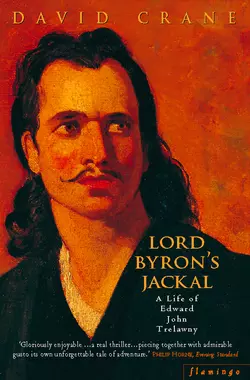

Lord Byron’s Jackal: A Life of Trelawny

David Crane

‘There is a mad chap come here – whose name is Trelawny… He comes on the friend of Shelley, great, glowing, and rich in romance… But tell me who is this odd fish? They talk of him here as a camelion who went mad on reading Lord Byron’s ‘Corsair’.’ JOSEPH SEVERNDavid Crane’s brilliant first book investigates the life and phenomenon of Edward John Trelawny – writer, adventurer, romantic and friend to Shelley and Byron. Very reminiscent of YoungHusband in its mix of biography, history and travel writing it is a sparkling debut.Trelawny was, unquestionably, one of the great Victorians. He made a career from his friendship with Byron and Shelley and with his tales of glory from the Greek War of Independence. His story is one of betrayal and greed, of deluded idealism and physical courage played out against one of the most ferocious wars even the Balkans has seen.There has been no general biography of Trelawny for nearly twenty years, no history of the philhellene role in the Greek War of Independence for even longer.

LORD BYRON’S JACKAL

THE LIFE OF

Edward John Trelawny

DAVID CRANE

CONTENTS

Cover (#uf38b1661-9032-543b-8eea-ea1748869281)

Title Page (#u7709384b-7aef-51d5-a289-a384a6f67ddb)

List of Maps (#u8f44e65f-dbe3-58c5-bcac-c1bb7080e08a)

Nauplia (#ulink_84ccb8da-2002-5cfa-bda9-d1936f2f1be4)

1 The Wolf Cub (#ulink_e921efb5-fdd0-5a7b-9550-5d8a834e4c29)

2 The Sun and the Glow-Worm (#ulink_8ee78dbb-86e7-5ac6-9e08-ad4a3cd64848)

3 Et in Arcadia Ego (#ulink_cc7b1391-8f69-55a0-a293-9be6dd1fe7c9)

4 Odysseus (#litres_trial_promo)

5 The Death of Byron (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Parnassus (#litres_trial_promo)

7 The Plot (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Whitcombe (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Assassination (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Humphreys (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Enter the Major (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Shame (#litres_trial_promo)

13 The Last of Greece (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Going Public (#litres_trial_promo)

15 The Keeper of the Flame (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes to the Text (#litres_trial_promo)

Reference Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Sources and Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

LIST OF MAPS (#ulink_3019c1e2-c8d0-56af-9f18-114f651f3fe3)

Greece 1823–1827

Major Francis D’Arcy Bacon’s Journey 1823–1825

NAUPLIA (#ulink_3d2faa83-28c7-56d7-9840-0e162e6e4282)

‘What a queer set! What an assemblage of romantic, adventurous, restless, crack-brained young men from the four corners of the world. How much courage and talent is to be found among them; but how much more of pompous vanity, of weak intellect, of mean selfishness, of utter depravity … Little have Philhellenes done towards raising the reputation of Europeans here!’

Samuel Gridley Howe

(#litres_trial_promo)

ON 6 FEBRUARY 1833 a seventeen-year-old Bavarian prince entered the town of Nauplia as the first king of Modern Greece. Out in the Gulf of Argos the ships of the sponsoring powers rode at anchor in the bright spring sunshine. French, Russian and British bands serenaded each other across the water in an improbable display of amity, while from the batteries on shore salute after salute rolled across the bay in tribute to Christendom’s youngest nation.

To the pragmatist and romantic alike there can have been no more fitting place for Otho to begin his reign than here on the Argolic Gulf under the watchful gaze of Europe’s navies and Greece’s Homeric past. Nothing, it seemed, had been left to chance to guarantee his future. The civilized world had given its blessing and its money. A loan had been provided to buttress his new country through her first years, an indemnity paid to her old Ottoman masters to rescue her from her troubled past.

Inside the town Bavarian and French troops stood ready to enforce Europe’s choice on a population only too accustomed to dissent, but for the moment the precautions were unnecessary. Mountain Suliotes and island merchants, sailors and Moreot bandits, Peloponnesian peasants and Phanariot politicians waited to greet the young king as their saviour from years of war and chaos. As Otho rode on his white horse through the cheering crowds into the reconquered Turkish town, the peculiar spell of Greece, its unique hold on the nineteenth century as the cradle of Western culture and the champion of Christianity, took on a palpable form that seemed in itself a guarantee of the new order.

For a dozen years this small town on the eastern coast of the Peloponnese, some forty miles south of Corinth, had exercised the same charm over the imaginations of Europe and America. From that moment in 1821 when Bishop Germanos had raised the standard of revolt and called on Greece to throw off four centuries of Ottoman rule Nauplia had been as familiar as any city in Europe. Its news was carried in newspapers from Vienna to Boston, its victories celebrated and its defeats mourned, its dead turned into martyrs, its leaders into the heirs of Demosthenes and Leonidas on a wave of popular enthusiasm which sent money and men to fight for a cause that seemed as much Christendom’s as Greece’s. ‘No other subject has ever excited such a powerful sensation,’ one enthusiast could write long after the first flush of excitement had faded,

The very peasants throughout Switzerland and Germany inquire with anxiety, when their affairs call them to market, what are the last news … In France subscriptions have been opened, and money solicited throughout every town, on behalf of a Christian Nation doomed to perish by the sword or by famine. The Duchesses of Albey, Broglio, and De Caze; every Frenchwoman distinguished by rank, riches, talent, or virtue, have divided the different quarters of Paris among them, and traverse on foot every street, and enter into every house, demanding the charity of their inhabitants for a nation of martyrs.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Almost every foreign volunteer swept along by this enthusiasm had passed through the town of Nauplia, many of them to stay for ever, victims of the squalor, disease and factional greed which lay behind the ceremonial glamour of Otho’s welcome. Italians, Swiss, Swedes, Scots, Irish and Poles had all come here, national rivalries if not forgotten at least subsumed into a common cause, Germans and French who had fought on opposite sides in the Napoleonic Wars, Americans and English enemies at New Orleans united under the name of ‘Philhellene’ – friend of Modern Greece, a Greece which Nauplia promised was the true heir to the land of Homer and Thucydides.

The ceremonial entry of Otho was the last great charade in Nauplia’s history, the last time that the town would work its illusions on a Europe determined to believe. That place is gone, the walls of its lower town pulled down, the surrounding marshes which once earned its pestilential reputation as the Batavia of Greece drained. Within a year of coming ashore from a British frigate, Otho had moved his capital to Athens and the port that the Venetians had called Napoli di Romania had begun its slow decline into the quaint irrelevance of modern Nauplia.

If you wander now among its steep, narrow streets, or along the waterfront with its view across to the jewel-like island fortress where nineteenth-century Nauplia, with its instinctive dislike for reality, housed its public executioner, there can seem nowhere in Greece that retains so much of its architecture and so little of its history. There is an elegance about even its fortifications that belies their past, that touch of unreality which is Venice’s supreme gift to her former possessions. Towards evening, especially, as the sun sinks behind the central mass of the Peloponnese, and the lines of Lassalle’s Palamidi citadel almost dissolve into the rock face, it is difficult to believe anything ever disturbed the town’s peace. Down in the harbour, near an obelisk commemorating French soldiers, a Hotel Grand Bretagne throws off a confused echo of the excitement of 1824 when a ship carrying English gold made Nauplia a sink for every patriot, idealist, charlatan and scrounger in Greece. In the centre of the old town, where the starving Turkish population once held out for a whole year, their mosque has been turned with an insolence too complete to be accident into a cinema. A little higher up the slope, a bullet mark still pocks the wall where Greece’s first president was assassinated. And in that bullet hole, carefully preserved behind glass, we have the quintessential Nauplia-history in aspic, sanitised and mythologized, history reduced to civic statuary and street names, the narrow alleys once notorious for their filth sunk now beneath nothing more oppressive than bougainvillaea, the extravagance, rivalries and violence of its brief years of fame no more intrusive than the wrecks of warships that lie submerged beneath the waters of the gulf.

