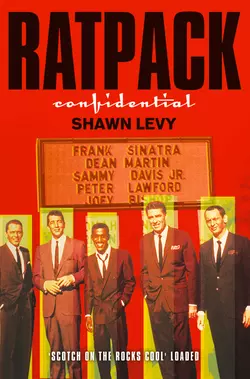

Rat Pack Confidential

Shawn Levy

The first biography of the Rat Pack – Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, Joey Bishop et al – the original Swingers. Brilliant and beautifully written story of their rise and fall, and their connections with the Kennedys and the Mafia.This edition does not include illustrations.They alit in Las Vegas for a month to make a movie and play a historic nightclub gig they called the Summit; they hit Miami, the Utah desert, Palm Springs, Chicago, Atlantic City, Beverly Hills, Hollywood back lots, illegal gambling dens, saloons, yachts, private jets, the White House itself.It was sauce and vinegar and eau de cologne and sour mash whiskey and gin and smoke and perfume and silk and neon and skinny lapels and tail fins and rockets to the sky.It was swinging and sighing and being a sharpie, it was cutting a figure and digging a scene.It was Frank and Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin and Peter Lawford for a while and Joey Bishop when they asked him and Jack Kennedy and Sam Giancana and tables full of cronies and who knew how many broads.It was the ultimate spasm of traditional showbiz – both the last and the most of its kind.It was the Rat Pack.It was beautiful.‘Rat Pack Confidential’ – you’re never far from a cocktail, a swingin’ affair and a fist-fight.

RAT PACK CONFIDENTIAL

SHAWN LEVY

Frank, Dean, Sammy, Peter, Joey & the Last Great Showbiz Party

Dedication (#ubd29f348-a4c5-51a4-8764-9add2b725625)

For my mom, Mickie Levy, who arranged for me to see Frank at the 500 Club when I was still in Utero …

Contents

Cover (#uca872c62-4cb1-5292-82a5-a3912e156da3)

Title Page (#uf6896483-6037-5392-afd9-cac509b9b6d6)

Dedication (#u6acac2b5-80c0-57fc-b245-5b54cc87a2b2)

Part 1 (#u7fbbf169-4cfa-5f9d-a59d-2235c150ad06)

Part 2 (#u6ed12386-4f9a-5522-b114-06ef742407c3)

Slacksey o’brien (#u04aad45f-0f04-512e-8cac-d52ad87b02e7)

105 percent (#u07e0658f-d078-5b59-aacb-809a6fe74da5)

Sonny boy (#u151a768b-4190-5a89-b95e-bbd6682ef3a0)

America’s quest (#u1a21013c-f3c0-532a-800a-4c84761630ae)

I was told to come here (#u0bf245a9-19a7-5e07-a95b-ee78fdf22cc0)

I‘m not going to stooge for anyone (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Much, much, much (#litres_trial_promo)

Some things you don’t want to know (#litres_trial_promo)

The only singer (#litres_trial_promo)

Worthless bums and whores (#litres_trial_promo)

The place was on fire (#litres_trial_promo)

Almost the end of frankie-boy (#litres_trial_promo)

The most exciting assignment of my life (#litres_trial_promo)

What they were really being paid for (#litres_trial_promo)

What we do is a rib (#litres_trial_promo)

I feel dirty (#litres_trial_promo)

I’m a whore for my music (#litres_trial_promo)

The Frank situation (#litres_trial_promo)

One of these days it’ll come out (#litres_trial_promo)

You and I will always be friends (#litres_trial_promo)

It always ended up as a threat (#litres_trial_promo)

He’s needed this for years (#litres_trial_promo)

Say goodbye (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

I’ve got five good years left (#litres_trial_promo)

I don’t know what hit me (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Scuse me while I disappear (#litres_trial_promo)

I wanna go home (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Not a moment too soon (#litres_trial_promo)

Adult male human behavior (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 1 (#ulink_686277cd-529e-5c56-ab43-8ae4154535ca)

This was Frank’s baby.

Onstage, Dean, singing almost straight, then pissing away anything like real feeling with jokes.

In the wings, Sammy, Peter, Joey.

Out front, a mob scene: Marilyn, Little Caesar, Kirk, Shirl, Mr. Benny, that Swedish kid that Sammy was so crazy for, that senator and his tubby kid brother, a few broads without addresses, a few guys without real names …

Famous faces at ringside for the cameras, infamous ones in the shadows in the back, plus a hundred or so civilians as bait for the rest of the world—suckers with money to blow and dames to blow it with them until it ran out.

In the casino, every schmuck that couldn’t pay or beg or muscle his way in was betting his rent money just to feel as big as the ones who could.

The joint was packed; the rest of town might as well have been dark.

And for what?

A movie, a party, a floating crap game, a day’s work, a hustle, a joke: They’d make millions and all they had to do was show up, have a good time, pretend to give a damn, and, almost as an afterthought, sing.

Sometimes it seemed like Dean had the right idea: “You wanna hear the whole song, buy the record …”

But there was something in the music, wasn’t there? With the right band and the right number, it was like flying—and like you could drag everybody up there with you.

So let Dean do jokes, and Sammy—Sammy would start numbers and they’d stomp all over them and he’d like it.

But when Frank sang, it would be straight. It could be New Year’s Eve, the very stroke of midnight, the middle of Times Square, and he would stop time, stop their hearts beating, and remind them where the power was.

It was in his voice.

It was his.

When they finally had enough and dropped the curtain, they would wander out into the casino.

Some act’d be up there on the little stage in the lounge, and maybe they’d go over and screw around; Sammy liked that the best—more eyes on him, always more eyes.

What Dean and Frank liked was dealing. They had points in the joint, and who was gonna stop them from horsing around at a table: It was their money, right?

Dean actually knew what he was doing. He’d push aside a blackjack dealer and do a little fancy shuffling and start dealing around the layout: his rules.

“You got five? You hold. That’s a winner.

“Nineteen? Hit. Twenty-six? Another winner.”

He’d shovel out chips and make sure that everyone took care of the real dealer, who’d stand there looking nervous over at big Carl Cohen, the casino manager, who normally didn’t go for clowning.

But Carl would be quiet. He’d lose a couple hundred during this monkey show, sure, but he’d get it all back and more: There were crowds five or ten deep just waiting to get at the tables. Besides, Dean was like family; he’d worked sneak joints back in Ohio before the war with Carl’s kid brother. The big guy could afford to be a little bit indulgent.

Which wasn’t the case with Lewis Milestone, the poor director saddled with making a movie in the middle of it. Every morning he came to work in an amusement park that his boss owned and woke his boss up and tried to get him to jump through hoops for a few hours, and you had to look deep into his dark old eyes to see what he really thought about it.

This movie wasn’t some work of art, this wasn’t All Quiet on the Western Front with poetic butterflies and mud and a moral. This was a sure thing, a money machine, a way to bring the party to the people who could only read about it in the papers. Hell, the only reason they hired him in the first place was that Jack Warner insisted on a pro and Peter guaranteed that the old guy—who was making Lassie shows, for chrissakes—would do whatever they told him.

But, still, they didn’t want to make a career out of it. So come the morning, they let Millie run them around in circles for a little bit, even if they hadn’t gone to sleep yet on account of last night was, as they liked to say, a gasser.

Or at least everyone but Frank let him do it. Frank was the boss, after all, and picture or no picture, he was going to work when he felt like it. He used to say that he only had one take in him, like he was an artist about it. The truth was he only had one take he gave a shit about, and if they wanted that one in the movie, then they’d have to wait until he was ready to give it.

So Sammy, a Salty Dog or two down the hatch, would show up on the set at 9:00 or 10:00 in the morning, and Dean and Peter would show up at 9:00 or 10:00 in the morning, and Joey—who was lucky to be here at all, let’s face it—would be there at 7:00 or whenever they said so, showered and alert.

But Frank: 4:30 in the afternoon, maybe 5:00; and twice, twice, before lunch; and most days not at all.

They worked on the picture twenty-five days in Vegas; Frank showed up nine.

Oh, it was his show, all right.

In the early evenings, between a few hours of the movie and going back out onstage, the steam room. Frank had it built—the first one on the Strip—and when he was in town it was off limits to anyone else. They’d drink in there and make phone calls and give each other the needle: the only time they could all be together and alone.

