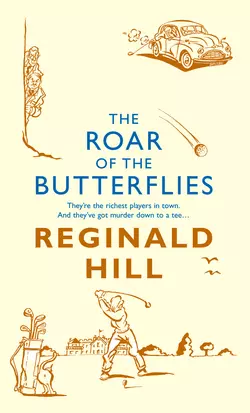

The Roar of the Butterflies

Reginald Hill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A special gift for Reginald Hill fans on Father’s Day – the return of Joe Sixsmith in a beautifully packaged, witty new crime novelA sweltering summer spells bad news for the private detective business. Thieves and philanderers take the month off and the only swingers in town are those on the 19th hole of the Royal Hoo Golf Course. But now the reputation of the ‘Hoo’ is in jeopardy.Shocking allegations of cheating have been directed at leading member, Chris Porphyry. When Chris turns to Joe Sixsmith, PI, he′s more than willing to help – only Joe hadn′t counted on being French-kissed then dangled out of a window on the same day.Before long, though, Joe’s on the trail of a conspiracy that starts with missing balls, and ends with murder…