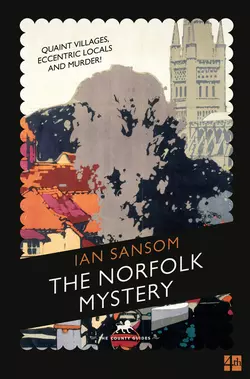

The Norfolk Mystery

The Norfolk Mystery

Ian Sansom

The first book in The County Guides - introducing an exciting new detective series.The County Guides are a series of detective novels set in 1930s England.The books are an odyssey through England and its history.In each county, the protagonists – Stephen Sefton, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, and his employer, the People's Professor, Swanton Morley – solve a murder.The first book is set in Norfolk. The murder is in the vicarage.There are 39 books – and 39 murders – to follow.

Copyright (#ulink_0e0c0c2e-123f-5e99-a61f-597772c041eb)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This ebook first published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2013

Copyright © Ian Sansom 2013

Cover image © Science & Society Picture Library / Getty Images

Ian Sansom asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007360482

Ebook Edition © June 2013 ISBN: 9780007360499

Version: 2017-11-03

Dedication (#ulink_3beaf615-72cb-5c14-873b-e919b3403890)

For my parents

Contents

Cover (#u0869d604-490e-50ba-a1ee-bbadb5cd46a5)

Title Page (#u3a4b2163-4f89-51d6-8a6e-8b345cb7d074)

Copyright (#u38843094-e3a6-56f2-bc1a-6fdffe4b0a23)

Dedication (#u1ac6335c-adf8-59cf-9160-892ba2c7f66a)

Chapter One (#u89be2cf8-46a6-522f-a120-0e47b102d669)

Chapter Two (#u490440c3-2092-5bcc-ad0e-145181af4db8)

Chapter Three (#uf32ebce9-7646-53fc-9a87-e929760ec498)

Chapter Four (#u49f400a5-ab66-5018-9397-27daaed71db2)

Chapter Five (#u3899c231-4183-547f-ba8f-3cc9be666209)

Chapter Six (#u9064ca49-8c74-5162-add1-9d814782df6f)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Ian Sansom (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_5eabd589-acb0-59d1-b73d-f3de579d18e7)

REMINISCENCES, of course, make for sad, depressing literature.

Nonetheless. Some stories must be told.

In the year 1932 I came down from Cambridge with my poor degree in English, a Third – what my supervisor disapprovingly referred to as ‘the poet’s degree’. I had spent my time at college in jaunty self-indulgence, rising late, cutting lectures, wandering round wisteria-clad college quadrangles drinking and carousing, occasionally playing sport, and attempting – and failing – to write poetry in imitation of my great heroes, Eliot, Pound and Yeats. I had grand ambitions and high ideals, and absolutely no notion of exactly how I might achieve them.

I certainly had no intention of becoming involved in the exploits and adventures that I am about to relate.

By late August of 1932, recovering at last from the long hangover of my childhood and adolescence, and quite unable, as it turned out, to find employment suited to my ambitions and dreams, I put down my name on the books of Messrs Gabbitas and Thring, the famous scholastic agency, and so began my brief and undistinguished career as a schoolmaster.

I shall spare the uninitiated reader the intimate details of the life of the English public school: it is, suffice it to say, a world of absurd and deeply ingrained pomposities, and attracts more than its fair share of eccentrics, hysterics, malcontents and ne’er-do-wells. At Cambridge I had been disappointed not to meet more geniuses and intellectuals: I had foolishly assumed the place would be full to the brim with the brightest and the best. As a lowly schoolmaster in some of the more minor of the minor public schools, I now found myself among those I considered to be little better than semi-imbeciles and fools. After grim stints at Arnold House, Llandullas and at the Oratory in Sunning – institutions distinguished, it seemed to me, only by their ability to render both their poor pupils and their odious staff ever more insensitive and insensible – I eventually found myself, by the autumn of 1935, in a safe berth at the Hawthorns School in Hayes. This position, though carrying with it all the usual and tiresome responsibilities, was, by virtue of the school’s location on the outskirts of London, much more congenial to me and afforded me the opportunity to reacquaint myself with old friends from my Cambridge days. Some had drifted into teaching or tutoring; some had found work with the BBC, or with newspapers; a lucky few had begun to make their mark in the literary and artistic realms. Those around me, it seemed, were flourishing: they rose, and rose.

I was sinking.

After leaving Cambridge I had, frankly, lost all direction, purpose and motivation. At school I had been prepared for varsity: I had not been prepared for life. After Cambridge I had given up on my poetry and became lazier than ever in my mental habits, frequenting the cinema most often to enjoy only the most vulgar and the gaudiest of its productions: The Black Cat, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Tarzan and His Mate. Where once I had immortal longings my dreams now were mostly of Claudette Colbert. I had also become something of an addict of the more lurid work of the detective novelists – a compensation, no doubt, for the banalities of my everyday existence. The air in the pubs around Fitzrovia in the mid-1930s, however, was thick with talk of Marx and Freud and so – if only to impress my friends and to try to keep up – I gradually found myself returning to more serious reading. I read Mr Huxley, for example – his Brave New World. And Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses. Strachey’s The Coming Struggle for Power. Malraux’s La Condition Humaine. These were books in ferment, as we were: these were the writers who were dreaming our wild and fantastic dreams. I began to attend meetings in the evenings. I distributed pamphlets. I frequented Hyde Park Corner. I read the Daily Worker. I came under the sway of, first, Aneurin Bevan and, then, Harry Pollitt.

I joined the Communist Party.

In the party I had found, I believed, an outlet and a home. I devoured Marx and Engels – slowly, and in English. I was particularly struck by a phrase from the Communist Manifesto, which I carefully copied out by hand and taped above my shaving mirror, the better to excite and affront myself each morning: ‘Finally, as the class struggle nears its decisive stage, disintegration of the ruling class and the older order of society becomes so active, so acute, that a small part of the ruling class breaks away to make common cause with the revolutionary class, the class which holds the future in its hands.’ After years as a pathetic Mr Chips, conducting games, leading prayers and encouraging the work of the OTC, I was desperate to hold the future, any future, in my hands.

And so, in October 1936 I left England and the Hawthorns for Barcelona and the war.

I arrived in Spain in what I now recognise as a kind of fever of idealism. I eventually returned to England almost twelve months later in turmoil, confusion and in shock. Although I had read of the great movement of masses and the coming revolution, in Spain I saw it for myself. I had long taught my pupils the stories of the great battles and the triumphs of the kings and queens of England, the tales of the Christian martyrs, and the epic poetry of Homer, the tragedies of Shakespeare. I now faced their frightful reality.

Even now I find I am able to recall incidents from the war as if they happened yesterday, though they remain strangely disconnected in my mind, like cinematic images, or fragments of what Freud calls the dreamwork. From the first interview at the party offices on King Street – ‘So you want to be a hero?’ ‘No.’ ‘Good. Because we don’t need bloody heroes.’ ‘So are you a spy?’ ‘No.’ ‘Are you a pawn of Stalin?’ ‘No.’ ‘What are you then?’ ‘I am a communist’ – to arriving in Paris, en route, early in the morning, sick, hung over, shitting myself with excitement in the station toilets, shaking and laughing at the absurdity of it. And then the first winter in Spain, shell holes filled to the brink with a freezing crimson liquid, like a vast jelly – blood and water mixed together. And in summer, coming across a farm where there were wooden wine vats, and climbing in and bathing in the cool wine, while the grimy, fat, terrified farmer offered his teenage daughters to us in exchange for our not murdering them all. In a wood somewhere, in the bitter cold spring of 1937, staring at irises and crocuses poking through the dark mud, and thinking absurdly of Wordsworth, the echoing sound of gunfire all around, wounded men passing by, strapped to the back of mules. The taste of water drunk from old petrol tins. The smell of excreta and urine. Olive oil. Thyme. Candle grease. Cordite. Endless sleeplessness. Lice. The howling winds. The sizzling of the fat as we make an omelette in a large, black pan over an open fire, cutting it apart with our knives. Gorging on a field of ripe tomatoes. The Spanish rain. The hauling of the ancient Vickers machine guns over rocky ground.

And, of course, the dead. Everywhere the dead. Corpses laid out at the side of the road, the sight and smell of them like the mould on jam, maggots alive everywhere on their bodies. Corpses with their teeth knocked out – with the passing knock of a rifle butt. Corpses with their eyes pecked out. Corpses stripped. Corpses disembowelled. Corpses wounded, desecrated and disfigured.

