Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

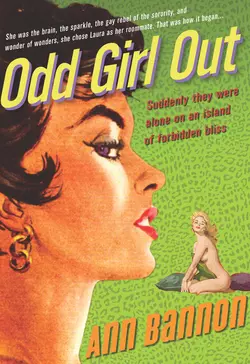

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerShe was the brain, the sparkle, the gay rebel of the sorority, and wonders of wonders, she chose Laura as her roommate. That was how it began…Suddenly they were alone on an island of forbidden blissTaking a pseudonym in the interest of privacy, Bannon wrote her first book, Odd Girl Out, as a coming-of-age novel that involved love between college sorority sisters. When an editor singled-out the school-girl romance as her story's most compelling feature, the book was re-written for a lesbian pulp fiction audience. Unlike most pulps, however, Bannon broke with tradition by avoiding sensationalistic plots in favour of emotionally engaged character development. Odd Girl Out enjoyed tremendous success, inspiring other ground-breaking works, most notably Beebo Brinker.“Odd Girl Out begins the saga of Laura, off on her own at college, appallingly shy and terminally polite…Laura meets Beth, whose brash straightforwardness and friendly attitude take the younger woman by storm, leading into an equally stormy affair” Metro Times

Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub12d7883-0929-55eb-8842-5785d075d590)

Title Page (#u499d5948-004b-5224-96c3-5b33b9041a22)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#u5d431c83-15b9-592a-bde3-63dc2f7a900e)

The Beginning … (#u3475689d-66bc-5993-8c82-762ecb327854)

Chapter One (#u42be6dca-4fc1-516c-90bb-3012acdaf19f)

Chapter Two (#u864de8de-ddef-56c5-8f88-521453e30312)

Chapter Three (#ucf6a2216-ea43-5e58-aaa7-2fdb6b92b4c8)

Chapter Four (#ua2cab555-f10e-593b-a5bd-328028217575)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#ulink_e6cb15b9-245a-57d2-9d7b-66ba21ed8b44)

I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of twenty-two to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience. I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just months behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world. There were millions living the same life; I was to be indistinguishable from them for many years, except for the fact, known to very few outside my immediate family, that I was the one who wrote a series of lesbian pulp paperback novels under the pen name of Ann Bannon. The stories came to be known as The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.

To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century, giving them an historical snapshot of the times. They have been revived in editions by five different publishers, once even coming out in a hard cover library edition. They have given comfort and courage to young gay people exploring their often difficult identities. They have even dismayed some in that community in our own time for their depiction of the stereotypes of the 1950s.

I sometimes shake my head and wonder, Who was that ingenuous twenty-two-year-old to be making these bold observations? Was she really me? Do I even know her anymore? Yes. She was me and I still recognize her. And I recall the characters I created, too. There they are in the pages written all those years ago: the girls I found so beguiling in college, the young women I met coming to the big city for the first adult adventures of their lives. In them, I still see the perplexities of identity, so pressing in youth, buried just beneath the sexual urgencies that drove us all. I see the older women, too, a little weary, a lot wary, many of them not that far in time from the utmost upheaval in their lives: World War II.

The world in the 1950s was changing in ways that were to lead inexorably to the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and yes, the Gay Rights Movement.

But those great social temblors were still in the future when I got my first look at a tranquil, almost rustic, Greenwich Village, with its parks, its crooked streets, its crafts shops, and its beckoning gay and lesbian bars. It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration. As I’ve often remarked, I felt like Dorothy throwing open the door of the old gray farm house and viewing the Land of Oz for the first time.

At that time, I was bubbling with stories of young arousal, but woefully lacking in what might be called “fieldwork experience.” I started to tell the story of a college sorority friend, heavily disguised of course, whose sexuality I suspected and who had aroused feelings in me that I both feared and enjoyed. I wanted to tell her story, and by telling hers to explore my own. I had absolutely no idea that I was on the cutting edge of anything, that I was about to catch a wave, or that others beside myself were engaged in similar creative tasks. I had read just two lesbian novels in my life: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Vin Packer’s Spring Fire.

It was to Vin Packer, then living and writing in New York, that I wrote with an appeal to help me get started. For her own reasons, she was kind enough to invite me to bring the unwieldy first draft of Odd Girl Out to New York. She would introduce me to her editor at Gold Medal Books, a major publisher of original pulp novels in the 1950s and 60s. The editor, Dick Carroll, took the book in hand. Within three days, he had read the manuscript. I waited in his office to hear the verdict.

“It’s pretty bad,” he said gently. “But I think it’s fixable. Go home, put this manuscript on a diet, and tell the story of the two girls. Then send it back to me.”

“The two girls?” Beth and Laura; I was dumbfounded. They had been no more than a distraction in the original story, based on girls I had known and admired in my college sorority. I was abashed to learn that my subtle little subplot had the makings of a novel, but all the other verbiage—what I had thought of as the novel—was smothering it.

I did go home, I did squeeze the story in half, I did write about Beth and Laura, amazed at the easy flow of the words. And months later, when Dick Carroll read it again, he published it, without changing a single word—without, in fact, even adding the word “lesbian,” which I had only just added to my vocabulary. It was not until thirty years later that I discovered that Odd Girl Out had been the second best-selling paperback book of 1957. I was off and running.

But how to follow up? Well, one writes what one knows. When I wrote Odd Girl Out, I knew college life. Now, I was determined to learn about gay life. New York was the focus of gay and lesbian culture in those days; it was electrifying to be there, even though my visits were necessarily brief, stolen from a conventional housewifely routine in Philadelphia. Once again, it was Vin Packer who helped me out and showed me around the Village; I will always be grateful for her help. I made the most of every moment. I visited every bar I could, and I got acquainted with some wonderful people. I walked the streets for hours, soaking it all up. On one occasion, I even walked home alone from a club at two in the morning. Such is the psychological armor of a twenty-two-year-old that I hadn’t the sense to be scared. I fully, frankly loved and embraced the Village.

But for all the exhilaration of these stolen moments, it was scary to write about lesbianism in the 1950s, the era of government repression, confining bias, and rigid social roles. I even worried that the FBI might be keeping a file on me. How did we get away with it, those of us writing these books? No doubt it had a lot to do with the fact that we were not even a blip on the radar screens of the literary critics. Not one ever reviewed a lesbian pulp paperback for the New York Times Review of Books, the Saturday Review, The Atlantic Monthly. We were lavishly ignored, except by the customers in the drugstores, airports, train stations, and newsstands who bought our books off the kiosks by the millions. The readers tended to enjoy them furtively; probably feeling as wary as I did when I wrote them. There was no public dialog about them in the media, either on their literary merits or their content, and that benign neglect provided a much-needed veil behind which we writers could work in peace.

And this had its benefits. Escaping public scrutiny as we did, we had a chance to talk about things that other writers usually handled—if they approached them at all—with a pair of tongs. We could take chances, we could be subversive, we could look at all the shameful, seductive, irresistible, delightful appeal of “the sex that dared not speak its name.” In a way, we were daredevils, protected by our unknown, uncredited, unsung noms de plume.

It took guts just to buy those books and confront the smirk on the face of the clerk at the cash register. People tried to disguise them in a pile of sundries they probably didn’t even need but bought anyway to distract attention from those eye-popping covers. I know—I was buying them, too. But once they had purchased them, they took the books home, read and re-read them, cherished them, and then hid them behind the fridge, in shoe boxes in their closets, under mattresses. It was a life-changing event if a spouse, a parent, or even a child found the books and challenged the reader. Nobody wanted to be shoved unceremoniously out of the closet, ready or not, particularly in that unforgiving time. But it did happen to many readers back then.

In Jaye Zimet’s book, Strange Sisters: the Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Penguin, 1999), for which I wrote the foreword, the colorful cover art for the lesbian pulps is given a showcase. Looking it over, I’m moved to wonder: How strange were our sisters? Even in the “exotic” and distant 1950s? Not very, truth to tell. Wonderful, but not strange, or at least, strange only on the covers of the books. When I was writing about them, I thought they were brave, passionate, gorgeous, and very, very cool. But not strange. And yet that word figures in dozens of the paperback book titles of the period as a sort of code for lesbian content, recognized by male and female readers alike.