Some other people were allowed in: the ultimate VIP room. This Rickles would take these incredible liberties with Frank and Frank would kill himself. Sammy would take one humiliation after another—“You can’t wear a white towel. Here’s a brown towel for you!”—and act like he was killing himself. Actors from the movie. Business guys. Other guys who didn’t say who they were. This was an inner inner circle. Men capable of all sorts of acts of power would sit like convent girls just for the pleasure of having been allowed inside. Compared to this, the show and the movie were, well, for anyone.

But not just anyone was welcome. This was a group that Frank handpicked, gliding through the world, sizing people up, then giving them the golden tap on the shoulder and bringing them in.

Talent, money, power: None of these was quite enough. You had to have something Frank had, or something that he wanted to have more of. You were a cool, leonine Italian, or a dazzling black ball of fire, or a British sophisticate with powerful relatives, or a Jewish wiseguy who could brush off the world with a shrug. You were an Irish millionaire senator or a psychotic Mafia lord. You were the acme, the original, one of a kind, and Frank wanted you up close to study. He gathered everyone around him and sat in the middle and saw little parts of himself, little things he could fix or steal—Dr. Frankenstein building a hip new kind of superman.

Frankenstein, though, or Nosferatu? Because, though everyone got rich, got famous, got laid, Frank got more. They made movies; Frank was the producer. They cut records; Frank owned the company. They played Vegas and Tahoe; it was Frank’s hotel. Everyone did good work; Frank was Michelangelo.

They called him the Leader; they asked him to be their best man; they named their kids after him, their daughters, even. And when it all spun out of control, when the precious, delicate balance came undone, when the merry-go-round stopped with a jerk, everyone got thrown on their ass—or worse—except Frank, who stood there in the middle, unfazed.

Divorce, drugs, bankruptcy, death, irrelevancy: Every single one of them took a major hit.

Frank didn’t get so much as a scratch.

But that would all be later. That would be after the golden time, when, for a while, no matter what they did, it would sell. No matter how many broads, no matter how much booze, no matter who they got mad at or cozied up to, it had reached a point where Frank could simply do no wrong.

The press knew the story. They didn’t write it, but they knew it. They didn’t rat him out because they needed him more than he needed them, and except for a few he’d chosen as whipping boys, they lined up to do whatever he wanted them to do.

He was drinking with this one or that one or fucking this one or that one—who was gonna talk?

And anyone he wanted around him, the same thing: You hiding from the G? You don’t need to hide around Frank. You got a wife back home who reads the gossip page? Frank’ll see that you’re not in it. You running for president? Frank’ll throw a little juice your way and make sure everything looks on the up-and-up.

Up close, the whole thing was not to be believed. You wanna talk about rebellion? Those rock ’n’ roll punks had no idea what a real rebel did in private. They couldn’t begin to understand the power and the appetites and how little you had to care. La Dolce Vita nothing: This bunch made Nero look like a Cub Scout.

But outside, from far away, it didn’t look like ego or license or indulgence. It looked like a big, beautiful party in the desert, with laughs and music and cars and clothes and incredible women, and no one ever ran out of money, and no one ever got tired, and no one had to answer to anyone, and no one ever grew old, and you would just die unless you could be there—even if the closest you ever got was a movie theater or a record player.

Wherever they went, they drew a crowd. And not just yokels, but Friars and sex symbols and made men and the president himself. They made Vegas Vegas, Miami Miami, and Palm Springs Palm Springs. And they made and broke people like they were pieces of toast.

For a while, everything took a backseat. For a while, the whole world was like a gyroscope, spinning so fast that it looked like it was standing still, with Frank and his cronies smack-dab in the middle of it, smiling at you, making you think you could do anything.

The world wasn’t big enough for them to bother with so they made it bigger and took it over.

And instead of resenting it, people loved it.

And there was never anything like it before or since.

Between 1957, when his hero Humphrey Bogart died, and 1963, when his friend Jack Kennedy died, Frank Sinatra was the biggest star in all of showbiz.

There was Elvis, of course, and John Wayne and Danny Thomas and Ray Charles and Marlon Brando and Bob Hope and Pat Boone and Tony Curtis and Frankie Avalon and Jerry Lewis and a whole lot of other people who were Kings of Pop, or certain quadrants of it, at the time.

But nobody was so sheerly supreme as Frank as an icon, artist, or draw, none held his mighty sway over the mass imagination, and none was so ascendant for so long.

With his stunning LPs for Capitol Records—Songs for Siwingin’ Lovers, In the Wee Small Hours, Come Fly with Me, Only the Lonely, a good dozen more—he was releasing classics at the rate of several a year and moving big numbers in the record stores.

With a string of commercial hit movies—and good ones, frequently, like The Man with the Golden Arm, The Joker is Wild, High Society, and the Oscar-winning From Here to Eternity—he ranked among the era’s top-grossing movie stars.

He had regular specials on television (though rarely very good, they always drew well); he was the top act in nightclubs from Miami to Chicago to Las Vegas; he performed with ceremonious duty at charity events, Academy Award telecasts—all the orthodox showbiz sacraments.

Arguably no single entertainer had ever held the top spot in so many media for so long—Bing Crosby, maybe, back in radio days.

No, Frank was It.

And It in ways that nobody ever had been.

Because as big a deal to the popular American mind as Frank’s considerable musical and cinematic lives was his private life.

Flitting from gorgeous bedmate to gorgeous bedmate, rubbing elbows with tough guys, throwing punches, pounding back whiskey, romancing in a cigarette’s glow, he was the envy of every American male who had left off worshiping Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams for more grown-up pursuits: the rakish kid brother-in-law they’d all secretly give their left arms to trade places with.

There was nothing, it seemed to the average working stiff, that Frank didn’t have.

But Frankie—and who could have guessed it?—didn’t like to be by himself: He got antsy. He liked to have entourages of like-minded he-men around him, guys to drink and schmooze and play cards and go to the fights and hit the bars with: chums.

He wanted an accumulation of bosom fellows around him, and he thought it would be wonderful if they could work together. He began to play with his buddies in nightclubs, to make films with them, to pop in on their TV shows and invite them onto his.

He started smallish—a picture with one or two here, a spontaneous walk-on there—but then his horizons expanded. Various threads in his personal and professional lives began to merge in ways that no one would ever have predicted: his affectations toward politics and the Mafia, for instance, his ownership of film and record companies and shares in casinos, his friends and debtors and vassals.

At the end of 1959, he concocted an intoxicating brew of money, power, talent, romance, gall, a nexus of showbiz and muscle, politics and glamour, a brilliant netherworld spinning at 33⅓ with himself stock-still at the center, conducting it all with his mind.

They alit in Las Vegas for a month to make a movie and play a historic nightclub gig that they called the Summit; they hit Miami, the Utah desert, Palm Springs, Chicago, Atlantic City, Beverly Hills, Hollywood back lots, illegal gambling dens, saloons, yachts, private jets, the White House itself.

It was what a good portion of America was about for a few remarkable years.

It was sauce and vinegar and eau de cologne and sour mash whiskey and gin and smoke and perfume and silk and neon and skinny lapels and tail fins and rockets to the sky.

It was swinging and sighing and being a sharpie, it was cutting a figure and digging a scene.

It was Frank and Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin and Peter Lawford for a while and Joey Bishop when they asked him and Jack Kennedy and Sam Giancana and tables full of cronies and who knew how many broads.

It was the ultimate spasm of traditional showbiz—both the last and the most of its kind.

It was the high point of their lives and a midlife crisis.

It was the acme of the American Century and a venal, rancid, ugly sham.

It was the Rat Pack.

It was beautiful.

Part 2 (#ulink_d894c825-d124-59b5-a711-ed8acfe1b654)

Slacksey o’brien (#ulink_cc3908a7-9993-511e-96c6-4dcd910f8d60)

Grow up with immigrant parents and a last name that no one can pronounce right, with an ear mangled by a midwife’s forceps and no meat on your slight bones, with no brothers or sisters, and a mother always on the go, and a queer little dream that you can win the whole world over with a song; grow up with all this, and then win wealth and fame and acclaim and power—the whole world and more—and you’ll likely find no embarrassment in living as if your every action was the stuff of legend.

Throughout his life, Frank would be boosted in his perception that his progress through the world was of great import, and if he ever lapsed into doubt, there would always be someone around to reassure him: a wife, a dame, a publicist, a thumbbreaker, a daughter, a fan, even, though not quite so reliably, the press. Frank could count on being spiffed-up, spoiled, spirited out of jams; he expected it of life. And it was an expectation born not in the flush of his success but in the earliest days of his youth: Of all the hangers-on, sycophants, yes-men, and boosters, his mother was first and foremost.