On a July day in 1841 a group of foreigners gathered in the town’s Roman Catholic Church to add their own lie to the great historical deception that modern Nauplia enshrines. The Church of the Metamorphosis is a small domed building, perched alongside the Hotel Byron on a terrace beneath the walls of the upper town, looking out westwards across the bay towards the ruins of Argos and the Frankish citadel of Larissa. At its south east corner the foundations of an old minaret are visible, and inside the sense of space and air still feels closer to the mosque it once was than any Greek church. Above its altar, a copy of a Raphael Holy Family, the gift of Louis Philippe to King Otho, intrudes a fleshily different but no less alien note. Opposite it, framing the door in a sad parody of a triumphal arch, stands the monument that had brought the congregation to the church that day. It was the work of a Frenchman called Thouret, a ‘Lt. Colonel’ and a ‘Chevalier de Plusieurs Ordres’ he has signed himself with a gallic swagger. ‘A La Memoire Des Philhellènes’, it reads across the top, ‘Morts pour L’independance, La Grèce, Le Roi, et Leurs Compagnons D’Armes Reconnaissants.’ Down the length of its four pillars, inscribed in white on black wood, riddled with mis-spellings, are the names of almost three hundred foreign dead who in the decade before Otho’s arrival had come out to fight for Greek independence.

There can be few more forlorn memorials. Sometimes along the Dutch border one comes across a German cemetery from the last war buried deep in a wood, but even those graves with their air of furtive and collective guilt scarcely catch the sad futility that clings to Thouret’s monument. There is something about its shabby theatricality that nothing else quite matches, a sense of defeated grandeur and deluded optimism which inadvertently captures the fate of the men it commemorates. ‘Hellenes,’ it says, ‘we were and are with you.’ It is not true and it never was. Who, inside or outside Greece, has heard of a single Philhellene other than Byron? How many memorials are there raised by the Greeks themselves in their memory? How, if Greece had deliberately set out to disown their memory, could it have done better than here in Nauplia? – in a town synonymous with Philhellene disillusion, in a converted Turkish mosque given by a German King to the Roman Catholic Church? Could there be any more eloquent or insouciant tribute to the insignificance of these lives than to obliterate their identity in the crude errors and chaotic lettering of their only monument?

Beneath its hollow rhetoric, however, is that common denominator which links its names with those on the monuments of villages, schools, hospitals or railway stations from the Falklands to Burma, from South Africa to Sevastopol. There is always a sharp poignancy in the way these memorials bring the familiar and strange into such permanent proximity, that lives begun on Welsh farms can end in the mission compound at Rorke’s Drift, and nowhere is that more vividly felt than here. Who in 1821 had heard of Missolonghi, Peta, or any of the other battle honours that punctuate the lists of Philhellene dead? What was it that brought William Washington here from America, to die on a British flagship in the harbour at Nauplia, killed by a Greek bullet? Or the nineteen-year-old Heise from Hanover to Peta – only to be beheaded on the field if he was lucky, and if not, forced to carry his comrades’ heads back to Arta before being impaled on the grey castellated walls of its Frankish citadel?

‘We are all Greeks,’

(#litres_trial_promo) Shelley proclaimed in 1821 with the largesse of a man firmly lodged in Italy, and yet if Washington and Heise might well have made the same claim it is less clear what they would have meant. There are certainly men here who would have echoed the language of Shelley’s ‘Hellas’, homeless refugees from monarchical despotism who would have died to keep the seventeen-year-old scion of the house of Wittelsbach or any other royal line out of Greece. There were men again for whom the war was a crusade, fought with all the polemical and emotional bitterness of religious war. ‘I wholly wish,’ one volunteer wrote, ‘to annihilate, extirpate and destroy those swarms and hordes of people called Turk.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Others fought because they had always fought and knew nothing else. There were young Byronists absorbed in some designer war of their own invention, charlatans attracted by the hope of profit, classicists infatuated with Greece’s past, Benthamite reformers, ageing Bonapartists – and then all those there for a dozen different motives, who might just once have known why they came but had long forgotten by the time they died.

‘For the most part the scum of their country,’ the English volunteer Frank Abney Hastings harshly wrote of them, ‘perhaps no crime can be named that might not have been found among the corps called Philhellenes.’

(#litres_trial_promo) This was a verdict, too, which Greek indifference would seem to have endorsed but one need only point to Hastings himself to qualify that judgement.

Or to Number 18 among the Missolonghi dead on the monument, General Normann – the same Normann who had found himself on different sides during the Napoleonic wars, fighting first against, then for, and finally against the French as his native Württemberg changed allegiance. He was in Greece as much to restore his tattered credit in his own eyes as in those of the world. Wounded at Peta, the man who had fought with the Austrians at Austerlitz and with the Grand Army on the retreat from Moscow, died grief-stricken at Missolonghi, finally broken by the last and bitterest disaster of his life.

There are twenty-five dead listed on this monument under Missolonghi; thirty-five under Nauplia; a single name, a man called Coffy, under Mitika; three under Parnassus and so on. In the first and last stages of the war some of these fought and died alongside their comrades, but for most of them these were lonely deaths in a struggle that had no shape and almost no battles, a conflict that wasted lives with a casual and purposeless savagery. There are no decorations after men’s names on this monument, no MM’s, no Croix de Guerre to suggest their courage or folly was ever recognized; no battalion names – no East Kents, no Artists’ Rifles, no Manchester Regiments – to promise any sense of comradeship. Some of them died of their wounds, some died mad, killed themselves or wasted from diseases. Some were killed by the Turks, others by the Greeks they had come to defend. Lord Charles Murray, a son of the Duke of Atholl, rich, generous and unbalanced, died in Gastoumi with a single dollar in his pocket. The eighteen year old Paul-Marie Bonaparte ran away from the university of Bologna only to shoot himself while cleaning his gun before he had so much as seen action. His corpse was kept for five years in a keg of rum in a Spetses monastery before being laid to rest on the island of Sphacteria.

One of the more surprising ironies of history that this monument brings out is that if there was a single country that was relatively untouched by the excitement which swept Europe in 1821 it was Greece’s friend of popular mythology, Britain. It is true that in Thomas Gordon and Frank Abney Hastings Britain sent two of the wealthiest and most influential of the early Philhellenes, and yet in spite of all the committees formed and the pamphlets written, for a whole gamut of reasons that range from party politics to an oddly modern-looking compassion fatigue, no more than a dozen Britons actually made the journey out to Greece to fight during the first two years of the war.†

In the July of 1823, however, an ill-assorted menagerie of animals and men sailed from Genoa in an ugly, round-bottomed ‘tub’ on a voyage that would change this for good and hijack for Britain a place in Philhellene history it has never lost.

On board was the greatest of all Philhellenes, Lord Byron, and at his side a figure who embodies more vividly than anyone else the impact for good and ill that Byron had on the generation of Romantics who went to fight for Greek independence. With the exception of Byron he is probably the only English volunteer of whom anyone has heard, and yet for all that he said and wrote of himself in a lifetime of ruthless self-promotion there is scarcely a fact from his birth onwards that biography has not had to prise free of the lies with which he covered his tracks. He called himself one thing when the parish register gives another, claimed the friendship of Keats when he never met him; railed at his poverty with a private income, and boasted of an exotic past as a pirate when he was no more than a failed midshipman with the diluted romance of his family name, a squalid divorce and a musket ball in a knee to show for his first thirty years.

‘But tell me, who is this odd fish?’ Keats’s friend Joseph Severn demanded when he first met him in 1822 and it is a question biographers have been trying to answer ever since.

(#litres_trial_promo) To modern scholarship he is one of the great obstacles to historical truth, a compulsive braggart and liar. To the late Victorians he was the last apostolic link with its Romantic past, the intimate of Byron and Shelley through whom the ‘mighty dead’ spoke to a smaller and meaner age.

(#litres_trial_promo) To his contemporaries though – more vivid, more imaginatively ‘true’ than either the Grand Old Man of Millais’ portrait or the fraud of modern research – he was the man Severn himself dubbed ‘Lord Byron’s Jackal’;

(#litres_trial_promo) the man known to his friends with an impartiality which perhaps suggests why his name is not among the Philhellene dead, as ‘Greek’ or ‘Turk’ Trelawny.