Webster’s defines “pulp” as “tawdry or sensational writing.” In other words, sleaze. It never entered my head that I was writing sleaze; I was writing romantic stories of women in love. But it certainly entered the heads of the editors and publishers of the original pulps, and in a far from negative sense. Their job was to promote, market, and sell the books, and sleaze had a huge appeal. Furthermore, being men—most of them, anyway—they knew that the cover tease, showing a couple of desirable women who presumably would have interesting sex in the story, would lure a male audience and probably double their profits. Women readers could be relied on to read the covers iconically; men read them literally. Both would buy the books.

So the paperback publishers made money in what was basically the trashy trailer park of literature by lavishing curvy girls, lacy underwear, and heavy suggestions of sin and excess on their covers. That this frequently had little or no relationship to the actual characters and events in the stories was seldom a concern, any more than were the requests of the authors themselves with regard to cover illustration.

Neither were we consulted on the titles. I can remember tearing open the brown paper packages in which complimentary copies of my novels would arrive, and bracing myself for the shock of the cover art and, on occasion, even the title. The blurbs were lubriciously inventive: “The Savage Novel of a Lesbian on the Loose.” “They came to college sweet, pretty, and unsuspecting. But the house mother was strangely corrupt …” “Mary lacerated the flesh of a hundred girls with her searing caresses.” “The world of the third sex … that land of strange loves and rapacious passions.” “It was hard to figure out who was male and who was female … sometimes they were interchangeable.” “She found herself climbing down a ladder of flesh into a cesspool of Lesbian depravity.” With blurbs like these, who needed the critics’ praise to sell books? They flew off the shelves. And still nobody in the wider world took notice except the readers themselves.

Then the letters started pouring in. Those from the men were often propositions; those from the women were cries of the heart. The female readers wrote from little towns all over the country. Such was their isolation that many of them were grateful to me for reassuring them that they were not totally alone in the world. They wanted me to tell their stories, they wanted me to give them advice, and they wanted to meet me. They were sweet, tentative, grateful, scared, and even needier than I, if that’s possible, of education and support.

I wish I had those letters still—they were lost in one of many moves over the years. They would astonish the far more knowledgeable readership of women today in their ingenuousness, their yearning, their sense of exile, but with it all, their good humor, their sheer guts and perseverance. These women lived in a world where they thought themselves to be painfully unique. The bottom line was, they imagined themselves doomed to solitude in their yearnings for the rest of their lives and sadly, deservedly so, since they had no positive role models to contradict such self-prejudice. I admired and even loved them, although I only ever met one of them, through her personal determination to make it happen. I often think of them and hope their lives turned out better than they could then have known or dared to hope.

But these letters overwhelmed me. What to tell them? I was being appealed to for help as if I were a lesbian Ann Landers. Little did they know it was a case of the blind leading the blind. What could I, in my naiveté, possibly say that would help them through their sexual exile, give them warmth and hope? The only gift I could give back to these readers was another story.

In my visits to Greenwich Village, I had already learned to recognize the butch/femme dichotomy so influential at the time, and I wanted to write a book about a big, handsome, exasperating, reckless, bright, funny, irresistible butch. She would do what I could not. She would be what I could not. I already knew her in the theater of my mind, and I even knew her name: Beebo Brinker. I stole the “Beebo” from a childhood friend who couldn’t pronounce her given name of Beverly. The “Brinker” was my own inspiration. She was never modeled on a real woman, although several were influential in various ways. Instead she sprang like Minerva from my brow, propelled to life by the twin engines of fantasy and need.

When Beebo was at her buccaneer best, I was infatuated with her myself. When she was at her destructive worst, I was using her as a dumping ground for my own frustrations. She was tough and could take it, and made my life better and my spirit stronger by shouldering the troubles I couldn’t resolve. But it resulted in giving her a dark side I now wish I could soften.

I gave at least some of the stories a happy ending, sort of. Nobody had to be shot or jump in front of a train for the sin of loving another woman. Bad things did happen that reflected the arrogant ignorance of the authorities, the contempt of conventional society, and the occasional desperation of the women of the times; modern readers may feel impatient with some of this now, but it was part of life back then. But still there was humor and there was love, in at least as good measure, and I am most proud of having captured some of that temper of the times as well.

I had no idea I was being brave or daring when I started writing, so perhaps it doesn’t count. But after Odd Girl Out was published and I realized I was, I kept on writing anyway, so perhaps it does. One of the hardest things I ever had to do was hand a copy of the first edition of Odd Girl Out to my mother to read. It’s the one that shows the author’s name as “A. Bannon.” I was too shy then even to let my first name be printed on the cover. My mother was a strikingly pretty and spirited lady, whose beauty and willfulness had gotten her into three marriages and many scrapes. But for all that, she was raised by my little Victorian grandmother, who steeped her in the manners required of nice girls. It was part of the code that a lady simply sailed past unpleasantness wherever possible, taking no note of it.

My mother read the book and I waited for the toughest review of my life. As I waited, I thought of what must be going through her mind: all those home-movie recollections of a quirky little girl with a passion for books and music, cautious with new friendships, reassuringly like her age-mates to the eye but disturbingly intense and eccentric in other ways. Still, there was nothing in her memories to prepare her for what she was reading. It must have been breathtaking. She, of course, would never say so. I think she took courage from the fact that I was then a pretty young housewife and mother. Things couldn’t be too far off track. And besides, I was her daughter; she was going to support me if she could. Finally, she put the book down and said thoughtfully, “Sweetheart … I didn’t know you had it in you.” And then, because I was hers, and I had done something difficult in writing a book and getting it published, she added, “I’m proud of you.” I started breathing again. “But,” she added, “don’t ever show this to your grandmother.” I never did.

Perhaps it is only fair to mention the husband who played so minimal a role in Ann Bannon’s existence but so great a role in mine. He was aware of the general theme of the books, but it interested him not at all. The royalty checks, however, did. I think for that reason and others of his own, he did not try to discourage me. He read no more than a few paragraphs of Odd Girl Out, and that was enough for him. He was a basically good person; he meant well and he loved me, and I will not lay all the blame for my grief in that marriage at his feet. Suffice it to say that I have never regretted its ending, and am grateful to leave it at rest in the past. My children are now beautiful and successful adults, so there was a magnificent reward for the difficult years.

Why didn’t I stay in Greenwich Village when I had the chance? Why didn’t I break out of wedlock? Well, this was 1956. I was twenty-two and while I had a college education, it was ornamental; I had no marketable skills. I was also very much my mother’s child. In our family there was a grand tradition of soldiering through in the traditional role, whatever the challenges. My mother had done it and her mother before her. They were both very much alive and I was not going to let them down. This was familiar territory; better the shackles of the known than the terrors of the new and unfathomable.

Perhaps, also, I was just plain scared to assume an identity that seemed to me full of mystery, one which I was just beginning to recognize and understand. It had been clear to me from my earliest memories that I was not going to be like the other children I knew. Nobody else among my classmates had fallen secretly in love with the Statue of Liberty. I did, because she was the biggest, most beautiful, most powerful image of womanhood I had ever seen. Nobody else was in love with the picture of Mozart on our music books. I was, because he looked to me, with his delicate features and long hair, like a child magically suspended between the sexes.

I also had a fully reasonable fear of the public consequences. God forbid that a policeman should ever pluck me from a table in a lesbian bar, shove me into a paddy wagon, and put my name on the roster of criminals. The bars underwent regular police raids in those days, and if you were visiting one that hadn’t been hit for a couple of months, you were in peril.

