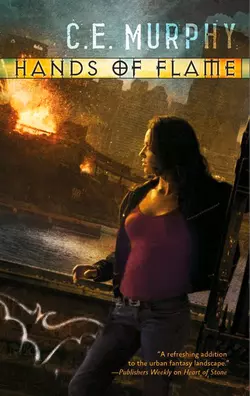

Hands of Flame

C.E. Murphy

War has erupted among the five Old Races, and Margrit is responsible for the death that caused it. Now New York City's most unusual lawyer finds herself facing her toughest negotiation yet. And with her gargoyle lover, Alban, taken prisoner, Margrit's only allies–a dragon bitter about his fall, a vampire determined to hold his standing at any cost and a mortal detective with no idea what he's up against–have demands of their own.Determined to rescue Alban and torn between conflicting loyalties as the battle seeps into the human world, Margrit soon realizes the only way out is through the fire. . . .

Praise for C.E. MURPHY and her books

THE NEGOTIATOR

Hands of Flame “Fast-paced action and a twisty-turny plot make for a good read … Fans of the series will be sad to leave Margrit’s world behind, at least for the time being.” —RT Book Reviews

House of Cards “Violent confrontations add action on top of tense intrigue in this involving, even thrilling, middle book in a divertingly different contemporary fantasy romance series.” —LOCUS

“The second title in Murphy’s Negotiator series is every bit as interesting and fun as the first. Margrit is a fascinatingly complex heroine who doesn’t shy away from making difficult choices.”

—RT Book Reviews

Heart of Stone “[An] exciting series opener … Margrit makes for a deeply compelling heroine as she struggles to sort out the sudden upheaval in her professional and romantic lives.” —Publishers Weekly

“A fascinating new series … as usual, Murphy delivers interesting worldbuilding and magical systems, believable and sympathetic characters and a compelling story told at a breakneck pace.”

—RT Book Reviews

Author’s Note

Leaving a world is hard to do. Three books in, and as a writer you’ve really gotten into its depths and people’ve begun to ask interesting questions that make you think of things you never thought of before. There are backstories to fill in and futures to consider, and they rarely settle back to sleep without putting up a bit of a fight.

This is the second time I’ve finished a trilogy, and the second time that I’ve been left thinking, “There are still a lot of books I could write for this world….” E-mail has suggested that people might be glad if I did—and someday I very probably will.

But now it’s back to the Walker Papers for me! I’ve written a lot of books since Coyote Dreams, and I miss Jo and the gang, so I hope I’ll see all of you there in a few months’ time.

Catie

Hands of Flame

C.E. Murphy

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

For Sarah

who was the first to want

an Alban of her own

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are, as usual, due to both my agent,

Jennifer Jackson, and my editor,

Mary-Theresa Hussey, for their insights.

It turns out Matrice really did read the acknowledgments in the last two books, and it was with great relief that I discovered she thought I’d gotten it almost entirely right this time.

I’ll never be able to say thank you enough to cover

artist Chris McGrath, or the art department, who

have worked together to give me gorgeous books

to show off.

Ted (and my parents, and my agent, but mostly

Ted, since he’s the one who has to live with me)

did a remarkable job of keeping me more or less

functional during the writing of this book, and that

was no easy task. I love you, hon, and I couldn’t do

this without you.

ONE

NIGHT MARES DROVE HER out of bed to run.

She’d become accustomed to another sort of dream over the last weeks: erotic, exotic, filled with impossible beings and endless possibility. But these were different, burning images of a man’s death in flames. Not by flame, but in it: the color of her dreams was ever-changing crimson licked with saffron, as though varying the light might result in a happier ending.

It never did.

The scent of salt water rose up, more potent in recollection than it had been in reality. It tangled brutally with the smell of copper before the latter won out, blood flavor tangy at the back of her throat. She couldn’t remember if she’d actually smelled it, but her dreams tasted of it.

Small kindness: fire burned those odors away, whether they were real or not. But that left her with flame again, and for all that she was proud of her running speed, she couldn’t outpace the blaze.

There was a dragon in the fire, red and sinuous and deadly. It battled a pale creature of immense strength; of unbreaking stone. A gargoyle, so far removed from human imagination that there were no legends of them, as there were of so many of their otherworldly brethren.

Between them was another creature: a djinn, one of mankind’s imaginings, but not of the sort to grant wishes. It drifted in its element of air, clearly forgotten by dragon and gargoyle alike, though it was the thing they fought over. It faded in and out of solidity, impossible to strike when it didn’t attack. But there were moments of vulnerability, times when to do damage it must become part of the world. It became real with a weapon lifted to strike the dragon a deathblow.

And she, who had been nothing more than an unremembered observer, struck back. She fired a weapon of absurd proportions: a child’s watergun, filled with salt water.

The djinn died, not from the streams of water, but from their result. The gargoyle pounced, moving as she had: to save the dragon. But salt water bound the djinn to solidity, and heavy stone crushed the slighter creature’s fragile form.

The silence that followed was marked by the snapping of fire.

Margrit ground her teeth together and ran harder, trying to escape her nightmares.

She struggled not to look up as she ran. It had been almost two weeks since she’d sent Alban from her side, and every night since then she’d been driven to the park in the small hours of the morning. Not even her housemates knew she was running: she was careful to slip in and out of the apartment as quietly as she could, avoiding Cole as he got up for his early shift, leaving his fiancée asleep. It was best to avoid him, especially. Nothing had been the same since he’d glimpsed Alban in his broad-shouldered gargoyle form.

Margrit could no longer name the emotion that ran through her when she thought of Alban. It had ranged from fear to fascination to desire, and some of all of that remained in her, complicated and uncertain. Hope, too, but laced with bitter despair. Too many things to name, too complex to label in the aftermath of Malik al-Massri ‘s death.

Not that the inability to catalog emotion stopped her from trying. Only the slap of her feet against the pavement, the jarring pressure in her knees and hips, and the sharp, cold air of an April night, helped to drive away the exhausting attempts to come to terms with—

With what her life had become. With what she’d done to survive; what she’d done to help Alban survive. To help Janx survive. Her friends—ordinary humans, people whose lives hadn’t been star-crossed by the Old Races—seemed to barely know her any longer. Margrit felt she hardly knew herself.

She’d asked for time, and that, of all things, was a gargoyle’s to give: the Old Races lived forever, or near enough that to her perspective it made no difference. They could die violently; that, she’d seen. But left alone to age, they carried on for centuries. Alban could afford a little time.

Margrit could not.

She made fists, nails biting into her palms. Tension threw her pace off and she wove on the path, feet coming down with a surety her mind couldn’t find. The same thoughts haunted her every night. How much time Alban had; how little she had. How the life she’d planned had, in a few brief weeks, become not only unrecognizable, but unappealing.

Sweat stung her eyes, a welcome distraction. Her hair stuck to her cheeks, itching: physical solace for an unquiet mind. She didn’t think of herself as someone who ran away, but she couldn’t in good conscience claim she ran toward anything except the obliteration of memory in the way her lungs burned, her thighs burned.

The House of Cards burned.

“Dammit!” Margrit stumbled and came to a stop. Her chest heaved, testimony to the effort she’d expended. She found a park bench to plant her hands against, head dropped as she caught her breath in quiet gasps that let her listen for danger. She’d asked Alban for time, and couldn’t trust he glided in the sky above, watching out for her, especially at this hour of the morning. Typically, she ran in the early evenings, not hours after nightfall. There was no reason to imagine he’d wait on her all night. Safety in the park was her own concern, not his.

Which was why she couldn’t allow herself to look up.

If she would only bend so far as to glance skyward, he would have an excuse to join her.

Alban winged loose circles above Central Park, watching the lonely woman make her way through pathways below. She was fierce in her solitude, long strides eating the distance as though she owned the park. It was that ferocity that had drawn him to watch her in the first place, the reckless abandon of her own safety in favor of something the park could give her in exchange. He thought of it as freedom, pursued in the face of good sense. It encompassed what little he’d known about her when he began to watch her: that she would risk everything for running at night.

That was what had given him the courage to speak to her, for all that he’d never meant it to go further than one brief greeting. It had been a moment of light in a world he’d allowed to grow grim with isolation, though he hadn’t recognized its darkness until Margrit breathed life back into it.

