Running with Wolves

National Geographic Kids

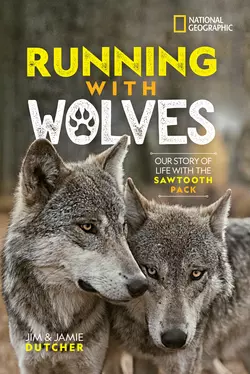

Discover the wonder of wolves from Emmy-award winning filmmakers Jim and Jamie Dutcher as they tell their story of the six years they watched, learned, and lived with the Sawtooth wolf pack.Adventure, friendship, and family come together in this riveting memoir as two award-winning filmmakers take you through the experience of the years they spent living in the wild with a real-life wolf pack. Jim and Jamie set out to show the world that instead of fearsome beasts, wolves are social, complex, and incredible creatures that deserve our protection. Deep in the mountain wilderness of Idaho, they set up Wolf Camp, where they spent years capturing the emotional, exciting, and sometimes heartbreaking story of their pack.Meet Kamots, the fearless leader. Learn from wise Matsi. Explore the forest with shy Lakota. And watch as adorable pups grow from silly siblings to a devoted pack. See how these brave wolves overcome all odds, battling mountain lions and frigid temperatures. Most of all, discover the surprising kindness, compassion, and devotion that Jim and Jamie discovered by living with wolves.

Text and photographs Copyright © 2019 Jim and Jamie Dutcher

Compilation Copyright © 2019 National Geographic Partners, LLC

Published by National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. The Society receives funds from National Geographic Partners, LLC, funded in part by your purchase. A portion of the proceeds from this book supports this vital work. To learn more, visit natgeo.com/info (http://natgeo.com/info).

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com (http://nationalgeographic.com), call 1-800-647-5463, or write to the following address:

National Geographic Partners

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books (http://nationalgeographic.com/books)

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org (http://ngchildrensbooks.org)

More for kids from National Geographic: natgeokids.com (http://natgeokids.com)

National Geographic Kids magazine inspires children to explore their world with fun yet educational articles on animals, science, nature, and more. Using fresh storytelling and amazing photography, Nat Geo Kids shows kids ages 6 to 14 the fascinating truth about the world—and why they should care. kids.nationalgeographic.com/subscribe (http://kids.nationalgeographic.com)

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: bookrights@natgeo.com (mailto:bookrights@natgeo.com)

Designed by Sanjida Rashid

Map (#ulink_68317078-1991-51f0-9d80-0a43944a30fd): Evelyn B. Phillips; Map (#litres_trial_promo): National Geographic Maps; Illustration (#litres_trial_promo): Fernando G. Baptista.

The publisher would like to thank everyone who made this book possible: Kate Hale, executive editor; Paige Towler, associate editor; Mike McNey, cartographer; Shannon Hibberd, senior photo editor; Sally Abbey, managing editor; Joan Gossett, editorial production manager; and Anne LeongSon and Gus Tello, production assistants.

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4263-3358-3

Reinforced library binding ISBN: 978-1-4263-3359-0

Ebook ISBN 9781426333606

v5.4

a

Jim and Jamie Dutcher grew up in different places, but they both loved exploring the great outdoors. They had a passion for observing wildlife that continues to this day. Along with that passion comes immense respect for wild animals, and for their wildness. If you see a wild animal, be respectful just like Jim and Jamie. Observe the animal from a safe distance and don’t disturb it. Let it be wild.

In this memoir, Jim and Jamie each tell different parts of their adventures with wolves. Jim tells much of the first half because Jamie didn’t join the wolf project until its third year. Yet, she was always very much a part of it. Long before she arrived at wolf camp, Jamie helped keep the project on a steady course through advice and encouragement offered in letters and phone conversations. Many of these communications are recalled in this story.

For our grandchildren, Arianna, Sofia, Natalie, Sebastian, and Emiko; our nephew, Sam-Henry; and our niece, Madeline. And for young people everywhere—may you always follow your dreams. Together, we can make a difference for the natural world.

—Jim and Jamie Dutcher

Cover (#u27f480b3-007b-5a5f-9c46-e80db7e7bcc4)

Title Page (#u085491f8-8c4d-560b-8871-56082299d8b1)

Copyright (#u0b65c513-9c1d-57e3-aa7a-8697f13b8e63)

Note (#ub929a1d3-4a38-5599-b309-2c3d1ada8eaf)

Dedication (#ue1ebfb47-6616-53b6-b885-6c7de085ae60)

Map (#u533b6df3-653c-517e-9171-9681fee69d91)

A WOLF’S TRUST (#u6d4a3108-50cc-5130-ad8f-a052068b8f4b)

CHAPTER 1 LONGING FOR WILDERNESS (#uc5394901-bf00-5463-8423-92d639770141)

CHAPTER 2 A BRIGHT IDEA (#u59c6202f-c7da-560e-aa0d-29d8620578e5)

CHAPTER 3 BEGINNINGS OF THE SAWTOOTH PACK (#u7249348c-2733-5860-b9b8-a001791b2208)

CHAPTER 4 TROUBLE IN THE PACK (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5 SEASON OF CHANGE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 A COMPASSIONATE ALPHA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 A GUT-WRENCHING DECISION (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 NEW ADVENTURES (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 TWO LEAPS FORWARD (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 FRIENDS FOR LAKOTA (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 CALL OF THE WOLF (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 FAMILY TIES (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 CELEBRATION! (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 TIME TO SAY GOODBYE (#litres_trial_promo)

PHOTO INSERT (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

THE WORLD OF THE WOLF (#litres_trial_promo)

KEYSTONE SPECIES (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT LIVING WITH WOLVES (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

I stood silent and motionless, my eyes trained on the mysterious black hole in front of me. The opening was just two feet (0.6 m) wide, half hidden beneath a fallen spruce tree. Its oval shape reminded me of a dark, mystical eye, like that of a dragon. Such a thought of fantasy contrasted sharply with the reality of what I was about to do. It was something that no one had likely ever done.

I sniffled against the chilly April air. Spring had sprung a month earlier, according to the calendar anyway. Somewhere nourishing rains and lengthening days were coaxing flowers to show their colorful faces. Somewhere tree buds were awakening from their long winter rest, and grass was once again growing green.

