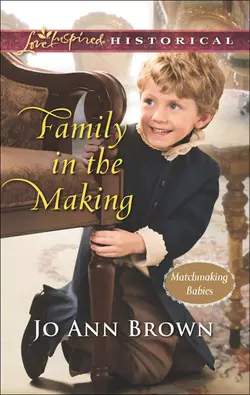

Family In The Making

Jo Ann Brown

Daddy LessonsArthur, Lord Trelawney, is an expert at carrying coded messages for the government—and a complete amateur in caring for children. Before courting a widowed acquaintance with two babies, he decides to practice with the rescued orphans sheltering at his family estate. A practical idea…until he meets their lovely nurse.Maris Oliver is drawn to the principled, handsome nobleman, even if he's expected to woo another woman. Both have secrets that threaten their safety and their fragile trust. But if Maris's sweet charges have their way, Arthur won't need to venture beyond his own front door to find a woman he'll risk all to protect and love.Matchmaking Babies: Seeking forever families and speeding up the course of true love

Daddy Lessonse

Arthur, Lord Trelawney, is an expert at carrying coded messages for the government—and a complete amateur in caring for children. Before courting a widowed acquaintance with two babies, he decides to practice with the rescued orphans sheltering at his family estate. A practical idea…until he meets their lovely nurse.

Maris Oliver is drawn to the principled, handsome nobleman, even if he’s expected to woo another woman. Both have secrets that threaten their safety and their fragile trust. But if Maris’s sweet charges have their way, Arthur won’t need to venture beyond his own front door to find a woman he’ll risk all to protect and love.

“Must you always obey the canons of Society?”

“I don’t understand.”

“You are always polite to the point it can become aggravating.”

Her eyes widened. “Would you have me be otherwise?”

“At times, yes! The ton did not collapse when the children began to address me as Arthur. It feels absurd when you continue to call me ‘my lord.’ Why don’t you do as they do?”

“They are children. They are excused from making such a faux pas.”

“How can it be a faux pas if I ask you to address me so?”

Maris had no quick answer to give him. To let his name form on her lips… If other servants or members of his family heard, would they be as accepting as they were with the children?

As if she had aired her thoughts aloud, he said, “It would be only when we’re with the children or when we are having a conversation like tonight. Could we at least try tonight?”

“Yes.”

He raised a single brow.

“Yes, Arthur,” she said with a faint smile. How sweet his name tasted on her lips!

JO ANN BROWN has always loved stories with happy-ever-after endings. A former military officer, she is thrilled to have the chance to write stories about people falling in love. She is also a photographer, and she travels with her husband of more than thirty years to places where she can snap pictures. They live in Nevada with three children and a spoiled cat. Drop her a note at joannbrownbooks.com (http://www.joannbrownbooks.com).

Family in the Making

Jo Ann Brown

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For there is no man that doeth any thing in secret, and he himself seeketh to be known openly.

If thou do these things, show thyself to the world.

—John 7:4

For my dear son Peter and his beautiful bride, Meghan

You are beginning your lives together as a family

May you always be as filled with joy and love as you are on the day you say “I do.”

Contents

Cover (#ubca92824-f71a-53a9-8c2f-357278ff5c38)

Back Cover Text (#u4c2de354-f4aa-5bd0-bbb5-f2e6c04e9be8)

Introduction (#u5b46c3ea-4d6f-557b-acf9-d51489cd4e92)

About the Author (#ucdb9fd18-1e7b-522a-8433-d1fc8861f082)

Title Page (#u36b0e17e-6cb5-54b2-9fb9-dd675e401b3c)

Bible Verse (#u3b8ad0d5-c73f-5820-8258-9e0056f30173)

Dedication (#u44f18aa0-8dfe-5211-97d8-a5e435c1f659)

Chapter One (#ueaa5c4e2-d9c5-53cd-8f40-03b31d00e0ac)

Chapter Two (#u9aa918d6-0591-5bc3-979e-37206a08385a)

Chapter Three (#u5250a61a-9ea2-5bbc-af48-5bfb724087c9)

Chapter Four (#u65bfaa19-4598-50c9-8c29-f0276f4bbddb)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_72649b8a-4c1f-55ec-bec2-93f662ce4848)

Porthlowen, Cornwall October 1812

Another inch. One little inch, and she would have it.

Maris Oliver stood on tiptoe on the chair and stretched her arm across the top shelf, groping for the box she had seen from the floor. When she had asked the cook about a box of small cups, Mrs. Ford told her to look in the stillroom. She wanted to retrieve the cups that were decorated with nursery rhyme characters to use in the nursery.

“Just another inch,” she muttered to herself as the stool wobbled under her toes.

She could have waited and asked a footman to help her, but she wanted the cups for the children’s next meal. She had read the rhymes to them, and they would be excited to see the characters. Making the youngsters smile always was a delight.

The four tots and tiny baby in the nursery, as well as the little boy who lived with the parson and his wife, had been discovered floating in a jolly boat in the harbor. Brought to Cothaire, the great house on the hill overlooking the cove, they were taken in by the Trelawney family. Its patriarch, the Earl of Launceston, had given his children carte blanche to provide for the youngsters until it could be discovered who had put them into that boat and set them afloat and why.

Shortly after their arrival, Maris was offered the position of nurse to oversee the children and the nursery. The position would end once the search for their real families proved fruitful. She should worry about where she would go next, but she spent her time focused on the children, guiding them, teaching them manners, playing games with them in the nursery.

She doted on the adorable urchins. When she was with them, she could forget why she had run away to West Cornwall in the first place. She had found a haven in Porthlowen, and the children had found a way into her heart.

A perfect solution...at least for now.

Her fingers brushed the edge of the box she sought. It rocked.

“C’mon,” she murmured. “An inch more.”

Could she stand higher on her toes? She tried and managed to push aside the box beside the one she wanted. It bumped into others, and one toppled onto another. She held her breath, but nothing fell to the floor.

One more try.

Extending her arm and hand as far as she could, she hooked one finger over the side of the box. She drew it back carefully. It moved an inch, then stopped.

“Bother!”

She was not going to give up. She gave another tug, then a harder one.

Too hard. Her finger popped off the side of the box. The motion propelled her backward. She windmilled her arms before grasping the edge of the shelf. The stool stopped rocking beneath her. She let out her breath in a soft sigh. That had been close.

Suddenly, an arm wrapped around her waist, yanking her off her feet. A shriek burst from her throat. The moment her toes touched the stone floor, she was shoved against the lower shelves. As she was held there by a firm chest, terror took control of her. No! She would not let this happen. Not again! She tried to pull away, but broad hands tightened on her.

Exactly as hands had at her dear friend’s house that evening when Lord Litchfield refused to let her escape him as he squeezed her to the shelves behind her. The brash, flirtatious young lord had proved he was no gentlemen when he had chanced upon her in the book room. The echo of her own screams burst from her memories, his breath hot against her face, the screech of ripping fabric...the laughter of his friends.

Not again! She would not let it happen again.

She drew back her arm and drove her fist into her captor’s gut. Air whooshed out of him, but he did not release her. She aimed her fist at him again. She froze when boxes cascaded down beyond her captor. They struck the stone floor and broke apart. Wood splinters flew in every direction. He pushed her head to his chest. His face hid in her hair. Glass shattered, and metal clanged.

Silence except for her uneven breathing...and her captor’s. No, not her captor. Her rescuer!

Voices rang through the room. She started to raise her head, but the man pushed it against him again. She opened her mouth to protest. Anything she might have said vanished as another storm of boxes fell from overhead, crashing and splintering.

The man holding her recoiled toward her. Had he been struck? She did not move until he lifted his head off hers as silence returned.

“Are you hurt?” called Mrs. Ford from the direction of the kitchen.

Maris opened her eyes and closed them as a cloud of dust and debris swirled around her. How many boxes had fallen? There had been more than a score on the topmost shelf and many others on the lower ones.

Mrs. Ford’s voice grew more frantic. “Are you hurt? Miss Oliver? Lord Trelawney?”

Lord Trelawney?