And now he hungered for that brightness again, a desire for life and love awakened in him when he’d thought it lost forever. He supposed himself steadfast, as slow and reluctant to change as stone, but in the heat of Margrit’s embrace, he changed more quickly and more completely than he might have once imagined. He had learned love again; he had learned fear and hope and, most vividly of all, he had learned pain.

He thought it was pain that sent Margrit running in these small hours. She’d asked him to stay away while she came to grips with it, but she hadn’t said how far away, and he was, after all, a gargoyle. He watched over her every night from dusk until dawn, even when that meant sitting across the street on an apartment-building roof, patiently watching lights turn off in her home as she and her housemates retired to bed. He ignored the others who had demands on his time: Janx, the charming dragonlord who’d lost his territory in the fight that had ended Malik al-Massri’s life; who had, in fact, nearly lost his own life and who was still healing from the wounds Malik had dealt him. Alban had helped him escape, had brought him below the streets, into the vigilante Grace O’Malley’s world. Janx was safe there, but Grace and the children she helped were not, not so long as Janx remained. And yet Alban took to the skies each night, watching Margrit instead of resolving the conflicts that grew in the tunnels beneath the city.

If it were not entirely against a gargoyle’s nature, Alban might say he was hiding from those responsibilities by insisting on another. But then, he’d lost his sense of what was, in truth, a gargoyle’s nature, and what was not. A few months earlier he would have answered with confidence that a gargoyle was meant to keep to a well-known path, to be a rock against the changes forced by time. Now, though, now he had lost his way, or found it so reshaped before him that he had to gather himself before he could move forward. He hadn’t wanted to leave Margrit when she said she needed time, but suddenly he understood. Distress might be eased when shared, but the need to understand herself—or himself, now that he saw it—could be as necessary a step toward recovery. To edge back and rediscover the core of what he thought he was, without outside influence, might be critical.

And the secluded nights did give him time to think. No: time to remember. Remembering was a gargoyle’s purpose in existing, and for the past two weeks he would have given anything to be unburdened by that particular gift borne by his people.

Margrit sprinted away from a park bench without looking up, and Alban felt a twist of sorrow. Not anything: there was, it seemed, at least one thing he would not give up under any circumstances. He had killed to protect Margrit Knight, not once, but twice.

It might have meant nothing—at least to the other Old Races—had he taken human lives. But he’d destroyed a gargoyle woman with full deliberation, and a djinn thanks to devastating mistiming. Those were exiling offenses, actions for which he could—would, should—be shunned by his people. For all that he’d exiled himself centuries earlier on behalf of men not of his race, knowing he now inexorably stood outside the community he’d been born to cut more deeply than he’d thought it could. And for all of that, what disturbed him the most was the unshakable certainty that, given another chance, given identical circumstances, he would make the same choice. If he could alter the paces of the play, he would, yes; of course. But if not, if the same beats should come to pass, he would choose Margrit and the brief, shocking impulses of life she brought into his world.

He was no longer certain if he’d stopped knowing himself a long time ago and was only coming back to his core now, or if Margrit Knight had pulled him so far from his course that he had nothing but new territory to explore. He would have to ask Janx or Daisani someday; they had known him in his youth.

Startling clarity shot through him, the disgusted voice of another who’d known him when he was young: You were a warrior once. You could have led us. Biali hadn’t meant it as a compliment, his shattered visage testimony to the battle skills Alban had once had. Maybe, then, the impulse to make war had always been in him, buried during the centuries of self-imposed exile. Maybe the ability to kill had waited until it was needed, or wanted: a vicious streak through a heart of stone.

Too many thoughts circling near the same ideas that had haunted him through Margrit’s sleepless nights. Alban shook himself, leaping from the treetops to follow her, certain of this, if nothing else: he would not let the human woman come to harm, not after the changes she’d wrought in himself and his world. To lose her now would undo the meaning of everything, and that was a price too dear to be paid.

An impact caught her in the spine and knocked her forward. Margrit shouted with outraged surprise, hands outspread in preparation for breaking a fall she couldn’t stop. But thick arms encircled her waist, and the ground fell away with a sudden lurch. A body pressed against hers, muscle shifting and flexing in a pattern that might have been erotic, had Margrit’s incredulous anger not drowned out any other emotion, even fear. She struggled ineffectively, swearing as her captor soared above the treetops. “Alban?”

“Sorry, lawyer.” The words spoken into her hair were gargoyle-deep, but not Alban’s reassuring rough-on-rough accent. There was no sincerity in the apology, only a snarled mockery made of its form. “Hate to use you as bait, but I can’t do this out in the open.”

“Biali?” Margrit’s voice broke into a rarely used register as she twisted, trying to get a look at the gargoyle who’d swept her up. Her hair tangled in her face, blinding her. “What the hell are you doing?”

An edged chuckle scraped over her skin. “Getting Korund’s attention.”

“You couldn’t use a telephone like a normal person?” Margrit twisted harder and looped an arm around Biali’s shoulders, so she was no longer wholly reliant on his grip around her waist. He grunted, adjusting his hold, and gave her a baleful look that she returned with full force. “This was your idea.”

Exasperation crossed Biali’s face so sharply that for a moment it diluted Margrit’s anger. That was just as well: they were passing rooftops now, and pique might get her dropped from the killing height. With anger fading, she realized she had precious moments that could be better spent in investigation than in argument. “What do you want from Alban?”

“Justice.” Biali backwinged above an apartment building, landing on messy blacktop. He released Margrit easily, as though he hadn’t abducted her. She bolted for the rooftop door, though seeing its rusty lock stopped her before she reached it. She spun around, running again before she’d located the fire escapes, but Biali leapt into the air and cruised over her head, landing between her and the ladders. “Don’t make me have to hit you, lawyer.”

Margrit reared back, staying out of the gargoyle’s reach, though she doubted she could move fast enough to avoid him if he wanted to catch her again. For the moment, though, he simply crouched where he was, wings half spread in anticipation, broken face watching Margrit consider her options. He wore chain links around his waist, a new addition to the white jeans she’d seen him in before. Wrapped too many times to be a belt, the metal made a peculiarly appropriate accessory for the brawny gargoyle, enhancing his thickness and the sense of danger he could convey. Margrit found it disquieting, the dark iron twinging as a wrongness, but that, too, added to the effect.

Any real expectation of escape blocked, she resorted to words for the second time. “Justice for what?”

“Ausra.”

Dismay plummeted Margrit’s belly. The name conjured as many demons as flame-haunted dreams did. Ausra Korund had styled herself Alban’s daughter, though in truth she was the child of his lifemate, Hajnal, and the human who had captured her. Driven mad by her own heritage, Ausra had lain in wait for literally centuries, stalking Alban, waiting for a chance to destroy him. She had been Biali’s lover, and very nearly Margrit’s death. The Old Races were meant to think Ausra’s fate lay in Margrit’s hands. Only she and Alban knew the truth: that Alban had taken Ausra’s life to save Margrit’s.

Only they, and, it seemed, Biali. Margrit felt all her years of courtroom training betray her as her mouth tightened in recognition. Dark humor slid through Biali’s expression. “Everything make sense now, lawyer?”

Margrit drew in breath to respond and let it out again in a shriek as a flash of white darted over her head. Biali launched himself skyward to meet Alban, all attention for Margrit lost.

They crashed together with none of the grace she was accustomed to seeing from the Old Races. Too close to the rooftop to keep their battle aerial, momentum and their own weight slammed them to the blacktop. Margrit staggered with the impact and ran for shelter, putting herself against the rooftop access door. It seemed impossible that no one would come to see what the sound had been, and each roll and thud the combatants shared made it that much more likely. She didn’t dare shout for the same reason, but she pitched her voice to carry, fresh fear and anger in it: “Are you crazy? Somebody’s going to come!”

Neither gargoyle heeded her, too caught up in their private conflict to respond to sense. Biali lifted a fist and drove it down like the rock of ages. Alban flinched just far enough to the side that the blow missed. The rooftop shook again and Margrit skittered forward a few feet, sure that interfering would be useless, but driven to try. “Alban, stop! He grabbed me to make you come after him! Just get out of here!”

For a moment it seemed he’d heard her, an instant’s hesitation coming into his antagonism. Biali took advantage with a backhand swing so hard the air whistled with it, his fist a white blur against the graying sky. Alban spun, dizziness swaying his steps. An appalled fragment of Margrit’s attention wondered how hard a hit that was, to stagger a gargoyle. A human jaw would have been pulverized.