Nor could I face the prospect of having my children snatched from me. When you get down to cases, I and many other women feared that most of all. Lesbians were an illegal social category—not really yet a community—with no right to exist. Furthermore, if you were tagged with the lesbian label, you were typed beyond any hope of revealing yourself as a human being in full. Knowing you were gay, people thought they knew all there was to know about you, and what there was to know about you was that you were contaminated. There was a scarlet letter “L” on your chest. It was an age when homosexuality was a disease and stereotyping ran roughshod over real human beings. The women who came out under this kind of fire and, in effect, told the Establishment to stuff it are my heroes.

As for me, I went another way. I thought I could simply continue to live in my imagination, could use writing as a pressure valve when things got too difficult. This I did through six novels, writing in hours stolen from the relentless tasks of running a household and raising my children, so I could spend time with Laura, Beth, Beebo and the others. You’ve heard of fantasy friends; they were mine.

And then … I stopped writing. For some reason, that run of incredible emotional energy flamed out. It’s never been entirely clear to me why, but I actually felt emptied of stories for a while. It was a period in my life when my children needed a lot from me, we were moving frequently, and what strength I had was concentrated on a deteriorating marriage. I wanted to feed my mind on something absorbing, something that would take me out of myself. When Lord Byron’s friends asked him why in the world he had taken up the study of Armenian, he replied, “I found that my mind wanted something craggy to break upon.” That is just how it felt—something tough enough to distract me from the problems in my life for which I could see no resolution.

So I went back to graduate school. I earned a teaching credential, a master’s degree, and ultimately, a doctorate. It was an undertaking that consumed a whole decade from the mid-60s to the mid-70s, and led me to a position as a college professor, then a program director, and finally, an assistant dean in the university where I pursued my academic career. I did a lot of writing, of course, but it was all academic papers, memos, study materials, and professional letters. Ann Bannon had ceased to exist; she had become a phantom of my surprising past, almost as much a fictional character as Beebo Brinker herself. I thought I would never return to her, that no one knew she had ever had a life or written a word. The Greenwich Village of the 1950s and 60s had never seemed so far away.

And then the unimaginable happened. The New York Times publishing branch, Arno Press, wrote to me. They wanted permission to include four of my books in a library edition of gay and lesbian literature, under the rubric Homosexuality: Lesbians and Gay Men in Society, History and Literature. It was the first hint I had that Beebo Brinker and her creator had earned a life of their own.

I gratefully accepted the offer from the Times, and the hardcover edition was duly published. That, I thought, must be that; it was a sort of fluke. There was a glimmer of interest in the books as vignettes of a bygone time; indeed, in Ann Bannon herself as a sort of historical artifact. But the wave subsided. Several years went by, during which my children entered college, my long and difficult marriage ended, and my university career prospered.

And then it happened again. I was alone for the first time in my life in the early 1980s, living in a rental townhouse, when the telephone rang at a severely early hour one morning. It was Barbara Grier of Naiad Press, calling from Tallahassee, Florida. She had gotten my name from the people at Arno Press and tracked me down. I remembered Barbara’s name from the years when I was avidly reading any copies of The Ladder that I could get my hands on, and she was editing it as Gene Damon; I remembered reading about a bibliography of lesbian literature she had compiled, but I had never seen it. The name of the Naiad Press was entirely new to me.

But not for long. Barbara and her partner, Donna McBride, wanted to bring out the five books which had to do with Laura, Beth, and Beebo. It was my first inkling that my stories had been valued and preserved by a whole generation of women; that despite the crumbling condition of the old pulp paper and fading ink, they had survived on many bookshelves in many homes.

Barbara and I arranged to meet at a public appearance she had scheduled at Old Wives’ Tales Women’s Bookstore in San Francisco, where she introduced me to a cheering crowd. It was a wonderful, if confounding, re-introduction to the lesbian world. I met her and Donna again at a conference of the National Women’s Studies Association at Humboldt State University, where I signed the contract that resulted in the Naiad Press re-issuance of the books. First came a pocket book edition in 1983; then a trade paperback edition in 1986. I held my breath, fearing an indifferent reception from the public. But women all across the country embraced these stories of a now far-off generation of sisters. It was not just history; it was their history.

I have always been gratified that the books sold so well and rewarded the confidence that Barbara and Donna placed in them. The debt I owe them has been frequently acknowledged over the intervening years, but it bears repeating. They really brought Beebo back to life, and in so doing, gave Ann Bannon a presence in the community that she would not otherwise have had. It was a remarkable gift, and one for which I will always be thankful.

As a direct result of the Naiad editions, I was featured in the documentary movie, Before Stonewall, in the mid-1980s; and subsequently in the Canadian-produced film of lesbian lives made in the early 90s, Forbidden Love. Imagine coming back from the dead after more than twenty years and discovering that scholarly articles have been published about you, that there are master’s theses dealing with your work, and university literature classes teaching it.

In time, the Naiad Press editions ran their course while I labored in the groves of Academe. Almost a decade after the trade paperback edition came out, and as the remaining copies of that edition were being depleted, lightning struck again. This time it was the Quality Paperback Book Club, a subsidiary of Book-of-the-Month Club, which wanted to publish an omnibus edition of four of the books as part of their Triangle Classics: Illuminating the Gay and Lesbian Experience.

It seemed to me that nothing more could possibly happen to these books. They had enjoyed an unprecedented run. They had given me access to a vibrant young community, a whole new generation of men and women who listened as I lectured in venues across the country, and gave me an affectionate reception. They could have been judgmental and dismissive of the picture my books provided of “the way we were.” By and large, however, they were generous. They knew it hadn’t been easy, that we ourselves had been victimized back then by the very biases we denied, that somebody had to get the ball rolling. And those of us who had survived those days were taken to their hearts. They are fighting new battles for respect and acceptance, and it is good to know that there is an historical foundation to build on, that it wasn’t just the bad stuff happening “before Stonewall”; there was good stuff, too, and it had a far-reaching influence.

Now, Beebo is extending her welcome into the lives of yet another generation, thanks to the enterprise and faith of Cleis Press in San Francisco. It’s surprising to think that the 80s already seem distant to many young gays and lesbians, but to those entering adulthood today, they do. The old Naiad editions are themselves collector’s items. I have attended conventions of vintage paperback book collectors, and there they are, along with the really ancient Gold Medals, which seem like antiques now even to me.

Perhaps the longevity that I and my work have enjoyed is more a matter of endurance than any other quality. They say if you live long enough, the world will circle back around to have another look at you. It’s called “re-discovery,” and it’s an interesting process. As part of it, I have seen the butch/femme opposition, so potent in the 50s, rejected by women in the first excitement of the Women’s Movement, when strict equality was the order of the day; then accepted again as one of many possible models through which women may relate to one another. I’ve seen the Dream Machine in Hollywood go from the good-natured tolerance of gays in the early days, to gays as degenerate thugs in the 60s and 70s, to gays as romantic leads in our own time. There’s a long way to go, but we’re picking up speed, and the popular culture reflects the strength and confidence of an energized community.

When I lectured at the Eureka/Harvey Milk Branch of the San Francisco Public Library a year ago, I thanked a large, friendly audience for coming out in force to support me that evening. Every writer, every craftsman, every artist knows how much it means. And I closed with this little quote from British philosopher J.M. Thornburn, which should fire the creative spark in every heart:

“All the genuine deep delight in life lies in showing others the mud pies you have made. And life is at its finest when we confidingly recommend our mud pies to one another’s sympathetic consideration.”

Thank you, Gentle Readers, for your sympathetic consideration of my own mud pies, these stories of another age. May you forgive Beebo and her friends their faults, and enjoy them for their guts and humor.

Ann Bannon

Sacramento, CA

June 2001

The Beginning … (#ulink_36e8a57a-f844-55d9-85a8-9d0e56392613)

“Mmmm …” Beth murmured as Laura’s hands began to trace the curves of her back. “Oh, that’s marvelous.” She shivered a little and Laura trembled with her. “Under my pajamas, Laur.”

Warily, Laura lifted the pajama shirt and groped for the ripe smooth warmth beneath.

“Oh, yes …” Beth sighed.

