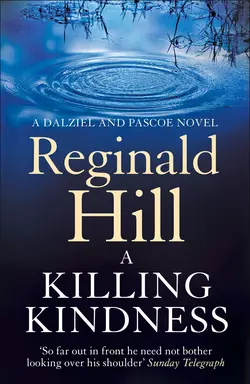

A Killing Kindness

Reginald Hill

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 766.24 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Altogether an enjoyable performance, one of Mr Hill’s best’ Financial TimesWhen Mary Dinwoodie is found choked in a ditch following a night out with her boyfriend, a mysterious caller phones the local paper with a quotation from Hamlet. The career of the Yorkshire Choker is underway.If Superintendent Dalziel is unimpressed by the literary phone calls, he is downright angry when Sergeant Wield calls in a clairvoyant.Linguists, psychiatrists, mediums – it’s all a load of nonsense as far as he is concerned, designed to make a fool of him.And meanwhile the Choker strikes again – and again…