Her gaze locked on the shattered left half of Biali’s face; the ruined eye socket that in gargoyle form was all rough planes worn smooth by time. Alban had done that centuries earlier, and if the blow he’d just taken hadn’t conveyed similar damage to his own face, Margrit couldn’t imagine what strength had been necessary to destroy Biali’s features.

As Alban reeled and regained his footing, Biali backed away, unwinding the length of chain from around his waist. Unwanted understanding churned Margrit’s stomach as the stumpy gargoyle knotted one end and began to swing it. It wasn’t an adornment of any sort. It was a weapon, and more, a prison.

Of all the Old Races, only gargoyles had ever been enslaved.

Margrit let go a wordless shout of warning that forgot the need for silence. Alban responded, flinching toward her as if he would protect her from whatever she feared, but too late: Biali released the chain, sending it clattering toward Alban. Margrit sprinted toward them, her only thought to break the chain’s trajectory, regardless of the cost to herself. She would heal from most injuries: that was the gift another of the Old Races had given her, and for Alban’s freedom she would risk her fragile human form against the dangerous weight of metal.

But she’d taken herself too far from the fight, her safe haven now a detriment. Crystal-precise clarity played the seconds out, letting her see how the chain left Biali’s hands entirely, flying free. Alban recognized the threat an instant too late, wings flared and eyes wide with comprehension and furious alarm. Metal wound around his neck and his hands clawed against it, desperate to snap the chain and shake himself free.

Dawn broke, binding iron to stone.

TWO

MARGRIT’S HEARTBEATS COUNTED out an eternity, incomprehension making a statue of her as if she, too, was one of the gargoyles, frozen in time. Then the need to act paralyzed her, useless choices rendering her as still as astonishment had.

Her impulse was to dart forward, to claw the chains away from Alban’s throat just as he’d tried to do. To pound on his chest and demand he wake up, for all that she knew sunlight held him captive and only darkness would release him from stone. Failing that, she wanted to somehow scoop him up and carry him to safety, far away from Biali and his plots. All were physically impossible, laughable in their naiveté. Even if she could somehow remove him from the rooftops, Margrit wasn’t certain she could loosen the chains that bound him.

Memory surged with the thought, twisted and half-shadowed and not her own. The half-breed Ausra’s memories of Hajnal, her mother, bound by iron, pain driving her mad. Iron became part of stone when transformation took a gargoyle at dawn or dusk, and could only be released by the one who’d set the chains in place. Hajnal had never been free again, and her death had poured memories into Ausra’s unprotected infant mind. It was more agony than Margrit had ever wanted to know.

She shuddered, pushing the alien memories away. What little she knew about enslaved gargoyles had suggested manacles, not iron chain wound around a stony neck. Maybe, if she could get Alban away from Biali, she might free him by simply unwinding the chains.

It would have been an elegant solution, had it not relied on moving a seven-foot-tall statue off a twentieth-story rooftop. Margrit had no idea how much he weighed in stone form; easily a ton or two. She flattened her hands against her hips, searching for a cell phone she should have been carrying and wasn’t. Cole and Cameron would rail at her for that, if she admitted it to them. Even if she had the phone—and she should; running in the park at night was dangerous enough without at least carrying some form of communication—there was no one to call. The only obvious answer was her soon-to-be employer, and the prospect of offering Alban, frozen in stone and chains, to Eliseo Daisani, sent a cold shudder through her.

The door behind her banged open and Margrit swallowed a yelp of surprise as she turned to face an irate man, whose ring of keys suggested he was the building manager. “What the hell is goin—What the hell are those?” His attention snapped back and forth between the gargoyles and Margrit so swiftly it looked headache inducing.

She offered a lame smile. “Somebody’s sculpture project?”

“Somebody like you?” The man was big enough to be physically threatening, but he kept his distance, as though the gargoyles behind Margrit might come to life and protect her. She wanted to assure him, blithely, that he was safe until nightfall, but instead swallowed a hysterical laugh and shook her head.

“I came up to see what all the noise was.”

The building manager squinted. “From where? You’re not a tenant.”

Margrit couldn’t imagine how Biali had managed to choose a building where the building manager knew his tenants, but she had the urge to turn around and scold him for it. “I’m visiting. I got up early to go for a run and heard the noise. My friend called you.”

The manager’s eyebrows unbeetled a little. “She didn’t mention a guest. ‘Course, she usually doesn’t. How were you planning on getting back downstairs?” He jangled his keys, still looking sour, but no longer as if he suspected Margrit was to blame for the gargoyles.

She clapped her hands over her mouth, eyes wide with dismay. “Oh, God, I didn’t even think of that. Wow, I’m such an idiot. Thank goodness you came up here or I’d be stuck all day. Thank you! You totally saved my life!” She felt her IQ dropping with the breathless exclamations, but the manager looked increasingly less dour.

“You should think things through more carefully.” Chiding done, he looked beyond her at the gargoyles and sighed explosively. “Well, shit. I’m going to have to get demolition guys in here to get rid of those things.”

Horror clenched a fist around Margrit’s heart. “But they’re so cool. I bet you could make a buck or two letting people up here to see them for a while before you got rid of them. Besides, somebody in the building must’ve done them, right? I mean, unless helicopters swept through in the middle of the night and dropped them off.”

The manager twisted his mouth. “Or they flew here.”

Margrit laughed, high thin sound of nerves. “Yeah, which would be totally freaky.” A law-school education, she thought with despair, and she was relegated to totally freaky. “So if somebody got them up here, he must have a way to get them back out, right?”

“Do you know how many tenants I’ve got? I don’t want to knock on every door asking who the damned fool who put a couple monsters on the roof is.”

Margrit bounced on her toes, putting on her best helpful smile. “Look, I could do it for you. I’ll wait a little while to be sure people are getting up so I don’t disturb them, and you’ve got to have a million things to do in a building this size, and I don’t mind lending a hand. Makes me feel useful as a visitor, you know? I’m Maggie, by the way.” She stepped forward to offer a hand, wincing at the nickname she never used. Margrit had a plethora of short names, and she used one no one else did: Grit. But Maggie was close enough to her name that she’d remember to respond to it, and since she was on the roof under false pretenses, it seemed wiser not to offer her real name.

The building manager shook her hand automatically. “Hank. You’re not Rosita’s usual type, Maggie.”

Margrit knotted her fingers in front of her stomach, hoping she looked winsome instead of nervous. She hadn’t known she was potentially Rosita’s type when she’d pinned her presence on a “friend,” but she was unexpectedly interested in the answer to, “Better or worse?”

“Better. She’s usually into—Well, look, it doesn’t matter. You seem like a nice girl, and I could use the help. Jesus, what kind of idiots …”

“I’ll totally take care of it,” Margrit promised. “Just don’t call any demolition guys until I’ve talked to everybody, okay? They’re too cool to smash up. Somebody’ll want them.”

“Yeah, all right. Come on.” Hank turned away, opening the door. Margrit’s shoulders slumped with relief before she put Maggie’s perky smile back on and followed him into the building.

The other time—the only other time—she had visited Eliseo Daisani’s penthouse home had been an impetuous 4:00 a.m. arrival on the rooftop a few weeks earlier. Now, arms hugged around herself, Margrit stared hundreds of feet into the air at Daisani’s mirror-glassed apex apartment, wishing she could enter the way she had then.

Wished it for a host of reasons, not the least of which was that Alban had carried her in his arms then, ignoring human convention and soaring across the sky in his haste to make certain of Margrit’s safety. Malik had teased Alban with the threat to move against her during the day, when Alban was helpless to protect her.

Alban had turned to Daisani for help. That in itself might be reason enough for Margrit to do the same now, but standing outside his building in the small hours of the morning, she doubted herself.

Not so small anymore. Margrit shook herself. It was nearly seven, and Daisani would be on his way to work. Alban and Biali had to be rescued before she went to work; before Hank decided to take a sledgehammer to the statues on his rooftop. Daisani might not be a good choice, but he was the only one she had. Janx, even if she could get to him, no longer had the resources necessary to rescue a pair of wayward gargoyles.

