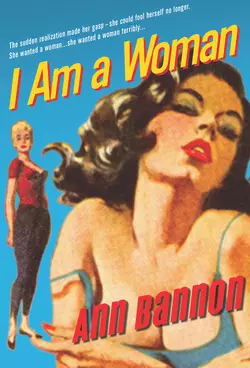

I Am A Woman

Ann Bannon

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerThe sudden realization made her gasp—she could fool herself no longer. She wanted a woman…she wanted a woman terribly…Revered as the “Queen of Lesbian Pulp” for her landmark novels of the 1950s, Ann Bannon defined lesbian fiction for the pre-Stonewall generation. I Am a Woman finds sorority sister Laura Landon leaving college heartbreak behind and embracing Greenwich Village’s lesbian bohemia. This edition includes a new introduction by the author.

I Am a Woman

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u48c28d07-c367-5b7d-b577-de755def7a21)

Title Page (#u710aae35-9575-52b9-8c75-4eb97d04d8be)

Introduction (#u796cb957-aef9-585f-b4de-4a45b2e0aaab)

Chapter One (#u533801f2-4c15-5682-acd1-fa042d59e8fa)

Chapter Two (#ud1df1c00-3f5d-5aac-be5c-d8b3b63c9810)

Chapter Three (#ubaa28533-923a-5997-83b2-fb039d9ec1b3)

Chapter Four (#u1c7c9836-6815-5320-8679-5809d4ef4219)

Chapter Five (#u8f3a7357-1fd1-5bd4-97b1-491c00f195f1)

Chapter Six (#uebcd2c88-c6b6-57ee-99c1-14ae787d4a5c)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_384195e4-d86c-51e3-89e7-bd46deb30703)

Many years ago, when this book was in its final creative stages, I had a lucky invitation to come to New York and finish it in the home of friends of friends. They were young career women, living in a very small apartment in a very old building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, near Columbia University. Luckier still, they were on the top floor, and in the hallway outside their front door stood a dubious flight of stairs that took one to the roof. There I repaired when I got stuck, or the typewriter fought back, or the coffee ran out, and gazed out at marvelous Manhattan. I especially liked going up there after dark, when the great city was spread out like a carpet of sparklers, brilliant with promise. I had just invented Beebo Brinker for this book, and with the intensity of youth, I imagined her real-life counterpart out there somewhere, down in the Village going about her business, while I, on my roof, was trying to capture her story. I spent a fair amount of time leaning on the crumbly old parapets, staring deep into the lights and wondering if there were a real Beebo on this planet. If there were, would I ever meet her? Would she be like the woman I had contrived out of sheer need so she would at least exist somewhere in the world, even if only in the pages of my book? Was there anybody like her anywhere? Big, bold, handsome, the quintessential 1950s buccaneer butch, she was a heller and I adored her.

Not once did it occur to me to wonder if other people would ever know or care about Beebo Brinker. Not once did I ask myself if other women would fall under her spell, if readers would be amused and engaged by her, if she would develop a life of her own that would carry her across the decades until I would find myself sharing her with the rest of the world. What I wanted to know was, Would she be there for me, more real than reality? Would she rescue me from the frustration and isolation of a difficult marriage, from the impatience to be my own person before circumstances made it possible, from all the personal needs deferred in the interests of cherishing my children and finding my way in this life? It was a lot to dump on a fictional character. But she was my creature, my fantasy—and once conceived, she stood up and, with her broad shoulders, helped me lift my burdens.

Up there on that long-ago rooftop, I didn’t foresee Beebo’s future, but I did try to glimpse my own. Looking out at all those bright electric blooms spread at my feet, I pondered, If each one were a reader, how many would remember the name of Ann Bannon? Would I ever come back to Manhattan some day to acclaim? Reluctantly I acknowledged the realities: I was writing paperback pulp fiction. The Beatles had yet to glamorize the “Paperback Writer.” The stories were ephemeral; even the physical material of the books was so fragile that it hardly survived a single reading. The glue dried and cracked, the pages fell out, the paper yellowed after mere months, and the ink ate right through it anyway. The covers shouted “Sleaze!” The critics ignored the books in droves, and “serious” writers were going to the hardback publishers. Of course, we did have readers. People were grabbing the pulps off drugstore shelves and bus station kiosks, and reading them almost in a gulp. But then they tossed them in trash cans and forgot them. Given this precarious bit of fleeting notoriety, I had not yet even mustered the courage to acknowledge my authorship to friends and family, much less to the public. No, there was no immortality here for Ann Bannon.

So I worked on I Am a Woman under no illusions about the prospects for enduring fame. That I am sitting down to share this with my readers forty-five years and five editions later is a true astonishment. But the perdurable appeal of the butch-femme dichotomy is not. It has, however, undergone some interesting changes.

When I was writing I Am a Woman, the unquestioned role choices open to lesbians were two: butch or femme. As Robin Tyler has observed, even if you weren’t sure which one you were, you wanted to be butch, because they didn’t have to do the dishes. Well, maybe it wasn’t that simple for everyone, but women generally were not nearly as experimental with those roles as they later became. Butches were strong, tough, heroic, romantic. They fought battles in back alleys over femmes and were quite capable of ruling the roost. The femmes, by contrast, could be more girly; some were, in a way, early examples of “lipstick lesbians.” They might appear seductive, compliant, even pretty. It was almost a mirror image of mainstream society: the guy-gals and the gal-gals. It was exciting, sexy, and dramatic. But it was also confining, and as the Women’s Movement unfolded in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it began to seem rigid and outdated. This was no way to run a romantic partnership, with one member always on top, one always on the bottom.

As so often happens when the pendulum swings, it swings the old ways right out of the ballpark. The butch-femme dichotomy was rejected altogether for a while, replaced with more egalitarian liaisons. But it always exerted a tug on the heart, propelled by the sheer charisma of the archetypal bulldyke: independent, sensual, provocative, and more than a little dangerous. Today, among young women, it seems to have a place again, as long as it is recognized as a choice. But when Laura met Beebo in that lesbian bar called The Cellar all those years ago, both women were already locked into the paradigm. Laura was feminine in the traditional way. Her defenses, her fear of emotional entanglement, quickly melted under the laser of Beebo’s sexual focus. And on her side, Beebo was intrigued by Laura’s beguiling femaleness.

I knew of no other way to write about them. Interestingly, I had tried other things. After Odd Girl Out, my first book, was published, I completed about a hundred pages of what was to be the second book for Fawcett Publications. They were the publishers of the Gold Medal Series, under whose imprint all my books were originally published. The editor, Dick Carroll, saw those pages and hated them. I was trying to “go straight,” thinking it would be easier to face friends and family as an author with at least one conventional romance under my writer’s belt. But Dick discerned at once that, whatever the merits of the plot, I didn’t even like my characters; it was not possible to care how their lives turned out. They did not, as good characters must, talk to me at all.

Once again, he told me what he had told me at the beginning, when I was trying to bring Odd Girl Out to life: “Go back to the people you love and breathe some life into them.” Thus was born the idea of developing a series and making some of the characters ongoing. I had left Beth behind in the first book to marry the college man who loved her. But I had put Laura on the train out of her college town with vague aspirations for a new life somewhere where she could be who she really was. After a blow-up with her difficult father, Merrill Landon, she decamped for New York. But whom would she meet there and what would she do?

I had been reading everything I could get my hands on in the two years or so between Odd Girl Out and I Am a Woman, trying to encompass the whole wonderful, alarming, irresistible idea of women together. I had learned the word lesbian. I had learned about butches and femmes. In travel books, I had discovered that mythical hamlet, Manhattan’s own Brigadoon, Greenwich Village. I was thoroughly enchanted. But something was missing: I had Laura, my heroine, but I was lacking a hero. The idea of one had been forming out of the mists in my mind during those two years. But it would take the perfect name to bring her to life.

Before that could happen, I had to do some “field work” and get to know my chosen territory. Living first in Philadelphia, where it was easy to get to New York, and later in Southern California, where it was not, I nevertheless made my authorial pilgrimages to Greenwich Village. With the help of friends, most notably Marijane Meaker and Sandra Scoppetone, wonderful writers themselves, I went exploring and found the haunts of Beebo Brinker: the little brownstones, the specialty shops, the crooked streets, and the wonderful, slightly trashy, and wholly mesmerizing women’s bars, replete with their full complement of admiring “johns,” tucked into the nooks of the Village.