There was undeniable steel in Natalie Garavante, the little pug-faced Genoese firebrand known to everyone in Guinea Town, Hoboken, as Dolly. She prodded the men around her to let her through doors that she herself would’ve battered down in a world that cut women an even break. She had a stunningly foul mouth: “Her favorite expression was ‘son of a bitch bastard,’” recalled a mayor of Hoboken who knew her in his youth; a mob lawyer who met her in the 1960s compared her way with profanity favorably to Jimmy Hoffa’s. She made the slow-moving Italian men around her jump at her command, and she carried enough clout to get political bosses and city officials to do the same. She was a shit-stirrer and a hollerer; she worked hard and she took no prisoners; she spoke simpatico with the people in the streets and defied the men of power. If she’d’ve been born a boy, she might’ve been an Italo-American Huey Long.

But she was a woman and it was the 1910s—and an Italian neighborhood at that—and so she had to find a husband, and she settled on a handsome, illiterate kid from the neighborhood, a guy who couldn’t hold a steady job but cut a dashing figure in the boxing ring. Dolly’s brothers were boxers, which was probably how she came to meet Marty O’Brien, a stout, quiet little guy with tattoos on his arms. Maybe she first took him for Irish, which would’ve appealed to her social-climbing instincts; soon enough, she learned he wasn’t an O’Brien but a Sinatra, but that didn’t make him any less attractive. He might’ve been an unfinished project, but Dolly was sure she could make something of him. Despite her parents’ fears of a layabout Sicilian for a son-in-law, they eloped and married in a civil ceremony. A year and a half later, she bore their first and only child.

Later on, he would try to depict himself as some kind of Dead End Kid turned good, but the truth was that Frank was always plushly seen to. In a neighborhood where the men worked menial jobs and the women raised broods of five, eight, ten brats, only-child Frank had two working parents and a surfeit of candy, toys, bikes, clothes. The homes in which he grew up were the finest to which Italians in Hoboken could aspire. A lot of the Sinatras’ neighbors on the tony streets on which they lived didn’t even know they were Italian: Marty ran a popular speakeasy under his boxing name, and Dolly routinely introduced herself as Mrs. O’Brien; when Frank’s buddies wanted to tease him about his Little Lord Fauntleroy wardrobe—he had his own charge account at Geismer’s department store—-they dubbed him Slacksey O’Brien. They were a family on the rise; a local newspaper society page reported on a New Year’s Eve party Dolly threw after they bought a grand home at the height of the Depression.

By then, Frank had revealed himself as a perfect mix of his parents’ temperaments. Hotheaded and ambitious on the one hand, he liked to loaf and schmooze and was an indifferent student on the other. For all that he inherited from his parents, he was, typically, embarrassed by them as well. Marty was no world-beater, everybody knew that, and he seemed pronouncedly meek even among his friends and colleagues; Dolly was outrageous, flamboyant, earthy, loud, an unignorable commotion whose affectations and ambitions grated on as many people as they inspired. Worse yet, she was the neighborhood abortionist, known to all the Italian girls as the person to turn to when they were in trouble; Frank’s ears would turn red whenever he heard people talk about his mother the “rabbit catcher.” Like everyone else, he was attracted to Dolly’s exuberance, but like Marty and the other men in the family, he feared her. “She was a pisser,” he’d say later, “but she scared the shit outta me. Never knew what she’d hate that I’d do.”

As if to erase the shame Dolly put him through—the dudish threads, the mortifying secret work, the rowdy spectacle she made of herself on nights out with the girls—Frank seemed, at first, to take after Marty. He dropped out of school; he couldn’t keep even a menial job; and he took up a fancy even less promising than Marty’s boxing: Smitten with Bing Crosby, he wanted to be a singer.

At the sight of her boy sporting a yachting cap and crooning in a mirror, Dolly was, as her parents had been by Marty, disgusted, but the idea of denying her boy something that he wanted was worse. She bought him a spiffy electric P.A. system and convinced acquaintances to let him sing in their saloons and restaurants; eventually, she used her clout to get him a job chauffeuring a rising local trio, the Three Flashes, who were preparing to make a few movie shorts for Major Bowes, the era’s great promoter of amateur showbiz talent; with his mom’s backing, Frank quickly rose from driver to jester to full-fledged singer in the group.

The older guys in the act, which Bowes redubbed the Hoboken Four, didn’t care much for the mama’s boy in the midst, even less so when Frank’s singing improved and his solos became a centerpiece of the show. During a several-month nationwide tour as part of one of Bowes’s traveling road shows, they began picking on the skinny kid, beating him up when they felt he needed to be taken down a peg. Frank quit and returned to Hoboken—where Dolly had salted the press with news of his successes.

Three years of scattered, aimless work followed, then a steady job—singing waiter at the Rustic Cabin in Englewood Cliffs, a roadhouse which had a broadcast wire to New York’s powerful WNEW radio station. In June 1939, bandleader Harry James heard Frank on the radio and drove out to see whose voice that was. Shazam: Frank was in. James signed him, they hit the road and cut some records, and Frank got a little bit of notice. In December, Tommy Dorsey auditioned him and he left James with a handclasp and best wishes.

This wasn’t just the call of Lady Luck or the reward of sheer ambition. Somewhere sometime in there, a miracle bloomed. Frank’s voice went from pleasant to stunning: a beautiful, tender instrument possessed of uncanny rhythmic sense and breath control, one of the great talents of the century, a gift no more explicable than those of Joyce and Picasso, recognizable as such even in its juvenile state. Everyone who heard him for the first time was staggered.

As a member of the Dorsey orchestra, Frank became famous: hit records, magazine covers, appearances in movies, flattering press. Like he’d learned from Dolly, he milked it, aggressively courting the press, disc jockeys, anyone he thought could boost his career. He spent more than he earned on his wardrobe alone (he was so finicky about his personal cleanliness that his bandmates with Dorsey nicknamed him Lady Macbeth). Within three years, he was convinced that Dorsey was holding him back from a career that would rival Crosby’s, and he left—after months of bitter, petty infighting, a lucrative settlement, and a grudging goodbye.

Suddenly, everything: Frank signed to play the Paramount Theater in Times Square as an “extra added attraction” with the popular Benny Goodman orchestra; when Goodman introduced Frank, the response from the packed theater was so volcanic that he asked his band, “What the fuck was that?” Within a few months, the whole world would know. Spontaneously, Frank had become the beloved of a generation of wild-eyed fans—young girls, mostly—who made him a teen idol decades before anyone ever thought to manufacture such a thing.

Boosted by the devilishly clever press agent George Evans, Frank became bigger than Crosby or Vallee or Caruso—the biggest thing ever in showbiz, in fact. There was a core of critics and musicians among the cognoscenti who admired his artistry (James Agee spoke fondly of his “weird, fleeting resemblances to Lincoln”), but the wellspring was the kids—the bobby-soxers, as they were named for an affectation of footwear. Sinatratics they called themselves, forming cultish cells in devotion to their new god: the Slaves of Sinatra, the Sighing Society of Sinatra Swooners, the Flatbush Girls Who Would Lay Down Their Lives for Frank Sinatra, the Frank Sinatra Fan and Mahjong Club.

These daughters of flappers were quick to connect the longing in Frank’s voice with their own longings, his quavery presence with the absent boys who were off fighting the Hun and the Nip (Frank was 4-F: punctured eardrum). Odd as it may have seemed to everyone in the business, the wiseass runt with the heavenly voice was some kind of sex symbol. (And he’d always be one: For a half-century, Frank was one of the ways America made love, quite often the most popular; he was able to get away with anything because he hit people in their most personal spots.)

By the late fifties, by Rat Pack time, when his audience had grown up, Frank could be as sexy as he felt, but in the first blush of his fame, he had, like all teen idols, to be officially Off Limits. Conveniently, he had a cozy domestic life to play up: He’d been married to a girl-next-door type since 1939; by 1944, they had two kids, one named after each of them: Little Nancy and Frankie Jr.

For George Evans—and for Frank’s many important employers: Columbia Records, CBS radio, MGM, Lucky Strike—this was a perfect setup: a talented, massively popular young guy with a solid family and a wholesome aspect. But Frank seemed hell-bent on screwing it up. There was that entourage—big, unlikely guys, boxing writers, gamblers, songwriters buttering him up—and there were women and there was this habit of snapping back at the press and there was all the politics: Bad enough he was 4-F; did he have to sing “Ol’ Man River” and break bread with Eleanor Roosevelt? Evans spent the better part of the forties covering Frank’s ass, cozying up to some columnists and scratching and clawing at others while his client carried on however he pleased, simply assuming that somebody else would sweep it up.