Somewhere, but not here. Snow still covered most of the ground in the forest that surrounded me. The warmth of the season comes late, and slowly, to the mountains of Idaho.

I glanced at my husband, Jim, through a cloud of my condensed breath. He crouched nearby behind his movie camera. All of his years as a filmmaker led up to this moment, and he wasn’t about to let it slip by without capturing it on film.

Looking up from his eyepiece, he nodded. I walked cautiously toward the gaping black hole. With each step, I became more aware of the sounds around me. The gentle rush of a breeze and the chirping of black-capped chickadees mingled with the crunching and squishing of snow and mud under my boots. My own heartbeat reverberated through several layers of clothing.

There were other sounds, too. Distinct chirps, almost birdlike, pierced the frigid air. The source was unseen, distant yet nearby, but I knew what it was. So did the wolves.

Seven big and powerful gray wolves were gathered around the opening, pacing back and forth and trampling the ground into a muddy mess. They couldn’t go in—they instinctively knew that—so they took turns peering into the hole as they whined with excitement.

As I slowly reached the wolves, they made way for me, as if I were one of them. I knelt down on the damp ground and stared at the opening. Barely a minute went by. Then suddenly a wolf poked her head out. Her yellow eyes set against her black face were like two piercing lights. The sight would have startled—and maybe frightened—most people. But I knew those eyes well. They looked curious…intelligent…calm.

The black wolf emerged completely, revealing her full size. She greeted me with a tender whine, gave me a little lick on the nose, and sat beside me. We looked at each other. I gently spoke and asked if I could go where she had been. I tried to read her body language for any signs of fear or uncertainty. Was she annoyed that I was here? Would she attack me? She never had, but today was unlike any other, and quite frankly I wanted to make sure she wouldn’t bite me on the behind.

Her expression seemed only to say, “It’s okay, go on in. I trust you.”

That was the invitation I was hoping for. I took out a small flashlight from my jacket pocket and showed it to her. She inspected it and seemed satisfied that it posed no threat. I smiled and took a deep breath. Then I flicked on the light, lowered my head, and leaned in…

Why was I about to squeeze myself into this dark, damp hole in the ground? What did I expect to find? Stranger still, why was a large, powerful wolf sitting calmly beside me as I prepared to enter a place so precious to her that even other wolves were not allowed?

The answers to these questions are at the heart of this story. It’s a story of our adventures. It’s a story of our struggle and survival and the wolves’ struggle and survival, but also of trust, friendship, and even love. It’s a story of what happens when two people decide it would be a good idea to spend six years living in the wilderness with a pack of wolves.

I tugged gently on the worn leather reins, and Glendora, my buckskin mare, came to a slow halt. She turned her head to look back at me and I leaned down in the saddle to give her a reassuring pat on the neck. We both knew we had a job to do, but the view was just too spectacular to miss. I needed a minute to take it all in.

It was first light—my favorite time of day. The sun had just peeked above the horizon and its glorious rays began to illuminate the landscape. A beautiful lake shimmered in the growing light. Its smooth surface mirrored perfectly the fast-changing colors of the early morning sky—from golden yellow to deep pink to rich azure blue. Bright wildflowers dotted the green grassy meadows that surrounded the lake.

What dominated the landscape, though, were the mountains. In almost every direction, forests swept up to the base of sheer rocky cliffs that reached at least 2,000 feet (610 m) toward the sky. Most of the mountains formed walls of layered rock, like those of the Grand Canyon, rather than peaks. The ashen gray cliffs looked dull compared to the rich palette of the valley below.

But sunlight is nature’s artist, and it can turn a colorless canvas into a dazzling masterpiece. That’s what I was waiting to see on this clear, chilly summer morning. As the sun inched its way into the sky, the light crept down the east-facing cliffs to my right, transforming the somber gray first into a rosy pink and then a brilliant orange. The rock seemed to glow. The effect soon passed, but as always, it was breathtaking.

I looked south across the lake to the ranch on the far shore. Then, taking a deep gulp of fresh mountain air, I sat up straight in the saddle, thought for the umpteenth time how lucky I was, and announced to my trusty companion, “Okay, Glennie, let’s round up these ponies.”

The year was 1959. I was 16 years old and had the summer job of a lifetime—I got to be a cowboy! Well, a wrangler actually. A cowboy herds cattle; a wrangler herds horses.

I worked on a ranch in the high country of Wyoming. By “high country,” I mean the ranch sat at 9,200 feet (2,804 m) above sea level. There, among the peaks of the Absaroka Range, I felt like I was on top of the world. The location couldn’t have been more perfect. The ranch sat on a hill above the mountain lake. Beyond the ranch stood a deep green forest of pine. The views were awe-inspiring no matter where I was, and not only at first light.

Then, as now, this part of the Rocky Mountains was far less known than the nearby tourist attractions of Yellowstone National Park. That was just fine with me. I could roam and explore the pristine wilderness without seeing a single person. That is, once my daily chores were done.

Each evening before sundown, I would drive a herd of about two dozen horses from the ranch to a meadow on the other side of the lake. There I would leave them to graze, drink from a cool mountain stream, and sleep peacefully among the willows and meadow grasses.

Then every morning I had to go get the horses and take them back to the corral. This wasn’t a job for anyone who liked to sleep in. I would rise from my bunk bed well before dawn and dress quickly—not only because I wanted to hit the trail but also to stay warm. At this high elevation, the early morning air was cold, and usually I wore two pairs of jeans, a long-sleeve shirt, and a jacket. My leather gloves and cowboy hat also provided some warmth.

I really didn’t mind the cold weather, though. In fact, for a kid who grew up in subtropical Florida, these cool summers were welcome, even exhilarating.

So, looking every bit the part of a movie cowboy, I’d ride Glendora back to the meadow just as the faintest glimmer of light began to tinge the dark eastern sky and the jagged peaks of the Pinnacle Buttes. The well-rested horses would usually be on their feet by the time we arrived, finishing a breakfast of soft, dew-covered grass.