1 THE WOLF CUB (#ulink_1ffb56bd-d4cb-58a0-8ace-045ae45b8a93)

My birth was unpropitious. I came into the world, branded and denounced as a vagrant; for I was a younger son of a family, so proud of their antiquity, that even gout and mortgaged estates were traced, many generations back, on the genealogical tree, as ancient heirlooms of aristocratic origin, and therefore reverenced. In such a house a younger son was like the cub of a felon wolf in good King Edgar’s days, when a price was set upon his head.

Trelawny’s Adventures of a Younger Son

(#litres_trial_promo)

ONE OF the most depressing assumptions of modern biography is the belief that the truth of men’s or women’s lives always lies in the trivia of their existence. There is often a devotion to the minutiae of a subject’s life that no biographer would dream of expending on his own, a kind of displaced egotism which produces the biographical equivalent of ‘Parnassian’ poetry or possession football, an intricate and over burdened account which bears as much relation to the proper business of biography as chronicle does to history.

The most part of most lives is no more interesting than that of a cat and as both subject and practitioner of biography no one better illustrates this fact than Edward John Trelawny. At some stage in an obscure and embittered youth he seems to have taken stock of his early years, found them wanting in every detail and invented for himself a wilder and more glamorous history of rebellion and adventure which he then successfully maintained in conversation and print for another sixty years.

Of all the silences open to a human being on the subject of himself, Trelawny’s is that of a man who knows how little of interest there is to say, and there is an important lesson to be learned from his deception. There are certainly writers like Shelley or Dickens whose creative life is intimately connected with the rhythms and textures of everyday existence, but the ‘Trelawny’ who still matters, the ‘Trelawny’ Byron and Shelley could both call friend, is the ‘Trelawny’ of myth and not dull reality, the romantic hero who sprang frilly formed from out of his own fantasies and not the failed midshipman modern scholarship has put in its place.

Edward John Trelawny was born on 13 November 1792, that rich and varied year in the history of English Romanticism, the year which saw the birth not just of two of its greatest leaders in Shelley and John Keble but of its hidden and unsuspected nemesis in the infant shape of the future ‘Princess of the Parallelograms’ and wife to Lord Byron, Anne Isabella Milbanke. Through both his parents Trelawny was descended from some of the most colourful figures in English and West Country history, and at the end of the eighteenth century the senior branches of his mother’s and father’s families were still wealthy and important landowners in their native Cornwall. In later years Trelawny usually claimed to have been born in Cornwall himself, but whatever he inherited in terms of character from West Country forebears who fought at Agincourt and against the Armada, the less romantic setting for his own birth was almost certainly his grandfather’s house in Soho Square from where, on 29 November, he was baptized John in the parish church of St Mary Le Bone.

The little we know of his early life comes from a work of fiction that the forty-year old Trelawny foisted on a credulous world as ‘autobiography’ under the title of Adventures of a Younger Son. There is no more than a tiny fraction of it that careful examination has left intact as reliable history, but if among all the fantasies with which he embroidered his life there is one subject on which he can be trusted it is that of his parents, as unlovely a couple from all existing evidence as even their son portrayed. His father was a Charles Trelawny, a younger son himself and an impoverished lieutenant-colonel in the Coldstream Guards; his mother was Mary Hawkins, a sister of Sir Christopher Hawkins Bt., of Trewithen, ‘a dark masculine woman of three and twenty’ with nothing to recommend her but an inheritance.

(#litres_trial_promo) They met at a ball. He was the handsomest man in the room, she apparently the richest catch. In the eyes of the impoverished twenty-nine-year-old officer, wrote their son with that dry economy which characterizes his best prose, ‘Rich and beautiful soon became synonymous’.

He received marked encouragement from the heiress. He saw those he had envied, envying him. Gold was his God, for he had daily experienced those mortifications to which the want of it subjected him; he determined to offer up his heart to the temple of Fortune alone, and waited but an opportunity of displaying his apostacy to love. The struggle with his better feelings was of short duration. He called his conduct prudence and filial obedience – and those are virtues – thus concealing its naked atrocity by a seemly covering.… But why dwell on an occurrence so common in the world, the casting away of virtue and beauty for riches, though the devil gives them? He married; found the lady’s fortune a great deal less, and the lady a great deal worse than he had anticipated: went to town irritated and disappointed, with the consciousness of having merited his fate; sunk part of his fortune in idle parade to satisfy his wife; and his affairs being embarrassed by the lady’s extravagance, he was, at length, compelled to sell out of the army, and retire to economise in the country.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the history and literature of a century famous for its battles of the generations, it is doubtful whether even Shelley or Samuel Butler pursued their fathers’ memory with the same dogged and public hatred that Trelawny showed for his. There is a notorious tale he tells in Adventures of what he calls his first childhood ‘duel’,

(#litres_trial_promo) a mythic battle to the death with his father’s pet raven which in its capacity for violence and surrogate vengeance is the archetype of all the real and imagined struggles of his life ahead, of those fights with maddened stallions or the savage encounters with figures in authority who seemed to his adult mind the reincarnations of early tyranny.

One day I had a little girl for my companion, whom I had enticed from the nursery to go with me to get some fruit clandestinely. We slunk out, and entered the garden unobserved. Just as we were congratulating ourselves under a cherry-tree, up comes the accursed monster of a raven. It was no longer to be endured. He seized hold of the little girl’s frock; she was too frightened to scream; I did not hesitate an instant. I told her not to be afraid, and threw myself upon him. He let her go, and attacked me with bill and talon. I got hold of him by the neck, and heavily lifting him up, struck his body against the tree and the ground …

His look was now most terrifying: one eye was hanging out of his head, the blood coming from his mouth, his wings flapping the earth in disorder, and with a ragged tail, which I had half plucked by pulling at him during his first execution. He made a horrid struggle for existence, and I was bleeding all over. Now, with the aid of my brother, and as the raven was exhausted by exertion and wounds, we succeeded in gibbeting him again; and then with sticks we cudgelled him to death, beating his head to pieces. Afterwards we tied a stone to him, and sunk him in the duck-pond.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trelawny was five at the time of this incident, but there is no record of where it might have taken place. Judging from Adventures and the baptismal records of the successive children born to his increasingly gloomy parents, the Trelawny family lived a peripatetic life during his early years, moving between rented houses in the country, his maternal uncle John Hawkins’s seat at Bignor in Sussex and the family house of his grandfather, General Trelawny, at 9 Soho Square. When Trelawny was six his father had taken on the name of Brereton and with it a large fortune. Yet even with this new wealth there seems to have been no thought of an education for Trelawny and he grew up by his own account an intractable and surly boy, unloved and unloving, as large, bony and awkward as his mother and as violent in his moods as his father.

It was one of his father’s outbursts of temper that led, when he was about nine or ten, to his being literally frog-marched with his older brother Henry, to a private establishment in Bristol for his first experience of school. It was a bleakly forbidding building, enclosed within high walls and, to a child’s eyes, more like a prison. ‘He is savage, incorrigible! Sir, he will come to the gallows, if you do not scourge the devil out of him,’

(#litres_trial_promo) was his father’s parting injunction to the headmaster. The Reverend Samuel Seyer, incongruously small, dapper and powdered for a man who was a savage disciplinarian even by the standards of the day, eagerly embraced the advice. As a pupil of his, Trelawny later recalled with a nice discrimination, he was caned most hours and flogged most days. It was when he finally turned on his attackers, half-strangling the under master and assaulting Seyer himself, that he was sent home, as ignorant as the day he arrived two years earlier. ‘Come, Sir, what have you learnt,’ his father demanded of him.

‘Learnt!’ I ejaculated, speaking in a hesitant voice, for my mind misgave me as to what was to follow.

‘Is that the way to address me? Speak out, you dunce! and say, Sir! Do you take me for a foot-boy?’ raising his voice to a roar, which utterly drove out of my head what little the school-master had, with incredible toil and punishment, driven into it. ‘What have you learnt, you ragamuffin? What do you know?’

‘Not much, Sir!’

‘What do you know in Latin?’

