my shoulder at him.

“Didn’t I mention that?”

“No,” he said emphatically, “you didn’t.”

“Oh. There was a guy with a knife. He was good, too.”

“You saw this from a plane?”

I puffed out my cheeks. “You ever seen somebody who’s good with a knife? Street-good, I mean?”

“Yeah.”

“Okay. So have I. It looks a certain way. Graceful. This guy looked that way, yeah, even from a plane.”

“Lady, you better have like twenty-two-hundred vision.”

I stood up. The bubble of icky feeling in my stomach was still there, prodding at me like I hadn’t done enough to help the woman. “I wear contacts.”

Gary snorted derisively. I sighed. “I know what I saw.”

“Sure.” He didn’t say anything for another second, looking at the ground. “I know what you didn’t see.”

“What?”

He pointed, then walked forward a couple of spaces. “Somebody lost a tooth.” He bent over and poked at a shining white thing on the concrete, not quite touching it.

I walked over, bending to look at the enameled thing on the ground. It was a tooth, all right, smooth little curves and a bumpy top, complete with bloody roots. “Eww. Somebody got cut, too.” I nodded at thin splatters of blood, a few feet farther out than the tooth, that were already dry on the concrete. Gary cast his gaze to the heavens.

“The lady goes ‘eww’ at a tooth and she’s looking for a corpse.”

“I’m looking for a person,” I corrected.

“And you think she’s in the church.”

“Yeah.”

“So why the hell are we screwing around in the parking lot?”

I looked around. “The light’s better over here?” It was one of my favorite jokes, left over from my childhood. I never expected anyone else to get it, but Gary grinned, dug a hand into his pocket, and tossed me a quarter. I caught it, grinning back. “Now that we’ve got that taken care of.”

We walked back to the church together.

I was right. The doors swept open, impressively silent. I felt like I should be leading a congregation in search of the light, not a linebacker-turned-cabby in search of a corpse. I stepped through the doors, half-expecting a floorboard to creak and mar the enormous silence.

Within a few steps I was sure a floorboard wouldn’t have dared creak in this place. It wasn’t the solemn, weighty quiet of old churches or cathedrals. Those places could absorb the sound of heels clicking and children laughing with dignity and acceptance. This church simply forbade them. I wasn’t even wearing heels, and I found myself leaning forward on my toes a little so that my tennies couldn’t possibly make any excessive noise on the hardwood floors. This was a church where “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” would be performed and harkened to weekly. I noticed I was holding my breath.

It was stunning, in an austere, heartless way. The A-frame probably carried sound beautifully, but the only natural lighting was from a wall of windows behind the pulpit. I use the term natural loosely: there wasn’t much natural about the violent, grim images of Christ’s crucifixion, or Joseph and Mary being turned away from the inn, or Judas’s betrayal, or any of the other scenes I recognized, more of them jimmied into the stained glass than I would have thought possible. This was a church where you came to be terrified into obedience, not welcomed as a sinner who has found the true way.

The pews were hardwood, without cushions, and the choir books looked as though they’d never been cracked open. I guessed you’d better know your music before you came to church. It was not a friendly place.

It was also completely empty of human life other than my own and Gary’s. I looked back at him. He frowned faintly before meeting my eye. I couldn’t blame him.

“I don’t know where she is,” I said before he could ask, and lifted my voice. “Hello? Hello?” My voice bounced up to the rafters and echoed back at me. The acoustics were incredible, and I tilted my head back to look longingly at the ceiling. “Wow. I’d love to sing in here.”

“Yeah? You sing?”

I shrugged. “I don’t scare the neighbors.”

Gary bent over and looked under the pews. “Yeah, well, maybe you can sing yourself up a dame. There ain’t nobody here, Jo.”

A muscle in my shoulder blade twitched. “Y’know, nobody calls me that except my dad.”

“What, did he want a boy?”

“Not exactly.” That seemed like enough information to volunteer.

Gary unbent a little, hooking his arm over the top of a pew as he looked at me. Enough time passed to let me know that he was politely not asking about my dad before he asked, “Then what do they call you?”

“Joanie, or Joanne, usually. Sometimes Anne, Annie.”

Gary straightened up, hands in the small of his back. “My wife was named Anne. You don’t look like an Anne to me.”

I smiled. “What’d she look like?”

“’Bout four eleven, blond hair, brown eyes, petite. You gotta be at least a foot taller than she was.”

“Yeah.” It came out sounding like a laugh, and I smiled again. “So call me Jo, then.”

“You sure? I don’t think you get along with your old man.”

“I don’t not get along with him.” How had I ended up in a church looking for a body and discussing my home life? “It’s okay. I don’t mind Jo.” I waited for the muscle in my shoulder blade to spasm again. It always did when I was tense. This time it didn’t. Maybe I really didn’t mind being called Jo. Who knew?

“There’s nobody in here, Jo,” Gary repeated. I tried to stuff my hands in my pockets, only to discover I didn’t have any. The thing I’d learned about traveling was that it was slightly less miserable if I wore stretch pants with an elastic waistband. The ones I was wearing were black and comfy and had nice straight legs, but no pockets. I hooked my thumbs into the strap of my fanny pack, instead. I hated the things, but I never learned to carry a purse, and a fanny pack is at least attached to me. Makes it harder to forget.

“C’mon, let’s go. Nobody here.”

“No, wait.”

Gary sighed, exasperated, and leaned against a pew, arms folded across his chest. Seventy-three or not, he made a pretty impressive wall of a man. “Then do your thing and find the broad.”