I’d circle around to the far side of the herd and push them together in the direction of the ranch. I didn’t literally push the horses. Instead, I’d come up from behind and call out “Hee-yah!” Off they’d gallop. I would feel the rumble through my body as their hooves pounded the ground.

Sometimes the horses would spook and bolt in another direction. Glendora would take off after them with little coaxing from me. It’s a good thing she knew her job so well, because during these hard gallops I could do little more than hang on for dear life.

Eventually we’d round up the herd. Then I’d ride behind or alongside the horses to guide them the two miles (3 km) back to the corral for the day.

That was the general idea, anyway. When you’re dealing with animals, things don’t always go according to plan.

Often, I’d discover that other large animals, hidden from view, had visited the herd during the night—and they were sticking around for breakfast.

You might not think a meadow could provide much cover for anything larger than a ground squirrel or a mouse. But the willows were a bit taller than me and grew in tangled bunches, like dense bushes. Even sitting high in the saddle, it was difficult to see more than just the backs of the horses grazing in between the willows. It wasn’t until I started flushing the horses out that I noticed some of them didn’t look like the others. Some had antlers! To my surprise, I realized that I was rounding up not only horses but also a few very confused moose.

I felt sorry for them. The moose must’ve been completely bewildered, wondering why their breakfast had been disturbed by a stampede—and why they were in the middle of it! Sorry or not, I had to separate these wild animals from the herd.

Easier said than done.

Moose aren’t usually aggressive, but if they feel harassed or threatened, watch out! They can kick their sharp, pointed hooves forward, backward, and sideways. I didn’t want to be on the receiving end of one of those powerful thrusts. And I sure didn’t want to mess with those antlers. They were wider than my arm span. One quick move of the moose’s neck and his massive bony headgear could crush my leg or Glendora’s skull. I didn’t dare get too close.

So instead of separating the moose from the herd, I separated the herd from the moose, pushing the horses away as I normally did. Now and then, the moose followed or ran with the herd for a while. Maybe they didn’t want to leave their new companions. Or maybe they just wanted to see where everyone was going. Whatever the reason, their stomachs usually won out, and they’d trot back to the meadow for breakfast.

Dealing with moose tested my horse-riding skills and helped keep the job from ever becoming boring. Not that there was much chance of that happening. Something was always keeping me on my toes.

If moose weren’t visiting the meadow, strays were leaving it.

Strays were horses that wandered off early in the morning, before I got to the herd. I knew each of the 28 steeds in my charge and could tell quickly when one or more were missing. It always seemed to be the same restless few that wandered, so I had tied bells around their necks earlier in the summer for easy tracking.

One day, several horses had wandered off into the forested hills on the other side of the meadow. After driving the rest of the herd back to the ranch, I returned to collect the strays.

It was so quiet. Away from the herd, the ranch, and anything with a motor, I could hear the slightest sounds—the shriek of a hawk high above or the trickling of a winding brook. So it was no surprise that I picked up the faint tinkling of bells coming from the forest across the meadow. Glendora and I followed the distant ding, ding, ding up into the foothills.

These were my favorite times. Tracking strays gave me a chance to explore the countryside. The cool air, the wilderness, and the freedom were all so new to me, and thrilling. I was living my dream of roaming the Great American West.

That morning we searched more than usual as we followed the bells farther and farther into the Wyoming backcountry. It was slow going. We blazed our own trails as we picked our way through forests, creeks, and clearings. Wooded ravines were the toughest to navigate. I leaned back in the saddle to make the downslope easier on Glendora. Then she quickly scooted up the other side. On hard ground, I stopped every few minutes so that the clip-clop of horseshoes didn’t drown out the distant sound of bells.

We were an hour or so into our journey. The sun had climbed higher in the sky and I welcomed the growing warmth. I pushed aside a low-hanging branch as we stepped out of the forest into a large clearing. Suddenly we stopped in our tracks.

Beyond the clearing, groves of dark green lodgepole pines gave way to a steep grassy slope strewn with boulders from the rock formation that towered high above: Brooks Mountain. Its majestic cliffs rise 1,300 feet (396 m) straight up. This mass of rock stretches for more than a mile and is part of the Continental Divide—the long line of high elevations that zigzags its way north and south across the continent and separates river systems that flow to the Pacific from those that flow to the Atlantic.

I had seen Brooks Mountain many times, and it always struck me as magnificent, but at that moment, something else caught my attention.

Across the clearing stood a coyote.

It’s not that the sight of a coyote was a heart-stopping shock. It wasn’t. All sorts of animals big and small roamed the countryside. I had seen eagles soaring above the cliffs, black bears nibbling berries, herds of elk grazing in open meadows, and more.

Coyotes were common, too, but they were skittish. Ranchers hunted them, afraid that the carnivores would harm their livestock. Consequently, coyotes had learned to quickly run away when they saw or smelled a human approaching.

Not this coyote. He and I were having a staring contest.

He didn’t seem the least bit afraid, just curious about this two-legged creature sitting atop a four-legged creature across the meadow. Something else was different about him. Even from a distance I could tell that he was larger than any coyote I had ever seen. His legs were longer and his face broader.

Then it hit me. This wasn’t a coyote at all. It was a wolf!

Glendora became restless. She snorted and neighed, shook her head several times, and stepped in place nervously. “Easy, girl,” I said as I gently patted her neck. Glendora calmed down, but I wanted a closer look, so I coaxed her to slowly follow the edge of the clearing and head toward the wolf.

I learned two things about wolves that day—they’re smart and they’re curious. While we circled the edge of the clearing, the wolf did, too, in the same direction so as to keep the same distance between us. His yellow eyes stayed locked on mine as we both circled the meadow. Eventually we each ended up where the other had stood.

The wolf inspected where Glendora had trampled the grass. He showed no signs of fear, no signs of aggression, only cool curiosity. What were we? Were we a threat? He seemed to be pondering these questions. I watched, fascinated, and wondered what conclusions he had drawn.

I couldn’t take my eyes off this large, furry, doglike creature—a predator that I had long heard was an aggressive, vicious, unforgiving killer. I saw none of that. All I saw was intelligence and fearlessness…but only for a minute longer. Then, the wolf simply turned and trotted away and disappeared among the pines.