‘Latin, Sir? I don’t know Latin, Sir!’

‘Not Latin, you idiot! Why, I thought they taught nothing but Latin.’

‘Yes, Sir; – cyphering.’

‘Well, how far did you proceed in arithmetic?’

‘No, Sir! – they taught me cyphering and writing.’

My father looked grave. ‘Can you work the rule of three, you dunce?’

‘Rule of three, Sir?’

‘Do you know subtraction? Come, you blockhead, answer me! Can you tell me, if five are taken from fifteen, how many remain?’

‘Five and fifteen, Sir, are – ’counting on my fingers, but missing my thumb, ‘are – are – nineteen, Sir!’

‘What! you incorrigible fool! – Can you repeat your multiplication table?’

‘What table, Sir?’

Then turning to my mother, he said: ‘Your son is a downright idiot, Madam, – perhaps knows not his own name. Write your name, you dolt!’

‘Write, Sir? I can’t write with that pen, Sir; it is not my pen.’

‘Then spell your name, you ignorant savage!’

‘Spell, Sir?’ I was so confounded that I misplaced the vowels. He arose in wrath, overturned the table, and bruised his shins in attempting to kick me, as I dodged him, and rushed out of the room.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As the poet James Michie once remarked, the fact that a man lies most of the time does not mean he lies all of the time, but with Trelawny it is as well to be sceptical. There is no way of knowing whether this exchange, any more than the duel with the raven, actually occurred, and yet what is perhaps more important is that even as a history of Trelawny’s inner life Adventures needs to be treated with a caution that has not always been shown.

There is an obvious sense in which this same wariness has to be extended to all autobiographies, consciously or unconsciously shaping and selecting material as they inevitably do, but with Trelawny the timing of his Adventures makes it of particular relevance. There seems no doubt that the miseries he describes in its pages were real enough, and yet by the time that he came to put them in written form in 1831, the friendships of Byron and Shelley had armed him with a self-dramatizing language of alienation and revolt that enabled him to invest his infant battles with a stature and significance which seem curiously remote from the prosaic reality of childhood unhappiness.

For all that, though, it is clear that the young Trelawny felt and resented these indignities with an unusual intensity. There was an innate physical and mental toughness about him which equipped him for survival in even the most alien of worlds, and yet beneath a hardening carapace of indifference that sense of injustice and emotional betrayal which would fuel his whole life was festering dangerously. On his first night at school, as he lay on a beggarly pallet of a bed, the rush-lights extinguished, he had listened to the snores of his fellow pupils and stifled the sobs that would have betrayed his misery. The child who two years later escaped Seyer’s joyless and savage regime would allow no such weakness in his makeup, no vulnerability. Deprived of affection, he had learned the power of brute strength and domination, the virtue of self-reliance. He had become, he says in his richest Romantic strain, ‘callous’, ‘sullen’, ‘Vindictive’, ‘insensible’ and ‘indifferent to shame and fear’.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘The spirit in me was gathering strength,’ he proudly recalled, ‘in despite of every endeavour to destroy it, like a young pine flourishing in the cleft of a bed of granite.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

For a younger son of Trelawny’s class and educational inadequacy the options in life were strictly limited, but one of the more intriguing schemes for his future after this failure at school was Oxford and a career in the church. With a boy of thirteen who was still plainly gallows-bound, however, the navy offered a more traditional solution, and soon after leaving Seyer’s academy he was taken by his father down to Portsmouth and placed as a gentleman volunteer on the Superb under the command of a Captain Keates.

The treatment a volunteer of Trelawny’s age could expect in the Royal Navy during the time of the Napoleonic Wars would have varied with the personality of the ship’s captain, but even under the most enlightened and humane regime the life in the midshipman’s cockpit of a man-of-war was harsh and brutalizing. In the light of his fixed hatred of the service in later life, however, it is interesting that Trelawny’s first feelings for his new profession were ones of delight, and he soon had an unforgettable glimpse of the excitement and prize-money which made the wartime navy such a dangerous but attractive option to indigent younger sons. After a few days at sea, his ship crossed with the Pickle on its way back from Trafalgar, bringing to the stunned crew of the Superb the news of Nelson’s victory and death. The next morning they fell in with a part of the triumphant fleet, and Trelawny was transferred first to the Temeraire and then across to the stricken Colossus for its journey back to Portsmouth.

We had had a rough passage, being five or six sail of the line in company, some totally, and others partially dismasted. Our ship, having been not only dismasted, but razed by the enemy’s shots (that is, the upper deck almost cut away), our passage home was boisterous. The gallant ship, whose lofty canvases, a few days before, had fluttered almost amidst the clouds, as she bore down on the combined fleets … was crippled, jury-mast, and shattered, a wreck labouring in the trough of the sea, and driven about at the mercy of the wild waves and wind. With infinite toil and peril, amidst the shouts and reverberated hurrahs from successive ships, we passed on, towed into safe moorings at Spithead.

What a scene of joy then took place. From the ship to the shore one might have walked on a bridge of boats, struggling to get alongside. Some, breathless with anxiety, eagerly demanded the fate of brothers, sons, or fathers, which was followed by joyous clasping and wringing of hands, and some returned to the shore, pale, haggard, and heart-stricken. Then came the extortionary Jew, chuckling with ecstacy at the usury he was about to realise from anticipated prize-money, proffering his gold with a niggard’s hand, and demanding monstrous security and interest for his monies. Huge bomboats, filled with fresh provisions, and a circle of boats hung around us, crammed with sailors’ wives, children, doxies, thick as locusts. These last poured in so fast, that of the eight thousand said to belong at that period to Portsmouth and Gosport, I hardly think they could have left eight on shore. In a short period they seemed to have achieved what the combined enemies’ fleets had vauntingly threatened – to have taken entire possession of the Trafalgar squadron. I remember, the following day, while the ship was dismantling, these scarlet sinners hove out the first thirty-two pound guns; I think there were not less than three or four hundred of them heaving at the capstan.

(#litres_trial_promo)

This passage is memorable enough for that exuberance and energy that made him one of the finest storytellers of the century, yet its real interest lies in the light it throws on an event which must in some way have shaped Trelawny’s whole personality and sense of self. Here was an occasion where Trelawny was in a sense there but not really a part, a figure hovering somewhere between participant and spectator at one of the great events of history, an innocently fraudulent beneficiary of the acclaim and excitement which greeted the shattered but victorious Colossus on its return to England.

For the rest of his days Trelawny would bitterly regret that he had missed the greatest battle ever fought under sail and the hurrahs of the ships’ crews anchored at Spithead lodged deep in his soul. Throughout the whole of his life the instinctive movement of Trelawny’s memory would always take him to the centre of great events, cavalierly annexing whole scenes and achievements as if they had been his own, and it was possibly here at Portsmouth, as a romantic and impressionable thirteen-year-old blending invisibly with the men who had won Trafalgar, that he had his first heady taste of that surrogate fame that would be the life blood of his adult existence.

If that is the case, his next years in the navy, from 1806 to 1812, must have been ones of bitter disappointment. By the time that Trelawny emerged from obscurity onto a public stage he had sunk their memory beneath the piratical fantasies that fill Adventures, but in the muster books and logs of Admiralty records his life as a volunteer and then midshipman stretches out from ship to ship in a sobering and unbroken line which leaves no room for romance, ambiguity or fulfilment.

There is no historical document at once so dry and compelling as a ship’s log, nothing that better evokes the routine, discipline and anonymity Trelawny came to hate, but there was another reason, too, for his growing resentment that no mere record could show. ‘Who can paint in words what I felt?’ he asked of his readers later,

Imagine me torn from my native country, destined to cross the wide ocean, to a wild region, cut off from every tie, or possibility of communication, transported like a felon as it were, for life, for, at that period, few ships returned under seven or more years. I was torn away, not seeing my mother, or brother, or sisters, or one familiar face; no voice to speak a word of comfort, or to inspire me with the smallest hope that any thing human took an interest in me … From that period, my affections, imperceptibly, were alienated from my family and kindred, and sought the love of strangers in the wide world …

I could no longer conceal from myself the painful conviction that I was an utter outcast; that my parent had thrust me from his threshold, in the hope that I should not again cross it. My mother’s intercessions (if indeed she made any) were unavailing: I was left to shift for myself. The only indication of my father’s considering he had still a duty to perform towards me, was in an annual allowance, to which either his conscience or his pride impelled him. Perhaps, having done this, he said, with other good and prudent men, – ‘I have provided for my son. If he distinguishes himself, and returns, as a man, high in rank and honour, I can say, – he is my son, and I made him what he is! His daring and fearless character may succeed in the navy.’ He left me to my fate, with as little remorse as he would have ordered a litter of blind puppies to be drowned.