By the time the Naiad editions were settling into middle age, somewhere in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I began to realize how many women had taken Beebo and Laura to their hearts. In the most unexpected places, I found references to them: in a poem by Joan Nestle, an essay of Kate Millett’s, Audre Lorde’s autobiography; in the wrenching life story of Cheryl Crane, Lana Turner’s daughter; in college courses, master’s theses, articles both scholarly and popular; and ultimately, in communications from women and even some men readers from many parts of the globe. It leaves me wondering what sort of stories I would have produced in the ‘50s and ‘60s, had I known then that my work, seemingly so safe from formal scrutiny, would be discussed and analyzed by future generations. The writing might have been better, but it certainly would have been more guarded and self-conscious.

The same critical scorn that deemed the work of us paperback writers unworthy of attention had also seemed to guarantee us privacy, the chance to explore and experiment, to say the unsayable, and to fade away peacefully from the publishing scene when the paperbacks finished their popular run. But some of us didn’t fade. After all these years, it is a rare blessing to have the public’s attention and support, but a mixed blessing all the same, just because of the disconcerting attention. There are times when I wish I had done enough living back then, when I was doing so much writing, to justify my grand generalizations, my cocksure assertions, my pronouncements on life and love. I was awfully damn young. But maybe it’s just as well that I didn’t have the advantage of maturity to temper Beebo’s outbursts and Laura’s emotional extremes. After all, that’s how it feels and goes down when you’re young.

So here are Beebo and Laura meeting for the first time. Where did the characters come from? The idea for Laura was based on my friendship with a sorority sister during my undergraduate days. She was two years younger than I and had many of the personality traits that make Laura both lovable and exasperating: shyness, lack of self-confidence, and hypersensitivity, but also warmth, sweetness of character, and, once she trusted you, a staunch friendship. She was slightly taller than average, with bright Scandinavian blonde hair and an engaging smile. After we got to be friends, she confided in me about her troubles with her tough-minded and abrupt father, who sounded to me like a man insensitive in reverse proportion to his daughter’s delicacy of feeling. The days when his letters arrived were downers for her, and they gave me a sort of scaffolding on which to embroider stories about her interior life. I recognized in “Laura” some of my own shaky sense of self. But unlike me, she rarely dated, seeming content to stay home most weekends and to shine academically. Whether or not she felt stirrings of romantic affection for women, I will never know, although I have my sympathetic suspicions. But I remember her as a sweetheart, with a shy warmth, and a prettiness and appeal she didn’t recognize in herself.

Beebo was another story. She was my own unrealized romantic phantom. There was another college friend, it is only fair to concede, who gave me the physical prototype. She was taller than the rest of us and strikingly handsome, with a crop of wavy, dark-blonde hair and an irresistible smile. Her nickname was one of those too-cute tomboy variations on a boy’s name. She hated it and made us promise never to use it, but her formal name didn’t seem to suit her. I remember running into her in the dorm bathroom—one of those gray marble affairs with rows of icy washbowls and green toilet stalls—in her skivvies, and trying not to admire her unduly. I think I made her a little squirmy, and she did seem to be in love with her serious beau, whom she married upon graduation. Well, we win a few and lose a few.

Actually, I didn’t quite know in that early period in my life which glamorous options to hang on the bare architecture of my fantasy hero. I just thought she needed to look like “Tommie” and to have the “heart and stomach of a king,” to quote Elizabeth I. It took me a few trips to Greenwich Village, and the reading of some of the then-current pulp paperbacks, to begin to recognize the qualities she required and to flesh them out. By that time, I was into the planning for this book and ruminating hard about my characters.

And so we come back to the roof of that Upper West Side apartment, looking down on the lights of the city. One night, staring across the twinkling horizon and seeing the character in my mind’s eye, I thought for the thousandth time, “If I could just find a name for her, she would come into focus for me.” For whatever blessed reason, it was at that moment that the childhood nickname of an old friend floated back into my mind: Beebo. I seized upon it and captured my Beebo whole, intact, entire. Never again was I the same, once Beebo began to breathe. The Beebo Brinker Chronicles were off and running, and so was their author. Thus it was that Beebo met Laura, and they began their passionate but rocky odyssey.

There is one other character whose genesis deserves attention for a moment. He is Jack Mann, that cynical, witty, sometimes prickly, but quite lovable gay man who makes his initial bow in this novel. He is shamelessly plucked, right down to his hair and fingernails, from an old hometown friend whom I met through my first serious beau—a “Jack,” too, but with a different last name. The original Jack, probably five or six years older than I, loved traditional jazz, and in my family, it was played a lot. My stepfather was a superb jazz piano player, and my mother, a one-woman cheering section. The rest of us were young, feisty, and crazy about the music, which was undergoing a revival of interest in the ‘40s and ‘50s. We worshiped Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Sidney Bechet, Muggsy Spanier, and many less well known but excellent musicians playing in the genre. A lot of them came through the Chicago area, where we lived, and our informal weekend jam sessions became well enough recognized to draw some of them out to our suburban bungalow on an occasional Saturday night. We hosted Lil Hardin Armstrong (Louis’s first wife and a great jazz pianist herself), Johnny and Baby Dodds (clarinet and drum players par excellence), and others. Jack just gobbled it up. He would settle into an old easy chair in the living room, legs propped up on a hassock and cigarette in mouth, and drum with his fingers on the chair arms. I can’t count the beers that disappeared on such an evening, but there are ancient tapes of the music, and it was nothing to apologize for.

The original Jack was always a treat to have in our company. My little brothers adored him, but they didn’t learn his name on the first visit. There were so many young musicians around on weekends that we had a standing joke that they were all uncles: Uncle Bob, Uncle Bill, Uncle Harry. So Jack, on his first visit, was greeted with, “Here comes Uncle Somebody.” It stuck, even after they mastered his name. He had a funny take on life—ironic, droll, and rather unsparing—and he would sit in that chair and shoot zingers at us between musical numbers. We all loved him. I noticed, however, that unlike the other young men who dropped by so often, he never brought a date with him. Whether or not he was gay is another of those mysteries I never cracked.

I began to lose track of Jack only after I went away to college, when I was able to get news about him only occasionally from the hometown boy I was dating. Finally, shortly after my college graduation, I thought to ask the now-former beau, “Where is Jack these days?” The answer was not reassuring. He had gone to work for the CIA and had been sent to Ho Chi Minh City, then known as Saigon. He had, in fact, made several trips there, and finally, he did not come back from one of those trips. By now, it was the early 1960s, an increasingly dangerous time to be in Southeast Asia. No one from those heedless, happy times in my hometown seems to know how his story ended. It is a source of sorrow to me that he drifted out of my life without leaving a trace—except, I venture to hope, in his incarnation in these stories as Jack Mann, the good-hearted, perpetually frustrated gay man who could never resist taking in lost kids and helping them find jobs and make their way in the Big City. Alas, they always made their way to some other lover and left Jack in the lurch. But he never lost hope, nor do I, that someday, somehow, “Uncle Somebody” will come strolling up the front walk, cracking wise and charming us all.

And oh, the drinking! And oh, the smoking! You follow it all in the narrative, and you really wonder how any of us survived those days. And the truth is, there were casualties. But consider the reason. Where else were we to go? What women’s bookstores, what culture clubs, what social safety nets were there for women then? How did they even find one another? They resorted to the one social institution that represented a haven, a place to meet old friends and find new ones, a place to relax and be oneself—a place, in other words, that served an indispensable function in a perilous era. That some of the women from the ‘50s and ‘60s were sacrificed to the flow of liquor and smoke, lamentable though it is, is hardly to be wondered at. The options were so few and the need was so great that the bars were always crowded. Still, those women must be remembered with affection and gratitude; they were pioneers, too, and helped to build the foundation of sisterhood we all stand on today.

Last, the title. I had wanted to call the novel Strangers in This World. But Dick Carroll wouldn’t go for it. I suspect he knew much better than I that my title would not work as a code phrase to alert potential readers to its lesbian content. He was a canny marketer and used every available strategy to promote the books. Indeed, he had come up with the rather clever Odd Girl Out as the title for my first book. So what did he invent for this one? I Am a Woman. I always thought it was a vacuous sort of name for a book. It has no real referent: Who, for example, is the “I”? The book is not a first-person narrative. The title makes sense only as part of a longer sentence followed by a question, which had to be reproduced in its entirety on the cover of the original edition: I Am a Woman in Love with a Woman. Must Society Reject Me? What a mouthful of angst. I thought it was unwieldy and irrelevant to the story line; it could have been slapped on virtually any lesbian pulp paperback. It had no special connection to this one. But I Am a Woman the book became and remains. And in that incarnation, it sold like the proverbial hotcakes in 1959. So Dick Carroll was right and I was wrong. It still seems unappealing to me, an almost nameless name. On the other hand, this book, vague title and all, is one of my favorites in the series.

