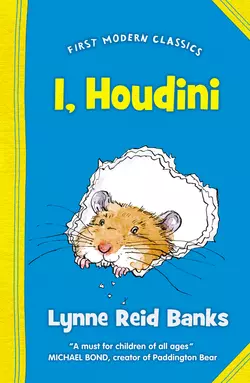

I, Houdini

Lynne Banks

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Houdini is no ordinary hamster. He is an escapologist with an exceptional talent for getting out of cages and urge to escape leads him to all kinds of adventures…Published into the First Modern Classics list, fantastic stories for young readers.He may look like a small, furry pet, but really he is a Wild Creature – a freedom-loving hamster with a life-long passion for escape and a yearning for the Great Outside, leaving chaos and destruction as he goes.He tells his hilarious adventures with great intelligence and no modesty – for the world beyond carpets and floorboards can be a terrifying place…