In horror mixed with dismay, she looked up at the man who still held her close to the shelves. She was accustomed to looking down when she spent time with the children, so it felt strange to raise her eyes to his. Arthur Trelawney, the earl’s heir, was strikingly handsome with his ebony hair that curled across his forehead. She had seen him on occasion in Cothaire’s hallways, but never this close. His face was tanned, for he often rode across the estate on the family’s business. Because his features were sharply drawn, when he moved changes of light and shadow played along them intriguingly. His dark navy coat, which accented his broad shoulders, was cut to his specifications by a skilled tailor. His crystal blue eyes were bright as his gaze moved up and down her.

She tensed, too conscious of how close they stood, for she was aware of each breath he drew in. She must look a complete rump. Her apron was stained with food from the children’s luncheon, and her hair was escaping from its sedate chignon to wisp around her face as if she were a hoyden racing across the garden.

“Are you hurt?” the viscount asked.

“No.” She hastily looked away. Why was she gawking like a foolish chit when she should be apologizing? “My lord...”

He waved her to silence, stirring the cloud of dust, then called, “Mrs. Ford, we are unharmed.”

“I will send Baricoat for footmen to clean up the mess,” the cook said, then ordered one of her kitchen maids to take her message to the butler. “I am relieved to hear you are not injured, Lord Trelawney.”

His name was an awful reminder that Maris had struck the earl’s heir when he was trying to keep her from being hurt. She must hope that he would not give her the bag for such outrageous behavior. Where could she find another safe place to hide?

Again she began, “My lord, I am sorry—”

“One moment.” He vanished into the brown cloud, and she heard china crack under his boots.

A burst of damp autumn air swept into the room, and the dust was flushed out through the stillroom’s garden door. Blinking, Maris coughed as she breathed in fresh air to cleanse her lungs.

When a handkerchief was held out to her, she took it with a whispered, “Thank you.” She dabbed her watery eyes, then faltered. Blowing her nose on Lord Trelawney’s handkerchief did not seem right, especially if he expected her to return it to him.

As if she had spoken her uncertainty aloud, he said, “You may leave it in the laundry, Miss Oliver.”

“I shall.” She took a steadying breath, then looked at him again. There was something about his cool blue eyes that sent a pulse of warmth through her, even though his terse answers suggested he wished to put an end to this conversation immediately. So did she before she said the wrong thing and jeopardized her position at Cothaire. “Thank you, my lord, for saving me. Please forgive me for striking you.”

“I...I shall survive.” A faint smile tugged at his lips, but was gone so quickly that she was unsure she had seen it. Again his pale eyes examined her without hesitation. “You?”

“I am fine, my lord.” Her voice was unsteady, and she was shocked how a wisp of a smile could send another beat of a sweet sensation through her.

“Good.”

She waited for him to say more, but he was silent. Was he waiting for her to speak or move away? Uncertain, she blurted out the first thing that came into her mind. “Next time I need something on a high shelf, I will ask for help.”

“Good.”

She wished she could be as calm as he was. Her knees trembled with the residue of her fear. The memories that usually only haunted her in her nightmares had surged forward the moment he had touched her.

Or was it something other than serenity that kept his answers short? The household maids had warned her that the viscount seldom spoke to anyone other than his family or the upper servants. Some believed he was arrogant; others more graciously suggested he might be so busy with his many tasks that he was lost in his thoughts and did not notice anyone around him. A few whispered that he simply was shy.

When Lord Trelawney strode over broken crates and crockery toward the kitchen door, Maris remained where she was. She was not sure which opinion was correct. He had spoken to her. However, he said only as much as necessary. He had come to her rescue, but Lord Litchfield had acted caring, too, before he had forced himself on her. She once had prided herself on being a good judge of character. She had been a fool when she let herself trust Lord Litchfield instead of making sure she was never alone with him. She was no longer that naive girl, and she would not be want-witted with another man, whether he be a gentleman of the ton or a lowly laborer. Before coming to Cornwall, she had chosen the most unflattering clothes and hairstyle. No man in Porthlowen had given her a second look, just as she wished.

But Lord Trelawney had given her a second look...as Lord Litchfield had. She did not want to think of what could happen, but she must be careful. Unlike with Lord Litchfield, warmth had bubbled within her when the earl’s heir smiled at her. Letting her thoughts wander in that direction could ruin her as surely as Lord Litchfield had vowed to do.

She knew better than to trust any man. She must make sure she could always trust herself.

* * *

“And I assume you will be prepared to announce your plans to marry her before Christmas.”

Arthur Trelawney, heir to the Earl of Launceston, fisted his hands behind his back as he listened to his father. He wondered if the whole world had gone mad. What other explanation was there for his father’s plan for his older son’s future? Maybe one of those boxes had fallen on Arthur’s skull in the stillroom. He had thought his only wound was a small cut on his nape where a china shard had struck him while he tried to protect Miss Oliver. He should have moved out of the way, but had kept his face pressed to her golden hair, which was laced with the faint scent of jasmine.

By all that’s blue! He should not be letting his mind wander to the pretty nurse. And she was a delight for the eyes, something he had not noticed until they stood close. The few times their paths had crossed before, she had hurried in the opposite direction as if hounds were at her heels. His impression had been of her gray gown and tightly bound hair.

No, he had no time to think of that. Instead, he concentrated on his father. All his life, he had admired the Earl of Launceston, who handled the most dire emergency with a cool head. Even when Father’s health began to trouble him, condemning him to pain-filled days and sleepless nights, he had accepted God’s will without railing or rancor.

But now...

“Pardon me,” Arthur said, struggling to keep his voice even. He needed to emulate his father and deal with this unexpected situation with aplomb and solicitude.

As Father had always done, until this outrageous conversation.

“Yes, son? Do you have a question?”

He had a thousand questions, but the foremost one was why his father was acting bizarrely. Instead of blurting that out, Arthur said, “Forgive me, but this is abrupt. When you asked me to come here, I did not expect you to make such a request.”

His father leaned back in his favorite chair in his favorite room. The smoking room’s windows provided a view of the garden and the moors beyond it. Paintings of horses, some life-size, and hunt scenes were interspersed on the walls along with swords and antiquated pistols. It was a man’s room where women were seldom welcome.

“You are my heir,” Father said, “and it is high time you have an heir of your own.”

“But—”

He did not let Arthur finish. Or even begin. “Lady Gwendolyn Cranford is the daughter of my oldest friend.”

“Gwendolyn?” That was not a name he had thought to hear during this conversation. Perhaps there was more to his father’s request than he had guessed. Or his father truly knew. He must proceed with care. He decided the best course would be to act as if his late best friend’s wife’s name had not set him on alert. “Yes, of course I realize her father is Lord Monkstone, your friend since you were in school together. That does not explain your request.”

“Since his daughter was widowed by that heinous attack on her husband by a low highwayman, and left with two young children, Monkstone has fretted about her future. As I have about your future, son, and the future of our family’s line. How better to ease our disquiet than solving both with a single offer of marriage?”

It took all of Arthur’s willpower not to retort that he believed Louis Cranford’s murder had not been a bungled robbery. Someone must have made it appear so, because Cranny, as Arthur thought of him, could have easily fought off a highwayman. His death was murder, and Arthur had futilely sought that cur for more than a year.

“I have not spoken with Lady Gwendolyn since the funeral.” Lord, help me keep from lying. Guide me in choosing words that are truth-filled, but allow me to conceal the truth that could endanger my family.

Arthur had also spent the past year fulfilling Cranny’s duties as a secret courier for the government. No one but Cranny’s wife knew of his work passing along information from the Continent and the war against Napoleon. She had asked Arthur at her husband’s funeral to take over the task of conveying coded messages across Cornwall. He had agreed, and so far his family was none the wiser. He explained his absences by saying he was checking the tenant farms on the estate. And he did so, because he refused to lie, but those visits were the perfect cover for his other activities.

He had hated lying and liars since Diana Mayfield made a chucklehead of him by feeding him such a banquet of falsehoods that he had fallen deeply in love with her. He was ready to ask her to be his wife when he had learned how she was making a fool of him. She had left without looking back and found herself another gullible sap, who did not care that she had a bevy of lovers. After that, he could not help seeing how many aspects of the courting rituals were based on half-truths. He had withdrawn from such games and gained a reputation of being either shy or arrogant because he kept to himself.