And so the saga of Laura and Beebo begins here, with its somewhat old-fashioned language and a few dated attitudes, but with a fresh and youthful joy in love and lust and all hopeful possibilities that defies the passage of time. It’s no great secret that the white-hot romance between them didn’t last a lifetime. But that’s only the first lifetime. They are still young at heart, still handsome women, still kicking. Who knows what the future holds? My own life is proof positive that none of us knows or perhaps would want to. All the good things seem to come upon us unawares. I leave all doors open.

Ann Bannon

Sacramento, California

December 2001

Chapter One (#ulink_48979a6c-c58e-58d7-92db-995cfa7c2a49)

Tell your father to go to hell. Try it. It’s a rotten hard thing to do, even if he deserves it. Merrill Landon did. He was an out-and-out bastard, but like most of the breed, he didn’t know it. He said he was a good father: sensible, firm, and just. He said everything he did was for Laura’s own good. He took her opposition for a sign that he was right, and the more she opposed him, the righter he swore he was.

But he was a bastard. Laura could have told you that. But she couldn’t tell him, because he was her father. That was why she ran out on him. Left him high, dry, and sputtering in his plush Chicago apartment with only his job to console him. And never told him where she went. Never told him why.

Never told him of the angry agony of her nights, spent torching for a love gone wrong. Never mentioned his straight-laced bitter version of fatherly affection that hurt her more than his fits of temper. He never kissed her. He never touched her. He only told her, “No, Laura,” and “You’re wrong, as usual,” and “Can’t you do it right for once?”

She had taken it all her life, but it was the worst the year after she left school. It was a year of confinement in luxury, of tightly controlled resentment, of soul-searching. And one rainy night when he was out at a press dinner, she packed a small bag and went to Union Station. She bought a ticket to New York City. She could never be free from herself, but she could be free from her father, and at the moment that mattered the most.

So she rode out of the big city, wet and cold with its January gloss, and left behind Merrill Landon, her father. The man in her life. The only man in her life. The only man she ever seriously tried to love.

All she wanted from New York was a job, a place to live, a friend or two. As long as she won them herself, without her father’s help, she would be happy. Much happier than when she had been surrounded with comfortable leather chairs, sheathed in sleek fine clothes, smelling like an expensive rose.

In school Laura had studied journalism. She did it to avoid a showdown with Merrill Landon. He had always taken it for granted that she would follow his profession, just as if she were a doting son anxious to imitate a successful father. She accepted his tyranny quietly, but with a corrosive resentment that he was unaware of. There were times when she hated him so actively for making a slave of her that he saw it and said, “Laura, for Chrissake, don’t pout at me! Snap out of it. Act your age.”

Laura was more afraid of loving Landon than leaving him. She was afraid the yearning in her would flare someday when he gave her one of his rare smiles. When he said, “Klein says you’re learning fast. Good girl.” And her knees went weak. But he saved her by quickly adding with embarrassed sarcasm, “But you messed up the water tower assignment. Jesus, I can never count on you, can I?”

When things became intolerable she left him at last with no showdown at all. She had considered going in to tell him about it. Walking into the library where he was working, where she was expressly forbidden to go in the evenings, and saying, “Father, I’m leaving you. I’m going to New York. I can’t stand it here anymore.”

He would have been brilliantly sarcastic. He would have described her to herself in terms so exaggerated that she would see herself as a grotesque mistake of nature, a freak in a fun-house mirror. He was not above such abuse. He had done it to her a few times before. Once when she was very young and hadn’t learned to tiptoe around his temper yet, and once when she quit school.

Not all his threats and tantrums could send her back to school, however. There was a ghost lurking there that Laura could never face, that Landon knew nothing about. He was forced to let her stay at home, but he committed her to journalism at once, and made her work on his paper with one of his assistants.

Even Laura was surprised when she was able to resist him about returning to school. She wouldn’t have thought she could stick it out. Especially when he roared at her, “Why? Why! Why! Why! Answer me, you stubborn little bitch!” And smashed an ashtray at her feet.

She did not, could not, tell him why. It took all her courage to admit it even to herself. She simply said, “I won’t go back, Father.”

“Why!”

“I won’t.”

“Why?” It was menacing this time.

“I won’t go back.”

In the end he swore at her and hurt her with the same ugly irrelevant argument he always used when she resisted him. “You know why you’re alive today, don’t you? Because I saved you! I dragged you out of the water and let your mother drown. And your brother. I could only save one, and it was you I saved! God, what a mistake. My son. My wife!” And he would turn away, groaning.

“You weren’t trying to save me, Father,” she said once.

“You just grabbed the nearest one and swam for shore. You screamed at Mother to save Rod and then you dragged me to shore. It’s a miracle you saved even me. You see, I remember it too. I remember it very well.”

He turned a pale furious face to her. “You dare to tell me what you remember! You silly little white-faced girl? You don’t remember anything? Don’t tell me what you remember!”

So she chose a night when he was out and left him without a word, at the start of an unfriendly January, and came to New York. Her first thought was to try to get work on one of the giant dailies. With her experience, surely they could find something for her. But then she realized her father was too well known in journalism circles. She hated the thought of his finding her. He had struck her more than once, and his anger with her sometimes reached such heights that she trembled in terror, expecting him to brutalize her. But it never went that far.

No, newspapers were out. Magazines were out. It would have to be something completely divorced from the world of journalism. She studied the want-ads for weeks. She tried to land a job as a receptionist with a foreign airline, but her French was too poor.

Then, after about two weeks, she found a small ad for a replacement secretary to a prominent radiologist, someone with experience preferred. It appealed to her, without her exactly knowing why. She didn’t really suppose she had much of a chance of getting it and it was silly to try. Who wanted a temporary job? Most girls were supposed to want security. But Laura wasn’t like most girls. She was like damn few girls, in fact. She was a loner: strange, dream-ridden, mildly neurotic, curiously interesting, like somebody who has a secret.

The next morning she was in the office of Dr. Hollingsworth, talking to his secretary. The secretary, a tremendously tall girl with big bones, a friendly face, and a sort of uncomfortable femininity, liked her right away.

“I’m Jean Bergman,” she said. “Come on in and sit down. Dr. Hollingsworth isn’t here yet; he gets in at nine.”

Laura introduced herself and said she’d like to have the job. She was a hard worker. Jean was disposed to believe her on a hunch. It was one of those lucky breaks.

“I’ve talked to some other girls,” she said, “but nobody seems to have had any experience. The girls with training want permanent jobs. So I guess I’ll just have to find a bright beginner.”

Laura smiled at her. She spoke as if it was settled. “The job will last till June first, Laura,” Jean went on. “I’ll be gone two months. We’ll spend the time till then teaching you the routine. Sarah will be coming in in a minute—she’s the other secretary. There’ll be plenty for the three of us.” She paused, eying Laura critically. “Well? Do you think you’d like a crack at it?”

“Yes, I would.” Laura felt her heart lighten.

“Okay.” Jean smiled. “I’m a trusting soul. You strike me as the efficient type. Of course, I’ll have to introduce you to Dr. Hollingsworth. You understand. Now don’t let me down, Laura.”

“I won’t. Thanks, Jean.”

“You might make yourself indispensable, you know,” Jean said. “I mean, they really need three girls around here. If they like you well enough—well, maybe they’ll keep you on in June. It’s just a chance; don’t count on it.”

Laura felt really worthwhile for the first time since she left home. She had never considered turning back, but there had been moments when the barren want-ads discouraged her and the wet biting weather dragged her spirits down. Now, the sun was shining through the rain.

It turned out to be a fine office to work in. Doctors have a crazy sense of humor and they are often tolerant. Dr. Hollingsworth was small and quiet, quite dignified, but tender-hearted. He had two young assistants, Dr. Carstens and Dr. Hagstrom. They were both fresh from medical school—pleasant young men. Carstens was married, but with a wildly roving eye. Every female patient fascinated him, even if he saw no more than her lungs. Hagstrom had a permanent girlfriend named Rosie with whom he conducted endless conversations on the phone. Both were devoted to Dr. Hollingsworth and considered themselves lucky to be with him.