I looked at him. “My thing?”

“You got some kinda thing going on here, lady. Normal people don’t stick their heads out a plane window and see dames that need rescuing. So do your thing and rescue her. My meter’s still running.”

Oh, God. It probably was, too. “Hope you take credit cards.” I walked to the front of the church and around the pulpit.

I really, honest-to-God, expected to see the woman cowering in the back side of the pulpit. That she wasn’t came as a shock. “Well, shit.”

“What? You find your body after all?” Gary shoved off his pew and came long-legging it up to the front.

“No, you ghoul. There’s nobody here. I really thought she would be.”

“I’ll cut you a break and won’t expect a tip, just for the satisfaction of being right.” He leaned on the pulpit, grinning whitely at me. I had the sudden urge to pop him in those nice straight clean teeth. It must have shown in my face, because his grin got even wider. “You wanna try it?”

“No,” I said sourly. “I think you’d break me in half.”

“Only a little bit.”

“Gee. Thanks.” I backed up a couple steps and leaned on the edge of the…hell if I know what it’s called. Looked like an altar to me. All gilded and dour. It had probably never been introduced to a woman’s behind in its whole existence. Or maybe it had been. You always heard stories about the priest who’s a pillar of the community but turns out to be having affairs with half the congregation. Seemed to me if you’re going to sin, you might as well do it right. On the altar would be a nice big sin. “I thought she’d be here.”

“Why?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. Churches are supposed to be sanctuary, or something. I thought she’d be safe in here. Consecrated ground.”

“What century are you living in, lady?”

“The wrong one, I guess.” I thumped on the edge of the altar, annoyed.

The top slipped.

I leaped off it like it had bitten me. Gary’s bushy eyebrows went up. We both stared at the inch-wide crack at the edge of the box where the lid had pushed back. “You don’t believe in vampires, do you, Gary?”

“God damn it,” he said, “I was trying real hard not to think that way.”

“Kind of fits, though, doesn’t it? Scary-looking church, big old crypt in the middle, the living dead ris—”

“It’s past dawn,” Gary said hastily. “No vampires after dawn. Right?”

“There’s no such thing as vampires, Gary.”

He stared at me dubiously. I stared at the crypt dubiously. Funny how a second ago it had been an altar and now it was a crypt. “Well?” he demanded. “Are you gonna look in it?”

“Yeah.”

“When?”

“As soon as I get up the nerve.”

He prodded me in the small of my back, pushing me forward. I admired the resistance in my body. I felt like he was trying to move a me-shaped lead weight. I expected to hear my feet scraping along with the sound of metal ripping up hardwood. Instead, I stumbled half a step forward, then glared over my shoulder at Gary. “You’re a big strong man. Aren’t you supposed to be plunging into danger before me?”

“You’re forty-seven years younger than me, lady,” he pointed out. “And almost as tall as I am. And you’re in my weight class. And it’s your vampire in the coffin.”

“I am not in your weight class,” I said, offended. “You’ve got to outweigh me by at least forty pounds.” I edged a quarter of a step closer to the crypt. “And it’s not a vampire.”

“How much do you weigh?”

“Isn’t it rude to ask a woman how much she weighs?”

“Nah, it’s rude to ask how old she is, and I already know.”

Oh. Damn. I stepped forward, holding my breath. The crypt didn’t do anything. “I weigh one seventy-two.”

“No shit?”

“I’m almost six feet tall, Gary, what do you want me to weigh, a hundred and thirty? I’d be dead.” I peeked into the little hole the lid made where it had slid over. If there was a vampire in there, it was a very small, very hidden vampire. Or maybe it blended with shadows well. Vampires were supposed to do that, weren’t they?

I was scaring myself. “Give me a hand with this.”

Gary crept forward. “I outweigh you by sixty pounds.”

“That’s why you’re a linebacker, and I’m not. Push on three. One, two, three!”

I underestimated how much push we could provide. The lid shot off the box, crashing to the floor with a thud that rattled the rafters. I fell forward, shrieking, with visions of being sucked dry by vampires supplied by my too-vivid imagination.

Halfway into the crypt, I was met by another shrieking woman on her way out.

CHAPTER THREE

My head hit the floor with a crack only slightly less impressive than the crypt lid had made. My vision swam to black, and my tailbone decompressed like a series of firecrackers. I wouldn’t need to visit the chiropractor after all.

Vision returned in time to see something bright and glittery arching down at me. I flung my hand up, barely deflecting the fall of a knife. My wrist hit the woman’s with the solid thunk that meant a week from now, after I’d forgotten this had happened, a bone bruise would color half my arm. The woman’s grip loosened and the knife glanced off my cheekbone instead of driving into my throat. I hit her again, and the knife skittered away, bouncing across the hardwood floor.

The woman shrieked again—or maybe she hadn’t stopped—and scrambled after the knife. I tackled her, flinging my arms around her. Her white blouse suddenly stained red where my cheek pressed against it.

Gary pulled her out from under me and to her feet, pushing her elbows in against her waist and holding her still. His hands looked bizarrely large in proportion to her waist. She winced and hissed, her head down as I got up unsteadily and touched my face. Blood skimmed over my fingertips and into my palm, coloring in the lifeline. I watched vacantly as it trailed all the way around the side of my hand and down my wrist. My face didn’t hurt. It seemed like it should.

“You got lucky,” Gary said. “She was gonna cut your throat right out. What should I do with her?”

