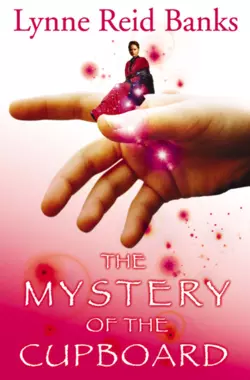

The Mystery of the Cupboard

Lynne Banks

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская фантастика

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 774.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: What will Omri find inside the eaves of his new home? Will there be more little figures that come to life?After Omri reads his great-great-great-aunt’s account, he longs to try the key. And when his friend Patrick comes to stay, nothing can stop him…