Laura fell into the routine rapidly. She was much slower than the other girls at translating the mumbo-jumbo on the dictaphone at first. She spent nearly half the time looking up terms in the medical dictionary and the rest beating the typewriter.

The problem of finding a place to live before the hotel bills broke her was urgent. She discovered in a hurry, like most newcomers to New York, that it was a real struggle to find a decent apartment at a decent price. She asked Jean about it.

“I’m stuck,” she said. “Where do people live in this town?”

“What’s the matter with me?” Jean said. “I should have asked you if you had a place. I know a girl who’s looking for a roommate. The one she had just got hitched. I’ll call her.”

Later she told Laura, “I talked to her. She says a couple of gals have already asked her, but to call if you want to.

“She hasn’t made up her mind yet. She’s a doll, you’ll like her. Here’s her number.”

“What’s her name?”

“Marcie Proffitt. Mrs. Proffitt.” She laughed at Laura’s consternation. “She’s divorced,” she said.

Laura called at once.

“I’m at West End and a hundred and first,” Marcie said when Laura got her. Her voice was low and appealing. Laura hoped she looked like she sounded. “The penthouse,” Marcie said. “It’s not locked. You have to walk up the last flight.”

“A penthouse?” Laura said, taken aback. “Jean said—”

“It’s not as fancy as it sounds,” Marcie laughed. “In fact it’s falling apart. That’s how I can afford it. But it has a wonderful view. Come over tonight. I’ll give you some dinner. I may be late, though, so I’ll leave a key for you under the doormat.”

“Thanks, Marcie, I’d like to.” Laura wondered, when she hung up, if Marcie’s hospitality was always so impulsive.

It was dark and getting windy when Laura got off the subway at 99th Street. She walked the two blocks up Broadway to 101st, holding her coat collar close around her throat.

The apartment building was a block off Broadway, up a hill at the corner of West End Avenue. It had been a chic address once, some years ago, when West End was an exclusive neighborhood. But it was deteriorating now, quietly, almost inconspicuously, slipping into the hands of ordinary people—families with lots of kids and not much money, students, working girls. And the haut monde was quietly slipping out and heading for the other side of town.

Laura entered the vestibule. It looked like the reception hall in a medieval fort. The only light came from a small bare bulb on a desk in one corner. The whole hall was full of heavy shadows.

Laura found the elevator tucked into a corner and pressed the button. She swung slowly around on her heels to look at the hall while she waited. It gave her the shivers.

She climbed into the elevator with misgivings. It looked well used and little cleaned. There was a paper sticker plastered on the wall above the button panel saying that it had passed inspection until June of that year. Laura looked it up and down and wondered if it would last till June. She reached the twelfth and last floor and walked out into a hall. To the right of the elevator she found a pair of swinging doors, and beyond them a steel staircase. She climbed the stairs, her heels ringing, and found herself in a short dark hall with two doors in it: one to the penthouse, one to the roof. Laura went out on the roof for a look.

She walked over the red tiling toward a stone griffin carved on the railing and looked over it to the city. Below her, around her on all sides, sparkled New York. It honked and shouted down there, it murmured and sighed, it blinked and glittered like a gorgeous whore waiting to be conquered. Laura breathed deeply and smiled secretly at it. She could live with a dank front hall and patched-up elevator for a view like this.

It was ten minutes before she went into the dark corridor again and found the penthouse door. She rang twice, and when there was no answer she fumbled in the darkness for the key under the mat and unlocked the door. It opened into an unlit living room. Laura went in, shut the door behind her, and stumbled around looking for a light switch. She knocked something off a table and heard it break before she discovered a lamp in a far corner and pulled the cord.

The room was small and furnished with bamboo furniture—a couch, an easy chair, a round cocktail table. There was a console radio against one wall, and books were lying around on the floor and furniture. There were a couple of loaded ashtrays and one lay shattered on the floor—Laura’s fault.

Laura found the switch in the kitchen. It was long and narrow, painted a garish yellow. Beyond that was the bedroom, with two beds and two dressers jammed into it, and some shoes and underwear scattered around. It was bright blue, with two big windows opening onto the roof. The bathroom was enormous, almost as big as the bedroom, and the same noisy yellow as the kitchen. All the pipes were exposed and the plumbing looked as if it were full of bugs.

Laura walked back into the living room and sat down stiffly. She began to have serious misgivings. This was no place for a civilized girl to live. Surely in this tremendous city there was an apartment for a girl that didn’t have an astronomical rent. And where she could eat in private out of cans.

Suddenly the door burst open and Marcie came in. And Laura forgot her discomfort.

Marcie smiled. “I’m Marcie. Hi.”

Laura cursed the shyness that tied knots in her tongue.

“How do you like this crazy little palace?” Marcie said, gesturing grandly around her.

“It’s very nice.”

Marcie laughed, and Laura was struck with the sweet perfection of her features. Her lips were full and finely balanced; her nose was of medium length and dainty. Hair with a true gold hue that no peroxide can imitate framed her face and hung nearly to her shoulders. She had the lucky black lashes and eyebrows that sometimes happen to blondes, and high color in her cheeks. She was, in short, a lovely looking girl. Laura smiled at her.

“It’s a hole,” said Marcie. “Don’t be polite. The rent is one thirty a month.”

Laura gasped.

“I know. It sounds awful. But that’s only sixty-five apiece. And it includes maid service—so-called. The maid doesn’t pick up a damn thing. Did you see the rest of the place?”

Laura nodded.

“Discouraged?”

“A little.” Laura followed Marcie awkwardly into the kitchen.

“You’d better know the worst right off,” Marcie went on. “Three other girls have called wanting to share this place with me.” Laura’s incredulous face made her laugh. “It’s not that the place is irresistible,” she explained. “It’s just that apartments are hard to get in this town. Sit down, Laura.” Laura obeyed her, finding a chair at the kitchen table while Marcie fussed at the stove. “Have you been here long?”

“Three weeks.”

“Where did you come from?”

“Chicago.”

“Oh, that place. I was there once with Burr. He was my husband.”

“Oh,” Laura said softly, almost sympathetically, as if Marcie had announced his demise.

“Well, don’t put on a long face,” Marcie said with a sudden laugh. “He’s divorced, not dead. It was final last November.” Her face became serious again and she gave Laura a plate of vegetables and hamburger. “He’s very nice to know,” Marcie mused. “But hell to live with. Laura, do you cook?”

“I can’t boil water.”

“Well, I can do that much.”

Marcie lapsed into silence then, her burst of charming vitality spent. She ate quietly, as if unaware of Laura’s presence, gazing at the tablecloth and forking her food up mechanically. She had withdrawn suddenly and soundlessly into a private corner where fatigue and secret thoughts absorbed her.

Laura felt more awkward than ever. She was afraid to interrupt Marcie’s reverie, but like all shy people she was convinced that if you can just keep the other person talking, everything will be all right. It was an urge she couldn’t resist After a few false starts she said, “Have you been in New York long, Marcie?”

Marcie looked at her, mildly surprised to find her still there. “Yes. Since we were married.” She spoke absently, turning to her plate.

“When was that?”

“Three years ago.” She came suddenly back to the present. “Laura, did you ever love a man and hate him at the same time?”

Laura was nonplussed. This was more than she counted on. “Well—I don’t know exactly.” She wasn’t sure if she had ever loved Merrill Landon. She knew well enough how she hated him.

“I shouldn’t throw my problems in your face like that, before you get your dinner down,” Marcie smiled. She reached out and gave Laura’s arm a pat that made Laura jump a little. “It’s just that that damn character proposed to me again today. I don’t know what to do with him. I thought maybe you could give me some advice. Have you ever been married?”

“Me? No,” said Laura emphatically, as if it were a slightly lewd suggestion. “Who is ‘that character’?”

“Burr. My ex-husband.”

“He wants to marry you again?” It seemed unnatural to Laura. If the marriage was legally over, physically over, emotionally over, why beat the carcass?

“Yes. The fool.” Marcie smiled ruefully. “He’s a very persuasive fool, though.”

Marcie was one of those people with the rare gift of intimacy. You knew her a few minutes, an hour, a couple of days, and you discovered to your surprise that you felt close to her. It wasn’t the personal revelations she couldn’t help making, as much as it was her look, her questions that asked for Laura’s help. Laura felt curiously like an expert on marital affairs, and it was so ridiculous that she smiled.

