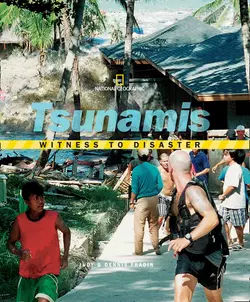

Witness to Disaster: Tsunamis

National Kids и Judy Fradin

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Природа и животные

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Witness to Disaster: Tsunamis, электронная книга авторов National Kids и Judy Fradin на английском языке, в жанре природа и животные