I looked up, startled and vacant. “Oh, fer Chrissakes,” he said, “You’re shocky, or somethin’. Get something to stop the bleeding.”

That seemed like a pretty good idea. I looked around, silver catching my eye again. The knife she’d cut me with lay against the foot of a pew, a nice heavy butterfly knife. I picked it up and cut a piece off the altar banner, holding it to my face while Gary asked again what to do with the woman.

“Um,” I said, and then my face started to hurt. For a minute I was too busy blinking back tears to give a damn what Gary did. I croaked, “Hold her for a minute,” and tried increasing the pressure on my cut to see if it helped the pain any. It didn’t. I looked up through teary eyes. It had to be the same woman. She had hip-length dark brown hair with just enough curl to make me covet it. “You’re the one I saw from the airplane.”

She lifted her head to look at me, eyes wide. I dropped my hand from my face and the makeshift bandage fell to the floor as I gawked at her.

She was beautiful. Not your garden-variety pretty girl, not your movie-star kind of beautiful. She was the sort of beautiful that Troy had gone to war over. High, fragile cheekbones, delicate pointed chin, absolutely unblemished pale skin. Long-lashed blue eyes, thin straight eyebrows. A rosebud mouth, for God’s sake. There were very fine lines of pain around the corners of her mouth and eyes, and the nostrils of her perfectly straight nose were flared a little, none of which detracted from her beauty.

“Jesus.” I suddenly had a very good idea of why she’d been chased.

“What?” Gary demanded. I just kept ogling the woman. She had a perfect throat. She had great collarbones. She had Mae West curves, too, a real hourglass figure. She was at least eight inches shorter and fifty pounds lighter than I was. It said something for her momentum that she’d knocked me flat on my ass. I didn’t think I could have knocked Gary over, if I’d been her and he’d been me.

I hated her.

I was so busy staring and hating her it took a while to notice there was drying blood on her shirt, not just the new stuff I’d put there, but sticky, half-dried brown spots. “Shit. Let her go, Gary.”

“What?”

“Let her go. Her arms are all cut up. You’re hurting her.”

Gary let go like his hands were on fire. The woman made a small sound and folded her arms under her breasts, shallow gashes leaking blood onto her shirt again. I expected her voice to be musical, dulcet tones, with an exotic accent. Instead she was an alto who sounded like she was from Nowhere In Particular, U.S.A. “You saw me from an airplane?”

People kept saying that. I took a breath to respond and realized I didn’t feel like I needed to throw up anymore. The twist of sickness in my belly had disipated. My shoulders dropped and I let the breath go in a sigh. I wasn’t a fan of my innards guiding my actions. Now all I had to do was explain myself so I could go get fired and go home to sleep. “At about seven this morning. I was flying in from Dublin.” As if that had anything to do with anything. “I saw you running, and something was after you. Dogs, or something. And a guy with a knife.” I looked at the knife I was still holding. “This knife? How’d you get past him? How’d you get away from the dogs?”

“I ran away from the dogs,” the woman said, “and I kicked the guy with the knife in the head.”

Gary and I both stared at her. She smiled a little bit. A little bit of a smile from her was like spending a little bit of time with Marilyn Monroe. It went a long way. “I guess I don’t look like a kickboxer,” she said.

“That’s for damned sure,” Gary mumbled. He looked even more awed than I felt. I guessed it was nice to know some things didn’t change even when you hit your eighth decade. “So how’d you get all cut up?” he asked.

She shrugged a little. “I had to get close enough to kick him.”

“That his tooth out there?”

Her whole face lit up. “I knocked a tooth loose?” She looked like a little kid who’d just gotten her very own Red Ryder BB gun for Christmas. I almost laughed.

“You knew him? Why was he chasing you?” Even as I asked, I knew the question was idiotic. Men have hunted people down for much less attractive prizes. I liked being tall. Next to this woman I felt as ungainly as a giraffe.

“Why did you come to save me if you don’t know who he is?” she asked at almost the same time. We stared at each other.

“Let’s start again,” I said after a long moment of silence. Then I had no idea where to start with someone who’d been attacked and who just tried to cut my throat out. Names seemed like a good place. “I’m Joanne Walkingstick.”

It’s physically impossible to look at your own mouth in astonishment. I gave it a good shot. I hadn’t called myself by that name in at least five years. More like ten. Gary raised his bushy eyebrows at me curiously.

“You don’t look like an Indian,” he said, which really meant, “How the hell did you end up with a last name like Walkingstick?” I’d heard it for the first twelve years of my life.

“I know.” I hadn’t known that a practiced tone of controlled patience could lie in wait for the next time it was needed, but there it was. It hadn’t been needed for years. It meant I wasn’t going to say anything else, and if you wanted to make a big deal of it, you’d end up in a fistfight.

I was good at brawling.

Gary, the linebacker, let the tone blow right over him and stayed there with his arms folded and eyebrows lifted. The woman studied me through drawn-down eyebrows. It made a wrinkle in the middle of her forehead. On me, that wrinkle was scary. On her, it was cute. I hated her some more.

Gary was wrong, anyway. I did look Indian. My coloring was wrong, but in black-and-white photos I looked like I didn’t have a drop of Irish blood in me. I’d changed my last name to Walker when I turned eighteen and graduated from high school. Nowhere official. I just filled out every piece of paperwork, even the diploma application, with Walker. My birth certificate was the only piece of paper I owned that had Walkingstick as my official last name.