Eventually, I found the stray horses. They were safe and sound, but I never saw the wolf again. No wonder. I later discovered that seeing a wolf at that time in that place—my very first wolf sighting—had been an incredibly rare event. In 1959 as few as 15 wolves lived in the U.S. Rocky Mountains, and I had seen one of them. I wouldn’t see another for 30 years.

And when I did, it would change my life forever.

The zookeeper burst through the doorway. The front of her T-shirt was untucked, with the bottom folded up like a soft taco shell, and her hands clearly cradled an object within.

“It’s a joey!” the keeper exclaimed. An involuntary gasp escaped my lips as the keeper revealed the precious cargo she was carrying—a tiny, hairless baby kangaroo.

“What happened?” my colleagues and I asked in unison.

“The mother rejected him,” she replied hurriedly. “I don’t know why.”

The keeper, sweating on this hot day in May at Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., quickly explained that the mother kangaroo had kicked the joey out of her pouch. A visitor had seen the horrifying incident and contacted the zookeeper, who rushed into the enclosure, picked up the squirming youngster, and brought him to me and two other keepers at the zoo hospital.

The baby kangaroo was no bigger than the length of my hand. Like all joeys, he would normally live inside his mother’s pouch for six months after birth before developing enough to venture outside now and then. But this poor little guy, who we called Rufus, was only three months old and completely helpless. He would never survive without the care of his mother—or without the care of three determined zookeepers.

We were the only chance Rufus had. We had to mimic the conditions of a mother kangaroo in every possible way, including the soft, moist, and warm environment within her pouch. But how?

Part of the answer was clear—make a substitute pouch. We fashioned a number of comfortable pouches out of soft cotton pillowcases. To hold in body moisture, we covered Rufus with a special kind of skin cream. For warmth, we placed him inside one of the cotton pouches and set it in a heated incubator about the size of a large aquarium.

Food presented another set of challenges. Baby kangaroos eat every two hours, day and night, and Rufus was no exception. We mixed up a nutritious formula that was similar to his mother’s milk. Then we fed him using baby bottles topped with nipples that were the length and shape of his mother’s.

Joeys have a weak immune system, so we took every precaution to prevent infections. Each time we fed him or handled him for any reason in those first few months, we wore surgical gowns, gloves, and masks. We washed and bleached his pouches after every feeding so there would always be a stack of them ready to use.

To provide the round-the-clock care that a joey needs, we took turns taking Rufus and his incubator home every evening. Those were sleepless nights. After donning my surgical garb, feeding Rufus, wrapping him in a fresh pouch, getting him settled, and changing my clothes, I’d barely close my eyes before it was time to do it all over again.

Needless to say, after such a night I was groggy the next morning at work. So what better way to shake off the cobwebs than to hop around the office? Literally. A few times each day, I or one of the other “kangaroo moms” would cradle Rufus in his pouch and hop around our hospital office for a few minutes. Not just any old hop, either. No, this was a regular dance. Hop, hop, hop, dip to the left. Hop, hop, hop, dip to the right. Repeat and repeat and repeat!

The dance was hilarious. It was also absolutely necessary. The hopping mimicked the movements Rufus would have received inside his mother’s pouch. Such movements are essential to develop the joey’s circulatory and digestive systems. And that’s what we explained to any perplexed visitor who happened by the office in the middle of a kangaroo dance.

All of the loving care paid off. Rufus grew into a healthy and playful young kangaroo. After six months or so, we no longer had to cradle him. Instead we hung his pouch on a doorknob, and he could hop in and out as he pleased.

I can still see him grabbing the pouch, launching himself off the floor, and diving in headfirst. A hodgepodge of limbs and tail stick out for a brief moment, then disappear inside. The pouch churns like a tongue rolling against the inside of a cheek. Suddenly up pops a head. The mischievous look on his face was priceless.

So was the experience of caring for this little life. Rufus took us on an exhausting, emotional roller coaster, and I wouldn’t have traded the wild ride for anything. Taking care of Rufus and other at-risk creatures at the zoo was never a job to me—it was a passion, a passion born out of my love for animals.

That love began long before I ever dreamed of working at the zoo. In fact, it was evident to others when I was only a few years old, when my hands held not animals but crayons.

The first recognizable picture I ever drew was an elephant. At least, that’s what my grandmother told me, and I believe her. When I wasn’t drawing pictures of animals, I was reading about them. If there was an animal on the cover, that’s the book I opened. Even well into my teens, I would trade a mystery or adventure novel for a book about animals any day.

Drawings and stories sparked my imagination, but what I enjoyed most were my outdoor adventures, where I was in the animals’ world. As a young girl, I loved exploring the woods behind my house in suburban Washington, D.C., searching for wildlife. Those woods were my wilderness. I could lose all track of time wandering among the oak and hickory trees, turning over fallen leaves and peeking under logs in search of salamanders and frogs.

I kept my eyes peeled for snakes, too. Not to avoid them, but to get a good look at them! They didn’t give me the willies like they do some people. Instead, I was mesmerized by their colors and patterns, by how they moved and what they did.

My suburban wilderness was also home to larger animals, like white-tailed deer. But that’s not all. When I was seven years old, I heard that someone had spotted a black bear in a nearby wooded park. I searched those woods for days. I imagined what I would say to the bear if we met. No doubt we would like each other. In fact, I let myself believe that we would become friends.

I never did find the bear. And as I grew older and learned more about wildlife, I realized that a human and a wild animal could not become friends. At least, that’s what all the experts said.

My passion for wildlife only grew. After college, I tried to settle down and live a “normal” life, apart from all things wild. But animals were never far from my mind. I longed to be part of their world. So, in my mid-20s, I made two decisions that allowed me to follow my passion.

First, after working at a small-animal clinic, I decided to apply for a job at the National Zoo. There at the hospital I took care of sick, injured, or other at-risk animals, like Rufus.

The second decision ended up being the most monumental one of my life. I took a trip to Africa.

I traveled with a friend to Zimbabwe to photograph some of that African country’s amazing wildlife. I had always enjoyed photography, and this was a chance of a lifetime to see elephants, gazelles, lions, and other wild animals in their natural setting. The trip was phenomenal, but the most significant moments took place on the way home.