In a year of fighting I was myself responsible for the murder of perhaps a dozen men, many of them killed during an attack using trench mortars on a retreating convoy along the Jaca road in March, May 1937? There was one survivor of this atrocity who lay in the long grass by the road, calling out for someone to finish him off. He had lost both his legs in the blast, and his face had been wiped away with shrapnel; he was nothing but flesh. A fellow volunteer hesitated, and then refused, but for some reason I felt no such compunction. I acted neither out of compassion nor in rage – it was simply what happened. I shot the poor soul at point-blank range with my revolver, my mousqueton, the short little Mauser that I had assembled and reassembled from the parts of other guns, my time with the OTC at the Hawthorns School having stood me in good stead. To my shame, I must admit not only that I found the killing easy, but that I enjoyed it: it sickened me, but I enjoyed it; it made me walk tall. I felt for the first time since leaving college that I had a purpose and a role. I felt strong and invincible. I had achieved, I believed, the ultimate importance. I was like a demi-god. A saviour. I had become an instrument of history. The Truly Strong Man.

I was, in fact, nothing but a cheap murderer.

I was vice triumphant.

Soon after, I was wounded – shot in the thigh. We had been patrolling a no-man’s-land at night, somewhere near Figueras. We were ambushed. There was confusion. Men running blindly among rocks and trees. At the time, the strike of the bullet felt to me as no more than a slight shock, like an insect bite, or an inconvenience. The pain, unspeakable, came later: the feeling of jagged metal inside you. Indescribable. I was taken in a convoy of the wounded to a hospital, no more than a series of huts that had once been a bicycle workshop, requisitioned from the owners, where men lay on makeshift beds, howling and weeping, calling out in a babel of languages, row upon row of black bicycle frames and silver wheels hanging down above us, like dark mechanical angels tormenting our dreams. I was prescribed morphine and became delirious with nightmares and night sweats. Weeks turned into months. Eventually I was transferred to Barcelona, and then by train to France, and so back home to England, beaten, and limping like a wounded animal.

The adventure had lasted little more than a year.

It seemed like a lifetime.

Ironically, on returning from Spain, I found myself briefly popular, hailed by friends as a hero, and by idling fellow travellers as their representative on the Spanish Front. There were grand luncheons, at Gatti’s in the Strand, and speaking engagements in the East End, wild parties at Carlton House Terrace, late night conversations in the back rooms of pubs – a disgusting, feverish gumping from place to place. Unable to comprehend exactly what had happened to me, I spoke to no one of my true experiences: of the vile corruption of the Republicans; the unspeakable coarseness and vulgarity of my fellow volunteers; the thrill of cowardly murder; my privileged glimpse of the future. I spoke instead as others willed me to speak, pretending that the war was a portent and a fulfilment, the opening salvo in some glorious final struggle against the bourgeois. Lonely and confused, attempting to pick up my life again, I ran, briefly, a series of intense love affairs, all of them with unsuitable women, all of them increasingly disagreeable to me. One such relationship was with a married woman, the wife of the headmaster of the Hawthorns, where I had returned to teach. We became deeply involved, and she began to nurture ideas of our fleeing together and starting our lives again. This proposed arrangement I knew to be not merely impossible but preposterous, and I broke off the relationship in the most shaming of fashions – humiliating her and demeaning myself. There was a scandal.

I was, naturally, dismissed from my post.

What few valuable personal belongings and furnishings I possessed – my watch, some paintings, books – I sold in order to fund my inevitable insolvency, and to buy drink. A cabin trunk I had inherited from my father, my most treasured possession – beautifully crafted in leather, and lined in watered silk, with locks and hinges of solid brass, my father’s initials emblazoned upon it, and which had accompanied me from school to Cambridge and even on to Spain – I sold, in a drunken stupor, to a man in a pub off the Holloway Road for the princely sum of five shillings.

I had become something utterly unspeakable.

I was not merely an unemployed private school master.

I was a monster of my own making.

I moved into temporary lodgings in Camden Town. My room, a basement below a laundry, was let to me furnished. The furnishings extended only to a bed, a small table and a chair: it felt like a prison cell. Water ran down the walls from the laundry, puddling on the floor and peeling back the worn-out linoleum. Slugs and insects infested the place. At night I tried writing poems again, playing Debussy, and Beethoven’s late quartets and Schubert’s Winterreise – in a wonderful recording by Gerhard Hüsch, which reduced me to tears – again and again and again on my gramophone to drown out the noise of the rats scurrying on the floor above.

I failed to write the poems.

I sold the Debussys, and the Beethovens and Gerhard Hüsch singing Schubert.

And then I sold the gramophone.

During my time in Spain a shock of my hair had turned a pure white, giving me the appearance of a badger, or a skunk: with my limp, this marking seemed to make me all the more damaged, like a shattered rock, or a sliver of quartz; the mark of Cain. I had my hair cropped like a convict’s and wore thin wire-rimmed spectacles, living my days as a hero-impostor, and my nights in self-lacerating mournfulness. Sleep fled from me. I found it impossible to communicate with friends who had not been to Spain, and with those who had I felt unable to broach the truth, fearing that my experiences would not correspond to their own. Milton it was – was it not? – who was of the opinion that after the Restoration the very trees and vegetation had lost heart, as he had, and had begun to grow more tardily. I came to believe, after my return from Spain, that this was indeed the case: my food and drink tasted bitter; the sky was filled with clouds; London itself seemed like a wilderness. Everything seemed thin, dead and grey.

I covered up my anxieties and fears with an exaggerated heartiness, drinking to excess until late at night and early into the morning, when I would seek out the company of women, or take myself to the Turkish Baths near Exmouth Market, where the masseur would pummel and slap me, and I could then plunge into ice-cold waters, attempting to revive myself. A drinking companion who had returned from America provided me with a supply of Seconal, which I took at night in order to help me sleep. I had become increasingly sensitive to and tormented by noise: the clanging and the banging of the city, and the groaning and chattering of people. I could nowhere find peace and quiet. During the day I would walk or cycle far out of London into the country, wishing to escape what I had become. I would picnic on bread and cheese, and lie down to nap in green fields, where memories of Spain would come flooding back to haunt me. I bound my head with my jacket, the sound of insects disturbed me so – like fireworks, or gunfire. I was often dizzy and disoriented: I felt as though I were on board ship, unable to disembark, heading for nowhere. I took aspirin every day, which unsettled my stomach. Some nights I would sleep out under the stars, in the shelter of the hedges, lighting a fire to keep me warm, begging milk from farmers and eating nuts and berries from the hedgerow. The world seemed like nothing more than a vast menacing ocean, or a desert, and I had become a nomad. Sometimes I would not return to my lodgings for days. No one noted my absences.

Near Tunbridge Wells one day, in Kent, I retreated to the safety of a public library to read The Times – something to distract me from my inner thoughts. Which was where I saw the advertisement, among ‘Appointments & Situations Vacant’:

Assistant (Male) to Writer. Interesting work; good salary and expenses; no formal qualifications necessary; applicants must be prepared to travel; intelligence essential. Write, giving full particulars, BOX E1862, The Times, E.C.4.

I had, at that moment, exactly two pounds ten shillings to my name – enough for a few weeks’ food and rent, maybe a month, a little more, and then …

I believed I had already engineered my own doom. There was no landfall, only endless horizon. I foresaw no future.

I applied for the job.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_baf526ba-e708-5bb0-8ebf-a8beca92a846)

THE INTERVIEW for the post took place in a private room at the Reform Club. If I were writing a novel I should probably at this point reveal to the reader the name of my prospective employer, and the reasons for his seeking an assistant. But since I intend to make this as true an account as I can make it of what occurred during our time together, I shall content myself with gradually revealing the facts as they revealed themselves to me. I had, I should stress, absolutely no knowledge during the course of my interview of the nature of the employment to follow. If I had, I would doubtless have scorned it and thus played no part in the strange episodes and adventures that were once world-renowned but which are now in danger of being forgotten.

I arrived at the Reform Club in good time and was shown to the room where the interview was to be conducted. The last time I’d attended an interview was at the party offices on King Street, when I’d had to convince them I wanted to join the British Battalion and go to Spain. That experience had been merely chastening. This was much worse.