“My name is Marie D’Ambra,” the woman said.

“You don’t look Italia—” I nearly bit my tongue off.

“Adopted,” she replied, amusement sparkling in her eyes.

Oh. “My mother was black Irish,” I said after a moment. “I got her coloring.” It seemed like a fair exchange of information. “Why was that guy after you? What was chasing you? It didn’t look like a dog pack. Exactly.”

Marie inclined her head. It looked gracious. How did she do that? “It wasn’t. His name is Cernunnos, and he is the leader of the Wild Hunt. It was the Hunt who chased me. Why did you come to help me?”

I looked sideways at Gary, who shrugged almost imperceptibly. I wouldn’t think a guy with shoulders that wide could shrug imperceptibly. It should be more like plate tectonics. I hoped I was in that kind of shape when I was seventy-something. Marie waited patiently, and I shrugged more perceptibly. I really didn’t want to say, “I felt like I was going to puke if I didn’t,” but I heard myself saying it anyway. I curled a lip, shook my head, and added, “You looked like you needed help. I felt like I had to try to find you.”

One half of her mouth curved up in a smile. I stopped hating her. I couldn’t hate a smile like that. Her smile made the world seem like it would all be okay. “A gwyld at the crossroads,” she murmured, and I frowned at her.

“A what?”

She shook her head and did the wonderful half smile again. “Nothing. I’m sorry for cutting you. I thought you had to be one of Cernunnos’s people. I couldn’t imagine why anyone else would be looking for me.”

“One of his people? Not him himself?” That sounded wrong. “He himself.”

Marie shook her head. “Christian earth. Even Cernunnos can only stand on it a few minutes. None of the Hunt can at all.”

I looked at Gary. Gary looked at me. We both looked at Marie. She smiled the tight little smile of someone who knows she sounds crazy. It made me feel better. “This isn’t the best place to talk about this,” she said.

“Why not? You just said the guy who was after you can’t come here,” Gary said.

“No, but he can send people who can,” I said before Marie could. She nodded. “If he couldn’t, she wouldn’t have thought we might be trouble.” I touched my cheek gingerly. It was still bleeding. “An emergency room might be a good place to go. This is going to need stitches, and you should get looked at, too.”

Marie extended her arms, palms up. Half a dozen cuts still oozed red as she looked at them. She looked like a clumsy suicide attempt. “They’ll heal,” she said dismissively. “He knows I was hurt. I’d rather not go somewhere so obvious.”

“You’d rather bleed?” I demanded. Gary cleared his throat.

“I got a first-aid kit in the car.”

I glared at him. He smiled and shrugged. “Sure,” I said, “the pretty one whose face isn’t cut up gets her way. Fine.” I stomped off the dais, picking the butterfly knife up off the pulpit. It made a satisfying series of clicks as the blade and handles slapped against each other when I closed it.

“Hey. That’s mine.” Marie had to take two steps to every one of mine, even after she ran to catch up with me.

“Not anymore, it isn’t. Call it a finder’s fee.”

“You didn’t find it.”

“I found you.” I shoved the knife into my waistband. Two steps later the elastic shifted and the knife slid down my leg and out of my pants, clattering to the floor. Gary choked back a guffaw and Marie grinned broadly.

I picked up the knife with as much dignity as I could muster and stalked out of the church.

I thought going into a diner all bloody and bandaged was more conspicuous than going to an emergency room, but Marie insisted. Gary butterfly-bandaged my cheek and wrapped up Marie’s arms while I sulked. As a gesture of peace he turned the meter off, but my face hurt too much for me to be grateful.

I dragged a coat out of my carry-on and pulled it on over my bloody T-shirt as we went into the diner. Marie walked in like she was daring the world to comment on her bloodstains. No one did. We sat down, silent until the waitress brought us our drinks. I didn’t know what it was about food, but it always seemed to make it easier to talk.

Marie folded her hands around an enormous glass of orange juice. I had a coffee. Actually, this being Seattle, I didn’t have just a coffee, even at a cheap diner. I had a grande double-shot latte with a shot of amaretto. Just the smell of the stuff got me high.

“Cernunnos leads the Wild Hunt,” Marie said to her orange juice. “They ride to collect the souls of the dead.” She looked up to see if that cleared things up for us. Gary just waited. He really was having a regular black coffee. I didn’t even know they made that anymore. He’d ordered breakfast, too. I was hungry, but between adrenaline and no sleep, I was pretty sure food would just come back up again. Now that I thought about it, the injection of caffeine probably wasn’t such a great idea on that combination. Food would have been better.

“You ain’t dead,” Gary pointed out. Marie winced, producing a pained smile.

“An oversight.”

“Fill in us dumb ones,” I said. “What’s a wild hunt?”

“The Wild Hunt,” she corrected.

“Okay, the wild hunt. What is it?”

She sat back, her hands still wrapped around the orange juice glass. She hadn’t drunk any yet. “Cernunnos was an old Celtic god,” she said slowly. “When Christianity came to Ireland and Britain, his cult was so powerful that it took a while for it to die out. And it never entirely faded.”

“Like any pagan religion,” I interrupted. Marie lifted her eyes to look at me. The muscle in my shoulder blade twitched again and I shrugged, trying to loosen it. “The Peop—the Cherokee still practice their old ways, too. Faith is hard to stomp out.” The People. Walkingstick. What was wrong with me?