He rose to insane heights. In 1939, he was waiting tables at the Rustic Cabin for $15 a week; by the end of the war, he was a bigger star in more media than anyone in the world and had grossed an estimated $11 million. By sheer earnings standards, he was probably the biggest star ever, anywhere; it almost didn’t matter that he was an artistic genius with more pure vocal talent than virtually anyone who’d ever been recorded.

Still and all, he was a creature of the popular culture and, as such, subject to the public’s whimsies. As the forties closed, talk leaked into the press about ties to communism and mobsters, there were ugly spats with writers, photographers, waiters, carhops, fans. His once-promising film career had sputtered—The Kissing Bandit, anyone?—and, after Frank made a wisecrack about one of Louis B. Mayer’s mistresses, MGM gave him his release. On the radio, he was bumped down from Your Hit Parade to a fifteen-minute, B-level show; on TV, CBS just plain dumped him.

He had trouble with his voice—he opened his mouth once at the Copa and couldn’t make a sound come out—and he seemed, further, to have lost his aesthetic way, letting Columbia’s new A&R man, Mitch Miller, talk him into making horseshit records with arrangements scaled wrong for his voice and dog barks thrown in as comic relief. The pathetic fall seemed poetically complete in 1952 when he returned to the Paramount Theater in support of a film of his own (the forgettable Meet Danny Wilson) and couldn’t even fill the balcony, much less stop traffic in Times Square.

Frank had gone from “extra added attraction” to King of the Universe in a couple of years; then, in about the same time span, he couldn’t get a job—and not a few people in the business were glad of it. With his ambition, quick temper, and iconoclasm, he’d done a lot of pissing off in his decade on the scene. His reputation was poison: When Capitol Records president Alan Livingston told his staff that he’d signed Sinatra at terms very favorable to the company, they groaned as one.

Presaging all of this calamity, turning the bobby-soxers against him and making him look like some pathetic pussy-whipped Milquetoast, was his wanton affair with Ava Gardner. Frank had never been faithful to Nancy in even a loose sense of the word, but, like many showbiz wives, she seemed willing to put up with peccadilloes even with such hot numbers as Marilyn Maxwell and Lana Turner. But this thing with Ava was more passionate and public than any of his other dalliances; it might have begun as a meaningless Hollywood fling, but they carried on all over the country throughout 1949, and Frank’s cardboard marriage finally became untenable. In the spring of 1950, he left the pretty Italian girl and the three cute kids that were his P.R. chastity belt. George Evans, enervated and skinny to begin with, bald from defending him, up and died one night after arguing with a columnist about Frank and Ava; he was forty-eight, and his heart had given out.

The affair and subsequent marriage were absurdly tempestuous and about as private as a presidential campaign; Ava was a lioness and Frank was her plaything. She was as promiscuous, lustful, hard-drinking, and profane as he was, and she had the hooks into him but good. She busted his balls mercilessly, running off with bullfighters and making him look like an ass in front of the world. He threatened suicide several times and took two stabs at it—once in Lake Tahoe with pills, once in New York with a razor. His disgrace and comeuppance were complete: Not only was he a has-been as a singer, an actor, and a performer, he was a flop as a cocksman. He was a joke: last year’s punch line.

When he finally managed to crawl out of his hole, then, it was all the more resoundingly triumphant. He achieved it in part through a movie role—Maggio, the pip-squeak private who died horribly at the hands of a bullying sergeant in From Here to Eternity. Throughout the latter half of 1952, Frank campaigned actively with Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn to get the part, and Cohn’s relationship with the Chicago Outfit’s West Coast point man, Johnny Rosselli, assured Frank at least a hearing. He got the job, he did really good in it, he got the Oscar, poof: He was all better. Once considered an overweening interloper in Hollywood, he was suddenly in the spring of ’54 a resilient, dues-paying member of the acting club. He had done the good thing; he had died for his fame and resurrected himself. He made more movies and he had hit after hit; he was even good in some of them.

At the same time, he took a new turn musically. No longer was he the reed-thin, warbling young crooner with a voice like a viola and a closet full of floppy bow ties. Now working for Capitol Records, he was more propulsive and dynamic, his voice richer and deeper—a cello. He was wearing fedoras and stylish suits; he was singing up-tempo about swinging and in dramatic, elegiac tempi about loss.

As in the movies, he seemed to have earned the right to his station; what’s more, as a singer, he expanded the very art form. He cut whole albums of songs built on the same musical ideas—saloon songs, swing numbers, waltzes—and even lyrical ideas: flying, dancing, the moon. Through the decade, he made the greatest pop records in history—one after another, sometimes as many as four a year.

Come 1959, he could look back twenty years and see a punk kid with nothing but ambition to his credit, he could look back a decade and see a big star dumped by the world, or he could look into the mirror and see the most influential and talented popular entertainer of the century.

Now what?

Frank was to become such a colossus of American popular culture that it would’ve been crazy in his heyday to think of him as needy. But his heroic Last Honest Man posture always had as a counterpart a little boy’s thirst for camaraderie and love. “I don’t think Frank’s an adult emotionally,” his friend Humphrey Bogart sniffed. Shirley MacLaine was more clinical, calling Sinatra “a perpetual performing child who wants to please the mother audience.”

Never mind all the gruff stuff offstage: The evidence of what was in his heart was in his art. Here was a man who lived amid an entourage that could expand, if he wished it to, to infinity, a man who had virtually every woman he ever desired, a man for whom no material comfort was unattainable; yet his music was at its richest and most intense when he sang piteously about loneliness. His familiar swinging cockiness would be overwhelmed by a gray, anguished fog hovering over a profound, hollow core—the achy soul of the Tender Tough. “I’ll Be Seeing You,” “These Foolish Things,” “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears out to Dry,” “In the Wee Small Hours,” “Angel Eyes,” “What’s New?,” “One for My Baby”—a world of crushed dreams, blasted hopes, distant, impossible romance. People called it suicide music and couldn’t understand why he slowed down every show to perform it—sometimes exclusively. But loneliness was the most vibrant color in his musical palette, and it obviously came from someplace very deep inside of him.

Indeed, he was born to it. He was, of course, an only child—try to name another Italo-American only child of his generation!—and grew up with a yearning for the companionship that his friends, neighbors, and cousins all enjoyed in their homes. The cash and clothing that his mother lavished on him were his first means of acquiring a society: He handed down suits to kids whose friendship he courted; he bought burgers and candy and comic books, cultivating early on a habit of “gifting”—treating the house to drinks or meals or clothes or women or more. The assets Dolly spotted him as a teenager—his wardrobe, his car, his sheet music arrangements, his portable sound system—they were a way for him to get a leg up in show business, true, but they were also a means of being part of a bigger group.

Which is what made it so perfect that Sinatra came into his own as a performer during the big band era, when a singer was by necessity a piece of a large, vibrant whole. The Harry James and Tommy Dorsey bands were like big clubs of chums for him—and he didn’t have to buy his way in, either. He gorged himself on the grand bonhomie that the bands instantly provided him—the card games, hazing, drinking, dreaming, and bonding that he and his fellow musicians engaged in during endless bus rides. He was like a congenital junkie who became addicted with his very first hit. As soon as he’d begun life in that dazzling musical fraternity, he wanted to live no other way.

Witness his recollection of the day on which he left James for Dorsey: January 1940, Buffalo; the James band was headed to Hartford; Frank would briefly visit New York, then join Dorsey in Rockford, Illinois; it was the single big break of his career, and he’d yearned for it and schemed to make it so; still, he struggled through the separation from his bandmates of a mere six months: “The bus pulled out with the rest of the boys at about half-past midnight. I’d said good-bye to them all, and it was snowing, I remember. There was nobody around and I stood alone with my suitcase in the snow and watched the taillights disappear. Then the tears started and I tried to run after the bus.” (This was, keep in mind, a married man with a child on the way.)

Of course, the Dorsey band was to offer Frank the same sort of companionship he enjoyed with James. Moreover, Dorsey himself would come to serve as a hero and model for his young singer; Frank dressed and spoke like him, he studied his famous breathing technique, he even took up his hobby of model railroading. Still, even with the prospect of a new gang of buddies assured him, he arrived in Illinois with the beginnings of his own coterie, a safeguard against ever finding himself staring longingly at the receding taillights of a bus again: Nick Sevano, a Hoboken haberdasher who dressed him, did his errands, and even lived with him and his family when they weren’t on the road, and Hank Sanicola, accompanist, business manager, and, as his girth suggested, sometime thumbbreaker.