(#litres_trial_promo)

All the evidence suggests, in fact, that his father exerted whatever influence he had in his son’s favour. Trelawny’s career, however, was proof against help. The account he gave of this time in his Adventures is clearly heightened for effect, but his tales of brawls and endless hours of punishment at the masthead are endorsed by his long list of ships as one captain after another rid himself of a recalcitrant midshipman.

From the Colossus to the Puissant, from the Puissant to the Woolwich and on to the Resistance, the Royal William, the Cornelia and the Hecate; the list stretches out, each change marking another step in Trelawny’s disillusionment, another loosening of ties, a fresh confirmation as the surly boy grew into embittered manhood that there was nowhere he belonged.

After his sudden and dramatic baptism of 1805, there was also little action to alleviate the boredom of naval life. In the period immediately after Trafalgar he had gone on two long voyages to the east and South America, but it was not until 1810 – five years and ten ships after going to sea on the Superb – that the amphibious assault on the French-held island of Mauritius gave him his first hope of the excitement he craved.

As it turned out, the defendants offered virtually no resistance to the massive force which had been assembled, but the attack on Java in the following year – one of the forgotten classics of British arms – at last brought the nineteen-year-old midshipman into a war that, with only a brief respite, had been going on since the execution of Louis XVI just two months after Trelawny’s birth.

The fleets carrying the combined army of native and European troops had sailed from Madras and Calcutta, with the Commander in Chief, General Auchmuty, and the Governor-General, Lord Minto, aboard the HMS Akbar on which Trelawny served. After a fraught passage south the invasion force was landed on 4 August 1811 at Chilingching, and marching eastwards through a heavily cultivated landscape of ditches, water tanks and dykes which reminded Minto of a Chinese wallpaper, entered Batavia only to find its defendants withdrawn behind the strongly fortified Lines of Cornelis some six miles to the north.

On 26 August, under the brilliant leadership of Colonel Rollo Gillespie, and supported by naval guns dragged overland and fired by sailors, the lines were stormed and the campaign effectively brought to a conclusion. By that time, however, Trelawny’s role in the victory was over. Sometime before the final assault, his gun party had been surprised on the approach to Cornelis, and in the skirmish which followed he received a sabre slash across the face and a musket ball which remained in his leg for over thirty years until it was removed without anaesthetic by an Italian surgeon under the impressed gaze of Robert Browning.

Java was Trelawny’s first experience of warfare on any major scale with the navy, and his last. Taken back to the Akbar, he soon went down with the cholera that swept through the invasion force, killing more than two hundred sailors. He was lucky to survive, but it marked the end of his career. By the August of 1812 he was back in England, and three years later finally discharged from the navy without a commission, a midshipman sans prospects, education or even the halfpay of a lieutenant, one more ‘useless Dick Musgrove’ left high and dry by the coming of peace.

When Trelawny came to write about his career in the navy, he was again to invest his adolescent anger with all the political and revolutionary radicalism that coloured his schoolday memories. At the age of twenty-three, however, there can have seemed nothing glamorous to him in failure. The knowledge we have of him in these years after he returned from the east is admittedly of a fragmentary and rather special kind, yet the few clues that do survive suggest a far more conventional and vulnerable personality than the man who finally emerged from obscurity to stake his claim as one of the century’s most defiant rebels.

The first of these is no more than a footnote, but it is nevertheless interesting that, in these first years of peace, he seems to have gone out of his way to assert his naval credentials. In the confident pomp of his later Adventures he might denounce the service as an instrument of arbitrary despotism, and yet, far from rejecting it at the time, he masqueraded in civilian life under the name of ‘Lieutenant’ Trelawny, a rank to which he had no claim and one the mature Trelawny would have despised.

For a young man of his temperament and background, coming to terms with the blank mediocrity of his prospects, this discreet and venial piece of self-promotion is neither very unusual nor important, but the same years throw up another clue to his personality which is best recorded in his own words.

The fatal noose was cast around my neck, my proud crest humbled to the dust, the bloody bit thrust into my mouth, my shaggy mane trimmed, my hitherto untrammeled back bent with a weight I could neither endure nor shake off, my light and springy action changed into a painful amble – in short, I was married.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is as much a truism of biography as it is of fiction that domestic happiness leaves little trace of its presence, and so it is perhaps not surprising that we know what we do of Trelawny’s marriage only because and when it failed. His bride, Caroline Addison, was the eighteen-year-old daughter of an East India merchant, a girl of a family ‘fully the equal of his own’

(#litres_trial_promo) as he defensively told his uncle John Hawkins, attractive, ‘accomplished’ and, from the slim evidence of her surviving letters, in love with the tall, handsome midshipman that the ungainly lout of a boy had become.

In spite of the conventional claims he made for his wife’s pedigree, the marriage marked another step in Trelawny’s alienation from his parents. ‘My father was never partial to me,’ he later wrote to John Hawkins, touchingly but unsuccessfully eager to preserve some contact with at least part of his family,

& from the moment of my mariage discarded for ever me, and my hopes, nor has he since either pardoned or even allowed my name to be mentioned in his presence.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Addison family were clearly as opposed to the union as Trelawny’s because with the single exception of the bride’s uncle there was nobody from either side at the wedding that followed their brief courtship. They were married on 17 May 1813 in St Mary’s Paddington and, after an initial period living in Denham and London, moved first to lodgings in College Street, Bristol, in January 1816, and then in the July of the same year to board with a Captain White and his family at Vue Cottage near Bath.

It was from this house on 31 December 1816, just three and a half years and two daughters after their marriage, that Caroline Trelawny eloped to Southampton with a Thomas Coleman, a Captain in the 98th of Foot. In the immediate shock of betrayal Trelawny spoke and wrote wildly of a duel, but as with everything else in his early life reality lagged dully behind and in the summer of 1817 he began instead a long and public haul through the civil and ecclesiastical courts that only ended with the royal assent to an Act of Parliament permitting his divorce and remarriage in May 1819.

There is something in the very nature of divorce testimony which exposes a side of life that history scarcely notices, and through the evidence of the landladies and servants during these trials we have a squalid picture of a life that must have been the opposite of everything the young Trelawny craved. Even the geography of his betrayal has a sadly ignoble feel to it. His wife’s affair with Coleman had begun at their lodgings in Bristol, where the Trelawnys had the first floor, consisting of a drawing room and adjoining bedroom. At the end of March 1816, Captain Coleman, a much older man, arrived, renting a parlour and bedroom on the ground floor beneath. At the hearing in the Consistory Court, the Trelawnys’ landlady, Sarah Prout, described her own discovery of what was going on in the house.