“Lady Gwendolyn is lovely,” the earl went on, drawing Arthur back to the conversation, “and she has a placid disposition.”

“I am aware of that.”

“Yes, I thought you might be.” Father held up a folded page sealed with dark blue wax. “This arrived for you today. You and Lady Gwendolyn have been writing to each other often. I suspect Monkstone has taken note, and he contacted me about a match between his daughter and you.”

Arthur reached out to take the note, wincing as the simple motion stung his nape where he was cut. He refrained from snatching the page, tearing it open and reading its contents, which would be in the code Gwendolyn used when communicating with him. She was his primary contact, and he always received his orders through her. Instead, he thanked his father, as if the page were of the least importance.

“Monkstone assures me,” Father said, “that his daughter is an accomplished hostess and her needlework is exquisite.”

Arthur might have laughed if the situation were different. He doubted many men chose their wives because of their skill with a needle.

“I know she is a paragon,” he replied, eager to put an end to the conversation so he could read Gwendolyn’s message. “But, Father, it is October, and I doubt I will have time to call on the lady before—”

“No need to worry about that.” Father pyramided his fingers in front of his face and smiled through them, his silver-gray eyes bright. “Miller is planning a hunt gathering early next month. He sent us an invitation along with his hopes that you would take time to be there.”

“A hunt gathering?” Arthur frowned. “I have never heard of a justice of the peace hosting such a costly event.”

“Mr. Miller is, as you must have seen, determined to elevate his status from country squire to nobility.”

“By hosting a hunt?”

“If he impresses members of the ton, who knows what might happen? But that isn’t important. What is important is that Monkstone and his daughter will be attending. I cannot imagine a better place for you to prepare an announcement of your impending nuptials.” Father chuckled. “If God grants me another year on His good, green earth, I may be bouncing your heir on my knee by next Christmas.”

His father had every detail set, so Arthur knew this decision was not a spur-of-the-moment one. Father and Monkstone must have been discussing this for some time.

However, Arthur was intrigued by the idea of a hunt. Miller, the justice of the peace, was an encroaching mushroom, and he would invite every member of the ton in southwest England. Among the guests might be the person who had murdered Cranny or ordered his death. Only a member of Society could have arranged for the number of horses and riders seen fleeing from the site of the attack. Even the most successful highwayman seldom had more than a few men accompanying him.

Father must have taken Arthur’s silence for acquiescence, because he continued, “You will be able to court Gwendolyn during that hunt. After all, she is a widow and you are past your thirtieth birthday, and you have known each other for a long time. So it is not as if you have to woo her with rides in Hyde Park and act as her escort to assemblies in Town. You need do little other than ask her to wed you.”

Arthur nodded. In the past year, he had pushed the idea of finding a wife to the back of his mind, focusing rather on his duties as a courier and overseeing the estate on his father’s behalf. Apparently, during that time, his father had given up on Arthur finding a bride on his own.

As if privy to his thoughts, Father asked, “Well? Don’t you see this is a good solution?”

“I think the plan has merit.” That was a safe answer, because he would make no promises until he had a chance to speak with Gwendolyn. Was she even aware of the plans to provide her with a husband? It was true that Arthur needed a wife and an heir, and maybe Gwendolyn was being pressured by her father. If so, such a union would not be the worst in history, though it would be no love match.

“I am glad you see it that way.” Father became abruptly serious. “If my health was not failing, I would not insist on such an arrangement.”

“You will be here for many more years,” Arthur replied.

“I will be here as long as God wishes me.” Father scowled as he shifted his ankle, which was swollen with gout. “Mr. Hockbridge tells me that the chest pains I have been suffering can be deadly.”

Arthur had noticed his father’s pallor, but had not realized he had conferred with the village doctor. Up until recently, his father had worn the dignity of his age with ease. His hair, once as black as Arthur’s, was turning gray. His gout symptoms returned more frequently. In addition, life had become far more frantic in the house and Porthlowen Cove since six small children were discovered floating in a rickety boat in the harbor. The situation had grown quieter in recent weeks on the estate. The stable had been set afire by the French sailors who tried to overrun Porthlowen last month. Now those pirates were in prison. Arthur’s younger sister, Susanna, was away on her honeymoon, and the harvest was almost in on the tenant farms. All messages he had been given were on their way toward London. Everything was going as it should...

Except he had not unmasked the person who had murdered Cranny.

“Thank you, son, for agreeing to such an outlandish request,” Father said.

“Not outlandish,” came a light voice from near to the doorway, “for daughters have been asked to do much the same throughout time.”

Arthur glanced over his shoulder as his older sister, Carrie, came into the room. She was teasing, but her blue eyes, the same deep shade as his own, snapped with strong emotions. He wondered why. Had something been discovered about the baby in her arms? His sister called the youngest waif Joy. Since the children were rescued in Porthlowen Harbor, the baby had seldom been out of his sister’s arms. She was happier than she had been since her husband’s death at sea five years ago.

His siblings were, in his opinion, baby-mad. Carrie with baby Joy. His brother, Raymond, and his new wife, Elisabeth, had one of the older boys, who was close to four years old, living with them at the parsonage. His younger sister had become attached to a set of twin girls, who were a year younger.

His family had, it would appear, lost their collective minds. These children came from somewhere. They belonged to someone. Eventually they would have to be returned to those people. And the rest of his family would be lost in grief, as they had when Mama died around the same time as his brother-in-law. Arthur hated the idea of that. They had mourned enough for the past five years.

“Caroline, come and join us,” Father said with a smile.

The rest of the family used her full name, but Arthur continued to think of his older sister as Carrie, the nickname he had given her when he was young and could not pronounce her full name. She was a lovely woman who carried a bit more flesh than the ton considered acceptable. He used to tease her about being well-rounded, but he had set aside such jests years ago.

She gave Father a kiss on the cheek, then straightened. “Arthur, I had hoped to find you,” she said in that same carefree tone. “May I speak with you?” She gave the slightest nod toward the hallway.

He swallowed his sigh at another delay before he could read Gwendolyn’s message, but looked at Father. “If you will excuse me...”

“Go, go. I am sure you have many matters to consider.” His father’s smile returned.

Arthur nodded. He did have many matters he should be thinking about. On the family’s vast estate set on the sea and across the Cornish moors, there were repairs to the faulty barn roof on Pellow’s farm and the new well that must be dug before winter for the Dinases’ farm. The old one had suddenly gone dry last week. It might be because of a new tin mine being dug south along the moor, or it could be another cause completely. First, they must get a new source of water; then they could investigate why the well had dried up.

How could he think of any of that when he was curious about what Gwendolyn had written?

Carrie said nothing as they walked to the small drawing room they used en famille. French windows opened onto a terrace with a vista of the sea and the garden. The Aubusson rug with its great white roses was set in the middle of the room, and furniture was spread atop it to allow for easy conversation.

His sister sat in a chair not far from the hearth. Not that he blamed her. The fire burning there chased away the autumn afternoon’s chill. When she motioned for him to sit, he shook his head.

“I would prefer to stand...unless this conversation is going to be a long one.”

“That is up to you.” The lightness vanished from her voice, and her eyes narrowed.

“Me? You asked me to speak with you.”

“Because I am sure you have many things to say about Father’s plan that you would not in front of him.”

Arthur was not surprised that Father had discussed with Carrie the matter of a match between him and Gwendolyn. Since their mother’s death, his older sister had become Father’s sounding post.

“I never expected Father to ask this of me, Carrie.” He leaned forward and put his hands on the settee.

“It is your duty to marry.” Her voice gentled. “Father expected an announcement by the time you celebrated your thirtieth birthday.”

“I have been busy with other duties.” That was his usual excuse.

She gave him a sympathetic smile. “I know that you have been avoiding the ton since that incident with Miss Mayfield, which is why when Father told me about this arrangement he has made with Lord Monkstone, I did not say that I believed the whole of it was addled.” She looked at him directly. “Tell me, Arthur. Are you truly agreeable with this match?”

“As you said, daughters have come to terms with such arrangements for millennia.” He ran his hand through his hair, grateful that he did not have to lie.