My friend and I were boarding a plane in London to begin the second leg of the long journey back to Washington. With my backpack flung over my shoulder, I was trying to avoid banging into other passengers as I shuffled my way down the aisle. I was about to pass a man placing a bag in the overhead compartment. Suddenly he looked at me and asked, “Have you been in Africa?”

I had a deep tan and was wearing a beaded necklace of coral and warthog tusk. Clearly, I couldn’t have gotten the tan or the necklace in London, so with a smile and a good-natured touch of sarcasm, I responded, “Yes, what gave it away?”

He smiled back and mentioned my necklace. Then he started asking about my trip. Where had I been? What animals had I seen?

But a narrow plane aisle with annoyed passengers piling up behind us was no time or place for an extended conversation. So, after a few brief answers, I continued to my seat a dozen rows back.

Every day people have brief encounters that they never think about again. It might be chitchat in the checkout line at the grocery store or a pleasant exchange of “Thank you” and “You’re welcome” while holding open a door for a stranger. This easily could have been one of those forgotten encounters.

Fortunately, the man who had struck up a conversation with me wanted to continue it. After we reached cruising altitude, he looked back, unclasped his seat belt, and walked down to my aisle seat. He greeted me with a sweet smile and a kind “Hi again.”

We talked easily. He too was on his way back from Africa. He had been visiting his sister in Kenya, where she and her husband operated a tented camp in a remote area. We swapped stories of the African animals we had seen. Through our tales, we relived the wonder of the wildlife and the respect for the natural order of things that we had witnessed on the African savanna.

I immediately launched into a story about when I saw a pack of five spotted hyenas splashing through marshy waters to steal a zebra carcass from three lions. It was like an old-fashioned sword fight.

The hyenas attacked first. Then the lions withdrew, dragging most of the kill with them. Ever the opportunists, the hyenas snatched up a few hunks of meat left behind, then withdrew a few feet themselves.

Not satisfied with their meager scraps, the hyenas made another charge. Their high-pitched hums and whines sent a shiver down my spine. Instantly one of the lions surged forward with a ferocious roar and scattered the thieves. But they immediately regrouped, chased away the lions, and claimed their prize—the rest of the carcass. Victors: hyenas!

My new friend listened with rapt attention. Then, with his blue eyes sparkling, he described in vivid detail how a cheetah had chased down a gazelle. As he spoke, I could smell the dust kicked up from the dry grasses and feel the relentless heat of the sun. I saw the rippling muscles of the cheetah as she hunted the nimble gazelle. With his hands, my friend pantomimed how the cheetah gobbled up ground with bursts of speed as fast as a car on the highway.

I immediately knew I was in the presence of a gifted storyteller.

Not surprisingly, he revealed he was a filmmaker. In fact, at that moment he was finishing a film about the life of beavers for National Geographic. He told me he was on his way to their headquarters in Washington to discuss the film’s progress.

The more we talked, the more we enjoyed each other’s company. Our common interests certainly helped. In addition to being a filmmaker, he was, like me, a photographer, a bird-watcher, and passionate about wildlife. I was also taken by his smile, his laughter, and his kindness.

Then we got separated.

In the mad rush of people getting off the plane in Washington, I lost sight of this man whom I wanted to know more about. I didn’t even know his name. With a sigh I resigned myself to the fact that we would never see each other again. Our relationship would be no more than pleasant conversation to pass the time on a long plane ride.

Fate appeared to have other ideas.

As I joined a hundred other people at baggage claim to get my luggage, I turned—and there he was! We both beamed in recognition, and relief, and picked up our conversation. He told me more about his wildlife films, and I told him that I had applied to work at the National Zoo.

And we finally introduced ourselves. Now I had a name to put with the face of Jim Dutcher.

Despite the bond we felt for each other, we lived in two different parts of the country, almost in two different worlds. After Jim’s business in Washington, he was heading home to Idaho.

Idaho! I never would have guessed it. I had nothing against this western state, of course. It’s just that I didn’t know anything about it, except that potatoes came from there. My mind flashed back to grade school and the maps that showed the main products from each state. I pictured the map of Idaho with potato icons scattered about.

For an Easterner like me, who had never been west of the Mississippi River, Idaho seemed as remote as Africa. I couldn’t imagine life there.

Little did I know that in a few years’ time, Idaho would be the place where all my dreams would come true.

Long before the thought of living with wolves ever entered my mind, and even before I met Jamie, I honed my skills as a wildlife filmmaker. My first films were undersea adventures. I focused on the colorful fish that live among the reefs off the shores of my native Florida.

As beautiful and fascinating as I found the ocean, I was drawn to the forested mountains of the West. My teenage experiences as a wrangler fed my desire to film some of the animals that live there—like beavers.

These creatures are usually either underwater or in their lodges, making them tough to spot in the wild. So instead, for my movie, I built a beaver lodge inside a log cabin. I was able to film—from the other side of a large window—the comings and goings of a beaver family and show the world these quirky animals’ daily activities. I even filmed the birth of beaver kits.

The subject of my next film was a larger and decisively more dangerous animal. It was also much more elusive, almost to the point of being ghostly.

The cougar grasped the neck of the deer in her powerful jaws as she dragged the limp body through the dry pine needles and sparse clumps of grass. When she released her grip, the lifeless animal hit the ground with a thud.

The deer had been struck and killed by a vehicle—a certain tragedy for the deer and most likely a harrowing experience for the driver. For the cougar, it was a week’s worth of meals. But the food wasn’t only for her.

Three male cougar kittens watched with interest from the shadows of a nearby rocky perch. Their spotted youthful coats made them difficult for the naked eye to see. But my telephoto lens clearly caught their expressions, which seemed to say: “Here’s something new.”

Until this point, the six-week-old kittens’ nutrition had come exclusively from their mother’s milk. It was now time to wean them away from nursing. As carnivores, they needed to experience the taste of meat. This would be their first.

