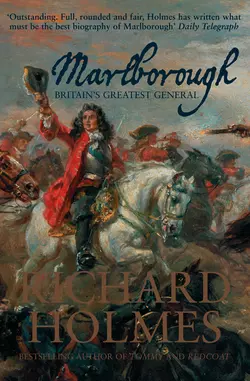

Marlborough: Britain’s Greatest General

Richard Holmes

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 844.33 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Bestselling military historian Richard Holmes delivers an expertly written and exhilarating account of the life of John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough and Britain′s finest soldier, who rose from genteel poverty to lead his country to glory, cementing its position as a major player on the European stage and saviour of the Holy Roman Empire.John Churchill is, by any reasonable analysis, Britain’s greatest-ever soldier. He mastered strategy, tactics and logistics. His big four battles, Blenheim (which saved the Holy Roman Empire), Ramilies, Oudenarde and Malplaquet were events at the very centre of the European stage. He captured Lille, France’s second city, overran Bavaria and beat a succession of French marshals so badly that one, the squat and energetic Bofflers, was rewarded by Louis XIV for only losing moderately.A coalition manager long before the phrase was invented, he commanded a huge polyglot army with centrifugal political tendencies and bending it to his will by sheer force of personality.Yet John Churchill was also deeply controversial. He accepted a pension from one of Charles II’s mistresses for services vigorously rendered. He owed his rise and his peerage to James II yet, determined to be on the winning side, he deserted him in his hour of need in 1688. He maintained regular correspondence with the Jacobites while serving William and Mary and with the French while fighting Louis XIV. He made money on a prodigious scale, but was notoriously tight-fisted, long regretting an annuity given to a secretary whose quick-wittedness saved him from capture. But in the age when commissions were bought and sold, and commanders often owed their position to the hue of their blood, he never lost his soldier’s confidence.