Several young men were already seated outside the room, like passengers at a railway station, or patients awaiting their turn – all of them solid, dense sort of chaps, one of them in an ill-fitting pinstripe suit consulting notes; another, his hair over-slick with brilliantine, staring unblinkingly before him, as though trying to overcome the threat of terrible pain. In my tin spectacles and blue serge suit I appeared a degenerate in comparison, like a beggar, or a music-hall turn. One by one we were called into the interview room. Waiting, I found myself quietly dozing, as had become my habit due to my sleeplessness at night, and dreaming uncomfortably of Spain, of sandy roads lined with trucks carrying displaced persons, of the bodies and the blazing sun.

I was jerked awake, shaken by the man in the pinstriped suit.

‘Good luck,’ he said as he hurried away, still clutching his notes. He looked shell-shocked.

I was the last to be interviewed. I knocked and entered.

The room was a panelled study reminiscent of my supervisor’s rooms at college, a place where I had known only deep lassitude, and the smell of pipe tobacco. Heavy damask curtains were drawn across the windows, even though it was not yet midday, and gas lamps burned, illuminating the room, which seemed to have been established as some kind of operational headquarters, a sort of den, or a dark factory of writing. There were reams of notepaper and envelopes of various types stacked in neat piles on occasional tables by the main desk, and stacks of visiting cards, a row of shining, nickel-sheathed pencils laid out neatly, and a selection of pens, and a staple press, and paper piercers, a stamp and envelope damper, an ink stand, loose-leaf manuscript books, table book-rests crammed with books, and various scribbling and memo tablets. The whole place gave off a whiff of ink, beeswax, hard work, tweed and … carbolic soap.

A man was seated at the main desk, typing at a vast, solid Underwood, several lamps lit around him like beacons, with dictionaries and encyclopedias stacked high, as a child might build a fortress from wooden blocks. He glanced up at me briefly over the typewriter and the books, long enough to recognise my presence and to register, I thought, his disapproval, and then his eyes returned to his work. He was, I guessed, in his late fifties, with white, neatly trimmed hair, and a luxuriant moustache in the Empire manner. He wore a light grey suit and a polka-dot bow tie, which gave him the appearance rather of a medical doctor or, I thought – the tapping of the keys of the typewriter perhaps – of a bird. A woodpecker.

‘Sit,’ he said. His voice was pleasant, like an old yellow vellum – the voice of a long-accomplished public speaker. It was a voice thick with the authority of books. I sat in the leather armchair facing the desk.

From this position I could see him cross and uncross his legs as he sat at the table. He had improvised for himself, I noted, as a footrest a copy of Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, illustrated with armorial bearings – half-calf, well rubbed – his restless feet jogging constantly upon it. He wore a pair of highly polished brown brogue boots of the kind gentlemen sometimes wear for country pursuits; it was almost as if he were striding through his typing, the sound of which filled the room like gunfire. He continued to type and did not speak to me for what seemed like a long time, yet I did not find this curious silence at all unsettling, for what somehow emanated from him was a sense of complete calm and control, of light, even, a quality of personality of the kind I had occasionally encountered at Cambridge, and in Spain, among both men and women of all classes and types, a personality of the sort I believe Mr Jung calls the ‘extravert’, a character somehow unshadowed as many of us are shadowed, someone fully realised and confident, completely present, blazing. Another word for this kind of determining character, I suppose, is ‘charisma’, and my interviewer, whether knowing it or not, seemed to epitomise this elusive and much prized quality. He had ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ is – something more than a twinkle in the eye. He also seemed, I have to admit, deeply familiar, but I could not at this stage have identified him precisely.

‘You are?’ he asked, in a momentary pause from his labours.

‘Stephen Sefton.’

He glanced at what I assumed were my employment particulars set out on the top of a pile of papers by his right elbow.

‘Sefton. Apologies. Must finish an article,’ he said. He had a large egg-timer beside the Underwood, whose sands were fast running out. ‘Two minutes till the post.’

‘I see,’ I said.

‘You can type?’ he asked, continuing himself to beat out a rhythm on the keys.

‘Yes.’

Rattle.

‘Shorthand?’

Ping.

‘I’m afraid not, sir, no.’

‘I see. Too much of a’ – carriage return – ‘hoity-toity?’

‘No, sir, I don’t think so.’

Rattle. ‘You’d be prepared to learn, then?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Good.’ Back space.

‘Photography. You can handle a camera?’

‘I’m sure I could try, sir.’

‘Hmm. And Cambridge, wasn’t it? Christ’s College.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Ping.

‘Which makes you rather over-qualified for this position.’

‘Sorry, sir.’

Rattle.

‘No need to apologise. It’s just that none of the other candidates has been blessed with anything like your educational advantages, Sefton.’ Carriage return.

‘I have been very … lucky, sir.’

‘Not a varsity type among them.’

‘I see, sir.’

Ping.

‘Curious. Perhaps you can tell me about it.’

‘About what, sir?’

‘What went wrong.’

‘What went wrong? I … I don’t know what went wrong.’

‘Clearly. Well, tell me about the college then, Sefton.’

‘The college?’

‘Yes. Christ’s College. I am intrigued.’

‘Well, it was very … nice.’

‘Nice?’

He paused in his typing and peered dimly at me in a manner I later came to recognise as a characteristic sign of his disbelief and despair at another’s complete ignorance and lack of effort. ‘Come on, man. Buck up. You can do better than that, can’t you?’

I was uncertain as to how to respond.

‘I certainly enjoyed my time there, sir.’

‘I believe you did enjoy your time at college, Sefton. Indeed, I see by your abysmal degree classification that you may have enjoyed your time there rather more than was advisable.’

‘Perhaps, sir, yes.’

‘Too rich to work, are we?’

‘No, sir,’ I replied. I was not, in fact, rich at all. My parents were dead. The family fortune, such as it was, had been squandered. I had inherited only cutlery, crockery, debts, regrets and memories.

He looked at me sceptically. And then tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, and then a final and resounding tap as the sands of the timer ran out. A knock came at the door.

‘Eleven o’clock post,’ said my interviewer. ‘Enter!’

A porter entered the dark room as my interviewer peeled the page he had been typing from the Underwood, shook it decisively, folded it twice, placed it in an envelope, sealed it and handed it over. The porter left the room in silence.

My interviewer then checked his watch, promptly upended his egg-timer – ‘Fifteen minutes,’ he said – sat back in his chair, stroked his moustache, and returned to the subject we had been discussing as if nothing had occurred.

‘I was asking about the history of the college, Sefton.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know much about the history, sir.’

‘It was founded by?’

‘I don’t know, sir.’

‘I see. You are interested in history, though?’

‘I have taught history, sir, as a schoolmaster.’

‘That’s not the question I asked, though, Sefton, is it?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Schooled at Merchant Taylors’, I see.’ He brandished my curriculum vitae before him, as though it were a piece of dubious evidence and I were a felon on trial.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Never mind. Keen on sports?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘No time for them myself. Except perhaps croquet. And boxing. Greyhound racing. Motor racing. Speedway. Athletics … They’ve ruined cricket. And you fancy yourself as a writer, I see?’

‘I wouldn’t say that, sir.’

‘It says here, publications in the Public Schools’ Book of Verse, 1930, 1931 and 1932.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘So, you’re a poet?’

‘I write poetry, sir.’

‘I see. The modern stuff, is it?’

‘I suppose it is, sir. Yes.’

‘Hm. You know Wordsworth, though?’

‘Yes, sir, I do.’

‘Go ahead, then.’

‘Sorry, sir, I don’t understand. Go ahead with what?’

‘A recitation, please, Sefton. Wordsworth. Whatever you choose.’

And he leaned back in his chair, closed his eyes, and waited.

It was fortunate – both fortunate, in fact, and unfortunate – that while at Merchant Taylors’ I had been tutored by the late Dr C.T. Davis, a Welshman and famously strict disciplinarian, who beat us boys regularly and relentlessly, but who also drummed into us passages of poetry, his appalling cruelty matched only by his undeniable intellectual ferocity. If a boy failed to recite a line correctly, Davis – who, it seemed, knew the whole of the corpus of English poetry by heart – would literally throw the book at him. There were rumours that more than one boy had been blinded by Quiller-Couch’s Oxford Book of English Verse. I myself was several times beaten about the ears with Tennyson and struck hard with A Shropshire Lad. By age sixteen, however, we victim-beneficiaries of Dr Davis’s methods were able to recite large parts of the great works of the English poets, as well as Homer and Dante. We had also, as a side effect, become enemies of authority, our souls spoiled and our minds tainted for ever with bitterness towards serious learning. But no matter. At my interviewer’s prompting I began gladly to recall the beginning of the Prelude, as familiar to me as a popular song:

Oh there is blessing in this gentle breeze,

A visitant that while it fans my cheek

Doth seem half-conscious of the joy it brings

From the green fields, and from yon azure sky.