She remembered too clearly that the first time she’d met Eliseo Daisani, he’d had two sealskins pinned to his office wall. One had been adult-sized, the other pup-sized. She’d thought then that he was a ruthless hunter, willing to take mother and child. It had proven that the furs were selkie skins, their presence in his office trapping a young woman and her daughter in their human forms. That he’d given them to Margrit as part of a bargain did nothing to reassure her: the fact that he’d had them at all said he was more than happy to take advantage of any powerful hand he might have over another. Turning Alban—and to a lesser degree, Biali—over to him while they were vulnerable was a last resort, something to be avoided if at all possible.

Margrit frowned toward the rooftop, knowing she was stalling, but not quite able to push herself forward yet. She wanted another answer to the problem at hand, but her heartbeats counted out passing moments in which Alban’s danger grew.

She wasn’t certain which held her back: a reluctance to owe one of the Old Races yet another favor, or Eliseo Daisani’s endless distressing failure to fit into any of the legends she knew. The other races were easier to deal with: lesser known, they also fell into old mythologies more readily, with the djinn ability to dissipate or the thin blue smoke that always followed Janx fitting what they really were.

But it was the gargoyles who were bound to night, not vampires. Daisani had been standing in an office full of sunlight the first time she met him, all swarthy smiles and a charisma that made his middling looks handsome. His teeth were unnervingly flat, no hint of too-long canines or a mouthful of razor-sharp ivory weapons. The dragon had pointy teeth, but the vampire, no. Neither garlic nor silver crosses held him off, nor did he require an invitation to pass a threshold. Alban had pointed out, prosaically, that Daisani would certainly die if someone thrust a wooden stake into his heart, but then again, so would anything else.

If she’d not seen the impossible speed Daisani could move with, if she’d not been given a gift of his blood to help her heal, she would never have believed he was anything other than what he appeared: a slight man with a great deal of personal wealth and business acumen. That, more than anything, made her not want to bargain with him.

Margrit tightened her hug, then let herself go forcefully, driving herself forward with the motion. As if she’d summoned him with the action, a security guard approached her. “Sorry, miss, but there’s no loitering here. You’ll have to move along.”

Genuine astonishment rose up as laughter. “Are you serious? This is a sightseeing stop. ‘Oh, yeah, that’s where Eliseo Daisani lives. He’s supposed to be worth forty billion now, you know?’ How do you get tourists to stop loitering?”

The guard gave her a tight smile and gestured her away. “Like this.”

Margrit held her ground as the guard stepped into her personal space. “Eliseo’s my boss. I need to see him.” She tried sidestepping the guard and found herself caught in a dance with him.

Visibly exasperated, he stepped back, language turning formal, as though he repeated a well-rehearsed line. “I’m sure if Mr. Daisani is your employer, you’ll find a more appropriate opportunity to speak with him.”

It struck Margrit that using Daisani’s first name—though she’d been invited to—probably put her in league with starstruck stalkers, not a properly subordinate employee. She grimaced, then stepped back with her hands lifted in acquiescence. The guard stood his ground until she’d headed well down the block, only returning to his rounds after Margrit disappeared around a corner and peeked back. She counted to thirty, then, grateful he hadn’t waited to see if she’d return, put on a burst of speed and bolted back to face the doorman.

“Wait,” she said as he reached for his radio. “I know I sound like a stalker, and I don’t have an appointment, but my name is Margrit Knight. I’m Mr. Daisani’s new personal assistant, and this really is an emergency. Could you please ring up to his apartment and at least tell him I’m here?”

“Miss,” the doorman said more patiently than the guard had, “it’s a quarter to seven in the morning. Even if—”

“Is it that late?” Margrit shot a look toward the horizon, cursing her lack of cell phone and therefore lack of timepiece. “Never mind. I’ll try to catch him at the office.”

“That won’t be necessary, Miss Knight.” Eliseo Daisani opened one of the lobby’s glass doors himself, putting a stricken look on the doorman’s face. “You may join me in the Town Car, if you wish.” He gestured to the street, then fastidiously brushed a speck of lint off his overcoat. The coat, like everything Margrit had seen Daisani in, looked unbelievably expensive, the wool appearing so soft she had to stop herself from reaching out to touch it. Its cut added to his height; Daisani was taller than Margrit, but only just.

She shook off her fascination with his coat and glanced toward the car. “Does it have privacy glass?”

Daisani’s eyebrows, then his voice, rose. “Edward, could you have the limousine brought around, please?” The driver, who’d stood at attention beside the car, actually clicked his heels together in response before climbing in and driving away. Daisani smiled, then turned to the still-stricken doorman. “Miss Knight is to be admitted at any time she desires. Don’t look so pale, Diego. I hadn’t left instructions. You weren’t to know. Margrit, will you require a ride home? I trust you’re not going to work in that attire.”

“A ride home would be great.” Margrit thinned her lips, staring between Daisani and the street. “I think. I don’t know if I’m going to work.”

“For reasons pertaining to your arrival here this morning, I trust.” Daisani nodded as a limousine pulled up, a different driver leaping out to hold the door. Bemused, Margrit preceded Daisani into the car, waiting until the doors and glass partition were closed before slumping in the leather seats. Daisani opened a miniature refrigerator and withdrew a bottle of water, eyebrows lifted in question.

“Yes, please.” Margrit sat up to accept and Daisani deftly poured two crystal glasses full, handing one to her and keeping the other for himself. The car pulled into traffic with a soft jolt of acceleration, then slowed again immediately. “Good thing we’re not in a hurry. It’d be faster to walk.”

“One of the tribulations of city living. Now, tell me what brings you to my doorstep so early in the morning, Margrit.”

“I have a problem, and—”

Daisani chortled, then waved off her look of surprise. “Forgive me. It’s just that it was only a few weeks ago I said something very similar to you.”

“You said I had a prob—” Margrit broke off again, recognizing his point, and Daisani’s smile broadened.

“And you assured me it was I who had a problem, not you.”

Margrit muttered, “A lot’s changed since then,” earning another delighted chuckle. She glowered out the tinted window, trying once more to think of someone else with the necessary resources to rescue two day-frozen gargoyles, and came up, again, with no other solution. “I need help,” she said to the windows, then transferred her gaze back to Daisani. “But I’m reluctant to tell you why until I’ve already established I’ll maintain control over the situation.”

“As opposed to?”

“You deciding you can get mileage out of it and using it to your own advantage.”

Daisani’s eyes half lidded in curiosity. “Suggesting it’s a scenario from which I could benefit.”

“Maybe. Probably,” Margrit amended. “On the other hand, if it’s not dealt with immediately, it’s got the potential to be very bad for all of you. It behooves you to give me control.”

“And in exchange you will give me what, Margrit? Your employment with me begins Monday, so that’s no longer an enticement you can bargain with. I doubt very much you intend to offer up the delectable Miss Dugan—Ah.” The last sound was one of smug laughter as Margrit’s heartbeat accelerated. She clamped down on the reaction, doing her best to inhale both deeply and discreetly. Daisani had admired Margrit’s housemate too many times already, and his choice of words reminded her that the man she sat with was not a man at all. Humanity lay as a veneer over a true form she’d never seen. In the one rendering she’d seen, vampires had been depicted as manlike, but Margrit doubted Daisani’s other form was so familiar and reassuring.

“My friends aren’t any part of this, Eliseo.” The coldness in her own voice surprised her, its strength sounding as though she might somehow be able to prevent Daisani from dragging Cameron into the world Margrit had become a part of. Daisani’s mouth quirked, recognition of and interest in Margrit’s implacability. “I’ll leave it an open-ended favor if I have to, but no way are you involving Cameron or Cole in any of this.”

“Who is responsible for Malik al-Massri’s death?” Daisani spoke so abruptly Margrit sat back, fingers tightening around her water glass. “I swore an oath, Margrit, that I would exact vengeance against anyone foolish enough to cross me when I had extended my protection to him, and I will fulfill that oath. Don’t deny you were there. I have enough friends in the police department to know better. Tell me, Margrit. Tell me, and you will have your favor.”

The water she’d drunk turned to an icy leaden weight inside her belly. Sick with adrenaline, Margrit set her glass aside, fitting it carefully into a cup holder before folding her hands and leaning toward Daisani. Too aware she wrote her own fate with the words, she said, “Help me rescue the gargoyles, and when they’re safe, I’ll tell you what you want to know.”

