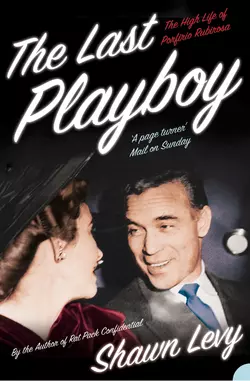

The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa

Shawn Levy

A scandalous story of money, drugs, fast cars, high politics, lowly crime, hundreds of beautiful woman and one man, Porfirio Rubirosa from the celebrated author of RAT PACK CONFIDENTIAL.The Dominican playboy Porfirio Rubirosa died at 8:00 am on July 5, 1965, when he smashed his Ferrari into a tree in Paris. He was 56 years old and on his way home to his 28-year-old fifth wife, Odile Rodin, after a night's debauch in celebration of a victorious polo match.In the previous four decades, Rubirosa had on four separate occasions married one of the wealthiest women in the world, and had slept with hundreds of other women including Marilyn Monroe, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Ava Gardner, and Eva Peron. He had worked as aide-de-camp to one of the most vicious fascists the century ever knew. He had served as an ambassador to France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Argentina and Vichy. He had been a jewel thief, a forger, a shipping magnate, a treasure hunter. He had held his own with the world's most powerful and notorious men including John F. Kennedy, Josef Goebbels and Juan Peron. He ran comfortably celebrity circles, counting among his friends Frank Sinatra, Ted Kennedy, David Niven, Sammy Davis Jr., and fellow playboy Aly Khan.He lived for the moment and, at his death, faded without a legacy: no children, no fortune, no entity – financial, cultural, even architectural – that bore his name. There will never be anyone else like Porfiro Rubirosa. Indeed, the really amazing thing is that there ever was. Shawn Levy – celebrated author of RAT PACK CONFIDENTIAL, and READY, STEADY, GO – has been given unique access to primary material including FBI and CIA files in his search for the last playboy.

SHAWN LEVY

The Last Playboy

THE HIGH LIFE OF PORFIRIO RUBIROSA

DEDICATION (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

FOR VINCENT, ANTHONY, AND PAULA,

WITHOUT WHOM THERE WOULDN’T BE MUCH POINT

CONTENTS

Cover (#ue4356f7c-fb8a-592b-89a0-7a3fb06ba823)

Title Page (#u27522bf0-8067-512c-95b8-ea9180e30851)

Dedication

THE LAST PLAYBOY (#u8a0f7632-4347-5379-9d4e-d15bee76cc50)

ONE IN THE LAND OFTÍGUERISMO

TWO CONTINENTAL SEASONING

THREE THE BENEFACTOR AND THE CHILD BRIDE

FOUR A DREDGE AND A BOTCH AND A BUST-UP

FIVE STAR POWER

SIX AN AMBUSH AND AN HEIRESS

SEVEN YUL BRYNNER IN A BLACK TURTLENECK

EIGHT BIG BOY

NINE SPEED, MUTINY, AND OTHER MEN’S WIVES

TEN HOT PEPPER

ELEVEN COLD FISH

TWELVE CENTER RING

THIRTEEN CASH BOX CASANOVA

FOURTEEN THE STUDENT PRINCE IN OLD HOLLYWOOD

FIFTEEN BETWEEN DYNASTIES

SIXTEEN FRESH BLOOM

SEVENTEEN RIPPLES

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Inspirations, Sources, and Debts

Works Consulted

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE LAST PLAYBOY (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

This, he reckoned, must be what they called a joint.

Normally in New York he didn’t go into joints. The Plaza, El Morocco, the Stork Club, the Copa, “21”: That was the sort of thing he liked. He was in the city so rarely, he was only interested in the best of it.

In Paris, of course, he knew such places, cafés and bars and clubs where you might meet a killer or somebody with an interesting business idea or a woman who would change your life—or maybe just a few minutes of it. But this, this had something of the savor of a café back home, one of the places along El Conde—an air of abandon and indulgence and danger. It was dark, spare, ominous. He liked it.

Besides, the best places were, how to say it, a little chilly right now. All this talk: newspapers and the television and people on the street and the ones they called “the right people.” The snobs and the writers hated one another, but to him they seemed very much the same.…

He had nothing to fear, nothing to hide, nothing to be ashamed about. But he didn’t need the headache of answering questions and being stared at by gossips and trying to figure out who would talk to him and who wouldn’t.

This place would do just fine, then: convenient, quiet, anonymous.

He had agreed to meet the newspaperman because he needed to get his own story out and he was assured by friends that he could trust the fellow. Earl Wilson he was called: owl-faced, a little thick in the waist, an easy laugher, a good listener.

Right now, he needed someone to listen—and then go and tell it in the way he wanted it told. All around New York the most horrible things were being said: He was a threat to his new wife; he was only interested in her money; he was some kind of villain or crook or gigolo. People knew nothing about them: He had known Barbara for years; she was charming, vibrant, delicate, cultured, creative; why shouldn’t he truly love her? And in Las Vegas, that madwoman with her press conferences and her eye patch and her ridiculous lies about what he had said to her and what he felt. No wonder people were giving him funny looks.

No, his own voice had to be heard, and for that he needed someone neutral, someone who would tell the truth about him: Earl Wilson, his new best friend.

They sat at midnight in a booth in the back of the Midston House bar on East Thirty-eighth Street, one freezing night, one of the last of 1953. They drank scotch—scotches—and he nibbled from the bowl of popcorn the waitress had put on the table when they sat down. “My bachelor dinner,” he joked.

Some pleasantries, and then the questions.

This was Barbara’s fifth wedding and his fourth. Why would anyone expect it to work out?

“Wonderful Barbara brought something new and different into my life,” he said, “and I will not be like her other husbands. I will make her happy at last.”

Next, Wilson wanted to know, like they all did, about the money: Barbara was said to have $100 million; was he after it?

“Riches to me don’t count,” he said sweetly. “I don’t need anybody’s money. I have plenty of my own. We will be married like civilized people under the law of separate property. What property she has is hers and what property I have is mine.”

He didn’t, of course, mention the prenuptial contract he had signed that very afternoon: $2.5 million on the barrelhead, plus future considerations, of which he also had plenty of his own. Let the great reporter find some things out on his own.…

“Is she ill?” Wilson asked.

“Ill?”—a laugh, with a little scorn in it, which he caught almost as quickly as he’d shown it. “Not at all, she’s the healthiest woman—it’s fantastic! Yes, she was in Doctors Hospital, but only to rest. And now, my God, what a vitality! She’s so strong that when she shakes hands I say, ‘My God, where did you get all that weight?’”

“But I thought she was slender from loss of weight.…”

“Oh, no. I don’t like skinny girls—and she’s all right!”

They laughed a little and Wilson wrote.

And what about this business in Las Vegas, Zsa Zsa claiming he had asked her to marry him and that he had hit her when she refused him?

Now he was impatient.

“Zsa Zsa is just trying to get publicity out of Barbara and me, and I don’t think it’s ladylike.”

The writer kept his eyes on his notepad, scribbling, silent.

The man seated across the table remembered who he was—a public figure, a glamorous consort, a world-famous lover, an intimate to power and wealth and sensation. He could breeze through it. He would have to get the smile just right.…

“Barbara is such an intelligent girl,” he continued. “She understands human nature so well; she’ll know it’s all ridiculous. She’s one of the most intelligent women anybody ever met.”

They returned to small talk: who would attend from the bride’s family, where would they honeymoon, where would they live.

And then, nicely buzzing, he rose and excused himself.

Tomorrow was going to be a big day.

How did they say it in English?

Like a zoo.…

ONE (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

IN THE LAND OFTÍGUERISMO (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

When he sat down and tried to remember it all, in the ’60s, near the end of his life, he began, naturally, with his childhood, as he could retrieve it: a series of brief scenes, like film clips, set in his intoxicating, perilous homeland—random moments, yet with a cumulative impact that shaped him irrationally, subliminally, imparting to him tastes and biases that he never lost. A man of the world, he forever defined himself by reference to a specific place.…

Rifle fire; early morning; a child springs up in bed. “At most,” he remembered later, “I was three years old.”

Not long after, in the dead of another night, the child startles awake once again, panicked to find himself alone. “I was in the habit of sleeping with a cat.” He leaves his bed to seek his feline bedmate, and is shocked to find strangers everywhere. “The house was filled with armed men asleep in the hallways.”