These words seemed to please my interviewer – as much, if not more so than they would have done Dr Davis himself – for he leaned forward across the Underwood and joined me in the following lines:

Whate’er its mission, the soft breeze can come

To none more grateful than to me; escaped

From the vast city, where I long had pined

A discontented sojourner: now free,

Free as a bird to settle where I will.

He then fell silent as I continued.

What dwelling shall receive me? in what vale

Shall be my harbour? underneath what grove

Shall I take up my home? and what clear stream

Shall with its murmur lull me into rest?

The earth is all before me. With a heart

Joyous, nor scared at its own liberty,

I look about; and should the chosen guide

Be nothing better than a wandering cloud,

I cannot miss my way. I breathe again!

‘Very good, very good,’ pronounced my interlocutor, waving his hand dismissively. ‘Now. Canada’s main imports and exports?’

This sudden change of tack, I must admit, threw me entirely. I rather thought I had hit my stride with the Wordsworth. But it seemed my interviewer was in fact no aesthete, like our beloved Dr Davis, nor indeed a scrupuland like the loathed Dr Leavis, the man who had quietly dominated the English School at Cambridge while I was there, with his thumbscrewing Scrutiny,and his dogmatic belief in literature as the vital force of culture. Poetry, I had been taught, is the highest form of literature, if not indeed of human endeavour: it yields the highest form of pleasure and teaches the highest form of wisdom. Yet poetry for my interviewer seemed to be no more than a handy set of rhythmical facts, and about as significant or useful as a times table, or a knowledge of the workings of the internal combustion engine. I had of course absolutely no idea what Canada’s main imports and exports might be and took a wild guess at wood, fish and tobacco. These were not, as it turned out, the correct answers – ‘Precious metals?’ prompted my interviewer, as though a man without knowledge of such simple facts were no better than a savage – and the interview took a turn for the worse.

‘Could you give ten three-letter nouns naming food and drink?’

‘Rum, sir?’

‘Rum?’ My interviewer’s face went white, to match his moustache.

‘Yes.’

‘Anything else, Sefton – anything apart from distilled and fermented drink?’

‘Cod?’

‘Yes.’

‘Eel?’

‘Satisfactory, if curious choices,’ my interviewer concluded. ‘You might more obviously have had egg or pea.’

‘Or pig, sir?’

‘A pig, I think you’ll agree, is an animal, Sefton. It is not a foodstuff until it has been butchered and made into joints. A pig is potential food, is it not?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Tell me, Sefton, are you able to adapt yourself quickly and easily to new sets of circumstances?’

‘I believe I am sir, yes.’

‘And could you give me an example?’

I suggested that in my work as a schoolmaster I had encountered numerous occasions when I had been required to adapt to circumstances. I did not explain that one such occasion was when I had been found in a compromising situation with the headmaster’s wife. Fortunately, my interviewer did not ask for further elaboration and we returned promptly to questions of more import: the lives of the saints; folk customs; Latin tags; the classification of plants and animals. During the conversation he would glance concernedly at the egg-timer on his desk and thrum his fingers on the table, as though batting against time itself.

‘You seem to have a reasonably well-stocked mind, Sefton.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘As one would expect. Languages?’

‘French, sir. Latin. Greek. German. Some Spanish.’

‘Yes. I see you were in Spain.’

‘I was, sir.’

‘A Byron on the barricades?’

‘I never considered myself as such, no, sir.’

‘No pasaran.’

‘That’s correct, sir.’

‘Unable to fight in Spain, I learned Spanish instead.’

We spoke for a few minutes in Spanish, my interviewer remarking in a rudimentary way upon the weather and enquiring about the prices of rooms in hotels.

‘Your Spanish is certainly satisfactory, Sefton,’ he said. ‘Good. Do you have any questions about the position?’

‘Yes, sir.’

My main question, naturally, was what the position was and what it might entail – I still had no clear idea. I cleared my throat and tried to formulate the question in as inoffensive a manner as possible. ‘I wondered, sir, exactly what it might … entail, working as your assistant?’

My interviewer looked at me directly and unguardedly at this point, in a way that made me feel exceedingly uncomfortable. He had a way of looking at you that seemed violently frank, as though willing you to reveal yourself. And when he spoke he lowered his voice, as though confiding a secret.

‘Well, Sefton. I hope I can be honest with you?’

‘By all means, sir.’

‘Good.’ He carefully fingered his moustache before going on. The light of the lamps was reflected in his eyes. ‘I believe, Sefton, that there is a terrible darkness deepening all around us. We face not un mauvais quart d’heure, Sefton, but something more serious. Do you understand what I am saying?’

‘I think so, sir.’

I was not at all sure in fact if the serious darkness he was referring to was the darkness I had encountered in Spain, and which haunted me in my dreams, or if it were some other, ineffable darkness of a kind with which I was not familiar.

‘I think perhaps you do see, Sefton.’ He stared hard at me, as though attempting to penetrate my thoughts, his voice gradually rising in volume and pitch. ‘Anyway. It is my intention to shed some light while I may.’

‘I see, sir.’

‘I hope that you do, Sefton. It has been my life’s work. What I see around me, Sefton, is the world as we know it rapidly disappearing: the food we eat; the work we do; the way we talk; the way we consort ourselves. Everything changing. All of it about to go, or gone already: the miller, the blacksmith, the wheelwright. Destroyed by the rhythms of our machine age.’ He paused again to stroke his moustache. ‘It has been my great privilege, Sefton, in my career to visit the great countries and cities of the world: Paris, Vienna, Rome. I intend my last great project to be about our own enchanted land.’

‘England, sir.’

‘Precisely. The British Isles, Sefton. These islands. The archipelago. Before they disappear completely.’

‘Very good, sir.’

He fell silent, staring into the middle distance.

I felt that my question about the job had not been answered entirely or clearly, and realised I might need to prompt him for a more direct answer. ‘And what exactly would the person appointed by you be required to do, sir, on your … project?’

‘Ah. Yes. What I need, Sefton, is someone to write up basic copy that I shall then jolly up and make good. The person appointed would also be required to make arrangements for travel and accommodation, and to assist me in all aspects of my researches on the project as I see fit.’

‘I see, sir.’

‘I shan’t give you a false impression of my daily rounds, Sefton. There is no glamour. It is tiresome work requiring long hours, endurance and determination.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘And do you think you’re up to such a task?’

‘I believe so, sir.’

‘Are you married, Sefton?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Engaged to be married?’

‘No, sir.’

‘A homosexual?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Pets?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Good. We’ve plenty of those already. You don’t mind dogs?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Terriers?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Cats?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Birds?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Aversions or allergies to any kind of animals?’

‘Not that I know of, sir.’

‘And you are not in current employ?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Good. So you’d be able to start immediately?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Very well.’

My curiosity had certainly been piqued by my interviewer’s description of his enterprise, but after several rounds of questioning I was still keen to know more about the details. I made one more bid for clarity. ‘Can I ask, sir, exactly what the project is to be?’

‘The project?’ He sounded surprised, as though the nature of his work was widely known. ‘A series of books, Sefton, called The County Guides. A complete series of guides to the counties of England.’

‘All of them, sir?’

‘Indeed.’

‘How many counties are there?’

‘Schoolmaster, aren’t we, Sefton?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, then? Let me ask you the question: how many counties are there?’

‘Forty? thirty-nine?’

‘Thirty-nine. Exactly.’

‘So, thirty-nine books?’

‘We may also include the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey, Sefton. In which case there shall be forty-one.’

‘An … ambitious project then, sir.’ It struck me, in fact, not so much as ambitious as the very definition of folly.

‘In a life, Mr Sefton, of finite duration I can’t imagine why anyone would wish to embark on any other kind of project. Can you?’

‘No, sir.’

‘I intend the County Guides as nothing less than the new Domesday Book. I shall be going out into England with my assistant to find all the good things and to put them down.’

‘Only the good, sir?’

‘The books are intended as a celebration, yes, Sefton.’

‘Works of … selective amnesia, then, sir?’

My interviewer frowned deeply at this untoward remark. ‘Among those I would call the “not-so-intelligentsia”, Sefton, I know there to be an inclination to talk down our great nation. Are you one such down-talker?’