Two years later, when the allure of profits and aesthetic freedom drove Sinatra to seek his release from the Dorsey band, he was, once again, bereft of bandmates, so he gathered to his bony bosom a band, of sorts, of his own. He expanded his entourage to include such semiregulars as Mannie Sachs, a Columbia Records executive; Ben Barton, his music publisher and business partner; composer Jimmy Van Heusen; lyricist Sammy Cahn; bruisers Tami Mauriello and Al Silvani; and Jimmy Taratino, a boxing writer whose mob ties eventually formed a costly web for the singer. And he gave them all, guilelessly, a name: the Varsity.

En masse, the Varsity hit all the swell spots—nightclubs, saloons, showbiz eateries, and, especially, the Friday night fights at Madison Square Garden, where they mingled with mobsters, Times Square sharpies, and other supernumeraries of the fight game. Grown men actually vied to be admitted to their numbers, but that privilege was rarely granted, and the resultant loyalty of its members was embarrassingly high: When Mauriello was inducted into the service and sent overseas to fight, he gave Frank his golden ID bracelet, which the singer wore with puppy-dog pride.

After the war, the Varsity evolved, with some members resuming their lives without Frank (not always peaceably or voluntarily) and others accompanying him out West, where he had joined the extended family of MGM studios. There was a Softball team—Sinatra’s Swooners, with uniforms and cheerleaders (and Ava Gardner as, ahem, honorary bat girl); there were card games, pub crawls, the works.

But then the spiral that demolished his career began: Divorced, his voice uncertain, his name connected with reds, hoods, and a dozen drunken little fistfights, without a record company, film contract, or agent to call his own, he suddenly didn’t seem like a Sun King anymore. A few steadfast partisans held on; the larger crowd vaporized.

It was a subtle thing: People didn’t so much snub Frank as stop courting him. He couldn’t get tables in the same restaurants, or not the same tables, anyway. He couldn’t round up a poker game or gang of drunks to obliterate a night with him. Early one morning at the dawn of the fifties, Sammy was walking through Times Square, overjoyed with just having been allowed to break the color barrier long enough to schmooze with the big stars at Lindy’s. He passed the Capitol Theater—the place where Frank had once hired him and his dad and uncle when they were still unknown—and lo, there Frank was, walking along with a wounded air.

“Not a soul was paying attention to him,” Sammy recalled later. “This was the man who only a few years ago had tied up traffic all over Times Square. Thousands of people had been stepping all over each other trying to get a look at him. Now the same man was walking down the same street and nobody gave a damn.”

For Sammy, to whom the clubbiness and fame of showbiz were brass rings worth one’s very soul, it was a stunning sight. “I couldn’t take my eyes off him, walking the streets alone, an ordinary Joe who’d been a giant. He was fighting to make it back again but he was doing that by himself, too. The ‘friends’ were gone with all the presents and the money he’d given them. Nobody was helping him.”

There were others who sensed Sinatra’s pain and tried to help. L.A. gangster Mickey Cohen, an admirer of the singer’s (“If you call Frank’s hole card,” he said approvingly, “he’s gonna answer”), tried to rally his spirits by hosting a testimonial dinner for him at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Instead, the sparsely attended event simply underscored Sinatra’s dilemma. As Cohen recalled in his hilarious autobiography, “A lot of people that were invited to that Sinatra testimonial, that should have attended but didn’t, would bust their nuts in this day to attend a Sinatra testimonial. A lot of them would now kiss Frank’s ass after he made the comeback, but they didn’t show up when he really needed them. I don’t know the names of a lot of them bastards in that ilk of life, but I remember the people that I had running the affair at the time telling me, Jesus, this and that dirty son of a bitch should have been here.”

At the time, Frank wasn’t really keeping up with all the snubs—he was far too bewildered by life with Ava and the prospect of resuscitating his career. But he was still Dolly’s boy, and he had to have noticed the slights. And if he’d ever shown himself to be curt and exclusive before bottoming out and being left behind, when he recovered he became more demanding than ever of the loyalty of those he allowed around him. Only the surest would be abided.

Such a one was Humphrey Bogart, the movie god whose blessing upon Frank was one of the lifelines that kept him hopeful that he might someday emerge from the straits in which fate had left him foundering.

In all Hollywood, nobody had a flintier or more enviable reputation than Bogart. An Upper West Side sissy boy who went from playing juvenile walk-ons to psychotic killers, paranoid adventurers, and cynics with soft hearts, he danced just within the boundaries of the game. His drinking, womanizing, and bellicosity never quite made the front pages, his bad-mouthing of bosses never quite stooped to insubordination, and his liberal political beliefs and headstrong independence never quite severed him from the basis of his wealth, fame, and popularity. The one potential faux pas of his life—his affair with starlet Lauren Bacall—was easily cast by studio flacks and gossip mavens as a great May – December romance, especially after the couple wed and started a family.

For a large part of the movie colony, Bogie was a cult hero—a Knight of the True Way. He did his work best by being something that no one else could be: himself. Off-camera, he drank away afternoons in restaurants, went out of his way to upset prigs at parties, cruised the Pacific on his sailboat, and made, with his young wife, a home that offered haven to those very select few in his business who, like him, weren’t fooled for a minute by their own press.

Nothing, but nothing, rattled Bogart more than the sight of Hollywood kissing its own behind, especially over unproven new talent, and especially unproven male talent that was rooted in alleged sex appeal. So in 1945, when the jug-eared boy singer who made the bobby-soxers wet their pants showed up in town to great foofaraw, Bogart was ready to dismiss him out of hand. They ran into one another for the first time at the Players, the Sunset Boulevard restaurant, bar, and theater owned by Preston Sturges.

“They tell me you have a voice that makes girls faint,” said Bogart, an expert needler. “Make me faint.”

Sinatra stood right up to him: “I’m taking the week off.”

Bogart liked the response, liked the kid. And Frank, of course, saw in Bogart all the things he always wanted to be: aloof, profound, world-weary, slightly drunk, slightly sentimental, romantic, tender, tough, loyal, and proud. (He could take his hero worship too far. Once, when a date of Frank’s declared, in Bogart’s presence, “You sound like Bogie sometimes,” the actor laughed and said, “Don’t remind him, sweetheart, the poor bastard’s trying to kick it!”) He tried to cajole producers into casting him in Knock on Any Door as a tough street kid opposite Bogart’s impassioned lawyer; such was Sinatra’s stock as an actor that the role went to John Derek.

Nevertheless, the two men got into the habit of spending time together whenever the occasion arose, which, given Frank’s hectic schedule of filmmaking, recording, and touring, wasn’t often. In 1949, though, Frank moved his family from Toluca Lake to Holmby Hills, just blocks from Bogart’s house. This new proximity allowed the two stars more frequent contact; soon after moving into the neighborhood, Sinatra organized a guys-only baby shower for Bogart when Lauren Bacall was pregnant with their first child.

The relationship got a little strange. After Frank had left Nancy and the kids, he was still welcome in their house; he would frequently crash on his estranged wife’s couch after nights of bingeing with Bogart, shuttling between the two homes as if, in his mind, they constituted one. “He’s always here,” Bogart told a reporter. “I think we’re parent substitutes for him, or something.” Bacall empathized with Frank’s need for companionship, but Bogart warned her against getting wrapped up in it. “He chose to live the way he’s living—alone,” he admonished his wife. “It’s too bad if he’s lonely, but that’s his choice. We have our own road to travel, never forget that—we can’t live his life.”

In fact, Bogart was one of the few people who were willing to tell Frank exactly what they thought of some of the things he did. There was the time he hosted Sinatra, David Niven, and Richard Burton for a night of drinking on his beloved yacht, Santana. Frank was at a career ebb, and he passed part of the night on deck, serenading yachters on the other boats moored nearby; Bogie grew so irate with Sinatra’s preening performance, recalled Burton, that he and Frank “nearly came to blows.”

There was the time when Frank, riding high on the early reviews for From Here to Eternity, visited his hero in search of approval. “I saw your picture,” said Bogie. “What did you think?” Frank asked. Bogart simply shook his head no.

And there was Bogart’s famous line about Frank’s thin-skinned egoism: “Sinatra’s idea of paradise is a place where there are plenty of women and no newspapermen. He doesn’t know it, but he’d be better off if it were the other way around.”