“I know. Will you be able to ask her?”

Her question startled him. Then he reminded himself that his sister believed, as most of the world did, that he was too shy to say boo to a goose. He had never corrected the mistaken assumptions. “I would hope so. There must be some way.”

“You are resourceful, Arthur.”

“I suppose I could write a flowery poem that ends with ‘Will you marry me?’”

“Writing love missives is all well and good, but you have not made her an offer of marriage.” A smile tipped Carrie’s lips. “Don’t look surprised, Arthur. You should know that nothing stays a secret for long here, especially when you receive letters from her week after week.”

He hoped his sister was wrong, because no one else must learn how he had assumed Cranny’s secret duties. As long as everybody believed the notes were focused on avowals of love, his secret should be safe.

“I know you probably find it simpler to put words on paper than to speak them,” Carrie said, “but even if you propose via a love poem, you still must say ‘I do’ at the front of the church.” She reached out and patted his hand. “But let us take one step at a time. There must be some way to make it easy for you to propose to Lady Gwendolyn.” She rose and began to pace in front of the French windows. When the baby began to fuss, she paused. “I must take Joy to be fed. Oh!”

“Oh?” he asked.

“It is simple. Why didn’t I see that before?” She crossed the room and placed the baby in his arms.

He tensed, because he had never held such a tiny infant. His nose wrinkled at the odor of a dirty, wet napkin. “Carrie, I am not accustomed to little babies.”

“I know. The practice will do you good, especially because Lady Gwendolyn’s younger child isn’t much older than Joy.” Carrie’s eyes filled with tears. “How sad to have a child born after the death of its father.” She squared her shoulders, all business once again. “The other is about three or four years old. My advice to you is to get those children to like you, so she will see you are sincere even if you are hesitant when you ask her.”

“Why?”

“The quickest way to a woman’s heart is to win the hearts of her children.”

He did not say that hearts had nothing to do with the arrangement he and his father had discussed. Something twinged in his chest. Regret? He disliked the idea of a loveless match.

The baby grumbled and wiggled. He shifted her so he would not drop her. As he looked down at her tiny rosebud mouth, he asked, “And how do you suggest I win over her children?”

“Play with them. Talk to them.”

“I honestly don’t know much about children.”

“Then learn.”

“You make it sound easy.”

Carrie grinned. “Isn’t it? There are five small children living under our roof and another staying with Raymond and Elisabeth at the parsonage. Why not practice with them?”

“I would not know where to begin.” Or when I would have the time. If Gwendolyn’s message requires me to travel, I must take my leave immediately. He yearned to tell Carrie the truth, but bit back the words.

She stepped behind him and put her hands against his back. Giving him a slight push, she said, “Start with the expert. Ask Miss Oliver. She will be glad to help, especially after you gallantly rescued her this afternoon.”

Glancing over his shoulder, he chuckled. “You heard of that.”

“Even if the sound of crates falling had not resonated through Cothaire, do I need to remind you that nothing stays secret here?” Not giving him a chance to reply, she said, “Will you ask for her help?”

“Yes.” He would have to find a way to balance his sister’s request with his other tasks.

“Off with you then. Joy needs to be fed, and taking her to the nursery gives you the perfect opportunity to speak with Miss Oliver.”

He walked to the door. Another delay before he could read the note after he deciphered it, but the visit to the nursery could be done quickly. He would go through the motions of spending time with the children so Carrie did not become suspicious. Once he had a chance to read Gwendolyn’s message, he would know what he needed to do next. Going to the nursery would not take much time.

And he could see Miss Oliver again to assure himself that she had recovered from the fright of the boxes falling on them. He would give her the baby, ask for her help to convince his family he was making an effort to be a good suitor for Gwendolyn, and then retreat to his private rooms to read Gwendolyn’s message. What could be simpler than that?

Chapter Two (#ulink_1ad72c45-6812-5c3a-b0d2-628c53cff427)

“Look! Look! Look!”

Maris smiled at the children as she selected one of the storybooks on the shelf in the Cothaire day nursery. It was their favorite book. She wanted to read it to them before their tea was brought up, along with four of the child-size cups that had survived falling off the shelf. Eight were usable, and two more were being glued together. The rest had smashed into too many pieces to try to repair.

Putting the book under her arm, she went to where Gil and Bertie pointed out the window overlooking the harbor. She knelt on the padded bench there and shaded her eyes as she scanned the waves, which glittered like dozens of fabulous diamond necklaces.

“I see it,” she said, when she realized the little boys were gesturing toward the sails of a ship far out near the horizon. Bertie was, by her estimation, at least four years old, while Gil probably had his third birthday not too long ago.

“Cap’s?”

Before she could answer Bertie, the three-year-old twin girls who had been playing with dolls by a large dollhouse repeated, “Cap?” They jumped to their feet and ran to the window. “Cap’s boat?”

“No,” Maris said, shifting to give Lulu and Molly, the twins, room to get on the bench. She hated dashing the children’s hopes. They missed Captain Nesbitt, who had rescued them from Porthlowen Harbor, but he was not due back for at least another fortnight.

“No Cap’s boat. No Cap for Wuwu.” Lulu’s lisp mixed with her mournful tone.

“But it is a pretty ship.” Maris stood to give the girls more room.

The four youngsters plus baby Joy kept her busy. On occasion, Toby, the sixth child from the jolly boat that had drifted into Porthlowen Harbor, came to play with the others. He was close to Bertie’s age. Parson Trelawney and his wife had offered to take the little boy the first night, when Toby and Bertie would not stop annoying each other. That temporary solution had become permanent...or permanent until the truth about the children could be uncovered.

Maris watched the children, who chatted excitedly about the ship and what might be on it and where it might be bound.

“Ship go bye-bye.” Lulu’s voice was sad.

“Bye-bye, ship,” echoed her twin.

Maris sat beside them and held out her arms. The children nestled next to her, and she drew them closer. Talking to them about the day they had toured Captain Nesbitt’s ship while it was being repaired in the harbor, she was glad to see their sweet smiles return.

Who had abandoned these children in a jolly boat that was ready to sink? If Captain Nesbitt and his first mate had failed to see them and come to their rescue, the children could have been dashed upon the rocks in the cove. Whose heart was so unfeeling? As she stroked the silken hair on their tiny heads, Maris wondered why someone had put them in that boat. The children were too young to explain, and every clue had led to a dead end.

“Shall we sing a song about a ship?” she asked, grateful that, no matter how they had come to Cothaire, they were safe.

The two boys began singing. The tune did not resemble the one she had taught them and half the words were wrong, but their enthusiasm was undeniable.

They broke off as footsteps came toward the nursery. Strong, assertive footsteps. The servants were quiet when they walked through the house. Maybe the parson was bringing Toby to play with the children.

Hushing them, Maris disentangled herself and eased out from among them. She brushed her hair toward her unflattering bun as she stood. She opened her mouth, but then realized the silhouette in the doorway was taller than the parson or his wife.

“Miss Oliver?” asked the Earl of Launceston’s older son. He stood as stiff as a soldier on parade.

“Lord Trelawney,” she squeaked, sounding as young as her charges.

What was he doing here, so soon after the mishap in the stillroom? In the weeks since her arrival at Cothaire, the viscount had never come to the nursery. Not that she had expected him to, because his duties lay elsewhere. Still, it had seemed odd, when everyone else in the family, including the earl, had stopped in once or twice to ask how the children fared.

Uneasiness tightened Maris’s stomach. Had the viscount come to dismiss her? She could have misread his concern for her well-being. She had been wrong about men before, terribly wrong.

Could it be almost a year ago when she had made her final visit to her friend Belinda, the daughter of an earl? Because Maris’s father was a country squire whose tiny estate bordered Lord Bellemore’s vast one in Somerset, the two girls had spent many hours together as children. As they grew older, they had less in common, but after Maris’s parents died, Belinda had invited her to stay. Her widowed father often needed another female to even the numbers at the table. Dear Belinda was oblivious to the disapproving glances in Maris’s direction, but Maris had been aware of each one from the earl’s other guests.

If she had not offered to get a familiar title from the earl’s book room to read her friend to sleep that evening...