“What’s funny?” Marcie asked.

“You make me feel like Miss Lonelyhearts or something,” Laura said.

Marcie laughed. “You don’t have to give me advice, Laura, just because I ask for it. I guess you can’t anyway if you’re single. But just for the hell of it, what would you do if a decent honorable sort of ex-husband chased you like a demon and swore he’d kill you if you went out with anybody else?”

“I’d send him to a clinic.”

Marcie shook her head. “He’s healthy. If I didn’t know we’d quarrel twenty-four hours a day, I’d marry him tomorrow.” She sighed. “I almost said yes to him today. What’s the matter with me? I’m not a dope. Or am I?”

“You don’t look like one,” Laura said uncomfortably.

“Poor Laura!” Marcie laughed. “I’m embarrassing you to tears. You make a good listening post. Come on, finish your hamburger. It didn’t kill me.”

When they cleared up the dishes, Marcie turned on the tap in the sink. A thin hesitant stream of water was called up after some pitiful groaning from the pipes. Marcie kicked a pipe under the sink.

“It’s enough to drive you wild!” she exclaimed. “Some nights you have to wait around till the cows come home before there’s enough to wash anything in. Oh, here it comes!”

With a scream the pipes vomited steaming water. Marcie looked at Laura and the little smile on her face widened.

Suddenly they were laughing hilariously. Laura felt the laughter soothing and tickling her tight muscles, making her relax.

“It hates me,” Marcie said to the sink, grasping the faucets and rattling them furiously. The stream came to an abrupt halt. She turned to Laura again. “Do you think you can stand it?” she said.

“I think I can.” Laura knew now why she wanted to move in, but she was ready to ignore the reason. She would bury it, forget it. It had no place in her world any more. She would say to herself, and half believe, that she was moving in simply because apartments were hard to find; because she could pay the rent on this one; because she and Marcie were congenial. Period. “What’s your job like?” she asked Marcie casually.

“I’m supposed to be a typist-receptionist,” Marcie said. “But I could never type very well. Mr. Marquardt doesn’t care, though. He just told me to make a good impression on his customers and don’t chew gum on the job. I told him that would be a cinch, and he said, ‘You’re hired.’” She laughed. “He’s nuts. But it’s a great job. I just sit around most of the day.”

With a face like that, I’m not surprised, Laura thought. It gave her a bad feeling. Laura worked hard, she tried hard at anything she did. It was part of her nature. Either you did a thing the whole way or you didn’t do it at all. It was part of Merrill Landon’s code that had rubbed off on her. It made her a little jealous to hear this lovely girl brushing idly over a comfortable job that asked almost nothing of her. Marcie would not have understood Laura’s feelings at all.

“You’ll get along fine with Burr,” Marcie said, drying her hands on a towel. “He’s always reading something. Those are his books in there.” She waved a hand toward the living room. “He brings them over in hopes that I’ll improve my mind.” She made a face and Laura smiled at her.

“Does he come over a lot?” Laura asked.

“Yes, but don’t worry. He’s harmless. He talks like Hamlet sometimes—gloomy, I mean—but he’s nice to dogs and children. He has a parakeet, too. I always think a man who has a parakeet can’t be very vicious. Besides, I lived with him for two years, and the worst he ever did to me was spank me one time. We shouted at each other constantly, but we didn’t hit each other.”

“Sounds restful,” Laura said.

Marcie laughed and went into the bedroom. “See if you think you’ll have enough room in here,” she called to Laura, who followed her slowly. “It’s pretty crowded, but the bathroom makes up for it. We could fence it off and make an extra room of it if we wanted to.”

Laura sat down on one of the beds. “I like it fine, Marcie,” she said. “I’d like to move in. If you think we’d get along.” She looked at her lap, confused. She never said these things right. Marcie laughed good-naturedly and flopped on the bed beside Laura, on her stomach. Laura had to twist around to see her. “Oh, I can get along with anybody,” she said. “Even you. I’ll bet you’re terribly hard to get along with.”

“I don’t think so. I mean—” She never knew when she was being teased until she had put on a solemn face and felt like an ass. “I’m impossible,” she said with a smile.

“That settles it!” Marcie exclaimed, sitting up with the pillow crushed against her bosom.

Chapter Two (#ulink_cca1f55f-9fe4-5b63-94ca-6d0a928aee36)

They got along unusually well together, as the weeks passed into months. April came, and Jean left on her European tour, Laura and Sarah were alone in the office with the doctors, and Laura worked with a will to make up for what she still had to learn. With each day, each fact acquired and skill polished, the job meant more to her.

At home, there were no scenes or suspicions, such as female roommates have a talent for. Laura was quiet, shyly friendly, thoughtful. Marcie gave her a cram course in cooking, saw an occasional movie with her, and asked her how to spell things. Most of her free time was spent with Burr.

Laura liked Marcie very much. She tried to keep it that way. She was relieved, as time went on, that her friendship didn’t get complicated by stronger feelings.

I like Marcie, and that’s all, she mused to herself one time. It gave her a certain satisfaction that most women would not have understood.

As for Marcie, she was somewhat amused with Laura; with her modesty, which seemed so old-fashioned; with her shyness; with her books. But she felt a real affection for her. Laura wasn’t much for gossip, but she always listened to Marcie’s compulsive confessions. She was gentle and sympathetic. Her ideas were different, and Marcie listened to her with respect.

Laura wasn’t pretty, but at certain angles, with certain expressions, she was striking and even memorable. Not everyone saw this quality; not everyone took the trouble to study her features. But they made a curious appeal to those who did. Her face was long and slim, and her coloring pale. But her eyes were deep and cornflower blue. If Marcie had studied them she might have seen more worldly wisdom than she dreamed of in her bookish roommate.

Laura had a good grasp on what it meant to be a woman; on what it meant to live deeply, completely, even when it didn’t last; on what it meant to be a loser. And everyone must lose at least once before he can understand what it is to win.

Burr had come over the night after Laura moved in. He was of medium height but powerfully built, with a pleasant face. His brown hair was crew cut, his brown eyes sparkled zealously, like those of a man with a mission. His mission, apparently, was Marcie. He seemed to adore her; it was so plain, in fact, that it made you wonder if it was real.

He walked into the kitchen where Laura and Marcie were finishing the dishes, grabbed Marcie without a word to Laura—he didn’t even seem to see her—and kissed her passionately. Laura self-consciously wiped a dish, put it on the cupboard shelf, and started to back out of the room.

“Burr! You could have said hello!” Marcie gasped when he released her. “Laura, don’t go. This is—” But he kissed her again. This time when he let go she was mad. It was beautiful to see. Laura was exhilarated with the force of it. Marcie, who was always full of laughter, was walloping Burr with a wet dishcloth and calling him “You bastard!” Her eyes flashed, and she swiped at his face with long meticulously pointed nails. Laura headed for the bedroom, but Marcie turned and caught her.

“Oh, no!” she said, pulling Laura back. “I want you to see what I married. I want you to tell me if I wasn’t smart to get a divorce. Look at him.”

Burr, his face damp with dishwater, was gently exploring a nail-inflicted wound with one finger.

Laura tried to back out, but Burr saw her then and smiled. “Hello, Laura,” he said. “You’ll have to forgive my charming wife. She’s very emotional.”

“I’m not your wife!” Marcie flared.

Laura couldn’t help thinking it was all a joke. They both seemed to be enjoying it too much.

Burr ignored Marcie. “You’ve probably never seen this side of her,” he remarked to Laura. “I used to get it once or twice a day, like medicine. Finally drove me to divorce.” Marcie threw a towel at him and he smiled pleasantly at Laura. “But don’t let it bother you. You’ll never have to marry her, so you’ll avoid the problem.”

There was a stormy pause. “Have some coffee?” Laura said suddenly to Burr.

“I’ll fix him a highball,” Marcie sighed. “He hates coffee.”

“I don’t hate it. Why do you exaggerate, honey?”

“Well, you drink that horrible Postum crap, like all the grandfathers.”

“It’s not crap. It’s a hell of a lot better for you than coffee, I can tell you that.”

“Then why don’t you live on it, darling?”

“If I wanted sarcasm tonight, I would have gone over to Chita’s.”

“That whore!”

“I—I think I’ll turn in,” Laura said softly and hurried toward the door.