Still, there was a bond between the two: father-son, mentor-acolyte, king-pretender—somehow the dynamic was agreeable to them both. They both reviled the traditional cant and decorum of Hollywood protocol, they both had deep political concerns for the everyman, and they both loved to needle people, especially the thin-skinned twits their lives as famous performers gave them so many chances to meet. Frank was always welcome in the Bogart home; the Bogarts, in turn, accepted his hospitality when he would want to scoop up a gang of pals and run off for a weekend in the Springs or Vegas.

In June 1955, for instance, he gathered a dozen or so chums, rented a train, and took off to catch Noel Coward’s opening at the Desert Inn (yes, that Noel Coward and that Desert Inn; Vegas was always great with novelties). During that particular spree, legend has it, the group had gotten so deep into its cups that Bacall was startled by their debauched appearance when she caught a gander of them ringside in a casino showroom. She looked around at all the famous flesh—Frank; Bogart; Judy Garland; David Niven; restaurateur Mike Romanoff; literary agent Swifty Lazar and his date, Martha Hyer; Jimmy Van Heusen and his date, Angie Dickinson; a few well-oiled others.

“You look like a goddamn rat pack,” she muttered.

It broke them up. A few nights later, back in Romanoff’s joint in Beverly Hills, she walked in and declared, “I see the rat pack’s all here.” Again, a big hit, but this time the joke picked up momentum of its own: They founded an institution—the Holmby Hills Rat Pack. They drew up a coat of arms—a rat gnawing on a human hand—and coined a motto: “Never rat on a rat.” And they assigned themselves ranks and responsibilities: Frank (and you can just see him standing there excitedly conducting the whole sophomoric enterprise) was named Pack Master; Bacall, Den Mother; Garland, Vice President; Sid Luft (Garland’s husband and manager), Cage Master; Lazar (so full of pep they gave him two jobs), Treasurer and Recording Secretary; and humorist Nathaniel Benchley, Historian.

Bogart was named Rat in Charge of Public Relations, and the next day he spoke about the whole silly business with movieland reporter Joe Hyams. “News must be pretty tight when you start to cover parties at Romanoff’s,” Bogart responded when asked about the Rat Pack, but, assured that the story would be treated with such overblown pomp that it would obviously be seen as a goof, he acceded to an interview. The Rat Pack, he declared, was formed for “the relief of boredom and the perpetuation of independence. We admire ourselves and don’t care for anyone else.” They’d briefly considered adding some absent friends to the roster, he said, but the requirements were often too high: When Claudette Colbert, for instance, whom they all liked, was nominated, Bacall insisted that she not be admitted because she was “a nice person but not a rat.” Hyams dutifully jotted it all down, agreed once again when Bogart insisted that “it was all a joke,” and reported it the next day in the New York Herald Tribune.

Hyams’s scoop was true enough: There was indeed a group, centered around Bogart, that hung out together to the exclusion of the remainder of Hollywood, which, though they were part of it, they had no qualms about mocking. “You had to be a noncomformist,” said Bacall, “and you had to stay up late and drink and laugh a lot and not care what anybody said about you or thought about you” (one last criterion: “You had to be a little musical”). But the idea of an organization and a creed and all that, that was strictly a lark, another of Bogart’s beloved practical jokes taken to an absurd height.

Nevertheless, the publicity incited a reaction that revealed that Bogart’s attitude wasn’t necessarily laughed off by the world at large. Hollywood was an extremely cliquish society, and Bogart’s clique had always taken the perverse ethical stand that the local social mores—and the cliques it spawned—were bullshit. The notion of such a disdainful group legitimizing itself into an honorable cult, even in jest, struck some in the movie colony as an affront.

The poor schmucks didn’t get the joke: There was no such thing as the Rat Pack, not really. The principals might all get together at Romanoff’s or Bogart’s house and carry on like a drunken fraternity, but that’s all they really were: There were no dues or meetings or minutes or rules; there were just nights together in a company town of which they were all valued—and jaded—assets. If they wanted to pretend they were wild rebels, fine; they still all showed up on movie sets and in recording studios bright and early the next morning with their material prepared and their bodies and voices ready to perform. The whole Rat Pack thing was like bowling or square dancing or watching TV—the things they would’ve done together if they’d been squarejohns living between the coasts and not movieland royalty.

The subtle caste system out of which the Rat Pack arose became somewhat more manifest in 1956 when Bogart was diagnosed as having incurable throat cancer. A parade of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances spent the ensuing year paying fealty to this man who neither wanted nor acknowledged their sympathetic indulgence. “Haven’t you people got anything better to do than come over here and bother me?” Bogie would admonish his guests. “How am I supposed to get any rest with the likes of you coming every day?” It was the sandpaper wit they’d come to expect from him, and they cherished it.

Despite his crusty bravery, though, the last year of Bogart’s life was a horror of weight loss, discomfort, incapacity, depression. Bacall, still in her early thirties and an established star in her own right, bore it as well as she could, but she needed occasional escape from the traumatic scene unfolding in her home. Bogart insisted that she continue to go out on the town, and he was grateful whenever she took him up on the offer, most frequently escorted by Sinatra.

Frank had determined to remain steadfast during his idol’s illness, visiting regularly even though he was mortified by Bogart’s condition. “It wasn’t easy for him,” Bacall remembered. “I don’t think he could bear to see Bogie that way or bear to face the possibility of his death. Yet he cheered Bogie up when he was with him—made him laugh—kept the ring-a-ding act in high gear.”

More than that, it has been suggested, he filled the loneliness in Mrs. Bogart’s life with more than just suppers at Romanoff’s. Intimates of the group whispered about a budding love affair between Sinatra and Bacall—“It was no secret to any of us,” said one—and they pointed to a Rat Pack trip to Las Vegas for Bacall’s birthday which Bogart skipped, preferring to take his young son, Stephen, to sea on the Santana.

Bacall was aware of the dynamic, admitting that Bogart “was somewhat jealous of Frank. Partly because he knew I loved being with him, partly because he thought Frank was in love with me, and partly because our physical life together, which had always ranked high, had less than flourished with his illness.”

When the end finally came, Frank, a fixture in the Bogart household, was nowhere to be found. Bogart died on January 14, 1957, when Frank was in New York working a club date at the Copacabana. He canceled three days’ worth of shows (Sammy, who was starring on Broadway in Mr. Wonderful, and Jerry Lewis, who was in the midst of a successful solo run at the Palace, subbed for him), but he didn’t return to California for the funeral, holing up instead in his Manhattan hotel.

Even if he didn’t have any reason to feel guilty, he couldn’t have been too comfortable back on Maplewood Drive. Bogart’s house had become a kind of shrine to his final days: His favorite chair, his clothes, his photos, his very aura hung about the place unaltered. Bacall couldn’t bring herself to change a thing, even though she, too, found it difficult to live amid it all. Frank—always indulgent of widows—gave her and her children the run of his Palm Springs estate for as long as they needed it.

By the end of 1957, the time had arrived when he could offer her more. His Mexican divorce from Ava Gardner, a mere legal technicality in their shattered relationship, had coincidentally come through that June. Frank and Bacall began seeing one another socially, with all observers assuming they were intimate. When Frank entertained at his homes in Coldwater Canyon or Palm Springs, Bacall was hostess, and she was his date for the Las Vegas premiere of Pal Joey and the L.A. premiere of The Joker Is Wild. It made perfect sense: the Pack Master and the Den Mother, a golden couple come together after their storied marriages had ended, respectively, in passionate disaster and heart-wrenching tragedy.

Despite the fairy-tale appearance of the romance, though, they had to endure one another’s considerable faults. Bacall got into the habit of checking up on him whenever he was with other women—taking a phone call from her while his latest conquest listened along in his hotel room, he made a big show of his impatience, answering, “Yes, Captain. Yes, General. Yes, Boss.” In exchange, she was subject to Frank’s moodiness. His swings between indulgent companionability and icy remove rattled her, especially, as she noted later, since she had previously “been married to a grown-up.”

But her will was no match for his; like many of Sinatra’s women, she was eager to do anything to please him. She even went so far as to give up her home on Maplewood Drive, in part because of the painful memories the place harbored for her, in part because, as she later told her son, “I don’t think Frank was comfortable in that house. The ghost of your father was always there and I knew that Frank would feel better if I moved.”

Her sacrifices and persistence paid off: In March 1958, after another of his sullen absences, he popped back onto the scene and proposed marriage. She accepted, agreeing to his desire to keep their intentions private for a while. Frank went off to a club date at the Fontainebleau; Bacall stayed in L.A. and kept denying rumors whenever reporters—even buddies like Joe Hyams and Richard Gehman—got snoopy. But she couldn’t keep from blabbing to gossipy little Swifty Lazar, who spilled the beans to Louella Parsons, who made national headlines with it, which drove Frank into a fit.