The mother looked up toward her kittens and sounded the call for dinner. Meow! Meow! Remarkably similar to the mewing of a household cat, the call of the cougar was nonetheless sharper, shorter, and more determined. To my ears it sounded like she was saying “Now! Now!” and was not about to take no for an answer.

The kittens dutifully heeded the call. Placing one furry oversized paw in front of the other, they gingerly stepped down from their perch toward this new lesson in survival.

Meanwhile, the mother prepared the meal the way mother cougars do. She cleaned a portion of the deer’s belly by removing the fur and tough skin with her raspy tongue and teeth to expose the fresh meat for her kittens. Then she took a few bites and walked away.

This was the part of the lesson the kittens had to learn for themselves—how to actually eat prey.

They approached the deer steadily but cautiously. One batted it with his paw, perhaps testing if it was really dead. Another tugged at one of the deer’s large pointy ears. He kept gnawing on the tough leathery appetizer, ignoring for the moment the entrée his mother had prepared on the other side.

The kittens not only had to get used to solid food but also had to learn how to chew and swallow it without eating the fur. Now and then, a kitten gagged, opening his mouth wide and releasing a harsh Ack! from his little throat.

I couldn’t help but smile behind the camera. It was thrilling to capture this brief snippet of cougar life. It was one of many rare glimpses into the hidden world of this magnificent animal. I was documenting behavior that few if any humans had ever witnessed. Every moment was new and surprising…and priceless.

How was I able to get such intimate footage of an animal that was seldom seen in the wild, let alone filmed? Not by chasing after it, that’s for sure.

I had better methods in mind. And the lessons I learned from making my cougar film would prove to be invaluable, especially when I began studying wolves several years later.

The idea to focus on cougars came from Jamie. I was in Washington for meetings while finishing the beaver film. As usual, Jamie and I met for lunch while I was in town. I wanted my next project to be about a big cat—perhaps cheetahs in Africa.

Jamie suggested cougars instead. These animals go by many names—mountain lion, puma, catamount. The idea intrigued me. I had never seen one in the wild, but I knew they were out there, roaming the same forests and mountainsides that I called home. I later discovered that Jamie had steered me toward cougars partly to keep me in the country. I was glad she did.

While planning the cougar project, I knew that I would have to bring the cougar to me. That meant filming in an enclosure—a large fenced-off area on the edge of wilderness. I didn’t want to fool anyone. I would make it clear in the documentary that I was using an enclosure, and in fact, make the enclosure part of the story. I’d let the viewer “in on the secret” by revealing how I was making the film.

I envisioned creating a semiwild situation in which a mother cougar and her kittens would be accustomed to my presence and allow me to film them without changing their behavior. While the cougars could not pursue large prey or roam without boundaries, they would be free to hunt small animals, communicate, show affection, and interact as a family.

With such a secretive animal, these behaviors would have been impossible to film in the wild. But in a large enclosure, I could film and record up close the sights and sounds that no one had ever seen or heard. Such an intimate look at this illusive animal would make people value it and want to protect it. That was my goal.

It was a tall order.

First on the to-do list was finding a site to build the enclosure. Working with a biologist, we found the perfect place—five acres (2 ha) of government land in the White Cloud Mountains of central Idaho.

The U.S. Forest Service granted my crew the land for a two-year study. The site was suitably rugged and included huge boulders, groves of aspen and pine trees, open grassy land, a stream, and a pond. We set wooden posts in the ground and connected them with chain-link fencing. Three tents just outside the fence would be our home for two years.

We also had a plan for the cougar’s food—roadkill. We arranged for local authorities to notify us when a large animal had been struck on the road by a vehicle. Then we’d head out, scoop up the carcass, and bring it to the enclosure for the cougar to find and feast on.

It was a good setup and a good plan. Now all we needed was a cougar.

After a long search, we located a 110-pound (50-kg) female. She had been raised in captivity, yet she maintained her wild nature. Perhaps she was a bit too wild or simply too much to handle, because the owner was going to have her put to sleep!

Upon hearing such disturbing news, the zoo in Boise, Idaho, bought the cougar. But the zoo had little space for her, and officials there were delighted to let us provide her with a home.

Two things made this cougar the ideal choice: One, because she had been raised in the presence of humans, she was already used to having people around. Two, she was pregnant. The kittens would be born in just a few months.

I could hardly wait. How does a mother cougar interact with her kittens every day? How does she care for them? What does she teach them? I had so many questions, and I wanted to capture the answers on film and show the world.

The pickup truck backed up to the entrance of the enclosure. It was a warm day in late spring. I let out a grunt as I helped ease the steel crate off the truck and gently onto the ground. I slid open the door of the crate and the feline mother-to-be walked out calmly without even looking at us.

Good. The less attention paid to us the better.

The bright sunshine made the cougar’s tan fur glow golden. Her impressive muscles flexed with each stride as she went about exploring her new home. Using her sharp claws and long tail for balance, she skillfully crossed streams on fallen tree trunks. Her powerful magnificence made me gasp. Then she trotted away into the aspens and disappeared. Compared to the pen in which she had been raised, this habitat offered boundless freedom.

We gave her a few hours to acclimate to the new surroundings, and then set off on foot to find her.

It wasn’t easy. With the cougar’s keen sense of smell and sharp eyesight, I’m sure she knew where we were practically at all times. By comparison, our senses were dull, and we had to look and listen with all the intensity we could muster. She knew how to hide just by being still. No doubt she was lying low, uncertain that we meant no harm.

Finally, we spotted her. She crouched in the tall grass barely 20 yards (18 m) away—a distance that she could close in two leaps if she wanted to.

We made eye contact. The big cat remained absolutely frozen, watching our every move intently. Suddenly I felt vulnerable, more so than I ever had. I knelt down slowly with my camera hoisted on my shoulder. My sound technician Peter, with his equipment, and my assistant Jake, carrying a large stick, did the same.

The cat continued to eyeball us from her crouched position. Then she raised and wiggled her hindquarters. That got me nervous. Anyone who has seen similar behavior from a house cat getting ready to pounce could guess what happened next…

She suddenly sprang.

We quickly rose to our feet, terrified. This wasn’t a squirrel or a fox coming our way; it was one of nature’s strongest, fastest predators, and she had us in her sights. We started yelling as loud as we could, “Hey! Hey!” and “He-yah! He-yah!”