“Like any pagan religion,” she agreed. “Cernunnos is the Celtic Horned God, essentially a fertility figure but with very deep ties to death as well. There are Norse and German counterparts, Woden, Anwyn, rooted in a common ancestry.” She waved her hand absently, brushing aside the trivia.

“And he’s after you.” I infused my voice with as much sarcasm as I could. It was pathetically little. She was too pretty to be sarcastic at, even if she was crazy.

“Yes.” Marie nodded and dragged her orange juice to the edge of the table.

“You seriously think you got some kind of god after you?” Gary asked. Marie nodded. Gary turned to me. “I vote we drop her off at a loony bin and run for the hills.”

“Are you asking me to run away with you, Gary? After such a short, violent courtship?” It wasn’t that I didn’t agree. In fact, I pushed my latte away, getting ready to stand up. Gary did the same, looking relieved.

“Sorry, lady,” he said, and stood. I put my palms on the table and looked at Marie. She looked bone-tired, more tired than I felt. She looked like she’d been through this a dozen times already, and was just waiting for the time that she screwed up and didn’t live through it.

Dammit, I’d jumped off a plane and come tearing through the streets of Seattle to find this woman. I didn’t feel like I’d seen it through to the end yet. I settled back into my seat.

“Aw, hell,” Gary said, and sat back down. Marie bit her lower lip, holding her breath while she watched me. When I didn’t move again, she let her breath out and began talking again, without taking her eyes off me. If she thought she was pinning me in place, she was right. Girls weren’t really my thing. Hell, I didn’t even like women much, as a species. I had no idea why I wanted to help her so much. Marie took a deep breath.

“I gather neither of you are mystics.”

Gary laughed so loudly I nearly spilled my coffee. A tired-looking blonde behind the counter turned around and looked at us. Marie twisted a little smile at her orange juice. I suddenly felt sorry for her, which was new.

“Okay,” she said in a very small voice. “Can you handle the idea that there’s more to the world than we see?”

“There are more things, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” It was the obvious line. What wasn’t so obvious was that Gary beat me to it, and said it in a rich, sonorous voice. Marie and I both looked at him. “Annie liked ’em big, not stupid,” Gary said with a grin. “Sure, lady, there’s more than we see.”

Marie glanced at me. “Why does he keep calling me lady?”

“I think it’s an endearing character trait. When he really gets to know you, he’ll start calling you ‘dame’ and ‘broad,’ too.”

“Yeah?” She looked at Gary, then back at me. “How long’ve you known him?” I turned my wrist over to look at my watch, which was still wrong.

“About ninety minutes. So what’re we missing in our philosophies, Marie?”

She smiled. It was radiant. Honest to God. Her whole face lit up, all warm and welcoming and charming. Gary looked pole-axed. I pretended I didn’t and allowed myself the superior thought: Men.

“I’m an anthropologist,” Marie said. “I’ve been studying similarities between cultural mythologies for about ten years now.”

All of a sudden she had an aura of credibility. Well, except I thought she looked about twenty-five. I stole a glance at Gary, who didn’t look disbelieving. Either he thought she looked older than that, or his so-called useless talent was a load of bunk. “How old is she?” I asked him. He lifted a bushy eyebrow, glancing at me, then looked back at her.

“Thirty-nine,” he said, in tandem with Marie. Her eyebrows went up while my jaw went down. Gary looked smug. After a few seconds she shook her head and went on.

“It’s hard,” she said carefully, “to immerse yourself in a study, in mythology and belief, without beginning to understand that even if you don’t believe it, that someone did, and that it has, or had, power. I don’t consider myself particularly susceptible to bullshit.”

Looking at her, I could believe it. She had to have heard every line in the book, by now. It would take genuine effort to remain gullible, and she didn’t seem gullible. She finally lifted her orange juice and drank half of it.

“Certain legends had more power for me than others. They were easier to believe. They tended down Celtic lines—my mom says it’s blood showing through. But the Morrigan, the Hunt, banshees, cross-comparisons of those legends to other cultures were more fascinating to me than most other things. A while ago a gloomy friend of mine pointed out that they weren’t just Celtic legends. They were all Celtic legends that had to do with death or violence.”

She took a deep breath, looking up at us with those very blue eyes. “Right after that I started to be able to sense who was about to die.”

Silence held, stretched, and broke as my voice shot up two octaves. “You’re a fucking banshee?” The tired blonde behind the counter looked our way again, then shifted her shoulders and turned away, uninterested. Marie’s thin straight eyebrows lifted a little.

“I thought you didn’t know anything about those legends?”

“I just got off the plane from a funeral in Ireland.”

Understanding and curiosity came into Marie’s eyes. “Whose funeral?” she asked.

“My moth—what does that have to do with anything?”

“I was curious. You don’t have the sense of someone close to you having died.”

“We weren’t close,” I said shortly. This was the second time this morning I’d said something about my family. I was breaking all sorts of rules for me. I really needed sleep. The waitress came by and slid Gary’s breakfast in front of him. Three eggs, fried, over a slab of steak, three huge pancakes, hash browns, bacon, sausage and a side of toast. I got full just looking at it. Gary didn’t pick up his fork, and after a couple seconds I frowned at him.

The big guy was actually pale, gray eyes wide under the bushy eyebrows. He stared at Marie like she’d turned from a golden retriever puppy into a king cobra. I did a double-take from him to her and back again, wondering what was wrong. “Gary?”

“Don’t worry,” Marie said, very softly. “I don’t see anything about you.”