“Why did you do it?” Frank harangued Bacall from Miami. “I haven’t been able to leave my room for days—the press are everywhere. We’ll have to lay low for a while, not see each other for a while.”

Chastened, even in her innocence, Bacall did as she was told—and Frank never tried to contact her again. “He behaved like a complete shit,” she later said. “He was too cowardly to tell the truth—that it was just too much for him, that he found he couldn’t handle it.”

But there might have been a bigger truth: Maybe Frank had realized that he didn’t have to marry Bogie’s widow to become the actor’s true heir and King of the Rat Pack. Maybe he realized that he could simply up and start a brand-new Rat Pack of his own.

105 percent (#ulink_0998bc73-a03c-5f56-b9c9-6cf8405d9494)

By at least one account, it was Dean’s idea: The story goes that he had just rescued his career with his eye-opening work on The Young Lions, and he was sharking for a new project. In the summer of ’58, he and his wife attended the premiere of Kings Go Forth, Frank’s latest picture, and he walked over to Frank like he was pissed about something.

“You bum!”

Frank played along: “What’ve I done now?”

“You’re hunting for a man for your next picture who smokes, drinks, and can talk real southern. You’re looking at him.”

“Well, whattaya know …”

Cute. And there might even be some truth to it, but the likely scenario is somewhat less colorful. For starters, if it had happened, it would’ve marked the first time in his life that Dean Martin went out of his way to further his career; indeed, one of the reasons for the dissolution of Martin and Lewis was that Jerry’s overweening ambition struck Dean as degrading. More than that, the story assumes that Frank, who was forever throwing his chums roles in his movies (he once slated his squeeze Gloria Vanderbilt for a role in the western Johnny Concho, an inspiration lost to cinematic history when their love affair hit the rocks), hadn’t already considered Dean for a role that he was practically born to play. In fact, it ignores altogether just how close Dean and Frank, a couple of olives off the same tree, had recently become.

For their first couple decades in the business, they hadn’t palled around much, even though they’d been crossing paths since the war. Dean’s big ticket to New York came when he followed Frank into the Riobamba nightclub; they shared a record label; they had appeared together on TV a few times; but they were no more a two-act than, say, Perry Como and Vic Damone.

Recently, though, that had begun to change. A couple of years earlier, Dean took in a Judy Garland show in Long Beach in Frank’s company (Sammy and Bogey were also there), and they all popped onstage with the star for an impromptu number. After that, Frank appeared on a couple of Dean’s NBC specials—on one, they sang a duet of “Jailhouse Rock”!—and Dean returned the favor when Frank began his catastrophic series on ABC.

Frank had grown to feel something fraternal for Dean. He would always be the first mate, a brother.

But it hadn’t always been that way.

“The dago’s lousy, but the little jew is great”: thus Frank on Martin and Lewis, circa 1948, when the new singing-comedy act was tearing the roof off Frank Costello’s Copacabana and quickly becoming the hottest thing in showbiz.

In a sense, it was an entirely apt critique. Martin and Lewis, one of the greatest two-man acts in history, was really Jerry Lewis’s vehicle. Dean, the tall, handsome, crooning straight man, was more or less along for the ride. And when the ride ended, when Martin and Lewis devolved into an ugly spitting contest and finally broke apart, “the little jew” went on to solo success, just as everyone predicted, while “the dago” initially floundered.

It wasn’t that Dean didn’t have the chops. He had a charming voice in the Crosby mood—a stylish singer, if never a real artist. He cut a great figure in a tux, golf clothes, even overalls: real movie star looks. And he was funny, with a gift for whimsical one-liners and a canny, low-key delivery that were completely wasted in the years he spent alongside the spotlight-hogging Jerry.

But he seemingly didn’t have the drive to go it alone. He was ten years older than Jerry and struggling under an absurd burden of debt when the two teamed up and launched their rocket to the moon. For all his gifts, he’d never, as a solo, gone anywhere useful. And for all the success that he eventually enjoyed, it seemed like the only reason he’d ever gotten anywhere at all in the world was that he’d been somehow blessed to thrive in it. He didn’t have to work, he didn’t have to sweat, he didn’t have to think; he just had to show up and get paid—his whole life long.

Consider: Dean never wanted to get his hands dirty, so he learned how to deal cards and how to sing, and he made a living at it; he was too sanguine to chase women, so they threw themselves at him; he didn’t have the fire in the belly to make himself a showbiz star, so he met a couple of wildly ambitious guys—Jerry and Frank—who dragged him along.

It was even luck that Dean was born in America—his father’s bad luck, that is, to have been born in Abruzzi, a wind-scored plain south of Rome, dotted with cave-riddled mountains. Abruzzi spit forth disconsolate young men and women and exiled them to the New World, where they choked slums and factories. Steubenville, Ohio, where Dean’s people turned up, was filled with steelworks that swallowed up Italian and Greek immigrants like so much coke.

After seeing the infernal wreckage of his older brothers, who’d emigrated before him, Gaetano Crocetti, Dean’s father, decided that selling his soul to a foundry wasn’t for him. He chose instead one of the few respectable blue-collar jobs open to a young Italian immigrant, apprenticing himself to a barber. With his name anglicized (he became Guy Crocetti, pronouncing his last name Crowsetti) and his future assured, he was able to woo and wed Angela Barra, an orphan girl from the neighborhood with a bit of barbed wire in her makeup. They were kids when they married, but by June 1917, just three years later, Guy had his own barbershop, the couple had a one-year-old boy, and Angela produced another son. Born prematurely, he wasn’t christened until the fall: Dino.

The Crocetti boys were raised among a healthy tribe of relatives and neighbors. They had a comfortable home, plush Christmases, plenty to eat; there were no riches, exactly, but nor were there rags. Guy was naturally easygoing—a good barber. He sat genially among the other men, sipping wine, eating tangerines and nuts, schmoozing away the twilight in the Abruzzese piazza that they simulated in their hearts and minds.

But Angela had grown up under more brutal circumstances than her husband—her mother had been committed to the Ohio Institution for the Feeble Minded—and she didn’t see the world as so accommodating a place. She spoiled her sons like any good Italian mother, true, but she also tried to prepare them for the world by instilling her toughness in them, teaching that they mustn’t be weak or free with their feelings, that they should make their way in the world like men.

Dino learned such lessons well. Like his dad, he refused to submit to a future in the foundries, but he wasn’t soft enough for barbering. His mother’s strength had given him the confidence to seek other opportunities—of which Steubenville was deliriously full. In fact, the town, known throughout the region as Little Chicago, was wide open: pool halls, strip joints, cigar shops fronting for gambling parlors; only a sucker, it seemed, could grow up amid it and not try to cash in.

By his early teens, Dino was running with a shady gang from around the neighborhood and showing up in school with his pockets full of silver dollars. At sixteen, he slipped out of school altogether and for good. He was tall and athletic, with dark, wavy hair and a bold Roman nose. He tried to turn his good looks, lithe body, and quick hands into a profit as a welterweight boxer—Kid Crochet. He flopped. So he turned to odd jobs, including a brief, terrifying stint in a steel mill—a vision of hell as a place where you spent eternity if you lacked the moxie to avoid it. He finally broke through into the sort of racket to which he aspired: dealing poker and blackjack in a local gambling den.

He took to fancy clothes and easy women. He and his pals ran around nights drinking, gambling, carousing. Guy and Angela disapproved, but their boy breezed along in merry indifference: Good times like these, who worried about the future?

Yet even though he was always one of the boys, there was something in Dino that set him apart: He sang—a fanciful affectation, perhaps, but one acceptable to Italian boys of his age, partly out of the respect accorded opera singers in their culture, and partly because of the novelty of the radio and the phonograph, which was making stars of crooners. It was the only thing that Dean applied himself to that didn’t have the spoor of sin about it; he even took vocal lessons from the mayor’s wife. And he performed in clubs and taverns and at parties whenever there was an open mike and a band willing to back him.

His pals encouraged him; his bosses liked it. Soon enough, he took work as a singing dealer at a sneak joint outside of Cleveland. He was approached by Ernie McKay, a bandleader from Columbus who offered to take him on. Before long, another eye was caught: Cleveland bandleader Sammy Watkins hired him away in the spring of 1940 to come to the shores of Lake Erie and play to a ritzier clientele.