And maybe a year later still, a mounted rider approaches. “Without getting off his horse, he took me in his great big hands and pulled me up to its neck, in front of him. One click of his tongue, and we were off! ‘Careful Pedro, careful! He’s so little!’ shouted my mother. My father laughed. The night was gentle and sweet. I had the horse’s mane gripped in my hands. I heard his hard breathing. I wished the corral would never end.”

Gunshots; soldiers; a strongman; a horse; a shouting woman; the thrill of speed; the danger; the Cibao Valley of the Dominican Republic in its Wild West phase, circa 1913: the earliest flashes of memory in the mind of Porfirio Rubirosa.

In the early twentieth century, when a little boy was being imprinted by these memories, the Dominican Republic was, as it had been for centuries prior, a place where fortunes might be made and dominions might be established—but only after painful struggles that were not always won by the most honorable combatant. It was a place that tended to favor unfavorable outcomes. Indeed, despite the noble charge and historic pedigree of the first white men who stumbled on it, the first European to settle the island and live out his days there was, in all likelihood, a rat.

Just after midnight on Christmas Day, 1492, a Spanish caravel gently foundered onto a coral reef beside the large island that its passengers had dubbed Española—Hispaniola in English—the sixth landmass it had encountered in the dozen weeks since departing the Canary Islands.

By dawn, the ship had broken up and sunk.

At that moment, Christopher Columbus had a complete fiasco on his hands.

A nondescript Genoese merchant sailor who made his home in Portugal, Columbus had sufficiently gulled the queen of Spain with his outlandish theories about a sea route to Asia that she arranged a backdoor loan for his enterprise from her husband’s treasury. Isabella invested enough in his pipe dream for Columbus to acquire supplies, a crew, and three ships—the largest of which, the Santa María, had just become the first in several centuries of fabled Caribbean wrecks.

Gold Columbus reckoned he would find, and jewels and spices and a path to the riches of the other side of the world that would make trade with the hostile Moors unnecessary. But to date, he had gleaned significantly less than his own weight in treasure, and with the Santa María sunk, he was down to two ships for the trip home.

So he formed a landing party (which included at least one stowaway rat, whose bones—distinct from those of native species—would be discovered by archeologists centuries later), and he went ashore. There he shook hands with the leader of the native Tainos, accepted a few gifts, and founded a colony, named La Navidad in honor of its Christmas Day discovery. He looked around for a mountain of gold and, seeing none, packed up the Niña and Pinta and went home.

Ten months later, having raised enough capital to fund a fleet of seventeen ships, he returned, intent on exploiting the fonts of gold he believed the island nestled. In January 1494, he founded a second settlement, named La Isabela for his patroness, and used it as a base from which to explore the interior of the island.

Specifically, Columbus was curious about the Cibao, a highland valley that meandered eastward along a river from the northern coast through two mountain ranges and met the sea again in swamplands in the east. On his previous trip, he’d been told that the valley was home to fields where chunks of gold as large as a man’s head lay about just waiting to be gathered. He forayed inland and found the valley—he labeled it La Vega, “the open plain”—but there was no gold. He was nevertheless impressed: The soil was rich, the climate mild, the river navigable, the mountain ranges, particularly to the south, formidable. If he had been a settler and not a buccaneer, he might have colonized the place for ranching and farming. But his priority was raw wealth. He moved on.

Columbus would make two more trips to Hispaniola, still looking for gold, still luckless. He and his men would found the city of Santo Domingo on the southern coast, a deep harbor from which Spain would rule the Caribbean and the Americas. In the coming centuries, the island, genocidally cleansed of natives, would be a keystone of the Spanish slave trade and an important colony of plantations. The Cibao would yield real wealth—fortunes based in coffee, cattle, sugarcane, tobacco—but nobody would ever again venture there in search of treasure.

Indeed, those who did choose to settle there were often lucky just to keep their heads. For hundreds of years after Columbus, the island, despite its import as a staging ground, would be overrun by a continual string of colonial and civil wars and the never-ending scourges of disease, poverty, rapine, and neglect.

Hispaniola fell into ruin in large part because it was, uniquely, colonized by two European powers. The Spanish contented themselves with dominating the eastern side until the French established a foothold in the west in the mid-seventeenth century. The island, long neglected by Spain in favor of colonies that yielded more in the way of obvious riches, suddenly seemed a valuable commodity, a point of contention. Back and forth forces of the two rivals fought, trying bootlessly to vanquish one another until the island was split by treaty in 1697 into two nations: Haiti and Santo Domingo. The plantations of Haiti, under French guidance, prospered, while Santo Domingo lapsed into a tropical torpor more typical of Spanish rule: Slaves bought their freedom and married with Europeans; infrastructure, never the strong suit of Spanish colonialism, was neglected; the economy declined into stagnation. When the Haitian slave rebellion led by Toussaint L’Ouverture spilled eastward over the border in 1801, there was little resistance. Under a rampage of murder, rape, and butchery, Santo Domingo simply fell into French hands for twenty bloody years.

Then a hero arose: Juan Pablo Duarte, a homegrown nationalist who sought freedom not only from the Haitians but from Spain. Starting as a governor of the Cibao, he routed the Haitians and the Spanish, but he failed to bring true unity to the nation. From the expulsion of the Haitian forces in 1844 through the expulsion of the Spanish in 1865 and onward toward the new century, the Dominican Republic, as it had been renamed, was ruled by chaos. Presidents came and went in brief, nasty succession; unrest and poverty were epidemic; and a species of tribal warfare ground on. There were puppet heads of state, bloodthirsty chieftains, coups and battles and massacres and ambushes and ceaseless conflicts. It seemed the destiny of the country always to roil.

Into this quagmire, in San Francisco de Macorís, a small city of the swampy eastern portion of the Cibao, Pedro Maria Rubirosa was born in 1878. The Rubirosas were an educated family, with a tradition of public service. But in this wild era, public service meant choosing a side in the never-ending civil wars. Although he was well schooled, by the time he was in his teens, Pedrito Rubirosa was riding with bands of soldiers. And by the time he was in his twenties, he was leading them.

Half a century later, his son regarded a tintype of his father from these days: “In the photograph in my hands, my father already shines like an adult. With his strong cheekbones, his powerful head, his thick moustache, his gaze falls arrogantly from a height of five-foot-ten. He doesn’t seem at all an adolescent: he is a man by deed and right. They called him Don Pedro.”

Don Pedro, his son related, “was always in a campaign. It was the time of basements stocked with rifles and houses filled with soldiers. In effect, my father negotiated a ceaseless labyrinth of skirmishes, assaults, forays, and guerilla attacks.” And through a combination of personal qualities and historical accidents, he became, in the military algebra of the era, a general. In this context, mind, a general wasn’t a professional soldier promoted after of a long career of battle and governance. He was, rather, the smartest, luckiest, boldest in his troop, responsible for arming, feeding, and housing his men, and for strategizing and liaising with the other bands of soldiers with which they were allied. It was a position earned as much with guts as brains. “A general who didn’t march in front of his men didn’t exercise great dominion over them,” Don Pedro’s son said. “This explains why Dominican officers rarely died in bed of old age, like their European colleagues, and why rapid promotions permitted a youngster of 20 to become a general.”

But there was another quality to Don Pedro, even more important than his daring or his brains or the poor luck of his senior colleagues. As his son put it, “One had to be a tiger to command a group of tigers.”

Tiger: tigre in Spanish, tíguere in the local argot, in which the word came to represent the essential defining characteristic of the Dominican alpha male. The Dominican tíguere was, like the ideal male in all Latin cultures, profoundly masculine—macho, in the Castilian—but had dimensions unique, perhaps, to the Creole culture of Hispaniola. He was handsome, graceful, strong, and well-presented, possessed of a deep-seated vanity that allowed him the luxury of niceties of character and appearance that might otherwise hint at femininity. He could move with sensuality or violence; he was fast, fearless, fortunate. A tíguere emerged well from nearly any situation that confronted him, twisted any misfortune to an asset, spun a happy ending of some sort out of the most outrageously poor circumstance; he was able, being feline, to climb to unlikely heights and, should he fall, always landed, being feline, on his feet. The tíguere bore the savor of low origins and high aspirations, as well as a certain ruthless ambition that barred no means of achieving his ends: violence, treachery, lies, shamelessness, daring, and, especially, the use of women as tools of social mobility. A tíguere always married to advantage.