“Don’t be silly!” Marcie looked at her, chagrined. “You haven’t said two words to Burr.”

“She couldn’t say two words, honey. You’ve been talking too fast. I couldn’t either, for that matter.” He went over to Laura and led her by the hand to a chair. “Let’s talk about you,” he said. “Sit down.”

Laura felt ridiculous, but she obeyed him.

“Where’re you from?” he demanded.

“She’s from Chicago.” Marcie handed him his drink and perched on the drainboard of the sink.

“Say something from Chicago, Laura.” He grinned at her.

She shrugged and laughed, embarrassed.

“What does your old man do?”

Laura was startled to think of him. He had been out of her mind in the bustle of moving in with Marcie. “He’s a writer—a newspaperman,” she said. She looked so uncomfortable that Burr let it drop.

After a slight quiet he said, “What do you think of my girl?”

“Burr, please!” Marcie exclaimed, but he waved at her to shut up.

“You know you won’t be rooming with her for long, don’t you?” He smiled at Laura, and it looked like a warning sort of smile. It made Laura faintly queasy, as if she had already done something wrong.

Laura hated to compliment a woman. It was always hypocritical because she could never tell the truth without blushing. The more she admired a girl, the harder it was to talk about her. She began to blush. “She’s a very nice girl,” she said hesitantly.

“Say it like you mean it!” Burr said. “She’s a wonderful girl. Even if she is a shrew.”

“Damn! Stop humiliating us, Burr. You aren’t funny.”

Burr stared at Laura, until she had to say something. “We get along just fine,” she said.

“Sure. The first two days.” He laughed a little.

“Burr!” Marcie exploded. “She’s a girl, not an ornery bastard male like you.”

“Well, I hope you two will be ecstatically happy,” he said, and downed his drink.

“I won’t be talked about like this!” Marcie said. She dropped down from the drainboard and started out of the room, but Burr caught her around the waist. He was sitting next to Laura, and he buried his face in Marcie’s stomach. Marcie tried to grasp his short hair and push him back. Laura felt the old revulsion rising in her. Burr was doing nothing very shocking or immoral. He was just embracing the girl he loved, the girl who had been his wife. Laura knew that intellectually but her spirit retreated from the sight, repulsed.

“You know something, Laura?” Burr turned his head to look at her, still pressed against Marcie. “She acts like a damn virgin with me. She acts like she didn’t have any idea what it’s all about. Like we’d never been married at all, and I’d never—well, never mind what I did. She won’t let me do it anymore.”

“Burr, you’re really repulsive,” Marcie said, shaking her head at him.

“Am I?” He smiled at her.

“You know you are. Laura doesn’t want to hear about that. Do you, Laura?”

“I think I’d better get to bed,” Laura said.

“That’s a good girl,” Burr said approvingly. “Always knows when to cut out. Laura, we’re going to get along fine.”

“Don’t go, Laura!” Marcie ordered her.

Laura, halfway to the bedroom, stopped.

“Scram!” said Burr. As she shut the door behind her he added, “Sweet dreams, Laura. You’re a doll.”

Laura shut the door on them as he took Marcie, still resisting, in his arms. She walked uncertainly around the bedroom for a few minutes. It occurred to her that Burr would be grateful for the use of the bedroom, but Marcie would never forgive her for suggesting it. Laura ran a bath—it took fifteen minutes to get enough water to sit in—and sat contemplatively in it, wondering what her roommate was doing in the kitchen. She tried not to think of it. But when a thing revolted her it stuck stubbornly in her head and tormented her deeply.

Laura climbed out of the tub and dried herself, looking in the mirror as she did so. She had never liked the looks of herself very well. It still amazed her to think that this slim white body of hers, this tall, slightly awkward, firm-fleshed body, had been desirable to someone once. She studied herself. She was not remarkable. She was not lush and ripe and sweet-scented. On the contrary, she was firm and flat everywhere, with long limbs and fine bones. Her pale hair hung long over her shoulders, and bangs framed her brow.

I am certainly not beautiful, she thought consciously to herself. And yet I have been loved. I have loved.

She gazed at herself for a moment more and the ghosts of old kisses sent shivers down her limbs. Then she rubbed herself briskly with the towel and put her pajamas on.

That’s over now, she said to herself. That happened a million years ago. I’m not the same Laura anymore. I can’t—I won’t love like that again. I’ll work, I’ll read, I’ll travel. Some people aren’t made for love. Even when they find it, it’s wrong. I’m one of those.

She picked up a book she had been reading—one of Burr’s—and climbed into bed. There was a small lamp between the beds and she switched it on, drawing her knees up for a book rest. The covers formed a tent over her legs.

For a long while she sat and read about the mixups of other people, the people in the book. Then she closed it and put it on the bedside table. She turned the light off, but still she didn’t lie down. She simply sat there in the dark, listening … listening … and heard nothing. She put her head back, resting, thinking about them in the other room, hating her thoughts but unable to shake them. After a while she slept, still sitting half-upright.

Much later, muscle cramps woke her up and forced her to lie down. She noticed that the light under the kitchen door was out. She pulled the covers over her shoulders, wondering what time it was. In a moment, all was silence again.

“Laura?” It was Marcie, whispering.

Laura sat up with a start. “Yes? Marcie, are you all right?”

“I’m all right.”

“Is he gone?”

“Yes. For the time being.”

“Oh. What time is it?”

“About three.”

“You shouldn’t stay up so late. You have to go to work in the morning.”

There was a little silence.

“Laura?”

“Yes?”

“Were you ever in love?”

Laura felt a terrible wave of emotion come up in her throat. What a damnable time, what a damnable way, to ask such a question! She was defenseless against her feeling in the soft black night, with the soft voice of a lovely girl asking her, “Were you ever in love?” For a while she tried to keep her mouth clamped shut. But Marcie asked her again and she was undone.

“Were you, Laura?”

“Yes,” she whispered.

“What was it like?”

“Oh, God, Marcie—it was so long ago—it was so complicated. I don’t know what it was like.”

“Was it good?”

“It was awful.”

Marcie turned over in bed at this, raising herself on her elbows. “Wasn’t it good sometimes? Now and then?”

“Now and then—” Laura whispered, “it was paradise. But most of the time it was hell.”

“Did—did he love you? As much, I mean?”

Laura pressed her hands to her mouth, not trusting herself for a minute. Then she whispered, “No.”

“Oh, I’m sorry.” Marcie’s voice was warm with sympathy. “Men are such bastards, aren’t they?”

“Yes. They are.”

After a moment of thought Marcie said, “Burr likes you.”

“I’m glad.” She couldn’t stand to talk anymore. “Good night, Marcie.”

“Good night, Laura.” Marcie sounded a little disappointed. But she said nothing more and in a minute Laura heard her roll over and fall asleep. Laura did not sleep again that night.

Chapter Three (#ulink_1958c50c-0daf-56e8-abe1-af4923f5c773)

If Laura and Marcie went along together on greased wheels, Marcie and Burr did nothing of the kind. There was never anything real to argue about. But Burr couldn’t pick up a book or clear his throat or make a suggestion without causing a disagreement. And he was as quick to snap at his ex-wife. The only times they weren’t shouting at each other, they were kissing each other.

“You probably wonder why we keep seeing each other when we fight like this,” Marcie said to her one night.

“Do you love each other?”

“I don’t know—Yes.”

“Then I guess it doesn’t matter if you fight.”

“I hope it doesn’t drive you nuts.”

“No, not at all.” Laura wouldn’t even look up from her book. Marcie embarrassed her with these confidences. But she couldn’t go on reading. She stared at the page and waited for Marcie to continue.

Marcie couldn’t keep a secret. Things poured out of her, even intimate things, even things that belonged to her private soul and should have stayed there. Laura squirmed to hear her sometimes.

“We see each other,” Marcie went on, “because we can’t keep our hands off each other. We fight because we’re ashamed of what we want from each other. At least, I am. I guess Burr doesn’t have any shame. No, that’s not fair. I guess he’s the one who’s sure he’s in love. Sometimes I think I am, because I want to keep seeing him. And other times, I think it’s just his big broad shoulders.”

“Don’t see him for a while,” Laura said. “Or try talking less when you do. See what happens. Or do you just want to keep torturing yourself?”

“I guess I do,” said Marcie with such a disarming smile that Laura had to smile back.

“Well, it’s not my business. I can’t pass out any helpful hints,” Laura said. I won’t care about your personal life, I can’t, she thought.