THREE

“YOU NEVER FAIL to astound.”

Margrit was uncertain if Daisani meant humans in general or herself in particular, though as he raised a palm and added, “I know. You’re a lawyer. Everything is a negotiation,” she suspected the comment was meant for her alone. “Rescue the gargoyles. Margrit, do you deliberately set up dramatic deliveries or is it just fortune and happenstance? Never mind. I don’t want to know. You have my undivided attention, Miss Knight. Do go on.”

“Do we have a deal?”

“Oh, we most certainly do, as I wouldn’t miss the rest of this for the world. One rescue for one piece of priceless information.” Daisani finished his water and steepled his fingers in front of his mouth as Margrit explained the fight that had led to Alban and Biali’s capture by sunlight. “I do think you’re getting the better end of this deal, Margrit.”

“Which has happened exactly never in me dealing with the Old Races, so how about you let me have this one? Besides, your honor’s at stake here, right?”

“It is, but perhaps Alban would be so grateful for the rescue he would offer me what I want to know in exchange.”

“No.” Margrit’s certainty earned another questioning look from the vampire. “You can’t risk Alban being exposed. Being killed. His memories would go to the gestalt, and you don’t want that to happen. I’ve watched enough of your interactions to know he’s keeping secrets for you and Janx both.”

She knew considerably more than that, but Alban had cautioned her more than once about letting either vampire or dragon know she could sometimes access the remarkable gargoyle memories. Psychically shared, the repository held aeons of history, not just of the gargoyles themselves, but of all the Old Races, ensuring none of them would be forgotten to time. Alban Korund had set himself apart from his brethren to protect the secrets of two men not of his race, refusing to share any memories at all in order to protect one that might have changed their world.

Centuries earlier Janx and Daisani had loved the same human woman, and she had—perhaps—borne a child to one of them. Only literally within the last few weeks had the Old Races lifted their exiling law against those who bred with humans. Margrit was confident that neither Daisani nor Janx was sure their transgressions, hundreds of years in the past, would be given carte blanche now. Even if they were, she was equally sure they wouldn’t want their old secrets made public unless they controlled how and when. Alban’s premature death would simply send his memories back into the gestalt via the nearest gargoyle, and then everything dragon and vampire had worked to hide would be exposed to all the Old Races.

“You’ve learned to drive a hard bargain, Miss Knight.” Admiration and warning weighed Daisani’s words in equal part. Margrit allowed herself a nod, the same kind of understated motion she was coming to expect from the Old Races. A smile flickered across Daisani’s face as he recognized their influence on her. “How do you propose we retrieve our wayward friends?”

“I was thinking helicopters, speaking of dramatic.” Margrit pulled a face, then shrugged. “They won’t fit in elevators. The only other thing I can really think of is just getting security in there so nobody’s around at sunset. Anything else is going to draw a lot of attention to you.”

“To me.” Amusement lit Daisani’s voice, reminding Margrit of Janx. “Are you so concerned about my profile?”

“Only insofar as it seems probable that Eliseo Daisani taking an interest in a couple of statues on a rooftop would make the media interested in them, too. I’m going to kill them,” Margrit added under her breath.

“The media?” Daisani asked, polite with humor.

Margrit gave him a sour look. “Alban and Biali. Why they had to have a fight in human territory …”

“There is no other choice.” Daisani traced a fingertip over his glass’s edge, humor fled. “We’re obliged to live in your world, Margrit, either on its edges or in its midst. Our other choice is to retreat, and retreat and retreat again, until we’re mere animals hiding in caves and snapping at our brothers. It’s no way to live, and so if we’re to fight, to breathe, to sup, to speak, it must be done in your world. You may have stemmed the tide of our destruction, but I fear there will still come a day when we cannot hide, and so must die.”

“You fear,” Margrit echoed softly. “I didn’t know you could.”

“All thinking things fear. Sentience, perhaps, is facing that fear and conquering it rather than succumbing. A tiger will drown in a tar pit, but a man who can clear his thoughts may survive.” Silence held for a few long moments, disturbed but not destroyed by the sounds of traffic around them. Then Daisani shook it off, bringing his hands together with a clap. “If common sense prevails over dramatics, then security is the best option. Either way, I’m afraid my name may come into it. Your building manager will want an explanation for security.”

“Do you have a better idea?”

“Sadly, no. Vampires are quick, not strong, and even Janx would be hard-pressed to rescue a sleeping gargoyle.” Daisani’s expression brightened and Margrit found herself grinning, too, at the idea of Janx’s sinuous dragon form struggling to haul a gargoyle through the sky.

“Good thing humans don’t look up,” she said to the idea. “Alban says we don’t,” she added to Daisani’s quirked eyebrow. “Still, a news chopper would probably notice your company helicopters flying in a gargoyle statue.”

A smile leapt across Daisani’s face. “What if we give them something else to look at?”

“This afternoon, from atop the Statue of Liberty, legendary businessman Eliseo Daisani has called an impromptu press conference to announce the latest development from Daisani Incorporated’s charitable arm. We have news cameras in the air and a reporter on the ground—or as close as it gets when it comes to the highflying philanthropist. Sandra, to you—”

Margrit, smiling, thumbed the radio function on her MP3 player off and dropped it into her purse. She’d spent the morning at her soon-to-be former office, filing papers and reviewing arguments with coworkers who were taking over her caseload. After four years at Legal Aid, being down to her last three days was in equal parts alarming and exciting. Her coworkers were merrily marking off the hours with a notepad affixed to the side of her cubicle. Every hour someone stopped by and ripped a page off. When Daisani called at a quarter to twelve, bright red numbers on the notepad told her she had twenty-one hours left in which to wrap up a career she’d imagined, not that long ago, would see her through another decade.

She tore off the twenty-one herself as she left the building. By noon Daisani had captured every news center in the city with his ostentatious announcement. “The Liberty Education Fund Trust,” he’d said deprecatingly, first that morning to her in the car, and then again to the newscasters. “So I can show people how far to the LEFT we’re leaning here at Daisani Incorporated.” It would be a hundred-million-dollar grant pool, available to any student seeking higher education whose family income was less than fifty thousand dollars a year.

The project, he’d assured Margrit, had been under development for months, and while it wasn’t yet ready to roll out, it was close enough to finished that an announcement could be staged. The program’s title combined with his own power got him hasty permission to make the presentation at the Statue of Liberty, and just as surely, that combination drew the attention of all the newshounds in the city.

Margrit, cynically, thought that the timing was convenient for the tax year, too, with April fifteenth on the horizon. But given that Daisani was helping her with an otherwise impossible situation—and, she reminded herself with a shiver, the price that would be exacted—she wasn’t in a position to cast stones. Suddenly grim, she hurried into Hank’s building, knocked on the manager’s door and opened it in response to his grunted reply. “Hey. Good news, I got some guys who’ll help me move the statues, and … What’s wrong?”

Hank’s glower was darker than it had been earlier. “Ran into Rosita awhile ago.”

Blank confusion hissed through Margrit’s mind, the morning’s details rushing over her in a jumble as she tried to sort out who Rosita was, and why it mattered that the building manager had seen her. Then dismay knotted her hand around the doorknob. Long, telltale seconds passed before Margrit mumbled, “You said I was with Rosita, not me.”

“Well, I’ve been all over the building now and nobody had a friend named Maggie staying over from out of town last night. And funny, nobody mentioned you knocking on their doors this morning, either.” Hank clambered to his feet, expression grim. “So you wanna start again with the whole story? Who are you, and how’d you get those things up there?”

“Are they still there?” Even whispered, Margrit’s question broke and cracked. “You haven’t destroyed them, have you?”

“Not yet.” Dangerous emphasis lay on the second word, but Margrit sagged with relief. “But if I don’t get an explanation, I’m calling the cops and then smashing those things to pieces.”

“Don’t do that.” Margrit cleared her throat, trying to strengthen her voice. “I’ve got a collector on the way to remove them. Are you the building owner?”

“Am I—what? No, I manage the prop—”

“Too bad. I’ve been authorized by the collector to offer a substantial cash payment for the statues. Perhaps you’d like to give him a call.” Margrit lifted her eyebrows and nodded toward the phone, trying to give the impression she was happy to wait all day. Hank couldn’t feel the coldness of her hands, or, she hoped, see the way they shook. There was nothing illegal about offering the man a bribe to look the other way, not when the gargoyles on the rooftop were their own possessions, not stolen or lost property. Her erratic heartbeat, though, didn’t believe her, and it took an effort to keep her expression steady as she watched the building manager.