That winter, performing under the newly minted stage name Dean Martin, he met a fresh-faced college dropout named Elizabeth MacDonald. Two years later, they married. Nine months after that, Dean was a father looking for a way to make more money.

A local MCA agent called: Frank Sinatra had canceled a date at the Riobamba in New York, and the club’s owners were willing to give this new Italian boy singer from Cleveland a shot. Dean wanted to go, but he had to pay a steep price: For freedom from his contract, he gave Watkins 10 percent of his income for the next seven years; the agent took another 10 percent. In September 1943, at $150 a week, he debuted in Manhattan, the world’s biggest candy store for a guy with his kind of sweet tooth.

The obvious pleasures aside, New York didn’t prove easy. Money didn’t come fast enough, and when it did, it disappeared even quicker. Hands reached into his pockets. An old Steubenville acquaintance turned up wanting to serve as his manager, offering $200 ready cash in exchange for a 20 percent piece of his earnings. Dean was in debt everywhere; he took the deal. He was courted by a Times Square agent who offered another cash payment for 35 percent of his earnings; he took it. Comedian Lou Costello offered Dean more money for another 20 percent; he took it.

Dean got his patrons to broker a nose job, turning the schnozzola he’d inherited into something more aquiline. He signed up for a nonsponsored radio show whose musical director took an interest in his future. Dean milked the guy for yet another cash payment in exchange for 10 percent of himself, making a grand total of 105 percent; for every dollar he earned, had he been up front with all his partners, he would’ve been out a nickel—but, of course, he never bothered to pay anybody.

In August 1944, he was booked into the Glass Hat nightclub, just another gig that only changed his life forever. Down the bill and serving as emcee was a skinny, acned kid pantomimist from New Jersey named Jerry Lewis: destiny with an overbite.

Like everyone else, Jerry adored Dean, and he grabbed every opportunity he could to pal around with him at gigs, at restaurants, at after-hours schmoozes. He even began edging into Dean’s act. In the winter of 1945, when Dean was topping the bill at the Havana-Madrid club and Jerry was emcee, Jerry kibitzed from offstage as Dean sang. Dean didn’t care much about what he was doing anyhow, so he played along, getting an appreciative rise out of the crowd.

The following summer, Jerry was playing the 500 Club in Atlantic City, a joint with ties to the Camden mob, and he found himself on the verge of being fired. He called New York in a panic, found out that Dean was available, and told the guys who ran the club that Dean was a great singer and that the two of them did “funny shit” together. Management bit, Dean got hired, and one of the brightest Roman candles ever to hit showbiz was lit.

Within a year, Martin and Lewis were the biggest act in nightclubs; two years later, they were the biggest act in the world: TV, movies, radio—they overran every single medium available to them. They made sixteen hit films, had the nation’s number one TV show, and were one of the top-drawing live acts in the business, creating a sensation that recalled nothing so much as Sinatra’s bobby-sox heyday; they even tied up traffic in Times Square.

The act was a farce, equal parts nightclub slickness and burlesque puerility. Dean would stand soberly (the drunkie routine didn’t start till after Jerry) and try to put over a tune—“Oh, Marie,” say, or “Torna a Sorriento”; Jerry would cavort wildly, trying to horn in on the act or take control of it for himself—a realer bit of shtick than anyone in the audience knew.

Of course, Dean could actually sing as well as play straight, combining the best of George Burns and Desi Arnaz with sex appeal neither of them had. But the point of Martin and Lewis was no more straight vocals than it was dramatics. Jerry would squeal and wheedle and practically run out and kiss the audience’s ass to gain its love, and Dean would stand in dumbfounded awe of the spectacle, a substitute for the viewer, bemusedly, indulgently watching as his little buddy made a travesty of the accepted forms of showbiz. If Dean occasionally dove in and capered as well, that made it even more fun; for the most part, though, he hung back and let Jerry make a merry schmuck of himself.

This was the Dean Martin that the world came to love—the suave geniality covering up the calculating hedonism, the easy affability that belied the inner selfishness, the game sport whose willingness to go along with his wacky partner onstage was utterly at odds with the taciturn midwestern reserve that marked him when the arc lights dimmed. For four decades, he would project as much dignity and self-assurance as he ever did sauce or testosterone or jaundice.

The public loved him and it loved his partner and it loved the two of them together. Even when he divorced Betty and married Jeannie Biegger, a gorgeous-blonde beauty queen from Miami, he couldn’t tarnish the golden glow of Martin and Lewis.

It took the two of them to do that.

By 1954, they weren’t such good pals anymore. Jerry was styling himself a creator of artful comic narratives in a variety of media. He sought publicity and creative control—something, ultimately, other than partnership—and he couldn’t stand to sit beside his pool for more than a few hours without setting himself to some sort of project.

Dean didn’t want to be worked to death when they were doing so well; he mocked Jerry’s aspirations as “Chaplin shit” and was less and less concerned with keeping a happy public face on their relationship. After a few well-publicized snubbings, Jerry grew haughty enough to shove Dean, and Dean shoved back—harder, and with no little relish. It got ugly, and by July 1956, on the Copacabana stage that was their first great showcase, they played their last gig together.

Everyone in show business knew that Jerry would do great, but most predicted a dire future for Dean. And when he debuted as a single, it was disastrous. His first picture, Ten Thousand Bedrooms, was numbered for years among the great movie turkeys of all time. Cynics were predicting he’d be out of the business altogether within months.

Like Frank, though, he was rescued by fate in the form of a new singing persona and a World War II movie. Actually, Dean didn’t so much change his voice as what he did with it. Always languid, he became frankly indifferent; without Jerry around to interrupt his singing, he began to act the drunk and interrupt himself. It suited him; audiences loved it.

Another break: In 1957, his agents got him cast in a key role in the screen version of Irwin Shaw’s best-selling novel, The Young Lions. Playing a roguish Broadway singer miscast as a G.I., Dean held his own against Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando and was suddenly a hot commodity once again.

He might have drifted into anything, but he never really got the chance to go it purely alone; probably he didn’t want it; he might have even been scared. Within two years of splitting with Jerry, he found himself teamed, unofficially but semipermanently, with Frank, starting with a trip to some sleepy town in the Midwest.

Of course, Frank knew that Dean would be a perfect choice for the role of Bama Dillert, a honey-drippin’ card shark in the upcoming film Some Came Running. A gambler, roué, souse, and cynic with a southern accent just like the one Dean sported as a bit of shtick, he was capable of being played right by no other actor in the world. If it took till mid-’58 for Frank to offer Dean the role, the likely reason is that he was waiting to see how The Young Lions turned out.

It turned out fine; the role was Dean’s.

Like Frank’s career-saver, From Here to Eternity, Some Came Running was based on a big fat book by James Jones (even at twelve hundred pages, it had been cut in half by editors at Scribner’s). Frank was cast as Dave Hirsch, an ex-G.I. with a literary bent who drunkenly wanders back to his small Indiana hometown, where he does battle with his respectable older brother, falls for a priggish schoolmarm, and is in turn fallen for by a big-city floozy who has floated into town in his wake. MGM production head Sol Siegel had bought the book for $200,000 before it was published, then assigned it to in-house auteur Vincente Minnelli, who’d almost entirely abandoned the gaiety of his classic musicals for broody, atmospheric melodrama. The $2-million production (not counting Frank’s $400,000 guarantee against a piece of the gross) would be shot throughout the late summer and fall of 1958, with eighteen working days scheduled for location in Madison, Indiana, population 10,500, a wee bit of Americana just across the Ohio River from Kentucky, where mob-run casinos such as the plush Beverly Hills Club flourished.

Dean signed on to play Bama, an itinerant gambler who befriends Hirsch, and the cast was rounded out with Arthur Kennedy as the banker, Martha Hyer as the prig, and Shirley MacLaine as the floozy (“the pig,” as Bama calls her), Ginny Moorhead. MacLaine knew Dean from having worked with him and Jerry on Artists and Models, her second film, three years earlier; she’d met Frank soon after on the set of Around the World in 80 Days—his one-shot in that dull parade of cameos came when she popped into a Barbary Coast saloon where he was playing the piano.

MacLaine was a kid when she showed up in Madison—just twenty-four, with a two-year-old daughter and a husband who spent most of his time on business in Tokyo. She’d worked in Hollywood for three years, but nothing in her green, bubbly life prepared her for the world in which Frank and Dean lived. For two weeks in Indiana, she got a glimpse of the strange, intoxicating lives to which powerful men entitled themselves.