Maris wrapped her arms around herself, holding herself together. It would be easy to fall apart whenever she thought of Lord Litchfield and what he had done. No! She was safe at Cothaire.

Or was she? The nursery was on the upper floor where few adults came. Lord Trelawney would know that she was alone.

Stop it! If you offend him by accusing him falsely, he will dismiss you without a recommendation to help you get another position. Not that she had been unable to solve that problem in getting her current position, but she might not find another household with such a need for a nurse that they gave the fake recommendation she had penned herself such a cursory examination. Familiar guilt at her lie pinched her, but she had been desperate.

“Some help, please,” Lord Trelawney said in his rich, baritone voice.

Astounded, she realized he carried Joy— awkwardly, as if he feared he might drop the infant at any moment. “I will take her. Thank you.”

Little Gil raced after her, crying with excitement, “My baby! My baby!” No one knew if Gil and Joy were actually brother and sister, but the little boy had laid claim to the baby after being rescued.

Maris calmed him and the other children, who clustered around her and the viscount. She held out her arms and repeated, “I will take her, my lord.”

“May I...?” He glanced at the children and cleared his throat. “May I come in?”

Every instinct urged her to say no, but she really had no choice. She put space between them, herding the children away from the doorway. They wanted to greet Lord Trelawney with the same enthusiasm they showed everyone, but she doubted the cool, composed man would welcome their curious questions or their fingerprints on his pristine black coat. As he came into the room, she stepped around the small table where the children ate. It was not much of a shield, but it was all she had.

You are being silly, that soft voice whispered in her mind. Lord Trelawney is not Lord Litchfield. He has never been anything but polite when he passed you in an empty hallway. And he did save you from injury earlier.

Maybe so, but she would not take the chance of being hurt by another man and then abandoned by those she thought she could depend on.

“Will you...?” He motioned with his head toward the baby.

“Certainly.” She left her scanty sanctuary and scooped Joy into her arms, then wrinkled her nose. “She is rather pungent, isn’t she?”

He glanced down at his sleeve where a damp spot warned that the napkin had leaked. “Yes.”

“I shall see that she is changed and fed, my lord. Thank you.” The nursery seemed oddly cramped with him in it. Or maybe it was because the children gripped her skirt, making it impossible for her to edge away again. “I assumed Lady Caroline would bring Joy to the nursery.”

“Yes, my sister seldom is parted from this baby. I hope...” He did not finish.

He did not need to, because Maris understood. Lady Caroline would be bereft when the baby’s parents were found.

“You look well, Miss Oliver,” he added.

She was startled, then realized he must be referring to what had occurred in the stillroom. “Thanks to you.” She lowered her eyes. “I hope your injury was minor.”

“How did you know?”

“We were standing close, and I felt you flinch as the debris flew about.”

He smiled. “’Tis a scratch.” He paused for so long that she thought he was done; then he said, “I appreciate you asking.”

Laying the baby on the higher table, where a stack of fresh napkins waited, Maris began to change Joy. She was aware of Lord Trelawney behind her, even though he was silent. After sending the children to play, she looked at him.

“Is there something else you need me to do, my lord?” she asked.

“’Tis my sister. She thought it was time that I visited the nursery and learned more about the children living here.”

“She did?” What a peculiar suggestion! In an upper-class home such as Cothaire, the children’s lives seldom intersected with their elders’. “Of course, you are always welcome.”

“She suggested that... That is, she thought you might guide me in getting to know the children better.” He glanced at where the twins were chasing the boys. “Next month, I will be spending time with a widowed acquaintance who has two children of her own, and Carrie thought if I learned about these children, I would have an easier time with meeting Gwendolyn’s.”

Maris put a clean napkin on the baby and pinned it in place. It would seem that Lord Trelawney had made his choice of a bride. She had heard the household staff discussing whom he might choose and how his new wife might change Cothaire. No doubt the widow’s name was being discussed in whispers in the servants’ hall.

Lifting little Joy from the table, Maris cradled her close to her heart. The baby’s mouth tasted the air, a sign that she wanted to nurse. Maris watched Lord Trelawney gaze down at the child. He lightly touched her soft hair, his expression unguarded for a moment.

Biting her lower lip, Maris said nothing. If she expressed how endearing it was to see the oh-so-correct viscount reveal a tender vulnerability, she might embarrass him. She did not move as he looked from the baby to the other children, his thoughts bare on his face. He was perplexed by them, but fascinated, too. Few strong men would reveal that, nor would they be concerned about the well-being of a servant who had caused an accident in the stillroom.

As he gently brushed the baby’s head, he looked up. His gaze caught Maris’s, no longer cool, but filled with emotions she could not interpret. Standing with the baby between them, she noticed, as she had not before, that darker navy rings encircled the pale blue of his eyes. She never had seen any like them. Her fingers tingled, and she had to fight to keep them from rising to curve along his cheek as she told him how sweet she found him to be with the baby. Being so bold might suggest she was the easy type of woman Lord Litchfield considered her.

That thought compelled Maris back a half step. “Lord Trelawney, we can discuss how you can get to know the children better once I take Joy to the wet nurse. She is waiting in the kitchen.”

His hand hung in the air now that Joy’s head was no longer beneath it. He lowered it. “I should go. I need to—”

The other children shrieked as they raced from one side of the room to the other, giggling.

“I will be but a moment.” Maris pointed to each child and spoke his or her name, before adding, “Children, this is Lord Trelawney. He is Lady Susanna’s older brother. Just like Parson Raymond.”

They smiled at him, but uneasily, then looked at her. Had they sensed, as she did, that he wished he were somewhere else? With a sigh, she suggested they go to the window to see what else they might spot outside. They clambered onto the window bench. She hoped they would remain distracted and well behaved until she returned.

She lowered her voice as she turned to the viscount. “Watch so they don’t get hurt. I shall be right back.” She hurried to the stairs leading down to the kitchen, before she laughed out loud at Lord Trelawney’s expression.

He had looked unnerved at her suggestion that he stay alone with the children. Could he truly have no experience with little ones? Lady Susanna was more than a decade younger than he was, so he must remember her as an infant and toddler. Then Maris remembered that Belinda’s brother had been sent away to school by the time he was ten. Most likely, Lord Trelawney had been attending boarding school when Lady Susanna was born.

In the kitchen, Maris handed Joy to the young woman who came from the village several times each day to nurse the baby.

Mrs. Ford looked up from stirring a bowl. “Miss Oliver, I cannot believe you left those young ones on their own upstairs. That is not like you.”

“I didn’t leave them alone,” she said.

“Lady Caroline has more important—”

“I did not leave them with Lady Caroline.”

She had the attention of everyone in the kitchen, and one of the maids blurted, “Then who?”

“Lord Trelawney.”

Gasps rushed around the kitchen, quieting when Mrs. Ford gave her staff a frown. Putting down the bowl, the cook wiped her hands on her apron as she walked over to where Maris stood with her foot on the first step of the nursery stairs.

Too low for anyone else to hear, the cook asked, “Is this a jest?”

“No.” Maris could trust Mrs. Ford, who had begun her service at Cothaire before Maris was born. “Lady Caroline suggested he get to know these children better before he meets the children of a lady named Gwendolyn next month.”

“Ah.” The cook smiled. “Thank God! Lord Trelawney is going courting.”

Maris put her finger to her lips. “Shhh!”

“You don’t need to shush me. I know how to keep my mouth shut about the family’s business, but this is good news, it is.” Sudden tears bloomed in the cook’s eyes. “It is high time for Lord Trelawney to take a bride and spend less time riding around the estate. He needs to be here for his father. The earl is not well, and it is important for him to see his heir’s heir.”

Maris nodded. She deeply missed her own parents, who had died when she was sixteen. Her one comfort was that she had had many wonderful days with them. Lord Trelawney had his duties, but those should include treasuring every moment he could with the earl.

“Do your best to help him, Miss Oliver, and you will have done this household a great service.” The cook returned to her task without waiting for an answer.

Maris went up the stairs, then paused on the landing near the day nursery door. If his intentions were to marry the lady named Gwendolyn, why had he gazed intently at Maris with those incredible eyes? Or had she read more into the moment than he intended? She was a poor judge of men; that much was for sure. She should not accuse Lord Trelawney of a misdeed when he might not be guilty. His attention might have been on Joy rather than on her. After all, she was the nurse, and he saw her as a useful tool to help him learn more about children.