He turned gray, then flushed with interest. “How substantial? I’m, uh, I make the decisions regarding the property, so you can just tell me….”

“Ah. I’m prepared to make an offer of twenty thousand dollars. Cash.” Margrit slipped her purse off her shoulder and withdrew an envelope, holding it with her fingertips.

Hank turned redder, flesh around his collar seeming to swell. “For a couple damned statues?”

“The collector has some familiarity with works of this size and feels it’s a fair offer.” Like Hank, Margrit had turned pale when Daisani casually unwrapped a billfold and began peeling off hundred-dollar bills. “Cash,” he’d said as he handed over considerably more than the amount Margrit had just offered, “tends to distract attention from most offenses. If your building manager proves at all recalcitrant, don’t bother negotiating.” Then he’d dropped a wink, adding, “Even if that is your specialty.”

“Sure,” Hank said hoarsely. “My boss’d be happy to let your guy take ‘em.”

“Great. Should we call him to—”

“No! No, that’s okay, I’ll, uh, I’ll take care of it all, don’t worry. How, uh, how’re you getting them out of here?”

“Well, if you’re sure the arrangements will be to your boss’s satisfaction, I can have them picked up in …” Margrit turned her wrist up, looking at the watch she hadn’t been wearing earlier. “In about five minutes. I’ll need to go up to the roof, of course.” She tilted the envelope toward Hank.

His hands twitched. “Sure, yeah, whatever you need.” Margrit set the envelope on his desk under his avaricious gaze, and she heard paper rustle as she turned away. “Hey. Maggie. How did you get up on the roof?”

Margrit looked back with a sigh. “I flew.”

She took the elevator to the roof, not wanting to lose time to twenty flights of stairs. Even so, she had too much chance to consider the ethics of what she’d just done. Margrit nudged her purse open, looking at the second envelope she’d put the rest of the money in. Daisani’d handed over nearly seventy thousand dollars without blinking, and she’d accepted it as readily. There was nothing illegal to the transaction, but it made her spine itch between the shoulder blades, as if she’d begun the slow process of setting herself up for a fall.

And if that was the price for Alban’s safety, then she would spread her arms and plummet. It was an axiom that everyone could be bought, though her naive and self-righteous self would have said only a few months earlier that she couldn’t. The mighty had fallen, and for all the nightmares and regrets, Margrit wouldn’t change that if she could. There was too much heretofore unknown magic in the world, and learning of its existence was worth very nearly any cost. The moral high ground she’d stood on had far less appeal than living in Alban’s society, outside and above the rules of the life she’d known.

That was the road to hell, jaggedly paved with good intentions. Margrit pressed her lips together, wondering if Vanessa Gray had found herself traveling a similar path a hundred and thirty years earlier. She would have to ask Janx; Daisani would never answer. The doors chimed open and Margrit scurried to the roof, searching her purse for her cell phone so she could call the helicopter pilots and supervise the pickup.

She pushed the rooftop door open, drawing breath to give the go-order, but silence caught her by the throat and held her.

The gargoyles were gone.

FOUR

MARGRIT SHOT A compulsive look toward the west, as if the sun might have gone down and brought night to the city hours early. It hadn’t, of course: it was white and hard in the sky above. She looked back to the empty rooftop, aware that a double take wouldn’t prove that she’d somehow missed two massive, stony gargoyles frozen in battle, but simply unable to comprehend what she saw.

Her body, less numbed than her mind, dialed the number Daisani’d given her and lifted the phone to her ear. Silence preceded a burst of static, and then a connection went through, a man’s cheerful voice saying, “This is Bird One. We’re coming in from the south. Turn around and you’ll be able to see us.”

Margrit said, “Abort,” mechanically, intellect still not caught up with what she saw. “The statues we were going to collect have already been removed. No sense in drawing attention here. Thanks for your time, guys.”

“Bird One aborting,” the pilot said just as cheerfully. “Maybe another time, ma’am.” Margrit folded the phone closed, straining to hear the helicopters as they retreated, uncertain if she did, or if it was simply the roaring of her blood and too-hard beat of her heart. She wanted to burst into speed, as though a mad dash across the rooftop would somehow retrieve a pair of missing gargoyles.

Hank had been too angry at her reappearance and not guilty enough at taking the money to be responsible, she thought. She would confront him, but gut instinct said the building manager hadn’t broken the gargoyles to pieces and dumped them. Gut instinct and a lack of dust or rubble, though those could be taken care of with a broom. But unless Daisani had double-crossed her, Margrit had no other explanation. Color rushed to her cheeks at the idea, her vision tunneling and expanding again. There was nothing she could do to the vampire if he had, but there were things he wanted she could withdraw from the table. It was better than nothing.

The rooftop door’s knob nudged her hip, making her realize she’d backed up without noticing. Margrit folded a hand around it, still staring blankly at the empty roof, then shook herself with deliberate violence and turned away. Whatever answers there were, they wouldn’t be found by helpless inaction.

The building manager blanched so white Margrit had every confidence he hadn’t been responsible for the gargoyles’ disappearance. She left him with his wad of cash and found a subway station, unwilling to wait on a taxi making its tedious way through traffic.

Her slow burn had lit to genuine, body-flushing anger by the time she reached Daisani’s building. She didn’t bother checking in, using her key card for the elevators with impunity, and stalked through what had been Vanessa Gray’s reception area to throw Daisani’s private office’s door open.

He wasn’t there. A dry crack of laughter hurt Margrit’s throat as indignation deflated under the heavy weight of reality. Once in a while the world allowed itself to be set up for dramatic confrontations, but arbitrary disappointment was the more likely scenario at any given moment. She paused at Daisani’s oversized desk to leave the envelope of cash on it, then stepped forward to lean against the plate-glass windows that overlooked the city. It looked serene from so far above, no hint that the lives taking place within it were chaotic and unpredictable.

The elevator in the front office dinged. Margrit straightened from the window, turning to find Daisani, looking as disheveled as she’d ever seen him, at her side. Genuine concern wrinkled his forehead, and he offered a comforting hand. “I came as quickly as I could.”

Margrit’s eyebrows arched and a faint crease of humor warped the vampire’s mouth. “I came as quickly as humanly possible,” he amended. “The pilot informed me they’d already been picked up. Who—?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t know what else to tell him. They were just gone. I don’t think it was the building manager.” Margrit thinned her lips, eyeing Daisani. He caught the weight of accusation and rolled back onto his heels, giving her a brief, unexpected height advantage.

“And now you suspect me. You promised me something I wanted in return for their safe rescue, Margrit. I rarely renege on scenarios which provide me with things I desire.”

“You know that bargain’s moot now. You didn’t rescue them. I’m not spilling secrets for noble attempts.”

Pleasantry trickled out of Daisani’s expression, leaving his dark eyes full of warning. “That’s a dangerous choice. Are you sure you want to make it?”

“This is twice you’ve failed to come through, Eliseo. Hell, right now I’m wondering why exactly it is I should come work for you. I promised I would in exchange for you keeping Malik alive. He’s dead.” An image of flames burned Margrit’s eyes and she blinked it away as Daisani’s countenance darkened. Sharp awareness that she should be afraid brightened Margrit’s focus, but no alarm triggered. Whether the vampire’s too-fast, alien nature had ceased to be a source of alarm, or if fatalism simply outweighed nerves, seemed irrelevant.

“You’ve become dangerously bold, Miss Knight.”

“I always have been. I’ve just gotten to where I’m not afraid of laying it out with your people, as well as mine. Oh, don’t give me that look.” She snapped away Daisani’s expression of faint dismay. “I wouldn’t be any use to you if I was terrified. Vanessa couldn’t have been.”

“Vanessa and I,” Daisani said after a measured moment, “had a very different relationship than you and I do. And terror has its uses.”

“So does boldness. If you didn’t take them, who did?” Margrit put the argument aside firmly, confident she’d won.

Daisani gave her a long, hard look, speaking volumes about the game she played before he, too, set it aside. “Even if he knew about their predicament, Janx no longer has the resources to move two gargoyles. Besides, he hasn’t been seen in days. It’s possible he’s left the city.”

