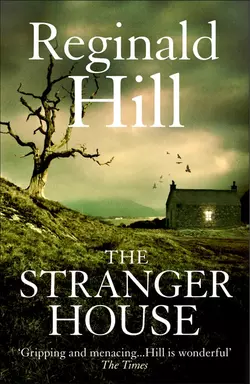

The Stranger House

Reginald Hill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1228.37 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A stunning psychological thriller set in Cumbria past and present, from the award-winning author of the Dalziel and Pascoe seriesThings move slowly in the tiny Cumbrian village of Illthwaite, but all that′s about to change.Post-grad Sam Flood and historian Miguel Mercado first meet at The Stranger House, Illwaithe’s local inn. Sam is there to find information on her grandmother, who left four decades before, while Mig’s research stretches back to the English Reformation, four centuries ago.The pair have nothing in common, yet their paths become increasingly entangled as they pursue their separate quests. Together they will discover who to trust and who to fear in this ancient village where the inhabitants are determined to keep the past buried.