If there was an element of the outlaw or the delinquent in the tíguere, if only in his early days, he could hope to transcend it and reach the highest rungs of society—indeed, it was widely understood in Dominican life that an element of tíguerismo was essential to most success. To some degree, the Dominican male, if he was true to his blood and his culture, could be permitted virtually any impudence or trespass whatever. Adultery, theft, tyranny, violence, bellicose savagery, social cruelty, excesses of libido and appetite and greed: All could be ascribed to—and forgiven as—tíguerismo.

Pedro Maria Rubirosa clearly fulfilled the role of tíguere as a warrior and man of action. But he did so as well as a lover of women. “My father was a handsome man,” the son remembered. “His form was lithe, his eyes brilliant; he shone with every aspect of a gentleman. Women admired him.”

Among those admirers was a girl from his hometown, Ana Ariza Almanzar, granddaughter of a Spanish general who had fought in Cuba. At the dawn of the new century, Don Pedro took this well-bred young woman as his wife.

They began their family with tragedy, losing at least one child before 1902; then a daughter, Ana, managed to survive the perils of tropical infancy. Three years later came a son, Cesar. The tíguere now had a male heir to boast of and to train.

It was a flush time for Don Pedro. The tyrant Ulises Heureaux, who had ruled the Dominican Republic with a ruthless hand for two decades, had been assassinated in the summer of 1899, and a period of relative calm had descended. Don Pedro’s daring, loyalty, and intelligence had recommended him to the new government, and he was appointed as governor of a string of small cities—first San Francisco de Macorís, then the coastal city of Samaná, then El Seibo, each posting finding him assigned farther from home as the warrior-politicians of the Cibao peacefully extended their influence.

In El Seibo, where he arrived in 1906, Don Pedro allowed himself the pleasure of other women. (Ana, her son would offer by way of explanation, “got fat after her first children arrived.”) With a local woman and her cousin he fathered four children en la calle, as the saying went: “in the street”: bastards.

He acknowledged them, though only one took his name. And then his duties called him back to San Francisco de Macorís, where the last of his legitimate children was born, on January 22, 1909. They named him Porfirio.

It was such a sparkling name: Porfirio Rubirosa Ariza (the Ariza a technicality, following the Spanish convention of retaining the matronym for legal purposes).

The surname was, of course, a given, and it meant “red rose.”

The Christian name, however, was something of a fancy, not a family name like that of the baby’s sister or an obviously historical name like that of his brother. There were some obscure antecedents: an ascetic Saint Porphyry of Gaza; Porphyry of Tyre, a mathematician and philosopher of Phoenicia, noted to this day for his treatises on vegetarianism and named after the purple dye for which his home city was famous (at root, the word “porphyry” refers to a shade of purple that naturally occurs in feldspar crystals). But Don Pedro and Ana probably had in mind Porfirio Díaz, the autocratic president of Mexico under whose hand that nation modernized itself into the envy of the Caribbean—a strongman whose career, like Caesar’s, would be worth emulating.

Ironically, soon after the baby was baptized, the great Díaz found himself falling into a struggle to maintain his rule—just as Don Pedro once again found himself commanding men in the field when yet another civil war broke out in the Dominican Republic in 1911. This was the campaign that formed the young Porfirio’s first memories: the rifle shots at dawn, the soldiers sleeping throughout the house, the cat that crept away in the night.

The boy would grow to remember, too, a fearful, devout Doña Ana: “My mother, who was very pious, lived at prayer … I remember her often curled up in the darkest corner of the house, praying.” Doña Ana Ariza Rubirosa may have seemed a pushover: born to a family of soldiers, married to a soldier, countenancing her husband’s infidelities, burying herself in counsel with the Virgin of Altagracia, draped demurely in black, growing plump. But there was steel in her as well. Take the way she saw to the woman who was making time with Don Pedro and then ran, unopposed, for the presidency of the ladies’ club of San Francisco de Macorís. On the day of the vote, with all the notable women of the city assembled and prepared to anoint their new leader, the outgoing president announced that she was so sure that they all approved of her successor that the election would be conducted by acclamation. “No,” came a voice. All heads turned to face the speaker, Doña Ana. “This woman is my husband’s lover,” she declared. “Under these conditions, I don’t think it’s possible to make her our president.” Shock; murmurs; a hasty conference of officials; and a new presidential candidate was impressed and elected. Ana got in her carriage, according to her son, “and returned home without saying a single word to my father about the scandalous scene she’d made. And he, after being told about the incident a few minutes later, also remained silent.”

Perhaps the scandal she’d created with her outburst was too great; perhaps Ana feared in time of civil war for the safety of her children (“Careful Pedro, careful! He’s so little!”); perhaps Don Pedro, in his mid-thirties, had grown too comfortable, too encumbered, too secure to lead troops; perhaps his intellect was recognized by his colleagues as more useful to them than his bravery; perhaps he was in flight from enemies. For whatever reason, in 1914, soon after Doña Ana’s bold gambit, the Rubirosas found themselves sailing away from their bellicose, agitated little country. Don Pedro had been named to serve in the Dominican legation in St. Thomas, the Virgin Islands.

At the age of five, Porfirio Rubirosa had begun his lifetime of wandering.

TWO (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

CONTINENTAL SEASONING (#u614b1e72-a53e-5e2b-b154-d2f0c847e9a7)

In a one-room schoolhouse—a large hut, really—the teacher bent down to address his new pupil, who spoke neither French nor English, and handed him a small violin. It was time for the school orchestra to practice, and everyone took part.

But this slim little boy didn’t know how to play. He took his instrument and dutifully joined his classmates, who included his older brother and sister. He stood in the back. The others, following the teacher’s directions, began to saw away at their music. The boy began to cry.

The teacher spoke to him kindly: “Act as if you can play, that’s enough.”

And the child, mollified, did just that.

And he thought to himself, “Is the world of grown-ups, perhaps, a world in which appearances are all that matters?”

St. Thomas, where Porfirio Rubirosa learned how not to play the violin, was an Antillean idyll for Don Pedro’s family. For less than a year they lived in a small house in the middle of a sugarcane plantation while Don Pedro saw to his ministerial duties. Back home, the situation was still dangerously unstable: Haiti too had fallen into turmoil, and the United States, to which the Dominican treasury owed a sum it couldn’t possibly repay, had taken a more active interest in the rising chaos on the island. Fewer than twenty years earlier the Yankees had driven Spain out of Cuba; now events in Europe—where a continent-wide war had been set off—made the securing of the Caribbean a matter of increasing import in their eyes.

From St. Thomas it was impossible for Don Pedro to read the subtleties of the power struggle back home. So he chose, in a sense, to turn away from it. In 1915, he accepted another diplomatic appointment, one that would have an indelible impact on himself and his family. He would represent his country at its embassy in France.

This new charge meant more than just uprooting his wife and children. Don Pedro was being sent to the most prestigious posting in the world by a government he couldn’t be sure would exist from week to week and at a time when his new home was itself embroiled in war. Even as he could anticipate with zest a new life in Europe, the onetime warrior of the Cibao sobered at the weight of the prospect. And Porfirio, sensitized by his musical experience to the language of appearances in the adult world, noticed the metamorphosis. “My father had changed,” he recalled later. “No longer did he wear a pistol in his belt or a saber between his shoulder blades. He was now Chief of a diplomatic mission.”

And not just any diplomatic mission, of course, but Paris—the capital of the world insofar as it had one. “We have perhaps forgotten,” Don Pedro’s son would write, “that before the war of 1914, the prestige of France throughout Latin America was immense. From the other side of the Atlantic, France seemed the ideal marriage of the style of the ancien régime with the dynamism of revolution.”

Getting there was a fantastic adventure. The family sailed on the Antonio Lopez to Gibraltar, where they were greeted not with flags and salutes but with gunfire; British authorities suspected that among the ship’s passengers was a German spy disguised in frock and wig. Again the young boy’s imagination was fired by the strange simulations of the grown-up world: “The mustached warriors of the Caribbean had been succeeded by Europe and spies dressed as women!” After a search, the Antonio Lopez was permitted to disgorge its passengers. The Rubirosas headed north by train. Ana and Cesar were left in Barcelona, the nearest important Spanish-speaking city to Paris, to continue their schooling. Porfirio continued on with his parents.