Gary focused on his plate abruptly, cutting a huge bite of steak and eggs to stuff into his mouth. His eyebrows charged up his forehead defiantly, like he expected Marie to make an addendum to her comment. Her mouth twitched in a smile, but she didn’t say anything else.

“Does being a banshee have anything to do with why what’s-his-face wants you?” I reached over and snitched a piece of bacon off Gary’s plate. He noticed, but didn’t stop me.

“Cernunnos. I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Because, what, the Hunt isn’t scary enough without you?” I heard myself capitalize the word, and wondered why I’d done it.

“I haven’t had a conversation with him about it,” she said. “I don’t really know what he wants me for.”

“So how do you know he wants you?”

“Having a pack of ghost dogs and rooks and a herd of men on horseback chase you down the street gives a girl a pretty good idea that she’s wanted for something,” Marie said acerbically.

I had the grace to look embarrassed. “Okay, it was a stupid question.”

“Couldn’t it have been vampires?” Gary asked wistfully around a mouthful of hash browns. “Vampires are at least kinda sexy. What’s sexy about packs of dogs and birds? No such thing as rooks around here anyway.”

“They come with Cernunnos.” Marie kept saying these things like they were obvious.

“Marie, what are you?” I asked. She shrank back, looking surprisingly guilty. “Banshees are fairies,” I said. “Please don’t tell me you’re a fairy.”

“Not much of one, anyway,” she said to her orange juice, “or I wouldn’t be able to hide on holy ground, or use that knife.” She nodded at the butterfly knife I’d set on the table at my elbow. I picked it up without opening it and looked at her curiously. “Iron,” she said, “steel.”

“What about it?”

Have you ever had someone look at you like you were a particularly slow child? That’s the look Marie gave me. Come to think of it, Captain Steve had given me that same look earlier. I was beginning to think I should be offended. Marie interrupted before I got up the energy. “You really don’t know anything about the mystical, do you?”

“Why should I?”

“I thought Indians knew that kinda stuff,” Gary put in. I looked at him incredulously. He shrugged. “Well, you got all them powwows and stuff. What were you doing during the powwows?”

“Reading books on evolution,” I said through my teeth. Apparently that tone was scarier than the one I’d employed earlier, because Gary closed his mouth around another forkful of food with an audible smack. “That’s like saying all big guys are stupid, or all blondes are dumb, or—”

Gary pushed his food into one cheek, squirrel-like, and nodded. “Yeah, yeah, I gotcha. It was a joke, Jo. Jeez.”

“Perpetuating stereotypes through joking isn’t funny.”

“I’m sorry.” Gary sounded like he meant it. I frowned at him, then sighed and put my face in my hands.

“Forg—fuck that hurts!” I jerked my hand away from my cheek, expecting to see fresh new blood on my palm. I was spared that, at least. This was not my morning.

“The Celtic fair folk aren’t supposed to be able to bear the touch of iron,” Marie explained, once more interrupting my downward spiral of misery before it began. “Not even their gods. And I don’t know what I am, not in the way you’re asking the question. I’m an anthropologist with an unusual skill.”

“Skill? Like you learned it deliberately?”

Marie shrugged. “Talent, skill. I hesitate to call it a gift.” She caught Gary’s eye, and flashed a quick smile. “Although I could make a killing in insurance,” she said quickly. He snapped his mouth shut around another bite of food, beaten to the punch. I grinned. It made my cheek hurt. “In any other aspect,” Marie said, “I’m ordinary.”

“You are not,” I said, “ordinary.” My voice came out about six notes lower than normal. I felt color rush to my cheeks, which made the cut throb furiously. Marie’s mouth quirked in a crooked little smile. I bet even a smirk would look good on her.

“Thank you,” she said, easily enough to make my blush fade. I could feel Gary looking at me. I very carefully didn’t look at him.

“You’re welcome.” I lifted my hands to my temples and held my head. My shoulders ached. I needed a hot shower, a massage from a tall bronze guy named Rafael and about sixteen weeks of sleep. “All right, look. Let me take you at face value.”

Marie pulled a wry little moue, and Gary let out a deep chuckle. I felt a little smile creep over my face and split my cheek open again. I was going to bleed all day long. How fun. “Let me take your story at face value,” I amended. Marie laughed.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I was about eight when I figured out being taken at face value meant people were going to let me get by on my looks. If I’d had a different family I’d never have learned to think at all. Why would I need to?” The way she said it made me think she’d used her looks just as much as she’d used her brain to get where she was in life. There are beautiful people who know they’re beautiful, and use it like a weapon. I got the impression Marie used it as a tool. I couldn’t blame her.

“You’re being hunted by an ancient Irish god who wants you for his own nefarious purposes. Dead or alive will do. Have I got that right?”

Marie nodded.

“Right,” I said. This was completely insane. “How can I help?”

“He’s gaining power,” she said. “He will until the sixth, and then he’ll be banished to the otherworlds until Samhain. It’s the cycle he’s bound to.”

“Until what?”

“Halloween,” Gary and Marie both said. I looked at Gary. He shrugged and ate a piece of bacon. I pressed my eyes shut, wished it didn’t make my cheek hurt, and opened them again to look at Marie. She kept right on not looking as if she were completely insane.

“Just out of morbid curiosity—the sixth?”

“It’s the last day of Yule.”

I wished she would stop saying things like that as if it explained everything. I waved my hand in a circle, eyebrows lifted as I shook my head. Apparently the connotation of “yeah, so?” got through to her, because she sat back with a quiet sigh.