Marcie laughed, walking around the room, peeling off her clothes. “Laura, you’re a funny girl,” she said. “You’re not like other girls I know.”

“I’m not?” Laura felt an old near-forgotten sick feeling come up in her chest.

“No. Other girls love to talk about things. They love to gossip. Why, I know some who would get started on Burr and keep going until they had to be gagged. But you’re different. You just sit there and read and think. Don’t you get worn out doing so much thinking?”

“What makes you think I do so much?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Don’t you?”

“Everybody thinks.”

“Not as much as you do.”

“There’s nothing wrong with it.”

“I don’t mean that. I mean—I guess I mean, why don’t you ever go out?”

“I do. I saw that musical last week.”

“I don’t mean with me. Or other girls. I mean with boys.”

Laura loathed conversations like these. She felt as if she had spent her whole life justifying herself to somebody—mostly Merrill Landon, but others too. As if everything she did or didn’t do had to be inspected and approved. If it wasn’t approved it stuck in her craw somewhere and came up now and then to make her sick. “I’m new in New York,” she said. “I don’t know anyone yet.”

“How about Dr. Carstens? You said he was good-looking.”

“He’s married.”

“Well, the other one, then?”

“He’s practically married.”

“Well, how about the big shot?”

“He’s a grandfather.” She said it sarcastically.

Marcie threw her hands up and laughed. “Laura, I’m going to have to do something about you.”

“Don’t do anything about me, please, Marcie.” Something in the tone of her voice sobered Marcie up.

“Why not?” she said.

“I—I just don’t want to be a bother, that’s all.”

“A bother!” Marcie came and sat beside her on the bed, wearing only the bottoms of a pair of blue jersey pajamas, cut like slim harem pants. Her breasts were high and full and unbearably sweet. “Laura, I like you. We’re living together. We’re friends. I guess I’ve made a bad impression on you with Burr and everything, but I want you to know I really like you. You’re no bother.” She smiled. “I’ll get Burr to fix you up with Jack Mann. We’ll go somewhere together. We need to get out. Maybe we’d quit quarreling if we didn’t sit around this apartment all the time.”

She paused, and Laura tried not to look at her.

“How about it?” Marcie said.

Laura was in a familiar situation. She’d been in it before, she’d be in it again, there was no escaping it. This is a heterosexual society and everybody plays the game one way or another. Or pretends to play it for appearances’ sake.

“I’d love to,” Laura said.

“Good! What night?”

“Any night.” Laura wanted to shove her off the bed, to throw the covers at her; anything to cover up her gleaming bosom. She felt herself go hot and cold by turns and it exasperated her. She wondered how obvious it was. But even in her discomfort she knew it didn’t show as much as it felt. She finally climbed past Marcie and out of the bed, making a hasty way to the bathroom.

“I’ll call Burr,” Marcie called after her.

Laura closed the bathroom door and leaned heavily against it, panting, her arms clasped tight around herself, rocking back and forth, her eyes shut. Spasms went through her and she shook herself angrily. Her hands stole downward in spite of herself and suddenly all her feeling was fixed in one place, clarified, shattering. There was a moment of suppressed violence when she clapped one hand over her mouth, helpless in her own grasp, and her imprisoned mouth murmured, “Marcie, Marcie, Marcie,” into her hand. And then came relief, quiet. The trembling ceased, the heaving breath slowed down. She relaxed utterly, with only just enough strength in her legs to hold her up, depending on the door to do the rest. “Damn her,” she said in a faint whisper. “Damn her.” It was the first time she realized how strong her “friendly” feelings for Marcie really were and she was dismayed.

Laura went quickly to the washbowl and turned on the tap. She ought to be making some noise. People don’t disappear into bathrooms for ten minutes in utter silence. At least not in this bathroom where every pipe had its own distinct and recognizable scream. In a few seconds Marcie was calling at her through the door.

“Laura? Can I come in?”

“Of course.”

“We’re going to make it for Friday. We’ll see a show.”

“That sounds fine.”

“It’ll be fun.”

I will not look at her, Laura told herself, and buried her face in a washcloth. She scrubbed herself assiduously while Marcie chattered. Damn her anyway, I won’t look at her. She has no claim on me, that was a silly fool thing I did. I’ll pretend it didn’t happen. It didn’t happen, it didn’t happen. She was afraid that if she did look it might happen again. She rinsed her face slowly and carefully in water from the groaning tap, and still Marcie stood there talking.

Laura reached for a towel and dried her face. She hung the towel up again and turned to walk out of the bathroom, ready to ignore Marcie. But Marcie had slipped into pajama tops and looked quite demure. Except for her extraordinarily pretty face. Laura stared at her, as she had known she would, as she did more and more lately.

“We’ll take in a show in Greenwich Village, because it’s easier to get tickets—at least to this one—and besides, Burr knows—what’s the matter, Laura?”

“What? Oh, nothing. Nothing.”

“You looked kind of funny.”

“Did I? I didn’t mean to. That sounds fine, the show I mean.” She hurried past Marcie into the bedroom.

In bed she cursed herself for an idiot. I’m just an animal, she berated herself. I hardly know Marcie. I won’t start feeling this way, I won’t!

Out of the past rose the image of another face, a face serenely lovely, a face whose owner she had loved so desperately that she had finally been forced to leave school because of her.

Why, they look alike! she thought, startled. Why didn’t I see it before? I must be blind. They look alike, they really do. In the dark she pictured Marcie’s face beside the other, matching, comparing, regretting. It tore at her heart to see them together. She wished the morning would never come when she would have to get up, bright and cheerful and ordinary, like every other morning, and look at Marcie’s face again. And Marcie’s breasts.

Morning came, as mornings will, and it went the same way. It was not intolerable. Laura was secretly on guard against Marcie now. Or rather, on guard against herself. She wasn’t going to fall. Marcie loved a man—men, anyway—and Laura wasn’t in any hurry to go through hell with her.

A curious change had come over Laura since the days of the terrible, and wonderful, college romance with a girl named Beth. She had been so frightened then, so lost, so completely dependent on Beth. She had no courage, except what Beth gave her; no strength except through Beth; no will but Beth’s. She had loved her slavishly; adored her. And when Beth left her for a man, when she told Laura it had never been real love for her at all, Laura was wounded clear through her heart.

All these things were unknown to Merrill Landon; unknown and unsuspected. They would remain forever in the dark corners of Laura’s mind, where she heaped her old hurts and fears.

She had thought of killing herself when she left school and went home to face her father. But she was young and her youth worked against such thoughts. Perhaps the very fact that she had loved so deeply and so well prevented her. She had learned to need love too much to think seriously about death.

Beth had left scars on Laura. But she had been a good teacher too, and some of the things she taught her lover were beginning to assert themselves, now that Laura was on her own and time was softening the pain. Laura walked tall. She felt tall. It wasn’t the simple physical fact of her height. It was a curious self-respect born of the humiliation of her love. Beth had taught Laura to look within herself, and what she found was a revelation.

Chapter Four (#ulink_49c974e0-eade-5502-9422-cf2eb590f13a)

The following evening Laura got home rather early after seeing a show with Sarah. She rode home on the subway with a dirty gray little man, repulsively anxious to be friendly. He kept saying, “I see you’re not married. You must be very careful in the big city.” And laughed nervously. Laura turned away. “You mustn’t ignore me, I’m only trying to help,” he whined. He babbled at her about young lambs in a den of wolves until she got off. He got off with her, still talking.

Laura wasn’t afraid—just mad. She turned suddenly on the little gray man at the subway entrance and said, “Leave me alone or I’ll call the police.”

He smiled apologetically and began to mumble. Laura’s eyes narrowed and she turned away contemptuously, walking with a sure swift gait that soon discouraged him. Something proud and cold in her unmanned him. At last he stopped following and stood gaping after her. She never looked back.

Laura arrived home, her cheeks warm with the quick walk and with the victory over the little man. God, if I could do that to my father! she thought wistfully. She walked up the flight of stairs from the twelfth floor to the penthouse and swung open the front door. The living room was lighted and so was the kitchen. The bedroom door was open, the room showing a cool blue beyond the loud yellow kitchen. Laura walked in, swinging her purse, thinking of the ugly little man and proud of the way she had trounced him.