The city to which Don Pedro had been posted was a wonder to his son. There were strange new creature comforts, like the kidskin coat he wore as a redoubt to the astonishing cold. There were the impressive signs of war: cannons encircling the Arc de Triomphe, soldiers in the streets and the cafés. And there were glamorous sensations of the sort never seen in San Francisco de Macorís. On the first full day the family spent in the city, Don Pedro took his son to a cinema, where the boy sat in awe watching the great star Pearl White in The Mysteries of New York, a movie serial filled with barbaric cruelties, thrilling chases, impossible situations miraculously escaped from, and a fiendish villain, the Clutching Hand, who preyed on the beautiful heroine for occult reasons only he fathomed. One image would linger in the youngster’s mind for decades: Pearl White trapped in a tube that slowly filled with water, threatening to drown her.

The family made its home first in temporary quarters on Boulevard Saint Germain and then within shouting distance of the Arc de Triomphe at 6 Avenue Mac-Mahon, an address that would exert a nostalgic pull on Porfirio throughout the decades in which he would live in Paris. The house sat in the true symbolic center of the city, which perhaps accounted for the number of times the Rubirosas found themselves collaterally involved in aerial bombardment by German planes, which regularly cut through the sky, flaunting their black-and-white crosses. Most French families fled underground at the sound of enemy aircraft, but Don Pedro reasoned that this would be a terrible hideaway, a lair of death by crushing or suffocation or slow starvation. Rather, he insisted that they stay above stairs, where they endured the occasional air raids and the accompanying thunder of bombs with stoicism the English would have admired: Don Pedro reading his newspaper, Porfirio playing with toys, Doña Ana saying her rosary. Only after the house suffered a truly astonishing concussion one afternoon when a bomb hit the nearby Avenue de la Grande Armée did the brave tíguere rethink his policy and direct his family to belowgrounds safety.

These close calls exerted an accumulative toll, and the Rubirosas soon moved to the coastal city of Royan, less than two hundred miles north of Spain on the Atlantic coast. There, Cesar and Ana rejoined the family and Don Pedro received some shocking news: The civil war back home had so escalated that marines from the United States had occupied the Dominican Republic.

Don Pedro had foreseen as much, according to Porfirio. “My father,” he remembered, “realized that this constant civil war would only lead to catastrophe—the loss of national independence or dictatorship.” But preparing for such a blow didn’t lessen its impact, turning Don Pedro permanently from a man of action into a man of words, ideas, and policies. “Suddenly,” Porfirio noted, “with the decisiveness that characterized him, he changed into a quiet man and began to study, with the help of a professor who came to the house, the worlds of economics, politics, international relations and languages.” He was particularly taken with the law, and built a small library in his house of the imposing legal volumes published by Dalloz. It was, in his son’s eyes, a poignant metamorphosis: “In my childhood, I never saw my father without a Smith and Wesson at his side; in my adolescence, in turn, I never saw him without a Dalloz under his arm.”

Despite the example of his father’s study, young Porfirio realized that he wasn’t cut from quite the same material. “Books didn’t find in me a very faithful friend,” he confessed, “nor did the professors find a conscientious student. The only things that interested me were sports, girls, adventures, celebrities—in short, life.”

Once the family was back in Paris after the end of the war, Porfirio—who watched the victory parade along the Champs-Élysées from the prime vantage of the roof on Avenue Mac-Mahon—attended a string of schools, making no impression in any of them save as a goalkeeper in soccer, a skill that he maintained into his twenties. He was enrolled in some of France’s finest seats of youthful learning: l’Institut Maintenon, l’École Pascal, and the lycée Janson-de-Sailly, all in Paris, and l’École des Roches in Verneuil-sur-Avre, some sixty-five miles east by train. Nothing took. He lived only for the spectacles of Parisian life, for thrills and novelties and chums and escape … and to get out of his short pants.

Almost more than his first shave or sexual experience, the privilege to wear long pants on a daily basis was a symbol of achieving manhood for a young teenager of the era—a sartorial bar mitzvah for the Little Lord Fauntleroy set. At school, Porfirio had become chummy with a Chilean boy, Pancho Morel, and a boy named Jit Singh, youngest son of the maharaja of Karpathula. They were younger than Porfirio, but they didn’t have the protective Doña Ana as their mothers and had not only begun wearing trousers but had worn them into nightclubs in Montmartre, lording their mature adventures over their bare-kneed Dominican pal. He seethed.

Finally, when her son was sixteen, the painstaking Doña Ana allowed him the dignity of long pants. And as soon as he buckled his belt, he was off. From the first night he steeled his nerve and sauntered into a Montmartre nightclub, Porfirio Rubirosa was at home.

“I had a racing heart and boiling blood and a delicious impatience throughout my body,” he confessed later. “I remember the doorman, the music that came in waves, the diffused light that imparted mystery to the faces.… More than 30 years have passed since that night, and I still see the wet lips opening on white teeth and the eyes that shone like lights, and I hear the laughs that merged into one single strident trumpet blare.”

He wandered home at dawn, drunk on the atmosphere and the possibilities—as well as the libations. His parents had been up all night, worried sick, more grateful for his safety than angered at his presumption. Porfirio was chastened, and resolved privately never to frighten them again. But presently he realized that, truly, he felt only the slightest bit contrite: “I am, and will always be, a man of pleasure.”

And why not? Fate and history had brought him to come of age in one of the great seats of pleasure the world would ever know. “Those who didn’t know Paris in the ’20s,” he declared with certainty decades later, “don’t know what a nightclub is.” The interwar demimonde into which he flung himself was the stuff of legend. The Montmartre of the 1920s was no longer the bohemia of starving artists that it had been before the Great War; Pablo Picasso and his adherents had moved across the Seine to Montparnasse and founded a new enclave that would soon draw the Lost Generation of American writers and free spirits. In their wake, the neighborhood that sported such venerable outposts of debauchery as the Moulin Rouge, Le Chat Noir, and the Folies Bergère as well as such lower-rent cousins as Tabarin, Monaco, La Perruche, Zelli’s, Chez Florence, and Le Grand Duc, had become increasingly associated with a blend of criminality and pleasure that lacked the éclat of arty bohemianism. It was no longer an aesthetic wonderland but rather a carnival world of low life lived hard—no place for innocents.

And yet its denizens looked favorably on this ambitious Dominican boy. Latin men were, at the time, enjoying a unique cachet. The tango craze that had begun before the war was booming and had, indeed, been amplified by other musical fads imported from the Caribbean and South America, including the Dominican merengue. Latin musicians and idle young Latin men were everywhere, and they drew to their hangouts a clientele of slumming locals, many of them women; from afternoon on into the early morning hours, the clubs of Montmartre hosted a stream of Parisian matrons led provocatively around dance floors by younger Latin men who were paid for their time: gigolos (from the French word for a loose-moraled dancing girl, gigolette). These hired guns of the boites were glamorous in a sinister fashion that gave additional luster to their reputation as men employed for pleasure.

None other than the great Rudolph Valentino, who died of a perforated ulcer during the days of Porfirio’s induction into Parisian night life, had voyaged to America from Italy as a tango specialist and was said to have made his first living in New York as a gigolo. A young Latin man couldn’t help but admire and aspire.

But crazes, of course, are designed to fade. And although the Latin vogue was wearing out, Porfirio was still in luck. The new fascination in the Parisian demimonde was with American hot jazz and black musicians, singers, and dancers. The area of Montmartre below the Butte was the Parisian Harlem, teeming with African-American expatriates and dotted with hotels, bars, cafés, and nightclubs that catered to them. Once again, a boy from the Caribbean, of mixed blood, with café au lait skin and hair described as somewhere between wavy and kinky, would blend easily into such an environment, acquiring a liberal education in sensation and reckless living that would, obviously, ingrain itself in his spirit far more deeply than anything going on at school.

In this sexy, dangerous world, the game young Porfirio more than fit in, he was a hit. But his love affair with Parisian night life would prove, at least for the time being, a dalliance. Once again, in 1926, Don Pedro’s work called for the family to move. Another tottering government had been established in Santo Domingo—this one installed by the Americans, who had pulled out their troops to allow the locals a chance. The new regime assigned Don Pedro to its embassy in London; Porfirio would be schooled relatively nearby, in Calais.