‘I like to think I’m a realist, sir.’

‘As am I, Sefton, as am I. Which is why I am undertaking this project. You may wish to reflect, sir, that you are of a generation that may live to see the year 2000, from which distant perspective you will be viewing a nation doubtless very different from that which you see around you now. It is my desire merely to set down a record of this place before its roots are cut and its sap drained, and the ancient oaks are felled once and for all. I do not wish England – our England – to be unknown by future generations. Do you understand, Sefton?’

‘I think so, sir.’

‘Good.’ He shifted in his seat and he glanced around the room, as though someone were among us. ‘Because I believe I can feel the chilly hand of fate coming upon us, Sefton. The County Guides I hope shall be clarion calls: they may be memorials.’ He paused momentarily for reflection upon this profundity.

‘And how long do you imagine this great enterprise will take, sir?’

‘I intend to have completed the series by the end of the decade, Sefton.’

‘By 1940?’

‘1939 I think you’ll find marks the end of the decade, Sefton. 1940 forms a part of the next, surely?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘So, 1939’s our deadline.’

‘A book on every county? By 1939?’

‘On every county, yes, Sefton. And by 1939. A celebration of England and the Englishman. From the wheelwrights of Devon to the potters of the north, from the shoe-makers of Northampton to the chair-makers of High Wycombe, the books will be—’

‘The chair-makers of High Wycombe?’

‘Renowned for its chair-making, Sefton. Do you know nothing of the English counties? Anyway, as I was explaining. I envisage this not merely as my magnum opus, but as a magnum bonum. De omnibus rebus, et quibusdam aliis—’

‘But that’s … dozens of books a year, sir.’

‘Precisely. Which is why I need an assistant, Sefton.’

‘I see, sir.’ The sheer scale of the task seemed ludicrous, lunatic. Which is, I think, what appealed: my own life had already reached the brink.

‘I was ably assisted for a number of years, Sefton, by my daughter and by my late wife. But my daughter is … maturing. And so I find myself … seeking to employ another. Anyway,’ he announced, as the final grains of sand gathered to announce the passing of fifteen minutes, ‘tempus fugit.’

‘Irreparable tempus,’ I said.

He glanced at me approvingly. ‘The hour is coming, Sefton, when no man may work.’

‘Indeed, sir.’

And at this he rose from his seat and walked towards the door. I followed. ‘I do hope that you don’t imagine that because of our surroundings today’ – he gestured into the gloom around him – ‘that we shall be going in for ritzy social gatherings, Sefton.’

‘No, sir. Not at all.’

‘Or chatterbangs. No swirl of the cocktail eddies here.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘Good. Well. That’ll be all, I think, Sefton. I’ll send a telegram.’ He went to shake my hand.

‘Actually, sir. I have one more question, if I may.’

‘Yes?’

There was one question that remained unanswered, and which I was keen to have resolved before leaving the room.

‘Might I ask your name, sir?’

‘My name? My apologies. I thought you knew, Sefton. My name is Morley. Swanton Morley.’

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_aa0a3a66-df00-544f-8d29-5ebd9d296152)

SWANTON MORLEY.

Anyone who grew up in England after the Great War will naturally be familiar with the name, a name synonymous with popular learning – the learning, that is, of the kind scorned by my bloodless professors at Cambridge, and adored by the throbbing masses. Swanton Morley was, depending on which newspaper you read, a poor man’s Huxley, a poor man’s Bertrand Russell, or a poor man’s Trevelyan. According to the title of his popular column in the Daily Herald he was, simply, ‘The People’s Professor’.

Morley’s story is, of course, well known: a shilling life will give you all the facts. (I rely here, for my own background information, on Burchfield’s popular The People’s Professor, and R.F. Bolton’s Mind’s Work: The Life of Swanton Morley.) Born in poverty in rural Norfolk, and having left school at fourteen, Morley began his career in local newspapers as a copy-holder. Coming of age at the turn of the century, he had ‘stepped boldly forward’, according to Bolton, ‘to become one of the heroes of England’s emancipated classes’. By the time he was twenty-five years old he was the editor of the Westminster Gazette. ‘Unyielding in his mental habits’, in Burchfield’s phrase, Morley had grown up the only child of elderly, Methodist parents. He was a man of strict principles, known for his temperance campaigns, his fulminations against free trade, and his passionate denunciations of the evils of tobacco. He was also an amateur entomologist, a beekeeper, a keen cyclist, a gentleman farmer, a member of the Linnean Society and the Royal Society, the founder of the Society for the Prevention of Litter – and the chairman of so many committees and charitable organisations that Bolton provides an appendix in order to list them and all his other extraordinarily various and energetic outpourings of the self.

On the day of my interview, however, I knew absolutely none of this.

Like most of the British public, I knew not of Morley the man, but of Morley’s books. Everyone knew the books. Morley produced books like most men produce their pocket handkerchiefs, his rate of production being such that one might almost have suspected him of being under the influence of some drug or narcotic, if it weren’t for his reputation as a man of exemplary habits and discipline. Morley had published, on average, since the early 1900s, half a dozen books a year. And I had read not one of them.

I had heard of his books: everyone had heard of his books, just as everyone has heard of Oxo cubes, or Bird’s Custard Powder. I had certainly seen his books for sale at railway stations, and at W.H. Smith’s. I can even vividly recall a bookcase on the top landing of my parents’ home – beneath the sloping roof and the stained-glass window – containing a set of Morley’s leather-bound Children’s Cyclopaedia,which I may perhaps, as a young child, have thumbed through. But they left no lasting impression. Swanton Morley was not an author who produced what I, as a young child, would have regarded as ‘literature’ – he was no Edgar Rice Burroughs, no Jack London, no Guy Boothby or Talbot Baines Reed, no Conan Doyle – and by the time I had reached my adolescence I had already begun to fancy myself a highbrow, and so Morley’s sticky-sweet concoctions of facts and tales of moral uplift would have been terribly infra dig. Finally, Dr Leavis at Cambridge had effectively purged any lingering taste I may have had for the middle- and the lowbrow. Morley and I, one might say, were characters out of sympathy, of different kinds, and destined never to meet.

But I was also, at that moment in time, out of work, out of luck and out of options.

On leaving the Reform Club after my interview, I therefore found myself walking up Haymarket, and then along Shaftesbury Avenue and onto the Charing Cross Road. I thought I might visit Foyle’s Bookshop, in order to catch up with a lifetime’s reading on Mr Swanton Morley.

Crowds thronged outside Foyle’s, the usual overcoated men rifling through the sale books, the publishers’ announcements filling the vast windows, one of which was given over to the current ‘Book of the Week’, a volume optimistically titled Future Possibilities. Two dismal young boys in blue berets prodded a shuffling monkey in a red cap to keep moving in circles on the pavement to the sick-making tune of their hurdy-gurdies. The customary beggar stood outside the main door, scraping on a violin, a piece of card hung around his neck. ‘Four Years’ Active Service, No Pension, Unable to Work’. Pity and loathing made me give him a penny.

To enter into a bookseller’s is of course to feel an instant elevation in one’s mental station – or it should be. My father had once held an account with Ellis of 29 Bond Street, a bookseller that raised the tone not merely of those entering the shop, but even of those merely passing it by, and I had visited small bookshops in Barcelona, and others in the Palais Royale in Paris, whose elegance seemed to rub off on the browser, like fine print from the daily papers. But Foyle’s is not, and never has been, a place of elegance and enlightenment: it is a shop, merely, a very large shop, but most definitely a shop, a place of sales, a department store for books, with its vast stock and signs jumbled everywhere, shelf rising inexplicably above shelf, book upon book, complex corridor upon complex corridor. I squeezed into the main lobby past a young lady in an apron dusting the top row of a long shelf displaying Sir Isaac Pitman’s apparently endless Industrial Administration Series, and asked the first shopwalker I could find, a young man, where I might discover the works of Swanton Morley. He turned from casually rearranging an inevitable shelf of those dreadful, faddish books – including How Not to be Fat, Why Not Grow Young? and Eating Without Fear – and escorted me daintily to a long wooden counter, bearing vivid colour posters advertising a new edition of Kettner’s Book of the Table, where a young lady – who might easily have been a barmaid were it not for the fact of her wearing spectacles – seemed more than prepared to assist.

‘Swanton Morley? One moment, please,’ she said efficiently, turning to reach behind her for a large red volume whose embossed spine announced it as The Reference Catalogue for Current Literature1936. ‘I’ll just check in Whitaker’s.’ She opened up the book, began rifling through the pages. ‘Would you like me to note down the titles for you, sir?’