I exhaled with relief as the cougar suddenly veered off in another direction. But, my relief was short-lived.

She stopped, turned around, and looked at us again. Was she going to make another run at us? My heart was pounding. My knees became almost too wobbly to hold the camera steady. But we stood our ground. Then without warning, she attacked.

With long strides, the cougar ran right at Jake and wrapped her muscular forelimbs around his waist. The force of the impact knocked the stick from his hands. He twirled reflexively to break away, but the cat held on, hopping on her hind legs to maintain balance as she also twirled. It was like a dance, but one that could have deadly consequences.

The cougar looked like she was going to climb up on Jake’s back when Peter ran to Jake with his microphone boom raised like a baseball bat. The threatening stance seemed to do the trick, because the cougar released her grip and ran off.

Jake was shaken but unharmed, a sign that the cougar did not intend to hurt him. She most likely was just playing a cat-and-mouse game, following her urge to stalk and test her skills. That sort of game can turn out badly for the mouse, so I was deeply concerned for the safety of my crew.

Not that it kept us away. Each day, we entered the enclosure to look for the cat, to observe and film. She never attacked us again. Maybe she just wanted to send a message during that first encounter. Message received!

We kept our distance and she kept hers, at first. But each day we inched closer and closer. Soon she got used to our presence and we reached a level of comfort and trust.

In fact, as time went on, the cougar even displayed affection. She would sometimes press her body against my leg and purr. It wasn’t a quiet purr like a household cat makes; her purr was more like an idling motorcycle.

At other times, she would stalk and chase us in a friendly game of cat and mouse. Well, friendly to her—we were the mice. We had gotten used to these games and were no longer fearful. But, we were always on our guard and watchful of any sudden change in behavior.

Our trusting relationship developed just in time, for soon the cougar gave birth to three male kittens.

We found the den amid a sheltered rocky outcrop. The kittens were just minutes old. Their spotted fur blended in with the ground, offering some protection against other predators. The helpless kittens’ eyes were closed and their little ears lay flat against their head. The newborns would remain blind and completely dependent on their mother for 10 days.

One by one, she gently picked them up by the scruff of their neck in her jaws and laid them in a soft bed of pine needles. Then she cleaned them with her large, rough tongue. When a kitten cried out with a squeaky rahr, rahr, the mother gave a few more reassuring licks.

These were the intimate sights and sounds I most wanted to capture, like the mother nursing her kittens—a tender moment perhaps never seen with cougars in the wild. There were many such moments of peace and tranquility between parent and young. There were other moments of high-energy training between teacher and student.

For instance, one day I watched with keen interest as a kitten tugged at one of his mother’s ears while she lay on the ground. Playing along, she gently laid a massive paw on his head like she was petting him. Then he saw her tail—a long rope of fur waving lazily in the air. It was like the tail was daring the kitten to grab it. The kitten took his chance and pounced. He bit and pawed at the tail for a few seconds, until his mother decided enough was enough and brushed him aside.

Every moment of play was actually a valuable lesson. The growing kittens were learning how to stalk and take down prey by sneaking up on each other and play fighting. These bouts were like friendly wrestling matches, but with teeth.

By autumn, the kittens were learning to hunt real prey, from mice in the fields to ducks on the pond. They were becoming increasingly wild, too.

They hid from me more often, and hissed when I approached. I was glad. One day they would be released into the wilderness, and I didn’t want them to get too comfortable with people. I didn’t want them to get used to having a harmless camera pointed at them, either. Hunting cougars is legal in many western states, and the next piece of equipment that was pointed at them might be a rifle.

When I started the cougar project, there was no guarantee of success. A lot could’ve gone wrong. The mother might never have accepted me, or the crew, into her world. She may have chosen to hide her young from the watchful eye of my camera lens. Or she may have turned aggressive, making the project too dangerous to continue.

Fortunately, none of these things happened. We were able to show the cougar not only as a powerful hunter but also as a nurturing parent and a patient teacher. We even revealed the sounds of the cougars’ world—from the chirps, purrs, mews, and growls of their language to the shoulder-shivering scrapes of the sharpening of the mother’s claws against a tree trunk.

The following spring, the young cougars reached the age when they normally go their separate ways. They were ready.

The mother was too familiar with humans to survive in the wilderness, so she was taken to a large preserve to live out her days in safety. The young cougars had a less predictable but more natural future.

We flew them by helicopter to a remote area of Idaho. Thanks to instinct and lessons learned as kittens, they were now self-sufficient and able to live a truly wild life. They stepped from their crates and never looked back. In a few days, the brothers would head in different directions to establish their own territories. They were free.

My cougar adventure was over, but theirs were just beginning.

What next? That’s what I asked myself as we removed the fencing and any trace of human activity at the cougar enclosure.

I was itching to start another project. As before, I wanted to do something that would inspire people to care about wildlife. The best way I knew how to do that was to make another film about the hidden daily life of an animal. It would have to be an animal that was largely misunderstood, an animal that was rarely filmed in the wild.

But, which animal?

To help me decide, I thought a little vacation was in order. Not Disney World or a Caribbean cruise. No, I needed a sense of peace—the kind of peace I get from a place of quiet natural beauty, a place where I could clear my mind. I decided to return to the Wyoming ranch in the Absarokas.

More than 30 years after I had spent the summer as a wrangler, I returned as a guest. For company, I had a stack of books about animals. I was going to pore over them for a few weeks in between hiking and fishing. Somewhere in the research and the inspiration of the mountains, I figured I’d find the subject of my next film.

I didn’t know the answer would hit me like a lightning bolt.

On the second day of the trip, I received a phone message that my cougar film, called Cougar: Ghost of the Rockies, had been chosen as the first episode of a nature TV series. I was overjoyed. I felt like a 16-year-old again, full of boundless energy.

I had the irresistible urge to make a climb that had been one of my favorites as a teen. I remembered that the view at the top was spectacular. I stepped my way through a stand of white pines to the base of a hill. I scrambled up the rocky slope, hunched over to keep my balance. At the top, I stood up straight to take in the view. Suddenly, I froze like a statue.