Perhaps he might even be grateful and let her stay on at Cothaire. Even after the children’s pasts were uncovered, a nurse would be needed for Lord Trelawney’s children. That would mean Maris would be assured of a roof over her head and plenty of food for years to come. She had learned about the fear of hunger after her parents died, and the debts they had amassed in order to live at the edges of the ton had consumed the money from the estate’s sale. Only the generosity of her friend had enabled Maris to survive.

Equally as important, she would be invisible in the nursery, so she could avoid lecherous men like Lord Litchfield. While she did her best to assist Lord Trelawney, she would wisely make sure they were never alone. So far, he had been kind to her, but she would not be duped again.

A cry came from the nursery. Maris threw the door open and rushed in.

Lord Trelawney had not moved, but heaps of toys surrounded him. The poor man looked as lost as an explorer on an untouched shore. The children danced around him, singing of ships.

He glanced toward her as she came into the nursery. With relief, she noted.

“I am back, Moses,” she said with a laugh she could not silence.

“Moses?”

“Your expression reminded me of when Moses said, ‘I have been a stranger in a strange land.’”

The viscount’s brows arched, and the corner of his lips curved.

She looked away, shocked by her own words. To speak brazenly to him was unthinkable. As unthinkable as her quoting a passage from the Bible. Even though she had attended church since her arrival in Porthlowen, she had not prayed since she fled from her friend’s house after the attack. God had not heard her in the midst of the attack and sent someone to save her. Afterward, when Lord Litchfield threatened her with ruin and her friend’s family turned her out because they believed his lies that she had tried to seduce him, she wondered if He had ever listened to her.

She was saved from her own thoughts when the children ran to her, greeting her as if she had been gone for five days rather than five minutes. She hugged each one, but spoke to Lord Trelawney. “I assure you, my lord, that they do not bite, except each other occasionally, but we are working on that.”

“No bite,” Bertie said, as serious as a judge pronouncing a sentence.

She fluffed his hair, which was fairer than her own. “That is right.”

The viscount glanced toward the door, clearly eager to make his escape.

“My lord,” she continued, when he did not answer, “may I suggest you join the children and me on our walk tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow? Where?”

She hesitated. The obvious place was a section of the cove’s sandy shore. Many of the buildings in the village, including the parsonage, overlooked it. The nearby harbor always bustled with activity. There, she would never be alone with Lord Trelawney.

“Down to the water,” she said. “With their short legs, that journey is enough to tire them out long enough to sit still. While we are there, you can talk to them.”

“About what?” His full attention was on her.

“Whatever you or they have on their minds.”

“That should be interesting.” He bid her a good day and strode toward the hallway door.

Beside her, Lulu asked, “Is the big man coming back?”

“Yes.” And she must be prepared. She could not make another horrible mistake as she had with Lord Litchfield.

* * *

Arthur had half hoped that Miss Oliver would send him a note that neither she nor the children were going to visit the harbor. He could have used the time instead to encode a message to Gwendolyn and ask what was in the message she had sent to Cothaire. Either she had changed the code without alerting him, or she had made mistakes in writing the note. It made no sense other than a few random words.

Or had he made the mistakes? He had checked the message a second time and still it made no sense, but he admittedly was distracted. Miss Oliver kept popping into his mind. The shapeless apron she wore over her gray dress failed to hide her pleasing curves, and her smile lit her pretty face. He wondered why she made such an effort to appear drab.

As he walked across Cothaire’s entry hall, he warned himself to keep his mind on the task of getting to know the children, not their nurse. He had agreed to Carrie’s request, and he must do as he promised. And, he reminded himself, the outing would keep him from wondering about Gwendolyn’s odd message.

The breeze was brisk when Arthur emerged from the house. Lighthearted voices came from the left where the children surrounded Miss Oliver. They bounced in every direction like a handful of dropped coins, but Miss Oliver radiated calm. She answered their questions with an unwavering smile while she kept them from wandering away.

She wore a simple gray spencer and a bonnet of the same color that did not flatter her complexion. Her cheeks were brushed with a charming pink, and he could not keep from thinking of how his fingertips vibrated when they had curved around her slender waist as he pulled her out of the way of toppling boxes. The exotic jasmine scent from her hair clung to his senses, and he was curious if she wore it again today. Her deep green eyes twinkled as she reached behind her and pulled out a bag. The four children clamored to see what was in it.

When Arthur walked toward them, the younger boy noticed and raced toward him. The child stopped right in front of him. “Look! Ship!” He held up a tiny wooden ship for Arthur to see.

“Very nice,” he said.

“Go now!”

Miss Oliver took the little boy’s hand and drew him closer. “Forgive Gil, my lord. He is excited to sail his ship in the harbor.”

Arthur noticed that she did not meet his eyes, even when she spoke to him. Was she having second thoughts about helping him?

Bertie let out a shriek. The older boy’s tiny ship lay broken on the ground. It must have fallen out of his hand.

Arthur bent to collect the pieces and bumped into Miss Oliver when she did the same. A quiver, as if the earth beneath his feet trembled, rushed outward from where their hands touched. He jerked his back at the same time she did. Beneath her bonnet, her face flushed nearly to the shade of a soldier’s scarlet coat.

He was relieved when she turned away, because he did not want her to discover he was unsettled by the peculiar, fascinating sensation when his fingers grazed hers. Picking up the broken toy, he examined it. The children quieted while they waited to see what he would do or say. Balancing the tiny ship on his broad palm, he realigned the two cracked masts, then held it out to Bertie.

The little boy looked from him to the ship and back.

“I am no shipwright,” Miss Oliver said, “but I suspect it will float well, Bertie. Thank Lord Trelawney.”

Bertie mumbled something as he wiped his eyes and nose on his sleeve, then reached to take the boat.

Miss Oliver put a hand on the boy’s shoulder and asked, “Shall we go, my lord?”

He nodded. The sooner they went, the sooner he could return to write out his coded note.

As they walked down the hill toward the village, the children prattled with excitement. Miss Oliver seemed to understand everything they said, but to Arthur much of it sounded like the chatter of Indian monkeys as they all talked at once.

Miss Oliver glanced at him several times and arched her brows. He comprehended her silent question, but he had no idea how to jump into the babble. Perhaps he would do better if he spoke with one child at a time. There surely would be an opportunity when they reached the beach.

He glanced at the village as they passed its single street. It was quiet in the morning sunshine. One woman was hanging clothes near a stone cottage, and another was dumping out a bucket. Water ran between the cobbles on the steeper section that led down toward the harbor. A single word of caution from Miss Oliver kept the children from sticking fingers in the water as it rushed by.

At low tide, Porthlowen’s sandy beach was a few yards wide. It offered enough space for fishermen to pull their boats up onto the sand to work on them. Flat stretches of stone were visible where the water had pulled back. They would be invisible again once the tide came surging around the curved edges of the cove, where two sets of cliffs challenged even skilled navigators.

Arthur helped Miss Oliver take off the children’s shoes and socks. She piled them on the grass beyond the sand. Next, she tied a string connected to each tiny ship around a child’s wrist, so the toys would not be lost. As they ran to put their ships in the water, he was impressed how easily Miss Oliver managed to keep an eye on all her charges seemingly at the same time.

He walked to where the glistening blue water lapped against the shore. He should have been so cautious the year he turned sixteen. He had brought Susanna to the cove. She had been no older than the twins, and he old enough to know better than to turn his back even for a second. Yet he had, and his baby sister had almost drowned. When he realized she was gone, he had found her floating facedown in the water, and he thought she was dead. Desperate to get her breathing, he had put her over his shoulder like a baby being burped. A couple quick slaps to the back had made her vomit water, but she had begun breathing again and, in a few minutes, was fine.

But he had not been. His parents had trusted him to watch over Susanna. That was the last promise he had ever broken. He had learned his lesson that day about responsibility and God’s grace on young men who thought they knew everything.