As evinced by his decision to move the boy closer to where he himself would be, Don Pedro had some concerns about this boy who seemed more dancer than warrior. Porfirio was thin, wasp-waisted, coltish. And although he had an undeniable knack for sports, there were no obvious bulges of muscle on him, nor had his mettle ever been truly tested. Don Pedro arranged for him to be tutored in boxing. “The man of action still lived beneath the diplomat’s clothes,” he later explained, “and he wanted a solid son with quick fists.”

Porfirio did no better in his studies at his new school than he had at any of the others. But the boxing was another matter. Springy and quick, he was a natural. And even better, the gym was located in a louche part of town where the young man’s eyes were caught one afternoon by a sign reading Piccadilly Bar.

He went in. He ordered a drink. He made small talk. He had a good time. He came back. “I quickly became a regular,” he later boasted, “celebrated for my youth, my free way with money, my Dominican nationality, a taste for strong cocktails and a strong hunger for the ladies.” As in Paris, his race got him noticed and his cool, breezy, agreeable manner made him popular.

The taste of notoriety went to his head. He soon felt sufficiently full of himself to accept the challenge of a fight against a local champion named Dagbert. On the big night—the humming crowd, the smoke-filled room—a sense of grandeur infused the young fighter. For a round or so, he used his training, his wile, his wits to keep Dagbert safely at bay. Then he reckoned he could grab the advantage and got cute. Dagbert saw an opening and pasted him squarely. “I got hit right in the Adam’s apple,” he remembered. “I couldn’t breathe, I was suffocating, but I was saved by the bell. But by the end of the rest period, I still hadn’t recovered. Despite the shouting, I quit the fight. The thrills of the Piccadilly were less dangerous.”

It was the last proper boxing match in which he would ever take part, and, indeed, he quit his formal training soon after. But he didn’t quit leaving campus for lessons. He simply told the authorities at school that he was off to the gym and made a beeline instead for the Piccadilly, where he delved deeper into his cups until finally he was found dead drunk one evening by his scandalized schoolmaster. It was a terminal offense: He would not be permitted to return to the school after the summer holidays.

That was just as well, because by then Dominican politics had yet once more yanked at Don Pedro, pulling him from London back to Santo Domingo, where a seemingly stable government had been installed and was working toward elections. Don Pedro, now a seasoned international diplomat and legal mind, was thought more valuable at home than in foreign courts. He returned home and, with the chimerical hope that his wayward youngest son would straighten himself out in his absence, left Porfirio in France to finish his baccalaureate studies.

The freedom provided by his parents’ absence was absolutely intoxicating. Porfirio passed most of that summer partying in Biarritz with his wealthy schoolmates. “The images that come to my mind,” he recalled “are pictures of a brilliant sea beneath the sun, sports cars tearing through little towns, thés dansantes with women who acted like girls. Everything was the pretext for a dare: swimming, drinking, racing, love. Naturally, when we returned to Paris, we tried to extend the crazy atmosphere of our vacations. This was made easier for me because of my father’s absence.”

Don Pedro hired a tutor—“friendliness personified” as Porfirio remembered him euphemistically—but the boy was a confirmed debauchee by this point, as he gladly confessed. “I only opened the books that appealed to me, and those weren’t many. The only geography I was interested in was the geography of Paris’s night life.” He naturally failed to graduate.

And then he went home to Santo Domingo: “a brutal break from what I referred to at this time as ‘the life.’”

The exact details of his removal from Paris would prove a blur. The grown-up Porfirio would claim that he had been living with the family of his Chilean schoolmaster Pancho Morel and, upon failing his baccalaureate, received a telegram from Don Pedro ordering him to Bordeaux, where transit home had been booked for him on the Carimare. He claimed the boat docked in the Dominican port of Puerta Plata and that he traveled by car from there southward through the Cibao to join his family in Santo Domingo.

But another account emerged from a witness less disposed to putting a pretty shine on things. Leovigildo Cuello was a doctor who lived in Santiago, the chief city of the Cibao, and was friendly with Don Pedro. His widow, Carolina Mainardi di Cuello, would remember years later that a frightened, hungry, filthy Porfirio showed up at her doorstep unannounced and unexpected one day in 1928. His clothes were spotted with engine oil, and he had a fantastic story to tell: Having been cut off by his parents for his excesses and failings, he had spent several months in Paris living hand to mouth as a member of a Gypsy dance troupe that busked for money; summoned home, he stowed away in the engine room of the Carimare—hence his disheveled state—and needed some help to make his way to his family. The Cuellos cleaned and fed and clothed him and, despite his entreaty “please don’t let my father know,” phoned Don Pedro, who was visiting nearby San Francisco de Macorís and came to Santiago to fetch him.

It was hardly the happiest of reunions.

“I was wrong to leave you alone in Paris,” Don Pedro declared. “I took you for a man, and you’re just a ruffian.” He announced that he would bring his prodigal youngest son to Santo Domingo where a “double dose of studies” would be administered to him by a brace of teachers: a tutor for his baccalaureate exam, and a new member of the family—his sister’s fiancé, the attorney Gilberto Sánchez Lustrino—to prepare him for law school.

That was disappointing news. But it wasn’t nearly so deflating as Porfirio’s impression of the man who delivered it: “My father, in one year, had aged a great deal. Once so tall, he was doubled over. His cheeks had fallen. And his gaze was filled with a profound sadness.” At barely fifty, Don Pedro was falling into moral despair and was further cursed by a weak heart. He managed to engage himself in the affairs of the capital, but the process taxed him, to his son’s concern: “My father’s aspect worsened more each day. Nothing is sadder than the sickness and aging of a man who has asked much of his body and received it.”

To his surprise, Porfirio found Santo Domingo an agreeable successor to Paris.

For one thing, even though he’d left the island some fourteen years earlier, he felt its stir still in his blood. “I wasn’t more than a baby when I left my homeland,” he reflected, “but the echoes of infancy, on top of the stories told me by my parents, exerted an extraordinary force.”

The family lived in a three-story house on the corner of Calle Arzobispo Meriño and Calle Emiliano Tejera, in the midst of the city’s colonial zone. It was not the capital of the world, that was plain. In lieu of grand boulevards there were narrow streets whose gutters teemed with garbage that was hosed toward the sea several times a day. The great monuments of Columbus’s era—cathedrals, convents, hospitals, palaces—lay in untended ruin. Rather than nightclubs, there were impromptu dances in plazas or in private homes, from which music and light would spill out onto dark cobblestone streets in magnetic pools. The jeweled, befurred, painted, perfumed women who gave Paris such an erotic charge were replaced by damas straitjacketed by a nearly medieval propriety and their daughters, repressed into crippling shyness. Instead of the dizzying savor of modernity, there was a stolid adherence to old ways. The latest cars, clothes, music, ways of living: completely unheard-of.

And yet that didn’t mean there wasn’t some semblance of “the life” to be found. There was an agreeably languid pace to the Caribbean—the siestas and paseos and macho camaraderie. Porfirio was naturally drawn to the groups of raucous young men who gathered on street corners, in plazas, and in parks. A friend who met him at that time, Pedro Rene Contin Aybar, remembered Rubi as “tall, of good build, with an energetic face, thick lips, curly hair, an intense gaze and an agreeably deep baritone voice.” His acceptance among this new crowd was facilitated by his exotic pedigree as a Dominican raised in Paris: “I had a lot to tell them. They envied my free comportment, of course. And after the free life I had known, I took a certain wicked delight in scandalizing this closed society a little bit.”

At the head of a fast bunch, he whored, he drank, he showed off his sporting and terpsichorean skills—he was noted for something called an apache dance—and his small talent with the ukulele. It was the era when the merengue, the indigenous folk music of Hispaniola, blossomed into a jazz-influenced sound suited to the dance hall; some of the most infectious music ever produced in the Caribbean was being played nightly, live on stage for Rubi and his chums, and they adored it.

In the midst of this, Rubi evinced an entrepreneurial streak, establishing a boxing ring in the small plaza in front of the church of San Lázaro, in a lower-class neighborhood of the capital; admission to the fights, which featured such local phenoms as Kid GoGo and Kid 22–22, was a few pennies.