She stopped short with a gasp at the sight of Burr and Marcie naked together in Marcie’s bed. “I’m sorry!” she exclaimed, and backed out, closing the door behind her. She collapsed on a kitchen chair and cried in furious disgust for half a minute. Then she stood up and went to the refrigerator, pretending to want a glass of milk just for an excuse to move, to ignore the hot silence in the next room.

For a while no sounds issued from the bedroom. Laura poured the milk busily and carried it into the living room. She was just putting a record on when the bedroom door opened and Marcie slipped out in her bathrobe. Laura had put her milk down. Just the sight of it was enough to make her feel green. She turned to Marcie.

“Hi,” she said, too brightly. “Sorry I had to go and break in.”

Marcie burst out laughing. “That’s okay. Damn him, I told him to go home. I knew you’d get home early. I just had a feeling.” She went up to Laura, still laughing, and Laura turned petulantly away. Marcie didn’t notice. “We took your advice, Laura,” she said. “We haven’t said a word to each other tonight. Well—I said when he came in—’All right, we’re not going to argue. Don’t open your mouth. Not one word.’ And he didn’t. He didn’t even say hello!” And her musical laughter tickled Laura insufferably.

Burr came out of the bedroom, looking rather sheepish, rather sleepy, very satisfied. He smiled at Laura, who had to force herself to wear a pleasant face. He was buttoning his shirt, carrying his coat over his arm, and all he said was, “Thanks, Laura.” He grinned, thumbing at Marcie. “We’re not speaking. I hear it was your idea.” He swatted Laura’s behind. “Good girl,” he said. He kissed Marcie once more, hard, drew on his coat, and backed out the door, still smiling.

Marcie whirled around and around in the middle of the living room, hugging herself and laughing hilariously. “If it could always be like that,” she said, “I’d marry him again tomorrow.”

Laura brushed past her without a word, into the kitchen, where she poured the milk carefully back into the bottle, closed the refrigerator door, went into the bedroom, and got ready for bed.

Marcie followed her, laughing and talking until Laura got into bed and turned out the light. She wouldn’t even look at Marcie’s rumpled bed. But it haunted her, and she didn’t fall asleep until long after Marcie had stopped whispering.

Jack Mann was small, physically tough, and very intelligent. He was a sort of cocktail-hour cynic, disillusioned enough with things to be cuttingly funny. If you like that kind of wit. Some people don’t. The attitude carried over into his everyday life, but he saved his best wit especially for the after work hours, when the first fine careless flush of alcohol gave it impetus. Unfortunately he usually gave himself too much impetus and went staggering home to his bachelor apartment under the arm of a grumbling friend. He was a draftsman in the office where Burr worked as an apprentice architect and he called his work “highly skilled labor.” He didn’t like it. But he did like the pay.

“Why do you do it, then?” Burr asked him once.

“It’s the only thing I know. But I’d much rather dig ditches.”

“Well, hell, go dig ditches then. Nobody’s stopping you.”

Jack could turn his wit on himself as well as on others. “I can’t,” he told Burr. “I’m so used to sitting on my can all day I’d be lucky to get one lousy ditch dug. And then they’d probably have to bury me in it. End of a beautiful career.”

Burr smiled and shook his head. But he liked him; they got along. Jack went out with Burr and Marcie before and after they got married. And after they got divorced. He was the troubleshooter until he got too drunk, which was often.

When he arrived with Burr on Friday night Laura was irked to find that she was taller than he was. She had made up her mind that she wasn’t going to enjoy the evening—just live through it. She’d have to spend the time mediating for Marcie and Burr and trying to entertain a man she didn’t know or care about. So she was put out to discover that she did like Jack, after all. It ruined her fine gloomy mood.

Marcie introduced them and Jack looked up at her quizzically. “What’s the matter, Landon?” he said. “You standing in a hole?”

Laura laughed and took her shoes off. It brought her down an inch. “Better?” she said.

“Better for me. Very bad for your stockings.” He grinned. “Have you read Freud?”

“No.”

“Well, thank God. I won’t have to talk about my nightmares.”

“Do you have nightmares?”

“You have read Freud!”

“No, I swear. You said—”

“Okay, I confess. I have nightmares. And you remind me of my mother.”

“Do you have a mother?” said Burr. “Didn’t you just happen?”

“That’s what I keep asking my analyst. Do I have to have a mother?”

“Jack, are you seeing an analyst?” Marcie was fascinated with the idea. “Imagine being able to tell somebody everything. Like a sacred duty. Burr, don’t you think I should be analyzed?”

“What will you use for a neurosis?” Jack asked.

“Do I need one?”

“How about Burr?”

“I’m taken,” Burr said. “Besides, you talk like a nitwit, honey. You don’t go to an analyst like you go to the hairdresser.”

Marcie’s eyes flashed. “Thanks for the compliment,” she said. “I’m not as dumb as I look.”

“Come on, Mother.” Jack took Laura’s arm and steered her out the door. “I see a storm coming up.”

But it was dissipated when Marcie grabbed her coat and hurried after them.

After the play they walked down Fourth Street in the Village, meandering rather aimlessly, looking into shop windows. Laura was lost. She had never been in the Village before. She had been afraid to come down here; afraid she would see someone, and do something, and suddenly find herself caught in the strange world she had renounced. It seemed so safe, so remote from temptation to choose an uptown apartment. And yet here she was with her nerves in knots, her emotions tangled around a roommate again.

Laura pondered these things, walking slowly beside Jack in the light from the shop windows. She was unaware of where she walked or who passed by. It startled her when Jack said, “What are you thinking about, Mother?”

“Nothing.” A shade of irritation crossed her face.

“Ah,” he said. “I interrupted something.”

“No.” She turned to look at him, uncomfortable. He made her feel as if he was reading her thoughts.

“Don’t lie to me. You’re daydreaming.”

“I am not! I’m just thinking.”

He shrugged. “Same thing.”

She found him very irritating then. “You don’t say,” she said, and looked away from him.

“You hate me,” he said with a little smile.

“Now and then.”

“I messed up your daydream,” he said. “I’m rarely this offensive. Only when I’m sober. The rest of the time, I’m charming. Someday I suppose you’ll daydream about me.”

Laura stared at him and he laughed.

“At least, you’ll tell me about your daydreams.”

“Never.”

“People do. I have a nice face. Ugly, but nice. People think, ‘Jesus, that guy has a nice face. I ought to tell him my daydreams.’ They do, too.” He smiled. “What’s the matter, Mother, you look skeptical.”

“What makes you think you have a nice face?”

“Don’t I?” He looked genuinely alarmed.

“It wouldn’t appeal to just anyone.”

“Ah, smart girl. You’re right, as usual. A boy’s best friend is his mother. Only the discriminating ones, my girl, think it’s a nice face. Only the sensitive, the talented, the intelligent. Now tell me—isn’t it a nice face?”

“It’s a face,” said Laura. “Everybody has one.”

He laughed. “You’re goofy,” he said. “You need help. My analyst is very reasonable. He’ll stick you for all you’ve got, but he’s very reasonable.”

Burr, who was walking ahead of them with Marcie, turned around to demand, “Somebody tell me where I’m going.”

“Turn right at the next corner,” said Jack. “You’re doing fine, boy. Don’t lose your nerve.”

“I just want to know where the hell I’m going.”

“That’s a bad sign. Very bad.”

“Cut it out, Jack,” said Marcie. “Where are we going?”

“A little bar I know. Very gay. I go there alone when I want to be depressed.”

It sounded sinister, not gay, to Laura. “What’s it called?” she said.

“The Cellar. Don’t worry, it’s a legitimate joint.” He laughed at her long face.

Marcie laughed too, and Laura’s heart jumped at the sweetness of the sound. It made her hate the back of Burr, moving with big masculine easiness ahead of her in a tweed topcoat, his bristling crew cut shining.

A few minutes later Jack led them down a few steps to a pair of doors which he pushed in, letting Laura and Marcie pass.

Laura heard Burr say, behind her, in an undertone, “It is gay,” and he laughed. “You bastard.” She was mystified. It looked pretty average and ordinary. They headed for a table with four chairs, one of the few available, and Laura looked around.

The Cellar was quite dark, with the only lights placed over the bar and glowing a faint pinky orange. There were candles on the tables, and people crowded together from one end of the room to the other. Everybody seemed reasonably cheerful, but it didn’t look any gayer than any other bar she had been in. She looked curiously at Burr, but he was helping Marcie out of her coat.

“No table service,” Jack said. “What does everybody want?”