A small hand tugged on his coat. In astonishment, he saw one of the twins had come over to him. He was not sure which one it was, because he could not tell them apart. She raised her dripping ship toward him.

“You boat?” she asked.

“No,” he answered, his throat tight as he forced the words out. “Yours.”

“Wuwu.”

“What?”

“She said her name is Lulu.” Miss Oliver joined them. “Her real name is Lucie, but we call her Lulu. She wants to know if you want to sail her ship.”

“Me?” He glanced from the child to the nurse, realizing that their eyes were almost the same color. Lulu’s were bright with innocence. Shadows clung to Miss Oliver’s, even when she smiled.

Sadness or some other emotion? He wanted to ask, but that was too personal a question.

“If you wish, my lord...” Miss Oliver’s gaze led his to the little girl, who patiently held up the boat.

He reached down. When the child grasped his hand as he took the wooden ship from hers, he was startled how small her fingers were. The last tiny hand he had held was Susanna’s...right on this shore that horrible day.

“In water,” Lulu said when he hesitated.

He motioned for her to lead the way, then asked Miss Oliver, “Are they always so bossy?”

“Always.” She smiled.

His lungs compressed, but he could not release his breath when her face shone as if she had swallowed sunlight. Her curls emphasized her high cheekbones, which were burnished by the breeze to a deeper pink. He was tempted to tell her to stop attempting to make herself look plain, because those efforts were futile and a waste of time.

“I had no idea that you were at the mercy of miniature despots,” he said, knowing he must not keep staring at her in silence.

“Fortunately, they are benevolent despots.” She laughed. “As long as they are fed on time, have plenty of toys to play with and can negotiate a few extra minutes before bed.” She stepped aside as he went with Lulu to the water’s edge. “Hold on to the string before you place the ship in the water. As you know, the currents are tricky here.”

Lulu confidently squatted and looked up, gesturing toward the sea. She could not understand why he was hesitating. The sight of a little girl at the water’s edge, unaware of the danger awaiting her if she went in too deeply, sliced into him like a fiery sword.

Maybe the whole of this outing was a mistake. He should excuse himself and return to Cothaire. Yet he had given Carrie his word that he would make an effort to get to know the children. These experiences would prove worthwhile if Gwendolyn really wanted him to marry her. He wished he could ask her, but doing so in a coded note was not the way.

Miss Oliver came to his rescue when she took the ship and placed it in the water. The toy bobbed on the waves. Rising, she glanced at him, then nodded toward Lulu before she went to check on the other three. She gently herded the children closer so they were within arm’s reach.

He looked down at the little girl in front of him. What should he say to her?

“Ask her the name of her ship,” Miss Oliver whispered.

He nodded, then paused so long that she repeated her instructions. He was tempted to fire back that he had heard her the first time. Instead, he asked, “What do you call your ship, Lulu?”

“Pony.”

“Why?”

“Pony pwances.” She smiled.

He took a moment to figure out the word her lisp distorted. “Ah, I see. A pony prances like your ship does.”

She did not answer as she drew the toy closer to her before letting it drift on the current again.

Miss Oliver edged closer, but kept watching her charges. “See? It isn’t hard to talk with children.” Suddenly she gasped and sped past him.

He turned to see Bertie chasing his boat’s string, which had come loose from his wrist. The child tried to grab the end, but the waves pulled it across the flat rocks toward deep water.

Arthur did not hesitate. He ran across the slick stones. His boots slid, but he kept going. Passing Miss Oliver, whose dreary bonnet bounced on her back, he heard her shout the child’s name.

So did the little boy. He turned and teetered on the edge of a rock.

She screamed.

Arthur threw himself toward the child, grabbing his arm. His right foot skidded as he pulled Bertie to him. A hot spear pierced his knee as he fell with the boy on top of him. Arthur’s breath burst out painfully.

Miss Oliver scooped the little boy off him and hugged him. “Bertie, you must not leave the shore.”

“Boat go.”

“We have others. Let it go. Maybe it will reach Cap’s ship.” She carried him to shore where the other children were watching, wide-eyed.

Arthur winced as he pushed himself up to sit. Every bone had jarred when he had twisted to keep from falling on the boy.

Miss Oliver rushed back to him. “Are you hurt, Lord Trelawney?” She ran her hands along one of his arms, then the other. When she started to do the same to his right leg, he grasped her arms and edged her away.

“I am fine.” He was struggling to think and did not need the distraction of her jasmine-scented curls caressing his cheek when she bent toward him.

His words must have been too sharp, because she rose and wiped her hands as if wanting to clean them of any contact with him. “I am pleased to hear that, my lord. Thank you for saving Bertie.”

By all that’s blue! He was making a muddle of everything, and he could not blame his rudeness on the pain blistering his leg. As she walked away, he pushed himself to his feet.

Or tried to.

Agony clamped around his right ankle and sent a new streak of fiery pain up to his knee. He collapsed with a choked gasp as he prayed, Lord, don’t let anything be broken. I need to continue the work I promised I would do in Cranny’s stead.

Miss Oliver whirled and ran to him. “You are hurt, my lord! Shall I go for help?”

“No. If I can...” He groaned as he tried to move his right leg.

“At least let me help you up.”

“You are too slight.”

She squatted beside him. “I am going to help you, whether you wish it or not. I do hope you will cooperate.”

She put her shoulder beneath his arm and levered him to his feet. He kept his right foot off the ground and balanced on his left. As he drew in a deep breath, it was flavored with the fragrance of jasmine, the perfect scent for her.

“Thank you, Miss Oliver. If you will release me—”

“Do you intend to hop to Cothaire?”

“No, the parsonage.” Once he reached there, his brother would help him return to the great house.

“You cannot hop that far, either.”

Pain honed his voice. “Miss Oliver, has anyone ever told you that you can be vexing?”

“Many times.” She motioned with her free arm toward the shore where the children waited. “Shall we go?”

He nodded, but groaned as he took a single step.

On the beach, Bertie cried, “Is—is—is he a bear?”

The children stared at him, scared. He must persuade the youngsters that he was no danger to them. What a mull he had made of the outing! He tried another step, then halted, realizing he had an even bigger problem. How would he be able to do his work as a courier if he could not walk?

Chapter Three (#ulink_09350dab-e1b3-5784-b8c9-48e3b5db8546)

Arthur had never been more relieved to see his younger brother than when Raymond rushed out of the parsonage. Raising Arthur’s free arm over his shoulders, his brother nodded to Miss Oliver.

She stepped back with a soft sigh. No doubt she must be glad to hand over the burden of supporting him to someone else. The walk from the beach had been slow. The only pauses were when she asked the children to collect their footwear and when she had sent two of the village boys to inform his family of his injury, one to the parsonage and the other to Cothaire. She had talked to Arthur at first, urging him forward with each step, but his silence had put an end to that. After that, she spoke only to the children.

For him, any conversation was hopeless because his teeth were clenched to keep his groans from leaking out. The children were scared of him, and he did not want to frighten them more.

Raymond turned him toward the front door. His red-haired wife, Elisabeth, held it open. Dismay lengthened her face as she stepped aside to let them enter.

Arthur propped one hand against the doorjamb, but did not enter when he heard a loud rattle and the pounding of hooves. He saw Miss Oliver pulling the children onto the grass as an open cart slowed in front of the parsonage. The driver jumped down and handed out Carrie, who, for once, was not holding the baby.

That did not halt the littlest boy from running to her as he called, “My baby!”

She bent and said something to him before taking his hand. As fast as the child’s legs could move, she rushed toward the door.

“How badly are you hurt, Arthur?” she asked.

“Not bad,” he replied.

Miss Oliver quickly contradicted him. “He cannot stand on his right leg. He twisted his knee or his ankle or both.”

Carrie shot him a frown before turning to the nurse. “Twisted? Not broken?”

“I cannot say for sure, my lady. Without removing his boot, it is impossible to tell, and he wisely has kept it on.”

“Raymond, help me get him into the cart. I have alerted Mr. Hockbridge. He should be at Cothaire by the time we arrive.”

Arthur was not given a chance to protest that if he had a chance to sit quietly, he would be fine. His brother led him to the cart and, with the driver’s help, lifted him in the rear. Everything went black, and his head spun. He would not faint like a simpering girl! He fought until he could see again, and discovered he was lying on his back. He almost cried out when the cart bounced. Had someone climbed in?