“Do you really think he’d give up his territory that easily?” The House of Cards had burned, selkies and djinn moving into the vacuum left by its fall. Janx had retreated underground to lick wounds both literal and figurative, but Margrit doubted he’d readily walk away from the criminal empire he’d created. “There’s still a lot of upheaval going on at the docks. Cops have been down there nonstop since the raid and they’re still not keeping all the violence in check. The opportunity to take it all back is there for a strong enough leader.”

“Ah, yes, the docks. Speaking of which, how’s your friend Detective Pulcella? I’ve seen him on the news several nights a week since the House was raided. He’s a good-looking young man, isn’t he?”

Margrit’s hands curled into fists. “Yes, he is. I haven’t really talked to him since the raid.” Tony Pulcella was a homicide detective, though the bust that had given prosecutors Janx’s financial books had put Tony on a fast track to promotion and a wider range of responsibilities. The clincher was Janx’s arrest, and he’d been working long hours toward that end, as evidenced by innumerable news-camera glimpses of him day and night. He was well outside his jurisdiction, but homicides linked to Janx cropped up all over the city, and Tony had long since been part of the team trying to bring the crimelord in. His determination to do so had helped tear apart his relationship with Margrit, and ironically, she was now far more deeply entangled in Janx’s world than her ex-lover could ever have imagined.

“Quite the proper hero,” Daisani went on blithely. “A pity for him that he can’t see what’s really going on.”

“How could he?” Bitterness laced Margrit’s question. “You’d kill him if he found out about you.”

Newscasts didn’t show the way the Old Races moved, too fluid and graceful, marking them as creatures unfettered by the bounds that held humanity in check. Margrit had learned, though, to look for other signs on the news: djinn with their jewel-bright gazes, selkies with their tremendously dark eyes, all pupil and blackness. The two races had forged a treaty to support each other, making natural enemies into one tremendous force, their numbers vastly greater than any others of the Old Races. The selkies had long since bred with humans to replenish their failing numbers, breaking one of the few dearly held laws that all five remaining races had in common. The insular, desert-bound djinn had supported the selkie petition to return to full standing amongst the Old Races in exchange for selkie help in taking over and running Janx’s underworld empire.

Neither party appeared to be happy with the arrangement now that it was met. Clashes on the street had the feel and damage of gang warfare, leaving police bewildered when weapons were found abandoned at the water’s edge, blood on the ground and no sign of embattled people in sight. One journalist was dead, his camera destroyed. Margrit had little doubt he’d captured a selkie or djinn transforming, and paid the price for it.

Janx had run the House of Cards with an iron hand, unapologetic in his activities but keeping a sort of peace with his tactics. That was lost, leaving opportunistic humans with knowledge of how to control a troublesome empire to face two Old Races with ambition and a slippery pact just strong enough to unite them against outsiders. Even hyperbolic newscasters, always eager for a bad-news story, were becoming reluctant to dwell on the troubles at the docks and warehouses, as if ignoring them would make them disappear. But the city was suffering, and that was news, not sensationalized or dramatized. Goods were coming in and shipping out more slowly than they should; dockworkers were striking for fear of their lives and police were under verbal attack for failing to protect citizens and materials alike. That they were up against an enemy they literally couldn’t comprehend didn’t matter.

It was the worst scenario Margrit could have imagined springing from her attempt to make the Old Races reconsider their archaic laws and move into humanity’s modern world, the consequence of her arrogant belief that her way was the right one. “I wonder if talking to them would help,” she said aloud, thoughts too far from the conversation she’d been holding to follow through on it.

Daisani canted his head in curiosity. “The police?”

“The selkies. The djinn. Somebody’s got to do something to stop their fight, and Tony’s not going to be able to do it. I set this ball rolling. Maybe I can—”

“Negotiate a cease-fire?”

“Yeah, something like that.” Margrit lifted a hand to her hair, ready to pull her ponytail out so she could scruff her fingers through it, and discovered she wore corkscrew curls in a tightly twisted knot. Stymied, she dropped her hand again and caught Daisani’s amused smirk. “I know,” she muttered. “It’s a tell. Remind me not to play poker with you.”

“I very much doubt you’d allow yourself such obvious divulgences in a poker game, Margrit. No more than you would in court. We’re all allowed our little slipups in day-to-day life, however.”

“Even you?”

Daisani’s eyes lidded. “Rarely, but once in a while even I have a lapse in judgment.”

“Yeah.” Amusement quirked Margrit’s mouth. “I’ll tell my mother hello next time I talk to her.”

Surprise shot over Daisani’s face, ending in a rare laugh. “Oh, well done. You see? I do have my tells. Do say hello, and I gather from that remark you’re dismissing yourself. What will you do?”

Margrit spread her hands. “Find the gargoyles.”

Her cell phone rang so promptly on Margrit’s departure that she turned back to eye Daisani’s building suspiciously, as though the vampire might have waited until she was out the door to politely ask just how she expected to accomplish that. The building gave no sign of whether it was Daisani calling, and the phone, when she pulled it free of her purse, came up with a Legal Aid number. Wrist twisted up to check the time, she imagined another hour had been stripped from the notepad by her desk as she answered.

“Margrit, this is Sam. The opening statements for the Davison trial have been moved up to this afternoon.”

“They were supposed to be Friday!” Margrit overrode the receptionist’s apologies with her own. “Sorry, it’s not your fault they moved it. Look, Jim’s prepared to take the case on alone. I’ll come in as cocounselor, but this is his as of Monday anyway.” She glanced at her watch again, promising she’d be at the courthouse as soon as possible, then closed the phone with a snap and shot a second glare at the Daisani building.

The single best reason to work for the business mogul was that when Old Races complications cropped up in her life, she could at least explain the situation without causing impossible difficulties. Biting back a curse, she hailed a taxi and returned, with a growing degree of reluctance, to what she still thought of as her real life.

FIVE

SUNSET CAME WITH a blinding burst of pain.

Alban flung himself away from agony, a howl ripping from his throat. He heard stone tear, deep wrenching sound, and a woman’s startled curse, but neither stopped him from snarling and savaging his way forward. Taloned feet dug into the floor, muscle straining with fury. Iron squealed, tearing without breaking. He howled again, reverberating sound so deep plaster crumbled. There was no escape: iron bound him hand and throat and ankle, making walls distant and red with pain. He couldn’t move his hands more than a few inches from his head, chains limiting his range of motion.

Panicked instinct drove him to try transforming, anything to escape the bone-deep fire of iron. Fresh pain spasmed through him, denying him the human form he’d become so accustomed to wearing. Tenterhooks curled into his muscles, ripping with an eye to deliberate, debilitating anguish. Every time, it shattered through him, and yet he could not stop trying.

Somehow he had never imagined it would hurt so badly, not even with Hajnal’s memories of captivity fresh in his mind. Perhaps he’d mistaken the pain of iron bound to flesh and stone for the pain of her injuries, or perhaps the passage of time had muted the outrage. It was possible that the filtering of so many minds experiencing the barbaric sting of slavery had, over the millennia, dulled its edge. If that was so, the gargoyles had lost something even more precious than Alban’s freedom. They were losing the history of their people, of all the Old Races, to the inexorable wear of time. It could be their diminishing numbers as their own range of experience became so limited that they couldn’t fully appreciate, and therefore fully recall, the passions and pains of history.

Three and a half centuries had passed since Alban had last joined in the overmind and shared his experiences with the rest of his people. It happened from time to time; a promise was made to remember, but not to make the memory open to all. They were made for finite periods, until some crux had passed.

Alban, friends with two men of other races, had made a promise to stand a lifetime alone to protect their secrets, and in the thirty and more decades since then he had never seriously considered breaking his word. His people called him the Breach, for selfishly holding back the memories of the last of his family, the Korund line, from the whole; he compounded it now with Hajnal’s family memories buried within him.

Now, bound in chains, his blood recoiling and sending shards of pain through him at each encounter with the metal, it seemed he had something worth breaking his promise for. He could feel the metal’s weight inside him, demanding obedience, and doubted he would be able to stand against any command Biali might give. That, too, was a warning his intellect spoke of: the distant recollection that gargoyles bound by iron could be made an army unable to refuse orders. It wasn’t a worry that had ever haunted him, but now Alban feared blunted memory did his people and all the Old Races no good. If agony shared could sear open the depths of history his people could recall, it might yet be worth betraying onetime friends.