‘No thank you.’ I thought I should be able to remember a few titles.

‘Very well,’ she said, her finger sliding slowly down the page and finally coming to rest. ‘Here we are now. Morley’s Animal Husbandry. That would be in Animal Lore, sir, second floor.’

‘Good.’ I made a mental note of Animal Lore, second floor.

‘Morley’s Art for All. Aesthetics, sir, second floor.’

I nodded. She continued.

‘Morley’s Astronomy for Amateurs. Astronomy, third floor … Morley’s Carpentering. Carpentering, second floor. Morley’s Children’s Songs and Games, ground floor … Cookery, first floor … Education, fourth floor …’

‘Wait, wait, wait,’ I said. ‘Third floor, second floor, first floor, ground floor.’

‘Fourth floor,’ she added.

‘And how many floors have you?’

‘Four. Unless you have a specific book in mind, sir, you might be better simply browsing among our stock. Mr Morley seems to have published many …’ She slid the big red book around so I could see the entries. ‘Gosh. Possibly hundreds of books, sir.’

‘I see.’ The list of Morley’s books ran to two pages of two-columned tiny type: my eyes glazed over at the mere thought of them.

Nonetheless, I wandered contentedly alone for the rest of the afternoon through Foyle’s great avenues of books. As readers will doubtless be aware, books in Foyle’s are not much arranged; within their categories books seem to be classified variously, and possibly randomly, by name, or by title, or by publisher. Some books seemed to have been undisturbed for many years, and many of the rooms were entirely deserted. But Swanton Morley was everywhere: he seemed successfully to have colonised the entire shop. During the course of a long afternoon I discovered not only books about poetry, and philosophy, and economics, which I had expected, but also campaigning works – The Cigarette Peril, Testaments Against the Bottle, War: The Living Reality – and volumes on gardening, marriage, medicine and mineralogy. In Religion I found Morley’s Children’s Bible. In Music, Learn to Listen with Morley. Elsewhere, in and out of their appropriate places I came across Morley’s Happy Traveller, Morley’s Nature Story Book, Morley’s Animal Adventures, Morley’s Adventure Story Book, Morley’s Book for Girls, Morley’s Book for Boys, Morley’s Everyday Science, Morley’s Book of the Sea, Morley’s Tales of the Travellers, Morley’s Lives of the Famous, Morley’s British Mammals, Morley’s Old Wild West … The sheer plenitude was astonishing, dumbing. It was as if the man were writing in constant fear of running out of ink. Morley’s Want to Know About …? series were everywhere. Want to Know About Iceland?Want to Know About Shakespeare?Want to Know About Trees? Just the thought of them made me want to give up knowing about anything. Morley’s Book of the World, a four-volume set I came across misplaced among books on Veterinary Science, made the boast on its dust jacket that a book by Swanton Morley could be found in every household in Britain. They were certainly to be found on almost every shelf in Foyle’s.

The books, qua books, varied in their quality from edition to edition: some were lavishly illustrated with pictures, plain and coloured, and mezzotint portraits; others were dense with type; some with fine bindings; others in cheap, flexible cardboard covers. And yet for all their apparent variety, the books were all written in the same tone – a kind of joyous, enthusiastic, maddening tone. The pose was of the jaunty professor – or, dare one say, the eccentric sixth-form master – and yet I thought, leafing through various volumes, that I occasionally caught sight of a desperate man fleeing from the abyss. This, for example, from Morley’s History of Civilisation: ‘Some may say that man is but a speck of mud suspended in space. I say to them, some mud, that can know what suffering is, that can love and weep, and know longing!’ Or this, from Morley’s English Usage: ‘The world may be troubled and difficult: our words need not be so.’

But perhaps I was reading my own experiences into the work.

I returned to my room in the early evening, depressed, dizzied and depleted.

As I made my way wearily down the stone steps towards my dank basement, a Chinaman hurried out of the laundry at street level above. He wore his little black skull cap and his long thin black coat turned green with age. We had occasionally exchanged greetings, though he could speak no English and I no Chinese – I was anyway far beyond the desire to be neighbourly. He smiled at me toothlessly, thrust a telegram into my hand, and hurried back to his work.

I tore open the telegram, which read simply:

‘CONGRATULATIONS. STOP. HOLT. STOP.

5.30 TOMORROW.’

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_e6f065d1-e248-5b52-ad3f-cf20048ca423)

AS IT HAPPENED, I had no other pressing engagements.

And so, the next day, I packed my few belongings – a spare suit, some thin volumes of poetry, my old Aquascutum raincoat, my supply of Seconal and aspirin – into a cardboard suitcase which I had managed to salvage from the wrack and wreckage of my life, and left my lodgings for Liverpool Street Station. There I found the connections for Holt, spent all my remaining money on the ticket and a supply of tobacco, and set off to meet my new employer, Mr Swanton Morley. The People’s Professor.

As the train pulled away I felt a great relief, a burden lifting from my shoulders, and I found myself grinning at myself in the window of the carriage. Little more than eighteen months previously I had left London – Victoria Station, the boat train for France, then Paris – for Spain, a young man full of dreams, about to embark on my great moral crusade, with justice on my side and my fellow man alongside me. Now, gaunt, limping, and my hair streaked with white, I saw myself for what I was: a man entirely alone, scared even of the roar of the steam train and motor traffic, impoverished and rootless. I had of course no idea at that moment, but in giving up on my absurd fantasies of performing on the stage of world history I had in fact unwittingly become a small and insignificant part of the terrible drama of our time. I had imagined that I was to determine the course of history, but history had taken possession of me. And if, as they say, nature is a rough school of men and women, then history is rougher … But already I am beginning to sound like Morley.

I should continue with the tale.

It had always been my ambition to travel. My father’s job as a royal messenger had meant that he had been all over Europe and further afield, scurrying from Balmoral to Windsor and to Whitehall, carrying with him letters of royalty and of state, emblazoned with the proud stamp OHMS. When I was a boy he would recount to me his stirring adventures among the Czechs, and the Serbians, and the Slovaks and Slovenes, dodging spies and brigands who tried to steal his dispatch case – tales in which he would triumph by courteous manners – and although we lived in relatively modest circumstances in a small house in Kensington, I had been introduced at an early age to ambassadors and diplomats from France, and China and Japan, and had imagined for myself a future abroad in khaki, and in starched collars, striped trousers and sun-helmet, upholding the Empire by good manners and breeding alone. In my own country I took little interest: I cared nothing for the Boat Race, or Epsom, or cricket at Lord’s. My dreams were of Balkan beauties, of Paris, Hungary and Berlin, of steamers on the Black Sea, and of adventures in Asia Minor. I imagined camels, and consuls and tussles with petty local officials. I harboured absolutely no desires to travel up and down on the branch lines of England.

Nonetheless, as we passed the houses and churches and slums of east London I felt the familiar ecstasy of departure. I took two Seconal, a handful of aspirin, and felt myself released again from the vast jaws of my ambitions, and fell into a troubled sleep – dreams of Spain confused with visions of a ruined London, flying demons dropping explosives overhead, fires raging in the streets, men slithering like beasts, every town and every city throbbing with fear and violence.

I woke thick-headed some time before we arrived in Melton Constable, where I changed quickly onto the branch railway, a little three-carriage local train done out proudly in its golden ochre livery, and which heaved its way slowly through the meadows of East Anglia. I took a window seat in the second-class non-smoker, the only seat remaining, and, gasping for air and desperate to smoke, ignoring the protests of my fellow passengers, pulled down a leather strap on the window – and was immediately assaulted by a dusky country smell of muck and manure. I quickly abandoned all thoughts of a cigarette. I hadn’t eaten all day, and the country smells, and the pathetic chugging of the train resulted in my feeling distinctly hag-ridden by the time we made Holt Station at precisely five thirty. I was the only passenger to disembark at Holt – porters hauled a couple of milk crates and packages out of the luggage van, a guard walked down the platform, closing each door, and then the bold little vermilion engine went on its way – and it was too late when I realised that I had left my cardboard suitcase on the train, with my spare suit, my poetry, my tobacco and my pills.

I looked around for any signs of help, welcome or assistance.

There was none. The porters had vanished. The guard gone.

And there was absolutely no sign of Morley.