Shortly after Captain Coleman came to lodge in her House, Mrs Trelawny formed an Acquaintance with him unknown to her Husband. Captain Coleman occasionally lent the Deponent (Sarah Prout) Books, but she, having but little time for reading, lent them to Mrs Trelawny, who, as the Deponent afterwards discovered, used to send Margaret Bidder the Servant to Captain Coleman’s Apartments to return or change the Books, and sometimes went herself for that purpose; and it was by these means, as the Deponent believed, that the Acquaintance between them first commenced. The Deponent further saith that by reason of what she will hereafter depose, she verily believes that the Acquaintance between Mrs Trelawny and Captain Coleman led to a criminal Intimacy between them, and that they were guilty of many improper Familiarities with each other … One evening … the Deponent went out to take a walk, and returned about eight o’clock in the Evening: Candles were usually brought and the Window Shutters closed in Captain Coleman’s Parlour before this time, and they were so upon the present Ocasion, but as the Deponent was waiting for the Street Door to be opened she observed the Shutters to be not quite closed, and the Blinds within to be not quite drawn down; and on then looking through the opening the Deponent by the light of the Candle saw Mrs Trelawny reclining on the Sofa on the left Arm of Captain Coleman, whilst his right Hand was thrust into her Bosom and he was kissing her. The Deponent, on the street door being opened, went up Stairs, and almost immediately afterwards heard Mrs Trelawny go up Stairs from the passage as if she had just entered the House, and go into her Bed Room as if to take off her Bonnet after a Walk, Mr Trelawny being, as the Deponent at that time observed, reading in his own Room …

(#litres_trial_promo)

For all the conventionality of its phrasing, Sarah Prout’s testimony provides a sadly absorbing insight into a world poised between a Rowlandsonesque coarseness and an encroaching moral censoriousness. It is not clear from the evidence how much Trelawny himself suspected, but shortly after Coleman’s arrival there had been a row over a handkerchief which uncannily echoes the casus belli in Trelawny’s favourite Othello. Another incident followed soon after when Caroline Trelawny was forced to hide in Coleman’s bedroom on the arrival of some of his fellow officers. Then, one evening at the beginning of June, Trelawny tried to persuade his wife and landlady to join him at the theatre, one of his favourite activities. Caroline refused and he went on alone. Once he had left the house, Caroline suggested to Mrs Prout that the two of them should go instead to the Circus, ‘another place of Theatrical Amusement at Bristol’:

The Deponent endeavoured to dissuade her very much from going, and represented the Impropriety of it, in her, Mrs Trelawny’s then state of Pregnancy, but she persisted in going, and the Deponent in Consequence agreed to accompany her. They accordingly left home, but had not proceeded far before Mrs Trelawny complained of being very poorly, and requested the Deponent to get someone else to accompany her, saying that she would return home. The Deponent accordingly parted with Mrs Trelawny but followed her home in about a quarter of an Hour afterwards and let herself in with a private Key of her own. She tried the Parlour Door, but found it locked, and then walked out into the Garden behind the House where she observed the Blind of Captain Coleman’s Bed Room Window not quite drawn down, and she at the same time observed a Towel lying on the Roof of an adjoining Outhouse, having apparently fallen from Mr and Mrs Trelawny’s Bed Room Window. The Deponent’s Suspicions having been excited by the Circumstances before deposed of, and by the sudden return home of Mrs Trelawny, she walked out on to the Roof of the said Outhouse which she could very easily do, as if to pick up the Towel, and looked into Captain Coleman’s Bed Room, through that part of the Window over which the Blind was not drawn down: It was between eight and nine o’Clock in the Evening, and not quite dark. The Door between the Bed Room and Parlour was also open, and there was light in the latter: the Deponent could therefore distinguish every Object in the Bed Room, and she saith that she then saw Captain Coleman and Mrs Trelawny on the Bed together: Captain Coleman had his Coat and Waistcoat off, his Pantaloons were down, and he was lying upon Mrs Trelawny whose Petticoats were up; and they were then in the Act of Sexual Intercourse with each other. The Deponent remained a Minute or two at the Window, greatly surprised, until she saw Mrs Trelawny get off the Bed, and then she returned into the House, and waited on the Stairs, where in about five minutes she saw Mrs Trelawny come out of the Parlour Door very hastily with her Shoes in her Hand.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mrs Prout testified that she had confronted Caroline with the evidence of her adultery, and demanded that the Trelawnys should leave. After an initial denial Trelawny’s wife had confessed everything, but ‘entreated her not to tell her husband of it’,

as her, Mrs Trelawny’s life depended on it: She also promised most fervently, never to be guilty of such a Crime again, and begged that the Deponent would herself make the Excuse to Mr Trelawny for wishing him to quit his lodgings.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The excuse Mrs Prout came up with was that she needed to paint their rooms, and sometime towards the end of July or the beginning of August the couple moved to new lodgings near Bath owned by a Captain White. Within a short time an unrepentant Caroline was recruiting different members of the White family to collect mail addressed to her under fictitious names at addresses in the town, but if the trial evidence is to be believed, no hint of this seems to have reached Trelawny, who alone among his landladies, servants and his mother-in-law was unaware of his wife’s liaison.

Even if Trelawny was ignorant of what was going on, however, relations between him and Caroline had deteriorated beyond repair, and after the birth of their second daughter at Vue Cottage communications between them were bizarrely limited to written requests for interviews. Unable to tolerate this atmosphere any longer, Mrs White finally asked them to leave, fixing 31 December for their departure. ‘About four o’Clock in the Afternoon however of that day,’ Mrs White testified to the Consistory Court,

Mrs Trelawny being wanted in the Drawing Room, the Deponent and others of her family went to seek her all over the House but she was not to be found: Captain White and Mr Trelawny then left the House to go different ways in search of her, and the Deponent was afterwards informed by her said husband that he had met with Mrs Trelawny who had acknowledged to him that she had eloped with the Intention of proceeding to Captain Coleman at Southampton, and pressed him (Captain White) not to prevent her, but that he had conducted her to her Mother in Bath, and left her under her said Mother’s protection, without apprizing Mr Trelawny therof.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trelawny’s humiliation was complete, the injury to his pride as the case dragged through the courts public and prolonged. For over two years after her elopement he was forced to live with the sordid details of her betrayal, with the bleak evidence that crumpled sheets and billets doux, towels drying at parlour windows and provincial intimacies made up the sad reality of his waking hours.

The one consolation to emerge from this crisis was the friendship of the White family with whom he and Caroline had boarded, and in particular with the young daughter Augusta. In the wider picture of his life this relationship is of only marginal importance but, in the way their kindness brought out all those feelings that had been stifled in childhood and the navy, it foreshadows the most important ties of his life. From the start the Whites had taken his side against Caroline and when, in the February after her elopement, Captain White, dragged down by debts and depression, killed himself, their friendship was sealed. ‘After so dreadful a catastrophe most of your friends would write lamentations at your Father’s rash fate,’ he wrote to Augusta,

but as I differ and am not swayed by opinions of other men – I shall commence with rejoicing that your unfortunate Father has at last ended his miseries … tell your mother to command me in every way … If I can be of the most trivial service command me and I will fly down to my loved Sisters … Your mother shall find in me a Son, you a Brother, and your Brothers a Father.

(#litres_trial_promo)

That last note, so revealing of the emotional vacuum marriage had done nothing to fill, is repeated in another letter to Augusta, written from his family house in Soho Square on 1 October 1817. ‘With my trunks,’ he wrote,

arrived your affectionate letters My Dear Kind Sister, they infused new life, into my drooping soul, – ought not such a friend to counterbalance, all the ills I have endured, – Your love, and sympathy, soothed my signed soul – and bid me hope … O my dearest Sister could you but see my heart, you would wonder it should be inclosed, in so rough a form; – my study through life, has been, to hide under the mask of affected roughness, the tenderest, warmest, and most affectionate sencibility.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Only a handful of Trelawny’s letters survive from this period, and yet colourful as they are, they need to be treated warily as evidence of his feelings. The temptations of so sympathetic a correspondent for a humiliated cuckold are too obvious to need spelling out, but what is more interesting is the impression his letters give that he had neither the education nor the vocabulary at this period to express or even understand the more complex aspects of his personality.

Trelawny was a late and slow developer, and nowhere is this plainer than in his correspondence. With the mature Trelawny it is a safe bet that when he writes something he says precisely what he means to say, but in his early years there is an invariable sense of a man struggling for a voice and character, of a writer fumbling towards an identity that he has not yet made his own.

In their very turbulence, however, their romantic theatricality, their heavy posturing, these letters remain the clearest sign of the inward transformation that Trelawny underwent during the unhappy years of navy and married life. There is no doubt that in the best traditions of romantic alienation he went out of his way to exaggerate his loneliness to any woman prepared to listen, but as in childhood the misery was real enough and the overriding consequence of his marriage was to drive Trelawny into an internalized world of the imagination in which he could take refuge from the disappointments of life.

