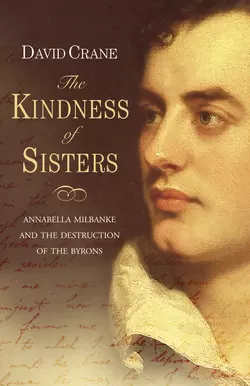

The Kindness of Sisters: Annabella Milbanke and the Destruction of the Byrons

David Crane

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A groundbreaking work of Romantic biography; David Crane’s book is an astonishingly original examination of Byron, and a radical approach to biography.Crane focuses on the lifelong feud between Augusta – Byron’s half-sister with whom he had a passionate affair – and Annabella, his society wife. Recreating a meeting between the two, years after Byron′s death – the Romantic ‘High Noon’ – he explores the emotional and sexual truth and the human vulnerability that lie at the heart of the Byron story.‘The Kindness of Sisters’ is not only rigorous in its scholarship, but also superbly compelling drama. Crane’s book combines passion, revenge and recrimination in 19th-century Britain with all the intensity of a Greek tragedy.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.