And Laura’s hands descended to their enthralling task again, caressing the flawless hollows, the sweet shoulders. She was lost to reason now. She parted the hair that hid Beth’s neck and drew her fingers lightly over the white nape. She leaned closer, hardly aware that she moved. With a swift thrill of necessity she bent and kissed the softness for a long moment.

Then sudden fear pulled her up. She put her hand to her mouth and stared in terror at Beth. Beth lay perfectly still, a faint smile on her lips.

“Beth?” said Laura. “Beth?” The whisper quailed. “Oh, Beth! Say something! Forgive me! Say something! Are you mad at me?”

Beth whispered softly, “No.”

A wash of heat flooded Laura’s face. She bent over Beth and began to kiss her like a wild, hungry child, pausing only to murmur, “Beth, Beth, Beth….”

Beth rolled over on her back then and looked up at Laura, reaching for her, breathing hard and smiling a little, and her excitement consumed the last of Laura’s reserve. Her lips found Beth’s, and found them welcoming….

One (#ulink_17b491fe-4834-5574-982c-eafbd4cef213)

The big house was still, almost empty. Down the bright halls and in the shadowy rooms everything was quiet. Upstairs a few desk lights burned over pages of homework, but that was all.

There was one room in the sorority house, however, where no reading was going on. It was a big, warm room, meant for sprawling and studying and socializing in, like the others. Three girls shared it and two of them were in it now on this autumn Sunday night.

One was a newcomer. Her name was Laura and she had just finished moving all of her belongings into the room. It was a scene of overstuffed confusion, but at least she had somehow succeeded in squeezing all her things in and now there remained only the job of finding a place for them. Laura sat down to rest and worry about it. She tried to ignore the other girl.

Beth lay sprawled out on the studio couch with her head cushioned on a rambling pile of fat pillows at one end and her feet dangling over the other. She was drinking a Coke, resting the bottle on her stomach and letting it ride the rhythm of her breathing. She wore slim tan pants and a dark green sweatshirt with “Alpha Beta” stamped in white on the front. Her hair was dark, curly, and close-cropped.

Laura sat by choice in the stiff wooden desk chair, as if Beth were too comfortable and she could make amends by being uncomfortable herself. She was nervously aware of Beth’s scrutiny, and the sorority pledge manual she was trying to read made no sense to her. Beth seemed like all good things to Laura’s dazzled eyes: sophisticated, a senior, a leader, president of the Student Union, and curiously pretty. She had a well-modeled, sensitive face with features not bonily chic like those of a mannequin, but subtle, vital, harmonious. She wasn’t fashionably pretty but her beauty was healthy and real and her good nature showed in her face.

Laura flipped nervously through her pledge manual, not even pretending to read any more. Finally Beth saw that she wasn’t reading and smiled at the ruse.

“One hundred and thirty-seven pages of crap,” she said, nodding at the manual. “All guaranteed to confuse you. I don’t know why they don’t revise the damn thing. I’ve passed an exam on it and I still don’t understand it.”

Her attitude embarrassed Laura, who smiled uncertainly at her new roommate, thinking as she did so how many times she had smiled in the same way at Beth, not sure of how she was expected to react.

She had never known quite how to react to Beth from the first day she had seen her. It had been shortly after Laura’s arrival at the university, when everything she saw and felt excited her to a high pitch of nervous awareness. Even the sweet smoke of bonfires in the early-autumn air smelled new and tantalizing.

Laura walked around the university town of Champlain, down streets chapeled with old elms; past the new campus with its clean, striking Georgian buildings and past the old with its mellow moss-covered halls; past that copy of the Pantheon that passed for the auditorium; past the statues; past the students walking down the white strip of the boardwalk, sitting on the steps of buildings, stretching in the grass, and talking … always talking.

It thrilled her, and it frightened her a little. Some day she would know all of this as well as her home town; know the campus lore and landmarks, the Greek alphabet, the football heroes, the habits of the campus cops. Some day she wouldn’t have to ask the questions—she would be able to answer them. It made her feel a sort of grateful affection for the campus already, just to think of it this way.

She had been in school a week when she went up to the Student Union to join an activity committee. It seemed like a good way to meet people and get into the university’s social life. Laura had an appointment for an interview at three o’clock. She sat in the bustling student activities center on the third floor waiting to be called, clearing her throat nervously and sneaking a look at herself in her compact mirror. She had a delicate face shaped like a thin white heart, with startling pale blue eyes and brows and lashes paler still. A face quaint and fine as a Tenniel sketch.

She waited for almost half an hour and the sustained anxiety began to tire her. She stared at her feet and up to the clock, and back to her feet again. It was when she glanced at the clock for the last time that she saw Beth for the first.

Beth was standing halfway across the room, tall and slender and with a magnetic face, talking to a couple of nodding boys. She was taller than one of them and the other acted as if she towered over him, too. Laura watched her with absorbed interest. She tapped the smaller boy on the shoulder with a pencil as she talked to him and then she laughed at them both and Laura heard her say, “Okay, Jack. Thanks.” She turned to leave them, coming across the room toward Laura, and Laura looked suddenly down at her shoes again. She told herself angrily that this was silly, but she couldn’t look up.

Suddenly she felt the light tap of a sheaf of papers on her head, and looked up in surprise. Beth smiled down at her. “Aren’t you new around here?” she said, looking at Laura with wide violet eyes.

“Yes,” Laura said. Her throat was dry and she tried to clear it again.

“Are you on a committee?”

She was strangely, compellingly pretty, and she was looking down at Laura with a frank, friendly curiosity that confused the younger girl.

“I’m here for an interview,” Laura said in a scratchy voice.

Beth waited for her to say something more and Laura felt her cheeks coloring. A young man thrust his face out of a nearby door and said, “Laura Landon?” looking around him quizzically.

“Here.” Laura stood up.

“Oh. Come on in. We’re ready for you.” He smiled.

Beth smiled, too. “Good luck,” she said, and walked away.

Laura looked after her, until the boy said, “Come on in,” again.

“Oh,” she said, whirling around, and then she smiled at him in embarrassment. “Sorry.”

The interview turned out well. Laura joined the Campus Chest committee and turned her efforts toward parting students from their allowances for good causes. Every afternoon she went up to the Union Building and put in an hour or two in the Campus Chest office on the third floor, where most of the major committees had offices.

It was nearly two weeks later that Beth stopped in the office to talk to the chairman. She sat on his desk and Laura, carefully looking at a paper in front of her, listened to every word they said. It was mostly business: committee work, projects, hopes for success. And then the chairman told her who was doing the best work for Campus Chest. He named three or four names. Beth nodded, only half listening.

“And Laura Landon’s done a lot for us,” he said.

“Um-hm,” said Beth, taking little notice. She was gathering her papers, about to leave.

“Hey, Laura.” He waved her over.

Laura got up and came uncertainly toward the desk. Beth straightened her papers against the top of the desk, hitting them sideways the long way and then the short way until all the edges were even.

“Beth, this is Laura Landon,” the boy said.

Beth looked up and smiled. And then her smile broadened. “Oh, you’re Laura Landon,” she said. She held out her hand. “Hi, Laur.”

Nobody had ever called her “Laur” before; she wasn’t the type to inspire nicknames. But she liked it now. She took Beth’s hand. “Hi,” she said.

“You know each other?” the chairman said.

“We’ve never had a formal introduction,” Beth said, “but we’ve had a few words together.” Laura remained silent, a little desperate for conversation.

“Well, then,” said the chairman gallantly, “Miss Cullison, may I present Miss Landon.”

“Will Miss Landon have coffee with Miss Cullison this afternoon?” said Beth.

Laura smiled a little. “She’d be delighted,” she said.

They did. And she was. An occasional fifteen- or thirty-minute coffee break was traditional at the Union Building. Beth and Laura went down to the basement coffee shop, and came up two hours later because it was time finally to go home for dinner. Laura couldn’t remember exactly what they talked about. She recalled telling Beth where she was living and what she was studying. And she remembered a long monologue from Beth on the Student Union activities and what they accomplished. And then suddenly Beth had said, “Are you going to go through rushing, Laur?”

“Rushing?”