Collaborating in this retreat, shaping and colouring this inner world, were the books on which Trelawny glutted himself during these wilderness years in Bristol and London. If his grammar and spelling are anything to go by, he had left the navy as ignorant and illiterate as the day he entered, but in the first years of peace he set out on a bizarre but heroic course of reading and self-improvement that was to alter his life, immersing himself in the tragedies of Shakespeare and the romances of Scott, in the defiance of Milton’s Satan and the violence of Jacobean revenge, in Hope’s Anastasius and Peacock’s Nightmare Abbey, in the poetry of Rogers, Cowper, Young, Falconer and Moore, but above all – ten of the fifty odd volumes in his library in 1820 – in the exotic, profligate and dazzling world of Byron’s poetry and tales.

The influence of Byron on Trelawny’s development is a classic example of the sad paradox that while great art seldom made anyone a better person bad art can be profoundly dangerous. There were certainly aspects of Byron’s wonderful mature genius from which Trelawny might well have learned but it was the self-indulgent Byron of Childe Harold that lodged in his soul, the gloomily antisocial heroes of the Eastern Tales like Lara or Conrad, mysterious, violent and aristocratic outcasts from a petty world, in whom he found the model, mirror and philosophical justification for his own troubled personality.

It seems almost too pat that also among his books at this time was Volney’s Ruins of Empire, the work from which Frankenstein’s monster, listening at the cottage window, learned all he knew of human society, but it is too potent a symbol of Trelawny’s plight to let pass. In old age Trelawny was to become an extraordinarily open-minded and intelligent judge of books, but the failed midshipman who fed off Byron in this way was above all an outcast, an intellectual and emotional outsider incapable of measuring a world of which he was largely ignorant, desperate only to find in his reading some echo or corroboration of his own feelings.

There is nothing rare in men or women shaping their lives by some ideal but as one looks at the influence of Byronic Romanticism on Trelawny during these years it seems doubtful that anyone ever chose so spurious a model. He seems to have been able to read and re-read the great tragedies of Shakespeare, and learn nothing but quotations. Dryden has left no mark. Jane Austen appears never to have been read. Byron, however, filled his imagination, shaped his aspirations and confirmed him in his worst excesses, determined the way he talked and wrote, the way he dressed and behaved, until within a decade it was impossible for contemporaries to know whether he had spawned the Corsair or the Corsair him.

It was under this influence, in the boarding houses of Bristol, Bath and London, that Trelawny now committed himself to that major deception which was ultimately to transform his existence. It is hard to imagine that the idea of actual imposture can have seized hold of him all at once, and yet as the failures became starker his youthful daydreams must have taken on a more urgent and adult significance, edging the innocent escapism of his naval days ever closer to a wholesale denial of a life which had let him down.

It would be another dozen years before the fantasies of these years took on their definitive shape in Adventures, but it is still in its pages that we can best trace the genesis of a story that for the next century and more would enjoy the status of history. According to the version of his ‘autobiography’, Trelawny’s ship was in harbour in Bombay when he and a friend called Walter decided to desert, and formed a friendship with a man calling himself De Witt, but whose name turns out to be the equally fictional De Ruyter.

Trelawny’s devotion to him was immediate and complete. There was nothing De Ruyter could not do, nothing he did not know, no way either physically or mentally that he was not Trelawny’s superior. He was approaching his thirtieth year, could speak most European languages faultlessly, and all the native dialects from ‘the guttural, brute-like grunting of the Malay, the more humanized Hindostanee’ to the ‘softer and harmonious Persian’ with equal ease.

(#litres_trial_promo) In stature he was majestic, ‘the slim form of the date-tree’ disguising ‘the solid strength of the oak’.

(#litres_trial_promo) His forehead was smooth as sculptured marble, his hair dark and abundant, his features well defined, his eyes – the windows to his restless and brilliant soul – as various as a chameleon in their colour.

Shortly after coming under De Ruyter’s spell, the incident occurred in this imaginary version of events that ended Trelawny’s naval servitude. The two men were playing billiards, when a Scotch lieutenant who had tormented his and Walter’s lives entered. He demanded to know when Trelawny was rejoining his ship, which was sailing the next day. At this Trelawny’s blood seemed to ignite with fire, and then congeal to ice. He dashed his hat in the man’s face, tore off the last insignia of bondage from his own dress, and drew his sword. The lieutenant broke into abject disclaimers of friendship, and begged his pardon. In his rage Trelawny struck him to the ground, kicking and trampling and spitting on him as the creature begged for mercy. ‘His screams and protestations,’ Trelawny wrote,

while they increased my contempt, added fuel to my anger, for I was furious that such a pitiful wretch should have lorded it over me so long. I roared out, ‘For the wrongs you have done me, I am satisfied. Yet nothing but your currish blood can atone for your atrocities to Walter!’

Having broken my own sword at the onset, I drew his from beneath his prostrate carcass, and should inevitably have despatched him on the spot, had not a stronger hand gripped hold of my arm. It was De Ruyter’s; and he said, in a low, quiet voice, ‘Come, no killing. Here!’ (giving me a broken billiard cue) ‘a stick is a fitter weapon to chastise a coward with. Don’t rust good steel.’

It was useless to gainsay him, for he had taken the sword out of my hand. I therefor belaboured the rascal: his yells were dreadful; he was wild with terror, and looked like a maniac. I never ceased till I had broken the butt-end of the cue over him, and till he was motionless.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The young rebel who had suffered under his father’s brutality, under the cruelty of the Reverend Seyer, and in the navy, was at last free. The mysterious De Ruyter who had passed himself off in Bombay as a merchant, now revealed himself as a privateer operating under a French flag, an enemy to all tyranny and corruption, and in the seventeen-year-old midshipman recognized his spiritual heir and child.

It was the beginning of a new life, and under the leadership of this man, Trelawny embarked on the imaginary career of adventure, excitement, bloodshed, romance and crime which forms the great bulk of his ‘autobiography’. There is no summary of Adventures that can possibly do justice to the colour and imaginative profligacy of his fantasies, nothing that can capture either the compelling immediacy of Trelawny’s fictional world or the visions of violence and domination with which he took his revenge on Caroline and a world that stolidly refused to come up to expectations. As a lonely and unhappy young midshipman, he had daydreamed with his friend Walter of a life without parents, patrimonies or ties ‘amidst the children of nature,’

(#litres_trial_promo) but the dreams now were more sinister. Crazed stallions, Malay peasants, naval officers, ugly old women are all brutally mastered, bullied, beaten, burned, killed or crushed like toads beneath his feet. The vegetation and landscape of the east which so prosaically reminded Lord Minto of a Chinese wallpaper, takes on a vivid almost surrealistic life. Wild animals fill his vision with the same haunting, threatening force that they have in Othello. It is wish fulfilment on the grand scale. In De Ruyter the emotional orphan has found a father; in the lovely Zela, shy and beautiful as a faun, devoted to Trelawny until she expires in his arms after a shark attack, the cuckold at last finds the bride he deserves; and in the excitement, colour and violence of his adventures, the unemployed midshipman wins the recognition the Royal Navy had denied him.

After the public humiliations of the King’s Bench and Consistory Courts, Trelawny was ready to face the world, a Byronic hero with a history and personality to match. In the depths of his imagination he had forged an identity which seemed more vividly true to his sense of self than the reality he had left behind, and if the same might be said of every creative liar, what distinguishes him from a Savage or Baron Corvo is that for the next five years life was to give him what he wanted with an almost Faustian prodigality – years in which invention became a self-fulfilling ordinance, and events danced to the tune of the imagination until fantasy and life pursued each other in an unbreakable circle.

If psychologically he was prepared for a new life, financially, too, he was at last able to expand his horizons. Through all the rows with his father he had continued to draw an allowance of three hundred pounds a year, and while that was scarcely enough to support a family in comfort, for a single man ready to live abroad it opened up possibilities of leisured and gentlemanly self-indulgence. On 19 May 1819, the Royal Assent to his divorce was given, freeing him of those domestic ties which had shackled his turbulent spirit. The seven lean years were over. Caroline, at last, was out of his life, taking their younger daughter, Eliza, with her. The elder child, Julia, had been farmed out to friends of the Whites. He seems to have backtracked too from the brief intensity of his friendship with Augusta, allowing it to mellow into a mutual warmth which lasted throughout their lives.