And he put his natural audacity and European sophistication to comic use among his chums. There was the day, for instance, when they were all standing on a corner of Santo Domingo’s busiest shopping street, El Conde, making mock-heroic protestations of chivalric devotion to passing girls who, in the manner of the day, wouldn’t even make eye contact with boys to whom they weren’t related. Porfirio approached one and took the bold initiative of snatching a notebook from her hand. The startled girl shrieked and ran off to a nearby tavern, only to emerge a few minutes later with her uncle, a local bully known as Suso García. He walked up to the boys on the corner and demanded to know which of them had so affronted his niece. Porfirio allowed that it was he, and the belligerent fellow came rushing at him. But with the footwork he’d learned in Calais, he sidestepped the attack and countered with a solid right hand to the big man’s chin, sending him reeling backward to trip over a curbstone.

As García gathered himself and wandered off, dazed and ashamed, Porfirio accepted his friends’ acclaim with sarcastic pomp. (“I preened,” he recalled.) But a minute or so later, García was back, this time wielding a knife and demanding satisfaction. Porfirio agreed to a duel, and the two set off down El Conde in search of a blade of equal size and weight. Failing that, García suggested they find a pair of matching pistols; again, the younger man agreed. As they walked along, García made small talk, and asked Porfirio who he was.

“I am the son of General Rubirosa.”

The bully stopped walking. “In that case,” he declared, “I cannot fight you. I served under your father.”

The episode became a local legend, spun in some versions with elaborate detail. But there was a bitter private irony to it: Don Pedro’s name might still have been big enough to ward off an angry man with a knife, but his body was failing. In 1930, just before the national elections, he moved to San Francisco de Macorís, ostensibly to run as a congressional deputy for the district but quite obviously to die in the tranquility of his birthplace.

He moved into the house of his father-in-law, a strange old bird who’d been an important local lawyer until he was accused, in 1895, of having embezzled public funds; he was proven innocent, but he was so offended that his fellow townspeople should doubt him that he became a hermit, isolating himself in his house. “He never left his study or library and he refused to see anyone besides his family and clients,” remembered Porfirio. “He never again put a foot in the street, and the only journey he made out of the house was in the hearse that carried him to the cemetery.” Don Pedro wasn’t quite so eccentric, but he was just as surely retreating from the world.

The gravity of his father’s condition impressed Porfirio, who left Santo Domingo for Don Pedro’s side and applied himself sufficiently to his studies to pass his baccalaureate and find work teaching French in a local school. He kept up his soccer, he took up competitive swimming, he traded lessons on the ukulele for guitar lessons from his cousin Evita.

And he sat patiently as Don Pedro, his voice weakened, told stories of his warrior days and shared his worries over the seemingly permanent chaos of Dominican governance. Indeed, even as Santo Domingo prepared for what was being billed as a free election, a rebellion against the government was brewing in—where else?—the Cibao.

Don Pedro knew the minds of both the government and the rebels. He had been offered positions of responsibility by both, refusing in each case because he saw the country’s salvation in neither. In particular, he had strong fears about the leader of the National Police, a cunning and unlikely arriviste who had diabolically made Don Pedro the offer of ruling the country after a coup. As he sat with his son reading a newspaper account of the brewing rebellion, Don Pedro pointed a feeble finger at a name in a headline and said, as his son recalled, “Here is the heart of the plot. The one in charge, in the shadows, pulling the strings, who has all the trump cards, is Trujillo.”

In England and America, they came to be known as lounge lizards.

THREE (#ulink_aae97629-ddc9-59f1-a08a-2db5e2e8e968)

THE BENEFACTOR AND THE CHILD BRIDE (#ulink_aae97629-ddc9-59f1-a08a-2db5e2e8e968)

His uniforms were always immaculate, as were, when he could finally afford them, his hundreds of suits.

His manner careered unpredictably from obsequious to civil to icy.

His appetites for drink, dance, pomp, and sex were colossal.

His capacity for focused work seemed infinite.

He was a finicky eater.

With his thin little mustache, he looked a cross of Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux and a bullfrog, always with his hair slicked back, always standing erect to the fullness of his five feet seven inches, always tending slightly toward plumpness (as a boy, he was mocked as Chapito: “little fatty”).

He had a massive ego that sat perilously on a foundation of dubious self-confidence.

He remembered everything and forgave nothing, though he might wait years to avenge a grudge.

He wasn’t above physically torturing his enemies and throwing their corpses to the sharks, but he had at his disposal more insidious schemes that involved anonymous gossip, public shunning, and other shames that cut deeper, perhaps, than any punishment his goons might mete out.

His scheming and brutality and cunning and shamelessness and greed and nepotism and cruelty and gall and paranoia and righteousness and delusions of grandeur verged on the superhuman.

He was one of the most ruthless and reprehensible caudillos, or strongmen, ever to hold sway in the Western Hemisphere—and one of the most enduring.

He was Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, and he formed an unholy bond with Porfirio Rubirosa that would crucially shape the latter’s life.

Trujillo was born in October 1891, the third of eleven children of a poor family from San Cristóbal, a provincial capital in the dusty south of the island. The town began as a gold rush camp, then settled into a long, hard haul as one of the island’s many centers for processing sugarcane. It was never an illustrious spot, but for several decades of the twentieth century, it was known by federal decree as the Meritorious City, simply because it was the birthplace of this one man.

By his sixteenth birthday, with only a grammar school education, Trujillo was working full-time as a telegraph operator—and perhaps doing a little cattle rustling on the side, though records of his activities in that sphere would one day disappear. (Likewise, he was convicted of forgery and at another time suspected of embezzlement, but in neither case could it be shown on paper after he’d established his domain over the nation and its historical records.)

By his twenty-second birthday Trujillo was married to a country girl named Aminta Ledesma who was pregnant with a baby daughter who would die at age one and, like her father’s criminal record, be erased from later accounts of his life. A second daughter, with a grander future, came the following year. They named her Flor de Oro—“golden flower” in English, “Anacaona” (the name of a warrior chieftainess of the Jaragua tribe) in the native Taino.

Trujillo first engaged with the hair-raising brand of Dominican politics in the mid-1910s, when he joined an unsuccessful rebellion against one of the nation’s fleeting governments and had to live on the run in the jungle until finally, ragged and starving and underfed and missing a few teeth, he threw himself on the mercy of the authorities. Granted amnesty, he came back home and turned to crime, as a member of a gang called the Forty-four. And then he found honest work in a sugar refinery, first as a clerk and then, providentially, as a security guard.

It was no rent-a-cop position. In the lawless Dominican Republic of the era, the policía of a thriving private business constituted, in many cases, the only local authority of any standing. These forces were charged with keeping the peace and guarding their bosses’ property from theft, but they also fought fires in the cane fields, protected payrolls, made sure workers didn’t defect to rival operations, and mounted and supervised such profitable side businesses as bars, brothels, and weekly cockfights.

It was a position that called for a calculating mind composed of equal parts soldier, accountant, psychologist, and mafioso. Trujillo was perfect for it.

He liked the work so well, in fact, that he decided to become a career soldier, applying at the end of 1918 to join the National Police, the only military force open to a Dominican during the American occupation. His letter requesting induction was a combination of bootlicking, braggadocio, and bald-faced lies: “I wish to state that I do not possess the vices of drinking or smoking, and that I have not been convicted in any court or been involved in minor misdemeanors.”

He was accepted, enrolling as a second lieutenant in January 1919. Within three years, he had attended an officers training school and been promoted to captain. The Yankees liked him: “I consider this officer one of the best in the service,” wrote one evaluating officer. And he continued to advance, sometimes in shadowy fashion. In 1924, the major under whom he served was killed by a jealous husband; most onlookers assumed that the offended party was put onto the scent of his wife’s affair by Trujillo, who eventually replaced the dead man in rank and duties. By the end of that year, with the North American marines having returned home, Major Trujillo was third in the chain of command of a military force that was virtually unopposed in ruling the land.

All that remained now was to take over.

But before he could ascend to full power, there was a domestic matter to resolve: namely, the peasant girl he had married, hardly a fitting wife for a man of his status. Sexually, Aminta had long since been replaced by a string of women, one of whom, Bienvenida Ricart, Trujillo had singled out as a likely next wife. Divorce by mutual consent was, curiously, legal in the almost homogeneously Catholic Dominican Republic at the time, and in September 1925 the Trujillos’ marriage was dissolved by civil decree. Trujillo was ordered to pay alimony, to provide Aminta with a house, and, to his frustration, to leave Flor de Oro to live with her mother—a detail he would revisit.