“Yuletide used to be very important in the Catholic Church. It’s the twelve days from Christmas to the sixth of January, and it marks the days of Cernunnos’s greatest power as he rides on this earth.”

“You’re telling me some random church holy days hold sway over an immortal god.” That time the sarcasm came through loud and clear, whether she was pretty or not. Her shoulders drooped.

“Those dates are closely tied to the solstice and the half-moon cycle after the solstice,” she said very quietly. “There aren’t any written records, of course, but I’ve always suspected the lunar cycle had more to do with when the Hunt rode than our calendar.”

“Oh.” I stopped being so sarcastic, the wind taken out of my sails. “Okay. I guess I can buy that.” Insofar as I was buying any of it. What was I doing here? “So what’s he want with you?”

Marie shook her head again. “I don’t know. I’ve been trying to stay away from him since Halloween, traveling all over the place. He kept finding me.” She shivered, wrapping her arms around herself. “All over the world. So I kept moving. But since Christmas I’ve been…this morning was the closest. I’d never actually seen him before. Never touched him.” She dug into her pocket and pulled the tooth out, putting it on a napkin on the table. “I didn’t even think something like this could be done to him.”

I stared at the tooth. “Eww. I didn’t know you’d picked it up.”

“While Gary was bandaging your face,” she said. “It’s a good thing to have. It gives us a physical connection to him. It may help us build shields against him.”

“Build what?” Gary asked. He’d cleared two-thirds of his plate. I reached over and stole a piece of bacon. He stabbed at my hand with his fork, but not like he meant it. The bacon was really good, so crunchy it practically melted. I stole another piece. “Cut it out,” Gary said. “I gotta watch my figure.”

“Shields,” Marie said. “Protection.”

“How do I protect you from a god?” I demanded. “I could get you thrown in jail for a few days. The sixth is what, three days? He can’t get through steel bars, right?”

“Two. It’s the fourth. And no, he can’t, but he could send someone who could,” Marie pointed out.

I shrugged, hands spread out. “Fourth, okay, whatever, it’s morning, you’ve still got all day to get through. That makes three days. Anyway. So what do I do?”

“Build me a circle of protection.”

“Uh-huh,” I said. “You want me to get a bunch of people to stand around you with iron crosses and this tooth and only let people you say are okay come in?”

“No, a—” Marie broke off with an ugly little gasp. I was looking right at her. I couldn’t mistake the color draining from her eyes. All that gorgeous deep blue spilled away, even eating away the pupil, until there was just blind white, and then she blinked. Color came back to her eyes, but not the right color. Her irises were all black, tinges of gold and blue around where the pupils ought to be. She blinked a second time, and blanched, then spoke in a very thin voice, staring straight at me.

“You’re going to die.”

CHAPTER FOUR

An announcement of impending death sure could take a girl’s appetite away. The knot of weary tension in my stomach contracted around the bites of bacon I’d stolen, cold threads of terror seeping down like a net. The rational part of my mind dismissed it all.

That would have been a comfort, except it appeared a lot more of my mind wasn’t rational. I seized on to panic and ran with it. All of a sudden I understood why Gary had been so uncomfortable with Marie’s gift. I clenched my teeth together, wondering why my hands were so cold. I wrapped them around my coffee cup and tried to stare at Marie without looking at her eyes. They were still unnervingly black, and I never wanted to see anything like that again.

“Something just changed,” she went on, still in a whisper. “You weren’t supposed to die, but now you’re going to.” There was conviction in her voice. She didn’t blink. Her eyelashes were as black as her eyes, not brown like her hair.

“So I’m going to die because of you.” I meant to sound challenging. Somehow it came out sounding more like a frightened little girl. Marie nodded, dismay vivid even in her altered gaze.

“Well, fuck that.” There. That sounded more like me. I stood up. “I’d like to help you, lady, but not enough to die for you.” Great. Now I sounded like Gary. He scrambled to his feet beside me, favoring Marie with an unhappy glance. I dug into my fanny pack and came up with a five dollar bill and three Irish punts. I threw the five down and picked up my butterfly knife. “Gary, cover the rest, will you?” I headed for the door ignoring the sudden bubble of sickness that erupted in my stomach again, just as it had when I’d seen Marie through the plane window. Gary, thank God, didn’t argue, just pulled out his wallet.

“Wait!” Marie’s voice came after me, plaintive. I didn’t stop. “Maybe I can help you!”

I turned around in the door. The tired blonde behind the counter looked a little more awake, watching first me, then Marie. “You think you can help me?” I demanded. “Weren’t you the one just telling me I was going to die?”

Marie stood up. “The possibilities changed very quickly,” she said softly. “If I’m with you, maybe I can see them change again. Maybe I’ll know what you should do to avoid dying.” She tossed a bill onto the table, too, as Gary came around it. The waitress was going to get a major tip.

“What are you, a banshee or a precognitive?” I asked. I was still in the door having the conversation. That wasn’t a good sign, as far as I was concerned.

“To see someone’s death, you have to be precognitive,” Marie said. “I thought you didn’t believe in any of that.”

“Just because I don’t believe doesn’t mean I don’t know the names.” I put both hands on the door’s center bar and shoved my way out of the diner, listening to the bells chime as the door swung shut behind me.

A SCUD missile hit me in the chest. I smashed back into the door, glass shattering with the impact. The center bar hit me in the small of the back, and I rotated around it. God did not intend anybody’s back to be used in that fashion, except maybe those bendy Cirque du Soleil acrobats.