Nor was there anyone in the station office – though a set of dominoes set out upon a table suggested recent occupation and activity. Outside, in the gravelled forecourt, was a car with a woman leaning up against it, languidly smoking, chatting to the young man who, I assumed from his uniform, should have been manning the station. I could see that the young lady might prove more of a distraction than a solitary game of dominoes. She wore her dark hair in a sharp, asymmetric bob – which gave her what one might call an early Picasso kind of a profile – and she was wearing clothes that might have been more appropriate for a cocktail party down in London rather than out here in the wilds of Norfolk: a pale blue-grey close-fitting dress, which she wore with striking red high-heeled shoes, and buttoned red leather gloves. It was a daring ensemble, deliberately hinting, I thought, at desires barely restrained; and her crocodile handbag, the size of a small portmanteau, suggested some imminent, illicit assignation. She struck one immediately as the kind of woman who attended fork luncheons and fancy dress parties with the Guinnesses, and who had ‘ideas’ about Art and who was passionate in various causes; the sort of woman who cultivated an air of mystery and romance. I had encountered her type on my return from Spain at fashionable gatherings in the homes of wealthy fellow travellers. Such women wearied me.

‘Well!’ she said, turning first towards and then quickly away from me, narrowing her eyes in a glimmering fashion. ‘You’ll do.’ There was a tone of studied boredom in her words that attempted to belie her more than apparent perk.

‘I’m sorry, miss, I do beg your pardon.’

She threw away her cigarette, ground it out theatrically under her foot, and climbed into the car. ‘Bye, Tommy!’ she called to the station guard, who began sauntering back to his office.

‘Goodbye, miss,’ he called, waving, red-faced, placing his cap back upon his head.

‘Excuse me,’ I said, addressing him. ‘I need to ask about my luggage. It’s gone missing. I wonder if—’

‘Well, come on, then, if you’re coming,’ the young woman interrupted, impatiently, patting the smooth white leather seat beside her in the car.

‘I’m awfully sorry, miss,’ I said, ‘I’m waiting for someone and—’

‘Yes! Me, silly!’ she said. ‘Come on.’

‘I’m afraid you’re mistaken, miss. I’m waiting for a Mr Swanton Morley.’

She cocked her head slightly as she looked at me, in a way that was familiar. ‘Sefton, isn’t it?’ she said.

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I’m here to collect you, you silly prawn, come on.’

‘Ah!’ I said. ‘I do apologise. It’s just, I was expecting … Mr Morley himself.’

‘I’m Miriam,’ she said. ‘Miriam Morley. And wouldn’t you rather I was collecting you than Father?’

It was an impossible question to answer.

‘Well,’ I said, extending my hand. ‘Pleased to meet you, Miss Morley.’

She raised her fingers lightly to my own.

‘Charmed, I’m sure.’

‘If you wouldn’t mind waiting a moment I need to see if I can arrange for my luggage, which I’m afraid I’ve left on the—’

‘Tommy’ll sort all that out, won’t you, Tommy?’ she said.

‘Certainly, ma’am,’ said Tommy obediently.

‘There,’ she said, her eyes flashing at me. ‘Now that’s sorted, hop in and hold on to your hat!’ she cried. I did as instructed, having no alternative, and as soon as I’d shut the door she jerked off the brake, thrust the gearstick forward, and we went sailing at high speed through the deserted streets of Holt.

‘Lovely little town,’ I said politely, above the roaring noise of the engine.

‘Dull!’ she cried back. ‘Dull as ditchwater!’

We soon came to a junction, at which we barely paused, swung to the right, and headed down through woods, signs pointing to Letheringsett, the Norfolk sky broad above us.

I felt a knotted yearning in my stomach – a yearning for cigarettes and pills.

‘Since we’re to be travelling together, miss, I wonder if you might be able to spare me a cigarette?’

‘In the glove compartment,’ she said. ‘Go ahead. Take the packet.’

I took a cigarette, lit it, and inhaled hungrily.

‘Manners?’ said my companion.

‘Sorry, miss? You’d rather I didn’t smoke?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous! Do I look like a maiden aunt?’ She did not. ‘But I would expect a gentleman to offer me one of my own cigarettes. Unless of course you are not a gentleman …?’

I lit another cigarette from my own, and passed it across.

‘So,’ she yelled at me, as we screeched around a sharp corner at the bottom of the hill, barely controlling the animal-like ferocity of the car. ‘You’re not one of Father’s dreadful acolytes?’

‘No. I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘I—’

‘Good. He usually attracts terrible types. Teetotallers. Non-smokers. Buddhists, even! Have you ever met a Buddhist, Sefton?’

‘No, miss, I don’t think—’

‘Dreadful people. Breathe through their noses. Disgusting. Being in the public eye, as we are, one does attract the most peculiar people. Hundreds of letters every week – some of them from actual lunatics in actual lunatic asylums! Can you imagine! Even the so-called normal ones are rather creepy. And we have people turning up at the house sometimes with cameras, wishing to take his photograph. Quite ridiculous! Isn’t it, Sefton?’ She looked across at me, searching my face for agreement.

‘Yes,’ I said, wishing that she’d pay more attention to the road. We passed, in quick succession: a large water mill to the left, offering for sale its own flour and oats; signs for a place called, improbably, Glandford, to the right; a large, rambling coaching inn, charabancs parked outside; a brand-new manor house sporting out-of-proportion Greek columns; and then a gypsy caravan by the side of the road, filthy gypsy children riding an Irish wolfhound before it, a pipe-smoking woman tending a fire alongside it, stirringa black pot of what may well have been goulash, but which was probably rabbit stew and, propped up against a nearby tree, a hand-painted sign advertising ‘Gypsy Pegs, Knife-Sharpening, Card Readings, Puppies’. I was suddenly struck by the rich and exotic beauty of the English countryside, as strange in its way as, say, India, or Port Said. Norfolk: North Africa. ‘It really is rather splendid here, miss, isn’t it?’

‘Oh come on, Sefton! It’s dull! Dull! Dull! Dull! I can’t stand being stuck up here with Father. But then where’s one supposed to go these days? Even London’s getting to be so boring. It’s becoming like a suburb of New York, don’t you think?’ She spoke as if having rehearsed her lines.

‘I’m afraid I’ve not had the pleasure of visiting New York, Miss Morley.’

‘Well, why don’t you take me one day, Sefton, and I’ll show you round.’

‘Well. I’ll certainly … think about that, Miss Morley.’

‘Call me Miriam.’

‘I’ll stick with Miss Morley, thank you.’

‘Oh, don’t be such a stick-in-the-mud, Sefton. What’s the point of such formalities? I believe in being brutally frank.’

‘Very good, miss,’ I said.

‘Really. Brutally, Sefton. I’ll be brutally open and frank with you, and you can be brutally open and frank with me. How does that sound? The best way between grown men and women, isn’t it?’

‘I’m not sure, miss,’ I said.

‘Oh, don’t be so solemn! It’s terribly boring. I’d hoped you might be more fun.’

‘I do my best, miss.’

‘To be fun?’ she said, taking both hands from the wheel and tossing away her half-smoked cigarette. ‘Do you now? I’ll be the judge of that, shall I? Anyway, I should warn you, seeing as you’re going to be staying with us, that despite what everyone thinks, Father is an absolute tyrant, and a complete dinosaur.’

‘I think, miss, it might be more appropriate if—’

‘Appropriate! Are you always so proper and correct, Sefton?’

‘Not always, miss. No.’

‘Good. I’m only telling you the truth. I’m having terrible trouble persuading him to introduce American plumbing at the moment. He believes in early morning starts and cold baths. He’s up studying at five, for goodness sake. I mean, reading before breakfast! Ugh! Rather grisly, don’t you think? Imagine what it must do to the digestion.’

‘Your father, I believe, is a very … diligent and profound student of—’

‘Oh, do give over, Sefton! He’s a madman. Forever writing. Forever reading. Continually being overcome with wonder at the world. It all makes for terribly boring company. Do you believe in early morning starts?’

‘It rather depends what one has been engaged in the night before,’ I said.

‘Quite so, Sefton! Quite so! You know, you might prove to be an ally about the place after all. What about hot baths?’

‘I have no strong opinion about hot baths,’ I said.

We had long passed Letheringsett, and were heading for Saxlingham.

‘“Hot baths are the root of our present languor,”’ she said, in a more than passable imitation of her father. ‘“The hot bath is a medical emergency rather than a diurnal tonic. It destroys the oil of the skin.” Ridiculous! Anyway, Sefton, you’re prepared?’