A full two years later, serving at the rank of brigadier general, he married Bienvenida. But by then yet another concubine had taken a special place in his heart: María Martínez, who in 1929 would trump her rivals by producing a male heir, Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Martínez, a boy stamped for life with the nickname Ramfis, derived from his father’s love of Verdi’s dynastic opera Aida. Through the coming years, just as he navigated with Machiavellian deliberation the political waters of the nation, so would Trujillo manipulate these women, regularly discarding a lower-class mate for a higher as a means of fashioning his image and his fate: a proper tíguere.

He proved as decisive and ruthless in public life as in private. In the next two years, he moved gradually, in the shadows, to solidify a power base from which he might seize control of the country. In 1928, the National Police was transformed by law into a proper National Army, and Trujillo was named its chief. But he had additional resources at his disposal—thuggish gangs that enforced his wishes and maintained a cordon sanitaire of plausible deniability between his official position and the more brutal imposition of his will.

He patiently bided the ineffective presidency of Horacio Vásquez, the military man whose ascent back in 1924 had convinced the North American occupiers that the country could see to itself. As Vásquez’s health failed and his government weakened toward collapse, various groups jockeyed to replace him. Each knew that it would need Trujillo on its side. None, however, fathomed the deep logic of the situation as well as he or recognized that he had fancied himself the best man to rule the country.

Presidential elections were announced for 1930, and it wasn’t clear that Vásquez was out of the running; many notables—including, at times, Trujillo, at least publicly—declared an interest in his reelection. But at the same time, Trujillo hatched an audacious, sinister plan to usurp the presidency. In broad outline, he would confide in an ally in each opposition party his intention to support its cause by staging a rebellion of disloyal troops in—where else?—the Cibao; when Vásquez sent him to quell the rebellion, for he could turn to no one else, Trujillo would instead take command of it, leading it into the capital and overseeing a rigged election that would put his candidate—whoever that might be—in power.

What Trujillo told almost no one was that he was his own preferred candidate, that he was going to pull his support from whichever side came closest to power when it would be too late to stop him, seizing the top spot for himself. He shared his plans with the American diplomats who monitored Dominican politics from a judicious remove while wielding the threat of a second occupation as a means of influencing the nation’s affairs (the Yanks were still impressed with him, if less than enthusiastic about his plan). He also shared his plans with Don Pedro Rubirosa, who declined to take part.

The scheme was so risky that Trujillo hedged against failure by keeping a small fortune in cash at the ready should it fail and he be forced to flee. As it turned out, it went almost exactly as he’d planned. He found credulous dupes in each political camp and played them sublimely: Each man, in his own ambition to usurp the presidency, was certain he had the army’s support. He fomented just the right amount of faux unrest in the Cibao; when Vásquez felt himself nervously in need of a stronger military of his own, Trujillo was promoted to minister of national defense. A little more than a week later, as the phony revolt approached the capital, Vásquez, masterfully gulled, demanded assurances of loyalty from Trujillo and, mollified, directed him to stave off the impending coup. Trujillo sent a token platoon to oppose the insurrection—with orders, of course, to join rather than stop it—and then holed himself up with a more sizable and better-armed force in the chief redoubt of Santo Domingo, the Ozama Fortress. And there he sat implacably, insisting on his loyalty to Vásquez while the besieged president was forced to resign without a shot being fired in his defense.

Trujillo allowed his coconspirators in the opposition briefly to enjoy a show of control over the nation. And he equanimously allowed the presidential election to be held, with Vásquez’s party still permitted to run a candidate. But the whole thing was a dark farce. Everyone who might have taken power had been suborned by Trujillo into treason; no one could risk exposing his own deceit by stepping forward to claim the reins. Trujillo used frank acts of intimidation and violence to curb any dissent to his own puppet candidate, Rafael Estrella Ureña, and then simply strong-armed the man out of the race. The sham election was protested even before it occurred: An oversight board resigned en masse a week before the balloting. In May 1930, Trujillo was elected president by a near unanimous (and patently fabricated) majority that would have made the most megalomaniacal despot envious; in August, amid the high pomp he had felt was due him even in his days as a telegraph operator, he was inaugurated.

With epic tenacity and iron severity, Trujillo would so impose his personality on the Dominican Republic and its people that there would be no appreciable distinction between the man and the nation. Stalin, Mao, Castro, Amin, Ceausescu, Hussein, Kim Il Sung: none would have the same degree or depth of impact on the psyche of his people. In the course of time, every home in the country would boast a sign reading “God and Trujillo”—often right out on the roof in huge letters. Santo Domingo would be renamed Ciudad Trujillo; calendars would all be dated according to the Era of Trujillo, with 1930 as Year One; Pico Duarte, at ten thousand feet the highest peak in the Caribbean, would be renamed Little Trujillo—as opposed, of course, to the big one who sat, literally, on the throne in the National Palace; the first toast at any formal dinner, especially those at which he was not in attendance, would be to the health and honor of Trujillo; and he would be spoken of not as the President or the Generalísimo or the leader but, unironically, as the Benefactor.

These ritualistic incarnations of the cult of personality didn’t emerge immediately after Trujillo took power. No, before the tíguere Trujillo could metamorphose from soldier to god, certain parties reluctant to being held in his domain would have to be made to knuckle under. In particular, there was the refined circle of bourgeois families who dominated the social and cultural life of the capital. Educated, traveled, wealthy, born to relative privilege, they looked frankly down their noses at Trujillo with his mean roots, antiquated manners, and precise mien. In 1928, still merely an ambitious officer, Trujillo had stood for election to the Club Unión, one of Santo Domingo’s most elite social institutions, and was admitted because, as everybody who observed the process knew, somebody acting under his orders had tampered with the vote. That he nevertheless went ahead and joined and attended the club was the most desperate sort of social climbing; Trujillo felt the sting of having been forced to embarrass himself and filed it away for future vindication. His revenge was swift: In 1932, after filling the club with military officers, he was elected as its president, transferred the entire membership wholesale to a newly formed premises, and had the genteel old home of the Club Unión razed.

But Trujillo characteristically had another, more cunning scheme for gaining influence over the Dominican elite. If he couldn’t enlist the parents, he would enlist the children. And he found a perfect candidate with whom to begin his campaign: the feckless, French-educated, popular son of the estimable and recently deceased Don Pedro Maria Rubirosa.

In the autumn of 1931, Porfirio was out at a drinking party with friends at the Country Club, another of Santo Domingo’s swank gathering places, when he noticed Trujillo, in full, glistening uniform, presiding over a party of military officers across the room. It was an inauspicious time for the young man: Upon his death a year earlier, Don Pedro had left his son little more than the thin veil of a good reputation—for which, truly, Porfirio had no practical use—and a deathbed wish that he continue his legal education. With the household now dominated by his brother-in-law Gilberto Sánchez Lustrino, a dreary future seemed probable. Obviously the opportunity to return to Paris was negligible, and the seemingly unavoidable legal studies would clearly tear him from the sporting, leisurely life of the streets of Santo Domingo.

Sánchez Lustrino was a true Dominican bourgeois, more dedicated to shows of courtliness and refinement than Don Pedro had ever been, a born-and-bred member of that class of gentlefolk who sneered, sometimes openly, at the pretenses of the rustic new president. And, as Porfirio didn’t care much for his brother-in-law, he was particularly pleased when an aide of Trujillo’s came to the table that night at the Country Club and told Porfirio that the president wanted to see him.

As he approached the group of soldiers who, in contrast to his boisterous friends, sipped their drinks in tightly wound decorum, Porfirio observed that “one man dominated with his energetic mien, his dark and severe gaze, a certain hidden brutality and his impeccable uniform: Trujillo.” But when he was introduced to this forbidding man, a chameleonic transformation occurred before his eyes. “I was stupefied at the change that came over him,” he later recalled. “His severe expression disappeared, and he seemed very pleased to meet the son of an old friend.”