On the alpine meadow below me stood a gray wolf.

In a flash, my mind raced back to that day 30 years earlier when I had seen my first wolf. Now, in the same area, I was looking at my second. Could this be a descendant? I wondered about the possibility as I raised my binoculars to get a closer look. That’s when he saw me. Unlike the wolf that stared me down years before, this one was skittish and ran away at the sight of me.

In that brief moment, I knew that I had found the subject of my next film. I still didn’t know much about wolves, but I was about to begin a journey that would make me an expert in ways I never thought possible.

The first step in that journey was to separate fact from fiction. And when it comes to wolves, I learned that there was very little fact and a whole bunch of fiction.

Like most people, much of what I knew—or thought I knew—about wolves was based on the sayings, songs, movies, and fairy tales I had learned since childhood. A “wolf in sheep’s clothing” is someone whose pleasant personality hides sinister motives. In the fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood,” a wolf devours a grandmother and tries to trick her granddaughter into a similar fate.

Horror movies about werewolves—bloodthirsty half-man, half-wolf creatures—have been popular for generations. And who is trying to blow down the houses of the Three Little Pigs and eat the occupants? The Big Bad Wolf, of course!

Such stories and sayings show the wolf as a tricky, ferocious, evil creature—one to be feared, hated, and destroyed. Among those who held such perceptions were ranchers, as well as farmers who raised livestock. If a cow or sheep went missing, wolves were usually blamed.

Not that it never happened. These predators sometimes did kill a member of a herd, but the culprit was much more likely to be disease, weather, injury, or a predator other then a wolf, including domestic dogs.

I wasn’t completely surprised to learn how make-believe stories fed people’s misconceptions about wolves. But I was astounded and alarmed to learn how false perceptions had affected the wolf population. From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, about two million wolves had been killed in the United States, largely because they were seen as a threat to livestock. In fact, in 1915, the U.S. government hired hunters and called for the extermination of wolves.

It almost happened.

The government paid hunters for each wolf they killed. By the time I started to research my wolf film, this beautiful animal that once inhabited forests and plains from Maine to California existed only in small pockets of the United States. At the most, no more than a handful of wolves roamed the entire American West. Even though they were protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, their numbers were still dangerously low.

More importantly, attitudes about wolves had changed little, especially among the ranchers and big-game hunters who shared the environment with this animal. It was personally disheartening. These were my neighbors and friends, yet our views of wolves were very different. Many people still considered them to be aggressive killers. But the more research I uncovered, the more I saw wolves as curious, intelligent, and even shy. I knew they were getting a bad rap.

I couldn’t really blame people for their attitudes, though. Myths die hard, especially in the absence of truth.

In 1990, we knew surprisingly little about the nature of wolves. We had measurable facts—things that you could attach a number to—like a wolf’s size, how far it roams, how long it lives, things like that.

We knew wolves live in packs, but we had little idea about how they live. We knew almost nothing about the secret, hidden lives of wolves. I needed to change that. I needed to show people a side of wolves they never saw, never even knew existed. Perhaps that information would help replace myth with truth.

I felt the only way to discover that truth was to live with wolves.

So, I decided to assemble a wolf pack to observe and film within the world’s largest wolf enclosure. I had no idea what I was getting into and how difficult the road ahead would be, but I knew that I was doing the right thing. I was certain that if only someone would take the time to listen, the wolf would tell its story. I was willing to listen.

So was a certain zookeeper in Washington, D.C.

Jamie and I had kept in touch ever since we met on a trip home from Africa three years earlier. She was as excited as I was when I told her about my plans to live with wolves. We both knew this was a much more ambitious undertaking than the cougar project, and she understood why I had to do it.

In the early days of the project—before Jamie joined me in Idaho—I depended on her advice and support through letters and conversations. I still remember the joy I felt as I wrote her with some thrilling news.

“I found it!”

That was my message in a nutshell.

In a letter to Jamie, I described how I had found the perfect place to build wolf camp. It was in the Sawtooth Mountains, across the valley from where cougar camp had been.

I had explored other mountain ranges in central Idaho, but I could never find a place that had everything the wolves would need. Then I discovered Meadow Creek. It’s an area of meadows, forests, creeks, marshes, and ponds, all near the base of the Sawtooth Mountains.

This place was really off the beaten path. I took a dirt road across two ranches, and when the road ended, I got out and walked. The landscape changed dramatically as I hiked up a slight incline. It’s amazing the difference a little change in elevation makes! Instead of the dry sage of the ranches, I suddenly found myself in a green, grassy meadow.

It was like a piece of paradise. A mountain brook trickled past me on my left while bright yellow aspen leaves twisted and turned in the breeze on my right. In front of me stood a deep green forest of towering lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and spruce. And above that rose the majestic Sawtooths. Their summits formed a jagged gray ridge against the deep blue sky.

Meadow Creek had everything I could want. It was remote enough that people wouldn’t wander by and disturb the wolves. In fact, people would have a hard time finding this place even if they were looking for it. Yet the site could be reached by an equipment truck, which would be needed to haul in materials to build the enclosure.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/national-kids-geographic/running-with-wolves/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

National Kids

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Discover the wonder of wolves from Emmy-award winning filmmakers Jim and Jamie Dutcher as they tell their story of the six years they watched, learned, and lived with the Sawtooth wolf pack.Adventure, friendship, and family come together in this riveting memoir as two award-winning filmmakers take you through the experience of the years they spent living in the wild with a real-life wolf pack. Jim and Jamie set out to show the world that instead of fearsome beasts, wolves are social, complex, and incredible creatures that deserve our protection. Deep in the mountain wilderness of Idaho, they set up Wolf Camp, where they spent years capturing the emotional, exciting, and sometimes heartbreaking story of their pack.Meet Kamots, the fearless leader. Learn from wise Matsi. Explore the forest with shy Lakota. And watch as adorable pups grow from silly siblings to a devoted pack. See how these brave wolves overcome all odds, battling mountain lions and frigid temperatures. Most of all, discover the surprising kindness, compassion, and devotion that Jim and Jamie discovered by living with wolves.