Unfortunately for me, I wasn’t one of those acrobats. I flipped over the bar and slammed the back of my head against the still-intact glass in the lower half of the door, then collapsed on my face onto glass-littered linoleum. My cheek split open again as I hit the floor. More glass fell into my hair and onto the floor around me, sounding like falling stars.

The possibility of passing out crossed my mind, but I just had to see who was running around suburban Seattle with a SCUD. Lifting my head told me all sorts of painful things about muscles in my neck that I didn’t want to know. I clenched my teeth together on a whimper. Whimpering seemed undignified. No one ever whimpered in the movies after getting smashed through a glass door.

There was no missile launcher in the parking lot. Instead there were very large hooves a few feet outside the destroyed door. While I waited for that to make sense, they disappeared and reappeared again, moving forward.

Have you ever heard the sound of tearing metal? It’s a high-pitched scream that sets your teeth on edge and lifts the hairs on your arms. It’s the kind of sound a mechanic gets used to, but in the diner, along with the rattle of more breaking glass and some other noises I couldn’t place, it was incomprehensible. The hooves disappeared again, and I wondered where my knife had gone. Glass and dust and spikes of wood fell down around me.

The floor wrenched apart with a shriek of sound as one of the enormous hooves smashed down inches from my face. I twisted my head up, whimpering again at the pain in my neck. An extraordinarily broad chest was about four feet above my head. It reared up, which seemed wrong somehow, but I was too busy rolling frantically out of the way to give it more thought. Glass crunched under my arms as I rolled. I felt tiny cuts opening up on my arms.

I ended up sitting with my back against the counter, gasping while the rest of the world caught up with me. The tired blonde behind the counter shrieked with the regularity and volume of a car alarm. Gary had moved maybe two feet from the table, which suggested that despite the slow clarity I was experiencing, the attack had happened very quickly. Marie was shouting in a language I didn’t understand. It didn’t sound like Italian.

The horse made more sense now, for some nebulous value of the word sense. It had been able to rear up because after it kicked me in the chest it had torn out the entire door structure, and part of the roof had fallen down. The rest of the roof was on fire. I wasn’t sure how that had happened, but it didn’t seem to bother the horse.

Horse is such a limited word. The beast in the diner had the grace and delicacy of an Arabian and the size of a Clydesdale, multiplied by two. It shimmered a watery gray, bordering on silver, the color so fluid I thought I might be able to dip my hand in it. Despite myself, my gaze jerked up to its forehead. There was no spiral horn sprouting there, but I wouldn’t have been surprised if there had been. It was Plato’s horse, the ideal upon which all others are based.

It was trying to kill me, and all I could do was admire it.

Then it screamed, shrill and deep all at once. The blonde behind the counter shut up, but I screamed back, a sort of primal response without any thought behind it.

Just for a moment, everything stopped.

There was a rider astride the gray, arrested in motion by my scream. He wore gray himself, so close to the color of the horse I could barely tell where one ended and the other began. The reputed Native American belief that white men on horseback were one exotic creature suddenly seemed very plausible.

The rider turned his head slowly and looked at me. His hair was brown, peppered with starlight, and crackled with life, as if touching it would bring an electric shock. It swept back from a massively sharp widow’s peak, and was held in place by a circlet. His face was a pale narrow line, all high cheekbones and deep-set eyes and a long straight nose.

The impression he left was of living silver. I locked eyes with him, expecting to see that liquid silver again. Instead I met wild-fire green, a vicious, inhuman color, promising violence.

He smiled and reached out a hand, inviting me toward him. His mouth was beautiful, thin and expressive, the curve of teeth unnervingly sharp, like a predator’s. I pushed up the counter, using it to brace myself, and wet my lips. Marie was right. I was going to die. The rider wanted my soul and I was going to give it to him without a fight because of that smile and those inhuman eyes. I took a step toward him.

The second SCUD of the morning hit me in the ribs and everything started to move again. I slammed into the floor under Gary’s weight, sliding across linoleum and a zillion sharp pieces of glass. We stopped when my head hit the far wall. I opened my eyes to find the butterfly knife lying against the wall a few inches away from my nose. The horse screamed again and reared back, missing my head by half an inch as he crashed back to the floor.

Gary’s breath smelled like syrup and bacon. “Are you outta your mind?” He popped up onto his knees and hauled me to mine by a fistful of shirt at the back of my neck. I snatched up the knife as the horse smashed down again, right where my head had been. I looked up at the rider, and the horse kicked me in the ribs with a toe. I felt the bone crack inward, and didn’t even manage a scream, just a pathetic little grunt.

From a very long way away, I heard Marie scream a warning, in English this time. Before I could react, Gary hauled me over backward. A tip of silver glittered through the air where my throat had been. The rider looked genuinely startled before his eyes narrowed and he urged the horse farther into the diner. They were huge, taking up all the room, all the air. I gasped and scrambled to my feet, clutching Gary’s arm with one hand and my ribs with the other. Breathing hurt.

“Leave them alone.” Marie sounded thin and tired and at the end of her bravery, but there she was at my side, looking up at the rider with a set chin. “I’ll go with you. Just leave them alone. They were only trying to help.”

I let go of Gary’s arm and shouldered forward. The rider watched me. Neither Gary nor Marie moved. Behind me I heard the blond waitress fumbling with the phone, and her panicked, “Hello? Police? Hello?”