The disappointment and failures of the navy and marriage, the first-floor parlours and bedrooms, were not just forgotten but buried. Mentally he had toughened and changed, developing out of all recognition from the dull lout his uncle had found him ten years earlier. At the age of twenty-eight he had also physically grown into the role he had created for himself, tall, dark, athletic, immensely strong and handsome. All he needed now was a stage on which to play out his new part. His father had offered to buy him a commission in the army, but for a follower of De Ruyter that was hardly an option. He had talked vaguely for a time of South America as well, of joining either General Wilson or a commune. In the end, however, he settled for the Continent. One of his last addresses in England before leaving was 7 Orange St, the site now of the archives of the National Portrait Gallery. It was a prescient choice of address for a man about to launch himself into the forefront of the nation’s consciousness.

2 THE SUN AND THE GLOW-WORM (#ulink_629081b8-3cf9-53b3-9119-6fec8e4dfd31)

‘You won’t like him.’

Byron to Teresa Guiccioli

(#litres_trial_promo)

IT MUST HAVE BEEN sometime in the autumn of 1819 or the beginning of 1820 that Trelawny finally left England for the Continent, travelling first to Paris where his mother was chaperoning his sisters on a predatory hunt for husbands, and from there to Geneva.

With the poverty of letters from this time it is impossible to be dogmatic about Trelawny’s motives but there would have been compelling reasons other than disappointment and money for his decision to live abroad. There appears to have been nothing particular in his choice of Switzerland, but for a man of his burgeoning radicalism the England of Castlereagh and the Peterloo Massacre can have seemed no place to be, a country frozen in the mini ice-age of reaction which gripped post-Napoleonic Europe, a land, in Shelley’s savage assault, of,

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king, –

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn, – mud from a muddy spring, –

Rulers who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But leech-like to their feinting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow, –

(#litres_trial_promo)

At a time when so many European liberals were seeking refuge in England, there seems something stubbornly wrongheaded in the reverse process, but for Trelawny at least the freedom the Continent offered had more to do with the texture of life than any considered set of principles. Like so many men of his nation and class nineteenth-century Europe represented above all else a continuation of the eighteenth century ‘by other means’, an opportunity – heterosexual, homosexual, financial, social or whatever – to pursue a style of life which inflation and the looming threat of ‘Victorian’ morality was endangering at home.

It was an opportunity he embraced with relief and gusto, but amidst the shooting, hunting and fishing that signalled a reabsorption into his own class, a meeting occurred that was to change the direction of his life for good. A family friend of the Trelawnys from the West Country, Sir John Aubyn, kept a generous if irregular open house at his villa just outside Geneva, and it was in this motley expatriate world that Trelawny first met Edward Williams, an Indian army officer living in Switzerland as a married man with the wife of a fellow officer, and Thomas Medwin, the cousin of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The friendship of Williams, at least, was one that Trelawny treasured all his life, but more important, it was through these two men that he now found himself drawn into the Italian orbit of Byron and Shelley. There is no way of being sure when he first came across the name or work of a poet who, in 1820, was known mainly for his atheism, but Trelawny’s account invests the occasion with a significance that is poetically if not literally true. The scene is set in Lausanne in 1820, during a conversation with a bookseller-friend, who would translate passages of Schiller, Kant or Goethe for an ex-midshipman still painfully conscious of his lack of education. The story forms the opening scene of his Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author and among the apocrypha of his early life it holds a special place.

One morning I saw my friend sitting under the acacias on the terrace in front of the house in which Gibbon had lived, and where he wrote the Decline and Fall. He said, ‘I am trying to sharpen my wits in this pungent air which gave such a keen edge to the great historian, so that I may fathom this book. Your modern poets, Byron, Scott, and Moore, I can read and understand as I walk along, but I have got hold of a book by one that makes me stop to take breath and think.’ It was Shelley’s ‘Queen Mab’. As I had never heard that name or title, I asked how he got the volume. ‘With a lot of new books in English, which I took in exchange for old French ones. Not knowing the names of the authors, I might not have looked into them, had not a pampered, prying priest smelt this one in my lumber-room, and after a brief glance at the notes, exploded in wrath, shouting out, ‘Infidel, jacobin, leveller: nothing can stop this spread of blasphemy but the stake and the faggot; the world is retrograding into accursed heathenism and universal anarchy!’ When the priest had departed, I took up the small book he had thrown down, saying, ‘Surely there must be something here worth tasting.’ You know the proverb, ‘No person throws a stone at a tree that does not bear fruit.’

‘Priests do not’, I answered; ‘so I, too, must have a bite of the forbidden fruit.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Set alongside the impact of Byron on Trelawny, the influence of Shelley’s poetry seems virtually negligible, but this, in stylized form, is still one of the key moments of his life. A few days after this exchange he was breakfasting at a hotel in Lausanne, when a chance conversation with an Englishman on a walking holiday with two women gave him his first opportunity to test this new enthusiasm. It was only after their party had broken up that Trelawny learned that the ‘self-confident and dogmatic’ stranger was Wordsworth, but chasing him down again he ‘asked him abruptly what he thought of Shelley as a poet.

‘Nothing,’ he replied, as abruptly.

‘Seeing my surprise, he added, ‘A poet who has not produced a good poem before he is twenty five, we may conclude cannot, and never will do so.’

‘The Cenci!’ I said eagerly.

‘Won’t do,’ he replied, shaking his head, as he got into the carriage: a rough-coated Scotch terrier followed him.

‘This hairy fellow is our flea-trap,’ he shouted out as they started off …

I did not then know that the full-fledged author never reads the writings of his contemporaries, except to cut them up in a review – that being a work of love. In after years, Shelley being dead, Wordsworth confessed this fact; he was then induced to read some of Shelley’s poems, and admitted that Shelley was the greatest master of harmonious verse in our modern literature.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It says a lot for Trelawny’s critical judgement that, almost alone and untaught, he could have discovered Shelley for himself, but there must also have been more personal and less literary factors that helped quicken his new interest. For a man who saw himself in the self-dramatizing terms he so habitually used, the exiled poet would have offered a mirror to his own miserable experience, and if Shelley was merely the ‘glow-worm’ to Byron’s ‘sun’, then that can only have made him appear more accessible. The arrival of Medwin meant too that the chance of meeting him was something that had probably been discussed from the earliest days in Switzerland, but the unlamented death of Trelawny’s father in 1820 put any thoughts of Italy back by at least a year. Travelling in his own carriage through Chalon-sur-Saône, where he left Edward and Jane Williams to winter in genteel poverty, he continued on to England with his financial hopes high only to discover that he was no better off than he had been before. The old uncertainty of the allowance, the galling necessity of tempering hatred with self-interest, was gone, but there was to be no more money. He had been left £10,000 in 3% gilt-edged stocks which gave him an income of £300 a year.

The evidence for Trelawny’s movements during these months is as sketchy as for any time of his life, but it is likely that arriving in England at the end of 1820 he found himself in no hurry to leave, staying at his mother’s new London home in Berners Street before returning to the Continent in the May or June of 1821.

It is at this moment as one begins to attempt to chart his steps, however, that it becomes obvious just how futile an exercise it is, and just how far at this point a traditional sense of ‘biographical’ time must give way to what could be called ‘Trelawny’ time. Because to any observer totting up the weeks and months spent shooting and hunting during these years a picture emerges of a life hopelessly and terminally adrift, and yet for Trelawny himself this same time seems to have been crushed into a series of defining highlights that obliterate all else, secular epiphanies which, in the great drama he made of his life, assert a pattern of significance – of destiny – that biography can do nothing but follow.

Throughout his life there would be an almost Marvellian fierceness in the way Trelawny would seize his opportunities and in 1820 this destiny seemed to him to lead nowhere but Italy. Through the summer of 1821 he hunted and fished with an old naval friend Daniel Roberts in the Swiss mountains, but beneath the seemingly aimless wanderings the real business of his life was already taking shape. In April 1821, Edward Williams had written to him from Pisa, where he and Jane were living after a bleak winter of ‘soupe maigre, bouilli, sour wine, and solitary confinement’ at Chalon-sur-Saône.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was, he told Trelawny, already an intimate of Shelley. They were planning a summer’s boating together, ‘adventuring’ among the rivers and canals of that part of Italy. ‘Shelley’, he wrote, tantalizingly