‘For what?’ I said.

‘What do you imagine I’d be asking you to be prepared for, Sefton?’ She raised a bold eyebrow beneath her bold asymmetric bob. ‘For this ludicrous new enterprise of his, silly.’

‘The County Guides?’

‘Yes. Absurd, isn’t it? As if anyone’s interested in history these days. Ye Olde Merrie Englande? Ye Cheshire Cheese? Ye Local Customs?’

‘I’m not sure that’s what he has in mind. I think it’s more a geographical—’

‘What? Plunges into Unknown Herts? Surrey: off the Beaten? Behold, Ye Ancient Monuments? For pity’s sake, Sefton. Who cares? All those dreadful places. Wessex and Devon! Never mind the north! Hardly bears thinking about. I’m afraid I just couldn’t be bothered.’

She glanced at me, her Picasso-like profile all the more striking in motion.

‘Do you drive, Sefton?’

‘I do.’

She then seemed to be waiting for me to ask something back; she was that kind of woman. The kind who asked questions in order to have them asked back, using men essentially as pocket-mirrors.

‘This is a lovely car,’ I said.

‘Oh, this? Yes. Father’s mad on cars. He’s got half a dozen, you know. Loads and loads. The bull-nosed Morris Cowley, with a dickey seat – dodgy fuel pump. And the ancient Austin, Of Accursed Memory. The Morris Oxford, with beige curtains at the windows; sometimes he’ll take a nap in it in the afternoons. It’s terribly sweet really.’

‘Yes.’

‘He can’t drive, though, of course. And he has all these sorts of crazy ideas. He thinks cars run better at night-time – something to do with the evening air. Claims it’s scientific. Absolute clap-trap, of course. But this is my favourite,’ she continued, stroking the steering wheel. ‘It’s a Lagonda,’ she said, stressing the second syllable, in the Italian fashion. ‘Isn’t it a lovely word?’

‘Quite lovely,’ I said.

‘Lagonda,’ she repeated. She clearly liked the idea of Italian. Or Italians. ‘Only twenty-five of them made. Designed by Mr Bentley himself, I believe. Herr Himmler has one in Germany. Harmsworth. King Leopold of the Belgians. I think you’ll find that ours is one of the only white Lagonda LG45 Rapides in England.’

‘Really?’ I said. She seemed to be awaiting congratulations on this fact. I declined to compliment, and instead silently admired the car’s upholstery and its fine walnut dashboard.

Saxlingham outdistanced, we were now beyond signposts, in deep English country.

‘She handles very well,’ she continued. ‘The car, I mean, Sefton.’ That ridiculous eyebrow again. ‘One of Father’s concessions to modernity. He won’t buy us proper plumbing, but anything that gets him from here to there more quickly he’s happy to fork out for! Honestly! It’s the production version of the Lagonda race car, you know. She’s really the last word.’

‘In what?’

‘Cars, silly! Top speed of a hundred and five miles per hour. Would you like me to show you?’

‘No, thank you, miss,’ I said, suspecting that we were already not far from such a speed. ‘I’ll take your word for it.’

‘Oh come on, Sefton,’ she said, fiercely revving the car’s engine. ‘Don’t you enjoy a little adventure?’

‘I used to,’ I said.

‘What? Lost your taste for it?’

‘Possibly, miss, yes.’

‘Oh dear. Well, perhaps I’ll be able to revive your flagging interest then, eh?’ And with this she leaned forward eagerly in her seat, stamped on the accelerator, and we began tearing up the roads.

‘You’re not scared are you?’ she called, as our speed increased.

But I now found her absurd flirtatious antics too wearisome to respond to at all, and simply gazed at the hedgerows speeding past inches from the car, which was spitting up stones and dirt – we were now driving along a single-track road that had clearly been made for horses’ hoofs rather than high-speed Lagondas.

We breasted a small hill and began careering down the other side, approaching a bend at both unsuitable angle and speed.

‘Slow down, miss,’ I said sharply.

‘What?’

‘Slow down.’

As we sped unwisely towards the bend she turned and looked at me and there was a look in her eye that I recognised – the same look I had seen in men’s eyes in Spain; and the look they must have seen in mine. Desperation. Fear. Joy. A shameless, stiff, direct gaze, challenging life itself. Terrifying.

She was understeering – out of ignorance, I suspected, rather than daring – as we approached the bend, and I found myself reaching across her, grabbing the wheel and tugging it towards me, attempting to correct the angle and bring the car in more tightly.

‘Look out!’ she screamed, as we swept down upon the bend, the rear of the Lagonda swinging out from behind us, her foot slamming down instinctively on the brakes.

‘Don’t brake!’ I screamed – I knew it would throw the car – and grabbed down at her ankle and pulled it up, reaching down with my other hand to apply a little pressure in order to transfer weight to the front.

It worked. Just.

We skidded to a halt, engine and tyres smoking, my head first in her lap and then juddering into the Lagonda’s pretty dashboard. The engine cut out.

‘Oh!’ she yelled. ‘You maddening man! What on earth do you think you’re doing?’

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ I yelled back.

At which challenge she threw her head back and laughed, a great throaty, hollow laugh, as though the whole thing were a mere prank she’d rehearsed many times. Which she may have.

‘What am I doing? I’mliving, Sefton! How do you like it, eh?’

I sat up, straightened myself, opened the car door and climbed out.

‘What are you doing?’ she called.

‘I’m getting out here, miss, thank you,’ I said.

‘But you can’t!’

‘Yes I can.’ I began walking on ahead. ‘I’ll find my own way now, thank you, miss.’

‘How dare you!’ I could hear the stamp of her pretty little foot. ‘Get back in here now! Now!’

The rich and exotic beauty of the English countryside

I walked on ahead, feeling calm.

‘Sefton!’ she called. ‘Did you hear me, man? Get back in here, now.’

Then, realising that I had no intention of obeying her orders and that she had indeed lost control of the situation, she promptly started up the still smoking engine, stamped her foot on the accelerator, and sped past, hooting the horn as she went.

‘See. You. Later. Sluggard!’ she called, snatching triumph with one last toss of her head. The look in her eyes remained with me for some time.

It was a trek to the Morley house. My head was throbbing. My foot was sore. I stopped off at a cottage on the road to a place called Blakeney, asking for directions, and the old cottager came out – a fine country figure, rigged out in greasy waistcoat and side whiskers of the variety people used to call ‘weepers’ – and pointed back the way I’d come. ‘But I’m terrible blind,’ he warned, as I departed. I wasn’t sure if he meant literally, or if it was some amusement of his. Whichever, he sent me the wrong way, and it was long past supper time when I eventually arrived, sans suitcase, sans pills, sans everything.

A thin new moon was set high in the sky.

I felt wretched. Outcast. Like an apparition. Or a newborn child.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_ad277974-2415-56af-9a29-7b2c84b63136)

THE FAMOUS MORLEY HOUSE, St George’s – described by Burchfield as ‘a true Englishman’s castle’ and by Bolton as ‘his legacy in bricks and mortar’ – was at that time only twenty years old, Morley himself having overseen its construction. Some, I know, have written off the house as a work of Edwardian folly, others have celebrated it as a testament to a great Englishman’s passions. But it was far too dark for me to make a judgement that first evening. Country dark is a darkness far beyond what city-dwellers imagine and at St George’s, at night, one could almost swim in the thick black swirling around one. I passed up the driveway, between imposing entrance gates – atop which, in glinting moonlight, sat St George on the one hand, dragon dutifully slain, and the Golden Hind on the other – and up past what I assumed to be a small lake, and walked, exhausted, between an avenue of old trees and finally up stone steps to the house, with statues of Britannia and lions rampant guarding the entrance. The door, an anachronistic mass of carved oak – like something by Ghiberti for a cathedral – stood open.

A true Englishman’s castle

‘Good evening!’ I called, peering into the house’s gloom. ‘Mr Morley? It’s Sefton, sir. I’m sorry I—’

For half a moment there came no reply and then suddenly in the entrance hall there was cacophony, the whole house, it seemed, screaming out in agony in response to my call. The noise was that of cold-blooded murder. Startled, I drew back, almost tripping down the steps, my heart racing. I shut my eyes and actually thought I might be sick – the maddening Miriam, no food, no pills, only a little tobacco. I had slipped back into a dream of Spain. But then, after several minutes, when the incredible noise continued and no one came, and with no intention of retracing my weary footsteps back down the driveway and all the way back to misery and London, I peered cautiously into the hall.