Porfirio knew that Trujillo had attempted to lure Don Pedro into the byzantine scheme by which he gained control of the country and that his father, partly because of his ill health, partly because he genuinely desired that his nation’s future be decided democratically, demurred. So he wasn’t entirely surprised that Trujillo made mention of his grief at Don Pedro’s passing: “You know, I was very pained by your father’s death. Men like him are what we lack today.”

Likewise, Porfirio wasn’t surprised that Trujillo failed to be impressed by his choice of profession. “Students, always with their noses in books!” he snorted. “If we don’t advance more quickly, it’s because young men like you don’t participate in this great effort.”

But there was a surprise coming: Hard on that admonition, Trujillo gently suggested that Porfirio meet him at the National Palace the next morning to discuss his future, say 10 A.M. The matter agreed, the older man stood and, begging pardon, left the club, but not without a final invitation: “Sit here with your friends. Tonight you are the guests of the President!” Porfirio waved his chums over and they joined the soldiers, who slackened their rigid posture when Trujillo left and drank brandy and champagne with the young men until the early morning hours.

He returned home and prepared for his meeting, his head heavy from the night’s indulgences. At the palace, he found Trujillo characteristically alert, erect, immaculate, and direct.

“Did you enjoy yourself last night?”

“Thanks to you, Mr. President.”

“Very good. Now let’s get to more serious matters. I am going to make you a lieutenant in my Presidential Guard.”

There was no time—or, indeed, reason—for retort. Trujillo immediately sent a lackey to fetch an administrative official, to whom he announced, “I have just named Señor Rubirosa a lieutenant. I want to see him in uniform immediately. Take him to my personal tailor, my shoemaker and my gunsmith. Tonight he’ll enter the military training academy.”

As he was outfitted in the splendor that Trujillo demanded for himself and those closest to him, Porfirio tried to wrap his mind around the situation. “At 22,” he admitted, “this was a windfall … I was sufficiently vain to believe that my personality and the name of my family had occasioned this treatment by the General.” But he managed as well to plumb Trujillo’s deeper motives. Addicted to gossip—especially as a means of dominating its subjects—Trujillo had heard about Don Pedro’s popular boy-about-town and determined to use the young man’s social standing for his own purposes. Porfirio understood it instinctively: “He had resolved to get the golden youth of the island involved in the reform of his army. I seemed a young man well suited for this plan because of the prestige of my father and the esteem that my Parisian education had among young men of my generation.”

At heart, he understood Trujillo because the two were cut of the same material: “The General was a tíguere,” he recollected, “crueler than any of the other tígueres Santo Domingo had known before. This tíguere was smarter than a fox.” In time, their relationship would evolve into a complete symbiosis. Trujillo, capable of the most ruthless acts, would pass virtually all his life in the Dominican Republic to keep his iron fist on its affairs, would commit the most ruthless acts of violence and immorality to suit his pleasure and his power, but would always take especial care to maintain at least a show of public decency. Porfirio, who would eventually emerge as his country’s most visible emissary to the outside world, habitually engaged in a more extroverted and sensational form of tíguerismo, based not on the ruthless wielding of fear but on suavity, dash, ambition, charm, and magnetism. He would provide the sophisticated public face of a brutal regime while Trujillo would, in turn, provide a steely foundation for his stupendous adventures—a mutuality that Trujillo seemed almost to have planned from the start.

It began when, hung over and greedy, Porfirio swallowed the bait dangled before him, allowing yet another of the older man’s schemes to unfold exactly as it had been planned. “Just as Trujillo imagined,” he confessed, “many young men of the Dominican upper classes followed me.”

He didn’t care if he was being used. Military life, contrary to expectations, appealed to him. As he would recall, “Physical efforts filled our days: calisthenics, various sports, arms training, target practice, horseback riding. For a young man like me, it was paradise.” It was made for him: the smart, elaborate uniforms, the camaraderie of fellow junior officers, the freedom from the responsibility to feed or house himself or define his days.

He loved his uniforms, and he looked brilliant in them: pinch-waisted, sharp-jawed, muscular, whippy, with a tight crown of wavy hair, a broad forehead, dark almond-shaped eyes, wide cheekbones, and that café au lait complexion. He wore his hair longer than other soldiers and his boots were more suited to gentlemanly pursuits than to combat or training. If the elite society of Santo Domingo wasn’t yet prepared to accept Trujillo and his military, there were certainly young ladies whose eyes, and more, would readily be caught by the spectacle of this handsome, cultured young officer. He was in his glory.

His golden impression of his new life wasn’t shared at home. His brother-in-law asserted his domain over the household by refusing to allow a soldier to live under his roof. Porfirio simply moved into the barracks.

As a young soldier, he didn’t necessarily comport himself according to the strict standards of self-control that were so important to Trujillo. Having been promoted to first lieutenant and named a member of Trujillo’s personal staff, Porfirio was required to attend all of the deadly dull affairs of protocol of which the president was so enamored. Among these was a formal ball that would be attended by all of the civilian elite of Santo Domingo, a company by whom Porfirio was loathe to be seen in the role of aide-de-camp, a mere lackey. Ordered to attend in dress whites, he showed up instead in khakis, declaring that he hadn’t been told about the day’s dress code until it was too late and that his formal uniform was in the laundry. (“I still recall the look Trujillo gave me,” he would say more than thirty years later.)

With the other junior officers, Porfirio was ordered to stay put behind Trujillo, but he boldly strode over to where a young woman he knew was seated, and he took a chair beside her to chat. A nervous senior officer approached.

“Are you Lieutenant Rubirosa?”

“Yes.”

“The President has sent me to tell you that you may dance if you wish.”

The rest of Trujillo’s military corps gaped in astonishment as Porfirio enjoyed champagne and the company of the ladies for the rest of the evening. They had reckoned he’d be lambasted; instead, he had the time of his life.

That close call with the president’s anger wasn’t quite enough to scare Porfirio into the straight and narrow that was becoming the norm for trujillistos, as the most ardent followers of the president were known. In May 1932, he injured his knee in a one-car accident in San Pedro de Macorís, thirty miles east of Santo Domingo: As if he didn’t care how he’d comported himself he’d been speeding. “The distinguished young military gentleman,” as a fawning newspaper account referred to him, was attended in a local hospital and then transported by ambulance to the capital where he was seen by top military doctors. “The injury doesn’t apparently require additional care,” the report continued. “We are happy to wish him the quickest and most complete recovery.”

His first smash-up!

In July, Trujillo told Porfirio that his presence would be required the following day at the harbor, where a full complement of officers and a military band would greet the arrival of a ship that was returning the president’s daughter, Flor de Oro, from two years of school in France. Trujillo had special need for his audacious, French-speaking aide-de-camp at this particular reunion. “She knows Paris like you do,” he explained. And then, after a pause, he added, “Well, really, not like you do, I would hope.…”

The seventeen-year-old girl who got off that boat was, as she would later remember, “bedazzled” by her reception. “ ‘El Supremo,’” as she referred to her father, “stood there in an immaculate, starched white-linen suit, flanked by shining limousines and his handpicked aides. I noticed one lieutenant instantly—handsome in a Dominican uniform that had a special flair. Even the gold buttons looked real.”

It was, of course, Porfirio. And he, of course, noticed her noticing. “She was enchanting, with dreamy eyes and hair as black as night,” he later recollected in the florid style that overcame him when he wrote of romance.

No words were exchanged between the French-educated youngsters as Trujillo whisked away the daughter with whom he’d had virtually no contact since infancy. For Flor, riding with her father was quite nearly like making a new acquaintance. From the time the North Americans came to occupy the country, Trujillo had left his first wife and their daughter behind. “We knew little of what he did,” Flor remembered. “Three or four times a year, he’d come home, each time more and more overbearing. My proud job was to wash his military belt in the river for 25 US cents.”

Aside from such childish domestic chores, the girl served another purpose for her father: Trujillo spent Flor’s childhood offering different military or political bigwigs the chance to serve as his daughter’s godfather, a singular honor in a Latin family. But he never made the designation official, continually jockeying for a better and more prestigious candidate until the girl was almost fifteen years old and had either to be baptized or to be refused admittance to the French boarding school her father had chosen for her. (To get a sense of Trujillo’s relatively low standing at the time, the lucky winner of this sweepstakes was the family doctor; Flor, for her part, suffered the mortification of being the only baptismal candidate at that particular mass who walked on her own power to the altar rather than be carried as a babe in arms.)