And perhaps the secret he carried for them could alter the status quo the Old Races had lived with for so long. Perhaps that alternation could awaken the Old Races to the possibilities of the future, as a fresh introduction of pained captivity might awaken the gargoyles to their neglected histories.

For shame, Korund. Such brief captivity, leading so easily to thoughts of betrayal. Margrit would say a little forced perspective was good for him.

Margrit. She had been in danger.

Pain surged through him again, inadvertent attempt at transformation, as though wearing a human form might somehow free him from his bonds.

Humanoid. A gargoyle’s natural form was humanoid, unlike the other surviving Old Races. Dragons were sinuous reptiles; selkies, seals in their first-born form; the djinn barely held shape at all, their thoughts made of whirling winds and sand, and the vampires, well: no one saw a vampire’s natural form and lived to speak of it. But gargoyles walked on two legs, stood upright, saw with binocular vision, as much like a man as a member of the Old Races could be.

Gargoyles did not leap and snarl like a dog in chains.

Alban ground taloned toes into the stone floor and surged forward. Rattling chain scraped again, pulling him up short and choking his breath away. He roared fury, words lost to him.

“Sorry, love.”

A woman’s voice again, so unexpected it brought Alban up as short as the chains had, distracting him from pain and rage. Focus swam over him, the words giving him something other than himself to think about. “… Grace?”

“Ah, and so now he comes to his senses.” In the blur of his anger he hadn’t scented her, hadn’t seen her, though a whisper of memory now told him he’d heard her alarmed squeak as he’d awakened so violently. She stood across the room from him, one foot propped against the wall, her arms folded under her breasts. This was her territory, the tunnels beneath the city; she ran a halfway house for teens down here, and had for some months provided sanctuary for Alban himself. His mind was still too muddled to make sense of his awakening there, and she gave him no chance to ask questions. “Sorry for the accommodations, Stoneheart. Biali won’t release you, and I’ll not be risking you tearing down the walls in a fit of temper. I can unfasten the locks that hold you to the floor, but only if you’ll control yourself.”

Alban lowered his head, panting, and even to him, the minutes seemed long before he lifted his gaze again. “I am controlled.”

“Sure and you are,” Grace muttered. “Like a tempest in a teacup. All right, it’s only my own neck then, isn’t it?” She came forward with a key, crouching as Alban relaxed and let slack into his chains.

“I wouldn’t harm you, Grace.” He spoke the promise in measured tones, reminding himself of that truth as much as reassuring her. Grace opened the chains at his ankles, letting them drop to the floor. He came to his feet, hands fisted around the chain at his throat; he was entirely helpless like this, arms folded close to his chest. Eating would be awkward, but he could spare himself that humiliation: stone had no need for regular meals. “We’re in the tunnels. But Biali and I—”

“Were making fools of yourselves on the rooftops,” Grace supplied. “I couldn’t leave you there to fight it out at sunset, now, could I? What were you thinking, Alban?” she added irritably. “You’re bright enough to stay away from that one.”

“He’d taken Margrit. Where is he? Where is she?” Alarm spiked through Alban’s chest and pain rippled over him again as he tried, fruitlessly, to transform. Grace slapped his shoulder, still annoyed.

“Stop that. It looks horrible, as if all the snakes driven from Ireland have taken up under your skin and can’t get free. He is chained up in another sealed-off room, throwing more of a tantrum than you, and I’ve no idea where your lawyer friend is. Better off without you, I’d say,” Grace said sourly. “Not that either you or she will listen to the likes of me.”

Breathless confusion pounded through Alban, counterpart to the pain the chains brought. Speaking helped: being spoken to helped. Even Grace’s clear pique helped push away the bleak, mindless rage. “I do not understand.” He kept the words measured, trusting deliberation over the higher emotions that heated his blood. “How did we come here? What are you doing? What did Biali want?”

“Grace has her tricks, and a few friends to call on when she needs to. I’m trying to stop a fight before it schisms your people,” Grace added more acerbically. “As for what Biali wants, you tell me.”

Alban breathed, “Tricks,” incredulously, then, distracted from the thought, said, “Revenge,” the word heavy and grim and requiring no need of consideration. “Revenge for Ausra.”

Grace stepped back with an air of sudden understanding, speaking under her breath. “So it wasn’t Margrit who saved herself after all. And Biali found it out.” She paced away, then stopped, hands on her hips, chin tilted up, gaze distant on a wall. “Then I’ve done what’s best, haven’t I?”

“What have you done?”

Grace turned, all leonine curves in black leather. “I’ve sent for a gargoyle jury.”

The countdown calendar was at sixteen hours, failing to take into account the after-court work Margrit returned to the office to do. She waved goodbye as coworkers slipped out, and gave the calendar a rueful glance. If she was lucky it wasn’t off by more than three or four hours.

She was alone at sunset, bent over paperwork that gave her a cramp between her shoulder blades, but it redoubled, then racked her with breath-taking shocks of pain. Semifamiliar images crashed through her mind in spasms, too brief and disconcerting for her to hold. They had the feeling of being seen through someone else’s eyes, as though she once more rode memory with Alban. Minutes after the sky went dark with twilight, concrete chambers finally came into resolution, body-wracking shudders fading away. Fingers clawed against her desk, breathing short with astonishment and dismay, Margrit struggled to recognize the rooms. Finally, sweat beaded on her forehead and hands trembling from holding her desk too hard, her own memory clarified where she’d seen them before.

Belowground, in Grace O’Malley’s complex network of tunnels under the city.

There were innumerable ways to enter those tunnels, but only one Margrit felt certain of. She stopped long enough to change shoes, then, still wearing the skirt suit she’d worn to court, left the office at a run.

Minutes later she scrambled over the fence to Trinity Church’s graveyard, all too aware that she had no good explanation if she was caught. She dropped to the ground easily, suddenly surrounded by headstones, some worn beyond readability, others as sharply etched as if they were new. Wilted flowers lay on a handful of graves, though an April breeze caught lingering scent from one bunch and carried it to her. The church itself was a dozen yards away, glowing under nighttime lights, lonely without its tourists and parishioners.

Paths brought her to an inset corner of the church near its front entrance. She glanced over her shoulder, nervous action, and mumbled an apology to the dead as she stepped over a grave and placed her palm against one of the church’s pinkish brown stones, pressing hard.

The scrape of stone against stone sounded hideously loud in the churchyard’s silence. Margrit held her breath, as if that would somehow quiet the opening door, and for a moment heard the city as it actually was, rather than simply the background noise of day-to-day life. Engines rumbled in the near distance, ubiquitous horns honking. The wind carried a voice or two, but most of the sound came from mechanical things.

The door ceased its scrape and she stepped inside it, looking guiltily around the churchyard again. If she’d designed a hidden door, she would have put it at the back of the church, not the front. She saw no one, though, and pressed the door closed again as she used her phone for a flashlight.

The light bounced off pale walls. Margrit blinked at the steep stairs that led downward, never having seen them so clearly before. The walls had been scrubbed, an inch of soot washed away, and the stairway was much brighter for it. She trotted down, curious to see what other changes had been made.

The room at the foot of the stairs was almost as she remembered it, though cleaner. Walls reaching twenty feet on a side had been washed free of their sooty blanket, and the cot settled in one corner no longer touched those walls. A small wooden table was also pulled a few inches away from the wall, its single chair pushed beneath it. Bookcases lined the walls, candles and candleholders set on them. Electric lights had been added, wires looping above the shelves. There was nowhere to cook in the room, nor any obvious ventilation. Only Alban’s books were missing, safe in his chamber in Grace’s domain.

She switched on the lights and tucked her phone back in her pocket before moving Alban’s cot to reveal the flagstone they’d escaped through. It was two feet on a side. Margrit sat down on the cot, dismay rising anew. She’d forgotten its size, and the incredible strength necessary to move it. Even in his human form, Alban was disproportionately strong. Margrit could barely conceive of his gargoyle-form’s strength limitations. Certainly her own weight was inconsequential to him. Half-welcome recollection flooded and warmed her, the memory of his hands, strong and gentle, holding her, guiding her, seeking out her pleasure. In flight, in love, that strength had been sensual.