“Fine. I am fine,” he muttered when Carrie asked how he fared.

“So I see! If you had any less color, you would be dead.”

He opened his eyes and then closed them when he saw the alarm on his sister’s face as she leaned over the side of the cart. She might tease him, but she could not hide how worried she was. He wanted to reassure her that he would be as good as new in no time, but she would not believe him. He was unsure if he believed it himself. He had not felt such pain since he fell off a stone wall when he was seven and broke his arm.

“Thank you,” he heard Carrie say, a moment before something damp and warm covered his brow. “Keep it there.”

Keep it there? To whom was she talking? A breeze brushed across his face, bringing a hint of jasmine. Miss Oliver! He wanted to ask why she was with him instead of Carrie. Where were the children? He tried to open his eyes, but it was worthless. The damp cloth covered them.

“We will be leaving as soon as the driver assists your sister up,” Miss Oliver whispered.

Many words rushed through his head. Apologies for ruining her outing with the children, gratitude for how she had helped him to the parsonage, questions about how he could repair the damage he had caused by scaring the children. None of them formed on his tongue.

He sank into the darkness as the cart began moving. When he opened his eyes again, light struck them. The cloth had been removed.

“Stay still.” Miss Oliver’s voice was so soft he could barely hear her.

She must have guessed how much his head ached. Had he struck it when he fell?

“Can you sit up, my lord?” He recognized that voice, as well. It belonged to his valet, Goodwin. The young man knelt beside him in the cart. When had Miss Oliver left? Time seemed to be jumping about like a frightened rabbit.

“Yes.” Not needing his valet’s help, Arthur sat. His head spun, and the pain swelled, but he was able to climb down on his own. His valet assisted him through the curious crowd gathered by the front door. Goodwin guided him to the small drawing room where he had talked to Carrie... Could it have been just yesterday afternoon?

Mr. Hockbridge was waiting. His hair was almost white, but the doctor was close to Arthur’s age. He had a placid aura about him as he pointed to the settee. “Place him there.”

Biting back a moan, Arthur lowered himself to the cushions. He was relieved the gawkers had not followed him into the drawing room. His sister stood near the door, her arms folded in front of her and that same worried look in her eyes.

“What happened?” the doctor asked.

“I fell,” Arthur replied. Even those two words rang through his skull as if someone struck it with a sledgehammer. He put his hand to his brow and leaned his head against the settee.

The doctor sighed, then added, “You were with him?”

Arthur raised his head, astounded to see Miss Oliver beside his sister. She looked as uncomfortable as a kitten in a kennel.

She stepped into the room, holding her bonnet in front of her. “Yes, sir, I was with him.”

“What happened?”

With quiet dignity, she explained what had taken place in the cove. He appreciated that she did not embellish the tale in any way. Yes, he had saved the little boy, but he felt more like a clumsy oaf than a hero.

“Thank you, Miss Oliver,” the doctor said when she finished.

She curtsied gracefully and took her leave.

Arthur almost told his sister to call Miss Oliver back, but how could he explain such a request? He did not understand himself why having Miss Oliver near helped. Something about her kind smile offered him comfort, but he could not say how or why. Perhaps it was as simple a thing as when he thought about her, he was not worrying about how an injury would complicate his work as a courier.

Thoughts of the nurse vanished when the doctor ran his hands along Arthur’s right leg. The pain was excruciating by his knee, and he could not silence his yelp when the doctor’s fingers touched his ankle.

With a sigh, Hockbridge straightened. “There is no choice but to cut away the boot, my lord.”

“Do what you must.” His jaw worked as he surrendered himself to the doctor’s ministrations, determined he would not allow pain to halt him from his duties. Too many depended on him, and he refused to let them down.

* * *

Maris opened a cupboard door and peered inside. It was empty. Where was Bertie? It was not like him to sneak away. When the children first arrived, they often had slipped out of the nursery to sleep in Lady Susanna’s room. But it was not the middle of the night.

So where was the little boy?

She glanced at the other children, glad the baby was with Lady Caroline. If Maris asked Lulu and Molly and Gil, she might upset them further. They were on edge after what they had witnessed on the shore. Even Lulu, who usually was the leader in any mischief, was clingy and too quiet.

Bertie had been crying earlier about the loss of his little ship and the scratch he had on his left hand, his sole injury from when Lord Trelawney saved him. He had fallen asleep in a corner about a half hour ago.

Where was the little boy now?

While she searched the day nursery, Maris had sent a maid to do the same upstairs in the night nursery where the children slept. The maid had returned minutes ago without finding the missing child.

“Rachel,” she said to the maid, who usually worked in the kitchen, “I need you to stay here with the children.”

“Yes, Miss Oliver.”

“Do not let them out of your sight.”

“Yes, Miss Oliver.”

“If I am not back before their tea arrives, pour their milk and make sure they eat their meat and cheese before any cakes.”

“Yes, Miss Oliver.” Rachel waved her hands toward the door. “Go. I raised five younger sisters and brothers. I can take care of these three.”

Maris ran out of the nursery. She glanced in both directions along the upper hallway. The day’s last sunshine poured along it, highlighting everything. Even a little boy could not hide there.

She recruited each servant she passed to help in her search. If the Trelawneys learned that Bertie was missing, she might be dismissed, but she could not worry about that. Not when Bertie had vanished.

Horrible thoughts filled her mind. What if the person who had set the children adrift had come to Cothaire and snatched Bertie? She could not imagine a reason why someone would do that, but she also could not guess why anyone had abandoned them in an unstable boat.

She faltered when she reached the wing where the family’s private rooms were. She hesitated, not sure she should venture in that direction. But Bertie could be anywhere. If the family saw her, she would be honest about what she was doing there. However, she would rather not have them learn about Bertie’s disappearance until he was safely in the nursery.

Even so, Maris tiptoed along the corridor, barely noticing the plaster friezes and the portraits on the light yellow walls that seemed to glow in the day’s last light. Most of the doors were closed, and she would have to obtain permission from the butler to knock on them. She needed to find Baricoat straightaway, because she was wasting time wandering the hallways.

A faint click came from farther along the corridor. A door opening? A shadow shifted. A short shadow! Was that Bertie slipping into a room? If so, she must collect him before he could disrupt anyone in it.

She ran down the hallway to the door where the shadow had been. It was slightly ajar. She raised her hand to knock, then halted. If she startled Bertie and he was examining the possessions inside, something could get broken, and he could be hurt.

Slowly she edged the door back, holding her breath when the latch made that soft sound again. She expected a demand for her to explain why she was entering the room without announcing herself or to have Bertie run into her as he rushed out.

Neither happened.

She swung the door wider. Beyond it, a large room was draped in shadows. Furniture was arranged in front of an ornately carved hearth and near a window that rose almost fifteen feet to the coffered ceiling. No light but the fading sunshine challenged the shadows concealing the subjects of the paintings hanging in neat precision.

Scanning the room, she saw no one. Perhaps she had picked the wrong door, or her ears had misled her. She began to draw the door closed, then froze, her hand clasped over her mouth to halt her gasp.

Bertie!

The little boy was on the far side of the room next to a chair beside the window. And he was not alone. Lord Trelawney sat in the chair, his right foot propped on a low stool. A blanket over his lap hid any bandages Mr. Hockbridge might have used. His head tilted to one side, and she wondered if he was asleep.

Bertie poked Lord Trelawney’s arm. “Are you really a bear?”

The viscount’s head snapped up. When he shifted, he moaned.

The little boy jumped. “No eat Bertie, bear!”

Maris rushed forward and grabbed Bertie’s hand. She kept her eyes averted as she said, “I am sorry he disturbed you, my lord. Bertie, we need to let Lord Trelawney rest.”

“Is he a bear?” the little boy asked, planting his feet firmly against the floor. He looked at the viscount, then at her. “Is he really a bear?”

“Bertie—”

She was shocked when Lord Trelawney laughed and said, “The boy deserves an answer. Yes, Bertie, I am a bear.”

“Oh!” His eyes nearly popped from his face as he scurried to hide behind her.