“Yes. To join a sorority. Informal rush opens next week.”

“Well, I—I hadn’t thought about it.”

“Think about it, then. You should, Laura. I’m on Alpha Beta and, strictly off the record, I think we’d be very interested.”

“Why would Alpha Beta want me?” Laura said to her coffee cup.

“Because I think it’s a good idea. And Alpha Beta listens to Beth Cullison.” She laughed a little at herself. “Does that sound hopelessly egotistical? It does, doesn’t it? But it’s true.” She paused, waiting until Laura looked at her again. “Sign up for rushing, Laura,” she said, “and I’ll see to it you’re pledged.”

“I—I will. I certainly will, Beth,” Laura said, hardly daring to believe what she’d heard.

Beth grinned. “My God, it’s nearly five-thirty,” she said. “Let’s go.”

After that it had been easy. Beth spoke the truth; Alpha Beta did listen to her. Laura had signed up for rush, with the secret understanding that she would pledge Alpha Beta. But even at that, it was a thrill when Beth called her two days after rushing was over and said, “Hi, honey. Pack your things. You’re an Alpha Beta now. Officially.”

Laura had cried over the phone, and Beth said, “You don’t have to, you know.”

“But I want to!”

Beth laughed. “Okay, Laur, come on over. You just joined one of the world’s most exclusive clubs. And you have a new roommate. In fact you have two.”

“Two?”

“Yes. Me. And Emily.”

Emily had spent the day with them, helping Laura bring things in and put them away. Laura was so tired now she could hardly recall Emily’s face; all she remembered was a warm, ready laugh and the vague impression that Emily was fashioned to please the fussiest males: the ones who want perfect looks and perfect compliance in a woman.

Beth had called a halt to their work early in the evening.

“We’ve done enough, Laura,” she had said, dropping down on the studio couch. “We’ve even done too much.”

“It was wonderful of you to help me, Beth.”

“Oh, I know. I’m wonderful as all hell. I only did it because I had to.” She grinned at Laura, who smiled self-consciously back. Beth liked to tease her for being too polite and it made Laura uncomfortable. She would have gone to almost any length to please Beth, and yet she could not abandon her good manners. They struck her as one of her best features, and it puzzled her that Beth should needle her about them. She knew Beth could carry off a courtesy beautifully at the right moment; Laura had seen her do it. But Beth was much less formal than her new roommate, and furthermore she liked to swear, which Laura thought extremely unmannerly. Beth made Laura squirm with discomfort. And in self-defense Laura tried to build a wall of politeness between them, to admire Beth from far away.

There was a vague, strange feeling in the younger girl that to get too close to Beth was to worship her, and to worship was to get hurt. As yet, Beth made no sense to her, she fit no mold, and Laura wanted to keep herself at an emotional distance from her. She had never met or read or dreamed a Beth before and until she could understand her she would be afraid of her.

Laura had been thinking about this that afternoon while she filled the drawers of her new dresser with underwear and sweaters and scarves and socks, and had resolved right then that she must always be on her guard with Beth. She didn’t know what she was trying to shield herself from; she only felt that she needed protection somehow.

Beth had suddenly put an arm around her shoulders, shaking the thoughts out of her head, and said with a laugh, “For God’s sake, Laur, how many pairs of panties do you have? Look at ’em all, Emmy.”

And Emily had looked up and laughed pleasantly. Laura couldn’t tell if she was laughing at the underwear or at Beth or at the look on Laura’s face, for Laura looked as surprised as she was. She stood there for a minute, feeling only the weight and pull of Beth’s arm and not the necessity to answer.

In a faint voice Laura answered, “My mother buys all my underwear. She gets it at Field’s.”

“Well, she must’ve cleaned them out this time,” said Beth, smiling at the luxurious drawerful. “I’ll bet they put in an emergency order for undies when she leaves the store.”

Emily laughed again and Laura shut the drawer with a smack and cleared her throat. She hated to talk about lingerie. She hated to undress in front of anyone. She even hated to wash her underwear because she had to hang it on the drying racks in the john or in the laundry room where everyone could see it. It was no comfort to her that everybody else did the same thing.

“Of course, I don’t believe in underwear myself,” said Beth airily. “Never wear any.” She swept a stack of sweaters theatrically off the table and handed them to Laura, who gazed at her in dismay, reaching mechanically for the sweaters. Beth laughed. “I’m pretty wicked, Laur.”

“Don’t you really wear any—any underwear?” Her whole upbringing revolted at this. “You must wear some.”

Beth shook her head, enjoying Laura’s distress and surprised at how little it took to shock her. Laura looked at her with growing outrage until she burst out laughing and Emily intervened sympathetically.

“Beth, you’re going to make your poor little roommate think she’s fallen in with a couple of queers,” she said with a giggle.

Beth grinned at Laura and the younger girl felt strangely as if the bottom had fallen out of her stomach.

“She has,” said Beth with emphatic cheerfulness. “She ought to know the dreadful truth. We’re characters, Laura. Desirable characters, of course, but still characters. Are you with us?”

Laura wished for a moment that she were all alone in a vacuum. She didn’t know whether to take Beth seriously or not; she felt as if Beth were testing her, challenging her, and she didn’t know how to meet the challenge. She transferred a sweater nervously from one hand to the other and tried to answer. Nobody was a more rigid conformist, farther from a character, than Laura Landon. But the bothersome need to please Beth prompted her to say weakly, “Yes.”

She put the sweater in a drawer, turning away from Beth and Emily as she did so, and silently and secretly scraped the white undersides of her forearms. It was an old gesture. Whenever she was disappointed with herself she bruised herself physically. The sad red lines she raised on her skin were her expiation, a way of squaring with herself.

Beth, who could see she had gone far enough, confined herself for a while to friendly suggestions and answering questions. It was a great relief to Laura. She was almost herself again when Beth suggested a tour of the sorority house.

The two girls went first up to the dormitory on the third floor, where everybody but the housemother and the household help slept.

“Does anyone ever sleep in the rooms?” Laura asked as they mounted the stairs.

“Oh, once in a while. In the winter, when the dorm is really cold, some of the kids sleep in their rooms. The studio couches unfold into double beds. They can sleep two.”

They had entered the big quiet dorm with its dozens of iron bunks beds smothered in comforters and down pillows and bright blankets. Laura shivered in the chill while Beth pointed out her unmade bed to her.

“We’ll have to come back and make it up later,” she said.

Beth had then led Laura down to the basement. She was enjoying this new role of guide and guardian, enjoying even more Laura’s unquestioning acceptance of it. They found themselves playing a pleasant little game without ever having to refer to the rules: when they reached the door to the back stairs together, Laura stopped, as if automatically, and let Beth hold the door for her. Laura, who tried almost instinctively to be more polite than anybody else, readily gave up all the small faintly masculine courtesies to Beth, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, as if Beth expected it of her. There was no hint that such an agreeable little game could turn fast and wild and lawless.

In the basement Beth showed her the luggage room, shelved to the ceiling and crowded with all manner of plaid and plastic and leather cases. In the rear of the room was a closed door.

Beth turned around to go out and bumped softly into Laura, who had been waiting for an explanation of the closed door.

Laura jumped back and Beth smiled slowly and said, “I won’t eat you, Laur.”

Laura felt a crazy wish to turn and run, but she held her ground, unable to answer.

Beth put her hands gently on Laura’s shoulders. “Are you afraid of me, Laur?” she said. There was a long, terribly bright and searching silence.

“I wondered what the door in back was to,” Laura faltered. Her sentence seemed to hang suspended, without a period.

Beth let her hands drop. “That’s the chapter room,” she said. “Verboten. Until you’re initiated, of course.”

“Oh,” said Laura, and she walked out of the luggage room with Beth’s strange smile wreaking havoc in the pit of her stomach.

On the way upstairs they met Mary Lou Baker, the president of Alpha Beta. She came down the stairs toward them, towing a bulging bundle of laundry which bumped dutifully down the stairs behind her. She smiled at them and said, “Hi there. How’s the unpacking coming, Laura?”

“Fine, thank you.” Laura watched Mary Lou retreat into the basement, impressed with her importance.

“She likes you,” said Beth as they headed back up to their room.

“She does?” Laura smiled, pleasantly surprised.

“Um-hm,” Beth answered. “Usually she has nothing to say to newcomers for a few weeks. If she notices you right away it’s a good sign. At least it is if you’re interested in her approval.” She said this rather disparagingly.

Walking down the hall behind her, Laura smiled.

And now here they were in the calm of a Sunday night, alone in their room, curious and shy at the same time. Beth finished her Coke and set the bottle down on a glass-topped coffee table in front of the studio couch. The clack of glass on glass startled Laura and the pledge manual slipped from her hands to the floor.

“Want to go make your bed up now?” Beth said. Her voice was soft, as if she were rather tired.

“Oh, yes. I guess I’d better.”

“I’ll help you.” Beth sat up, swinging her long legs to the floor. She sat still for a minute as if getting her bearings, looking at her feet. Then she lit a cigarette. “Come on, let’s go do it,” she said finally with a sudden brightness.

“I’ll do it, Beth,” said Laura firmly. “You’ve done so much for me today, I just hate to have you do any more.”

Beth blew smoke over the table top. “Laura, if you don’t stop thanking me for everything you’re going to wear me out,” she said. “Or turn my head.” She said this good-naturedly, to tease more than to scold. But then she saw that she had hurt Laura and she wanted instantly to reach out with comfort and reassurance. She was not impatient with Laura’s hypersensitivity, only unused to it. She never knew when she might scrape against it and cause pain.

Laura’s mouth tightened and she gripped the cover of her pledge manual in an effort to calm herself.

“Laura,” Beth said in a gentle voice, and she got up and went over to her. Laura drew back in surprise as Beth dropped to her knees in front of the chair, putting a hand on Laura’s knees and smiling up at her. Laura was too startled to pretend composure.

“Laur, have I hurt your feelings, honey? I have, haven’t I? Answer me.”

Laura said helplessly, “No, Beth, really—”

“I know I have,” Beth interrupted her. “I’m sorry, Laur. You mustn’t take me so seriously. I’m only teasing. I like to tease, but I don’t like to hurt people. You just have to get used to me, that’s all. Take me with a grain of salt.” She looked earnestly at her with the shade of a smile on her lips and she thought how good it would be to skid her hands hard up Laura’s thighs and…. So she kept talking. It was better to ignore the peculiar feelings Laura awoke in her; she covered her confusion with words.

“Because I want us to be good friends,” she went on. “And I’ll try not to—to shock you any more. I guess I’m a little crazy—the result of a misspent youth, of course.” And she grinned. “But I’m not dangerous, honest to God. Now—” she smacked Laura’s knees amiably—“we’re over the first crisis. Are we going to be friends, Laur?”

Laura wanted desperately to pull her knees together. “Yes,” she said to Beth. “I hope so.”

“Good!” said Beth and she bounced to her feet. “Come along then. Let’s make your bed.”

It hadn’t taken long to make up the austere box bed and Laura found herself back in the room and faced with the humiliating problem of undressing in front of somebody else. Her shyness settled in her cheeks and neck like a heat rash. As soon as she felt the burn, it spread to her shoulders and bosom. She blushed very easily and she despised herself for it. She wanted to scratch at her arms again, but because Beth would notice it she had to content herself with biting the tender flesh of her underlip until she was afraid it would bleed and cause her more grief.

She turned as far from Beth as she could and unbuttoned her blouse, somehow feeling that Beth’s bright eyes were doting on every button. But Beth was subtle; she was humming a tune and busy with her pajamas. She saw Laura without seeming to and Laura began to envy her pleasant abandon. After a moment she said, “Laur, do you have a sweatshirt?”

“Yes.” Laura eyed her quizzically.

“Better put it on. The dorm is a damn deep freeze.”

Laura found the sweatshirt and pulled it over her head, and Beth led her up to the dorm. On the door was posted a wake-up chart with a pencil on a string hanging beside it. Beth signed Laura’s named under “6:45.”

“Think you can find your bed?” she asked.

“There it is,” said Laura, pointing.

“Okay, in you go,” said Beth.

Laura studied the upper bunk, which looked unattainable. “How?” she faltered.

Beth laughed quietly. “Well, look,” she said. “Put your foot on the rung of the lower bunk—no, no wait!—that’s right,” she said, guiding her. “Now, get your knee on the rung of the bed next door. Now, just roll in. Whoops!” she said, catching Laura as she nearly lost her balance. She gave her a push in the right direction. Laura rolled awkwardly onto her bunk, laughing with Beth.

Beth climbed up where she could see her and said, “You’ll catch on, Laur. Doesn’t take long.” She helped Laura under the covers and tucked her in, and it was so lovely to let herself be cared for that Laura lay still, enjoying it like a child. When Beth was about to leave her, Laura reached for her naturally, like a little girl expecting a good-night kiss. Beth bent over her and said, “What is it, honey?”

With a hard shock of realization, Laura stopped herself. She pulled her hands away from Beth and clutched the covers with them.

“Nothing.” It was a small voice.

Beth pushed Laura’s hair back and gazed at her and for a heart-stopping moment Laura thought she would lean down and kiss her forehead. But she only said, “Okay. Sleep tight, honey.” And climbed down.

Laura raised herself cautiously on one elbow so she could watch her leave the dorm. Beth went out and shut the door and Laura was left to her strange cold bed in the great dark dormitory. She felt cut loose from reality.

It took her a long while to get to sleep. Her nerves were brittle as ice and they all seemed to be snapping from the day’s pressure. She lay motionless on her back and studied the luminous checkers on the ceiling, laid there through the window by the light of the fire escape. She though of Beth: Beth beside her watching her, whispering to her, reaching out to touch her.

The stillness grew and lengthened and Laura lay in it alone with her thoughts. Far away on the campus the clock on the Student Union steeple pulsed twelve times through the waiting night. Laura pulled her covers tight under her chin and tried to sleep. She was just drifting off when she heard someone stop by her bed and she opened her heavy eyes and saw Beth outlined by the night light.

“Still awake?” she whispered.

“I’m sorry. I’m dropping off now.” Laura felt guilty; caught with her eyes open when they should have been shut; caught peeking at nothing; caught thinking of Beth.

“Just wanted to make sure you were all right.”

“Oh, yes, thank you.”

“Shhh!” hissed someone from a neighboring bed.

“Sorry!” Beth hissed back, and then turned to Laura again.

“Okay, go to sleep now,” she said, and she gave Laura’s arm a pat.

“I will,” Laura whispered.

Two (#ulink_e4abfc7c-db52-5b5f-9e8a-53de2d2b5757)

At six forty-five, Laura heard a soft voice whispering, “Time to get up, Laura.” She sat up immediately in her bed as if pulled by a wire, and looked over to see an unusually pretty face staring up at her.

“Thank you,” she said.

The face smiled and whispered, “Wow, are you easy to wake up!” and moved away.

Laura had a good morning. She spent a lot of it wondering about her strange desire for a good-night kiss from Beth, and hoping Beth hadn’t understood her sudden aborted gesture. At lunchtime she sat with everybody in the big sunny dining room, talking while she ate. She glanced over at Beth, who sat two tables away from her, and found Beth returning the look. Laura answered her smile and turned, in confusion, to prospecting for nuggets of hamburger in her chili.

After lunch they studied together for a while. Laura sat down with her book in a large green butterfly chair in the corner and struggled to get comfortable. She was still trying to conform to the incomprehensible chair when Emily ran in from the washroom, grabbed her coat and a notebook, and ran out again. Seconds later she was back.

“Hey Beth, if Bud calls tell him I’ll see him at Maxie’s at four.”

Beth pulled her reading glasses down to the end of her nose and looked over them. “Right,” she said.

“Thanks.” And Emily was gone.

Beth stared after her, shaking her head and smiling a little.

“What?” said Laura.

“I just don’t get it. Or rather, I get it but I don’t like it. He’s too crazy for her. Emmy needs a steadying influence.” She winked at Laura and turned back to her book.

Laura began to glance furtively at her, half expecting her to be looking back, and she was rather disappointed when Beth kept her nose in the book. After a while Laura gazed openly at her, resentful of the book that claimed all Beth’s attention. And then she forgot the book and thought only of Beth….

The two girls walked to their afternoon class together. It was a brisk day, snappy and sunny and invigorating. Beth walked with long, smooth strides. She liked to walk and she walked well, as if she were really enjoying her legs; enjoying the rhythmic cooperation between legs and lungs, crisp weather, space and speed. She had a lusty health that almost intimidated Laura, who was breathless with trying to keep up. And breathless, too, with pleasure at walking beside Beth.

They arrived in class five minutes late, and the instructor had already started his lecture. He interrupted himself to note, while gazing out the window with a wry smile, “Glad you could make it, Miss Cullison.”

Beth, slipping out of her coat, looked up at him with a grin. They were friendly enemies, she and the teacher; they liked to catch each other slipping up somewhere.

“I see,” he added, “you’re leading the innocent astray.”

Laura blushed in confusion. It scared her to see someone flirt with authority as Beth did: she expected to see the hallowed rules and traditions crash down on Beth and crush her, and when they didn’t she was as surprised as she was relieved. To Laura, the things Beth said and did were daring in the extreme. To Beth, who knew herself and people better, it was just a half-hearted revolt; a small-scale protest that was more in fun than in earnest. She didn’t want to be an out-and-out character any more than she wanted to be one of the herd, so Beth beat herself a path between the two. Laura was happy, when she saw the letter was from her father, that Beth and Emily weren’t in the room. Her divorced parents were a faraway sorrow she tried to pretend out of existence. She opened the letter slowly.

“Glad to hear you like your new home,” she read. “I understand Alpha Beta is a pretty good sorority.”

Yes, father. Pretty good. If you say so. She hated the way her father phrased things.

“Anyway,” the letter went on, “they had a good house when I was in school. Your roommates sound like nice girls, especially the Cullison girl. That’s the kind of friendship you should cultivate, Laura, with people who can really do you some good. This girl sounds like a real go-getter—president of the Student Union and etc. That’s quite an honor for a girl, isn’t it? She can probably do a lot for you—get you into the right activities and so forth. I’d treat her well, if I were you.”

Laura sighed with exasperation over her father’s ideas of friendship; if it weren’t useful somehow it just wasn’t friendship, only a waste of time.

“By the way,” he continued, “Cliff Ayers’s son Charlie is in school down there. I’d like you to give him a call—he’d like to hear from you, I’m sure.”

Sure, thought Laura with resentment. He’d like to hear from Marilyn Monroe. But who’s Laura Landon? He won’t even remember the name.

“Cliff says Charlie looks just like him, which means there’s probably a line of girls ahead of you.”

Is that supposed to encourage me? Laura wondered bitterly. If Charlie Ayers wants to hear from me, which I doubt, he can call me himself.

“I understand that your mother has found herself a nice apartment. You will spend half the holidays with her and half with me, of course. I must say, Laura, you took the divorce pretty well, though of course I expected you to.”

Laura crushed the letter with angry hands and threw it into the wastebasket by the desk. Then she put her head down and wept, until she heard Beth and Emily coming down the hall. They found her dusting the already spotless coffee table and smiling at the job.

Beth looked at her oddly for a moment and then picked up a manila envelope and hurried out of the room. She would be at a committee meeting all evening long and left Laura and Emily to study in an embarrassed silence. Both of them wished rather uncomfortably that Beth would come back and mediate for them. After a while the dearth of words between them began to pall and they were both suddenly conscious that they would be roommates together for the rest of the year. It seemed an interminable length of time.

Emily could usually chatter easily with people. She was natural with them and they responded naturally to her. But every word and gesture of Laura’s seemed to her to be rehearsed, calculated to please, and it threw Emmy completely. She got the feeling that she could smash a bottle over Laura’s head and Laura would say, very calmly, “Thank you.”

There was plenty of room for Laura on the couch beside Emily, but she wouldn’t sit there, simply because Emily got there first. She sat down in the butterfly chair with a sigh. It defied her, as usual, and her narrow skirt made the problem worse. She shifted unhappily and Emily, trying to be helpful, suggested, “Why don’t you put your p.j.’s on, Laura? Much more comfortable. Besides, nobody studies in their clothes.”

Laura couldn’t think of an excuse to keep her clothes on and she got up to change, wondering if Emily just wanted to watch her undress. She performed the operation with determined casualness. Her set teeth wouldn’t show, but her manner would. Emily watched her on the sly, wondering why Laura was so embarrassed and self-conscious about herself.

“Hey, Laur, what a pretty bra!” she exclaimed spontaneously as Laura pulled it out from under her pajama shirt. “Let’s see it,” said Emily, reaching out a hand.

Laura gave it a jerky toss.

“Gee, nylon,” said Emmy. “They make ’em up just like this only padded, you know,” she added. “They’re terrific. Ever try ’em?”

“Falsies, you mean?” said Laura. The word struck her as mildly obscene.

“Yeah.”

“No, I never did.”

“You should,” said Emmy realistically. “They’re terrific, really. Nobody knows the difference. Unless you’re dancing awful close,” she amended.

“I guess my busts are kind of small,” said Laura.

Emily smiled at her, wondering at the pathetic modesty that made it impossible for Laura to call the parts of her body by their right names.

Laura’s small breasts bothered her. She would fold her arms over them as much to conceal their presence as to conceal their size. She wished that they were more glamorous, more obviously there. In their present shape they seemed only an afterthought.

She sat down with her book again when she was safely into her pajamas and Emily sat and toyed with things to say; she had made a start and she wanted to keep the communication line open. At nine o’clock she snapped her book shut and said, “How ‘bout some coffee, Laur?”

“No thanks,” said Laura, looking up from her book.

“Oh, come on. It won’t keep you awake. We’ve got a big jar of Sanka.” She pulled open Beth’s bottom dresser drawer and took out the jar, and Laura noted with displeasure her familiarity with Beth’s things. “Come on,” she said again. “I hate to go down alone.”

Laura gave in. She followed Emily down the back stairs to the kitchen.

“We have a coffee break almost every night,” said Emily tentatively. She lighted a cigarette and cast about for something new to say. Her perplexity made her pretty face quite appealing.

“Say, Laur,” she said cheerfully, “have you got a date this Saturday?” Emily was ready to be friends with Laura; she was willing to be friends with almost anybody. The best turn she could do Laura, as she saw it, was to fix her up with an acceptable male. Emmy knew dozens of them.

“No,” said Laura doubtfully. “But in pledge meeting they said something about getting me a date.” She thought with fleeting guiltiness of Charlie Ayers, and knew she would never call him; she hadn’t the guts and she hadn’t the desire.

“Oh. Well, they haven’t done it yet, have they?”

“Well, no, but—”

“Listen, Laura, there’s a terrific guy I’m thinking of—a fraternity brother of Bud’s. I could fix you up with him. Jim’s a junior, real tall.” And she went on to describe an irresistible young man. They are always irresistible until you’re face to face with them. Laura let Emmy talk her into it. She didn’t know any men and it seemed a good idea to let Emmy take care of the problem.

“Bud and I will be along the first time out,” said Emily, making plans. “It’s much easier to have somebody else along for moral support.” She laughed and Laura smiled with her. What she said was true enough. It might not be so bad.

“That sounds terrific,” she said, borrowing Emmy’s favorite adjective to amplify her gratitude. “If it wouldn’t be too much trouble for you.”

“Oh, Lord, no,” said Emily. She set one cup into another thoughtfully and went on, “Gee, I wish I could talk Beth into going out.”

Laura was suddenly alert. She turned and looked at Emily. “Doesn’t she go out?”

“Nope. Crazy girl.”

“Not at all?” Laura thought it was a requisite for sorority girls.

“No.” Emily stared quizzically at her sudden show of interest.

“I just thought—” Laura looked away in confusion. “I mean, she’s so popular and everything. I just naturally thought—well—” If a girl didn’t date was there anything wrong with her?

“Oh, she used to,” said Emmy, taking the steaming water from the burner and pouring it over the little mountains of dry coffee in the cups she had set out. “She used to go out a lot the first couple of years she was down here. But nothing ever happened, you know? Every time she got interested—sugar?”

Laura was so absorbed that it took her a minute to collect her wits and answer, “Yes, please.”

Emmy dropped it in and handed Laura her cup. “There’s no cream. There’s Pream, though. Want some?”

Laura wanted to shake Beth’s story out of her. “No, thanks,” she said briefly. “This is fine.” She was hungry for any crumb of information about Beth without stopping to wonder where her appetite came from. She was concerned only with satisfying it at this point.

Emily dipped into the Pream can with a spoon and sprinkled the white powder into her coffee. “You get used to it,” she said. “I didn’t used to like it, either.”

“Well, what happened?” said Laura in a voice that was urgent yet soft, as if the volume might excuse the words. She didn’t want to look interested.

“Oh … well,” Emmy stirred her concoction. “Nothing happened, really. In fact, that was the whole trouble. Nothing did happen.” She looked cautiously at Laura, as if trying to determine just how much she could be confided in. Laura’s face was a picture of sympathetic concern. “She’d find somebody she liked,” Emmy went on, “and they’d go together for a couple of months, and just when it seemed as if everything was going to be terrific, it was all over. I mean, Beth just called it off. She always did that,” she said musingly, “just when we all thought she was really falling in love. All of a sudden she’d call it quits.”

“Why?” said Laura.

Emily shrugged. “If you ask me, I think she just got scared. I think she’s afraid to fall in love, or something. It’s the only thing I can think of. Otherwise it just doesn’t make sense.”

“Were they nice boys?” Laura asked.

“Terrific boys! Some of them, anyway.”

“Well, didn’t she tell them why she dropped them? I mean, she must have told them something.” Laura was groping for the key to Beth’s character, for something to explain her with.

“Nope,” said Emily. “Just told ’em goodbye and that was it. Believe me, I know. I’ve had ’em call me by the dozens to cry on my shoulder. But she wouldn’t say much to me, either. She just said she got tired of them or it wouldn’t have worked out and it was best to end it now than later, or something.”

“And now she doesn’t go out any more?”

“Isn’t that something?” Emily clucked in disapproval. “You’d think she was disillusioned at the tender age of twenty-one. She puts on like she doesn’t care, but I know she does. But still, she did it to herself. After a while when the boys called up for dates she just turned ’em down automatically. As if she knew she wasn’t going to have any fun, no matter who she went with. As if it just wasn’t worth the trouble.”

Emily had lost Laura’s attention, but she didn’t know it. Laura was thinking to herself, She’s got a right not to care. Why should she care about boys? She doesn’t have to. Emmy doesn’t know everything.

“Of course,” Emmy went on, “she’s told me a thousand times she doesn’t want any man who’s afraid of her, and if they’re all afraid of her, to hell with them. I’m quoting,” she added, smiling. “She likes to swear.”

“I noticed,” said Laura a trifle primly.

“I don’t know where she got that idea,” Emmy said. “She says she won’t play little games with them just for the sake of a few dates. Well, you know men. What’s a romance without little games? I mean, let’s face it, there isn’t a man living who doesn’t want to play games.” She eyed Laura over her coffee cup and made her feel illogically guilty.

“Maybe she’s afraid of men,” said Laura. The words popped from her startled mouth like corks from a bottle. For a sickening minute she thought Emily was going to ask her questions or stare at her curiously, but Emily only laughed.

“Lord, she’s not afraid of anything,” she said. “It’s more the other way around. They’re afraid of her. She just needs a good man who doesn’t scare easy to get her back on the right track. Maybe we can find somebody for her,” and she smiled pleasantly at Laura.

Upstairs again, Laura settled into her malevolent butterfly chair and wondered why Emmy was so short-sighted. It struck her as rather fine and noble that Beth didn’t go out with men. It never occurred to her that Beth really might like men; without knowing why, without even thinking very seriously about it, she knew she didn’t want her to like them.

Laura was a naive girl, but not a stupid one. She was fuzzily aware of certain extraordinary emotions that were generally frowned upon and so she frowned upon them too, with no very good notion of what they were or how they happened, and not the remotest thought that they could happen to her. She knew that there were some men who loved men and some women who loved women, and she thought it was a shame that they couldn’t be like other people. She thought she would simply feel sorry for them and avoid them. That would be easy, for the men were great sissies and the women wore pants. Her own high school crushes had been on girls, but they were all short and uncertain and secret feelings and she would have been profoundly shocked to hear them called homosexual.

It would never have entered her mind to doubt that Beth was solidly normal, because Laura thought that she herself was perfectly normal and she wasn’t attracted to men. She thought simply that men were unnecessary to her. That wasn’t unusual; lots of women live without men.

What Laura would never know, and Beth would never tell her, was the real reason she had given up seeing men. Beth had, over and above most people, a strongly affectionate nature, a strong curiosity, and a strong experimental bent. She would give anything a first try, and morality didn’t bother her. Her own was mainly a comfortable hedonism. What she wanted she went after. At the time she met Laura, she wanted to be loved more than anything else.

Beth had always wanted to be loved. She wanted to feel, not to dream; to know, not to wonder. She started as a little girl, trying to win her aunt and uncle in her search for love. Loving them was like trying to love a foam-rubber pillow: they allowed themselves to be squeezed but they popped right back into shape when they were released.

Unknowingly, her aunt and uncle had started Beth on a long, anxious search for love. When she couldn’t find it with them she turned to others, and when she grew up she turned to men. It was the natural thing to do; it was inevitable. For Beth grew up to be a very pretty girl, and when she began looking for a man to satisfy her she found more than one always willing to try.

But none of them made it. First there was George, when she was still in high school. She was just fifteen and George was a Princeton man in his twenties. Beth liked them “older”; and the older ones liked her. George fell very much in love with her. He was fun, he had been places, he could take her out and show her a good time … and he adored her. Her word was law.

Beth administered the law for two years. The time began to drag interminably toward the end of the second year. George smothered her with love, and she began to doubt and to despise herself for not returning his passion. Here was real love, what she had always craved to make her life complete and meaningful, and what did it give her? A headache. George bored her.

It was in this mood that she gave herself to George. She was seventeen. George, on his knees, had implored her not to go to college; to stay at home and marry him and make him The Happiest Man in the World. She said, “No, George, I can’t.”

And he said, “Why?”

“Because I don’t love you.” Her heart rose in her throat, in fear and pity—fear for herself and pity for George.

George wept. He wept very eloquently. “I’ll kill myself,” he murmured in a misery so genuine that she began to fear for him, too.

“Oh, no, you mustn’t! You can’t!” she said. “Here, George. Come here, George.” She called him like a faithful spaniel, and he came, and let himself be petted. And very shortly he felt a sort of dismal passion rising in him with his self-pity; he began to sweat.

“Beth.” He said her name fiercely. “Look at me. Look what you’ve done to me.”

Beth gasped and then covered the lower part of her face with her hands so he couldn’t hear her laugh.

“Oh, George,” she whispered in a voice shaky with suppressed amusement. George took it very well; he thought her trembling voice was paying him tribute.

And suddenly Beth thought to herself very clearly, Oh, hell. Oh, the hell with it. She was quite calm and she said to George, “Come here.” Somewhere in the back of her mind was the hope that this would solve her problem, answer her questions, set things right. She might not love George, but at least she would discover the end of love. Next time she met a desirable man, she would know everything there was to know. She would be prepared and it would all be beautiful as nothing with George had been beautiful.

Beth unbuttoned her skirt and let it slip to the floor.

Hesitantly, with a flushed face and a nervous cough, George approached her. And in less than a minute they were on the couch together and Beth was learning about love.